Abstract

Faculty development is essential for renewing and assisting faculty to maintain teaching effectiveness and adapt to innovations in Health Professions educational institutions. The evaluation of faculty development programs appears to be a significant step in maintaining its relevance and efficiency. Yet, little has been published on the specific case of faculty development program evaluation in spite of the availability of general program evaluation models. These models do not measure or capture the information educators want to know about outcomes and impacts of faculty development. We posit that two reasons account for this. The first is the evolving nature of faculty development programs as they adapt to current reforms and innovations. The second involves the limitations imposed by program evaluation models that fail to take into account the multiple and unpredictable outcomes and impacts of faculty development. It is generally accepted that the outcomes and impacts are situated at various levels, ranging from the individual to the institutional and cultural levels. This calls for evaluation models that better capture the complexity of the impacts of faculty development, in particular the reciprocal relationships between program components and outcomes. We suggest conceptual avenues, based on Structuration Theory, that could lead to identifying the multilevel impacts of faculty development.

Keywords: Structuration Theory, complexity theory, identity development, organizational norms, interpersonal relationships, program assessment

Background

There is increasing pressure for the professionalization of teaching practice in medical education.1 It is widely recognized that teaching is a skilled profession that calls for multifaceted faculty development (FD) programs.2–6 As Steinert and Mann defined it, FD encompasses a broad range of topics and learning activities aimed to support faculty members in the enactment of multiple academic roles.3 Indeed, many FD programs offer training, not only to foster teaching and supervising skill development, but also to meet new requirements affecting medical practice and clinical roles.

The implementation of competency-based medical education (CBME) has recently contributed further to rethinking FD programs to prepare teachers to play new roles and teach multiple competencies.7–11 Given the complex nature of competencies12 and the introduction of multiple competencies such as the CanMEDs in Canada10 or the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education–Milestones13 in the United States, descriptions of teacher roles have become more diversified, as described by Harden & Crosby’s 12 roles.7

In this context, recommendations and principles of good practice for FD that have emerged highlight the need for a broader and more lasting impact for FD programs.3,5,14 This implies that FD programs need to be longitudinal in nature and expose participants to a broader range of teaching methodologies and be subject to continuous quality improvement.15 In this sense, FD has become part of continuous professional development for clinical teachers.16 Many faculties of medicine, in accordance to the guidelines of good practice, have implemented FD programs.14,17,18

However, in spite of investing considerable resources, little is known about FDs effective impact on clinical teaching in particular and on broader change in the learning environment in general. Further, Haji et al19 found that when program evaluation is carried out, few of the expected outcomes are easily identified. Indeed, training program development teams focus mostly on curriculum and implementation and often neglect evaluation.20 It is furthermore hard to explain the lack of program evaluation on the absence of models and frameworks to carry them out, especially in the educational domain.21 Frye et al22 define program evaluation as the

“systematic collection and analysis of information related to the design, implementation, and outcomes of a program for the purpose of monitoring and improving the quality and effectiveness of the program”.

A recent study identified five key papers about program evaluation that capture the attention of health sciences educators as revealed on a social media poll.23 The papers focus on the methodology of evaluation, the context of evaluation practice and the challenge of modifying existing programs on the basis of evaluation results.24–26 They highlight the importance of gaining a holistic view of a program to better clarify the relationship between interventions and multiple outcomes as well as broader impacts.19,22

Leslie, Baker, Evan-Lee, Esdaile & Reeves27 recently provided a detailed account of the nature and scope of FD programs in medical education and aimed to assess their quality. Their review of FD programs reveals that self-reported changes in behavior is the most commonly reported outcome as well as an overreliance on quantitative surveys to collect data. The authors suggest that more rigorous evaluation methods should be used and that practice in the workplace as well as the effects of multiple organizational and contextual factors that shape the success of FD programs should be considered as well. In summary, the literature suggests that only evaluating expected outcomes of a training program is not enough, broader impacts need to be taken into account.

It is clear that evaluation of educational programs requires a very different skillset than that normally possessed by teachers.25 It requires a considered look at multiple variables that may have an impact on the outcomes of a given educational program. Swanwick28 described FD as

“an institution-wide pursuit with the intent of professionalizing the educational activities of teachers, enhancing educational infrastructure, and building educational capacity for the future.” (p. 339)

It follows that the evaluation of FD impacts requires some thoughtful attention.

