Abstract

Background:

The spleen is most the commonly injured solid organ in abdominal trauma. Operative management (OM) has been challenged by several studies favoring successful non-OM (NOM) aided by modern era interventional radiology. The results of these studies are confounded by associated injuries impacting outcome. The aim of this study is to compare NOM and OM for isolated splenic injury in an Indian Level 1 Trauma Center.

Materials and Methods:

This is a retrospective analysis of prospective database.

Results:

A total of 1496 patients were admitted with abdominal injuries. One hundred and twenty-nine patients admitted with diagnosis of isolated splenic injury from January 2009 to December 2016 were included in the study. RTIs, followed by falls from height, were the most common mechanisms of injury. Ninety-two (71.3%) patients with isolated splenic trauma were successfully managed nonoperatively. Thirty-seven (28.7%) required surgery, of which three were due to the failure of NOM. Three patients in the nonoperative group underwent splenectomy later, giving an overall success rate of 96.8% for NOM. Patients with isolated splenic trauma requiring OM had higher grade splenic injury (Grade 4/5), higher blood transfusion requirements (P < 0.001), and prolonged Intensive Care Unit and hospital stay in comparison to patients in the nonoperative group. No patient died in the NOM group; two patients died in the splenectomy group due to hemorrhagic shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome, respectively.

Conclusion:

Although NOM is successful in most patients with blunt isolated splenic injuries, careful selection is the most important factor dictating the success of NOM.

Keywords: Blunt splenic injury, nonoperative management, operative management, spleen, splenectomy

INTRODUCTION

The spleen is the most frequently injured solid organ following blunt abdominal trauma, accounting for up to 50% of all abdominal solid organ injuries in some reports.[1] Operative management (OM) used to be the norm until some decades ago.[2] With the discovery of angiographic embolization and the immunological importance of spleen, especially in the pediatric age group, there has been increasing interest in splenic preservation if injury is not causing an immediate threat to life.[3]

The normal adult spleen weighs between 100 g and 250 g. Histologically, the spleen is divided into red pulp and white pulp.[4] The red pulp is a series of large vascular passages that filter old red blood cells and trap bacteria. This allows bacterial wall antigen presentation to the lymphocytes in the adjacent white pulp, which is filled largely with lymphocytes. Lymphocyte exposure to antigens results in the production of immunoglobulins (IgM), the most common of which is IgM. The white pulp is also the site of production of opsonins such as tuftsin and properdin and complement activation in response to appropriate stimuli.[5] All these functions of the spleen are lost after splenectomy, making the patient vulnerable for overwhelming infections (OPSI).[3]

Splenic trauma can present with life-threatening hemodynamic instability, mandating immediate surgery as a life-saving measure. Non-OM (NOM) is reasonable for hemodynamically stable patients. Penetrating injuries to the spleen are often managed operatively because of concern regarding associated intraperitoneal injuries.[6] About 40% of patients with splenic injury require immediate operative intervention.[7]

Currently, modern diagnostic imaging has enabled more accurate staging and monitoring of splenic injuries, and an improvement in interventional radiology techniques has further encouraged the NOM approach.[7] Thus, splenectomy is now one of several possible treatment choices, rather than the only accepted approach. As many patients also have other associated injuries, management decisions are often biased. The aim of this study is to compare outcomes in NOM with surgery in isolated splenic trauma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was cleared by the Institutional Ethics Committee. This trauma center is one of the very few level-one trauma centers in this country with an annual ED census of 75,000. Retrospective review of a prospectively maintained trauma registry was done. All patients presenting to our ED with abdominal trauma, blunt or penetrating, found to have isolated splenic injuries on workup, with or without minor soft-tissue injuries, admitted between January 2009 and December 2016 were included in the study. Patients with associated intra/extra-abdominal injury were excluded from the study. During this study period, 1496 patients were admitted with abdominal injuries.

Patients were divided into two groups:

Group 1: Patients who received NOM, with/without splenic artery angioembolization (AE)

Group 2: Patients who received OM.

