Abstract

Abstract. Evidence is growing in support of the role of stem cells as an attractive alternative in treatment of liver diseases. Recently, we have demonstrated the feasibility and safety of infusing CD34+ adult stem cells; this was performed on five patients with chronic liver disease. Here, we present the results of long‐term follow‐up of these patients. Between 1 × 106 and 2 × 108 CD34+ cells were isolated and injected into the portal vein or hepatic artery. The patients were monitored for side effects, toxicity and changes in clinical, haematological and biochemical parameters; they were followed up for 12–18 months. All patients tolerated the treatment protocol well without any complications or side effects related to the procedure, also there were no side effects noted on long‐term follow‐up. Four patients showed an initial improvement in serum bilirubin level, which was maintained for up to 6 months. There was marginal increase in serum bilirubin in three of the patients at 12 months, while the fourth patient's serum bilirubin increased only at 18 months post‐infusion. Computed tomography scan and serum α‐foetoprotein monitoring showed absence of focal lesions. The study indicated that the stem cell product used was safe in the short and over long term, by absence of tumour formation. The investigation also illustrated that the beneficial effect seemed to last for around 12 months. This trial shows that stem cell therapy may have potential as a possible future therapeutic protocol in liver regeneration.

INTRODUCTION

Orthotopic liver transplantation is the only definitive therapeutic option available for patients with chronic end‐stage liver disease. However, a shortage of suitable donor organs and requirement for immunosuppression restrict its usage, highlighting the need to find suitable alternatives. In the past few years, multiple studies have demonstrated that adult stem cell plasticity is far greater and complex than previously thought, raising expectations that it could lay the foundations for new cellular therapies in regenerative medicine. Haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are most widely studied example of adult sources – they sustain formation of blood and immune systems cells throughout normal life. These cells are capable of differentiating into many types of other tissues, including skeletal and cardiac muscle, endothelium, and a variety of epithelia including neuronal cells, pneumocytes and hepatocytes (Preston et al. 2003).

Haematopoietic stem cells have been used for haematological reconstitution for many years (Thomas 2005). The observation by Alison et al. (2000) and Theise et al. (2000a), that hepatocytes could also be derived from bone marrow cell populations, and further advances in the understanding of HSC plasticity, have formed the basis for recent clinical trials where these cells have been used for transplantation in patients with liver disease (Terai et al. 2006). The mechanism by which extrahepatic stem cells regenerate the liver is not yet resolved and transdifferentiation of stem cells into hepatocytes or fusion of haematopoietic cells with existing hepatocytes have been suggested as explanation. Terada et al. (2002) showed that bone marrow cells can fuse with embryonic stem cells and adopt a phenotype of recipient cells in cell culture, suggesting that the plasticity of bone marrow cells is a consequence of fusion of bone marrow‐derived cells with endogenous hepatocytes. This was confirmed by Wang et al. (2003) and Vassilopoulos et al. (2003). We have conducted a phase I clinical trial of infusion of autologous, mobilized CD34+ cells into the portal vein or hepatic artery of five patients with chronic liver disease, with no immediate adverse effects (Gordon et al. 2006). Here, we present long‐term follow‐up data from these five patients noting any changes in liver function, development of late toxicity, or complications, and to exclude tumour formation following this protocol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

Patients were recruited with approval of the local ethics committee (LCER No. 2004/6746) and according to criteria determined by the Multidisciplinary Treatment committee of the Hammersmith Hospital, Imperial College London, UK. Informed written consent was obtained in all cases. Inclusion criteria were: male or female aged from 20 to 65 years; chronic liver failure; abnormal serum albumin and/or bilirubin and/or prothrombin time; unsuitable for liver transplantation; World Health Organization performance status < 2; women of childbearing potential using reliable and appropriate contraception; life expectancy of at least 3 months; and ability to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: patients aged below 20 years or over 65 years; liver tumours present, or history of other cancer; pregnant or lactating women; recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; evidence of active infection including human immunodeficiency virus; and inability to provide informed consent.

