Abstract

Abstract. The past 5 years have witnessed an explosion of interest in using adult‐derived stem cells for cell and gene therapy. This has been driven by a number of findings, in particular, the possibility that some adult stem cells can differentiate into non‐autologous cell types, and also the discovery of multipotential stem cells in adult bone marrow. These discoveries suggested a quasi‐alchemical nature of cells derived from adult organs, thus raising new and exciting therapeutic possibilities. Recent data, however, argue against the whole idea of stem cell ‘plasticity’, and bring into question the therapeutic strategies based upon this concept. Here, we will review the current state of knowledge in the field and discuss some of the clinical implications.

ADULT STEM CELLS AND THE HAEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELL

Adult stem cells (SC) have been found to reside in a variety of tissues including skin (Watt 1998), the central nervous system (Gage et al. 1995), muscle (Schultz & McCormick 1994), bone marrow (Weissman 2000), liver (Alison & Sarraf 1998), mammary gland (Welm et al. 2002), and many others. By definition, adult stem cells can self‐renew and replenish multiple cell types within the tissue they reside. The haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) resident in the bone marrow is the canonical adult stem cell described in the most detail. The multipotency and self‐renewal capacity of this population has been established by the ability of single murine HSCs to engraft and repopulate both the myeloid and lymphoid blood lineages of a myeloablated host (Smith et al. 1991). Likewise, the HSC has been the focus of many recent studies of adult stem cell potential, suggesting adult stem cells may have previously unrecognized properties.

ADULT STEM CELLS SWITCHING FATES

A central tenet of developmental biology is that, during embryogenesis, all cells become committed to specific lineages, first via germ layer specification, and later through additional levels of differentiation and specialization. Stem cells that will replenish adult tissues are also set aside during development, and these cells are thought to be committed by default to generate only a restricted lineage of cells. However, in the last few years, several publications have suggested that adult somatic cells might not be restricted to exclusively produce cells specific to their tissue of origin, and may be capable of a much wider spectrum of differentiation, exhibiting so called ‘stem cell plasticity’. Upon transplantation of bone marrow cells, several laboratories have reported the expression of donor‐derived reporter genes such as lacZ and green fluorescent protein (GFP), or the presence of donor genetic markers, such as the Y‐chromosome, in several non‐hematopoietic tissues (Eglitis & Mezey 1997; Ferrari et al. 1998; Brazelton et al. 2000; Mezey et al. 2000; Theise et al. 2000a; Jackson et al. 2001; Orlic et al. 2001; Labarge & Blau 2002). Similarly, transplantation of cells derived from brain, muscle, skin and fat, has resulted in detectable contribution in several lineages distinct from their tissue of origin (Bjornson et al. 1999; Jackson et al. 1999; Toma et al. 2001; Cousin et al. 2003). Such observations were immediately attributed to a previously unexplored developmental plasticity of primitive stem cells residing in these tissues. It was thought that, when given a new microenvironment, adult stem cells would transdifferentiate and start producing cells of their new resident tissue. The notion of adult stem cell plasticity thus challenged the long‐held concepts of developmental biology.

HAEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELLS JUMP THE FENCE

The theory of adult stem cell plasticity initially emerged from studies in which, following bone marrow transplants into myeloablated hosts, donor‐derived non‐hematopoietic cells could be identified in far reaching tissues (Table 1). In one of the most convincing demonstrations of the non‐hematopoietic potential of HSCs, bone marrow cells carrying a muscle‐specific lacZ transgene were found to contribute to differentiated muscle fibres upon acute muscle injury (Ferrari et al. 1998). This report was followed by a similar study describing the myogenic potential of a highly purified subset of HSCs in a murine model of Duchene's muscular dystrophy (Gussoni et al. 1999). Thus, it was beginning to appear that the HSCs resident in the bone marrow were multipotential and had an unsuspected ability of regenerating non‐hematopoietic tissues. These results suggested that, if donor‐derived engraftment could be increased to therapeutic levels, bone marrow transplants could be used to treat systemic non‐hematopoietic diseases (see below).

Table 1.

