Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate a possible mechanism of CD8+ regulatory T‐cell (Treg) production in an ovarian cancer (OC) microenvironment.

Materials and methods

Agilent microarray was used to detect changes in gene expression between CD8+ T cells cultured with and without the SKOV3 ovarian adenocarcinoma cell line. QRT‐PCR was performed to determine glycolysis gene expression in CD8+ T cells from a transwell culturing system and OC patients. We also detected protein levels of glycolysis‐related genes using Western blot analysis.

Results

Comparing gene expression profiles revealed significant differences in expression levels of 1420 genes, of which 246 were up‐regulated and 1174 were down‐regulated. Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analysis indicated that biological processes altered in CD8+ Treg are particularly associated with energy metabolism. CD8+ Treg cells induced by co‐culture with SKOV3 had lower glycolysis gene expression compared to CD8+T cells cultured alone. Glycolysis gene expression was also decreased in the CD8+ T cells of OC patients.

Conclusions

These findings provide a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of DEGs in CD8+ T cells cultured with and without SKOV3 and suggests that metabolic processes may be a possible mechanism for CD8+ Treg induction.

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the most lethal gynaecological cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer death in women. The ovarian tumour microenvironment establishes an immunosuppressive network that promotes tumour immune escape, thus promoting tumour growth.1 Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are the best characterized type of immunosuppressive cell that play a crucial role in the fine tuning of immune responses and the reduction of deleterious immune activation.2 Tumour‐induced biological changes in Treg cells may enable tumour cells to escape immunosurveillance.

CD4+ and CD8+ Treg cells are different Treg cell subtypes, which have distinctive co‐stimulatory molecules on the cell surface membrane. In OC patients, high percentages of CD4+ Treg cells have been detected in the peripheral blood3 and in the tumour microenvironment.4 In contrast, less is known about the function and existence of CD8+ Treg cells in cancer. Nevertheless, emerging evidence indicates that CD8+ Treg cells play an important role in various inflammatory disorders, autoimmune diseases and tumour immunity.5, 6, 7 Treg cells can be further classified into “naturally occurring” Tregs or inducible Tregs according to their different origins.8 Yukiko et al.9 previously reported that CD8+ Treg cells are induced in the prostate tumour microenvironment or in a cytokine milieu favouring Treg cell induction, while Andrew et al.10 suggested that they also accumulate or are activated by the immunosuppressive environment of the lung. In an earlier study, we observed an increase of CD8+ Treg cells in OC patients and found that they could be induced by OC cells in vitro.11

Several induced or naturally occurring CD8+ Treg cells have been discovered and functionally analysed, such as CD8+CD122+Tregs,12 CD8+CD103+Tregs,13 CD8+LAG‐3+Foxp3+CTLA‐4+Tregs,14 CD8+CD28−Tregs,15 CD8+CD75s+Tregs,16 CD8+IL‐16+Tregs,17 CD8+IL‐10+Tregs,18 CD8+CD28−CD56+Tregs,19 CD8+CD25+Foxp3+LAG3+Tregs,20 CD8+CD11c+Tregs21 and CD8+CD44−CD103+Tregs.22 However, detailed and comprehensive studies of CD8+ Treg cells have been hampered by the lack of key transcription factors and specific common markers to distinguish CD8+ Treg cells from conventional CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, the induction mechanism of CD8+ Treg cells in the OC microenvironment has not been clarified.

In this study, we used Agilent microarray analysis to detect changes in gene expression between CD8+ T cells cultured alone and co‐cultured with the SKOV3 ovarian adenocarcinoma cell line. We sought to confirm that OC cells have a direct effect on CD8+ T‐cell gene transcription. We also aimed to identify the underlying molecular changes in CD8+ Treg cells and potential signalling pathway mechanisms that induce CD8+ Treg cell generation in an OC microenvironment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and samples

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (permit number: SRFA‐061), and written informed consent was provided by the study participants. Peripheral blood samples were obtained from 22 new cases with OC, 20 new cases with benign ovarian tumour (BOT), and 20 age‐matched healthy donors treated at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University from 2014 to 2015. Patients who underwent surgery, radiotherapy or preoperative chemotherapy before blood sample collection were excluded from the study.

Of the 22 OC samples, 16 were of ovarian serous adenocarcinoma and six were of ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma. Of the 20 BOT samples, three were of ovarian mucinous cystadenoma, 14 were of ovarian serous cystadenoma and three were of ovarian teratoma.

2.2. Blood sample collection and CD8+ T‐cell isolation

Venous blood was collected from OC and BOT patients and healthy donors using EDTA tubes. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll‐Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (GE Health Care Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). CD8+ T cells were then separated using a CD8‐positive isolation kit (Dynal, Oslo, Norway).

2.3. Cell lines and culture conditions

SKOV3 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C in McCoy's 5A medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA).

