Abstract

Exosomes are small membrane vesicles 50‐150 nm in diameter released by a variety of cells, which contain miRNAs, mRNAs and proteins with the potential to regulate signalling pathways in recipient cells. Exosomes deliver nucleic acids and proteins to participate in orchestrating cell‐cell communication and microenvironment modulation. In this review, we summarize recent progress in our understanding of the role of exosomes in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). This review focuses on recent studies on HCC exosomes, considering biogenesis, cargo and their effects on the development and progression of HCC, including chemoresistance, epithelial‐mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, metastasis and immune response. Finally, we discuss the clinical application of exosomes as a therapeutic agent for HCC.

Keywords: carcinogenesis, exosomes, hepatocellular carcinoma, tumour microenvironment

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the first observation of exosomes as “trash cans” that simply allows cells to dispose of unwanted proteins,1 the further functions of exosomes have recently been explored. It has been proven that exosomes could be secreted by most cell types.2 With regard to the liver, exosomes mainly released from three types of cells: hepatocytes, non‐parenchymal immune cells (such as Kupffer cells, natural killer cells, T cells and B cells) and non‐parenchymal liver cells (eg, liver stellate cells).3 As for a subtype of the extracellular vesicle, they implicated in many normal and pathological processes.4 Especially in tumours, they play a vital role in tumour chemoresistance, angiogenesis, epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis by modulating extracellular communication. On the one hand, tumour cells impact adjacent cells through exosomes and establish tumorigenic microenvironment. On the other hand, the stroma cells (such as stellate cells and MSCs) and immune cells could influence tumour cells to promote or prevent tumorigenesis through exosomes.5

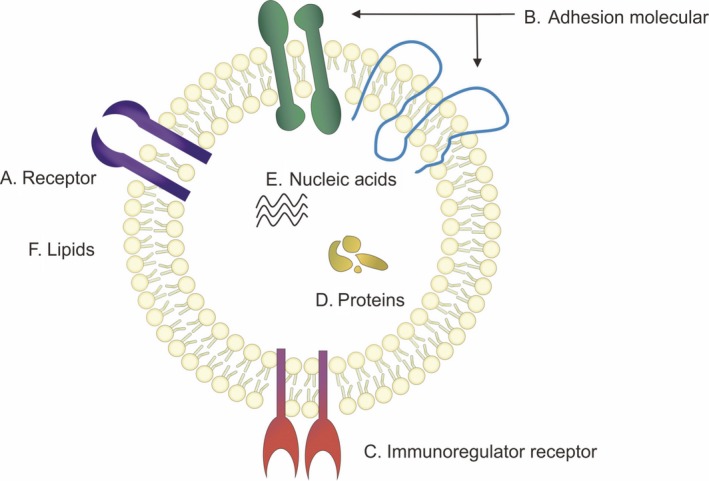

Importantly, the versatile roles of exosomes are mostly determined by their donor cells and their contents including lipids, nucleic acids and proteins6, 7 (Figure 1). The information has been deposited in ExoCarta (www.exocarta.org).

Figure 1.

The structure of exosome. (A) Receptors on exosome membrane are different due to the donor cells (eg. EGFR). (B) Adhesion molecular includes integrin α/β and the tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81, CD82). (C) Immunoregulator receptor includes MHCI, MHCII and CD86. (D) Exosomal cargo proteins. (E) Nucleic acids. (F) Lipids

Furthermore, exosomes have the potential to be utilized in therapeutic tools due to their numerous characteristics, which we will discuss as follow.

2. EXOSOMES BIOGENESIS

Recently, there has been a great interest in the study of exosomes as the major regulator in tumorigenesis. Based on recent studies, endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) is considered as the main mechanism of exosomes production8 (Figure 2), which was first defined as a ubiquitin‐dependent protein sorting pathway in yeast.9

Figure 2.

The ESCRT complex promotes the formation of exosomes. A, EXCRT‐0 recognizes ubiquitinated cargo and then initiates the budding of exosomes. B, EXCRT‐0 recruits EXCRT‐I; then, EXCRT‐II is recruited by EXCRT‐I and may contribute to cargo clustering. C, EXCRT‐III degrades EXCRT‐0, EXCRT‐I and EXCRT‐II to promote the exosomes budding. This process is accompanied by the deubiquitinated of cargoes. D, EXCRT‐III is disassembled by Vps‐4, resulting in the exosomes budding

Vps4, one of the compositions of ESCRT complex, is known as a multimeric mechanoenzyme with an ATP‐binding domain which binds to ESCRT‐III subunits then provides energy through dehydrating ATP to disassociate them from the cell membrane.10, 11, 12 Surprisingly, Wei et al13 found that the downregulation of Vps4 is an independent risk factor for recurrence‐free survival of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients. Their study showed that Vps4A is associated with inhibition of biological activity of HCC cell‐derived exosomes and the recipient cells’ response to exosomes. PI3K/Akt signalling pathway might be a candidate mechanism due to its inactivation occurrence while Vps4 overexpressed in HCC cells.13 This study extends our knowledge that the exosomes production is associated with tumour progression, metastasis and worse prognosis.

Numerous studies demonstrated that exosomal cargo sorting is an active process.9, 14 The content of exosomes is determined by their donor cells. Up to now, a bunch of molecules have been found in exosomes such as heat shock proteins (eg, Hsp90 and Hsp70),15, 16 cytoskeletal proteins (actin, tubulin, cofilin, etc), lipids and enzymes, along with RNAs, including microRNAs, mRNAs, and other non‐coding RNAs (ncRNAs), and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and single strand DNA (ssDNA).17

3. EXOSOME CONTENTS

It has been reported that cancer cells produce and secrete an increased amount of exosomes as tumour‐inducing agents compared to non‐cancer cells.18 Exosomes play a critical role in manipulating the microenvironment that favours cancer cells19 by transferring oncogene,20 inducing angiogenesis,21 establishing pre‐metastasis niche22 and inducing EMT in recipient cells.23 Importantly, it has been demonstrated that the functions of exosomes are mainly determined by their cargoes24 which are different in various situations. These results indicated that there is a possibility to reveal the mechanisms that altered by exosomes uptake.25 Thus, we summarize the molecules found in exosomes in patients with HCC including proteins and RNAs (miRNA, lncRNA), and the purpose is to clarify the mechanism by which exosomes promote HCC progression.

