Abstract.

Recent studies on the Chinese herbal medicine PC SPES showed biological activities against prostate cancer in vitro, in vivo and in patients with advanced stages of the disease. In investigating its mode of action, we have isolated a few of the active compounds. Among them, baicalin was the most abundant (about 6%) in the ethanol extract of PC SPES, as determined by HPLC. Baicalin is known to be converted in vivo to baicalein by the cleavage of the glycoside moiety. Therefore, it is useful to compare their activities in vitro. The effects of baicalin and baicalein were studied in androgen‐positive and ‐negative human prostate cancer lines LNCaP and JCA‐1, respectively. Inhibition of cell growth by 50% (ED50) in LNCaP cells was seen at concentrations of 60.8 ± 3.2 and 29.8 ± 2.2 µm baicalin and baicalein, respectively. More potent growth inhibitory effects were observed in androgen‐negative JCA‐1 cells, for which the ED50 values for baicalin and baicalein were 46.8 ± 0.7 and 17.7 ± 3.4, respectively. Thus, it appears that cell growth inhibition by these flavonoids is independent of androgen receptor status. Both agents (1) caused an apparent accumulation of cells in G1 at the ED50 concentration, (2) induced apoptosis at higher concentrations, and (3) decreased expression of the androgen receptor in LNCaP cells.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer among American men. Approximately 180 000 Americans will be diagnosed with this cancer this year. Conventional treatment for prostate cancer includes prostastectomy, radiation and cryotherapy, combined hormonal therapy, androgen block and combined chemotherapy (Landis et al. 1998; Legler et al. 1998). In recent years, it has becoming increasingly common for prostate cancer patients, especially those with metastatic disease, to turn to unconventional (‘alternative’) treatments, of which herbal therapies (phytotherapies) are the most common.

The use of herbs and herbal preparations in the treatment of disease is dramatically rising in recent years both in the US and in Europe. A wide range of herbal preparations are available in natural food and ‘health food’ stores as dietary supplements for cancer patients. Despite the wide use of these herbal preparations, little is known about their effectiveness, mode of action, side‐effects, active components or interactions between components within a single herb or herbal mixture. In addition, little is known about the possible adverse (or advantageous) interactions of herbal preparations with conventional antitumour drugs. There is an indisputable need, therefore, to understand the mechanism of action of these preparations. Such knowledge may aid in averting the undesirable effects of herbs, and if particular herbs are indeed effective, in enhancing their effectiveness.

Increasing numbers of prostate cancer patients have turned to the use of the Chinese herbal preparation denoted PC SPES for treatment of their disease (Lewis & Berger 1997). There is already significant literature on the effects of PC SPES on patients (Chen & Wang 1998; DiPaola et al. 1998; Small 1998; Portfield 1999; Mittelman et al. 1999; Pfeifer et al. 2000; Small et al. 2000; Oh et al. 2000) and in animal cancer models (Kubota et al. 2000; Tiwari et al. 1999), as well as against human cancer cells in vitro (Halicka et al. 1997; 1997, 1998; de la Tallie et al. 1999; Kubota et al. 2000).

PC SPES contains partially purified extracts of eight different herbs: Dendrantherma morifolium, Tzvel; Ganoderma lucidium, Karst; Glycyrrhiza glabra L.; Isatis indigotica, Fort; Panax pseudo‐ginseng, Wall; Robdosia rubescens; Scutellaria baicalensis, Georgi; and Serenoa repens. Each of the eight herbs combined into PC SPES has one or more chemical components that have been described as having antiproliferative, anticancer or antimutagenic activity (see reviews in Halicka et al. 1997 and Darzynkiewicz et al. 2000). Some components are DNA topoisomerase inhibitors, others are protein kinase inhibitors, and still others have antimutagenic and/or antioxidant activity.

One of the major classes of components in herbal mixtures is flavonoids. In fact, the flavonoid baicalin is easily identified as a major component of PC SPES. This compound is also present in the popular Japanese herbal mixture Sho‐saiko‐to, which is widely used for the treatment of liver disease and has been demonstrated to possess antiproliferative activity against a range of tumour cells (Okita et al. 1993). Baicalin is known to be hydrolysed in vivo to baicalein by beta‐glucuronidase (Muto et al. 1998). Thus, although the concentration of baicalein in a formulation such as PC SPES is at least 10‐fold lower than baicalin, its concentration would be expected to increase upon ingestion as a consequence of hydrolysis. Treatment of prostate cancer cells with the herbal mixture PC SPES results in the accumulation of cells in the G1 phase, increased apoptosis and down‐regulation of the androgen receptor (Halicka et al. 1997; 1997, 1998). Using similar end‐points, it was of interest to identify what, if any, activity the compounds baicalin and baicalein had when tested against prostate tumour cells in vitro.

