Abstract

Introduction: The classical type of well-differentiated thyroid cancer (WDTC) is the most common endocrine tumor with generally excellent prognosis. WDTC of the WHO stage 1 classification metastasizing to the vertebral column is not often seen for this neoplasm. Here, I present a case series of 14 individuals with aggressive classical type of WDTC.

Methods: To identify the most aggressive cases of classical type WDTC, I reviewed the medical records of 4,327 patients consecutively admitted and surgically treated in a single institution for thyroid pathology in the years 2008–2016. Demographic, pathological and outcome data were collected and reviewed.

Results: During the study period, 14 (4.02%) patients with aggressive forms of the classical type of WDTC were reviewed: 10 (2.87%) cases with papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) and 4 (1.14%) with follicular thyroid cancer (FTC). The median age at diagnosis was 61 years (31–84 years). Aggressive features such as extrathyroid extension 11/14 (78.57%), positive surgical margins 11/14 (78,57%), lymph node metastases 7/14 (50%), multifocality 6/14 (42.85%), regional tissue infiltration 11/14 (78.57%) and distant metastases 4/14 (28.57%) were observed. Long-term follow-up (median 40 months) demonstrated a high rate of locoregional recurrence in 12/14 (85.71%) individuals. Pulmonary and other distant metastases were observed in 4/14 (28.57%) patients, with mortality in 3/14 (21.42%) individuals.

Conclusion: In patients with classical type of WDTC characterized by excellent prognosis, extremely aggressive entities might be observed, making WDTC in some cases an unpredictable tumor.

Keywords: well-differentiated thyroid cancer, aggressive, metastases, multifocality

Introduction

In recent decades, we have observed a tremendous rise in the prevalence of well-differentiated thyroid cancer (WDTC), which is characterized by favorable prognosis.1–3 Papillary and follicular thyroid carcinomas (PTCs and FTCs) account for about 95% of all thyroid malignant tumors, forming the WDTC group.1,2 Both arise from follicular epithelial cells. The most common type is PTC, which owes its excellent prognosis to tumors of ≤1 cm in diameter, regardless of the existence of distant metastases. These tumors are defined as papillary thyroid microcarcinomas (PTMCs),3 and during recent years, they have become much more common.4,5 WDTCs often remain clinically silent for many years. Some of them are diagnosed during routine clinical examination followed by fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) and subsequently surgical treatment.6 The other tumors are diagnosed incidentally during histopathological examinations after surgery performed for benign thyroid disease.5,7 As with many other malignant tumors, thyroid cancers are classified according to the TNM classification proposed by the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer [UICC] and the American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] 7th edition, 2010.8 As for the prognosis of WDTC, not only is clinical staging taken under consideration, but also factors such as age, gender, histological type and subtype, DNA euploidy, microvessel count, CD97, E-cadherin, telomerase activity, and capsular and vascular invasion.9 The authors of this study added that many WDTCs are not clearly defined in terms of tumor prognosis. However, it was estimated that WDTCs in patients under the age of 45 years have rather excellent prognosis and are classified according to the UICC classification as stage I, or, if distant metastases are observed, as stage II. Several years ago, due to the wide range of different prognoses in cases of classical type WDTCs, the American Thyroid Association (ATA) and the British Thyroid Association classified these tumors in the three categories of risk aggressiveness (low, middle, and high). The excellent prognosis of the majority of cases of WDTC is reflected in 5-year survival rates as high as 93% for women and 88% for men for all patients. Survival is poorer for patients over 45 years of age at the time of diagnosis and for those with distant metastases.10 According to the ATA guidelines, patients below 45 years with PTC and distant metastases have a 100% 5-year disease-specific survival, while those above 45 years with distant metastases have a 51% 5-year disease-specific survival.11 The clinically relevant features that define the classical type of WDTC with a low risk of aggressiveness are pT1a solitary or multiple, N0/Nx, pT1b N0/Nx, pT2 N0/Nx, pT3>4 cm N0/Nx, tumor diameter below 4 cm and intrathyroid, R0 or R1 resection, and M0. The features connected with a high risk of WDTC are pT4 and M1 or R2 resection.12 However, on the basis of our own observation and subsequent postsurgical follow-up, this risk stratification does not always correspond with clinical outcome. In addition to the previously mentioned suggestions that primary tumor size, extrathyroid extension, and distant metastases are strongly correlated with patient prognosis, we sometimes observe completely different situations. Some authors confirm overall excellent prognosis of classical type PTC, and the other types of PTC, such as tall cell variant, are considered independent poor prognostic factors.13 However, others do not agree with this opinion.14 They say that the higher risk for poor prognosis does not depend on the histopathological variant of PTC but rather on older age, larger tumor size, extrathyroidal extension and the higher stage, and grade of the tumor. Additionally, international guidelines do not accept histopathological variants of PTC such as tall cell carcinoma as higher risk factors.15 For example, the European Thyroid Association (ETA) and the ATA guidelines categorize the tall cell variant as a low and intermediate risk factor of PTC, respectively.16,17 In our study, we decided to evaluate patients with classical type WDTC. Generally, this type of WDTC is considered by all authors as one with the best prognosis. Currently, the incidence of WDTC has been increasing. The prognosis for this tumor is considered excellent; therefore, the general recommendations for surgical and adjuvant treatment might be less aggressive. We decided to present this case series of 14 individuals with the classical type of WDTC with adverse outcomes of surgical treatment so that we may now realize that they should be identified and treated aggressively with greater caution and attention.

