Abstract

CONTEXT:

Evidence confirms associations between childhood violence and major causes of mortality in adulthood. A synthesis of data on past-year prevalence of violence against children will help advance the United Nations’ call to end all violence against children.

OBJECTIVES:

Investigators systematically reviewed population-based surveys on the prevalence of past-year violence against children and synthesized the best available evidence to generate minimum regional and global estimates.

DATA SOURCES:

We searched Medline, PubMed, Global Health, NBASE, CINAHL, and the World Wide Web for reports of representative surveys estimating prevalences of violence against children.

STUDY SELECTION:

Two investigators independently assessed surveys against inclusion criteria and rated those included on indicators of quality.

DATA EXTRACTION:

Investigators extracted data on past-year prevalences of violent victimization by country, age group, and type (physical, sexual, emotional, or multiple types). We used a triangulation approach which synthesized data to generate minimum regional prevalences, derived from population-weighted averages of the country-specific prevalences.

RESULTS:

Thirty-eight reports provided quality data for 96 countries on past-year prevalences of violence against children. Base case estimates showed a minimum of 50% or more of children in Asia, Africa, and Northern America experienced past-year violence, and that globally over half of all children—1 billion children, ages 2–17 years—experienced such violence.

LIMITATIONS:

Due to variations in timing and types of violence reported, triangulation could only be used to generate minimum prevalence estimates.

CONCLUSIONS:

Expanded population-based surveillance of violence against children is essential to target prevention and drive the urgent investment in action endorsed in the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda.

Violence against children is a public health, human rights, and social problem, with potentially devastating and costly consequences.1 Its destructive effects harm children in every country, impacting families, communities, and nations, and reaching across generations. Recognizing its pervasive and unjust nature, almost all nations (196) ratified the 1989 United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child, which recognizes freedom from violence as a fundamental human right of children. Now, over 25 years later, the UN has launched a new Agenda for Sustainable Development to end all forms of violence against children.2 Documenting the magnitude of violence against children by synthesizing the best available evidence will be essential for informing policy, driving action, and monitoring progress for this bold agenda.

Data from surveys on violence against children in different countries typically measure prevalences of individual types of violence, such as physical, sexual, or emotional violence. Alternatively, estimates may focus on 1 location or class of perpetrator; examples include bullying victimization, which is often only measured when it occurs on school grounds, or child maltreatment, which is limited to that perpetrated by parents or caregivers. Rarely do prevalence studies measure ranges of types, locations, and perpetrators.

Although few studies assess experiences of childhood violence across types, many reports suggest differing types share similar consequences.3 Such consequences are additive, increasing with increases in types and severity of violence experience.3,4 These harmful sequelae span major causes of death in adulthood, including noncommunicable diseases, injury, HIV, mental health problems, suicide, and reproductive health problems.3–6

Empirical associations between early exposure to violence and major causes of mortality in adulthood were recognized years ago, before elucidation of their shared biological underpinnings.3,4,7 Recent evidence documents the biology of violence, demonstrating that traumatic stress experienced in response to violence may impair brain architecture, immune status, metabolic systems, and inflammatory responses.4 Early experiences of violence may confer lasting damage at the basic levels of nervous, endocrine, and immune systems, and can even influence genetic alteration of DNA.4,7

In response to increasing recognition of the magnitude, consequences, biology, and costs of violence against children, there are growing commitments by UN agencies, the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USAID, PEPFAR, World Bank, Together for Girls, governments, academic centers, and civil society organizations, to its prevention. The converging prioritization of protecting children from violence has culminated in the inclusion of not just 1, but 2 zero- based targets—outcomes that every country should seek to eliminate, rather than merely reduce—in the sustainable development goals (SDGs): to “end abuse, exploitation, trafficking, and all forms of violence against children,” and to “eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls.”2 Many countries lack the data that will be needed to evaluate progress from 2016 to 2030 toward these targets.

After years of research addressing magnitude, risk factors, and consequences of violence against children, a consensus is emerging on how to reliably measure its prevalence. Because violence against children does not typically come to the attention of official agencies, global evidence reveals that the self-reported prevalence of child sexual abuse victimization is >30 times higher than official reports,8 and selfreported physical abuse victimization is >75 times higher.9 Thus, self-reports are now considered an essential measurement tool and will be foundational for informing new investment opportunities associated with the SDG aims to end violence against children. These self-reports should be ascertained after informed assent/consent is given and in private, where children and/or caretakers can provide direct information about exposures to violent behaviors across types, locations, and perpetrators.

In recent years, the number of representative surveys addressing prevalences of recent experiences of violence against children has increased. Two of these, the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV) and Violence Against Children Surveys (VACS), measure the full range of types, locations, and perpetrators; and several others, such as Multiple Indicator Surveys (MICS), WorldSafe, Health Behavior in School-Aged Children Surveys (HBSC), and Global School Health Surveys (GSHS), provide estimates of exposures to several types of violence, though these estimates are restricted to 1 class of perpetrator or location.10–15

Given the new global prioritization of the prevention of violence against children, it is important to use the best available evidence to assess the extent to which children in various regions of the world are exposed to it. Our aims are to systematically review the quality of population-based evidence on prevalence of violence against children during the past year, and then to use a triangulation approach that synthesizes data from high quality surveys to estimate global minimum prevalences and numbers of children exposed to violence during the past year. We conclude by describing the urgent need to implement effective,multisector programs and policies to prevent violence against children.