2.4. Co‐culture of SKOV3 and CD8+ T cells

SKOV3 cells were cultured in six‐well plates in 2 mL McCoy's 5A medium (Invitrogen) with 10% FBS for 24 hours. For synchronization, CD8+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs using the CD8‐positive isolation kit (Dynal), achieving a purity were basically >95%. SKOV3 and CD8+ T cells (1:5) were then co‐cultured using the inner wells (0.4 μm pore size; Corning Costar, Corning, NY, USA) to separate the cell types. Specifically, SKOV3 cells (2 × 105/well) were incubated in the lower well in 2 mL RPMI 1640 medium with 10% AB serum (Gibco), and CD8+ T cells (1 × 106) were grown in the inner wells with or without SKOV3 cells (for controls) in 1 mL of the same medium. After 5 days of incubation, CD8+ T cells were washed and collected.

2.5. Microarray data production and analysis

CD8+ T cells from transwell and control groups were harvested, and total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The RNA quality, integrity and purity were measured using a bioanalyzer (2100 Bioanalyzer; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Gel electrophoresis demonstrated that each processed RNA had a 28s/18s >2.0 and 260/280 nm absorbance >1.8 (Table S1 and Figure S1), indicating that the samples were suitable for microarray analysis. Total RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA and then into labelled cRNA. The appropriate amount of cRNA was hybridized to the Agilent whole human genome 8 × 60 K microarray chip. All microarray experiments were performed at the microarray facility of CapitalBio Corporation (Beijing, China), and gene expression workflow was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Agilent Technologies). Data analysis was conducted using GeneSpring GX software (Agilent Technologies). The t test was used to identify genes that were differentially expressed between the SKOV3 transwell group and CD8+ T control group. Criteria for selecting differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were fold change (FC) >2.0 and P‐values <.05. Functional analysis was compiled using Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses.

2.6. Real‐time quantitative PCR for validation of microarray data

To validate the microarray results, glycolysis genes were selected to carry out real‐time quantitative PCR analysis. The remaining RNA of microarray analysis was applied to reverse‐transcript into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa Bio, Japan). Gene expression levels were analysis with ABI 7500 real‐time PCR (Applied Biosystems) by applying SYBR Green. The sequences of primers were as follows: mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), 5′‐CGGACTATGACCACTTGACTC‐3′ and 5′‐CCAAACCGTCT CCAATGAAAGA‐3′; hypoxia‐inducible factor 1(HIF1α), 5′‐CCATTAGAAAGCAGTTCCGC‐3′ and 5′‐TGGGTAGGAGATGGAGATGC‐3′; glucose transport 1 (Glut1), 5′‐TTGGCTCCGGTATCGTCAAC‐3′ and 5′‐GCCAGGACCCACTTCAAAGA‐3′; glucose‐6‐phosphate isomerase (GPI), 5′‐AGGCTGCTGCCACATAAGGT‐3′ and 5′‐AGCGTCGTGAGAGGTCACTTG‐3′; triosephosphate isomerase (TPI), 5′‐CCAGGAAGTTCTTCGTTGGGG‐3′ and 5′‐CAAAGTCGATGTAAGCGGTGG‐3′; enolase 1(Eno1), 5′‐TCATCAATGGCGGTTCTCA‐3′ and 5′‐TTCCCAATAGCAGTCTTCAGC‐3′; pyruvate kiase muscle(PKM2), 5′‐GCCGCCTGGACATTGACTC‐3′ and 5′‐CCATGAGAGAAATTCAGCCG AG‐3′; lactate dehydrogenase(LDHα), 5′‐CCAGCGTAACGTGAACATCTT‐3′ and 5′‐CCCATTAGGTAACGGAATCG‐3′; Forkhead box protein P3(Foxp3), 5′‐CAGCACATTCCCAGAGTTCCTC‐3′ and 5′‐GCGTGTGAACCAGTGGTAGATC‐3′; β‐actin, 5′‐TGGCCCCAGCACAATGAA‐3′ and 5′‐CTAAGTCATAGTCCG CCTAGAAGCA‐3′. The relative fold change of each gene was calculated by the expression 2−ΔΔCt, and β‐actin, as a housekeeping gene, was used to normalize these target genes expression.

2.7. Western blot analysis

Protein from co‐cultured cells was extracted using NE‐PER® nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Equal amounts of protein per lane were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoridemembranes (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Corresponding primary antibodies (anti‐mTORC1, 1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology; anti‐HIF1α, 1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; anti‐PKM2, 1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology; and anti‐GAPDH, 1:1000 dilution, ZSGB, Beijing, China) and a horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibody (ZSGB) were used to detect specific protein. The exposure was developed with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and X‐ray film.