In this perspective paper, we aim to provide an overview of the existing models of educational program evaluation in order to suggest a conceptual framework for the specific case of evaluating FD programs. This framework was developed through an iterative process between the authors29 in which we discussed and contrasted evaluation frameworks that have been proposed in medical education (eg,16,2,19,20,22,25,30,31) and in education (eg,32–34). By doing so, we sought to identify potential avenues for evaluating the impact of faculty development programs.

Theoretical underpinnings

Theories of evaluation rest on the measures that are selected and the strategies applied to carry out program evaluation. Frye et al22 present an overview of the theories that underpin program evaluation models, suggesting three approaches: linear, systemic and complex.

The linear approach

The linear approach implies that the outcome of a training program can be predicted by observing the cumulative contributions of its constituent parts. This approach rests on the assumption of linearity and unidirectionality in the relationships between program components. That is, changes in one program component are expected to have a predictable impact on another component. Some program evaluation models such as the decision-based evaluation model developed by Kraiger,34 clearly assume linearity. The model is composed of three components arranged in a linear relationship: 1) content and design of training, 2) changes within the learner and 3) organizational payoffs. The same can be said of the Kirkpatrick model,35 where satisfaction, learning outcomes and behavior are assumed to be linked. Indeed, much of the criticism leveled against current evaluation frameworks in medical education points to their focus on observable outcomes, with little or no consideration of hard to observe individual’s perceptions and motivations and of the environment where new learning will be used.

The systems theory approach

This approach posits that a system is composed of various parts, the coordination of those parts and the relationships among the parts. The system is also embedded within an environment that has different impacts on its various parts and all relationships are not static but constantly changing. Hence, an educational program is a social system composed of various parts that interact with each other and with the environment in which it is embedded. For example, the Context, Input, Process and Product evaluation model takes into account the multiple relationships among system components.21,33

Context, in this model, plays a critical role in shaping the approach to evaluating program effectiveness due to its influence on program processes seen as separate and given equal importance.36 Parker and colleagues30 developed an evaluation logic model that sought to determine whether the training program affects learners in anticipated and unanticipated ways and how these results might help improve the original program. The model maps the program components, including inputs, outputs and anticipated outcomes, in order to define the type of data - both qualitative and quantitative - needed to measure processes and outcomes. This approach takes into account multiple variables that will have an effect on outcome and a wider impact on the field of activity. The issue addressed by these authors is to provide a broader framework than simply identifying what needs to be measured.

Hence, system theory embraces the idea that change is an inherent part of a system and is seen as a positive development in evaluation theory since it focuses on individuals’ interactions with internal and external factors. However, it is still very much based on linearity and has little affordance for recursive or reciprocal interactions between variables.

The complexity theory approach

Medical education programs are best characterized as complex systems; given that they are made up of diverse components that interact reciprocally among each other. Because of this, examining each of the interactions between components in isolation fails to take into account the overall impact of all relationships, and thus the system as a whole.37

Complexity theory allows for the uncertainty of educational program outcomes and would thus be appropriate to evaluate its intended and unintended impacts by providing useful data that serves program needs more effectively. In other words, examining a program’s success through complexity theory leads educators to consider the interaction of its components (eg, course design, participants, instructors, etc.) with outcomes but also among each other as well as with the environment. This, argues complexity theory, leads to a greater appraisal of program’s impact.

Haji, Morin & Parker19 present essential elements of educational programs that should be taken into account in an effort to develop a holistic program evaluation aimed to identify if the predicted changes occurred and whether unpredicted changes took place.

Durning, Hemmer & Pangaro20 advocate for a three-phase framework for program evaluation. This framework allows for establishing relationships among baseline, process and product measurements - Before, During and After - aimed at collecting data, both quantitative and qualitative from multiple stakeholders, that describe program “success.” In this case, program “success” is demonstrated when measurements relate “inputs” to “outputs” and can be used to understand the causes and shed some light into how the program worked. Baseline measurements collect information about trainees before entry into the program. Process measurements capture the activities of learners and faculty as well as how the program unfolded. Outcome measures capture the differences observed from baseline measures.

The above models capture complexity by multiplying measurements, by mapping a logic model to identify relevant data sources and by making affordances for unexpected outcomes. However, they do not provide viable means to capture broader impacts that a training program might generate in the workplace, on educational infrastructures and teaching culture. Yet, in the tradition of “realist evaluation,”32 program evaluation should work to test hypotheses about how, and for whom, programs are predicted to “work”. This means collecting data, not just about program impacts, or the processes of program implementation, but about the specific contextual and cultural contexts that might impact program outcomes, and about the specific mechanisms that might be creating change. We turn our attention in the following section on the complex nature of FD as has evolved and how it fosters change not only on teaching practice but on organizational development.

