Abstract

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are considered patient‐specific counterparts of embryonic stem cells as they originate from somatic cells after forced expression of pluripotency reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc. iPSCs offer unprecedented opportunity for personalized cell therapies in regenerative medicine. In recent years, iPSC technology has undergone substantial improvement to overcome slow and inefficient reprogramming protocols, and to ensure clinical‐grade iPSCs and their functional derivatives. Recent developments in iPSC technology include better reprogramming methods employing novel delivery systems such as non‐integrating viral and non‐viral vectors, and characterization of alternative reprogramming factors. Concurrently, small chemical molecules (inhibitors of specific signalling or epigenetic regulators) have become crucial to iPSC reprogramming; they have the ability to replace putative reprogramming factors and boost reprogramming processes. Moreover, common dietary supplements, such as vitamin C and antioxidants, when introduced into reprogramming media, have been found to improve genomic and epigenomic profiles of iPSCs. In this article, we review the most recent advances in the iPSC field and potent application of iPSCs, in terms of cell therapy and tissue engineering.

Introduction

Pluripotency is the ability of cells to undergo indefinite self‐renewal and differentiate into all specialized cell lineages 1. This developmental potential is a natural property of mammalian embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and enables their use in developmental studies and regenerative medicine 1. Clinical exploitation of this developmental plasticity, however, requires an alternative source of pluripotent cells to avoid ethical and mechanistic limitations inherent in consideration of the use of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). Early cell reprogramming techniques, such as somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) 2, 3, 4 and transdifferentiation 5 indicated that phenotype identity can be reprogrammed. Animal cells possess considerable plasticity which under certain in vitro conditions can switch their fate. This discovery paved the way for development of induced pluripotent stem cell lines (iPSC lines). In a revolutionary study, Takahashi and Yamanaka et al. demonstrated that forced expression of four ESC‐specific transcription factors (TFs)/reprogramming factors – Oct4 (octamer‐binding transcription factor 4), Sox2 (sex determining region Y box 2), Klf4 (Krueppel‐like factor 4) and c‐Myc (v‐Myc myelocytomatosis avian viral oncogene homolog), the OSKM Yamanaka factors, reprogramme adult mouse fibroblasts to become mouse ESC‐like cells, termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) 6. In the following year, Takahashi et al. and Yu et al., independently reported human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) from human fibroblasts (Fig. 1) 7, 8. A distinctive feature of OSKM‐induced iPSCs (OSKM‐iPSCs) is that they resemble ESCs. iPSCs conform to the major aspects of pluripotency, such as pluripotent state‐specific marker gene expression, unlimited self‐renewal, multilineage differentiation potential (assayed via embryoid body and teratoma formation techniques) and germline transmissibility 8, 9, 10, 11. Mouse iPSCs are also used to produce viable all‐iPSC mice by the tetraploid blastocyst complementation technique 12, 13; a key assay for assessing true cell pluripotency, strictly ascribed to hiPSCs. The prospect of obtaining OSKM‐iPSCs from somatic cell origins promises an authentic source of patient‐specific pluripotent cells for clinical application. A plethora of studies published so far has reported obtaining authentic iPSCs from a large variety of mouse and human somatic cells, employing different strategies and combinations of reprogramming factors (see Table S1).

Figure 1.

Reprogramming adult somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC s) through ectopic expression of reprogramming factors. Forced expression of these pluripotency factors resets the epigenetic and transcriptional profile of the specialized cells and reverts them back to their embryonic state.

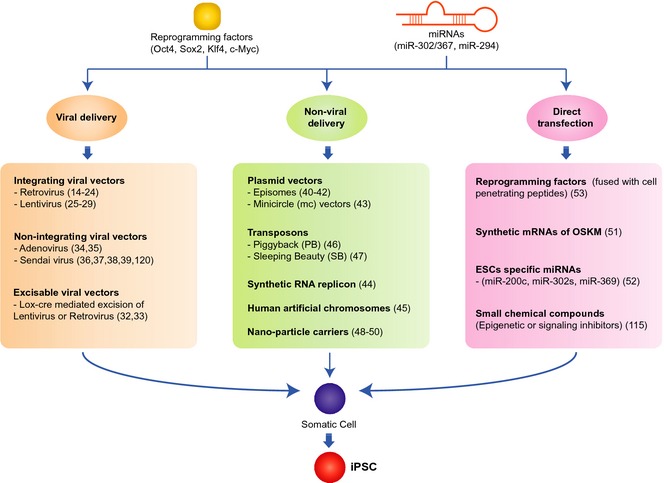

Early reprogramming endeavours relied on viral delivery systems such as by retrovirus or lentivirus 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, however, non‐viral vectors, for example episomes, minicircle vectors, transposons, human artificial chromosome vectors and nanoparticle carriers, have subsequently emerged as alternatives to avoid complications of viral reprogramming 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 (Fig. 2). Analyses of the pluripotency gene regulatory network has helped distinguish alternative reprogramming factors 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82 and small chemical inhibitors 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107 to alleviate existing challenges to iPSC development, including poor reprogramming efficiency and conversion of partially reprogrammed cells into iPSCs. Recent studies also suggest that in vitro nutritional supplements such as vitamin C and antioxidants improve the quality of iPSCs 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114. These advancements may enable clinical‐grade patient‐specific iPSCs for therapeutic application. Hence in this review, we summarize the most recent advances and current status of iPSC technology.

Figure 2.

Overview of the approaches available for generating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC s). Somatic cells can be reprogrammed into iPSCs using viral/non‐viral delivery system or direct application of the reprogramming factors, their mRNAs or embryonic stem cell‐specific miRNAs.

Recent advances in pluripotency reprogramming

Delivery systems

Introducing reprogramming factors (RFs) to target cells is the first step in pluripotency induction. Several delivery systems have been developed for this task, including viral vectors 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, non‐viral vectors 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 and the direct transfection approach 51, 52, 53, 54 (see Fig. 2).

Viral vectors

Integrating viral vectors (IVVs) such as retroviruses 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 and lentiviruses 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 122 are the most common delivery system for cell reprogramming and iPSC generation 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29. IVVs deliver and maintain persistent expression of RFs; however, this process results in integration of multiple proviral copies throughout host cell genomes – raising the possibility of genomic instability and chromosomal aberration 6, 9, 10. Polycistronic viral vectors (PVVs) can overcome problems associated with IVVs 30, 31. PVVs are single viral constructs which carry all RFs that are separated by autonomous self‐cleaving peptides such as 2As. In PVVs, RFs are expressed from a single promoter, producing a single transcript. Two existing lentivirus‐based PVVs have shown adequate exogenous expression that only a single proviral copy is needed to reprogramme a somatic cell, with high fidelity 30, 31, although leaky expression from these viral constructs may still occur. An alternative choice might be Lox‐Cre‐mediated excision of viral constructs from loxp‐flanked genomic sites 32, 33 which produces iPSCs free of exogenous elements. However, the likelihood of minute viral remnants is still a concern for clinical applicability of iPSCs 32. In this regard, non‐IVVs that avoid genomic integration, such as Adenovirus and Sendai virus (SeV) systems, seem to be a reasonable choice for generating iPSCs 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39. Adeno‐iPSCs are devoid of viral integration 34, 35, although minor incidence of tetraploid adeno‐iPSC has also been reported 34. SeV vectors also generate authentic iPSCs without being incorporated into the host genome, while retaining high conversion efficiency 36, 37, 119, 120. SeV vectors gradually deplete from iPSC cytoplasm after several passages which makes subsequent iPSC generations exogenous element free 36, 37, 120. To ensure complete removal of viral constructs, a temperature‐sensitive Sendai vector mutant may be used 38, 39.

Non‐viral vectors

Several non‐viral vectors have been described for iPSC reprogramming which circumvent the problems of viral vectors. These include episomal vectors 40, 41, 42, minicircle (mc) vectors 43, synthetic RNA replicons 44, human artificial chromosomes 45, transposon systems 46, 47 and nanoparticle carriers 48, 49, 50.

The Epstein–Barr virus‐derived oriP/EBNA1 episomal vector has been extensively used to generate foot‐print free iPSCs. This vector is non‐integrating, persists throughout reprogramming and subsequently diminishes in iPSCs 40, 41. A further non‐viral vector is p2phic31 plasmid‐derived minicircle (mc). Its reprogramming efficiency is greater than standard plasmid/episome vectors and generates true iPSCs 43. Self‐replicating RNA vectors are another potential delivery method for footprint‐free iPSCs 44. Based on non‐infectious, self‐replicating Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) viral RNA, the positive‐sense polycistronic VEE ssRNA construct (VEE‐RF RNA replicon) can transduce RFs into host cells and maintain transgene expression for successful reprogramming 44. Interestingly, human artificial chromosome (HAC) vectors can also be effective in generating vector and transgene‐free iPSCs 45.