METHODS

Systematic Review: Approach, Characteristics, Quality, and Data Abstraction

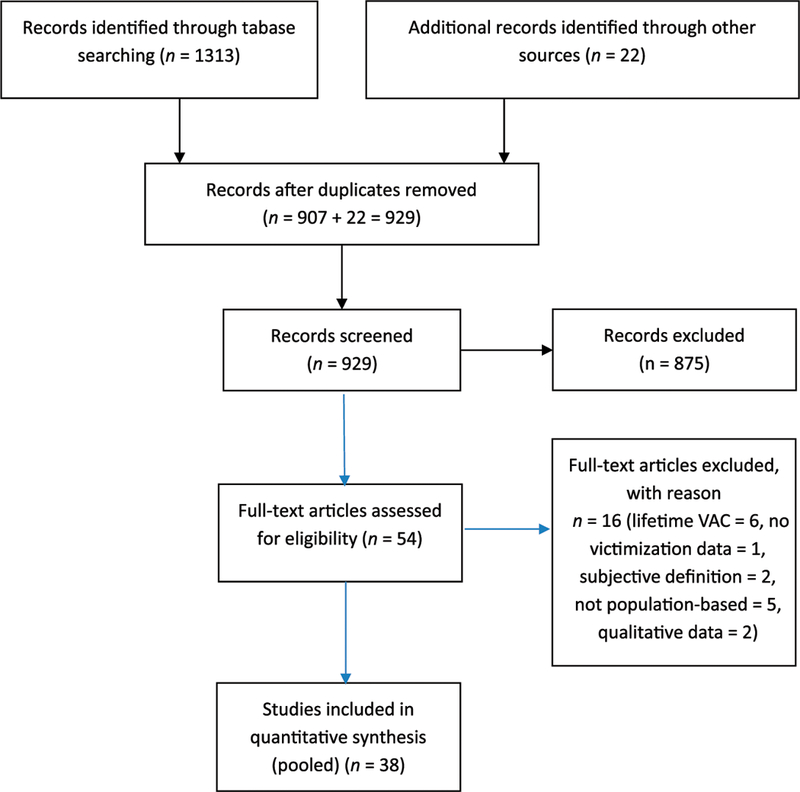

We used the PRISMA statement to guide our systematic review.16 Our database search, conducted in January 2014 by using Medline, PubMed, Global Health, NBASE, and CINAHL, identified 907 unduplicated peer-reviewed reports published after the year 2000, by using these search terms: [(low-income countries or middle-income countries or high-income countries or developing countries or developed countries) and (ages 1 to 18 years or children or adolescents or infants or preschool child or school child) and (national surveys or population surveillance or health survey or surveys or disease surveys or epidemiologic surveys or surveillance), and (child maltreatment or physical violence or sexual violence or emotional violence or maltreatment or neglect or bully or bullying or bullies or bullied)] (see Supplemental Material). We extended our search from January 2014 to August 2015 (see Supplemental Material) and identified an additional 22 published reports (Supplemental Material), including both peer- reviewed papers and reports from the UNICEF MICS (reports from 33 countries), VACS (reports for 8 countries), and HBSC (reports for 37 countries). After screening a total of 929 unduplicated reports for descriptions of population-based measures of any type of past-year violence against children in the 0 to 17 year age range, we conducted a full review on 54 reports. Of these, 16 reports were excluded due to: no report of past-year prevalence,6 report of perpetration only,1 subjective definition of exposure,2 nonprobabilistic sampling,5 and provision of only qualitative data2 (Fig 1). The final 38 reports provided quantitative estimates of prevalence of 1 or more types of violence against children occurring during the previous year.17,10–15,18–48

FIGURE 1:

Systematic review flow diagram: prevalence of violence against children.

These 38 references met the following criteria for inclusion: (1) population-based survey data, probabilistically drawn, using national or subnational samples; (2) use of standard measures of violence that assess behaviors (Supplemental Table 6, Supplemental Material); (3) data collected by interviewer-administered household survey, school survey, or random digit dialed telephone survey using self-report (by child and/or caregiver); (4) age of target population (2–17 years); (5) specification of country-specific or area-specific estimates; and (6) violence reported during 1 to 12 months before implementation of the survey. To conduct the systematic review, 2 investigators (S.H. and H.K.) independently assessed studies against inclusion criteria and independently rated their quality for key indicators, including clear description of population-based sampling, use of standard definitions of violent behaviors, preimplementation training of interviewers/questionnaire administrators, presentation of weighted analyses, description of whether survey was national or subnational, and participation rates (Table 1). Finally, the investigators (S.H. and H.K.) performed duplicate extraction of past-year prevalence data by age,2–16,18 country, and type of violent victimization as defined by varying investigators, including physical violence, moderate physical violence, severe physical violence, emotional violence, severe psychological (emotional) violence, sexual violence, bullying, and physical dating violence (Supplemental Table 6, Supplemental Material). Although our interest was experience of any violence, which included 1 or more types of victimization (physical, sexual, or emotional) committed by a range of perpetrators (authority figures, peers, romantic partners, or strangers) in various locations (home, school, or community), only VACS and NatSCEV provided such measures 10,11,19,26–30,38,40,41,44,47

TABLE 1.

Population-Based Surveys Measuring Past-year Violence Against Children: Characteristics and Survey Quality Indicators

| Characteristics | Quality | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group for Review, Y |

Survey Type (Ref. No.) |

No. of Countries |

Countries | Standard Definition |

Training | Probabilistic Sampling |

Weighted Analyses |

Coverage | Participation | ||

| NAT | REG | MUN | |||||||||

| 2–14 | MICS (12, 24, 45) | 33 | Albania, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belize, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Iraq, Ivory Coast, Jamaica, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Kazakhstan, Kyrgystan, Kenya, Montenegro, Macedonia, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Suriname, Syria, Tajikistan, Togo, Trinidad & Tobago, Vietnam, Ukraine, Yemen | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | Not Reported | ||

| WorldSafe (13) | 6 | Brazil, Egypt, India, United States, Chile, Philippines | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 33%—99% | ||

| NatSCEV (11, 38, 40, 41, 47) |

1 | United States | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Variable across samples, 14%—67% |

|||

| CTS (35, 37, 39, | 3 | Canada, Italy, Finland | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 50%—57% | |||

| 43) | |||||||||||

| 15–17 | VACS (10, 18, 25–30, 31, 44) | 8 | Swaziland, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Tanzania, Haiti, Malawi, Nigeria, Cambodia | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 88%—98% | ||

