Abstract

Background

Octogenarians have low physiologic reserve and may benefit more from transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) than surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).

Methods and Results

This retrospective cohort study based on the National Inpatient Sample included octogenarians who underwent TAVR or SAVR from 2012 to 2015. Crude and standardized‐morbidity‐ratio‐weighted regression models were used to compare in‐hospital outcomes. Among 19 145 TAVR and 9815 SAVR hospitalizations, TAVR patients had higher Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores (2.0 versus 0.8, P<0.0001) than SAVR patients. Before weighting, TAVR was associated with significantly shorter length of stay, more home discharges, and lower incidences of acute kidney injury, bleeding, and cardiogenic shock. Associations were consistent across Charlson Comorbidity Index, except for TAVR being associated with greater length of stay reductions among patients with Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥2, compared with Charlson Comorbidity Index <2 (change in estimate −3.56 versus −2.61 days, P=0.004). After weighting, TAVR patients had significantly shorter length of stay (change in estimate −3.29 days, 95% CI −3.82, −2.75) and lower odds of transfer to skilled nursing facility (odds ratio 0.34, 95% CI 0.29, 0.41), acute kidney injury (odds ratio 0.55, 95% CI 0.45, 0.68), bleeding (odds ratio 0.44, 95% CI 0.37, 0.53), and cardiogenic shock (odds ratio 0.55, 95% CI 0.33, 0.92), compared with SAVR patients. Odds of permanent pacemaker implantation, transient ischemic attack/stroke, vascular complications, and in‐hospital mortality were not significantly different.

Conclusions

TAVR may be preferred over SAVR in high‐risk octogenarians because of shorter length of stay, better discharge disposition, and less acute kidney injury, and bleeding. All octogenarians may benefit more from TAVR, irrespective of comorbidity burden, but additional research is needed to confirm our findings.

Keywords: aortic stenosis, complication, mortality, octogenarians, transcatheter aortic valve implantation

Subject Categories: Aortic Valve Replacement/Transcather Aortic Valve Implantation, Mortality/Survival, Complications, Catheter-Based Coronary and Valvular Interventions, Quality and Outcomes

Short abstract

See Editorial by Himbert et al

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

In this propensity score weighted analysis of nationally representative data, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) was associated with a significant reduction in length of stay and lower odds of transfer to skilled nursing facility, acute kidney injury, bleeding, and cardiogenic shock, compared with if surgical aortic valve replacement was performed in high‐risk octogenarians.

Odds of permanent pacemaker implantation, vascular complications, transient ischemic attack/stroke, and in‐hospital mortality did not significantly differ between groups.

Advantages of TAVR over surgical aortic valve replacement were consistent between those with low and high comorbidity burden, except for greater reductions in length of stay in the latter group.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

While TAVR and surgical aortic valve replacement are both reasonable options in high‐risk patients, these results show that TAVR offers more benefits and may be the preferred approach in high‐risk octogenarians, which is a population with low physiologic reserve and frailty.

The benefits of TAVR extend to all octogenarians, irrespective of comorbidity burden.

Introduction

Calcific aortic stenosis (AS) is primarily associated with advanced age and affects ≈10% of octogenarians.1, 2 According to the US Census Bureau, the octogenarian population is projected to double from 2020 to 2040.3 Consequently, a proportional increase in the incidence of AS may also be expected. Before the advent of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) was the only definitive treatment for AS but a substantial proportion of octogenarians with severe symptomatic disease could not receive the procedure because of prohibitive surgical risk.4 Since first introduced as a modality for prohibitive and high surgical‐risk patients, TAVR is now established as an option for intermediate surgical‐risk patients, with randomized controlled trials ongoing in low surgical‐risk patients.5, 6, 7, 8 However, patients aged ≥80 years have low physiologic reserve and have been classified by gerontologists as the “very old.”9 Therefore, the true surgical risk in octogenarians may be underestimated by traditional surgical‐risk scores, even for those with few co‐morbidities.

There are limited studies comparing outcomes of TAVR versus SAVR specifically in octogenarians. One single center study showed that octogenarians receiving TAVR had shorter length of stay (LOS) than those receiving SAVR, with comparable operative mortality between groups.10 Although nationally representative data have been used to compare in‐hospital outcomes after TAVR and SAVR in the United States, no study has been performed specifically in octogenarians.11 As such, we sought to evaluate TAVR and SAVR use, in‐hospital complications, LOS, and discharge disposition (including mortality) in octogenarians using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS).

Methods

Study Design and Population

NIS is the largest all‐payer database of hospitalizations in the United States and represents a 20% stratified random sample of all hospital discharges nationwide.12 The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) diagnostic and procedural codes were used to identify the study population. Institutional review board approval was not required since NIS contains de‐identified patient information.

Hospitalizations of adults between ages 80 and 89 years with aortic valve disorders (ICD‐9‐CM 424.1) who underwent either elective TAVR (35.05 and 35.06) or SAVR (35.21 and 35.22) between January 1, 2012 and September 30, 2015, which was chosen as the cutoff date because of ICD‐10‐CM implementation, were eligible for inclusion. To limit the analysis to elective procedures, those occurring >2 days after admission were excluded. Patients who underwent concomitant procedures involving the coronary vessels (00.61–00.69 and 36.00–36.99), were discharged against medical advice or had unknown discharge disposition, or had a history of congenital aortic valve stenosis (746.3), rheumatic aortic stenosis (395.0–395.9), or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (425.11) were also excluded. Additionally, patients who underwent SAVR at non‐TAVR centers were excluded. TAVR centers were defined as any hospital performing at least 1 TAVR (irrespective of inclusion/exclusion criteria for the current study) during the year of surgery.

