Abstract

Background

Telephone services can provide information and support for smokers. Counselling may be provided proactively or offered reactively to callers to smoking cessation helplines.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of telephone support to help smokers quit, including proactive or reactive counselling, or the provision of other information to smokers calling a helpline.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register, clinicaltrials.gov, and the ICTRP for studies of telephone counselling, using search terms including 'hotlines' or 'quitline' or 'helpline'. Date of the most recent search: May 2018.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials which offered proactive or reactive telephone counselling to smokers to assist smoking cessation.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. We pooled studies using a random‐effects model and assessed statistical heterogeneity amongst subgroups of clinically comparable studies using the I2 statistic. In trials including smokers who did not call a quitline, we used meta‐regression to investigate moderation of the effect of telephone counselling by the planned number of calls in the intervention, trial selection of participants that were motivated to quit, and the baseline support provided together with telephone counselling (either self‐help only, brief face‐to‐face intervention, pharmacotherapy, or financial incentives).

Main results

We identified 104 trials including 111,653 participants that met the inclusion criteria. Participants were mostly adult smokers from the general population, but some studies included teenagers, pregnant women, and people with long‐term or mental health conditions. Most trials (58.7%) were at high risk of bias, while 30.8% were at unclear risk, and only 11.5% were at low risk of bias for all domains assessed. Most studies (100/104) assessed proactive telephone counselling, as opposed to reactive forms.

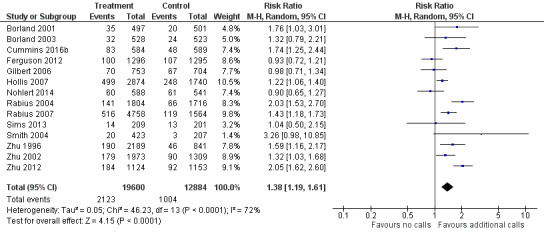

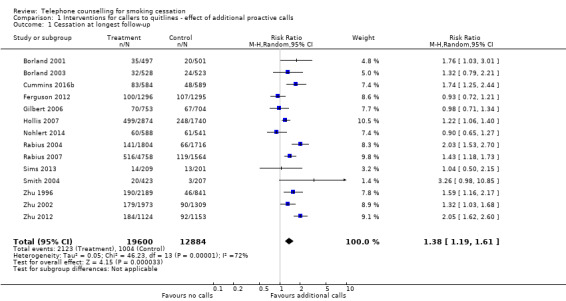

Among trials including smokers who contacted helplines (32,484 participants), quit rates were higher for smokers receiving multiple sessions of proactive counselling (risk ratio (RR) 1.38, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.19 to 1.61; 14 trials, 32,484 participants; I2 = 72%) compared with a control condition providing self‐help materials or brief counselling in a single call. Due to the substantial unexplained heterogeneity between studies, we downgraded the certainty of the evidence to moderate.

In studies that recruited smokers who did not call a helpline, the provision of telephone counselling increased quit rates (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.35; 65 trials, 41,233 participants; I2 = 52%). Due to the substantial unexplained heterogeneity between studies, we downgraded the certainty of the evidence to moderate. In subgroup analysis, we found no evidence that the effect of telephone counselling depended upon whether or not other interventions were provided (P = 0.21), no evidence that more intensive support was more effective than less intensive (P = 0.43), or that the effect of telephone support depended upon whether or not people were actively trying to quit smoking (P = 0.32). However, in meta‐regression, telephone counselling was associated with greater effectiveness when provided as an adjunct to self‐help written support (P < 0.01), or to a brief intervention from a health professional (P = 0.02); telephone counselling was less effective when provided as an adjunct to more intensive counselling. Further, telephone support was more effective for people who were motivated to try to quit smoking (P = 0.02). The findings from three additional trials of smokers who had not proactively called a helpline but were offered telephone counselling, found quit rates were higher in those offered three to five telephone calls compared to those offered just one call (RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.44; 2602 participants; I2 = 0%).

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate‐certainty evidence that proactive telephone counselling aids smokers who seek help from quitlines, and moderate‐certainty evidence that proactive telephone counselling increases quit rates in smokers in other settings. There is currently insufficient evidence to assess potential variations in effect from differences in the number of contacts, type or timing of telephone counselling, or when telephone counselling is provided as an adjunct to other smoking cessation therapies. Evidence was inconclusive on the effect of reactive telephone counselling, due to a limited number studies, which reflects the difficulty of studying this intervention.

Plain language summary

Does telephone counselling help people stop smoking?

Background

There are a number of interventions available to help people stop smoking. One of them is using telephone calls to give smokers information, advice, and help to stop smoking. People can use these services by calling quitlines or by signing up to get calls from counsellors. We wanted to find out whether telephone counselling can help people quit smoking. Our most recent search for evidence was in May 2018.

Study characteristics

We found 104 studies (including 111,653 participants) testing the effect of any type of telephone counselling. The participants were mostly adult smokers from the general population, but some studies also looked at teenagers, pregnant women, and people with long‐term or mental health conditions.

Some studies included participants who had called helplines that provide smoking counselling (quitlines). Other studies included people who had not called quitlines, but received calls from counsellors or other healthcare providers.

Some studies provided telephone counselling alone, but many others provided telephone counselling along with minimal support such as self‐help leaflets, or more active support such as face‐to‐face counselling, or with stop‐smoking medication. The number of calls offered ranged from a single call to 12 calls. Some studies only recruited people trying to stop smoking, while others offered support even to those not actively trying to stop.

Studies needed to compare groups whose participants had similar characteristics at the start of the study, to investigate whether the participants had stopped smoking for at least six months, and ideally would test whether people had quit with blood or urine tests.

We judged few studies to be well designed and conducted. Most had at least one issue that could have affected the results.

Key results

In people who had called helplines, providing additional telephone counselling increased their chances of stopping smoking from 7% to 10%. In people who had not called a helpline, but received telephone calls from counsellors or other healthcare providers, their chances of stopping smoking increased from 11% to 14%. In studies which directly compared more versus fewer calls, people who were offered more calls (three to five) tended to be more likely to quit than those who received only one call. Telephone counselling appears to increase the chances of stopping smoking, whether or not people are motivated to quit or are receiving other stop‐smoking support.

Certainty of evidence

The overall certainty of the evidence was moderate, meaning that further research is likely to have an important impact on our conclusions.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Worldwide, tobacco smoking kills more than seven million people each year, shortening life by an average of 10 to 11 years in people who smoke their whole lives (Doll 2004; Pirie 2013; WHO 2018). This increase in mortality is primarily due to cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but smoking is also causally associated with other cancer‐ and non‐cancer‐related health conditions (USDHHS 2014; WHO 2018). Smoking cessation reverses much of the damage, and most smokers who are aware of these health hazards wish to quit (Doll 2004; Mons 2015; Müezzinler 2015; Ordóñez‐Mena 2016; WHO 2018).

Description of the intervention

Telephone counselling is a behavioural intervention to help people stop smoking. It can act as a stand‐alone intervention or one that runs alongside other interventions (e.g. an added component to face‐to‐face counselling). It can be proactive (the counsellor initiates contact) or reactive (the smoker initiates contact) (Lichtenstein 1996). In many areas, reactive services are available through helplines or quitlines, which may be specific to smoking, as for example the California Smokers' Helpline (Zhu 2000a) and the Quitlines in Australia (Borland 2001), the UK (Owen 2000), Sweden (Lindqvist 2013), and Denmark (Skov‐Ettrup 2016), or they may be embedded in broader health information services such as the Cancer Information Service in the USA (La Porta 2007). Quitlines may provide a regional or national service. They are often advertised in conjunction with population‐wide campaigns such as No‐Smoking Days. Helplines may also be provided on a smaller scale for a specific project or population. In some services, people may be enrolled in a formal smoking cessation programme, with further proactive calls from counsellors. Telephone counselling may also be provided as part of an integrated smoking cessation support service (e.g. Glasgow 1991). Access to hotlines or the opportunity to register to receive calls from a counsellor may also be offered as part of a cessation programme, including pharmacotherapy.

How the intervention might work

Behavioural and pharmacological interventions help people to quit smoking. Behavioural support can be given in individual counselling sessions (Lancaster 2017) or in group therapy (Stead 2017), where clients can share problems and derive support from one another. Standard self‐help materials have at best a small effect in helping people to quit, while those tailored to the characteristics of individuals are more likely to be effective (Livingstone‐Banks 2019a). Telephone counselling may supplement face‐to‐face support, or be a substitute for it as an adjunct to self‐help interventions or pharmacotherapy. Counselling may be helpful in planning a quit attempt, and in helping to prevent relapse during the initial period of abstinence (Livingstone‐Banks 2019b). Although intensive face‐to‐face interventions increase quit rates, there are difficulties with scalability. Telephone counselling may be a more feasible way to provide individual counselling to large populations. In addition, telephone contact can be timed to maximise the level of support around a planned quit date, and can be scheduled in response to the needs of the recipient. In a proactive approach the counsellor initiates one or more calls to provide support in making a quit attempt or avoiding relapse. Reactive counselling, in contrast, is available on demand to people calling specific services; quitlines, helplines or hotlines. These services take calls from people who smoke, or their friends and family (Zhu 2006). These telephone services may offer information, recorded messages, personal counselling or a mixture of components (Anderson 2007; Ossip‐Klein 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

Telephone counselling services have the potential to provide access to information for large numbers of people. Some services have reported reaching substantial proportions of the target population (Ossip‐Klein 1991; Platt 1997). They have the potential to reach underserved populations such as ethnic minorities (Zhu 2000a) or younger people (Chan 2008; Gilbert 2005).

Telephone counselling is a widely used intervention for smoking cessation, and is often supported through public funds. It is therefore important to evaluate its effects, as well as different variations of telephone counselling that may impact on quit rates.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of telephone support to help smokers quit, including proactive or reactive counselling, or the provision of other information to smokers calling a helpline.

We tried to address the following questions:

Do telephone calls from a counsellor increase quit rates, compared to other brief non‐pharmacological interventions or to no intervention?