Donor cell contribution to non‐hematopoietic tissues after whole bone marrow or stem cell transplantation in the mouse

| Cells transplanted | Target tissue | Injury induced | Approximate frequency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBM | Macro and microglia | TBI | 0.5–2% | (Eglitis & Mezey 1997) |

| WBM | Skeletal muscle | TBI + intramuscular cardiotoxin inj. | < 0.05% | (Ferrari et al. 1998) |

| WBM | Skeletal muscle | exercise | 3.5% | (LaBarge & Blau 2002) |

| WBM | Endothelial cells | TBI | Not given | (Asahara et al. 1999) |

| WBM | Neurones | TBI | 0.2–0.3% | (Brazelton et al. 2000) |

| WBM | Neurones | TBI | 0.3–2.3% | (Mezey et al. 2000) |

| WBM | Neurones | TBI and contusion | 0 | (Castro et al. 2002) |

| WBM | Hepatocytes | TBI | 2.2% | (Theise et al. 2000a) |

| SP | Skeletal muscle | TBI + genetic deficiency (mdx mouse) | 1–10 | (Gussoni et al. 1999) |

| KTSL | Liver | TBI + genetic deficiency (FAH) | 30–40% | (Lagasse et al. 2000) |

| Lin− Kithi | Heart/vasculature | Coronary artery ligation | 54% of new tissue | (Orlic et al. 2001) |

| SP | Cardiac muscle | TBI + coronary artery ligation | 0.02 | (Jackson et al. 2001) |

| Endothelial cells | 2–4 | |||

| Single SP | Skeletal muscle | TBI + cardiotoxin | 0.05% | |

| mdx mouse | 0.1% | (Camargo et al. 2003) | ||

| Single KTSL | Multiple | None | 0 | (Wagers et al. 2002) |

WBM, whole bone marrow; SP, side population; KTSL, KitposThy1.1l owSca‐1posLinneg l / l ow; TBI, total body irradiation.

Soon after this initial study, transplanted retrovirally marked whole bone marrow yielded exogenous retrovirally driven neomycin transcript expression in brain sections containing microglial and astroglial cells (Eglitis et al. 1999). To further support the increasing evidence for the plasticity of haematopoietic stem cells, two concurrent reports supported the view that cells derived from the haematopoietic system were differentiating into cells native to the adult brain (Brazelton et al. 2000; Mezey et al. 2000). While one team used Y‐chromosome‐marked cells, and the other GFP, both teams claimed that bone marrow cells contributed to neuronal populations in the brain.

In other studies, several groups have looked for evidence of non‐hematopoietic cell generation after transplantation in a clinical setting, either after bone marrow transplantation (Alison et al. 2000; Theise et al. 2000b; Korbling et al. 2002; Weimann et al. 2003), or after transplantation of donor tissue such as heart (Quaini et al. 2002) or liver (Theise et al. 2000b). In the case of male bone marrow donated to female patients, Y‐chromosome positive cells, also bearing markers of tissue‐specific differentiated cells, have been found in a wide variety of tissues (Table 2). In the case of hearts and livers from female donors transplanted into male patients, biopsies of the donor tissues showed that some organ‐specific cells were Y‐chromosome‐positive (Quaini et al. 2002), suggesting that circulating male host cells (presumably from the bone marrow) migrated to the transplanted tissues and participated in the regeneration process.

Table 2.

Circulating cell contribution to non‐hematopoietic tissues in clinical specimens

| Tissue transplanted | Donor cells observed | Approximate frequency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | Osteoblasts | 1.5–2% | (Horwitz et al. 1999) |

| Bone marrow | Hepatocytes | 2.2% | (Theise et al. 2000b) |

| Bone marrow | GI tract epithelia | 0–4.6% | (Okamoto et al. 2002) |

| Mobilized peripheral blood | Hepatocytes GI tract and skin epithelia | 0–7% | (Korbling et al. 2002) |

| Heart | Cardiomyocytes | 20% | (Quaini et al. 2002) |

| Endothelium | 15% | ||

| Heart | Cardiomyocytes | 0.04% | (Laflamme et al. 2002) |

| Endothelium | 25% | ||

| Heart | Cardiomyocytes | 0.2% | (Muller et al. 2002) |

| Heart | Cardiomyocytes | 0 | (Hruban et al. 1993) |

| Heart | Cardiomyocytes | 0 | (Glaser et al. 2002) |

In the bone marrow or peripheral blood transplants, male donor cells were transplanted into female recipients. In the heart transplants, female hearts were transplanted into male recipients. Donor‐derived cells in were identified by Y‐chromosome positive staining.