Covariates and Outcomes

Baseline patient characteristics evaluated were age, sex, race/ethnicity, primary insurance coverage, median household income of the patient's ZIP code, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which was determined using the Deyo et al coding scheme.13 Hospital characteristics, including geographic region, type (rural non‐teaching, urban non‐teaching, or urban teaching), and size (small, medium, or large) were also included.

Outcomes of interest were in‐hospital complications (permanent pacemaker [PPM] implantation, acute kidney injury [AKI], transient ischemic attack or stroke [TIA/stroke], cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, bleeding, blood transfusions, and vascular complications), LOS after aortic valve replacement, and discharge disposition. ICD‐9‐CM codes used to identify complications are listed in Table S1. Discharge disposition was categorized as home discharge, which included those with home health care, transfer to short‐term hospital, transfer to skilled nursing or intermediate care facility, or death.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline differences between TAVR and SAVR hospitalizations were compared using simple linear regression and Rao‐Scott Chi‐square tests, as appropriate, while accounting for the complex sampling design and clustering within hospitals. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The quarterly rates of TAVR and SAVR procedures per 100 aortic valve replacements were estimated using Poisson regression, and changes in rates over time were evaluated using likelihood ratio tests. Additional trend tests were performed to assess temporal changes for in‐hospital complications, LOS, and discharge disposition, stratified by procedure type. Logistic and linear regressions—where appropriate—were used to assess whether the association of TAVR, compared with SAVR, on in‐hospital complications, LOS after valve replacement, and discharge disposition was differential across CCI (categorized as <2 and ≥2). Interaction terms were used to assess significant effect modification by CCI.

A propensity score weighted analysis was performed to account for potential confounding.14 These propensity scores (PS) characterized the probability of each patient undergoing TAVR, compared with SAVR, and were estimated using multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for year, age, sex, race/ethnicity, the individual CCI components, primary insurance coverage, median household income, and hospital region, type, and size, as well as accounting for sampling strategy and clustering. Age was modeled as a restricted cubic spline, which allows for the greatest flexibility and requires the fewest assumptions when modeling continuous variables. Since propensity scores could not be estimated for patients with missing data on any of the above variables, those patients were excluded from the weighted analyses. Trimming was performed at the 1st percentile of TAVR propensity scores and the 99th percentile of SAVR propensity scores to remove non‐overlapping regions of the propensity score distributions. This step was necessary since those patients either represent TAVR patients who always undergo TAVR or SAVR patients who always undergo SAVR, and neither group is at risk for undergoing the other procedure.14

A standardized morbidity ratio (SMR) weight was calculated. Those undergoing TAVR were assigned a weight of 1, and those undergoing SAVR were assigned a weight of PS/(1−PS). Applying SMR weights in this manner standardizes the distribution of measured baseline patient and hospital characteristics in SAVR hospitalizations to the distribution observed in TAVR hospitalizations, which represented a high‐risk population given TAVR indications from 2012 to 2015. This technique assesses the effect of TAVR, compared with the effect of SAVR, among high‐risk patients without needing to measure risk levels directly. These SMR weights were then multiplied with the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project discharge weights to create a final weight for each hospitalization.

Both crude and SMR‐weighted logistic regression, linear regression, and generalized logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds of each in‐hospital complication, average LOS, and the odds of each discharge disposition, respectively, following TAVR, compared with if SAVR was performed (again, sampling and clustering was accounted for). Similar standardized models were used to assess the effects of transapical TAVR (35.06) and endovascular TAVR (35.05) separately, compared with the effects of SAVR, among patients who had undergone TAVR. Finally, the effect of TAVR, compared with if they had undergone SAVR, were compared among patients who underwent SAVR (which represents an all‐risk, and lower risk, patient population), to estimate the effect of treating all AS patients with TAVR. For this analysis, SAVR patients were given a weight of 1 and TAVR patients were weighted as (1−PS)/PS using the same score described above.

Confidence intervals for both the crude and weighted effect estimates were calculated using non‐parametric bootstraps, which accounted for SMR weighting in the standardized models and ensured that unbiased estimates of the standard deviations were obtained. Specifically, the standard deviation for each effect was estimated using 500 resamples with replacement. The design and analysis of this study adhered to best practices for research using the National Inpatient Sample.15 All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC), and survey procedures were used (PROC SURVEYMEANS, SURVEYFREQ, SURVEYREG, and SURVEYLOGISTIC).

Results

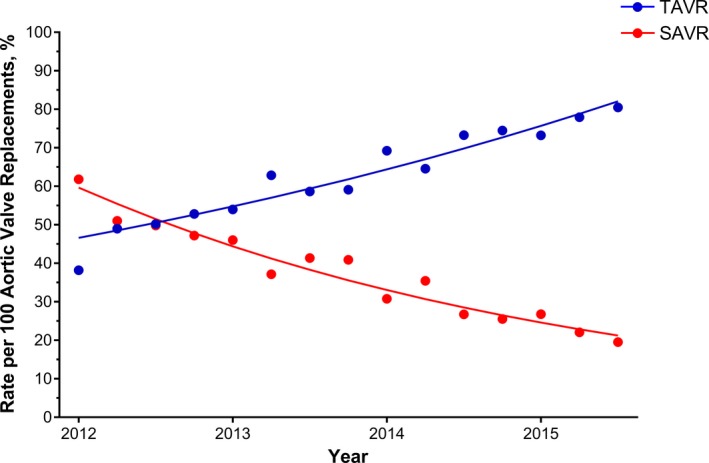

There were an estimated 28 960 hospitalizations (19 145 TAVR, 9815 SAVR) for elective aortic valve replacement in octogenarians between 2012 and 2015. An endovascular approach was used in 16 230 (85%) TAVR cases, and a transapical approach was used in 2915 (15%) cases. The rate of TAVR per 100 aortic valve replacements in octogenarians grew from 48% in 2012 to 78% in 2015, marking a statistically significant increase over time (P<0.0001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Quarterly rate of TAVR and SAVR, per 100 aortic valve replacements, in hospitalizations of octogenarians at TAVR‐performing hospitals. SAVR indicates surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

