Abstract

GADD45 is an evolutionarily conserved gene that encodes a small acidic, nuclear protein and is an example of a p53 responsive gene. Gadd45 protein has been shown to interact with PCNA and also p21waf1. It has been implicated in growth arrest, DNA repair, chromatin structure and signal transduction. The confusing biochemical data has been clarified by the demonstration that Gadd45 null mice have a phenotype strikingly similar to that of p53 null mice, being tumour prone and showing marked genomic instability. We have tested the hypothesis that mutations in the GADD45 coding region might substitute for p53 abnormalities in tumour cell lines where p53 is wild type. After generating cDNA from mRNA in a panel of 24 cell lines we sequenced the GADD45 cDNA and have demonstrated that no mutations can be observed, even in the p53 wild type cell lines. Such data suggest that Gadd45 mutations are uncommon in human cancer. From this we postulate that, despite the phenotype of the GADD45 null mouse, GADD45 is unlikely to be the key mechanistic determinant of the tumour suppressor activity of the p53 pathway.

Note on nomenclature: We have employed GADD45 to designate the gene and Gadd45 to designate the encoded protein. This gene has also be denoted GADD45α elsewhere in the literature.

INTRODUCTION

Functional inactivation of p53 is a very common event in many types of human cancer ( Greenblatt et al. 1994 ) and is a key step in oncogenesis ( Hahn et al. 1999 ). Burgeoning data indicate that p53 acts as a transcription factor at a nodal point in the flow of information from diverse cellular stimuli, and that p53 activation eventuates in the regulation, a still poorly defined, set of down stream target genes ( Prives & Hall 1999). The spectrum of genes activated (and repressed) by p53 are almost certainly influenced by many diverse factors, including cell type ( MacCallum et al. 1996 ). The function of the products of such genes are diverse and include proteins involved in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis and other activities. Given the key role of p53 as a tumour suppressor, a key challenge is to define the set of p53 regulated genes that mediate the tumour suppressor activities of p53. One well known (if poorly understood) downstream target of p53 is GADD45 ( Fornace et al. 1989 ; Kastan et al. 1992 ; Hollander et al. 1993 ).

The GADD45 gene is highly conserved in mammals, is a p53 responsive gene and can be induced by DNA damage in a p53 dependent manner ( Kastan et al. 1992 ; Hollander 1993). The Gadd45 protein is an acidic nuclear protein ( Kearsey et al. 1995a ), that can interact with p21waf1 ( Smith et al. 1994 ; Kearsey et al. 1995a ) and with PCNA ( Hall et al. 1995 ). Over‐expression of Gadd45 can induce growth arrest ( Wang et al. 1999 ) and Gadd45 has been proposed to be involved in DNA repair ( Smith et al. 1994 ), although this is controversial ( Kearsey et al. 1995b ). More recently it has become clear that there exists a family of GADD45‐like genes encoding very similar proteins ( Takekawa & Saito 1998). The complexity of this family of molecules is underscored by the apparently diverse range of properties of Gadd45, with reports suggesting roles in signal transduction ( Takekawa & Saito 1998; Harkin et al. 1999 ) and chromatin structure ( Carrier et al. 1999 ), as well as growth arrest and DNA repair ( Smith et al. 1994 ; (1995a), (1995b); Wang et al. 1999 ). More recently it has been suggested that Gadd45 can interact with cyclin B cdc2 complexes ( Zhan et al. 1999 ). At present it is difficult to synthesize from these diverse data a clear model of Gadd45 function, yet it is clear that GADD45 is a gene potently activated by p53. Compelling evidence for an important biological role for Gadd45 protein in the response of cells to DNA damage has come from the analysis of the phenotype of Gadd45 null mice ( Hollander et al. 1999 ). Such mice, generated by gene targeting, show marked genomic instability, increased radiation carcinogenesis and a low frequency of exencephaly: a phenotype strikingly similar to that of the p53 null mouse ( Hollander et al. 1999 ). Given this background we hypothesized that Gadd45 mutations may, in some settings, substitute for p53 mutations in human oncogenesis. For example, in the presence of wild type p53, loss of function (by mutation or by bi‐allelic deletion) should give a similar phenotype to p53 inactivation. Consequently we have examined the sequence of the coding region of the Gadd45 mRNA in a panel of human tumour cell lines with known p53 status (wild type, mutant or null).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