Pre‐treatment assessment

Prospective patients were admitted to the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery at the Hammersmith Hospital. Full physical examination and World Health Organization performance scoring was performed. Following this, intravenous blood was taken for liver function tests, full blood count, coagulation profile, urea and electrolyte status, human immunodeficiency virus serology and α‐foetoprotein (AFP) levels. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and ultrasound with duplex Doppler investigation were performed to assess disease in the liver and portal system. Patients were then discharged pending discussion by the Multidisciplinary Treatment committee concerning their suitability for inclusion in the study.

CD34+ cell mobilization and harvesting

Patients included in the study were admitted to the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery Surgery. Each received a subcutaneous injection of 526 µg of granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor (G‐CSF, Chugai Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan) daily for 5 days to increase the number of circulating CD34+ cells in their systems. Any symptoms or signs of adverse reaction were appraised and recorded. Leukophoresis (Cobe Spectra IV, Cobe‐BCT Inc., Lakewood, CO, USA) was performed in the Department of Haematology on day 5. The leukophoresis product was transferred to the Stem Cell Laboratory where CD34+ cells were immunoselected immediately using the CliniMACS device (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch‐Gladbach, Germany).

CD34+ cell isolation

Leucocytes obtained were diluted in 1 : 4 in Hanks’ buffered saline solution (HBSS, Gibco, Paisley, UK), before the mononuclear cells (MNC) were separated, by centrifugation over a Lymphoprep (Axis‐Shield, Kimbolten, UK) density gradient at 750 g for 30 min (Heraeus, Herts, UK). The MNC fraction was collected and was washed first in HBSS, then with MACS buffer (phosphate‐buffered saline supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 5 mm EDTA, pH 7.20). CD34+ cells were isolated from the MNC using the CD34+ cell isolation kit (CliniMACS, Miltenyi Biotech).

CD34+ cell infusion

Isolated CD34+ cells were collected and their viability was checked. On the day of treatment, patients were provided with 1 × 106–2 × 108 CD34+ cells as a single bolus. These were suspended in 20 mL normal saline and each dose was returned to the appropriate same patient via the portal vein or the hepatic artery, observed using specialized imaging techniques, in the Imaging Department of the hospital.

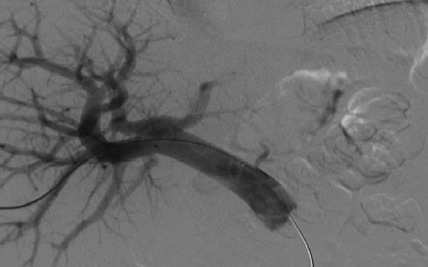

Portal venous infusion

A portal venogram was performed by percutaneous liver puncture under ultrasound guidance. Infusion of CD34+ cells was performed slowly through a transhepatic portal venous 5F angiographic catheter (Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL, USA) by hand injection (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Infusion of CD34+ cells into the portal vein.

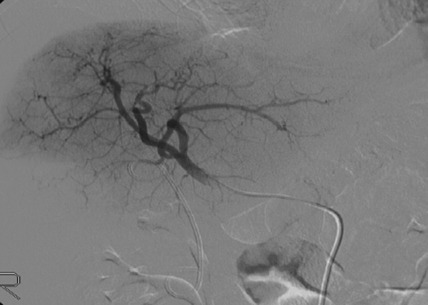

Hepatic artery infusion

Visceral angiography was performed via the right femoral artery and the CD34+ cells were infused slowly into 3F coaxial angiographic catheters (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) placed in the hepatic artery (Fig. 2). Continuous monitoring was performed through the leukophoresis as well as the infusion procedure and any haemodynamic changes were recorded. Patients were discharged after overnight bed rest.

Figure 2.

Infusion of CD34+ cells into the hepatic artery.

Follow‐up

Patients returned to the outpatient clinic on days 7, 15, 45 and 60 after infusion, for physical examination and blood testing, including liver function tests, full blood count, urea and electrolyte, and coagulation profile. In addition, on day 60, AFP assay and CT scan of the abdomen was performed. After completion of a 2‐month trial period, patients were followed‐up every further 2 months.

