Abstract

The prominence of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in human physiology and disease has resulted in their intense study in various fields of research ranging from neuroscience to structural biology. With over 800 members in the human genome and their involvement in a myriad of diseases, GPCRs are the single largest family of drug targets, and an ever-present interest exists in further drug discovery and structural characterization efforts. However, low GPCR expression and stability outside the natural lipid environments have challenged these efforts. In vivo functional studies of GPCR signaling are complicated not only by the need for specific spatiotemporal activation, but also by downstream effector promiscuity. In this review, we summarize the present and emerging GPCR engineering methods that have been employed to overcome the challenges involved in receptor characterization, and to better understand the functional role of these receptors.

Introduction

G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) constitute the largest family of signaling membrane receptors. They are involved in a wide diversity of cellular and physiological processes, including immune responses, vision, neuronal communication and behavior(1). GPCRs are also associated with severe diseases and represent the target of close to 40% of marketed drugs (2). GPCRs function as sophisticated allosteric machines. They respond to diverse extracellular stimuli in the form of light, small molecules, peptides, lipids and proteins by transmitting the signal across the membrane and activating a number of intracellular signaling pathways (3). High conformational flexibility is a hallmark of GPCRs which allow them to sense diverse stimuli and couple to different signaling pathways (4), but represents a challenge for structure characterization which often require conformationally stable proteins. Hence, initial GPCR engineering efforts have focused on developing approaches to identify thermostabilized receptor variants for accelerating X-ray structure determination and rational drug design (Fig. 1). In parallel, methods have also been established to create GPCR variants that can be controlled by external cues for better studying cellular signaling. Lastly, computational approaches have recently emerged to rationally design GPCR functions, and pave the road for the design of novel biosensors that should prove useful in cell engineering applications (Fig. 1). Below, we first describe empirical, experimentally-driven approaches and then outline recent computational techniques for engineering GPCR structure and function.

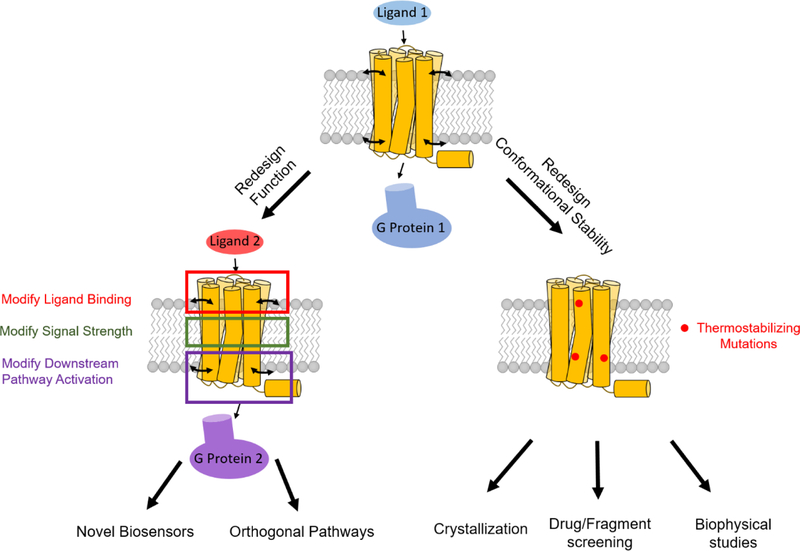

Figure 1. Potential applications of GPCR engineering.

A wildtype receptor (top) can be engineered to: Left, create novel receptor functions to respond to different ligands, to transmit ligand-induced signals with different strengths, or to activate a novel effector protein. Right, another route is to modify the wildtype receptor’s stability in either the active or inactive state, to generate receptors with higher thermostabilities, which then can be used in other applications. Small curved arrows on GPCRs represent conformational flexibility. Note its absence on the thermostabilized receptor.

1. Empirical experimentally-driven design of GPCRs

Over the years, a number of experimental approaches have been developed to create GPCR variants for facilitating structural and functional studies. A first line of investigations has focused on modifying and stabilizing receptors to make them more amenable to structural determination and biophysical studies, including drug discovery efforts. A second line of approaches aimed at better understanding the role of GPCRs in neuronal, cellular signaling, and behavior. In each case, the methods similarly involved random or systematic mutagenesis, or a grafting approach to reach the desired molecular properties. The methods used are described below, and highlighted in Figure 2.

