Abstract

Background

The evidence supporting the benefit of femoral nerve block (FNB) for positioning before spinal anesthesia (SA) in patients suffering from a femur fracture remains inconclusive. In the present study, the authors intended to determine the efficacy and safety of FNB versus an intravenous analgesic (IVA) for positioning before SA in patients with a femur fracture.

Method

PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, and Scopus databases were searched up to January 2018. We included randomized controlled studies (RCTs) and observational studies that compared FNB versus IVA for the positioning of patients with femur fracture receiving SA. The primary outcome was pain scores during positioning within 30 min before SA. Secondary outcomes were the time for SA, additional analgesic requirements, anesthesiologist’s satisfaction with the quality of positioning for SA, participant acceptance, and hemodynamic changes. A random-effects model was used to synthesize the data. We registered the study at PROSPERO with an ID of CRD42018091450.

Results

Ten studies with 584 patients were eligible for inclusion. FNB achieved significantly lower pain scores than IVA during positioning within 30 min before SA (pooled standardized mean deviation (SMD): -1.27, 95% confidence interval (CI): -1.84 to -0.70, p < 0.05). A subgroup analysis showed that the analgesic effect was larger in patients in the sitting position for SA than a non-sitting position (sitting position vs non-sitting: pooled SMD: -1.75 (p < 0.05) vs -0.61 (not significant). A multivariate regression showed that the analgesic effect was also associated with age and the total equivalent amount as lidocaine after adjusting for gender (age: coefficient 0.048, p < 0.05; total equivalent amount as lidocaine: coefficient 0.005, p < 0.05). Patients receiving FNB also had a significantly shorter time for SA, greater anesthesiologist satisfaction, and higher patient acceptance than patients receiving IVA. The use of local anesthetics did not produce significant clinical hemodynamic change.

Conclusion

Compared to IVA, FNB was an effective and safe strategy for the positioning of femur fracture patients for a spinal block, particularly patients who received SA in the sitting position.

Introduction

Femoral fracture is a well-known reason for surgical repair in patients of all ages. Sex- and age-standardized incidences of femoral fracture for the UK, German, Netherlands, Danish, and Spanish databases vary from 9 to 52 per 10,000 person-years for the general population [1]. The incidence of femoral shaft fractures ranges from of 9.5 to 18.9 per 100,000 annually [2]. Approximately 250,000 proximal femur fractures occur in the United States annually. This number is anticipated to double by the year 2050 [3]. Approximately 98% of femur fractures are managed surgically [4]. Spinal anesthesia (SA) is the preferred and commonly used method for surgery, and it is associated with a lower odds of mortality compared to general anesthesia [5]. The main proposed reason for improved mortality included avoidance of intubation and mechanical ventilation, decreased blood loss, and improved postoperative analgesia [6]. SA must be administered in a lateral decubitus or sitting position. Movement of the overriding fractured end of the femur is inevitable, which causes excessive pain that makes positioning patients with a fractured femur for SA challenging.

Femoral fractures are a considerably painful bone injury because the periosteum exhibits the lowest pain threshold of all deep somatic structures [7]. Approximately one-third of patient with fractured hip have mild pain at rest, one-third have moderate pain and one-third have severe pain. But, over three-quarters of these patients have moderate to severe pain at movement [4]. The failure to effectively control the pain before surgery in femur fracture patients may lead to potential risks of cardiovascular events. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids are commonly used analgesics. However, these agents may cause undesirable side effects and complications [8]. Therefore, proper management of pain with the other choice is paramount.

Femoral nerve block (FNB) is a safe, simple and easy to learn. Local anesthetic is injected through the landmark method or under ultrasound guidance. A recent systematic review of eight trials with 373 participants showed that peripheral nerve block reduces pain on movement within 30 min of block placement more effectively than an intravenous analgesic (IVA) [9]. But heterogeneity is high, and most of these trials used a fascia iliaca nerve block (FINB) and do not specifically evaluate positioning for SA.

Increasing numbers of published studies compared FNB to IVA with femur fractures for positioning for SA [10–19]. But this evidence is not well-integrated. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to specifically assess the efficacy and safety of FNB versus IVA for positioning f SA in patients with a femur fracture in the operative setting.

Methods

Our meta-analysis followed the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (S1 PRISMA checklist) [20]. We registered the analysis at PROSPERO (PROSPERO ID: CRD42018091450).

Search strategy

Two authors (CWH and YPH) independently searched PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library and Scopus databases from the first record to January 2018 using eligibility criteria with the following search terms: femoral block, analgesic, spinal anesthesia, and fracture (S1 Table). No language restrictions were applied. We also identified other studies using the reference sections of relevant papers and correspondence with subject experts. We used the ClinicalTrials.gov registry (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) for unpublished studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all published human randomized control trials (RCTs) or observational studies with an adequate control group. Participants with a femur fracture who received FNB compared to IVA for positioning before a spinal block in an operative setting were included. Case reports, case series, and abstracts were excluded.

Outcomes of interest

Our primary outcome of interest was pain scores during positioning before SA. Secondary outcomes were the time for SA, additional analgesic requirements, anesthesiologist’s satisfaction with the quality of positioning for SA, participant acceptance, and hemodynamic changes.

Data extraction and management

Two reviewers (CWH and YPH) independently performed data extraction. Baseline and outcome data, including study design, characteristics of study population criteria for inclusion and exclusion, intervention method, post-treatment parameters, and complications, were extracted. A third reviewer (CC) resolved any discrepancies. We contacted the authors of the studies for additional information if required.

Assessment of risk of bias

Two reviewers (CHB and WCH) independently assessed the methodological quality. We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool for RCTs [21]. This tool includes six domains: adequacy of randomization, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, as well as reporting bias and other biases. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa scale tool for observational studies [22]. This tool has three domains, including selection of the cohort, comparability of the groups, and quality of the outcomes. The results were summarized in a risk of bias table. We resolved any disagreements on the methodological quality assessment through comprehensive discussions.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Review Manager (version 5.3, Copenhagen, Denmark). Pairwise meta-analyses were performed for each included outcome using a random-effects model. We used the mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) to estimate continuous outcomes. The standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI was used when continuous data were given on different scales. For the SMD, we considered 0.2 a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect [23]. For binary outcomes, we estimated the odds ratio (OR) with the 95% CI. Significant differences between groups were set at two-sided p-values smaller than 0.05. Statistical heterogeneity was estimated using the I² statistic and χ2 test. Based on I² values, statistical heterogeneity was categorized into low (< 30%), moderate (30% - 60%), or high (> 60%) [24]. If substantial heterogeneity was identified, we explored potential causes using prespecified subgroup analyses (study design, country, fracture type, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, local anesthetic, SA position, and time from intervention to SA). We also performed a sensitivity analysis to better understand the sources of statistical heterogeneity between studies and tested the robustness of our findings based on the RCTs that were excluded because of high or unclear risk in each domain of the risk of bias, RCTs that were excluded because of unclear information on the time from trauma to surgery or body weight, and RCTs that were excluded because of no use of a stimulator to assist FNB or ultrasound to guide FNB. Outcome measures were cross-validated using the mean difference. We applied a meta-regression to assess relationships between age, gender, the total equivalent concentration as lidocaine (calculated as follows: lidocaine = 1, bupivacaine = 4, and ropivacaine = 3) [25], total equivalent amount as lidocaine (calculated as the total equivalent concentration in lidocaine multiplied by the applied volume), and primary outcome using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version 3.3.070, Biostat, Inc., Englewood, New Jersey, USA). To calculate the power for a random-effects meta-analysis, we used anticipated summary effect size (SMD = 0.8, i.e. large effect) based on the study reported by Guay et al. [9] and the finding of our previous work [26]. The average number of participants per group, total number of effect sizes, and study heterogeneity were calculated based on current meta-analysis results. The power analysis was performed according to the method reported by Valentine et al. [27]. Given a two-sided type I error of 0.05, power large than 90% (i.e.βerror less than 10%) was regarded as powerful. If at least 10 studies were included, asymmetry in funnel plots was used to detect publication bias. We estimated the possible small study effects using Egger’s test [28].