OTHER ADULT STEM CELLS GET INTO THE MIX

The emerging concept of adult stem cell plasticity was further supported by a report that neuronally derived stem cells could differentiate into haematopoietic tissues (Bjornson et al. 1999). Clonally derived neural stem cells from mice expressing the lacZ gene were injected into sublethally irradiated recipients. By both in vitro and in vivo assays, haematopoietic cells of donor origin were found, suggesting that a neural stem cell had transdifferentiated into a cell capable of haematopoiesis. Clonally derived neural stem cells were also shown to give rise to an astounding number of embryonic tissues when aggregated with a mouse morula or injected into a mouse‐chicken model (Clarke et al. 2000). Under these conditions, cells carrying the lacZ marker were found in ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal tissues. As well as neural stem cells, a cell population resident in skeletal muscle was found to have haematopoietic potential (Gussoni et al. 1999; Jackson et al. 1999). Cells isolated from the muscle were shown, although at lower potential, to rescue lethally irradiated mice. The growing body of data argued in favour of adult stem cells, at least under certain conditions, being a credible source of therapeutic multipotential cells.

ARE ADULT STEM CELLS TRULY MULTIPOTENTIAL?

The implication of the studies described above was that, if the efficiency of non‐hematopoietic engraftment were sufficiently high, bone marrow transplantation could potentially be used to treat a wide variety of non‐hematopoietic diseases. This concept was particularly attractive when considering diseases such as muscular dystrophy, where the affected tissue is disseminated throughout the body and haematopoietic stem cell transplantation offered the possibility to systemically treat any tissue served by the circulation.

However, the initial reports on the plasticity of somatic stem cells, although tantalizing, were in general merely descriptive in nature. Thus, none of these reports clearly indicated a potential biological mechanism that explained the occurrence of these phenomena, nor did any of them identify the cell types directly involved in the ‘change‐of‐fate’ process. While these might appear purely scientific questions, the basic knowledge behind these processes could serve as the foundation to improve their efficiency prior to therapeutic use. In the last 2 years, more rigorous studies aimed at establishing a mechanistic basis for ‘plasticity’ have surprisingly demonstrated that the phenomenon of stem cell ‘transdifferentiation’ might be explained by either cell contamination, or random cellular fusion between donor and endogenous cell types.

BLOOD FROM NON‐HAEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELLS: CONTAMINATION, NOT TRANSDIFFERENTIATION

The first report challenging stem cell plasticity came in response to the original studies claiming muscle‐to‐blood transdifferentiation (Gussoni et al. 1999; Jackson et al. 1999). In this case, it was demonstrated that the haematopoietic activity found in cells derived from adult skeletal muscle results from bona fide haematopoietic stem cells resident in skeletal muscle tissue (Kawada & Ogawa 2001; McKinney‐Freeman et al. 2002). In a very elegant study, McKinney‐Freeman and colleagues determined that, within muscle, only cells expressing the haematopoietic specific marker, CD45, and the HSC antigen, Sca‐1, could give rise to blood upon a transplant (McKinney‐Freeman et al. 2002). Further work has shown that muscle‐derived HSCs are constantly being recruited from the bone marrow, and thus they represent traditional haematopoietic stem cells that have a transitory presence in skeletal muscle (Geiger et al. 2002; McKinney‐Freeman et al. 2003). Therefore, these studies, along with the finding that HSCs are in frequent flux with the circulation (Wright et al. 2001), and that HSCs can reside in several non‐hematopoietic tissues (Asakura & Rudnicki 2002), strongly suggested that the haematopoietic fate of non‐hematopoietic cell types could be due to contamination of tissue‐specific cell preparations with itinerant bona fide HSCs.

CELL FUSION AS A MECHANISM FOR HAEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELL TRANSDIFFERENTIATION

Similar studies have cast doubt on the ability of bone marrow cells to become brain, liver, or skeletal muscle. One initial study tested the ability of single physically isolated HSCs to contribute not only to blood but also to several non‐hematopoietic tissues. Looking in uninjured tissues (Wagers et al. 2002), the authors found no evidence of single HSC‐derived engraftment, except exceedingly rare donor‐derived hepatocytes and neurones. Another similar clonal study found evidence, albeit at very low frequencies, of haematopoietic contribution to skeletal muscle, only after severe myotoxic injury (Camargo et al. 2003). In both of these papers, in contrast to the minimal non‐hematopoietic contribution, blood engraftment by a single HSC reached levels up to 80% (Camargo et al. 2003). These data indicate that HSC transdifferentiation into non‐blood lineages is extremely rare and might represent a non‐physiological stochastic event.