Patients and methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of 4,327 patients consecutively admitted and surgically treated for thyroid pathology in the First Department and Clinic of General, Gastroenterological and Endocrine Surgery from January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2016. Demographic data, diagnostic results, clinical and histopathological characteristics, and outcomes were evaluated. As a main presurgical diagnostic test, all patients underwent UG-FNAB. Clinical and pathological classification was performed according to the TNM classification criteria (7th Edition, 2010) by the AJCC.8 All of the operations were performed by the same team of surgeons, and histopathological specimens were examined by two pathologists experienced in thyroid malignancy. Histopathology reports were analyzed to determine tumor size, subtype, immunohistological staining, aggressive characteristics such as extrathyroidal extension, surgical margins, surrounding organs, tissue infiltration, and lymph node metastases. Details on postoperative course and follow-up data such as time to recurrence, length of follow-up, distant metastases, and patient mortality were collected. Only patients with classical type WDTC and aggressive pathological and clinical features were analyzed.

Results

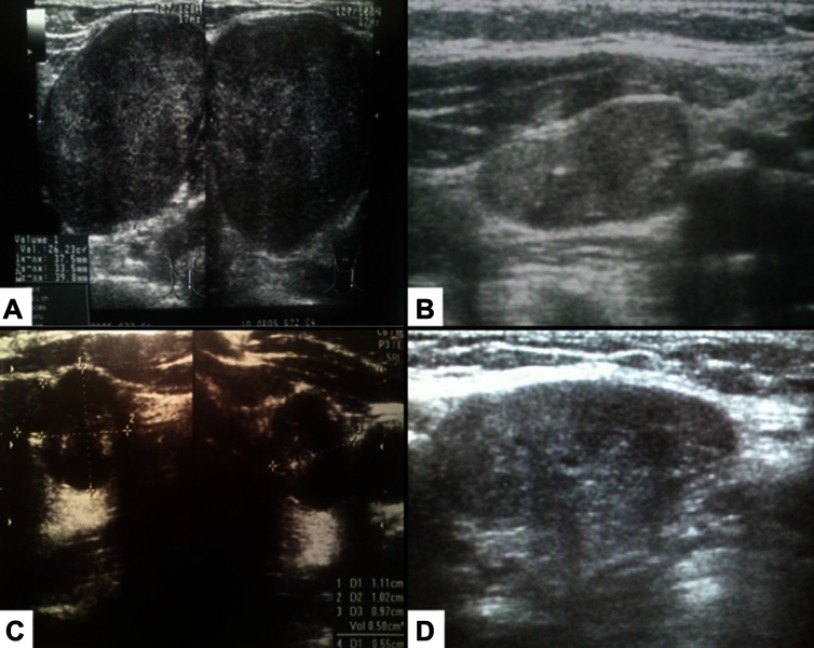

We evaluated 393 (9.08%) patients with thyroid malignancy. 348 (88.54%) of them were diagnosed as WDTC. There were 326 (82.95%) patients with PTC and 22 (5.59%) with FTC. In this homogenous group, we identified 14 (4.02%) patients with aggressive courses of the classical type of WDTC: 10 (2.87%) cases with PTC and 4 (1.14%) individuals with FTC. There were 11 (78.57%) females and 3 (21.43%) males. The mean ages of patients with PTC and FTC were 54.8 (±13.026) and 76.0 (±15.317), respectively (the difference was statistically significant). 11 (78.57%) patients were treated by total thyroidectomy with total or partial excision of the infiltrated adjacent structures. All of these patients received levothyroxine after thyroidectomy to suppress serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level to prevent the growth of TC. All patients had the classical type of WDTC in their tumor specimens, and 12 (85.71%) individuals had lymph node metastases found during follow-up for recurrent disease (Figure 1A–D), and 1 (7.14%) patient had neck skin metastases 1 year after thyroidectomy. 5 (35.71%) patients died as a result of WDTC dissemination. Uncontrolled local disease and distant metastases were presented at the time of death. 4 (28.57%) patients died due to unrelated diseases. 5 (35.71%) patients are still alive (from 2 to 9 years after surgical treatment).