The Splenic Organ Injury Score system of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, 1994 Revision, was used for staging.[8]

Treatment protocol

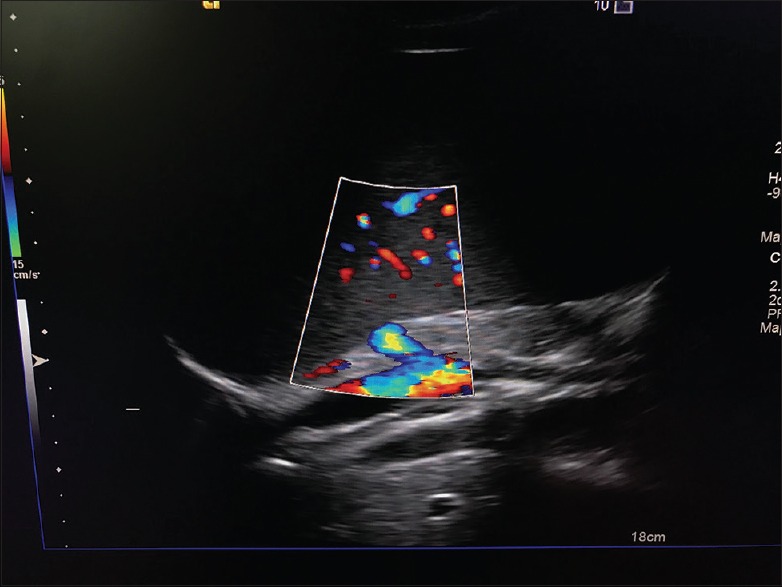

All trauma patients underwent initial assessment and management as per standard ATLS guidelines. Hemodynamically unstable patients with evidence of hemorrhage in the abdomen (FAST positive) were taken for exploratory laparotomy (OR). FAST-positive patients with abdominal trauma were planned for definitive imaging (contrast-enhanced computed tomography) if hemodynamically stable. Therapeutic AE was done for any contrast extravasations or pseudoaneurysm in abdominal solid organs if the patient remains hemodynamically stable. Prophylactic AE of the injured spleen was done if CT shows a Grade 4/5 injury of the spleen. Patients undergoing NOM were closely monitored with regular monitoring of vitals, abdominal girth measurement, and hematocrit values and subsequently discharged on 5–6th days of admission after getting a duplex ultrasound done to rule out any subsequently developed vascular and parenchymal anomaly [Figure 1]. Operated patients were discharged as and when they become stable for discharge to home care.

Figure 1.

Duplex ultrasound images on day 5 following Grade 4 splenic injury showing normal splenic artery anatomy

All patients postsplenectomy were vaccinated with meningococcal, influenza, and pneumococcal vaccines after day 14 posttrauma, usually in the follow-up outpatient department. All patients were advised to receive booster vaccination in follow-up after 5 years. Vaccination was not done for patients undergoing splenic AE, not undergoing surgery thereafter.

Variables studied included age, gender, mechanism of injury, FAST status, admission hemoglobin, amount of red blood cell transfused, grade of splenic injury, length of Intensive Care Unit (ICU), and hospital stay and eventual outcome. Data were entered in Microsoft Excel sheet, and analysis was done using Independent sample t-test, Chi-square test, and Mann–Whitney U-test as per requirement. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

One hundred and twenty-nine patients were eligible for inclusion in the study. Majority of patients 103 were male and 26 were female (m: f - 3.96:1). The mean age of patients was 25.4 years (range 1–75 years), and majority (79%) belonged to the age group of 11–40 years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age distribution in patients of isolated splenic trauma (n=129)

| Age group (years) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 1-10 | 15 (11.6) |

| 11-20 | 37 (28.7) |

| 21-30 | 45 (34.9) |

| 31-40 | 20 (15.5) |

| 41-50 | 6 (4.65) |

| 51-60 | 4 (3.1) |

| 61-70 | 1 (0.77) |

| >70 | 1 (0.77) |

Road traffic injuries (RTIs) were the mode of injury in 60 (46.5%) patients, followed by accidental falls in 47 (36.4%) and assault in 22 (17%) of the cases. Majority (100 [77.5%]) patients were brought to the emergency department by relatives and known persons, and the remaining (29 [22.5%]) were brought by police and state ambulance services.