In support of this hypothesis, recent data suggest that bone marrow (BM)‐derived cells do not transdifferentiate into other cell types, but they instead fuse with endogenous tissue‐specific cells. The idea that HSCs could be fusing to other cell types, resulting in cells with a new phenotype and function, was supported by two papers that demonstrated that fusion of adult cells with embryonic stem cells in vitro could lead to functional cells with pluripotential properties (Terada et al. 2002; Ying et al. 2002). In some tissues, such as muscle where fusion is a natural step in the regeneration of the tissue, the hypothesis of random fusion between donor‐derived and host cells is difficult to test. However, elegant work has recently demonstrated that in the liver, brain, and heart, fusion of haematopoietic cells and tissue‐specific host cells seems to be the main mechanism of generation of ‘transdifferentiated’ cells from bone marrow (Alvarez‐Dolado et al. 2003; Vassilopoulos et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2003).

HAEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELLS GENERATE NON‐HEMATOPOIETIC TISSUES THROUGH MYELOID CELL INTER‐MEDIATES

Even after the demonstration of fusion, it was thought that donor‐derived HSC were the cells that directly fused with the host tissues. However, several observations led us to believe that haematopoietic progeny of HSC, and not the stem cells themselves, were the cells responsible for cellular fusion. First, in the majority of published studies, haematopoietic engraftment in the host was required before any non‐hematopoietic contribution was observed. Secondly, when bone marrow HSC are directly injected into the muscle (Camargo and Goodell, unpublished data) or liver (Wang et al. 2002), they fail to engraft into these tissues. Finally, experimental models of plasticity usually require severe tissue injury, resulting in extensive recruitment of inflammatory leucocytes. Thus, we hypothesized that circulating mature haematopoietic cells served as intermediates in the generation of other tissues. Haematopoietic‐derived macrophages were an optimal candidate for this process, as they are particularly suited to respond to inflammatory cues, extravasate, and take up residence in many non‐hematopoietic tissues. Furthermore, macrophages have the ability to fuse among themselves and other cell types (Vignery 2000). Utilizing a genetic‐based lineage tracing strategy to follow the progeny of macrophages in vivo, we provided evidence that the BM cells giving rise to both muscle and liver were indeed differentiated cells of the myeloid lineage, macrophages and granulocytes (Camargo et al. 2003; Camargo and Goodell, submitted). We also showed that this contribution does not occur through either muscle‐ or liver‐specific stem cells, but through direct fusion with tissue‐specific host cells (Camargo et al. 2003; Camargo and Goodell, submitted).

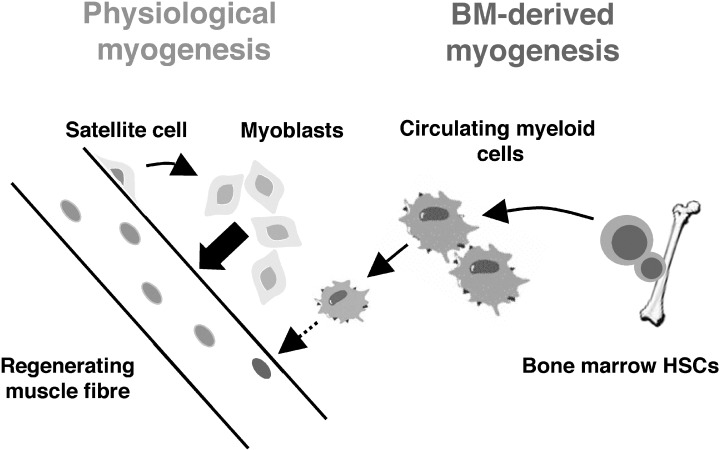

Taken together, the findings described above have led us to postulate a model that could mechanistically explain most of the previous observations of plasticity. Taking the bone marrow‐to‐muscle conversion as an example, the model is shown in Fig. 1. Transplanted HSCs home to the bone marrow of recipients and establish multilineage haematopoiesis, one of these lineages being the myeloid one. Circulating myeloid cells, in response to muscle injury, are recruited to the site of damage and function as inflammatory cells. Exclusively amidst a regenerative and active fusogenic milieu, a very small number of infiltrating cells randomly become incorporated into a growing mature myofibre, bypassing pre‐specification to a myogenic fate. Once fused, myogenic transcription factors expressed in trans from neighbouring nuclei activate a myogenic program in the HSC‐derived nucleus. Figure 1 also emphasizes the differences between bone marrow‐derived and traditional myogenesis. Whereas the latter occurs through genetically specified mononuclear muscle stem cell intermediates and mediates robust levels of contribution, the former does not involve a tissue‐specific stem cell and achieves insignificant levels of engraftment.

