Abstract

Abstract. Telomere length plays an important role in regulating the proliferative capacity of cells, and serves as a marker for cell cycle history and also for their remaining replicative potential. Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) are known to be a significant cell source for therapeutic intervention and tissue engineering. To investigate any possible limitations in the replicative potential and chondrogenic differentiation potential of fibroblast growth factor‐2‐expanded MSCs (FGF(+)MSC), these cells were differentiated at various population doublings (PDs), and telomere length and telomerase activity were measured before and after differentiation. FGF(+)MSC cultured at a relatively low density maintained proliferation capability past more than 80 PD and maintained chondrogenic differentiation potential up to at least 46 PD and long telomeres up to 105 PD, despite expressing low levels of telomerase activity. Interestingly, upon chondrogenic differentiation of these cells, telomeres showed a remarkable reduction in length. This shortening was more extensive when FGF(+)MSC of higher PD levels were differentiated. These findings suggest that telomere length may be a useful genetic marker for chondrogenic progenitor cells.

INTRODUCTION

Situated at the end of each chromatid of eukaryotic chromosomes is a telomere, a repetitive DNA sequence, ‘TTAGGG’, which shortens during chromosomal replication because of the end‐replication problem (Wellinger et al. 1996). This phenomenon is thought to act as a ‘mitotic clock’, limiting a cell's replicative capacity (Harley et al. 1990; Hornsby 2002; Wright & Shay 2002). Cells that frequently self‐renew such as haematopoietic stem cells and mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC), even if their donors are young, show cellular ageing as a result of telomere shortening after cell passage (Vaziri et al. 1994; Baxter et al. 2004). However, in immortal cells such as cancer cells, telomere length is maintained mainly by activity of the enzyme telomerase, a reverse transcriptase, using a specific RNA template, hTR (human telomere RNA component, Feng et al. 1995; Hiyama & Hiyama 2002).

MSCs are well known to be capable of replicating as undifferentiated cells whereas retaining multi‐lineage differentiation potential, and are therefore a potentially useful cell source for repair of damaged tissue. The use of MSC‐based tissue repair in clinical research is already underway (Pittenger et al. 1999; Deans & Moseley 2000; Caplan & Bruder 2001; Jiang et al. 2002). To use MSC for clinical application, it is necessary to expand a large number of cells, and MSCs have already been expanded successfully under standard culture conditions (Jaiswal et al. 1997; Johnstone et al. 1998; Deng et al. 2001; Le Blanc et al. 2004). However, under these conditions, the expanded cells lose some degree of proliferation capacity and differentiation potential (Digirolamo et al. 1999; Sekiya et al. 2001). Recently, during replication in monolayer culture in vitro, fibroblast growth factor‐2 (FGF‐2) has been shown to increase the life span and preserve the differentiation potential of human MSC (Tsutsumi et al. 2001), suggesting that monolayer expansion using FGF‐2 may be useful for supplying MSC for clinical application.

The present study has set out to investigate telomere length and telomerase activity of FGF‐2‐expanded human MSC (FGF(+)MSC) with increasing population doubling (PD) levels in monolayer cultures, and to elucidate the relation between population doubling levels, telomere length and chondrogenic differentiation potentials. Telomere length and telomerase activity of the cells were measured then re‐measured after chondrogenic differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

MSCs were isolated from bone marrow aspirates of 15 normal human donors (6 men, from 16 to 45 years of age (average: 24.5‐years old); 9 women, from 14 to 42 years of age (average: 28.2 years old)) with informed consent, in accordance with the standards of the ethical committee of Hiroshima University and the Helsinki Declarations of 1995, during operations for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction of the knee. Aspirates were cultured in high‐glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 15% heat‐inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and antimicrobial agents. On reaching confluence, the cells were harvested with trypsin, and seeded in fresh medium at a density of 2 × 105 cells per 100‐mm plate (BD Biosciences, Falcon). After confirming cell adhesion, MSCs were cultured with or without FGF‐2 (final concentration; 1 ng/ml, R & D Systems Inc. Minneapolis, USA). On reaching confluence again, the cells were reseeded under the same conditions.