Do telephone calls from a counsellor offered together with other interventions increase quit rates, compared to other interventions alone?

Does an increase in the number of telephone contacts increase quit rates?

Do differences in counselling protocol related to the type or timing of support lead to differences in quit rates?

Does the availability of a reactive helpline increase quit rates?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with the unit of allocation being one of the following: the individual smoker; counsellor; group; intervention site; or geographical area.

Types of participants

Individuals who were current smokers at the time of inclusion in the trial. We included trials with a mixture of current smokers and recent quitters if the recent quitters were only a small proportion of the entire study population. The definition of recent quitters was that used by the trial recruitment protocols, or by the participants themselves. We excluded trials that exclusively recruited quitters or were focused on telephone counselling as an intervention for relapse, as they fall within the scope of a separate Cochrane Review on preventing relapse (Livingstone‐Banks 2019b).

We included trials recruiting exclusively teenagers or pregnant women, but we considered them as a potential source of heterogeneity in meta‐analyses. There are separate Cochrane Reviews for these population groups (Chamberlain 2017; Fanshawe 2017).

Types of interventions

Provision of proactive or reactive telephone counselling to assist smoking cessation, to any population. We excluded studies if the contribution of the telephone component could not be evaluated independently of another therapy. We included studies that compared a combination of telephone counselling and self‐help materials versus no telephone counselling, as the effect of self‐help materials alone is limited (Livingstone‐Banks 2019a). We also included studies in which the effect of telephone counselling as an adjunct to another smoking cessation treatment was evaluated, e.g. print‐based self‐help, brief face‐to‐face intervention, pharmacotherapy, or incentives. We also included studies that compared different modalities or strategies of telephone counselling, and different theories of behavioural change.

Types of outcome measures

Long‐term smoking cessation (i.e. at least six months after the start of intervention). We excluded trials with shorter follow‐up. We used the strictest definition of smoking cessation available in a trial and biochemically‐validated abstinence data whenever available.

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified studies from the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register (until May 3, 2018), World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov (until July 30, 2018) using the MeSH term 'hotlines' or free‐text terms telephone* OR phone* OR quitline* OR helpline. See Appendix 1 for the full search strategy. At the time of the search the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 1, 2018; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20180404; Embase (via OVID) to week 201814; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20180212. See the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group website for full search strategies and a list of other resources searched.

Data collection and analysis

We identified trials where at least one of the arms included telephone contact. For this update, two review authors (WM and JMOM) extracted data from included studies, compared extraction and discussed disagreements with a third review author (JHB). We recorded the following information in the Characteristics of included studies tables:

The country and setting of the trial

The method of recruitment to the study

The method of randomisation and allocation concealment

Details of participants, including whether they were selected according to motivation to quit, and their age, gender and average baseline cigarette consumption

Description of intervention and control, including the schedule of telephone contacts

Definition of smoking abstinence used for the primary outcome, including timing of longest follow‐up and whether quit status was based on recent behaviour (point prevalence abstinence, e.g. in the past seven days) or on abstinence for an extended period since a quit date or a previous follow‐up (continuous or sustained abstinence)

Description of method of any biochemical validation or other method used to confirm self‐reported quitting

Description of numbers lost to follow‐up by treatment condition

In the Characteristics of excluded studies tables, we describe key trials that did not meet all inclusion criteria.

Assessment of risk of bias

We assessed each included study for risks of bias in the following domains: random sequence generation (allocation bias), allocation concealment (allocation bias), blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias), and incomplete outcome data (attrition bias). Following standard Cochrane guidance, we rated items in the 'Risk of bias' tables as being at low, unclear, or high risk of bias.

We judged studies to be at low risk of bias for sequence generation if an acceptable method for generating a randomisation sequence was described, at unclear risk if the study was described as 'random' but with no further information, and at high risk if it did not use a true randomisation method, e.g. alternation by calendar week. We judged the quality of the allocation concealment to be at low risk if the group to which a participant was to be allocated remained unknown to investigators and participant until enrolment was complete. We did not assess studies for performance bias, because blinding of participants and study personnel is not possible due to the nature of the intervention. We rated the quality of the blinding of outcome assessment at low risk if a biochemical verification of abstinence was carried out in the entire study population or in a random subsample, or if smoking status was measured by self‐report but the intervention and control arms received similar amounts of person‐to‐person contact, and at high risk otherwise. We judged attrition bias to be at low risk if the percentage of loss to follow‐up was less than 50% and if the difference between arms in percentage loss to follow‐up was less than 20%.

Choice of outcome and treatment of missing data

The primary outcome was the number of quitters at the longest follow‐up, using the strictest measure of abstinence reported. We preferred sustained and biochemically‐validated abstinence to point prevalence or to self‐reported quitting. If a less strict definition of quitting seemed more appropriate for showing an effect of the intervention on recovery from lapses or relapses, we planned a sensitivity analysis.

Where possible and appropriate, we used as denominators the number randomised to each condition, with losses to follow‐up assumed to be continuing smokers. We noted any exceptions in the 'Risk of bias' table for a study. Population‐based studies typically have relatively high loss to follow‐up, because of change of address or disconnected telephones. Non‐response might be independent of both treatment condition and smoking status, although possibly associated with other variables such as age or socioeconomic status. Dropout might be related to smoking status but not to treatment condition. Imputing as smoking all those missing, irrespective of, for example, whether they could not be contacted, or declined to respond, may not be appropriate. For individual studies it is possible to use analysis methods such as generalised estimating equations (GEE) for imputing missing data (Hall 2001). We noted whether studies that explored alternative assumptions about missing data reported any impact on the conclusions. When proportions lost are similar across conditions, and trial arms are balanced, the choice of denominator does not alter the relative effect, although the percentage quit and the absolute difference between conditions will be conservative.

Data synthesis

We summarised individual study results as a risk ratio (RR), calculated as: (number of quitters in intervention group/number randomised to intervention group)/(number of quitters in control group/number randomised to control group). Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis using a Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects model to estimate a pooled risk ratio with a 95% confidence interval (CI). When trials had more than one arm with a less intensive intervention we used only the most similar intervention without a telephone component as the control group in the primary analysis. We considered pooling of study results if both the intervention and control arms were sufficiently similar across trials. We assessed statistical heterogeneity between trials using the I2 statistic which describes the percentage of total variation between studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2003). We used threshold values of 50% and 70% as suggesting moderate and substantial heterogeneity respectively.

Investigations of heterogeneity: meta‐regression and subgroup analyses

We ran a meta‐regression in R version 3.5.0 (R 2018) using the meta and metafor packages (Schwarzer 2007; Viechtbauer 2010) to test the moderation of the effect of telephone counselling on smoking cessation by telephone counselling intensity (continuous: defined as maximum number of calls offered as part of the telephone counselling intervention), trial selection of participants that were motivated to quit (binary: yes/no), and type of baseline support offered in both the intervention and control arms (categorical: print‐based self‐help, brief face‐to‐face counselling, pharmacotherapy, or financial incentives). In meta‐regression, the effect size was summarised using the trial‐specific (natural) logarithm of the RR with its standard errors as weights. We fitted these trial characteristics separately in univariate models, and also together in a multivariate model to adjust for each moderator simultaneously.

We did not combine proactive and reactive approaches to counselling, so studies that provided access to a telephone helpline but did not call participants form a separate category. In earlier versions of this review we noted heterogeneity between studies of proactive telephone counselling, which was not explained by using subgroups based on the amount of support given for the control group. Lichtenstein 2002a has suggested that studies recruiting smokers who call quitlines should be considered separately. These studies share the characteristics that participants were actively seeking support at the time of their call, and that telephone counselling was the primary intervention. We therefore distinguish between trials in quitline callers and trials in smokers not calling a quitline.

We expected differences between the relative effect of telephone support, depending on whether it was being tested as the main intervention to aid cessation, or as an extra part of a multicomponent cessation programme. We therefore conducted a priori defined subgroup analysis to distinguish those studies in which telephone counselling was the most intensive component of a minimal contact intervention (print‐based self‐help was provided), from studies in which telephone counselling was assessed as an adjunct to a brief face‐to‐face counselling, or to pharmacotherapy. Where results of studies differed within the broad groupings described above we considered the following possible explanations: the difference between the intensity of the counselling based on the number of calls (two sessions or fewer, three to six sessions, and seven sessions or more), the counselling strategy used, and the characteristics of the participants, in particular their motivation to quit or stage of change at baseline.

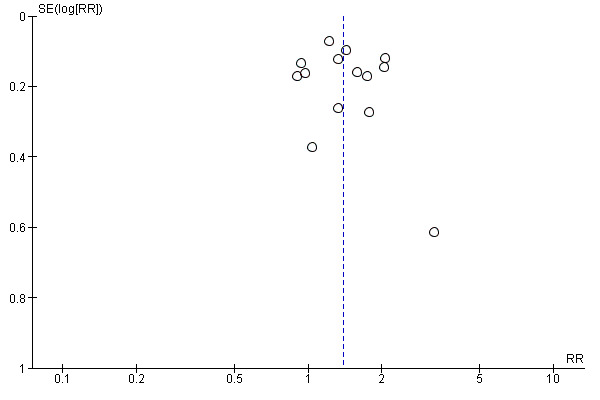

'Summary of findings' table

Following standard Cochrane methodology, we created 'Summary of findings' tables for the two main subgroups of participants, i.e. callers to a quitline and those not calling a quitline. Both 'Summary of findings' tables include data for the same primary outcome of long‐term smoking cessation. Also following standard Cochrane methodology, we used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome, and to draw conclusions about the certainty of evidence within the text of the review.

Results

Description of studies

One hundred and four studies met the criteria for inclusion in the review, with a total of 111,653 participants, and a median trial size of 735. Only seven studies had fewer than 100 participants (Brown 1992; Cossette 2011; Duffy 2006; Ebbert 2007; McClure 2011; Osinubi 2003; Vander Weg 2016), whilst seven studies, all involving callers to quitlines, had more than 3000 (Hollis 2007; Joyce 2008; Rabius 2004; Rabius 2007; Sherman 2017; Zhu 1996; Zhu 2002).