Materials and methods

PC SPES extracts

PC SPES preparations (obtained from BotanicLab, Brea, CA) were in the form of gelatine capsules containing powdered extract of the eight herbs listed in the Introduction. The content of a single capsule was dissolved in 1 ml of 70% ethanol and processed as previously described (Halicka et al. 1997). The extract was then dried over a rotary evaporator. The dried powder was weighed and redissolved in 70% ethanol to prepare a stock solution of 46 mg/ml, which was stored at 4 °C.

Baicalin

Baicalin was isolated from PC SPES by preparing an extract of PC SPES in 70% ethanol and fractionating the extract using a Shimadzu SPD‐M10A HPLC system with C18 reverse phase preparatory columns (Vydack SelectPore 300P, Hesperia, CA). Two solvents, 10% acetonitrile (A) and 100% acetonitrile (B), were used to generate a linear gradient for separation at a rate of 0.5 ml/min. The baicalin isolated from PC SPES was compared with that purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). The purity of baicalin purchased from Sigma was assayed by HPLC and used for comparison. A single fraction isolated from PC SPES corresponding to baicalin had a purity > 90% when compared to the commercial preparation. Stock solutions (20 mm) of baicalin purified from PC SPES were prepared in dimethyl sulphoxide and stored at −20 °C.

Baicalein

A commercial preparation of baicalein with a purity of 98% was obtained from Sigma and prepared as a stock solution in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mm.

1H NMR spectrum

The proton NMR spectrum of baicalin isolated from PC SPES was compared to the commercial baicalin purchased from Sigma. The compounds were dissolved in DMSO‐d6 and were measured on a VarianUNITY Inova 400 system (400 MHz frequency; Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA).

Electronspray mass spectrum

The mass spectrum of baicalin was measured at Mass Consortium (San Diego, CA) using a Hewlett‐Packard 1100 MSD electronspray mass spectrometer. The ion evaporation process generated the positive and negative ions.

Cell culture

The human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). The androgen receptor‐negative JCA‐1 cell line developed by Muraki et al. (1990) was obtained from one of the originators, Dr Jen Wei Chiao of New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY. Both cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, L‐glutamine and antibiotics (Halicka et al. 1997). All media, supplements and antibiotics were obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). The cultures were periodically tested for Mycoplasma infection. To maintain asynchronous exponential growth, these adherent cells were routinely seeded at 3 × 105 in a T‐75 flask and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 5–6 days and then repassaged at a 1:10 dilution by trypsinization (0.25% trypsin/1 mm EDTA). Morphological changes and cell counts of the control and treated cancer cells were determined by light microscopy. Only exponentially and asynchronously growing cells were used in all experiments.

Inhibition of cell‐growth and viability assays

The MTT reagent kit was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Roche Diagnosis Corp, Indianapolis, IN) to count viable cells. Tetrazolium dye (MTT) is cleaved to form formazan by metabolically active cells and exhibits a strong red absorption band at 550–618 nm. The protocol for the cell viability assay was provided by the manufacturer and modified in our laboratory as described below.

Prostate cancer cells were seeded in 96‐well microtitre plates at a concentration of 3 × 103 (JCA‐1) or 6 × 103 (LNCaP) cells per well, in a volume of 100 µl of cell culture medium. After 24 h, 20 µl aliquots of the compounds at various concentrations were added to the attached cells. Each concentration was plated into three wells to obtain mean values. To eliminate any solvent effect, 20 µl of the solvent used in the preparation of the highest concentration of the compounds (a maximum of 0.5% by volume of DMSO) was added to the control cells in each well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in the CO2 incubator for 72 h. At the end of day three, the culture medium was carefully removed without disturbing the cells, and replaced by 100 µl of fresh cell medium. Ten microlitres of MTT reagent was added to each well and the plates were incubated again in the CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 4 h. One hundred microlitres of SDS solublizing reagent (from Boehringer Mannheim) was added to each well. The plate was allowed to stand overnight in the CO2 incubator and read by ELISA Reader (EL800, Bio‐Tek Instruments, Inc., Boston, MA) at a wavelength of 570 nm. The percentage cell viability was calculated according to

100% (absorption of the control cells – absorption of the treated cells)/absorption of the control cells.

By definition, the viability of the control cells, from the untreated cultures, was defined as 100%.

