Abstract

Background:

Surviving sepsis campaign (SSC) recommends 6 h-sepsis resuscitation bundle for severe sepsis (now termed “sepsis” after the Sepsis-3 definition) or septic shock. The study was done to assess the guideline compliance in Indian patients before and after the resident physicians' training and their impact on the survival.

Subjects and Methods:

Prospective interventional study (time series design) was conducted. Resident physicians, who were regularly managing the patients of severe sepsis/septic shock, were trained by providing the education and feedback on the guideline compliance at 6-month intervals for three quality improvement (QI) phases. Case details of preintervention and QI phases' patients were reviewed as per the quality indicators, defined by SSC guideline, and compared.

Results:

The baseline compliance of composite six components of 6 h-sepsis resuscitation bundle was low and significantly increased on postintervention (baseline 0% to 18% at QI 3 (P for trend = 0.01). The compliance of individual components was improved too: serum lactate measurement (26%, P = 0.002), obtaining blood culture (28%, P = 0.003), antibiotic administration (2%, P = 0.56), provision of fluid bolus (60%, P = 0.02), attainment of target central venous pressure (50%, P = 0.03), and optimization of central venous oxygen saturation (20%, P = 0.21). The hospital mortality showed a decreasing trend (18%, P = 0.06). Patients compliant to composite bundle got the mortality benefit (odds ratios = 0.25, 95% [confidence interval, 0.07–0.9]). The study, however, did not show any benefits of mean hospital/Intensive Care Unit (ICU) length of stay.

Conclusions:

The study establishes lack of acceptance to the prevailing guideline; however, it has shown a significant improvement in adaptation and mortality benefit without reducing mean hospital/ICU length of stay after physicians' repeated educational programs. The barriers to implementation of the prevalent guideline should be searched out in further trials.

Keywords: Adults, checklist, quality appraisal, resource-poor setting, sepsis guideline

INTRODUCTION

Severe sepsis (now termed “sepsis” after the Sepsis-3 definition) and septic shock have a higher mortality rate approaching 50%.[1,2] Besides early initiation of antimicrobials, until recently, there is no scientific basis for early recognition of high-risk sepsis patients or practice standard for hemodynamic optimization and adjunctive pharmacologic therapies in the emergency department.[3] In 2004, a surviving sepsis campaign (SSC) recommendations were published to increase the awareness among the clinicians and public to improve the outcome in severe sepsis/septic shock, and which were revised in 2008, 2012, and off late in 2016.[4,5,6] A meta-analysis demonstrated that the performance improvement programs were associated with a significant increase in compliance with the SSC bundles and a reduction in the mortality.[7] Henceforth, the SSC guideline recommends “3 and 6-h bundle,” also known as “sepsis resuscitation bundle,” focusing on the early identification, blood culture, early antibiotics, and hemodynamic reassessment. This sepsis bundle-based approach significantly improves the survival benefit as evidenced by another meta-analysis.[8]

The development and publication of the guidelines often do not lead to changes in clinicians' bedside practices in a timely fashion. Adopting or de-adopting new evidence-based practices among health-care persons are sometimes found to be delayed, without any clear reasons. The most effective mean for achieving the knowledge transfer remains an unanswered question across all medical disciplines. However, repeated education/trainings in acquiring skills are the only old known method to overcome this hurdle. A study by Ferrer et al. on the impact of a national educational program to care the septic patients in compliance with SSC guideline shows an initial improvement that drops to low level in 1 year after the intervention.[9] Hence, learning/skill has to be adopted again and again. It has also been emphasized that learning has to be based on a protocol based bundle approach to improve the sepsis outcome.