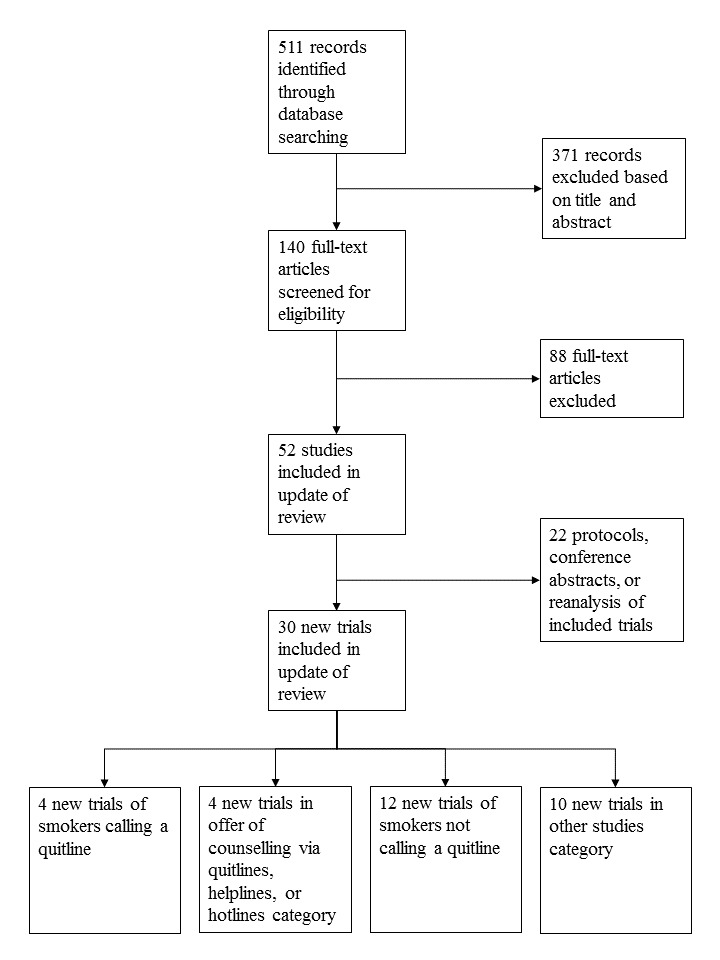

The most recent search resulted in 511 studies to screen (Figure 1). After title, and abstract, and then full‐text screening, we found 30 new studies to include in this update, plus 15 new ongoing studies.

1.

Study flow diagram for most recent update

Most trials were conducted in North America (72). Nine were in Australia (Borland 2001; Borland 2003; Borland 2008; Brown 1992; Girgis 2011; MacLeod 2003; Tzelepis 2011a; Young 2008; Zwar 2015), six in Canada (Chouinard 2005; Cossette 2011; Reid 1999a; Reid 2007; Reid 2018; Smith 2004), three in Spain (Miguez 2002; Miguez 2008; Ramon 2013), three in the UK (Aveyard 2003; Gilbert 2006; Ferguson 2012), two in Hong Kong (Abdullah 2005; Chan 2015), two in Germany (Flöter 2009; Metz 2007), two in Sweden (Lindqvist 2013; Nohlert 2014), one in Norway (Hanssen 2009), one in Malaysia (Blebil 2014), one in the Netherlands (Schuck 2014), one in Denmark (Skov‐Ettrup 2016), and one in China (Wu 2017). Participants were predominantly older adults with an average age typically in the 40s. One study recruited teenagers (Lipkus 2004), one high school students (Peterson 2016), one young people aged 18 to 24 (Sims 2013), and three recruited older people, aged over 50 (Rimer 1994), over 60 (Ossip‐Klein 1997), or over 65 (Joyce 2008). Four recruited pregnant women (Cummins 2016b; McBride 1999b; McBride 2004; Stotts 2002) and a further five recruited only women (McBride 1999a; McClure 2005; Flöter 2009; Solomon 2000; Solomon 2005). Four predominantly recruited men (Abdullah 2005; An 2006; Osinubi 2003; Sorensen 2007a). One was culturally tailored for Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese smokers (Zhu 2012) and one recruited Arabic smokers in Australia (Girgis 2011).

Most of the studies were trials of proactive calls from a counsellor, or from an automated interactive voice response system (IVR) (Reid 2007 IVR with counsellor follow‐up in case of need, Velicer 2006 IVR only). Only five assessed interventions that did not involve a counsellor contacting a participant (McFall 1993; Orleans 1998; Ossip‐Klein 1991; Sood 2009; Thompson 1993). Sixteen studies recruited participants who had phoned a quitline, but evaluated the addition of further proactive contacts (Borland 2001; Borland 2003; Bricker 2014; Cummins 2016b; Ferguson 2012; Gilbert 2006; Hollis 2007; Lindqvist 2013; Nohlert 2014; Rabius 2004; Rabius 2007; Sims 2013; Smith 2004; Zhu 1996; Zhu 2002; Zhu 2012). One study recruited proactively to quitline counselling (Tzelepis 2011a). Sixteen studies recruited participants in healthcare settings and referred them to services provided by quitlines, involving proactive counselling for those following through referral (Bastian 2012; Blebil 2014; Borland 2008; Brunette 2017; Collins 2018; Cummins 2016a; Duffy 2006; Ebbert 2007; Piper 2016; Ramon 2013; Rogers 2016; Schlam 2016; Sherman 2017; Warner 2016; Wu 2017; Zwar 2015). Ellerbeck 2009 repeatedly mailed primary care patients an offer of free pharmacotherapy and tested two levels of disease management, including proactive calls or no contact. One study offered either a proactive or reactive service as covered benefit (Joyce 2008). Additional details are in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

The number, duration and content of the telephone calls was variable. The potential number of calls ranged from one to 12 and in some studies was flexible. The duration of the calls also varied; 10 to 20 minutes was common, although the initial call might be longer. The call schedule could be spaced over weeks or months. Amongst studies that did not recruit participants on the basis of their willingness to make a quit attempt, the content was typically individualised to enhance motivation in those undecided about quitting, or to support a quit attempt where appropriate. Counselling was most commonly provided by professional counsellors or trained healthcare professionals. One trial used trained postgraduate students (Aveyard 2003). Three trials used trained peer counsellors, in one case survivors of childhood cancer (Emmons 2005), and in the other two women ex‐smokers (Solomon 2000; Solomon 2005).

Many trials reported both short‐term point prevalence abstinence (seven‐day or 24‐hour) and sustained abstinence, at one or more longer follow‐ups. Long‐term sustained abstinence was available for 53 of the 104 trials (51%). For the remainder, the outcome was based on point prevalence abstinence at the longest follow‐up. Length of longest follow‐up ranged from six months from start of intervention (35 trials), to seven years (Peterson 2016).

We grouped trials into three broad categories: trials of interventions for smokers who contacted a helpline; trials assessing the effect of providing access to a helpline; and trials that offered support proactively in other settings. Finally there are 10 trials that do not fit into any of these categories, so are considered individually (Bastian 2012; Collins 2018; Halpin 2006; Klemperer 2017; Reid 2018; Smith 2013; Sumner 2016; Vander Weg 2016; Warner 2016; Wu 2017).

Trials of interventions for people calling helplines

Nineteen trials recruited people who had phoned helplines/quitlines. We distinguished between trials where the intervention involved further proactive contact by the counsellor, and those that tested different interventions at the initial call. Fourteen studies tested proactive calls back to people who had initiated the contact with the quitline. The number of calls varied, with four studies comparing more than one schedule (Hollis 2007; Rabius 2007; Smith 2004; Zhu 1996). There were small differences in the support for the control group. In one trial, all participants had brief counselling during their initial call (Borland 2001); in three, some control group participants received some counselling (Borland 2003; Gilbert 2006; Zhu 2002). Ferguson 2012 was a factorial trial comparing proactive counselling to standard support, which included further contact by email, letter or text, and the offer of proactive calls. Participants were also randomised to an offer of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). In the others the control group received self‐help materials (Cummins 2016b; Hollis 2007; Nohlert 2014; Rabius 2004; Rabius 2007; Sims 2013; Smith 2004; Zhu 1996; Zhu 2012).

Five trials compared different interventions at the time a participant called the helpline. Sood 2009 compared counselling at the initial call to mailed self‐help materials only. Orleans 1998 and Thompson 1993 compared different counselling interventions provided during the initial call; Orleans 1998 compared counselling and materials targeted at African‐American smokers to standard advice and materials, and Thompson 1993 compared a counselling approach based on the 'stage of change' model to the provision of more general information. Two trials offered two different modalities of proactive telephone counselling. Bricker 2014 compared Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) counselling with Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), with both arms receiving a two‐week supply of NRT. Lindqvist 2013 compared Motivational Interviewing (MI) telephone counselling with standard telephone counselling.

Trials providing access to a helpline

Three studies assessed the impact of offering reactive counselling by providing access to a helpline/quitline/hotline, compared to not being provided access to a telephone helpline/quitline/hotline. One randomised counties to hotline access or not, and followed up smokers who were planning to stop and had registered for a smokers' self‐help project (Ossip‐Klein 1991). One compared a referral to a quitline to the usual care of a GP practice (Zwar 2015). One combined newsletter mailings and hotline access compared to no follow‐up support for smokers who had registered for a self‐help televised cessation programme (McFall 1993). Three studies compared referral to a quitline to proactive telephone counselling (Rogers 2016; Sherman 2017; Skov‐Ettrup 2016). Joyce 2008 compared four different levels of benefit for Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older. The most intensive intervention offered a choice of accessing either a reactive hotline or multisession proactive counselling, along with self‐help materials and coverage of nicotine patch with a small co‐payment. Other arms offered coverage of brief provider counselling with or without coverage of pharmacotherapy, and usual care.

Trials of proactive counselling, not initiated by calls to quitlines

There were 65 trials in this category that we judged to have sufficient features in common to consider pooling their results. There were some differences in the intensity of the telephone component, the amount of cessation support that was common to both the control and intervention groups, and the populations recruited.