Figure 1.

Lymph node metastases/recurrences of the aggressive forms of well-differentiated thyroid cancers. (A) 48-year-old woman with metastases of papillary thyroid cancer to the left neck lymph nodes. (B) 69-year-old woman with neck lymph node recurrence of follicular thyroid cancer 1 year after thyroidectomy. (C) 84-year-old woman with metastases of follicular thyroid carcinoma to the lymph nodes and lung. (D) 54-year-old man with papillary thyroid cancer and metastases to the lymph nodes and infiltration of the trachea and recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Patients with the aggressive form of the classical type of PTC

10 patients with the aggressive form of the classical type PTC are summarized in Table 1. The median age at the time of surgery was 54.8 (range 31–78 years), and 8 patients were females. 5 patients had multifocal tumors and 7 had extrathyroidal extension. 5 patients had nonradical surgery and 6 had lymph node metastases (Figure 1A–D). All 10 patients underwent RAI treatment. Nine patients had recurrent disease and 1 had vertebral column metastases (Figure 2C). The mean time to recurrence was 24 months (range 9–38 months).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of patients with the aggressive form of the classical type of WDTC

| Year | HP | Age | Gender | TNM (Figure) |

IHC | Site and time (months number) of recurrence (Figure) | Metastases (Figure) | Infiltration (Figure) | Symptoms (Figure) | TBSRTC Category | Treatment (Figure) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | PTC | 59 | Female | pT4mN1bM0 | CK19+HBME+CD56- | Neck lymph nodes | Lymph nodes | – | MNG (2A) | 2 | Total thyroidectomy |

| 2009 | FTC | 77 | Female | pT2mN1M1 | CK19++HBME+CD56- | Neck lymph nodes and skin (12) (2B) | Lymph nodes, neck skin (2B) | Trachea, neck muscle | Dyspnea | 3 | Total thyroidectomy |

| 2010 | PTC | 72 | Female | pT4N0M0 | TG++ EMA+, CK-8+ Kalc, LCA TTF CD20, CD79 | Neck lymph nodes (21) | – | Trachea (4AC) | Dyspnea (4AC) | 2 | Near-total thyroidectomy |