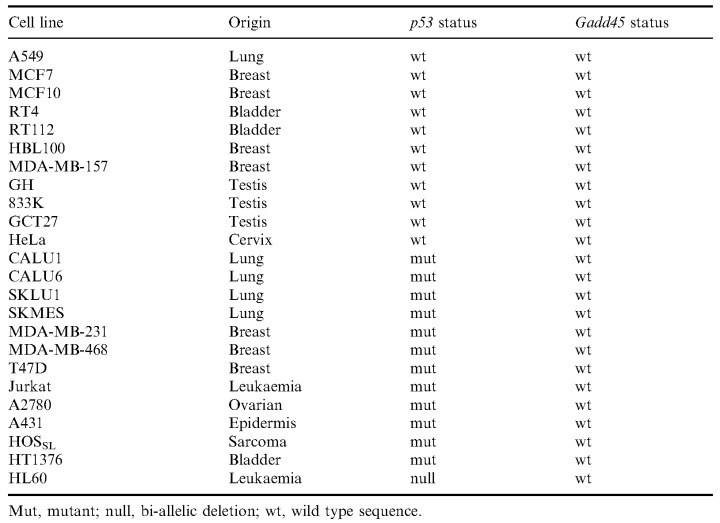

The human cell lines analysed in this study are listed in Table 1 and were obtained from Fred Brewster (CRC Cell Transformation Unit, University of Dundee, UK) and from the National Institute for Cancer Research, Genova, Italy. Cells were cultured in the appropriate complete medium (DMEM or RPMI, Gibco BRL, Paisley, UK). RNAs from the testicular and bladder carcinoma cell lines were a generous gift from Dr Christine Chresta, University of Manchester, UK. The cell lines were chosen to represent p53 wild type and p53 mutant status and a diverse range of histogenetic origins.

RNA and cDNA preparation

Messenger RNA was prepared using the Quickprep mRNA preparation kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK), according to the manufacturers instructions, starting from about 1 × 107 cells. One microgram of mRNA was used for each cDNA preparation. The reactions were performed in 10 mM TrisHCl pH 8.8, 50 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X100, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 10 pmoles of oligod(T)17 1 U rRNasin ribonuclease inhibitor (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 15 U AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega), at 42°C for 1 h, followed by 5′ incubation at 99°C.

PCR amplification

Primers 45‐1 and 45‐2 were used to PCR amplify the whole coding sequence of Gadd45 starting from 1 to 3 µl of cDNA. The cycles were as follows: three cycles of 94°C for 1′, 57°C for 1′ and 72°C for 2′ 27 cycles of 94°C for 1°, 63°C for 1′ and 72°C for 2′ final extension 72°C for 10′. Appropriate precautions were employed to prevent cross‐contamination of PCR products and templates. The following primers were employed:

-

45‐1: 5′ GAT CGA GAT CTC TAT GAC TTT GGA GGA ATT 3′ (30mer)

-

45‐2: 5′ GAT CAG ATC TTC ACC GTT CAG GGA GAT TA 3′ (29mer)

-

45‐3: 5′ AGC CAC ATC TCT GTC GTC 3′ (18mer)

-

45‐4: 5′ CTC TTG GAG ACC GAC GTC 3′ (18mer)

Purification of the PCR products and DNA sequencing

PCR reactions were run on agarose gels and the bands excised and purified using the Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen). 0.5 pmol purified PCR template was then sequenced by the Sanger dideoxy termination method using Sequenase version 2.0 (USB Biochemicals) and γ35SdATP (Dupont NEN).