| GSHS (15, 17, 19, 20, 22, 23) |

21 | Botswana, Brazil, Chile, China, Egypt, Guyana,Jordan, Lebanon, Kenya, Morocco, Namibia, Oman, Philippines, Swaziland, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela, Zambia, Zimbabwe | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 84% | |||

| HBSC (14, 21, | 37 | Armenia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Croatia, Czech | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 60% | |||

| 32, 42) | Republic, Estonia, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Greenland, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Macedonia, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Scotland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, United States, Wales |

||||||||||

| National Survey | 1 | Brazil | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 83% | |||

| of School | |||||||||||

| Health | |||||||||||

| (PeNSE) (48) | |||||||||||

| YRBS, Physical | 1 | United States | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 67% | |||

| dating | |||||||||||

| violence (36, | |||||||||||

| 46) | |||||||||||

| Bullying (17, 33, | 3 | New Zealand, Pakistan, Australia | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 45%—7 0% | |||

| 34) | |||||||||||

MUN, municipal; NAT, national; REG, regional.

The MICS, however, do report “any violent discipline” as the perpetration in the home by caregivers of any of these categories of violent discipline: moderate physical and/or severe physical and/or psychological violence. For this article, we include MICS reports of “any violent discipline” in our “any violence” category.25

Synthesizing Estimates of Minimum Exposure to Past-year Violence

The final review included data from 112 studies in 96 countries. We used a triangulation approach, which included a critical synthesis of data to develop minimum estimates by using population-weighted averages of regional exposures to past-year violence.49–51 Triangulation is appropriate for comparing, contrasting, and synthesizing research characterized by varying methodologies and diverse limitation when the primary purpose is not to elucidate etiology, but rather to catalyze public health action.49 Although previous reports have pooled data on a specific type of violence from a standardized survey (eg, GSHS), our interest in generating estimates of past-year experience of any type of violence across surveys made triangulation more suitable, due to variations in methods, definitions, populations, and timing of data collection.15,49,52 Using types of violence measured in various surveys, such as NatSCEV, MICS, WorldSafe, VACS, GSHS, and HBSC (Table 1), we abstracted past-year prevalences of physical violence, severe physical violence, sexual violence, emotional violence, severe psychological (emotional) violence, bullying victimization, fighting, and when reported, exposure to “any violence.” Forty-three countries reported exposure to “any violence” in the past year. MICS studies33 and the Canada Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) adaptation1 report moderate physical and/or harsh physical and/ or emotional by 1 type of perpetrator in 1 type of location; VACS studies8 report physical, emotional, and/or sexual by multiple perpetrators and locations; NatSCEV1 reports physical and/or emotional, and/or sexual and/or bullying and/or direct crime against the child, and/or witnessing violence by multiple perpetrators and locations.10–12,19,25–30,38,40,41,44,47 Though NatSCEV includes both victimization and witnessing violence, we include only direct victimization data. In instances where the same survey had been implemented periodically (eg, NatSCEV, HBSC), we used the most recently published.14,47

Definitions vary on the measurement of exposure to any given type of violent victimization. Definitions vary particularly in whether they include hitting with bare hands, or spanking, as a form of violence. For example, in the WorldSafe, MICS, and survey adaptations using CTS, “moderate physical violence” includes “slapping, hitting with bare hands, hitting with an object, shaking, or spanking”13,25,29,35,43; in contrast, the NatSCEV and VACS exclude spanking from their measures.10,47 In light of these variations, we performed our base case analysis by using the conservative definition for physical violence which excluded spanking, although in so doing we also excluded other dimensions in the moderate category for violent discipline, such as slapping and shaking. Thus, for survey measures based on the experiences of violence in the home (MICS, WorldSafe, and survey adaptations of CTS), we used prevalences for severe violence (such as kicked, choked, smothered, burned, scaled, branded, beat repeatedly, or hit with an object) in the base case analyses to avoid inclusion of spanking13,25,35,39,43 (Supplemental Table 6, Supplemental Material). For the sensitivity analysis, we expanded the classification of exposures to include prevalences of moderate physical violence or any violence, both of which had spanking as a defining indicator (Supplemental Material).13,25 As expected, country-specific prevalences of violence against children in the base case were lower than those in the sensitivity analysis.

Country-specific Estimates of Violence Against Children

We used published prevalence data to generate country-specific estimates for 2 age groups (2–14 and 15–17 years) of minimum prevalences of violence in the previous 12 months. Age ranges and types of violence reported varied across surveys, with most reporting only 1 or 2 types; additionally, many surveys only measured past-month exposure. Therefore, due to limitations in types and timing, we can only characterize prevalence of past-year violence in terms of minimum exposure for children living in 1 of the countries with published data. We also excluded children aged 0–1 years, since few reports include this group.

To estimate the minimum number of children aged 2 to 17 years exposed to violence in each country, we used 2014 US Census Bureau international population data to create 2 population-at-risk age groups: 2 to 14 and 15 to 17 years53 (Supplemental Material). Then, for both base case and sensitivity analyses, to estimate numbers of children in a given country known to be exposed, we applied the highest published age group-specific prevalence of violence (often only 1 type for the base case) to the corresponding 2014 reference population age group for that country: either the 2- to 14-year-old or the 15- to 17-year-old population. Disaggregated age data were available for 110 of 112 abstracted prevalence estimates, either through age-related eligibility criteria for a given survey or through age-stratified data for surveys including ages 0 to 17 years (see Supplemental Material for details). While reports measuring violent discipline (eg, MICS) provided most country-specific estimates for ages 2 to 14 years, those surveys focusing on adolescents, such as VACS, GSHS, and HBSC provided most data for the 15- to 17-year-old population.10,14,15,25 For a given country, prevalence estimates may have included only 2- to 14-year-olds, only 15- to 17-year- olds, or both (Supplemental Table 7, Supplemental Material).