3.1. Proteins

According to Vesiclepedia database, the number of proteins in exosomes is at ~1800 levels, and in HCC cell line‐derived exosomes, 213 unique proteins were found by mass spectrometry analysis.26 Exosomal proteins include cargo proteins and membrane proteins, depending on location in exosomes. Membrane proteins are associated with exosomal internalization by recipient cells and target organ selection. Cargo proteins composition is different in exosomes during tumour progression in different cells.27

3.2. Nucleic acids

Considering that liver biopsy, a gold‐standard method for monitoring and evaluating liver disease, has the risk of bleeding and infection, noninvasive diagnostic tools are urgently needed.18 Thus, a “Liquid biopsy” which implements early diagnosis and prognostic prediction of HCC through serum exosomes becomes more attractive.18, 28 However, “Liquid biopsy” is based on markers for HCC development and progression. In addition to protein, it has been demonstrated that nucleic acids, particularly miRNAs, are also one of the compositions of exosomes29 (Table 1). Kogure et al30 have documented 134 miRNAs expressed in Hep3B‐derived exosomes and 11 of miRNAs exclusively expressed in exosomes compared to their donor cells.

Table 1.

miRNAs found in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)‐derived exosomes

| miRNA | Source of exosome | Source of compared | Expression level | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR‐584 | HEP3B‐exo | HEP3B cell | Exclusively expressed in exosomes derived from Hep3B human HCC cells | Target TAK1, enhance transformed cell growth in recipient cells | 27 |

| miR‐517c | |||||

| miR‐378 | |||||

| miR‐520f | |||||

| miR‐142‐5p | |||||

| miR‐451 | |||||

| miR‐518d | |||||

| miR‐215 | |||||

| miR‐376a | |||||

| miR‐133b | |||||

| miR‐367 | |||||

| miR‐18a | Serum of HCC patients | LC and CHB patients | Upregulated | Novel serological biomarkers for HCC | 96 |

| miR‐221 | |||||

| miR‐222 | |||||

| miR‐224 | |||||

| miR‐106b | Serum of HCC patients | CHB patients | Downregulated | ||

| miR‐122 | |||||

| miR‐195 | |||||

| miR‐101 | |||||

| miR‐21 | Serum of HCC patients | CHB patients and healthy volunteers | Upregulated | Potential biomarker for HCC diagnosis | 98 |

| miR‐10b | Rats in different stage of HCC (normal liver, degeneration, brosis, cirrhosis, early HCC and late HCC) | Compared with AFP | Upregulated | Potential biomarkers for non‐virus infected HCC screening and cirrhosis discrimination; Their combination is more | 76 |

| miR‐21 | |||||

| miR‐122 | Downregulated | ||||

| miR‐200a | |||||

| miR‐125b | Serum of HCC patients | CHB patients and LC patients | Downregulated | Prognostic marker for HCC; An independent predictive factor for TTR and OS | 106 |

| miR‐665 | Serum of HCC patients | Healthy volunteers | Upregulated | Prognostic and diagnostic marker for HCC | 95 |

| miR‐718 | Serum from patients with no recurrence | Serum from patients who suffer HCC recurrence after | Downregulated | Target HOXB8, suppress cell proliferation | 105 |

Li et al29 reported that miR‐429 the significant prognosis factor for HCC is secreted into exosomes and taken up by recipient cell. Sohn et al compared the serum level of exosomal miRNAs in HCC, CHB and LC patients. Their study showed that the expression level of miR‐18a, miR‐221 and miR‐222 is significantly higher and that of the miR‐101, miR‐106b, miR‐122 and miR‐195 is lower in HCC patient comparing with CHB or LC.31 These raised the possibility of exosomal cargoes, particularly miRNAs, serving as biomarkers for HCC formation and progression.

Sugimachi et al have shown that miR‐718 can serve as a preoperative biomarker for the prediction of HCC recurrence after surgery. Their study showed that the expression level of miR‐718 in exosomes collected in patients with HCC recurrence after liver transplantation was significantly lower than those without HCC recurrence. Furthermore, a validated cohort study showed that decreased expression of miR‐718 and overexpression of the potential target gene HOXB8 were associated with tumour aggressiveness and poor prognosis.32 These results show the potent value of selecting patients who need liver transplantation, and therefore use donor organs properly. In addition, Liu et al33 have reported that exosomal miR‐125b could serve as a prognostic marker due to miR‐125b level in exosomes was an independent factor for time to recurrence and overall survival of HCC patients.

Although exosomal miRNAs might be useful tools to reflect their donor cells feature that can be used as biomarkers for tumour cell, the extent to which exosomal miRNAs play a role in HCC remains poorly understood. Furthermore, there are controversial results of miRNA expression level and functions under specific conditions, and some cohort studies did not include healthy participants, due to the conveniences of collecting serum sample from patients with liver disease compared with healthy people.31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42

Recently, increased studies have focused on a role of long non‐coding RNA in exosome in addition to miRNA. Long non‐coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are defined as non‐coding RNAs more than 200 nucleotides in length.43, 44, 45, 46 Lnc‐ROR and lnc‐LVDR which expressed in HCC‐derived exosome had widely explored.47, 48, 49 It has recently been found that the ultraconserved lncRNA (ucRNA) expression is dramatically altered within extracellular vesicles as compared to donor cells.50, 51 For instance, the ucRNA named TUC339 is mostly enriched in HCC cell‐derived exosomes and promotes HCC growth and spread. Above all, these studies explored the nucleic acids that transferred within cells via exosome that modulate tumour cells and function as an intracellular signalling mediators.

