Summary

Background

High blood pressure is common in acute stroke and is a predictor of poor outcome; however, large trials of lowering blood pressure have given variable results, and the management of high blood pressure in ultra-acute stroke remains unclear. We investigated whether transdermal glyceryl trinitrate (GTN; also known as nitroglycerin), a nitric oxide donor, might improve outcome when administered very early after stroke onset.

Methods

We did a multicentre, paramedic-delivered, ambulance-based, prospective, randomised, sham-controlled, blinded-endpoint, phase 3 trial in adults with presumed stroke within 4 h of onset, face-arm-speech-time score of 2 or 3, and systolic blood pressure 120 mm Hg or higher. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive transdermal GTN (5 mg once daily for 4 days; the GTN group) or a similar sham dressing (the sham group) in UK-based ambulances by paramedics, with treatment continued in hospital. Paramedics were unmasked to treatment, whereas participants were masked. The primary outcome was the 7-level modified Rankin Scale (mRS; a measure of functional outcome) at 90 days, assessed by central telephone follow-up with masking to treatment. Analysis was hierarchical, first in participants with a confirmed stroke or transient ischaemic attack (cohort 1), and then in all participants who were randomly assigned (intention to treat, cohort 2) according to the statistical analysis plan. This trial is registered with ISRCTN, number ISRCTN26986053.

Findings

Between Oct 22, 2015, and May 23, 2018, 516 paramedics from eight UK ambulance services recruited 1149 participants (n=568 in the GTN group, n=581 in the sham group). The median time to randomisation was 71 min (IQR 45–116). 597 (52%) patients had ischaemic stroke, 145 (13%) had intracerebral haemorrhage, 109 (9%) had transient ischaemic attack, and 297 (26%) had a non-stroke mimic at the final diagnosis of the index event. In the GTN group, participants' systolic blood pressure was lowered by 5·8 mm Hg compared with the sham group (p<0·0001), and diastolic blood pressure was lowered by 2·6 mm Hg (p=0·0026) at hospital admission. We found no difference in mRS between the groups in participants with a final diagnosis of stroke or transient ischaemic stroke (cohort 1): 3 (IQR 2–5; n=420) in the GTN group versus 3 (2–5; n=408) in the sham group, adjusted common odds ratio for poor outcome 1·25 (95% CI 0·97–1·60; p=0·083); we also found no difference in mRS between all patients (cohort 2: 3 [2–5]; n=544, in the GTN group vs 3 [2–5]; n=558, in the sham group; 1·04 [0·84–1·29]; p=0·69). We found no difference in secondary outcomes, death (treatment-related deaths: 36 in the GTN group vs 23 in the sham group [p=0·091]), or serious adverse events (188 in the GTN group vs 170 in the sham group [p=0·16]) between treatment groups.

Interpretation

Prehospital treatment with transdermal GTN does not seem to improve functional outcome in patients with presumed stroke. It is feasible for UK paramedics to obtain consent and treat patients with stroke in the ultra-acute prehospital setting.

Funding

British Heart Foundation.

Introduction

High blood pressure is common in acute stroke and is a predictor of poor outcome; however, large trials investigating lowering blood pressure have given variable results, and the management of high blood pressure in acute stroke remains unclear,1 although lowering blood pressure in intracerebral haemorrhage is recommended in hospital.2 Nitric oxide (NO) donors are candidate treatments for acute stroke because of their cerebral and systemic vasodilatory action, which leads to a reduction in blood pressure. Preclinical stroke studies3, 4 found that NO donors improved regional cerebral blood flow and reduced stroke lesion size if administered rapidly. Further, vascular NO concentrations are low in acute stroke and are associated with a poor outcome,5, 6 raising the possibility that supplementing NO might be beneficial.

Five randomised trials7, 8, 9, 10, 11 of an NO donor, transdermal glyceryl trinitrate (GTN; also known as nitroglycerin), in acute stroke showed that GTN lowered peripheral and central blood pressure, 24 h blood pressure, pulse pressure, and augmentation index. Conversely, GTN had no effect on middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity, cerebral blood flow, intracranial pressure, or platelet function.7, 8, 9 Although four of the trials7, 8, 9, 11 were neutral for functional outcome, GTN improved functional outcome in the phase 2 Rapid Intervention with Glyceryl trinitrate in Hypertensive stroke Trial (RIGHT),10 with randomisation by paramedics within 4 h of stroke, and in a prespecified subgroup analysis of the phase 3 hospital-based Efficacy of Nitric Oxide in Stroke trial (ENOS),11, 12 with randomisation within 6 h of stroke. Summary and individual patient data meta-analyses13, 14 of these five trials suggested that very early administration of GTN within 6 h of onset (n=312) was beneficial in both ischaemic stroke and intracerebral haemorrhage, and reduced death, disability, cognitive impairment, mood disturbance, and poor quality of life. Beyond 6 h, treatment effects were neutral.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science for relevant articles on Sept 12, 2018, using the search terms “stroke”, “cerebrovascular accident”, “nitric oxide donor”, and “randomised controlled trial”. We also manually searched original articles and reviews in our own reference library. Searches were restricted to completed trials in humans with abstracts or full texts published and relating to administration of glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) within 6 h of stroke onset, and in which information on functional outcome and death was available. When combining results from two randomised controlled patient-masked trials with blinded-outcome assessment, one a pilot ambulance-based study and the other a prespecified subgroup of a large hospital-based trial, treatment with GTN within the first 6 h of stroke onset was associated with less death and reduced death or dependency, both overall and separately in ischaemic stroke and intracerebral haemorrhage.

Added value of this study

Ultra-acute administration of GTN in the ambulance within 4 h of stroke onset did not alter functional outcome in patients suspected to have stroke. It was feasible for UK paramedics to recruit, obtain consent, and treat patients with stroke in the prehospital environment.

Implications of all the available evidence

We did not find evidence that ultra-early administration of transdermal GTN improves functional outcome or reduces death in patients with suspected ultra-acute stroke. Large paramedic-delivered trials are possible in the UK.

For stroke interventions that do not require previous neuroimaging and that might have benefit in both ischaemic stroke and intracerebral haemorrhage, treatment before hospital admission will reduce time to initiation of treatment. The Field Administration of Stroke Therapy-Magnesium (FAST-MAG) ambulance-based stroke trial15 successfully recruited 1700 patients in the USA, but no previous large prehospital stroke trials have been completed in the UK.

We did the phase 3 RIGHT-2 trial to assess the safety and efficacy of GTN when given very early after presumed stroke onset by paramedics before participants were admitted to hospital. We also assessed the feasibility of performing a large multicentre, ambulance-based, paramedic-delivered trial in patients with presumed stroke in the UK.

Methods

Study design and participants

RIGHT-2 was a pragmatic, multicentre, paramedic-delivered, ambulance-based, prospective, randomised, sham-controlled, participant-blinded and outcome-blinded, phase 3 trial in adult participants with ultra-acute presumed stroke within 4 h of onset in the UK.

Adult patients were eligible for inclusion after an emergency telephone call (to 999 UK ambulance services) for presumed stroke if they presented within 4 h of onset of their symptoms to a trial-trained paramedic from a participating ambulance service and could be taken to a participating hospital. Patients had to have a face-arm-speech-time (FAST) score of 2 or 3 (thus ensuring the presence of motor weakness), and a systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg or higher. Patients from a nursing home, with reduced consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score, <8 of 15), with hypoglycaemia (capillary glucose concentration <2·5 mmol/L), or who had a witnessed seizure were excluded (see appendix for a complete list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Paramedics managed the primary consent process, and patients with capacity gave written informed consent that covered the whole trial. If capacity was absent, proxy consent was obtained from an accompanying relative, carer, or friend, if present, or from the paramedic if no accompanying person was present (as done in RIGHT).10 Confirmatory consent was obtained from the patient, or their relative, carer, or friend (if available) in hospital when the patient lacked capacity in the ambulance.

The final diagnosis was made after arrival to a participating hospital by the principal investigator based on clinical and neuroimaging findings and was categorised as intracerebral haemorrhage, ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, or non-stroke or transient ischaemic attack mimic.

The study was approved by the UK regulator (Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, reference: 03057/0064/001–0001; Eudract 2015–000115–40) and national research ethics committee (IRAS: 167115) and was adopted by the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network.

Details of the trial design, statistical analysis plan, and baseline data have been published,16, 17, 18 and the design and protocol are summarised in the appendix. The study protocol is available online.

Randomisation and masking

Patients were enrolled and randomly assigned (1:1) by paramedics to receive transdermal GTN (5 mg as Transiderm-Nitro 5, Novartis, Frimley, UK; the GTN group) or a similar-appearing sham skin dressing (DuoDERM hydrocolloid dressing, Convatec, Flintshire, UK; the sham group). Randomisation was stratified by ambulance station with blocks of four packs (two active, two control) in a random permuted order. Each treatment pack was sealed to maintain blinding of paramedics. Ambulances carried only one pack at a time—paramedics signed-out the treatment pack with the lowest randomisation number from their ambulance station at the start of their shift and returned it if unused at the end of their shift. Opened but unused packs were returned to the coordinating centre. GTN patches or sham dressings came in marked sealed sachets so paramedics and nurses doing medication rounds in hospital knew treatment assignment. However, participants were effectively masked since the patches and dressings themselves were unlabelled, and a gauze dressing was taped over the top of the patch or dressing to provide additional masking.