| 2011 | PTC | 61 | Female | pT1maN0M1 | CK19-Kalcyt-Chromogr-TG- | – | Vertebral column Th12/S1-2 (2D) | – | Back pain (2D) | – | Total thyroidectomy |

| 2011 | FTC | 84 | Female | pT4N1M1 | CK19- | – | Lymph nodes (1C), lungs | Left carotid | Neck tumor | 5 | Surgical biopsy |

| 2011 | PTC | 38 | Female | pT1maN0M0 | CK19++HBME+CD56- | Neck lymph nodes (23) | – | – | Thyroid tumor | 6 | Total thyroidectomy |

| 2015 | PTC | 54 | Male | pT4N1M0 | CK19++CD56- | Neck lymph nodes (19) | Lymph nodes (1D) | Trachea, RLN | Hoarseness | 4 | Near-total thyroidectomy |

| 2015 | PTC | 79 | Female | pT4aN1bM0 | CK19+HBME+CD56- | – | Lymph nodes | Trachea, esophagus (4D) | Dysphagia (4D), dyspnea | 5 | Surgical biopsy |

| 2015 | FTC | 74 | Male | pT4NxM0 | TTF+TG+CD56+CyklinaD1+CK19+HBME1-CEA-Kalcyt- | – | – | Trachea, right carotid, RLN | Dyspnea, hoarseness | 4 | Surgical biopsy |

| 2016 | PTC | 65 | Male | pT4mN0M0 | CK19++HBME++CD56- | Neck lymph nodes (19) | – | Trachea, RLN (4B) | Dyspnea, hoarseness | 5 | Near-total thyroidectomy (4B) |

| 2016 | FTC | 69 | Female | pT2N0M1 (3AC) | CD34- | Neck lymph nodes (12) (1B) | Vertebral column Th3 (3BD) | Trachea, | Paresis of the lower limbs (2C) | 5 | Total thyroidectomy |

| 2016 | PTC | 31 | Female | pT4mN1M0 | CK19+HBME+CK5/6-CD56- | Neck lymph nodes (13) | Lymph nodes | Trachea | Dyspnea | 5 | Near-total thyroidectomy |

| 2016 | PTC | 48 | Female | pT1aN1M0 | CK19++HBME+CD56- | Neck lymph nodes (10) | Lymph nodes (1A) | Trachea | Thyroid tumor | 5 | Total thyroidectomy |

| 2016 | PTC | 41 | Female | pT1bN1M0 | CK19+HBME-1+CD56+ | Neck lymph nodes | Lymph nodes | Trachea | Thyroid tumor | 5 | Total thyroidectomy |

Abbreviations: HP, histopathology; TNM, classification proposed by the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer [UICC] and the American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] 7th edition from 2010; IHC, immunohistochemistry; TBSRTC, The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytology; PTC, papillary thyroid cancer; FTC, follicular thyroid cancer; RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve; WDTC, well-differentiated thyroid cancer.

