Abstract

Background

The prognostic significance of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the contemporary era is unclear. We performed a large, prospective cohort study and did a landmark analysis to delineate the association of OSA with subsequent cardiovascular events after ACS onset.

Methods and Results

Between June 2015 and May 2017, consecutive eligible patients admitted for ACS underwent cardiorespiratory polygraphy during hospitalization. OSA was defined as an apnea‐hypopnea index ≥15 events·h−1. The primary end point was major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event (MACCE), including cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, ischemia‐driven revascularization, or hospitalization for unstable angina or heart failure. OSA was present in 403 of 804 (50.1%) patients. During median follow‐up of 1 year, cumulative incidence of MACCE was significantly higher in the OSA group than in the non‐OSA group (log‐rank, P=0.041). Multivariate analysis showed that OSA was nominally associated with incidence of MACCE (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.55; 95% CI, 0.94–2.57; P=0.085). In the landmark analysis, patients with OSA had 3.9 times the risk of incurring a MACCE after 1 year (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.87; 95% CI, 1.20–12.46; P=0.023), but no increased risk was found within 1‐year follow‐up (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.67–2.09; P=0.575). No significant differences were found in the incidence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and ischemia‐driven revascularization, except for a higher rate of hospitalization for unstable angina in the OSA group than in the non‐OSA group (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.09–4.05; P=0.027).

Conclusions

There was no independent correlation between OSA and 1‐year MACCE after ACS. The increased risk associated with OSA was only observed after 1‐year follow‐up. Efficacy of OSA treatment as secondary prevention after ACS requires further investigation.

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea, outcome

Subject Categories: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Risk Factors

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

There was no independent correlation between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and 1‐year major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event after acute coronary syndrome.

Patients with OSA had 3.9 times the risk of incurring a major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event after 1 year, but no increased risk was evident within 1 year.

No significant differences were found in the incidence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and ischemia‐driven revascularization, except for a higher rate of hospitalization for unstable angina in the OSA group than in the non‐OSA group.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The adverse effect of OSA in acute coronary syndrome patients might become more pronounced with an increasing duration of follow‐up.

Treatment effects of continuous positive airway pressure for secondary prevention of acute coronary syndrome still need to be evaluated.

Appropriate timing and duration of intervention warrants further investigation, given that any randomized trial of continuous positive airway pressure or other therapy for ≤1 year will be unlikely to demonstrate significant benefit of therapy, given the absence of significant risk associated with OSA within the first year of acute coronary syndrome.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is highly prevalent in patients with cardiovascular diseases.1, 2 Increasing evidence indicates that OSA is associated with incidence and progression of coronary artery disease3, 4, 5 and cerebrovascular disease.6 Among patients with coronary artery disease, those with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) represent a high‐risk subset and generally have higher mortality than patients with stable angina.7 Compared with the general population, prevalence of OSA is higher in ACS patients and ranges from 36% to 63% across various ethnicities.8 Previous observational studies have examined whether OSA significantly increased risk of recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with ACS and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).9, 10, 11, 12 However, results are inconsistent, and most studies, except the Sleep and Stent study,12 were not done in the era of new‐generation drug‐eluting stents and modern antithrombotic therapy, thus precluding definite conclusions in the context of contemporary therapeutic strategies. Given that guideline‐based optimal medical therapy was administered after ACS onset, especially within the first year,13, 14 we hypothesized that the prognostic significance of OSA would vary across different time periods after ACS presentation. Therefore, we performed a large‐scale, prospective cohort study and did a landmark analysis to delineate the association of OSA with subsequent cardiovascular outcomes in patients with ACS.

Methods

Data, analytical methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

Study Design and Population

The OSA‐ACS project (NCT03362385) is a large‐scale, single‐center, prospective, observational study to assess the association of OSA with cardiovascular outcomes of patients with ACS in the contemporary era. For the current study, we performed a landmark analysis at a median follow‐up of 1 year. Consecutive patients aged 18 to 85 years and admitted for ACS to the Emergency & Critical Care Center of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University between June 2015 and May 2017 were eligible for inclusion. ACS was defined as acute presentation of coronary disease, including ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction, non‐ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction, and unstable angina. Exclusion criteria were as follows: cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, previous or current use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), malignancy, and failed sleep study (patients without adequate and satisfactory signal recording). Patients with predominantly central sleep apnea (≥50% central events or central apnea hypopnea index [AHI] ≥10·h−1) and those receiving regular CPAP therapy (>3 months) after hospitalization were excluded from the analysis. This study conformed to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) guidelines and was conducted in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University approved the study (2013025). All patients provided informed consent.

Overnight Sleep Study

All patients underwent an overnight sleep study after clinical stabilization during hospitalization (within 2 weeks after admission) using portable cardiorespiratory polygraphy (ApneaLink, Resmed, Australia), which was validated in the SAVE (Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints) study.15, 16 Nasal airflow, thoracoabdominal movements, arterial oxygen saturation, and snoring episodes were recorded. An apnea was defined by an absence of airflow lasting ≥10 seconds (obstructive if thoracoabdominal movement was present and central if thoracoabdominal movement was absent). Hypopnea was defined as a reduction in airflow of >30% for ≥10 seconds and associated with a decrease in arterial oxygen saturation >4%. AHI was defined as the number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of total recording time. Recruited patients were categorized into OSA (AHI ≥15 events·h−1) and non‐OSA (AHI <15 events·h−1) groups. A minimum of 3 hours of satisfactory polygraphy signal recording was considered as a valid test. All studies were double scored manually by independent sleep technologists (J.F., X.W.). Further scoring was performed in cases of discrepancy by a senior consultant in sleep medicine (Y.W.).