Sample preparation for cell cycle measurement

Cultured cells (2–4 × 106 cells) were exposed to varying concentrations of baicalein or baicalin for 48 h (in 12.5 cm2 area flasks) before being harvested. The cells were washed with PBS and fixed in ice‐cold 70% ethanol. Aliquots of fixed cells were rehydrated into PBS and stained with 1.0 µg/ml DAPI (4,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole from Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) dissolved in 10 mm piperazine‐N, N‐bis‐2‐ethane‐sulphonic acid buffer (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) containing 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2 and 0.1% Triton X‐100 (Sigma) at pH 6.8 as previously described (Halicka et al. 1997).

Analysis of cell cycle distribution and apoptosis

Cellular DNA content, after cell staining with the DNA‐specific fluorochrome, DAPI, was measured with an ELITE ESP flow cytometer (Coulter Inc., Miami, FL) using UV laser illumination. The Multicycle program (Phoenix Flow Systems, San Diego, CA) was used to deconvolute the DNA frequency histograms to estimate the frequency of cells in different phases of the cell cycle and in apoptosis. The experiments were repeated several times, yielding essentially identical results.

Sample preparation for analysis of androgen receptor (AR) expression

Cultured LNCaP cells (2–4 × 106) were exposed to baicalein or baicalin at the desired concentrations for 48 h. The cells were harvested and washed with PBS and attached to microscope slides by cytocentrifugation at 1000 rpm for 6 min, using a Shandon Cytospin 3 centrifuge (Shandon Co., Pittsburgh, PA). The cells were fixed and permeabilized with 80% ethanol at −20 °C for 24 h. After fixation, the cells were washed twice with PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.1% sodium azide (PBS‐BSA) and incubated for 1 h in the dark at room temperature with 100 µl PBS‐BSA containing 1.3 µg anti‐AR monoclonal antibody or 1.3 µg mouse anti‐IgG1, which served as a negative, isotype control. Purified mouse IgG1 kappa and antihuman AR (clone AR 441) antibodies were obtained from DAKO Corp (Carpinteria, CA). This antibody recognizes an epitope between amino acids 229–315 of the human AR and does not cross‐react with the mouse AR. The cells were then washed with PBS‐BSA, and 100 µl FITC‐conjugated goat‐antimouse F(ab′)2 (DAKO) (diluted 1:30 in PBS‐BSA) was added for 1 h in the dark at room temperature. At the end of the incubation, the cells were suspended in the staining buffer containing 5 µg/ml propidium iodide (PI; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and 100 µg/ml RNase A (Sigma) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The slides were then mounted under coverslips in PBS. To avoid unspecific binding of the monoclonal antibody, the staining was preceded by incubation with normal goat serum for at least 15 min.

Measurement of AR by laser scanning cytometry (LSC)

The fluorescence of individual cells located on microscope slides was measured using an LSC (CompuCyte Co., Cambridge, MA). Detailed description of cell fluorescence analysis by LSC is provided elsewhere (Darzynkiewicz et al. 1999; Kamentsky 2000). Fluorescence was excited at a wavelength of 488 nm by the beam of the argon ion laser directed through the epi‐illumination port of the microscope and imaged through the objective lens onto the slide. The slide, with its position monitored by sensors, was placed on the computer‐controlled motorized microscope stage, which moved perpendicular to the scan of the laser beam in 0.5 µm steps. Green (FITC‐AR) and red (PI‐DNA) fluorescence emitted from the cells was measured by separate photomultipliers that detected the light within the 530 ± 20 and 600 ± 20 nm spectrum ranges, respectively. Cytoplasmic AR staining could be detected separately from nuclear AR staining and correlated with cell cycle phase as determined by PI staining. At least 3 × 103 cells were analysed per sample. Other details have been presented previously (Halicka et al. 1997). Each experiment was repeated three times.

Results

Isolation and characterization of the flavonoid baicalin

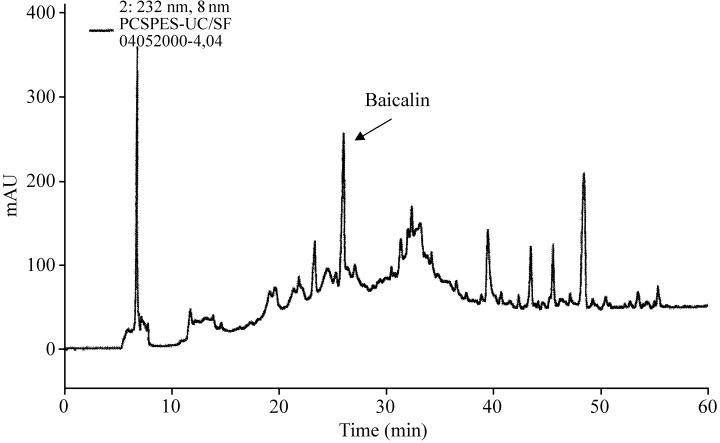

HPLC of the PC SPES extract in 70% ethanol showed a major peak at a retention time of 25.35–26.53 min (see Fig. 1). The percentage area at this retention time is about 6%, as calculated by the computer fitting program provided in the HPLC software. This peak was collected and further purified to approximately 90–95% by repeated HPLC separations. For comparison, a pure sample of baicalin purchased from Sigma was added to the HPLC purified sample. Both samples appeared at the same retention time and were superimposable (data not shown).

