Abstract

Sodium butyrate (NaB), a product of colonic fermentation of dietary fibre, has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation by blocking cells in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle through a mechanism of action still not completely understood. We investigated the effect of NaB on the level of some G1 phase‐related proteins in a colon carcinoma cell line (HT29). In particular, we addressed our attention to cyclin D1 (the key regulator of G1S progression), p21waf1/cip1 (the main inactivator of the cyclin D/cdk complex), and p53 (the most important regulator of p21waf1/cip1 gene transcription). At inhibitory concentrations (higher than 1 mM) NaB reduced cyclin D1 and p53 level in a dose‐dependent manner and sustained the synthesis of p21waf1/cip1, probably in a p53‐independent way, accounting for the G0/G1 block observed by flow cytometry. Present results provide further evidence on the molecular mechanism at the basis of the physiological role of NaB and support the hypothesis that an unbalanced diet, poor in carbohydrates and therefore in NaB, could result in functional alterations with clinical and carcinogenic implications.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer deaths in Western populations (Parker et al. 1996), and its occurrence is commonly ascribed to the transformation of normal colonic epithelium to adenomatous polyps and ultimately invasive cancer. According to the model proposed by Fearon & Vogelstein (1990), cancer develops as a consequence of genetic alterations, including mutations of the p53 gene, which accumulate over one or two decades (Gryfe et al. 1997). Epidemiological and experimental data have linked dietary composition with colorectal carcinogenesis: a high intake of animal fat providing an increased risk, and a high intake of dietary fibre providing a protection against cancer (Potter 1996). Metabolism by colonic bacterial flora of dietary fibre (i.e. complex carbohydrates) generates a high concentration (60‐150 mM) of short‐chain fatty acids, the most representative of which is sodium butyrate (NaB) (Jacobs 1987; Hill 1995). In vivo experiments have suggested that NaB could play a pivotal role in the maintenance of the normal colonic epithelium turnover, because its decreased levels appear to be associated with alterations in cell growth and dedifferentiation observed in the adenomacarcinoma sequence (McIntyre, Gibson & Young, 1993; Whiteley et al. 1996).

Several studies have investigated the effect of NaB on normal fibroblasts (Janson, Brander & Siegel, 1997; Vaziri et al. 1998) and epithelial cells from the gastrointestinal tract (Litvak et al. 1998) as well as on cell lines from different human tumours (Heerdt et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1998). Results indicate that the compound exerts a wide variety of effects (Prasad 1980) on cellular morphology (Rephaeli et al. 1994), cell proliferation (Coradini et al. 1997) and expression of many genes (Smith, Yokoyama & German, 1998), including some oncogenes (Krupitza et al. 1996). Moreover, NaB is known to inhibit histone deacetylase (Boffa et al. 1978) and to induce apoptosis (Conway et al. 1995; Boisteau et al. 1996). However, its molecular mechanism of action is still unclear.

When treated with millimolar concentrations of NaB, most cell types undergo growth arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Guilbaud et al. 1990; Takahashi & Parsons 1990; Saito et al. 1991), hence we investigated the effect of NaB on the level of some G1 phase‐related proteins in the HT29 colon carcinoma cell line with a mutant p53 gene (Shao et al. 1997). In particular, we addressed our attention to the simultaneous consideration of cyclin D1 (the key regulator of G1S progression (Hamel & Hanley‐Hyde 1997)), p21waf1/cip1 (the main inactivator of the cyclin D/cdk4 (cdk6) complex (Serrano, Hannon & Beach, 1993)), and p53 (the most important regulator of p21waf1/cip1; gene transcription (el‐Deiry et al. 1993, Li et al. 1994)) to elucidate whether NaB affects the interrelation among these cell cycle‐related proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

HT29 colon cancer cells were grown as a monolayer in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (v/v) and with 1% glutamine (Sigma), cultured in T‐75 cm2 plastic flasks (Corning Industries, Corning, NY, USA), maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere, and passaged weekly. At the beginning of the experiments, cells in exponential growth phase were removed from the flasks with a 0.05% trypsin‐0.02% EDTA solution.