RESULTS

Five patients, four men and one woman aged 49–61 (mean 49) years, were recruited for the study and underwent the entire procedure. In three patients, the cells were injected into the portal vein under CT scan and in two patients they were injected via the hepatic artery. Aetiology, diagnosis, results of investigations, cell concentrations and post‐infusion observations for each patient are shown in 1, 2, 3.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||||

| Age (year)/gender | 42/Male | 48/Male | 41/Male | 55/Female | 61/Male |

| Diagnosis | Hepatitis B cirrhosis | Alcoholic cirrhosis | Hepatitis C cirrhosis | Hepatitis C and alcoholic cirrhosis | Primary sclerosing cholangitis with cirrhosis |

| Ascites | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Child‐Pugh score | A | B | A | B | B |

| Portal vein | Patent | Patent | Patent | Patent | Patent |

Table 2.

CD34+ stem cell concentrations and injection routes

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose of CD34+ cells infused (cells/kg) | 1 × 106 | 2 × 108 | 1 × 106 | 2 × 108 | 1 × 106 |

| Route of infusion | Portal vein | Portal vein | Portal vein | Hepatic artery | Hepatic artery |

Table 3.

Post‐injection side effects

| Post‐infusion side effects | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Pain at infusion site | 4 |

| Nausea | 5 |

| Fever | 1 |

| Vomiting | 1 |

| Rash | 1 |

| Bleeding | None |

| Liver failure | None |

Following G‐CSF treatment, increased total white cell counts indicated mobilization of progenitor cells in all patients. All patients experienced thrombocytopaenia as expected following leukophoresis, but platelet counts returned to baseline within 1 week. The patients had been given 1 × 106–2 × 108 CD34+ cells as a single bolus. Neither mortality nor specific side effects (except for mild pain and discomfort at the site of CD34+ cell infusion), were recorded. In particular, there was no bleeding and infection of significant deterioration in liver function. CT scans showed no evidence of focal liver lesions in any patient either before or after treatment and the duplex Doppler ultrasound scans showed patent portal veins with hepatopedal flow.