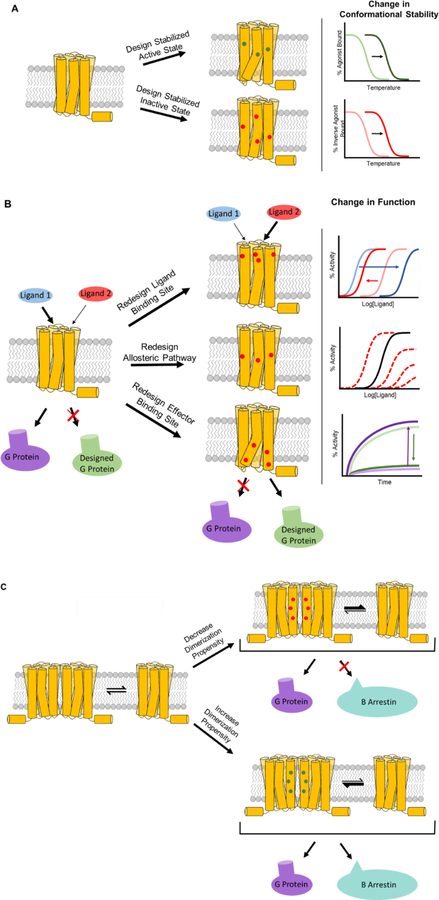

Figure 2. Summary of GPCR engineering experimental methods.

From the top going clockwise, the methods are: thermostabilization via alanine scanning mutagenesis, stabilization by replacing intracellular loop 3 (ICL3) with an easily crystallizable soluble protein, using a nanobody or full or partial G protein, directed evolution of receptor through multiple mutagenesis and selection cycles, creation of GPCR-cleavage site-transcription factor/Crispr-dCas9 fusion and arrestin-protease fusion, and the replacement of ICLs of a photosensitive receptor with that of another receptor. Blue background indicates methods used to facilitate crystallization. Green background indicates the methods are used in pathway determination and neuroscience application. Note the blue-green background for directed evolution, which has been used in both applications.

1.1. Structural characterization

Up until 2007, the only GPCR with a solved three-dimensional structure was rhodopsin (5, 6). Due to the low endogenous expression of GPCRs and their inherent instability outside biological membranes, new techniques were necessary to enable their crystallization. Today, over 50 unique GPCRs (7) have been crystallized, thanks to, in no small part, to various GPCR engineering methods. Successful receptor stabilization could be achieved by conformationally stabilizing the flexible intracellular loop 3 (ICL3) by antibody fragments recognizing the receptor, or by replacing the ICL3 entirely with different soluble proteins promoting crystal packing such as T4L or BRIL. Conformational thermostabilization was also achieved via scanning mutagenesis, although in many cases a combination of ICL3 insertion and mutagenesis were used (8, 9). Systematic mutagenesis work has been carried out, demonstrating the thermostabilization of receptors by mainly replacing leucines to alanines and alanines to leucines (though other mutations also work), which locked the receptor into a specific conformation, so-called Stabilized Receptors (StaRs) (10). This technique has proven successful in the generation of antagonist, partial agonist, and agonist-bound structures (11–13).

Various directed evolution techniques such as CHESS (14) and SaBRE (15)•• have also been applied to GPCRs to screen and select for stabilizing mutations. These techniques rely on the detection of highly expressed mutants using fluorescently labeled ligands and flow cytometry. The increase in expression and ligand binding is thought to be linked to increase in properly folded receptors and increased thermostability(16). Given the time and effort required to find suitable thermostabilizing mutations and the low success rate of scanning mutagenesis, directed evolution offers a faster route to a more thermostable receptor. Typically, the process to discovering suitable mutations has a hit rate of less than 10% and hundreds of mutations are tested. In contrast, 2 to 3 rounds of CHESS can result in a thermostable receptor with a significantly higher level of expression than the wildtype receptor.

1.2. Biophysical studies

Although surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) are commonly used techniques in drug discovery, their application to GPCRs has been limited due to receptor instability and low expression (13)•. There has been some success in applying these methods to the wild-type B2 receptor (17), however the generation of StaRs provides a solution to this obstacle. Unlike wild-type receptors, StaRs exhibit wild-type-like binding affinity only to the class of drug (inverse agonist, antagonist or agonist) which was used during StaR generation, due to conformational selection, with a reduced affinity for other classes. While this may bias drug discovery efforts towards a certain drug class, it may also provide a valuable method in the discrimination between agonist and antagonist hits during screening.