Figure 1.

Model for the mechanism of bone marrow‐derived myogenesis. HSC from bone marrow produce circulating myeloid cells. In response to muscle injury, these cells are recruited to the site of damage and function as inflammatory cells. Amidst a regenerative and active fusogenic milieu, a very small number of infiltrating cells randomly become incorporated into a growing mature myofibre. The scheme also emphasizes the differences between bone marrow‐derived and traditional myogenesis. Whereas the latter occurs through genetically specified mononuclear muscle stem cell intermediates and mediates robust levels of contribution, the former does not involve a tissue‐specific stem cell and achieves insignificant levels of engraftment.

THERAPEUTIC POTENTIAL

Considering the inefficiency of adult HSC to give rise to non‐hematopoietic tissues, is it wise to think about using haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for therapy of non‐hematopoietic disease? Clinical trials are underway in several countries to determine whether bone marrow stem cells could produce cardiomyocytes de novo after infarction, either by direct injection of bone marrow cells into the heart, or by mobilization through the circulation. The recent discoveries reviewed above call into question this rationale and call for a re‐evaluation of both basic and pre‐clinical observations. However, even though HSC might not physiologically contribute to the regeneration of other tissues, in some cases they might be able to promote repair by providing growth and survival factors, as has recently been shown (Hess et al. 2003).

What about using HSC transplantation for diseases such as those affecting the liver? One of the most impressive examples of cell ‘conversion’ in the mouse has been the generation of hepatocytes from bone marrow stem cells (Lagasse et al. 2000). These experiments were particularly effective because there was an extraordinary selection for wild‐type cells that functioned as hepatocytes. The host hepatocytes harboured a severe genetic defect (fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase deficiency), enabling selection for wild‐type hepatocytes after withdrawal of a supportive drug regimen. The selection occurred over a period of a few weeks, during which the mouse was sickened due to lower liver function, but never at acute risk of death. In this way, the host hepatocytes experience a controlled demize, giving time for expansion of engrafting wild‐type cells derived from bone marrow. Therefore, for such a conversion to work in humans, a strong selective pressure that does not put the host at risk of death must be devised. Such a selective pressure would probably have to be specific for the target tissue – taking into account the natural turnover and structure of the tissue, and the risks inherent to the specific disease being treated.

The discovery that cell fusion between macrophages and different tissues occurs in vivo could be the basis of new cell or gene therapy approaches. Although the baseline levels for these events seem to be extremely low, as mentioned above, if the donor heterokaryons have a strong selective advantage, therapeutic re‐population could be achieved. Further work aimed at understanding the molecular basis of cell fusion could allow us to enhance this process for therapeutic use.

FUTURE ALTERNATIVE ADULT STEM CELL THERAPIES

In light of the recent data, HSCs and tissue‐specific adult stem cells appear for the most part to be lineage restricted in their differentiation programmes as previously believed. This does not, however, necessarily eliminate their utility for cell therapy. In fact, adult stem cells may be prime candidates for therapy when tissue specificity is of the utmost importance. In addition, several alternative stem cells have recently been proposed for practical applications in gene and tissue therapy. Such examples reviewed briefly below include the mesoangioblast (Sampaolesi et al. 2003), muscle‐derived stem cells (MDSCs) (Lee et al. 2000), and the multipotent adult progenitor cell (MAPC) (Jiang et al. 2002).

The mesoangioblast, a vessel‐associated stem cell has recently been shown to restore function in dystrophic mice lacking the δ‐sarcoglycan protein (Sampaolesi et al. 2003). Under culture conditions, these clonally derived cells express CD34, c‐Kit, and Flk‐1, and upon injection of wild type cells, muscle architecture and α‐sarcoglycan expression were partially restored. A hallmark of any stem cell therapy should be morphological and functional restoration of the target tissue. These authors, for the first time, showed a significant functional improvement in the pathology of this mouse strain using a wide variety of physiological tests (Sampaolesi et al. 2003). However, as these cells are derived from fetal tissue, these cells may be difficult to identify and purify on the basis of marker expression for use in adult humans.

