Abstract

Abstract. The antiproliferative effects of γ‐tocotrienol are associated with suppression in epidermal growth factor (EGF)‐dependent phosphatidylinositol‐3‐kinase (PI3K)/PI3K‐dependent kinase‐1 (PDK‐1)/Akt mitogenic signalling in neoplastic mammary epithelial cells. Studies were conducted to investigate the direct effects of γ‐tocotrienol treatment on specific components within the PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic pathway. +SA cells were grown in culture and maintained in serum‐free media containing 10 ng/ml EGF as a mitogen. Treatment with 0–8 µmγ‐tocotrienol resulted in a dose‐responsive decrease in the +SA cell growth and a corresponding decrease in phospho‐Akt (active) levels. However, γ‐tocotrienol treatment had no direct inhibitory effect on Akt or PI3K enzymatic activity, suggesting that the inhibitory effects of γ‐tocotrienol occur upstream of PI3K, possibly at the level of the EGF‐receptor (ErbB1). Additional studies were conducted to determine the effects of γ‐tocotrienol on ErbB receptor activation. Results showed that γ‐tocotrienol treatment had little or no effect on ErbB1 or ErbB2 receptor tyrosine phosphorylation, a prerequisite for substrate interaction and signal transduction, but did cause a significant and progressive decrease in the ErbB3 tyrosine phosphorylation. Because ErbB1 or ErbB2 receptors form heterodimers with the ErbB3 receptor, and ErbB3 heterodimers have been shown to be the most potent activators of PI3K, these findings strongly suggest that the antiproliferative effects of γ‐tocotrienol in neoplastic +SA mouse mammary epithelial cells are mediated by a suppression in ErbB3‐receptor tyrosine phosphorylation and subsequent reduction in PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic signalling.

INTRODUCTION

The vitamin E family of compounds is divided into two subgroups called tocopherols and tocotrienols. However, tocotrienols display significantly greater antitumour activity than tocopherols at treatment doses that have little or no effect on normal mammary epithelial cell growth or viability (2000b, 2000a). Previous studies have shown that treatment with relatively low doses of γ‐tocotrienol significantly inhibited EGF‐dependent neoplastic +SA mouse mammary epithelial cell growth, whereas having no effect on cell viability (Shah & Sylvester 2005a). These studies also demonstrated that the antiproliferative effects of γ‐tocotrienol were associated with a reduction in epidermal growth factor (EGF)‐dependent activation of the PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic signalling pathway (Shah & Sylvester 2005a). PI3K is a lipid signalling kinase that activates PDK‐1, and activated PDK‐1 subsequently activates Akt (Toker 2000). Activated Akt then phosphorylates various intracellular substrates associated with cell proliferation and survival (Toker 2000). Although the exact intracellular sites of action targeted by γ‐tocotrienol to inhibit PI3K/PDK1/Akt mitogenic signalling have not yet been determined, these findings may have clinical application as elevated PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt activity is associated with advanced tumour progression and poor prognosis in breast cancer patients (Downward 1998).

Another possibility is that the antiproliferative effects of γ‐tocotrienol occur upstream of the PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic signalling pathway at the level of the EGF‐receptor. The EGF‐receptor (ErbB1) belongs to the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases that includes four members (ErbB1–4). Activation of these receptors by their appropriate ligands will induce the formation of homodimers and heterodimers (Bazley & Gullick 2005). Heterodimer formation between different ErbB receptor family members has been shown to provide greater signal duration, diversification and amplification, as compared to their corresponding homodimer receptor complex (Sliwkowski et al. 1994; Karunagaran et al. 1996). This is particularly true for the ErbB2 and the ErbB3 receptors because the ErbB2 receptor has no known ligand (Yarden 2001) and the ErbB3 receptor has no intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity (Olayioye et al. 2000). Heterodimer formation thereby allows ErbB2 and ErbB3 to participate in mitogen‐dependent signal transduction. Studies have also shown that the most potent ErbB receptor complex for stimulating cell growth and transformation is composed of ErbB3 with either ErbB1 or ErbB2 (Bazley & Gullick 2005). Following ligand binding and heterodimerization, ErbB3 becomes transphosphorylated by its heterodimer partner, and tyrosine phosphorylated ErbB3 is now able to interact and activate several important intracellular signalling proteins (Sliwkowski et al. 1994; Karunagaran et al. 1996). Studies have shown that ErbB3 heterodimers are the most important and potent activators of the PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic pathway in neoplastic mammary epithelial cells (Fedi et al. 1994; Prigent & Gullick 1994). Akt signalling promotes oncongenic expression by stimulating tumour cell proliferation, transformation and metastasis, and overexpression of constitutively active Akt has been shown to reverse the proliferative block induced by treatments targeted at inhibiting ErbB receptor mitogenic signalling in neoplastic mammary epithelial cells (Holbro et al. 2003).