1.3. Neuronal Signaling

Engineered GPCRs have been used extensively in optogenetic and chemogenetic applications in neuroscience. The Opto-XR class of engineered GPCRs are chimeric receptors, engineered by grafting the intracellular region of the receptor of interest onto the light-sensitive transmembrane region of rhodopsin. These light-sensitive receptors have been extensively used to study the spatiotemporal effects of receptor activation, and the subsequent behavioral changes elicited by receptor activation. The newest member of this chimeric family, Opto-MOR (18), a rhodopsin-mu opioid receptor chimera, has been shown to recapture the signaling properties of the endogenous mu opioid receptor upon light activation. This new chimera has allowed Suida and colleagues to study receptor activation in mouse models. Another prevalent tool in neuroscience are Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs). While Opto-XR design relies on a grafting design method, DREADDs are generated by multiple rounds of directed evolution, to select for mutant receptors that are activated by a normally inert small molecule, while losing the ability to be activated by the endogenous ligand. Initial DREADDs were based on the human muscarinic receptors, which were evolved and selected to bind and be activated by clozapine-N-oxide (CNO). Different DREADDs have been developed to signal through each major downstream effector, including Gq, Gi, Gs and beta-arrestin. There are excellent reviews comparing the two technologies (19, 20)•.

1.4. Signaling assays

Other GPCR engineering techniques include the Tango system, which relies on a GPCR-TEV cleavage site-transcription factor fusion protein in conjunction with a beta-arrestin-TEV protease fusion (21); and a recently developed variety of this system using a CRISPR dCas9 in lieu of a transcription factor, capable of multiplex signaling (22). Kroeze et al. used the Tango system to develop PRESTO-Tango, a high throughput cell-based assay to detect drug activation of the GPCRome (23)••. Given the importance of biased signaling in cellular functions and its implication in disease, these techniques constitute an important step toward the discovery of biased ligands.

1.5. Limitations of experimental methods

While the outlined methods have proven their utility and have provided valuable insights, they suffer from numerous weaknesses. As previously mentioned, scanning mutagenesis for the purposes of thermostabilization usually requires the testing of hundreds of mutants, has a hit rate of roughly 10%, and takes months of experimental investigations (10). Furthermore, these receptors tend to lose their signaling functions. Directed evolution is a possible alternative approach but are currently limited to selection in bacteria or yeast systems, thus preventing the selection for functional signaling properties in situ (i.e. in mammalian cells). Additionally, since known ligands, and their radiolabeled or fluorescently labeled analogs, are mandatory for selection, orphan GPCRs are excluded from such approaches. Opto-XRs, consisting of rhodopsin transmembrane helices and a target receptor’s ICLs, lose the dimerization or oligomerization propensity and selectivity of the target receptor that depend on specific transmembrane helix associations. Therefore, the chimeric receptor may not recapitulate the interactome profile (e.g. homo and hetero oligomerization (24–26)) and associated cellular functions of the target receptor (27). DREADDs present their own limitation: directed evolution methods have only resulted in receptors with CNO as their inert ligand. The latest DREADD based on the kappa opioid receptor (KOR) were engineered through structure-based rational design approaches, with a new agonist, Salvinorin B (28). Nonetheless, with only two possible physiologically inert compounds as possible ligands, the usefulness of DREADDs is still limited, especially in applications where a multiplexed approach or sensing native ligands is necessary. As computational design has been used for the creation of KOR, it can offer solutions for biosensors, thermostabilizing receptors, generating orthogonal pathways, and even for fine-tuning receptor sensitivity (see sections below).

2. Computational design of GPCR structure and function

Computational design approaches have proven quite useful for engineering soluble protein fold, stability, binding and catalysis. Recent successes on membrane proteins include the design of a Zinc transporter (29) and symmetric transmembrane helical (TMH) oligomers (30). However, key principles underlying the structure and function of naturally-evolved multipass membrane receptors such as GPCRs were not recapitulated in these designs. Receptors rapidly switch between conformations and transmit long-range signals across the membrane. Such complex functions rely on protein sequences that can intrinsically adopt multiple conformations and shift between these conformations upon ligand, lipid or protein binding. We outline below recent progresses toward the development and application of computational approaches reprograming GPCR structure and function.