Procedures and Management

All patients received standard care during index ACS hospitalization according to current guidelines.13, 14 PCI with stenting or coronary artery bypass grafting was performed if clinically indicated. At discharge, all patients were prescribed aspirin (100 mg per day) and clopidogrel (75 mg per day) or ticagrelor (90 mg twice a day) for at least 1 year unless there were contraindications. For patients with moderate‐to‐severe sleep apnea (AHI ≥15), particularly those with excessive daytime sleepiness, we referred them to a sleep center for further evaluation and consideration of CPAP therapy.

Follow‐up and Outcomes

Follow‐up started at the time of the sleep study and was performed at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and then every 6 months thereafter (at least 3 months and up to 2 years). Clinical events were collected by clinic visit, medical chart review, or telephone calls by an investigator who was blinded to patients’ sleep results. All clinical events were confirmed by source documentation and were adjudicated by the clinical event committee.

The primary end point was major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event (MACCE), defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, ischemia‐driven revascularization, or hospitalization for unstable angina or heart failure. Secondary end points included components of primary end point, all‐cause death, all repeat revascularization, and a composite of all events. All end points were defined in accord with the proposed definitions by the Standardized Data Collection for Cardiovascular Trials Initiative.17 Briefly, cardiovascular death was defined as death related to proximate cardiovascular causes, procedure‐related complications, or any death unless an unequivocal noncardiovascular cause could be established. MI was defined as recurrence of spontaneous ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction or non‐ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Stroke included ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke, which were verified by neurologists. Ischemia‐driven revascularization was defined as any repeat PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting performed for either: MI, unstable angina, stable angina, or documented silent ischemia. Repeat revascularization was further classified into target vessel or non‐target‐vessel revascularization as well as PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are shown as mean±SD or median (first and third quartiles) and were compared by using the Student t test or Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables are presented as the number (percentage) and were compared using χ2 statistics or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate.

Time‐to‐event data were summarized as Kaplan–Meier estimates and were compared by the log‐rank test. Multivariable Cox regression analyses were performed to determine independent predictors of MACCE and other cardiovascular events, and the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CI were calculated. Baseline variables that were considered clinically relevant or that showed a univariate relationship with outcome were entered into the Cox regression models. Variables for inclusion were carefully chosen, given the number of events available, to ensure parsimony of the final models. If the patient experienced more than 1 event during the follow‐up period, only the first event was included in the analysis. Landmark analyses were performed according to a cut‐off point of 1 year after sleep study, with HRs calculated separately for events that occurred within 1 year and those that occurred after 1 year.

All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS (version 22.0[ IBM SPSS Inc, Armonk, NY) and Stata software (version 11.2; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). A 2‐sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

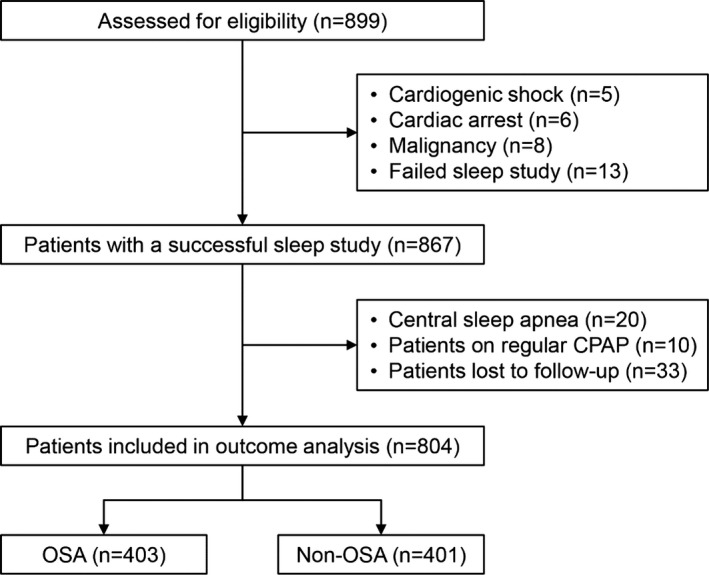

In total, 899 consecutive eligible patients with ACS were prospectively enrolled, of whom 867 underwent a successful overnight sleep study. After exclusion of patients according to predefined criteria, 804 patients were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Mean patient age was 57.5±10.2 years, and 82.6% were male. Patients with OSA had higher body mass index (P<0.001) and waist‐to‐hip ratio (P<0.001). Medical history was comparable between OSA and non‐OSA groups, except previous PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting, which was more frequent in the OSA group (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. CPAP indicates continuous positive airway pressure; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Variables | All (n=804) | OSA (n=403) | Non‐OSA (n=401) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y | 57.5±10.2 | 57.7±10.2 | 57.2±10.2 | 0.501 |