In addition, transposon systems such as piggybac (PB) and sleeping beauty (SB) can be used to produce iPSCs. Successful excision of PB from iPSC‐genomes has been reported 46, although SB systems require further optimization to ensure exogenous construct removal.

There is growing interest in nanoparticle and synthetic carriers as RF delivery systems for iPSC reprogramming. For example, using cationic Bolaamphiphile coupled with Klf4, Nanog, NR5A2 (orphan nuclear receptor) and Sox2, Khan et al. successfully reprogrammed human fibroblasts 48. Using a different cationic lipid carrier, Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (LF), fused with OSKM mRNAs, Tavernier et al. generated miPSCs from mouse fibroblasts 49. Sohn et al. utilized ESC‐specific microRNAs (miR‐302/367 cluster) fused with polyketal copolymer PK3 to generate miPSCs 50. While these synthetic vectors successfully generate transgene‐free iPSCs, the labour‐intensive method involved has largely limited their use.

Direct transfection

In addition to vector‐based approaches, direct transfection methods have been adopted also. Warren et al. demonstrated that repeated administration of synthetic Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c‐Myc and Lin28 mRNAs generates authentic hiPSCs 51. Miyoshi et al. generated mouse and human iPSCs by direct delivery of ESC‐specific miRNAs (mir‐200c, mir‐302s and mir‐369) 52. Direct delivery of purified RFs also has been successful in producing iPSCs. Repeated administration of OSKM factors fused with cell‐penetrating peptide 9‐arginine (RFP‐9R) can produce hiPSCs 53. Cho et al. showed that a single transfection of whole cell protein extract from mESCs can reprogramme adult mouse fibroblasts into iPSCs 54. In contrast, neither cytoplasmic nor nuclear fraction‐derived protein extracts from mESCs was able to induce reprogramming alone 54. This suggests a combination of factors from different cell compartments acts together for pluripotency reprogramming.

Alternative reprogramming factors for iPSCs

While ESC‐specific miRNAs can generate iPSCs 52, 55, OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc)‐based reprogramming remains the most convenient way of generating them 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 120, 121; however, poor reprogramming efficiency of OSKM (usually less than 1%) is still a key concern 56. Lately, researchers have characterized a range of novel factors that may substitute OSKM and facilitate improved reprogramming with greater efficiency when inducing pluripotency (Table 1).

Table 1.

Alternative reprogramming factors for induced pluripotency

| Factors | Function | Accompanied factors | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| UTF1 | Enhances reprogramming efficiency, improves pre‐iPSCs to iPSCs transition and can replace c‐Myc | OSKM or OSK | 60 |

| Wnt3a | Replaces c‐Myc, endows higher reprogramming efficiency and homogenous iPSCs colonies | OSK | 61 |

| Esrrb | Replaces reprogramming factor Klf4 | OSM or OS | 71 |

| Nr5a1/Nr5a2 | Functionally substitutes Oct4, improves reprogramming efficiency and kinetics | SKM | 81 |

| Tbx3 | Accelerates reprogramming, increases the number of fully reprogrammed cell, improves germline competency of iPSCs | OSK | 65 |

| BMP4 | Can replace Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc, facilitates mesenchymal‐to‐epithelial transition (MET) | SK | 72 |

| E‐cadherin | Replaces Oct4 during reprogramming | SKM | 80 |

| GLIS1 | Effectively replaces c‐Myc | OSK | 61 |

| Bmi1 | Can replace Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc | Oct4 | 75 |

| Oxysterol or purmorphamine | Can replace Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc | Oct4 | |

| Nanog | Can replace Oct4 | Bmi1/oxysterol/purmorphamine | 79 |

| Parp1/Parp2 | Significantly enhance reprogramming efficiency, able to replace Klf4 and c‐Myc | OSKM or OSM | 67 |

| Kdm2b | Can replace c‐Myc, improves reprogramming efficiency | OSK | 63 |

| Zic3 | Promising candidate for c‐Myc replacement, improves iPSCs yield | OSK | 66 |

| Zscan4 | Replaces c‐Myc, improves reprogramming efficiency, amend iPSC quality (complete developmental potential, enhanced telomere lengthening and stabilized genomic integrity) | OSK | 68, 69 |

| RCOR2 | Can substitutes Sox2 | OKM | 70 |

| Id3 | Alone can transdifferentiates mEFs into NSC/NPCs‐like state, potential substitute for Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc | Oct4 | 76 |

| Tet1 | Potent alternative of Oct4, improves reprogramming efficiency | SKM or SK | 82 |

| EpCAM | Improves iPSCs yield | OSKM and Cldn7 | 83 |

| HMGA1 | Enhances reprogramming efficiency up to 2‐fold | OSKM | 84 |

| Zfp296 | Increases number of iPSC colonies, accelerates reprogramming | OSKM | 85 |

O, Oct4; S, Sox2; K, Klf4; C, c‐Myc.

Alternative factors for c‐Myc

c‐Myc's role in maintenance and acquisition of pluripotency has been disputed. Despite its ability to boost reprogramming efficiency of a broad pool of somatic cells 10, 56, 57, forced expression of c‐Myc can also cause tumourigenicity 6. In addition, a multitude of reports has demonstrated that deregulation of c‐Myc can trigger genomic instability and induce a broad range of cancer progression 58, 59. Thus, uncontrolled expression of c‐Myc is a potential risk for iPSCs. As excluding c‐Myc from the reprogramming cocktail reduces reprogramming efficiency 10, 11, discovery of a potent alternative of this proto‐oncoprotein needs to be prioritized. Recent studies suggest that previously reported factors may have a similar mode of action during pluripotency reprogramming. For example, substituting c‐Myc with UTF1 (undifferentiated embryonic cell transcription factor 1) generates iPSCs with reprogramming efficiency of around 3 × 10−4 which is approximately 10 times higher than OSK transfection 60. Similarly, c‐Myc's substitution with Wnt3a (a soluble Wnt signalling protein) can generate homogenous ESC‐like colonies with higher efficiency – 20‐fold more iPSCs from OSK‐transfected mouse fibroblasts with Wnt3a versus OSK transfection only 61. A further alternative to c‐Myc is GLIS1 (Glis family zinc finger protein 1), a maternally expressed transcription factor. GLIS1 increases numbers of fully‐reprogrammed iPSCs in the absence of c‐Myc 62. Kdm2b, a histone H3 Lys 36 dimethyl‐specific demethylase, can also be used to substitute c‐Myc and has resulted in improved reprogramming of OSK‐transfected mEFs – 4 to 6 fold more iPSCs from OSK+Kdm2b than OSK only 63. Chiou et al. demonstrated that both Parp1 and Parp 2 proteins (poly ADP ribose polymerases) can replace c‐Myc with increased reprogramming efficiency 64. Interestingly, Parp 1 together with OS can reprogramme mouse fibroblasts with higher efficiency – reprogramming efficiency close to 2.2% – suggesting Parp 1 to be a promising candidate for future pluripotency reprogramming. T‐box transcription factor 3 (Tbx3) is a pluripotency‐associated transcription factor which drastically improves iPSC quality when transduced with OSK 65. Compared to OSK‐iPSCs, addition of Tbx3 accelerates the reprogramming process and increases numbers of fully‐reprogrammed cells – up to 34 more OSKT‐iPSC colonies compared to OSK alone. OSKT‐iPSCs also exhibit improved germline transmissibility indicating closer resemblance to ESCs 65. Thus, Tbx3 action on hiPSC generation needs to be investigated.

Zic3 (zinc finger transcription factor in cerebellum‐3) can also be used to replace c‐Myc and results in improved iPSC yield from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (mEFs) with OSK. OSKZ‐iPSCs remarkably resemble mESCs in aspects of morphology, epigenomic profile and developmental potential 66. However, it has been reported that OSKZ overexpression converts human fibroblasts into neuronal progenitor‐like cells (NPCs) 67. Thus, further investigation needs to be performed to determine whether Zic3 primes cells into the neuronal fate only in human fibroblasts, or whether other human somatic cells are reprogrammable with Zic3.

Zscan4 is a promising candidate for c‐Myc replacement too. Zscan4 is a zygote‐specific factor, which in the absence of c‐Myc, can reprogramme mouse and human somatic cells with markedly higher efficiency (up to 6.7%) in conjunction with OSK 68, 69. Most importantly, Zscan4 substantially improves quality of resultant iPSCs by restoring complete developmental potential (all‐iPSC mice), telomere elongation in OSK+Zscan4‐iPSCs compared to putative OSKM‐iPSCs, maintenance of genomic stability and reduction of DNA damage response underlying iPSC‐based reprogramming 69.