2.1. Designing GPCRs with enhanced conformational stability

Protein stabilization has been one of the hallmarks of computational protein design. The first computational design method developed for stabilizing multi-pass membrane proteins identified metastable sites in GPCR structures through sequence conservation and measures of suboptimal polar interactions and protein packing defects. Then, the method automatically selected amino-acid substitutions at these sites that enhance protein contacts and conformational stability (31, 32). The approach initially validated on the beta1 adrenergic receptor (B1AR) achieved more than 80% success rate, generated higher thermostabilization than empirical screening approaches and predicted correctly many experimentally selected thermostabilized variants of the adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR) and B1AR (Fig. 3a). A similar approach combining in silico mutagenesis screening, sequence conservation and machine learning algorithms trained on known GPCR mutations has also been used recently to thermostabilize the 5HT2c receptor (33). In silico design calculations rely however on high-resolution structural information which is lacking for a large majority of GPCRs. To be useful for structural and biophysical characterization, computational design and protein structure prediction techniques were combined. Homology modeling can generate reliable structural models of a target GPCR, providing GPCR structures with sufficient homology (i.e. >25% sequence identity in the TMH region) are available (32, 34). Using models generated from the B2AR-Gs ternary active state structure, dopamine D2 and A2AR variants were designed with enhanced active state stability, agonist binding and constitutive activity (35). One designed agonist-bound A2AR crystallized in a close to fully active conformation, despite the absence of G-protein Gs (Lai et al., unpublished results). By contrast, A2AR variants previously thermostabilized through mutagenesis screening remained in a partially active conformation and lost their ability to couple to G-proteins and signal (36). These results suggest that computational design approaches can stabilize GPCR conformations without disrupting ligand binding, G-protein coupling or allosteric signal transduction receptor functions. Hence, these methods should prove useful for accelerating the characterization of receptor structures and their interactions with pharmacologically important, weak or partial agonists which lack the potency required for structure determination.

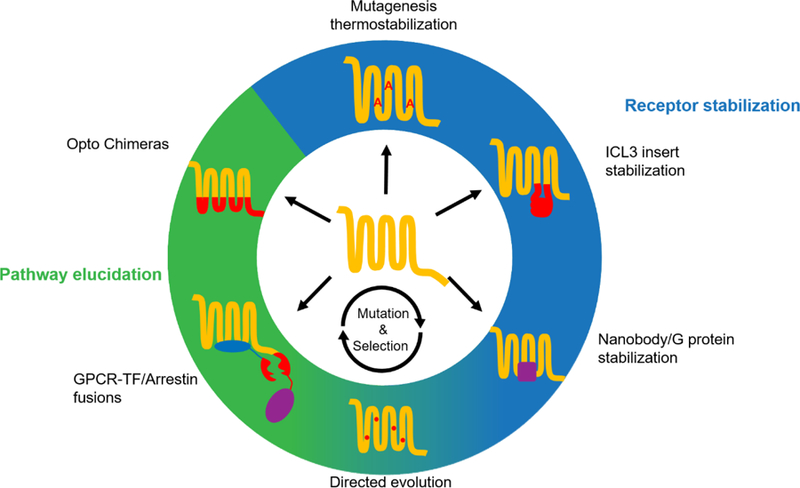

Figure 3. Summary of the different GPCR properties that can be reprogrammed with computational methods.

A. The stabilities of the active and inactive states of the receptor can be modified independently, to produce receptors that exhibit higher melting temperatures when bound to selective ligands (right). B. The wildtype receptor and its upstream and downstream interacting partners (left), and designed receptors with novel functions (right). A modified ligand binding region (top right), transmembrane helical region (center right), and effector binding region can be designed independently, or in combination. The modified functional output for each novel design is depicted in the form of dose response assays (top and center right) or as an activity assay for effector binding (bottom). C. The population of receptors present in monomeric or oligomeric states can also be modified (wildtype on left, design on right) by redesigning the interface between the monomers. A weakened interface for the CXCR4 receptor results in decreased recruitment of Beta arrestin.

2.2. Toward the computational design of GPCR biosensors

GPCRs have evolved to recognize, sense and respond to a wide diversity of small molecule, peptide, lipid and protein stimuli. These unique properties suggest that the GPCR structure fold constitutes a versatile platform for developing novel biosensors. In recent years, computational design techniques have been developed to manipulate and reprogram ligand binding, allosteric transmission and coupling to intracellular signaling proteins with the goal of designing GPCRs with novel functions.