In order to elucidate the exact intracellular site of action mediating the inhibitory effects of γ‐tocotrienol on EGF‐dependent neoplastic +SA mammary epithelial cell proliferation, studies were conducted to determine the direct effects of γ‐tocotrienol on specific components within the PI3K/PDK1/Akt mitogenic signalling pathway. Studies were also conducted to examine the effects of γ‐tocotrienol on EGF‐dependent ErbB receptor family activation and tyrosine phosphorylation in these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

All reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. Purified γ‐tocotrienol was generously provided Dr Abdul Gapor at the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia). Polyclonal antibodies for phospho‐ErbB3 (Tyr1289), phospho‐ErbB2 (Tyr1248), phospho‐ErbB2 (Tyr877), phospho‐EGF receptor (Tyr992), phospho‐EGF receptor (Tyr1068), PI3K p85 subunit, PI3K p110α subunit, phospho‐PDK1 (Ser241), phospho‐Akt (Ser473), and total Akt were purchased from Cell Signalling Technology (Beverly, MA). Polyclonal antiβ‐actin and antiα‐tubulin were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Goat antirabbit secondary antibody was purchased from PerkinElmer Biosciences (Boston, MA).

Cell culture and experimental treatment

The highly malignant +SA mammary epithelial cell line was derived from an adenocarcinoma that developed spontaneously in a BALB/c female mouse (Danielson et al. 1980; Anderson et al. 1981). Cell culture and the experimental procedures have been previously described in detail (Sylvester et al. 2002; Shah et al. 2003). Briefly, cells were grown and routinely maintained in serum‐free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 control media containing 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 10 µg/ml transferrin, 100 µg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 10 µg/ml insulin, and 10 ng/ml EGF as a mitogen. Cells were maintained at 37.0 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95.0% air and 5.0% CO2. In order to dissolve the highly lipophilic γ‐tocotrienol and α‐tocopherol in aqueous culture media, it was bound to BSA, as previously described (McIntyre et al. 2000a).

Measurement of viable cell number

Viable cell number was determined using the 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) colourimetric assay as described previously (Sylvester et al. 1994; McIntyre et al. 2000a). Briefly, 5 × 104 cells per well were initially plated in 24‐well culture plates and allowed to adhere to the plastic plates overnight (12 h). The following day, the cells were divided into different treatment groups and media was removed, replaced with fresh control or treatment media, and then returned to the incubator. At the end of the treatment period, media in all treatment groups was removed and replaced with fresh control media containing 0.83 mg/ml MTT, and the cells were returned to the incubator for a period of 4 h. At the end of the incubation period, the media was removed, the MTT crystals were dissolved in 1 ml of isopropanol, and the optical density of each sample was read at 570 nm on a microplate reader (SpectraCount, Packard BioScience Company, Meriden, CT). The number of cells per well were calculated against a standard curve prepared by plating known concentrations of cells, as determined by the haemocytometer, at the start of each experiment.

Electrophoresis and Western blot analysis

Cells in the various treatment groups were isolated by trypsin and whole cell lysates were prepared for subsequent electrophoresis and Western blot analysis, as described previously (Shah & Sylvester 2005a; Shah & Sylvester 2005b). The protein concentration in each treatment sample was determined using the Bio‐Rad protein assay kit (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of protein (30 µg) from each sample were loaded on 7.5–10% sodium dodecyl sulphate‐polyacrylamide minigels and electrophoresed. Proteins were transblotted (25 V for 12–16 h) to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Dupont, Boston, MA) and then blocked with 2% BSA in 0.1% Tween tris buffered saline (TBS) for 2 h. The PVDF membranes were probed with specific primary antibodies (1 : 5000) for an additional 2 h at room temperature, rinsed, and then treated for 1 h with secondary antibody (1 : 2000) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Antibody‐bound proteins were visualized with the SuperSignal enhanced chemiluminescence kit according to the manufacturer's (Pierce, Rockford, IL) instructions. The visualization of β‐actin or α‐tubulin was used to confirm that there was equal sample loading in each lane.

