Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer‐related death globally. Chemotherapy regimens consisting of 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU) in combination with either oxaliplatin or irinotecan are the first‐line options for treatment of metastatic CRC. However, primary or acquired resistance to these chemotherapeutics is a major clinical challenge. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a group of small non‐coding RNAs that regulate gene expression post‐transcriptionally. miRNAs play important roles in many cancer‐related processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis and invasion, and their dysregulation is implicated in colorectal tumourigenesis. Pertinent to chemotherapy, increasing evidence has revealed that miRNAs can be directly linked to chemosensitivity in CRC. In this review, we summarize current evidence concerning the role of miRNAs in prediction and modulation of cellular responses to 5‐FU, oxaliplatin and irinotecan in CRC. We also discuss the possible targets and intracellular pathways involved in these processes.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer‐related death in the world 1. Its incidence in many developing countries has increased 2‐ to 4‐fold over the last two decades and has now reached an alarming level 2. Prognosis of CRC is heterogeneous with 20–25% of patients presenting with metastases at diagnosis, and 50–60% of the remainder eventually developed disseminating disease 3. Localized CRC lesions can be removed surgically but half CRC patients survive <5 years subsequently, due to metastasis (principally) to the liver and lungs. Numbers of regimens, including FOLFOX (5‐fluorouracil [5‐FU], leucovorin and oxaliplatin), FOLFIRI (5‐FU, leucovorin and irinotecan) and XELOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) with or without cetuximab (an epidermal growth factor receptor‐directed monoclonal antibody) or bevacizumab (a vascular endothelial growth factor‐targeting monoclonal antibody), are the first‐line chemotherapeutic options for metastatic CRC 4. However, primary or acquired resistance is a major challenge to its successful treatment 5. Emerging evidence has shed new light on molecular mechanisms underlying resistance to commonly used chemotherapeutics. Understanding of these molecular events is key to improving prediction of treatment response and guiding treatment decisions in patients with metastatic CRC.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a group of small (19–25 nucleotides), non‐coding RNAs that regulate gene expression post‐transcriptionally 6, 7. Through partial or complete binding to the 3′ untranslated region (3′‐UTR) of their target mRNAs, single‐stranded miRNAs can lead to blocking translation or mRNA degradation. miRNAs play significant roles in many biological and pathophysiological processes, including development, host defence, aging and tumourigenesis 7, 8, 9, 10. Most importantly, they exhibit differential expression in many, if not all, types of cancers, including CRC 6. Aberrant expression of miRNAs has been observed in many malignancies, where they function as either onco‐miRNAs or tumour‐suppressor miRNAs 11. Considering their extensive interactions with intracellular signalling networks, miRNAs regulate many cancer‐pertinent cellular processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion, stemness and chemoresistance 6, 7. Importantly, a subset of miRNAs may serve as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers. With further advancement of RNA delivery technology, it is also anticipated that novel miRNA‐based therapeutics will emerge 12.

In the present review, we summarize results from the published literature on the role of miRNAs in prediction and response modification to three conventional chemotherapeutics, namely 5‐FU, oxaliplatin and irinotecan, in CRC. We also discuss possible involved molecular targets and intracellular pathways.

5‐fluorouracil and capecitabine

The fluoropyrimidine 5‐FU is an anti‐metabolite that exerts its anti‐cancer effects through inhibition of thymidylate synthase, and incorporation of its metabolites into RNA and DNA 13. Capecitabine was initially developed as a prodrug of 5‐FU with improved tolerability that could achieve higher intratumoural concentrations through tumour‐specific metabolic activation 14.

Drug effects on miRNA expression

Effects of 5‐FU on miRNA expression were determined in C22.20 and HC.21 colon cancer cell clones. Seventeen up‐regulated (miR‐19a, miR‐20, miR‐21, miR‐23a, miR‐25, miR‐27a/b, miR‐29a, miR‐30e, miR‐124b, miR‐132, miR‐133a, miR‐141, miR‐147, miR‐151, miR‐182, miR‐185) and three down‐regulated (miR‐200b, miR‐210, miR‐224) miRNAs were identified in both lines after exposure to 5‐FU 15. 5‐FU also dose‐dependently reduced primary transcript levels of miR‐17‐92 cluster in human colon cancer KM12C cells 16. Akao et al. reported that 5‐FU exposure stimulated miR‐145 and miR‐34a expression in DLD‐1 cells 17 and miR‐19b and miR‐21 were found to be overexpressed in 5‐FU‐resistant CRC cells 18. The effect of capecitabine in combination with radiotherapy on miRNA expression was also investigated in tumour biopsies from patients with rectal cancer before and after therapy. Two miRNAs, miR‐125b and miR‐137, had consistent increase in expression levels 19.