Studies with minimal intervention controls

There were 33 studies in this subgroup. In 26 studies proactive telephone counselling calls were the only form of personal contact in the cessation intervention. The control groups generally received mailed self‐help materials, but Graham 2011 provided access to a cessation website. In six studies in healthcare settings the telephone intervention was an adjunct to usual care that involved at most a brief smoking intervention (Duffy 2006; Hanssen 2009; Holmes‐Rovner 2008; Rigotti 2006; Stotts 2002; Young 2008). In two further studies that recruited participants through healthcare systems, advice and support were part of usual care but not all participants had clinic visits; the telephone counselling was delivered independently of any clinic visit rather than being an adjunct to a specific episode of care (An 2006; Lipkus 1999). Pharmacotherapy was not systematically offered to all intervention participants in any of the above trials, but in two there was greater use of pharmacotherapy by intervention participants (An 2006; McClure 2005). An 2006 encouraged the use of NRT or bupropion for intervention group participants making a quit attempt and this increased their use, although pharmacotherapy was available to all participants as part of their usual care. In McClure 2005 all participants could enrol in the Free & Clear phone‐based support programme, which could also provide access to pharmacotherapy; this was used more by intervention than control groups.

Studies with brief intervention/counselling controls

Thirteen trials incorporated what we judged to be more substantial face‐to‐face advice for all participants, but without systematic use of pharmacotherapy (Borland 2008; Brown 1992; Brunette 2017; Chouinard 2005; Cossette 2011; Ebbert 2007; Flöter 2009; McBride 2004; Metz 2007; Ockene 1991; Osinubi 2003; Ramon 2013; Reid 2007). The support common to all participants included: a single information session and the provision of a self‐help manual (Brown 1992); usual prenatal care including provider advice and self‐help materials (McBride 2004); assessment, advice or brief counselling from a physician (relevant arms of Borland 2008; Ockene 1991; Ramon 2013) or hygienist/dentist (Ebbert 2007); advice from an occupational physician to consult a personal physician (Osinubi 2003); inpatient nurse counselling (Brunette 2017; Chouinard 2005; Cossette 2011; Reid 2007); or multisession group counselling (Flöter 2009; Metz 2007).

Studies of counselling added to pharmacotherapy

Eighteen trials provided telephone counselling as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy. In 15 trials there was a systematic offer or provision of NRT (Bastian 2013; Blebil 2014; Cummins 2016a; Fiore 2004; Fraser 2014; Hughes 2010; Lando 1997; MacLeod 2003; NCT00534404; Ockene 1991; Reid 1999a; Schlam 2016; Solomon 2000; Solomon 2005; Velicer 2006). Swan 2010 provided varenicline. Boyle 2007 recruited health maintenance organisation (HMO) members who were filling a prescription for any cessation medication, and Ellerbeck 2009 offered free medication four times over two years. The support common to all participants in other trials included: access to a website (Swan 2010); physician advice and an offer of free nicotine gum (relevant arms of Ockene 1991); provision of free nicotine patch after a primary care visit (Fiore 2004); three sessions of physician advice and free nicotine patch (Reid 1999a); a single 90‐minute session, a free prescription for nicotine patch and access to a helpline (Lando 1997); or provision of free nicotine patches (two‐week supply only) but no face‐to‐face contact (Bastian 2013; Blebil 2014; Fraser 2014; MacLeod 2003; Solomon 2000; Solomon 2005; Velicer 2006). Cummins 2016a provided up to six weeks of NRT with the number of weeks depending on how many cigarettes smoked per day , whereas NCT00534404 and Schlam 2016 provided up to eight weeks' free supply of NRT. Velicer 2006 provided nicotine patches to participants meeting criteria for readiness to make a quit attempt; 86% received some during the study.

Studies of counselling added to incentives

One study provided telephone counselling as an adjunct to incentives. Thomas 2016 compared the effect of adding telephone counselling as an adjunct to entry into a 'Quit and win' contest.

Telephone counselling intensity

The number of calls and the period over which they were delivered in this group of 65 studies was very varied. We provide a summary in the following table.

The average number of calls completed, where reported, was typically considerably smaller than the maximum available. For studies where the intervention involved a process of referral to proactive support from another source, the proportion of participants reaching and accepting counselling was small, but those accepting the intervention generally had multisession support.

Recruitment and motivation of participants

We tried to categorise this set of 65 trials according to whether or not they selected participants with an interest in stopping smoking, or whether they were non‐selective or designed to reach a wider population of smokers. Of the 25 trials in the ‘Selected’ subgroup, 13 recruited from the general population using advertisements for smokers planning to quit or interested in quitting (Brown 1992; Fraser 2014; Graham 2011; MacLeod 2003; Miguez 2002; Miguez 2008; NCT00534404; Orleans 1991; Ossip‐Klein 1997; Rimer 1994; Solomon 2000; Solomon 2005; Swan 2010). Seven recruited during healthcare visits (Blebil 2014; Brunette 2017; Cummins 2016a; Fiore 2004; Ramon 2013; Reid 1999a; Schlam 2016); Boyle 2007 and Lando 1997 recruited HMO members, and An 2006 mailed invitations to patients of Veterans Administration Medical Centres. Schuck 2014 recruited parents of children through their primary schools, and Thomas 2016 recruited higher education students.

There were 38 trials in which motivation or interest in quitting was not an explicit entry criterion. Many recruited people in healthcare settings and the level of motivation to quit as assessed by stage of change at baseline, or other measures, was often high. Four recruited pregnant women (McBride 1999b; McBride 2004; Rigotti 2006; Stotts 2002); 15 recruited people during healthcare visits including in family practices, dental practices and hospitals (Bastian 2013; Borland 2008; Chouinard 2005; Cossette 2011; Duffy 2006; Ebbert 2007; Flöter 2009; Girgis 2011; Hanssen 2009; Holmes‐Rovner 2008; Metz 2007; Ockene 1991; Osinubi 2003; Reid 2007; Young 2008); seven others recruited through healthcare system records (Aveyard 2003; Ellerbeck 2009; Lipkus 1999; McClure 2005; McClure 2011; Prochaska 2001; Velicer 2006). Of the other miscellaneous methods, Lichtenstein 2000 and Lichtenstein 2008 recruited smokers in households that were offered free radon testing kits, Lipkus 2004 recruited teens approached in shopping malls, Chan 2015 recruited adults approached in shopping malls, Peterson 2016 recruited students from high schools, Abdullah 2005 recruited smoking parents of children in a birth cohort study, Emmons 2005 recruited smokers from a cohort study of childhood cancer survivors, and Sorensen 2007a recruited union members. Prochaska 1993 advertised for community volunteers, irrespective of quitting interest. In three trials contact was initiated with smokers who had not been specifically recruited to a trial (Curry 1995; Lando 1992; McBride 1999a).

Studies comparing intense versus minimal telephone counselling

Three studies did not have a no‐telephone support control and compared interventions with different numbers of calls (Miller 1997; Piper 2016; Swan 2003). Miller 1997 assessed the effect of increasing the amount of telephone follow‐up after an inpatient counselling intervention. Piper 2016 compared three 15‐minute phone sessions within a 10‐day period versus a single 10‐minute session on the quit date in a factorial design. Swan 2003 compared two intensities of behavioural support, both of which involved telephone contact without face‐to‐face support, for smokers also randomised to one of two doses of bupropion.

Other studies

We identified 10 other studies where we judged the nature of the main intervention or the conditions compared to be so distinctively different from any other included studies that we describe them separately rather than pooling them.

Bastian 2012 compared standard telephone counselling with family‐supported telephone counselling, which included a support skills booklet and additional telephone counselling content focusing on social support skills that aimed to help increase positive interactions between the participant and their designated support person, to facilitate smoking cessation. Participants randomised to family support‐based intervention also received an eight‐page disease‐specific family support booklet.

Collins 2018 compared an individual behavioural telephone counselling intervention that focused on reducing child second‐hand smoke exposure and parent smoking cessation, to an individual telephone health education attention control intervention that focused on improving family nutrition on a budget.

Halpin 2006 compared different benefit designs for tobacco treatment. The control group was given coverage for pharmacotherapy only. One intervention group had coverage for telephone counselling and pharmacotherapy (bupropion or NRT, USD 15 co‐payment) whilst the other had pharmacotherapy coverage only if enrolled for telephone counselling. Participants were not required to take up any treatment during the study period.

Klemperer 2017 compared three different arms of telephone counselling: smoking reduction telephone counselling, brief motivational telephone counselling, and a usual care five‐minute call.

Reid 2018 included an automated telephone follow‐up system that posed a series of questions to participants about their smoking status, confidence in staying smoke‐free, use of smoking cessation aids (medication and behavioural support), and need for assistance. This flagged eligible participants for contact by a nurse‐counsellor, who provided additional assistance as appropriate. The effect of this intervention was compared to standard care.

Smith 2013 tested the addition of a medication adherence counselling component to standard four‐session counselling in a factorial trial that also compared two durations of free NRT and a combination of patch and gum versus patch alone.

Sumner 2016 tested different approaches to telephone counselling, comparing nondirective with directive telephone coaching. In nondirective counselling, the quitline coach allowed the participant to set the agenda for each call, whereas in directive counselling the quitline coach followed a prespecified agenda for each call, and did not allow the participant to deviate from the agenda.

Vander Weg 2016 compared tailored telephone counselling, which combined counselling on tobacco use and related issues including depressive symptoms, risky alcohol use, and weight concern, with referral to a state tobacco quitline. Both arms received an offer of NRT, bupropion or varenicline.

Warner 2016 compared the effects of a brief (approximately five‐minute) quitline facilitation intervention with brief (approximately five‐minute) cessation advice. Both arms received a free two‐week supply of nicotine patches.

Wu 2017 compared smoking‐reduction telephone counselling consisting of a minimal face‐to‐face individual smoking reduction intervention lasting for about one minute, and five follow‐up interventions lasting for about one minute each, with brief face‐to‐face individual exercise and dietetic advice lasting for the same intervention time as the smoking reduction intervention, and five follow‐up interventions lasting for about one minute each with different intervention contents.