The evolution of faculty development in medical education

In this section, we discuss characteristics of faculty development in medical education that promote change in order to argue for a broader approach to program evaluation. According to Fullan,38 any FD program should endeavor to initiate and sustain change within the institution. It follows that effective program evaluation should focus on change: Is change occurring? What is the nature of the change? Is the change deemed “‘successful’”? Kumar and Greenhill39 identified the factors within an academic health care institution that shape how clinical teachers use educational knowledge acquired through FD. They draw attention to a combination of contextual, personal and interactional factors.

Yelon, Ford et al31 suggest that enactment of change hinges on three factors: First, the ability to enact change must be fostered by the FD program itself by providing adequate cognitive support for competency development.40,41 Second, FD participants have to be willing to apply their new learning in their workplace as Kogan42 suggests: change can be successful only when individuals commit to enact change in their own practice and to sharing their insights with colleagues. This depends on how they view the relevance and benefit of what they have learned.43,44 Third, workplace environments have to facilitate the application of the new learning by recognizing and overtly supporting the changes enacted by individuals.45,46

All these factors include an individual dimension as well as a systems dimension;42 hence, in order to construct our argument about the complex nature of FD, we describe factors for change at an individual level followed by factors at a systems level.

Faculty development as a factor for change at an individual level

An important factor at play with regards to FD generated change at an individual level is related to identity development. Clinical teachers have a dual identity: to provide patient care and to teach.47–50

Attaining an appropriate balance between these asymmetrical identities is a challenge: physicians’ comfort zone and greater medical expertise tilt the balance heavily in favor of the clinician. However, because FD aims to professionalize teaching practice rather than rely, as it often occurs, on intuition and past experience as learners,6,51,52 it necessarily entails a process of identity development.53

Cruess, Cruess, Boudreau & Steinert name the process whereby a person learns to function within a particular society or group by internalizing its values and norms, as “socialization.”54 This process is the driving force underwriting professional identity development in clinical teachers. Through complex networks of interactions, exposure to confirmatory role models and mentors, through experiential learning and explicit and tacit knowledge acquisition, medical students gradually start behaving like physicians.

Jarvis-Selinger, Pratt & Regehr describe the process of identity formation as

“an adaptive developmental process that happens simultaneously at two levels:55 (1) at the level of the individual, which involves the psychological development of the person and (2) at the collective level, which involves the socialization of the person into appropriate roles and forms of participation in the community’s work.”

It is important to distinguish socialization from training. Hafferty describes them as parallel processes; training involves the acquisition of knowledge and skills whereas socialization is seen as the effects of these acquisitions on the sense of self.56

Furthermore, as recently indicated by Cruess, Cruess, Boudreau & Steinert54 professional identity is in constant evolution, and given the current pressures on health care delivery systems, it is undergoing important transformations.57 Hence, the literature clearly emphasizes that professional identity development occurs at multiple levels, from the individual and their personality, to the relationships with peers and others in their workplace and the broader context of the workplace.58–60

In addition to providing supervision, clinical teachers are required to model respectful, empathic and professional interactions with patients, their families and other professionals.41 This tends to take place in fast-paced and unpredictable settings, which continually challenge health care team members to choose between competing demands.61

Furthermore, clinical teachers often have little awareness of their specific training needs with regards to teaching, so that FD may be seen as an extra irritant. Given the above, there is little doubt that teaching in a clinical setting can be a demanding, complex and potentially frustrating task.61

This reality places clear limits for clinical teachers in terms of availability to participate in FD.26 Settings where clinical teaching occurs are facing the need to adapt themselves to this reality, which leads to innovative ways to carry out FD. We have seen that a strategy whereby clinical teachers are trained in their workplace and offered peer support has yielded encouraging results.62,63 In the co-teaching model,64 paired physicians focus on developing their teaching skills while sharing the clinical supervision of trainees. Through teaching, debriefing and planning, co-teachers gain experience in analyzing teaching encounters and develop skills in self-evaluation. At the core of these approaches is the sharing of insights and co-development of teaching practice which occurs at a system level.

Given these developments, it is not surprising that FD itself is called upon to evolve. New strategies and methods are being implemented, and the content material is expanding continuously encompassing such topics as leadership and organizational change as well as specific competencies.15,65

Faculty development as a factor for change at a systems level

Because clinical teachers usually teach in multiple settings, be they inpatient, outpatient and community clinics, each with their own distinct culture and traditions,48,61 transfer of new learning from FD programs depends on multiple factors that extend beyond an individual’s newly acquired skills.