Regional Estimates of Minimum Prevalences and Projected Numbers of Children Exposed to Past-year Violence

For each region, we derived estimates of the minimum prevalence of children exposed to past-year violence from the population-weighted average of the country-specific prevalences, and then applied the known prevalences to the entire region. The 96 countries with population-based data included 24 in Africa, 20 in Asia, 9 in Latin/ South America, 3 in Northern America, 38 in Europe, and 2 in Oceania. We computed estimates separately for 2- to 14-year-old and 15-to 17-year-old populations, by using 2014 Census data53 to provide minimum prevalences of childhood violence by age (Table 2 and Supplemental Material). Next, we used the estimates of regional prevalences from abstracted data to develop projected total minimum numbers of children exposed to violence in the corresponding region by age group. We then used the sum of the minimum regional numbers of children ages 2 to 14 years and 15 to 17 years experiencing violence and the sum of corresponding regional 2014 populations to estimate regional and global minimum prevalences and numbers of children ages 2 to 17 years experiencing past-year violence. Finally, we used a similar population-weighted approach to estimate minimum prevalences of past-year violence against children based on the UN classification of developed and developing nations. The use of triangulation to critically synthesize data on past-year violent victimization across surveys allowed us to combine data for children living in nearly half the countries in the world; ~42% of the world’s children reside in these countries.

TABLE 2.

Base Case Estimates of Past-year Violence Against Children by Age Group and Region

| Ages 2–14 y | Ages 15–17 y | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Pooled From Published Reports | Total Population at Risk | Pooled From Published Reports | Total Population at Risk | ||||||

| Total N for Included Reports, Census Data |

Minimum n Affected by VAC From Reports |

Minimum % With Past-year VAC |

Total N From Census Data |

Minimum n Imputed Affected by VAC |

Total N for Included Reports, Census Data |

Minimum n Affected by VAC From Reports |

Minimum % With Past year VAC |

Total N From Census Data | Minimum n Imputed Affected by VAC |

|

| a | b | c = b/a | d | e = (b/a) × (d) | f | g | h = g/f | j − (g/f) × (i) | ||

| Africa | 71 876 435 | 35958876 | 50 | 385921 657 | 193071 746 | 30 848 759 | 15723230 | 51 | 71 989 161 | 36 691 983 |

| Asia | 393 844643 | 266954747 | 68 | 903 793 328 | 612606 832 | 143 742 417 | 68 854329 | 48 | 212833 830 | 101 949 939 |

| Latin America | 53738988 | 18 429 032 | 34 | 138 468115 | 47 485 696 | 13477938 | 4482313 | 33 | 32906540 | 10943618 |

| Europe | 16686939 | 1 359 251 | 8 | 100964471 | 8 224160 | 21 542 125 | 6590651 | 31 | 22 775 007 | 6967841 |

| Northern | 57837970 | 32 175318 | 56 | 57860154 | 32 187 659 | 13696533 | 8 005 173 | 58 | 13699 268 | 8 006 772 |

| America | ||||||||||

| Oceania | Not available | 7090890 | Not available | 1010283 | 399 949 | 40 | 1617154 | 640197 | ||

Minimum prevalences and projected minimum estimates of total numbers of children affected. Excludes children exposed to moderate physical violence, which is defined as spanked, slapped in the face, hit, or shook.

RESULTS

Quality of Surveys

The majority of surveys in our review were high quality (Table 1). We confirmed 100% (112/112) of reports used probabilistic sampling, and 100% used standard definitions of exposures to violent behaviors. In addition, 96% (108/112) described training of interviewers/ questionnaire administrators, 93% (104/112) reported weighting findings, 100% reported whether their surveys were national (102) or subnational (10), and 70% (78/112) reported participation rates (39%−99% range). Although nearly half of the countries in the world have published population-based data on at least 1 type of violence, this also means that half of the countries in the world do not have such data.

Synthesized Estimates

For the base case analysis of minimum prevalences of past-year violence among 2- to 14-year olds and 15- to 17-year-olds, we found that synthesized estimates for both age groups approached or exceeded 50% for Africa, Asia, and Northern America, and exceeded 30% for Latin America (Table 2). For Europe, prevalences of the more severe types of violence included in the base case scenario tended to be lower than for other regions. We largely computed these base case minimum estimates for 2- to 14-year-olds by using country-specific highest reported prevalence for 1 type of violence (eg, severe physical violence by caregivers for most countries), because most surveys reporting exposures to any violence for this age included spanking in their definitions. In contrast, the sensitivity analyses did include prevalence measures of any violence; synthesis of results for 2- to 14-year-olds showed minimum prevalences of past-year violence exceeded 60% in Northern America, 60% in Latin America, 70% in Europe, 80% in Asia, and 80% in Africa (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity Analysis Estimates of Past-year Violence Against Children by Age Group and Region

| Ages 2–14 y | Ages 15–17 y | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled From Published Reports | Total Population at Risk | Pooled From Published Reports | Total Population at Risk | |||||||

| Total N From Census Data |

Pooled n Affected by VAC From Reports |

Past-year VAC, % |

Total N From Census Data |

n Imputed Affected by VAC |

Total N From Census Data |

Pooled n Affected by VAC From Reports |

Past-year VAC, % |

Total N From Census Data |

n Imputed Affected by VAC |

|

| Region | a | b | C = b/a | d | e – (b/a) × (d) |

f | g | h – g/f | i | j – (g/f) × (i) |

| Africa | 71876435 | 62759153 | 87 | 385921657 | 336968802 | 30848759 | 15723230 | 51 | 71989161 | 36691983 |

| Asia | 393844643 | 340657383 | 86 | 903793328 | 781739387 | 143742417 | 71644993 | 50 | 212833830 | 106081967 |

| Latin | 53738988 | 34340020 | 64 | 138468115 | 88483205 | 13477938 | 4482313 | 33 | 32906540 | 10943618 |

| America | ||||||||||

| Europe | 16686939 | 12184304 | 73 | 100964471 | 73721241 | 21542125 | 6527774 | 30 | 22775007 | 6901367 |

| Northern | 57837970 | 35685684 | 62 | 57860154 | 35699372 | 13630826 | 8005173 | 58 | 13699268 | 8006772 |

| America | ||||||||||

| Oceania | Not available | 7090890 | Not available | 1010283 | 40 | 1617154 | ||||

Minimum prevalences and minimum estimates of total numbers of children affected. Includes children exposed to moderate physical violence, defined as spanked, slapped in the face, hit, or shook.