Akt and PI3K enzymatic assays

The direct effects of 0–10 µmγ‐tocotrienol and 0–100 µmα‐tocopherol on enzyme activity were determined using an Akt assay kit following the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Stressgen Bioreagents, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada). Briefly, an appropriate amount of γ‐tocotrienol and α‐tocopherol were dissolved in 100% ethanol, serially diluted, and then added to 25 ng of purified activated Akt and excess ATP in a 96‐well plate pre‐coated with peptide substrate, for a 90‐min reaction period. The reaction mixture was then aspirated from wells and antibody directed against the phosphorylated substrate, was added to each well, followed by a peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody. Kinase activity was visualized by the addition of tetramethylbenzidine substrate. Optical density for each sample was directly proportional to the Akt phosphotransferase activity and was measured with a microplate reader at 450 nm. In addition, the direct effects of γ‐tocotrienol and α‐tocopherol on PI3K enzymatic activity was measured following the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, UT) in the assay kit. The PI3K assay is a competitive enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in which the optical density of the reaction is inversely proportional to the amount of the PI (3, 4, 5) P3 generated in the reaction. Briefly, an appropriate amount of γ‐tocotrienol and α‐tocopherol were dissolved in 100% ethanol, serially diluted, and then added to 25 ng of purified activated PI3K, substrate (PIP2) and excess ATP for a 3 h reaction period. Afterwards, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and then mixed and incubated with the PI (3, 4, 5) P3 detector protein. The reaction mixture was then added to the PI (3, 4, 5) P3 coated 96‐well microplate for competitive binding, followed by the addition of a peroxidase secondary antibody. Optical density for each sample was inversely proportional to the amount of the PI (3, 4, 5) P3 produced and PI3K enzymatic activity was estimated by comparing experimental values with a standard curve generated by plotting the optical density against known concentrations of PI (3, 4, 5) P3.

Statistical analysis

Differences among the various treatment groups were determined by analysis of variance (anova) followed by Dunnett's t‐test. Differences were considered statistically significant at a value of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

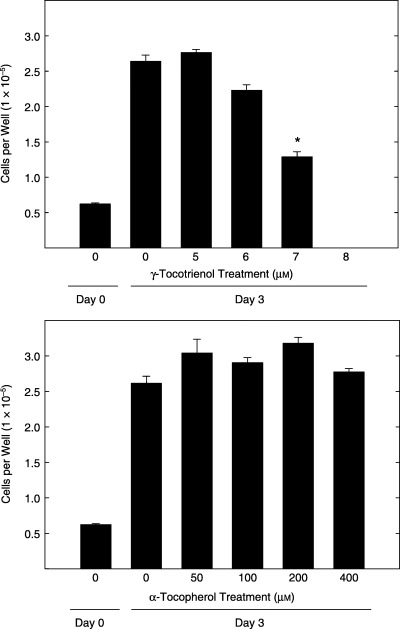

The effects of γ‐tocotrienol (Top) and α‐tocopherol (Bottom) treatment on malignant +SA mammary epithelial cell proliferation after a 3‐day culture period are shown in Fig. 1. Treatment with 0–8 µmγ‐tocotrienol significantly inhibited +SA cell growth in a dose‐responsive manner (Fig. 1, Top). From these studies it was determined that 7 µmγ‐tocotrienol caused an approximate 50% reduction in +SA cell growth and this treatment dose was then used in subsequent studies to determine the specific intracellular components within the PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic pathway involved in mediating the antiproliferative effects of γ‐tocotrienols in these cells. In contrast, treatment with 0–400 µmα‐tocopherol had no effect on neoplastic +SA mammary epithelial cell growth and was subsequently used as a negative control in later studies (Fig. 1, Bottom).

Figure 1.