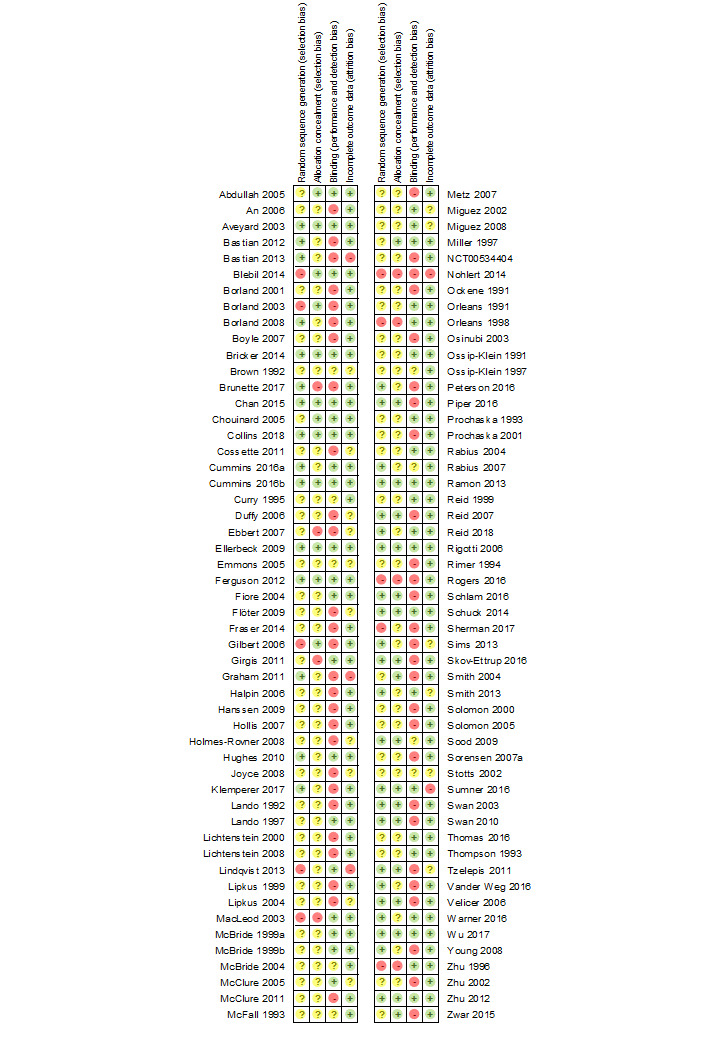

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of the evaluation of risks of bias for each study is shown in Figure 2. Overall, we judged 12 studies (11.5%) to be at low risk of bias across all domains, 60 (57.7%) to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain, and the remaining 32 (30.8%) to be at unclear risk of bias. Full details for 'Risk of bias' judgements for all included studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

We judged 13 studies to be at high risk of selection bias because of the way the sequence was generated or concealed; we rated 21 at low risk of selection bias, and the remainder to be at unclear risk.

All included studies described treatment allocation as 'random', but most did not give sufficient details about the method for generating the sequence. Thirty‐eight (36%) gave sufficient detail to be judged at low risk for sequence generation. We judged 10 (10%) to be at high risk of bias for sequence generation (Borland 2003; Blebil 2014; Gilbert 2006; Lindqvist 2013; MacLeod 2003; Nohlert 2014; Orleans 1998; Rogers 2016; Sherman 2017; Zhu 1996). We judged the remaining studies to be at unclear risk of bias.

Twelve trials used cluster randomisation, nine of which contributed to a meta‐analysis. In two of these, households were the unit of randomisation, and about 54% of households contained more than one smoker (Lichtenstein 2000; Lichtenstein 2008). The reported intraclass correlation was small. Borland 2008 randomised general practitioners. The reported odds ratio that adjusted for clustering and other factors was similar to that generated by the crude data. Lando 1997 randomised by the orientation session attended. Chouinard 2005 randomised clusters of two to six participants. Ebbert 2007 randomised by dental practice, and Zwar 2015 randomised by general practice. Peterson 2016 randomised by high school and Lindqvist 2013 by quitline counsellor. Excluding these studies did not have a major effect on any of the meta‐analysis findings.

We did not pool the other three cluster‐randomised trials with other studies in a meta‐analysis. In one, participants were given access to a hotline according to county of residence, so that the availability of a hotline could be advertised in the intervention counties (Ossip‐Klein 1991). Joyce 2008 randomised areas within states to different Medicare benefits. Sumner 2016 randomised families to either directive or nondirective telephone coaching.

Methods for concealing the allocation were also incompletely reported in most studies. Thirty (29%) reported sufficient detail to be judged at low risk. We judged eight (8%) to be at high risk of bias due to lack of concealment (Brunette 2017; Ebbert 2007; Girgis 2011; MacLeod 2003; Nohlert 2014; Orleans 1998; Rogers 2016; Zhu 1996). .

Blinding of outcome measurement (detection bias)

Overall, we judged most studies to be at high risk of detection bias (54 studies, 51.9%), while 41 studies (39.4%) were at low risk of detection bias. We rated the remaining nine studies (8.7%) at unclear risk of detection bias.

As set out in the Methods, we assessed detection bias based on whether abstinence was biochemically validated. If abstinence was not validated, we considered whether the intervention group received substantially more contact than the control group, in which case we suspected that differential misreport was possible.

The studies in quitline callers typically did not attempt to use biochemical verification of self‐reported quitting. Two tested a local convenience sample (Rabius 2004; Zhu 1996). Ferguson 2012 reported carbon monoxide‐ (CO) validated rates, although only 52% of self‐reported quitters provided samples. Studies in other settings were more likely to require biochemical verification of all self‐reported abstinence. Aveyard 2003, Collins 2018, Cummins 2016a, Cummins 2016b, Lando 1992 and Ossip‐Klein 1991 measured cotinine levels. Blebil 2014, Fiore 2004, Hughes 2010, Lando 1997, Miguez 2002, Ramon 2013, Reid 2018, Rigotti 2006, and Wu 2017 measured CO levels. Brunette 2017, Chan 2015, Chouinard 2005, and Schuck 2014 used a mixture of CO and cotinine assessments. Ellerbeck 2009 and Miller 1997 tested for cotinine but allowed family‐member verification of some self‐reports. Warner 2016 measured urine anabasine levels. Thomas 2016 used NicCheck test strips. Some other studies attempted biochemical verification but did not report validated abstinence (Bastian 2012; Bastian 2013; Brown 1992; Curry 1995; Lipkus 2004; McBride 1999a; McBride 1999b; McBride 2004; McClure 2005; Orleans 1991; Reid 1999a; Solomon 2000; Sumner 2016; Thompson 1993). Stotts 2002 validated abstinence at an early follow‐up but not at the follow‐up used in this review.

One trial in teenagers reported particularly high misreport rates (45% to 55%) in both groups; some admitted smoking in the seven days before returning the sample (Lipkus 2004).

Incomplete outcome data

All studies reported the numbers randomised to each group. We judged five studies (4.8%) to be at high risk of attrition bias (Bastian 2013; Graham 2011; Lindqvist 2013; Nohlert 2014; Sumner 2016), due to the large proportion of participants lost to follow‐up, while 16 were at unclear risk of attrition bias as the number followed up was not provided (Brown 1992; Cossette 2011; Duffy 2006; Ebbert 2007; Emmons 2005; Flöter 2009; Holmes‐Rovner 2008; Joyce 2008; Lipkus 2004; McClure 2005; Miguez 2002; Miguez 2008; Sims 2013; Smith 2004; Stotts 2002; Tzelepis 2011a). We rated most studies (83 studies, 79.8%) at low risk of attrition bias.

Most studies reported findings based on treating all dropouts as smokers, although some did not note the number lost to follow‐up who were assumed to be continuing smokers. Many also reported complete‐case analyses (excluding dropouts), or used methods for imputing missing data. In most cases this had little impact on the relative effect, because numbers lost were similar across conditions. We did not identify any studies where using complete cases or using adjusted estimates of quit rates would have changed the relative effect enough to alter the conclusions of a meta‐analysis.

We detected no other biases.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Interventions for callers to quitlines ‐ effect of additional proactive calls for smoking cessation.

| Interventions for callers to quitlines ‐ effect of additional proactive calls for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: callers to quitlines Intervention: additional proactive calls | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Additional proactive calls | |||||

| Smoking cessation Self‐reported abstinence (majority) Follow‐up: 6+ months | Study population | RR 1.38 (1.19 to 1.61) | 32,484 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb,c | ‐ | |

| 72 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (85 to 116) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 50 per 1000a |

69 per 1000 (59 to 81) |

|||||

| High | ||||||

| 150 per 1000a |

208 per 1000 (178 to 242) |

|||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aLow control rate reflects lower end of range evident in trials; 4/14 had control rates < 50 per 1000. High control rate likely to be applicable for smokers also using pharmacotherapy. bEffect estimate not sensitive to exclusion of studies judged at high risk of bias, so not downgraded on this basis. cDowngraded by one level due to unexplained statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 72%).

Summary of findings 2. Interventions for smokers not calling quitlines ‐ effect of proactive telephone counselling.

| Proactive telephone counselling for smokers not calling quitlines | ||||||

| Patient or population: smokers not calling quitlines Intervention: proactive telephone counselling | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Proactive telephone counselling | |||||

| Smoking cessation Self‐reported abstinence (majority) Follow‐up: 6+ months | Study population | RR 1.25 (1.15 to 1.35) | 41,233 (65 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea,b | ||

| 110 per 1000a | 137 per 1000 (127 to 149) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aBased on crude average of events/total, with participants lost to follow‐up assumed to be smoking. Interquartile range in trials 63 ‐ 200 per 1000. Higher baseline cessation rates typical amongst motivated populations receiving pharmacotherapy and some support. Relative additional benefit of telephone intervention may be smaller in this setting. bEffect estimate not sensitive to exclusion of studies judged at high risk of bias, so not downgraded on this basis. cDowngraded by one level due to statistical heterogeneity, which was only partially explained by differences in baseline support. In subgroup analyses, evidence of effect was clearer when telephone counselling was offered as an adjunct to print‐based self‐help, or brief face‐to‐face counselling. Effect smaller and less certain when telephone counselling was offered as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy. However, statistical heterogeneity ranged from small to substantial within the subgroups.