Cell Proliferation Experiments

Cells were seeded in 24 well/plate (50 000 cells/well) in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal calf serum. The cells were allowed to attach for 24 h, and seeding medium was removed and replaced by experimental medium. Cells were maintained for 3 days in medium supplemented with increasing concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 mM) of NaB (ICN Biomedicals, South Chillicothe, Ohio), and the effect on cell growth was evaluated by the colourimetric MTT (3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2yl)‐2,5‐diphenyl‐tetrazolium bromide, Sigma) assay (Twentyman & Luscombe 1987). At the selected times, MTT (5 mg/ml) was added to each well for 4 h. Formazan precipitates were dissolved in 1 ml dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma), and adsorbance was measured at 550 nm using an ELx800 photometer (Bio‐Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Wells containing all admixtures except cells were used as blanks. The experiments were carried out at least twice, and each sample was run in quadruplicate by using a 4 × 4 factorial design.

Flow Cytometric Determination

Cell cycle perturbations were determined in triplicate samples after 24, 48 and 72 h of NaB treatment at the concentrations of 1, 2 and 4 mM. Cells were washed and harvested with trypsin, and samples of 1 × 106 cells were stained in a solution containing 50 µg/ml propidium iodide (PI, ICN), RNase (100 kU/ml, ICN) and 0.05% Nonidet P40 (Sigma) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The fluorescence of stained cells was measured using a FACscan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) equipped with an argon laser at 488 nm wavelength excitation and a 610‐nm filter for PI fluorescence detection. The red (PI) fluorescence signal was collected in linear mode. Data were acquired and processed in Lysis II software (Becton Dickinson), and a minimum of 104 cells was measured for each sample. The percentage of cells in the different cycle phases was evaluated on DNA linear plots using CellFit software according to the SOBR model (Becton Dickinson).

Preparation of Cell Extract and Western Blotting

Total extracts were obtained from cells treated with scalar concentrations of NaB (0.1, 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 mM) for 3 days. Cells were rinsed twice with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) at 4 °C and centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min. Cells were lysed in 0.1 ml of buffer (50 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 10 µg/ml aprotinin, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml pepstatin, 1 mM phenyl‐methane‐sulphonylfluoride, and 1% Triton × 100, ICN) and incubated for 1 h on ice; a 5‐µl aliquot was used to determine protein concentration by the Bradford microassay kit (Life Science Research Bio‐Rad, Segrate, Italy). Samples were then adjusted with an appropriate volume of sample buffer and subjected to electrophoresis on discontinuous minigel with a 9% sodium dodecyl sulphate acrylamide‐bisacrylamide (30–0.8%) running gel at 100 V for 2.5 h. The gel was equilibrated in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris base, 192 mM glycine and 10% methanol) and then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Life Science Research Bio‐Rad) at 4 °C overnight. The membrane was equilibrated in transfer buffer and blocked for 1 h with 5% milk in PBS. Protein expression was detected by immunoblotting with primary mouse monoclonal antibodies against the different antigens, namely: human cyclin D1 and p21waf1/cip1 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA); PAb 1801 (Cimbus Bioscience, Chandler Ford, Hampshire, UK). The inside control for each sample loaded in the gel was represented by proliferation cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), whose expression was unaffected by NaB treatment (Joensuu & Mester 1994) and was detected with an anti‐PCNA mouse monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The membrane was successively washed with PBS and incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, and immune complexes were detected by using the ECL chemoluminescent system (Amersham, Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK), which impressed the Hyperfilm X‐ray (Amersham). Bands were detected by a ScanJET IIcx/T (Hewlett Packard Co., Greeley, CO, USA), quantified by MD ImageQuant Software (Molecular Dynamics) and normalized according to the internal standard. Results represent the mean of at least three independent experiments.