Only one (0.8%) patient had penetrating injury, while 128 (99.2%) patients had blunt abdominal trauma. FAST was positive in 125 (96.9%) patients and negative in 4 (3.1%) patients.

Ten patients were presented in class III/IV shock.

One hundred and nineteen patients had splenic injury diagnosed by CT. Ten patients were taken to OR directly in view of hemodynamic instability, and their splenic injury and grade were diagnosed intraoperatively.

Ninety-five patients were selected for NOM based on hemodynamic stability. Of these, 25 underwent AE, 17 prophylactic and 8 therapeutic – 3 for contrast extravasation and 5 for pseudoaneurysms in the splenic artery or its branches. Thirty-four patients were selected for OM because of hemodynamic instability, 31 of these were transient responders, and 3 were nonresponders. One patient of Grade 2 injury underwent splenorrhaphy and remaining 33 patients had splenectomy.

The mean hemoglobin at the time of admission of NOM group (10.6 g %) was slightly higher than the OM group (10.4 g %), and the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.592).

Only 15 of 95 (15.7%) patients in the NOM group needed ICU care, whereas 14 of 34 (41.1%) patients recovering from emergency surgery required admission to ICU. The difference was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.001).

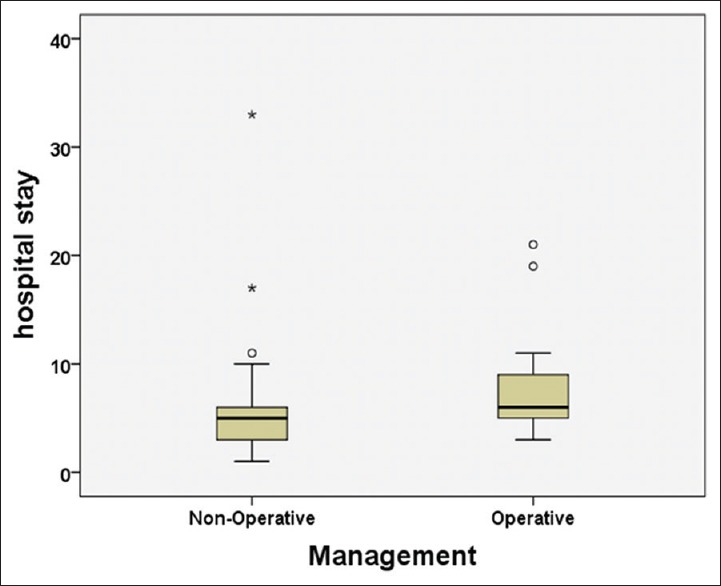

The median length of hospital stay was lower in the NOM group (5.0 days) than in patients with OM (6.0 days), and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Box plot comparing median hospital stay in operative and nonoperative groups

Table 2 compares the various parameters in the two groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of various parameters between two groups

| Variables | Nonoperative (n=95) | Operative (n=34) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hb, mean±SD | 10.6±2.5 | 10.4±2.3 | 0.623* |

| Blood transfusion, frequency (%) | |||

| None | 69 (72.6) | 7 (20.6) | <0.001† |

| One or more | 26 (27.4) | 27 (79.4) | |

| Hospital stay, median (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0) | 6.0 (4.0) | <0.001‡ |

| Grade of splenic injury, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0) | 4.0 (1.0) | <0.001‡ |

| Mean ICU stay (days) (%) | 15 (15.7) | 14 (41.1) | <0.001† |

| Readmission (%) | 3 (3.16) | 3 (8.82) | 0.34† |

*Independent sample t-test; †Chi-square test; ‡Mann-Whitney U-test. Hb: Hemoglobin, SD: Standard deviation, IQR: Interquartile range, ICU: Intensive Care Unit

There was failure of NOM in 3 (3.2%) patients; all were young males and postangioembolization. Two patients, one with Grade 4 injury following accidental fall and other with Grade 5 injury following RTI, needed splenectomy within 24 h of AE due to hemodynamic instability and continued transfusion requirements. One patient with Grade 4 injury following RTI, who was readmitted 2 days after discharge with abdominal pain, had to undergo splenectomy due to hemodynamic instability 1 week after embolization [Table 3].