RESULTS

PCR amplification of the Gadd45 coding sequence from the 24 human cell lines gave the expected 521 bp band. Specific bands were excised, purified and sequenced using four different primers as described in Materials and Methods. No mutation was detected in any of the cell lines analysed ( Table 1). These data were compared with previously reported p53 status ( Chresta et al. 1996 ; O’Connor et al. 1997 ; Hainault et al. 1998 ). Of note is that the 11 p53 wild type tumours also had no abnormality of the Gadd45 coding sequence.

Table 1.

The p53 status and Gadd45 status of 24 established human cancer cell lines

DISCUSSION

Considerable progress has been made in the identification and cataloguing of the molecular abnormalities in human (and animal) neoplasia. Nevertheless we still remain uncertain about the pathogenesis of many kinds of cancer, and of the molecular abnormalities that can occur. The present study has demonstrated that, in a panel of human carcinoma cell lines, Gadd45 mutation is not a common event. We deliberately chose to examine a panel in which cell lines with wild type p53 were represented, since we hypothesized that in such tumours alternate mutational events might lead to the functional abrogation of the p53 pathway. Gadd45 remains a poorly understood molecule, although (as outlined in the introduction) there is now compelling evidence that it is a contributor to the genomic stability seen in normal cells. In particular, the striking similarity of the phenotype of p53 null and Gadd45 null mice and cell derived from such mice suggests that Gadd45 may be a key downsteam target of p53 activity.

The data presented in this work indicate that mutation of Gadd45 coding region is not a common event in human oncogenesis. Support for this notion comes from the only other reported analysis of the GADD45 gene in human cancer. Blaszyk et al. (1996) investigated the Gadd45 status in a panel of primary breast tumours sample, positing that in breast tissue one pathway leading to carcinogenesis involves the ATM, p53 and Gadd45 gene products and that mutations in the ATM and p53 genes have already been demonstrated in this type of tumour. No mutations were present in the panel of samples analysed. Taken together these data suggest that, despite the fact that GADD45 mutation represents a phenocopy of p53 inactivation, GADD45 is not a common target for mutational inactivation in human cancer. One possible explanation for this is the existence of a family of GADD45 like genes ( Takekawa & Saito 1998). Could complementation of GADD45 inactivation by other family members occur? While this possibility cannot be dismissed, the phenotype of the GADD45 null mice (where GADD45B [Myd118] and GADD45C [CR6] remain un‐mutated and hence fully functional) argues against this model. Another possibility is that mutations exist in the GADD45 regulatory regions and specifically in the p53 binding sites. However improbable this is formally a possibility.

While in the artificial setting of gene targeting in mice GADD45 inactivation and p53 inactivation are phenocopies ( Hollander et al. 1999 ), it would seem that GADD45 may not be a critical target for inactivation in the same way as p53. A similar observation has been reported for p21waf1, which is another p53 target gene with potent effects on cells, but in which mutation is a rare event in human cancer. Why should it be that p53 is so commonly altered in human cancer but that apparently critical downstream targets do not appear to be similar targets for oncogenic inactivation? The possibility that the p53 locus is in some way a hot spot for mutation seems unlikely given the predilection for inactivating mutations in the DNA binding domain of the molecule (1, 3). Similarly it seems unlikely that the GADD45 (and p21waf1) loci are relatively resistant to mutation. Much more likely is that there is profound selective pressure on the emergence of clones of cells with p53 mutation that is not effective on the GADD45 (and p21waf1) loci. Presumably it is the very fact that p53 lies at a nodal point in adaptive pathways, being able to integrate diverse input signals (via ARF, ATM, ATR, DNA‐PK, etc.) and coordinate the transcription of a gamut of downstream targets (of which GADD45 is but one), that gives such a potent selective advantage to cells with p53 mutation. Nevertheless this is seemingly at odds with the striking similarity of the GADD45 null and the p53 null mice. Clearly the pleiotropic effects of p53 activity are central to its tumour suppressor function. Thus in many respects we remain profoundly ignorant of the true mechanism by which p53 exerts its tumour suppressor effects.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Commissioners of the European Community. Work in the Hall lab has been supported by the CRC, the AICR, the Department of Health and the European Union. We thank Fred Brewster for assistance with cell culture.