Procedures

The first treatment (GTN or sham) was administered by the paramedic immediately after randomisation in the ambulance, and further treatments were given to the patient for up to 3 days while in hospital. Patches or dressings were placed on the shoulder or back and the site changed daily.

Ambulance data (before and after first treatment) and hospital-collected clinical and neuroimaging data at admission (after first treatment), day 4 (end of treatment), and on death or discharge were entered online into a secure web-based database system. These data were then validated and used to confirm the patient's eligibility.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was functional outcome assessed with the 7-level modified Rankin Scale (mRS), measured at 90 days after randomisation.19 mRS scores range from 0 to 6, with a score of 0 indicating no symptoms, 1 indicating some symptoms, 2–5 indicating increasing levels of disability and dependency, and 6 indicating death. Outcomes were recorded centrally by telephone by a trained assessor masked to treatment allocation; to ensure reliable scoring, raters used a structured questionnaire.20 If the participant could not be contacted by telephone (after multiple attempts), a questionnaire covering the same outcome measures was sent by post. The primary analysis involved a comparison of the distribution of all 7 levels of the mRS (shift) between the treatment groups.21

Participants were seen at day 4 (or at discharge, if earlier) to assess adherence to treatment and neurological deterioration (increase in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] by at least 4 points from hospital admission to day 4 or worsening conscious level in the NIHSS consciousness domain item 1a). At discharge from hospital, duration of stay and discharge destination (to institution or home) were recorded. Prespecified secondary outcomes at day 90 included activities of daily living (Barthel Index), cognition (modified telephone Mini-Mental State Examination [t-MMSE], Telephone Interview for Cognition Scale-modified [TICS-M], categorical verbal fluency [with the use of animal naming]), health-related quality of life (European Quality of Life-5 dimensions-3 level [EQ-5D-3L], from which a health status utility value [HSUV] was calculated, EQ-visual analogue scale [EQ-VAS]), and mood (abbreviated Zung depression score [ZDS]) were recorded—all of which were used in ENOS.11

Safety outcomes included all-cause and cause-specific case fatality, hypotension or hypertension occurring during the first 4 days (as reported by investigators), and serious adverse events (all up to day 5, and fatal from day 5). Serious adverse events were validated and categorised by expert adjudicators who were masked to treatment assignment.

Plain brain scans (CT or MRI) performed on arrival at hospital were collected for central adjudication by expert neuroradiologists with the use of assessments updated from ENOS.11 Depending on local practice, CT or MR angiography was also performed and adjudicated centrally (see appendix for more information). Imaging outcomes on admission to hospital included infarct extent (International Stroke Trial-3 score, Alberta Stroke Program Early CT score), presence of hyperdense artery, haemorrhagic transformation, and mass effect, including midline shift for participants with ischaemic stroke, haematoma location, size, volume, extension (to subarachnoid spaces or ventricles), and mass effect, including midline shift for intracerebral haemorrhage, and type and location of mimics. On the next day, a research CT or MRI scan was done to assess safety; the same factors were assessed as above for ischaemic stroke and intracerebral haemorrhage.22

An independent Data Monitoring Committee reviewed unblinded data every 6 months and did a formal interim analysis midway through the trial (see appendix for description of the stopping rules); this analysis was done after 714 patients had been recruited and followed up at 90 days and the Data Monitoring Committee recommended that the trial should continue.

Statistical analysis

We required a total sample size of 850 participants (425 in each group) to detect a shift in mRS with a common odds ratio [OR] of 0·70,17 assuming an overall significance level of 5%, 90% power, distribution of mRS scores as shown in the appendix,10 3% loss to follow-up, mimic and transient ischaemic attack rate of 20%, and reduction for baseline covariate adjustment of 20%.23 During the trial, we noted the non-stroke diagnosis rate exceeded 30%. Since this mimic rate would reduce the number of participants recruited with a stroke diagnosis, and therefore the statistical power in this group, we increased the overall sample size from 850 to 1050 to maintain the overall effect size and statistical power. Further, a decision was made by the Trial Steering Committee to do a hierarchical analysis, comprising a sequential analysis done in two progressively inclusive cohorts based on the final in-hospital diagnosis: participants with confirmed stroke or transient ischaemic attack (cohort 1, target disease population) and stroke, transient ischaemic attack, or non-stroke or transient ischaemic attack (mimic)—ie, all patients (cohort 2, intention-to-treat [ITT]). Further information is given in the appendix.

We assessed the primary outcome using ordinal logistic regression with adjustment for age, sex, premorbid mRS, FAST score, baseline systolic blood pressure, index event (intracerebral haemorrhage, ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, mimic), time to randomisation, and reperfusion treatment (thrombectomy, alteplase, none).17 We tested the assumption of proportional odds using the likelihood ratio test. We assessed heterogeneity of the treatment effect on the primary outcome in prespecified subgroups by adding an interaction term to an adjusted ordinal logistic regression model. An unadjusted and per-protocol (as defined in the appendix) analysis is shown for completeness. We analysed death using Kaplan-Meier and adjusted Cox regression models. We assessed other outcomes using adjusted binary logistic regression (neurological deterioration, headache, hypotension, hypertension, feeding status, disposition, death in hospital), Cox regression (death), ordinal logistic regression (mRS, disposition), multiple linear regression (NIHSS, length of stay in hospital, t-MMSE, TICS-M, animal naming, ZDS, EQ-5D-HSUV, and EQ-VAS) and analysis of covariance (blood pressure). We analysed a global outcome (comprising ordered categorical or continuous data for mRS, Barthel Index, ZDS, TICS-M, and EQ-5D-HSUV) using the Wei-Lachin test.24 Participants who did not receive their assigned treatment, who did not adhere to the protocol, or who had a stroke mimic were still followed up in full at day 90 and are included in the main analyses. We made no adjustments for multiplicity of testing since all secondary analyses were hypothesis-generating and designed to support the primary analysis. We did primary analyses as randomised (cohort 2) using observed outcome data only with SAS software (version 9.4). In sensitivity analyses, we performed a per-protocol analysis, and missing mRS data were imputed using multiple regression-based imputation.

Role of the funding source

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation [grant number CS/14/4/30972] and sponsored by the University of Nottingham. There was no commercial support for the trial, and GTN patches and sham dressings were sourced by the Pharmacy at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust. The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author and two statisticians (PS, LJW) had full access to all the data in the study and the corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