4. MECHANISMS OF INTERACTION BETWEEN EXOSOMES AND RECIPIENT CELLS

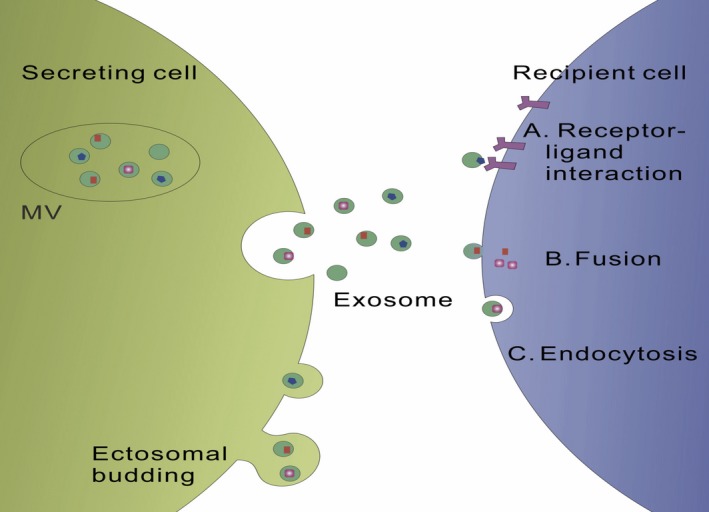

Recently, dynamic regulation of exosomes uptake by recipient cells extensively explored. There are several models considered as a possible mechanism of exosomes internalization by recipient cells, the receptor‐mediated endocytosis, and classic fluid‐phase endocytosis52 (Figure 3). The latter one is considered to be a common approach for microvesicle internalization that lacks the specificity. However, Schneider et al53 documented that the mechanism of exosomes update by alveolar epithelial cells is similar, but not same, to classic macropinocytosis depending on dynamin function and actin polymerization.

Figure 3.

Exosomes are taken up by target cells through three main patterns. (A) Receptor derived exosomes uptake. (B) Membrane fusion. (C) Endocytosis by phagocytosis

In contrast, receptor‐mediated endocytosis attracted more interest for its cell‐specific feature that allows further modifications of exosomes for therapeutic use.53 Integrins are one of the receptors commonly expressed on exosomes membrane. It has been found that exosomal integrins have the ability to predict metastatic organ. For instance, exosomes expressing ITGαvβ5 specifically bind to Kupffer cells, mediating liver tropism whereas exosomal ITGα6β4 and ITGα6β1 bind lung‐resident fibroblasts and epithelial cells governing lung tropism.54 Thus, targeting exosomal integrins has a potential to prevent tumour metastasis.54

Furthermore, the blockade of Scavenger Receptor Class A family (SR‐A), a novel monocyte/macrophage uptake receptor for exosomes, with dextran sulphate in vivo enhances tumour accumulation by reducing exosomes clearance in mice liver.55 These findings have advanced the development of exosomes therapeutic method.

Intriguingly, the process of taking up exosomes is not always necessary for modulating recipient cells function; even it is a basis of transporting exosomal cargo. Muller et al56 showed that the tumour‐derived exosomes (TEX) mediate Treg suppressor functions dependent on cell surface signalling and do not require TEX internalization by recipient cells.

Furthermore, an oncogenic transformation of the recipient cells was observed following exposure of exosomes isolated from serum of cancer patients.57 This phenomenon has a synergy when combined with mutations in tumour suppression gene in recipient cells.57, 58 Collectively, these results indicate a hypothesis that the migration of cancer cells might not be necessary for metastasis and that this can be achieved by exosomal transport.

5. THE ROLES OF EXOSOMES IN HCC PROGRESSION

Intercellular communication is essential in liver physiology and pathology including tumorigenesis since liver is a multicellular organ. Exosomes provide new form of intercellular communication, besides autocrine, paracrine and cell‐cell contact. Moreover, this process could be affected by many factors, such as microenvironment pH, oncogenic transformation and stress response.59, 60, 61 The role of exosomes in HCC progression has been extensively studied. Exosomal miRNAs derived from HCC cell activate transforming growth factor‐β activated kinase‐1 (TAK1) and the downstream signalling molecules, resulting in further growth of recipient cells, indicating that exosomes have an ability to modulate receptor cell signalling and biological effects.30 In this part, we summarize the recent studies on the progress of HCC involving exosomes.

5.1. Exosomes participate in HCC chemoresistance

Sorafenib is the first‐line molecular targeted drug for advanced HCC approved by US Food and Drug Administration. However, after long‐term treatment of sorafenib, HCC cells exhibit resistance to sorafenib.62 Accumulating evidence has shown that exosomes are involved in HCC chemoresistance as well. Here, we summarize several possible mechanisms related to exosomes.

First, exosomes promote drug efflux to develop chemoresistance. Tumour cells can excrete anti‐cancer drugs and the metabolites by encapsulation in exosomes.63, 64 Takahashi et al showed that the expression of lincRNA‐LVVDL increased in HCC cells in the presence of diverse anti‐tumour agents including sorafenib. Altered expression of lincRNA‐LVVDL in cells is related to increased expression of ABCG2,47 a member of ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily involved in drug elimination of cancer cell.65, 66 Furthermore, overexpression of lincRNA‐LVVDL was also found in HCC cell‐derived exosomes, indicating that cancer cells maintain chemoresistance not only by eliminating chemodrug via exosomes but also by inducing molecular transfer.47

Second, exosomes participate in chemoresistance by enhancing the viability of tumour cells in the presence of chemo drugs. Qu et al67 for the first time showed that exosomes derived from HCC cells induce sorafenib resistance in hepatoma cells by inhibiting sorafenib‐induced apoptosis. The underlying mechanism is that HCC‐derived exosomes result in overexpression of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in hepatoma cells and lead to subsequent c‐Met phosphorylation68 and downstream signalling pathways such as PI3K/Akt and MAPK/Erk activation.69, 70, 71, 72 Takahashi et al also found that sorafenib increases the expression of linc‐ROR, a stress response long non‐coding RNA, in HCC cells. Intriguingly, linc‐ROR selectively enriched in exosomes in response to TGFβ that modulates chemotherapy‐induced apoptosis and allows cell survival under chemotherapeutic stress through p53 dependent manner.48

These results indicate that exosomal cargoes participate in chemical therapeutic response modulation and provide therapeutic targets that enhance the chemosensitivity of HCC cells.