Results

Results of the search

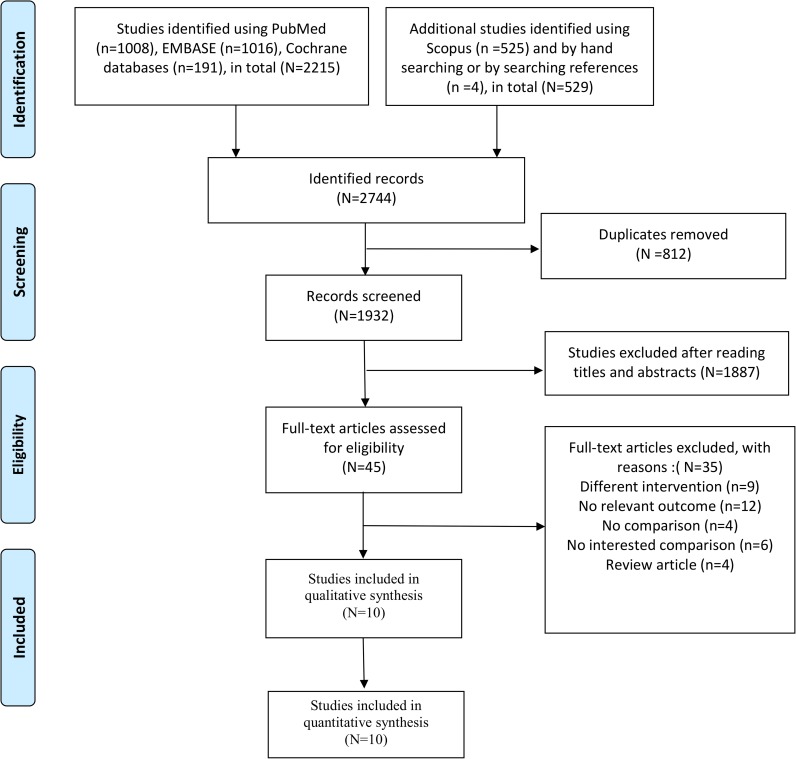

Fig 1 illustrates the screening and selection processes for the included studies. We identified 2,744 potentially relevant records through multiple database searches (PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane library (n = 2,215); Scopus) and by searching references (n = 529). A total of 1,932 studies remained after removing duplicate articles. We screened the titles and abstracts, and 1,887 articles were determined to be ineligible. Full-text articles were excluded with no comparison (n = 4), no comparison of interest (n = 6), different interventions (n = 9), no relevant outcome measure (n = 12), and review articles (n = 4). Ten studies [10–19] were ultimately included for qualitative and quantitative synthesis.

Fig 1. Flow diagram of the search process and search results.

Study characteristics

Tables 1 and S2 show the characteristics of the included studies. Eight studies [10–12, 14–18] were RCTs, and two studies [13, 19] observational studies. These studies were performed in single centers in Italy [16], Ireland [18], Pakistan [10], India [12, 13, 15, 17, 19], Nepal [14], and Thailand [11]. The study sample sizes ranged 24–100 subjects with 584 subjects in total. The average age of participants ranged 32–80.2 years. Three of the included studies [14, 16, 18] recruited more males than females for FNB. Two [10, 12] of the studies recruited a majority of females for FNB. Four [11, 15, 17, 19] studies recruited equal numbers of the two sexes, and one [13] study provided no information on sex. Three trials [10, 11, 16] reported the time from trauma to surgery, and averages ranged from 2.3–15.6 days. Two studies included an isolated femoral neck fracture [16, 18], one study included only femoral shaft fractures [13], and the other studies included all femur fractures [10–12, 14, 15, 17, 19]. Participants were ASA I, II or I-III in various proportions. Exclusion criteria were similar for those in the included studies. For the method of FNB, time from the intervention to SA varied from 5 to 30 min. Most studies used the landmark method [10–13, 15–19] or a stimulator [11–19] to perform FNB. The doses and types of local anesthetics were different. Seven studies [10, 12, 14–16, 18, 19] used lidocaine, two [11, 13] studies used bupivacaine, and one [17] study used ropivacaine. The dose and type of IVA also varied. Nine studies [11–19] used fentanyl, and one study [10] used nalbuphine. For the position for SA, six studies [10, 13, 14, 16–18] used the sitting position, and four studies [11, 12, 15, 19] did not use the sitting position.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Country | Design | Sample size | Inclusion criteria | FNB method | Regiment | SA position | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNB | IVA | ASA | Age (years) | Fracture type | Time from FNB to SA | Approach | Guidance | FNB | IVA | ||||

| Sia 2004 [16] | Italy | RCT, 1 center | 20 | 20 | I, II | NA | Femoral neck | 5 min | Landmark | Stimulator | L, 15 mL 1.5% | F, 3 µg/kg IV | Sitting |

| Szucs 2012 [18] | Ireland | RCT, 1 center | 12 | 12 | I~III | >50 | Femoral neck | 15 min | Landmark | Stimulator | L, 10 ml 2% | F, NA | Sitting |

| Durrani 2013 [10] | Pakistan | RCT, 1 center | 42 | 42 | I, II | 18–80 | Femur | 15 min | Landmark | No guidance | L, 15 ml, NA% with adrenaline | Nal, 6 mg IV | Sitting |

| Jadon 2014 [12] | India | RCT, 1 center | 30 | 30 | I~III | 15–70 | Femur | 5 min | Landmark | Stimulator | L, 20 mL, 1.5% with adrenaline | F, 1 µg/kg IV | Not sitting |

| Reddy 2016 [15] | India | RCT, 1 center | 36 | 36 | I~III | 18–70 | Femur | 5 min | Landmark | Stimulator | L, 20 mL, 1.5% with adrenaline | F, 1 µg/kg IV | Not sitting |