Alternative factors for Oct4/Sox2/Klf4

Embryonic stem cells‐specific co‐repressor RCOR2 can be substituted for Sox2 in reprogramming mouse and human somatic cells, and generates iPSCs 70. In contrast, Esrrb (estrogen‐related receptor beta) can replace Klf4, although reprogramming efficiency declines 71. Similarly, BMP4 (bone morphogenetic protein 4) can supplant Klf4 during mouse fibroblast reprogramming 72. Using modified culture conditions, BMP4 and Oct4 can reprogramme mouse fibroblasts with reasonable efficiency and kinetics, supporting BMP4 potential as a RF 72. However, previous reports have suggested that BMP4 supports mESCs maintenance 73 and triggers differentiation in hESCs 74. Thus, generating hiPSCs with BMP4 requires further investigation.

A further promising reprogramming factor is Bmi1 (polycomb complex protein BMI‐1). Bmi1 can functionally replace Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc, and along with Oct4 generate authentic iPSCs from mEFs with increased reprogramming efficiency of 0.17% 75. In addition, Bmi1–Oct4‐iPSCs closely resemble mESCs and fulfil all criteria of pluripotency 75. Id3 (inhibitor of differentiation 3) seems to be another interesting candidate for replacing Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc. Id3 overexpression transdifferentiates mEFs into NSC/NPC‐like phenotypes which can be further reprogrammed into iPSCs with Oct4 alone 76. Both Bmi1 and Id3 should be further investigated in human somatic cells, as they show promise as potential RFs.

Initially, researchers presumed that Oct4 presence was essentially indispensable for inducing pluripotency, however, recent reports have contradicted this notion. For example, Moon et al. (2013) reported that Nanog, the core guardian of ESC pluripotency 77, 78, together with Bmi1 can reprogramme mouse fibroblasts into iPSCs, in the absence of Oct4 79. Ectopic expression of E‐cadherin can also compensate for exogenous Oct4 requirement and generates iPSCs in concert with Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc 80. Although reprogramming efficiency is relatively low compared to the OSKM method, these Oct4‐free ESKM‐iPSCs display similarities in morphology, epigenetic and developmental potential, as mESCs 80. Similarly, orphan nuclear receptors (Nr5a2 and Nr5a1) can substitute Oct4 and generate iPSCs with Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc (SKM) from mEFs 81. Tet1, a DNA demethylating factor in mammalian systems, can also substitute Oct4 and in conjunction with SKM or SK reprogrammes differentiated somatic cells into authentic iPSCs 82. Tet1 induction improves reprogramming efficiency, and TSKM‐iPSCs resemble OSKM‐iPSCs and ESCs. The Tet1 mode of action is by demethylating endogenous Oct4 loci in a 5mC‐to‐5hmC manner 82.

These studies indicate that the complexity of transcriptional regulation governing pluripotency involves crosstalk between several key factors and there are multiple counterparts of major pluripotency factors.

Chemical supplements for reprogramming: introducing small molecules

Even though methods employing miRNA, mRNA or direct delivery of RFs for inducing pluripotency are well established (see Table S1), development of novel reprogramming techniques involving fewer RFs while increasing iPSC yield are worth pursuing. This endeavour has ultimately prioritized small molecules/chemical supplements for cell reprogramming.

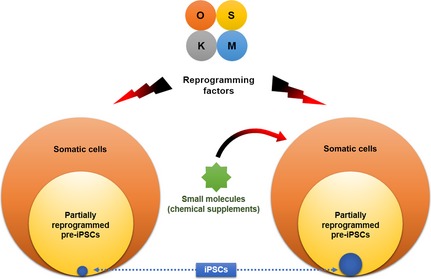

There is growing evidence to support the notion that small molecules (SMs) may revolutionize the iPSC field by replacing RFs and improving overall reprogramming efficiency‐kinetics (Table 2). Many of these chemical supplements are inhibitors of major signalling pathways and epigenetic regulators 86. For instance, valproic acid (VPA) is a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor which ameliorates OSKM‐based reprogramming efficiency 87. Similarly, 5′‐azacytidine (5‐azac), a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, increases numbers of fully reprogrammed iPSCs from OSKM‐transfected cells, in a dose‐dependent manner 88. 5‐azac + VPA treatment of OSK‐transfected cells accelerates the reprogramming process with high iPSC yield compared to OSKM transduction only 88. EPZ004777 is a potential chemical supplement which inhibits H3K79 histone methyltransferase Dot1L. Treatment with EPZ004777 yields a 3‐ to 4‐fold increase in iPSC formation from human and mouse fibroblasts when used in conjunction with OSKM 89. Similarly, reprogramming stimulating compound RSC133, an indoleacrylic acid analogue, accelerates iPSC conversion and increases reprogramming efficiency up to 3.3‐fold over OSKM‐transfected human foreskin fibroblasts 90. RSC133 stimulatory effects stem from its ability to promote cell proliferation by down‐regulating p53, p21 and p16/INK4A, and repressing epigenetic modulators such as Dnmt1 and HDAC1 90. Wei et al. recently reported that CYT296, a chromatin de‐condensing compound, improves reprogramming efficiency of OSKM‐transfected mouse somatic cells up to 10‐fold 91. In addition, treatment with Aurora kinase, p38 kinase and inositol trisphosphate 3‐kinase inhibitors result in increased OSKM‐iPSCs yield 92. MEK inhibitor, PD0325901, acts in the later stages of somatic cell reprogramming during endogenous Oct4 expression, and inhibits non‐iPSC colony formation while promoting authentic iPSC population growth 93. For successful reprogramming, these inhibitors can be useful, particularly for partially reprogrammed cells and cells resistant to reprogramming, as they represent a substantial portion of RF‐transfected cell populations 94 (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Small molecules for induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) generation

| Compound | Function | Associated factors | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valproic acid (VPA) | A histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor. Improves reprogramming efficiency, replaces c‐Myc and Klf4 during reprogramming | OS | 87 |

| 5′‐azacytidine (5′‐azac) | A DNA methyltransferase inhibitor. Amends reprogramming efficiency and number of reprogrammed cells in a dose‐dependent manner | OSKM/OSK | 88 |

| BIX‐01294 (BIX) | An inhibitor of the G9a histone methyltransferase. Functionally substitutes exogenous c‐Myc and Sox2 during reprogramming, improves poor reprogramming efficiency | OK | 93 |

| PD0325901 | MEK inhibitor. Promotes growth of fully reprogrammed iPSCs in later stage of reprogramming | OSKM | |

| Bayk | An L‐calcium channel agonist. Together with BIX substitutes c‐Myc and Sox2 and significantly increases number of reprogrammed cells | OK | 100 |

| CHIR99021 | A GSK3b inhibitor. Together with PD0325901 and A‐83‐01 reprogrammes human somatic cells to ground state pluripotency, | OSNL | 103 |

| Can replace Sox2 and c‐Myc | OSK or OK | 95 | |

| Repsox (E‐616452) | A transforming growth factor β receptor 1 (TGFβr1) kinase inhibitors. Substitutes exogenous Sox2 and c‐Myc requirement during reprogramming. Assists partially reprogrammed cells to authentic pluripotent state | OK | 99 |

| SB431542 | ALK5 inhibitor. Together with PD0325901 and thiazovivin drastically improves reprogramming efficiency and kinetics | OSKM | 104 |

| A‐83‐01 | Potent TGF‐β receptor inhibitor. Induces ground‐state pluripotency in Oct4‐transfected human somatic cell in conjugation with PS48, sodium butyrate and PD0325901 | O | 105 |

| AMI‐5 | A protein arginine methyltransferase (PRMT) inhibitor. In concert with A‐83‐01 reprogrammes somatic cell with Oct4 alone | O | 106 |

| EPZ004777 | Inhibitor of H3K79 histone methyltransferase Dot1L, yields OSKM‐iPSCs from mouse and human fibroblasts up to 4‐fold, can substitute Klf4 and c‐Myc | OSKM | 89 |

| RSC133 | An indoleacrylic acid analogue. Improves OSKM‐hiPSCs yield up to 3.3‐fold, accelerates reprogramming, improves cell proliferation potential | OSKM | 90 |

| CYT296 | A chromatin de‐condensing compound, improves reprogramming efficacy of OSKM‐transfected cells up to 10‐fold | OSKM | 91 |

| Inhibitors of inositol trisphosphate 3‐kinase, Aurora kinase and P38 kinase | Improves reprogramming efficiency | OSKM | 92 |

| Dasatinib (PP1) | Inhibitors of pan‐Src family kinase (SFK), can replace Sox2 | OKM | 96 |

| ALK5 inhibitor | Inhibitor of Tgfb receptor I kinase/activin‐like kinase 5, can replace Sox2, a potent alternative of c‐Myc too | OKM or OK | 97 |

| Kenpaullone | Chemical substitute of Klf4 | OSM | 98 |

| Parnate | An inhibitor of lysine‐specific demethylase 1, in association with CHIR99021 replaces Sox2 and c‐Myc | OK | 95 |

| OAC1 | Chemical activator of Oct4, remarkably improves reprogramming efficiency (up to 20‐fold) and accelerates the process | OSKM | 101 |

O, Oct4; S, Sox2; K, Klf4; C, c‐Myc; L, Lin28.