Autophagy has been increasingly recognized as a pro‐survival cellular response activated in times of stress during chemotherapy 20. Hou et al. reported that 5‐FU down‐regulated four miRNAs (miR‐302a‐3p, miR‐548ah‐5p, miR‐133b, miR‐323a‐3p) and up‐regulated 27 miRNAs (miR‐203a, miR‐99b‐5p, miR‐195‐5p, let‐7c‐5p, miR‐320d, miR‐301a‐3p, miR‐30e‐5p, miR‐374c‐5p, miR‐181a‐5p, let‐7g‐5p, miR‐513b‐5p, miR‐30b‐5p, miR‐19b‐3p, miR‐19a‐3p, miR‐15a‐5p, miR‐106b‐5p, miR‐330‐3p, miR‐582‐5p, miR‐16‐5p, miR‐30a‐5p, miR‐23a‐3p, miR‐26b‐5p, miR‐98‐5p, miR‐186‐5p, miR‐30d‐5p, miR‐93‐5p, miR‐320c) that had the predicted target genes involved in regulation of autophagy in HT‐29 cells. These miRNAs also exhibited concordant alteration of expression upon starvation, in the same cell line 21.

Modulation of chemosensitivity

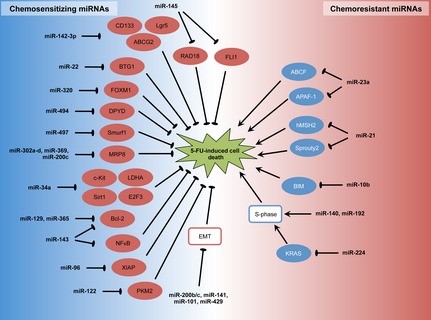

Modulation of cellular responsiveness to 5‐FU by chemosensitizing and chemoresistant miRNAs is illustrated in Fig. 1. miR‐494 was found to be down‐regulated in 5‐FU‐resistant SW480 cells compared to the parental cell line, whereas ectopic expression of miR‐494 increased sensitivities of CRC cell lines and chemoresistant SW40 xenografts to 5‐FU. Mechanistically, miR‐494 targeted DPYD, required for miR‐494‐mediated regulation of 5‐FU sensitivity 22 and likewise, miR‐22‐mediated inhibition of autophagy by targeting B‐cell translocation gene 1 (BTG1) is implicated in enhanced chemosensitivity to 5‐FU in CRC cells 23.

Figure 1.

Modulation of 5‐FU chemosensitivity by chemosensitizing and chemoresistant miRNAs in CRC.

Chemoresistance has been linked to epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT). To this end, up‐regulation of a group of EMT‐suppressive miRNAs (miR‐200b, miR‐200c, miR‐141, miR‐429 and miR‐101) has been implicated in the chemosensitizing effect of curcumin (a botanical substance with claimed anti‐tumourigenic properties) in 5‐FU‐resistant CRC cells 24. Restored expression of miR‐320, a tumour‐suppressive miRNA down‐regulated in CRC, also sensitized CRC cells to 5‐FU and oxaliplatin. In this regard, miR‐320 was shown to target Forkhead box M1 (FOXM1) that has an established role in chemoresistance in various types of tumour 25. miRNA‐497 levels correlated with 5‐FU sensitivity in CRC cells in which restoration of miRNA‐497 enhanced 5‐FU sensitivity. miRNA‐497 targeted Smurf1 whose expression levels were dramatically increased in 5‐FU‐resistant patients compared to treatment‐sensitive patients 26. Transfection of stemness‐related miRNAs (miR‐302a‐d, miR‐369‐3p and 5p, miR‐200c) has been shown to reprogramme CRC cells and enhance their sensitivity to 5‐FU probably through down‐regulating MRP8 that mediates cellular efflux of the toxic metabolite of 5‐FU 27. Ectopic expression of p53‐target miR‐34a sensitized CRC cells to 5‐FU by targeting lactate dehydrogenase A, c‐Kit, Sirt1 and E2F3 28, 29, 30, whereas inhibition of let‐7a conferred resistance to 5‐FU and radiation in CRC cells with single or double wild‐type TP53 alleles 31. miR‐142‐3p also elevated sensitivity of CRC cells to 5‐FU, which was paralleled by down‐regulation of CD133, Lgr5 and ABCG2 32. Restoration of miR‐143 and miR‐365 expression also promoted 5‐FU‐induced cell death, an effect probably mediated by repression of their common target Bcl‐2 (an anti‐apoptotic protein) 33, 34. Besides Bcl‐2, miR‐143 reduced extracellular‐regulated protein kinase 5 and nuclear factor‐κB 34. Aside from abovementioned miRNAs, miR‐96, miR‐122, miR‐129, miR‐145, miR‐203 and miR‐497 have been reported to enhance chemosensitivity to 5‐FU in CRC through down‐regulating XIAP, PKM2, Bcl‐2, RAD18, thymidylate synthase and IGF1‐R respectively 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40. miR‐145 may also target the Friend leukaemia virus integration 1 gene (FLI1) in CRC 41.