Figure 1.

HPLC separation of PC‐SPES in 70% ethanol (concentration 100 mg/ml), flow rate 0.5 ml/min. The detection wavelength was 232 nm.

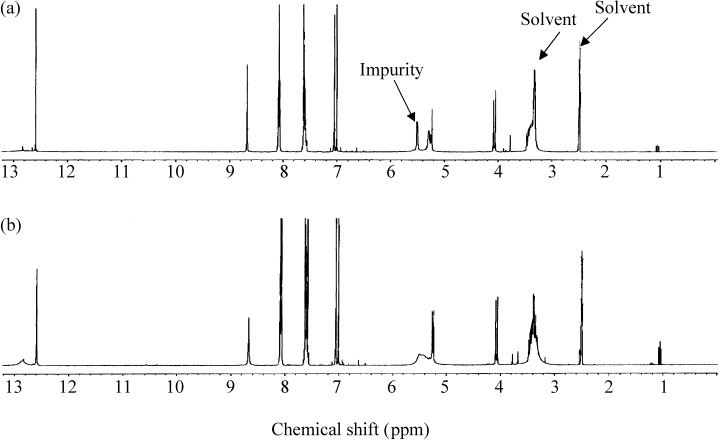

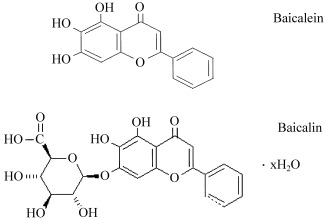

The isolated compound was further characterized by ES‐MS and lH NMR. ES‐MS measurement of the negative ion of this HPLC fraction showed an exclusive peak at e/m of 447 (not shown). The similarity of the 1H NMR spectrum of the isolated fraction (Fig. 2a) and commercial baicalin (Fig. 2b) suggested the structure of the compound to be baicalein 7‐glucuronic acid, 5,6‐dihydroxyflavone (molecular weight 446), that is, a glucose and baicalein, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 2.

1H NMR of baicalin at 400 MHz. (a) HPLC‐purified baicalin from PC SPES; (b) baicalin obtained from Sigma. The solvent was DMSO‐d‐6. The Sigma baicalin is used as a reference.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of baicalein and baicalin.

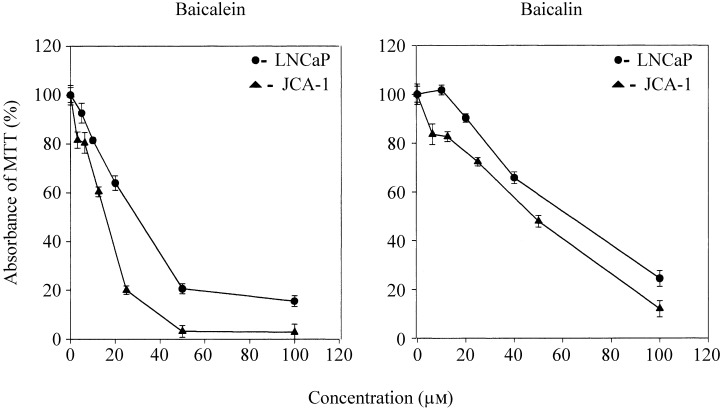

Inhibition of cell growth by baicalin and baicalein

Growth of LNCaP cells, as measured in MTT assays, was suppressed by baicalin and baicalein (Fig. 4); the effects were concentration‐dependent (Table 1). Baicalin inhibited cell growth by 50% (ED50) 3 days after administration to the cultures at a concentration of 60.8 ± 3.2 µm (Table 1). Baicalein, with an ED50 value of 29.8 ± 2.2 µm, was more potent than baicalin.

Figure 4.

Cell viability (MTT) curves for baicalin and baicalein treatment of LNCaP (circles) and JCA‐1 (triangles) cells. Cells were exposed for 3 days to various concentrations of the two flavonoids or to an equivalent volume of solvent alone. Analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

Table 1.