Figure 3.

Small molecules improve pluripotency reprogramming efficiency. Administration of small molecules (chemical supplements) drastically improves the efficiency of pluripotency reprogramming and accelerates the process itself. Part of this amendment is facilitated by conversion of a large pool of partially reprogrammed pre‐induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into fully reprogrammed iPSCs.

As mentioned earlier, some chemical inhibitors have the capacity to replace established RFs either individually or in concert. For instance, CHIR99021 [a glycogen synthase kinase‐3 beta (GSK3b) inhibitor] 95, Dasatinib/PP1 [inhibitors of pan‐Src family kinase (SFK)] 96 and Tgfb receptor I kinase aka activin‐like kinase 5 (ALK5) inhibitor 97 can functionally replace Sox2. ALK5 inhibitor is also an alternative for c‐Myc and increases reprogramming efficiency up to 2.5‐fold in comparison with OSKM transfection 97. Conversely, Kenpaullone is a chemical substitution for Klf4 that repeats Klf4 functions such as inducing endogenous Nanog expression 98.

There are SMs that can substitute multiple RFs, these include VPA 87, EPZ004777 89, CHIR99021 95, Parnate 95, Repsox 99 and BIX 93, 100. Both VPA and EPZ004777 are capable of replacing Klf4 and c‐Myc 87, 89. CHIR99021 and Repsox (E‐616452) are transforming growth factor β receptor 1 (TGFβr1) kinase inhibitors which can substitute Sox2 and c‐Myc to generate iPSCs from mouse fibroblasts 95, 99. Repsox treatment also assists partially reprogrammed somatic cells to transform into true pluripotent state. It has been suggested that Repsox replaces Sox2 by inducing Nanog expression and inhibiting TGF‐β signalling 99. Parnate (tranylcypromine), which inhibits lysine‐specific demethylase 1, in association with CHIR99021 generates authentic hiPSCs from primary human keratinocytes with Oct4 and Klf4, although this method is 100‐fold less efficient than OSKM reprogramming 95. BIX (BIX‐01294), an inhibitor of the G9a histone methyltransferase, can also substitute Sox2 and c‐Myc, and produce iPSCs with Oct4 and Klf4 only 93, 100.

Disputing the concept that exogenous Oct4 expression is fundamental to pluripotency reprogramming, BIX – serving as a substitute for Oct4 – generates iPSCs from mouse neural progenitor cells (NPCs) with Klf4, Sox2 and c‐Myc only 93. Despite endogenous Sox2 expression in NPCs, exogenous Sox2 is required for NPC reprogramming, in the absence of Oct4. mEFs can be reprogrammed into iPSCs with Oct4, Klf4 (OK) and BIX, although with lower efficiency than with OSKM‐based reprogramming or OK+BIX‐based reprogramming of NPCs 100. Addition of Bayk, an L‐calcium channel agonist, can further improve OK+BIX mEFs reprogramming 100. Also, Nanog in concert with small molecules (for example, oxysterol or purmorphamine) that activate sonic hedgehog (shh) signalling can reprogramme mouse somatic cells, in the absence of exogenous Oct4 79. Thus, Nanog + small molecules might be a promising reprogramming approach. Li et al. reported a chemical activator of Oct4 termed Oct4‐activating compound 1 (OAC1), which up‐regulates Oct4, Nanog and Tet1 expression 101. OAC1‐modified culture condition improves both efficiency and speed of reprogramming, with iPSCs emerging 4 days post‐infection. Treatment of OSKM‐induced cells with OAC1 has yielded more than 20‐fold more iPSCs 101 suggesting OAC1 may be a suitable supplement for improving OSKM‐based reprogramming.

Evidence suggests these SMs have greatest effect when combined. For instance, OSKM‐transfected human myoblasts and fibroblasts had improved reprogramming with the HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate (NaB) and ALK4/5/7 inhibitor SB431542 102. Meanwhile, CHIR99021 and ALK5 inhibitor together have reprogrammed human fibroblasts transfected with Oct4, Sox2, Nanog and Lin28 into a pluripotent state that resembled mESCs 103. Using a cocktail of SB431542, PD0325901 and thiazovivin have improved reprogramming efficiency of OSKM‐transfected human fibroblasts by up to 200‐fold 104. Zhu et al. demonstrated that with Oct4, A‐83‐01, PS48 (3‐phosphoinositide‐dependent kinase‐1), Nab and PD0325901, neonatal human epidermal keratinocytes (nHEKs), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (hUVECs) and amniotic fluid‐derived cells (hAFDCs) could be reprogrammed with significant efficiency 105. Authentic iPSCs from mEFs have been reported using Oct4 followed by treatment with AMI‐5, a protein arginine methyltransferase inhibitor, and A‐83‐01 106. A further potent SM cocktail consisting of VPA, CHIR99021 and 616452 has successfully reprogrammed mouse fibroblasts with Oct4 alone with greater efficiency than with OSKM and OSM 107. Adding tranylcypromine, an H3K4 demethylation inhibitor, to the existing cocktail can further enhance reprogramming efficiencies 107. Wei et al. also reprogrammed mEFs with Oct4 and a SM cocktail comprised of CYT296, VPA, CHIR99021, Parnate and RepSox which improved reprogramming efficiency 91.

Overall, these studies suggest that small molecules are an excellent resource for successful pluripotency reprogramming, and these chemically defined media may produce high‐quality clinical‐grade iPSCs with the least number of RFs and yet a satisfactory yield.

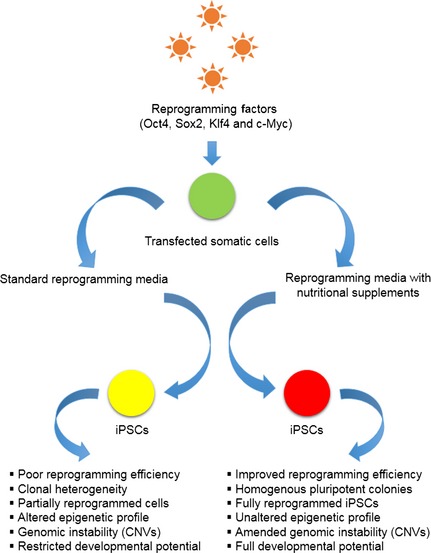

Nutritional supplements for pluripotency reprogramming

Some of the recent studies have sought to address nutritional requirements for pluripotency reprogramming and determined that some common dietary supplements have noteworthy potential for improving reprogramming efficiency and iPSC quality 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114 (Table 3, Fig. 4). For example, butyrate, a natural nutritional supplement and well‐established HDAC inhibitor, improves reprogramming efficiency of OSKM‐transfected human somatic cells such as foetal fibroblasts 108. Sodium butyrate (NaB) treatment has been reported to increase reprogramming efficiency of transfected fibroblasts up to 50‐fold, with overall efficiency of 15–20% hiPSCs, and has greater efficacy than other HDAC inhibitors such as VPA and Trichostatin A (TSA). Even in the absence of c‐Myc or Klf4 transgenes (OSK or OSM), NaB stimulatory effects can increase iPSC yield 108. In addition to NaB HDAC inhibitory effect, NaB facilitates global promoter demethylation which accelerates endogenous pluripotency‐associated gene expression 108. Zhang et al. have shown that NaB promoted iPSC reprogramming by augmenting Oct4‐mediated transcriptional activation of pluripotency‐associated miRNAs, for example, the miR‐302/367 cluster 109, 110. NaB not only promoted transcription and structural stability of the miR‐302/367 cluster but also improved Oct4 transcriptional activity 110. Thus, NaB may be suitable for improving RF‐based reprogramming methods.

Table 3.

Nutritional supplements for pluripotency reprogramming

| Compound | Function | References |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium butyrate (NaB) | Acts as nutritional supplement and HDAC inhibitor. Accelerates endogenous pluripotency gene expression and enhances reprogramming efficiency | 108 |

| Substantially up‐regulates the miR‐302/367 cluster expression through Oct4 | 109 | |

| Enhances transactivity of the Oct4 transactivation domains | 110 | |

| Vitamin C | Alleviates cell senescence by inhibiting p53 and p21 expression, enhances pre‐iPSCs to iPSCs transition, increases reprogramming efficiency | 111 |

| Endows full developmental potential to iPSCs by restoring active chromatin mark [H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3)] at Dlk1‐Dio3 locus | 112 | |

| N‐acetyl‐cysteine (NAC) – antioxidant | Reduces reactive oxygen species (ROS) build‐up and copy number variations (CNV) in resultant iPSCs | 113, 114 |

Figure 4.

Nutritional supplements improve the quality of induced pluripotent stem cells ( iPSC s). Supplementing reprogramming media with nutritional supplements such as Butyrate, vitamin C and antioxidants substantially improves the quality of resultant iPSCs.