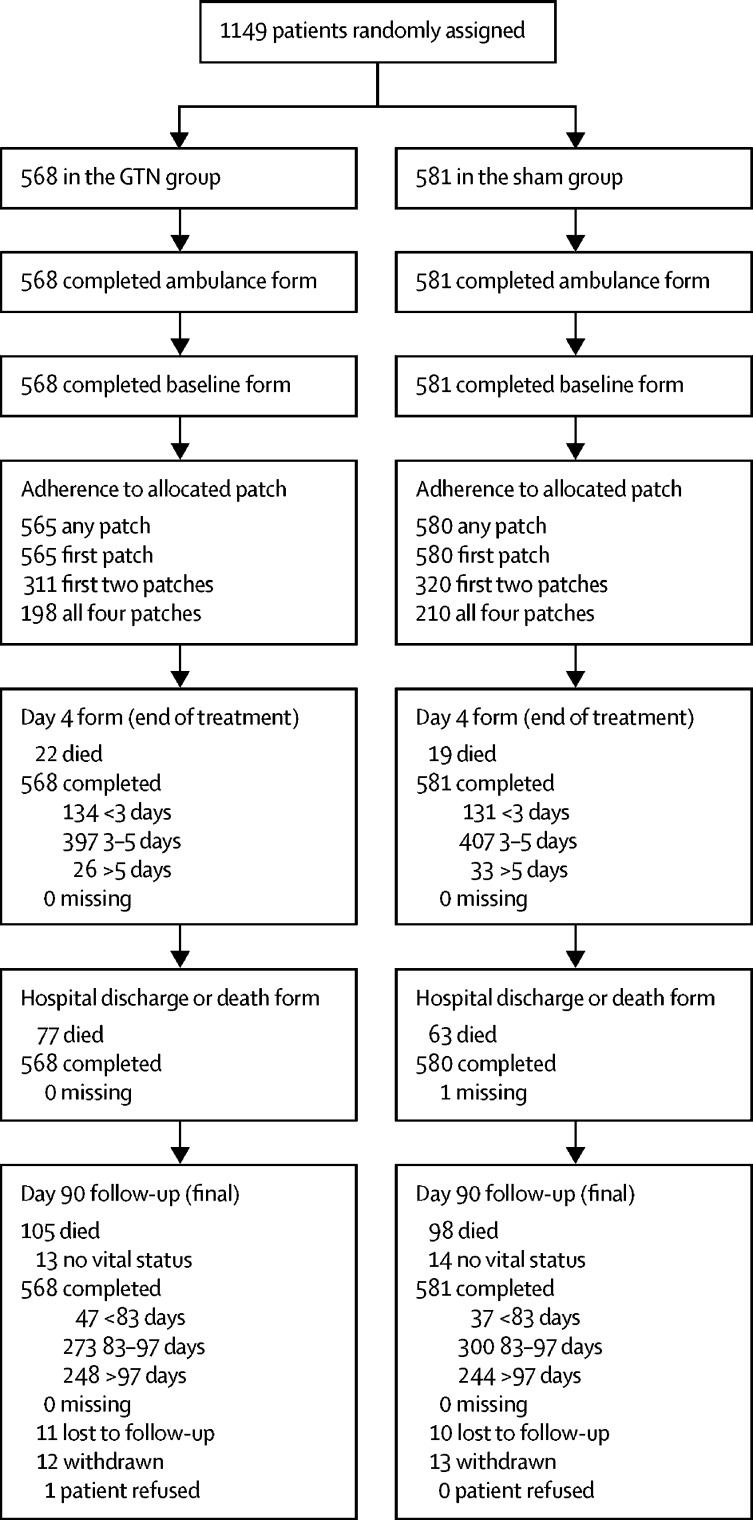

Between Oct 22, 2015, and May 23, 2018 (appendix), 1149 participants (cohort 2) were enrolled and randomly assigned (n=568 to the GTN group; n=581 to the sham group; figure 1) by 516 (35%) of 1492 trial-trained paramedics based at 184 ambulance stations in eight (62%) of 13 ambulance services in England and Wales; these participants were taken to 54 hospitals. For logistical reasons, screening logs were not kept. All patients gave consent in the ambulance, which was obtained from 603 (53%) patients, 429 (37%) relatives, carers, or friends, and 117 (10%) paramedics. Demographic and clinical characteristics were similar in the two treatment groups across cohort 1 and cohort 2 (table 1). The mean age was 72·5 years (SD 14·6), women comprised 48% of the participants, 60% of participants had a maximum FAST score of 3, and 26% had a GCS of less than 14. The final diagnosis of the qualifying event was 52% ischaemic stroke, 13% intracerebral haemorrhage, 9% transient ischaemic attack, and 26% stroke or transient ischaemic attack-mimicking condition. Common causes of stroke mimics included seizure (n=50 [18%]), migraine (n=49 [17%]), and functional symptoms (n=41 [14%]).

Figure 1.

Trial profile for cohort 2

Cohort 2 includes all patients (intention-to-treat population). GTN=glyceryl trinitrate.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics in the ambulance and at hospital admission

|

Patients with confirmed stroke or transient ischaemic attack (cohort 1)* |

All patients (cohort 2)† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTN group | Sham group | GTN group | Sham group | ||

| Ambulance data (before randomisation) | |||||

| Number of patients | 434 | 418 | 568 | 581 | |

| Consent | |||||

| Participant | 220 (51%) | 206 (49%) | 296 (52%) | 307 (53%) | |

| Relative, carer, or friend | 169 (39%) | 172 (41%) | 213 (38%) | 216 (37%) | |

| Paramedic | 45 (10%) | 40 (10%) | 59 (10%) | 58 (10%) | |

| Age, years | 73·7 (12·8) | 75·3 (12·3) | 72·3 (14·6) | 72·7 (14·6) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 234 (54%) | 220 (53%) | 294 (52%) | 300 (52%) | |

| Women | 200 (46%) | 198 (47%) | 274 (48%) | 281 (48%) | |

| Time from onset to randomisation, min | 70 (45–107) | 70 (45–110) | 70 (45–115) | 72 (45–118) | |

| Electrocardiogram, atrial fibrillation or flutter | 81 (24%) | 77 (22%) | 92 (21%) | 95 (20%) | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 163·4 (24·5) | 163·0 (24·9) | 161·5 (24·7) | 162·8 (25·5) | |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 92·2 (19·1) | 91·5 (17·8) | 91·5 (18·5) | 91·6 (17·2) | |

| Heart rate, beats per min | 81·6 (18·7) | 82·2 (18·6) | 81·7 (18·0) | 82·6 (19·2) | |

| Glasgow Coma Scale <14 | 123 (28%) | 106 (25%) | 162 (29%) | 140 (24%) | |

| FAST score of 3 | 276 (64%) | 270 (65%) | 343 (60%) | 347 (60%) | |

| Hospital admission data (after randomisation) | |||||

| Number of patients | 434 | 418 | 568 | 581 | |

| Ethnic group, non-white | 35 (8%) | 43 (10%) | 50 (9%) | 63 (11%) | |

| Premorbid mRS >2 | 76 (18%) | 68 (16%) | 115 (20%) | 108 (19%) | |

| Medical history | |||||

| Hypertension | 252 (58%) | 249 (60%) | 313 (56%) | 330 (58%) | |

| Diabetes | 82 (19%) | 86 (21%) | 109 (20%) | 118 (21%) | |

| Previous stroke | 100 (23%) | 87 (21%) | 137 (25%) | 135 (24%) | |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 66 (15%) | 72 (17%) | 95 (17%) | 101 (18%) | |

| Current smoking | 63 (18%) | 51 (15%) | 89 (19%) | 79 (17%) | |

| Qualifying event | |||||

| Ischaemic stroke | 302 (70%) | 295 (71%) | 302 (53%) | 295 (51%) | |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | 74 (17%) | 71 (17%) | 74 (13%) | 71 (12%) | |

| Stroke type unknown | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 57 (13%) | 52 (12%) | 57 (10%) | 52 (9%) | |

| Non-stroke or transient ischaemic attack mimic | .. | .. | 134 (24%) | 163 (28%) | |

Data are n (%), mean (SD), and median (IQR). GTN=glyceryl trinitrate. FAST=face-arm-speech-time test. mRS=modified Rankin Scale.

Target disease population.

Intention-to-treat population.

The median time from the onset of symptoms to randomisation was 71 min (IQR 45–116) and to start of study drug 73 min (48–118) . Overall, the study drug was received within 30 min of symptom onset in 59 (5%) participants, within 60 min in 439 (38%) participants, and within 120 min in 865 (75%) participants.

Adherence to the first randomised treatment was excellent in both the confirmed stroke or transient ischaemic attack group (cohort 1: 849 (>99%) of target disease population) and in all participants (cohort 2: 1145 (>99%) of ITT population; appendix). In the per-protocol definition of adherence, which required that at least the first two doses of treatment were received, only 571 (67%) of cohort 1 and 631 (55%) of cohort 2 were adherent; common reasons for non-adherence were a diagnosis of non-stroke, early discharge, a medical decision to stop randomised treatment, a procedural error, or missing trial medication (appendix). Just 382 (45%) of participants with a stroke or transient ischaemic attack (cohort 1), and 408 (36%) of participants overall (cohort 2), received all 4 days of treatment.

There were 38 protocol violations in the ambulance and these mainly comprised inclusion of patients beyond 4 h, with a FAST score of less than 2, a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg, or who were from a nursing home (appendix). The most common protocol violations in hospital involved not administering the second day's treatment or failure to obtain secondary consent.

In cohort 1, systolic blood pressure at baseline was 163·2 mm Hg (SD 24·7) and diastolic was 91·9 mm Hg (18·5; table 1) and reduced in both GTN and sham groups over the 4 days after randomisation (appendix). After treatment, systolic blood pressure reduced by 5·8 mm Hg (p<0·0001) at hospital admission and diastolic by 2·6 mm Hg (p=0·0026) in the GTN group compared with the sham group. At day 2, systolic blood pressure reduced by 5·3 mm Hg (p=0·00016) and diastolic by 2·6 mm Hg (p=0·0054) in the GTN group compared with the sham group. The difference in blood pressure between the GTN and sham groups then diminished with no difference at days 3 and 4. Similar findings were seen for the effect of GTN on blood pressure in all patients (cohort 2; appendix). In all patients, symptomatic hypotension was more common in the GTN group (21 [4%] patients) than in the sham group (9 [2%] patients; adjusted OR [aOR] 2·49 [95% CI 1·11–5·57]; p=0·026; table 2). Heart rate did not differ between the treatment groups (data not shown).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes at day 4 and day 90 in cohort 1 and cohort 2

|

Cohort 1* |

Cohort 2† |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n=852) | GTN group (n=434) | Sham group (n=418) | acOR, aOR, aDIM, or aHR (95% CI) | p value | Number of patients (n=1149) | GTN group (n=568) | Sham group (n=581) | acOR, aOR, aDIM, or aHR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Day 90 mRS, maximum score of 6 (primary outcome) | 828 | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 1·25 (0·97 to 1·60) | 0·083 | 1102 | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 1·04 (0·84 to 1·29) | 0·69 | |

| Sensitivity analyses | |||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 828 | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 1·05 (0·83 to 1·33) | 0·70 | 1102 | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 0·99 (0·81 to 1·22) | 0·96 | |

| Mean | 828 | 3·4 (2·0) | 3·4 (1·9) | 0·14 (−0·07 to 0·36) | 0·19 | 1102 | 3·2 (2·0) | 3·2 (1·9) | 0·01 (−0·17 to 0·19) | 0·92 | |