Effects of 0–8 µmγ‐tocotrienol (top) and 0–400 µmα‐tocopherol (bottom) on +SA malignant mammary epithelial cell growth over a 72 h treatment period. Cells in all treatment groups were initially plated at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well in 24‐well culture plates. Vertical bars indicate the mean viable cell number/well ± SEM for six replicates in each treatment group. *P < 0.05, as compared to untreated controls.

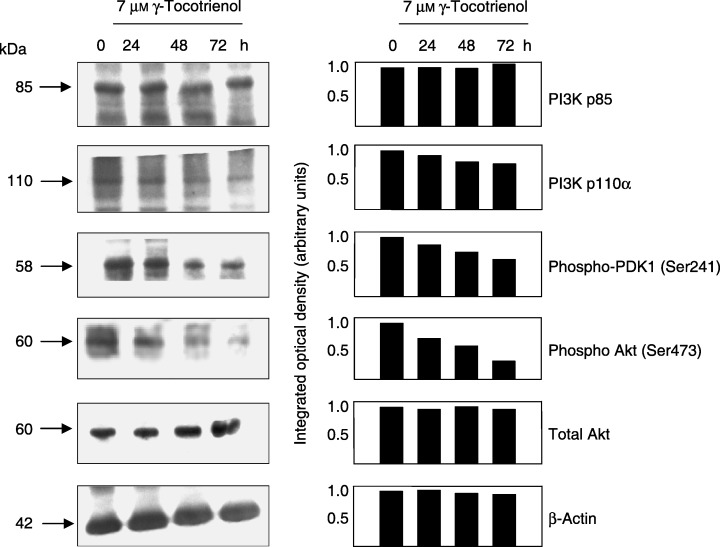

Figure 2 shows Western blot analysis of various intracellular proteins associated with the PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic‐signalling pathway throughout a 72 h treatment period following treatment with a growth inhibiting dose (7 µm) of γ‐tocotrienol. Prior to treatment (0 h), +SA cells maintained in serum‐free defined medium containing 10 ng/ml EGF as a mitogen displayed Western blot bands of moderate intensity for PI3K p85 (regulatory subunit), PI3K p110α (catalytic subunit), phospho‐PDK‐1 (active form), phospho‐Akt (active form) and total Akt (Fig. 2). However, treatment with 7 µmγ‐tocotrienol caused a progressive decrease in Western blot band intensity of phospho‐PDK‐1, and phospho‐Akt over the 72 h treatment period, whereas having little or no effect on PI3K p85, PI3K p110α or total Akt band intensity (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Western blot and scanning densitometric analysis of PI3K p85 (regulatory subunit), PI3K p110α (catalytic subunit), phospho‐PDK1 (active form), phospho‐Akt (active form) and total Akt levels in malignant +SA mammary epithelial cells following a 0–72 h treatment exposure to 7 µmγ‐tocotrienol. Cells in each treatment group were initially plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells/100 mm culture dish. Following treatment exposure, whole cell lysates were prepared for subsequent fractionation by SDS‐PAGE (30 µg/lane), followed by Western blot analysis. Each Western blot is a representative example of data obtained for experiments that were repeated at least three times. Scanning densitometric analysis was performed for each blot and is shown next to their respective Western blot. Vertical bars represent the integrated optical density of bands visualized in each lane.

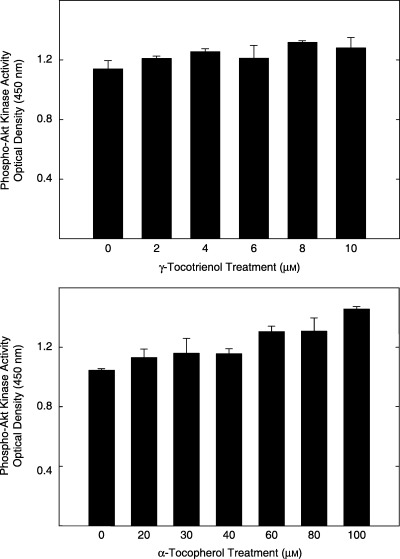

The direct effects of 0–10 µmγ‐tocotrienol (top) and 0–100 µmα‐tocopherol (bottom) on purified active recombinant Akt enzymatic activity are shown in Fig. 3. This assay utilizes a specific synthetic peptide as a substrate for Akt and a polyclonal antibody that recognizes the phosphorylated (active) form of the substrate. Treatment with various doses of γ‐tocotrienol (Fig. 3, Top) or α‐tocopherol (Fig. 3, Bottom) had no direct effect on Akt kinase activity, as compared to the vehicle‐treated control groups. These findings demonstrate that γ‐tocotrienol has no direct inhibitory effect on Akt activity and that γ‐tocotrienol inhibition of EGF‐dependent Akt activation in neoplastic +SA mammary epithelial cells must occur upstream of the Akt enzyme.