MDSCs, isolated clonally by a collagen pre‐plate technique, have been shown to be Sca‐1+, Flk‐1+, c‐Kit−, CD45−, lineage− as well as expressing muscle specific markers such as desmin, myogenin and MyoD (Cao et al. 2003). These cells have properties of both HSC and myoblasts and purported to support regeneration of blood, muscle, and bone (Lee et al. 2000). MDSCs have recently been investigated with limited success as a muscle‐specific gene therapy delivery method of the mini‐dystrophin gene in mice, although functional rescue of muscular dystrophy was not achieved. As the MDSCs have only been purified from mice, it is currently unknown if a human equivalent of this population can be isolated.

MAPCs are a third extensively studied and reportedly multipotential adult stem cell (Jiang et al. 2002). MAPCs have been shown in vitro under defined culture conditions to differentiate into endothelium, neuroectoderm, and endoderm. When transplanted into 3.5‐day‐old mouse blastocysts, chimeric mice were generated exhibiting incorporation of MAPCs of up to 45%, suggesting that MAPCs have a similar potential to ES cells to differentiate into all three germ layers. Injections into the nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) model yielded engraftment in several previously established stem cell niches including bone marrow, spleen, and intestine, as well as engraftment in lung epithelium and the blood. One drawback that has slowed the use of these cells is the unusual culture conditions required to give rise to MAPCs. The cells must be cultured for long periods of time at specific densities to obtain clones with full differentiation potential. This suggests that epigenetic changes may be occurring in the cells which change their properties, making them more multipotent. Also, still needed is a method to isolate MAPCs from fresh tissue, once markers for their purification have been established.

These potentially multitalented adult stem cells have generated a great deal of excitement. In the next few years, other labs will need to derive the cells and demonstrate that their properties are reproducible.

CONCLUSIONS

In the weeks before the Bush decision to allow NIH‐funded research on some human embryonic stem cell lines, the lay press and anti‐embryonic stem (ES) cell research groups were claiming that adult and embryonic stem cells had a similar developmental potential. Such arguments are still being employed by these groups to persuade politicians to block funding for the ethically controversial ES cells. As described above, work over the past 2 years has convincingly demonstrated that adult stem cells will not replace ES cells. Both cell types are inherently different, and both have advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, further research is necessary for the development of both cell types in order to solve fundamental issues currently limiting their widespread use. Even if adult stem cells cannot ‘transdifferentiate’ into diverse tissue types, they could be extremely useful for regeneration of their host tissue. Having as a paradigm the haematopoietic stem cell, whose transplantation has saved thousands of lives worldwide, work with tissue‐specific stem cells holds great promise for the treatment of multiple degenerative diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FDC was a fellow of the American Liver Foundation. MAG is a scholar of the Leukaemia and Lymphoma Society.

