Foodborne pathogen surveillance in the United States is transitioning from strain identification using restriction digest technology (pulsed-field gel electrophoresis [PFGE]) to shotgun sequencing of the entire genome (whole-genome sequencing [WGS]). WGS requires a new suite of analysis tools, some of which have long histories in academia but are new to the field of public health and regulatory decision making.

KEYWORDS: Listeria, Salmonella, validation, WGS, bioinformatic pipeline, foodborne pathogen, outbreak, phylogeny

ABSTRACT

Foodborne pathogen surveillance in the United States is transitioning from strain identification using restriction digest technology (pulsed-field gel electrophoresis [PFGE]) to shotgun sequencing of the entire genome (whole-genome sequencing [WGS]). WGS requires a new suite of analysis tools, some of which have long histories in academia but are new to the field of public health and regulatory decision making. Although the general workflow is fairly standard for collecting and analyzing WGS data for disease surveillance, there are a number of differences in how the data are collected and analyzed across public health agencies, both nationally and internationally. This impedes collaborative public health efforts, so national and international efforts are underway to enable direct comparison of these different analysis methods. Ultimately, the harmonization efforts will allow the (mutually trusted and understood) production and analysis of WGS data by labs and agencies worldwide, thus improving outbreak response capabilities globally. This review provides a historical perspective on the use of WGS for pathogen tracking and summarizes the efforts underway to ensure the major steps in phylogenomic pipelines used for pathogen disease surveillance can be readily validated. The tools for doing this will ensure that the results produced are sound, reproducible, and comparable across different analytic approaches.

INTRODUCTION

PHYLOGENIES AND THE HISTORY OF MOLECULAR EPIDEMIOLOGY

Phylogenetics is the study of the evolutionary relationships among individuals or groups of organisms, as inferred through characters drawn from heritable traits. Molecular phylogenetics often uses the four DNA bases as characters to infer a phylogenetic tree, or phylogeny. Collecting the same, or homologous, DNA characters across a set of individuals became more accessible in the 1980s when DNA sequencing technology became commonly used in academic labs. Applications of molecular phylogenies usually focus on species-level relationships and deeper “Tree of Life” questions. However, the clinical potential of phylogenetics was realized in 1992 when a molecular phylogeny was used to trace the source of a localized HIV outbreak back to a dentist’s office (1). This was the first time a phylogeny was used to identify the source of an outbreak. In 1995 a more formal manuscript described the application of phylogenetics to disease tracking (2): random mutations accumulate in the genomes of pathogens as they replicate within and between hosts, leaving molecular signatures that track the history of transmission events. At any point in time, a snapshot of pathogen DNA gathered from infected individuals can be analyzed to reconstruct the history of those transmission events. This evolutionary history, or phylogeny, can provide information about the origin of disease outbreaks, including whether new strains are entering the population, and can help construct a contact network between infected individuals, such as the HIV-infected dentist in the previous example.

Coordinated disease surveillance for pathogens in the United States started in the late 1980s (3) to foster communication between hospitals, local public health labs, and federal labs, each of which had been tracking diseases only within their respective jurisdiction. Several surveillance networks were established for various diseases: PulseNet for foodborne pathogens (4), FluNet for influenza (5), and the HIV surveillance system for HIV/AIDS (6). The initial application of molecular phylogenetics to pathogen transmission focused on viruses, which have small and rapidly evolving genomes. Sequencing short segments of those genomes was feasible using Sanger technology (7, 8) and captured enough genetic variation for phylogenetic discrimination. These projects typically addressed a specific question or hypothesis, and the results were disseminated through scientific publications. These early academic studies revealed the potential of using phylogenetics for real-time surveillance, whereby collected pathogens could be analyzed immediately, allowing public health organizations to respond more rapidly to the threat of disease outbreaks.

By the mid-2000s, people were starting to build the infrastructure to make the potential into actionable reality. Several projects were initiated using genomic information for epidemiological applications, including surveillance. Academic and public health officials began collaborating on molecular epidemiology projects: Ghedin and colleagues at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) refined influenza tracking (9), Gifford and colleagues at the UK Health Protection Agency began tracking HIV (10), and a team from the University of Cambridge collaborated with nearby hospitals to track bacterial infections (11). These efforts established important collaborations between academic and applied science, laying the groundwork for expansion that dovetailed improvements in sequencing technology.