Table 3.

Operative, nonoperative, and failure of nonoperative management in isolated splenic trauma

| Grade | OM (n=34) | NOM (n=95) | Angioembolization (n=25) | NOM failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | 6 | - | - |

| 2 | 1* | 18 | 1 | - |

| 3 | 4 | 40 | 7 | - |

| 4 | 13 | 28 | 14 | 2 |

| 5 | 16 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

*Underwent splenorrhaphy. NOM: Nonoperative management, OM: Operative management

The OM group patients needed more red cell transfusion than NOM group, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

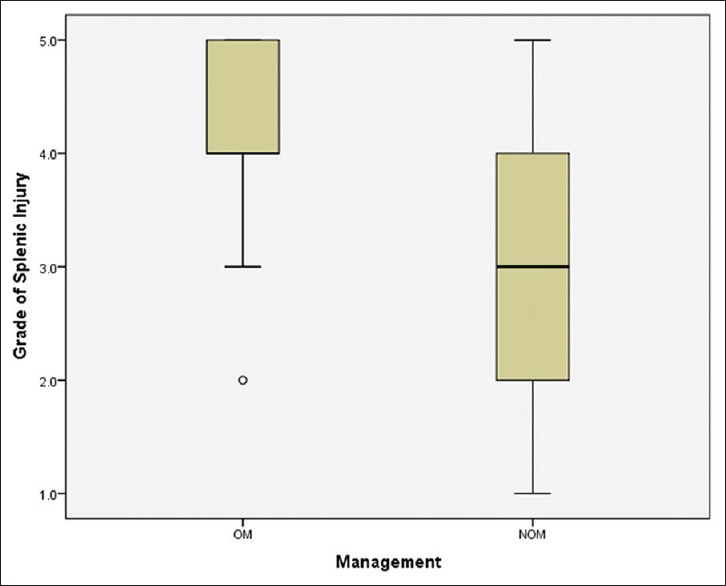

Patients with OM had higher grades of splenic injury with 81 (85%) having Grade 4/5 injury (median Grade 4.0). Patients with NOM had lower grades of injury with 67% having Grade 1–3 injury (6%, 19%, and 42%, respectively) with median Grade 3.0 [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Box plot showing grades of splenic injury in operative and nonoperative groups

Overall out of 129 patients, 60 (46.5%) had Grade 4/5 splenic injuries, of which 29 underwent immediate splenectomy and 31 underwent NOM with AE. Of the latter group, three patients had failure of NOM and underwent splenectomy subsequently, giving an overall splenic salvage rate of 46.6% in Grade 4/5 splenic injuries.

There was mortality of two patients in operative group and there was no mortality in NOM group (5.88% OM vs. 0% NOM), and the difference could not be tested statistically because of zero mortality in one group. One patient was a 42-year-old male with blunt trauma abdomen (BTA) due to RTI who had Grade 5 splenic injury and underwent splenectomy, but this patient succumbed due to irreversible hemorrhagic shock. Another patient which could not be saved was a 24-year-old adult male with BTA due to fall from height with Grade 5 splenic rupture, who underwent splenectomy but died after 7 days due to acute respiratory distress syndrome and sepsis.

Out of 129 patients, six patients needed readmission within 2 weeks of discharge, 3 (3.1%) in NOM group and 3 (8.8%) in OM group, and the difference was statistically insignificant (P = 0.034). Two follow-up patients of NOM needed left-side ICD insertion for pleural effusion. One patient in the NOM group got readmitted with delayed splenic rupture and underwent splenectomy 2 days postdischarge (7 days after index admission and angioembolization) and presented to emergency department with abdominal pain and hypovolemic shock. One follow-up patient in the splenectomy group needed left-side ICD insertion and two others required pigtail insertion for splenic fossa collections. All patients made uneventful recoveries. No splenectomy follow-up patient returned during the period of follow-up with complaints in keeping with OPSI.