miRNA‐23a and miR‐31 conferred resistance to 5‐FU in CRC cells in which the former targeted ABCF1 and apoptosis‐activating factor‐1 (APAF‐1) 42, 43, 44. miR‐21 also increased resistance of tumour cells to 5‐FU in CRC by directly targeting hMSH2, an important DNA mismatch repair gene 45, 46. Inhibition of miR‐21 also promoted cell differentiation accompanied by enhanced sensitivity to 5‐FU and oxaliplatin in CRC, in which direct targeting of the tumour suppressor gene sprouty2 has been demonstrated 47, 48. miR‐10b overexpression conferred chemoresistance to 5‐FU by targeting pro‐apoptotic BIM 49 and expression of miR‐520g correlated with 5‐FU resistance of CRC cells. Ectopic expression of miR‐520g attenuated 5‐FU‐induced apoptosis in vitro and reduced effectiveness of 5‐FU in inhibition of CRC tumour growth, in a mouse xenograft model. It has been proposed that miR‐520g mediates 5‐FU resistance by down‐regulation of p21 50, but nevertheless in the literature, contradictory evidence exists concerning the role of p21 in cellular responses to 5‐FU. For instance, antagonizing endogenous miR‐192 has been shown to attenuate 5‐FU‐induced accumulation of p21, thereby shifting 5‐FU's effect towards apoptosis 51.

In addition to direct inhibition of specific target genes, miRNAs have been shown to influence 5‐FU sensitivity by non‐specific mechanisms. In this respect, miR‐140 and miR‐192 increase resistance to 5‐FU probably by reducing S‐phase cells and thereby mitigating effects of S phase‐specific drugs, including 5‐FU 52, 53. miR‐224 is also involved in chemoresistance to 5‐FU in CRC where its knock‐down phenocopied KRAS mutation by increasing KRAS activity with ERK and AKT phosphorylation increasing 5‐FU chemosensitivity 54.

Response prediction

Polymorphisms in two microRNA genes (miR‐608 and miR‐219‐1) have been reported to be predictors of clinical outcomes in CRC patients receiving 5‐FU‐based chemotherapy. In this regard, carriers of the variant T allele of rs213210 in miR‐219‐1 had shorter overall survival, whereas variant G allele of rs4919510 in miR‐608 was associated with reduced risk of recurrence. No such associations were found in the group of CRC patients not treated with 5‐FU‐based chemotherapy 55. Variations in miRNA‐binding sites in BER gene 3′‐UTR also modulate CRC response to 5‐FU‐based chemotherapy 56.

Stage II/III CRC patients receiving 5‐FU‐based chemotherapy with high tissue levels of miR‐200a, miR‐200c, miR‐141 or miR‐429 had significantly longer overall and disease‐free survival 57. In contrast, high levels of miR‐125b and miR‐137 were associated with worse response to capecitabine‐based chemoradiotherapy 19. Svoboda et al. also reported that miR‐215, miR‐190b and miR‐29b‐2* were overexpressed in non‐responders, while let‐7e, miR‐196b, miR‐450a, miR‐450b‐5p and miR‐99a* had higher expression levels in responders to 5‐FU‐ or capecitabine‐based chemoradiotherapy 58. Low miR‐148a or high miR‐320e expression also correlated with a poorer response to 5‐FU‐based chemotherapy in advanced CRC patients 59, 60. High miR‐320e was associated with adverse clinical outcome in stage III CRC patients treated with 5‐FU‐based adjuvant chemotherapy 59. miR‐21 had predictive significance of pathological response to 5‐FU‐based neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer patients, yielding an area under the curve value of 0.78 with 86.6% sensitivity and 60.0% specificity, in distinguishing rectal cancer from complete response to non‐complete response 61. let‐7g and miR‐181b levels were strongly associated with CRC patients' response to the 5‐fluorouracil‐based anti‐metabolite S‐1 62.

Circulating miRNAs have been utilized to predict CRC patients' responses to chemotherapy. Changes in circulating miRNA‐126 levels during treatment were predictive of tumour response in metastatic CRC patients treated with capecitabine and oxaliplatin combined with bevacizumab. Non‐responding patients had median increases in circulating miRNA‐126 of 0.244 compared to median reduction of −0.374 in responding patients 63. Aberrant elevation of a further circulating miRNA, miR‐19a, also predicted non‐responders to FOLFOX chemotherapy in advanced CRC 64. Re‐elevation or sustained elevation of serum miR‐155 levels after surgery and chemotherapy also foreshadowed chemoresistance in CRC patients treated with 5‐FU and leucovorin plus cetuximab 65. In contrast, reduction in blood miR‐296 predicted chemotherapy resistance and poor clinical outcome in patients receiving capecitabine and sunitinib 66.

Oxaliplatin

Oxaliplatin is a diaminocyclohexane‐containing platinum‐based anti‐neoplastic agent that exerts its cytotoxic action through diverse mechanisms, including induction of DNA lesions through adduct formation, arrest of DNA synthesis, inhibition of mRNA synthesis and triggering of immunological reactions 67.

Drug effects on miRNA expression

Zhou et al. profiled miRNA expression in two CRC cell lines (HCT‐8 and HCT‐116) exposed to oxaliplatin. Although oxaliplatin altered expression of multiple miRNAs in respective cell lines, only miR‐151‐5p and miR‐1826 were found to be commonly down‐regulated 68. One further study identified miR‐203 as the sole up‐regulated miRNA in all three tested oxaliplatin‐resistant CRC cell lines compared to their parental lines 69.