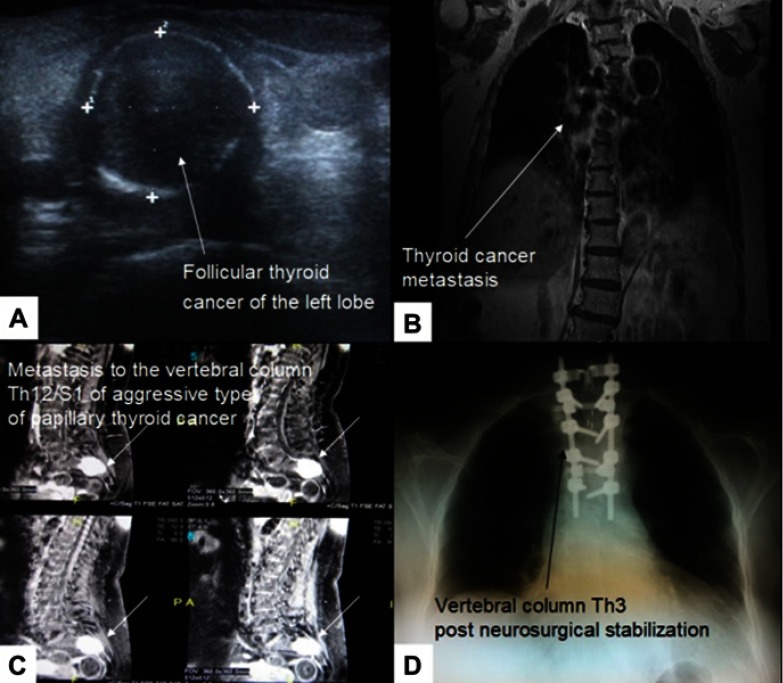

Figure 2.

(A) 69-year-old woman with a small follicular thyroid cancer localized in the left lobe. (B) Follicular thyroid cancer metastasis to Th3 of the vertebral column. (C) Aggressive type of the classical type of papillary thyroid cancer metastasis to S1 manifesting severe back pain several months before proper diagnosis in a 61-year-old female. (D) Th3 corporectomy and transpedicular stabilization of Th2 and Th4-Th6.

Patients with the aggressive form of the classical type of FTC

4 patients with the aggressive form of the classical type FTC are summarized in Table 1. The median age at the time of surgery was 76.0 (range 69–84 years), and 3 patients were females. 1 patient had multifocal tumor and 4 had extrathyroidal extension. 2 patients had nonradical surgery and 3 had lymph node metastases (Figure 1B,C; in one case, pN characteristic of the pTNM classification was not verified due to only one surgical biopsy performed). All 4 patients underwent RAI treatment. 3 patients had recurrent disease, 1 had vertebral column metastases (Figure 2A–D), and 1 had pulmonary metastases. The mean time to recurrence was 19 months (range 8–39 months).

Discussion

WDTC accounts for 2% of all human carcinomas, and it is estimated that this tumor is responsible for fewer than 0.5% of all cancer deaths.18 Generally, WDTC is considered a sporadic tumor with excellent prognosis. Local infiltration of WDTC to the surrounding anatomical structures, organs, and soft tissues localized in the neck is also an infrequent occurrence. In our study, the most common infiltrated organ was the trachea (11/14; 78%). The classical type of PTC in a majority of cases is indolent tumor with a 10-year survival of over 95%.19 One of the most common characteristics of the aggressiveness of the classical type of WDTC is its recurrence. This is observed in 8–23% of cases.20 Long-term follow-up (median 40 months) in our patients demonstrated a high rate of locoregional recurrence in 12/14 (85.71%) individuals, and pulmonary and other distant metastases in 4/14 (28.57%) patients. Some authors say that these patients who had one recurrence subsequently are at a higher risk of multiple recurrences.18 The mortality of patients with a recurrence of the classical type of WDTC has been estimated at 38–69%.21 In our patients, the mortality rate was 21% (3/14).