DISCUSSION

NOM of traumatic splenic injuries has become the standard of care in hemodynamically stable patients.[9,10,11] Reasons for increased adoption of NOM for abdominal solid organ trauma include improved quality and accessibility of computed tomography, better understanding of the physiology of critically ill patients, dedicated trauma nursing making close monitoring effective, round-the-clock availability of ORs in trauma centers, and increased availability and expertise in AE. Multiple studies have confirmed the success and efficacy of NOM.[11,12] Success rates of around 80% have been reported in the literature for NOM of traumatic splenic injuries.[10,11,12,13] In this study, the success rate of NOM was 96.8%. We attribute this remarkable success rate of NOM to cautious selection of patients for NOM. Accumulation of experience over time may also have increased the beneficial impact on the above.

The advantage of NOM is not only the preservation of splenic function but it also averts the complications associated with laparotomy. The major disadvantage is the sequel of a delayed surgical intervention, if required.[14,15] It is thus crucial to carefully monitor the patients receiving NOM, following the established protocol. In our series, two patients deteriorated in the first 24 h of AE, and another had a delayed complication after 7 days. Owing to close monitoring, patients were identified in a timely fashion, thereby preventing catastrophe.

Di Saverio and Moore highlighted that patients with Grade 4/5 splenic injury were at increased risk for developing complications and a higher NOM failure rate even though NOM is being utilized increasingly for high-grade lesions.[16] Similarly, Peitzman and Richardson showed in their studies that the NOM failure rate was proportional to the splenic injury grade: 5% in Grade 1, 10% in Grade 2, 20% in Grade 3, 33% in Grade 4, and 75% in Grade 5.[17] Comparable failure rates were seen in the study conducted by Velmahos in 14 trauma centers, with failure rates of 34.5% for patients with Grade 4 lesions and 60% for Grade 5 lesions.[18] In our series, 71.3% of the patients were successfully managed conservatively. No NOM failed in Grade 1–3 splenic injuries (64/95; 67.3% of NOM injuries). Failure of NOM occurred only in Grade 4/5 injuries (3/31 patients; 9.6%). Notably, whereas 31.7% (13/41) of Grade 4 injuries required splenectomy, 84.2% (16/19) of Grade 5 injuries required splenectomy, which is in agreement with Peitzman et al.

Our initial operative intervention rate of 26.4% is comparable to other centers.[19] Splenorrhaphy should only be carried out in hemodynamically stable patients who have a salvageable spleen, i. e., low grade of injury. We had one patient of Grade 2 injury who underwent splenorrhaphy.[20] Splenectomy is indicated in extensive splenic parenchymal injuries leading to hemodynamic instability. In our series, as majority of patients in OM group were hemodynamically unstable, all but one patient underwent splenectomy.

In the majority of cases, splenic rupture presents acutely, and in about 15% cases, it presents days to weeks later after a significant abdominal injury with a delayed rupture.[21] Of 95 patients, there was one postangioembolization patient who was readmitted with delayed splenic rupture and underwent splenectomy. Patients with splenic trauma who present acutely have 1% mortality while patients with delayed splenic rupture have 15% mortality.[22,23]