Figure 3.

Direct effects of 0–10 µmγ‐tocotrienol (top) and 0–100 µmα‐tocopherol (bottom) on Akt kinase activity. Various doses of γ‐tocotrienol or α‐tocopherol were dissolved in 100% ethanol, and then incubated with 25 ng of activated Akt and excess ATP as described in the instructions provided by the manufacturer in the assay kit. Akt activity is expressed as optical density units at 450 nm. Vertical bars represent the mean ± SD of duplicates in each treatment group. Each experiment was repeated at two to three times.

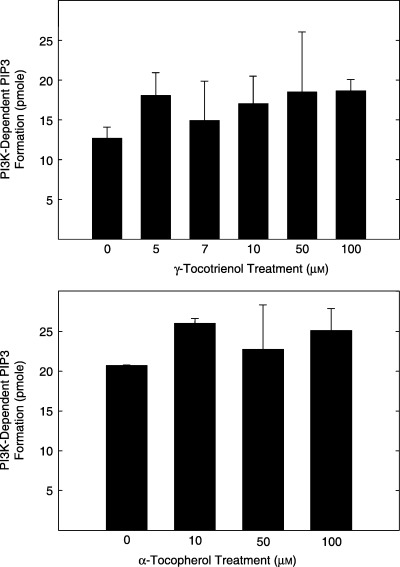

Studies were also conducted to determine the direct effects of 0–100 µmγ‐tocotrienol (top) and α‐tocopherol (bottom) on purified active recombinant PI3K enzymatic activity are shown in Fig. 4. The PI3K assay is a competitive ELISA in which the colourimetric signal generated at the end of the reaction is inversely proportional to the amount of the PI (3, 4, 5) P3 generated during the assay period. Results showed that treatment with very high doses of γ‐tocotrienol had no direct inhibitory effect on PI3K enzymatic activity (Fig. 4, Top). Similar results were observed with using very high doses of α‐tocopherol, a negative control (Fig. 4, Bottom). These findings also demonstrate that the inhibitory effects of γ‐tocotrienol on EGF‐dependent PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic signalling must occur upstream of PI3K, possibly at the level of the EGF‐receptor.

Figure 4.

Direct effects of 0–10 µmγ‐tocotrienol (top) and 0–100 µmα‐tocopherol (bottom) on PI3K activity. Various doses of γ‐tocotrienol or α‐tocopherol were dissolved in 100% ethanol, and then incubated with 25 ng of activated PI3K, excess ATP, and substrate (PIP2) following the instructions provided by the manufacturer in the assay kit. PI3K activity is expressed as PI3K‐dependent PIP3 formation in pmol. Vertical bars represent the mean ± SD of duplicates in each treatment group. Each experiment was repeated at two to three times.