The behaviors and practices within social entities such as clinics and hospitals are often grounded in traditions that form, what Bourdieu66 describes as doxa (ie, implicit, unchallenged assumptions). This in turn produces habitas – the habitual, patterned and thus pre-reflexive way of understanding and behaving that helps generate and regulate the practices that make up the social fabric of a faculty of medicine and its teaching hospitals.67 The introduction of patient partnerships for health care delivery improvement68–70 and interprofessional collaboration71–74 are examples of changes that challenge the long-held habitas in medical training institutions.

Although FD activities tend to focus predominantly on teaching and instructional effectiveness, the systems level perspective points to a critical need to expand FD curricula in order to reinforce teachers’ capacity to become organizational change agents.75 This implies that clinical teachers are expected to play increasingly complex roles that go beyond simply doing rounds with students. They also imply that clinical teachers are often called upon to model what they are themselves learning.1,7,76–78

From the above points, it becomes clear that as medical education evolves, so too does FD. Its impacts must be recognized and evaluated at multiple levels; on organizations, on professional identity development, on workplace norms and culture, on clinical teaching roles. These characteristics make FD a special case within the domain of program evaluation rendering traditional methods of evaluating a training program insufficient to capture the complexity of its impacts.

In essence, the approach to program evaluation should take into account what is known about faculty’s perspectives on education, competency development, theoretical knowledge about learning, as well as their personal characteristics, including teacher identity. The approach should also take into account multiple contextual factors such as time allotment and protection for teaching, academic promotion rules that favor or hinder importance of teaching and the actual setting where the teaching is to take place including logistical issues. Finally, bodies that regulate practice for all health professions also have an impact on teaching practices and consequently on FD.

Discussion

Cognizant of Steinert’s work on FD as a longitudinal endeavor that enacts cultural change, it became clear to us that the linear and systemic approach, as discussed earlier, insufficiently captures the complexity of the outcomes and impact of FD. Furthermore, FD programs occur within organizations in which individuals work together for varying periods of time, share responsibilities for the common goal of educating clinicians and work under common and evolving norms and practices. Impacts are therefore recursive and are not bound to the logic of linearity.

We felt it appropriate to seek a more adaptive conceptual framework, and our aim here is to present its possible components. We turned to complexity theory to undertake the shift from focusing on the individual parts of a system and their linear relationships with the outcomes and impacts.37

Complexity theory points to the multiple and reciprocal relationships between the parts and the outcomes, which implies that not only that the whole is more than the sum of its parts, but that the parts mutually impact each other as well as the outcomes. This appears suitable for faculty development programs where academic directors, teachers, students and patients will mutually influence each other generating multiple changes which will, ultimately, shape the organizational culture within the institution.

In order to appropriately capture the psychological and social impacts of FD, Giddens’ Structuration Theory, a sociological application of complexity theory, allowed us to identify domains that adequately capture change.79 Structuration Theory posits that actions undertaken by individuals within a community or organization contribute to the creation of social structures, norms, hierarchies, values, beliefs, etc., that in turn frame the way individuals act and relate to each other. Hence, Structuration Theory helps to situate faculty development within a dynamic process - structuration - that evolves in time.