RESULTS

Effect on Cell Growth and the Cell Cycle

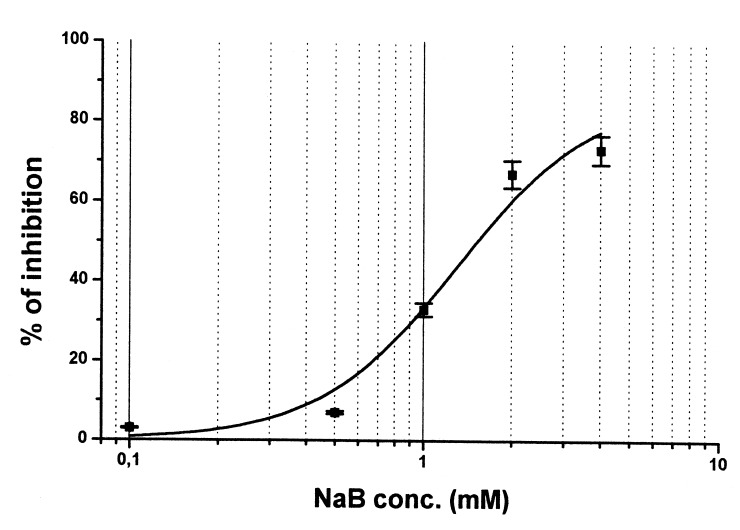

As shown in Fig. 1, a 3‐day treatment NaB induced a dose‐dependent reduction of HT29 cell growth, with an approximate 75% inhibition with respect to the control at the highest concentration (4 mm). Under such experimental conditions, NaB showed an IC50 value equal to 1.6 mM. The inhibitory effect was further increased by prolonging the treatment: a 6‐day treatment with 4 mm NaB improved cell growth inhibition by 10–15% (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Dose—effect curve of a 3‐day treatment with NaB on HT29 cells. Experimental points are the means (±SD) of four replicates. For details see Materials and methods.

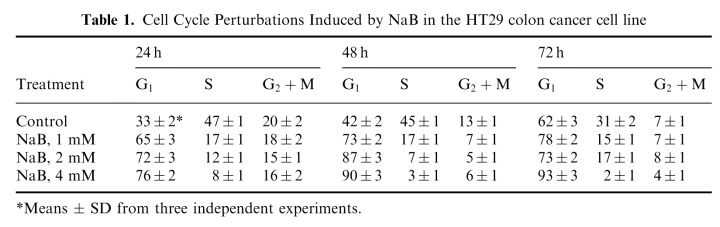

Perturbations induced by NaB on the distribution of HT29 cells in the different cell cycle phases after 24, 48 and 72 h of treatment with NaB at the concentration of 1, 2 and 4 mM are reported in Table 1. As expected, a dose‐dependent G0/G1 block, which persisted over time, was observed. Already after a 24‐h treatment with 4 mM NaB, 76% of cells were blocked in the G0/G1 phase.

Table 1.