Trials of interventions for people calling helplines

Effect of additional proactive support

Fourteen studies (N = 32,484) that compared an intervention involving multisession proactive counselling with a control condition providing self‐help materials or brief counselling at a single call showed evidence of a benefit from the additional support. With the addition of two new studies published since the last update (Cummins 2016b; Nohlert 2014), the pooled risk ratio (RR) was unchanged but the confidence interval is now wider, given the substantial heterogeneity in the effect size between studies and the random‐effects model now being used: RR 1.38, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.19 to 1.61; I2 = 72%; Figure 3, Analysis 1.1). Exclusion of eight studies that were at high risk of bias for any of the domains (Borland 2001; Borland 2003; Gilbert 2006; Hollis 2007; Nohlert 2014; Smith 2004; Zhu 1996; Zhu 2002) resulted in a slightly larger effect size, but the confidence intervals overlapped (RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.98; 6 trials, 16,293 participants; I2 = 80%).

3.

Comparison 1. Interventions for callers to quitlines. Effect of additional proactive calls.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interventions for callers to quitlines ‐ effect of additional proactive calls, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

The two studies with the largest weights in the meta‐analysis detected statistically significant effects, as did six other studies, suggesting that there is a benefit from these types of interventions in most settings but perhaps not in all. We examined the characteristics of the six studies in which the point estimates suggested no effect of counselling (Borland 2003; Ferguson 2012; Gilbert 2006; Nohlert 2014; Sims 2013; Smith 2004). These studies were conducted mainly in the USA (n = 8), but also in the UK (n = 2), Australia (n = 2), Sweden (n = 1), and Canada (n = 1). In the earliest UK trial (Gilbert 2006), the authors thought that the unstructured counselling might have explained the lack of effect, but in the second trial (Ferguson 2012) a more structured protocol was used. In both cases the control groups would have received some support at the original call, as well as mailed or emailed materials. The context of the UK healthcare system may contribute to the difference, since there has historically been a well‐developed Stop Smoking Service with access to support and medication. Ferguson 2012 also failed to detect an effect of offering free nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), in a factorial design. The difference in the healthcare setting may also explain the lack of effect for the Australian (Borland 2003), Swedish (Nohlert 2014) and Canadian (Smith 2004) studies. In addition, in the Australian study (Borland 2003), the group in the control arm received an intensive tailored self‐help programme, the efficacy of which may be more similar to that of a proactive telephone counselling programme. In the Swedish study (Nohlert 2014), most of the bias domains were at high risk, which could have obscured an effect of the proactive telephone counselling. In the only American study with a point estimate suggesting no effect (Sims 2013), the participants were young adults, for whom there is limited evidence for any effective interventions (Fanshawe 2017). However, the confidence interval for this study was wide and encompassed the possibility of effects consistent with the other studies.

Using only the Hollis 2007 trial data for intervention and control arms that were not offered NRT as an adjunct slightly decreased the effect size (RR 1.36, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.62; 31,048 participants), while using the data for the arms that had NRT as an adjunct therapy increased the effect size (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.64; 31,046 participants). This is because the addition of NRT enhanced the effect of the combined telephone counselling arms, despite the study reporting no evidence of interaction.

Counselling intensity

In the main analysis we pooled more than one intensity of intervention into the treatment arms of four studies (Hollis 2007; Rabius 2007; Smith 2004; Zhu 1996). Using only the more intensive interventions in the two trials that reported outcomes for two different interventions (Hollis 2007; Zhu 1996) marginally increased the pooled effect size (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.64; 29,908 participants; I2 = 72%; ). Smith 2004 did not detect a difference between groups receiving two or six follow‐up calls after an initial 50‐minute session, and we were unable to obtain separate results for different telephone counselling intensities. Rabius 2007 tested six different intervention formats, varying the number of calls, their duration and the use of two brief booster calls at four and eight weeks after counselling. There was no clear dose‐response effect: five brief counselling calls plus boosters were no less effective than the standard American Cancer Society protocol of five longer calls and boosters.

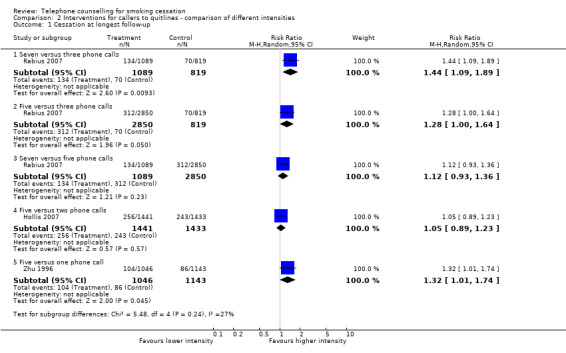

Analysis 2.1 includes comparisons of different telephone counselling intensities across studies. In Rabius 2007, a higher number of calls was associated with higher cessation rates. Seven calls, including five brief or standard calls with two booster calls (RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.89; 1,908 participants), and five calls, including brief or standard calls with or without booster calls (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.64; 3669 participants) were more effective in increasing cessation rates than the three standard calls without booster calls. However in the same study, seven calls were no more effective than five calls in increasing cessation rates (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.36; 3939 participants). In Hollis 2007, intensive counselling (five calls) was not more effective than moderate counselling (two calls) (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.23; 2874 participants). Lastly, in Zhu 1996 multiple counselling (five calls) was more effective than a single counselling session (RR 1.32, 1.01 to 1.74; 2189 participants).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Interventions for callers to quitlines ‐ comparison of different intensities, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

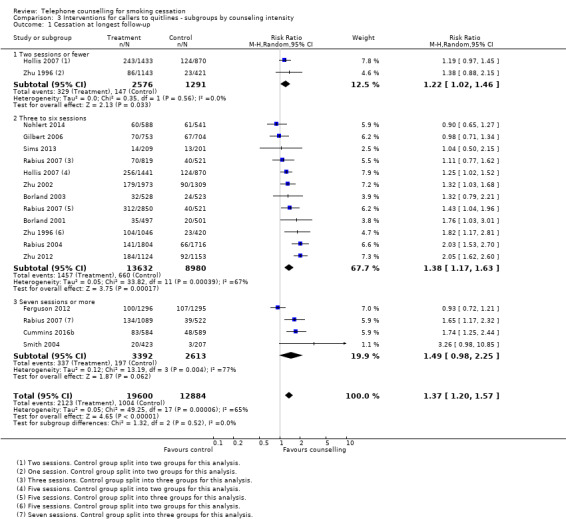

In a post hoc subgroup analysis by telephone counselling intensity (Analysis 3.1), there were no statistically significant subgroup differences (Chi2 = 1.32, df = 2 (P = 0.52), I2 = 0%). Subgroups of low and medium intensity detected a statistically significant benefit of the intervention (two sessions or fewer: RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.46; 2 trials, 3867 participants; I2 = 0%; three to six sessions: RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.63; 11 trials, 22,612 participants; I2 = 67%); the difference was not statistically significant for seven or more sessions, but the confidence interval was wide and narrowly missed one (RR 1.49, 95% CI 0.98 to 2.25; 4 trials, 6005 participants; I2 = 77%).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Interventions for callers to quitlines ‐ subgroups by counseling intensity, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

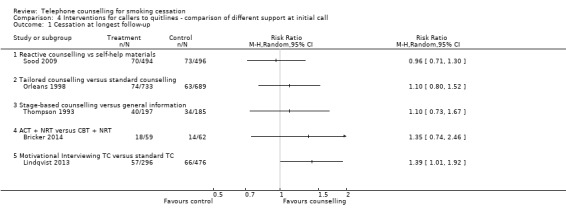

Comparisons between different types of support at initial call

Five studies compared different modalities of telephone counselling with varying support at initial call (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Interventions for callers to quitlines ‐ comparison of different support at initial call, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

One study (Sood 2009) compared reactive counselling to mailed self‐help materials alone. All participants in the intervention group had counselling at the time of their call and had the option to get repeated support. We found no effect of the intervention (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.30; 990 participants).

Two studies compared different reactive support for helpline callers during a single session. They did not detect a significantly increased benefit from either counselling and materials designed for African‐Americans (Orleans 1998) (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.52; 1422 participants), or stage‐based counselling designed for blue‐collar workers (Thompson 1993) (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.67; 382 participants) compared to standard support. Quit rates in these trials were from 15% to 20% for point prevalence rates at six months.

In this latest update we found two new trials that compared telephone counselling interventions using different behavioural change theories. Bricker 2014 compared acceptance and commitment therapy to cognitive behavioural therapy, but observed no difference between the two (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.74 to 2.46; 121 participants). Lindqvist 2013 found that motivational interviewing may be more effective than standard telephone counselling (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.92; 772 participants).

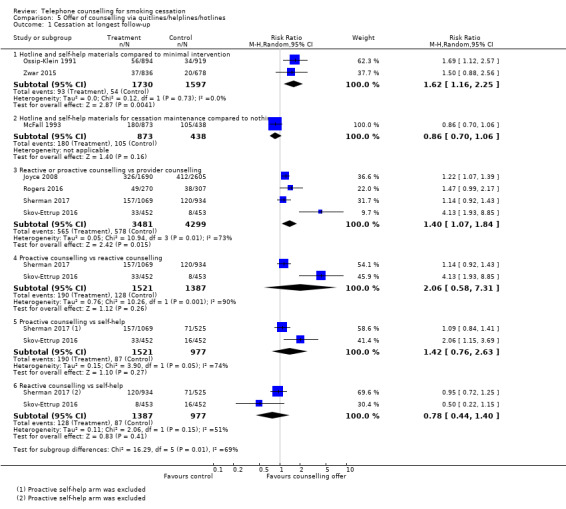

Trials providing access to a helpline

Two studies (Ossip‐Klein 1991; Zwar 2015) compared the provision of a hotline versus a minimal intervention. When we combined them, we noted a substantial increase in quit rates (RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.16 to 2.25; 3327 participants; I2 = 0%; Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Offer of counselling via quitlines/helplines/hotlines, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

In McFall 1993 smokers who had enrolled to be sent materials for a self‐help programme with a televised component were randomised to receive follow‐up newsletters and access to a helpline for six months. The intervention combined a helpline and written materials, but quit rates were not lower in the intervention than in the control condition after 24 months (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.06; 1311 participants).