Modulation of chemosensitivity

Kalimutho et al. compared mechanisms of tumour sensitivity to satraplatin versus oxaliplatin and found that loss of p53‐mediated miR‐34a expression increased resistance to oxaliplatin but not to satraplatin 70. miR‐520g, a miRNA negatively regulated by p53, also conferred resistance to oxaliplatin by targeting p21 in CRC cells 51. By microRNA expression array and quantitative reverse transcription‐PCR, Chai et al. found that chemoresistant SW620 cells had elevated miR‐20a expression compared to chemosensitive SW480 cells. Knock‐down of miR‐20a sensitized SW620 cells to oxaliplatin, whereas its overexpression conferred resistance to the drug in SW480 cells. BNIP2, a Bcl‐2‐interacting partner, has been confirmed to be the direct target of miR‐20a 71. Ectopic expression of miR‐203 induced oxaliplatin resistance in CRC cells, whereas miR‐203 inhibitor produced the opposite effect. Such actions were mediated through its negative regulation of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), a primary mediator of DNA damage response 69. LIN28B, a negative regulator of the let‐7 microRNA family, also conferred resistance to oxaliplatin in SW480 and HCT116 colon cancer cells 72.

Response prediction

A set of 13 miRNAs (up‐regulated: miR‐1183, miR‐483‐5p, miR‐622, miR‐125a‐3p, miR‐1224‐5p, miR‐188‐5p, miR‐1471, miR‐671‐5p, miR‐1909∗, miR‐630, miR‐765; down‐regulated: miR‐1274b, miR‐720) is strongly associated with complete pathological response in rectal cancer patients receiving oxaliplatin–capecitabine and radiotherapy before surgery. Of these, miR‐622 and miR‐630 had a 100% sensitivity and specificity in selecting responsive cases 73. miRNA‐126, the only known endothelial cell‐specific miRNA that may be used as a surrogate marker of angiogenesis, has also been shown to predict response to oxaliplatin and capecitabine in patients with metastatic CRC 74, 75. In KRAS‐mutated tumours, increased miR‐200b and reduced miR‐143 expression were associated with better progression‐free survival in patients treated with oxaliplatin in combination with capecitabine, cetuximab and bevacizumab 76. High miR‐320e expression was associated with worse therapeutic response in advanced CRC patients treated with oxaliplatin‐ and 5‐FU‐based chemotherapy 59, whereas high expression of miR‐196b‐5p and miR‐592 predicted improved outcome of XELOX regimen (oxaliplatin and capecitabine) with or without bevacizumab 77. Five serum miRNAs (miR‐20a, miR‐130, miR‐145, miR‐216 and miR‐372) that were significantly up‐regulated in oxaliplatin‐chemoresistant CRC patients also predicted chemotherapeutic response with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.841 and 0.918 in two independent cohorts 78.

Irinotecan

Irinotecan, also known as CPT‐11, is a derivative of camptothecin. It prevents religation of the DNA strand by inhibiting action of topoisomerase I, thereby causing double‐strand DNA breakage that leads to apoptosis or premature senescence 79.

Drug effects on miRNA expression

Cellular changes in miRNA expression upon irinotecan treatment in CRC remain largely uncharacterized. To this end, only the effect of irinotecan on expression of senescence‐related miRNAs in normal colonic fibroblasts or normal colonocytes has been investigated. In this regard, strong up‐regulation of miR‐34a, miR‐128a and miR‐449a has been associated with premature senescence in irinotecan‐treated colonic fibroblasts. In contrast, irinotecan has been found to only moderately increase expression of miR‐34a, but had no significant effect on the other two miRNAs, in normal colonocytes, which underwent apoptosis upon treatment 80.

Modulation of chemosensitivity

Evidence concerning effects of miRNA on responsiveness to irinotecan in CRC remains scarce. Chemoresistance is a common property of cancer stem cells. miR‐451 has been found to be down‐regulated in colonspheres with CRC stem cell properties compared to parental cells. Concordantly, restored expression of miR‐451 caused a reduction in self‐renewal, tumourigenicity and chemoresistance to irinotecan 81.

Response prediction

miRNA expression levels, or polymorphisms of miRNA genes or miRNA‐binding sites on targets, have been shown to predict response to irinotecan‐based chemotherapy. In metastatic CRC patients treated with salvage cetuximab–irinotecan, Graziano et al. reported that G‐allele carriers of the let‐7 complementary site in the KRAS 3′‐UTR, displayed worse overall survival (P = 0.001) and progression‐free survival (P = 0.004) than T/T genotype carriers. Multivariate analysis revealed that prognostic significance of this variant was independent of other clinicopathological parameters, including KRAS mutation status 82. A subsequent study by the same group further revealed that higher let‐7a levels were significantly associated with better survival outcomes in this cohort of patients 83. For miRNA genes, Boni et al. found that single‐nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs7372209 and rs1834306 in pri‐miR26a‐1 and pri‐miR‐100 genes, respectively, were associated with tumour response and/or time to progression in metastatic CRC patients treated with irinotecan and 5‐FU 84. In metastatic CRC patients receiving cetuximab or panitumab (another epidermal growth factor receptor‐directed monoclonal antibody) with or without irinotecan, low levels of miR‐31* and high levels of miR‐592 in tumour tissues, favoured disease control over progressive disease 85. A recent study further reported that high circulating levels of miR‐345 were associated with lack of response to treatment with cetuximab and irinotecan in metastatic CRC 86.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