| Ranjit 2016 [14] | Nepal | RCT, 1 center | 20 | 20 | I, II | 18–75 | Femur | 5 min | Ultrasound | Stimulator | L, 20 mL, 1.5% with adrenaline | F, 2 µg/kg IV | sitting |

| Vats 2016 [19] | India | Observational study, 1 center | 50 | 50 | I-II | 18–70 | Femur | 5 min | Landmark | Stimulator | L, 20 mL, 1.5% with adrenaline | F, 1 µg/kg IV | Not sitting |

| Iamaroon 2010 [11] | Thailand | RCT, 1 center | 32 | 32 | I-II | 18–75 | Femur | 15 min | Landmark | Stimulator | B, 30 ml 0.3% | F, 0.5 µg/kg IV, two doses with a 5-min interval | Not sitting |

| Pakhare 2016 [13] | India | Observational study, 1 center | 30 | 30 | I-II | 18–65 | Femoral shaft | 30 min | Landmark | Stimulator | B, 30 ml 0.3% | F, 3 µg/kg IV | Sitting |

| Singh 2016 [17] | India | RCT, 1 center | 30 | 30 | I-II | 18–70 | Femur | 15 min | Landmark | Stimulator | R, 15 ml 0.2% | F, 0.5 µg/kg IV | Sitting |

RCT, randomized controlled trial; FNB, femoral nerve block; IVA, intravenous analgesic; NA, not available; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; SA, spinal anesthesia; L, lidocaine; B, bupivacaine; R, ropivacaine; F, fentanyl; Nal, Nalbuphine; IV, intravenous.

Assessment of the risk of bias

Table 2 describes the methodological quality of the identified studies. Most RCT studies were rated as low risk of bias of randomization, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. Three studies [12, 15, 16] had unclear information on allocation and concealment. But we rated all studies [10–19] as an unclear or high risk of performance bias because of the intervention method used. We also rated three studies [14–16] as having a high risk of bias because these studies did not perform prespecified sample size calculations. Two of the observational studies [13, 19] were identified. We rated one study [13] as moderate quality (NOS score: 6), and the other study [19] as high quality (NOS score: 8).

Table 2. Risk of bias assessment for included studies.

| Cochrane risk of bias assessment for randomized controlled trials | |||||||||||||

| Study | Randomization | Allocation and concealment | Blinding of participant and study personnel | Blinding of outcome assessor | Selective outcome reporting | Reporting bias | Other bias | ||||||

| Sia 2004 [16] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | High$ | ||||||

| Durrani 2013 [10] | Low* | Low# | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | ||||||

| Jadon 2014 [12] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | ||||||

| Reddy 2016 [15] | Low* | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | High$ | ||||||

| Ranjit 2016 [14] | Low* | Low# | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | High$ | ||||||

| Iamaroon 2010 [11] | Low* | Low# | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | ||||||

| Szucs 2012 [18] | Low* | Low# | Unclear | Unclear | low | low | Low | ||||||

| Singh 2016 [17] | Low* | Low# | Unclear | Unclear | low | low | Low | ||||||

| Newcastle-Ottawa scale& (NOS) for assessment of observational studies | |||||||||||||

| Study, year | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score | |||||||||

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcomes | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur? | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | ||||||

| Age | Sex | ||||||||||||

| Vats 2016 [19] | Truly ★ | Same community ★ | Good ★ | Yes ★ | Yes ★ | Yes ★ | No description - | Yes ★ | Complete follow-up ★ | 8 | |||

| Pakhake 2016 [13] | Truly ★ | Same community ★ | Good ★ | Yes ★ | No - | No - | No description - | Yes ★ | Complete follow-up ★ | 6 | |||

* Random number table;

# sealed envelope;

$ No prespecified sample size calculation;

★one star indicates 1 score;

& The NOS is a nine-point scale with a maximum of four points allocated to selection, two points for comparability, and three points for outcome. Studies scoring ≥7 were considered high quality; 4~6, moderate quality; and ≤4, low quality.

Primary outcomes

Pain scores during positioning before SA (within 30 min)

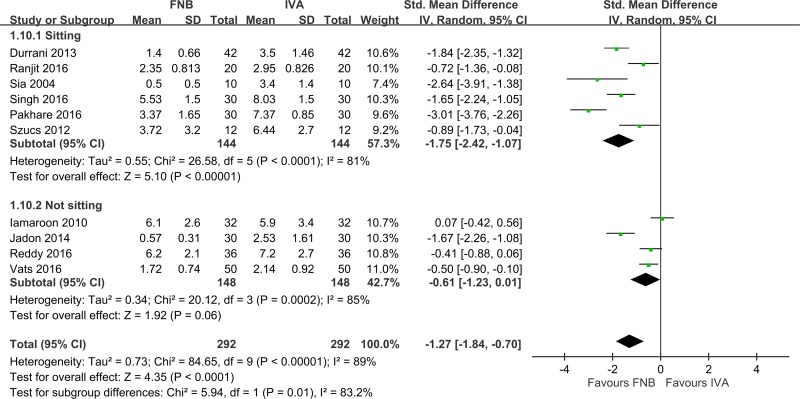

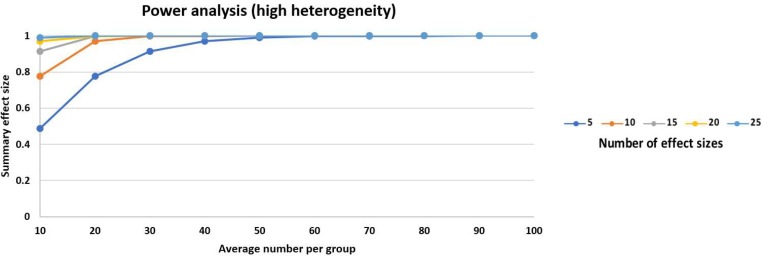

All ten studies [10–19] (n = 584) evaluated pain scores during positioning within 30 min before SA (Fig 2). FNB achieved significantly lower pain scores than IVA (pooled SMD: -1.27, 95% CI: -1.84 to -0.70, p < 0.05, I2 = 89%). This finding was powerful (Fig 3).

Fig 2. Forest plot of positioning before spinal anesthesia (within 30 min).

Fig 3. Power analysis for meta-analysis.

The power was calculated as 0.9963 based on the anticipated effect size of SMD = 0.8, the 10 identified studies, average of 29 participants per group and high heterogeneity between studies.