For the base case, our estimates for the entire group of 2- to 17-year-olds indicated that a minimum of 64% of these children in Asia, 56% in Northern America, 50% in Africa, 34% in Latin America, and 12% in Europe experienced past-year violence (Table 4). The low estimate for Oceania is linked to the fact that representative surveys measuring prevalences of violence were only available for ages 15 to 17 years and thus, we assumed none of the 2- to 14-year-olds experienced violence. An estimation of the total minimum numbers of children exposed, which is a function of both prevalence and size of the population-at-risk in 2014, shows Asia has the highest number, with over 700 million children exposed; Africa follows with over 200 million children; then Latin America, Northern America, and Europe combined show over 100 million children exposed. The synthesized findings for the base case scenario indicate that, globally, a minimum of over 1 billion children were exposed to violence during 2014 (Table 4). For the sensitivity analysis, we found that a minimum of over 1.4 billion of the nearly 2 billion children aged 2 to 17 years experienced physical, emotional, and/or sexual violence in the previous year (Table 4). Though prevalences of violence were high in both the developing and developed world, the minimum number estimated as suffering victimization in the developing world in 2014 exceeded 1 billion children (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Regional and Global Projections of Minimum Prevalences of Past-year Violence, and Minimum Numbers of Children Exposed to Past-year Violence

| Region | Base Case | Sensitivity Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children-at-Risk: Census Population Ages 2–17 y |

Past-year Estimate of Any Violence or Severe Violence, % |

Projected No. of Children Ages 2–17 y Exposed to Any Violence or Severe Violence |

Past-year Estimate of Any Violence, Moderate Violence, or Severe Violence, %a |

Projected No. of Children Ages 2–17 y Exposed to Any Violence, Moderate Violence, or Severe Violencea |

|

| Africa | 457910818 | 50 | 229763729 | 82 | 373660785 |

| Asia | 1116627158 | 64 | 714556771 | 80 | 887821353 |

| Latin | 171374655 | 34 | 58429315 | 58 | 99426824 |

| America | |||||

| Europe | 123739478 | 12 | 15192001 | 65 | 80622608 |

| Northern | 71559422 | 56 | 40194431 | 61 | 43706144 |

| America | |||||

| Oceania | 8708044 | 7 | 640197 | 7 | 640197 |

| World | 1949919575 | 54 | 1058776444 | 76 | 1485877910 |

“Any violence” includes, depending on survey type, exposure to 1 or more of the following: physical violence, emotional violence, sexual violence, bullying, or witnessing violence.

Includes children exposed to moderate physical violence, which is defined as spanked, slapped in the face, hit, or shook.

TABLE 5.

Global Projections of Minimum Prevalences of Past-year Violence and Minimum Numbers of Children Exposed to Past-year Violence by UN Economic Groupings

| Region | Base Case | Sensitivity Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children-at-Risk: Census Population Ages 2–17 y |

Past-year Estimate of Any Violence or Severe Violence, % |

Projected No. of Children Ages 2–−17 y Exposed to Any Violence or Severe Violence |

Past-year Estimate of Any Violence or Moderate Violence or Severe Violence, %a |

Projected No. of Children Ages 2–17 y Exposed to Any Violence or Moderate Violence or Severe Violencea |

|

| Developing Countries |

1730914508 | 59 | 1025119 052 | 78 | 1347185177 |

| Developed Countries |

219005067 | 44 | 97052628 | 60 | 131184841 |

“Any violence” includes, depending on the survey type, exposure to 1 or more of the following: physical violence, emotional violence, sexual violence, bullying, or witnessing violence. Based on UN developing countries, including least developed countries in: Africa, Asia excluding Japan, the Caribbean, Central America, South America, and Oceania excluding Australia and New Zealand; and developed countries in: Northern America, Europe, Japan, Australia, New Zealand.

Includes children exposed to moderate physical violence, which is defined as spanked, slapped in the face, hit, or shook.

DISCUSSION

Our systematic review of studies used to derive minimum estimates of pastyear violence against children showed these population-based surveys were high quality.16 Most surveys had the following characteristics: probabilistic sampling, standard definitions, training of interviewers/questionnaire administrators, weighting of estimates for complex designs, and national scope. If we assume our base-case scenario combining prevalences across approximately half of the countries are representative of overall minimum prevalence estimates for all countries, and thus can be projected to the entire population, then the number of children exposed to violence in the past year exceeds 1 billion, or half the children in the world. Region-specific estimates for children aged 2 to 17 years indicate that the Asian, African, and Northern American regions had the highest minimum prevalences. Because of the sheer size of the Asian population, the minimum estimate of numbers of children experiencing past-year violence there was ∼2 times greater than in the other regions combined. Even more sobering were findings from the sensitivity analyses, which included moderate physical violence and showed three-fourths of the world’s children experienced violence in the previous year. Whether from the base case or from the sensitivity analysis, our findings compel urgent action.

Prevalences of country-specific types of violence against children, such as that described in UNICEF’s Hidden in Plain Sight, also demonstrate an urgent need to escalate global commitments to protecting children.45 In our report, we critically synthesized population-based measures of violence against children aged 2 to 17 years that are recent (past-year) and more serious to provide minimum regional and global estimates of the public health burden of violence against children. Our interest for the base scenario in more serious types of violence is linked to their potential to influence a range of public health consequences and to be associated with the kind of toxic stress that damages brain architecture in children.3,4,54 Thus, given our findings, we estimate that violence may threaten the optimum development of over a billion brains in children, every year. Though we excluded moderate forms of violence, such as hitting a child on the buttocks or extremities in the base analysis, we included these forms in the sensitivity analysis, as evidence suggests spanking is considered a form of violence, violates rights to protection, can be harmful to development, and is linked with externalizing and internalizing behavior problems.55–63 Given that the new SDG agenda proposes ending all forms of violence against children, our synthesized estimates help convey the scale of this urgent global problem.