There is a scarcity of the data in India with regard to the effective use of the SSC guideline and their outcome. As per MOSAICS study (2012), done in Asian Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients, compliance rate for the entire resuscitation bundle is only 6.8%, and there is doubling of the mortality rate in the noncompliance group of patients compared to the compliance.[10,11] We hypothesize that the baseline compliance to the SSC guideline would be highly variable in a resource-poor setting like India, where timely approach of the patients to the health-care facilities and adequate health infrastructures including the availability of internists are variably constrained. Henceforth, we did a pre- and post-interventional study at a tertiary care health center of North India. The primary objective of the study was to know the compliance to the SSC guideline at baseline and after three consecutive quality improvement (QI) interventions by resident physicians' training at 6-month interval. The secondary objective was to find the impact of interventions on variables such as mortality and length of the hospital/ICU stay.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study settings and participants

The prospective interventional study (time series study design) was conducted in the Department of Emergency and Internal Medicine at a referral hospital, North India in a period from July 2011 to March 2013. Included patients were those who fulfilled the criteria for severe sepsis and septic shock as per the SSC guideline. Severe sepsis (now termed “sepsis” after the Sepsis-3 definition) was defined as sepsis with one or more signs of organ dysfunction (cardiovascular, renal, respiratory, hematologic, and unexplained metabolic acidosis). Septic shock was defined as sepsis with hypotension (arterial blood pressure <90 mmHg systolic, or 40 mmHg less than patient's normal blood pressure) for at least 1 h despite adequate fluid resuscitation or need for vasopressors to maintain systolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg or mean arterial pressure ≥70 mmHg. Excluded patients were those who had age <12 years, trauma, active hemorrhage, metastatic malignancy, acute cerebral vascular event, acute coronary syndrome, and acute pulmonary edema. The recruited patients were from the emergency ward, medicine ward, and medicine ICU. Because the study involved time factor of 6 h-sepsis bundle to assess, onset of severe sepsis (time zero) was determined according to the location of the patient within the hospital when severe sepsis was diagnosed. In patients of the emergency ward, time zero was defined as the time of admission in the emergency admission card. For patients admitted to medical wards or ICU, time zero was determined by searching the clinical progress note in the patients' case files.

Sample size

Target sample was determined to be 50 patients in each study unit (baseline and three QI phases) after considering the average admission rate of severe sepsis patients in the last four 6-month in the medicine-cum-emergency department, compliance improvement rate a previous study (20.4%), 80% power of the study, and 95% confidence interval (CI).[7]

Interventions

The study was conducted in two phases over 21 months: Baseline phase, 3 months' time period and intervention phase, three QI phases (QI 1 to QI 3) – each 6 months' time period. Resident physicians were chosen for intervention/training because of their lead role during the 6 h-sepsis bundle resuscitation in clinical practice of the hospital among other staffs (e.g., nurses and technicians) involved in the teamwork. Patients' case files were also filled by them. They were the postgraduate trainee of the hospital/institution. Every 6 months, a new batch of 5–10 residents had entered to the postgraduate education of the institution and at one point of time 50–60 residents were there. New residents usually learned the methods of interventions from senior residents and consultants. During this training session, three new batches of residents had entered. They were continuously educated with the series of lectures and checklist of sepsis resuscitation bundle, delivered weekly batch by batch (total 4 batches). Lectures were delivered by the investigators. Residents had also used the checklist approach for the bundle in the case file so that their learning got improved day-by-day and our study progressed to the precision. The same thing continued in each phase of QI resulting improved training of the previous residents and fresh training of newly joined residents. Residents were provided with pocket cards as daily reminders of the bundles. Patient's case files were reviewed during this phase to assess as per the objectives (pro forma based as below) by separate investigators. At the end of each phase, feedbacks were provided to the residents to increase the compliance. Feedback included the number of patients who met indications for the bundle, treatments given, percentage compliance with the bundle quality indicators, and the outcome.

Comparators

Three 6-month interval QI phases were compared with the baseline phase as per the variables as discussed below.

Outcomes

Compliance with each of the 6 h-sepsis resuscitation bundle components was measured by applying a standardized checklist which also included the patient demographics, vital signs, laboratory parameters, physiologic scores (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, [APACHE] II), therapies received, time meeting criteria for initiation of the bundle, sepsis category, completion (yes or no) and time of completion of the bundle quality indicators, completion of the whole bundle, length of hospital stay, and mortality. Quality indicators were defined as per SSC guideline (2008) that includes:

Measurement of serum lactate

Obtaining blood culture before antibiotic administration

Provision of broad-spectrum antibiotic

Provision of fluid bolus in hypotension

Attainment of target central venous pressure (CVP) in patients of septic shock, and

Optimization of central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) in septic shock.