| Male | 664 (82.6) | 342 (84.9) | 322 (80.3) | 0.088 |

| Height, cm | 168.5±7.4 | 168.7±7.4 | 168.3±7.5 | 0.477 |

| Weight, kg | 76.0±12.2 | 78.8±12.4 | 73.0±11.3 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg·m−2 | 26.7±3.6 | 27.7±3.5 | 25.8±3.4 | <0.001 |

| Waist‐to‐hip ratio | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | <0.001 |

| Neck circumference, cm | 40 (38–42) | 41 (39–43) | 40 (37–41) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 125 (115–138) | 126 (115–140) | 125 (116–137) | 0.563 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 74 (70–84) | 75 (70–85) | 73 (68–82) | 0.012 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 248 (30.8) | 121 (30.0) | 127 (31.7) | 0.613 |

| Hypertension | 530 (65.9) | 275 (68.2) | 255 (63.6) | 0.165 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 210 (26.1) | 107 (26.6) | 103 (25.7) | 0.780 |

| Family history of premature CAD | 59 (7.3) | 28 (7.0) | 31 (7.1) | 0.700 |

| Previous stroke | 76 (9.5) | 41 (10.2) | 35 (8.7) | 0.484 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 118 (14.7) | 61 (15.1) | 57 (14.2) | 0.712 |

| Previous PCI | 141 (17.5) | 83 (20.6) | 58 (14.5) | 0.022 |

| Previous CABG | 11 (1.4) | 9 (2.2) | 2 (0.5) | 0.034 |

| Smoking | 0.973 | |||

| No | 288 (35.8) | 145 (36.0) | 143 (35.7) | |

| Current | 406 (50.5) | 202 (50.1) | 204 (50.9) | |

| Previous | 110 (13.7) | 56 (13.9) | 54 (13.5) | |

Data are presented as mean±SD, median (first quartile, third quartile), or n (%). BMI indicates body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

Results of Sleep Study

Median total recording time was 472 (405–536) minutes. AHI ranged from 0.0 to 97.9. Prevalence of OSA was 50.1% based on diagnostic criteria of AHI ≥15. Patients with OSA exhibited lower minimum oxygen saturation and excessive daytime sleepiness than those without OSA. Detailed information is described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of Sleep Study

| Variables | All (n=804) | OSA (n=403) | Non‐OSA (n=401) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI, events·h−1 | 15.0 (7.4–31.2) | 31.2 (21.8–43.8) | 7.4 (3.8–10.6) | <0.001 |

| ODI, events·h−1 | 14.4 (7.4–29.5) | 29.5 (21.2–43.3) | 7.8 (4.2–11.2) | <0.001 |

| Minimum SaO2, % | 85 (79–88) | 82 (75–86) | 87 (84–90) | <0.001 |

| Mean SaO2, % | 94 (93–95) | 93 (92–94) | 95 (94–96) | <0.001 |

| Time with SaO2 <90%, % | 1.2 (0.1–7.2) | 5.2 (1.2–13.4) | 0.2 (0.0–1.4) | <0.001 |

| Epworth sleepiness scale | 8.3±5.0 | 8.9±4.9 | 7.7±5.1 | 0.029 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or median (first quartile, third quartile). AHI indicates apnea‐hypopnea index; ODI, oxygen desaturation index; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

Procedures and Medications

Procedure and medication information is shown in Table 3. Most patients received invasive procedures, with coronary angiography in 97.8%. There were more PCIs (P=0.018) and stenting (P=0.029) procedures in patients with OSA than in those without OSA. Prescribed medications on discharge did not differ between the OSA and non‐OSA groups.

Table 3.

Clinical Presentations and Management

| Variables | All (n=804) | OSA (n=403) | Non‐OSA (n=401) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACS category | 0.214 | |||

| Unstable angina | 347 (43.2) | 179 (44.4) | 168 (41.9) | |

| NSTEMI | 203 (25.2) | 91 (22.6) | 112 (27.9) | |

| STEMI | 254 (31.6) | 133 (33.0) | 121 (30.2) | |

| LVEF, % | 60 (55–65) | 60 (55–65) | 60 (55–65) | 0.277 |

| Coronary angiography | 786 (97.8) | 397 (98.5) | 389 (97.0) | 0.150 |

| PCI | 490 (60.9) | 262 (65.0) | 228 (56.9) | 0.018 |

| Stenting | 432 (53.7) | 232 (57.6) | 200 (49.9) | 0.029 |

| Stents implanted, n | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.497 |

| CABG | 80 (10.0) | 37 (9.2) | 43 (10.7) | 0.465 |

| Medications on discharge | ||||

| Aspirin | 754 (93.8) | 381 (94.5) | 373 (93.0) | 0.371 |

| Thienopyridine | 720 (89.6) | 369 (91.6) | 351 (87.5) | 0.062 |

| β‐blockers | 611 (76.0) | 313 (77.7) | 298 (74.3) | 0.266 |

| ACEIs/ARBs | 564 (70.1) | 291 (72.2) | 273 (68.1) | 0.201 |

| Statins | 762 (94.8) | 385 (95.5) | 377 (94.0) | 0.333 |

| Aldosterone receptor antagonist | 47 (5.8) | 28 (6.9) | 19 (4.7) | 0.182 |

| Diuretics | 56 (7.0) | 34 (8.4) | 22 (5.5) | 0.100 |

| Calcium antagonists | 124 (15.4) | 65 (16.1) | 59 (14.7) | 0.578 |

Data are presented as median (first quartile, third quartile) or n (%). ACEIs indicates angiotensin‐converting enzymes inhibitors; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NSTEMI, non‐ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment‐elevation myocardial infarction.