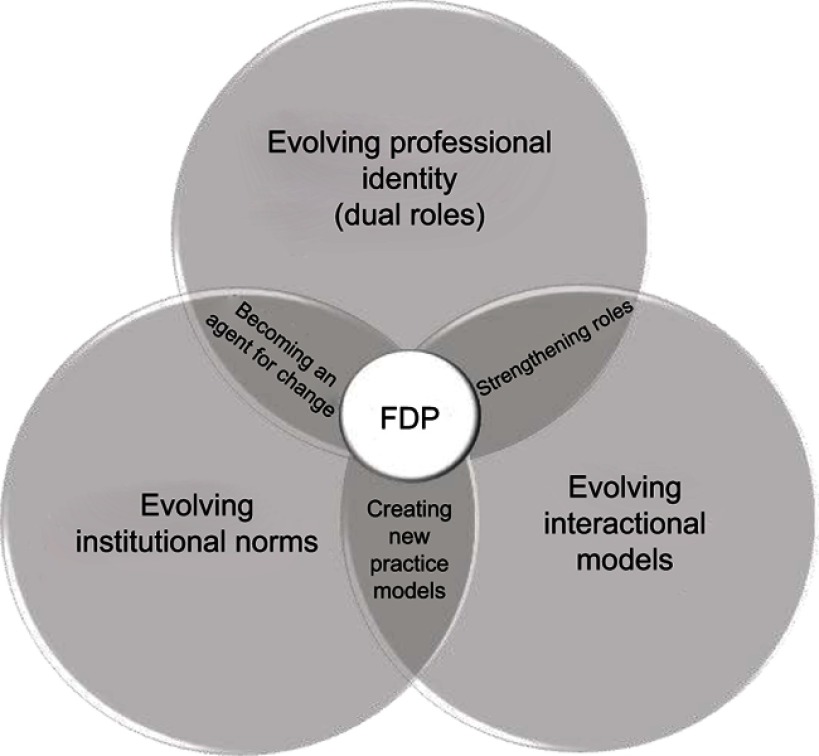

We suggest that application of Structuration Theory to FD program evaluation rests on three processes: 1) the process of professional teacher identity development, 2) the process of how individuals shape organizational structures and 3) the interactions between the individuals themselves. As seen in Figure 1, FD programs can easily be situated at the junction of these three structuration processes.

Figure 1.

Faculty development program (FDP) evaluation: complexity of the outcomes and impacts.

Focusing FD program evaluation on the reciprocal impacts of the three processes – identity, norms and interactions – portrayed by the overlapping areas in Figure 1, offers comprehensive and dynamic insights into the evolution of teaching practices. These overlapping areas are strengthening of roles, creating new practice models and becoming agents for change.

Evaluate how FD impacts professional roles

As discussed earlier, clinical teachers are required to play multiple roles and thus a key objective of FD is training towards these roles. A case in point are the roles in collaborative practice to which clinical teachers must be trained.

In a recent study on professional identity and collaborative practice conducted by Joynes,80 FD emerges as an effective means to enhance interprofessional collaboration. Addressing the tension between students’ developing professional identities and the need to learn collaborative practice could be part of the FD curriculum. Most FD curricula include topics on collaboration (ie, how to make decisions in a simulated team, etc.) and how to supervise collaborative practice.

Many programs also include training activities where health professionals from multiple disciplines learn together. The underlying principle is that training together leads to better understanding of respective roles and supports successful enactment of these roles in collaborative practice. Thus, by strengthening each professional role and supporting collaborative practice, FD has a far-reaching and highly complex impact on how health professionals interact among each other while playing their roles.

It appears therefore crucial to capture the degree to which FD outcomes and impacts support multiple roles among health professionals. These impacts, as presented in Figure 1, are at the confluence of the evolution of professional identity and the evolution of interactional models.

Evaluate how FD generates new practice models

Physicians who are teachers work in academic health care institutions which are endowed with well-defined norms, regulations, codes of conduct, etc. Structuration Theory conceives of these norms as being part of a reciprocal relationship between individuals who work collectively and abide by them and their institution. It follows that interactional models, reflecting how individuals relate to each other, contribute to shaping the institutional norms and practices. We posit that the combined impacts are best observed by evaluating the new practice models that emerge at the confluence of the two processes.

The implementation of CBME serves as an illustration in that it challenges accepted norms and practices, sometimes contradicting long-held values in medical education, as well as impacting interactional models between peers and students.12 For example, CBME FD programs introduce novel evaluation tools such as Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs).81 These are collectively agreed evaluation tools that allow instructors to judge whether a professional activity can be “entrusted” to a trainee. Because EPAs are agreed by faculty members, it calls upon meaningful interactions among them. The fact that students have prior access to the EPAs and thus know what is expected of them will also shape their interactions with instructors. Hence, as CBME challenges the institutional norms, the interactional models between students and instructors are called upon to generate new practice models. In our view, FD program evaluation needs to capture this evolution faithfully.

Evaluate how FD participants become agents for change

Professional identity shapes the way individuals interact, share knowledge and create new knowledge and hence has impacts on the culture of a teaching institution as well as its norms. This reciprocal relationship has complex ramifications that are hard to capture.

Yet, if we consider that FD fosters development of multiple professional identities that will be adapting to changing institutional norms and culture, their mutual impact cannot be ignored. Learning is mediated by interpersonal interactions, focusing on the critical nature of mentor–mentee relationships for conveying commonly held knowledge, as well as reinforcing and transmitting the cultural norms of a given community. In the case of medical education, the dual role of clinical teachers – clinicians and teachers – subjected to competing demands from the institution adds a further level of complexity.