Chondrocytes were isolated by digesting macroscopically healthy adult cartilage, obtained with informed consent, by collagenase digestion, during operations for total knee arthroplasty, and were cultured at a density of 2 × 105 cells per 100‐mm plate with 10% FBS‐DMEM containing 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid‐2‐phosphate sesquimagnesium salt (Sigma). Saos‐2 cells (human osteosarcoma cells) were kindly provided by Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Tohoku University, as telomerase‐positive cells. These cells were cultured in 10% FBS‐RPMI1640 (Invitrogen). On reaching confluence, the cells were harvested with trypsin, and were seeded in fresh medium at a density of 2 × 105 cells per 100‐mm plate. All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Chondorogenic differentiation

Chondrogenic differentiation potential of early and late passaged FGF(+)MSC and early‐passaged FGF(–)MSC was investigated. A modified version of Johnstone's pellet culture system (Johnstone et al. 1998) was used to induce chondrogenesis. MSC (106 cells) were placed in a 15‐ml polypropylene tube (Greiner BioOne, Frickenhausen, Germany) and were centrifuged to form a pellet. The pellet was cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 in 1 ml of chondrogenic medium containing high‐glucose DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 ng/ml transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β3 (Sigma), 10−7 M dexamethasone (Sigma), 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid‐2‐phosphate sesquimagnesium salt (Sigma), 40 µg/ml l‐proline (Nacalai tesque, Kyoto, Japan), ITS‐A supplement (Invitrogen; 10 µg/ml insulin, 6.7 ng/ml sodium selenite, 5.5 µg/ml transferrin, 110 µg/ml sodium pyruvate), and 1.25 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma). As a negative control, MSCs were cultured under similar conditions, but TGF‐β3 and dexamethasone were not added to the medium. The media were changed every 3–4 days.

Evaluation of chondrogenesis

After 21 days in pellet culture, the pellet tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and were embedded in paraffin wax. Then sections were cut at 5 µm by microtome (Yamato Kohki Industrial Co., Japan). The sections were evaluated by both histological staining (toluidine blue) and immunohistochemical analysis (type II collagen). For immunohistochemistry, after de‐paraffinization, the sections were permeabilized with Proteinase K (Dako Cytomation Co. Kyoto, Japan) in 0.1% Tween‐20 in phosphate buffer saline (PBS)(–) and were left for 5 min at room temperature. To avoid nonspecific reactions, the prepared specimens were treated with Histofine® blocking reagent (Nichirei Co., Tokyo, Japan). Specimens were then treated with antihuman type II collagen polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., CA, USA) raised in goat at a final concentration of 1 µg/ml in 3% BSA (Sigma) in PBS without calcium or magnesium (PBS(–)) at 4 °C overnight in a humidified atmosphere. Biotin‐labelled antigoat secondary antibody (Nichirei) was applied for 10 min at 25 °C, followed by alkaline phosphatase‐labelled streptavidin (Nichirei) treatment for 10 min. Specimens were incubated with alkaline phosphatase substrate solution (colour development: fast red, Nichirei) for 20 min at 25 °C, and nuclei were counterstained with haematoxylin. The specimens were examined by light microscopy (Nicon). Negative controls were treated following the same procedure, except that the primary antibody was omitted.

Determination of telomere length

Telomere length of early and late‐passaged FGF(+)MSC, early‐passaged FGF(–)MSC and normal chondrocytes was measured by Southern blot analysis as previously described (Hiyama et al. 1992; Hiyama et al. 1995a; Tatsumoto et al. 2000). After chondrogenic differentiation, telomere length of FGF(+)MSC and FGF(–)MSC was re‐measured. Genomic DNA of 106 cells was extracted by DNA Extractor WB kit (Wako). Extracted DNA was completely digested with the restriction enzyme Hinf I to measure the length of terminal restriction fragments (TRFs). Digested DNA 2 µg/lane was loaded onto a 0.6 or 0.8% agarose gel, and was electrophoresed at 46 V/cm for 18 h together with 1 kb DNA ladder and lamda DNA/Hind III digest as size markers. DNA was denatured by soaking gels in 0.2 N NaOH/0.6 m NaCl for 25 min, and was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Optitran BA‐S 85, Schleicher & Schuel, Keene, USA). DNA was prehybridized with denatured salmon sperm DNA (Wako) at 65 °C, and hybridized in 10× modified Denhart solution, 1 m NaCl, 50 mm Tris‐HCl pH 7.4, 10 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate and 50 µg/ml denatured salmon sperm DNA at 50 °C with 5′‐end [32P]‐labelled (TTAGGG)4 (Takara bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). Membranes were washed in 4 × SSC (0.6 m NaCl, 0.06 m sodium citrate, pH 7.0)/0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate at 55 °C and the signals were measured by Bioimage analyser, BAS‐2000 (Fujifilm, Kanagawa, Japan); peaks of signals were estimated as lengths of TRFs.