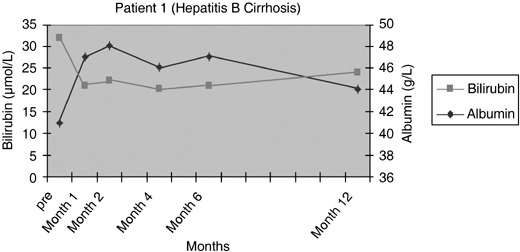

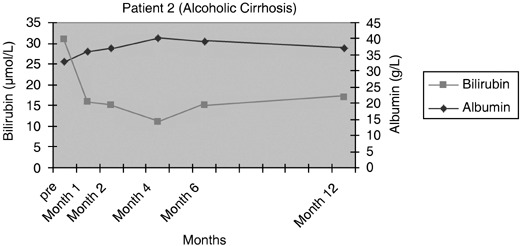

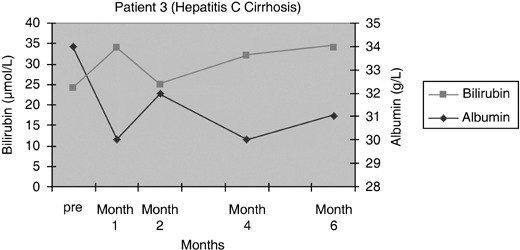

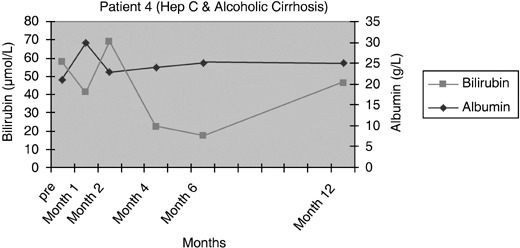

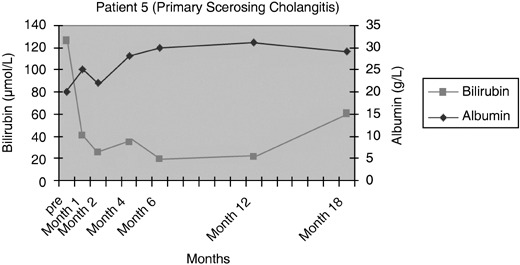

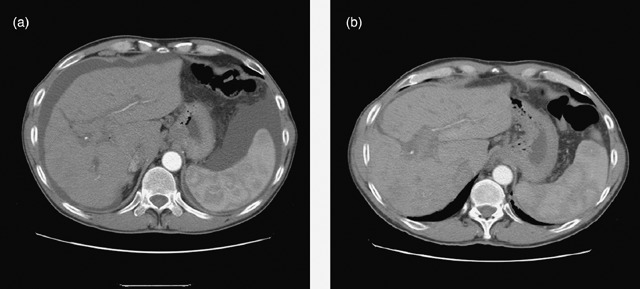

Patients 1 and 2 had initial improvement in serum bilirubin from pre‐infusion levels to normal, in the first 2 months after CD34+ cell infusion. This increased marginally at 6 months and remained so for rest of the follow‐up period in patient 1 (Fig. 3), while it remained within the normal range for 12 months in the follow‐up of patient 2 (Fig. 4). In patient 3, there was no change in serum bilirubin post‐CD34+ cell infusion during the study period of 2 months and it remained unchanged for 6 months of follow‐up (Fig. 5); this patient voluntarily opted out of further follow‐up. The progress of patient 4 was interrupted due to a severe urinary tract infection that necessitated hospitalization and treatment with antibiotics; at 6 months, follow‐up serum bilirubin had improved and was less than 50% of the pre‐infusion level. However, this reverted back to pre‐infusion levels by 12 months (Fig. 6). There was dramatic improvement in serum bilirubin (126–25 µmol/L) in patient 5, which remained unchanged up to 12 months post‐infusion. However, this had increased to 60 µmol/L by 18 months (Fig. 7). This patient also had complete resolution of ascites as shown in Fig. 8 and has remained free of ascites at 18 months. All patients except one (patient 4) had marginal increases in serum albumin levels that remained unchanged on further follow‐up. Serum AFP remained within the normal range through out the follow‐up period and upon imaging, none of the patients had developed any focal liver lesions.

Figure 3.

Serum bilirubin and albumin levels pre and post infusion of CD34+ cells in patient 1.

Figure 4.

Serum bilirubin and albumin levels pre and post infusion of CD34+ cells in patient 2.

Figure 5.

Serum bilirubin and albumin levels pre and post infusion of CD34+ cells in patient 3.

Figure 6.

Serum bilirubin and albumin levels pre and post infusion of CD34+ cells in patient 4.

Figure 7.

Serum bilirubin and albumin levels pre and post infusion of CD34+ cells in patient 5.

Figure 8.

Abdominal CT scan of patient 5 showing marked decrease in ascites pre cell infusion (a) and 60 days after cell infusion (b).

DISCUSSION

Due to the shortage of organ donors, only a small proportion of patients with liver failure are fortunate enough to undergo liver transplantation. Adult stem cell therapy could solve this problem as recent evidence shows that stem cells, particularly those in haematopoietic tissue, have the ability to develop into cells of all the three embryonic lineages (Preston et al. 2003).

Clinical studies on therapeutic application of bone marrow stem cells has demonstrated that CD34+ cells transplanted into ischaemic myocardium, incorporate into foci of neovascularization and have a favourable impact on cardiac function (Kawamoto et al. 2003). am Esch et al. (2005) have shown that the intraportal administration of autologous bone marrow stem cells to patients following partial hepatectomy, resulted in a 2.5‐fold increase in mean proliferation rates of cells in left lateral liver segments compared to a group of patients treated without the application of bone marrow stem cells. Terai et al. (2006) have recently shown improvement in serum albumin and total protein levels as well as Child‐Pugh score, following autologous bone marrow cell infusion into the peripheral vein.