2.2.1. Designing GPCRs with reprogrammed ligand binding selectivity

In contrast to DREADDs, which are stimulated by inactive drug compounds, GPCRs designed with fine-tuned ability to sense natural ligands should prove useful for studying and rewiring ligand-induced cellular signaling pathways. Due to the receptor’s high intrinsic conformational flexibility, accurately predicting GPCR-ligand interactions and conformations has remained a challenge especially for receptors without solved structures. By integrating receptor homology modeling, ligand docking, and computational design techniques, Feng and colleagues have developed the software IPHoLD, for modeling and designing GPCR-ligand interactions (34)••. Unlike alternative techniques, IPHoLD recapitulated ligand-induced fit effects on receptor conformations and predicted receptor ligand binding selectivity. Functional dopamine D2 variants with novel ligand binding selectivity profiles were successfully engineered using the method (Fig. 3b). In principle, the method could be expanded to model and design GPCR interactions with peptide, lipid and even proteins.

2.2.2. Designing GPCRs with reprogrammed allosteric signal transduction properties

Extracellular signals triggered by ligand binding are propagated on the other side of the membrane through allosteric communication pathways encoded by networks of highly coupled receptor residues. Residue coupling across long-distance enables efficient transmission of changes in protein structures and dynamics which occur upon ligand binding and can be inferred from correlated movements observed in Molecular Dynamics simulations (37). Mutations known to affect ligand responses and receptor activation often clustered around the allosteric pathways predicted by conformational dynamics (37). Keri and colleagues developed a method to rationally engineer GPCRs with altered ligand-induced signaling responses by designing amino-acid microswitches that rewire predicted allosteric pathways (Keri unpublished results, (38)). When applied to the dopamine D2 receptor, designed variants displayed either enhanced or decreased G-protein activation responses to agonists which were largely consistent with the predicted responses (Fig. 3b). Gain of function mutations switched the D2 receptor from a dopamine to a highly sensitive dopamine and serotonin biosensor. Residue functional coupling can also be inferred albeit more indirectly from sequence covariation analysis (39). By swapping co-evolving residues between a pair of GPCRs, Sung et al. were able to modulate receptor ligand responses (40)•. Since GPCRs can trigger distinct signaling pathways upon different ligand stimuli through a mechanism called biased agonism, current efforts involve the identification and manipulation of functionally selective allosteric pathways (41, 42)•. Such approaches should enable the design of highly pathway selective biosensors and prove particularly useful in synthetic cell engineering approaches that rely on well-isolated and controllable cellular functions.

2.2.3. Designing GPCRs with reprogrammed signaling output properties

Another avenue to bias or even rewire GPCR-triggered cellular functions consist in designing the binding interactions between the receptor and its downstream transducers, G-proteins and beta-arrestin. The increasing number of GPCR structures bound to Gs, Gi and beta-arrestin uncovered the high conformational diversity of the GPCR-downstream effector binding interfaces and revealed why predicting GPCR-effector recognition from sequence remains a daunting challenge (43). Capitalizing on existing GPCR-effector structures, Young et al. have developed a method to model by homology and design GPCR-G-protein interactions. Using the approach, they created novel orthogonal dopamine D2-Gi pairs that signal with high selectivity (44)•. Unlike the promiscuous D2 WT, the D2 variants did not couple to Gq or beta-arrestin and the Gi variants were solely activated by the designed cognate D2 receptors (Fig. 3b). Taking advantage of the modular architecture of G-proteins which mainly engage the GPCRs through their C-terminal helix 5, Bourne and colleagues showed that GPCRs can be redirected to activate non-native G-proteins and pathways by swapping a few residues of the non-native G-protein helix 5 to those of the native transducer that optimally couple to the GPCR (45). Young et al. further extended that approach and designed orthogonal Gs-i chimeric proteins that enabled D2 receptors to trigger activating Gs-mediated instead of the inhibitory Gi-mediated cellular functions upon dopamine stimulus.

Altogether, the above-mentioned computational approaches pave the road for designing novel GPCR-based biosensors and highly selective cellular signaling pathways.

2.3. Computational design of GPCR oligomerization

GPCRs can either self-associate or hetero-associate with related GPCRs resulting in multiple combinations of functional units with potentially distinct signaling properties (46, 47). Feng and colleagues have developed a computational approach to model, dock GPCRs and design novel GPCR associations (Feng et al., unpublished results). They applied the technique to modulate the self-association propensity of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 which is known to form constitutive homodimers and higher order oligomers. CXCR4 variants with enhanced or weakened dimerization propensities were designed and displayed changes in dimerization measured by BRET which were consistent with the predictions. Interestingly, all the designs could efficiently activate Gi while those with weakened dimerization propensity were largely impaired in their ability to engage beta-arrestins (Fig. 3c). The study revealed an unforeseen role of GPCR associations in regulating the receptor signaling selectivity and paves the road for engineering GPCR associations with fine-tuned functions.