Telomerase activity analysis

Telomerase activity was measured by the telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay as described earlier (Kim et al. 1994; Hiyama et al. 1995b; Hiyama et al. 2004). FGF(+)MSC or FGF(–) MSC (105 cells) were homogenized in CHAPS lysis buffer and an aliquot of the extract containing 0.5 µg of protein was used for each assay. The assay was performed using a commercial kit, TRAPeze XL kit (Serological Co, Gaithersbrug, MD), which provides a quantitative fluorescent‐labelled polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system for estimation of relative telomerase activity, using a PCR internal control as previously described (Hiyama et al. 2004). The PCR products were measured in a fluorescent plate reader (Wallac, Perkin‐Elmer, Wellesle, MA).

RESULTS

Effect of FGF‐2 on cell proliferation and cell morphology of MSC

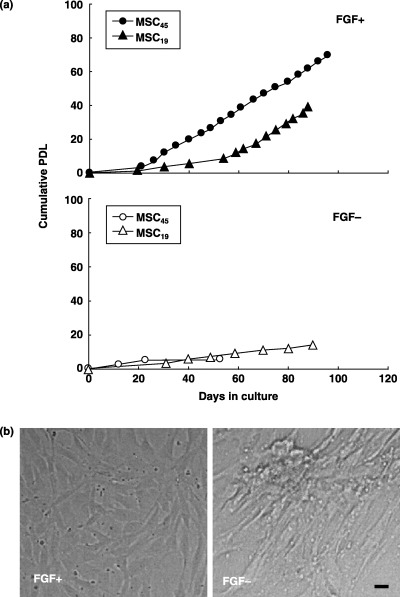

We have been able to culture FGF(+)MSC45 populations for more than 60 PD, in which period the cells proliferated at a rate of 4 PD every 4 days (Fig. 1a). FGF(+)MSC19 proliferated gradually until day 54 after culture. Subsequently, the cells proliferated at the same rate as FGF(+)MSC45 (Fig. 1a). Cells that had a high proliferation rate similar to FGF(+)MSC45 were observed in two other donors (FGF(+)MSC14 and FGF(+)MSC17; in the case of FGF(+)MSC14, the cells proliferated up to 69 PD by day 111 after culture; in the case of FGF(+)MSC17, the cells proliferated up to 88 PD by day 127 after culture; these cells proliferated at a rate of 4 PD every 4 days). In addition, FGF(+)MSC appeared uniformly spindle shaped (Fig. 1b, FGF+) from 8 PD and continued to exhibit this morphology past 60 PD. In contrast, FGF(–)MSC19 showed proliferation for 19 PD, dividing at a rate of only 2 PD every 10 days. FGF(–)MSC45 achieved only 5 PD (Fig. 1a). Morphologically, FGF(–)MSC were almost polygonal in shape (Fig. 1b, FGF−).

Figure 1.

Cell proliferation and morphological aspects. (a) Proliferation curve of FGF(+)MSC or FGF(–)MSC from MSC19 and 45 (donor age, 19 and 45 years old, respectively). MSCs were isolated from bone marrow aspirates of normal adult donors. After confirming cell adhesion to the plate, MSCs were cultured with 15% FBS‐DMEM with or without FGF‐2 (final conc.; 1 ng/ml). Cumulative population doublings level (PDL) is regarded as zero for culture starting immediately after the primary culture of cells, and calculated to increase according to the equation: log2{(the number of collected cells)/(the number of seeded cells)}. (b) Representative morphological aspects. FGF+; cells cultured with media including FGF‐2, FGF−; without FGF‐2. The scale indicates 5 µm.