The mechanism by which HSCs contribute to hepatocyte regeneration or to liver repair is unclear. However, understanding it will enable us to tailor stem cell therapy to the disease. Transdifferentiation into hepatocytes represents genomic plasticity in response to the microenvironment and has been shown in several experiments in vivo (Krause et al. 2001; Terai et al. 2003; Jang et al. 2004). However, some authors have proposed that conversion to hepatocytes may occur via cell fusion (Vassilopoulos et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2003). Both these processes may help in the regeneration of normal cells in the damaged organ. Finally, HSCs may stimulate tissue specific stem cells, for example oval cells in liver, and thus facilitate regeneration of the target organ.

Different subpopulations of stem cells may have different levels of functional plasticity but CD34+ is promising as a selection marker for bone marrow stem cells. Although initial studies mainly used unfractionated bone marrow, subsequent work has highlighted the capacity of CD34+ cells for hepatic engraftment (Theise et al. 2000a). In human, experiments with G‐CSF‐mobilized CD34+ cells have shown that these cells are able to transdifferentiate into hepatocytes, with 4–7% of hepatocytes in female livers being Y chromosome positive after a bone marrow transplant from a male donor (Korbling et al. 2002). The mechanism of homing of cells to the liver remains speculative. Damaged liver is known to express chemokines and possible chemotactants, which presumably participate in the process of stem cell homing from extrahepatic sources, to the liver (Hatch et al. 2002).

An increasing body of evidence suggests that liver injury induces expression and secretion of various factors, such as stromal‐derived factor‐1 (SDF‐1), inteleukin‐8, matrix metalloproteases, stem cell factor and hepatocyte growth factor, which facilitate homing and engraftment of HSC to the damaged liver (Dalakas et al. 2005). SDF‐1 and its receptor CXCR‐4 play the key role in migration of human progenitor cells to the liver (Kollet et al. 2003) and hepatocyte growth factor, which is increased following liver injury (Armbrust et al. 2002), increases motility of CD34+ cells to SDF‐1 signalling by inducing CXCR‐4 up‐regulation and synergizing with stem cell factor. Matrix metalloprotease‐9 enhances the release of HSC by degrading SDF‐1 (Petit et al. 2002) in bone marrow and by facilitating migration of stem cells through basement membranes and therefore helping to recruit HSC to the liver. In our approach, to improve hepatic homing, CD34+ cells were injected into the portal vein or hepatic artery and no procedural complications occurred.

Our phase I clinical study demonstrated the feasibility and safety of administering G‐CSF followed by leukaphoresis, and re‐infusion of CD34+ cells in patients with liver insufficiency. It is important to note that the patients could respond to G‐CSF treatment and that their white cell counts were increased in all cases, as this is a pre‐requisite for the remainder of the treatment protocol. However, CD34+ cell yields (1 × 106–2 × 108) were lower than those expected compared to donors for haematology patients. Typical yields of cells, obtained in our institution from donors for haematology patients, range from 5 to 10 × 1010, of which most are MNCs, and approximately 1% are CD34+ (5–10 × 108). Clinically, the procedure was well tolerated with no observed procedure‐related complications. There were no cases of hepatorenal syndrome and injection of the CD34+ cells into the hepatic artery or portal vein did not result in any thrombotic episode or bleeding, following the percutaneous procedure. Importantly, there was some evidence of improvement in albumin and bilirubin levels, even though the trial was designed to be a safety and feasibility study. We have noticed that improvement in albumin and billirubin levels did not correlate with the number of infused cells, and in case of billirubin, it improved to approximately the upper normal limit (17 µm). However, on long‐term follow‐up, serum bilirubin had gradually increased towards pre‐infusion levels after an initial improvement, in three of the four patients who had shown response. Besides albumin and billirubin, we also measured liver enzymes alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase. Both enzymes were slightly elevated before the treatment and stayed at the pre‐infusion levels after cell transplantation. All three patients had ongoing underlying liver disease in the form of primary sclerosing cholangitis and hepatitis B and C with low viral load (< 2 million copies/mL). The inability to maintain the initial response in these three patients could be due to ongoing disease processes, affecting the regenerated hepatocytes, over a longer period. This could also explain continued response in the fourth patient who had suffered from alcoholic cirrhosis and had continued to abstain from alcohol post‐infusion of CD34+ cells. In order to maintain benefit of such therapies, it will be important in the future to treat the histologically apparent disease, such as viral hepatitis, or to make the OmniCyte resistant to viral infection or to repeat the injection at intervals as has been done in some cardiac studies.