miRNAs are a class of small, non‐coding RNA molecules regulating gene expression at post‐transcriptional levels. Accumulating evidence has implicated that miRNAs could be used to predict clinical outcomes of treatment, as well as modulate efficacy of anti‐cancer chemotherapy. In our review, alterations in miRNA expression profiles have been found to predict the success of 5‐FU‐, oxaliplatin‐ and irinotecan‐based chemotherapy in CRC. Furthermore, miRNAs seem to regulate cancer cell sensitivity to these drugs. Thus, combining miRNAs with existing chemotherapeutic agents might be used to maximize therapeutic effect and improve clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic CRC. However, detailed mechanisms and intracellular pathways in miRNA regulation of chemosensitivity in CRC remain largely unspecified. Further investigations are needed for systematic identification of miRNAs involved in modulation of chemosensitivity as well as their associated molecular targets and signalling pathways. In addition, many functional studies have been conducted with CRC cell lines in vitro with limited numbers of studies reporting results from mouse xenograft models. There is also no study as yet on safety and efficacy of miRNA‐based treatment in humans; in time, this will be investigated.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant number: 81401847).

Xin Yu and Zheng Li contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 61, 69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sung JJ, Lau JY, Goh KL, Leung WK, Asia Pacific Working Group on Colorectal C (2005) Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia: implications for screening. Lancet Oncol. 6, 871–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Edwards MS, Chadda SD, Zhao Z, Barber BL, Sykes DP (2012) A systematic review of treatment guidelines for metastatic colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 14, e31–e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Cutsem E, Rivera F, Berry S, Kretzschmar A, Michael M, DiBartolomeo M et al (2009) Safety and efficacy of first‐line bevacizumab with FOLFOX, XELOX, FOLFIRI and fluoropyrimidines in metastatic colorectal cancer: the BEAT study. Ann. Oncol. 20, 1842–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Temraz S, Mukherji D, Alameddine R, Shamseddine A (2014) Methods of overcoming treatment resistance in colorectal cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 89, 217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu WK, Law PT, Lee CW, Cho CH, Fan D, Wu K et al (2011) MicroRNA in colorectal cancer: from benchtop to bedside. Carcinogenesis 32, 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu WK, Lee CW, Cho CH, Fan D, Wu K, Yu J et al (2010) MicroRNA dysregulation in gastric cancer: a new player enters the game. Oncogene 29, 5761–5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foster PS, Plank M, Collison A, Tay HL, Kaiko GE, Li J et al (2013) The emerging role of microRNAs in regulating immune and inflammatory responses in the lung. Immunol. Rev. 253, 198–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith‐Vikos T, Slack FJ (2012) MicroRNAs and their roles in aging. J. Cell Sci. 125, 7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sonkoly E, Pivarcsi A (2009) microRNAs in inflammation. Int. Rev. Immunol. 28, 535–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang B, Pan X, Cobb GP, Anderson TA (2007) microRNAs as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Dev. Biol. 302, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dong Y, Wu WK, Wu CW, Sung JJ, Yu J, Ng SS (2011) MicroRNA dysregulation in colorectal cancer: a clinical perspective. Br. J. Cancer 104, 893–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Longley DB, Harkin DP, Johnston PG (2003) 5‐fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Walko CM, Lindley C (2005) Capecitabine: a review. Clin. Ther. 27, 23–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rossi L, Bonmassar E, Faraoni I (2007) Modification of miR gene expression pattern in human colon cancer cells following exposure to 5‐fluorouracil in vitro . Pharmacol. Res. 56, 248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao HY, Ooyama A, Yamamoto M, Ikeda R, Haraguchi M, Tabata S et al (2008) Down regulation of c‐Myc and induction of an angiogenesis inhibitor, thrombospondin‐1, by 5‐FU in human colon cancer KM12C cells. Cancer Lett. 270, 156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akao Y, Khoo F, Kumazaki M, Shinohara H, Miki K, Yamada N (2014) Extracellular disposal of tumor‐suppressor miRs‐145 and ‐34a via microvesicles and 5‐FU resistance of human colon cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 1392–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kurokawa K, Tanahashi T, Iima T, Yamamoto Y, Akaike Y, Nishida K et al (2012) Role of miR‐19b and its target mRNAs in 5‐fluorouracil resistance in colon cancer cells. J. Gastroenterol. 