5.2. Exosomes modulate epithelial‐mesenchymal transition of HCC cells

Epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) is an initial step in cancer distance metastasis.73, 74, 75 EMT defined as a process by which cell lose epithelial markers like E‐cadherin and acquire mesenchymal cell hallmarks like N‐cadherin.76, 77 EMT and the reverse process MET are the basis of the complex three‐dimensional structure of the internal organs.27 However, tumour cells achieve mobility and invasiveness through the EMT process, leading to cancer metastasis.73, 78 For example, it has been demonstrated that Hakai an E‐cadherin ubiquitination protein that mediates E‐cadherin ubiquitination and finally degradation plays a crucial role in EMT. It is considered to be a better therapeutic target than proteasome in the tumour subtypes.79 Exosomes provided a new research perspective for studying EMT. For example, it has been found that EMT reprogramming occurs in cancer cells after receiving miR‐223 from polymorphonuclear leucocyte‐derived exosomes.80 However, this impact of miR‐223 is transient because it is rapidly inactivated by the exonuclease XRN1, indicating that ectopic miRNAs and endogenous miRNAs act in different ways.80 In addition, MSC‐derived exosomes have been found to induce EMT in adjacent epithelial cells in many different cancers types.76, 77, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86

Taken together, these results support the notion that exosomes participate in EMT that associated with aggressive, invasive and metastatic potential in cancer cells. However, more research is needed to better understand the exact mechanism by which exosomes modulate EMT in HCC.

5.3. Exosomes promote angiogenesis in HCC tissue

It has been demonstrated that cancer cells undergoing EMT capable of efficiently transferring angiogenetic proteins to the recipient endothelial cell via exosomes.87 In addition, secretion of exosomes increased in HCC tissue under stringent conditions, such as deficiency of oxygen or nutrition, chemodrug stimulation and ethanol exposure. Among them, oxygen and nutrition deficiency are the main causes of angiogenesis.88 These results lead us to hypothesize that under stringent conditions, cancer cells transmit angiogenic molecules through exosomes to establish a tumour‐promoting microenvironment. In the study conducted by Gonzalez‐King showed that hypoxic MSCs‐derived exosomes induce angiogenesis by horizontally transferring Jagged‐1 and activating the downstream Notch pathway in endothelial cells.89 In another study, Sruthi found that HepG2 cells express a higher level of miR23a both in the cytoplasm and secreted exosomes under hypoxic conditions and the exosomal miR23a downregulates SIRT1 in recipient cells, thereby inducing angiogenesis.90

Interestingly, the increasing evidence suggested that a relationship between cancer stem cells (CSCs) and angiogenesis exists in tumour microenvironment, called “crosstalk” which synergistically promotes tumour growth.3, 4, 91, 92 For example, Conigliaro et al49 demonstrated that CD90+ CSC like liver cells could influence epithelial cells by transferring exosomes. The increased level of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production and tube formation was observed in epithelial cells after exosomes internalization. By identifying lncRNA profiling, they found that lncRNA H19 is enriched in CD90+ CSC like liver cell‐derived exosomes, and could be a major mediator of angiogenesis and the therapeutic target for HCC.49

In addition to the intracellular environment, exogenous stimuli such as ethanol exposure induce angiogenic endothelial phenotypes in multiple pathways.93, 94, 95, 96 Lamichhane et al97 reported that ethanol increases the vascularized bioactivity of endothelial cell‐derived EVs through downregulating anti‐angiogenic miRNA cargo (miR‐106b) and upregulating pro‐angiogenic long non‐coding RNA (lncRNA) cargo (MALAT1 and HOTAIR). Importantly, this might be one of the molecular mechanisms by which alcohol causes liver cancer.

5.4. Exosomes promote HCC metastasis

Long‐term survival rate is low in patients with HCC due to the high metastases and/or high post‐surgical recurrence rate.98 Tumour metastasis is a multistep process that includes invasion, intravasation and colonization of distal sites through the circulatory system.99 EMT, the initial step of metastasis, has been described above.

It has been found that exosomes facilitate the pre‐metastatic niche formation and metastasis, whether derived from cancer cells or adjacent stromal cells.26, 34, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105 The characteristic of promoting metastasis is based on the variation of exosomal cargo during tumour progression.3, 76, 106 Various oncogenic RNAs and proteins, such as MET protooncogene, caveolins, and S100 family members, have been found in motile HCC cell line‐derived exosomes by the full characterization of exosomal transcriptome and proteome.26 Internalization of these exosomes by hepatocytes activates PI3K/AKT and MAPK signalling pathway and increases matrix degrading proteases, MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 that are favourable for cell invasion.26 Furthermore, Zhang et al105 demonstrated that loss of miR‐320a in cancer associated fibroblast (CAF)‐derived exosomes in HCC leads to PBX dysregulation in recipient cells (hepatocyte) leading to lung metastasis. These results suggested that exosomes could mobilize normal hepatocyte to construct tumorigenic microenvironment, and consequently lead to metastasis.

5.5. Exosomes trigger immune responses

Immune tolerance, the unique immune microenvironment of the liver, is the main obstacle to immunotherapy for treating HCC.4

It is paradoxical that exosomes trigger immune response. On the one hand, exosomes are found in a variety of known immunosuppressive mechanisms, such as activation of immune suppressor cells, antigen presentation defects and induction of T‐cell apoptosis.107, 108 On the other hand, exosomes are a key source of tumour antigens exposed by tumour cells and immune cells.109

For example, Lv et al15 demonstrated that anti‐cancer drugs stimulate HCC‐derived exosomes secretion and generate more exosome‐carried HSPs, which known as “stress response” proteins. According to their study, HSP‐bearing exosomes stimulate potent anti‐tumour immune response through several mechanisms, including stimulation of NK cell cytotoxicity granzyme B production, up‐regulation of the expression of inhibitory receptor CD94 and downregulation of the expression of activating receptors CD69, NKG2D and NKp44.15

Rao et al compared the level of immune responses elicited by dendritic cells pulsed by HCC tumour cell‐derived exosomes (TEX) or cell lysates. Their study showed that increased numbers of T lymphocytes, increased expression of interferon‐γ, and decreased levels of interleukin‐10 and tumour growth factor‐β were observed in HCC mice treated with HCC TEX‐pulsed DCs, rather than treated with cell lysates‐pulse DCs.109 These results indicated that TEX‐carrying tumour associated antigens (TAAs) can be presented to DCs to initiate DC‐mediated immune responses.107, 109

Furthermore, Lu et al110 demonstrated that potent T‐cell activation was observed in HCC mice treated with HCC antigen‐modified DC (a‐fetoprotein [AFP]‐expressing DC)‐derived exosomes (DEXs). These findings demonstrated that exosomes not only present TAA from tumour cells to APCs but also are capable of presenting them to T lymphocytes that elicit an antigen‐mediated anti‐tumour immune response. This greatly promotes the development of HCC immunotherapy by providing cell‐free vaccines.