2.4. Limitations of the computational techniques

The accuracy of GPCR structural models remains the main limitation of current computational techniques which require substantial structural information from not too distant homologs. Current successes have been limited to the design of small ligand-GPCR interactions and additional development will be needed to accurately model peptide, lipid and protein binding to receptors. Lastly, to achieve high computational efficiency, design calculations have often been performed using implicit models of the lipid membrane which neglect the molecular details of solvent and lipid molecules that are known to play important roles in regulating GPCR structure and function. As recently demonstrated by Lai et al. with a hybrid solvation model developed for membrane proteins (48)•, further developments will have to find appropriate tradeoffs between accurate representation of the lipid environment and calculation efficiency.

Conclusions

The GPCR engineering field has witnessed a rich spectrum of technological developments for reprogramming the structural and functional properties of this large class of receptors. As often, empirical and computational methods have advanced in parallel and complement each other. As major advances in cryo-electron microscopy now enable the routine structure determination of GPCRs in different functional states (49–52), the GPCR engineering field will likely move from a focus on structural stabilization towards accelerating drug discovery and designing new functions. The years to come promise to be an exciting time for GPCR engineering.

Highlights.

Stabilized GPCRs accelerate structural studies and drug discovery

Chimeric GPCRs provide spatiotemporal control of cellular signaling

GPCR functions can be reprogrammed to create novel biosensors

GPCR oligomerization can be modulated by computational design

Marrying computations and experiments will further benefit GPCR studies

Acknowledgements

D.K. and P.B. are supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health (1R01GM097207) and by funding from EPFL and the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

P.B and D.K. declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SGF, Kobilka BK. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature 2009;459(7245):356–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manglik A, Lin H, Aryal DK, McCorvy JD, Dengler D, Corder G, et al. Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature 2016;537(7619):185–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohlhoff KJ, Shukla D, Lawrenz M, Bowman GR, Konerding DE, Belov D, et al. Cloud-based simulations on Google Exacycle reveal ligand modulation of GPCR activation pathways. Nature Chemistry 2014;6(1):15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nygaard R, Zou YZ, Dror RO, Mildorf TJ, Arlow DH, Manglik A, et al. The Dynamic Process of beta(2)-Adrenergic Receptor Activation. Cell 2013;152(3):532–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmussen SG, Choi HJ, Rosenbaum DM, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Edwards PC, et al. Crystal structure of the human beta2 adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 2007;450(7168):383–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science 2000;289(5480):739–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandy-Szekeres G, Munk C, Tsonkov TM, Mordalski S, Harpsoe K, Hauser AS, et al. GPCRdb in 2018: adding GPCR structure models and ligands. Nucleic Acids Research 2018;46(D1):D440–D6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thal DM, Vuckovic Z, Draper-Joyce CJ, Liang YL, Glukhova A, Christopoulos A, et al. Recent advances in the determination of G protein-coupled receptor structures. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2018;51:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh E, Kumari P, Jaiman D, Shukla AK. Methodological advances: the unsung heroes of the GPCR structural revolution. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2015;16(2):69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magnani F, Serrano-Vega MJ, Shibata Y, Abdul-Hussein S, Lebon G, Miller-Gallacher J, et al. A mutagenesis and screening strategy to generate optimally thermostabilized membrane proteins for structural studies. Nat Protoc 2016;11(8):1554–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S, Che T, Levit A, Shoichet BK, Wacker D, Roth BL. Structure of the D2 dopamine receptor bound to the atypical antipsychotic drug risperidone. Nature 2018;555(7695):269–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jazayeri A, Rappas M, Brown AJH, Kean J, Errey JC, Robertson NJ, et al. Crystal structure of the GLP-1 receptor bound to a peptide agonist. Nature 2017;546(7657):254–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews SP, Brown GA, Christopher JA. Structure-based and fragment-based GPCR drug discovery. ChemMedChem 2014;9(2):256–75.• Here, Andrews et al review the establishment of the StaR technology and summarize the receptor structures for which it was used.