Growth inhibitory effects (ED50 values) of baicalin and baicalein

| Cells | ED50 (µm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Baicalin | Baicalein | |

| LNCaP | 60.8 ± 3.2 | 29.8 ± 2.2 |

| JCA‐1 | 46.8 ± 0.7 | 17.7 ± 3.4 |

The concentrations of baicalin and baicalein that inhibited growth of LNCaP and JCA‐1 cells by 50% were determined from growth curves obtained with the MTT assay as in Fig. 4 (mean and standard deviation of three experiments).

Similar results were obtained with the AR‐negative cell line JCA‐1. Thus, the ED50 values for baicalin and baicalein were 46.8 ± 0.7 and 17.7 ± 3.4 µm in JCA‐1, respectively (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

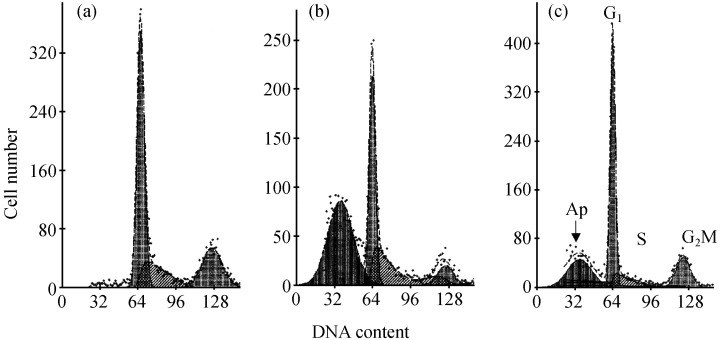

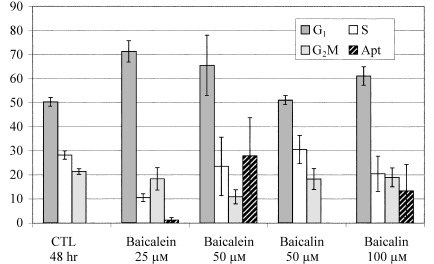

Cell cycle effects and apoptosis induced by baicalin and baicalein

The effects of baicalin and baicalein on the cell cycle of LNCaP cells are illustrated in Fig. 5. The increase in the proportion of G1‐phase cells was observed at concentrations of 25 and 50 µm baicalein, and 50 and 100 µm baicalin (Fig. 6). Pronounced apoptosis resulting in substantial numbers of LNCaP cells having a fractional (sub‐G1) DNA content consistent with apoptosis was observed at a baicalin concentration of 100 µm and a baicalein concentration of 50 µm (see 5, 6), although the initial signs of apoptosis could be observed in LNCaP cultures exposed to as little as 25 µm baicalein (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Cell cycle distribution of LNCaP cells following treatment by baicalin and baicalein. Cells were stained with propidium iodide for DNA content and the DNA frequency distributions analysed using the software program MulticycleTM. Cells were either untreated (a) or exposed for 72 h to 50 µm baicalin (b) or 25 µm baicalein (c).

Figure 6.

Cell cycle effects of baicalein and baicalin on LNCaP cells. The cells were stained with propidium iodide for DNA content. The percentages of cells in each cell cycle compartment were determined by deconvolution of the DNA content–frequency histograms. The percentage of cells with a sub‐G1 DNA content was determined to represent apoptotic cells and is expressed as a percentage of the total cell population.