3. Results

3.1. Gene expression profile of CD8+ T cells cultured with or without SKOV3 cells

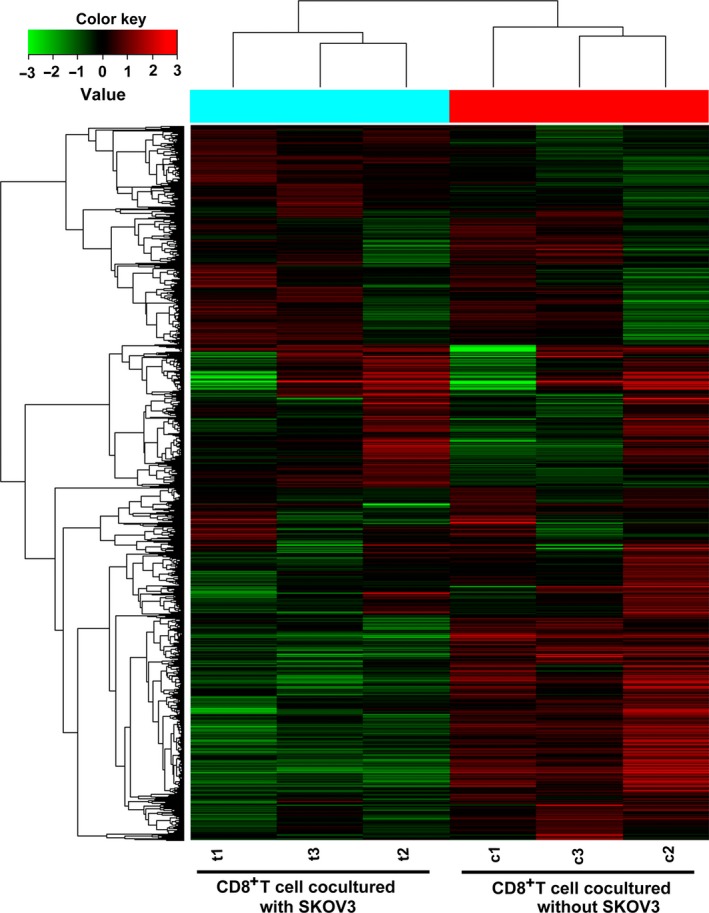

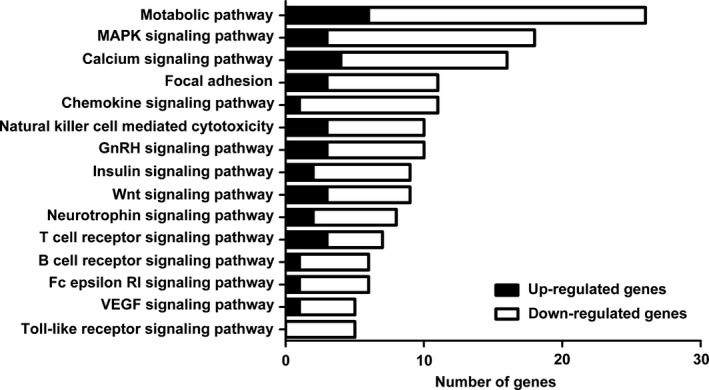

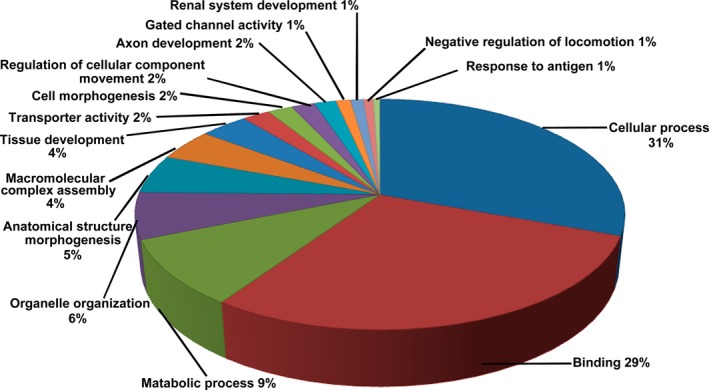

To identify the underlying molecular alterations and the potential induction mechanism of CD8+ Treg cells, we carried out gene expression analysis of CD8+ T cells cultured with and without SKOV3 cells. As shown in Fig. 1, we identified 1420 DEGs between the two groups, of which 246 were up‐regulated and 1174 were down‐regulated in CD8+ T cells cultured with SKOV3 cells relative to control CD8+ T cells cultured alone. To better understand the biological function of the DEGs, we performed GO and KEGG pathway analyses. Three hundred and seventeen DEGs (22.3%) could be mapped onto the KEGG signalling database. As shown in Fig. 2, the 15 most related pathways to DEGs were identified through KEGG analysis and included the metabolic pathway, MAPK signalling pathway, calcium signalling pathway, and focal adhesion and chemokine signalling pathway. Almost all of the 15 most related pathways were significantly down‐regulated in CD8+ T cells cultured with SKOV3 cells compared with the control group. These pathways were associated with the immune system, signal transduction and energy metabolism. GO analysis revealed that the DEGs were mainly involved in cellular processes, binding and metabolic processes (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Gene expression profile of CD8+T cells expanded from the co‐culture system. Hybridization signals produced by 8×60 K Agilent GeneChip. Each column represents an individual sample and each row represents a specific gene. The colour range reflects relative changes, with higher levels in red and lower ones in green. Bar plot shows normalized hybridization signals in six independent, microarray hybridizations using RNA from CD8+ T cells cultured with or without SKOV3 cells from three healthy controls

Figure 2.