Statistical methods

The data storage and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS software version 19.0, respectively. For categorical variables, frequency and percentage were calculated and compared with the help of the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared with the unpaired Student's t-test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were performed. Odds ratios (OR, 95% CI) were calculated. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Data collection procedures were completed with ensuring the subject confidentiality and blinding procedure among investigators. Verbal consent was obtained from all the residents for the educational training.

RESULTS

Study flow

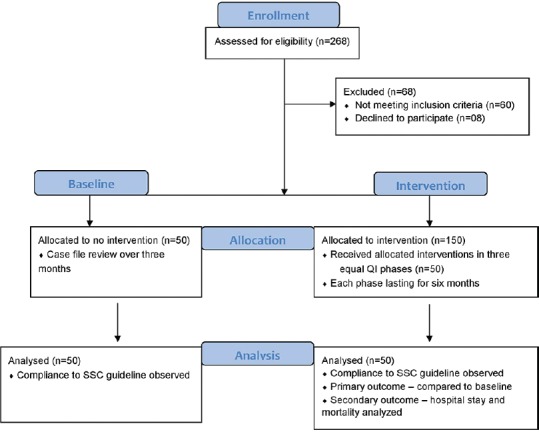

A total of 268 patients' case files were screened, but 200 patients were allocated and analyzed in the study [Figure 1]. The study was in four groups; baseline phase of 3 months with 50 patients and three QI phases of 6-month each with 50 patients in each phase.

Figure 1.

Study flow sheet. Surviving sepsis campaign, surviving sepsis campaign

Baseline variables

Baseline and QI phase groups were similar in major baseline demographics and clinical parameters, including age, blood pressure recording, APACHE score, organ dysfunctions, and blood gas parameters except WBC count that was significantly different, may be due to variations in the etiology of sepsis [Table 1]. Among 200 patients, 156 were in severe sepsis and 44 were in septic shock. The most common cause of sepsis was pneumonia 73% (146/200).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of patients in the baseline and the quality improvement phases

| Patient characteristics | Mean±SD |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | QI 1 | QI 2 | QI 3 | ||

| Age (years) | 52.32±16.4 | 53.64±16.6 | 53.34±17 | 52.24±15.8 | 0.92 |

| APACHE II | 30.9±9.4 | 26.8±9.4 | 27.4±12.5 | 33.7±10.5 | 0.455 |

| MBP (mmHg) | 70±24.4 | 69±20.8 | 72±24.13 | 71±22.21 | 0.545 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.4±1.0 | 1.9±0.7 | 2.0±1.1 | 2.3±0.9 | 0.334 |

| WBC (count/ml ) | 19188 | 15536 | 16848 | 15346 | 0.013 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 11.7±13.4 | 10.4±1.3 | 10.3±2.9 | 11.9±13.1 | 0.747 |

| Platelet count (count/ml ) | 153426 | 109560 | 136080 | 125220 | 0.457 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.91±1.02 | 2.05±1.03 | 2.12±1.01 | 2.02±1.06 | 0.793 |

| Blood urea (mg/dl) | 116.6±56.5 | 90±66.5 | 90±56.3 | 96±56.2 | 0.084 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.7±1.2 | 1.7±0.9 | 1.9±1.1 | 1.7±1.1 | 0.800 |

| pH | 7.35±0.15 | 7.32±0.18 | 7.33±0.17 | 7.34±0.12 | 0.312 |

| HCO3 (mEq/L) | 21.5±9.2 | 20.3±8.3 | 21.4±9.0 | 22.6±8.8 | 0.625 |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 36.44 | 39.53 | 35.85 | 34.75 | 0.7 |

| Temperature (°Fahrenheit) | 97.3±1.3 | 98.4±0.9 | 98.2±1.1 | 97.9±1.4 | 0.443 |

MBP: Mean blood pressure, Hb: Hemoglobin, APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, PCO2: Partial pressure of carbon dioxide, WBC: White blood cell count, QI: Quality improvement, SD: Standard deviation