In another four trials (Joyce 2008; Rogers 2016; Sherman 2017; Skov‐Ettrup 2016), reactive or proactive calls were compared with provider counselling (quitline service), demonstrating a moderate increase in cessation rates for reactive or proactive counselling (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.84; 7780 participants; I2 = 73%) compared with provider counselling. The four trials were very heterogeneous in terms of target populations and interventions provided: in Joyce 2008 enrollees for a Medicare Stop Smoking Programme were randomised to a quitline that offered the choice of a reactive hotline with prerecorded messages and ad hoc counselling, or a proactive service, in addition to insurance coverage for the nicotine patch. The control group received pharmacotherapy coverage only. In Rogers 2016, people with mental health conditions were randomised to proactive telephone counselling for mental health patients or counselling provided by the state quitline. In Sherman 2017 smokers attending the Department of Vereran Affairs outpatient primary care clinics were recruited, and in Skov‐Ettrup 2016 the participants were a nationally representative sample of the Danish population. In both studies the participants were randomised to either proactive or reactive telephone counselling, or to self‐help. The cessation rates were much larger in the three trials in which the participants had been offered pharmacotherapy (Joyce 2008;Rogers 2016; Sherman 2017). Also in these three trials, point prevalence abstinence was reported, compared to Skov‐Ettrup 2016 which reported prolonged abstinence at 12 months.

Two studies identified for this latest update (Sherman 2017; Skov‐Ettrup 2016) provided data for comparisons of proactive and reactive telephone counselling versus each other, and versus self‐help. Proactive counselling was not associated with an improvement in cessation rates compared with reactive counselling (RR 2.06, 95% CI: 0.58 to 7.31; 2908 participants; I2 = 90%). However, neither proactive (RR 1.42, 95% 0.76 to 2.63; 2498 participants; I2 = 74%) nor reactive (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.40; 2364 participants; I2 = 51%) were significantly associated with increased cessation rates when compared with self‐help.

Trials of proactive counselling, not initiated by calls to quitlines

Overall effect of counselling

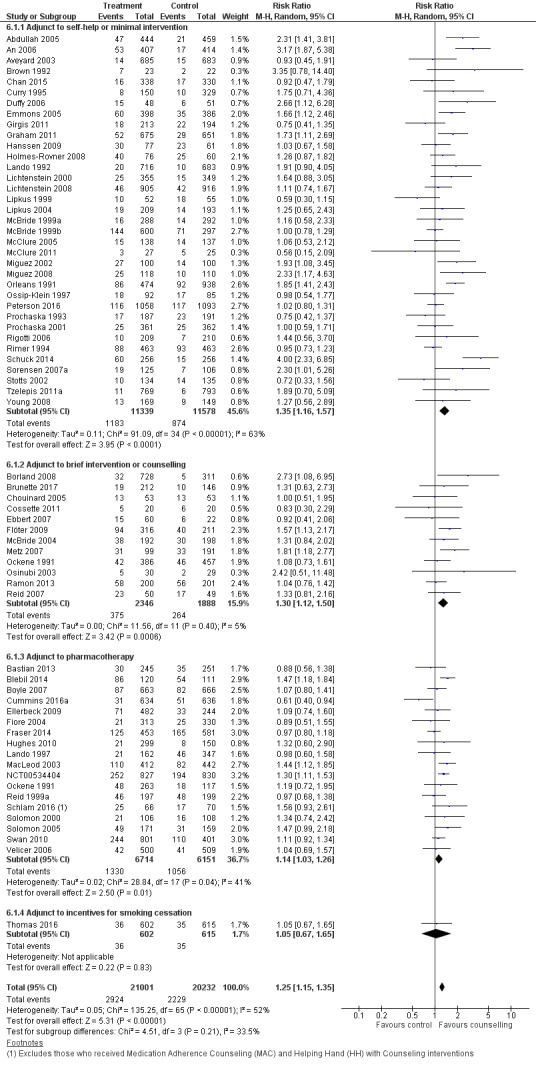

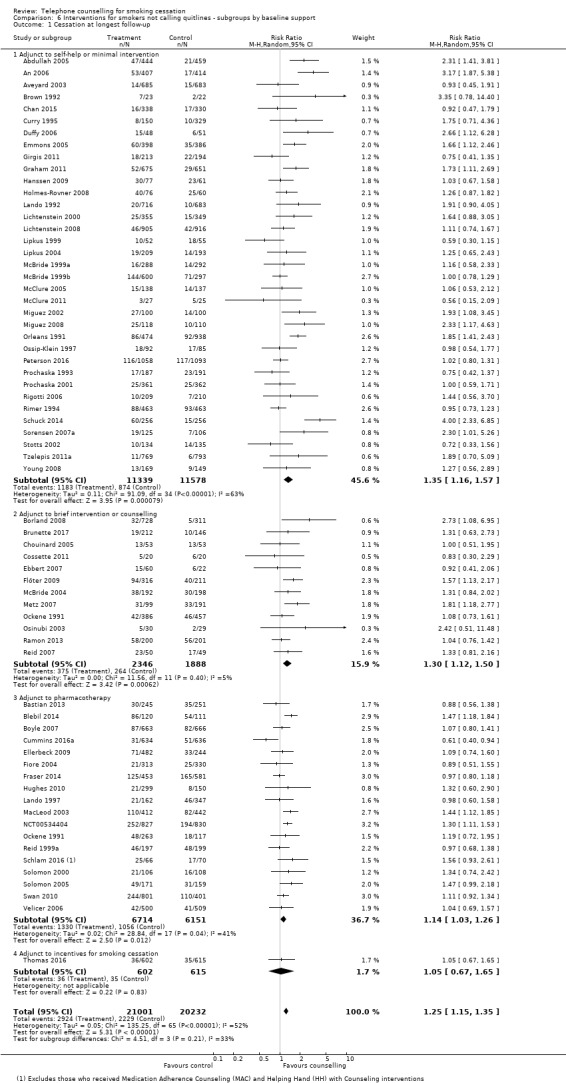

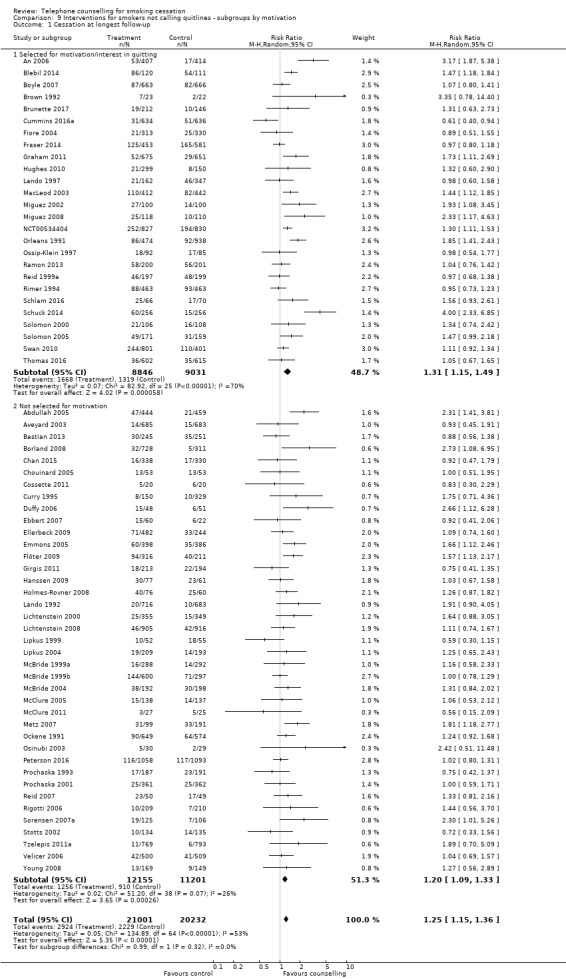

There were 65 trials in this comparison (Ockene 1991 contributed different data to two subgroups, making a total of 66 estimates in the analysis). The pooled effect suggested a modest benefit of proactive telephone counselling: RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.35; 41,233 participants; I2 = 52% (Figure 4, Analysis 6.1). Our prespecified subgroup analyses based on the baseline support provided to both intervention and control, counselling intensity, or motivation did not fully explain the heterogeneity, nor was heterogeneity reduced by excluding the trials amongst teenagers or pregnant women. Exclusion of 38 trials that were at high risk of bias in at least one of the domains did not have a large influence on the pooled effect size, but widened the confidence interval (RR 1.23, 1.05 to 1.45; 26 trials, 15,701 participants; I2 = 62%).

4.

Comparison 6. Interventions for smokers not calling quitlines ‐ subgroups by baseline support.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Interventions for smokers not calling quitlines ‐ subgroups by baseline support, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

Baseline support offered

Thirty‐five trials tested the effect of telephone counselling as an adjunct to self‐help or to a minimal intervention. In this subgroup the effect of telephone counselling was slightly stronger: RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.57; 22,917 participants, than that for all 65 trials, although the heterogeneity was more pronounced within this subgroup (I2 = 63%).

Twelve trials tested the effect of telephone counselling as an adjunct to face‐to‐face counselling or to a brief intervention. In this subgroup the effect of telephone counselling was also slightly stronger: RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.50; 4234 participants, than that for all 65 trials but with less evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 5%).

Eighteen trials tested the effect of telephone counselling as an adjunct to the systematic use or offer of NRT (patch or gum), bupropion, or varenicline. In this subgroup the effect of telephone counselling was slightly smaller: RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.26; 12,865 participants, than that for all 65 trials, and the heterogeneity was slightly lower (I2 = 41%).

One additional trial tested the effect of telephone counselling as an adjunct to incentives. In this trial, telephone counselling had no effect on smoking cessation: RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.65; 1217 participants.