Other possible improvements in function would be facilitating the release of vascular endothelial growth factor by stem cells, thereby increasing the blood supply to the cells and thus helping to repair the damaged tissue (Rehman et al. 2004; Tang et al. 2006). Stem cells may act by up‐regulating the Bcl‐2 gene and therefore suppressing apoptosis (Chen et al. 2001; Rehman et al. 2004) and by suppressing inflammation in the diseased organ via the interleukin‐6 pathway (Wang et al. 2006). Both these processes may help in regeneration of normal cells in the damaged organ.

Advances in stem cell biology will have a profound impact on the future practice of medicine; the impact will likely be in specific areas that are currently in rapid evolution. These areas include cellular and organ transplantation. The idea that adult stem cells could be implicated in the treatment of end stage chronic liver disease is an exciting one and the results of the study above are encouraging. However, only a randomized clinical trial with more patients will further assess the safety, potential clinical benefit and a future for development of adult stem cell therapy for patients with liver insufficiency.

DISCLOSURES

M.Y.G., N.A.H. and J.P.N. own stock in OmniCyte Limited.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the medical and nursing staff who were involved in the care of the patients in this trial.

N. A. Habib, J. P. Nicholls and M. Y. Gordon have shares in OmniCyte Ltd. All remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Alison MR, Poulsom R, Jeffrey R, Dhillon AP, Quaglia A, Jacob J, Novelli M, Prentice G, Williamson J, Wright NA (2000) Hepatocytes from non‐hepatic stem cells. Nature 405, 257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbrust T, Batusic D, Xia L, Ramadori G (2002) Early gene expression of hepatocyte growth factor in mononuclear phagocytes of rat liver after administration of carbon tetrachloride. Liver 22, 486–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Chua CC, Ho YS, Hamdy RC, Chua BH (2001) Overexpression of Bcl‐2 attenuates apoptosis and protects against myocardial I/R injury in transgenic mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 280, H2313–H2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalakas E, Newsome PN, Harrison DJ, Plevris JN (2005) Hematopoietic stem cell trafficking in liver injury. FASEB J. 19, 1225–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Am Esch JS 2nd, Knoefel T, Klein M, Ghodsizad A, Fuerst G, Poll LW, Piechaczek C, Burchardt ER, Feifel N, Stoldt V, Sockschlader M, Stoecklein N, Tustas RY, Eisenberger CF, Peiper M, Haussinger D, Hosch SB (2005) Portal application of autologous CD133+ bone marrow cells to the liver: a novel concept to support hepatic regeneration. Stem Cells 23, 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MY, Levicar N, Pai M, Bachellier P, Dimarakis I, Al‐Allaf F, M’Hamdi H, Thalji T, Welsh JP, Marley SB, Davis J, Dazzi F, Marelli‐Berg F, Tait P, Playford R, Jiao L, Jensen S, Nicholls JP, Ayav A, Nohandani M, Farzaneh F, Gaken J, Dodge R, Alison M, Apperley JF, Lechler R, Habib NA (2006) Characterization and clinical application of human CD34+ stem/progenitor cell populations mobilized into the blood by granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor. Stem Cells 24, 1822–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch HM, Zheng D, Jorgensen ML, Petersen BE (2002) SDF‐1alpha/CXCR4: a mechanism for hepatic oval cell activation and bone marrow stem cell recruitment to the injured liver of rats. Cloning Stem Cells 4, 339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang YY, Collector MI, Baylin SB, Diehl AM, Sharkis SJ (2004) Hematopoietic stem cells convert into liver cells within days without fusion. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto A, Tkebuchava T, Yamaguchi J, Nishimura H, Yoon YS, Milliken C, Uchida S, Masuo O, Iwaguro H, Ma H, Hanley A, Silver M, Kearney M, Losordo DW, Isner JM, Asahara T (2003) Intramyocardial transplantation of autologous endothelial progenitor cells for therapeutic neovascularization of myocardial ischemia. Circulation 107, 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollet O, Shivtiel S, Chen YQ, Suriawinata J, Thung SN, Dabeva MD, Kahn J, Spiegel A, Dar A, Samira S, Goichberg P, Kalinkovich A, Arenzana‐Seisdedos F, Nagler A, Hardan I, Revel M, Shafritz Da Lapidot T (2003) HGF, SDF‐1, and MMP‐9 are involved in stress‐induced human CD34+ stem cell recruitment to the liver. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 160–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbling M, Katz RL, Khanna A, Ruifrok AC, Rondon G, Albitar M, Champlin RE, Estrov Z (2002) Hepatocytes and epithelial cells of donor origin in recipients of peripheral‐blood stem cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, Neutzel S, Sharkis SJ (2001) Multi‐organ, multi‐lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow‐derived stem cell. Cell 105, 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit I, Szyper‐Kravitz M, Nagler A, Lahav M, Peled A, Habler L, Ponomaryov T, Taichman RS, Arenzana‐Seisdedos F, Fujii N, Sandbank J, Zipori D, Lapidot T (2002) G‐CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF‐1 and up‐regulating CXCR4. Nat. Immunol. 3, 687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston SL, Alison MR, Forbes SJ, Direkze NC, Poulsom R, Wright NA (2003) The new stem cell biology: something for everyone. Mol. Pathol. 56, 86–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman J, Traktuev D, Li J, Merfeld‐Clauss S, Temm‐Grove CJ, Bovenkerk JE, Pell CL, Johnstone BH, Considine RV, March KL (2004) Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation 109, 1292–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Xie Q, Pan G, Wang J, Wang M (2006) Mesenchymal stem cells participate in angiogenesis and improve heart function in rat model of myocardial ischemia with reperfusion. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 30, 353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada N, Hamazaki T, Oka M, Hoki M, Mastalerz DM, Nakano Y, Meyer EM, Morel L, Petersen BE, Scott EW (2002) Bone marrow cells adopt the phenotype of other cells by spontaneous cell fusion. Nature 416, 542–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terai S, Ishikawa T, Omori K, Aoyama K, Marumoto Y, Urata Y, Yokoyama Y, Uchida K, Yamasaki T, Fujii Y, Okita K, Sakaida I (2006) Improved liver function in patients with liver cirrhosis after autologous bone marrow cell infusion therapy. Stem Cells 24, 2292–2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terai S, Sakaida I, Yamamoto N, Omori K, Watanabe T, Ohata S, Katada T, Miyamoto K, Shinoda K, Nishina H, Okita K (2003) An in vivo model for monitoring trans‐differentiation of bone marrow cells into functional hepatocytes. J. Biochem. 134, 551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theise ND, Nimmakayalu M, Gardner R, Illei PB, Morgan G, Teperman L, Henegariu O, Krause DS (2000a) Liver from bone marrow in humans. Hepatology 32, 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas ED (2005) Bone marrow transplantation from the personal viewpoint. Int. J. Hematol. 81, 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilopoulos G, Wang PR, Russell DW (2003) Transplanted bone marrow regenerates liver by cell fusion. Nature 422, 901–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Tsai BM, Crisostomo PR, Meldrum DR (2006) Pretreatment with adult progenitor cells improves recovery and decreases native myocardial proinflammatory signaling after ischemia. Shock 25, 454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Willenbring H, Akkari Y, Torimaru Y, Foster M, Al‐Dhalimy M, Lagasse E, Finegold M, Olson S, Grompe M (2003) Cell fusion is the principal source of bone‐marrow‐derived hepatocytes. Nature 422, 897–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]