47, 883–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Svoboda M, Izakovicova Holla L, Sefr R, Vrtkova I, Kocakova I, Tichy B et al (2008) Micro‐RNAs miR125b and miR137 are frequently upregulated in response to capecitabine chemoradiotherapy of rectal cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 33, 541–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu WK, Coffelt SB, Cho CH, Wang XJ, Lee CW, Chan FK et al (2012) The autophagic paradox in cancer therapy. Oncogene 31, 939–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hou N, Han J, Li J, Liu Y, Qin Y, Ni L et al (2014) MicroRNA profiling in human colon cancer cells during 5‐fluorouracil‐induced autophagy. PLoS ONE 9, e114779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chai J, Dong W, Xie C, Wang L, Han DL, Wang S et al (2015) MicroRNA‐494 sensitizes colon cancer cells to fluorouracil through regulation of DPYD. IUBMB Life 67, 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang H, Tang J, Li C, Kong J, Wang J, Wu Y et al (2015) MiR‐22 regulates 5‐FU sensitivity by inhibiting autophagy and promoting apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 356, 781–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Toden S, Okugawa Y, Jascur T, Wodarz D, Komarova NL, Buhrmann C et al (2015) Curcumin mediates chemosensitization to 5‐fluorouracil through miRNA‐induced suppression of epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition in chemoresistant colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis 36, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wan LY, Deng J, Xiang XJ, Zhang L, Yu F, Chen J et al (2015) miR‐320 enhances the sensitivity of human colon cancer cells to chemoradiotherapy in vitro by targeting FOXM1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 457, 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu L, Zheng W, Song Y, Du X, Tang Y, Nie J et al (2015) miRNA‐497 Enhances the Sensitivity of Colorectal Cancer Cells to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapeutic Drug. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 16, 310–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miyazaki S, Yamamoto H, Miyoshi N, Wu X, Ogawa H, Uemura M et al (2014) A Cancer Reprogramming Method Using MicroRNAs as a Novel Therapeutic Approach against Colon Cancer : Research for Reprogramming of Cancer Cells by MicroRNAs. Ann. Surg. Oncol. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li X, Zhao H, Zhou X, Song L (2015) Inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase A by microRNA‐34a resensitizes colon cancer cells to 5‐fluorouracil. Mol. Med. Rep. 11, 577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Siemens H, Jackstadt R, Kaller M, Hermeking H (2013) Repression of c‐Kit by p53 is mediated by miR‐34 and is associated with reduced chemoresistance, migration and stemness. Oncotarget 4, 1399–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akao Y, Noguchi S, Iio A, Kojima K, Takagi T, Naoe T (2011) Dysregulation of microRNA‐34a expression causes drug‐resistance to 5‐FU in human colon cancer DLD‐1 cells. Cancer Lett. 300, 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luu C, Heinrich EL, Duldulao M, Arrington AK, Fakih M, Garcia‐Aguilar J et al (2013) TP53 and let‐7a micro‐RNA regulate K‐Ras activity in HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. PLoS ONE 8, e70604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shen WW, Zeng Z, Zhu WX, Fu GH (2013) MiR‐142‐3p functions as a tumor suppressor by targeting CD133, ABCG2, and Lgr5 in colon cancer cells. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 91, 989–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nie J, Liu L, Zheng W, Chen L, Wu X, Xu Y et al (2012) microRNA‐365, down‐regulated in colon cancer, inhibits cell cycle progression and promotes apoptosis of colon cancer cells by probably targeting Cyclin D1 and Bcl‐2. Carcinogenesis 33, 220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borralho PM, Kren BT, Castro RE, da Silva IB, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM (2009) MicroRNA‐143 reduces viability and increases sensitivity to 5‐fluorouracil in HCT116 human colorectal cancer cells. FEBS J. 276, 6689–6700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu RL, Dong Y, Deng YZ, Wang WJ, Li WD (2015) Tumor suppressor miR‐145 reverses drug resistance by directly targeting DNA damage‐related gene RAD18 in colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim SA, Kim I, Yoon SK, Lee EK, Kuh HJ (2015) Indirect modulation of sensitivity to 5‐fluorouracil by microRNA‐96 in human colorectal cancer cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 38, 239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li T, Gao F, Zhang XP (2015) miR‐203 enhances chemosensitivity to 5‐fluorouracil by targeting thymidylate synthase in colorectal cancer. Oncol. Rep. 33, 607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. He J, Xie G, Tong J, Peng Y, Huang H, Li J et al (2014) Overexpression of microRNA‐122 re‐sensitizes 5‐FU‐resistant colon cancer cells to 5‐FU through the inhibition of PKM2 in vitro and in vivo. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 70, 1343–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Karaayvaz M, Zhai H, Ju J (2013) miR‐129 promotes apoptosis and enhances chemosensitivity to 5‐fluorouracil in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 4, e659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guo ST, Jiang CC, Wang GP, Li YP, Wang CY, Guo XY et al (2013) MicroRNA‐497 targets insulin‐like growth factor 1 receptor and has a tumour suppressive role in human colorectal cancer. Oncogene 32, 1910–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang J, Guo H, Zhang H, Wang H, Qian G, Fan X et al (2011) Putative tumor suppressor miR‐145 inhibits colon cancer cell growth by targeting oncogene Friend leukemia virus integration 1 gene. Cancer 117, 86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li X, Li X, Liao D, Wang X, Wu Z, Nie J et al (2015) Elevated microRNA‐23a Expression Enhances the Chemoresistance of Colorectal Cancer Cells with Microsatellite Instability to 5‐Fluorouracil by Directly Targeting ABCF1. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 16, 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shang J, Yang F, Wang Y, Wang Y, Xue G, Mei Q et al (2014) MicroRNA‐23a antisense enhances 5‐fluorouracil chemosensitivity through APAF‐1/caspase‐9 apoptotic pathway in colorectal cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 115, 772–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang CJ, Stratmann J, Zhou ZG, Sun XF (2010) Suppression of microRNA‐31 increases sensitivity to 5‐FU at an early stage, and affects cell migration and invasion in HCT‐116 colon cancer cells. BMC Cancer 10, 616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Deng J, Lei W, Fu JC, Zhang L, Li JH, Xiong JP (2014) Targeting miR‐21 enhances the sensitivity of human colon cancer HT‐29 cells to chemoradiotherapy in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 443, 789–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Valeri N, Gasparini P, Braconi C, Paone A, Lovat F, Fabbri M et al (2010) MicroRNA‐21 induces resistance to 5‐fluorouracil by down‐regulating human DNA MutS homolog 2 (hMSH2). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 21098–21103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yu Y, Sarkar FH, Majumdar AP (2013) Down‐regulation of miR‐21 Induces Differentiation of Chemoresistant Colon Cancer Cells and Enhances Susceptibility to Therapeutic Regimens. Transl. Oncol. 6, 180–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Feng YH, Wu CL, Shiau AL, Lee JC, Chang JG, Lu PJ et al (2012) MicroRNA‐21‐mediated regulation of Sprouty2 protein expression enhances the cytotoxic effect of 5‐fluorouracil and metformin in colon cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 29, 920–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nishida N, Yamashita S, Mimori K, Sudo T, Tanaka F, Shibata K et al (2012) MicroRNA‐10b is a prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer and confers resistance to the chemotherapeutic agent 5‐fluorouracil in colorectal cancer cells. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 19, 3065–3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang Y, Geng L, Talmon G, Wang J (2015) MicroRNA‐520g confers drug resistance by regulating p21 expression in colorectal cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 6215–6225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Braun CJ, Zhang X, Savelyeva I, Wolff S, Moll UM, Schepeler T et al (2008) p53‐Responsive micrornas 192 and 215 are capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res. 68, 10094–10104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boni V, Bitarte N, Cristobal I, Zarate R, Rodriguez J, Maiello E et al (2010) miR‐192/miR‐215 influence 5‐fluorouracil resistance through cell cycle‐mediated mechanisms complementary to its post‐transcriptional thymidilate synthase regulation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 9, 2265–2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Song B, Wang Y, Xi Y, Kudo K, Bruheim S, Botchkina GI et al (2009) Mechanism of chemoresistance mediated by miR‐140 in human osteosarcoma and colon cancer cells. Oncogene 28, 4065–4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Amankwatia EB, Chakravarty P, Carey FA, Weidlich S, Steele RJ, Munro AJ et al (2015) MicroRNA‐224 is associated with colorectal cancer progression and response to 5‐fluorouracil‐based chemotherapy by KRAS‐dependent and ‐independent mechanisms. Br. J. Cancer 112, 1480–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pardini B, Rosa F, Naccarati A, Vymetalkova V, Ye Y, Wu X et al (2015) Polymorphisms in microRNA genes as predictors of clinical outcomes in colorectal cancer patients. Carcinogenesis 36, 82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pardini B, Rosa F, Barone E, Di Gaetano C, Slyskova J, Novotny J et al (2013) Variation within 3'‐UTRs of base excision repair genes and response to therapy in colorectal cancer patients: a potential modulation of microRNAs binding. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 6044–6056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Diaz T, Tejero R, Moreno I, Ferrer G, Cordeiro A, Artells R et al (2014) Role of miR‐200 family members in survival of colorectal cancer patients treated with fluoropyrimidines. J. Surg. Oncol. 109, 676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Svoboda M, Sana J, Fabian P, Kocakova I, Gombosova J, Nekvindova J et al (2012) MicroRNA expression profile associated with response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer patients. Radiat. Oncol. 7, 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Perez‐Carbonell L, Sinicrope FA, Alberts SR, Oberg AL, Balaguer F, Castells A et al (2015) MiR‐320e is a novel prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 3, 83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Takahashi M, Cuatrecasas M, Balaguer F, Hur K, Toiyama Y, Castells A et al (2012) The clinical significance of MiR‐148a as a predictive biomarker in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 7, e46684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Carames C, Cristobal I, Moreno V, Del Puerto L, Moreno I, Rodriguez M et al (2015) MicroRNA‐21 predicts response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 30, 899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nakajima G, Hayashi K, Xi Y, Kudo K, Uchida K, Takasaki K et al (2006) Non‐coding MicroRNAs hsa‐let‐7g and hsa‐miR‐181b are Associated with Chemoresponse to S‐1 in Colon Cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 3, 317–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hansen TF, Carlsen AL, Heegaard NH, Sorensen FB, Jakobsen A (2015) Changes in circulating microRNA‐126 during treatment with chemotherapy and bevacizumab predicts treatment response in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 112, 624–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chen Q, Xia HW, Ge XJ, Zhang YC, Tang QL, Bi F (2013) Serum miR‐19a predicts resistance to FOLFOX chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer cases. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 14, 7421–7426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chen J, Wang W, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Hu T (2014) Predicting distant metastasis and chemoresistance using plasma miRNAs. Med. Oncol. 