Although recently reported data suggest that some types of PTC, such as diffuse sclerosing, insular, tall, or columnar cells, present various stages of aggressiveness,22 in our study, we found that even classical type PTC might present very aggressive features. The same situation concerns the follicular variant of PTC. This estimation has very high clinical value because follicular variants of PTC are very difficult to distinguish from FTC and follicular adenoma. In our study, we identified 4 cases with classical type of FTC, and only in 2 (50%) individuals was malignancy suspected before surgery (categories 2 and 4 of The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology). Some authors suggest that the prognosis of WDTCs depends on whether they are invasive or totally encapsulated.23 In our study, this feature was observed in 78% of patients (11/14), so we agree with some authors’ opinion that, in addition to the histopathological type of WDTC, clinical stage may determine subsequent management after surgery.23 However, several years ago, some clinical features including histopathological type and subtype or molecular status were not taken into consideration in guideline recommendations for the planning of surgical treatment.24 Currently, the situation has totally changed, and all mentioned features are valuable in the planning of WDTC management.17 To plan proper surgical treatment, strict diagnosis of WDTC must be established. The crucial point is to detect the most aggressive forms of WDTC, especially within the classical type, which is considered the entity with excellent outcome. Some authors suggest that the prognosis of follicular type PTC is generally similar to that of classical type PTC with the exception of diffuse or multinodular follicular variants. In these cases, more aggressive behavior is usually observed.22 It was estimated that the tall cell variant of PTC is more aggressive than the classical type.25 Bernstein et al observed that in patients with the tall cell variant of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC), the spread of cancer outside of the thyroid gland occurred in 33%, whereas it was not observed in any patients with the classical type PTMC.26 In our study, we identified 3 (21%) patients with classical type PTMC, and all of them had aggressive clinical features (Table 1). Sometimes even small tumors may grow very aggressively, with potential for dedifferentiation. Some authors emphasized that some types of PTC must be distinguished from poorly differentiated thyroid cancer. These two extremely different groups of thyroid malignancy have the same growth pattern.25 As opposed to the classical type of PTC, the columnar variant is considered by most authors as the aggressive type, especially in older patients with larger tumors demonstrating diffuse infiltrative growth and extrathyroidal extension.25,26 However, some studies suggested that when the tumor is encapsulated, the patients have no poorer prognosis than those with classical type PTC.27 In our study, 2 patients had encapsulated tumor at the time of surgery (pT1ma); however, both presented with aggressive features (lymph node and vertebral column metastases) (Figure 2C).

In a small group of patients, even with the aggressive form of WDTC, the diagnosis of malignancy might be estimated postoperatively. In that case, the necessity for completion of primary surgery should be carefully assessed. This evaluation is especially important in the case of PTC, because as we know, more than 25% are multifocal; therefore, they might also be aggressive forms of PTC.9 In our study, almost half of the analyzed group (6/14) presented with multifocality as one of the aggressive features (Table 1).

The other aspect increasing the aggressiveness of the classical type of WDTC is the anatomic proximity of the neck organs to the thyroid gland, rendering them vulnerable to infiltration by this tumor. The most common infiltrated anatomical structure is the aerodigestive tract. In our study, we estimated that 71% (10/14) of patients had aerodigestive infiltration. The infiltration of these structures is the major cause of death in patients with aggressive forms of WDTC. In our study, 42% of patients (6/14) presented with dyspnea as the main symptom of aggressiveness of classical type WDTC (Table 1). Though local aggressiveness is rare in the classical type of WDTC, its early diagnosis is of particular importance because of its relatively benign nature and better responsiveness to surgical management. This makes the WDTC neoplasm group one that comprises tumors with various clinical and histopathological features. Although esophageal and laryngotracheal infiltration by WDTC is not a very common clinical situation, it also might be observed. Surgical treatment depends on the local tumor invasion. The surgery may consist of the shave procedure or radical organ resection. When the tumor adheres to local organs such as the larynx, trachea, or esophagus without transmural invasion, the removal of the malignant tissue is recommended as an organ function preservation procedure. In cases of transmural invasion, radical resection is recommended, such as thyroidectomy with leryngectomy.8 In our study, we observed (11/14) locoregional infiltration of the adjacent organs and tissues in 78% of patients. Only in 1 case did we have to perform partial resection of the infiltrated organ. In the last 9 cases, the shave procedure was performed without necessity of organ resection. In 10 cases, the infiltrated organ was the trachea; in the other cases, it was the esophagus (1 individual), carotid (2 patients), recurrent laryngeal nerve (3 patients), and muscles (1 patient) (Table 1).