- 14.Scott DJ, Kummer L, Egloff P, Bathgate RAD, Pluckthun A. Improving the apo-tate detergent stability of NTS1 with CHESS for pharmacological and structural studies. Bba-Biomembranes 2014;1838(11):2817–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schutz M, Schoppe J, Sedlak E, Hillenbrand M, Nagy-Davidescu G, Ehrenmann J, et al. Directed evolution of G protein-coupled receptors in yeast for higher functional production in eukaryotic expression hosts. Sci Rep-Uk 2016;6.•• Schutz et al. establish SaBRE, a directed evolution method to generate highly expressed, thermostable receptors in yeast. They demonstrate the usefulness of the technique on the NTR1, NK1R, and KOR1 receptors.

- 16.Vaidehi N, Grisshammer R, Tate CG. How Can Mutations Thermostabilize G-Protein-Coupled Receptors? Trends Pharmacol Sci 2016;37(1):37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aristotelous T, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Gawron S, Sassano MF, Kahsai AW, et al. Discovery of beta 2 Adrenergic Receptor Ligands Using Biosensor Fragment Screening of Tagged Wild-Type Receptor. Acs Med Chem Lett 2013;4(10):1005–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siuda ER, Copits BA, Schmidt MJ, Baird MA, Al-Hasani R, Planer WJ, et al. Spatiotemporal Control of Opioid Signaling and Behavior. Neuron 2015;86(4):923–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spangler SM, Bruchas MR. Optogenetic approaches for dissecting neuromodulation and GPCR signaling in neural circuits. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2017;32:56–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth BL. DREADDs for Neuroscientists. Neuron 2016;89(4):683–94.• Roth reviews the DREADD technology in this article, the various DREADDs generated, how DREADDs are used and their potential for the future.

- 21.Barnea G, Strapps W, Herrada G, Berman Y, Ong J, Kloss B, et al. The genetic design of signaling cascades to record receptor activation. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105(1):64–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kipniss N, Dingal P, Abbott T, Gao Y, Wang H, Dominguez A, et al. Engineering cell sensing and responses using a GPCR-coupled CRISPR-Cas system. Nature Communications 2017;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroeze W, Sassano M, Huang X, Lansu K, McCorvy J, Giguere P, et al. PRESTO-Tango as an open-source resource for interrogation of the druggable human GPCRome. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2015;22(5):362–U28.•• Here, Kroeze et al. create PRESTO-Tango a high throughput methodology, based on the Tango-GPCRs, for drug discovery applications. Using this technology, they test an impressive array of GPCR and drug combinations to find new GPCR agonists.

- 24.Herrick-Davis K, Milligan G, Di Giovanni G. G-protein-coupled Receptor Dimers: Springer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farran B An update on the physiological and therapeutic relevance of GPCR oligomers. Pharmacol Res 2017;117:303–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sokolina K, Kittanakom S, Snider J, Kotlyar M, Maurice P, Gandia J, et al. Systematic protein-protein interaction mapping for clinically relevant human GPCRs. Mol Syst Biol 2017;13(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Munoz L, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Barroso R, Sorzano COS, Torreno-Pina JA, Santiago CA, et al. Separating Actin-Dependent Chemokine Receptor Nanoclustering from Dimerization Indicates a Role for Clustering in CXCR4 Signaling and Function. Mol Cell 2018;70(1):106–19 e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vardy E, Robinson JE, Li C, Olsen RHJ, DiBerto JF, Giguere PM, et al. A New DREADD Facilitates the Multiplexed Chemogenetic Interrogation of Behavior. Neuron 2015;86(4):936–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joh NH, Wang T, Bhate MP, Acharya R, Wu YB, Grabe M, et al. De novo design of a transmembrane Zn2+-transporting four-helix bundle. Science 2014;346(6216):1520–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu P, Min D, DiMaio F, Wei KY, Vahey MD, Boyken SE, et al. Accurate computational design of multipass transmembrane proteins. Science 2018;359(6379):1042–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen KY, Zhou F, Fryszczyn BG, Barth P. Naturally evolved G protein-coupled receptors adopt metastable conformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109(33):13284–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen KY, Sun J, Salvo JS, Baker D, Barth P. High-resolution modeling of transmembrane helical protein structures from distant homologues. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10(5):e1003636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng Y, McCorvy JD, Harpsoe K, Lansu K, Yuan S, Popov P, et al. 5-HT2C Receptor Structures Reveal the Structural Basis of GPCR Polypharmacology. Cell 2018;172(4):719–30 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng X, Ambia J, Chen KM, Young M, Barth P. Computational design of ligand-binding membrane receptors with high selectivity. Nat Chem Biol 2017;13(7):715–23•• Feng et al., describe an integrated homology modeling, ligand docking and protein design approach for modeling and redesigning the ligand binding selectivity of GPCRs even those without solved three-dimensional structures. The technique should prove useful for reprogramming the ligand binding properties of many structurally-uncharacterized GPCRs.