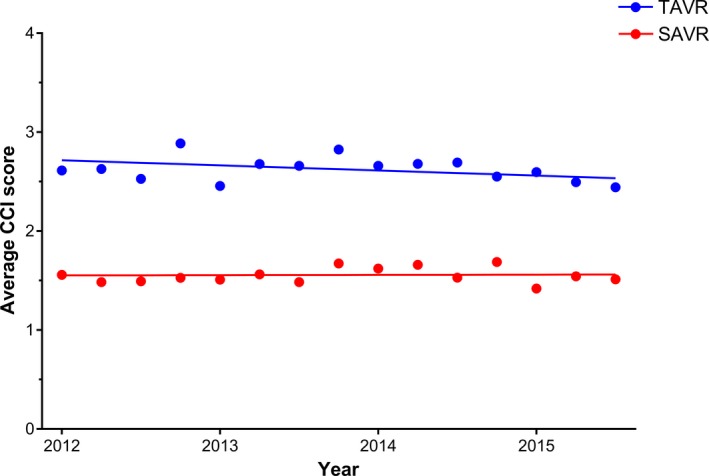

Octogenarians who underwent TAVR were older (84 years versus 82 years, P<0.0001) and had higher median CCI score (2.0 versus 0.8, P<0.0001) compared with those who underwent SAVR (Table 1). From 2012 to 2015, the mean CCI score was relatively consistent among patients with TAVR (2.6 in 2012 versus 2.5 in 2015) and SAVR (1.6 versus 1.5) (Figure 2). TAVR hospitalizations were more likely to occur at urban teaching hospitals (89% versus 86%, P=0.004) and in the South (33% versus 25%, P<0.0001) than SAVR hospitalizations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Hospitalizations of Octogenarians Undergoing Aortic Valve Replacement Between 2012 and 2015, Stratified by Procedure Type

| TAVR 19 145 (66%) | SAVR 9815 (34%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 84 (82–87) | 82 (81–84) | <0.0001a |

| Male, n (%) | 9020 (47) | 5402 (55) | 0.09 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 16 120 (90) | 7975 (89) | 0.31 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 520 (3) | 215 (2) | 0.30 |

| Hispanic | 620 (3) | 395 (4) | 0.22 |

| Other | 675 (4) | 400 (4) | 0.27 |

| Missing | 1210 | 830 | ··· |

| CCI, median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.8–3.2) | 0.8 (0–1.9) | <0.0001a |

| Primary insurance, n (%) | |||

| Medicaid/Medicare | 18 110 (95) | 9230 (94) | 0.43 |

| Private | 755 (4) | 430 (4) | 0.48 |

| Other/self‐pay | 250 (1) | 140 (1) | 0.71 |

| Median household income, n (%)b | |||

| Low | 3885 (21) | 1695 (18) | 0.007a |

| Medium | 4765 (25) | 2160 (24) | 0.02a |

| High | 4820 (26) | 2665 (27) | 0.10 |

| Highest | 5365 (28) | 3100 (32) | 0.007a |

| Hospital region, n (%) | |||

| Northeast | 4620 (24) | 2830 (29) | 0.003a |

| Midwest | 4555 (24) | 2570 (26) | 0.14 |

| South | 6290 (33) | 2490 (25) | <0.0001a |

| West | 3680 (19) | 120 (1) | 0.82 |

| Hospital type, n (%) | |||

| Rural, non‐teaching | 160 (1) | 120 (1) | 0.12 |

| Urban, non‐teaching | 1930 (10) | 1270 (13) | 0.009a |

| Urban, teaching | 17 055 (89) | 8425 (86) | 0.004a |

| Hospital size, n (%)c | |||

| Small | 1025 (5) | 475 (5) | 0.57 |

| Medium | 3520 (18) | 1665 (17) | 0.27 |

| Large | 14 600 (76) | 7675 (78) | 0.20 |

CCI indicates Charlson Comorbidity Index; IQR, interquartile range; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Statistical significance.

Median household income for each patient's ZIP code was characterized into quartiles, each year.

Hospital size was based on the number of short‐term acute care hospital beds; cut points were chosen for each region and location combination so that approximately one third of hospitals would appear in each category.

Figure 2.

Average CCI score among hospitalizations of octogenarians undergoing aortic valve replacement at TAVR‐performing hospitals, stratified by procedure type. CCI indicates Charlson comorbidity index; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement. P‐values for trend: TAVR P=0.03, SAVR P=0.06.