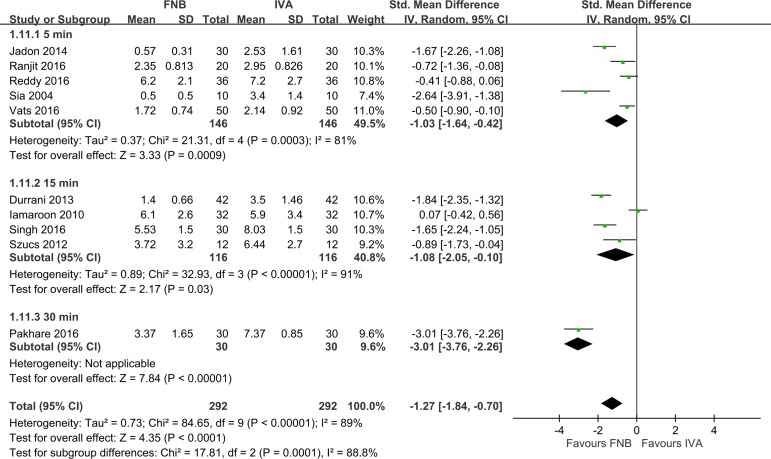

A subgroup analysis showed that pain scores reduction changed with the SA position and time from FNB to SA. Pain scores reduction was not influenced by the study design, country, fracture type, ASA classification, or type of local anesthetic (Table 3). FNB had larger pain score reductions than IVA in the sitting position (Fig 2, six studies (n = 288), pooled SMD: -1.75, 95% CI: -2.42 to -1.07, p < 0.05, I2 = 81%). However, FNB had smaller pain score reductions than IVA in a non-sitting position, but this effect was statistically insignificant (Fig 2, four studies (n = 296), pooled SMD: -0.61, 95% CI: -1.23 to 0.01, p = 0.06, I2 = 85%). Notably, heterogeneity remained high. As to the time from FNB to SA, FNB had larger pain score reductions in 30 min than 5 or 15 min (Fig 4, pooled SMD: 30 min (-3.01, p < 0.05) vs. 5 min (-1.03, p < 0.05) and 15 min (-1.08, p < 0.05)). However, the results for 30 min were collected from only one study [17], which makes this estimate less reliable.

Table 3. Predefined clinical subgroup analysis with pain scores during positioning comparing femoral nerve block with intravenous analgesic.

| Category | Subgroups | No. of studies | No. of patients | SMD (95% CI) | p value | Group heterogeneity | Subgroup difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | p value | I2 | p value | ||||||

| Outcome: pain scores during positioning | |||||||||

| Study design | RCT | 8 | 424 | -1.15 (-1.74, -0.57) | <0.05 | 86 | <0.0001 | 0 | 0.65 |

| Observational study | 2 | 160 | -1.73 (-4.19,0.73) | 0.17 | 97 | <0.0001 | |||

| Country | India | 5 | 352 | -1.41 (-2.25, -0.57) | <0.05 | 92 | <0.0001 | 0 | 0.65 |

| Not India | 5 | 232 | -1.13 (-2.02.-0.24) | <0.05 | 89 | <0.0001 | |||

| Fracture type | Isolated Femoral neck Fracture | 2 | 44 | -1.70 (-3.41,0.02) | 0.05 | 80 | < 0.05 | 0 | 0.58 |

| Femur fracture | 8 | 584 | -1.19 (-1.82, -0.56) | <0.05 | 91 | <0.0001 | |||

| ASA classification | I-II | 6 | 428 | -1.79 (-2.86, -0.73) | <0.05 | 96 | <0.0001 | 0 | 0.93 |

| I-III | 4 | 156 | -1.74 (-2.74, -1.00) | <0.05 | 29 | 0.24 | |||

| Local anesthetic | Lidocaine | 7 | 400 | -1.15 (-1.69, -0.61) | <0.05 | 83 | <0.0001 | 0 | 0.48 |

| Ropivacaine | 1 | 60 | -1.65 (-2.24, -1.05) | <0.05 | NA | NA | |||

| Bupivacaine | 2 | 124 | -1.46 (-4.45,1.55) | 0.34 | 98 | <0.0001 | |||

| SA position | Sitting | 6 | 288 | -1.75 (-2.42, -1.07) | <0.05 | 81 | <0.0001 | 83.2 | 0.01* |

| Not sitting | 4 | 296 | -0.61 (-1.23,0.01) | 0.06 | 85 | <0.0001 | |||

| Time from intervention to SA | 5 min | 5 | 292 | -1.03 (-1.64, -0.42) | <0.05 | 81 | 0.0003 | 88.8 | < 0.05* |

| 15 mins | 4 | 232 | -1.08 (-2.05, -0.10) | <0.05 | 91 | <0.0001 | |||

| 30 min | 1 | 60 | -3.01 (-3.76, -2.26) | <0.05 | NA | NA | |||

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CI, confidence interval; RCT, randomized control trial; SA, spinal anesthesia; SMD, standardized mean difference;

*, statistically significant.

Fig 4. Forest plot for comparisons of pain scores during positioning before spinal anesthesia (within 30 min) subgroup by time from intervention to spinal anesthesia.