Changes in an individual’s teaching practice reflect evolution in their professional identity, which in turn leads to challenges to institutional norms and teaching culture with the corollary impacts on the workplace. Steinert75 commenting on the future of FD calls for medical educators to demonstrate leadership and management skills, required to become agents for change. These are the individuals who actively seek to introduce innovations in the way work is carried out by asking typical questions such as these: What is the value that the organization assigns to teaching activities? What are the competencies that the organization values? What are the unsaid norms and regulations in a given setting that shape teaching practice? In our view, a sound program evaluation approach should encompass how agents for change shape teaching culture within the teaching hospital and the medical school and how they challenge institutional norms.

Conclusion

Given the complexity of medical education, we have presented a case to develop new approaches and methodologies to evaluate FD programs with the view to yielding more relevant information.

We consider this a critical evolution because of the rapid nature of change within medical education, health care delivery and clinical practice. As new norms and practices evolve, FD program designers will need to leverage reliable information about the impacts of their work to enhance FD programs.

Our aim was to argue that FD programs have multiple outcomes and impacts that are multiplicative and reciprocal. In future work, through experimentation with these concepts in real settings, practical methodologies and tools can be designed that can ultimately benefit FD developers and educators. Possible aspects that could be considered as FD impacts are evolving teaching and learning styles, students and resident well-being, patient outcomes, workplace satisfaction, etc.

We sought to help medical educators answer the following question: What are the impacts of FD interventions not only on the knowledge, attitudes and skills of clinical teachers, but also on their dual professional identity development, on their interactions with other professionals, students and patients and, finally, on the institutions in which they work collectively? According to Steinert,75 FD can play a critical role in promoting cultural change at a number of levels that, as we have seen, reciprocally impact each other. We suggest that FD program evaluation focuses on how professional roles evolve, on how new practice models emerge and on how agents for change challenge accepted norms and practices.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Hesketh E, Bagnall G, Buckley E, et al. A framework for developing excellence as a clinical educator. Med Educ. 2001;35(6):555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bligh J, Prideaux D, Parsell G. PRISMS: new educational strategies for medical education. Medical Education, 35 (6):520-521. Med Educ. 2001;35(6):520–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinert Y, Mann K. Faculty development: principles and practice. J Vet Med Educ. 2006;33:317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramani S. Twelve tips for excellent physical examination teaching. Med Teach. 2008;30(9):851–856. doi: 10.1080/01421590802206747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLean M, Cilliers F, van Wyk J. Faculty Development: Yesterday,Today and Tomorrow, AMEE GUIDE in Medical Education No 33. Dundee: Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE); 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irby DM. Excellence in clinical teaching: knowledge transformation and development required. Med Educ. 2014;48:776–784. doi: 10.1111/medu.2014.48.issue-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harden R, Crosby J. The good teacher is more than a lecturer: the twelve roles of the teacher; AMEE Guide N0 20. Med Teach. 2000;22(4):334–347. doi: 10.1080/014215900409429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, Ferentz K, Martin C. Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to competencies. Acad Med. 2002;77(5):361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boucher A, Ste-Marie LG. Towards A Competency-Based Medical Education Curriculum : A Training Framework. Montréal: Les Presses du CPASS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank J, Sherbino J, Snell L. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh A, Antao V, Bethune C, et al. Activités pédagogiques fondamentales en médecine familiale: Un référentiel pour le développement professoral. Mississauga (ON): Le Collège des médecins de famille du Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez N, Dory V, Ste-Marie L, Chaput M, Charlin B, Boucher A. Varying conceptions of competence: an analysis of how health sciences educators define competence. Med Educ. 2012;46:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04183.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmboe ES, Edgar L, Hamstra S The Milestones Guidebook, Graduate-medical-education/milestonesguidebook2016. Downloaded November 23rd, 2017: http://www.umm.edu/~/media/umm/pdfs/for-healthprofessionals/2016.