REFERENCES

- Blaszyk H, Hartmann A, Sommer SS, Kovach JS (1996). A polymorphism but no mutations in the GADD45 gene in breast cancers. Hum Genet 97,543 547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier F, Georgel PT, Pourquier P et al. (1999). Gadd45, a p53‐responsive stress protein, modifies DNA accessibility on damaged chromatin . Mol Cell Biol. 19,1673 1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chresta CM, Masters JRW, Hickman JA (1996). Hypersensitivity of human testicular tumors to etoposide‐induced apoptosis is associated with functional p53 and a high bax: bcl‐2 ratio. Cancer Res. 56,1834 1841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornace Aj Jr, Nebert DW, Hollander MC et al. (1989). Mammalian genes coordinately regulated by growth arrest signals and DNA‐damaging agents. Mol Cell Biol. 9,4196 4203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt MS, Bennett WP, Hollstein M, Harris CC (1994). Mutations in the p53 tumour supressor gene: clues to cancer aetiology and molecular pathogenesis. Cancer Res. 54,4855 4878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn WC, Counter CM, Lundberg AS, Beijersbergen RL, Brooks MW, Weinberg RA (1999). Creation of human tumour cells with defined genetic elements. Nature 400,464 468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainault P, Hernandez T, Robinson A et al. (1998). IARC database of p53 mutations in human tumours and cell lines: updated compilation, revised formats and new visualisation tools. Nucl Acid Res. 26,205 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall PA, Kearsey JM, Coates PJ, Norman DG, Warbrick E, Cox LS (1995). Characterisation of the interaction between PCNA and Gadd45 . Oncogene 10,2427 2433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkin DP, Bean JM, Miklos D et al. (1999). Induction of GADD45 and JNK/SAPK‐dependent apoptosis following inducible expression of BRCA1. Cell 97,575 586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander MC, Alamo I, Jackman J, Wang MG, Mcbride OW, Fornace AJ Jr (1993). Analysis of the mammalian Gadd45 gene and its response to DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem 268,24385 24393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander MC, Sheikh MS, Bulavin DV et al. (1999). Genomic instability in Gadd45adeficient mice . Nature Genet 23,176 183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastan MB, Zhan Q, El‐Deiry WS et al. (1992). A mammalian cell cycle checkpoint pathway utilizing p53 and GADD45 is defective in ataxia‐telangiectasia. Cell 71,587 597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearsey JM, Coates PJ, Prescott AR, Warbrick E, Hall PA (1995a). Gadd45 is a nuclear cell cycle regulated protein which interacts with p21Cip1 . Oncogene 11,1675 1683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearsey JM, Shivji MKK, Hall PA, Wood RD (1995b). Does the p53 upregulated Gadd45 protein have a role in excision repair? Science 270,1004 1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum DE, Huppca TR, Midgley D et al. (1996). The p53 response to ionising radiation in adult and developing murine tissues. Oncogene 13,2575 2587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor PM, Jackman J, Bae I et al. (1997). Characterization of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway in cell lines of the National Cancer Institute Anticancer Drug screen and correlations with the growth‐inhibitory potency of 123 anticancer agents. Cancer Res. 57,4285 4300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prives C & Hall PA (1999). The p53 pathway. J. Pathol 187,112 126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, Chen I‐T, Zhan Q et al. (1994). Interaction of the p53‐regulated protein Gadd45 with Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen. Science 266,1376 1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekawa M & Saito H (1998). A family of stress‐inducible GADD45‐like proteins mediate activation of the stress‐responsive MTK1/MEKK4 MAPKKK . Cell 95,521 530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XW, Zhan Q, Coursen JD et al. (1999). Gadd45 induction of a G2/M cell cycle checkpoint . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96,3706 3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q, Antinore MJ, Wang XW et al. (1999). Association with cdc2 and inhibition of cdc2/cyclin B1 kinase activity by the p53‐regulated protein Gadd45 . Oncogene 18,2892 2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]