Cell Cycle Perturbations Induced by NaB in the HT29 colon cancer cell line

Effect on the Expression of Cell Cycle‐Related Proteins

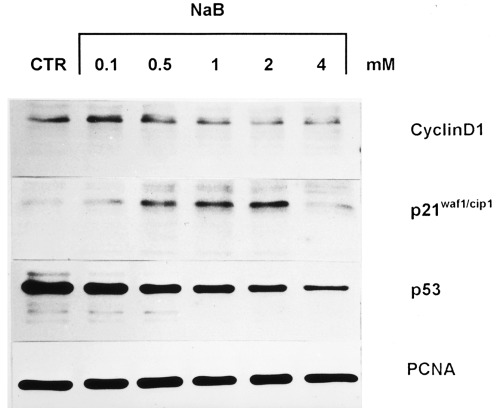

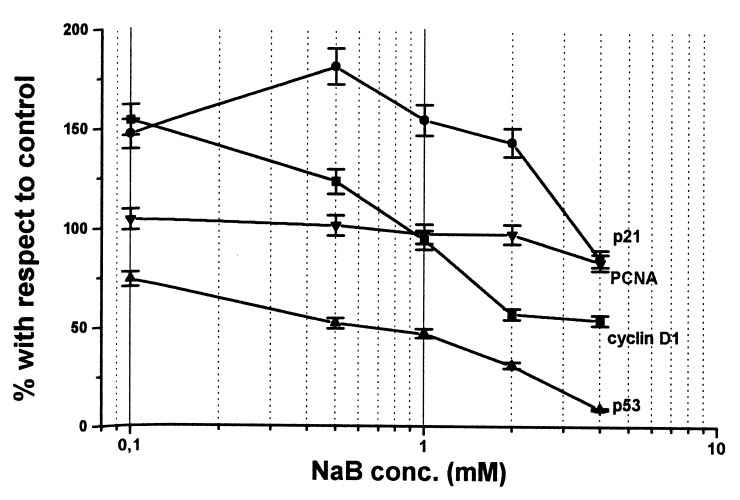

Figure 2 shows the effect of a 3‐day treatment with scalar concentrations of NaB on the level of cyclin D1, p21waf1/cip1 and p53 protein, investigated by Western blotting analysis. With respect to control, all protein levels were modulated by NaB treatment although in a different manner. In fact, as shown in Fig. 3 (obtained by densitometric analysis), the lowest NaB concentration increased cyclin D1 (+ 54%) and p21waf1/cip1 (+ 47%) levels. In the presence of 0.5 mM NaB, p21waf1/cip1 further increased (+ 81%), whereas cyclin D1 slightly decreased (+ 23% with respect to control). A concentration of NaB equal to or higher than 1 mM induced a further decrease in cyclin D1 and a slight decrease in p21waf1/cip1. In the presence of the highest NaB concentration, a 50% inhibition with respect to control was observed for cyclin D1, whereas p21waf1/cip1 reached the control value.

Figure 2.

Modulatory effect of scalar concentration (0.1–4 mM) of NaB on the level of cyclin D1, 21waf1/cip1 and p53 analysed by Western blot. For details see Materials and methods.

Figure 3.

Densitometric quantification of NaB‐treated samples. Results represent the means of three independent experiments.

As regards p53, which proved to be mutated in the HT29 cell line by sequencing analysis, NaB decreased protein level in a dose‐dependent manner. At the highest concentration, NaB reduced p53 level to 90% with respect to control.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that NaB inhibits HT29 cell growth in a dose‐dependent manner and that growth inhibition is strictly related to a persistent block of cells in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle and to alterations in some cell cycle‐related proteins. It is well known that the G0/G1 block induced by NaB is related to a down‐regulation of genes and oncogenes involved in cell proliferation (Krupitza et al. 1996; Smith et al. 1998). In fact, there is a substantial body of evidence that the expression of some oncogenes, such as c‐myc and c‐fos, is negatively modulated by NaB. Also in our experimental system we were able to reproduce the results obtained by Souleimani & Asselin (1993), in terms of an early down‐regulation of c‐myc and c‐fos oncoproteins within 30 min of treatment (unpublished data). The down‐regulation of cyclin D1, found in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of NaB (higher than 1 mM), could also account for the two‐fold accumulation of cells in the G1 phase with respect to the control, already observed after 24 h of a 1‐mM NaB treatment.

The increase in p21waf1/cip1, induced by the same concentrations of NaB which affected cyclin D1, is in accord with results of cytometric analysis and in agreement with Archer et al. (1998), who demonstrated an association between overexpression of p21waf1/cip1 and growth arrest in a similar experimental system. The finding is particularly interesting since in the progression from normal mucosa to colon adenocarcinoma, p21waf1/cip1 expression proved to be related inversely to proliferation and directly to terminal differentiation (Doglioni et al. 1996). Therefore, NaB, which is known to be a differentiation inducer, could increase p21waf1/cip1 expression, block the activity of cdk‐cyclin complexes, and cause cell cycle arrest, thereby supporting a causal role for p21waf1/cip1 as a link between a high‐fibre diet and the prevention of colon carcinogenesis.