- 35.Barth P, Senes A. Toward high-resolution computational design of the structure and function of helical membrane proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2016;23(6):475–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magnani F, Shibata Y, Serrano-Vega MJ, Tate CG. Co-evolving stability and conformational homogeneity of the human adenosine A2a receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105(31):10744–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattacharya S, Vaidehi N. Differences in Allosteric Communication Pipelines in the Inactive and Active States of a GPCR. Biophysical Journal 2014;107(2):422–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arber C, Young M, Barth P. Reprogramming cellular functions with engineered membrane proteins. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2017;47:92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suel GM, Lockless SW, Wall MA, Ranganathan R. Evolutionarily conserved networks of residues mediate allosteric communication in proteins. Nat Struct Biol 2003;10(1):59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sung YM, Wilkins AD, Rodriguez GJ, Wensel TG, Lichtarge O. Intramolecular allosteric communication in dopamine D2 receptor revealed by evolutionary amino acid covariation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113(13):3539–44.• In this study, Sung et al., use a bioinformatic method based on sequence co-evolution through phylogenetic analysis to identify residue pairs that encode functional fitness difference between receptor homologs. They use the information to identify coupled protein sites transmitting responses to specific ligands.

- 41.Nivedha AK, Tautermann CS, Bhattacharya S, Lee S, Casarosa P, Kollak I, et al. Identifying Functional Hotspot Residues for Biased Ligand Design in G-Protein-Coupled Receptors. Mol Pharmacol 2018;93(4):288–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schonegge AM, Gallion J, Picard LP, Wilkins AD, Le Gouill C, Audet M, et al. Evolutionary action and structural basis of the allosteric switch controlling beta2AR functional selectivity. Nat Commun 2017;8(1):2169.• In this study, Schonegge et al., combined in silico evolutionary lineage analysis and site-directed mutagenesis with large-scale functional signaling characterization to identify molecular motifs that translate ligand binding into selective signaling GPCR responses.

- 43.Flock T, Hauser AS, Lund N, Gloriam DE, Balaji S, Babu MM. Selectivity determinants of GPCR-G-protein binding. Nature 2017;545(7654):317–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young M, Dahoun T, Sokrat B, Arber C, Chen KM, Bouvier M, et al. Computational design of orthogonal membrane receptor-effector switches for rewiring signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018• In this study, Young et al., combined homology modeling, protein docking and design techniques to engineer novel pairs of GPCR-G-proteins which couple with high selectivity and can rewire signaling pathways.

- 45.Conklin BR, Farfel Z, Lustig KD, Julius D, Bourne HR. Substitution of three amino acids switches receptor specificity of Gq alpha to that of Gi alpha. Nature 1993;363(6426):274–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomes I, Ayoub MA, Fujita W, Jaeger WC, Pfleger KDG, Devi LA. G Protein-Coupled Receptor Heteromers. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Vol 56 2016;56:403–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stephens B, Handel TM. Chemokine Receptor Oligomerization and Allostery. Oligomerization and Allosteric Modulation in G-Protein Coupled Receptors 2013;115:375–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lai JK, Ambia J, Wang Y, Barth P. Enhancing Structure Prediction and Design of Soluble and Membrane Proteins with Explicit Solvent-Protein Interactions. Structure 2017;25(11):1758–70.e8• In this study, Lai et al., describe a new hybrid energy function that accelerates the accurate modeling of protein-solvent molecule interactions. The technique enhances the atom-based homology modeling of GPCRs and should prove useful in GPCR design applications.

- 49.Koehl A, Hu H, Maeda S, Zhang Y, Qu Q, Paggi JM, et al. Structure of the micro-opioid receptor-Gi protein complex. Nature 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Kang Y, Kuybeda O, de Waal PW, Mukherjee S, Van Eps N, Dutka P, et al. Cryo-EM structure of human rhodopsin bound to an inhibitory G protein. Nature 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Garcia-Nafria J, Lee Y, Bai X, Carpenter B, Tate CG. Cryo-EM structure of the adenosine A2A receptor coupled to an engineered heterotrimeric G protein. Elife 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y, Sun B, Feng D, Hu H, Chu M, Qu Q, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the activated GLP-1 receptor in complex with a G protein. Nature 2017;546(7657):248–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]