5.6. Exosomes are a promising agent for anti‐cancer therapy

Cell membrane‐derived nanoparticles have many properties, such as protecting their cargo, low immunogenicity and proper size through the endothelium,88 which can be used as drug delivery agents.111, 112, 113, 114 For example, Lou et al112 reported that adipose‐derived MSCs have full ability to transfer miR‐122 via exosomes, thereby sensitizing HCC cells to chemotherapeutic agents. It has been demonstrated that the miR‐122 negatively regulates the expression of the disintegrin and metalloproteinases family member 17 (ADAM17), ADAM10, IGF1R and MADS‐box transcription factor SRF113, 114 and is correlated with poor prognosis and metastasis in human HCC patient.113, 115

MSCs are widely used due to they are the most prolific producer of exosomes among the cell types.116 In addition to adipose‐derived MSCs,117 the bone marrow‐derived exosomes are commonly used in stem cell‐based therapies.86 Furthermore it has been reported that the DC‐derived exosomes are used as cancer vaccines.110, 118

Tian et al111 suggested that it may have a potential value for clinic application that modifying exosomes by targeting ligands which used for a drug delivery vesicle. For instance, modification of exosomes membrane with Arg‐Gly‐Asp (RGD) peptide elicits blood vessel targeting effect, which may be a new strategy for therapeutic angiogenesis.119

Meanwhile, exosomes have been reported to be involved in chemodrug resistance, and serveral studies indicated that inhibition of exosomes secretion has been shown to be effective in sensitize cancer cells to therapeutic drugs.8, 120

Overall, exosomes are promising agents for HCC treatment therapy.

6. CONCLUSION

Exosomes in cancer include HCC is a research hot spot over the past few years. In this review, the aim was to better understand the exosomes in HCC development. To the best of our knowledge, exosomes promote HCC progression by regulating multiple tumorigenic processes, including chemoresistance, EMT, angiogenesis, metastasis and immune response. An implication of this is the possibility that exosomes may be promising candidates for the treatment of HCC. It had been found that exosomes have several advantages as a drug delivery agent in the treatment of HCC. These findings had offered a framework for the exploration of new therapeutic tools for HCC. However, research is limited by the lack of information on the clinical safety and efficacy of exosomes. Therefor, further studies are still required to better understand the relationship between exosomes and HCC development.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81772995 and 81472266) and the Excellent Youth Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20140032). We apologize to all colleagues whose relevant contributions could not be cited due to space limitations.

Abudoureyimu M, Zhou H, Zhi Y, et al. Recent progress in the emerging role of exosome in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Prolif. 2019;52:e12541 10.1111/cpr.12541