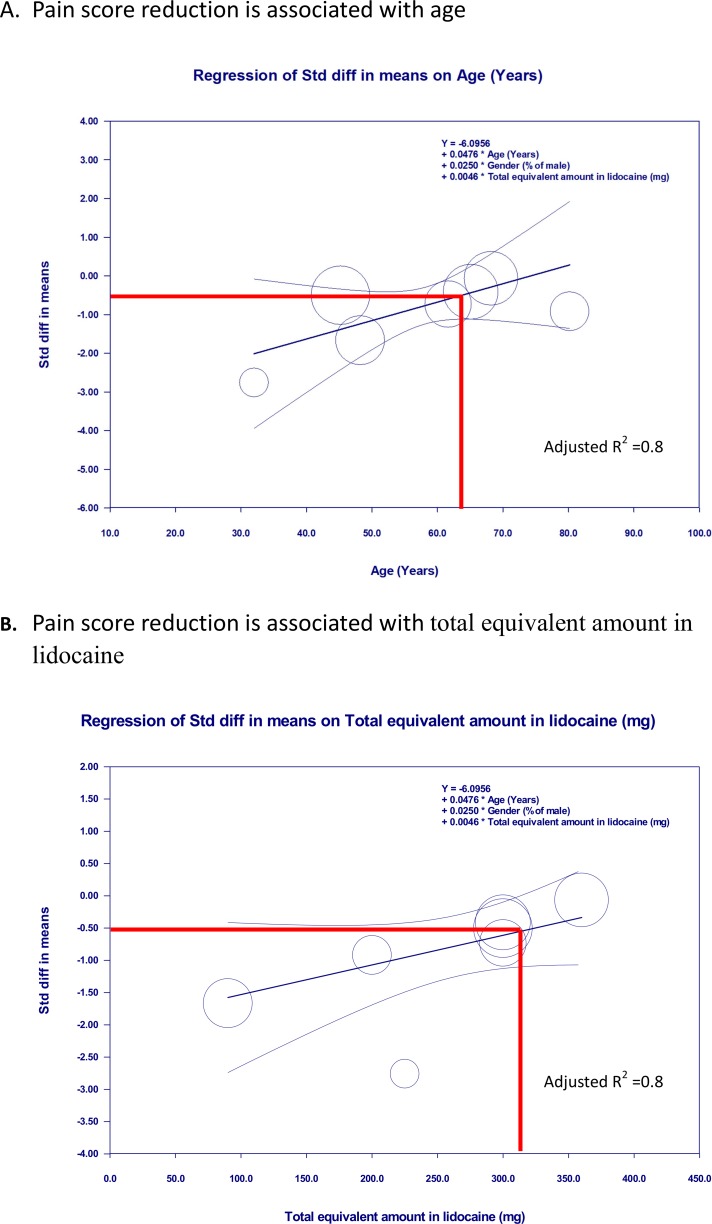

We performed a meta-regression to determine whether the effect size varied with age, gender, total equivalent concentration as lidocaine, and total equivalent amount as lidocaine. The SMD for FNB compared to IVA was not moderated by age (p = 0.21), gender (p = 0.23), total equivalent concentration as lidocaine (p = 0.52), or total equivalent amount as lidocaine (p = 0.58) according to a univariate regression model (Table 4). After adjusting for gender, age, or the total equivalent amount as lidocaine, both factors showed a positive association with SMD for pain scores (Table 5, models 1, 2, and 5), but the total equivalent concentration as lidocaine showed no association with the primary outcome after adjusting for gender (Table 5, models 2 and 3). Model 5 was the best model for predicting the association with effect sizes after adjusting for gender (Table 5, model 5, adjusted R2 = 0.80). The SMD of pain scores were increased by 0.048 for every year increase in patient age (p < 0.05). The SMD of pain scores were increased by 0.005 for every milligram increase in the total equivalent amount as lidocaine (p < 0.05) (Fig 5).

Table 4. Univariate meta-regression predicting estimates of pain scores during positioning between femoral nerve block and intravenous analgesic.

| Covariate | No. of study | Univariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted R2 | ||

| Gender (% of male) | 9 | -0.018 (-0.048–0.011) | 0.23 | 0.06 |

| Age (years) | 9 | 0.030 (-0.017–0.076) | 0.21 | 0 |

| Equivalent amount in lidocaine | 9 | 0.059 (-0.122–0.239) | 0.52 | 0 |

| Equivalent concentration in lidocaine | 9 | 0.002 (-0.005–0.010) | 0.58 | 0 |

CI, confidence interval.

Table 5. Multivariate meta-regression models predicting estimates of pain scores during positioning.

| Covariate | Multivariate analysis | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (No. of study = 8) | Model 2 (No. of study = 8) | Model 3 (No. of study = 8) | Model 4 (No. of study = 7) | Model 5 (No. of study = 7) | |||||||||||

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p | Adjusted R2 | Coefficient (95% CI) | p | Adjusted R2 | Coefficient (95% CI) | p | Adjusted R2 | Coefficient (95% CI) | p | Adjusted R2 | Coefficient (95% CI) | p | Adjusted R2 | |

| Gender (% of male) | 0.035 (0.015–0.085) | 0.17 | 0.28 | -0.014 (-0.039–0.011) | 0.28 | 0.38 | -0.014 (-0.050–0.022) | 0.44 | 0 | 0.04 (-0.018–0.098) | 0.18 | 0 | 0.024 (-0.011–0.060) | 0.18 | 0.80 |

| Age(years) | 0.077 (0.014–0.141) | 0.02* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.076 (0.006–0.146) | 0.03* | 0.048 (0.001–0.096) | 0.04* | |||

| Equivalent amount in lidocaine | NA | NA | NA | 0.006 (0.001–0.011) | 0.03* | 0.38 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.005 (0.001–0.009) | 0.02* | |

| Equivalent concentration in lidocaine | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.003 (-0.168–0.173) | 0.97 | 0 | 0.008 (-0.160–0.175) | 0.93 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

NA, no analysis;

*, statistically significant.

Fig 5. Meta-regression for standardized mean difference (SMD) of pain scores during positioning for spinal anesthesia between femoral nerve block and intravenous analgesics.

A. The SMD is proportional to the age of the patient. B. The SMD is proportional to the total equivalent amount as lidocaine, i.e., FNB using a low total equivalent amount as lidocaine or use in younger patients was associated with more analgesic effect than IVA after adjusting for gender.

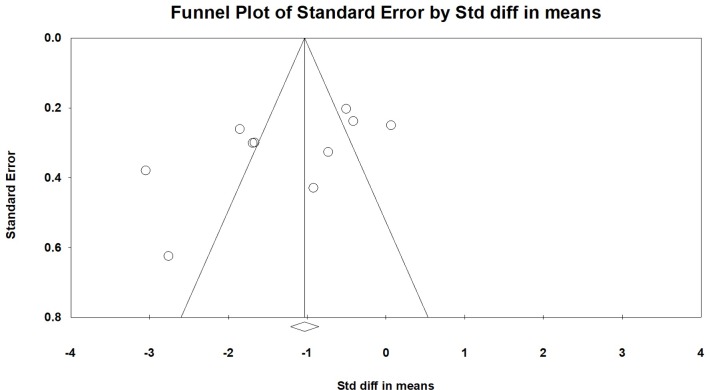

We performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of our findings based on RCTs that were excluded because of high or unclear risk in each domain of the risk of bias, RCTs that were excluded because of unclear information about the time from trauma to surgery (days) or body weight, RCTs that were excluded because of no use of a stimulator, and RCTs that were excluded because of no use of ultrasound guidance. These factors did not influence our findings (Table 6). We used the mean difference to cross-validate the outcome measure. This result also indicated that our findings were robust. The funnel plots that showed no asymmetry, which indicates no evidence of a small study effect (Fig 6, Egger’s test: not significant).

Table 6. Sensitivity analyses: The effect of potential biases on primary outcomes.

| Potential bias or limitations excluded | No of studies | No of patients | SMD (95% CI) | I2 (%) | P value | MD (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 10 | 584 | -1.27 (-1.84, -0.70) | 89 | <0.0001 | -1.79 (-2.62, -0.96) | 94 | < 0.0001 |

| RCT qualitya | ||||||||

| RCT overall | 8 | 424 | -1.15 (-1.74, -0.57) | 86 | 0.0001 | -1.70 (-2.38, -1.01) | 83 | < 0.0001 |

| Randomization | 7 | 404 | -1.01 (-1.60, -0.42) | 87 | 0.0008 | -1.52 (-2.22, -0.81 | 82 | < 0.0001 |

| Allocation and concealment | 5 | 272 | -0.98 (-1.24, -0.72) | 88 | <0.00001 | -1.52 (-1.83, -1.21) | 87 | < 0.0001 |

| Blinding of outcome assessor | 2 | 84 | -1.22 (-3.87,1.43) | 93 | 0.37 | -1.44 (-4.44,1.63) | 92 | 0.36 |