The observation that at low concentrations NaB increased cyclin D1 level is not surprising in light of its physiological role. In fact, in colonic crypts, low concentrations of NaB cause an enhanced proliferation of epithelial cells at the base accompanied by a progressive migration towards the apex, where due to the increased NaB concentration, cells first differentiate and then activate apoptosis (Jacobs 1987; Hill 1995). The present results suggest that NaB could play a dose‐dependent role in maintaining homeostasis in colonic epithelial cells, by regulating the balance between proliferative activity (through induction of cyclin D1) and cell arrest (through induction of p21waf1/cip1).

As regards the mechanism of action through which NaB up‐regulates p21waf1/cip1 expression, the present results seem to suggest a p53‐independent pathway, since, in accord with Palmer, Paraskeva & Williams, (1997) we observed a down‐regulation in p53 level after in vitro treatment. The finding is not surprising, since although p21waf1/cip1; has been identified as one of the transcriptional targets of wild type p53 (el‐Deiry et al. 1993), experimental evidence suggests that transcription of the WAF1/CIP1 gene can also be regulated via a p53‐independent pathway (Biggs, Kudlow & Kraft, 1996). Such a p53‐independent activation of p21waf1/cip1 is not an unusual finding, since it can be induced also by transforming growth factor b. In fact, although p53 is a sequence‐specific DNA‐binding protein that is active as a transcription factor, transforming growth factor can act by means of other transcription factors, such as Sp1 (Datto et al. 1995).