REFERENCES

- 1. Morelli AE, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, et al. Endocytosis, intracellular sorting, and processing of exosomes by dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;104(10):3257‐3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saleem SN, Abdel‐Mageed AB. Tumor‐derived exosomes in oncogenic reprogramming and cancer progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(1):1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wu Z, Zeng Q, Cao K, Sun Y. Exosomes: small vesicles with big roles in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(37):60687‐60697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moris D, Beal EW, Chakedis J, et al. Role of exosomes in treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg Oncol. 2017;26(3):219‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou S, Abdouh M, Arena V, Arena M, Arena GO. Reprogramming malignant cancer cells toward a benign phenotype following exposure to human embryonic stem cell microenvironment. Plos One. 2017;12(1):e0169899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams C, Rodriguez‐Barrueco R, Silva JM, et al. Double‐stranded DNA in exosomes: a novel biomarker in cancer detection. Cell Res. 2014;24(6):766‐769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Farooqi AA, Desai NN, Qureshi MZ, et al. Exosome biogenesis, bioactivities and functions as new delivery systems of natural compounds. Biotechnol Adv. 2018;36(1):328‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhou L, Lv T, Zhang Q, et al. The biology, function and clinical implications of exosomes in lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017;407:84‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Henne WM, Buchkovich NJ, Emr SD. The ESCRT pathway. Dev Cell. 2011;21(1):77‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Raiborg C, Stenmark H. The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature. 2009;458(7237):445‐452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Babst M, Sato TK, Banta LM, Emr SD. Endosomal transport function in yeast requires a novel AAA‐type ATPase, Vps4p. Embo J. 1997;16(8):1820‐1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Han H, Monroe N, Votteler J, et al. Binding of substrates to the central pore of the Vps4 ATPase is autoinhibited by the microtubule interacting and trafficking (MIT) domain and activated by MIT interacting motifs (MIMs). J Biol Chem. 2015;290(21):13490‐13499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wei JX, Lv LH, Wan YL, et al. Vps4A functions as a tumor suppressor by regulating the secretion and uptake of exosomal microRNAs in human hepatoma cells. Hepatology. 2015;61(4):1284‐1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Juan T, Furthauer M. Biogenesis and function of ESCRT‐dependent extracellular vesicles. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;74:66‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lv LH, Wan YL, Lin Y, et al. Anticancer drugs cause release of exosomes with heat shock proteins from human hepatocellular carcinoma cells that elicit effective natural killer cell antitumor responses in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(19):15874‐15885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saha B, Momen‐Heravi F, Furi I, et al. Extracellular vesicles from mice with alcoholic liver disease carry a distinct protein cargo and induce macrophage activation via Hsp90. Hepatology. 2018;67(5):1986–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guescini M, Genedani S, Stocchi V, Agnati LF. Astrocytes and glioblastoma cells release exosomes carrying mtDNA. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2010;117(1):1‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Szabo G, Momen‐Heravi F. Extracellular vesicles in liver disease and potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat. 2017;14(8):455‐466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kahlert C, Kalluri R. Exosomes in tumor microenvironment influence cancer progression and metastasis. J Mol Med. 2013;91(4):431‐437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Al‐Nedawi K, Meehan B, Micallef J, et al. Intercellular transfer of the oncogenic receptor EGFRvIII by microvesicles derived from tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(5):619‐624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cho JA, Park H, Lim EH, Lee KW. Exosomes from breast cancer cells can convert adipose tissue‐derived mesenchymal stem cells into myofibroblast‐like cells. Int J Oncol. 2012;40(1):130‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jung T, Castellana D, Klingbeil P, et al. CD44v6 dependence of premetastatic niche preparation by exosomes. Neoplasia. 2009;11(10):1093‐1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tauro BJ, Mathias RA, Greening DW, et al. Oncogenic H‐ras reprograms Madin‐Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cell‐derived exosomal proteins following epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(8):2148‐2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lu J, Li J, Liu S, et al. Exosomal tetraspanins mediate cancer metastasis by altering host microenvironment. Oncotarget. 2017;8(37):62803‐62815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang J, Lu S, Zhou Y, et al. Motile hepatocellular carcinoma cells preferentially secret sugar metabolism regulatory proteins via exosomes. Proteomics. 2017;17(13‐14). 10.1002/pmic.201700103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. He M, Qin H, Poon TC, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma‐derived exosomes promote motility of immortalized hepatocyte through transfer of oncogenic proteins and RNAs. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36(9):1008‐1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dalla Pozza E, Forciniti S, Palmieri M, Dando I. Secreted molecules inducing epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition in cancer development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;78:62‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu C, Yang Y, Wu Y. Recent advances in exosomal protein detection via liquid biopsy biosensors for cancer screening, diagnosis, and prognosis. Aaps J. 2018;20(2):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li L, Tang J, Zhang B, et al. Epigenetic modification of MiR‐429 promotes liver tumour‐initiating cell properties by targeting Rb binding protein 4. Gut. 2014;64(1):156‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kogure T, Lin W, Yan IK, Braconi C, Patel T. Intercellular nanovesicle‐mediated microRNA transfer: a mechanism of environmental modulation of hepatocellular cancer cell growth. Hepatology. 2011;54(4):1237‐1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sohn W, Kim J, Kang SH, et al. Serum exosomal microRNAs as novel biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sugimachi K, Matsumura T, Hirata H, et al. Identification of a bona fide microRNA biomarker in serum exosomes that predicts hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(3):532‐538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu W, Hu J, Zhou K, et al. Serum exosomal miR‐125b is a novel prognostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:3843‐3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu WH, Ren LN, Wang X, et al. Combination of exosomes and circulating microRNAs may serve as a promising tumor marker complementary to alpha‐fetoprotein for early‐stage hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis in rats. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141(10):1767‐1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hung CS, Liu HH, Liu JJ, et al. MicroRNA‐200a and ‐200b mediated hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration through the epithelial to mesenchymal transition markers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(Suppl 3):S360‐S368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Petrelli A, Perra A, Cora D, et al. MicroRNA/gene profiling unveils early molecular changes and nuclear factor erythroid related factor 2 (NRF2) activation in a rat model recapitulating human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Hepatology. 2014;59(1):228‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yeh TS, Wang F, Chen TC, et al. Expression profile of microRNA‐200 family in hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombus. Ann Surg. 2014;259(2):346‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yuan JH, Yang F, Chen BF, et al. The histone deacetylase 4/SP1/microrna‐200a regulatory network contributes to aberrant histone acetylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54(6):2025‐2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qi P, Cheng SQ, Wang H, et al. Serum microRNAs as biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Plos One. 2011;6(12):e28486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang H, Hou L, Li A, et al. Expression of serum exosomal microRNA‐21 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu J, Wu C, Che X, et al. Circulating microRNAs, miR‐21, miR‐122, and miR‐223, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma or chronic hepatitis. Mol Carcinog. 