In octogenarians, TAVR was associated with lower incidence of AKI (13% versus 17%, P=0.0006), bleeding (33% versus 51%, P<0.0001), blood transfusions (18% versus 38%, P<0.0001), and cardiogenic shock (2% versus 3%, P=0.007) but higher incidence of PPM (11% versus 6%, P<0.0001) and vascular complications (5% versus 4%, P=0.02) compared with SAVR (Table 2). Incidence of TIA/stroke (3% for TAVR versus 3% for SAVR, P=0.71) and in‐hospital mortality (3% versus 2%, P=0.26) did not significantly differ between groups. TAVR was associated with shorter median LOS (3.8 days versus 6.2 days, P<0.0001) and a higher proportion of home discharges (69% versus 52%, P<0.0001) compared with SAVR. When stratifying by comorbidity burden, the reduction in LOS after TAVR, compared with after SAVR, was significantly greater for octogenarians with higher CCI score (CCI <2: change in estimate −2.61 days, 95% CI −2.99, −2.22; CCI ≥2: −3.56, 95% CI −4.09, −3.04, P=0.004) (Table 3). All other effects were consistent across CCI.

Table 2.

Crude Incidence of In‐Hospital Complications, LOS, and Discharge Disposition in Hospitalizations of Octogenarians Undergoing Aortic Valve Replacement, Stratified by Procedure Type

| TAVR 19 145 (66%) | SAVR 9815 (34%) | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In‐hospital complications, n (%) | ||||

| Permanent pacemaker implantation | 2060 (11) | 615 (6) | 1.80 (1.46, 2.23) | <0.0001a |

| Transient ischemic attack/stroke | 560 (3) | 305 (3) | 0.94 (0.67, 1.31) | 0.71 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 330 (2) | 270 (3) | 0.62 (0.44, 0.88) | 0.007a |

| Cardiac arrest | 505 (3) | 200 (2) | 1.30 (0.91, 1.86) | 0.14 |

| Acute kidney injury | 2580 (13) | 1655 (17) | 0.77 (0.66, 0.89) | 0.0006a |

| Any bleeding | 6410 (33) | 5045 (51) | 0.48 (0.42, 0.54) | <0.0001a |

| Blood transfusion | 3410 (18) | 3765 (38) | 0.35 (0.30, 0.40) | <0.0001a |

| Vascular complications | 995 (5) | 375 (4) | 1.38 (1.05, 1.82) | 0.02a |

| Discharge disposition, n (%) | ||||

| Routine | 13 220 (69) | 5115 (52) | 2.05 (1.81, 2.32) | <0.0001a |

| Transfer, short term hospital | 115 (1) | 105 (1) | 0.56 (034, 0.93) | <0.0001a |

| Transfer, skilled nursing facility | 5310 (28) | 4385 (45) | 0.48 (0.42, 0.54) | <0.0001a |

| Death | 500 (3) | 210 (2) | 1.23 (0.86, 1.76) | 0.26 |

| TAVR 19 145 (66%) | SAVR 9815 (34%) | CIE (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOS after AVR, days, median (IQR) | 3.8 (2.3–5.9) | 6.2 (4.8–8.3) | −2.83 (−3.14, −2.52) | <0.0001a |

AVR indicates aortic valve replacement; CIE, change in estimate; IQR, interquartile range; LOS, length of stay; OR, odds ratio; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Statistical significance.

Table 3.

Crude Effect of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement, Compared With Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement, on Hospital Complications, LOS, and Discharge Disposition in Hospitalizations of Octogenarians Undergoing Aortic Valve Replacement, Stratified by Charlson Comorbidity Index

| CCI <2 OR (95% CI) | CCI ≥2 OR (95% CI) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In‐hospital complications | |||

| Permanent pacemaker implantation | 1.72 (1.25, 2.38) | 1.66 (1.23, 2.25) | 0.88 |

| Transient ischemic attack/stroke | 0.89 (0.52, 1.52) | 0.88 (0.57, 1.36) | 0.97 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 0.57 (0.29, 1.11) | 0.54 (0.35, 0.83) | 0.88 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1.03 (0.60, 1.75) | 1.68 (0.96, 2.96) | 0.22 |

| Acute kidney injury | 0.58 (0.43, 0.80) | 0.58 (0.48, 0.69) | 0.96 |

| Any bleeding | 0.49 (0.40, 0.59) | 0.42 (0.35, 0.50) | 0.25 |

| Blood transfusion | 0.28 (0.23, 0.35) | 0.37 (0.31, 0.44) | 0.06 |

| Vascular complications | 1.24 (0.82, 1.88) | 1.39 (0.95, 2.03) | 0.68 |

| Discharge disposition | |||

| Routine | 2.41 (2.01, 2.91) | 2.16 (1.83, 2.54) | 0.35 |

| Transfer, short‐term hospital | 0.35 (0.13, 0.96) | 0.81 (0.34, 1.92) | 0.26 |

| Transfer, skilled nursing facility | 0.41 (0.34, 0.49) | 0.45 (0.38, 0.53) | 0.43 |

| Death | 1.14 (0.62, 2.10) | 1.10 (0.69, 1.78) | 0.94 |

| CIE (95% CI) | CIE (95% CI) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOS after AVR, days | −2.61 (−2.99, −2.22) | −3.56 (−4.09, −3.04) | 0.004 |

AVR indicates aortic valve replacement; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CIE, change in estimate; LOS, length of stay; OR, odds ratio.

Testing the statistical significance of Charlson Comorbidity Index (<2 vs ≥2) as an interaction term for the association between TAVR and in‐hospital complication, discharge disposition, and LOS after AVR.