| mRS >2 | 828 | 286 (68%) | 282 (69%) | 1·11 (0·79 to 1·57) | 0·55 | 1102 | 358 (66%) | 373 (67%) | 1·02 (0·76 to 1·38) | 0·88 | |

| Per protocol | 714 | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 1·22 (0·93 to 1·60) | 0·14 | 959 | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 1·05 (0·84 to 1·33) | 0·65 | |

| Imputed | 852 | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 1·23 (0·96 to 1·57) | 0·10 | 1149 | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 1·05 (0·85 to 1·30) | 0·65 | |

| Hospital admission | |||||||||||

| NIHSS, maximum score of 42 | 755 | 10·5 (7·6) | 10·4 (7·7) | 0·34 (−0·51 to 1·19) | 0·43 | 931 | 9·7 (7·6) | 9·4 (7·5) | 0·14 (−0·61 to 0·89) | 0·72 | |

| GCS, maximum score of 15 | 835 | 13·5 (2·3) | 13·8 (2·0) | −0·37 (−0·64 to −0·10) | 0·0068 | 1076 | 13·7 (2·2) | 13·9 (1·9) | −0·19 (−0·42 to 0·04) | 0·10 | |

| FAST, maximum score of 3 | 799 | 2·3 (0·9) | 2·2 (1·0) | 0·09 (−0·02 to 0·19) | 0·10 | 985 | 2·2 (1·0) | 2·1 (1·0) | 0·03 (−0·07 to 0·13) | 0·51 | |

| OCSP, TACS | 822 | 161 (38%) | 149 (37%) | 1·13 (0·82 to 1·55) | 0·45 | 1046 | 176 (34%) | 174 (33%) | 1·03 (0·78 to 1·37) | 0·83 | |

| Day 4 (discharge) | |||||||||||

| Death | 849 | 20 (5%) | 18 (4%) | 1·17 (0·57 to 2·39) | 0·68 | 1128 | 22 (4%) | 19 (3%) | 1·19 (0·60 to 2·35) | 0·63 | |

| Neurological deterioration‡ | 534 | 60 (23%) | 56 (21%) | 1·14 (0·74 to 1·77) | 0·56 | 586 | 62 (21%) | 59 (20%) | 1·08 (0·70 to 1·65) | 0·73 | |

| Headache§ | 843 | 41 (10%) | 28 (7%) | 1·41 (0·84 to 2·37) | 0·19 | 1117 | 49 (9%) | 36 (6%) | 1·43 (0·90 to 2·27) | 0·13 | |

| Hypotension§ | 844 | 18 (4%) | 9 (2%) | 2·07 (0·90 to 4·75) | 0·085 | 1118 | 21 (4%) | 9 (2%) | 2·49 (1·11 to 5·57) | 0·026 | |

| Hypertension§ | 844 | 89 (21%) | 93 (22%) | 0·82 (0·57 to 1·18) | 0·28 | 1118 | 106 (19%) | 108 (19%) | 0·96 (0·69 to 1·33) | 0·81 | |

| Feeding: non-oral | 806 | 123 (30%) | 132 (33%) | 0·89 (0·63 to 1·26) | 0·51 | 1049 | 130 (25%) | 139 (26%) | 0·89 (0·65 to 1·24) | 0·50 | |

| Events in hospital | |||||||||||

| Length of stay | 847 | 17·4 (29·7) | 19·1 (28·9) | −1·35 (−5·16 to 2·46) | 0·49 | 1126 | 14·6 (27·0) | 15·3 (25·7) | −1·09 (−4·00 to 1·81) | 0·46 | |

| Died | 847 | 72 (17%) | 60 (14%) | 1·28 (0·84 to 1·96) | 0·26 | 1126 | 78 (14%) | 63 (11%) | 1·35 (0·90 to 2·02) | 0·15 | |

| Died or in an institution | 831 | 180 (42%) | 167 (41%) | 1·17 (0·84 to 1·61) | 0·35 | 1102 | 193 (35%) | 186 (33%) | 1·08 (0·81 to 1·46) | 0·60 | |

| Day 90 | |||||||||||

| Death | 841 | 97 (23%) | 79 (19%) | 1·24 (0·91 to 1·68) | 0·17 | 1122 | 105 (19%) | 98 (17%) | 1·11 (0·84 to 1·47) | 0·47 | |

| Disposition, maximum score of 3¶ | 809 | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1·32 (0·96 to 1·82) | 0·086 | 1069 | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1·11 (0·83 to 1·47) | 0·48 | |

| EQ-5D-HSUV, maximum score of 1‖ | 798 | 0·4 (0·4) | 0·4 (0·4) | −0·02 (−0·07 to 0·03) | 0·42 | 1055 | 0·4 (0·4) | 0·4 (0·4) | 0·00 (−0·04 to 0·05) | 0·95 | |

| Barthel Index, maximum score of 100d | 795 | 56·2 (45·0) | 57·5 (43·9) | −2·74 (−7·82 to 2·33) | 0·29 | 1048 | 60·3 (43·7) | 61·3 (43·1) | −0·24 (−4·54 to 4·06) | 0·91 | |

| TICS-M, maximum score of 39‖** | 439 | 12·4 (12·3) | 13·2 (12·1) | −0·87 (−2·63 to 0·90) | 0·34 | 551 | 13·5 (12·3) | 13·7 (11·8) | 0·06 (−1·50 to 1·63) | 0·94 | |

| ZDS, maximum score of 100‖** | 499 | 67·3 (29·7) | 66·0 (29·1) | 1·38 (−2·87 to 5·63) | 0·52 | 638 | 66·5 (28·8) | 65·1 (28·6) | 0·53 (−3·22 to 4·28) | 0·78 | |

| Global outcome (MWD) | 828 | .. | .. | 0·02 (−0·06 to 0·10) | 0·62 | 1102 | .. | .. | 0·00 (−0·06 to 0·07) | 0·92 | |

| Home time, days‡ | 682 | 55·8 (49·2) | 55·5 (46·8) | −0·30 (−6·14 to 5·54) | 0·92 | 903 | 63·5 (48·9) | 63·7 (46·9) | 2·18 (−2·81 to 7·16) | 0·39 | |

Data are n (%), mean (SD), and median (IQR), unless otherwise stated. GTN=glyceryl trinitrate. acOR=adjusted common odds ratio. aOR=adjusted odds ratio. aDIM=adjusted difference in means. aHR=adjusted hazard ratio. mRS=modified Rankin scale. NIHSS=National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. GSC=Glasgow Coma Scale. FAST=face-arm-speech-time test (calculated from NIHSS). OCSP=Oxford Community Stroke Project. TACS=total anterior circulation syndrome (in ischaemic stroke and intracerebral haemorrhage). EQ-5D-HSUV=Euro-Quality of life-5 Dimensions health status utility value. TICS-M=modified telephone interview cognition scale. ZDS=Zung depression scale. MWD=Mann-Whitney difference. EQ-VAS=Euro-Quality of life-Visual Analogue Scale. t-MMSE=telephone mini-mental state examination.

Patients with confirmed stroke or transient ischaemic attack (modified intention-to-treat population).

All patients (intention-to-treat population).

Neurological deterioration from hospital admission: NIHSS ≥4 points or ≥2 point increase in any domain.

Clinical.

Disposition: home (score of 1), institution or in hospital (score of 2), died (score of 3) by day 90.

Death scored as: Barthel Index −5, verbal fluency (animal naming) −1, EQ-VAS −1, home time −1, t-MMSE −1, TICS-M −1, EQ-5D-HSUV 0, GCS 2, mRS 6, NIHSS 43, ZDS 102·5.

Incomplete TICS-M and ZDS due to inability by participants with severe stroke to respond to questions.

Vital status was available in 1122 (98%) participants and mRS in 1102 (96%; figure 1); we found no differential loss to follow-up or withdrawals between the treatment groups. Masking was maintained with participants unable to identify which medication they had received (appendix).