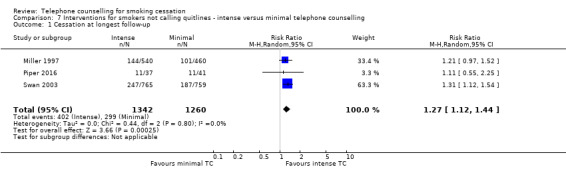

Counselling intensity

Three trials directly compared moderate‐intensity telephone counselling (three to five calls) to low‐intensity telephone counselling (one call). The pooled effect suggests that moderate‐intensity telephone counselling is more effective than minimal telephone counselling: RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.44; 2602 participants, with no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Interventions for smokers not calling quitlines ‐ intense versus minimal telephone counselling, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

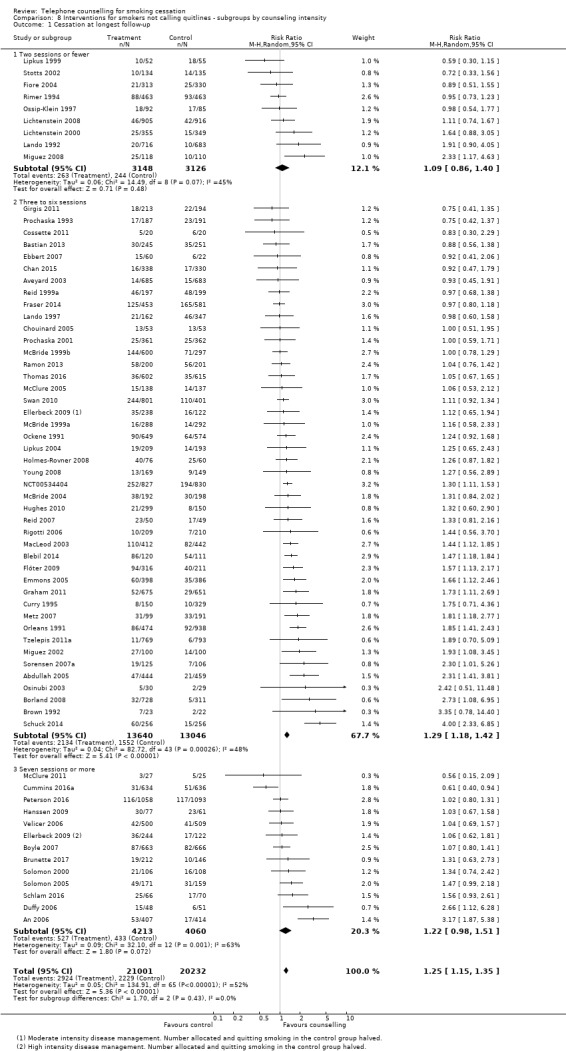

A subgroup analysis of the 65 trials comparing telephone counselling to control explored the impact of the number of calls planned as part of the intervention, using three categories; two or fewer, three to six, and seven or more calls. We had no strong a priori rationale for the choice of cut points, although the one‐to‐two‐call group predominantly captured trials with 'brief' interventions. We initially analysed these categories within the grouping by the control condition used above, but since the pattern of results was largely consistent we simplified the comparisons (Analysis 8.1). There was no evidence of statistically significant differences between subgroups (Chi2 = 1.70, df = 2 (P = 0.43), I2 = 0%). In two of the three subgroups in this analysis, we did not find a statistically significant effect, but confidence intervals were wide; these were the smaller subgroups. Nine trials provided low‐intensity telephone counselling, i.e. two or fewer calls: RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.40; 6274 participants; I2 = 45%, and 13 provided high‐intensity telephone counselling, i.e. seven or more calls: RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.51; 8273 participants; I2 = 63%.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Interventions for smokers not calling quitlines ‐ subgroups by counseling intensity, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

The largest subgroup was the group of 44 trials providing medium‐intensity telephone counselling, i.e. three to six calls. For studies in this subgroup telephone counselling had a statistically significant effect on smoking cessation rates: RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.42; 26,686 participants; I2 = 48%.

We also considered whether including the 14 trials of proactive counselling for quitline callers in their intensity subgroups would alter these conclusions. The overall effect of telephone counselling was slightly stronger: RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.37; 73,717 participants; I2 = 56%; analysis not shown, and the test for heterogeneity between subgroups was not statistically significant (P = 0.33).

To explain the higher heterogeneity among trials of high‐intensity telephone counselling, we conducted another post hoc subgroup analysis by baseline support. High‐intensity telephone counselling had no effect on cessation rates when provided as an adjunct to self‐help: RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.85 to 2.46, 3261 participants, I2 = 80%, analysis not shown; to pharmacotherapy: RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.38; 4654 participants; I2 = 48%; analysis not shown; or to a brief intervention or counselling: RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.63 to 2.73; 358 participants; analysis not shown. A further source of methodological heterogeneity between high‐intensity telephone counselling trials is that Velicer 2006 used an automated voice response system to provide tailored but prerecorded support. However, exclusion of this study did not have an effect on the pooled effect estimate or on statistical heterogeneity.

Motivation

A third subgroup analysis for the 65 trials explored the effect of motivation (Analysis 9.1). Twenty‐six studies specifically recruited smokers who wanted to make a quit attempt, including most of the studies (14/18) where pharmacotherapy was common to both intervention and control. Thirty‐nine studies did not state that participants were included on the basis of motivation, although a relatively high proportion may have been interested in quitting. The effect size was slightly larger for those 'selected' for motivation: RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.49; 17,877 participants; I2 = 70%, than for those 'unselected': RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.33; 23,356 participants; I2 = 26%, but the test for subgroup differences was non‐significant (Chi2 = 0.99, df = 1 (P = 0.32), I2 = 0%).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Interventions for smokers not calling quitlines ‐ subgroups by motivation, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

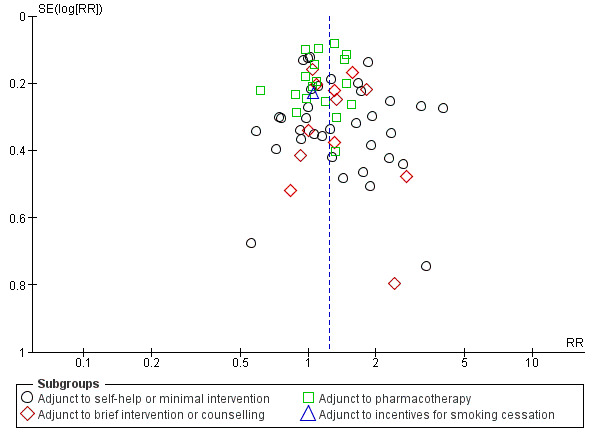

Results of a meta‐regression

In univariate meta‐regression analyses none of the potential moderators tested was a significant predictor of the effect (RR) of telephone counselling on smoking cessation rates. When all potential moderators were fitted together in a multivariate meta‐regression analysis (Appendix 2), the relative difference in the RR compared to pharmacotherapy as an adjunctive treatment was 35% greater for self‐help (RR change 1.35, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.67, P < 0.01), and 37% greater for a brief face‐to‐face intervention (RR change 1.37, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.79, P = 0.02). In the same multivariate model, studies that selected participants for motivation were associated with a 26% greater RR (RR change 1.26, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.52, P = 0.02), compared to studies that did not select participants for motivation. When telephone counselling intensity was fitted as a categorical variable, only medium intensity, compared to low intensity, was statistically significantly associated with a change in the RR (RR change 1.34, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.74, P = 0.02; analysis not shown).

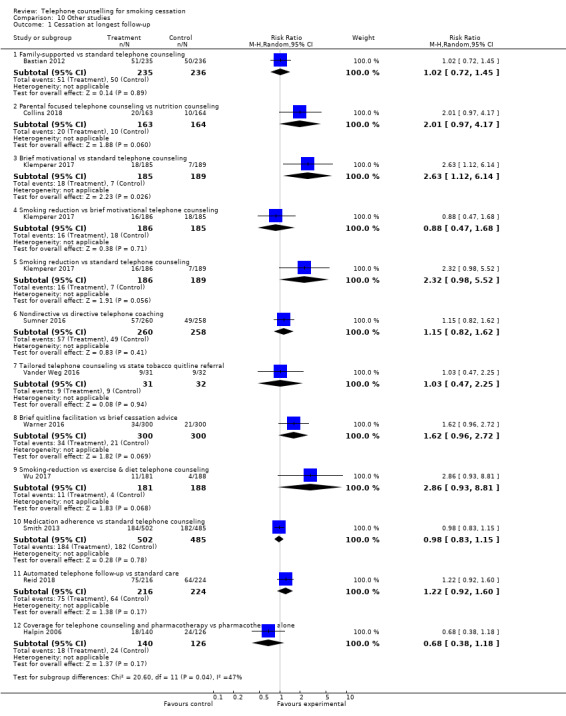

Other studies

We judged 10 other studies to be too dissimilar for pooling, but their results are shown in Analysis 10.1.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Other studies, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

Seven studies compared counselling matched in contact time, but using different approaches or containing different content, or both.

Bastian 2012 compared family‐supported telephone counselling with standard telephone counselling, and found no difference in self‐reported seven‐day point prevalent cessation at the 12‐month follow‐up: RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.45; 471 participants.

Collins 2018 compared individual behavioural telephone counselling focusing on parental smoking cessation and reduction of child second‐hand smoke exposure to individual telephone health education focusing on improving family nutrition on a budget. There was no statistically significant difference in cotinine‐verified seven‐day point prevalence abstinence at 12 months: RR 2.01, 95% CI 0.97 to 4.17; 327 participants.

Klemperer 2017 tested the effects of three different interventions: smoking reduction telephone counselling, brief motivational telephone counselling, and standard telephone counselling. There was a significant difference in seven‐day point prevalence abstinence at 12 months for the brief motivational versus standard telephone counselling: RR 2.63, 95% CI 1.12 to 6.14; 374 participants, but not for smoking reduction versus brief motivational telephone counselling: RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.68; 371 participants, or for smoking reduction versus standard telephone counselling: RR 2.32, 0.98 to 5.52, 375 participants.