31, 799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shivapurkar N, Mikhail S, Navarro R, Bai W, Marshall J, Hwang J et al (2013) Decrease in blood miR‐296 predicts chemotherapy resistance and poor clinical outcome in patients receiving systemic chemotherapy for metastatic colon cancer. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 28, 887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Alcindor T, Beauger N (2011) Oxaliplatin: a review in the era of molecularly targeted therapy. Curr. Oncol. 18, 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhou J, Zhou Y, Yin B, Hao W, Zhao L, Ju W et al (2010) 5‐Fluorouracil and oxaliplatin modify the expression profiles of microRNAs in human colon cancer cells in vitro. Oncol. Rep. 23, 121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhou Y, Wan G, Spizzo R, Ivan C, Mathur R, Hu X et al (2014) miR‐203 induces oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer cells by negatively regulating ATM kinase. Mol. Oncol. 8, 83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kalimutho M, Minutolo A, Grelli S, Formosa A, Sancesario G, Valentini A et al (2011) Satraplatin (JM‐216) mediates G2/M cell cycle arrest and potentiates apoptosis via multiple death pathways in colorectal cancer cells thus overcoming platinum chemo‐resistance. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 67, 1299–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chai H, Liu M, Tian R, Li X, Tang H (2011) miR‐20a targets BNIP2 and contributes chemotherapeutic resistance in colorectal adenocarcinoma SW480 and SW620 cell lines. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 43, 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pang M, Wu G, Hou X, Hou N, Liang L, Jia G et al (2014) LIN28B promotes colon cancer migration and recurrence. PLoS ONE 9, e109169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Della Vittoria Scarpati G, Falcetta F, Carlomagno C, Ubezio P, Marchini S, De Stefano A et al (2012) A specific miRNA signature correlates with complete pathological response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 83, 1113–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hansen TF, Nielsen BS, Jakobsen A, Sorensen FB (2013) Visualising and quantifying angiogenesis in metastatic colorectal cancer : a comparison of methods and their predictive value for chemotherapy response. Cell Oncol. (Dordr). 36, 341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hansen TF, Sorensen FB, Lindebjerg J, Jakobsen A (2012) The predictive value of microRNA‐126 in relation to first line treatment with capecitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 12, 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mekenkamp LJ, Tol J, Dijkstra JR, de Krijger I, Vink‐Borger ME, van Vliet S et al (2012) Beyond KRAS mutation status: influence of KRAS copy number status and microRNAs on clinical outcome to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer 12, 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Boisen MK, Dehlendorff C, Linnemann D, Nielsen BS, Larsen JS, Osterlind K et al (2014) Tissue microRNAs as predictors of outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with first line Capecitabine and Oxaliplatin with or without Bevacizumab. PLoS ONE 9, e109430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhang J, Zhang K, Bi M, Jiao X, Zhang D, Dong Q (2014) Circulating microRNA expressions in colorectal cancer as predictors of response to chemotherapy. Anticancer Drugs 25, 346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Xu Y, Villalona‐Calero MA (2002) Irinotecan: mechanisms of tumor resistance and novel strategies for modulating its activity. Ann. Oncol. 13, 1841–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rudolf E, John S, Cervinka M (2012) Irinotecan induces senescence and apoptosis in colonic cells in vitro. Toxicol. Lett. 214, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bitarte N, Bandres E, Boni V, Zarate R, Rodriguez J, Gonzalez‐Huarriz M et al (2011) MicroRNA‐451 is involved in the self‐renewal, tumorigenicity, and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer stem cells. Stem Cells 29, 1661–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Graziano F, Canestrari E, Loupakis F, Ruzzo A, Galluccio N, Santini D et al (2010) Genetic modulation of the Let‐7 microRNA binding to KRAS 3'‐untranslated region and survival of metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with salvage cetuximab‐irinotecan. Pharmacogenomics J. 10, 458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ruzzo A, Graziano F, Vincenzi B, Canestrari E, Perrone G, Galluccio N et al (2012) High let‐7a microRNA levels in KRAS‐mutated colorectal carcinomas may rescue anti‐EGFR therapy effects in patients with chemotherapy‐refractory metastatic disease. Oncologist 17, 823–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Boni V, Zarate R, Villa JC, Bandres E, Gomez MA, Maiello E et al (2011) Role of primary miRNA polymorphic variants in metastatic colon cancer patients treated with 5‐fluorouracil and irinotecan. Pharmacogenomics J. 11, 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Mosakhani N, Lahti L, Borze I, Karjalainen‐Lindsberg ML, Sundstrom J, Ristamaki R et al (2012) MicroRNA profiling predicts survival in anti‐EGFR treated chemorefractory metastatic colorectal cancer patients with wild‐type KRAS and BRAF. Cancer Genet. 205, 545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Schou JV, Rossi S, Jensen BV, Nielsen DL, Pfeiffer P, Hogdall E et al (2014) miR‐345 in metastatic colorectal cancer: a non‐invasive biomarker for clinical outcome in non‐KRAS mutant patients treated with 3rd line cetuximab and irinotecan. PLoS ONE 9, e99886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]