Huge improvements in sequencing technology, termed “next-generation sequencing” (NGS), transformed the emerging field of molecular epidemiology in the late 2000s. NGS allowed researchers to quickly and cheaply sequence the entire genomes of pathogens (bacteria, parasites, and some fungi) that had larger genomes (ca. 2 to 20 megabases). NGS also provided increased resolution over previous technologies, like single-locus Sanger approaches or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), by uncovering intricate clonal relationships of strains previously assigned to the same strain group, or subtype. This technology improvement made it possible for public health scientists to concieve of implementing whole-genome sequencing (WGS) for real-time disease surveillance. During the transition from previous technologies like Sanger and PFGE to newer sequencing technologies, several different sequence-based typing approaches were considered alongside WGS, such as narrower targeted sequencing efforts like the 7-gene multilocus sequencing typing (MLST) and others designed to capture specific virulence factors and/or antibiotic resistance genes (12). The increase in sequence data also prompted a reexamination of the current phylogenetic methods being used for analyzing epidemiological data sets, including effects of outgroup choices, identification of disease origins, and dating of common ancestors (13). By 2016, genomic surveillance databases had been established for HIV (14, 15), influenza (16–18), and bacterial foodborne pathogens (19–21). All three projects have publicly available genomic databases, however, only the genomes of foodborne pathogens collected through GenomeTrakr and PulseNet laboratory networks are made available in real-time at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), with analyses publicly available through NCBI’s Pathogen Detection portal (21). Although we are at the early stages, these genomic database efforts reveal the power of utilizing comparative genomics for disease surveillance in public health.

DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analyses are mature technical and scientific methods, each with extensive scientific literature supporting their utility. However, their application to public health requires an extra burdon of rigerous validation in the laboratories where the data are generated, analyzed, and interpreted. This requires that the data and analyses are accurate and reproducible under a strict set of parameters. The remainder of this review will discuss validation efforts for the use of NGS in the public health arena, with a focus on tools developed for the surveillance of bacterial foodborne pathogens.

APPLICATIONS OF NGS TO PUBLIC HEATH

Current NGS technologies for public health include WGS, whole-exome sequencing, transcriptome sequencing, organelle and/or plasmid sequencing, targeted gene or locus sequencing, resistome profiling, and metagenomics. Within public health, the two groups which have been the most prominent adopters of NGS are researchers exploring the human genome and researchers performing disease surveillance. Each group is working to validate their data collection efforts and accompanying analyses.

Application to human and animal medicine.

Hospital labs, federal agencies such as the NIH, and associated principal investigators led much of the early NGS validation effort. The application in these labs is mostly targeted sequencing of the human genome, or of associated tumor genomes. Enormous amounts of data are generated; ideally, those results are used for diagnosis, prognosis, and providing guidance for treating or managing disease. However, although this wealth of data provides the opportunity for detailed analyses of patterns correlations, all of which could make treatment more precise and effective, incorrect conclusions can have calamitous consequences for patients. Therefore, early NGS validation in these labs was critical and resulted in strict guidelines and regulations for NGS clinical use in each setting. The American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) published NGS laboratory standards for data collection (22) and for variant analysis (23). Leading research hospitals, such as Mt. Sinai, validated NGS for clinical applications (24). The National Cancer Institute published a validation approach for an NGS assay used in a precision medicine clinical trial (25). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) followed up with similar guidelines for public health laboratories (26). Significant validation efforts have also been contributed outside the United States, namely, in Australia (27), the United Kingdom (28), and the Netherlands (29). The analysis approaches of clinical WGS data can be extremely diverse, depending on the focus of the labs (cancer, rare genetic diseases, infant genetic screening, etc.), making the validation methods equally as complex. Roy et. al (30) detail the analysis nuances in these approaches and propose 17 general recommendations for validating bioinformatic pipelines environment, most of which are also applicable in nonclinical labs. The major conclusion of these efforts can be summarized as follows: when strict wet-lab standards are in place, the collection of NGS data (NGS itself) is accurate and reproducible. However, the downstream analyses are varied enough such that each must be carefully validated for its respective application.

Application to molecular pathogen disease surveillance.

NGS in the regulatory environment. NGS data for foodborne pathogen surveillance in the United States is collected through two tightly coordinated networks. PulseNet (20) performs WGS on clinical isolates, and GenomeTrakr (19) performs WGS on food and environmental isolates; the WGS data are shared publicly in real-time at the NCBI’s Pathogen Detection website (21). These networks, along with non-U.S. submitters such as Public Health England, have amassed over 300,000 foodborne pathogen genomes as of February 2019, a very rich resource for pathogen surveillance. Genomics for Food Safety (Gen-FS) is a working group in the United States (CDC, 2015), with representatives from the CDC, FDA, USDA, and NCBI. The Gen-FS working groups have worked to standardize quality assurance (QA) measures and accompanying quality control (QC) checks across GenomeTrakr and PulseNet to ensure all WGS data in the Pathogen Detection database meet the Gen-FS minimum quality standards. On the international level coordination is handled through the Globial Microbial Identifier (GMI), which meets annually to address similiar issues on the global scale.