CONCLUSION

Isolated splenic injuries are mainly due to blunt abdominal trauma following RTI and falls from height and most commonly involve the younger population group. NOM can be adopted in the majority of patients with blunt isolated splenic injuries with careful patient selection. However, enthusiasm for NOM should not let a bleeding spleen threaten the patient's life. Patients with higher grades of splenic injury are more likely to require operative intervention. This group is further characterized by need of more blood transfusion, prolonged ICU and hospital stay, and higher mortality in comparison to patients of nonoperative group. Although the majority of patients managed nonoperatively can safely be discharged on the 5th day of admission, an occasional NOM patient may experience late deterioration even after this window, and close follow-up should be ensured to prevent a dismal outcome. No cases of OPSI occurred in 8 years of managing splenic trauma.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all members of trauma nurse coordinators, Department of Surgery, Division of Trauma and Critical Care, JPN Apex Trauma Center, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, who helped in data collection and all those who were involved in the care of our patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sosada K, Wiewióra M, Piecuch J. Literature review of non-operative management of patients with blunt splenic injury: Impact of splenic artery embolization. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2014;9:309–14. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2014.44251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgenstern L. American Psychiatric Publishing. In: Hiatt JR, Phillips EH, Morgenstern L, editors. Surgical Diseases of the Spleen. New York: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.David HW. Injury to spleen. In: Mattox KL, Moore EE, Feliciano DV, editors. Trauma. 7th ed. New York: MacGraw Hill; 2013. pp. 561–80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch AM, Kapila R. Overwhelming postsplenectomy infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1996;10:693–707. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shatz DV, Romero-Steiner S, Elie CM, Holder PF, Carlone GM. Antibody responses in postsplenectomy trauma patients receiving the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine at 14 versus 28 days postoperatively. J Trauma. 2002;53:1037–42. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harbrecht BG, Peitzman AB, Rivera L, Heil B, Croce M, Morris JA, Jr, et al. Contribution of age and gender to outcome of blunt splenic injury in adults: Multicenter study of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 2001;51:887–95. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velmahos GC, Toutouzas KG, Radin R, Chan L, Demetriades D. Nonoperative treatment of blunt injury to solid abdominal organs: A prospective study. Arch Surg. 2003;138:844–51. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.8.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Jurkovich GJ, Shackford SR, Malangoni MA, Champion HR, et al. Organ injury scaling: Spleen and liver (1994 revision) J Trauma. 1995;38:323–4. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brasel KJ, DeLisle CM, Olson CJ, Borgstrom DC. Splenic injury: Trends in evaluation and management. J Trauma. 1998;44:283–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199802000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longo WE, Baker CC, McMillen MA, Modlin IM, Degutis LC, Zucker KA, et al. Nonoperative management of adult blunt splenic trauma. Criteria for successful outcome. Ann Surg. 1989;210:626–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198911000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pachter HL, Guth AA, Hofstetter SR, Spencer FC. Changing patterns in the management of splenic trauma: The impact of nonoperative management. Ann Surg. 1998;227:708–17. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balaa F, Yelle JD, Pagliarello G, Lorimer J, O'Brien JA. Isolated blunt splenic injury: Do we transfuse more in an attempt to operate less? Can J Surg. 2004;47:446–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan KK, Chiu MT, Vijayan A. Management of isolated splenic injuries after blunt trauma: An institution's experience over 6 years. Med J Malaysia. 2010;65:304–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luna GK, Dellinger EP. Nonoperative observation therapy for splenic injuries: A safe nontherapeutic option? Am J Surg. 1987;153:462–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(87)90794-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers JG, Dent DL, Stewart RM, Gray GA, Smith DS, Rhodes JE, et al. Blunt splenic injuries: Dedicated trauma surgeons can achieve a high rate of nonoperative success in patients of all ages. J Trauma. 2000;48:801–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Saverio S, Moore EE, Tugnoli G, Naidoo N, Ansaloni L, Bonilauri S, et al. Non operative management of liver and spleen traumatic injuries: A giant with clay feet. World J Emerg Surg. 2012;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peitzman AB, Richardson JD. Surgical treatment of injuries to the solid abdominal organs: A 50-year perspective from the journal of trauma. J Trauma. 2010;69:1011–21. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f9c216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velmahos GC, Zacharias N, Emhoff TA, Feeney JM, Hurst JM, Crookes BA, et al. Management of the most severely injured spleen: A multicenter study of the Research Consortium of New England Centers for Trauma (ReCONECT) Arch Surg. 2010;145:456–60. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peitzman AB, Heil B, Rivera L, Federle MB, Harbrecht BG, Clancy KD, et al. Blunt splenic injury in adults: Multi-institutional study of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 2000;49:177–87. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200008000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feliciano DV, Bitondo CG, Mattox KL, Rumisek JD, Burch JM, Jordan GL, Jr, et al. A four-year experience with splenectomy versus splenorrhaphy. Ann Surg. 1985;201:568–75. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198505000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peera MA, Lang ES. Delayed diagnosis of splenic rupture following minor trauma: Beware of comorbid conditions. CJEM. 2004;6:217–9. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500006874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dang C, Schlater T, Bui H, Oshita T. Delayed rupture of the spleen. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:399–403. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cary C, McDonald MD. Delayed splenic hematoma rupture. Am J Emerg Med. 1915;13:540–2. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(95)90167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]