During recent years, some authors have presented cases of aggressive forms of WDTC.22 They described them as quite aggressive and resistant to conventional treatment with surgery and radioiodine therapy. They added that some variants of PTC often present various degrees of aggressiveness from that observed in WDTC to undifferentiated thyroid carcinoma. These cases of WDTC usually present higher rates of metastases, recurrence, resistance to surgical treatment, and 131I therapy.28 Because of these tumors, other treatment methods are involved, including external radiation therapy, standard chemotherapy, and kinase inhibitor drugs such as sorafenib.22 The next very interesting question is, why in some entities of the classical type PTC very aggressive behavior is observed. In the aspect of mentioned features like resistance to surgical treatment and 131 I therapy, some specific molecular mechanisms should be analyzed. Volante et al identified the T1799A missense mutation in 15 Exon of the BRAF gene and rearranged during transfection gene (RET/PTC) rearrangement as the main and dominant genetic cancer pathogenesis mutation in the initiation of PTC.29 The authors noticed that this specific mutation leads to a constitutive activation of the retrovirus-associated DNA sequences (RAS), rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway.29 They described these molecular alterations mainly in diffuse sclerosing variant of PTC, exhibiting a higher frequency of cervical and distant metastases. However, it would be interesting to check the presence and occurrence of these genetic mechanisms in the aggressive entities of the classical type PTC.

One example of the aggressiveness of WDTC is a tumor arising as struma ovarii. This is a rare clinical finding, and proper management remains unclear.30 The majority of studies recommend radical pelvic resection in addition to total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine ablation. However, others suggest that extensive pelvic surgery and elective thyroidectomy to facilitate radioactive iodine therapy might be reserved for patients with gross extra-ovarian infiltration or distant metastases.30 In this location of the aggressive form of WDTC, radical pelvic resection might be performed, but we cannot carry out radical resection in the classical neck location.

Some authors suggest that certain variants of WDTC may be independent high-risk factors for poor prognosis.15 We estimated that even in the classical type of WDTC, very aggressive forms might be observed. In our study, we observed a higher incidence of extrathyroidal invasion, adjacent organ and tissue infiltration, distant metastases, and recurrence. Our study provided important evidence that even in such a homogenous group as the classical type of WDTC, some very aggressive entities might occur. Finally, we undertook these analyses because of the results of some other studies such as that of Kuo et al. These authors compared the classical type of PTC with the tall cell variant and did not find significant differences in overall and disease-specific survival.31

On the basis of our observations, we believe that even in the classical type of WDTC characterized by an excellent prognosis, very aggressive entities might be observed. In such cases, even after very extensive surgical procedures with lymph node dissection performed for small intrathyroidal tumors, early distant metastases and local recurrence might appear. On the other hand, we want to emphasize that very aggressive entities of the classical type of WDTC are rare findings. They are associated with aggressive histopathologic features and poor long-term outcomes. Surgery is the treatment of choice for all WDTCs, even those with very aggressive behavior. Thus, patients with the aggressive classical type of WDTC should have close, life-long surveillance and ought to be treated according to evidence-based guidelines for high-risk TC. All of these characteristics make this type of cancer unpredictable.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to all the staff at the study center who contributed to this study. This work did not receive any specific funding.

Ethical approval and informed consent

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Wroclaw Medical University (signature number: KB-296/2015). Written consent was obtained from all of the participants included in this study.

Disclosure

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Manzella L, Stella S, Pennisi MS, et al. New insights in thyroid cancer and p53 family proteins. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E1325. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pani F, Macerola E, Basolo F, Boi F, Scartozzi M, Mariotti S. Aggressive differentiated thyroid cancer with multiple metastases and NRAS and TERT promoter mutations: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:2186–2190. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sobin LH. Histological typing of thyroid tumours. Histopathology. 1990;16:513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb01559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris LG, Sikora AG, Tosteson TD, Davies L. The increasing incidence of thyroid cancer: the influence of access to care. Thyroid. 2013;23:885–891. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaliszewski K, Strutyńska-Karpińska M, Zubkiewicz-Kucharska A, et al. Should the prevalence of incidental thyroid cancer determine the extent of surgery in multinodular goiter? PLoS One. 2016;11:e0168654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaliszewski K, Diakowska D, Wojtczak B, et al. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy as a preoperative procedure in patients with malignancy in solitary and multiple thyroid nodules. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuttle RM, Ball DW, Byrd D, et al. National comprehensive cancer network. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:1228–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratmann M, Sekulla C, Dralle H, Brauckhoff M. Current TNM system of the UICC/AJCC: the prognostic significance for differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Chirurg. 2012;83:646–651. doi: 10.1007/s00104-011-2216-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gimm O, Dralle H. Differentiated thyroid carcinoma In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, editors. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Munich: Zuckschwerdt; 2001. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6979/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agate L, Lorusso L, Elisei R. New and old knowledge on differentiated thyroid cancer epidemiology and risk factors. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012;35:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edge SE, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A III, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paschke R, Lincke T, Müller SP, Kreissl MC, Dralle H, Fassnacht M. The treatment of well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:452–458. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erler P, Keutgen XM, Crowley MJ, et al. Dicer expression and microRNA dysregulation associate with aggressive features in thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2014;156:1342–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michels JJ, Jacques M, Henry-Amar M, Bardet S. Prevalence and prognostic significance of tall cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunalp B, Okuyucu K, Ince S, Ayan A, Alagoz E. Impact of tall cell variant histology on predicting relapse and changing the management of papillary thyroid carcinoma patients. Hell J Nucl Med. 2017;20:122–127. doi: 10.1967/s002449910552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pacini F, Schlumberger M, Dralle H, Elisei R, Smit JWA, Wiersinga W. European thyroid cancer T: European consensus for the management of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma of the follicular epithelium. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:787–803. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American thyroid association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American thyroid association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26:1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palme CE, Waseem Z, Raza SN, Eski S, Walfish P, Freeman JL. Management and outcome of recurrent well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:819–824. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.7.819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark OH. Thyroid cancer and lymph node metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2011;1003:615–618. doi: 10.1002/jso.21804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzaferri E, Jhiang SM. Long-term impact of initial surgical and medical therapy on papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. Am J Med. 1994;97:418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tubiana M, Schlumberger M, Rougier P, et al. Long term results and prognostic factors in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Cancer. 1985;55:794–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miftari R, Topciu V, Nura A, Haxhibeqiri V. Management of the patient with aggressive and resistant papillary thyroid carcinoma. Med Arch. 2016;70:314–317. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2016.70.314-317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pillai S, Gopalan V, Smith RA, Lam AKY. Diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma – an update of its clinic pathological features and molecular biology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;94:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dralle H, Musholt TJ, Schabram J, et al. German association of endocrine surgeons practice guideline for the surgical management of malignant thyroid tumors. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:347–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nath MC, Erickson LA. Aggressive variants of papillary thyroid carcinoma: hobnail, tall cell, columnar, and solid. Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25:172–179. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaliszewski K, Diakowska D, Strutyńska-Karpińska M, et al. Diagnostics of thyroid malignancy and indications for surgery in the elderly and younger counterparts: comparison of 3,749 patients. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1012451. doi: 10.1155/2017/1012451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yunta PJ, Ponce JL, Prieto M, Merino F, Sancho-Fornos S. The importance of a tumor capsule in columnar cell thyroid carcinoma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Thyroid. 1999;9:815–819. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sacks W. Management of aggressive metastatic papillary thyroid cancer involves multiple treatment methods. Clin Thyroidology. 2013;25:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volante M, Collini P, Nikiforov Y, et al. Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma: the Turin proposal for the use of uniform diagnostic criteria and an algorithmic diagnostic approach. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1256–1264. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3180309e6a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marti JL, Clark VE, Harper H, et al. Optimal surgical management of well-differentiated thyroid cancer arising in struma ovarii: a series of 4 patients and a review of 53 reported cases. Thyroid. 2012;22:400–406. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuo EJ, Goffredo P, Sosa JA, Roman SA. Aggressive variants of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma are associated with extrathyroidal spread and lymph-node metastases: a population-level analysis. Thyroid. 2013;23:1305–1311. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]