FGF‐2‐expanded MSC retain chondrogenic potential

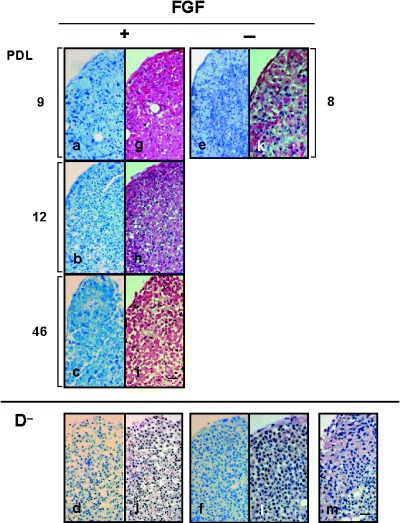

Next, we investigated the chondrogenic potential of FGF(+)MSC and FGF(–)MSC. Pellets containing FGF(+)MSC differentiated after 9, 12 and 46 PD had weak metachromasia when stained with toluidine blue, but interestingly, immunohistochemical analysis showed that type II collagen was exhibited in the circumference of the pellets (Fig. 2a,b,c; g,h,i). Additionally, FGF(–)MSC differentiated after 8 PD showed similar staining (Fig. 2e; k). In contrast, control pellets, cultured in medium not including TGF‐β3 or dexamethasone, containing FGF(+)MSC differentiated after 10 PD and FGF(–)MSC differentiated after 7 PD, scarcely had metachromasia by toluidine blue staining, and type II collagen was also only faintly exhibited (Fig. 2d,j; f,l).

Figure 2.

Representative microscopic views of chondrogenesis of MSC. The pellet tissue was evaluated by toluidine blue stain (a–f) and immunohistochemical analysis (type II collagen; g–m). FGF(+) MSC‐derived pellet: 9, 12 and 46 PD: (a, g) (b, h) and (c, i), respectively. FGF(–)MSC‐derived pellet: 8 PD (e, k). D−: control, chondrogenic differentiation media not including TGF‐β3 or dexamethasone. FGF(+)MSC‐derived:10 PD (d, j). FGF(–)MSC‐derived: 7 PD (f, l). Negative control for immunohistochemical analysis (m). Magnification was 200‐fold. The scale indicates 50 µm.

FGF‐2‐expanded MSC retained long telomeres; chondrogenic differentiation caused telomere length to be shorter

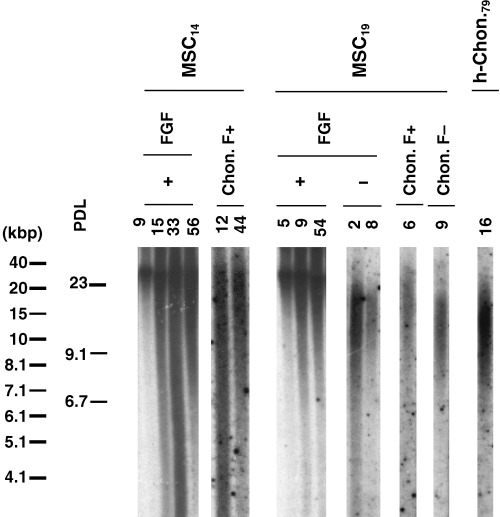

Telomere length of FGF(+)MSC was measured by Southern blot analysis before and after chondrogenic differentiation. We found that FGF(+)MSC maintained relatively long telomeres (approximately 30 kbps) regardless of increasing PD level (Fig. 3, Table 1; MSC14, MSC19 and MSC45, FGF+). Telomeres of FGF(+)MSC17 and FGF(+)MSC45 were of similar length to those of MSC14 and MSC19 (data not shown). In particular, FGF(+)MSC17 maintained long telomeres up to 105 PD (data not shown). Interestingly, upon differentiation, the cells showed remarkably shortened telomeres (under approximately 20 kbps; Fig. 3, Table 1; MSC14, 19 and 45, Chon. F+). This shortening was more extensive when FGF(+)MSC of higher PD levels were differentiated (Fig. 3, Table 1; MSC14, Chon. F+). In contrast, early passage undifferentiated FGF(–)MSC19 cells showed relatively low lengths (under approximately 17 kbps). At increased PD levels, FGF(–)MSC telomere lengths appeared shorter (Fig. 3, Table 1; MSC19).