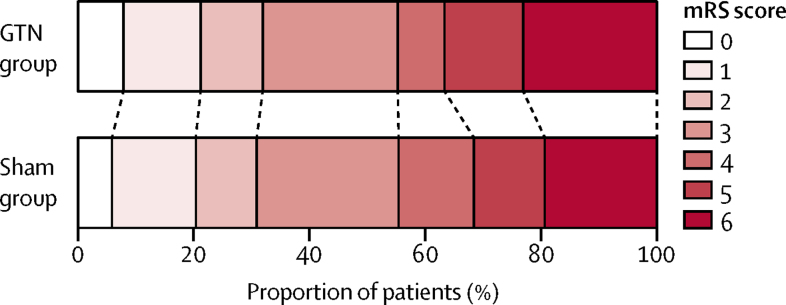

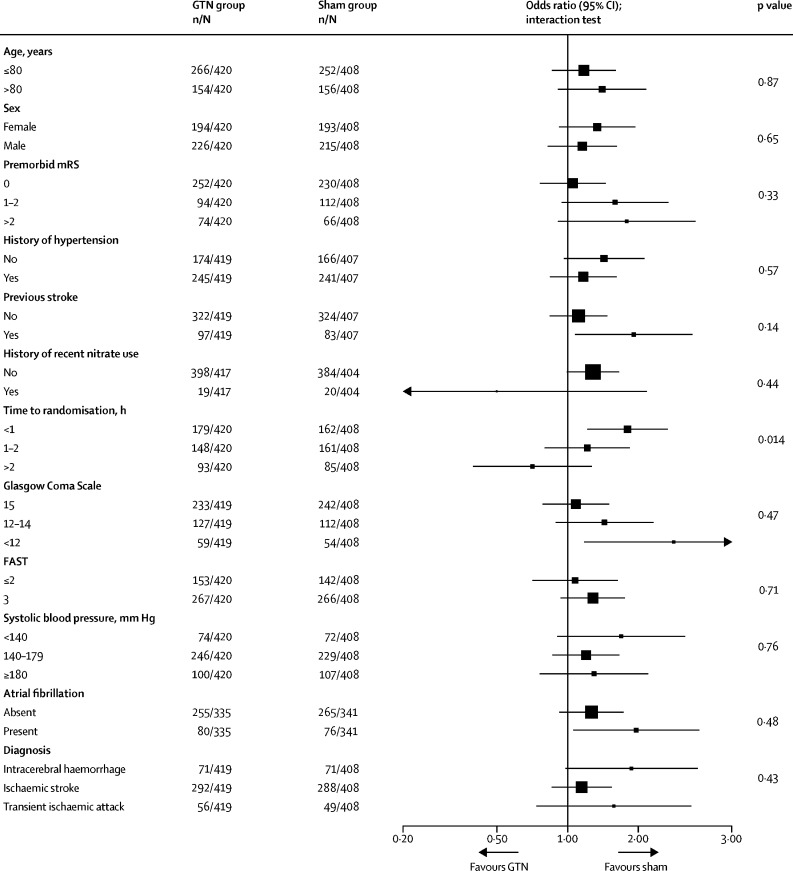

In the target disease population of cohort 1 (confirmed stroke and transient ischaemic attack), we found no strong evidence of an effect of GTN on functional outcome at 90 days compared with sham (mRS 3 [IQR 2–5] in the GTN group vs 3 [2–5] in the sham group; adjusted common OR [acOR] 1·25 [95 % CI 0·97–1·60]; p=0·083; table 2; figure 2), and the acOR of 1·25 suggests a tendency in favour of sham treatment. In sensitivity analyses, no difference was found in mRS when compared as mean difference, proportions with poor outcome (mRS >2), mRS in the per-protocol population, or when data were imputed for participants without a recorded mRS at day 90 (table 2). A significant interaction of the effect of GTN on mRS was present for time to randomisation, with a negative effect of GTN apparent in participants recruited within 1 h of symptom onset (figure 3); no other significant effect modification by subgroups was detected. Post-hoc assessment of the treatment effect on mRS in clinically relevant subgroups defined on or after admission to hospital (ie, potentially affected by treatment) showed a significant interaction with a worse outcome in patients with a more severe stroke on admission to hospital (post-treatment NIHSS >12; appendix).

Figure 2.

Distribution of mRS score at day 90 for GTN versus sham in cohort 1

Cohort 1 includes patients with confirmed stroke or transient ischaemic stroke (modified intention to treat). Comparison by ordinal logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, premorbid mRS, FAST score, pretreatment systolic blood pressure, index event (intracerebral haemorrhage, ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, mimic), and time to randomisation. GTN=glyceryl trinitrate. mRS=modified Rankin Scale. FAST=face-arm-speech-time test.

Figure 3.

Effect of GTN versus sham on mRS score at day 90 in cohort 1 prespecified subgroups defined before treatment and admission to hospital

Comparison by ordinal logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, premorbid mRS, FAST, pretreatment systolic blood pressure, index event (intracerebral haemorrhage, ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, mimic), time to randomisation, and reperfusion therapy (alteplase, intra-arterial therapy, none). GTN=glyceryl trinitrate. mRS=modified Rankin Scale. FAST=face-arm-speech-time test.

When assessed in the target disease population (cohort 1), mRS did not differ between GTN and sham groups in participants with stroke (3 [IQR 2–6] in the GTN group vs 3 [2–5] in the sham group; acOR 1·26 [95% CI 0·96–1·64]; p=0·095; n=722), ischaemic stroke (3 [2–5] in GTN and sham groups; 1·15 [0·85–1·54]; p=0·36; n=580), or transient ischaemic attack (3 [1–3] in the GTN group vs 2 [1–3] in the sham group; 1·57 [0·74–3·35]; p=0·24; n=105). However, GTN was associated with a non-significantly worse outcome in patients with a final diagnosis of intracerebral haemorrhage (5 [4–6] in the GTN group vs 5 [3–5] in the sham group; 1·87 [0·98–3·57]; p=0·057; n=142; appendix).

Analysis of the ITT population (cohort 2) also showed that mRS did not differ between GTN and sham groups in the primary analysis (3 [IQR 2–5] for both groups; acOR 1·04 [95% CI 0·84–1·29]; p=0·69; table 2; appendix) or in any sensitivity analysis (data not shown). In predefined subgroups, a significant interaction was seen by final diagnosis (appendix); in contrast to the effect of GTN in stroke or transient ischaemic attack (see above), GTN appeared to be associated with an improved mRS in patients with a mimic (non-stroke or transient ischaemic attack mimic; 3 [1–4] for both groups; 0·54 [0·34–0·85]; p=0·0081); in a post-hoc analysis, this positive finding was not localised to any particular type of mimic (data not shown).

GCS at admission to hospital was 0·4 points lower in the GTN group. Because of this difference, we performed a post-hoc sensitivity analysis adding baseline GCS to the statistical model for the primary outcome in cohort 1, which had minimal effect on the result (OR 1·22 [95% CI 0·95–1·56]). Otherwise, we found no evidence of any other differences between GTN and sham groups in secondary outcomes in cohort 1 (table 2; appendix). A global analysis encompassing the primary outcome and prespecified secondary outcomes showed no difference (table 2; appendix).

Compared with the sham group, patients with an ischaemic stroke in the GTN group were less likely to have thrombectomy (appendix); conversely, patients in the GTN group were more likely to be ventilated in an intensive care unit. Use of other standard stroke treatments did not differ between the randomised treatment groups. No differences were found between GTN and sham groups in secondary outcomes at day 90 (table 2).

The proportion of deaths at day 4 did not differ between GTN and sham groups either in the target disease population (cohort 1) or in the full ITT population (cohort 2; table 2). Similarly, the proportion of deaths by day 90 did not differ between groups in cohort 1 (adjusted HR [aHR] 1·24 [95% CI 0·91–1·68]; p=0·17; table 2; appendix) or in cohort 2. The most common causes of death were progression or recurrence of the index stroke and pneumonia. A slight excess of headaches by day 4 was apparent in the GTN group. The number of participants experiencing one or more serious adverse events did not differ between the GTN and sham groups (188 [33%] patients vs 170 [29%]; p=0·16; appendix) although cardiovascular serious adverse events were more common in the GTN group (29% [5%] vs 16 [3%]). No suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions occurred.

The on-treatment hospital-based imaging findings for participants with a final diagnosis of stroke or transient ischaemic attack are shown in the appendix. In ischaemic stroke, scanning was done on admission at 2·2 h and on day 2 at 27·7 h after onset of stroke or transient ischaemic attack. No differences were found between GTN and sham groups in respect of infarct size, swelling, or mass effect on plain brain CT. Patients receiving intravenous thrombolysis were non-significantly less likely to have haemorrhagic transformation with GTN than with sham (5 [3%] vs 11 [8%]; OR 0·38 [95% CI 0·13–1·13]; p=0·082). For participants with intracerebral haemorrhage, scanning was done on admission at an average of 2·3 h and 28·9 h after onset of stroke or transient ischaemic attack (appendix). GTN was associated with larger haematoma than sham (1·95 [1·07–3·58]; p=0·030) and more mass effect (2·42 [1·26–4·68]; p=0·0083) at hospital admission.

Addition of the results for participants with confirmed stroke or transient ischaemic attack in cohort 1 (target disease population) in RIGHT-2 to the positive published Cochrane review14 for hyperacute administration of GTN, resulted in neutral effects for end-of-trial death or dependency (mRS >2; OR 0·80 [95% CI 0·59–1·10]; p=0·17; heterogeneity I2=16%; p=0·30) and death (0·52 [0·16–1·72]; p=0·28; I2=86%; p=0·0007; appendix). Heterogeneity between trial results was apparent for death, emphasising the difference between the results for RIGHT-2 versus the earlier RIGHT10 and ENOS-early11, 12 trials.

Discussion

RIGHT-2 recruited 1149 patients who were taken to 54 hospitals; 516 paramedics from 184 ambulance stations within eight UK ambulance services performed screening, obtained consent, and delivered treatment and early follow-up measurement. Consent or proxy consent was obtained from patients, relatives, carers, or friends of the patient, or by the recruiting paramedic. Treatment was commenced very early, and faster than in hospital-based trials, with 38% of patients treated in the first 60 min after stroke onset (the so-called golden hour).25 Hence, we have shown that it is feasible to perform a large multicentre, paramedic-delivered, ambulance-based trial in patients with suspected stroke in the UK. Having shown feasibility, we compared the effect of GTN with sham and found that treatment with GTN did not affect functional outcome in patients with the target diagnosis of confirmed stroke or transient ischaemic attack or in the overall recruited population.