2011;50(2):136‐142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fornari F, Ferracin M, Trere D, et al. Circulating microRNAs, miR‐939, miR‐595, miR‐519d and miR‐494, identify cirrhotic patients with HCC. Plos One. 2015;10(10):e0141448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ariel I, Miao HQ, Ji XR, et al. Imprinted H19 oncofetal RNA is a candidate tumour marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Pathol. 1998;51(1):21‐25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin R, Maeda S, Liu C, Karin M, Edgington TS. A large noncoding RNA is a marker for murine hepatocellular carcinomas and a spectrum of human carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26(6):851‐858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Panzitt K, Tschernatsch MM, Guelly C, et al. Characterization of HULC, a novel gene with striking up‐regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma, as noncoding RNA. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):330‐342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yang F, Zhang L, Huo XS, et al. Long noncoding RNA high expression in hepatocellular carcinoma facilitates tumor growth through enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in humans. Hepatology. 2011;54(5):1679‐1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Takahashi K, Yan IK, Wood J, Haga H, Patel T. Involvement of extracellular vesicle long noncoding RNA (linc‐VLDLR) in tumor cell responses to chemotherapy. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12(10):1377‐1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Takahashi K, Yan IK, Kogure T, Haga H, Patel T. Extracellular vesicle‐mediated transfer of long non‐coding RNA ROR modulates chemosensitivity in human hepatocellular cancer. Febs Open Bio. 2014;4(1):458‐467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Conigliaro A, Costa V, Lo Dico A et al. CD90+ liver cancer cells modulate endothelial cell phenotype through the release of exosomes containing H19 lncRNA. Mol Cancer. 2015;14(1):155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Braconi C, Valeri N, Kogure T, et al. Expression and functional role of a transcribed noncoding RNA with an ultraconserved element in hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(2):786‐791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kogure T, Yan IK, Lin WL, Patel T. Extracellular vesicle‐mediated transfer of a novel long noncoding RNA TUC339: a mechanism of intercellular signaling in human hepatocellular cancer. Genes Cancer. 2013;4(7–8):261‐272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang X, Yuan X, Shi H, et al. Exosomes in cancer: small particle, big player. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schneider DJ, Speth JM, Penke LR, et al. Mechanisms and modulation of microvesicle uptake in a model of alveolar cell communication. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(51):20897‐20910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hoshino A, Costa‐Silva B, Shen TL, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527(7578):329‐335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Watson DC, Bayik D, Srivatsan A, et al. Efficient production and enhanced tumor delivery of engineered extracellular vesicles. Biomaterials. 2016;105:195‐205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Muller L, Simms P, Hong CS, et al. Human tumor‐derived exosomes (TEX) regulate Treg functions via cell surface signaling rather than uptake mechanisms. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(8):e1261243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Abdouh M, Hamam D, Gao ZH, et al. Exosomes isolated from cancer patients' sera transfer malignant traits and confer the same phenotype of primary tumors to oncosuppressor‐mutated cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36(1):113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hamam D, Abdouh M, Gao Z, et al. Transfer of malignant trait to BRCA1 deficient human fibroblasts following exposure to serum of cancer patients. J Exp Clin Canc Res. 2016;35(1):80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Parolini I, Federici C, Raggi C, et al. Microenvironmental pH is a key factor for exosome traffic in tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(49):34211‐34222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Choi D, Lee TH, Spinelli C, et al. Extracellular vesicle communication pathways as regulatory targets of oncogenic transformation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;67:11‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yoshida M, Yamashita T, Okada H, et al. Sorafenib suppresses extrahepatic metastasis de novo in hepatocellular carcinoma through inhibition of mesenchymal cancer stem cells characterized by the expression of CD90. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dong J, Zhai B, Sun W, et al. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase/AKT/snail signaling pathway contributes to epithelial‐mesenchymal transition‐induced multi‐drug resistance to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Plos One. 2017;12(9):e0185088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shedden K, Xie XT, Chandaroy P, Chang YT, Rosania GR. Expulsion of small molecules in vesicles shed by cancer cells: association with gene expression and chemosensitivity profiles. Cancer Res. 2003;63(15):4331‐4337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Safaei R, Larson BJ, Cheng TC, et al. Abnormal lysosomal trafficking and enhanced exosomal export of cisplatin in drug‐resistant human ovarian carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4(10):1595‐1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dean M, Hamon Y, Chimini G. The human ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. J Lipid Res. 2001;42(7):1007‐1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sukowati CH, Rosso N, Pascut D, et al. Gene and functional up‐regulation of the BCRP/ABCG2 transporter in hepatocellular carcinoma. Bmc Gastroenterol. 2012;12:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Qu Z, Wu J, Wu J, et al. Exosomes derived from HCC cells induce sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma both in vivo and in vitro. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35(1):159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. You H, Ding W, Dang H, Jiang Y, Rountree CB. c‐Met represents a potential therapeutic target for personalized treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54(3):879‐889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ma PC, Maulik G, Christensen J, Salgia R. c‐Met: structure, functions and potential for therapeutic inhibition. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22(4):309‐325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Graziani A, Gramaglia D, Cantley LC, Comoglio PM. The tyrosine‐phosphorylated hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor receptor associates with phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(33):22087‐22090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ponzetto C, Bardelli A, Zhen Z, et al. A multifunctional docking site mediates signaling and transformation by the hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor receptor family. Cell. 1994;77(2):261‐271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Fixman ED, Naujokas MA, Rodrigues GA, Moran MF, Park M. Efficient cell transformation by the Tpr‐Met oncoprotein is dependent upon tyrosine 489 in the carboxy‐terminus. Oncogene. 1995;10(2):237‐249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Thiery JP. Epithelial‐mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(6):442‐454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gopal SK, Greening DW, Rai A, et al. Extracellular vesicles: their role in cancer biology and epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. Biochem J. 2017;474(1):21‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Markopoulos GS, Roupakia E, Tokamani M, et al. A step‐by‐step microRNA guide to cancer development and metastasis. Cell Oncol. 2017;40(4):303‐339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Greening DW, Gopal SK, Mathias RA, et al. Emerging roles of exosomes during epithelial‐mesenchymal transition and cancer progression. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;40:60‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Blackwell R, Foreman K, Gupta G. The role of cancer‐derived exosomes in tumorigenicity & epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition. Cancers. 2017;9(8):105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dos Anjos Pultz B, Andrés Cordero da Luz F, Socorro Faria S, et al. The multifaceted role of extracellular vesicles in metastasis: priming the soil for seeding. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(11):2397‐2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Díaz‐Díaz A, Casas‐Pais A, Calamia V, et al. Proteomic analysis of the E3 ubiquitin‐ligase hakai highlights a role in plasticity of the cytoskeleton dynamics and in the proteasome system. J Proteome Res. 2017;16(8):2773‐2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zangari J, Ilie M, Rouaud F, et al. Rapid decay of engulfed extracellular miRNA by XRN1 exonuclease promotes transient epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(7):4131‐4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Aga M, Bentz GL, Raffa S, et al. Exosomal HIF1alpha supports invasive potential of nasopharyngeal carcinoma‐associated LMP1‐positive exosomes. Oncogene. 