Primary outcome variables: compliance with surviving sepsis campaign guideline

At baseline, compliance with SSC recommendation was 0% for the composite sepsis resuscitation bundle. Only two components of the bundle showed compliance higher than 50% were serum lactate measurement (77.78%) and early administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics (88.88%). The insertion of a central venous catheter was implemented in 0% of cases for the attainment of CVP and 0% for optimization of ScvO2. The entire SSC protocol compliance showed a progressive and significant improvement from the baseline at 0% compliance, to QI 1–3 phases, at 6%, 14%, 18% compliances, respectively (P for trend = 0.01) [Table 2]. Four components showed statistically significant progressive improvement over QI phases, including the measurement of serum lactate (64% at baseline to 90% at QI 3, P for trend = 0.002), obtaining blood culture before antibiotic administration (4% at baseline to 32% at QI 3, P for trend = 0.003), provision of fluid bolus in hypotension (0% at baseline to 60% at QI 3, P for trend = 0.02), and attainment of target CVP in patients of septic shock (0% at baseline to 50% at QI 3, P for trend = 0.03). Two other components (provision of broad-spectrum antibiotics [90% at baseline to 92% at QI 3, P for trend = 0.56] and optimization of ScvO2 [0% at baseline to 20% at QI 3, P for trend = 0.21]) showed improvement in compliance, however, were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Compliance (%) with 6 h-sepsis resuscitation bundle components in the baseline and the quality improvement phases (n=200)

| Resuscitation bundle (n) | Baseline (n=50) | QI 1 (n=50) | QI 2 (n=50) | QI 3 (n=50) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Serum lactate measurement (200) | 64 | 60 | 80 | 90 | 0.002 |

| 2. Sending blood cultures before antibiotics (200) | 4 | 18 | 26 | 32 | 0.003 |

| 3. Broad-spectrum antibiotics (200) | 90 | 94 | 86 | 92 | 0.55 |

| 4. Fluids bolus administration (44) | 0 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 0.02 |

| 5. CVP >8 mmHg (44) | 0 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 0.036 |

| 6. Optimization of Scvo2 >70% (44) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0.22 |

| 7. Composite bundle completed (200) | 0 | 6 | 14 | 18 | 0.01 |

CVP: Central venous pressure, Scvo2: Central venous oxygen saturation

However, if we compared among individual phases, only two bundle components showed a significant improvement in first QI phase from baseline phase. These were obtaining blood cultures before the antibiotic administration (4% in baseline, 18% in QI 1, P = 0.028) and provision of fluid bolus (0% in baseline, 36.63% in QI 1, P = 0.019). The comparison of QI 1 with QI 2 revealed only one component to be significant (measurement of serum lactate in first 6 h; 60% in QI 1, 80% in QI 2, P = 0.028). Moreover, comparison of QI 2 with QI 3 revealed no significant changes in any components.

Secondary outcome variables

Mortality of the patients with severe sepsis was 34.61% (54/156) while those with septic shock were 59.09% (26/44). The overall hospital mortality showed a decreasing trend throughout the study period and a trend of approaching the significance (50% at baseline, 32% at QI 3, P for trend = 0.06). Furthermore, there was a statistically significant mortality benefit in patients who had the composite bundle completed as compared to those whose bundle was incomplete (OR = 0.25, 95% [CI – 0.07–0.9], P = 0.024). Comparing individual components, measurement of serum lactate, provision of fluid bolus, and optimization of CVP and ScvO2 were independently associated with mortality benefit in their completion; while other components were not [Table 3].

Table 3.

Difference in mortality among patients who had completed 6 h-sepsis resuscitation bundle components and those not completed as per logistic regression analysis

| Resuscitation bundle | Number of patients (completed vs. not completed) | In hospital mortality |

Odds ratio (CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed (%) | Not completed (%) | ||||

| 1. Serum lactate measurement | 147 versus 53 | 34.69 | 54.71 | 0.44 (0.23-0.83) | 0.01 |

| 2. Sending blood cultures before antibiotics | 40 versus 160 | 40 | 40 | 1.0 (0.49-2.02) | 1.00 |

| 3. Broad-spectrum antibiotics | 181 versus 19 | 40.88 | 31.57 | 1.5 (0.545-4.12) | 0.431 |

| 4. Fluids bolus administration | 15 versus 29 | 13.33 | 82.75 | 0.03 (0.005-0.19) | 0.0001 |

| 5. CVP >8 mm Hg | 9 versus 35 | 11.11 | 71.42 | 0.05 (0.06-0.45) | 0.001 |

| 6. Optimization of Scvo2 >70% | 3 versus 41 | 0 | 63.41 | - | 0.031 |

| 7. Composite bundle completed | 19 versus 181 | 15.79 | 42.54 | 0.25 (0.07-0.9) | 0.024 |