The results shown for GTN differ from those reported in a previous small phase 2, ambulance-based trial (RIGHT,10 with recruitment <4 h of onset) and a subgroup of a large phase 3 trial (ENOS,12 recruitment <6 h of onset). These discrepant results have several potential explanations. First, GTN might simply be ineffective in very early stroke, as suggested by the absence of any effect of GTN on multiple secondary outcomes and a global outcome and by neutral meta-analyses when combining ENOS-early, RIGHT, and RIGHT-2. Second, the discrepant findings might be due to chance rather than any true positive or negative effect of GTN. Chance could also account for the observation that GTN appeared to be beneficial in participants with a final diagnosis of non-stroke or transient ischaemic attack mimic irrespective of the underlying mimic diagnosis. Third, the difference between RIGHT-2 and ENOS-early or RIGHT might be real, due to intrinsic differences in their design: in RIGHT-2, we randomly assigned patients far earlier (median 71 min) than in RIGHT and ENOS-early combined (median 257 min) and so will have recruited a different cohort of patients. Compared with these earlier trials, participants in RIGHT-2 were older and more likely to have premorbid dependency, diabetes, previous stroke, and ischaemic heart disease; and, among the patients with intracerebral haemorrhage, they were more likely to still be in a period of haematoma expansion. All these factors might have contributed to different effects of GTN on functional outcome, as was apparent for reductions in systolic blood pressure (6·2 mm Hg in RIGHT-2 vs 9·4 mm Hg in ENOS-early).11, 12 Finally, studies showing a positive effect of GTN within 6 h used a 7-day treatment period and had higher rates of adherence, so it is conceivable that GTN was not given for long enough in RIGHT-2.

Although RIGHT-2 was a neutral trial, GTN was associated with a tendency for a worse functional outcome in patients with confirmed stroke or transient ischaemic attack (cohort 1), with a 95% CI covering a range from a clinically insignificant benefit (OR 0·97) to a clinically significant hazard (OR 1·60). This tendency towards harm was particularly seen in patients with intracerebral haemorrhage, very early stroke (<1 h), and severe stroke (GCS <12, NIHSS >12). Further, the imaging findings support a negative effect of GTN in ultra-acute intracerebral haemorrhage with larger haematoma, and more haematoma expansion, perihaematoma oedema, mass effect, and midline shift. There are several explanations for the potential hazard in intracerebral haemorrhage, which has a higher base rate of ultra-early neurological deterioration than ischaemic stroke,26 and these are given in decreasing order of likelihood. First, the earliest stage in haemostasis is vasoconstriction and GTN might prevent this protective response and so lead to very early haematoma expansion. Second, although we did not identify antiplatelet effects with GTN in a previous study of patients with stroke,7 others have reported this response in laboratory experiments,27 and GTN could therefore have amplified haematoma expansion in intracerebral haemorrhage thereby countering any effects of lowering blood pressure. Third, venodilators, such as sodium nitroprusside and GTN, have been shown experimentally and clinically to raise intracerebral pressure and reduce cerebral blood flow, particularly if intracerebral pressure is already elevated.28, 29 Reduced blood flow might then induce peri-haematoma ischaemia. Although pilot work did not find a negative effect of GTN on cerebral blood flow or cerebral perfusion pressure in patients in hospital with recent stroke,8, 9, 30 these studies were not in the ultra-acute period after stroke and were mainly in ischaemic stroke, and so they might not be directly relevant to the RIGHT-2 population. Last, GTN can stimulate the formation of reactive oxygen species such as superoxide (O2−) and peroxynitrite (OONO−), which might attenuate vasodilation and increase the potential for cellular damage.31

Preclinical studies of neuroprotective and collateral enhancement therapy in ischaemic stroke suggest that treatment is most effective when administered rapidly after symptom onset. Ideally treatment would be started before hospital admission to reduce stroke-to-needle time.32 The US FAST-MAG trial15 successfully randomly assigned 1700 participants in ambulances to receive intravenous magnesium or placebo within 2 h of symptom start and took them to 36 hospitals. RIGHT-2 extends these observations showing that a large stroke ambulance trial can be performed embedded in the UK national health service involving multiple ambulance services and hospitals. Hence, other interventions that do not require previous CT scanning could be tested in this environment in the future. By extrapolation, paramedics will also be able to administer such interventions routinely in the ambulance once they have been shown to be effective in one or more types of stroke and safe in mimics.

The present trial has several strengths, including the large sample size, generalisability due to wide inclusion criteria, central concealment of treatment assignment, excellent adherence to the first dose of allocated treatment, prospective collection of multiple functional outcomes and safety measures such as hypotension and hypertension, near-complete follow-up (96% of patients had their primary outcome recorded), and central masked assessment of outcomes at day 90. Patients received modern care, including stroke unit admission, thrombolysis, thrombectomy, and hemicraniectomy.

Several limitations are also present. First, GTN was administered in a single-blind design since no commercial sources of placebo patches are available. Despite this design, patient-blinding at day 90 was successful through use of a near identical sham patch, and both GTN and sham patches were unmarked; placement of a gauze dressing over the patch8, 9, 10 gave additional blinding. Further, outcomes measured at day 90 were assessed centrally by trained staff masked to treatment assignment who were not involved in hospital care of enrolled patients. Second, many patients did not receive randomised treatment for the intended minimum period of 2 days, and even fewer for the full 4 days; hence, participants might have received inadequate treatment. Third, the difference in blood pressure between GTN and sham was small and less than that seen in the large ENOS trial.11, 12 Although this difference might reflect inaccuracies in blood pressure measurement in the emergency environment of an ambulance and hospital admission, it might also explain the lack of benefit in ischaemic stroke. Fourth, we had to increase the sample size, an unplanned change that was necessary because of the unexpectedly high mimic rate. Last, the trial's wide inclusion criteria recruited a population of patients with stroke that would not normally enter hospital-based trials. In this respect, a group of participants with very severe intracerebral haemorrhage were enrolled who deteriorated rapidly and then died, which could have neutralised any treatment effect.

As far we are aware, RIGHT-2 is the first acute stroke trial to use a hierarchical approach to analysis in which the first analysis in the primary family was performed in the target population, with the potential for a subsequent primary analysis across the entire ITT population. We followed this predefined plan17 since the high mimic rate had the potential to dilute any treatment effect. Although the non-positive result in the target population precluded testing the ITT population, this approach had the advantage that the primary analysis of the study directly addressed the core question of the biological benefit of drug administration in patients with the disease of interest.

In summary, treatment with transdermal GTN administered before hospital did not alter functional outcome in participants with ultra-acute stroke. The signals of potential adverse effect of GTN in intracerebral haemorrhage are not definitive, but suggest the advisability of close safety monitoring in ongoing trials of prehospital GTN in ultra-acute stroke (ISRCTN99503308). Nevertheless, earlier findings in the large ENOS trial, including in intracerebral haemorrhage, suggest that transdermal GTN is safe when administered later in hospital11 and might continue to be used for lowering blood pressure, for example before thrombolysis. Finally, the study shows that large ambulance-based studies are feasible in the UK and, by extrapolation and taking into account the FAST-MAG trial,15 in most developed countries.

Data sharing

Individual participant data will be shared with the Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive (VISTA) collaboration. From Jan 1, 2021, the Chief Investigator (with approval from the Trial Steering Committee as necessary) will consider other requests to share individual participant data via email at: right-2@nottingham.ac.uk. We will require a protocol detailing hypothesis, aims, analyses, and intended tables and figures. Where possible, we will perform the analyses; alternatively, de-identified data and a data dictionary will be supplied for the necessary variables for remote analysis. Any sharing will be subject to a signed data access agreement. Ultimately, the data will be published.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in this trial and their relatives, the clinical and research teams of the various ambulance services and hospitals, and the paramedics who recruited and treated the patients. We acknowledge that the support of the English National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network, the coordination between multiple ambulance services and hospitals, and the large recruitment would not have been possible without NIHR network support. This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation [grant number CS/14/4/30972].