In conclusion, the present results provide some evidence to elucidate the molecular mechanisms at the basis of the physiological role of NaB and to explain why an unbalanced diet, poor in carbohydrates and therefore in NaB, can disrupt the balance among proteins regulating cell cycle progression and, possibly, contribute to malignancy.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported in part by a grant from the Italian Association for Cancer Research and Italian Health Ministry. We thank B. Johnston for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Archer SY et al. (1998). p21waf1 is required for butyrate‐mediated growth inhibition of human colon cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 95,6791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs JR, Kudlow JE, Kraft AS (1996). The role of transcriptional factor Sp1 in regulating the expression of the WAF1/CIP1 gene in U937 leukemic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271,901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffa LC et al. (1978). Suppression of histone deacetylation in vivo and in vitro by sodium butyrate. J. Biol. Chem. 253,3364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisteau O et al. (1996). Induction of apoptosis in vivo and in vitro on colonic tumor cells of the rat after sodium butyrate treatment. Bull. Cancer 83,197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway RM et al. (1995). Induction of apoptosis by sodium butyrate in the human Y79 retinoblastoma cell line. Oncol. Res. 7,289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coradini D et al. (1997). Effect of sodium butyrate on human breast cancer cell lines. Cell Prolif. 30,149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datto MB et al. (1995). Transforming growth factor beta induces the cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53‐independent mechanism. Proceedings Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 92,5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El‐Deiry WS et al. (1993). WAF1 a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75,817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doglioni C et al. (1996). P21/WAF1/CIP1 expression in normal mucosa and in adenomas and adenocarcinomas of the colon. its relationship with differentiation. J. Pathol. 179,248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon ER, Vogelstein BA (1990). A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell 61,759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryfe R et al. (1997). Molecular biology of colorectal cancer. Cancer 21,233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilbaud NF et al. (1990). Effect of differentiation‐inducing agents on maturation of human MCF7 breast cancer cell. J. Cell Physiol. 145,162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel PA, Hanley‐Hyde J (1997). G1 cyclins and control of the cell division cycle in normal and transformed cells. Cancer Invest. 15,143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerdt BG, Houston MA, Augenlicht LH (1997). Short‐chain fatty acid‐initiated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of colonic epithelial cells is linked to mitochondrial function. Cell Growth Differentiation 8,523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MJ (1995). Bacterial fermentation of complex carbohydrates in the human colon. Eur. J. Cancer Prevention 4,353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs LR (1987). Effect of dietary fiber on colonic cell proliferation and its relationship to colon carcinogenesis. Prev. Med. 16,566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JansonW, Brandner G, Siegel J (1997). Butyrate modulates DNA‐damage‐induced p53 response by induction of p53‐independent differentiation and apoptosis. Oncogene 15,1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joensuu T, Mester J (1994). Inhibition of cell cycle progression by sodium butyrate in normal rat kidney fibroblasts is altered by expression of the adenovirus 5 early 1A gene. Biosci. Report 14,291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupitza G et al. (1996). Genes related to growth and invasiveness are repressed by sodium butyrate in ovarian carcinoma cells. Br. J. Cancer.73,433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y et al. (1994). Cell cycle expression and p53 regulation of the cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor p21. Oncogene 9,2261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvak DA et al. (1998). Butyrate‐induced differentiation of Caco‐2 cells is associated with apoptosis and early induction of p21 waf1/cip1 and p27 kip1. Surgery 124,161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcintyre A, Gibson PR, Young GP (1993). Butyrate production from dietary fibre and protection against large bowel cancer in a rat model. Gut 34,386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer DG, Paraskeva C, Williams AC (1997). Modulation of p53 expression in cultured colonic adenoma cell lines by naturally occurring lumenal factors butyrate and deoxycholate. Int. J. Cancer 73,702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL et al. (1996). Cancer Statistics. Cancer J. Clin. 46,5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JD (1996). Nutrition and colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control.7,127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad KN (1980). Butyric acid: a small fatty acid with diverse biological functions. Life Sci. 27,1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rephaeli A et al. (1994). Butyrate‐induced differentiation in leukemic myeloid cells. in vitro and in vivo studies. Int. J. Oncol. 4,1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S et al. (1991). Flow cytometric and biochemical analysis of dose‐dependent effects of sodium butyrate on human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. Cytometry 12,757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M, Hannon GJ, Beach D (1993). A new regulatory motif in cell cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/cdk4. Nature 366,704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao RG et al. (1997). Abrogation of an S‐phase checkpoint and potentiation of camptothecin cytotoxicity by 7‐hydroxystaurosporine (UCN‐01) in human cancer cell lines possibly influenced by p53 function. Cancer Res. 57,4029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JG, Yokoyama WH, German JB (1998)Butyric acid from the diet: actions at the level of gene expression. Crit Rev. Food Sci. Nutr 38,259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souleimani A, Asselin C (1993). Regulation of c‐myc expression by sodium butyrate in the colon carcinoma cell line Caco‐2. FEBS Lett. 326,45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Parsons PG (1990). In vitro phenotype alteration of human melanoma cells induced by differentiating agents: heterogeneous effects on cellular growth and morphology, enzymatic activity and antigenic expression. Pigment Cell Res. 3,223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twentyman PR, Luscombe M (1987). A study of some variables in a tetrazolium dye (MTT) based assay for cell growth and chemosensitivity. Br. J. Cancer 56,279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri C, Stice L, Faller DV (1998). Butyrate‐induced G1 arrest results from p21‐independent disruption of retinoblstoma protein‐mediated signals. Cell Growth Differentiation 9,465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XM et al. (1998). Effects of 5‐azacytidine and butyrate on differentiation and apoptosis of hepatic cancer cell lines. Ann. Surg. 227,922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley LO et al. (1996). Evaluation in rats of the dose‐response relationship among colonic mucosal growth, colonic fermentation and dietary fiber. Dig. Dis. Sci. 41,1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]