The overarching purpose of population-based surveys on violence against children is to drive national action plans that catalyze change.1 Several surveys, including HBSC and NatSCEV, have been implemented repeatedly to monitor trends. An evaluation of trends in bullying from 2002–2010 by using HBSC, for example, shows no change in most of the 33 countries, although reductions were observed in one-third of countries.14 Similarly, over 3 waves of NatSCEV in the United States, from 2008–2014, there was no overall reduction in past-year violent victimization of children.47

We considered limitations that may have biased our estimates of past-year violence against children. The strongest limitation is that our estimates underreport prevalences for several reasons. First, since few surveys include the range of types, perpetrators, and locations of violence, base-case estimates were often computed on only 1 type of violence; for example, violent discipline in the home was the predominate type reported for 2- to 14-year-olds, and either bullying, fighting, or multiple exposures (from VACS) for 15- to 17-year- olds. However, for the sensitivity analyses, nearly half (n = 43) of the countries had data on exposure to multiple types of violence. We further underestimated prevalences by assuming none of the children ages 2 to 14 years in Oceania were exposed, because no data were available for this age group. We also assumed, due to lack of data, that no children under 2 years were exposed. It is also possible that selection bias may have influenced our imputed regional estimates, if minimum prevalences of violence differ between those countries with and those without published estimates, or if in the several cases with only subnational estimates, those differ from national ones. There may also be differential bias between regions given variations in age distributions, types of violence reported, and proportion of the populations living in countries without estimates. Finally, we believe it is unlikely that our findings were meaningfully biased by our assumption that prevalences of violence were stable during the time period between their publication and 2014, the year of estimation of the population-at-risk. For over 90% of our estimates, this lag-time was 1 to 5 years. A recent report demonstrates trends in child maltreatment in 6 countries remained unchanged from the mid- 1970s through 201064; thus, it may be reasonable to assume violence rates were relatively constant over time.

Just as global recognition of the endemic magnitude of violence against children has sped forward over the past decade, the multisector evidence demonstrating that such violence is largely preventable has advanced.1,65,66 The state of evidence demonstrates interventions to address violence against children should cross strata of the socioecologic model, including the child, family, community, and society.1,67 For optimum impact, such policies and programs will be multisector, spanning health, social services, education, and justice sectors.1 In the United States, for example, although NatSCEV shows no overall reductions in recent trends in direct victimization of children, administrative data from child protection agencies shows a 40% decline in substantiated child sexual abuse from 1990 to 2000; this decline may be linked to the interplay of programs and policies implemented across sectors.68 The integration of multisector approaches with ones that are also multi-stakeholder should accelerate progress, engaging governments, business, nongovernmental, and civil society organizations in the shared goal of caring for the world’s children.

The World Health Organization, in collaboration with UNICEF, UNODC, PEPFAR, USAID, World Bank, US Department of State, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Together for Girls, is leading the development of a unified package of these 7 evidence-based strategies to prevent violence against children: teaching positive parenting skills, helping children develop socialemotional skills and stay in school, raising access to health, protection, and support services, implementing and enforcing laws that protect all children, valuing social norms that protect children, empowering families economically, and sustaining safe environments for children. These strategies are in large part built as an adaptation of the CDC THRIVES core package and similar guidance from WHO, UNICEF, PEPFAR, and USAID65–67,69–90

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings using population-based data from approximately half of the countries in the world show that over 1 billion children ages 2 to 17 years have experienced violence in the past year. These data demonstrate an urgent need for wider adoption, scaling, and sustaining of evidence-based interventions to reduce this high burden of violence against children.89 Improved surveillance of the range of types, locations, and perpetrators of violence against children, as well as of access to key prevention interventions, is essential to target prevention, monitor progress, and drive the urgent action endorsed in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda.2 The time is ripe for the newly-established Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children to catalyze multi-stakeholder investments in expansive solutions for a billion children.2,91–93

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: No external funding.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CTS

Conflict Tactics Scale

- GSHS

Global School Health Surveys

- HBSC

Health Behavior in School-Aged Children Surveys

- MICS

Multiple Indicator Surveys

- NatSCEV

National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence

- SDG

sustainable development goals

- UN

United Nations

- VACS

Violence Against Children Surveys

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Drs Hillis and Mercy conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and are accountable for representing all aspects of the work; Drs Hillis and Kress conducted the systematic review, abstracted relevant data, analyzed and/or interpreted the synthesized data, revised and approved the final manuscript, and are accountable for representing all aspects of the work; and Dr Amobi contributed to acquiring, synthesizing, and interpreting the data, drafting, reviewing, and revising the manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and is accountable for representing all aspects of the work.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization, United Nations. Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014 Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations General Assembly; Seventieth Session. September 18, 2015; New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felitti VJR, Anda R, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med 1998:14(4):245–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anda RF, Butchart A, Felitti VJ, Brown DW. Building a framework for global surveillance of the public health implications of adverse childhood experiences. Am J Prev Med 2010;39(1):93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norton R, Kobusingye 0 Injuries. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1723–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women: a retrospective study. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/106/1/e11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age- related disease. Physiol Behav 2012;106(1):29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat 2011;16(2):79–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans- Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, Alink LRA. Cultural-geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. Int J Psychol 2013;48(2):81–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare, Republic of Malawi. Report: Violence Against Children and Young Women in Malawi: Findings From a National Survey 2013 Lilongwe, Malawi: Republic of Malawi; 2014. Available at: www.unicef.org/malawi/MLW_resources_violencereport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, Hamby SL. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1411–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akmatov MK. Child abuse in 28 developing and transitional countries-results from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(1):219–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Runyan DK, Shankar V, Hassan F, et al. International variations in harsh child discipline. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/126/3/e701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chester KL, Callaghan M, Cosma A, et al. Cross-national time trends in bullying victimization in 33 countries among children aged 11, 13 and 15 from 2002 to 2010. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(suppl 2):61–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown DW, Riley L, Butchart A, Meddings DR, Kann L, Harvey AP Exposure to physical and sexual violence and adverse health behaviors in African children: results from the Global School-based Student Health Survey. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(6):447–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations Children’s Fund Swaziland Country Office. 2012. Swaziland’s Response to Violence Against Children. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/vacs/publications.Html