Vitamin C (Vc) has also been demonstrated to improve reprogramming of mEFs, human skin fibroblasts and adipose stem cells transduced with OSKM or OSK 111. Its mode of action alleviates cell senescence by reducing p53 and p21 expression while maintaining minimum DNA repair machinery 111. Relatively higher numbers of authentic‐iPSCs following Vc treatment may in part be due to Vc‐mediated transformation of partially reprogrammed pre‐iPSCs into fully reprogrammed iPSCs 111. Furthermore, Stadtfeld et al. demonstrated that Vc treatment substantially improved the quality of iPSCs, reviving full developmental potential and unaltered genomic status 112. Generally, OSKM‐transduced miPSCs bear altered epigenetic signatures at the imprinted Dlk1‐Dio3 gene locus which modulates their ability to generate iPSC‐derived adult mice through tetraploid complementation. However, supplementing reprogramming media with Vc restores H3 lysine 4 trimethylation at Dlk1‐Dio3 loci of the OSKM‐iPSCs, reviving full pluripotency 112.

Also, supplementing reprogramming media with antioxidants, such as N‐acetyl‐cysteine (NAC), can substantially reduce genomic instability of iPSCs, one serious side effect of pluripotency reprogramming 113, 114. NAC tends to inhibit rapid build‐up of reactive oxygen species and reduces de novo copy number variations in OSKM‐iPSCs, due to metabolic shift during early phases of the reprogramming 113.

Thus, optimization of reprogramming culture media with appropriate nutritional supplements needs to be effectively prioritized to ensure clinical‐grade iPSCs.

Chemical reprogramming: a novel approach for iPSCs

Application of small molecules (SMs) is the most recent development in somatic cell reprogramming 86. In continuation of prior studies 86, Hou et al. have reported that a combination of six SMs, VC6TFZ (VPA, CHIR99021, 616452, Tranylcypromine, Forskolin and dznep) reprogrammes mouse embryonic fibroblasts (mEFs) into iPSCs with 2i media 115. These chemically induced pluripotent stem cells (ciPSCs) express typical pluripotency markers. In addition, their gene expression, methylation and histone profiles are similar to mESCs and OSKM‐iPSCs. ciPSCs also exhibit multilineage differentiation potential and germline transmissibility, supporting their complete reprogramming. Addition of TTNPB, a synthetic retinoic acid receptor ligand, significantly improves efficiency of VC6TFZ‐based reprogramming 115. This finding paves the way toward chemically induced pluripotency which overcomes most of the prevailing complexities regarding RF‐based reprogramming and may allow production of footprint‐free clinical‐grade iPSCs.

Potent cell sources for hiPSCs

Induced pluripotency provides an unprecedented opportunity for deriving patient‐specific pluripotent cells from somatic cell lineages. Considering cell origin and epigenomic profile of somatic cells, determine RFs prerequisite and subsequent efficiency of iPSC reprogramming 56, 57; based on previously published studies, we propose four promising candidates for generating patient‐specific hiPSCs – keratinocytes, melanocytes, urine‐derived renal epithelial cells and red blood cells 15, 22, 27, 28, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120.

Human keratinocytes are suitable as they are easily harvested from hair, contain high levels of endogenous Klf4 and c‐Myc transcripts and are readily reprogrammed 116. Compared to fibroblasts, reprogramming of human keratinocytes is more than 100‐fold more efficient with overall reprogramming efficiency close to 1% 15. Keratinocytes are also of epithelial origin and do not require mesenchymal‐to‐epithelial (MET) transition prior to pluripotency induction 15, making them an attractive candidate for clinical‐grade iPSC production.

Human melanocytes are a further candidate, as in addition to OSKM‐based reprogramming, primary melanocytes can be reprogrammed in the absence of exogenous Sox2 27. This occurs as, similar to neuronal precursor cells (NPC), melanocytes are of neuroectodermal origin and express Sox2 endogenously.

Human urine‐derived renal epithelial cells (hRECs) is our third candidate for clinical‐grade hiPSCs 22, 117. In addition to their availability and non‐invasive collection method, hRECs are amenable to reprogramming with high conversion efficiency. OSKM‐transfected hRECs can yield up to 4% urinary iPSCs (UiPSCs) within 5–6 weeks 22, 117. Resultant UiPSCs have typical hESC morphology, expression and epigenetic profiles, and have multilineage differentiation potential. Thus, hRECs could conceivably be a suitable source for patient‐specific hiPSCs.

Reprogramming blood cells – T lymphocytes, CD34 + blood cells, blood mononuclear cells – is potentially the safest and most efficient source of generating patient‐specific hiPSCs 28, 118, 119. Routine venipuncture can supply a sufficient quantity of PB34 (peripheral CD34+ blood cells) or PBMCs (peripheral blood mononuclear cells) with minimal risk to the donor 28, 118. Human PB34 and PBMCs have previously been reprogrammed into hiPSCs with reasonable efficiency 28, 118. With further optimization of reprogramming protocols and culture conditions, PB‐iPSC yield can be improved. Tan et al. recently demonstrated that iPSC reprogramming using small volumes of finger‐prick blood cells can generate authentic hiPSCs using OSKM‐equipped Sendai viruses with reasonable efficiency 120. Convenience of collecting and preparing human finger‐prick blood sample makes it a highly suitable source for generating patient‐specific hiPSCs.

Potential application of hiPSCs

Induced pluripotency (iPSCs) continues to prevail as the best platform for disease modelling, drug screening and regenerative medicine. Increasingly successful derivation of a myriad of disease specific or functional cells from iPSCs and their clinical relevance suggests that a possible boon in stem cell therapy is on the horizon. In this section, we briefly discuss some recent reports concerning in vitro hiPSC differentiation, therapeutic potential and tissue engineering prospects (for focused reviews on iPSC‐based disease modelling and drug screening studies, see refs 123, 124, 125, 126).

Human induced pluripotent stem cells hold great promise for tailored cell‐based therapies. Functional hiPSC derivatives such as astrocytes, dopaminergic neurons, retinal pigment epithelium cells, adipocyte progenitors, insulin‐producing islet‐like clusters, bone substitutes, hepatocytes, melanocytes, erythroblasts, cardiomyocytes and red blood cells have already been generated 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137. Considering damaged tissues account for many chronic illnesses, such as neurodegenerative diseases, retinal degeneration, muscular dystrophy and myocardial infarction, patient‐specific hiPSC derivatives can be a suitable therapeutic choice. These cells appear to exhibit remarkable resilience to in vivo physiological environments and readily acclimatise to cellular homoeostasis. For example, hiPSC‐derived neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) successfully grafted into ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) rat model spinal cords, survived over an extended period following differentiation into mature neurons 138. Similarly, transplantation of hiPSCs‐derived neuroepithelial‐like stem cells (lt‐NES) into striatum or cortex of stroke‐induced mice and rats have markedly recovered motor neuron function 139. Grafted lt‐NES cells acclimatise in host brains without tumourigenesis, survive for prolonged periods, differentiate into mature neurons with electrophysiological properties and develop synaptic connections with host neurons 139. In a study by Lu et al., hiPSCs‐derived multipotent cardiovascular progenitor (MCPs) grafts repopulated decellularized mouse hearts by efficiently differentiating into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells 140. MCP‐engineered heart tissue has been shown to exhibit normal electrophysiological function such as contraction and can respond to chemical treatments 140.

Human induced pluripotent stem cells‐based organ fabrication is a further promising area of regenerative medicine. With successive improvements of artificial scaffolds and 3D culture systems, laboratory‐grown organs may not be far off – at least, studies employing mouse progenitor cells suggest this to be so. For example, Greggio et al. developed a martigel‐based 3D culture system that promotes expansion of mouse embryonic pancreatic progenitors (mPPs) and pancreatic organoid formation in vitro 141. Resultant pancreatic organoids mimiced in vivo pancreas development and differentiated into endocrine‐producing cells. Similarly, Eiraku et al. generated self‐organized optic cup or retinal primordium‐like structures from mouse ESCs, in a modified 3D culture system 142. As cell–cell interaction and niche dependency of progenitor cells greatly influence tissue architecture or morphogenesis, these artificial niche‐3D culture systems may assist with developing personalized organ substitutes from hiPSCs or their functional derivatives.

3D printing technology, a recent addition to the tissue engineering toolkit, has become popular in fabricating complex tissue constructs 143. This bioprinting technique has enabled researchers to craft intricate tissue structures such as vascular channels 144, neocartilage constructs 145 and skin substitutes 146. Biophysiological activity of these 3D‐printed tissues in an in vivo setting, harbingers the prospect of iPSC‐driven organs in the near future.