Primary End Point

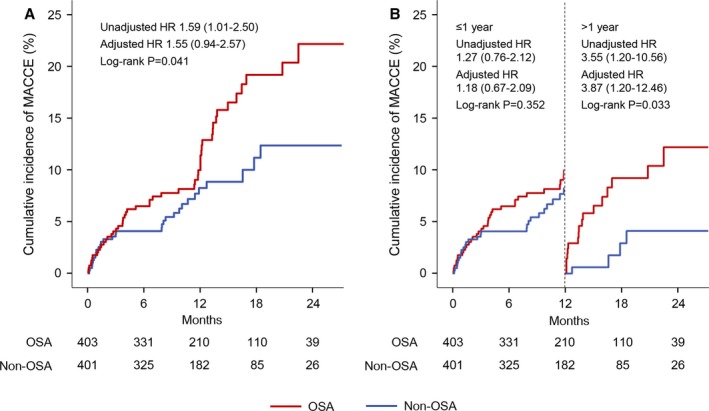

During a median follow‐up of 1 year (0.7–1.7), 81 (10.1%) patients had MACCE—51 (12.7%) in the OSA group and 30 (7.5%) in the non‐OSA group (Table 4). Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that cumulative incidence of MACCE was significantly higher in the OSA group than in the non‐OSA group (log‐rank, P=0.041; Figure 2A). OSA predicted incidence of MACCE in unadjusted analysis (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.01–2.50; P=0.043; Table 5). After adjustment for age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, clinical presentation, PCI procedure, and minimum arterial oxygen saturation, presence of OSA was nominally associated with incidence of MACCE, but this fell short of statistical significance (HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 0.94–2.57; P=0.085; Table 5).

Table 4.

Crude Number of Events During Follow‐up

| Variables | All (n=804) | OSA (n=403) | Non‐OSA (n=401) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACCE | 81 (10.1) | 51 (12.7) | 30 (7.5) |

| Cardiovascular death | 11 (1.4) | 5 (1.2) | 6 (1.5) |

| Myocardial infarction | 11 (1.4) | 4 (1.0) | 7 (1.7) |

| Stroke | 9 (1.1) | 6 (1.5) | 3 (0.7) |

| Ischemic | 6 (1.0) | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| Hemorrhagic | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Hospitalization for unstable angina | 49 (6.1) | 33 (8.2) | 16 (4.0) |

| Hospitalization for heart failure | 6 (0.7) | 3 (0.7) | 3 (0.7) |

| Ischemia‐driven revascularization | 27 (3.4) | 17 (4.2) | 10 (2.5) |

| All‐cause mortality | 11 (1.4) | 5 (1.2) | 6 (1.5) |

| All repeat revascularization | 48 (6.0) | 28 (6.9) | 20 (5.0) |

| Target vessel revascularization | 14 (1.7) | 9 (2.2) | 5 (1.2) |

| Non‐target‐vessel revascularization | 40 (5.0) | 23 (5.7) | 17 (4.2) |

| PCI | 42 (5.2) | 26 (6.5) | 16 (4.0) |

| CABG | 6 (0.7) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (1.0) |

| Composite of all events | 100 (12.4) | 61 (15.1) | 39 (9.7) |

Data are presented as n (%). CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; MACCE major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the overall and landmark analysis of MACCE. Cumulative incidences of MACCE are shown in the overall (A) and landmark (B) analysis, stratified on the basis of a cut‐off point at 1 year after sleep study (vertical dashed line). HRs for OSA vs non‐OSA groups were calculated separately for events that occurred within 1 year and those that occurred between 1 year and the end of follow‐up. HR indicates hazard ratio; MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

Table 5.

Overall and Landmark Analysis for the Adverse Events in Patients With OSA Versus Those Without OSA

| Variables | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall analysis | ||||

| MACCE | 1.59 (1.01–2.50) | 0.043 | 1.55 (0.94–2.57) | 0.085 |

| Cardiovascular death† | 0.80 (0.25–2.63) | 0.716 | ··· | ··· |

| Myocardial infarction† | 0.54 (0.16–1.85) | 0.327 | ··· | ··· |

| Stroke† | 1.93 (0.48–7.71) | 0.353 | ··· | ··· |

| Ischemia‐driven revascularization | 1.57 (0.72–3.42) | 0.261 | 1.52 (0.65–3.56) | 0.334 |

| Hospitalization for unstable angina | 1.89 (1.04–3.44) | 0.036 | 2.10 (1.09–4.05) | 0.027 |

| Hospitalization for heart failure† | 0.97 (0.20–4.81) | 0.972 | ··· | ··· |

| All repeat revascularization | 1.32 (0.75–2.35) | 0.340 | 1.51 (0.81–2.83) | 0.195 |

| Composite of all events | 1.48 (0.99–2.21) | 0.057 | 1.54 (0.98–2.40) | 0.059 |