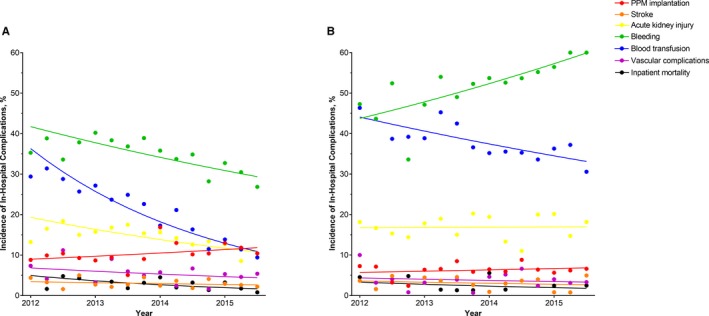

Among TAVR hospitalizations, between 2012 and 2015, there were significant reductions in incidence of AKI (16% in 2012 versus 10% in 2015, P<0.0001), bleeding (37% versus 30%, P<0.0001), blood transfusions (29% versus 11%, P<0.0001), and vascular complications (7% versus 5%, P<0.0001), but a significant rise in the incidence of PPM (10% versus 12%, P=0.0005) (Figure 3A). Among SAVR hospitalizations during the same time period, there was a significant decrease in the incidence of blood transfusions (42% in 2012 versus 35% in 2015, P<0.0001), but a significant increase in the incidence of bleeding (44% versus 59%, P<0.0001) (Figure 3B). From 2012 to 2015, there were also significant decreases in the incidence of in‐hospital mortality after TAVR (4% versus 2%, P<0.0001) and SAVR (3% versus 2%, P=0.007).

Figure 3.

Incidence of in‐hospital mortality and complications in hospitalizations of octogenarians undergoing (A) transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and (B) surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), between 2012 and 2015. Crude results; (A) P‐values for trend: permanent pacemaker implantation P=0.0005, stroke P=0.13, acute kidney injury P<0.0001, bleeding P<0.0001, blood transfusion P<0.0001, vascular complications P<0.0001, mortality P<0.0001; (B) P‐values for trend: permanent pacemaker implantation P=0.18, stroke P=0.08, acute kidney injury P=0.86, bleeding P<0.0001 blood transfusion P<0.0001, vascular complications P=0.12, mortality P=0.007. PPM indicates permanent pacemaker.

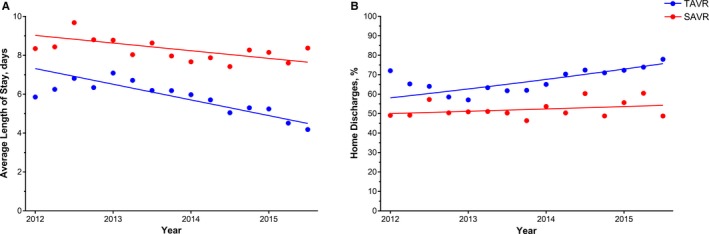

From 2012 to 2015, average LOS decreased both for TAVR (5.7 days in 2012 versus 4.6 days in 2015, P<0.0001) and for SAVR (8.3 versus 8.0, P=0.003) (Figure 4). Additionally, the proportion of home discharges after TAVR significantly increased (64% versus 75%, P<0.0001), but the proportion after SAVR remained consistent (52% versus 55%, P=0.08).

Figure 4.

Trends in (A) average length of stay and (B) routine discharges after valve replacement among hospitalizations of octogenarians undergoing aortic valve replacement at TAVR‐performing hospitals between 2012 and 2015, stratified by procedure type. Crude results; (A) P‐values for trend: TAVR P<0.0001, SAVR P=0.003; (B) P‐values for trend: TAVR P<0.0001, SAVR P=0.08. SAVR indicates surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

After excluding patients with missing data and trimming non‐overlapping ends of the propensity score distributions, the propensity score analysis sample included 15 095 weighted TAVR hospitalizations and 7640 weighted SAVR hospitalizations, which represented 79% and 78%, respectively, of the 2 groups in the original sample (Tables S2 and S3). After standardizing to TAVR patients, TAVR was less likely to be associated with AKI (odds ratio [OR] 0.55, 95% CI 0.45, 0.68), bleeding (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.37, 0.53), blood transfusions (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.30, 0.44), or cardiogenic shock (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.33, 0.92), compared with if SAVR was performed (Table 4). No significant differences were observed in the odds of PPM (OR 1.34, 95% CI 0.96, 1.85), TIA/stroke (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.60, 1.99), cardiac arrest (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.46, 1.59), vascular complications (OR 1.29, 95% CI 0.82, 2.03), or in‐hospital mortality (OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.32, 1.11) between the 2 groups. TAVR was also associated with lower odds of transfer to skilled nursing facility (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.29, 0.41) and shorter LOS (change in estimate −3.29 days, 95% CI −3.82, −2.75).

Table 4.

Standardized Effect of Undergoing TAVR, Compared With Undergoing SAVR, on In‐Hospital Complications, Discharge Disposition, and LOS After Valve Replacement

| TAVR Patientsa | SAVR Patientsb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall OR (95% CI)c | Transapical Only OR (95% CI)c | Endovascular Only OR (95% CI)c | Overall OR (95% CI)c | |

| In‐hospital complications | ||||

| Permanent pacemaker implantation | 1.34 (0.96, 1.85) | 0.88 (0.56, 1.39) | 1.43 (1.02, 1.99) | 1.70 (1.30, 2.21) |

| Transient ischemic attack/stroke | 1.10 (0.60, 1.99) | 1.18 (0.54, 2.55) | 1.08 (0.59, 1.98) | 1.12 (0.72, 1.73) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 0.55 (0.33, 0.92) | 0.98 (0.49, 2.00) | 0.47 (0.28, 0.80) | 0.51 (0.30, 0.84) |