CVP: Central venous pressure, Scvo2: Central venous oxygen saturation

In another subgroup analysis of mortality among 38 patients with hyperlactatemia (serum lactate >4 mmol/L), out of the 18 patients who received fluid bolus 72.22% (13/18) patients survived; while among not receiving fluid bolus, 35% (7/20) survived (P = 0.02).

There was no significant difference in mean hospital stay (12.5 days at baseline, 14.2 days at QI 3, P for trend = 0.24) or mean ICU stay (4.3 days at baseline, 4.5 days at QI 3, P for trend = 0.69) during the study.

DISCUSSION

The study represents in-depth document evaluation of SSC guideline compliance in patients of severe sepsis (now termed “sepsis” after the Sepsis-3 definition) and septic shock before and after the resident training. The study shows that the mortality of North Indian patients with severe sepsis/septic shock is high (50%). Simultaneously, compliance with the composite components of 6 h-sepsis resuscitation bundle is very low (0%). Both mortality and compliance (at individual component level and composite level) improve significantly after repeated clinicians' education/training. Mortality peaks 0.25 odds in patients of completed all components of the bundle compared to those incomplete one. Among individual components, measurement of serum lactate, provision of fluid bolus, and optimization of CVP and ScvO2 were independently associated with the mortality benefit in their completion. At last, the study affirms that the SSC guideline is yet to be implemented in a limited resource setting hospital. Furthermore, our study shows that a focused, brief, and repeated educational training with feedback assessment are effective and feasible for significant improvement of the guideline compliant SSC in a hospital/medical institution.

The whole idea of sepsis resuscitation bundle is that the time-bound implementation of the bundle components, which has become the standard of care in the management of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock, would translate into better outcomes in term of the mortality and hospital stay. A study conducted by HB Nguyen et al. reveals the compliance with the composite bundle at the baseline is 0% similar to our study and 6.8% by MOSAICS Asian study.[10,12] If we see individual bundle component at baseline, then also, there is <50% compliance rate except for two components (i.e., measurement of serum lactate and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics). Moreover, in detail document evaluations, we get more irony facts. The measurement of serum lactate is not with the intention to treat the patients with fluid bolus. This is evident from the fact that out of seven patients who merit fluid bolus based on serum lactate levels none have received the fluid bolus. All patients go on to develop hypotension subsequently. Hence, the value of serum lactate would have come as part of routine arterial blood gas measurement from the automated analyzer. Furthermore, 88.88% of patients receive antibiotics in the 1st h; however, only 4.44% of patients have been sent the blood cultures before the antibiotic administration. These again show poor baseline compliance to the guideline.

A steady improvement in the compliance with the individual component as well as the composite sepsis bundle is being observed throughout the study period except ScvO2 in the QI 1 where it is 0% similar to the baseline. Inserting a central venous line and measuring CVP and ScvO2 are time-consuming processes. Hence for resource limited settings like India, due to lack of sufficient doctors, it is very difficult to do these procedures in a time bound manner. However, repeated training increases these compliances too. Similar to our study, another study reveals the baseline compliance of 6%, which increase to 21.1% after repeated training over the 3-year study period.[13] Furthermore, these invasive procedures may not be required if we can use noninvasive hemodynamic maneuvers to re-assess the patient as evidenced by the recent guideline [Table 4; comparing old with recent guideline for 3 and 6-h sepsis bundle].[14]

Table 4.