| Landmark analysis (≤1 y) | ||||

| MACCE | 1.27 (0.76–2.12) | 0.353 | 1.18 (0.67–2.09) | 0.575 |

| Hospitalization for unstable angina | 1.62 (0.79–3.31) | 0.187 | 1.84 (0.84–4.03) | 0.130 |

| Ischemic‐driven revascularization | 1.21 (0.48–3.07) | 0.688 | 1.27 (0.46–3.50) | 0.646 |

| All repeat revascularization | 1.14 (0.61–2.14) | 0.682 | 1.41 (0.71–2.82) | 0.328 |

| Composite of all events | 1.26 (0.81–1.96) | 0.310 | 1.28 (0.78–2.09) | 0.322 |

| Landmark analysis (>1 y) | ||||

| MACCE | 3.55 (1.20–10.56) | 0.023 | 3.87 (1.20–12.46) | 0.023 |

| Hospitalization for unstable angina | 2.68 (0.87–8.21) | 0.085 | 2.82 (0.84–9.51) | 0.095 |

| Ischemic‐driven revascularization | 2.92 (0.61–14.04) | 0.182 | 2.46 (0.46–13.26) | 0.295 |

| All repeat revascularization | 2.85 (0.59–13.71) | 0.192 | 2.54 (0.47–13.73) | 0.278 |

| Composite of all events | 3.30 (1.10–9.86) | 0.033 | 3.67 (1.13–11.95) | 0.031 |

HR indicates hazard ratio; MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Model adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, clinical presentation (acute myocardial infarction vs unstable angina), PCI procedure, and minimum SaO2.

Multivariate Cox regression and landmark analysis was not done because of too few events.

In the landmark analysis (Figure 2B and Table 5), there was no significant difference in the incidence of MACCE between the OSA and non‐OSA groups within 1‐year follow‐up (adjusted HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.67–2.09; P=0.575). In contrast, during the period after 1 year, patients with OSA had a 3.9‐fold higher risk of MACCE (adjusted HR, 3.87; 95% CI, 1.20–12.46; P=0.023).

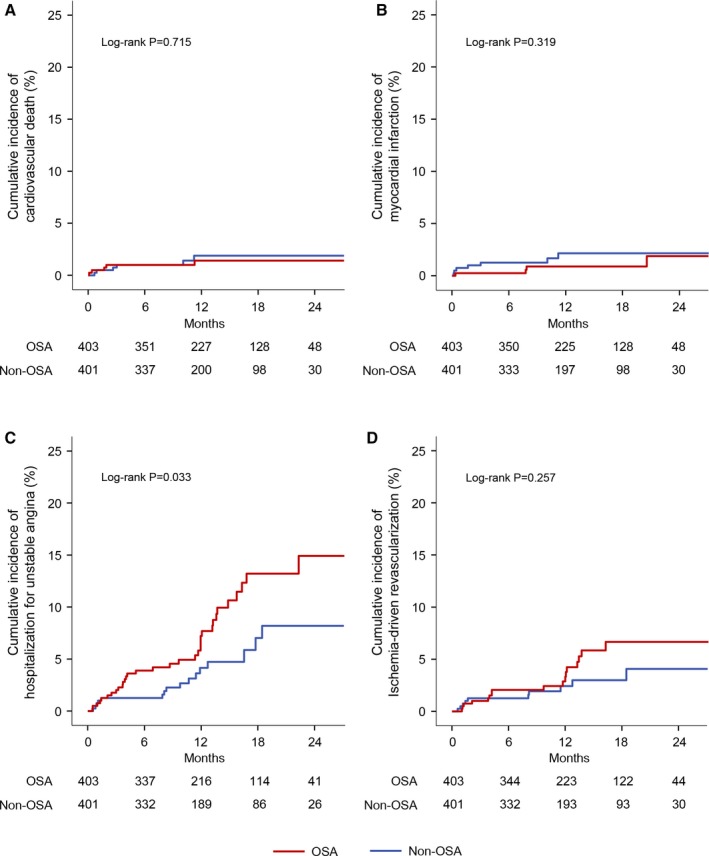

Secondary and Other End Points

Crude numbers of events are listed in Table 4. In general, most events came from hospitalization for unstable angina or ischemia‐driven revascularization. In Kaplan–Meier analyses, no significant differences were found in the incidence of cardiovascular death, MI, and ischemia‐driven revascularization, except for a higher rate of hospitalization for unstable angina in the OSA group than in the non‐OSA group (log‐rank, P=0.033; Figure 3). Similarly, multivariate analysis showed higher risk of unstable angina in patients with OSA compared with those without OSA (HR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.09–4.05; P=0.027; Table 5). Moreover, incidence of all events was significantly higher in the OSA group than in the non‐OSA group in the landmark analysis after 1 year (adjusted HR, 3.67; 95% CI, 1.13–11.95; P=0.031; Table 5).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the individual cardiovascular events. Shown are the cumulative incidences of cardiovascular death (A), myocardial infarction (B), hospitalization for unstable angina (C), and ischemia‐driven revascularization (D). OSA indicates obstructive sleep apnea.

Discussion

The prospective cohort study showed that OSA was nominally associated with increased incidence of MACCE in patients with ACS. However, multivariable analysis showed that there was no independent correlation between OSA and 1‐year MACCE after ACS. The difference between the 2 groups was driven by an increase of hospitalizations for unstable angina in the OSA group. In the landmark analysis, patients with OSA had 3.9 times the risk of incurring a MACCE after 1 year, but no increased risk was evident within 1 year, suggesting that the adverse effect of OSA might become more pronounced with an increasing duration of follow‐up.