Proportion of differentially expressed genes in significantly affected pathways. KEGG pathway analysis showed that the 15 most related pathways to DEGs included metabolic, mitogen‐activated protein kinase, calcium, focal adhesion, chemokine, natural killer cell‐mediated cytotoxicity, gonadotropin‐releasing hormone, insulin, Wnt, neurotrophin, T‐cell receptor, B cell receptor, Fc epsilon RI, vascular endothelial growth factor and the Toll‐like receptor signalling pathway. Almost all of these pathways were significantly down‐regulated in CD8+ T cells cultured with SKOV3 cells compared with CD8+ T cells cultured alone

Figure 3.

Pie charts showing the distribution of Gene Ontology (GO) categories for DEGs in CD8+ T cells from the co‐culture system using test for enrichment of common functions among DEG sets

3.2. Comparison of microarray results with previous findings

We validated the microarray outcome by comparing CD8+ Treg cell molecular markers identified by microarray with previous findings. Several CD8+ Treg cell markers have been functionally analysed, including CD122+, CD103+, CTLA‐4+, CD28−, CD75s+, IL‐16+, IL‐10+, CD56+, LAG3+, CD44− and CD11c+. More importantly, 73% of the CD8+ Treg cell subsets that had previously been reported were found to be differentially expressed in our microarray data. Our dataset was similar to that of previously reported study (Table 1). Notably, ITGAX, also known as CD11c, was shown to be up‐regulated 6.03‐fold (P=.0023) in CD8+ T cells cultured with SKOV3 cells compared with the control group. The top 20 significantly up‐ or down‐regulated genes are listed in Table 2. To our knowledge, these results are the first to show that many of these genes are associated with CD8+ Treg cells.

Table 1.

Previously reported biomarkers of CD8+Tregs

| CD8+Tregs | Gene symbol | Regulation | Fold change | P‐value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8+ CD122+ | CD122/IL2RB | Up | 1.38 | 0.045* | 12 |

| CD8+ CD103+ | CD103 | Up | 1.12 | 0.33 | 13 |

| CD8+LAG‐3+Foxp3+ CTLA‐4+ | CD152/CTLA‐4 | Up | 1.97 | 0.021* | 14 |

| CD8+ CD28− | CD28 | Down | −1.59 | 0.028* | 15 |

| CD8+ CD75s+ | CD75s/ST3GAL1 | Up | 1.05 | 0.024* | 16 |

| CD8+ IL‐16+ | IL‐16 | Up | 1.61 | 0.0067* | 17 |

| CD8+ IL‐10+ | IL‐10 | Up | 1.23 | 0.067 | 18 |

| CD8+ CD28− CD56+ | CD56/NCAM1 | Up | 1.49 | 0.011* | 19 |

| CD8+ CD25+ Foxp3+ LAG3+ | LAG3 | Up | 1.95 | 0.018* | 20 |

| CD8+ CD11c+ | CD11c/ ITGAX | Up | 6.03 | 0.0023* | 21 |

| CD8+ CD44−CD103+ | CD44 | Down | 1.14 | 0.13 | 22 |

Table 2.

Top 20 significantly up‐/down‐regulated genes differently expressed in CD8+ T cells cultured with and without SKOV3

| Top 20 up‐regulated genes | Top 20 down‐regulated genes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | Description | Unigene.NO | Fold change | P‐value | Gene symbol | Description | Unigene.NO | Fold change | P‐value |

| SIAH3 | Integrin, alpha X | 3687 | 8.93 | .0046 | ERO1LB | ERO1‐like beta (S. cerevisiae) | 56605 | 24.69 | .015 |

| HSPG2 | Heparan sulphate proteoglycan 2 | 3339 | 8.45 | .034 | HIST1H4L | Histone cluster 1, H41 | 8368 | 17.61 | .0022 |

| ITGAX | Integrin, alpha X (complement component 3 receptor 4 subunit) | 3687 | 6.03 | .0023 | CHAC1 | ChaC glutathione‐specific gamma‐glutamylcyclotransferase 1 | 79094 | 16.09 | .044 |

| ULK4 | unc‐51 like kinase 4 | 54986 | 5.78 | .015 | PIR | Pirin (iron‐binding nuclear protein) | 8544 | 13.66 | .013 |

| CD160 | CD160 molecule | 11126 | 4.38 | .012 | HIST1H4A | Histone cluster 1, H4a | 8359 | 13.56 | .0088 |

| PRSS23 | Protease, serine, 23 | 11098 | 4.35 | .039 | HIST1H4E | Histone cluster 1, H4e | 8367 | 11.01 | .024 |

| JAKMIP1 | Janus kinase and microtubule interacting protein 1 | 152789 | 4.09 | .023 | HIST1H2AG | Histone cluster 1, H2ag | 8969 | 10.52 | .0070 |

| FCRL2 | Fc receptor‐like 2 | 79368 | 3.89 | .032 | HIST1H3H | Histone cluster 1, H2 h | 8969 | 10.52 | .072 |