Comparison of surviving sepsis campaign performance improvement indicators/bundles (2012 vs. 2016)

| Sepsis bundle 2012 guideline | Sepsis bundle 2016 guideline |

|---|---|

| Severe sepsis 3-h resuscitation bundle 1. Measure lactate level 2. Obtain blood cultures prior to administration of antibiotics 3. Administer broad spectrum antibiotics 4. Administer 30 mL/kg crystalloid for hypotension or lactate ≥4 mmol/L |

Severe sepsis 3-h resuscitation bundle Same as previous guideline |

| 6-h septic shock bundle 5. Apply vasopressors (for hypotension that does not respond to initial fluid resuscitation to maintain a MAP ≥65 mmHg) 6. In the event of persistent arterial hypotension despite volume resuscitation (septic shock) or Initial lactate ≥4 mmol/L (36 mg/dl)Measure CVPMeasure ScvO2 7. Remeasure lactate if initial lactate was elevated |

6-h septic shock bundle 5. Apply vasopressors (for hypotension that does not respond to initial fluid resuscitation) to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥65mmHg 6. In the event of persistent hypotension after initial fluid administration (MAP< 65 mm Hg) or if initial lactate was ≥4 mmol/L, re-assess volume status and tissue perfusion and document findings according to below Table. Document reassessment of volume status and tissue perfusion with Either Repeat focused exam (after initial fluid resuscitation) including vital signs, cardiopulmonary, capillary refill, pulse, and skin findings Or two of the following Measure CVP Measure ScvO2 Perform bedside cardiovascular ultrasound Perform dynamic assessment of fluid responsiveness with passive leg raise or fluid challenge 7. Re-measure lactate if initial lactate elevated |

SSC: Surviving sepsis campaign, MAP: Mean arterial pressure, CVP: Central venous pressure, ScvO2: Central venous oxygen saturation

Several studies highlight the fact that the mortality benefit increases as the number of completed bundle components increase and also with the implementation of the whole bundle.[13,15,16] Another study has shown that the noncompliance with the 6 h-sepsis bundle is associated with a more than two-fold increase in the hospital mortality.[17] Many other studies have shown the mortality benefit with early antibiotic administration.[17,18] However, in the present study, baseline compliance with administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics is very high (90%) and remain stable in a higher level throughout the study. This makes other bundle components more important mortality predictors. Hyperlactatemia is one of the most important markers of tissue hypoperfusion and lactate clearance is independently associated with a decreased mortality having OR of 0.47 (CI 0.23–0.96) similar to the present study.[12] Mean hospital stay and mean ICU stay are well known to be less with successful implementation of sepsis resuscitation bundle.[9,19,20] However, this study does not show the benefit that may be due to small sample size and lack of ICU facility for all patients due to the resource limitations. These resource limitations may also contribute toward less improvement in both the compliance and survival as compared to other study in the developed countries.

For a successful education/training program, it should be convenient, relevant, focused, and delivered to the target population. We have targeted the relevant population, resident physicians, those most likely to respond during initial critical moments of patients' admission to the hospital and they document the progress notes (patient file) at the end. Henceforth, this fact reinforces the strength of the study design and relevance to the education.

The study location is a referral hospital. Therefore, it is difficult to generalize the findings in the whole country where primary care delivering hospitals are much more. This is done in the Emergency and Internal Medicine departments; whereas, other departments' inclusion would have increased more generalization of the results and more patient population. Nevertheless, it would have caused more variations in the training programs' understandings and results. It has maintained a high value in the study category because of high external validity.

This study has limitations despite being done in an institute of excellence in the resource-limited country. First, it has a small sample size. A larger study population may show a more significant change in hospital mortality and hospital/ICU length of stay. Second, the study is a nonrandomized one, hence, compliance with sepsis resuscitation bundle are only associated with the mortality benefit and not causal. Randomization is not possible here because of ethical constraints as SSC is the current standard of care. Third, even with a well-organized study, the absolute increase in the whole bundle compliance is 18%, implying the presence of many contributing factors. The study does not measure these barriers. Identifying and rectifying these variables may lead to the higher compliance in further studies. Fourth, retention of training by the residents has not been assessed including their effects on the compliance. During the study, new batches of residents have also entered to the intervention group that may have caused heterogeneity in effects of the training. However, this may affect inter QI phases compliance variations, but not the pre- and post-intervention compliance rate. Fifth, quality of delivered care in different locations of the hospital (e.g., ward vs. ICU) may confound the study by variations in both the patient care and documentation in case files. Finally, the education program of the study is limited to the residents while other staffs (e.g., nurses) are also an integral part of the patient management team. However, this exclusion increases internal validity but compromising external validity. For a more precise study, all these factors have to be clearly defined and taken care.