Conclusions

Induced pluripotent stem cells are an invaluable resource for cell therapy and regenerative medicine. While generating authentic‐iPSCs using a variety of methods is becoming routine, many of the current techniques have not yet been rigorously investigated in convenient human somatic cells. However, growing concern with regard to genomic and epigenomic instability, somatic memory or immunogenicity of iPSCs demands further investigation. We believe optimization of reprogramming protocols and potent cell sorting might enable existing hurdles to be overcome to exploit clinical‐grade iPSCs for upcoming stem cell therapies and regenerative medicine.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to formulate the concept for this review. IKR wrote the manuscript. MEI, MMB and KDI revised the initial manuscript. IKR revised and updated the manuscript according to editorial and reviewers suggestion. AB and JAB read and edited the updated manuscript and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Generation of iPSCs; from different cell types, utilizing different approaches

Acknowledgements

The lead author acknowledges S.M. Abdul‐Awal, Tanveer Ahmed Simon, Biplab Chandra Paul, Mithun Das, Mahmudul Hasan Razib and Md. Furkanur Rahaman Mizan for their support and help regarding this manuscript. Also, special thanks to Basubi Binti Zhilik and Mynul Hasan for their persistent support and encouragement during this work.

References

- 1. Nichols J, Smith A (2012) Pluripotency in the embryo and in culture. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 4, a008128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gurdon JB, Elsdale TR, Fischberg M (1958) Sexually mature individuals of Xenopus laevis from the transplantation of single somatic nuclei. Nature 182, 64–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wabl MR, Brun RB, Du Pasquier L (1975) Lymphocytes of the toad Xenopus laevis have the gene set for promoting tadpole development. Science 190, 1271–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilmut I, Schnieke AE, McWhir J, Kind AJ, Campbell KH (1997) Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature 385, 810–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hu E, Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM (1995) Transdifferentiation of myoblasts by the adipogenic transcription factors ppary and C/ebpa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 9856–9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takahashi K, Yamanaka S (2006) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, et al (2007) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131, 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga‐Otto K, Antosiewicz‐Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, et al (2007) Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S (2007) Generation of germline‐competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 448, 313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, et al (2008) Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wernig M, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Jaenisch R (2008) c‐Myc is dispensable for direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell 2, 10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao XY, Li W, Lv Z, Liu L, Tong M, Hai T, et al (2009) iPS cells produce viable mice through tetraploid complementation. Nature 461, 86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kang L, Wang J, Zhang Y, Kou Z, Gao S (2009) iPS cells can support full‐term development of tetraploid blastocyst‐complemented embryos. Cell Stem Cell 5, 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aoi T, Yae K, Nakagawa M, Ichisaka T, Okita K, Takahashi K, et al (2008) Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse liver and stomach cells. Science 321, 699–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aasen T, Raya A, Barrero MJ, Garreta E, Consiglio A, Gonzalez F, et al (2008) Efficient and rapid generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human keratinocytes. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim JB, Zaehres H, Wu G, Gentile L, Ko K, Sebastiano V, et al (2008) Pluripotent stem cells induced from adult neural stem cells by reprogramming with two factors. Nature 454, 646–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim JB, Sebastiano V, Wu G, Araúzo‐Bravo MJ, Sasse P, Gentile L, et al (2009) Oct4‐induced pluripotency in adult neural stem cells. Cell 136, 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Judson RL, Babiarz J, Venere M, Blelloch R (2009) Embryonic stem cell specific microRNAs promote induced pluripotency. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 459–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsai SY, Clavel C, Kim S, Ang YS, Grisanti L, Lee DF, et al (2010) Oct4 and Klf4 reprogram dermal papilla cells into induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 28, 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giorgetti A, Montserrat N, Aasen T, Gonzalez F, Rodríguez‐Pizà I, Vassena R, et al (2009) Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human cord blood using OCT4 and SOX2. Cell Stem Cell 5, 353–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ruiz S, Brennand K, Panopoulos AD, Herrerías A, Gage FH, Izpisua‐Belmonte JC (2010) High‐efficient generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human astrocytes. PLoS One 5, e15526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhou T, Benda C, Duzinger S, Huang Y, Li X, Li Y, et al (2011) Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from urine. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22, 1221–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Montserrat N, Ramírez‐Bajo MJ, Xia Y, Sancho‐Martinez I, Moya‐Rull D, Miquel‐Serra L, et al (2012) Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human renal proximal tubular cells with only two transcription factors, OCT4 and SOX2. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 24131–24138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Higgins CA, Itoh M, Inoue K, Richardson GD, Jahoda CA, Christiano AM (2012) Reprogramming of human hair follicle dermal papilla cells into induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 1725–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liao J, Wu Z, Wang Y, Cheng L, Cui C, Gao Y, et al (2008) Enhanced efficiency of generating induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells from human somatic cells by a combination of six transcription factors. Cell Res. 18, 600–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hanna J, Markoulaki S, Schorderet P, Carey BW, Beard C, Wernig M, et al (2008) Direct reprogramming of terminally differentiated mature B lymphocytes to pluripotency. Cell 133, 250–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Utikal J, Maherali N, Kulalert W, Hochedlinger K (2009) Sox2 is dispensable for the reprogramming of melanocytes and melanoma cells into induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Cell Sci. 122, 3502–3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Loh YH, Hartung O, Li H, Guo C, Sahalie JM, Manos PD, et al (2010) Reprogramming of T Cells from human peripheral blood. Cell Stem Cell 7, 15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang Y, Liu J, Tan X, Li G, Gao Y, Liu X, et al (2013) Induced pluripotent stem cells from human hair follicle mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 9, 451–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sommer CA, Stadtfeld M, Murphy GJ, Hochedlinger K, Kotton DN, Mostoslavsky G (2009) Induced pluripotent stem cell generation using a single lentiviral stem cell cassette. Stem Cells 27, 543–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carey BW, Markoulaki S, Hanna J, Saha K, Gao Q, Mitalipova M, et al (2009) Reprogramming of murine and human somatic cells using a single polycistronic vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 157–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sommer CA, Sommer AG, Longmire TA, Christodoulou C, Thomas DD, Gostissa M, et al (2010) Excision of reprogramming transgenes improves the differentiation potential of iPS cells generated with a single excisable vector. Stem Cells 28, 64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Awe JP, Lee PC, Ramathal C, Vega‐Crespo A, Durruthy‐Durruthy J, Cooper A, et al (2013) Generation and characterization of transgene‐free human induced pluripotent stem cells and conversion to putative clinical‐grade status. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 4, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stadtfeld M, Nagaya M, Utikal J, Weir G, Hochedlinger K (2008) Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science 322, 945–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhou W, Freed CR (2009) Adenoviral gene delivery can reprogram human fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 27, 2667–2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fusaki N, Ban H, Nishiyama A, Saeki K, Hasegawa M (2009) Efficient induction of transgene‐free human pluripotent stem cells using a vector based on Sendai virus, an RNA virus that does not integrate into the host genome. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 85, 348–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ono M, Hamada Y, Horiuchi Y, Matsuo‐Takasaki M, Imoto Y, Satomi K, et al (2012) Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human nasal epithelial cells using a Sendai virus vector. PLoS One 7, e42855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seki T, Yuasa S, Oda M, Egashira T, Yae K, Kusumoto D, et al (2010) Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human terminally differentiated circulating T cells. Cell Stem Cell 7, 11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ban H, Nishishita N, Fusaki N, Tabata T, Saeki K, Shikamura M, et al (2011) Efficient generation of transgene‐free human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by temperature‐sensitive Sendai virus vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14234–14239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yu J, Hu K, Smuga‐Otto K, Tian S, Stewart R, Slukvin II, et al (2009) Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequence. Science 324, 797–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hu K, Yu J, Suknuntha K, Tian S, Montgomery K, Choi KD, et al (2011) Efficient generation of transgene‐free induced pluripotent stem cells from normal and neoplastic bone marrow and cord blood mononuclear cells. Blood 117, e109–e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chou BK, Mali P, Huang X, Ye Z, Dowey SN, Resar LM, et al (2011) Efficient human iPS cell derivation by a non‐integrating plasmid from blood cells with unique epigenetic and gene expression signatures. Cell Res. 21, 518–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jia F, Wilson KD, Sun N, Gupta DM, Huang M, Li Z, et al (2010) A nonviral minicircle vector for deriving human iPS cells. Nat. Methods 7, 197–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yoshioka N, Gros E, Li HR, Kumar S, Deacon DC, Maron C, et al (2013) Efficient generation of human iPSCs by a synthetic self‐replicative RNA. Cell Stem Cell 13, 246–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hiratsuka