| Other bias | 5 | 292 | -1.20 (-1.99, -0.40) | 89 | 0.003 | -1.92 (-2.54, -1.30) | 62 | < 0.0001 |

| Participantsb | ||||||||

| Time from trauma to surgery (days) | 3 | 168 | -1.40 (-2.98,0.17) | 94 | 0.08 | -1.76 (-3.04, -0.47) | 84 | < 0.01 |

| Weight(kg) | 4 | 216 | -1.05 (-2.01, -0.08) | 90 | 0.03 | -1.54 (-2.61, -0.48) | 80 | < 0.01 |

| Method | ||||||||

| FNB with stimulatorc | 9 | 500 | -1.20 (-1.81, -0.59) | 89 | 0.0001 | -1.75 (-2.71, -0.81) | 94 | < 0.0001 |

| FNB by landmarkd | 9 | 544 | -1.33 (-1.96, -0.70) | 90 | < 0.001 | -1.94 (-2.87.-1.01) | 94 | < 0.0001 |

a, excluded high or unclear risk;

b, excluded with unclear information for time from trauma to surgery (days), body weight (kg),

c, excluded with no use of stimulator;

d, excluded use of ultrasound guidance;

CI, confidence interval; SMD, standardized mean difference; MD, mean difference

Fig 6. Funnel plots for the comparisons of FNB with IVA on pain scores during positioning.

Standardized mean difference against standard error for 10 simulated studies of varying sample size where there is no publication bias.

Secondary outcomes

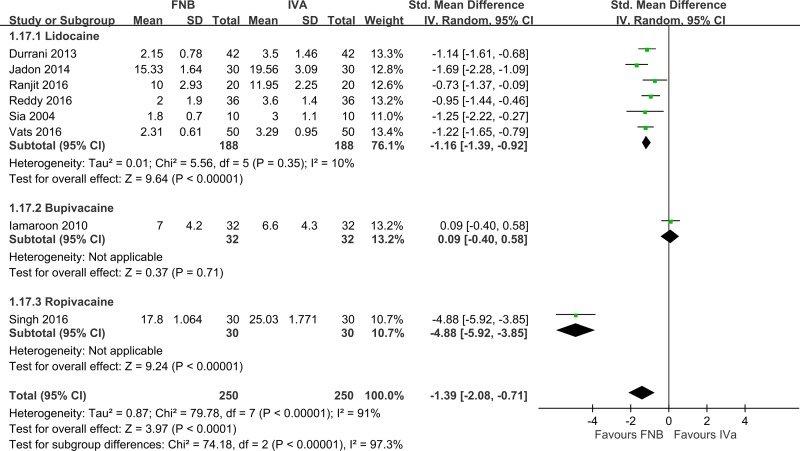

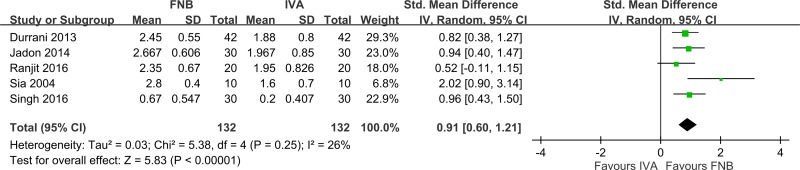

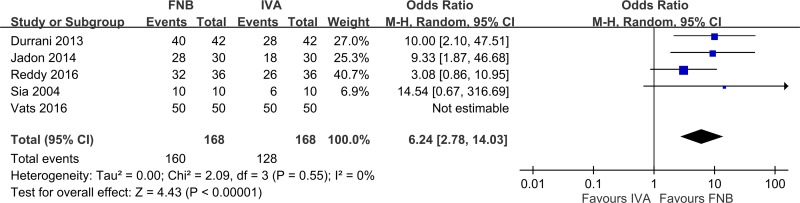

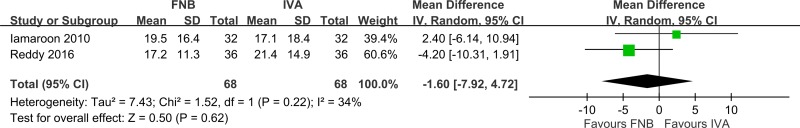

Compared to IVA, patients who received FNB had a significantly shorter time for SA (Fig 7, eight studies [10–12, 14–17, 19], 500 patients; pooled SMD: -1.39; 95% CI: -2.08 to -2.71, p <0.05; I2 = 91%). Heterogeneity was high, which resulted from the type of local anesthetic (Singh 2016 [17] (ropivacaine); Iamaroon 2010 [11] (bupivacaine); and others [10, 12, 14–16, 19] (lidocaine)). Anesthesiologists were more satisfied with FNB than IVA (Fig 8, five studies [10, 12, 14, 16, 17], 264 patients; pooled SMD: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.60 to 1.21, p < 0.05; I2 = 26%). Participants preferred FNB for analgesia (Fig 9, five studies [10, 12, 15, 16, 19], 336 patients; pooled OR: 6.24; 95% CI: 2.78 to 14.03, p < 0.05; I2 = 0%). Patients who used FNB also had lower additional analgesic requirements than patients who used IVA, but the effect was small and not statistically significant (Fig 10, two studies [11, 15] 136 patients; pooled SMD: -0.10; 95% CI: -0.54 to 0.34, p = 0.62; I2 = 41%).

Fig 7. Forest plot of time for spinal anesthesia (min).

FNB, femoral nerve block; IVA, intravenous analgesic.

Fig 8. Forest plot of anesthesiologist’s satisfaction with the quality of spinal anesthesia.

FNB, femoral nerve block; IVA, intravenous analgesic.

Fig 9. Forest plot of participant acceptance.

FNB, femoral nerve block; IVA, intravenous analgesic.

Fig 10. Forest plot of additional analgesic requirements.

FNB, femoral nerve block; IVA, intravenous analgesic; CI, confidence interval.

Safety outcomes

Compared to IVA, FNB using lidocaine had a slightly higher mean MAP by 3.11 mmHg (S1 Fig, four studies [12, 14, 15, 19], 272 patients; pooled MD: 3.11; 95% CI: 0.18 to 6.05, p < 0.05; I2 = 61%). Pakhare et al. [13] used bupivacaine for FNB and reported a lower mean MAP by 4.30 mmHg (n = 60, 95% CI: -6.16 to -2.44, p <0.05). No significant difference in mean heart rate was detected between FNB using lidocaine and IVA (S2 Fig, four studies [12, 14, 15, 19], 272 patients; pooled MD: 0.99 beats/min; 95% CI: -1.31 to 3.11, p = 0.99; I2 = 0%). Pakhare et al. [13] used bupivacaine for FNB and reported a lower mean heart by 11.61 beats/min (n = 60, 95% CI: -14.49 to -8.77, p < 0.05). Three studies [12, 14, 15] reported that FNB using lidocaine and IVA provided adequate mean SpO2 values (> 94%), as shown in S3 Fig. The safety outcome of interest for FNB using ropivacaine was lacking.