| SDK2 | Sidekick cell adhesion molecule 2 | 54549 | 3.75 | .00061 | SLC7A11 | Solute carrier family 7 (anionic amino acid transporter light chain, xc‐system), member 11 | 23657 | 9.68 | .023 |

| IMMP2L | IMP2 inner mitochondrial membrane peptidase‐like | 83943 | 3.74 | .011 | ULBP1 | UL16 binding protein 1 | 80329 | 9.43 | .0039 |

| SMCR6 | Smith–Magenis syndrome chromosome region, candidate 6 | 140772 | 3.74 | .032 | HIST1H2AI | Histone cluster 1, H2ai | 8329 | 8.40 | .0016 |

| GCET2 | Germinal centre expressed transcript 2 | 257144 | 3.71 | .030 | VSX1 | Visual system homeobox 1 | 30813 | 8.07 | .012 |

| FGGY | FGGY carbohydrate kinase domain containing | 55277 | 3.66 | .033 | TSPAN16 | Tetraspanin 16 | 26526 | 8.015 | .024 |

| TXNDC3 | Thioredoxin domain containing 3 | 51314 | 3.63 | .015 | HIST4H4 | Histone cluster 4, H4 | 121504 | 7.34 | .026 |

| FCGR2A | Fc fragment of IgG, low affinity IIa | 2212 | 3.52 | .029 | HIST1H3B | Histone cluster 1, H3b | 8358 | 7.28 | .033 |

| SLC14A1 | Solute carrier family 14 (urea transporter) | 6563 | 3.49 | .0067 | HIST1H1A | Histone cluster 1, H1a | 3024 | 6.95 | .0016 |

| ATP9A | ATPase, class II, type 9A | 10079 | 3.43 | .043 | C14orf82 | Chromosome 14 open reading frame 82 | 145438 | 6.93 | .016 |

| DNHD1 | Dynein heavy chain domain 1 | 144132 | 3.41 | .013 | SNX31 | Sorting nexin 31 | 169166 | 6.73 | .012 |

| FCRL3 | Fc receptor‐like 3 | 115352 | 3.38 | .018 | OR4N2 | Olfactory receptor, family 4, subfamily N, member 2 | 390429 | 6.72 | .0032 |

| CHST15 | Carbohydrate sulfotransferase 15 | 51363 | 3.35 | .0076 | ATF3 | Activating transcription factor 3 | 467 | 6.66 | .0053 |