- 14.Steinert Y. Faculty development in the new millenium: key challenges and future directions. Med Teach. 2000;22(1):44–50. doi: 10.1080/01421590078814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinert Y. Faculty development: on becoming a medical educator. Med Teach. 2012;34(1):74–76. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.596588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight AMA, Carrese JAJ, Wright SMS. Qualitative assessment of the long-term impact of a faculty development programme in teaching skills. Med Educ. 2007;41(6):592–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02770.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkerson L, Irby D. Strategies for improving teaching practices: a comprehensive approach to faculty development. Acad Med. 1998;73:387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinert Y. Faculty development: from workshops to communities of practice. Med Teach. 2010;32:425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haji F, Morin M, Parker K. Rethinking programme evaluation in health professions education: beyond ‘did it work?’. Med Educ. 2013;47:342–351. doi: 10.1111/medu.2013.47.issue-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durning S, Hemmer P, Pangaro N. The structure of program evaluation: an approach for evaluating a course, clerkship, or components of residency or fellowship training program. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):308–318. doi: 10.1080/10401330701366796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stufflebeam DL. Evaluation models. New Direct Eval. 2001;89:7–98. doi: 10.1002/ev.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frye A, Hemmer P. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE Guide No. 67. Med Teach. 2012;34(5):e288–e299. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.668637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thoma B, Gottlieb M, Boysen-Osborn M, et al. Curated collections for educators: five key papers about program evaluation. Cureus. 2017;9(5):e1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldie J. Evaluating educational programmes, AMEE Education Guide no. 29. Med Teach. 2006;28(3):210–224. doi: 10.1080/01421590500271282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook DA. Twelve tips for evaluating educational programs. Med Teach. 2010;32(4):296–301. doi: 10.3109/01421590903480121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook DA, Steinert Y. Online learning for faculty development: a review of the literature. Med Teach. 2013;35::930–937. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.827328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leslie K, Baker L, Egan-Lee E, Esdaile M, Reeves S. Advancing faculty development in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(7):1038–1045. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318294fd29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swanwick T. See one, do one, then what? Faculty development in postgraduate medical education. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:339–343. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.068288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kemmis S, McTaggart R. Participatory Action Research: Communicative Action and the Public Sphere. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2005:559-603. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker K, Burrows G, Nash H, Rosenblum ND. Going beyond Kirkpatrick in evaluating a clinician scientist program: it’s not “if it works” but “how it works. Acad Med. 2011;86:1389–1396. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823053f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yelon SL, Ford JK, Anderson WA. Twelve tips for increasing transfer of training from faculty development programs. Med Teach. 2014;36(11):945–950. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.929098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stufflebeam DL. The CIPP Model for Program Evaluation In: Madaus FF, Scriven M, Stufflebeam DL, editors. Evaluation Models: Viewpoints on Educational and Human Services Evaluation. Kluwer: Norwell; 1983:117–141. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraiger K. Decision-Based Evaluation. Creating, Implementing and Managing Effective Training and Development. State-Of-The-Art Lessons for Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirkpatrick D. Evaluating Training Programs : The Four Levels. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stufflebeam D, Shinkfield A. Evaluation Theory, Models, & Applications. San Francisco: Jossey Bass/John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sturmberg JP, Martin CM, editors. Complexity in health: an introduction. In: Handbook of Systems and Complexity in Health. New York, NY, USA: Springer Science+Business Media; 2013:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fullan M. The New Meaning of Educational Change. 3rd ed. New York: Teachers College; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar K, Greenhill J. Factors shaping how clinical educators use their educational knowledge and skills in the clinical workplace: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(68):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0506-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown J, Collins A, Duguid P. Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ Res. 1989;18:32–42. doi: 10.3102/0013189X018001032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stalmeijer R, Dolmans DHJM, Ham S-B, Van Santen-Hoeuff M, Wolfhagen IHAP, Scherpbier AJJA. Clinical teaching based on principles of cognitive apprenticeship: views of experienced clinical teachers. Acad Med. 2013;88:1–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828fff12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kogan JR, Conforti LN, Yamazaki K, Lobst W, Holmboe ES. Commitment to change and challenges to implementing changes after workplace based assessment rater training. Acad Med. 2017;92:394–402. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ingham G, Fry J, O’Meara P, Tourle V. Why and how do general practitioners teach? An exploration of the motivations and experiences of rural Australian general practitioner supervisors. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(190):EarlyOnline. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0474-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dotters-Katz S, Hargette CW, Zaas AK, Cricione-Schreiber LG. What motivates residents to teach? The Attitudes in Clinical Teaching study. Med Educ. 2016;50:768–777. doi: 10.1111/medu.13075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slade B. Professional learning in rural practice: a sociomaterial analysis. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2013;25(2):114–124. doi: 10.1108/13665621311299799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raemdonck I, Gijbels D, van Groen W. The influence of job characteristics and selfdirected learning orientation on workplace learning. International Journal of Training and Development. 