Abstract

Tailored ruthenium(IV) complexes can catalyze the isomerization of allylic alcohols into saturated carbonyl derivatives under physiologically relevant conditions, and even inside living mammalian cells. The reaction, which involves ruthenium-hydride intermediates, is bioorthogonal and biocompatible, and can be used for the “in cellulo” generation of fluorescent and bioactive probes. Overall, our research reveals a novel metal-based tool for cellular intervention, and comes to further demonstrate the compatibility of organometallic mechanisms with the complex environment of cells.

Enzymes catalyze a myriad of chemical transformations that are essential to life, including hydrolysis, ligations, isomerizations or redox processes.1 Chemists are not constrained to generate life-sustaining reactions, and along the years have invented many catalytic processes that do not occur in nature. Especially appealing are those transformations involving metal catalysis.2 While these reactions are less efficient than those promoted by enzymes, they present a broader scope, and are more versatile and mechanistically diverse. Therefore, exporting the power of “non-natural” metal catalysis to the biological arena might open unforeseen opportunities for metabolic or genetic intervention, and unveil new tools in therapy and diagnosis.

Unfortunately, most transition metal-catalyzed processes occur under conditions that are not compatible with aqueous and biological settings, and therefore, performing these reactions under physiological environments is certainly challenging. Nonetheless, along recent years several groups have demonstrated the viability of promoting bioorthogonal metal-mediated reactions in biological buffers, and even in living settings.3 While the area is yet in its infancy, there have been reports on biocompatible metal-promoted deprotections (Pd, Ru),4 click-like annulations (Cu or Ru),5 cross-couplings (Pd),6,4b,4i and even gold-promoted carbocyclizations.7

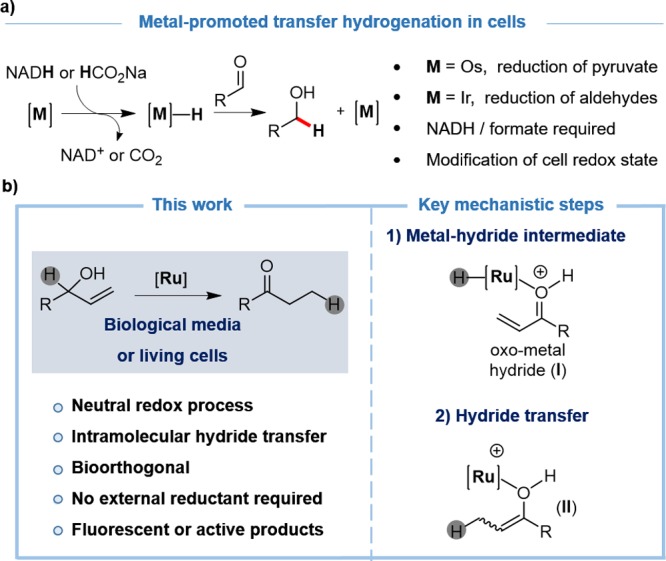

Sadler and Do have independently reported the use of osmium or iridium complexes to alter NADH/NAD+ cellular equilibriums, or promote reductions of specific aldehydes or ketones (Figure 1a).8 Albeit the efficiency of these processes was low, these studies suggest that metal-hydride species can be generated inside cells. In light of these observations, and considering previous contributions by Gimeno and co-workers on a ruthenium-mediated isomerization of allylic alcohols to ketones in water,9 we questioned whether this type of redox-neutral processes, which likely involve ruthenium hydride species, could be achieved in biorelevant media or even in intracellular settings. Do the ruthenium intermediates survive to the stringent conditions of a complex biological buffer or a living cell? Are the hydride intermediates compatible with biological components? Can this “non-natural” metal catalysis promote biological responses?

Figure 1.

(a) Transfer hydrogenations have been developed to either alter the redox status of cells or to reduce abiotic substrates; (b) this work, and ruthenium-hydride intermediates that are likely involved in the reaction.

Herein we provide some answers to these questions, by reporting the first metal-catalyzed isomerization reaction that can be carried out under biological conditions, and more importantly, in the interior of living mammalian cells (Figure 1b). The reaction is promoted by a ruthenium(IV) catalyst that combines water solubility with some lipophilicity. The redox-neutral isomerization allows to transform nonfunctional, abiotic allyl alcohols into fluorescent or bioactive ketones, in the interior of living mammalian cells.

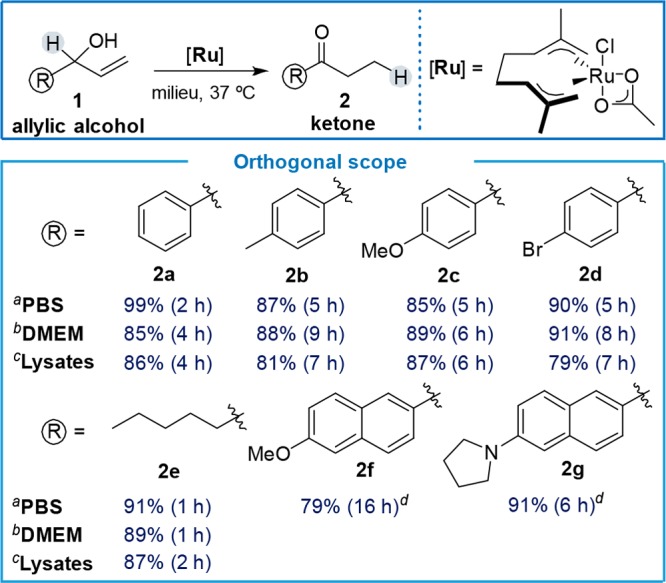

The viability of the isomerization was first explored using 1-phenylprop-2-en-1-ol (1a) as substrate, and the bis-allyl Ru(IV) complex [Ru] as catalyst (Table 1 and S1).10 The reaction is very efficient in water and PBS at physiological temperatures (37 °C), even using only 1 mol % of the metal complex (92%, 1.5 h). More importantly, the transformation can be efficiently accomplished in complex cell culture media, such as DMEM (Dubelcco’s modified Eagle’s medium), and even in cell lysates (using 5 mol % of catalyst).

Table 1. Scope of the Ruthenium Catalyzed Isomerization of Allylic Alcoholsa.

Performed using 1 (0.2 mmol), milieu (1.0 mL) and [Ru] (2 mol %).

[Ru] (5 mol %).

[Ru] (5 mol %), cells lysates 7 mg/mL.

Milieu with 20% THF.

The efficiency and orthogonality of the reaction can be replicated with other substrates containing modified aryl or naphthyl substituents to give the expected ketones (Table 1, 2a–d and 2f–g, respectively), as well as with aliphatic derivatives (Table 1, product 2e). Other ruthenium catalysts like [RuCp*Cl(COD)], [RuCp(MeCN)3][PF6] or [RuCl2(p-cymene)]2 do work in water, but perform very poorly in cell lysates. We also tested the iridium complex employed by Do and co-workers for the reduction of carbonyl compounds, as well as [IrCl2Cp*]2,11 but isomerization yields were very low (Table S1). Therefore, complex [Ru] seems to present the best balance between reactivity and stability, when used in biologically relevant media.

While the mechanism of the reaction has not been fully elucidated,12,9a,9b it likely involves an initial aquation of the precatalyst, followed by coordination of the allylic alcohol to the ruthenium center and β-hydrogen elimination to generate hydride intermediate of type I (Figure 1b). An intramolecular hydride transfer produces an oxo complex (type II) that releases the product and regenerates the Ru(IV) catalyst.

The presence of ruthenium hydride intermediates was confirmed by deuteration experiments (Section S5), which demonstrated that they survive under stringent conditions of a milieu like DMEM. The high catalytic activity and orthogonality of the ruthenium complex [Ru] under biologically relevant conditions, prompted us to evaluate the viability of performing the reaction in native cellular settings. This required a way of monitoring the process, and therefore we designed the substrate 1g, which displays very low fluorescence above 500 nm when excited at 385 nm. However, the isomeric ketone product 2g is highly emissive at the same wavelength of excitation (Figures S1–S3).

The intracellular reactions were explored in human (A549 and HeLa), and animal (Vero) cell lines. Confocal microscopy of live cells treated as indicated in the caption of Figure 2c, revealed that there is a considerable intracellular buildup of green fluorescence after 1 h, mainly located in the cytosol, even using only 10 μM of [Ru] and 100 μM of substrate (Figure 2b, panel B). Considering the mean value of corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) there is an increase of up to 38-fold in the emission of cells treated with 1g, when they had been previously preincubated with the ruthenium complex (Figure 2c). Control experiments of untreated cells confirmed that such increase is a consequence of the intracellular formation of the product. Similar results were obtained with A549 and Vero cells (Figures S6 and S7).

Figure 2.

Reactivity of ruthenium complex in living cells. (a) Ruthenium catalyzed isomerization of allylic alcohol 1g; (b) Fluorescence micrographies of HeLa cells (confocal): (A) cells incubated with substrate 1g (brightfield and green channel); (B) cells incubated with [Ru], washed and treated with substrate 1g (brightfield and green channel); (C) cells incubated with product 2g (brightfield and green channel); (c) CTFC measurements in HeLa, Vero and A549 cells. Reaction conditions: cells were incubated with [Ru] (10 μM) for 30 min, followed by two washings with DMEM and treatment with substrate 1g (100 μM) for 1 h. Error bars represent the standard error of three independent experiments. λex = 385 nm, λem = 520–700 nm. Scale bar: 12.5 μm.

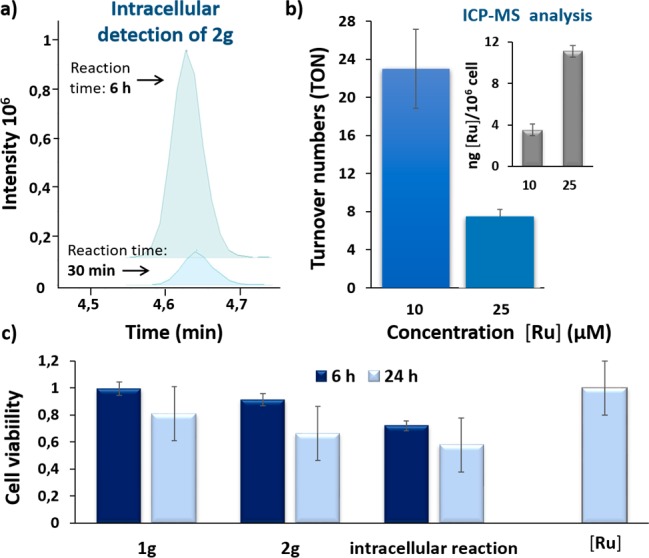

The formation of the expected product 2g was further confirmed by LC-MS analysis of methanolic extracts of the cells after running the reaction for 6 h, and 2-fold washing with DMEM and PBS. The amount of product in the washings was low; however, the methanolic extracts contained a significant amount of ketone 2g.13 Importantly, using LC-MS techniques, and appropriate calibration curves, we could also quantify the product generated inside cells (Figure 3a and Figure S11). The formation of the product 2g increases with time, which demonstrates the persistence of a reactive metal complex inside the cells. ICP-MS analysis of cellular extracts obtained after exposing HeLa cells to 10 or 25 μM of [Ru], and thoroughly washed with DMEM, revealed a ruthenium content of 3.5 or 11.1 ng/106 cells, respectively (Figure 3b), while untreated cells contain over 0.2 ng/106 cells (Figure S10). Combining this information with the amount of intracellular product, it is possible to calculate turnover numbers (TON) with a relatively good accuracy (Figure 3b). Indeed, we found a turnover of over 22 in experiments with cells treated with 10 μM of [Ru] and 100 μM of substrate, after 6 h (Section S12). To our knowledge this represents the first quantitative demonstration of turnover in an organometallic intracellular reaction.

Figure 3.

(a) Extracted ion chromatogram of the product 2g generated intracellularly (methanolic extract). HeLa cells pretreated with 10 μM of [Ru] for 50 min were washed twice and incubated with 100 μM of substrate 1g for 30 min/6 h; (b) turnover numbers of intracellular catalysis at 10 and 25 μM of catalyst loading (the quantification was performed considering the total crude material after methanolic extract and two washing steps (DMEM and PBS)); (inset) ICP-MS values of the intracellular accumulation of ruthenium after incubation of cells in DMEM with 10 or 25 μM (in DMSO) for 50 min, double washing with PBS and digestion with HNO3; (c) cytotoxicity studies in HeLa cells. Reaction conditions: cells were incubated with either substrate 1g (100 μM) or product 2g (100 μM) for 6/24 h. Alternatively, cells were mixed with [Ru] (50 μM) for 30 min, washed twice with DMEM and treated with substrate 1g (100 μM) for 6/24 h (labeled as intracellular reaction). Right bar: cells were incubated with [Ru] (50 μM) for 30 min, followed by two washings with DMEM and the toxicity checked after 24 h. Error bars represent the standard error of three independent experiments.

While the above data demonstrate the viability of achieving ruthenium-mediated isomerizations in native intracellular settings, an important challenge in this nascent scientific field of cellular metallocatalysis consists of the intracellular generation of active products.14 Up to now, these studies have been essentially restricted to uncaging reactions from appropriately protected precursors. We therefore wondered whether the isomerization reaction could also be associated with changes in some biological activity. Using standard MTT techniques, we confirmed that using concentrations up to 100 μM, neither the ruthenium complex nor the substrate 1g or product 2g presented noticeable toxicities after 6 h (Figure 3c). However, after 24 h, we observed toxicity in the case of the product (32% of cell death, Figure S4). In order to study the effect of the “in cellulo” generation of the product 2g, we added 100 μM of the substrate 1g to cells that had been treated with 50 μM of [Ru], and thoroughly washed with DMEM. In this case, we observed a higher decrease in viability (Figure 3c, 45% of death after 24 h). This response is also noticeable even after only 6 h, when more than 30% of the cells died, 30 times more than that observed with the substrate (Figure 3c). Given than the complex [Ru] is not toxic at such concentration (Figure S5), these results suggest that the intracellular generation of the product produces a more effective biological response than its external addition.

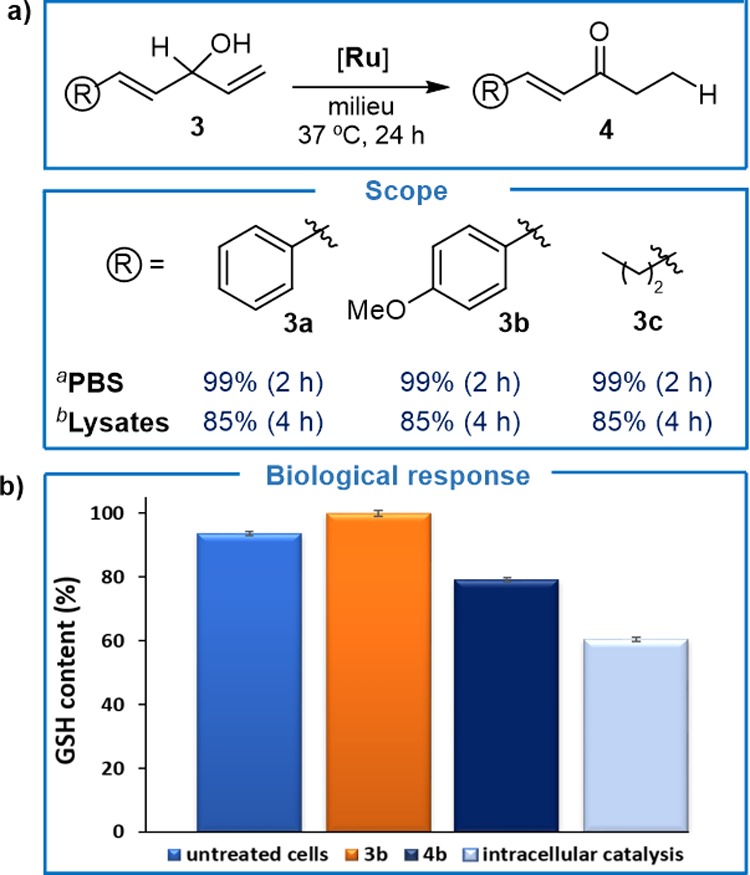

Finally, considering the well-known Michael type of reactivity of α,β-unsaturated systems, especially for thiol nucleophiles, we envisioned the use of our ruthenium-mediated isomerization to generate glutathione (GSH) depleting agents. We first confirmed that the ruthenium catalyst can efficiently convert diallyl alcohols of type 3 into the corresponding α,β-unsaturated ketones 4, even in cell lysates (Figure 4a). In a preliminary screening with HeLa cells, we could observe that some of these ketones, like 4b, promoted around 20% consumption of GSH. We therefore carried out a standard isomerization experiment in living cells using 50 μM of [Ru] and 100 μM of 3b. Analysis of the level of GSH after 6 h confirmed a substantial decrease of the intracellular GSH concentration (over 40% consumption of GSH, average of three experiments, Figure 4b). Given that the catalyst and the substrate do not alter the levels of GSH, the observed changes must arise from the in situ generation of the product. While these biological results should be viewed as a preliminary proof of concept, they demonstrate that the potential of metal catalysis to generate bioactive products inside cells is not limited to standard uncaging reactions.

Figure 4.

Generation of α,β-unsaturated ketones. (a) Scope of the ruthenium-catalyzed isomerization. aPerformed using 3 (0.2 mmol), solvent (1.0 mL) and [Ru] (2 mol %). b[Ru] (5 mol %), cells lysates 7 mg/mL. (b) Selected biological studies of GSH consumption using the transformation 3b→4b as a model. Reaction conditions: for intracellular catalysis, cells were incubated with [Ru] (50 μM) for 30 min, followed by two washings with DMEM and treatment with substrate 3b (100 μM), for 6 h. For control experiments, cells were incubated with substrate 3b or product 4b (100 μM) for 6 h. Error bars represent the standard error of three independent experiments.

In summary, we have developed the first metal-catalyzed isomerization reaction that can be achieved inside living cells. The reaction, promoted by a Ru(IV) complex, involves an intramolecular hydride-transfer process and takes place with a remarkable intracellular turnover. Our results demonstrate that typical intermediates of catalytic organometallic reactions, including ruthenium-hydride complexes, can survive the crowded atmosphere of cell lysates or even living cells. Importantly, the substrates can be engineered for the “in cellulo” generation of fluorescent products or bioactive molecules. Overall, these results open new avenues in this emerging research field at the boundary of metal catalysis and cellular biology, and promises to yield important applications in biomedicine.

Acknowledgments

Dedicated to Professor P. Espinet on the occasion of his 70th birthday. C.V. and M.T.-G. thank the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad for the Juan de la Cierva-Formación (FJCI-2017-33168) and Juan de la Cierva-Incorporación fellowships (IJCI-2015-23210), respectively. A.G.-G thanks the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte for the FPU fellowship (FPU17/00711). The authors thank R. Menaya-Vargas for excellent technical assistance and especially M. Marcos for excellent and essential contributions to the LC-MS analysis. This work has received financial support from the Spanish Government (SAF2016-76689-R, Orfeo-cinqa network CTQ2016-81797-REDC), the Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Ordenación Universitaria (2015-CP082, ED431C 2017/19), Centro Singular de Investigación de Galicia accreditation 2016–2019, ED431G/09), the European Union (European Regional Development Fund-ERDF), and the European Research Council (Advanced Grant No. 340055).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b00837.

Experimental procedures and cell studies (PDF)

Author Contributions

† C.V. and M.T.-G. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Berg J. M.; Tymoczko J. L.; Stryer L.. Biochemistry; W. H. Freeman: New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]; b Garcia-Viloca M.; Gao J.; Karplus M.; Truhlar D. G. How enzymes work: analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations. Science 2004, 303, 186–195. 10.1126/science.1088172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Küchler A.; Yoshimoto M.; Luginbühl S.; Mavelli F.; Walde P. Enzymatic reactions in confined enviornments. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 409–420. 10.1038/nnano.2016.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Agarwal P. K. Biophysical perspective on enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 438–449. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b01004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hegedus L. S.Transition metals in the synthesis of complex organic molecules; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 1999. [Google Scholar]; b Beller M.; Bolm C.. Transition metals for organic synthesis: building blocks and fine chemicals; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2008. [Google Scholar]; c Hartwig J. F.Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books: Mill Valley, CA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- a Sasmal P. K.; Streu C. N.; Meggers E. Metal complex catalysis in living biological systems. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1581–1587. 10.1039/C2CC37832A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yang M.; Li J.; Chen R. P. Transition metal-mediated bioorthogonal protein chemistry in living cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6511–6526. 10.1039/C4CS00117F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Vinogradova E. V. Organometallic chemical biology: an organometallic approach to bioconjugation. Pure Appl. Chem. 2017, 89, 1619–1641. 10.1515/pac-2017-0207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Rebelein J. G.; Ward T. R. In vivo catalyzed new-to-nature reactions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 53, 106–114. 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Martínez-Calvo M.; Mascareñas J. L. Organometallic catalysis in biological media and living settings. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 359, 57–79. 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Ngo A. H.; Bose S.; Do L. H. Intracellular chemistry: integrating molecular inorganic catalysts with living systems. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10584–10594. 10.1002/chem.201800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Bai Y.; Chen J.; Zimmerman S. C. Designed transition metal catalysts for intracellular organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 1811–1821. 10.1039/C7CS00447H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Soldevilla-Barreda J. J.; Metzler-Nolte N. Intracelullar catalysis with selected metal complexes and metallic nanoparticles: advances toward the development of catalytic metallodrugs. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 829–869. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Streu C.; Meggers E. Ruthenium-induced allylcarbamate cleavage in living cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 5645–5648. 10.1002/anie.200601752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yusop R. M.; Unciti-Broceta A.; Johansson E. M. V.; Sánchez-Martín R. M.; Bradley M. Palladium-mediated intracellular chemistry. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 239–243. 10.1038/nchem.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Völker T.; Dempwolff F.; Graumann P. L.; Meggers E. Progress towards bioorthogonal catalysis with organometallic compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10536–10540. 10.1002/anie.201404547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sánchez M. I.; Penas C.; Vázquez M. E.; Mascareñas J. L. Metal-catalyzed uncaging of DNA-binding agents in living cells. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 1901–1907. 10.1039/C3SC53317D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Tonga G. Y.; Jeong Y.; Duncan B.; Mizuhara T.; Mout R.; Das R.; Kim S. T.; Yeh Y.-C.; Yan B.; Hou S.; Rotello V. M. Supramolecular regulation of bioorthogonal catalysis in cells using nanoparticle-embedded transition metal catalysts. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 597–603. 10.1038/nchem.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Tomás-Gamasa M.; Martínez-Calvo M.; Couceiro J. M.; Mascareñas J. L. Transition metal catalysis in the mitochondria of living cells. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12538–12547. 10.1038/ncomms12538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Wang J.; Zheng S.; Liu Y.; Zhang Z.; Lin Z.; Li J.; Zhang G.; Wang X.; Li J.; Chen P. R. Palladium-triggered chemical rescue of intracellular proteins via genetically encoded allene-caged tyrosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15118–15121. 10.1021/jacs.6b08933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Miller M. A.; Askevold B.; Mikula H.; Kohler R. H.; Pirovich D.; Weissleder R. Nano-palladium is a cellular catalyst for in vivo chemistry. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15906–15918. 10.1038/ncomms15906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Stenton B. J.; Oliveira B. L.; Matos M. J.; Sinatra L.; Bernardes G. J. L. A thioether-directed palladium-cleavable linker for targeted bioorthogonal drug decaging. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 4185–4189. 10.1039/C8SC00256H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Martínez-Calvo M.; Couceiro J. R.; Destito P.; Rodríguez J.; Mosquera J.; Mascareñas J. L. Intracellular deprotection reactions mediated by palladium complexes equipped with designed phosphine ligands. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6055–6061. 10.1021/acscatal.8b01606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Clavadetscher J.; Hoffmann S.; Lilienkampf A.; Mackay L.; Yusop R. M.; Rider S. A.; Mullins J. J.; Bradley M. Copper catalysis in living systems and in situ drug synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15662–15666. 10.1002/anie.201609837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li S.; Wang L.; Yu F.; Zhu Z.; Shobaki D.; Chen H.; Wang M.; Wang J.; Qin G.; Erasquin U. J.; Ren L.; Wang Y.; Cai C. Copper-catalyzed click reaction on/in live cells. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 2107–2114. 10.1039/C6SC02297A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Destito P.; Couceiro J. R.; Faustino H.; López F.; Mascareñas J. L. Ruthenium-catalyzed azide-thioalkyne cycloadditions in aqueous media: a mild, orthogonal, and biocompatible chemical ligation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10766–10770. 10.1002/anie.201705006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Miguel-Ávila J.; Tomás-Gamasa M.; Olmos A.; Pérez P. J.; Mascareñas J. L. Discrete Cu(I) complexes azide-alkyne annulations of small molecules inside mammalian cells. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 1947–1952. 10.1039/C7SC04643J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indrigo E.; Clavadetscher J.; Chankeshwara S. V.; Lilienkampf A.; Bradley M. Palladium-mediated in situ synthesis of an anticancer agent. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 14212–14214. 10.1039/C6CC08666G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Destito P.; Sousa-Castillo A.; Couceiro J. R.; López F.; Correa-Duarte M. A.; Mascareñas J. L. Hollow nanoreactors for Pd-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura couplings and o-propargyl cleavage reactions in bio-relevant aqueous media. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 2598–2603. 10.1039/C8SC04390F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal C.; Tomás-Gamasa M.; Destito P.; López F.; Mascareñas J. L. Concurrent and orthogonal gold(I) and ruthenium(II) catalysis inside living cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1913–1921. 10.1038/s41467-018-04314-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bose S.; Ngo A. H.; Do L. H. Intracellular transfer hydrogenation mediated by unprotected organoiridium catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8792–8795. 10.1021/jacs.7b03872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Coverdale J. P. C.; Romero-Canelón I.; Sanchez-Cano C.; Clarkson G. J.; Habtemariam A.; Wills M.; Sadler P. J. Asymmetric transfer hydrogenation by synthetic catalysts in cancer cells. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 347–354. 10.1038/nchem.2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a McGrath D. V.; Grubbs R. H. The mechanism of aqueous ruthenium(II)-catalyzed olefin isomerization. Organometallics 1994, 13, 224–235. 10.1021/om00013a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Cadierno V.; García-Garrido S. E.; Gimeno J.; Varela-Álvarez A.; Sordo J. A. Bis(allyl)-ruthenium(IV) complexes as highly efficient catalysts for the redox isomerization of allylic alcohols into carbonyl compounds in organic and aqueous media: scope, limitations, and theoretical analysis of the mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 1360–1370. 10.1021/ja054827a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c García-Álvarez J.; Gimeno J.; Suárez F. J. Redox isomerization of allylic alcohols into carbonyl compounds catalyzed by the ruthenium(IV) complex [Ru(η3: η3-C10H16)Cl(κ2O-O-CH3CO2)] in water and ionic liquids: highly efficient transformations and catalysts recycling. Organometallics 2011, 30, 2893–2896. 10.1021/om200184v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Lorenzo-Luis P.; Romerosa A.; Serrano-Ruiz M. Catalytic isomerization of allylic alcohols in water. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 1079–1086. 10.1021/cs300092d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Ahlsten N.; Bartoszewicz A.; Martín-Matute B. Allylic alcohols as synthetic enolate equivalents: isomerization and tandem reactions catalysed by transition metal complexes. Dalton Trans 2012, 41, 1660–1670. 10.1039/c1dt11678a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh B.; Steed J. W.; Tocher D. A. Mono- and bi-dentate carboxylato complexes of ruthenium (IV). J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1993, 0, 327–335. 10.1039/dt9930000327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [IrCl2Cp*]2 has been used in the isomerization of allylic alcohols in an acetone/water mixture (2:1):; Erbing E.; Vázquez-Romero A.; Gómez A. B.; Platero-Prats A. E.; Carson F.; Zou X.; Tolstoy P.; Martín-Matute B. General, simple, and chemoselective catalysts for the isomerization of allylic alcohols: the importance of the halide ligands. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 15659–15663. 10.1002/chem.201603825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlsten N.; Lundberg H.; Martín-Matute B. Rhodium-catalysed isomerisation of allylic alcohols in water at ambient temperature. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1628–1633. 10.1039/c004964f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- We also recovered significant amount of substrate 1g.

- a Weiss J. T.; Dawson J. C.; Macleod K. G.; Rybski W.; Fraser C.; Torres-Sánchez C.; Patton E. E.; Bradley M.; Carragher N. O.; Unciti-Broceta A. Extracellular palladium-catalysed dealkylation of 5-fluoro-1-propargyl-uracil as a bioorthogonally activated prodrug approach. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3277–3285. 10.1038/ncomms4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Weiss J. T.; Dawson J. C.; Fraser C.; Rybski W.; Torres-Sánchez C.; Bradley M.; Patton E. E.; Carragher N. O.; Unciti-Broceta A. Development and bioorthogonal activation of palladium-labile prodrugs of gemcitabine. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5395–5404. 10.1021/jm500531z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li J.; Chen R. Development and application of bond cleavage reactions in bioorthogonal chemistry. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 129–137. 10.1038/nchembio.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Rubio-Ruiz B.; Weiss J. T.; Unciti-Broceta A. Efficient palladium-triggered release of vorinostat from a bioorthogonal precursor. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 9974–9980. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Clavadetscher J.; Indrigo E.; Chankeshwara S. V.; Lilienkampf A.; Bradley M. In-cell dual drug synthesis by cancer-targeting palladium catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 6864–6868. 10.1002/anie.201702404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Völker T.; Meggers E. Chemical activation in blood serum and human cell culture: improved ruthenium complex for catalytic uncaging of alloc-protected amines. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 1083–1086. 10.1002/cbic.201700168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Bray T. L.; Salji M.; Brombin A.; Pérez-López A. M.; Rubio-Ruiz B.; Galbraith L. C. A.; Patton E. E.; Leung H. Y.; Unciti-Broceta A. Bright insights into palladium-triggered local chemotherapy. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 7354–7361. 10.1039/C8SC02291G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.