Figure 3.

Effect of FGF‐2 on telomere length of MSC. Telomere length was measured by Southern blot analysis. MSC14 and 19: donor age, 14 and 19 years old. h‐Chon79: human chondrocytes, 79 years old. Chon. F+ or Chon. F−; chondrogenesis of FGF(+)MSC or FGF(–)MSC.

Table 1.

Effect of FGF‐2 on TRF length and telomerase activity of MSC

| Property | PDL | TRF length (Kb) | Telomerase activity (TPG) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSC14 | ||||

| FGF+ | 9 | 33.4 | 4.39 | |

| 15 | 32.5 | – | ||

| 33 | 32.6 | – | ||

| 42 | – | 1.58 | ||

| 56 | 28.4 | – | ||

| 64 | – | 2.71 | ||

| Chon. F+ | 12 | 19.5 | 2.17 | |

| 44 | 18.3 | 0.41 | ||

| MSC19 | ||||

| FGF+ | 1 | – | 0.99 | |

| 5 | 28.7 | – | ||

| 9 | 26.8 | 1.59 | ||

| 14 | – | 2.03 | ||

| 54 | 28.5 | – | ||

| Chon. F+ | 6 | 18.3 | 3.66 | |

| MSC45 | ||||

| FGF+ | 4 | 31.4 | 1.70 | |

| 27 | 32.5 | 5.94 | ||

| 62 | 30.6 | 1.02 | ||

| Chon. F+ | 12 | 18.5 | 1.67 | |

| 47 | – | 0.08 | ||

| MSC19 | ||||

| FGF– | 2 | 16.2 | – | |

| 4 | – | 1.27 | ||

| 8 | 15.8 | – | ||

| 9 | – | 3.22 | ||

| 13 | – | 1.16 | ||

| Chon. F– | 7 | – | 2.73 | |

| 9 | 13.7 | – | ||

| 11 | – | 4.66 | ||

| h‐Chon.79 | 16 | 13.3 | 1.71 | |

| Saos‐2 | 12 | – | 95.1 | |

After Southern blot, telomere signals were measured by Bioimage analyser, and the peak of the signals was estimated as the length of TRFs. Telomerase activity was measured by the telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay. Human osteosarcoma, Saos‐2 as telomerase activity‐positive cells were cultured. MSC14, 19 and 45 (donor age: 14, 19 and 45 years old, respectively), h‐Chon.79; human chondrocytes (79 years old).

FGF‐2‐expanded MSC did not have telomerase activity

The levels of telomerase activity were very low in FGF(+)MSC and FGF(–)MSC, both before and after differentiation (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have demonstrated that FGF(+)MSC had higher proliferation potential and chondrogenic potential than MSC cultured without FGF‐2 supplementation. We found that FGF(+)MSC maintained chondrogenic potential up to at least 46 PD, and had long telomeres up to 105 PD, but telomerase activity of these cells was very low.

Regarding the chondrogenesis of MSC, Sekiya et al. (2001) reported that Johnstone's chondrogenic medium induced chondrogenesis of MSC, although staining for proteoglycans was weak, the addition of BMP‐6 to the medium increased proteoglycan content. Our medium was based on Johnstone's method, and explains the weak metachromasia expressed by the differentiated cells (Fig. 2). Our results suggest that FGF(+)MSC have retained chondrogenic potential up to at least 46 PD, maintaining long telomeres. Additionally, Bianchi et al. (2003) reported ex vivo enrichment of MSC by FGF‐2. Their results demonstrated that FGF(+)MSC had long telomeres and maintained chondrogenic potential up to 50 PD, and support the data we obtained. Taken together, our data and their findings suggest that this long telomere of FGF(+)MSC may be a useful genetic marker for such chondrogenic progenitor cells.