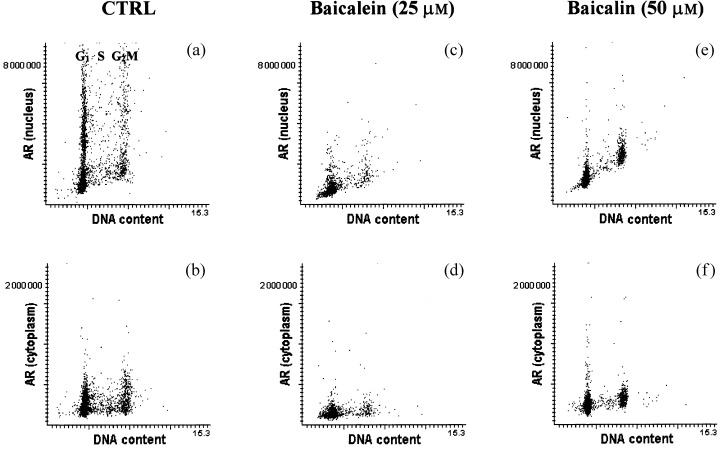

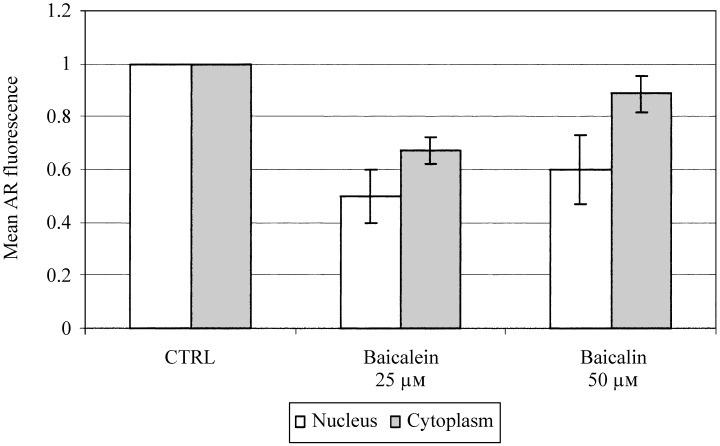

Suppression of AR expression in LNCaP cells

Expression of AR detected immunocytochemically in individual LNCaP cells was measured separately in the cell nucleus (Fig. 7a,c,e) and in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7b,d,f) by LSC. The AR appears to be localized at the nuclear membrane; only a small fraction of AR is located in the cytoplasmic compartment in either untreated cells (Fig. 7b) or flavonoid‐treated cells (Fig. 7d,f). Accordingly, the effects of baicalein and baicalin on nuclear AR were more profound than on cytoplasmic AR. Figure 7 demonstrates the effects of these agents on nuclear and cytoplasmic AR expression following treatment of LNCaP cells with 50 µm baicalin or 25 µm baicalein for 48 h. In Fig. 8, the fluorescence associated with nuclear AR and cytoplasm AR are both normalized to 1 in untreated LNCaP cells following subtraction of background fluorescence (as determined by binding of isotype control antibody) in order to observe and compare the effects of individual agents. Baicalin at concentrations of 50 µm lowered nuclear AR expression by 50% and cytoplasmic AR by 10%, while half that concentration of baicalein (25 µm) reduced nuclear and cytoplasmic AR expression by 60 and 40%, respectively (Fig. 8). There appeared to be no cell cycle phase‐specific change in AR expression as a result of treatment with either flavonoid, regardless of concentration.

Figure 7.

AR expression in LNCaP cells. (a, b, respectively) In the nucleus and cytoplasm of untreated LNCaP cells; (c, d, respectively) following treatment with 25 µm baicalein; (e, f, respectively) following treatment with 50 µm baicalin. Cells on slides were stained for DNA content with propidium iodide and for AR with FITC‐labelled monoclonal antibody. The propidium iodide red fluorescence and FITC green fluorescence were measured for 3 × 103 LNCaP cells. a, c and e contain dot plots of DNA (PI) content versus nuclear staining of AR, while b, d and f contain dot plots of DNA versus cytoplasmic staining of AR with the monoclonal antibody.

Figure 8.

Suppression of androgen receptor‐associated fluorescence in nucleus and cytoplasm measured by LSC following treatment with baicalein (25 µm) or baicalin (50 µm). The fluorescence of AR in untreated cells was normalized to 100% for both the nucleus and cytoplasm compartment following subtraction of background as measured by binding of IgG isotype control.

Discussion

As mentioned in the Introduction, PC SPES contains many concentrated phytochemicals and some of them have known biological activities (see Halicka et al. 1997). None of these components, however, was tested individually for its activity against human prostate cancer cells. In the present study, we focused our attention on baicalin for two reasons. First, baicalin is one of the most dominant components of PC SPES as detected by HPLC, representing 6% of the ethanol‐soluble fraction of this herbal mixture. The second reason is the multipotent biological activity of this flavonoid.

A wealth of information is available on the effects of baicalin on normal and tumour cells and on its possible antitumour activity. As a flavonoid, baicalin is a secondary plant metabolite and is one of the major active compounds in Scutellaria baicalensis. In addition to its presence in PC SPES, it is found in the popular Chinese–Japanese Kempo medicine, Sho‐saiko‐to. Such compounds are known to have anti‐oxidative (Yoshino & Murakami 1998), anti‐inflammatory (Huang 1992; Kang et al. 1996; Lin & Shieh 1996), antibacterial and antiviral activities (Rahman et al. 1992; Yano et al. 1994; Nagai et al. 1995). Baicalin, a significant component of these herbal preparations, is reported to be a stronger anti‐oxidant than the food preservative BHT or vitamin E, presumably as a result of its ability to inhibit oxygen radical formation by enhancing the oxidation of the Fe2+ ion (Yoshino & Murakami 1998). Baicalin’s anti‐inflammatory activity is believed to be derived from its ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase, thromboxane A2 and 5‐lipoxygenase (Wang et al. 1993; Ghosh & Myers 1997). These enzymes catalyse the synthesis of prostaglandins, which play key roles in lipid function and tumour progression. Inhibition of the production of these toxic lipid hormones can lead to subsequent tumour suppression. The antitumour activities of baicalin may also involve up‐regulation of Fas and induction of apoptosis (Liu et al. 1998).