Discussion

The main findings of the present meta-analysis were that 10 studies [10–19] comprising 584 participants showed that FNB was superior to IVA. FNB resulted in significantly lower pain scores during positioning within 30 min before SA. Eight studies [10–12, 14–17, 19] (500 participants) showed that FNB also reduced the time to perform SA compared to IVA. This finding means that FNB provided more effective analgesia, which improved patient positioning. Anesthesiologists and participants preferred FNB for analgesia. Different local anesthetics used for FNB differentially impacted hemodynamic parameters, but the effect was small.

Regarding pain scores during positioning, a previous meta-analysis performed by Guay et al. [9] reported that peripheral nerve block reduced pain on movement within 30 min. But, the heterogeneity in this study was high, and the effect was associated with the total equivalent concentration as lidocaine. This result was limited by the including of patients from various clinical situations with different types of nerve block. Our meta-analysis focused on positioning patients with a femur fracture for a spinal block in the operative setting. We found that the result of the analgesic effect was consistent with Guay et al. [9]. However, an association between the analgesic effect and total equivalent concentration as lidocaine was not observed in the univariate or multivariate regression model in our study. Our study found that the analgesic effect was associated with age, the total equivalent amount as lidocaine or both, after adjusting for gender. The reasons for the discrepancy with the previous study are that these studies included patients from different clinical entities, inadequate analgesia of IVA secondary by dose differences and variation of IVA, the time to evaluated the pain scores, the use of different volumes of local anesthetics and different baseline characteristics. We found that FNB achieved a larger than median analgesic effect that was associated with the use of a total equivalent amount of lidocaine of < 300 mg and patients aged < 63 years (Fig 5). However, this finding should be interpreted with caution because these analyses investigated differences between studies. Whether the application of FNB using a low amount of lidocaine or in patients younger than 63 years produces larger than median analgesic effects is not known. Further well-designed studies are warranted to establish a causal relation.

Another strength of our meta-analysis is that we performed a sensitivity analysis to better recognize the sources of heterogeneity among the included studies. The results indicated that our findings were robust based on RCTs that were excluded because of high or unclear risk in each domain of risk of bias, RCTs that were excluded because of unclear information about the time from trauma to surgery or body weight, and RCTs that were excluded that did not use a stimulator to assist FNB or use ultrasound to guide FNB. Forouzan et al. [29] also reported that ultrasonography- and nerve stimulator-guided FNB exhibited the same success rates and block durations. As to participant factors, only a few studies [10, 11, 16] clearly reported the time from trauma to surgery and body weight. Therefore, we suggest that further studies consider these factors, which may differentially influence the primary outcome.

SA may be performed in a lateral decubitus or sitting position. The decision of which position to use to perform SA is an individual choice that exhibits no obviously clear or consistent regional or even institutional associations. For the impact of positioning patients for SA, a meta-analysis by Zorrilla-Vaca et al. [30] indicated that the lateral decubitus position was associated with a reduction of 39% relative risk on the incidence of post-dural puncture headaches compared to the sitting position. The results of our meta-analysis showed that FNB produced a greater pain score reduction than IVA in the sitting and non-sitting positions, but the effect size was larger in the sitting position group. This difference means that most patients experienced less pain using FNB for patients with femur fractures in the sitting position to approach SA. One explanation is that patients who change from a supine position to sitting may need to flex the hip joint or put traction on the femur fracture, which may elicit more pain than patients changing from a supine position to a non-sitting position, such as with the lateral decubitus position [15, 31].

Concern about the use of nerve blocks to aid positioning may delay operating lists. and the analgesic effect of lidocaine is felt within 5 min, but 20–30 min are required for bupivacaine to exert its effect [32]. Our study found that lidocaine, bupivacaine, and ropivacaine all had larger analgesic effects than IVA. Six [10, 12, 14–16, 19] of the included studies using lidocaine showed homogeneous results in reduced times for SA. Peripheral nerve block may be administered before surgery in the anesthesia induction room with adequate equipment [33]. As mentioned above, we suggest that FNB using lidocaine in the anesthesia induction room may balance this concern.

SA was a preferred and commonly used method for femur fracture surgery. Use of SA was associated with a 25%– 29% reduction in major pulmonary complications and death [5] due to the avoidance of intubation and mechanical ventilation, decreased blood loss, and improved postoperative analgesia [6]. Opioids are commonly used and offer good analgesia in femur fracture patients. However, opioids are notorious for adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression [8]. Opioids may also induce delirium in these patients [34, 35]. Diminishing opioid consumption and unnecessary complications are crucial [36]. Our meta-analysis showed that patients using FNB had lower additional postoperative analgesic requirements than patients using IVA, but this effect was small and not statistically significant. This finding was related to only two studies [11, 15] that reported this outcome and included relatively small sample sizes. Guay et al. [9] included seven studies and 285 participants and reported that peripheral nerve block, administered as a single shot or continuous block, resulted in less postoperative opioid requirements compared to no nerve block. Diakomi et al. [37] compared FINB to IVA to facilitate positioning for femur fracture patients under spinal block. Their study results also showed that FINB had lower opioid requirements than IVA. Another meta-analysis by Wang et al. [38] included four studies and showed that FNB and FINB resulted in similar opioid requirements until 48 h postoperatively in patients undergoing total knee and hip arthroplasties. Taken together, we suggest the need for more studies to elucidate the impact of FNB on postoperative opioid requirements.

Study limitations

Our meta-analysis has some limitations. Because the inclusion of observational studies could bias estimates of the true intervention effect, we performed subgroup analyses and found that the analgesic effect was not significantly different between RCTs and observational studies. Given that pediatric patients were not involved in the identified trials, generalization to that group should be done with great caution. Our meta-analysis was based on ten recently published studies [10–19]. But the sample sizes were relatively small, and these studies were primarily performed in a single center in developing countries. We had insufficient power to demonstrate the effect on additional analgesic requirement. Functional outcomes were not analyzed because of insufficient data. The follow-up periods were too short to analyze long-term complications.

Conclusion

FNB is an effective strategy that provides significantly better analgesia to facilitate the positioning of femur fracture patients for a spinal block, particularly patients who receive SA in the sitting position. In this meta-analysis, the analgesic effect was associated with the amount of local anesthetics and patient age. FNB also required less time for SA, had lower postoperative opioid requirements, had higher anesthesiologist satisfaction and patient acceptance, and produced no major hemodynamic instabilities.