We found that FGF(+)MSC maintained long telomeres, whereas upon differentiation, telomeres of FGF(+)MSC showed a remarkably shortened lengths (Fig. 3, Table 1; MSC14, 19 and 45, Chon. F+). This shortening was more extensive when FGF(+)MSC of higher PD levels were differentiated (Fig. 3, Table 1; MSC14, Chon. F+). To our knowledge, this result is the first report of this phenomenon. However, both the mechanism that maintained telomeres in FGF‐2 expanded MSC, and the correlation between the extent of erosion of telomere length due to the PDL at differentiation, are unknown. Bianchi et al. reported that FGF(+)MSC telomere lengths may not be maintained by telomerase, supporting our results (Bianchi et al. 2003). Recently, however, telomerase‐deficient mice were reported to show impaired differentiation of MSC, suggesting that the low levels of telomerase activity may be necessary to maintain the growth of MSC (Liu et al. 2004). Moreover, although telomerase activity is not detected in cancer cells, telomeres of the cells are long. This phenomenon is called ‘alternative lengthening of telomeres’ (ALT) (Bryan & Reddel 1997). At present, although the mechanism is not clear, it is thought to be regulated by genetic recombination. Recently, telomere maintenance mechanisms by homologous genetic recombination has been reported (Dunham et al. 2000), and that homologous genetic recombination‐related factors, Rad50, Mre11 and NBS1, bind to the ends of telomeres, depending on cell‐cycle activity (Zhu et al. 2000). Mre11 and Rad50 are known to be required for cell proliferation to proceed. In the future, it must be elucidated whether the ALT mechanism would act not only on cancer cells, but also on stem cells including MSC, and whether it would function under usual homeostatic conditions of the body. Additionally, relation between FGF‐2, Mre11 and Rad50 should be investigated by gene expression profiling of FGF‐2 expanded MSC in the future.

Currently, a novel method of telomere length measurement using fluorescence in situ hybridazation (FISH), Telo‐FISH, has been reported (Rufer et al. 1998) and has been widely used. Telo‐FISH is performed using a fluorescein isothiocianate‐labelled peptide nucleic acid probe for (TTAGGG)n specific sequences. The telomere signals in cells are counted by flow cytometry. Cells that have strong telomere signals can be classified by a cell sorter such as FACS Caliber (BD Biosciences). Most recently, we have succeeded in classifing FGF(+)MSC by telomere length. However, this method by flow cytometry cannot be applied to live cells, as cells die when treated with reagents for telomere labelling. In the near future, if this method can be applied to live cells, we believe that selection of chondrogenic progenitor cells using Telo‐FISH in FGF(+)MSC is likely to be useful as strategy for stem cell therapy.

In conclusion, we have found that by seeding FGF(+)MSC at a relatively low density (2 × 105 cells per 100‐mm plate), FGF(+)MSC retain high proliferative and chondrogenic potentials for greater numbers of PDs, together with stable long telomere lengths with increasing PD levels, despite expressing low levels of telomerase activity. Additionally, we have found that upon chondrogenic differentiation, the telomeres of the MSC shorten drastically, and that the extent of shortening relates to PD level at differentiation. These findings suggest that telomere length may be a useful genetic marker for chondrogenic progenitor cells.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Ikuko Fukuba and Dr Tomohiro Nakano of the Hiroshima University for their technical assistance with the Southern blot and histological analyses and also for their encouragement. The present study was supported in part by Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (No. 16209045) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