The immunomodulatory properties of baicalin have been reported to include augmentation of certain immune functions, modulation of the adrenergic system under stress (Shao et al. 1999) and enhancement of both NK cell activity and α‐interferon production (Xu et al. 1994). Baicalin has also been used as a protective agent during treatment with the chemotherapeutic agent camptothecin (Yokoi et al. 1995).

The present data demonstrate that the effects of baicalin or its metabolite baicalein on various aspects of prostate cancer cell growth and survival are essentially similar, although the metabolite baicalein proved to be more potent. Thus, in the presence of either baicalin or baicalein, prostate cancer cells ceased growing (Fig. 4) and resulted in an increased percentage of cells in the G1 phase (Fig. 5). Cell accumulation in G1 may have been a consequence of (1) a block in transit through that cell cycle phase, (2) preferential death in the other cell cycle compartments (S and G2M), or (3) both events occurring simultaneously. At higher concentrations of these agents, LNCaP cells underwent apoptosis. Furthermore, the expression of AR was reduced by baicalin treatment of LNCaP cells. In each instance, the resultant changes in growth and cell cycle distribution of androgen receptor expression required several‐fold lower concentrations of baicalein to achieve the results observed with baicalin. It is also important to note that the androgen‐negative cell line JCA‐1 was more sensitive to the action of both flavonoids than were androgen‐expressing LNCaP cells.

In conclusion, the reported biological activities of baicalin and baicalein and their in vitro effects presently observed are consistent with the anticancer activity of PC SPES, the herbal mixture containing these compounds. It is impossible, however, to determine whether the activity of PC SPES in vitro or in vivo can be accounted for by a single component, because (1) the herbal mixture is composed of many herbs, each known to contain at least one but often several active components, (2) ethanolic extracts of complex herbal mixtures may or may not fairly represent the actual contributions of individual components to their biological activity in vivo, (3) through direct or indirect interactions certain components of herbal mixtures might diminish or augment the activity of any another component(s), and (4) any single component invariably fails to express the wide range of activities often observed in the individual herb or, especially, with herbal mixtures. While it is apparent that baicalin and baicalein have sufficient activity against prostate cancer cells to warrant further investigation in vitro and in animal models, additional studies are necessary to determine whether other important components of the clinically useful herbal mixture PC SPES can be identified as contributing to its activity in vivo.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from CaP Cure (S.C.) and grant R01 CA28704 from the National Cancer Institute (Z.D.). A.D. was on leave from the Department of Hematology and Oncology, Warsaw Medical University, Warsaw, Poland. We wish to thank Mr January Kunicki for his technical assistance with and useful discussion about the cell cycle progression experiments.

References

- Chen S & Wang X (1998) Composition of Herbal Compound for Treating Prostate Carcinoma. US patent 5 665 393.

- Darzynkiewicz Z, Bedner E, Li X, Gorczyca W, Melamed MR (1999) Laser‐scanning cytometry: a new instrumantation with many applications. Exp. Cell Res. 249, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzynkiewicz Z, Traganos F, Wu JM, Chen S (2000) Chinese herbal mixture PC SPES in treatment of prostate cancer (review). Int. J. Oncol. 17, 729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Tallie A, Hayek OR, Buttyan R., Bagiella E, Burchardt M, Katz AE (1999) Effects of PC‐SPES in prostate cancer: a preliminary investigation on human cell lines and patients. Br. J. Urol. 84, 845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disaola RS et al. (1998) Clinical and biological activity of an estrogenic herbal combination (PC SPES) in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 339, 785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh J & Myers CE (1997) Arachidonic acid stimulates prostate cancer cell growth: critical role of 5‐lipoxygenase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 235, 418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halicka D et al. (1997) Apoptosis and cell cycle effects induced by extracts of the Chinese herbal preparation PC SPES. Int. J. Oncol. 11, 437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh T‐C, Chen SS, Wang X, Wu JM (1997) Regulation of androgen receptor (AR) and prostate specific antigen (PSA) expression in the androgen‐responsive human prostate LNCaP cells by ethanolic extracts of the Chinese herbal preparation, PC‐SPES. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 42, 535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh T‐C, Ng C, Chang C, Chen SS, Mittelman A, Wu JM (1998) Induction of apoptosis and down‐regulation of bcl‐6 in mutu I cells treated with ethanolic extracts of the Chinese herbal supplement PC‐SPES. Int. J. Oncol. 13, 1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang KC (1992) Pharmacopedia of Chinese Herbal Medicine. Cleveland, OH: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kamentsky LA (2000) Laser scanning cytometry. Meth. Cell Biol. 63, 51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JJ et al. (1996) Modulation of microsomal cytochrome P450 by Scutellariae radix and Gentianae Scabrae Radix. Am. J. Chinese Med. 24, 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota T et al. (2000) PC‐SPES: a unique inhibitor of proliferation of prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo . Prostate 42, 163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA (1998) Cancer statistics. Cancer J. Clin. 48, 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legler JM, Fener EJ, Potosky JL, Merrill RM, Kramer BS (1998) Cancer Causes Control. 9, 519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J Jr & Berger ER (1997) New Guidelines for Surviving Prostate Cancer. Westbury, NY: Health Education Literary Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Lin CC & Shieh DE (1996) The anti‐inflammatory activity of Scutellaria rivularis extracts and its active components, baicalin, baicalein and wogonin. Am. J. Chin. Med. 24, 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W et al. (1998) The herbal medicine sho‐saiko‐to inhibits the growth of malignant melanoma cells by upregulating Fas‐mediated apoptosis and arresting cell cycle through downregulation of cyclin dependent kinases. Int. J. Oncol. 12, 1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman A, Tiwari RK, Chen S, Geliebter J (1999) Preclinical analysis of the in vivo and in vitro effects of PC‐SPES on rat prostate cancer cells. Ann. Mtng Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol., Abstract # 700.