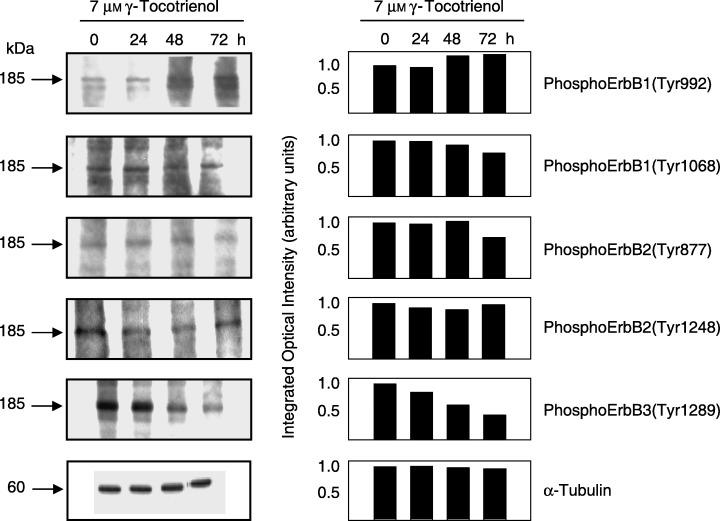

The effects of 7 µmγ‐tocotrienol on ErbB receptor family member activation (tyrosine phosphorylation) in neoplastic +SA mammary epithelial cells throughout the 72 h treatment period are shown in Fig. 5. Western blot analysis showed that γ‐tocotrienol treatment had little effect on the relative band intensity of phospho‐ErbB1 (Tyr992 and Tyr1068) or phospho‐ErbB2 (Tyr877 and Tyr1248) at various times throughout the 72 h treatment period (Fig. 5). However, this same treatment resulted in a large and sustained decrease in the relative levels of phospho‐ErbB3 (Tyr1289) in +SA cells throughout the 72 h treatment period cells (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Western blot and scanning densitometric analysis of phosphoErbB1 (Tyr992), phosphoErbB1 (Tyr1068), phosphoErbB2 (Tyr877), phosphoErbB2 (Tyr1248) and phosphoErbB3 (Tyr1289) in neoplastic +SA mammary epithelial cells following a 0–72‐h treatment exposure to 7 µmγ‐tocotrienol. Cells in each treatment group were initially plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells/100 mm culture dish. Following treatment exposure, whole cell lysates were prepared for subsequent fractionation by SDS‐PAGE (30 µg/lane), followed by Western blot analysis. Each Western blot is a representative example of data obtained for experiments that were repeated at least three times. Scanning densitometric analysis was performed for each blot and is shown next to their respective Western blot. Vertical bars represent the integrated optical density of bands visualized in each lane.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate that the antiproliferative effects of γ‐tocotrienol on neoplastic +SA mammary epithelial cells are mediated through a reduction in ErbB3 tyrosine phosphorylation and subsequent activation of the PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic signalling pathway. Treatment with 7 µmγ‐tocotrienol resulted in an approximately 50% reduction in EGF‐dependent +SA cell growth, and these effects are associated with a corresponding decrease in phospho‐Akt (active) levels in these cells. Studies also showed that treatment with similar or higher doses of γ‐tocotrienol had no direct inhibitory effect on PI3K or Akt kinase activity, indicating that this isoform of vitamin E is acting upstream of the PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt signalling pathway at the level of the EGF‐receptor (ErbB1). Additional studies showed that γ‐tocotrienol treatment had little or no effect on ErbB1 or ErbB2 tyrosine phosphorylation, but did cause a large reduction in the relative levels of ErbB3 tyrosine phosphorylation. Because tyrosine phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain of ErbB receptors is required for interaction and activation of intracellular substrates, and activated ErbB3 receptor heterodimers are the most potent stimulators of the PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic signalling pathway in neoplastic mammary epithelial cells (Fedi et al. 1994; Prigent & Gullick 1994), these data strongly suggest that γ‐tocotrienol therapy may be useful for suppressing the growth and survival of breast cancer cells characterized by enhanced expression of ErbB receptors.

These data confirm and extend previous investigations, which demonstrated that γ‐tocotrienol suppression of cell growth was associated with a reduction in the activation of PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic pathway (Shah & Sylvester 2005a). However, previous studies did not identify the specific intracellular sites targeted by γ‐tocotrienol to suppress mitogenic signalling in this pathway. The present study shows that γ‐tocotrienol does not act directly to inhibit PI3K or Akt kinase activity, and had little or no effect on the relative levels of the p85 regulatory subunit or the p110α catalytic subunit of the PI3K. These findings indicate that the inhibitory effects of γ‐tocotrienol on PI3K signalling appear to involve the prevention of ErbB receptor activation of PI3K.

The ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases is composed of four interacting receptor members called ErbB1, ErbB2, ErbB3 and ErbB4 (Bazley & Gullick 2005). Structurally, each member of the ErbB family contains an extracellular ligand‐binding domain, a transmembrane domain and a catalytic cytoplasmic domain (Olayioye et al. 2000; Yarden 2001). However, individual ErbB receptors differ from each other in terms of ligand specificity, tyrosine kinase activity, and substrate activation (Bazley & Gullick 2005). In the absence of ligand stimulation, ErbB receptors exist within the cell membrane as an inactive monomer. Ligand activation of ErbB1 receptors can result in the formation of a stable homodimer, leading to the transphosphorylation of tyrosine residues located on the intracellular catalytic domain of their corresponding receptor partner (Olayioye et al. 2000; Yarden 2001). Tyrosine phosphorylation of the ErbB receptor cytoplasmic domain is required for intracellular substrate interaction and signal transduction (Olayioye et al. 2000; Yarden 2001). In contrast, the constitutively active ErbB2 receptor displays no ligand binding, but can interact with other ErbB2 receptors to form activated homodimers or other ligand‐bound ErbB receptors to form activated heterodimers (Sliwkowski et al. 1994; Karunagaran et al. 1996). Although the ErbB3 receptor is devoid of intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, ligand binding to ErbB3 can induce heterodimer formation with ErbB1 or ErbB2, which will then transphosphorylate the cytoplasmic domain of the ErbB3 receptor and thereby enabling the tyrosine phosphorylated ErbB3 receptor to participation in the activation of various signalling pathways (Kim et al. 1998). All ErbB receptors share common signalling pathways, but individual ErbB receptors preferentially bind specific intracellular substrates based on the presence of defined cytoplasmic domain tyrosine phosphorylation sites. This is particularly important for the transphosphorylated ErbB3 heterodimer, which has been shown to be the most efficient activator of PI3K because of specific interactions with the p85 regulatory subunit of this lipid kinase (Bazley & Gullick 2005). Studies have also shown that ErbB3 heterodimers are extremely stable and remain at the cell surface for a prolonged period of time, and suppression of ErbB3 transphosphorylation significantly inhibits PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt signalling and greatly reduce tumour cell proliferation and survival (Holbro et al. 2003; Britten 2004).

At present, the exact mechanism by which γ‐tocotrienol inhibits EGF‐dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB3 is unknown. Several agents that target ErbB receptors, such as ErbB‐targeted monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab or trastuzumab) or selected ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (gefitinib, or lapatinib) are currently being used in the treatment of cancer (Britten 2004). However, co‐operation between the different ErbB receptor family members can rescue cancer cells from the antiproliferative activity of agents directed against a single ErbB receptor, a characteristic that has limited the clinical success of these agents (Normanno et al. 2002; Britten 2004). Interestingly, the mechanism of action displayed by γ‐tocotrienol appears to be uniquely different than that of these other agents in targeting ErbB receptor activation or function. Results showed that γ‐tocotrienol does not act as kinase inhibitor and had little or no effect on EGF‐dependent ErbB1 or ErbB2 activation and tyrosine phosphorylation. Instead, γ‐tocotrienol appears to specifically inhibit ErbB3 heterodimer tyrosine transphosphorylation, possibly by selectively inhibiting ErbB3 ligand binding or by preventing heterodimer formation between ErbB3 and other ErbB receptor family members. Further studies are required to determine if either of these suggestions is correct.

In conclusion, this study provides new evidence that the antiproliferative effects of γ‐tocotrienol on neoplastic +SA mouse mammary epithelial cells are mediated through a decrease in the ErbB3 receptor tyrosine phosphorylation and subsequent reduction in PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic signalling. Because elevated Akt signalling is associated with advanced tumour progression and poor prognosis in breast cancer patients (Downward 1998) and ErbB3 heterodimers are the most potent activators of the PI3K/PDK‐1/Akt mitogenic pathway (Fedi et al. 1994; Prigent & Gullick 1994), these findings strongly suggest that γ‐tocotrienol may have potential therapeutic value when used in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents directed against selected ErbB receptor activation in the treatment of breast cancer in women. This suggestion is further supported by in vitro and in vivo studies that have shown that combined therapy directed against multiple members of the ErbB receptor family display significantly greater antitumour activity than agents that target only a single ErbB receptor (Normanno et al. 2002; Britten 2004).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant CA 86833. The authors would like to thank the Malaysian Palm Oil Board for their support and generously providing γ‐tocotrienol for use in these studies.