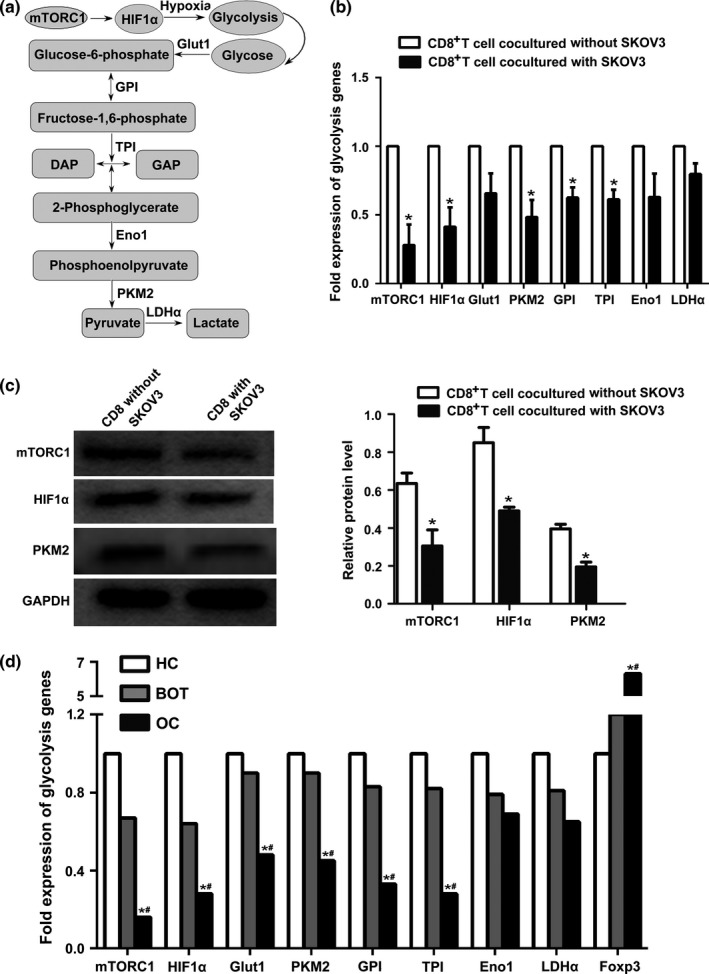

3.3. Validation of glycolysis genes by quantitative real‐time reverse transcriptase PCR and Western blotting

GO and KEGG analysis of DEGs indicated that biological processes altered in CD8+ Treg are particularly associated with energy metabolism. We, therefore, focused our attention on the glycolysis pathway (Fig. 4a). To validate our microarray results, we examined the expression of eight glycolysis genes by quantitative real‐time reverse transcriptase (qRT)‐PCR (mTORC1, HIF1α, Glut1, PKM2, GPI, TPI, Eno1 and LDHα). A cDNA pool derived from the same cells used to perform the microarray analysis was the template for qRT‐PCR. Compared with CD8+ T cells cultured without SKOV3 cells, glycolysis gene expression showed varying degrees of decline in CD8+ T cells cultured with SKOV3 cells (Fig. 4b). The expression of mTORC1, HIF1α, PKM2, GPI and TPI was significantly decreased in co‐cultured cells compared with the control group. The expression levels of almost all glycolysis genes were consistent with the microarray data, with the exception of HIF1α (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Validation of DEGs by real‐time PCR and western blotting. (a) Diagram of the glycolytic pathway, including the eight glycolysis genes (mTORC1, HIF1α, Glut1, PKM2, GPI, TPI, Eno1 and LDHα) selected for further validation. (b) Glycolysis gene mRNA expression in CD8+ T cells from the co‐culture system was detected using the RNA remaining from microarray analysis. The expression of mTORC1, HIF1α, PKM2, GPI and TPI mRNA was significantly lower in co‐cultured groups (*P<.05) compared with CD8+ T cells cultured alone. Data represent the mean ± SD. (c) Protein expression of mTORC1, HIF1α and PKM2 was analysed using western blotting. Expression of all three proteins decreased significantly in CD8+ T cells cultured with SKOV3 cells (*P<.05) compared with CD8+ T cells cultured alone. Data represent the mean ± SD. (d) Expression of glycolysis gene mRNA in CD8+ T cells from ovarian cancer patients (OC; n=22), benign ovarian tumour patients (BOT; n=20) and healthy controls (HC; n=20). MTORC1, HIF1α, Glut1, PKM2, GPI and TPI were expressed at lower levels in OC patients than in both BOT patients and healthy controls. *P<.05 compared with healthy control group, # P<.05 compared with benign ovarian tumour group

Table 3.

Validation by real‐time RT‐PCR of glycolytic genes

| Genes | Microarray | RT‐PCR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulation | Fold change | P‐value | Regulation | Fold change | P‐value | |

| mTORC1 | Down | −1.41 | .013* | Down | −3.57 | .0012* |

| HIF1α | Down | −1.10 | .29 | Down | −2.43 | .015* |

| GLUT1 | Down | −1.0 | .93 | Down | −1.52 | .08 |

| PKM2 | Down | −1.86 | .045* | Down | −2.08 | .014* |

| GPI | Down | −1.37 | .0056* | Down | −1.60 | .013* |

| TPI | Down | −1.25 | .003* | Down | −1.64 | .0051* |

| ENO1 | Down | −1.11 | .12 | Down | −1.58 | .096 |

| LDHa | Down | −1.03 | .78 | Down | −1.27 | .060 |

Further confirmation of this was achieved using Western blotting (Fig. 4c). This showed that the expression of mTORC1, HIF1α and PKM2 decreased significantly (P<.05) in CD8+ T cells cultured with SKOV3 cells compared with CD8+ T cells cultured alone.

3.4. Decreased glycolysis gene expression in patients with ovarian cancer

We next utilized semi‐quantitative RT‐PCR to investigate the expression of glycolysis genes and Foxp3 mRNA in CD8+ T cells from OC patients (n=22), BOT patients (n=20) and healthy controls (n=20). As shown in Fig. 4d, mTORC1, HIF1α, Glut1, PKM2, GPI and TPI were expressed at lower levels in OC patients than in either BOT patients or healthy controls (both P<.05). There was no obvious difference in the expression of glycolysis genes between benign tumour and healthy control groups. By contrast, Foxp3 mRNA expression was significantly higher in peripheral blood samples of patients with OC than in benign tumours and healthy controls. The expression of Foxp3 was, therefore, negatively correlated with that of glycolysis genes in OC patients. Together with the data presented in Fig. 4, these results indicate that genes of the glycolysis pathway play an important role in the differentiation and generation of CD8+ Treg cells.

4. Discussion

As a suppressor T‐cell subset, CD8+ Treg cells have been the focus of much research because of their critical roles in the inhibition of antitumour immunity and the promotion of tumour growth.23 Previously, Meloni et al.24 found that the CD8+ CD28− T‐cell subset was significantly increased in the peripheral blood of patients with lung cancer, while Yang et al.25 reported that a higher percentage of intrahepatic CD8+FoxP3+ Treg cells was associated with tumour‐node‐metastasis (TNM) stage in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Moreover, Chen et al.26 showed that CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ and CD8+CD28− Treg cells dropped significantly in number in non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients undergoing surgery. These data together suggest that the tumour microenvironment might be at least partially responsible for the enhanced generation of CD8+ Treg cells. However, the underlying mechanism of CD8+ Treg induction remained unknown.