| Cardiac arrest | 0.86 (0.46, 1.59) | 0.90 (0.38, 2.11) | 0.85 (0.45, 1.59) | 0.90 (0.55, 1.46) |

| Acute kidney injury | 0.55 (0.45, 0.68) | 1.05 (0.78, 1.41) | 0.47 (0.38, 0.59) | 0.56 (0.46, 0.69) |

| Any bleeding | 0.44 (0.37, 0.53) | 0.67 (0.53, 0.86) | 0.41 (0.34, 0.48) | 0.46 (0.40, 0.54) |

| Blood transfusion | 0.36 (0.30, 0.44) | 0.75 (0.58, 0.97) | 0.30 (0.25, 0.37) | 0.40 (0.34, 0.48) |

| Vascular complications | 1.29 (0.82, 2.03) | 0.67 (0.33, 1.36) | 1.41 (0.90, 2.23) | 1.13 (0.78, 1.62) |

| Discharge dispositiond | ||||

| Transfer, short term hospital | 0.45 (0.15, 1.32) | NA | 0.46 (0.16, 1.34) | 0.62 (027, 1.45) |

| Transfer, skilled nursing facility | 0.34 (0.29, 0.41) | 0.86 (0.67, 1.09) | 0.28 (0.23, 0.34) | 0.43 (0.36, 0.50) |

| Death | 0.60 (0.32, 1.11) | 1.24 (0.57, 2.69) | 0.52 (0.28, 0.98) | 0.68 (0.42, 1.11) |

| CIE (95% CI)c | CIE (95% CI)c | CIE (95% CI)c | CIE (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOS after AVR, days | −3.29 (−3.82, −2.75) | −0.59 (−1.32, 0.14) | −3.79 (−4.32, −3.25) | −2.82 (−3.25, −2.38) |

AVR indicates aortic valve replacement; CIE, change in estimate; LOS, length of stay; NA, not analyzable; OR, odds ratio; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Effect of undergoing TAVR, compared with undergoing SAVR, among patients who underwent TAVR.

Effect of undergoing TAVR, compared with undergoing SAVR, among patients who underwent SAVR.

Standardized morbidity ratio (SMR) weights were calculated using admit year, sex, age, race/ethnicity, individual components of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), primary insurance type, income, hospital region, hospital type, and hospital size; age was modeled as a restricted cubic spline; weights were trimmed using 1% and 99% cut points; Confidence intervals were estimated using the standard deviation calculated from 500 non‐parametric bootstrapping samples.

Compared with routine/home healthcare discharge.

After stratifying TAVR by approach (endovascular versus transapical), only endovascular TAVR was associated with shorter LOS (change in estimate −3.79 days, 95% CI −4.32, −3.25) and lower odds of AKI (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.38, 0.59) or cardiogenic shock (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.28, 0.80), but higher odds of PPM (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.02, 1.99), compared with if SAVR was performed (Table 4). Both endovascular and transapical TAVR had lower odds of bleeding (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.34, 0.48 and OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.53, 0.86, respectively) and blood transfusion (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.25, 0.37 and OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.58, 0.97, respectively).

Additionally, when the cohort was standardized to SAVR patients (ie, the effect of TAVR among patients who underwent SAVR), similar results were seen (Table 4).

Discussion

This analysis of nationally representative data shows that TAVR use among octogenarians in the United States has been increasing since 2012 and accounted for 3 out of 4 aortic valve replacements in 2015. Despite a higher comorbidity burden, hospitalizations for TAVR, compared with those for SAVR, were associated with significantly higher proportions of home discharges, shorter LOS, and lower incidence of AKI, bleeding, blood transfusions, and cardiogenic shock, but higher incidence of PPM and vascular complications. The incidence of TIA/stroke and in‐hospital mortality did not differ between groups. After accounting for differences in patient and hospital characteristics, TAVR continued to be associated with significantly shorter average LOS and lower odds of AKI, bleeding, blood transfusions, cardiogenic shock, and transfer to skilled nursing facility, compared with if SAVR was performed. No differences in odds of PPM, vascular complications, or TIA/stroke were observed between groups in the standardized analysis.

These results are valuable for clinicians deciding between TAVR and SAVR in octogenarians, since both procedures are currently recognized as viable options.7, 8 This propensity score weighted analysis reflects a comparison between the effect of TAVR and the effect of SAVR among high‐risk patients and suggests that high‐risk octogenarians should receive TAVR for the above benefits. Even without adjusting for baseline characteristics, most in‐hospital outcomes were superior after TAVR than after SAVR. These associations remained consistent across low and high CCI score groups, except for LOS (significant reductions were still observed after TAVR in both groups), suggesting that these advantages of TAVR may apply to all octogenarians, irrespective of comorbidity burden.

The higher likelihood of home discharge, lower likelihood of transfer to skilled nursing facility, and shorter LOS, observed in our results for TAVR compared with SAVR, are especially important among octogenarians. Among geriatric patients, longer hospital stays have been associated with functional decline at discharge and at 1 month.16 Additionally among TAVR patients, discharge to a skilled nursing facility was an independent predictor of 30‐day readmission.17 Medicare beneficiaries who were hospitalized for heart failure and discharged to skilled nursing facilities also had higher rates of rehospitalization, as well as higher rates of all‐cause mortality, after adjusting for patient characteristics.18

Randomized controlled trials have shown that TAVR is associated with lower risk of AKI, bleeding, and blood transfusions, and higher risk of PPM and vascular complications, compared with SAVR.5, 6, 19, 20 Our study affirms these conclusions in octogenarians using nationally representative data based on outcomes of procedures performed in more diverse hospital settings in patients with more heterogeneous clinical characteristics, likely making these results generalizable to the entire octogenarian population. Additionally, our results demonstrating a decline in the incidence of in‐hospital mortality over time among octogenarians receiving TAVR are concordant with results of studies based on nationally representative data from France and Germany.21, 22