REFERENCES

- Anderson LW, Danielson KG, Hosick HL (1981) Metastatic potential of hyperplastic alveolar nodule derived mouse mammary tumor cells following intravenous inoculation. Eur. J. Cancer Clin. Oncol. 17, 1001–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazley LA, Gullick WJ (2005) The epidermal growth factor receptor family. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 12 (Suppl. 1), S17–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten CD (2004) Targeting ErbB receptor signaling: a pan‐ErbB approach to cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 3, 1335–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson KG, Anderson LW, Hosick HL (1980) Selection and characterization in culture of mammary tumor cells with distinctive growth properties in vivo. Cancer Res. 40, 1812–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downward J (1998) Mechanisms and consequences of activation of protein kinase B/Akt. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10, 262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedi P, Pierce JH, Di Fiore PP, Kraus MH (1994) Efficient coupling with phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase, but not phospholipase C gamma or GTPase‐activating protein, distinguishes ErbB‐3 signaling from that of other ErbB/EGFR family members. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbro T, Beerli RR, Maurer F, Koziczak M, Barbas CF, Hynes NE (2003) The ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimer functions as an oncogenic unit: ErbB2 requires ErbB3 to drive breast tumor cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8933–8938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunagaran D, Tzahar E, Beerli RR, Chen X, Graus‐Porta D, Ratzkin BJ, Seger R, Hynes NE, Yarden Y (1996) ErbB‐2 is a common auxiliary subunit of NDF and EGF receptors: implications for breast cancer. EMBO J. 15, 254–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HH, Vijapurkar U, Hellyer NJ, Bravo D, Koland JG (1998) Signal transduction by epidermal growth factor and heregulin via the kinase‐deficient ErbB3 protein. Biochem. J. 334 (1), 189–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre BS, Briski KP, Gapor A, Sylvester PW (2000b) Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of tocopherols and tocotrienols on preneoplastic and neoplastic mouse mammary epithelial cells. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 224, 292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre BS, Briski KP, Tirmenstein MA, Fariss MW, Gapor A, Sylvester PW (2000a) Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of tocopherols and tocotrienols on normal mouse mammary epithelial cells. Lipids 35, 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normanno N, De Campiglio MLA, Somenzi G, Maiello M, Ciardiello F, Gianni L, Salomon DS, Menard S (2002) Cooperative inhibitory effect of ZD1839 (Iressa) in combination with trastuzumab (Herceptin) on human breast cancer cell growth. Ann. Oncol. 13, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olayioye MA, Neve RM, Lane HA, Hynes NE (2000) The ErbB signaling network: receptor heterodimerization in development and cancer. EMBO J. 19, 3159–3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigent SA, Gullick WJ (1994) Identification of c‐erbB‐3 binding sites for phosphatidylinositol 3′‐kinase and SHC using an EGF receptor/c‐erbB‐3 chimera. EMBO J. 13, 2831–2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Gapor A, Sylvester PW (2003) Role of caspase‐8 activation in mediating vitamin E‐induced apoptosis in murine mammary cancer cells. Nutr. Cancer 45, 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SJ, Sylvester PW (2005a) Gamma‐tocotrienol inhibits neoplastic mammary epithelial cell proliferation by decreasing Akt and nuclear factor kappaB activity. Exp. Biol. Med. 230, 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SJ, Sylvester PW (2005b) Tocotrienol‐induced cytotoxicity is unrelated to mitochondrial stress apoptotic signaling in neoplastic mammary epithelial cells. Biochem. Cell Biol. 83, 86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwkowski MX, Schaefer G, Akita RW, Lofgren JA, Fitzpatrick VD, Nuijens A, Fendly BM, Cerione RA, Vandlen RL, Carraway KL (1994) Coexpression of erbB2 and erbB3 proteins reconstitutes a high affinity receptor for heregulin. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14661–14665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester PW, Birkenfeld HP, Hosick HL, Briski KP (1994) Fatty acid modulation of epidermal growth factor‐induced mouse mammary epithelial cell proliferation in vitro . Exp. Cell. Res. 214, 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester PW, Nachnani A, Shah S, Briski KP (2002) Role of GTP‐binding proteins in reversing the antiproliferative effects of tocotrienols in preneoplastic mammary epithelial cells. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 11, S452–S459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toker A (2000) Protein kinases as mediators of phosphoinositide 3‐kinase signaling. Mol. Pharmacol. 57, 652–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarden Y (2001) The EGFR family and its ligands in human cancer. signalling mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Eur. J. Cancer 37 (Suppl. 4), S3–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]