In our previous study, we demonstrated that CD8+ Treg cells were increased in the peripheral blood and fresh tumour tissues of OC patients and that the ovarian microenvironment could convert CD8+ effector T cells into suppressor cells in vitro.11 Thus, to investigate possible mechanisms involved in the induction of CD8+ Treg cells, we herein cultured CD8+ T cells with OC cells and used high‐throughput microarray technology to identify 1420 genes showing differential expression between CD8+ T cells cultured with and without SKOV3 cells. This was the first time that many of these genes had been associated with CD8+ Treg cells. We also observed that 73% of previously reported CD8+ Treg cell molecular markers were significantly differentially expressed between the two groups. This correlation with previous findings reinforces our confidence in the microarray platform used in this study.

Investigations into CD8+CD11c+ T cells in recent years have produced conflicting results. For example, Beyer et al.27 reported increased numbers of CD8+CD11c+ T cells during inflammation, representing an important class of adaptive immune regulators. By contrast, Chen et al.21 observed that CD11chighCD8+ regulatory T‐cell feedback inhibited the CD4 T‐cell immune response by killing activated CD4 T cells via the Fas/Fas ligand pathway. In our study, CD11c/ITGAX was up‐regulated 6.03‐fold (P=.0023) in CD8+ T cells cultured with SKOV3 cells compared with CD8+ T cells cultured alone, providing further evidence for the fact that CD8+ T cells co‐expressing CD11c are a subset of CD8+ Treg cells.

To better understand DEG biological functions, we performed GO functional enrichment analyses and KEGG pathway analyses. Mockler et al.28 previously reported that the tumour microenvironment influences T‐cell immune responses by altering cellular metabolism. Moreover, Simeoni et al.29 suggested that metabolic processes and immune responses are mainly activated by T‐cell differentiation. Our results showed that the DEGs identified in this study were involved in the biological function of cell energy metabolism. This process refers to the metabolism of three major nutrients associated with energy production and usage, namely glucose, lipid and protein. Here, we paid attention to the glycolysis metabolism of CD8+ T cells cultured with and without SKOV3 cells.

mTOR is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine protein kinase implicated in the regulation of cellular metabolism, protein synthesis, differentiation, survival and growth. It has also been reported to play an important role in T‐cell differentiation.30 mTOR is the catalytic subunit of two distinct complexes, called mTORC1 and mTORC2, each with unique functions and downstream targets.31 HIF1, a heterodimer comprised HIF1α and HIF1β subunits, is a major regulator of cellular metabolism and a key transcription factor orchestrating the expression of glycolytic enzymes.32 Finlay et al.33 demonstrated that mTORC1 regulates glucose metabolism in CD8+ cytotoxic T‐lymphocytes through regulating the expression of HIF1α. Research by Shi et al.34 showed that the mTORC1‐HIF1α‐pathway‐dependent glycolytic pathway includes a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells and that HIF1α was required to promote TH17 but to inhibit Treg cell differentiation.

The process of glycolysis depends on a chain of reactions catalysed by multiple enzymes (Fig. 4a). To elucidate the role of the CD8+ T‐cell glycolysis metabolism in a co‐culture system, we showed that the expression of glycolysis genes in CD8+ T cells was decreased in the SKOV3 cell co‐culture group. Additionally, glycolysis genes were expressed at lower levels in OC patients than in both BOT patients and healthy controls. Interestingly, the expression of Foxp3 was negatively correlated with that of glycolysis genes in OC patients. These data suggest that the glycolysis pathway plays an important role in the differentiation and generation of CD8+ Treg cells.

In conclusion, gene expression patterns were shown to differ significantly between CD8+ T cells cultured with and without SKOV3 cells in this study, and microarray analysis suggested that the glycolysis pathway plays an important role in CD8+Treg induction. These observations provide a basis for the understanding of the process of CD8+Treg induction. Analysis of the prevalence of different Treg cell subpopulations, as well as their suppressive mechanisms in an ovarian microenvironment, is critical to our understanding of immunosuppression in OC patients and will help devise new strategies to improve the therapeutic potential of cancer vaccines. Further experimental exploration is, therefore, needed to elucidate the mechanism of CD8+Treg production in an ovarian microenvironment.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- OC