2014;33(37):4613‐4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Greening DW, Xu R, Ji H, Tauro BJ, Simpson RJ. A protocol for exosome isolation and characterization: evaluation of ultracentrifugation, density‐gradient separation, and immunoaffinity capture methods. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1295:179‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Qin W, Tsukasaki Y, Dasgupta S, et al. Exosomes in human breast milk promote EMT. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(17):4517‐4524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Xiao D, Barry S, Kmetz D, et al. Melanoma cell‐derived exosomes promote epithelial‐mesenchymal transition in primary melanocytes through paracrine/autocrine signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2016;376(2):318‐327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Vallabhaneni KC, Penfornis P, Dhule S, et al. Extracellular vesicles from bone marrow mesenchymal stem/stromal cells transport tumor regulatory microRNA, proteins, and metabolites. Oncotarget. 2015;6(7):4953‐4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bruno S, Collino F, Deregibus MC, et al. Microvesicles derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit tumor growth. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(5):758‐771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Gopal SK, Greening DW, Hanssen EG, et al. Oncogenic epithelial cell‐derived exosomes containing Rac1 and PAK2 induce angiogenesis in recipient endothelial cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7(15):19709‐19722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zhang X, Ng H, Lu A, et al. Drug delivery system targeting advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: current and future. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2016;12(4):853‐869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gonzalez‐King H, Garcia NA, Ontoria‐Oviedo I, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor‐1alpha potentiates jagged 1‐mediated angiogenesis by mesenchymal stem cell‐derived exosomes. Stem Cells. 2017;35(7):1747‐1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sruthi TV, Edatt L, Raji GR, et al. Horizontal transfer of miR‐23a from hypoxic tumor cell colonies can induce angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(4):3498‐3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yao H, Liu N, Lin MC, Zheng J. Positive feedback loop between cancer stem cells and angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2016;379(2):213‐219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Yang XR, Xu Y, Yu B, et al. High expression levels of putative hepatic stem/progenitor cell biomarkers related to tumour angiogenesis and poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2010;59(7):953‐962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Morrow D, Cullen JP, Cahill PA, Redmond EM. Ethanol stimulates endothelial cell angiogenic activity via a Notch‐ and angiopoietin‐1‐dependent pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79(2):313‐321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Wang L, Son YO, Ding S, et al. Ethanol enhances tumor angiogenesis in vitro induced by low‐dose arsenic in colon cancer cells through hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 alpha pathway. Toxicol Sci. 2012;130(2):269‐280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 95. Wang S, Xu M, Li F, et al. Ethanol promotes mammary tumor growth and angiogenesis: the involvement of chemoattractant factor MCP‐1. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(3):1037‐1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Lu Y, Ni F, Xu M, et al. Alcohol promotes mammary tumor growth through activation of VEGF‐dependent tumor angiogenesis. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(2):673‐678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Lamichhane TN, Leung CA, Douti LY, Jay SM. Ethanol induces enhanced vascularization bioactivity of endothelial cell‐derived extracellular vesicles via regulation of microRNAs and long non‐coding RNAs. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Tang ZY, Ye SL, Liu YK, et al. A decade's studies on metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130(4):187‐196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. van Zijl F, Krupitza G, Mikulits W. Initial steps of metastasis: cell invasion and endothelial transmigration. Mutat Res. 2011;728(1–2):23‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zhang H, Deng T, Liu R, et al. Exosome‐delivered EGFR regulates liver microenvironment to promote gastric cancer liver metastasis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Yu Z, Zhao S, Ren L, et al. Pancreatic cancer‐derived exosomes promote tumor metastasis and liver pre‐metastatic niche formation. Oncotarget. 2017;8(38):63461‐63483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Plebanek MP, Angeloni NL, Vinokour E, et al. Pre‐metastatic cancer exosomes induce immune surveillance by patrolling monocytes at the metastatic niche. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Li L, Li C, Wang S, et al. Exosomes derived from hypoxic oral squamous cell carcinoma cells deliver miR‐21 to normoxic cells to elicit a prometastatic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2016;76(7):1770‐1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Sharma A. Role of stem cell derived exosomes in tumor biology. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(6):1086‐1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Zhang Z, Li X, Sun W, et al. Loss of exosomal miR‐320a from cancer‐associated fibroblasts contributes to HCC proliferation and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2017;397:33‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Park JE, Tan HS, Datta A, et al. Hypoxic tumor cell modulates its microenvironment to enhance angiogenic and metastatic potential by secretion of proteins and exosomes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9(6):1085‐1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Czernek L, Düchler M. Functions of cancer‐derived extracellular vesicles in immunosuppression. Arch Immunol Ther Ex. 2017;65(4):311‐323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Sullivan R, Maresh G, Zhang X, et al. The emerging roles of extracellular vesicles as communication vehicles within the tumor microenvironment and beyond. Front Endocrinol. 2017;8:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Rao Q, Zuo B, Lu Z, et al. Tumor‐derived exosomes elicit tumor suppression in murine hepatocellular carcinoma models and humans in vitro. Hepatology. 2016;64(2):456‐472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Lu Z, Zuo B, Jing R, et al. Dendritic cell‐derived exosomes elicit tumor regression in autochthonous hepatocellular carcinoma mouse models. J Hepatol. 2017;67(4):739‐748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Tian Y, Li S, Song J, et al. A doxorubicin delivery platform using engineered natural membrane vesicle exosomes for targeted tumor therapy. Biomaterials. 2014;35(7):2383‐2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Lou G, Song X, Yang F, et al. Exosomes derived from miR‐122‐modified adipose tissue‐derived MSCs increase chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Tsai WC, Hsu PW, Lai TC, et al. MicroRNA‐122, a tumor suppressor microRNA that regulates intrahepatic metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2009;49(5):1571‐1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Bai S, Nasser MW, Wang B, et al. MicroRNA‐122 inhibits tumorigenic properties of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and sensitizes these cells to sorafenib. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(46):32015‐32027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Coulouarn C, Factor VM, Andersen JB, Durkin ME, Thorgeirsson SS. Loss of miR‐122 expression in liver cancer correlates with suppression of the hepatic phenotype and gain of metastatic properties. Oncogene. 2009;28(40):3526‐3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Yeo RW, Lai RC, Zhang B, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell: an efficient mass producer of exosomes for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(3):336‐341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ko SF, Yip HK, Zhen YY, et al. Adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cell exosomes suppress hepatocellular carcinoma growth in a rat model: apparent diffusion coefficient, natural killer T‐cell responses, and histopathological features. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015:853506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Yang N, Li S, Li G, et al. The role of extracellular vesicles in mediating progression, metastasis and potential treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(2):3683‐3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Wang J, Li W, Lu Z, et al. The use of RGD‐engineered exosomes for enhanced targeting ability and synergistic therapy toward angiogenesis. Nanoscale. 2017;9(40):15598‐15605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Li XQ, Liu JT, Fan LL, et al. Exosomes derived from gefitinib‐treated EGFR‐mutant lung cancer cells alter cisplatin sensitivity via up‐regulating autophagy. Oncotarget. 2016;7(17):24585‐24595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]