CONCLUSIONS

The QI interventional study in patients with sepsis establishes the lack of acceptance to the prevailing SSC guideline despite more than a decade of the publication. It has shown a significant improvement in the compliance to the implementation of the guideline, especially 6 h-sepsis bundle, both at individual component level and at composite level, after residents' repeated training. It also shows a strong trend toward the reduction in the hospital mortality after adopting the guideline. Among components of the bundle, administration of fluid bolus in patients with hypotension and hyperlactatemia is of utmost importance. Special attention is needed for achieving CVP- and ScVO2-related compliances of the sepsis bundle are the hardest to improve through these invasive maneuvers are rarely advised in the recent guideline. In future, with identification and rectification of barriers to the bundle completion, the compliance with sepsis resuscitation bundle can be further improved.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M, Hwang T, Davis CS, Wenzel RP. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).A prospective study. JAMA. 1995;273:117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houck PM, Bratzler DW, Nsa W, Ma A, Bartlett JG. Timing of antibiotic administration and outcomes for medicare patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:637–44. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:17–60. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0934-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:165–228. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304–77. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damiani E, Donati A, Serafini G, Rinaldi L, Adrario E, Pelaia P, et al. Effect of performance improvement programs on compliance with sepsis bundles and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamberlain DJ, Willis EM, Bersten AB. The severe sepsis bundles as processes of care: A meta-analysis. Aust Crit Care. 2011;24:229–43. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrer R, Artigas A, Levy MM, Blanco J, González-Díaz G, Garnacho-Montero J, et al. Improvement in process of care and outcome after a multicenter severe sepsis educational program in Spain. JAMA. 2008;299:2294–303. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.19.2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phua J, Koh Y, Du B, Tang YQ, Divatia JV, Tan CC, et al. Management of severe sepsis in patients admitted to Asian Intensive Care Units: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d3245. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Divatia J. Management of sepsis in Indian ICUs: Indian data from the MOSAICS study. Crit Care. 2012;16(Suppl 3):P90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen HB, Corbett SW, Steele R, Banta J, Clark RT, Hayes SR, et al. Implementation of a bundle of quality indicators for the early management of severe sepsis and septic shock is associated with decreased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1105–12. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259463.33848.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiramizo SC, Marra AR, Durão MS, Paes ÂT, Edmond MB, Pavão dos Santos OF. Decreasing mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock patients by implementing a sepsis bundle in a hospital setting. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 03]. Available from: http://www.survivingsepsis.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/SSC-Statements-Sepsis-Definitions-3-2016.pdf .

- 15.Castellanos-Ortega A, Suberviola B, García-Astudillo LA, Holanda MS, Ortiz F, Llorca J, et al. Impact of the surviving sepsis campaign protocols on hospital length of stay and mortality in septic shock patients: Results of a three-year follow-up quasi-experimental study. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1036–43. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d455b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zambon M, Ceola M, Almeida-de-Castro R, Gullo A, Vincent JL. Implementation of the surviving sepsis campaign guidelines for severe sepsis and septic shock: We could go faster. J Crit Care. 2008;23:455–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao F, Melody T, Daniels DF, Giles S, Fox S. The impact of compliance with 6-hour and 24-hour sepsis bundles on hospital mortality in patients with severe sepsis: A prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2005;9:R764–70. doi: 10.1186/cc3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barochia AV, Cui X, Vitberg D, Suffredini AF, O'Grady NP, Banks SM, et al. Bundled care for septic shock: An analysis of clinical trials. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:668–78. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb0ddf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeon K, Shin TG, Sim MS, Suh GY, Lim SY, Song HG, et al. Improvements in compliance with resuscitation bundles and achievement of end points after an educational program on the management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Shock. 2012;37:463–7. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31824c31d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Memon JI, Rehmani RS, Alaithan AM, El Gammal A, Lone TM, Ghorab K, et al. Impact of 6-hour sepsis resuscitation bundle compliance on hospital mortality in a Saudi hospital. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:273268. doi: 10.1155/2012/273268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]