Despite therapeutic advances, including greater use of reperfusion therapy and modern antithrombotic therapy, mortality following ACS remains substantial. In the national registries of the European Society of Cardiology countries, in‐hospital mortality of ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction patients varies between 4% and 12%,18 and reported 1‐year mortality among ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction patients in angiography registries is ≈10%.19, 20 Consequently, it is important to identify potential factors that might contribute to worsening of clinical outcomes in patients with ACS.

OSA‐mediated intermittent hypoxia, triggered by repetitive bursts of apneas and hypopneas, is a major contributing factor to cardiovascular impairment.21 Recurrent cycles of hypoxemia with reoxygenation promote oxidative stress, sympathetic activation, and inflammatory responses, resulting in endothelial dysfunction21 and reduction of repair capacity,22 which exacerbate progression of atherosclerosis and plaque instability. Based on intravascular ultrasound, patients with OSA had a larger total atheroma volume than those without OSA.4 In a large ACS cohort study, OSA was associated with an increased number of diseased vessels.23 In our study, there were more PCI procedures in OSA patients. In addition, patients with OSA showed increased platelet activation and aggregation24 and reduced fibrinolytic capacity,25 all of which predispose to thrombotic events. Several observational studies and meta‐analysis have shown a higher risk of long‐term cardiovascular events in patients with OSA,9, 10, 11, 12, 26 but most studies were done in the era before new‐generation drug‐eluting stents and potent antiplatelet therapy. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is 1 of the largest cohorts to examine impact of OSA on cardiovascular outcomes of ACS patients in the contemporary era. Our results demonstrate that patients with OSA might have a greater risk of MACCE after ACS onset, even if most patients have received revascularization and optimal medical therapy.

Specifically, our results indicate that increased risk in OSA patients was obvious only after 1 year. This may be explained by the fact that patients are under guideline‐based therapy after ACS presentation (especially within 1 year), including intensive antiplatelet therapy and control of blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and glucose, which are also the intermediate mechanisms implicated in OSA.2 Furthermore, some reports suggested that OSA may play a cardioprotective role in the acute phase of MI.27 In contrast, OSA may have a chronic deleterious effect in the long run, which was verified in our study showing increased events after 1 year, consistent with previous studies with long‐term follow‐up.9, 28

According to recent randomized trials and meta‐analysis, treatment of OSA with CPAP may not confer significant cardiovascular benefit among patients with established cardiovascular disease.29, 30, 31 In a trial that enrolled 224 patients with OSA and coronary artery disease who had undergone revascularization, no difference was found in a composite end point of repeat revascularization, MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death in patients with CPAP versus those without CPAP therapy. The Kaplan–Meier curve suggests that CPAP may be harmful in the first 12 months following randomization, and modest benefits may emerge in the long‐term follow‐up.29 Specifically, despite recommendations for treatment, the vast majority of patients in our study did not proceed to consideration for CPAP therapy because of unawareness of significance of OSA, a finding also observed in another study of OSA patients after MI.32 In this case, treatment effects of CPAP for secondary prevention of coronary artery disease still need to be evaluated, especially in a high‐risk group (ACS, MI, etc). Also, the appropriate duration of intervention warrants further investigation, given that any randomized trial of CPAP or other therapy for 1 year or less will be unlikely to demonstrate significant benefit of therapy, given the absence of significant risk associated with OSA within the first year of ACS.

Study Limitations

First, OSA was detected by cardiorespiratory monitoring rather than complete polysomnography. Although the portable devices may underestimate AHI as a consequence of overestimating actual sleeping time, it is a simple and safe way to identify OSA in this high‐risk patient population. Second, whereas it is possible that severity of OSA may change in the weeks after ACS,33 this is true for OSA evaluation in the setting of any acute disease, including heart failure. Also, patients in our study received a sleep study after clinical stabilization, thus minimizing the potential bias. Third, follow‐up duration was relatively shorter. Also, a previous study indicated that nocturnal hypoxemia in OSA is a predictor of poor outcome after MI in the long run.32 Therefore, longer follow‐up of this cohort is needed. Finally, this study is a single‐center study that recruited primarily East‐Asian patients. Studies pertaining to other ethnicities are needed.

Conclusions

In this prospective cohort study, OSA was not independently associated with a higher incidence of MACCE in patients with ACS. However, an increased risk associated with OSA was observed during the period after 1 year. Efficacy of CPAP therapy for secondary prevention and timing of intervention after ACS need further evaluation.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grants from the International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of China (2015DFA30160), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81600209, 81870322), Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (ZYLX201710), Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals’ Ascent Plan (DFL20180601), Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (Z181100001718060), Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals’ Youth Program (QML20160605), and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Incubating Program (PX2016048).

Disclosures

Dr Somers served as a consultant for Phillips Respironics, ResMed, Respicardia, GlaxoSmithKline, Itamar, U‐Health, and Bayer. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Qiuju Deng (Department of Epidemiology, Beijing Institute of Heart Lung and Blood Vessel Diseases, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China) for her help in statistics and also thank Drs Wen Hao, Guanqi Zhao, Shenghui Zhou, Aobo Li, Ruifeng Guo, Han Shi, and Zexuan Li (Emergency & Critical Care Center, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China) for collecting the data involved in this study.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e010826 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010826.)