- 18.Abdirahman H, Fleming LC, Jacobsen KH. Parental involvement and bullying among middle-school students in North Africa. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19(3):227–233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Population Commission of Nigeria, UNICEF Nigeria, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Violence Against Children in Nigeria: Findings From a National Survey 2014, Summary Report. Abuja, Nigeria: UNICEF; 2015. Available at: www.togetherforgirls.org/wp-content/uploads/SUMMARY-REPORT-Nigeria-Violence-Against-Children-Survey.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown DW, Riley L, Butchart A, Kann L. Bullying among youth from eight African countries and associations with adverse health behaviors. Ped Health. 2008;2(3):289–299 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming LC, Jacobsen KH. Bullying among middle-school students in low and middle income countries. Health Promot Int. 2010;25(1):73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2094–2100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudatsikira E, Mataya RH, Siziya S, Muula AS. Association between bullying victimization and physical fighting among Filipino adolescents: results from the Global School-Based Health Survey. Indian J Pedlatr. 2008;75(12):1243–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaikh MA. Bullying victimization among school-attending adolescents in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63(9):1202–1203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.UNICEF. ChlldDlsclpllnaryPractlcesat Home: Evldence From a Range of Low- and Mlddle-Income Countrles. New York, NY: UNICEF; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Protect Our Children Cambodia. Findings From Cambodia’s Violence Against Children Survey 2013. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: UNICEF;2014. Available at: www.unicef.org/cambodia/UNICEF_VAC_Full_Report_English.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development, Comité de Coordination. Violence Against Children in Haiti: Findings From a National Survey 2012. Port-au-Prince, Haiti: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 28.United Nations Children’s Fund Kenya Country Office, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Violence Against Children in Kenya: Findings From a National Survey, 2010. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Children’s Fund Kenya Country Office; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 29.United Nations Children’s Fund, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Science. Violence Against Children in Tanzania: Findings From a National Survey 2009. Dar es Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania: UNICEF; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, UNICEF, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Collaborating Centre for Operational Research and Evaluation. National Baseline Survey on Life Experiences of Adolescents, 2011. Harare, Zimbabwe: Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency; 2013. Available at: www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/UNICEF_NBSLEA-Report-23-10-13.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reza A, Breiding MJ, Gulaid J, et al. Sexual violence and its health consequences for female children in Swaziland: a cluster survey study. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1966–1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Currie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A, et al. , eds. Soclal Determlnants of Health and Well- Belng Among Young People Health Behavlor ln School-aged Chlldren (HBSC) Study: Internatlonal Report From the 2009/2010 Survey (Health Pollcy for Chlldren and Adolescents, No. 6). Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delfabbro P, Winefield T, Trainor S, et al. Peer and teacher bullying/victimization of South Australian secondary school students: prevalence and psychosocial profiles. Br JEduc Psychol. 2006;76(pt 1):71–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh L, McGee R, Nada-Raja S, Williams S. Brief report: Text bullying and traditional bullying among New Zealand secondary school students. J Adolesc. 2010;33(1):237–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bardi M, Borgognini-Tarli SM. A survey on parent-child conflict resolution: intrafamily violence in Italy. Chlld Abuse Negl. 2001;25(6):839–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2013 [published correction appears in MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(26):576]. MMWR Survelll Summ. 2014;63(suppl 4):1–168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clément ME, Chamberland C. Physical violence and psychological aggression towards children: five-year trends in practices and attitudes from two population surveys. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31(9):1001–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby SL. The victimization of children and youth: a comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreat. 2005;10(1):5–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clément ME, Bouchard C. Predicting the use of single versus multiple types of violence towards children in a representative sample of Quebec families. Child Abuse Negl 2005;29(10):1121–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: an update. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(7):614–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner HA, Hamby SL. Trends in children’s exposure to violence, 2003 to 2011. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(6):540–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perlus JG, Brooks-Russell A, Wang J, lannotti RJ. Trends in bullying, physical fighting, and weapon carrying among 6th- through 10th-grade students from 1998 to 2010: findings from a national study. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):1100–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peltonen K, Ellonen N, Poso T, Lucas S. Mothers’ self-reported violence toward their children: a multifaceted risk analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(12):1923–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sumner SA, Mercy AA, Saul J, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of sexual violence against children and use of social services - seven countries, 2007–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(21):565–569 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.United Nations Children’s Fund. Hidden in Plain Sight. New York, NY: UNICEF; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Physical dating violence among high school students—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006:55(19):532–535 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner HA, Hamby SL. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth: an update [published erratum appears in JAMA Pediatr. 2015:168(3):286]. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(7):614–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Oliveira WA, Silva MA, de Mello FC, Porto DL, Yoshinaga AC, Malta DC. The causes of bullying: results from the National Survey of School Health (PeNSE). RevLatAm Enfermagem. 2015;23(2):275–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rutherford GW, McFarland W, Spindler H, et al. Public health triangulation: approach and application to synthesizing data to understand national and local HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rehm J, Rehn N, Room R, et al. The global distribution of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking. Eur Addict Res. 2003;9(4):147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.lachan R, Schulman J, Powell-Griner E, Nelson DE, Mariolis P, Stanwyck C. Pooling state survey health data for national estimates: The CDC behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 1995. In: Cynamon ML, Kulka RA, eds. Seventh Congress on Survey Research Methods. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001:221–226 (Publication No. PHS 01–1013). Available at: http://www.amstat.org/sections/srms/Proceedings/papers/1999_124.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 53.United States Census Bureau International Data Base. Available at: https://www.census.gov/population/international/data/idb/informationGateway.php. Accessed November 30, 2015