- Muraki J et al. (1990) Establishment of new human prostatic cancer cell line (JCA‐1). Urology 36, 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto R, Motozuka T, Nakano M, Tatsumi Y, Sakamoto F, Kosaka N (1998) The chemical structure of new substances as the metabolite of baicalin and time profiles for the plasma concentration after oral administration of sho‐ saiko‐to in humans. J. Pharmaceut. Soc. Japan 118, 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Moriguchi R, Suzuki Y, Tomimori T, Yamada H (1995) Mode of action of the anti‐influenza virus activity of plant flavonoid, 5,7,4′‐trihydroxy‐8‐methoxyflavone, from the roots of Scutellaria baicalensis. Antiviral Res. 26, 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh WK, George DJ, Kantoff PW (2000) Activity of the herbal combination, PC‐SPES, in androgen‐independent (AI) prostate cancer (PC) patients, Ann. Mtng Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol., Abstract # 1374.

- Okita K, Li Q, Murakamio T, Takahashi M (1993) Anti‐growth effects with components of sho‐saiko‐to (TJ‐9) on cultured human hepatoma cells. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2, 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer BL, Pirani JF, Hamann SR, Klippel KF (2000) PC‐SPES a dietary supplement in the treatment of hormone refractory prostate cancer. Br. J. Urol. 85, 481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portfield H (1999) Survey of Us Too members and other prostate cancer patients to evaluate the efficacy of PC/SPES as well as toxicity and side effects, if any. Mol. Urol. 3, 333–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Fazal F, Greensill J, Ainley K, Parish JH, Hadi SM (1992) Strand scission in DNA induced by dietary flavonoids: role of Cu (I) and oxygen free radicals and biological consequences of scission. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 111, 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao ZH et al. (1999) Extract from Scutellaria baicalensis georgi attenuates oxidant stress in cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 31, 1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small EJ (1998) PC‐SPES in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 339, 567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small EJ et al. (2000) Prospective trial of the herbal supplement PC‐SPES in patients with progressive prostate cancer. J. Clin. Urol. 18, 3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari RK et al. (1999) Anti‐tumor effects of PC‐SPES, an herbal formulation, in prostate cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 14, 713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SR, Guo ZQ, Liao JZ (1993) Experimental study on effects of 18 kinds of Chinese herbal medicine for synthesis of thromboxane A2 and PGI2. Chung-Kuo-Chung-His-I-Chieh-Ho-Tsa-Chih 13, 167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu KJ, Wang YH, Hu JR, Wu LH, Sun KX (1994) Pharmacodynamics and clinical therapeutic effects of aerosol and injection of shuanghuaglian. Chung Kuo Chung Yao Tsa Chi 19, 689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano H et al. (1994) The herbal medicine Sho‐saiko‐to inhibits proliferation of cancer cell lines by inducing apoptosis and arrest at the G0/G1 phase. Cancer Res. 54, 448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi T, Narita M, Nagai E, Hagiwara H, Aburada M, Kamataki T (1995) Inhibition of UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase by aglycons of natural glucuronides in kampo medicines using SN‐38 as a substrate. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 86, 985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino M & Murakami K (1998) Interaction of iron with polyphenolic compounds: application to antioxidant characterization. Anal. Biochem. 257, 40s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]