Contributor Information

Shaoping Nie, Email: spnie@ccmu.edu.cn.

Yongxiang Wei, Email: weiyongxiang@vip.sina.com.

References

- 1. Javaheri S, Barbe F, Campos‐Rodriguez F, Dempsey JA, Khayat R, Javaheri S, Malhotra A, Martinez‐Garcia MA, Mehra R, Pack AI, Polotsky VY, Redline S, Somers VK. Sleep apnea: types, mechanisms, and clinical cardiovascular consequences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:841–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Drager LF, McEvoy RD, Barbe F, Lorenzi‐Filho G, Redline S; INCOSACT Initiative (International Collaboration of Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Trialists) . Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: lessons from recent trials and need for team science. Circulation. 2017;136:1840–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weinreich G, Wessendorf TE, Erdmann T, Moebus S, Dragano N, Lehmann N, Stang A, Roggenbuck U, Bauer M, Jockel KH, Erbel R, Teschler H, Mohlenkamp S. Association of obstructive sleep apnoea with subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231:191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tan A, Hau W, Ho HH, Ghaem Maralani H, Loo G, Khoo SM, Tai BC, Richards AM, Ong P, Lee CH. OSA and coronary plaque characteristics. Chest. 2014;145:322–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arzt M, Hetzenecker A, Steiner S, Buchner S. Sleep‐disordered breathing and coronary artery disease. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martinez‐Garcia MA, Campos‐Rodriguez F, Soler‐Cataluna JJ, Catalan‐Serra P, Roman‐Sanchez P, Montserrat JM. Increased incidence of nonfatal cardiovascular events in stroke patients with sleep apnoea: effect of CPAP treatment. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Giustino G, Baber U, Stefanini GG, Aquino M, Stone GW, Sartori S, Steg PG, Wijns W, Smits PC, Jeger RV, Leon MB, Windecker S, Serruys PW, Morice MC, Camenzind E, Weisz G, Kandzari D, Dangas GD, Mastoris I, Von Birgelen C, Galatius S, Kimura T, Mikhail G, Itchhaporia D, Mehta L, Ortega R, Kim HS, Valgimigli M, Kastrati A, Chieffo A, Mehran R. Impact of clinical presentation (stable angina pectoris vs unstable angina pectoris or non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction vs ST‐elevation myocardial infarction) on long‐term outcomes in women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with drug‐eluting stents. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koo CY, de la Torre AS, Loo G, Torre MS, Zhang J, Duran‐Cantolla J, Li R, Mayos M, Sethi R, Abad J, Furlan SF, Coloma R, Hein T, Ho HH, Jim MH, Ong TH, Tai BC, Turino C, Drager LF, Lee CH, Barbe F. Effects of ethnicity on the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a pooled analysis of the ISAACC Trial and Sleep and Stent Study. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;26:486–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mazaki T, Kasai T, Yokoi H, Kuramitsu S, Yamaji K, Morinaga T, Masuda H, Shirai S, Ando K. Impact of sleep‐disordered breathing on long‐term outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome who have undergone primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003270 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Meng S, Fang L, Wang CQ, Wang LS, Chen MT, Huang XH. Impact of obstructive sleep apnoea on clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome following percutaneous coronary intervention. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:1343–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yumino D, Tsurumi Y, Takagi A, Suzuki K, Kasanuki H. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on clinical and angiographic outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee CH, Sethi R, Li R, Ho HH, Hein T, Jim MH, Loo G, Koo CY, Gao XF, Chandra S, Yang XX, Furlan SF, Ge Z, Mundhekar A, Zhang WW, Uchoa CH, Kharwar RB, Chan PF, Chen SL, Chan MY, Richards AM, Tan HC, Ong TH, Roldan G, Tai BC, Drager LF, Zhang JJ. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2016;133:2008–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli‐Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimsky P. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, Gencer B, Hasenfuss G, Kjeldsen K, Lancellotti P, Landmesser U, Mehilli J, Mukherjee D, Storey RF, Windecker S, Baumgartner H, Gaemperli O, Achenbach S, Agewall S, Badimon L, Baigent C, Bueno H, Bugiardini R, Carerj S, Casselman F, Cuisset T, Erol C, Fitzsimons D, Halle M, Hamm C, Hildick‐Smith D, Huber K, Iliodromitis E, James S, Lewis BS, Lip GY, Piepoli MF, Richter D, Rosemann T, Sechtem U, Steg PG, Vrints C, Luis Zamorano J. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation: Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Antic NA, Heeley E, Anderson CS, Luo Y, Wang J, Neal B, Grunstein R, Barbe F, Lorenzi‐Filho G, Huang S, Redline S, Zhong N, McEvoy RD. The Sleep Apnea cardioVascular Endpoints (SAVE) Trial: rationale, ethics, design, and progress. Sleep. 2015;38:1247–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gantner D, Ge JY, Li LH, Antic N, Windler S, Wong K, Heeley E, Huang SG, Cui P, Anderson C, Wang JG, McEvoy D. Diagnostic accuracy of a questionnaire and simple home monitoring device in detecting obstructive sleep apnoea in a Chinese population at high cardiovascular risk. Respirology. 2010;15:952–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, Chaitman BR, Cutlip DE, Farb A, Fonarow GC, Jacobs JP, Jaff MR, Lichtman JH, Limacher MC, Mahaffey KW, Mehran R, Nissen SE, Smith EE, Targum SL. 2014 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Cardiovascular Endpoints Data Standards). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:403–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kristensen SD, Laut KG, Fajadet J, Kaifoszova Z, Kala P, Di Mario C, Wijns W, Clemmensen P, Agladze V, Antoniades L, Alhabib KF, De Boer MJ, Claeys MJ, Deleanu D, Dudek D, Erglis A, Gilard M, Goktekin O, Guagliumi G, Gudnason T, Hansen KW, Huber K, James S, Janota T, Jennings S, Kajander O, Kanakakis J, Karamfiloff KK, Kedev S, Kornowski R, Ludman PF, Merkely B, Milicic D, Najafov R, Nicolini FA, Noc M, Ostojic M, Pereira H, Radovanovic D, Sabate M, Sobhy M, Sokolov M, Studencan M, Terzic I, Wahler S, Widimsky P; European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions . Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction 2010/2011: current status in 37 ESC countries. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1957–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pedersen F, Butrymovich V, Kelbaek H, Wachtell K, Helqvist S, Kastrup J, Holmvang L, Clemmensen P, Engstrom T, Grande P, Saunamaki K, Jorgensen E. Short‐ and long‐term cause of death in patients treated with primary PCI for STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2101–2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fokkema ML, James SK, Albertsson P, Akerblom A, Calais F, Eriksson P, Jensen J, Nilsson T, de Smet BJ, Sjogren I, Thorvinger B, Lagerqvist B. Population trends in percutaneous coronary intervention: 20‐year results from the SCAAR (Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1222–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dewan NA, Nieto FJ, Somers VK. Intermittent hypoxemia and OSA: implications for comorbidities. Chest. 2015;147:266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jelic S, Padeletti M, Kawut SM, Higgins C, Canfield SM, Onat D, Colombo PC, Basner RC, Factor P, LeJemtel TH. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and repair capacity of the vascular endothelium in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 2008;117:2270–2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barbe F, Sanchez‐de‐la‐Torre A, Abad J, Duran‐Cantolla J, Mediano O, Amilibia J, Masdeu MJ, Flores M, Barcelo A, de la Pena M, Aldoma A, Worner F, Valls J, Castella G, Sanchez‐de‐la‐Torre M; Spanish Sleep Network . Effect of obstructive sleep apnoea on severity and short‐term prognosis of acute coronary syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bokinsky G, Miller M, Ault K, Husband P, Mitchell J. Spontaneous platelet activation and aggregation during obstructive sleep apnea and its response to therapy with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. A preliminary investigation. Chest. 1995;108:625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rangemark C, Hedner JA, Carlson JT, Gleerup G, Winther K. Platelet function and fibrinolytic activity in hypertensive and normotensive sleep apnea patients. Sleep. 1995;18:188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang X, Fan JY, Zhang Y, Nie SP, Wei YX. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with cardiovascular outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mohananey D, Villablanca PA, Gupta T, Agrawal S, Faulx M, Menon V, Kapadia SR, Griffin BP, Ellis SG, Desai MY. Recognized obstructive sleep apnea is associated with improved in‐hospital outcomes after ST elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006133 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Uchoa CHG, Pedrosa RP, Javaheri S, Geovanini GR, Carvalho MMB, Torquatro ACS, Leite A, Gonzaga CC, Bertolami A, Amodeo C, Petisco A, Barbosa JEM, Macedo TA, Bortolotto LA, Oliveira MT Jr, Lorenzi‐Filho G, Drager LF. OSA and prognosis after acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema: the OSA‐CARE study. Chest. 2017;152:1230–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peker Y, Glantz H, Eulenburg C, Wegscheider K, Herlitz J, Thunstrom E. Effect of positive airway pressure on cardiovascular outcomes in coronary artery disease patients with nonsleepy obstructive sleep apnea. The RICCADSA randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, Luo Y, Ou Q, Zhang X, Mediano O, Chen R, Drager LF, Liu Z, Chen G, Du B, McArdle N, Mukherjee S, Tripathi M, Billot L, Li Q, Lorenzi‐Filho G, Barbe F, Redline S, Wang J, Arima H, Neal B, White DP, Grunstein RR, Zhong N, Anderson CS; SAVE Investigators and Coordinators. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:919–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang X, Zhang Y, Dong Z, Fan J, Nie S, Wei Y. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on long‐term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease and obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Respir Res. 2018;19:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xie J, Sert Kuniyoshi FH, Covassin N, Singh P, Gami AS, Wang S, Chahal CA, Wei Y, Somers VK. Nocturnal hypoxemia due to obstructive sleep apnea is an independent predictor of poor prognosis after myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003162 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.115.003162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Low TT, Hong WZ, Tai BC, Hein T, Khoo SM, Tan AY, Chan MY, Richards M, Lee CH. The influence of timing of polysomnography on diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction and stable coronary artery disease. Sleep Med. 2013;14:985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]