REFERENCES

- Alison M, Sarraf C (1998) Hepatic stem cells. J. Hepatol. 29, 676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alison MR, Poulsom R, Jeffery R, Dhillon AP, Quaglia A, Jacob J, Novelli M, Prentice G, Williamson J, Wright NA (2000) Hepatocytes from non‐hepatic adult stem cells. Nature 406, 257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez‐Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia‐Verdugo JM, Fike JR, Lee HO, Pfeffer K, Lois C, Morrison SJ, Alvarez‐Buylla A (2003) Fusion of bone‐marrow‐derived cells with purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature 425, 968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, Kalka C, Pastore C, Silver M, Kearne M, Magner M, Isner JM (1999) Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ. Res. 85, 221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura A, Rudnicki MA (2002) Side population cells from diverse adult tissues are capable of in vitro hematopoietic differentiation. Exp. Hematol. 30, 1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornson CRR, Rietze RL, Reynolds BA, Magli MC, Vescovi AL (1999) Turning brain into blood: a hematopoietic fate adopted by adult neural stem cells in vivo . Science 283, 534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazelton TR, Rossi FM, Keshet GI, Blau HM (2000) From marrow to brain: expression of neuronal phenotypes in adult mice. Science 290, 1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo FD, Green R, Capetenaki Y, Jackson KA, Goodell MA (2003) Single hematopoietic stem cells generate skeletal muscle through myeloid intermediates. Nat. Med. 9, 1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao B, Zheng B, Jankowski RJ, Kimura S, Ikezawa M, Deasy B, Cummins J, Epperly M, Qu‐Petersen Z, Huard J (2003) Muscle stem cells differentiate into haematopoietic lineages but retain myogenic potential. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro RF, Jackson KA, Goodell MA, Robertson CS, Liu H, Shine HD (2002) Failure of bone marrow cells to transdifferentiate into neural cells in vivo . Science 297, 1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke DL, Johansson CB, Wilbertz J, Veress B, Nilsson E, Karlstrom H, Lendahl U, Frisen J (2000) Generalized potential of adult neural stem cells. Science 288, 1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousin B, Andre M, Arnaud E, Penicaud L, Casteilla L (2003) Reconstitution of lethally irradiated mice by cells isolated from adipose tissue. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301, 1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglitis MA, Mezey E (1997) Hematopoietic cells differentiate into both microglia and macroglia in the brains of adult mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglitis MA, Dawson D, Park KW, Mouradian MM (1999) Targeting of marrow‐derived astrocytes to the ischemic brain. Neuroreport 10, 1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari G, Cusella‐De Angelis G, Coletta M, Paolucci E, Stornaiuolo A, Cossu G, Mavilio F (1998) Muscle regeneration by bone marrow‐derived myogenic progenitors. Science 279, 1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage FH, Ray J, Fisher LJ (1995) Isolation, characterization, and use of stem cells from the CNS. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger H, True JM, Grimes B, Carroll EJ, Fleischman RA, Van Zant G (2002) Analysis of the hematopoietic potential of muscle‐derived cells in mice. Blood 100, 721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Lu MM, Narula N, Epstein JA (2002) Smooth muscle cells, but not myocytes, of host origin in transplanted human hearts. Circulation 106, 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gussoni E, Soneoka Y, Strickland CD, Buzney EA, Khan MK, Flint AF, Kunkel LM, Mulligan RC (1999) Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse restored by stem cell transplantation. Nature 401, 390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess D, Li L, Martin M, Sakano S, Hill D, Strutt B, Thyssen S, Gray DA, Bhatia M (2003) Bone marrow‐derived stem cells initiate pancreatic regeneration. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Fitzpatrick LA, Koo WW, Gordon PL, Neel M, Sussman M, Orchard P, Marx JC, Pyeritz RE, Brenner MK (1999) Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat. Med. 5, 309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruban RH, Long PP, Perlman EJ, Hutchins GM, Baumgartner WA, Baughman KL, Griffin CA (1993) Fluorescence in situ hybridization for the Y‐chromosome can be used to detect cells of recipient origin in allografted hearts following cardiac transplantation. Am. J. Pathol. 142, 975. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KA, Majka SM, Wang H, Pocius J, Hartley CJ, Majesky MW, Entman ML, Michael LH, Hirschi KK, Goodell MA (2001) Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J. Clin. Invest. 107, 1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KA, Mi T, Goodell MA (1999) Hematopoietic potential of stem cells isolated from murine skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, Schwartz RE, Keene CD, Ortiz‐Gonzalez XR, Reyes M, Lenvik T, Lund T, Blackstad M, Du J, Aldrich S, Lisberg A, Low WC, Largaespada DA, Verfaillie CM (2002) Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature 418, 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada H, Ogawa M (2001) Bone marrow origin of hematopoietic progenitors and stem cells in murine muscle. Blood 98, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbling M, Katz RL, Khanna A, Ruifrok AC, Rondon G, Albitar M, Champlin RE, Estrov Z (2002) Hepatocytes and epithelial cells of donor origin in recipients of peripheral‐blood stem cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarge MA, Blau HM (2002) Biological progression from adult bone marrow to mononucleate muscle stem cell to multinucleate muscle fiber in response to injury. Cell 111, 589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme MA, Myerson D, Saffitz JE, Murry CE (2002) Evidence for cardiomyocyte repopulation by extracardiac progenitors in transplanted human hearts. Circ Res. 90, 634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagasse E, Connors H, Al‐Dhalimy M, Reitsma M, Dohse M, Osborne L, Wang X, Finegold M, Weissman IL, Grompe M (2000) Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo . Nat. Med. 6, 1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Qu‐Petersen Z, Cao B, Kimura S, Jankowski R, Cummins J, Usas A, Gates C, Robbins P, Wernig A, Huard J (2000) Clonal isolation of muscle‐derived cells capable of enhancing muscle regeneration and bone healing. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney‐Freeman SL, Jackson KA, Camargo FD, Ferrari G, Mavilio F, Goodell MA (2002) Muscle‐derived hematopoietic stem cells are hematopoietic in origin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney‐Freeman SL, Majka SM, Jackson KA, Norwood K, Hirschi KK, Goodell MA (2003) Altered phenotype and reduced function of muscle‐derived hematopoietic stem cells. Exp. Hematol. 31, 806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey E, Chandross KJ, Harta G, Maki RA, McKercher SR (2000) Turning blood into brain: cells bearing neuronal antigens generated in vivo from bone marrow. Science 290, 1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P, Pfeiffer P, Koglin J, Schafers HJ, Seeland U, Janzen I, Urbschat S, Bohm M (2002) Cardiomyocytes of noncardiac origin in myocardial biopsies of human transplanted hearts. Circulation 106, 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto R, Yajima T, Yamazaki M, Kanai T, Mukai M, Okamoto S, Ikeda Y, Hibi T, Inazawa J, Watanabe M (2002) Damaged epithelia regenerated by bone marrow‐derived cells in the human gastrointestinal tract. Nat. Med. 8, 1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, Pickel J, McKay R, Nadal‐Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P (2001) Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature 410, 701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaini F, Urbanek K, Beltrami AP, Finato N, Beltrami CA, Nadal‐Ginard B, Kajstura J, Leri A, Anversa P (2002) Chimerism of the transplanted heart. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaolesi M, Torrente Y, Innocenzi A, Tonlorenzi R, D’antona G, Pellegrino MA, Barresi R, Bresolin N, De Angelis MG, Campbell KP, Bottinelli R, Cossu G (2003) Cell therapy of α‐sarcoglycan null dystrophic mice through intra‐arterial delivery of mesoangioblasts. Science 301, 487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz. E, McCormick KM (1994) Skeletal muscle satellite cells. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 123, 213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LG, Weissman IL, Heimfeld S (1991) Clonal analysis of hematopoietic stem‐cell differentiation in vivo . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada N, Hamazaki T, Oka M, Hoki M, Mastalerz DM, Nakano Y, Meyer EM, Morel L, Petersen BE, Scott EW (2002) Bone marrow cells adopt the phenotype of other cells by spontaneous cell fusion. Nature 416, 542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theise ND, Badve S, Saxena R, Henegariu O, Sell S, Crawford JM, Krause DS (2000a) Derivation of hepatocytes from bone marrow cells in mice after radiation‐induced myeloablation. Hepatology 31, 235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theise ND, Nimmakayalu M, Gardner R, Illei PB, Morgan G, Teperman L, Henegariu O, Krause DS (2000b) Liver from bone marrow in humans. Hepatology. 32, 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma JG, Akhavan M, Fernandes KJ, Barnabe‐Heider F, Sadikot A, Kaplan DR, Miller FD (2001) Isolation of multipotent adult stem cells from the dermis of mammalian skin. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilopoulos G, Wang PR, Russell DW (2003) Transplanted bone marrow regenerates liver by cell fusion. Nature 422, 901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignery A (2000) Osteoclasts and giant cells: macrophage‐macrophage fusion mechanism. Int. J. Exp Pathol. 81, 291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagers AJ, Sherwood RI, Christensen JL, Weissman IL (2002) Little evidence for developmental plasticity of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Science 297, 2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Montini E, Al‐Dhalimy M, Lagasse E, Finegold M, Grompe M (2002) Kinetics of liver repopulation after bone marrow transplantation. Am. J. Pathol. 161, 565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Willenbring H, Akkari Y, Torimaru Y, Foster M, Al‐Dhalimy M, Lagasse E, Finegold M, Olson S, Grompe M (2003) Cell fusion is the principal source of bone‐marrow‐derived hepatocytes. Nature 422, 823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt FM (1998) Epidermal stem cells: markers, patterning and the control of stem cell fate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 353, 831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimann JM, Charlton CA, Brazelton TR, Hackman RC, Blau HM (2003) Contribution of transplanted bone marrow cells to purkinje neurons in human adult brains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman IL (2000) Stem cells: units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution. Cell 100, 157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welm BE, Tepera SB, Venezia T, Graubert TA, Rosen JM, Goodell MA (2002) Sca‐1(pos) cells in the mouse mammary gland represent an enriched progenitor cell population. Dev. Biol. 245, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DE, Wagers AJ, Gulati AP, Johnson FL, Weissman IL (2001) Physiological migration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Science 294, 1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying QL, Nichols J, Evans EP, Smith AG (2002) Changing potency by spontaneous fusion. Nature 416, 545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]