Contributors

The trial was conceived and designed by the grant applicants, and they wrote the protocol. The trial was overseen by a Trial Steering Committee (which included three independent members and a patient-public representative), and advice was given by an International Advisory Committee. The day-to-day conduct of the trial was run by a Trial Management Committee, which was based at the Stroke Trials Unit in Nottingham, UK. Study data were collected and quality-assured by the RIGHT-2 Coordinating Centre in Nottingham. Analysis, interpretation, and report writing were performed independently of the funder and sponsor. The corresponding author wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and this was edited and commented on by the Writing Committee, all of whom approved the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. PMB was chief investigator, a grant applicant, participated in the Steering Committee, collected, verified, and analysed data and drafted this report, and is project guarantor. PS was trial statistician, involved in the design of the trial, participated in the Steering Committee, wrote the first draft of the statistical analysis plan, and verified and analysed data. CSA was an international adviser who provided guidance on trial delivery and interpretation. SA adjudicated serious adverse events. JPA was the trial physician supporting the chief investigator and trial delivery. EB was an international adviser who provided guidance on trial delivery and interpretation. LC adjudicated brain scans. MD was the national paramedic lead coordinating ambulance service trial delivery. TJE was a grant applicant, participated in the Steering Committee, and advised on trial delivery. PJG was statistician to the Data Monitoring Committee. DH was senior trial manager and chaired the Management Committee. LH programmed and supported the web interface and trial databases. TH wrote the approval documents and information sheets and provided statistical advice. KK performed brain scan measurements in participants with intracerebral haemorrhage. GM adjudicated brain scans. AAM was a statistician, grant applicant, and participated in the Steering Committee. KM was an independent member of the Steering Committee. SJP was an international adviser who provided guidance on trial delivery and interpretation. SP was statistician, grant applicant, and participated in the Steering Committee. JP was a grant applicant, participated in the Steering Committee, and advised on trial delivery. CIP was a grant applicant, participated in the Steering Committee, and advised on trial delivery by ambulance services. MR adjudicated serious adverse events. TGR was a grant applicant, participated in the Steering Committee, and advised on trial delivery. CR was a grant applicant, participated in the Steering Committee, and advised on trial delivery. PMR was a national adviser who provided guidance on trial delivery and interpretation. ECS was an international adviser who provided guidance on trial delivery and interpretation. NSa and JLS were international advisers who provided guidance on ambulance trial delivery and interpretation. AS was sponsor. ANS was a grant applicant, participated in the Steering Committee, and advised on trial delivery by ambulance services. JMW was a grant applicant, participated in the Steering Committee, and led adjudication of brain scans. LJW was trial statistician, involved in the design of the trial, participated in the Steering Committee, and verified and analysed data. GV was independent chair of the Steering Committee. NSp was deputy chief investigator, a grant applicant, and participated in the Steering Committee. All members of the Writing Committee commented on the analyses and drafts of this report and have seen and approved the final version of the report.

Writing Committee

Philip M Bath, Polly Scutt, Craig S Anderson, Sandeep Ankolekar, Jason P Appleton, Eivind Berge, Lesley Cala, Mark Dixon, Timothy J England, Peter J Godolphin, Diane Havard, Lee Haywood, Trish Hepburn, Kailash Krishnan, Grant Mair, Alan A Montgomery, Keith Muir, Stephen J Phillips, Stuart Pocock, John Potter, Chris I Price, Marc Randall, Thompson G Robinson, Christine Roffe, Peter M Rothwell, Else C Sandset, Nerses Sanossian, Jeffrey L Saver, Angela Shone, A Niroshan Siriwardena, Joanna M Wardlaw, Lisa J Woodhouse, Graham Venables, Nikola Sprigg.

Declaration of interests

PMB is Stroke Association Professor of Stroke Medicine and is a NIHR Senior Investigator. He reports grants from British Heart Foundation during the conduct of the study; personal fees and other fees from Sanofi, Nestlé, DiaMedica, Moleac, Platelet Solutions, Phagenesis, and ReNeuron, outside the submitted work. CSA reports grants from National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia, grants from Takeda, and personal fees from Takeda, Amgen, and Boehringer Ingelheim outside of the submitted work. JPA was funded in part by the British Heart Foundation during the conduct of the study. TJE, LH, and AAM report grants from British Heart Foundation during the conduct of the study. GM is supported by NHS Lothian Research and Development Office and and reports grants from The Stroke Association, The Royal College of Radiologists. KM reports non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Daiichi Sankyo outside of the submitted work. CIP reports grants from Nottingham University during the conduct of the study. TGR is an NIHR Senior Investigator. ECS reports personal fees from Novartis and Bayer outside of the submitted work. JMW was supported by the SFC SINAPSE Collaboration (www.sinapse.ac.uk) and reports grants from the British Heart Foundation during the conduct of the study. NSp reports grants from British Heart Foundation, during the conduct of the study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

The RIGHT-2 Investigators:

Philip M Bath, Polly Scutt, Craig S Anderson, Jason P Appleton, Evind Berge, Lesley Cala, Mark Dixon, Timothy M England, Peter J Godolphin, Diane Havard, Lee Haywood, Trish Hepburn, Kailash Krishnan, Grant Mair, Alan A Montgomery, Keith Muir, Stephen J Phillips, Stuart Pocock, John Potter, Chris Price, Marc Randall, Thompson G Robinson, Christine Roffe, Peter M Rothwell, Else C Sandset, Nerses Sanossian, Jeffrey L Saver, Angela Shone, A Niroshan Siriwardena, Joanna M Wardlaw, Lisa J Woodhouse, Graham Venables, Nikola Sprigg, Pierre Amarenco, Keith Muir, Shannon Amoils, Malcolm Jarvis, Peter M Rothwell, Peter Sandercock, Kjell Asplund, Colin Baigent, Sandeep Ankolekar, Harriet Howard, Christopher Lysons, Gemma Walker, Hayley Gregory, James Kirby, Jennifer Smithson, Joanne Keeling, Nadia Frowd, Robert Gray, Richard Dooley, Wim Clarke, Patricia Robinson, Zhe Kang Law, Sheila Hodgson, Adam Millington, Eleni Sakka, David Buchanan, Jeb Palmer, D Shaw, H Cobb, R Johnson, T Payne, R Spaight, A Spaight, M A Sajid, A Whileman, E Hall, H Cripps, J Toms, R Gascoyne, S Wright, M Cooper, A Palfreman, A Rajapakse, I Wynter, K Musarrat, A Mistri, C Patel, C Stephens, S Khan, S Patras, M Soliman, A Elmarimi, C Hewitt, E Watson, I Wahishi, J Hindle, L Perkin, M Wills, S Arif, S Leach, S Butler, D O'Kane, C Smith, J O'Callaghan, W Sunman, A Buck, B Jackson, C Richardson, G Wilkes, J Clarke, L Ryan, O Matias, D Mangion, A Hardwick, C Constantin, I Thomas, K Netherton, S Markova, A Hedstrom, B Rushton, C Hyde, J Scott, M Blair, M Maddula, R Donnelly, S Keane, S Johnson, H McKenzie, A Banerjee, D Hutchinson, H Goodhand, J Hill, K Mellows, M Cheeseman, V McTaggart, T Foster, L Prothero, P Saksena, A O'Kelly, H Wyllie, C Hacon, H Nutt, J North, K Goffin, J Potter, A Wiltshire, G Ravenhill, K Metcalf, L Ford, M Langley, W Davison, S Subramonian, F Magezi, I Obi, N Temple, N Butterworth-Cowin, P Oqwusu-Agyei, A F M Azim, A Nicolson, J Imam, J White, L Wood, R Fothergill, N Thompson, J Lazarus, H Werts, L Sztriha, C Ho, E McKenzie, E Owoyele, J Lim, J Aeron-Thomas, M Dockey, N Sylvester, P Rao, B M Bloom, E Erumere, G Norman, I Skene, L Cuenoud, L Howaniec, O Boulton, P Daboo, R Michael, S Al-Saadi, T Harrison, H Syed, L Argandona, S Amiani, R Perry, A Ashton, A Banaras, C Hogan, C Watchurst, E Elliott, N Francia, N Oji, R Erande, S Obarey, S Feerick, S Tshuma, E England, H Pocock, K Poole, S Manchanda, I Burn, S Dayal, K McNee, M Robinson, R Hancock, A South, C Holmes, A Steele, L B Guthrie, M Oborn, A Mohd Nor, B Hyams, C Eglinton, D Waugh, E Cann, N Wilmhurst, S Piesley, S Shave, D Dutta, M Obeid, D Ward, J Turfrey, J Glass, K Bowstead, L Hill, P Brown, S Beames, S O'Connell, V Hughes, R Whiting, J Gagg, M Hussain, M Harvey, D Karunatilake, B Pusuluri, A Witcher, C Pawley, J Allen, J Foot, J Rowe, C Lane, S Ragab, B Wadams, J Dube, B Jupp, A Ljubez, C Bagnall, G Hann, L Tucker, M Kelton, S Orr, F Harrington, A James, A Lydon, G Courtauld, K Bond, L Lucas, T Nisbett, J Kubie, A Bowring, G Jennings, K Thorpe, N Mason, S Keenan, L Gbadomishi, D Howcroft, H Newton, J Choulerton, J Avis, L Shaw, P Paterson, P Kaye, S Hierons, S Lucas, P Clatworthy, B Faulkner, L Rannigan, R Worner, B Bhaskaran, A Saulat, H Bearne, J Garfield-Smith, K Horan, P Fitzell, S Szabo, M Haley, D Simmons, D Cotterill, G Saunders, H Dymond, S Beech, K Rashed, A Tanate, C Buckley, D Wood, L Matthews, S Board, T Pitt-Kirby, N Rees, C Convery, P Jones, C Bryant, H Tench, M Dixon, R Loosley, S Coetzee, S Jones, T Sims, M Krishnan, C Davies, L Quinn, L Connor, M Wani, S Storton, S Treadwell, T Anjum, C Somashekar, A Chandler, C Triscott, L Bevan, M Sander, S Buckle, W Sayed, K Andrews, L Hughes, R Hughes, M Ward, A Pretty, A Rosser, B Davidson, G Price, I Gunson, J Lumley-Holmes, J Miller, M Larden, M Jhamat, P Horwood, R Boldy, C Jenkins, F Price, M Harrison, T Martin, N Ahmad, A Willberry, A Stevens, K Fotherby, A Barry, A Remegoso, F Alipio, H Maquire, J Hiden, K Finney, R Varquez, S Ispoglou, A Hayes, D Gull, R Evans, E Epstein, S Hurdowar, J Crossley, J Miles, K Hird, R Pilbery, C Patterson, H Ramadan, K Stewart, O Quinn, R Bellfield, S Macquire, W Gaba, A Nair, A Wilson, C Hawksworth, I Alam, J Greig, M Robinson, P Gomes, P Rana, Z Ahmed, P Anderston, A Neal, D Walstow, R Fong, S Brotheridge, A Bwalya, A Gillespie, C Midgley, C Hare, H Lyon, L Stephenson, M Broome, R Worton, S Jackson, R Rayessa, A Abdul-Hamid, C Naylor, E Clarkson, A Hassan, D Waugh, E Veraque, L Finch, L Makawa, M Carpenter, P Datta, A Needle, L Jackson, H J Brooke, J Ball, T Lowry, S Punnoose, R Walker, V Murray, A Ali, C Kamara, C Doyle, E Richards, J Howe, K Dakin, K Harkness, R Lindert, P Wanklyn, P Willcoxson, P Clark-Brown, and R Mir

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Bath PM, Appleton JP, Krishnan K, Sprigg N. Blood pressure in acute stroke: to treat or not to treat: that is still the question. Stroke. 2018;49:1784–1790. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party . 5th edn. Royal College of Physicians; London: 2016. National clinical guideline for stroke. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willmot M, Gray L, Gibson C, Murphy S, Bath PMW. A systematic review of nitric oxide donors and L-arginine in experimental stroke; effects on infarct size and cerebral blood flow. Nitric Oxide. 2005;12:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maniskas ME, Roberts JM, Trueman R. Intra-arterial nitroglycerin as directed acute treatment in experimental ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;10:29–33. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferlito S, Gallina M, Pitari GM, Bianchi A. Nitric oxide plasma levels in patients with chronic and acute cerebrovascular disorders. Panminerva Med. 1998;40:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rashid PA, Whitehurst A, Lawson N, Bath PMW. Plasma nitric oxide (nitrate/nitrite) levels in acute stroke and their relationship with severity and outcome. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;12:82–87. doi: 10.1053/jscd.2003.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bath PMW, Pathansali R, Iddenden R, Bath FJ. The effect of transdermal glyceryl trinitrate, a nitric oxide donor, on blood pressure and platelet function in acute stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001;11:265–272. doi: 10.1159/000047649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rashid P, Weaver C, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath F, Fletcher S, Bath P. The effects of transdermal glyceryl trinitrate, a nitric oxide donor, on blood pressure, cerebral and cardiac hemodynamics, and plasma nitric oxide levels in acute stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;12:143–151. doi: 10.1016/S1052-3057(03)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willmot M, Ghadami A, Whysall B, Clarke W, Wardlaw J, Bath PMW. Transdermal glyceryl trinitrate lowers blood pressure and maintains cerebral blood flow in recent stroke. Hypertension. 2006;47:1209–1215. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000223024.02939.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ankolekar S, Fuller M, Cross I. Feasibility of an ambulance-based stroke trial, and safety of glyceryl trinitrate in ultra-acute stroke the rapid intervention with glyceryl trinitrate in Hypertensive Stroke Trial (RIGHT, ISRCTN66434824) Stroke. 2013;44:3120–3128. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bath PM, Woodhouse L, Scutt P. Efficacy of nitric oxide, with or without continuing antihypertensive treatment, for management of high blood pressure in acute stroke (ENOS): a partial-factorial randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:617–628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodhouse L, Scutt P, Krishnan K. Effect of hyperacute administration (within 6 hours) of transdermal glyceryl trinitrate, a nitric oxide donor, on outcome after stroke: subgroup analysis of the Efficacy of Nitric Oxide in Stroke (ENOS) Trial. Stroke. 2015;46:3194–3201. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bath P, Woodhouse L, Krishnan K. Effect of treatment delay, stroke type, and thrombolysis on the effect of glyceryl trinitrate, a nitric oxide donor, on outcome after acute stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient from randomised trials. Stroke Res Treat. 2016;2016:9706720. doi: 10.1155/2016/9706720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bath PM, Krishnan K, Appleton JP. Nitric oxide donors (nitrates), L-arginine, or nitric oxide synthase inhibitors for acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000398.pub2. CD000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saver J, Starkman S, Eckstein M. Prehospital use of magnesium sulfate as neuroprotection in acute stroke. N Engl J Medicine. 2015;372:528–536. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Appleton JP, Scutt P, Dixon M. Ambulance-delivered transdermal glyceryl trinitrate versus sham for ultra-acute stroke: rationale, design and protocol for the Rapid Intervention with Glyceryl trinitrate in Hypertensive stroke Trial-2 (RIGHT-2) trial (ISRCTN26986053) Int J Stroke. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1747493017724627. published online Jan 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scutt P, Appleton JP, Dixon M. Statistical analysis plan for the ‘Rapid Intervention with Glyceryl trinitrate in Hypertensive stroke Trial-2 (RIGHT-2)’. Eur Stroke J. 2018;3:193–196. doi: 10.1177/2396987318756696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bath PM, Scutt P, Appleton JP. Baseline characteristics of the 1149 patients recruited into the Rapid Intervention with Glyceryl trinitrate in Hypertensive stroke Trial-2 (RIGHT-2) randomised controlled trial. Int J Stroke. 2018 doi: 10.1177/1747493018816451. published online Nov 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lees KR, Bath PMW, Schellinger PD. Contemporary outcome measures in acute stroke research: choice of primary outcome measure. Stroke. 2012;43:1163–1170. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.641423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruno A, Shah N, Lin C. Improving modified rankin scale assessment with a simplified questionnaire. Stroke. 2010;41:1048–1050. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.571562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bath PM, Lees KR, Schellinger PD. Statistical analysis of the primary outcome in acute stroke trials. Stroke. 2012;43:1171–1178. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.641456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnan K, Mukhtar SF, Lingard J. Performance characteristics of methods for quantifying spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage: data from the Efficacy of Nitric Oxide in Stroke (ENOS) trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:1258–1266. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray LJ, Bath PM, Collier T. Should stroke trials adjust functional outcome for baseline prognostic factors? Stroke. 2009;40:888–894. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.519207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lachin J. Applications of the Wei-Lachin multivariate one-sided test for multiple outcomes on possibly different scales. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saver J, Smith E, Fonarow G. The “golden hour” and acute brain ischemia; presenting features and lytic therapy in >30000 patients arriving within 60 minutes of stroke onset. Stroke. 2010;41:1431–1439. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shkirkova K, Saver JL, Starkman S. Frequency, predictors, and outcomes of prehospital and early postarrival neurological deterioration in acute stroke: exploratory analysis of the FAST-MAG randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1364–1374. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Byrne S, Shirodaria C, Millar T, Stevens C, Blake D, Benjamin N. Inhibition of platelet aggregation with glyceryl trinitrate and xanthine oxidoreductase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:326–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartmann A, Buttinger C, Rommel T, Czernicki Z, Trtinjiak F. Alteration of intracranial pressure, cerebral blood flow, autoregulation and carbondioxide-reactivity by hypotensive agents in baboons with intracranial hypertension. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg) 1989;32:37–43. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1053998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner JM, Powell D, Gibson RM, McDowall DG. Intracranial pressure changes in neurosurgical patients during hypotension induced with sodium nitroprusside or trimetaphan. Br J Anaethesiol. 1977;49:419–420. doi: 10.1093/bja/49.5.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kate M, Asdaghi N, Gioia LC. Blood pressure reduction in hypertensive acute ischemic stroke patients does not affect cerebral blood flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018 doi: 10.1177/0271678X18774708. published online May 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Münzel T, Daiber A. Inorganic nitrite and nitrate in cardiovascular therapy: a better alternative to organic nitrates as nitric oxide donors? Vascul Pharmacol. 2018;102:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Audebert HJ, Saver JL, Starkman S, Lees KR, Endres M. Prehospital stroke care: new prospects for treatment and clinical research. Neurology. 2013;81:501–508. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829e0fdd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Individual participant data will be shared with the Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive (VISTA) collaboration. From Jan 1, 2021, the Chief Investigator (with approval from the Trial Steering Committee as necessary) will consider other requests to share individual participant data via email at: right-2@nottingham.ac.uk. We will require a protocol detailing hypothesis, aims, analyses, and intended tables and figures. Where possible, we will perform the analyses; alternatively, de-identified data and a data dictionary will be supplied for the necessary variables for remote analysis. Any sharing will be subject to a signed data access agreement. Ultimately, the data will be published.