M, Uno N, Ueda K, Kurosaki H, Imaoka N, Kazuki K, et al (2011) Integration‐free iPS cells engineered using human artificial chromosome vectors. PLoS One 6, e25961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Woltjen K, Michael IP, Mohseni P, Desai R, Mileikovsky M, Hämäläinen R, et al (2009) Piggybac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 458, 766–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Davis RP, Nemes C, Varga E, Freund C, Kosmidis G, Gkatzis K, et al (2013) Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human foetal fibroblasts using the Sleeping Beauty transposon gene delivery system. Differentiation 86, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Khan M, Narayanan K, Lu H, Choo Y, Du C, Wiradharma N, et al (2013) Delivery of reprogramming factors into fibroblasts for generation of non‐genetic induced pluripotent stem cells using a cationic bolaamphiphile as a non‐viral vector. Biomaterials 34, 5336–5343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tavernier G, Wolfrum K, Demeester J, De Smedt SC, Adjaye J, Rejman J (2012) Activation of pluripotency‐associated genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts by non‐viral transfection with in vitro‐derived mRNAs encoding Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and cMyc. Biomaterials 33, 412–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sohn YD, Somasuntharam I, Che PL, Jayswal R, Murthy N, Davis ME, et al (2013) Induction of pluripotency in bone marrow mononuclear cells via polyketal nanoparticle‐mediated delivery of mature microRNAs. Biomaterials 34, 4235–4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, Loh YH, Li H, Lau F, et al (2010) Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell 7, 618–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Miyoshi N, Ishii H, Nagano H, Haraguchi N, Dewi DL, Kano Y, et al (2011) Reprogramming of mouse and human cells to pluripotency using mature microRNAs. Cell Stem Cell 8, 633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim D, Kim CH, Moon JI, Chung YG, Chang MY, Han BS, et al (2009) Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell Stem Cell 4, 472–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cho HJ, Lee CS, Kwon YW, Paek JS, Lee SH, Hur J, et al (2010) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult somatic cells by protein‐based reprogramming without genetic manipulation. Blood 116, 386–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Anokye‐Danso F, Trivedi CM, Juhr D, Gupta M, Cui Z, Tian Y, et al (2011) Highly efficient miRNA‐mediated reprogramming of mouse and human somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 8, 376–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Masip M, Veiga A, Izpisúa Belmonte JC, Simón C (2010) Reprogramming with defined factors: from induced pluripotency to induced transdifferentiation. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 16, 856–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hussein SM, Nagy AA (2012) Progress made in the reprogramming field: new factors, new strategies and a new outlook. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pelengaris S, Khan M, Evan G (2002) c‐MYC: more than just a matter of life and death. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 764–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Prochownik EV, Li Y (2007) The ever expanding role for c‐Myc in promoting genomic instability. Cell Cycle 6, 1024–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhao Y, Yin X, Qin H, Zhu F, Liu H, Yang W, et al (2008) Two supporting factors greatly improve the efficiency of human iPSC generation. Cell Stem Cell 3, 475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Marson A, Foreman R, Chevalier B, Bilodeau S, Kahn M, Young RA, et al (2008) Wnt Signaling Promotes Reprogramming of Somatic Cells to Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 3, 132–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Maekawa M, Yamaguchi K, Nakamura T, Shibukawa R, Kodanaka I, Ichisaka T, et al (2011) Direct reprogramming of somatic cells is promoted by maternal transcription factor Glis1. Nature 474, 225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Liang G, He J, Zhang Y (2012) Kdm2b promotes induced pluripotent stem cell generation by facilitating gene activation early in reprogramming. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 457–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chiou SH, Jiang BH, Yu YL, Chou SJ, Tsai PH, Chang WC, et al (2013) Poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase 1 regulates nuclear reprogramming and promotes iPSC generation without c‐Myc. J. Exp. Med. 210, 85–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Han J, Yuan P, Yang H, Zhang J, Soh BS, Li P, et al (2010) Tbx3 improves the germ‐line competency of induced pluripotent stem cell. Nature 463, 1096–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Declercq J, Sheshadri P, Verfaillie CM, Kumar A (2013) Zic3 enhances the generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 2017–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kumar A, Declercq J, Eggermont K, Agirre X, Prosper F, Verfaillie CM (2012) Zic3 induces conversion of human fibroblasts to stable neural progenitor‐like cells. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hirata T, Amano T, Nakatake Y, Amano M, Piao Y, Hoang HG, et al (2012) Zscan4 transiently reactivates early embryonic genes during the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2, 208. doi: 10.1038/srep00208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Jiang J, Lv W, Ye X, Wang L, Zhang M, Yang H, et al (2013) Zscan4 promotes genomic stability during reprogramming and dramatically improves the quality of iPS cells as demonstrated by tetraploid complementation. Cell Res. 23, 92–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yang P, Wang Y, Chen J, Li H, Kang L, Zhang Y, et al (2011) RCOR2 is a subunit of the LSD1 complex that regulates ESC property and substitutes for SOX2 in reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotency. Stem Cells 29, 791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Feng B, Jiang J, Kraus P, Ng JH, Heng JC, Chan YS, et al (2009) Reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells with orphan nuclear receptor Esrrb. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chen J, Liu J, Yang J, Chen Y, Chen J, Ni S, et al (2011) BMPs functionally replace Klf4 and support efficient reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts by Oct4 alone. Cell Res. 21, 205–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ying QL, Nichols J, Chambers I, Smith A (2003) BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self‐renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell 115, 281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Xu RH, Chen X, Li DS, Li R, Addicks GC, Glennon C, et al (2002) BMP4 initiates human embryonic stem cell differentiation to trophoblast. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 1261–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Moon JH, Heo JS, Kim JS, Jun EK, Lee JH, Kim A, et al (2011) Reprogramming fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells with Bmi1. Cell Res. 21, 1305–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Moon JH, Heo JS, Kwon S, Kim J, Hwang J, Kang PJ, et al (2012) Two‐step generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from mouse fibroblasts using Id3 and Oct4. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, Segawa K, Murakami M, Takahashi K, et al (2003) The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse Epiblast and ES cells. Cell 113, 631–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hyslop L, Stojkovic M, Armstrong L, Walter T, Stojkovic P, Przyborski S, et al (2005) Downregulation of NANOG induces differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to extraembryonic lineages. Stem Cells 23, 1035–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Moon JH, Yun W, Kim J, Hyeon S, Kang PJ, Park G, et al (2013) Reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells with Nanog. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 431, 444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Redmer T, Diecke S, Grigoryan T, Quiroga‐Negreira A, Birchmeier W, Besser D (2011) E‐cadherin is crucial for embryonic stem cell pluripotency and can replace OCT4 during somatic cell reprogramming. EMBO Rep. 12, 720–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Heng JC, Feng B, Han J, Jiang J, Kraus P, Ng JH, et al (2010) The nuclear receptor Nr5a2 can replace Oct4 in the reprogramming of murine somatic cells to pluripotent cells. Cell Stem Cell 6, 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Gao Y, Chen J, Li K, Wu T, Huang B, Liu W, et al (2013) Replacement of Oct4 by Tet1 during iPSC induction reveals an important role of DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 12, 453–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Huang HP, Chen PH, Yu CY, Chuang CY, Stone L, Hsiao WC, et al (2011) Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule (EpCAM) Complex Proteins Promote Transcription Factor‐mediated Pluripotency Reprogramming. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 33520–33532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Shah SN, Kerr C, Cope L, Zambidis E, Liu C, Hillion J, et al (2012) HMGA1 reprograms somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells by inducing stem cell transcriptional networks. PLoS One 7, e48533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Fischedick G, Klein DC, Wu G, Esch D, Höing S, Han DW, et al (2012) Zfp296 is a novel, pluripotent‐specific reprogramming factor. PLoS One 7, e34645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Su JB, Pei DQ, Qin BM (2013) Roles of small molecules in somatic cell reprogramming. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 34, 719–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Huangfu D, Osafune K, Maehr R, Guo W, Eijkelenboom A, Chen S, et al (2008) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from primary human fibroblasts with only Oct4 and Sox2. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Huangfu D, Maehr R, Guo W, Eijkelenboom A, Snitow M, Chen AE, et al (2008) Induction of pluripotent stem cells by defined factors is greatly improved by small‐molecule compounds. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 795–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Onder TT, Kara N, Cherry A, Sinha AU, Zhu N, Bernt KM, et al (2012) Chromatin modifying enzymes as modulators of reprogramming. Nature 483, 598–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Lee J, Xia Y, Son MY, Jin G, Seol B, Kim MJ, et al (2012) A novel small molecule facilitates the reprogramming of human somatic cells into a pluripotent state and supports the maintenance of an undifferentiated state of human pluripotent stem cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 12509–11253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wei X, Chen Y, Xu Y, Zhan Y, Zhang R, Wang M, et al (2014) Small molecule compound induces chromatin de‐condensation and facilitates induced pluripotent stem cell generation. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 409–420. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mju024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Li Z, Rana TM (2012) A kinase inhibitor screen identifies small‐molecule enhancers of reprogramming and iPS cell generation. Nat. Commun. 3, 1085. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Shi Y, Do JT, Desponts C, Hahm HS, Schöler HR, Ding S (2008) A combined chemical and genetic approach for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2, 525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Polo JM, Anderssen E, Walsh RM, Schwarz BA, Nefzger CM, Lim SM, et al (2012) A molecular roadmap of reprogramming somatic cells into iPS cells. Cell 151, 1617–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Li W, Zhou H, Abujarour R, Zhu S, Young Joo J, Lin T, et al (2009) Generation of human‐induced pluripotent stem cells in the absence of exogenous Sox2. Stem Cells 27, 2992–3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Staerk J, Lyssiotis CA, Medeiro LA, Bollong M, Foreman RK, Zhu S, et al (2011) Pan‐Src family kinase inhibitors replace Sox2 during the direct reprogramming of somatic cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 5734–5736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Maherali N, Hochedlinger K (2009) Tgfb signal inhibition cooperates in the induction of iPSCs and replaces Sox2 and cMyc. Curr. Biol. 19, 1718–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Lyssiotis CA, Foreman RK, Staerk J, Garcia M, Mathur D, Markoulaki S, et al (2009) Reprogramming of murine fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells with chemical complementation of Klf4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8912–8917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ichida JK, Blanchard J, Lam K, Son EY, Chung JE, Egli D, et al (2009) A small‐molecule inhibitor of tgf‐Beta signaling replaces sox2 in reprogramming by inducing nanog. Cell Stem Cell 5, 491–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Shi Y, Desponts C, Do JT, Hahm HS, Schöler HR, Ding S (2008) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts by Oct4 and Klf4 with small‐molecule compounds. Cell Stem Cell 3, 568–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Li W, Tian E, Chen ZX, Sun G, Ye P, Yang S, et al (2012) Identification of Oct4‐activating compounds that enhance reprogramming efficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 20853–20858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Trokovic R, Weltner J, Manninen T, Mikkola M, Lundin K, Hämäläinen R, et al (2013) Small molecule inhibitors promote efficient generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human skeletal myoblasts. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Li W, Wei W, Zhu S, Zhu J, Shi Y, Lin T, et al (2009) Generation of rat and human induced pluripotent stem cells by combining genetic reprogramming and chemical inhibitors. Cell Stem Cell 4, 16–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Lin T, Ambasudhan R, Yuan X, Li W, Hilcove S, Abujarour R, et al (2009) A chemical platform for improved induction of human iPSCs. Nat. Methods 6, 805–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Zhu S, Li W, Zhou H, Wei W, Ambasudhan R, Lin T, et al (2010) Reprogramming of human primary somatic cells by OCT4 and chemical compounds. Cell Stem Cell 7, 651–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Yuan X, Wan H, Zhao X, Zhu S, Zhou Q, Ding S (2011) Brief report: combined chemical treatment enables Oct4‐induced reprogramming from mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Stem Cells 29, 549–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Li Y, Zhang Q, Yin X, Yang W, Du Y, Hou P, et al (2011) Generation of iPSCs from mouse fibroblasts with a single gene, Oct4, and small molecules. Cell Res. 21, 196–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Mali P, Chou BK, Yen J, Ye Z, Zou J, Dowey S, et al (2010) Butyrate greatly enhances derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by promoting epigenetic remodeling and the expression of pluripotency‐associated genes. Stem Cells 28, 713–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Zhang Z, Wu WS (2013) Sodium butyrate promotes generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells through induction of the miR302/367 cluster. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 2268–2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Zhang Z, Xiang D, Wu WS (2014) Sodium butyrate facilitates reprogramming by derepressing OCT4 transactivity at the promoter of embryonic stem cell‐specific miR‐302/367 cluster. Cell Reprogram 16, 130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Esteban MA, Wang T, Qin B, Yang J, Qin D, Cai J, et al (2010) Vitamin C enhances the generation of mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6, 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Stadtfeld M, Apostolou E, Ferrari F, Choi J, Walsh RM, Chen T, et al (2012) Ascorbic acid prevents loss of Dlk1‐Dio3 imprinting and facilitates generation of all‐iPS cell mice from terminally differentiated B cells. Nat. Genet. 44, S1–S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Ji J, Sharma V, Qi S, Guarch ME, Zhao P, Luo Z, et al (2014) Antioxidant supplementation reduces genomic aberrations in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports 2, 44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Luo L, Kawakatsu M, Guo CW, Urata Y, Huang WJ, Ali H, et al (2014) Effects of antioxidants on the quality and genomic stability of induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Rep. 4, 3779. doi: 10.1038/srep03779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Hou P, Li Y, Zhang X, Liu C, Guan J, Li H, et al (2013) Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small‐molecule compounds. Science 341, 651–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Aasen T, Izpisúa Belmonte JC (2010) Isolation and cultivation of human keratinocytes from skin or plucked hair for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 5, 371–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Zhou T, Benda C, Dunzinger S, Huang Y, Ho JC, Yang J, et al (2012) Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from urine samples. Nat. Protoc. 7, 2080–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Merling RK, Sweeney CL, Choi U, De Ravin SS, Myers TG, Otaizo‐Carrasquero F, et al (2013) Transgene‐free iPSCs generated from small volume peripheral blood nonmobilized CD34 cells. Blood 121, e98–e107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Ye L, Muench MO, Fusaki N, Beyer AI, Wang J, Qi Z, et al (2013) Blood cell‐derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of reprogramming factors generated by Sendai viral vectors. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2, 558–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Tan HK, Toh CX, Ma D, Yang B, Liu TM, Lu J, et al (2014) Human finger‐prick induced pluripotent stem cells facilitate the development of stem cell banking. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 3, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Kishino Y, Seki T, Fujita J, Yuasa S, Tohyama S, Kunitomi A, et al (2014) Derivation of transgene‐free human induced pluripotent stem cells from human peripheral T cells in defined culture conditions. PLoS One 9, e97397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Wang Y, Chen J, Hu JL, Wei XX, Qin D, Gao J, et al (2011) Reprogramming of mouse and human somatic cells by high‐performance engineered factors. EMBO Rep. 12, 373–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Trounson A, Shepard KA, DeWitt ND (2012) Human disease modeling with induced pluripotent stem cells. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Pomp O, Colman A (2013) Disease modelling using induced pluripotent stem cells: status and prospects. Bioessays 35, 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Ko HC, Gelb BD (2014) Concise review: drug discovery in the age of the induced pluripotent stem cell. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 3, 500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Inoue H, Nagata N, Kurokawa H, Yamanaka S (2014) iPS cells: a game changer for future medicine. EMBO J. 33, 409–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Mormone E, D'Sousa S, Alexeeva V, Bederson MM, Germano IM (2014) “Footprint‐free” human induced Pluripotent Stem Cell‐derived astrocytes for in vivo cell‐based therapy. Stem Cells Dev. 23, 2626–2636. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Theka I, Caiazzo M, Dvoretskova E, Leo D, Ungaro F, Curreli S, et al (2013) Rapid generation of functional dopaminergic neurons from human induced pluripotent stem cells through a single‐step procedure using cell lineage transcription factors. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2, 473–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Kamao H, Mandai M, Okamoto S, Sakai N, Suga A, Sugita S, et al (2014) Characterization of human induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived retinal pigment epithelium cell sheets aiming for clinical application. Stem Cell Reports. 2, 205–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Mohsen‐Kanson T, Hafner AL, Wdziekonski B, Takashima Y, Villageois P, Carrière A, et al (2014) Differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells into brown and white adipocytes: role of Pax3. Stem Cells 32, 1459–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Shaer A, Azarpira N, Vahdati A, Karimi MH, Shariati M (2014) Differentiation of Human‐Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Into Insulin‐Producing Clusters. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2014 Jan 13. doi: 10.6002/ect.2013.0131. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. de Peppo GM, Marcos‐Campos I, Kahler DJ, Alsalman D, Shang L, Vunjak‐Novakovic G, et al (2013) Engineering bone tissue substitutes from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 8680–8685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Ma X, Duan Y, Tschudy‐Seney B, Roll G, Behbahan IS, Ahuja TP, et al (2013) Highly efficient differentiation of functional hepatocytes from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2, 409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Jones JC, Sabatini K, Liao X, Tran HT, Lynch CL, Morey RE, et al (2013) Melanocytes derived from transgene‐free human induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 2104–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Yang CT, French A, Goh PA, Pagnamenta A, Mettananda S, Taylor J, et al (2014) Human induced pluripotent stem cell derived erythroblasts can undergo definitive erythropoiesis and co‐express gamma and beta globins. Br. J. Haematol. 166, 435–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Blazeski A, Zhu R, Hunter DW, Weinberg SH, Zambidis ET, Tung L (2012) Cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells as models for normal and diseased cardiac electrophysiology and contractility. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 110, 166–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Dias J, Gumenyuk M, Kang H, Vodyanik M, Yu J, Thomson JA, et al (2011) Generation of red blood cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 20, 1639–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]