We observed significant declines over time in the incidence of AKI, bleeding, and blood transfusions after TAVR, which can likely be attributed to increased operator experience, better imaging and valve sizing, smaller delivery systems, and enhanced valve technology.23 Additionally, we detected a significant increase over time in the incidence of PPM after TAVR but there is conflicting evidence as to whether PPM after TAVR is associated with increased long‐term mortality.24, 25, 26, 27, 28 After stratifying by TAVR access, the improvements in LOS and discharge disposition, compared with if the patients had received SAVR, were observed only in the endovascular TAVR cohort. The outcomes of endovascular TAVR, compared with that of SAVR, have been further explored in a recent meta‐analysis of 30‐day outcomes, which found transfemoral TAVR to be associated with lower risk of atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction.29

While our secondary analysis of the effect of TAVR in patients who received SAVR, which represented an all‐risk population, showed that TAVR compared with SAVR was associated with shorter LOS and lower odds of transfer to skilled nursing facility and most complications (except for PPM), results from ongoing randomized controlled trials comparing TAVR and SAVR outcomes in low surgical‐risk patients are needed to definitively determine if an all‐surgical‐risk indication for TAVR in octogenarians is appropriate. Studies comparing longer‐term complication rates after TAVR versus SAVR specifically among octogenarians are also needed. Although bicuspid aortic valve disease is often considered to affect younger patients, a single‐center study found a 22% prevalence among octogenarians undergoing aortic valve replacement.30 Since patients with bicuspid aortic valves are often excluded from randomized controlled trials, further research in this specific patient population is also needed.

This study has several limitations. We were unable to calculate the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS‐PROM) or European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II (EuroSCORE II) risk scores using NIS data but were able to subset our analyses to high‐risk patients by using SMR weighting. Using CCI as a proxy to assess risk level, we found that average CCI scores did not meaningfully change over the study period. Future TAVR research based on large databases should also use these statistical methods to remove patients ineligible for TAVR and appropriately account for risk level. NIS also tracks data at the hospitalization level rather than at the patient level. Since we were unable to determine if the sample included repeat observations of patients who underwent >1 aortic valve replacement (TAVR or SAVR) during the study period, we interpreted results at the hospitalization level. There was also potential for coding errors, missing codes, and differences in coding practices across the hospitals included in NIS but these coding issues would likely be random and not differ between TAVR and SAVR groups. Excluding cases with concurrent coronary artery bypass surgery may have affected our selection of SAVR cases. Finally, ICD‐9‐CM coding prevented us from being able to differentiate between different endovascular approaches (eg transfemoral, transaxillary) and therefore, limited our stratified analysis.

In conclusion, our study suggests that among high‐risk octogenarians being considered for aortic valve replacement, TAVR may be preferable to SAVR, especially if an endovascular approach is an option, because of benefits including shorter LOS and lower likelihood of developing AKI, bleeding, or cardiogenic shock, or requiring a blood transfusion or transfer to a skilled nursing facility. Moreover, despite TAVR being performed in high‐risk patients, most in‐hospital outcomes favored TAVR when compared with SAVR performed in patients across the risk spectrum, even before accounting for risk and regardless of comorbidity burden. This suggests that TAVR may be preferred for all octogenarians, who are frail and have low physiologic reserve. However, additional research comparing outcomes after TAVR and SAVR among lower‐risk octogenarians is needed to support this claim.

Disclosures

Ms Ramm serves on an advisory board for Boston Scientific. Dr Cavender receives research support from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Takeda, The Medicines Company and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Chiesi, Janssen, Merck, Novo‐Nordisk, Sanofi‐Aventis. Ms Strassle has received salary support from researchEZ LLC and Dr Arora's spouse has proprietary role in researchEZ LLC. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Table S1. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) Diagnostic and Procedural Codes Used to Identify Complications

Table S2. Demographics and Characteristics of Patients Excluded From the Standardized Morbidity Ratio (SMR) Weighted Analyses

Table S3. Demographics and Characteristics of Patients Included in the Standardized Morbidity Ratio (SMR) Weighted Analyses

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011206 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011206.)

References

- 1. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez‐Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population‐based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eveborn GW, Schirmer H, Heggelund G, Lunde P, Rasmussen K. The evolving epidemiology of valvular aortic stenosis. The Tromsø Study. Heart. 2013;99:396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050; 2010.