- 54.Stein A, Desmond C, Garbarino J, et al. Predicting long-term outcomes for children affected by HIV and AIDS: perspectives from the scientific study of children’s development. AIDS. 2014;28(suppl 3):S261–S268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCormick KF. Attitudes of primary care physicians toward corporal punishment. JAMA. 1992;267(23):3161–3165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tirosh E, Offer Shechter S, Cohen A, Jaffe M. Attitudes towards corporal punishment and reporting of abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(8):929–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Waldfogel J, Brooks-Gunn J. Spanking and child development across the first decade of life. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/132/5/e1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, et al. World report on violence and health. 2002. Available at: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/introduction.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2015

- 59.Jud N, Trocmé A. Physical abuse and physical punishment in Canada. Available at: http://cwrp.ca/infosheets/physical-abuse-a-physical-punishment-canada. Accessed August 6, 2015

- 60.Hecker T, Hermenau K, Isele D, Elbert T Corporal punishment and children’s externalizing problems: a cross-sectional study of Tanzanian primary school aged children. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;38(5):884–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Brooks-Gunn J, Waldfogel J. Spanking and children’s externalizing behavior across the first decade of life: evidence for transactional processes. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(3):658–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Coley RL, Kull MA, Carrano J. Parental endorsement of spanking and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems in African American and Hispanic families. J Fam Psychol. 2014;28(1):22–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jud A, Fluke J, Alink LR, et al. On the nature and scope of reported child maltreatment in high-income countries: opportunities for improving the evidence base. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2013;33(4):207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fluke JD, Goldman PS, Shriberg J, et al. Systems, strategies, and interventions for sustainable long-term care and protection of children with a history of living outside of family care. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(10):722–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.UNICEF. Ending Violence Against Children: Six Strategies for Action. New York, NY: UNICEF; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hillis SD, Mercy JA, Saul J, Gleckel J, Abad N, Kress H. THRIVES: A Global Technical Package to Prevent Violence Against Children. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 67.The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Guidance for Orphans and Vulnerable Children Programming. Washington, DC: US State Department; 2012. Available at: www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/195702.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 68.Finkelhor D, Jones L. Why have child maltreatment and child victimization declined? J Soc Issues. 2006;62 (4):685–716 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bass JK, Annan J, McIvor Murray S, et al. Controlled trial of psychotherapy for Congolese survivors of sexual violence. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2182–2191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wethington HR, Hahn RA, Fuqua-Whitley DS, et al. ; Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The effectiveness of interventions to reduce psychological harm from traumatic events among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(3):287–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(6):478–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Knox M, Burkhart K. A multi-site study of the ACT Raising Safe Kids program: predictors of outcomes and attrition. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;39:20–24 [Google Scholar]

- 73.CPC Livelihoods and Economic Strengthening Task Force. The Impacts of Economic Strengthening Programs on Children. New York, NY: Columbia University; 2011. Available at:http://toolkit.ineesite.org/resources/ineecms/uploads/1440/The_Livelihoods_and_Economic_Strengthening_Task_Force_2011_The_impacts_of_economic_strengthening.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gupta J, Falb KL, Lehmann H, et al. Gender norms and economic empowerment intervention to reduce intimate partner violence against women in rural Cote d’Ivoire: a randomized controlled pilot study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hahn R, Fuqua-Whitley D, Wethington H, et al. ; Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Effectiveness of universal school-based programs to prevent violent and aggressive behavior: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(suppl 2):S114–S129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sarnquist C, Omondi B, Sinclair J, et al. Rape prevention through empowerment of adolescent girls. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/133/5/e1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Foshee VA, McNaughton Reyes HL, Ennett ST, Cance JD, Bauman KE, Bowling JM. Assessing the effects of Families for Safe Dates, a family-based teen dating abuse prevention program. JAdolescHealth. 2012;51 (4):349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, et al. Findings from the SASA! Study: a cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of a community mobilization intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV risk in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Med. 2014;12:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Banyard VL, Moynihan MM, Plante EG. Sexual violence prevention through bystander education: an experimental evaluation. J Community Psychol. 2007;35 (4):463–481 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Coker AL, Cook-Craig PG, Williams CM, et al. Evaluation of Green Dot: an active bystander intervention to reduce sexual violence on college campuses. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(6):777–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.PROMUNDO. Engaging Men to Prevent Gender-Based Violence: A Multi-Country Intervention and Impact Evaluation Study. Washington, DC: Promundo; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bussman KD, Erthal C, Schroth A. Effects of banning corporal punishment in Europe: a five-nation comparison In: Durrant JE, Smith AB, eds. Global Pathways to Abolishing Physical Punishment. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K. Childrearing discipline and violence in developing countries. Child Dev. 2012;83(1):62–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Osterman K, Bjorkqvist K, Wahlbeck K. Twenty-eight years after the complete ban on the physical punishment of children in Finland: trends and psychosocial concomitants. Aggress Behav. 2014;40(6):568–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roberts JV. Changing public attitudes towards corporal punishment: the effects of statutory reform in Sweden. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(8):1027–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sariola H Attitudes Towards Corporal Punishment of Children in Finland. Finland: Finnish Social Science Data Archive; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Frieden TR. Six components necessary for effective public health program implementation. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):17–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Betancourt TS, Fawzi MK, Bruderlein C, Desmond C, Kim JY. Children affected by HIV/AIDS: SAFE, a model for promoting their security, health, and development. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15(3):243–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Consultative Group on Early Childhood Care and Development. The essential package: holistically addressing the needs of young vulnerable children and their caregivers affected by HIV/ AIDS. Available at: www.ecdgroup.com/pdfs/EPBrochure%20Final.pdf. Accessed June 2012

- 90.Mercy JA, Hillis S, Butchart A, et al. Interpersonal violence: global burden and paths to prevention. In: Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 3rd ed. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Duff JF, Buckingham WW III. Strengthening of partnerships between the public sector and faith-based groups. Lancet 2015;386(10005):1786–1794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.The Mother and Child Project. In: Gates M, Warren K, eds. Raising Our Voices for Health and Hope. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervon; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jamison D, Gelband S, Horton S, Jha P, Laxminarayan R, Nugent R, eds. End Violence: A Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016In press [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.