ovarian cancer

- BOT

benign ovarian tumour

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- FBS

foetal bovine serum

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- GO

gene ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- MTORC1

mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1

- HIF1α

hypoxia‐inducible factor 1

- Glut1

glucose transport 1

- PKM2

pyruvate kinase muscle 2

- GPI

glucose‐6‐phosphate isomerase

- TPI

triosephosphate isomerase

- Eno1

enolase 1

- LDHα

lactate dehydrogenase

- Foxp3

forkhead box protein P3

Supporting information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the technical support from the National Key Clinical Department of Laboratory Medicine of Jiangsu Province Hospital. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81272324, 81371894, 81501817) and Key Laboratory for Medicine of Jiangsu Province of China (grant no. XK201114), a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis and decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Latha TS, Panati K, Gowd DS, Reddy MC, Lomada D. Ovarian cancer biology and immunotherapy. Int Rev Immunol. 2014;33:428–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Facciabene A, Motz GT, Coukos G. T‐regulatory cells: Key players in tumor immune escape and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2162–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Erfani N, Hamedi‐Shahraki M, Rezaeifard S, Haghshenas M, Rasouli M, Samsami Dehaghani A. FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in peripheral blood of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Iran J Immunol. 2014;11:105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joosten SA, Ottenhoff TH. Human CD4 and CD8 regulatory T cells in infectious diseases and vaccination. Hum Immunol. 2008;69:760–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li J, Huang ZF, Xiong G, et al. Distribution, characterization, and induction of CD8+ regulatory T cells and IL‐17‐producing CD8+ T cells in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2011;9:189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alvarez Arias DA, Kim HJ, Zhou P, et al. Disruption of CD8+ Treg activity results in expansion of T follicular helper cells and enhanced antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang H, Kong H, Zeng X, Guo L, Sun X, He S. Subsets of regulatory T cells and their roles in allergy. J Transl Med. 2014;12:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kiniwa Y, Miyahara Y, Wang HY, et al. CD8+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells mediate immunosuppression in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6947–6958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jarnicki AG, Lysaght J, Todryk S, Mills KH. Suppression of antitumor immunity by IL‐10 and TGF‐beta‐producing T cells infiltrating the growing tumor: influence of tumor environment on the induction of CD4+ and CD8+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:896–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang S, Ke X, Zeng S, et al. Analysis of CD8+ Treg cells in patients with ovarian cancer: a possible mechanism for immune impairment. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:580–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rifa'i M, Kawamoto Y, Nakashima I, Suzuki H. Essential roles of CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells in the maintenance of T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1123–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uss E, Rowshani AT, Hooibrink B, Lardy NM, van Lier RA, ten Berge IJ. CD103 is a marker for alloantigen‐induced regulatory CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:2775–2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boor PP, Metselaar HJ, Jonge S, Mancham S, van der Laan LJ, Kwekkeboom J. Human plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce CD8(+) LAG‐3(+) Foxp3(+) CTLA‐4(+) regulatory T cells that suppress allo‐reactive memory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1663–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ben‐David H, Sharabi A, Dayan M, Sela M, Mozes E. The role of CD8+CD28 regulatory cells in suppressing myasthenia gravis‐associated responses by a dual altered peptide ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:17459–17464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zimring JC, Kapp JA. Identification and characterization of CD8+ suppressor T cells. Immunol Res. 2004;29:303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mottonen M, Heikkinen J, Mustonen L, Isomäki P, Luukkainen R, Lassila O. CD4+ CD25+ T cells with the phenotypic and functional characteristics of regulatory T cells are enriched in the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:360–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilliet M, Liu YJ. Generation of human CD8 T regulatory cells by CD40 ligand‐activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:695–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Klimiuk PA, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. IL‐16 as an anti‐inflammatory cytokine in rheumatoid synovitis. J Immunol. 1999;162:4293–4299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Joosten SA, van Meijgaarden KE, Savage ND, et al. Identification of a human CD8+ regulatory T cell subset that mediates suppression through the chemokine CC chemokine ligand 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8029–8034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen Z, Han Y, Gu Y, et al. CD11c(high) CD8+ regulatory T cell feedback inhibits CD4 T cell immune response via Fas ligand‐Fas pathway. J Immunol. 2013;190:6145–6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ho J, Kurtz CC, Naganuma M, Ernst PB, Cominelli F, Rivera‐Nieves J. A CD8+/CD103high T cell subset regulates TNF‐mediated chronic murine ileitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:2573–2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang RF. CD8+ regulatory T cells, their suppressive mechanisms, and regulation in cancer. Hum Immunol. 2008;69:811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meloni F, Morosini M, Solari N, et al. Foxp3 expressing CD4+ CD25+ and CD8+CD28‐ T regulatory cells in the peripheral blood of patients with lung cancer and pleural mesothelioma. Hum Immunol. 2006;67:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang ZQ, Yang ZY, Zhang LD, et al. Increased liver‐infiltrating CD8+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells are associated with tumor stage in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:1180–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen C, Chen D, Zhang Y, et al. Changes of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ and CD8+CD28‐ regulatory T cells in non‐small cell lung cancer patients undergoing surgery. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;18:255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beyer M, Wang H, Peters N, et al. The beta2 integrin CD11c distinguishes a subset of cytotoxic pulmonary T cells with potent antiviral effects in vitro and in vivo. Respir Res. 2005;6:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mockler MB, Conroy MJ, Lysaght J. Targeting T cell immunometabolism for cancer immunotherapy; understanding the impact of the tumor microenvironment. Front Oncol. 2014;4:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Simeoni O, Piras V, Tomita M, Selvarajoo K. Tracking global gene expression responses in T cell differentiation. Gene. 2015;569:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:21–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nizet V, Johnson RS. Interdependence of hypoxic and innate immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:609–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Finlay DK. mTORC1 regulates CD8+ T‐cell glucose metabolism and function independently of PI3K and PKB. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:681–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shi LZ, Wang R, Huang G, et al. HIF1 alpha‐dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1367–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials