Abstract

Generation of protective immune responses requires coordinated stimulation of innate and adaptive immune responses. An important mediator of innate immunity is STimulator of INterferon Genes (STING, MPYS, MITA), a ubiquitously but differentially expressed adaptor molecule that functions in the relay of signals initiated by sensing of cytosolic DNA and bacterial cyclic-dinucleotides (CDNs). While systemic expression of STING is required for CDN-aided mucosal antibody responses, its function in B cells in particular is unclear. Here we show that B cells can be directly activated by CDNs in a STING-dependent manner in vitro and in vivo. Direct activation of B cells by CDNs results in upregulation of costimulatory molecules and cytokine production, and this can be accompanied by caspase-dependent cell death. CDN-induced cytokine production by B cells and other cell types also contributes to activation and immune responses. Type I IFN is primarily responsible for this indirect stimulation, although other cytokines may contribute. BCR and STING signaling pathways act synergistically to promote antibody responses, independent of type I IFN. B cell expression of STING is required for optimal in vivo IgG and mucosal IgA antibody responses induced by T cell-dependent antigens and ci-di-GMP, but plays no discernable role in antibody responses in which alum is used as adjuvant. Thus, STING functions autonomously in B cells responding to CDNs and its activation synergizes with antigen receptor signals to promote B cell activation.

INTRODUCTION

Cyclic-dinucleotides (CDNs), classified as alarmins, function in the innate immune response to host damage and infection. CDNs can be pathogen-derived or synthesized in metazoans in response to injury (1–4). Previous findings have shown that CDNs have immunomodulatory activity. When administered via mucosal routes, CDNs significantly increase antigen-specific immune responses and provide protection in bacterial disease models (5–7). Cyclic-di-GMP (CDG), a common bacterial derived CDN, has been shown to have adjuvant activity, promoting balanced Th1, Th2 and Th17 responses, and robust mucosal and systemic antibody responses in mice (8–12).

The most well-characterized intracellular sensor of CDNs is the Stimulator of IFN Genes (STING), also referred to as MYPS, Mediator of IRF3 activation (MITA), and Tmem173 (13–16). STING functions in the relay of signals generated upon cytosolic DNA sensing, coupling DNA detection to downstream production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (17). Subsequent to the CDN binding, STING becomes activated leading to its translocation from the endoplasmic reticulum to the ER-Golgi intermediate compartments (ERGIC), and engagement of TBK1 and downstream IRF3 and NFκB pathways, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as type I interferon, IL-6 and TNF-α (15, 17–20).

The STING signaling pathway has been shown to be indispensable for CDN-enhancement of Ag-specific Ab responses in vivo (12). STING function in this context is reportedly independent of type I interferon, but is a partially dependent on TNF-α (12, 21). The mechanisms by which STING signaling enhances antibody responses are still unclear. A recent study suggests that the answer may lie in in part in its ability to promote antigen uptake by CD11c+ cells. Deletion of STING in CD11c+ cells resulted in reduced antibody responses following CDN/Ag immunization (22).

STING is highly expressed in B cells (13). In work described here, we examined the direct effects of CDNs on B cells, and the role of STING in responses observed. We further explored the importance of B cell intrinsic STING in in vivo antibody responses promoted by CDNs. Results demonstrate that B cells are activated by CDNs in vitro and in vivo and this response is STING dependent. While largely cell intrinsic and cytokine independent, responses can be modulated by type 1 interferon. Importantly, antigen and CDN-induced signals act synergistically to stimulate B cell activation. Finally, B cell intrinsic STING is required for optimal CDG adjuvant effects on in vivo antibody responses to thymus dependent antigens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Eight- to twelve-week-old mice were used for all experiments. STINGflox/flox mice were generated by deleting the neo cassette from Tmem173 <tm1Camb> mice (17), This was achieved by crossing Tmem173 <tm1Camb> with a FLP1 recombinase line (B6;SJL-Tg(ACTFLPe)9205Dym/J). Total STING KO mice were generated by crossing STINGflox/flox mice with a Cre deleter line (B6.C-Tg(CMV-cre)1Cgn/1). B cell targeted STING KO mice were generated by crossing STINGflox/flox mice with mb-1 cre mice (23). C57BL/6 mice were used as wild-type (WT) controls during CDN/OVA immunization studies. Separate experiments showed that STINGflox/flox mice yield similar responses to CDN/OVA immunization as C57BL/6 mice (Supplemental Figure 1). In some instances, MD4 B cell (anti-HEL) antigen receptor transgenic mice (24) were used as B cell donors. MD4 mice were crossed with total STING KO mice to generate MD4 STING KO mice. Congenically marked CD45.1 C57BL/6 (B6.SJL-PtprcaPepb/BoyJ) B cells were used as WT controls in co-culture experiments. TNFR KO (B6.129S-Tnfrsf1atm1lmx Tnfrsf1btm1mx/J) and IFNAR KO (B6(Cg)-Ifnar1tm1.2Ees/J) mice were used to study cytokine dependence and IFNAR KO mice crossed with total STING KO mice to generate IFNAR STING DKO mice for in vitro culture experiments. All mice other than Tmem173 <tm1Camb> were originally purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were housed and bred in the Animal Research Facility at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and National Jewish Health. All experiments were performed in accordance with the regulations and approval of University of Colorado and National Jewish Health Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunization and sample collection

Prior to i.n. immunization mice were anesthetized with isofluorane in an E-Z anesthesia system (Euthanex, Palmer, PA). Mice received three bi-weekly intranasal (i.n.) immunizations administered drop-wise at 40μl/nostril of endotoxin-low OVA (20μg/ mouse) in PBS with or without CDG (5μg/ mouse, ci-di-GMP; Biolog life science institute, Federal Republic of Germany). Endotoxin was removed (<0.1 EU) from OVA (Sigma) as described (25) and in some cases endotoxin-low OVA was purchased (Biovendor, Asheville, NC). Serum was collected at the indicated time points and nasal passages lavaged at the final time point with 1ml of ice-cold PBS. To examine the general ability of mice to mount antibody responses, mice were immunized IP with OVA-NP4.5 (20μg/mouse) in PBS alone or in Alhydrogel (200 μg alum vaccine adjuvant; invivogen, San Diego, CA), with Ficoll-NP40 (25μg/mouse: Biosearch Technologies, Novato, CA), LPS-NP0.6 (5μg/mouse: Biosearch Technologies, Novato, CA) or 5×107 SRBC (Colorado Serum Company, Denver, CO). Serum was collected at the indicated time points.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

For detection of OVA-specific antibodies, microtiter plates were coated overnight with 10 μg/ml OVA in PBS at 4ºC and blocked with 2% BSA in PBS 0.05% Tween-20 for >1hr at RT. For detection of NP-specific antibodies, microtiter plates were coated with 10 μg/ml BSA-NP2 or BSA-NP17 in PBS and blocked with 2% BSA in PBS 0.05% Tween-20. Serial dilutions of mouse serum in PBS were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. IgG antibodies were detected with goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL), IgM antibodies were detected with goat anti-mouse IgM-HRP (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL), IgA antibodies were detected with goat anti-mouse IgA-HRP (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL), IgG1 antibodies were detected with goat anti-mouse IgG1-HRP (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL), and IgG2a/c antibodies were detected with goat anti-mouse IgG2a/c-HRP (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Between all steps the plates were washed 4 times with PBS-0.05% Tween-20. The ELISA was developed with TMB single solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and the reaction was stopped with 1N H2PO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The OD was determined at 450 nm using a VERSAMax plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and the data were analyzed with Softmax software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The half-max reciprocal of dilution was calculated by using the reciprocal of the dilution factor at a set half-max value for each group at each time point. In order to normalize the assays performed on different days, a single serum sample collected on Day 35 from the WT mice that were immunized with OVA in the presence of CDG was run with each group.

Hemagglutination assay

Serum was serially diluted (two-fold) in PBS in V-bottomed microtiter plates in a 50µl volume. Fifty µl of 0.5% SRBC suspension in PBS was then added to each well and plates were incubated at 37°C for one hour. The hemagglutination titer was defined as the reciprocal value of the highest serum dilution at which hemagglutination of SRBC was detected.

In vitro stimulation with CDG

Single cell suspensions of splenic cells were prepared and in some experiments red blood cells were lysed using ammonium chloride TRIS. In most experiments, live cells were isolated using Lympholyte M kit (Cedarlane, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) and B cells were purified by CD43 negative selection using MACS Miltenyi microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec Inc, San Diego, CA). Resultant populations were routinely >97% B cells based on B220 staining and FACS analysis. Ex vivo B cells and splenocytes were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 10% FBS, sodium pyruvate (1mM), L-glutamine (2 mM), 1% penicillin/ streptomycin, 2-ME (50μM), HEPES buffer (10mM), 1% nonessential amino acids.

Ex vivo B cells or splenocytes were seeded (3 ×105 cells/100 μl/well) in a 96-well flat-bottom plate and stimulated with various concentrations of CDG for the indicated time. Additional stimuli were used at the following concentrations: Zymosan (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (10μg/100μl), IL-4 (Supernatant from a J558L culture, 1:200 dilution), Hen Egg Lysozyme (HEL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (1μg/100μl), F(Ab)2 goat anti-mouse IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) (1μg/100μl), LPS (1μg/100μl), 2’, 3’ cGAMP (c[G(2’,5’)pA(3’,5’)p] Biolog life science institute, Federal Republic of Germany) (3μg/100μl), 3’, 3’ cGAMP (c-(ApGp), Biolog life science institute, Federal Republic of Germany) (3μg/100μl), CDA (ML RR-S2 CDA sodium salt, Sigma) (3μg/100μl). In co-culture experiments 3×105 of each cell type was added/well in a total volume of 100μl. In experiments using z-vad (Z-VAD-FMK, Invivogen, San Diego, CA), z-vad was added 1 hr prior to stimulation at the indicated concentrations.

In vivo stimulation with CDG

Mice were injected IP with CDG (125 μg/mouse) in 200 μl PBS, or PBS alone. After 18 hrs, mice were sacrificed, spleens and peritoneal lavages were collected and cells were assessed for upregulation of CD86. In some experiments non-irradiated STING KO or WT mice were co-transferred with purified WT MD4 and MD4 STING KO B cells at a 1:1 ratio. Donor B cells were labeled with CellTrace Violet (Molecular Probes) at 5μM (MD4 WT) or 1μM (MD4 STING KO) for 4 min at RT prior to transfer. 2–4×106 B cells in 200 μl PBS were adoptively transferred by IV injection. Twenty-four hours post-transfer recipient mice were injected IP with CDG (125 μg/mouse), HEL (20 μg/mouse) or CDG and HEL in 200 µl PBS, or with PBS alone. After 18 hrs, mice were sacrificed and splenic cells were assessed for upregulation of CD86. In other experiments, peritoneal B cells were enriched from peritoneal lavage from WT and STING KO mice by staining cells with a cocktail of biotinylated anti-F4/80 (BM8; eBioscience), anti-CD3ε (500A2; BD bioscience) and anti-Gr-1(RB6–8C5; BD bioscience) and purified via negative selection using anti-biotin magnetic bead separation (Miltenyi Biotec Inc, San Diego, CA). These B cells were labelled differentially with CellTrace Violet, mixed 1:1 and 1×106 cells were adoptively transferred into total STING KO mice by IP injection. 1hr post transfer the mice were injected IP with CDG (125 μg/mouse) in 200 μl PBS, or PBS alone. After 18 hrs, mice were sacrificed and peritoneal lavages were collected and cells were assessed for upregulation of CD86.

Flow cytometric assay

Single cell suspensions of splenic cells were prepared and red blood cells were lysed using ammonium chloride TRIS. Cells were resuspended in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.02% sodium azide or cells were taken directly out of cell culture and incubated with optimal amounts of antibodies. For analysis of cell surface markers, cells were stained with antibodies directed against the following molecules: B220 (RA3–6B2, BD Bioscience), CD86 (GL1, BD biosciences), CD3ε (BD biosciencs; 145–2C11), Gr-1 (BD bioscience; RB6–8C5), CD23 (BD biosciences; B3B4), CD93 (BD bioscience; AA4.1), CD45.1 (A20, BD bioscience, San Jose, CA). Follicular B cells were defined as B220+CD23+CD93−, marginal zone cells were defined as B220+CD23−CD93−, and transitional B cells were defined as B220+CD93med. Dead cells were gated out by excluding Annexin V+ stained cells. FACS was performed using a Fortessa X-20 cytometer (BD biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Flowjo, Ashland, OR).

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance was determined using the unpaired Student’s t-test Two-way ANOVA was used to compare Ab responses (Graphpad Prism 5.0; Graphpad).

RESULTS

Direct stimulation of ex vivo B cells with ci-di-GMP results in STING-dependent activation

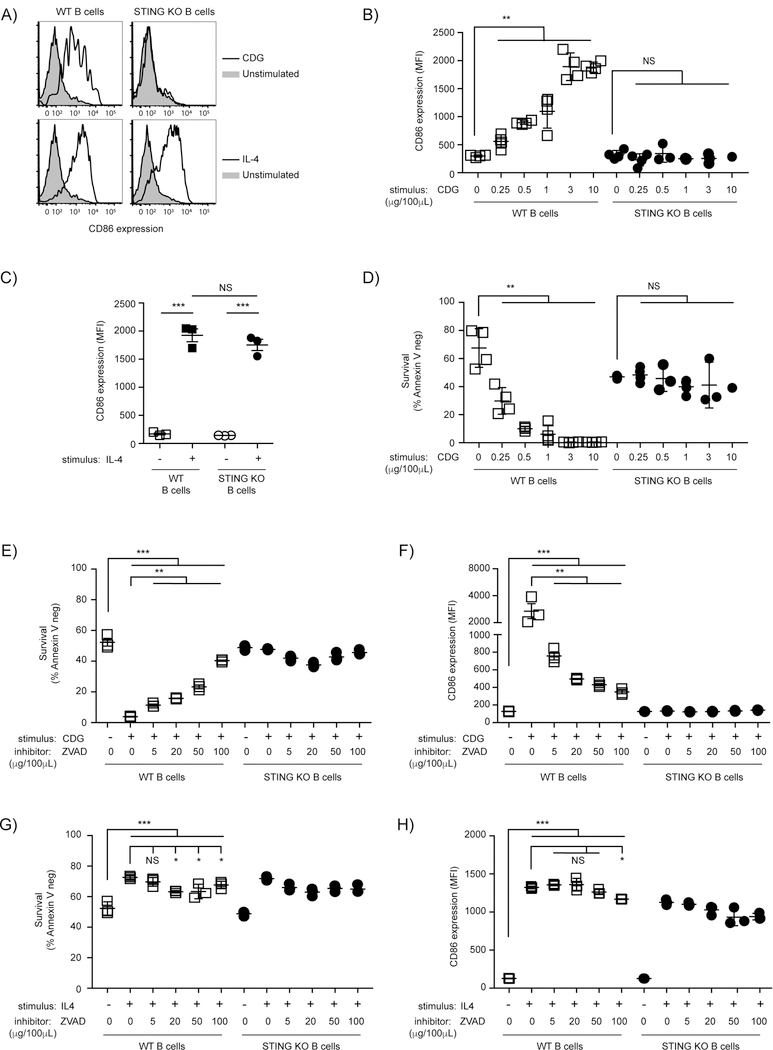

A recent report demonstrated that STING expression is required for CDG-enhancement of Ab responses (12). It is unclear whether bacterial CDN adjuvant, CDG, directly stimulates B cells and whether this requires STING. To test this, B cells were isolated from WT and total STING KO mice and stimulated with increasing concentrations of CDGs for 18hrs before CD86 expression was measured. WT B cells exhibited upregulation of CD86 expression that was dose-dependent, whereas increasing concentrations of CDGs had no effect on activation of STING KO B cells (Fig. 1A-B). Kinetic analysis revealed a significant fold change in CD86 expression as early as 13 hrs post stimulation (data not shown). To exclude the possibility that STING KO B cells have an inherent defect in the ability to upregulate CD86 following stimulation, B cells were stimulated with the STING-independent IL4 and CD86 expression was assessed. The resultant responses did not require STING (Fig. 1A and C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that B cells have the ability to become activated upon direct stimulation with CDGs in vitro, and that the STING signaling pathway is essential for this activation.

Figure 1: Direct stimulation with ci-di-GMP results in STING-dependent activation and death of ex vivo B cells.

A-D) WT and STING KO B cells were cultured for 18 hrs with the indicated concentrations of CDG or IL4 as a positive control before analysis (n=3–4). A) Representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown from 3 µg CDG/100µl cultures. B) CD86 expression (MFI) plotted after stimulation with indicated concentrations of CDG; (C) CD86 expression (MFI) after IL4 stimulation; (D) B cell survival (B220+ Annexin V−) after stimulation with indicated concentrations of CDG. E-H) WT and STING KO B cells were cultured for 18 hrs with 3 µg/100µl CDG or IL4, in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of ZVAD (n=3); B cell survival (B220+ Annexin V−) after stimulation with (E) CDG or (G) IL4; CD86 expression (MFI) after stimulation with (F) CDG or (H) IL4;. Data shown are representative of at least three independent replicate experiments. Bars in B-H represent mean ± SEM. NS, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 using an unpaired Student’s t test.

CDG-induced activation of the STING signaling pathway results in a B cell intrinsic cell death response

We observed that stimulation of B cells in vitro with CDGs led to a loss of viability of STING-sufficient B cells but not in STING deficient B cells. STING has been shown to promote cell death in several biological systems and CDNs have also been shown to promote cell death, including in B cells (26–31). The loss of cell viability increases with increased CDG concentration and occurred only in WT B cells (Fig 1D). Inhibition of caspase activation by preincubation with z-vad-fmk before CDG stimulation inhibited cell death in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 1E). Surprisingly, z-vad-fmk prevented CD86 upregulation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 1F), demonstrating that both STING-mediated cell death and B cell activation are dependent on caspase activation. The observed inhibition of CDG-induced CD86 upregulation by z-vad-fmk appears specific to STING-mediated upregulation of CD86, and not an off-target effect of the inhibitor, since at none of the z-vad-fmk concentrations used was the IL-4-induced response inhibited (Fig 1G-H).

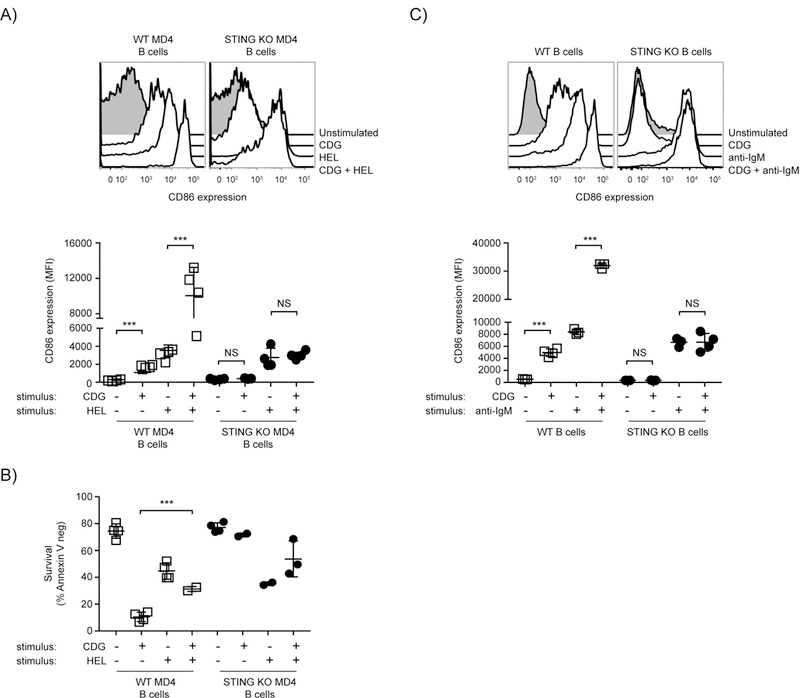

Simultaneous BCR and STING signaling results in synergistic upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules

CDN-induced STING-mediated induction of B cell death seemed inconsistent with a positive role for STING in B cell responses. We hypothesized that perhaps CDN and BCR signals might be complementary, resulting in enhance cell activation and no cell death. To test this possibility Hen Egg Lysozyme-specific B cells were isolated from STING sufficient or deficient BCR transgenic MD4 mice. B cells from MD4 STING sufficient and MD4 STING deficient mice (STING KO MD4) were stimulated with HEL or CDGs separately or in combination. While both STING sufficient and STING deficient MD4 B cells upregulated CD86 after antigen (HEL) exposure, only MD4 STING sufficient B cells became activated in response to CDG stimulation, and this response was STING-dependent (Fig. 2A). Stimulation of STING sufficient MD4 B cells, and not STING deficient MD4 cells with CDG in the presence of their Ag resulted in synergistic upregulation of CD86 (Fig 2A). We also observed a partial protection of CDG-induced cell death in these experiments (Fig. 2B). Comparable results were obtained when we stimulated WT and STING KO B cells with CDGs or anti-IgM alone or in combination for 18hr. We found that in STING-sufficient B cells CDGs and F(ab’)2 anti-IgM stimulation were synergistic in the induction of CD86 upregulation. This did not occur in STING KO B cells (Fig. 2C). To test if this is unique to CDG or if it is a general feature of STING biology we tested 3 additional STING ligands, including the c-GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS) product 2’,3’ cGAMP, for their ability to activate B cells and synergize with BCR stimulation. All 3 STING ligands induced significant CD86 upregulation and synergized with BCR stimulation to further upregulate CD86 expression (Supplemental Fig 2). Together these data suggest that the BCR and STING signaling pathways work cooperatively to induce B cell activation and that BCR stimulation can provide alternative signals that mitigate death signals induced by activation of the STING signaling pathway.

Figure 2: BCR and STING signaling results in cooperative B cell activation and partial rescue of STING-induced cell death.

A,B) WT MD4 and STING KO MD4 B cells were cultured with 1 µg/100 µl HEL, 3 µg/100 µl CDG or both stimuli (n=4) for 18 hrs. (A top) representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown, (A bottom) CD86 expression (MFI). (B) B cell survival (B220+ Annexin V−) after 18 hrs. C) WT and STING KO B cells were cultured with 1 µg/100 µl anti-IgM F(ab)’2, 3 µg/100 µl CDG or both stimuli (n=4) for 18 hrs. (C top) representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown, (C bottom) CD86 expression (MFI). Data shown are representative of at least three independent replicate experiments. Bars in A-C represent mean ± SEM. NS, P>0.05; ***, P < 0.001 using an unpaired Student’s t test.

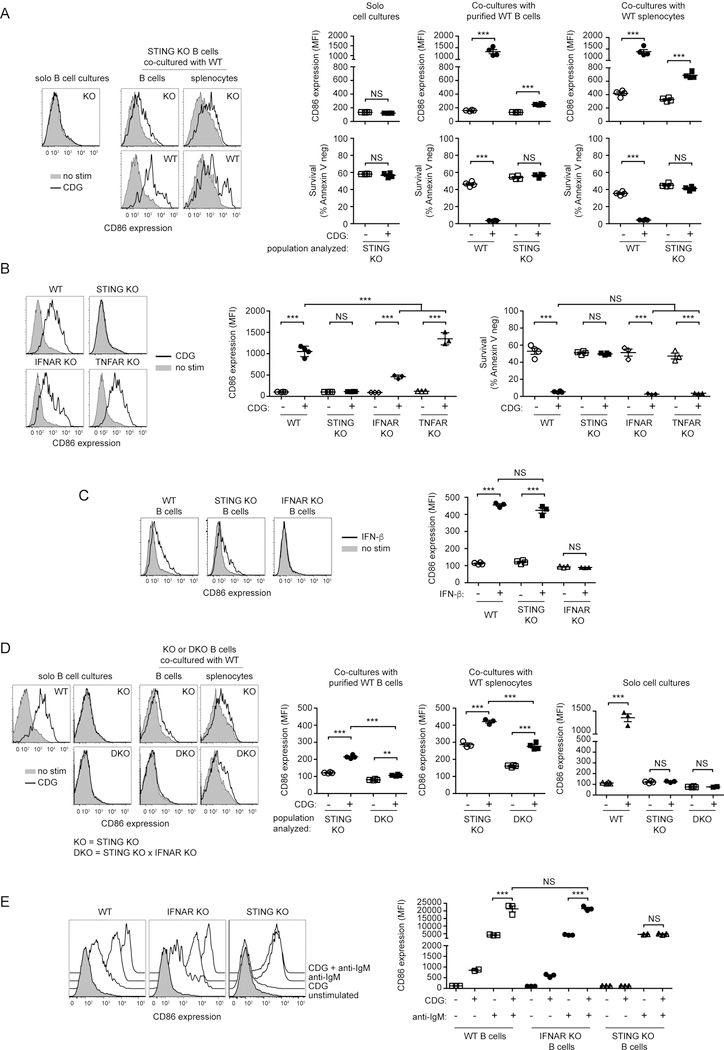

CDG-induced activation of B cells occurs by cell intrinsic and autocrine mechanisms

Previous studies have shown that B cell upregulation of costimulatory molecules expression following exposure to PAMPs such as TLR7 ligands, can be indirect, resulting from autocrine stimulation by type I interferon (32). To test if CDG-stimulated B cells secrete cytokines that can cause upregulation of CD86 on B cells, we co-cultured STING-deficient B cells with STING sufficient B cells or STING-sufficient splenocytes (Fig 3A). While CDG did not induce upregulation of CD86 by STING-deficient B cells cultured alone, when these cells were co-cultured with WT B cells or WT splenocytes a modest but significant upregulation of CD86 on STING-deficient B cells was seen. While the co-cultured WT B cells died after exposure to CDG we did not observe a change in viability of the STING-deficient B cells. These findings demonstrate CDG induces production of a factor, possibly type 1 interferon, capable of stimulating upregulation of CD86 expression by B cells.

Figure 3: CDG-induced activation of B cells occurs by both B cell intrinsic and autocrine mechanisms in vitro.

(A) STING KO B cells were culture alone (solo) or co-cultured with WT CD45.1 B cells or WT CD45.1 splenocytes for 18 hrs in the presence or absence of 3 µg/100 µl CDG (n=4). (left) representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown; (right top panels) CD86 expression (MFI) of the indicated populations after 18 hrs; (right bottom panels) B cell survival (B220+ Annexin V−) of the indicated populations after 18 hrs. (B) WT, STING KO, IFNAR KO and TNFAR KO B cells were cultured with or without 3 µg/100 µl CDG (n=3–4) for 18 hrs. (left) representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown; (middle) CD86 expression (MFI) and (right) B cell survival (B220+ Annexin V−). (C) WT, STING KO and IFNAR KO cells were cultured the presence or absence of 1000U/100 µl rIFNβ (n=3–4) for 18hrs. (left) representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown; (right) CD86 expression (MFI) after 18 hrs. (D) STING KO and STING x IFNAR DKO B cells were culture alone (solo) or co-cultured with WT CD45.1 B cells or WT CD45.1 splenocytes for 18 hrs in the presence or absence of 3 µg/100 µ L CDG (n=3–4). (left) representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown; (right) CD86 expression (MFI) of the indicated populations after 18 hrs. (E) WT, STING and IFNAR KO B cells were cultured with 1 µg/100 µl anti-IgM F(ab)’2, 3 µg/100 µlCDG or both stimuli (n=4) for 18 hrs. (left) representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown, (right) CD86 expression (MFI) after 18 hrs. Data shown are representative of at least three independent replicate experiments. Bars in A-E represent mean ± SEM. NS, P>0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 using an unpaired Student’s t test.

Type I interferons have been shown to influence B cell survival, activation, and proliferation (33) and therefore we examined the role of type I interferon in CDG-induced B cell activation, by using B cells from mice deficient in the receptor for type I IFNs (IFNAR KO). Since TNFα has previously been shown to mediate, in part, the CDG adjuvant effect (12) we also assayed B cells from mice deficient in the TNFα receptor (TNFAR KO). Purified B cells from WT, STING KO, IFNAR KO and TNFAR KO were stimulated for 18 hrs with CDG and CD86 expression and B cell survival (Fig 3B) was assayed. While TNFAR KO B cells respond slightly better to CDG than WT B cells, CD86 upregulation was significantly lower in IFNAR KO B cells. B cells that are unable to respond to type I IFN or TNF-α died with a similar frequency as WT B cells following CDG exposure. These results suggest that STING-mediated type I IFN production is partly responsible for the observed B cell activation following CDG stimulation, acting in an autocrine or paracrine manner, but these cytokines are not involved in CDG induction of cell death. To further examine this, we set out to determine if type I INF is solely responsible for the observed CD86 upregulation by STING KO B cells following CDG stimulation in the co-culture experiments. First, we verified that STING KO B cells do not have an inherent defect in their ability to respond to type I IFN. WT and STING KO B cells that were stimulated with IFN-β exhibited similar levels of upregulation of CD86 expression (Fig. 3C). Next, we generated STING and IFNAR double knockout (DKO) mice and compared responses of STING/IFNAR DKO B cells and STING KO B cells under similar co-culture conditions as in Fig 3A. When co-cultured with WT B cells, the CD86 upregulation that was observed on STING KO B cells following CDG stimulation was almost completely absent in DKO B cells (Fig 3D). When co-cultured with WT splenocytes and stimulated, DKO B cells underwent a reduced CD86 upregulation response compared to STING KO B cells, although significant CD86 upregulation was detected. These results show that while B cell intrinsic effects are mainly responsible for the observed increase in costimulatory molecule expression, type I IFN makes a significant contribution to this upregulation. Additional soluble factors produced by non-B cells may also play a minor role in promoting upregulation.

Since type I IFN was found to contribute, albeit modestly, to the observed CDG-induced B cell activation in vitro, we wanted to determine if the observed synergistic effect of BCR stimulation with CDG stimulation on costimulatory molecule expression is a B cell intrinsic effect of STING signaling or if it is the consequence of type I IFN signaling. While IFNAR KO B cells respond to CDG stimulation with reduced CD86 upregulation, the synergistic effect of BCR stimulation with CDG stimulation was comparable to that observed in WT B cells (Fig 3E). Thus, this synergism is a consequence of cooperative actions of STING and BCR signaling pathways within the B cell.

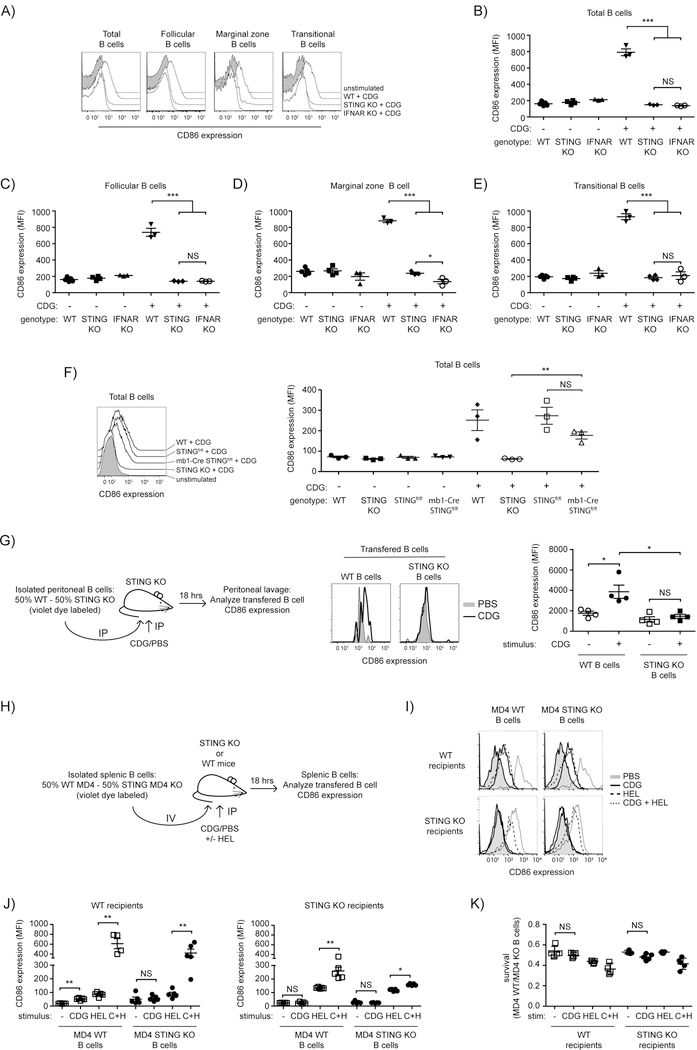

The role of type 1 interferon in CDG activation of B cells in vivo

As demonstrated above, CDG activation of isolated B cells in vitro is largely type I interferon independent. However, the relative roles of the B cell intrinsic versus cytokine mediated responses in in vivo activation of B cells is unclear. Since many cell types are likely to produce type I IFN in response to CDG in vivo, cytokines seem likely to play a more prominent role there. To determine whether B cells become activated in vivo following peritoneal CDG administration and whether this response is STING-dependent, WT and STING KO mice were injected intraperitoneally with 125µg of CDGs and splenic B cell upregulation of CD86 assessed. In STING sufficient mice injected with CDGs, B cells exhibited significant upregulation of CD86 while no change in expression of CD86 was seen in STING KO mice (Fig. 4A-B). Thus, STING is required at the organismal level to support CDG-induced B cell activation in vivo.

Figure 4: B cell intrinsic and extrinsic STING is required for the activation of B cells following CDG exposure in vivo.

A-E) WT, STING KO and IFNAR KO mice were injected IP with PBS or 125 µg CDG and 18 hrs post injection splenocytes were isolated and CD86 expression was determined on B cell subsets (n=3–4). (A) representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown; (B) CD86 expression (MFI) on all B cells (gated on B220+ Annexin V−); (C) CD86 expression (MFI) on follicular B cells (gated on B220+ CD93− CD23+ Annexin V−); (D) expression (MFI) on marginal zone B cells (gated on B220+ CD93− CD23lo Annexin V−); (E) CD86 expression (MFI) on transitional B cells (gated on B220+ CD93+ Annexin V−). F) WT, STING KO, STINGfl/fl and mb1-Cre STINGfl/fl mice were injected IP with PBS or 125 µg CDG and 18 hrs post injection splenocytes were isolated and CD86 expression was determined on B cells (n=3). Left: representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown; right, CD86 expression (MFI) on all B cells (gated on B220+ Annexin V−); G) WT and KO peritoneal B cells were differentially labelled and transferred IP into STING KO mice (n=4). 1hr post transfer the mice were injected with 125 µg CDG IP, 18 hrs later a peritoneal lavage was performed and CD86 expression was determined of the transferred B cells. (left) schematic representation of the experiment; (middle) representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown; (left) CD86 expression (MFI) of the indicated populations. H-K) WT MD4 and STING KO MD4 B cells were differentially loaded with violet dye and adoptively co-transferred (1:1) into WT or STING KO mice (n = 4–5). 24 hrs later mice were injected with PBS, 125 µg CDG, 20 µg HEL or both. After 18 hrs splenic B cells were analyzed for CD86 expression. (H) schematic representation of the experiment; (I) representative histograms (gated on B220+ Annexin V−) for CD86 staining are shown; (J left) CD86 expression (MFI) of the indicated populations in WT recipients; (J right) CD86 expression (MFI) of the indicated populations in KO recipients; K) ratio of annexin V− WT MD4 to STING KO MD4 B cells in the indicated recipients. Data shown are representative of at least two independent replicate experiments. Bars in B-G and J-K represent mean ± SEM. NS, P>0,05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 using an unpaired Student’s t test.

It is well known that B cell subpopulations respond differently to innate immune stimuli. To determine which B cell subpopulations respond to CDG stimulation in vivo, we assessed CD86 expression on splenic follicular, marginal zone, and transitional B cells following CDG treatment. We observed similar upregulation of CD86 on all B cell subpopulations analyzed (Fig. 4A-E).

To determine whether type I interferon is required for systemic CDG induction of B cell activation in vivo, IFNAR KO mice were also injected with CDG and upregulation of CD86 expression assessed. We observed no upregulation of CD86 by B cells in IFNAR KO mice (Fig. 4A-B). Thus, under the conditions used type I IFN is required for CDG-induced activation of splenic B cells in vivo.

To directly test if the there is a requirement for STING expression in B cells for systemic CDG induction of B cell activation in vivo we generated B cell targeted STING KO mice by crossing STINGfl/fl mice to mb1-Cre mice. Consistent with a role of STING-dependent type I IFN production by cells in the peritoneum and indirect activation of B cells by type I IFN CD86 expression was significantly increased on B cells from B cell targeted STING KO mice (Fig 4F).

It seems likely that inability to activate B cells in vivo via the type 1 interferon independent pathway is the consequence of inability to achieve stimulatory local concentrations of CDG. Work by others has shown that rapid diffusion of small molecules from the site of injection into the blood limits their direct potency but causes systemic responses (21). To further test this possibility, we explored the ability of intraperitoneal injection the CDG to induce CD86 expression by the cytokine-independent pathway, reasoning that by this approach we could achieve high local CDG concentrations. Peritoneal B cells from WT and STING KO mice were isolated, loaded with different concentrations of Celltracker violet to allow later interrogation of different populations and co-transferred at a 1:1 ratio in STING KO mice by IP injection. One hour later mice were given an IP injection of CDG or PBS. After 18 hrs, we observed upregulation of CD86 on WT but not STING KO peritoneal B cells in STING KO mice that received CDGs (Fig. 4G) demonstrating that B cells can be activated by CDG in vivo by mechanisms that do not require type 1 IFN signaling. Taken together, these data suggest that both B cell intrinsic and extrinsic STING-mediated responses contribute to B cell activation following CDG stimulation in vivo.

B cell intrinsic and extrinsic STING responses contribute to CDG activation of antigen-specific B cells in vivo

Based on our previous observations utilizing co-culture, we sought to determine the requirements for B cell intrinsic and extrinsic STING in activation of antigen-specific B cells following in vivo CDG exposure. To test this, differentially labelled MD4 STING sufficient and MD4 STING KO B cells were isolated and co-transferred at a 1:1 ratio intravenously (i.v.) into both WT and STING KO recipient mice (Fig 4H). These mice were then i.p. injected with PBS, CDG, HEL, or a combination and changes in CD86 expression by B cells were assessed. STING-sufficient MD4 B cells transferred into WT recipients exhibited upregulation of CD86 after separate CDG and antigen exposure, and a synergistic increase in CD86 expression was seen after exposure to both antigen and CDG (Fig. 4I-K). Co-transferred STING-deficient MD4 B cells underwent similar responses. When transferred into STING KO mice both MD4 STING sufficient and deficient B cells exhibited significant increases in upregulation of CD86 expression following exposure to antigen. In contrast, exposure of MD4 STING sufficient B cells to CDG did not result in significant upregulation of CD86; however, we did observe super-additive responses to antigen and CDGs by MD4 STING sufficient B cells. Combined with our in vitro observations, these results suggest that cytokines that are produced in vivo upon CDG exposure, likely by other cell types, can activate B cells and act synergistically with antigen stimulation. However, the synergistic responses of STING-sufficient B cells in STING KO recipients suggest that cytokine independent responses to CDG can cooperate with BCR signals to promote B cell activation.

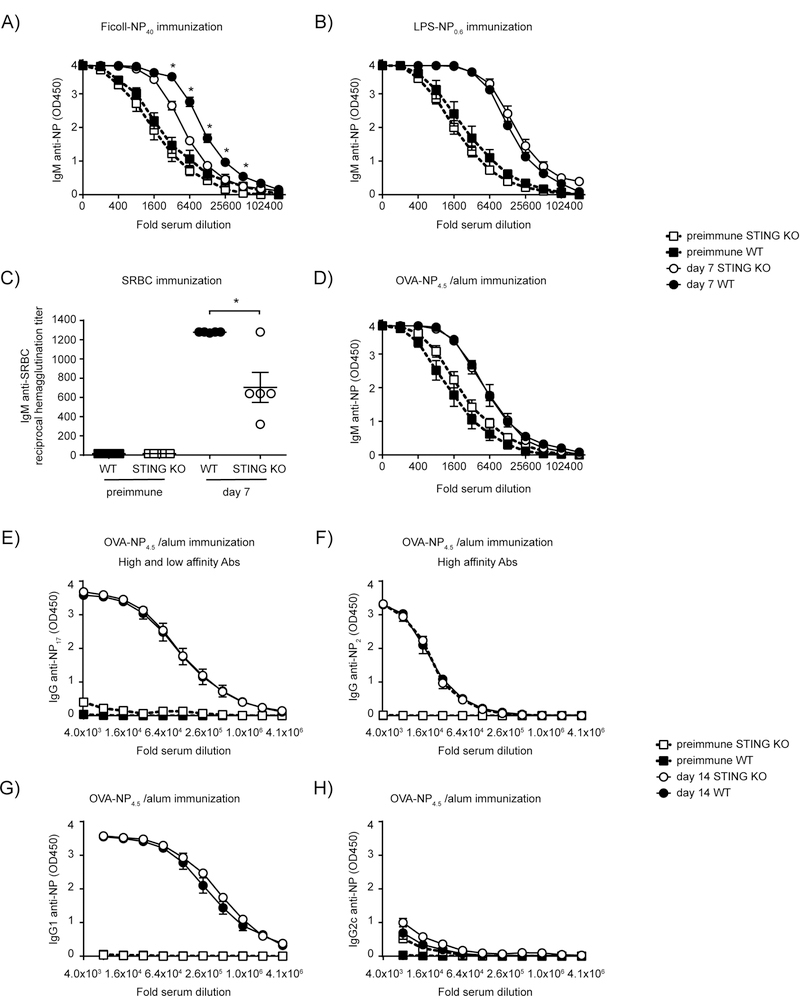

STING deficient mice make reduced antibody responses against type 2 T-independent antigens.

Before testing the requirement of B cell intrinsic STING in the antibody response following CDG immunization we wanted to test the ability of STING deficient mice to mount antibody responses to different antigens. As shown in Fig 5A, significantly reduced antibody responses were observed in STING KO mice after immunization with Ficoll-NP40, whereas responses against a model type 1 T-independent antigen, LPS-NP0.6, were normal (Fig 5B). STING deficient mice also responded equally well to a T dependent antigen, OVA-NP4.5 in alum (Fig D-H). This included processes such as affinity maturation (Fig 5F) and class switching (Fig 5G-H) associated with a germinal center reaction. Interestingly, when we used a different T-dependent antigen, SRBCs, we did observe a statistically significant reduction in the ability of STING KO to mount antibody responses (Fig 5C). This may be due to the repetitive nature of the polysaccharides on SRBC, that may partly act as a type 2 T-independent antigen.

Figure 5: STING is required for optimal Ab response to type 2 TI Ags.

WT and STING KO mice (n=5) were immunized with (A) 25 μg Ficoll-NP40 IP; (B) 5 μg LPS-NP0.6 IP; (C) 5×107 SRBC IP; (D-H) 20 μg OVA-NP4.5 in 200 μg alum IP. D) IgM anti-NP was measured in serum at day 7 post immunization. At day 14 post immunization (E) IgG anti-NP; (F) high affinity IgG anti-NP; (G) IgG1 anti-NP and (H) IgG2c anti-NP was measured. Data shown are representative of at least two independent replicate experiments. Bars in A-H represent mean ± SEM. NS, P>0.05; *, P < 0.05 using an unpaired Student’s t test on individual dilutions. Two-way ANOVA confirmed statistical significance (p<0.005) in (A), whereas (B) and (D)–(H) were statistically not significant (p>0.05).

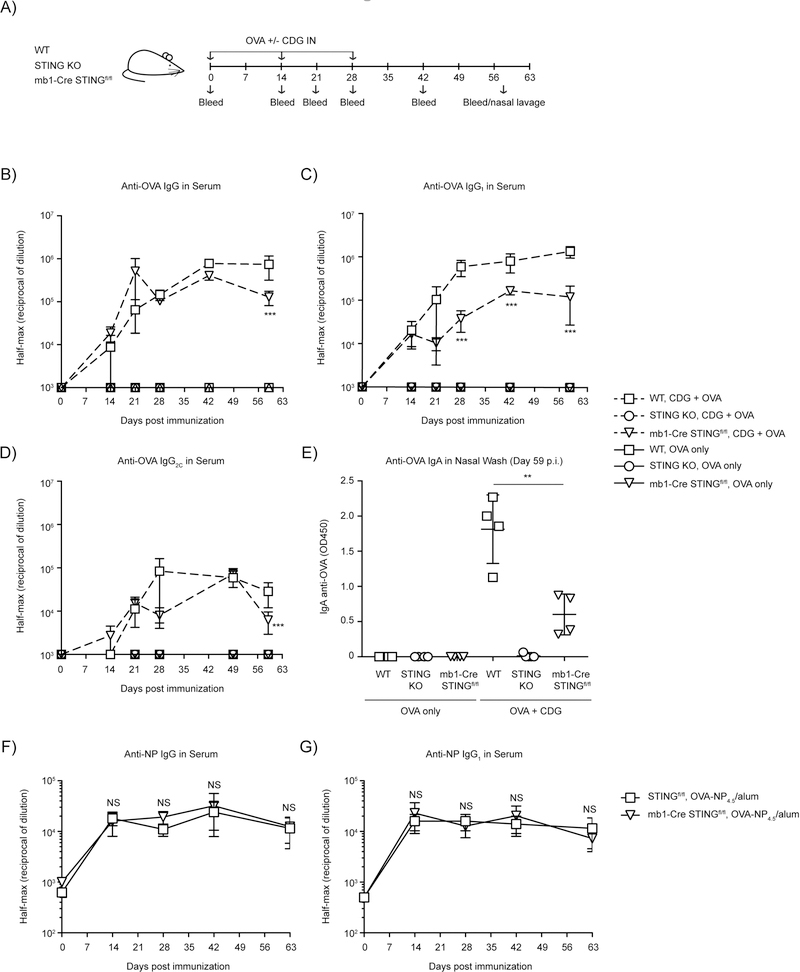

B cell intrinsic STING is required for optimal CDN-enhanced Ag-specific Ab production

Next we tested whether B cell intrinsic STING is required for CDN-enhanced antigen-specific antibody production. We immunized WT, STING KO and B cell-targeted STING KO mice with OVA or OVA plus ci-di-GMP intranasally. Mice were boosted twice, 2-weeks apart after the first immunization, and bled periodically for the duration of the experiment (Fig 6A). WT mice produced robust levels of anti-OVA IgG throughout the duration of the experiment with peak antibody levels seen at day 42 (Fig 6B). As expected, there was no detectable production of anti-OVA IgG antibody by the total STING KO mice at any time point throughout the experiment (Fig. 6B). When we assessed the requirement for B cell expression of STING in CDN-enhancement of antibody production, we found that mice in which B cells lacked STING produced less anti-OVA IgG (Fig 6B). This was reflected in all isotypes but most pronounced in the IgG1 anti-OVA response (Fig. 6C-D). Multiple groups have reported that CDNs promote potent systemic STING-dependent antigen-specific mucosal responses that can result in protective immunity in several infection models (6, 22, 34). To determine the potential role of B cell intrinsic STING expression in CDN-enhanced mucosal response, we assessed differences in OVA-specific IgA antibody titers in the nasal lavage day 59 post immunization between WT, STING KO and the STING B cell targeted KO mice. As expected, we found that mice lacking STING expression in all tissues failed to produce OVA-specific IgA antibodies (12) (Fig. 6E). IgA anti-OVA responses in mice that lacked STING in their B cells was reduced by ~75%. Taken together, these data demonstrate that STING is required in the B cell compartment for optimal CDN-enhanced Ab production. Based on previous experiments this must reflect requirement for a cytokine-independent STING function in B cells.

Figure 6: B cell intrinsic STING is necessary for optimal OVA-specific antibody responses following CDG- enhancement of Ab responses.

A-E) WT, STING KO and mb1-Cre x STINGfl/fl mice were immunized IN with 20 µg OVA with or without 5 µg CDG and serum and mucosal anti-OVA antibody responses were monitored (n=4–5). (A) Schematic representation of the experiment; (B) Reciprocal half-max values of the OVA-specific IgG response; (C) Reciprocal half-max values of OVA-specific IgG1 response; (D) Reciprocal half-max values of OVA-specific IgG2C response; (E) OVA-specific IgA response in nasal wash at day 59. F-G) STINGfl/fl and mb1-Cre x STINGfl/fl mice were immunized IP with 20 µg OVA-NP4.5 in alum (n=5). Serum was collected, and the serum anti-NP responses were monitored (F) Reciprocal half-max values of the NP-specific IgG response; (G) Reciprocal half-max values of OVA-specific IgG1 response. Data shown are representative of at least two independent replicate experiments. Bars in B-G represent mean ± SEM. NS, P > 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 using an unpaired Student’s t test.

STING deficient mice have normal IgG responses following immunization with alum

The reduced IgG1 anti-OVA response observed in B cell-targeted STING KO mice immunized with OVA/CDG from d28 onwards (Fig 6C) suggests that in these mice there is a change in B-T cell interaction. However, since total IgG anti-OVA and all isotypes are significantly reduced at d59 we wanted to exclude the possibility that this may reflect a defected in B cell-targeted STING KO mice in their ability to maintain plasma cell responses. B cell-targeted STING KO mice and control mice were immunized with OVA-NP4.5/alum and total IgG and IgG1 anti-NP responses were assessed throughout the duration of the experiment (up to 63 days post immunization). We found no significant differences in the magnitude of the IgG and IgG1 anti-OVA antibody response (Fig 6F-G). These results suggest that the reduction in antigen-specific antibody responses observed in B cell-targeted STING KO mice is specific to CDG adjuvant activity and not due to a defect inherent in all B cell antibody responses.

DISCUSSION

Though the importance of the STING signaling pathway has been well characterized in immune cell types such as macrophages and dendritic cells (12, 17, 22, 35), there is little known about the role of STING signaling in B cell biology and function. Our results clearly demonstrate that CDNs directly activate B cells, and this response is STING-dependent, causing upregulation of CD86 and cell death (Fig. 1). In addition, this activation was partially the consequence of a positive forward-feeding loop involving production of type I IFN (Fig. 3B), and possibly smaller contribution of other cytokines (Fig. 3D). In our in vitro experiments direct activation by CDNs was responsible for the majority of the observed activation, as evident from experiments using IFNAR KO B cells (Fig. 3B) and co-cultures comparing STING IFNAR DKO B cells with STING KO B cells (Fig. 3A,D). In vivo, under the conditions examined, secondary B cell activation by type I IFN (33) was mainly observed presumably because many tissues were responding to CDNs by IFN production in vivo (Fig. 4A-F). As previously reported the rapid dissipation of CDNs in vivo likely resulted in reduced local exposure of B cells (21). Consistent with this line of reasoning, when we conducted experiments assessing activation of peritoneal B1 and B2 B cells at the site of injection we observed B cell activation dependent on B cell intrinsic STING activity (Fig. 4G). Importantly we observed that even when CDG did not reach levels sufficient in vivo to activate STING-competent B cells there was clear cooperativity between BCR and STING signaling (Fig. 4H-K), suggesting that there are lower CDN threshold requirements for this synergism.

To what degree BCR-STING signal cooperativity contributes to CDG enhancement of antibody responses is unclear. Several groups (12, 21) have demonstrated that type I IFN signaling is dispensable for the adjuvant effect of CDG, suggesting that on the B cell level, CDG acts directly. Recently Blaauboer et al (22) provided compelling evidence that CD11c+ DCs take up and present antigen more efficiently after CDG/antigen immunization and induce more potent T cell responses. Accordingly, targeted deletion of STING in CD11c+ cells resulted in reduced, but not absent, antibody responses after CDG/antigen immunization. B cell-targeted deletion of STING resulted in a significant reduction in antibody responses after CDG/antigen immunization (Fig. 6B-E). This could be due to a loss of the synergistic effects of CDG and Ag on CD86 expression on Ag-specific B cells, that may make cognate B-T cell interaction less efficient.

While STING is important for optimal antibody responses to type 2 TI-antigens (Fig 5A), we found no evidence that the quantity or quality of T cell dependent responses were affected upon loss of STING expression (Fig. 5D-H and Fig 6F-G), suggesting that the observed changes in Ab responses to CDG/Ag immunization of B cell-targeted STING KO mice are specifically due to differences in the response to CDG adjuvant activity. The fact that STING signaling and BCR signaling directly cooperate in B cell signaling (Fig. 2A and C and Suppl Fig 1) could have effects on B cell behavior beyond regulation of CD86 expression. In T cells, STING signaling in conjunction with TCR signaling was recently shown to negatively affect T cell proliferation (26, 36). To what extent STING signaling further alters Ag-driven B cell responses is subject of further investigation. Much like has been described for TLR9 and BCR signaling (37), BCR and STING signaling could cooperate to promote activation of autoreactive B cells and infected B cells (e.g EBV infected B cells).

Another effect of CDN exposure on B cells is STING and Caspase-dependent death (31). We confirmed these findings (Fig 1D) and report for the first time, to our knowledge, that coordinating BCR signals could partial rescue CDG-induced cell death (Fig 2B). While we had a consistent partial rescue in experiments using MD4 B cells (Fig 2B), only in two out of four experiments using WT B cells stimulated with anti-IgM F(Ab)2 and CDG we observed a similar partial protection against CDG-induced death (data not shown). While we are unsure what caused this discrepancy, this potential protective effect could be of importance to consider when treating certain forms of B cell lymphomas with CDNs, as some may still receive BCR signals due to self- antigen interaction (38) or expression of EBV antigens (39). Previous work suggested that activation of the IRE-1/XBP-1 pathway could partially protect against CDN-induced apoptosis (31), although activation of this pathway often does not occur until 24 hrs post BCR stimulation (40), suggesting that alternative pathways may exist. Cell death was mainly mediated by caspase activation, as demonstrated by the ability of z-vad-fmk to largely inhibit CDG-induced cell death (Fig.1E). Unexpectedly, B cell activation was also inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by z-vad-fmk (Fig 1F), while B cell activation by IL-4 was unaffected under these condition (Fig 1G-H), suggesting that caspase activation may be part of STING-mediated cell activation. Caspases have previously been implicated in lymphocyte activation (41).

Herein we describe requirements for B cell intrinsic STING in CDG-enhancement of Ag-specific antibody responses in vivo. Based on the importance of the STING signaling pathway in various immune responses, further evaluation will be important to assess the biological impact of expressing polymorphisms of STING in the human population, as is evident from initial studies (42). In this regard, polymorphisms of STING that confer hypofunctionality might lead individuals to infectious disease susceptibilities and poor Ab responses to CDN-based adjuvanted vaccines and poor anti-tumor immunity, whereas polymorphisms that confer hyperfunctionality might predispose individuals to development of autoimmunity and auto-inflammatory diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Soojin Kim for managing our mouse colony. We thank Vivian Duarte for all her technical help. We thank Dr. Ross Kedl’s laboratory for their generous gift of the endotoxin-low OVA. We thank Dr. Laurel Lenz’s laboratory for giving us an IFNAR KO breeding pair and rIFNß, and Dr David Riches for the TNFAR KO breeding pair. We want to thank the University of Colorado Immunology and Microbiology department flow cytometry core.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R21AI099346, R01DK096492, R01AI24487 and R21AI124488 (JCC). MMW was supported by T32 AI007405 and T32 AI074491

REFERENCES

- 1.Rashid MH, Rajanna C, Ali A, and Karaolis DK. 2003. Identification of genes involved in the switch between the smooth and rugose phenotypes of Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 227: 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romling U, and Amikam D. 2006. Cyclic di-GMP as a second messenger. Curr Opin Microbiol 9: 218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romling U, Gomelsky M, and Galperin MY. 2005. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol Microbiol 57: 629–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Q, Sun L, and Chen ZJ. 2016. Regulation and function of the cGAS-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat Immunol 17: 1142–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen GK, Ebensen T, Gjeraker IH, Svindland S, Bredholt G, Guzman CA, and Cox RJ. 2011. Evaluation of the sublingual route for administration of influenza H5N1 virosomes in combination with the bacterial second messenger c-di-GMP. PLoS One 6: e26973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu DL, Narita K, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Nakane A, and Karaolis DK. 2009. c-di-GMP as a vaccine adjuvant enhances protection against systemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection. Vaccine 27: 4867–4873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karaolis DK, Means TK, Yang D, Takahashi M, Yoshimura T, Muraille E, Philpott D, Schroeder JT, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Talbot BG, Brouillette E, and Malouin F. 2007. Bacterial c-di-GMP is an immunostimulatory molecule. J Immunol 178: 2171–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madhun AS, Haaheim LR, Nostbakken JK, Ebensen T, Chichester J, Yusibov V, Guzman CA, and Cox RJ. 2011. Intranasal c-di-GMP-adjuvanted plant-derived H5 influenza vaccine induces multifunctional Th1 CD4+ cells and strong mucosal and systemic antibody responses in mice. Vaccine 29: 4973–4982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebensen T, Libanova R, Schulze K, Yevsa T, Morr M, and Guzman CA. 2011. Bis-(3’,5’)-cyclic dimeric adenosine monophosphate: strong Th1/Th2/Th17 promoting mucosal adjuvant. Vaccine 29: 5210–5220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray PM, Forrest G, Wisniewski T, Porter G, Freed DC, DeMartino JA, Zaller DM, Guo Z, Leone J, Fu TM, and Vora KA. 2012. Evidence for cyclic diguanylate as a vaccine adjuvant with novel immunostimulatory activities. Cell Immunol 278: 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebensen T, Schulze K, Riese P, Link C, Morr M, and Guzman CA. 2007. The bacterial second messenger cyclic diGMP exhibits potent adjuvant properties. Vaccine 25: 1464–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaauboer SM, Gabrielle VD, and Jin L. 2014. MPYS/STING-mediated TNF-alpha, not type I IFN, is essential for the mucosal adjuvant activity of (3’−5’)-cyclic-di-guanosine-monophosphate in vivo. J Immunol 192: 492–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin L, Waterman PM, Jonscher KR, Short CM, Reisdorph NA, and Cambier JC. 2008. MPYS, a novel membrane tetraspanner, is associated with major histocompatibility complex class II and mediates transduction of apoptotic signals. Mol Cell Biol 28: 5014–5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo-Troha K, Iwig JS, Eckert B, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, and Vance RE. 2011. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature 478: 515–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishikawa H, and Barber GN. 2008. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature 455: 674–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong B, Yang Y, Li S, Wang YY, Li Y, Diao F, Lei C, He X, Zhang L, Tien P, and Shu HB. 2008. The adaptor protein MITA links virus-sensing receptors to IRF3 transcription factor activation. Immunity 29: 538–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin L, Hill KK, Filak H, Mogan J, Knowles H, Zhang B, Perraud AL, Cambier JC, and Lenz LL. 2011. MPYS is required for IFN response factor 3 activation and type I IFN production in the response of cultured phagocytes to bacterial second messengers cyclic-di-AMP and cyclic-di-GMP. J Immunol 187: 2595–2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ablasser A, Goldeck M, Cavlar T, Deimling T, Witte G, Rohl I, Hopfner KP, Ludwig J, and Hornung V. 2013. cGAS produces a 2’−5’-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature 498: 380–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhat N, and Fitzgerald KA. 2014. Recognition of cytosolic DNA by cGAS and other STING-dependent sensors. Eur J Immunol 44: 634–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobbs N, Burnaevskiy N, Chen D, Gonugunta VK, Alto NM, and Yan N. 2015. STING Activation by Translocation from the ER Is Associated with Infection and Autoinflammatory Disease. Cell Host Microbe 18: 157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanson MC, Crespo MP, Abraham W, Moynihan KD, Szeto GL, Chen SH, Melo MB, Mueller S, and Irvine DJ. 2015. Nanoparticulate STING agonists are potent lymph node-targeted vaccine adjuvants. J Clin Invest 125: 2532–2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaauboer SM, Mansouri S, Tucker HR, Wang HL, Gabrielle VD, and Jin L. 2015. The mucosal adjuvant cyclic di-GMP enhances antigen uptake and selectively activates pinocytosis-efficient cells in vivo. Elife 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobeika E, Thiemann S, Storch B, Jumaa H, Nielsen PJ, Pelanda R, and Reth M. 2006. Testing gene function early in the B cell lineage in mb1-cre mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 13789–13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodnow CC, Crosbie J, Adelstein S, Lavoie TB, Smith-Gill SJ, Brink RA, Pritchard-Briscoe H, Wotherspoon JS, Loblay RH, Raphael K, and et al. 1988. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature 334: 676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aida Y, and Pabst MJ. 1990. Removal of endotoxin from protein solutions by phase separation using Triton X-114. J Immunol Methods 132: 191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larkin B, Ilyukha V, Sorokin M, Buzdin A, Vannier E, and Poltorak A. 2017. Cutting Edge: Activation of STING in T Cells Induces Type I IFN Responses and Cell Death. J Immunol 199: 397–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber MM, Lam JL, Dooley CA, Noriea NF, Hansen BT, Hoyt FH, Carmody AB, Sturdevant GL, and Hackstadt T. 2017. Absence of Specific Chlamydia trachomatis Inclusion Membrane Proteins Triggers Premature Inclusion Membrane Lysis and Host Cell Death. Cell Rep 19: 1406–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gadkaree SK, Fu J, Sen R, Korrer MJ, Allen C, and Kim YJ. 2017. Induction of tumor regression by intratumoral STING agonists combined with anti-programmed death-L1 blocking antibody in a preclinical squamous cell carcinoma model. Head Neck 39: 1086–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schock SN, Chandra NV, Sun Y, Irie T, Kitagawa Y, Gotoh B, Coscoy L, and Winoto A. 2017. Induction of necroptotic cell death by viral activation of the RIG-I or STING pathway. Cell Death Differ 24: 615–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaston J, Cheradame L, Yvonnet V, Deas O, Poupon MF, Judde JG, Cairo S, and Goffin V. 2016. Intracellular STING inactivation sensitizes breast cancer cells to genotoxic agents. Oncotarget 7: 77205–77224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang CH, Zundell JA, Ranatunga S, Lin C, Nefedova Y, Del Valle JR, and Hu CC. 2016. Agonist-Mediated Activation of STING Induces Apoptosis in Malignant B Cells. Cancer Res 76: 2137–2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green NM, Laws A, Kiefer K, Busconi L, Kim YM, Brinkmann MM, Trail EH, Yasuda K, Christensen SR, Shlomchik MJ, Vogel S, Connor JH, Ploegh H, Eilat D, Rifkin IR, van Seventer JM, and Marshak-Rothstein A. 2009. Murine B cell response to TLR7 ligands depends on an IFN-beta feedback loop. J Immunol 183: 1569–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braun D, Caramalho I, and Demengeot J. 2002. IFN-alpha/beta enhances BCR-dependent B cell responses. Int Immunol 14: 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin TL, Jee J, Kim E, Steiner HE, Cormet-Boyaka E, and Boyaka PN. 2017. Sublingual targeting of STING with 3’3’-cGAMP promotes systemic and mucosal immunity against anthrax toxins. Vaccine 35: 2511–2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spaulding E, Fooksman D, Moore JM, Saidi A, Feintuch CM, Reizis B, Chorro L, Daily J, and Lauvau G. 2016. STING-Licensed Macrophages Prime Type I IFN Production by Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in the Bone Marrow during Severe Plasmodium yoelii Malaria. PLoS Pathog 12: e1005975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cerboni S, Jeremiah N, Gentili M, Gehrmann U, Conrad C, Stolzenberg MC, Picard C, Neven B, Fischer A, Amigorena S, Rieux-Laucat F, and Manel N. 2017. Intrinsic antiproliferative activity of the innate sensor STING in T lymphocytes. J Exp Med 214: 1769–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leadbetter EA, Rifkin IR, Hohlbaum AM, Beaudette BC, Shlomchik MJ, and Marshak-Rothstein A. 2002. Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature 416: 603–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young RM, Wu T, Schmitz R, Dawood M, Xiao W, Phelan JD, Xu W, Menard L, Meffre E, Chan WC, Jaffe ES, Gascoyne RD, Campo E, Rosenwald A, Ott G, Delabie J, Rimsza LM, and Staudt LM. 2015. Survival of human lymphoma cells requires B-cell receptor engagement by self-antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 13447–13454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mancao C, and Hammerschmidt W. 2007. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A is a B-cell receptor mimic and essential for B-cell survival. Blood 110: 3715–3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu CC, Dougan SK, McGehee AM, Love JC, and Ploegh HL. 2009. XBP-1 regulates signal transduction, transcription factors and bone marrow colonization in B cells. EMBO J 28: 1624–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alam A, Cohen LY, Aouad S, and Sekaly RP. 1999. Early activation of caspases during T lymphocyte stimulation results in selective substrate cleavage in nonapoptotic cells. J Exp Med 190: 1879–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel S, Blaauboer SM, Tucker HR, Mansouri S, Ruiz-Moreno JS, Hamann L, Schumann RR, Opitz B, and Jin L. 2017. The Common R71H-G230A-R293Q Human TMEM173 Is a Null Allele. J Immunol 198: 776–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.