Supporting information

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Winston W. Shen for English-editing of our revised manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors, Yuan-Pin Hsu, Jin-Hua Chen and Chiehfeng Chen, are very grateful for financial support from project no. 108-wf-eva-01 of Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

References

- 1.Requena G, Abbing-Karahagopian V, Huerta C, De Bruin ML, Alvarez Y, Miret M, et al. Incidence rates and trends of hip/femur fractures in five European countries: comparison using e-healthcare records databases. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014; 94: 580–9. 10.1007/s00223-014-9850-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikolaou VS, Stengel D, Konings P, Kontakis G, Petridis G, Petrakakis G, et al. Use of femoral shaft fracture classification for predicting the risk of associated injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2011; 25: 556–9. 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318206cd06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD. Hip Fractures: I. Overview and evaluation and treatment of femoral-neck fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994; 2: 141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maxwell L, White S. Anaesthetic management of patients with hip fractures: an update. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2013; 13: 179–83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuman MD, Silber JH, Elkassabany NM, Ludwig JM, Fleisher LA. Comparative effectiveness of regional versus general anesthesia for hip fracture surgery in adults. Anesthesiology. 2012; 117: 72–92. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182545e7c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker MJ, Handoll HH, Griffiths R. Anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2004; (4): CD000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duc TA. Postoperative pain control In: Conroy JM, Dorman BH, editors. Anesthesia for orthopedic surgery. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1994: 355–65. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, Buenaventura R, Adlaka R, Sehgal N, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008; 11 (2 Suppl): S105–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guay J, Parker MJ, Griffiths R, Kopp SL. Peripheral nerve blocks for hip fractures: a Cochrane review. Anesth Analg. 2018; 126: 1695–17047. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durrani H, Butt KJ, Khosa AH, Umer A, Pervaiz M. Pain relief during positioning for spinal anesthesia in patients with femoral fracture: a comparison between femoral nerve block and intravenous nalbuphine. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2013; 7: 928–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iamaroon A, Raksakietisak M, Halilamien P, Hongsawad J, Boonsararuxsapong K. Femoral nerve block versus fentanyl: analgesia for positioning patients with fractured femur. Local Reg Anesth. 2010; 3: 21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jadon A, Kedia SK, Dixit S, Chakraborty S. Comparative evaluation of femoral nerve block and intravenous fentanyl for positioning during spinal anaesthesia in surgery of femur fracture. Indian J Anaesth. 2014; 58: 705–8. 10.4103/0019-5049.147146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pakhare PV, Pendyala P. A randomized prospective study of comparison of IV fentanyl vs. femoral nerve block to facilitate administration of subarachnoid block in sitting position for femur fracture surgeries. Indian Journal of Clinical Anaesthesia. 2016; 3: 507–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranjit S, Pradhan B. Ultrasound guided femoral nerve block to provide analgesia for positioning patients with femur fracture before subarachnoid block: comparison with intravenous fentanyl. Kathmandu University Medical Journal. 2016; 14: 125–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy E, Rao B. Comparative study of efficacy of femoral nerve block and IV fentanyl for positioning during femur fracture surgery. International Surgery Journal. 2016: 321–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sia S, Pelusio F, Barbagli R, Rivituso C. Analgesia before performing a spinal block in the sitting position in patients with femoral shaft fracture: a comparison between femoral nerve block and intravenous fentanyl. Anesth Analg. 2004; 99: 1221–4 10.1213/01.ANE.0000134812.00471.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh AP, Kohli V, Bajwa SJ. Intravenous analgesia with opioids versus femoral nerve block with 0.2% ropivacaine as preemptive analgesic for fracture femur: a randomized comparative study. Anesth Essays Res. 2016; 10: 338–42. 10.4103/0259-1162.176403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szucs S, Iohom G, O’Donnell B, Sajgalik P, Ahmad I, Salah N, et al. Analgesic efficacy of continuous femoral nerve block commenced prior to operative fixation of fractured neck of femur. Perioperative Medicine. 2012; 1: 4 10.1186/2047-0525-1-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vats A, Gandhi M, Jain P, Arora K. Comparative evaluation of femoral nerve block and intravenous fentanyl for positioning during spinal anaesthesia in surgeries of femur fracture. International Journal of Contemporary Medical Research. 2016; 3: 2298–2301. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 6: e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011; 343: d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis. Ottawa, Ontario: The Ottawa Health Research Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pace NL. Research methods for meta-analyses. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2011; 25: 523–33. 10.1016/j.bpa.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002; 21: 1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berde CB SG. Local anesthetics (Chapter 30) In: Miller RD, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Young WL editor(s). Miller’s Anesthesia. 7th Edition. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu YP, Hsu CW, Bai CH, Cheng SW, Chen C. Fascia iliaca compartment block versus intravenous analgesic for positioning of femur fracture patients before a spinal block: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018; 97: e13502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valentine SJ, Stokes ST, Kurulugama RT, Nachtigall FM, Clemmer DE. Overtone mobility spectrometry: part 2. Theoretical considerations of resolving power. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009; 20: 738–50. 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. 2006; 25: 3443–57. 10.1002/sim.2380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forouzan A, Masoumi K, Motamed H, Gousheh MR, Rohani A. Nerve stimulator versus ultrasound guided femoral nerve block; a randomized clinical Trial. Emerg (Tehran). 2017; 5: e54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andres Zorrilla-Vaca MaJKM MD, DNB. Effectiveness of lateral decubitus position for preventing post-dural puncture headache: a meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 2017; 20: E521–E9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandby-Thomas M, Sullivan G, Hall JE. A national survey into the peri-operative anaesthetic management of patients presenting for surgical correction of a fractured neck of femur. Anaesthesia. 2008; 63: 250–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urbanek B, Duma A, Kimberger O, Huber G, Marhofer P, Zimpfer M, et al. Onset time, quality of blockade, and duration of three-in-one blocks with levobupivacaine and bupivacaine. Anesth Analg. 2003; 97: 888–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yun M, Han M, Park S, Do S, Kim Y. Analgesia prior to spinal block in the lateral position in elderly patients with a femoral neck fracture: a comparison of fascia iliaca compartment block and intravenous alfentanil. Eur J Anaesth. 2009; 26: 111. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petre BM, Roxbury CR, McCallum JR, Defontes KW 3rd, Belkoff SM, Mears SC. Pain reporting, opiate dosing, and the adverse effects of opiates after hip or knee replacement in patients 60 years old or older. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2012; 3: 3–7. 10.1177/2151458511432758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zywiel MG, Prabhu A, Perruccio AV, Gandhi R. The influence of anesthesia and pain management on cognitive dysfunction after joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014; 472: 1453–66. 10.1007/s11999-013-3363-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee LA, Caplan RA, Stephens LS, Posner KL, Terman GW, Voepel-Lewis T, et al. Postoperative opioid-induced respiratory depression: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2015; 122: 659–65. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diakomi M, Papaioannou M, Mela A, Kouskouni E, Makris A. Preoperative fascia iliaca compartment block for positioning patients with hip fractures for central nervous blockade: a randomized trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014; 39: 394–8. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, Sun Y, Wang L, Hao X. Femoral nerve block versus fascia iliaca block for pain control in total knee and hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis from randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017; 96: e7382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.