- 4. Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, Pai RG. Survival in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis is dramatically improved by aortic valve replacement: results from a cohort of 277 patients aged ≥80 years. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:722–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, Makkar RR, Svensson LG, Kodali SK, Thourani VH, Tuzcu EM, Miller DC, Herrmann HC, Doshi D, Cohen DJ. Transcatheter or surgical aortic‐valve replacement in intermediate‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1609–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, Kleiman NS, Søndergaard L, Mumtaz M, Adams DH, Deeb GM, Maini B, Gada H, Chetcuti S, Gleason T, Heiser J, Lange R, Merhi W, Oh JK, Olsen PS, Piazza N, Williams M, Windecker S, Yakubov SJ, Grube E, Makkar R, Lee JS, Conte J, Vang E, Nguyen H, Chang Y, Mugglin AS, Serruys PWJC, Kappetein AP. Surgical or transcatheter aortic‐valve replacement in intermediate‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, De Bonis M, Hamm C, Holm PJ, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Lansac E, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Rosenhek R, Sjögren J, Tornos Mas P, Vahanian A, Walther T, Wendler O, Windecker S, Zamorano JL; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2017 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2739–2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Fleisher LA, Jneid H, Mack MJ, McLeod CJ, O'Gara PT, Rigolin VH, Sundt TM, Thompson A. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e1159–e1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Forman DE, Berman AD, McCabe CH, Baim DS, Wei JY. PTCA in the elderly: the “young‐old” versus the “old‐old”. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hirji SA, Ramirez‐Del Val F, Kolkailah AA, Ejiofor JI, McGurk S, Chowdhury R, Lee J, Shah PB, Sobieszczyk PS, Aranki SF, Pelletier MP, Shekar PS, Kaneko T. Outcomes of surgical and transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the octogenarians—surgery still the gold standard? Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;6:453–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mantha A, Juo Y‐Y, Morchi R, Ebrahimi R, Ziaeian B, Shemin RJ, Benharash P. Evolution of surgical aortic valve replacement in the era of transcatheter valve technology. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:1080–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project . NIS Overview. 2018.

- 13. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD‐9‐CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stürmer T, Wyss R, Glynn RJ, Brookhart MA. Propensity scores for confounder adjustment when assessing the effects of medical interventions using nonexperimental study designs. J Intern Med. 2014;275:570–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khera R, Angraal S, Couch T, Welsh JW, Nallamothu BK, Girotra S, Chan PS, Krumholz HM. Adherence to methodological standards in research using the National Inpatient Sample. JAMA. 2017;318:2011–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur‐Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital‐associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kolte D, Khera S, Sardar MR, Gheewala N, Gupta T, Chatterjee S, Goldsweig A, Aronow WS, Fonarow GC, Bhatt DL, Greenbaum AB, Gordon PC, Sharaf B, Abbott JD. Thirty‐day readmissions after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the United States: insights from the nationwide readmissions database. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:e004472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Allen LA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Curtis LH, Dai D, Masoudi FA, Bhatt DL, Heidenreich PA, Fonarow GC. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility and subsequent clinical outcomes among older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Williams M, Dewey T, Kapadia S, Babaliaros V. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic‐valve replacement in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2187–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ, Yakubov SJ, Coselli JS, Deeb GM, Gleason TG , Buchbinder M, Hermiller J, Kleiman NS, Chetcuti S, Heiser J, Merhi W, Zorn G, Tadros P, Robinson N, Petrossian G, Hughes GC, Harrison JK, Conte J, Maini B, Mumtaz M, Chenoweth S, Oh JK. Transcatheter aortic‐valve replacement with a self‐expanding prosthesis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1790–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nguyen V, Michel M, Eltchaninoff H, Gilard M, Dindorf C, Iung B, Mossialos E, Cribier A, Vahanian A, Chevreul K, Messika‐Zeitoun D. Implementation of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in France. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1614–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reinöhl J, Kaier K, Reinecke H, Schmoor C, Frankenstein L, Vach W, Cribier A, Beyersdorf F, Bode C, Zehender M. Effect of availability of transcatheter aortic‐valve replacement on clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2438–2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nishimura RA, O'Gara PT, Bonow RO. Guidelines update on indications for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1036–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buellesfeld L, Stortecky S, Heg D, Hausen S, Mueller R, Wenaweser P, Pilgrim T, Gloekler S, Khattab AA, Huber C, Carrel T, Eberle B, Meier B, Boekstegers P, Jüni P, Gerckens U, Grube E, Windecker S. Impact of permanent pacemaker implantation on clinical outcome among patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nazif TM, Dizon JM, Hahn RT, Xu K, Babaliaros V, Douglas PS, El‐Chami MF, Herrmann HC, Mack M, Makkar RR, Miller DC, Pichard A, Tuzcu EM, Szeto WY, Webb JG, Moses JW, Smith CR, Williams MR, Leon MB, Kodali SK. Predictors and clinical outcomes of permanent pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the PARTNER (Placement of AoRtic TraNscathetER Valves) trial and registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fadahunsi OO, Olowoyeye A, Ukaigwe A, Li Z, Vora AN, Vemulapalli S, Elgin E, Donato A. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of permanent pacemaker implantation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement: analysis from the U.S. Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology TVT Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:2189–2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cahill TJ, Chen M, Hayashida K, Latib A, Modine T, Piazza N, Redwood S, Sondergaard L, Prendergast BD. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: current status and future perspectives. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2625–2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Siontis GCM, Praz F, Pilgrim T, Mavridis D, Verma S, Salanti G, Søndergaard L, Jüni P, Windecker S. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation vs. surgical aortic valve replacement for treatment of severe aortic stenosis: a meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3503–3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arora S, Vaidya SR, Strassle PD, Misenheimer JA, Rhodes JA, Ramm CJ, Wheeler EN, Caranasos TG, Cavender MA, Vavalle JP. Meta‐analysis of transfemoral TAVR versus surgical aortic valve replacement. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91:806–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roberts WC, Janning KG, Ko JM, Filardo G, Matter GJ. Frequency of congenitally bicuspid aortic valves in patients ≥80 years of age undergoing aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis (with or without aortic regurgitation) and implications for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1632–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) Diagnostic and Procedural Codes Used to Identify Complications

Table S2. Demographics and Characteristics of Patients Excluded From the Standardized Morbidity Ratio (SMR) Weighted Analyses

Table S3. Demographics and Characteristics of Patients Included in the Standardized Morbidity Ratio (SMR) Weighted Analyses