2014;18(3):188–203. doi: 10.1111/ijtd.2014.18.issue-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prideaux D, Alexander H, Bower A, et al. Clinical teaching: maintaining an educational role for doctors in the new health care environment. Med Educ. 2000;34:820–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Irby D, Bowen J. Time-efficient strategies for learning and performance. Clin Teach. 2004;1:23–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2004.00013.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Audétat MC, Laurin S. Clinicien et superviseur, même combat !. Le Médecin du Québec. 2010;45(5):53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 50.M-C A, Grégoire G, Fernandez N, Laurin S. From intuition to professionalization: a qualitative study about the development of teacher identity in internal medicine senior residents. Int J Health Educ. 2017;1(1):5–12. doi: 10.17267/2594-7907ijhe.v1i1.1234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497–526. doi: 10.1080/01421590601102956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Audétat MC, Faguy A, Jacques A, Blais J, Charlin B. Étude exploratoire des perceptions et pratiques de médecins cliniciens enseignants engagés dans une démarche de diagnostic et de remédiation des lacunes du raisonnement clinique. Pédagogie Médicale. 2011;12(1):7–16. doi: 10.1051/pmed/2011014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Higgs J, Mc Allister L. Being a Clinical Educator. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2006;12:187. doi: 10.1007/s10459-005-5491-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Steinert Y. Reframing Medical Education to Support Professional Identity Formation. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1446–1451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt D, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87:1185–1190. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hafferty F. Professionalism and the socialization of medical students In: Cruess RL, Steinert Y, editors. Teaching Medical Professionalism. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Starr S, Ferguson WJ, Haley HL, Quirk M. Community preceptors’ views of their identities as teachers. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):820–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Starr S, Haley HL, Mazor K, Ferguson W, Philbin M, Quirk M. Initial testing of an instrument to measure teacher identity in physicians. Teaching and Learning in Medicine 2006. 2006;18(2):117–125. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1802_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care?. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):40–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramani S, Leinster S. Teaching in the clinical environment: AMEE Guide No 34. Med Teach. 2008;30:347–364. doi: 10.1080/01421590802061613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lachman N, Christensen KN, Pawlina W. Anatomy teaching assistants: facilitating teaching skills for medical students through apprenticeship and mentoring. Med Teach. 2013;35(1):e919. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.714880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bing-You RG, Blondeau W, Dreher GK, Irby DM. T2 (teaching & thinking)-in-action skills of highly rated medical teachers: how do we help faculty attain that expertise?. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. 2015;52:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Orlander JD, Gupta M, Fincke BG, Manning ME, Hershman W. Co-teaching: a faculty development strategy. Med Educ. 2000;34:257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verma S, Flynn L, Faculty’s SR. Residents’ Perceptions of teaching and evaluating the role of health advocate: a study at one Canadian university. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bourdieu P. The Logic of Practice. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldie J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: considerations for educators. Med Teach. 2012;34(9):e641-e648. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baker GR. Evidence Boost: A Review of Research Highlighting How Patient Engagement Contributes to Improved Care. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karazivan P, Dumez V, Flora L, et al. The patient-as-partner approach in health care: a conceptual framework for a necessary transition. Acad Med. 2015;90:4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pomey M-P, Ghadiri DP, Karazivan P, Fernandez N, Clavel N. Patients as partners: a qualitative study of patients’ engagement in their health care. PLOSone. 2015;10(4):e01–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abu-Rish E, Kim S, Choe L, et al. Current trends in interprofessional education of health sciences students: a literature review. J Interprof Care. 2012;26(6):444–451. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2012.715604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thistlethwaite J. Interprofessional education: a review of context, learning and the research agenda. Med Educ. 2012;46(1):58–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04143.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hugh Barr H. Enigma variations: Unraveling interprofessional education in time and place. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(Supl2): 9-13. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.766157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reeves S, Hean S. Why we need theory to help us better understand the nature of interprofessional education, practice and care. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(1):1–3. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.751293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Steinert Y. Commentary: faculty development: the road less traveled. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):409–411. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820c6fd3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Skeff K, Stratos G, Mygdal W, et al. Clinical teaching improvement: past and future for faculty Development. Fam Med. 1997;29:252–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, Schiffer R. What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine? A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):452–466. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bee61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Srinivasan M, Le S, Meyers FJ, et al. Teaching as a Competency”: competencies for Medical Educators. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1211–1220. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Giddens A. The Constitution of Society. Oakland, CA: University of California Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Joynes VCT. Defining and understanding the relationship between professional identity and interprofessional responsibility: implications for educating health and social care students. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2017;23:133–149. doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9778-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schultz K, Griffiths J, Lacasse M. The application of entrustable professional activities to inform competency decisions in a family medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):888–897. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]