REFERENCES

- Baxter MA, Wynn RF, Jowitt SN, Wraith JE, Fairbairn LJ, Bellantuono I (2004) Study of telomere length reveals rapid aging of human marrow stromal cells following in vitro expansion. Stem Cells 22, 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi G, Banfi A, Mastrogiacomo M, Notaro R, Luzzatto L, Cancedda R, Quarto R (2003) Ex vivo enrichment of mesenchymal cell progenitors by fibroblast growth factor 2. Exp. Cell Res. 287, 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Reddel RR (1997) Telomere dynamics and telomerase activity in in vitro immortalised human cells. Eur. J. Cancer 33, 767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AI, Bruder SP (2001) Mesenchymal stem cells: building blocks for molecular medicine in the 21st century. Trends Mol. Med. 7, 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans RJ, Moseley AB (2000) Mesenchymal stem cells: biology and potential clinical uses. Exp. Hematol. 28, 875–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Obrocka M, Fischer I, Prockop DJ (2001) In vitro differentiation of human marrow stromal cells into early progenitors of neural cells by conditions that increase intracellular cyclic AMP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 282, 148–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digirolamo CM, Stokes D, Colter D, Phinney DG, Class R, Prockop DJ (1999) Propagation and senescence of human marrow stromal cells in culture: a simple colony‐forming assay identifies samples with the greatest potential to propagate and differentiate. Br. J. Haematol. 107, 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham MA, Neumann AA, Fasching CL, Reddel RR (2000) Telomere maintenance by recombination in human cells. Nature Genet. 26, 447–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Funk WD, Wang SS, Weinrich SL, Avilion AA, Chiu CP, Adams RR, Chang E, Allsopp RC, Yu J, Le S, West MD, Harley CB, Andrews WH, Greider CW, Villeponteau B (1995) The RNA component of human telomerase. Science 269, 1236–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW (1990) Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 345, 458–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama E, Hiyama K (2002) Clinical utility of telomerase in cancer. Oncogene 21, 643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama E, Hiyama K, Yokoyama T, Ichikawa T, Matsuura Y (1992) Length of telomeric repeats in neuroblastoma: correlation with prognosis and other biological characteristics. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 83, 159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama E, Hiyama K, Yokoyama T, Matsuura Y, Piatyszek MA, Shay JW (1995a) Correlating telomerase activity levels with human neuroblastoma outcomes. Nat. Med. 1, 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama E, Yokoyama T, Tatsumoto N, Hiyama K, Imamura Y, Murakami Y, Kodama T, Piatyszek MA, Shay JW, Matsuura Y (1995b) Telomerase activity in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 55, 3258–3262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama E, Yamaoka H, Matsunaga T, Hayashi Y, Ando H, Suita S, Horie H, Kaneko M, Sasaki F, Hashizume K, Nakagawara A, Ohnuma N, Yokoyama T (2004) High expression of telomerase is an independent prognostic indicator of poor outcome in hepatoblastoma. Br. J. Cancer 91, 972–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby PJ (2002) Cellular senescence and tissue aging in vivo . J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 57, B251–B256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal N, Haynesworth SE, Caplan AI, Bruder SP (1997) Osteogenic differentiation of purified, culture‐expanded human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro . J. Cell. Biochem. 64, 295–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, Schwartz. RE, Keene CD, Ortiz‐Gonzalez. XR, Reyes M, Lenvik T, Lund T, Du Blackstad MJ, Aldrich S, Lisberg A, Low WC, Largaespada DA, Verfaillie CM (2002) Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature 418, 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone B, Hering TM, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, Yoo JU (1998) In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Exp. Cell Res. 238, 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, Coviello GM, Wright WE, Weinrich SL, Shay JW (1994) Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science 266, 2011–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Gotherstrom C, Hassan M, Uzunel M, Ringden O (2004) Treatment of severe acute graft‐versus‐host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet 363, 1439–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Digirolamo CM, Navarro PA, Blasco MA, Keefe DL (2004) Telomerase deficiency impairs differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Cell Res. 294, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger MF, Markay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR (1999) Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 284, 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufer N, Dragowska W, Thornbury G, Roosnek E, Lansdorp PM (1998) Telomere length dynamics in human lymphocyte subpopulations measured by flow cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 743–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya I, Colter DC, Prockop DJ (2001) BMP‐6 enhances chondrogenesis in a subpopulation of human marrow stromal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284, 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumoto N, Hiyama E, Murakami Y, Imamura Y, Shay JW, Matsuura Y, Yokoyama T (2000) High telomerase activity is an independent prognostic indicator of poor outcome in colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 6, 2696–2701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi S, Shimazu A, Miyazaki K, Pan H, Koike C, Yoshida E, Takagishi K, Kato Y (2001) Retention of multilineage differentiation potential of mesenchymal cells during proliferation in response to FGF. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 288, 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri H, Dragowska W, Allsopp RC, Thomas TE, Harley CB, Lansdorp PM (1994) Evidence for a mitotic clock in human hematopoietic stem cells: loss of telomeric DNA with age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 9857–9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellinger RJ, Ethier K, Labrecque P, Zakian VA (1996) Evidence for a new step in telomere maintenance. Cell 85, 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright WE, Shay JW (2002) Historical claims and current interpretations of replicative aging. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 682–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XD, Kuster B, Mann M, Petrini JH, De Lange T (2000) Cell‐cycle–regulated association of RAD50/MRE11/NBS1 with TRF2 and human telomeres. Nature Genet. 25, 347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]