In the regulatory environment there is extra consideration when scientific data are used to make regulatory decisions (e.g., recalls for contaminated foods, injunctions, etc.) since the data and accompanying analyses need to stand up to scrutiny in court. Recent papers highlight this importance; a report produced by the U.S. President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) outlines the required steps necessary to ensure the validity of forensic evidence, including DNA evidence, used in the United States’s legal system (PCAST, 2016). Scientists from food industry (31) and from local public health labs (32) are both taking this issue very seriously with recent publications outlining end-to-end WGS validation pipelines developed within their respective labs.

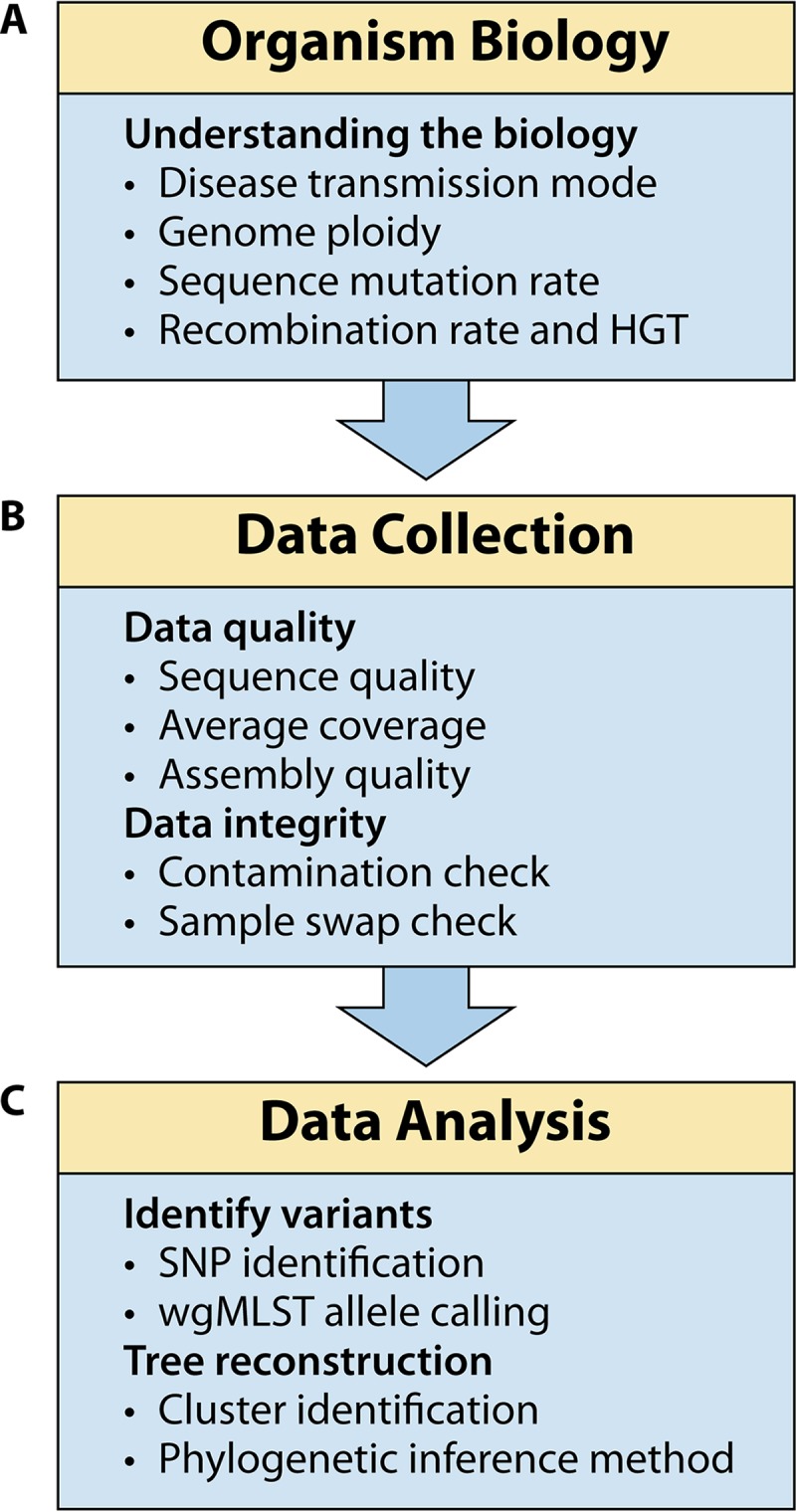

Applications of NGS for pathogen surveillance have been able to build on human clinical validation efforts, focusing instead on areas specific to pathogen sequencing and extending these efforts to include phylogenetic reconstruction of isolates from disease outbreaks and foodborne contamination events. Molecular pathogen disease surveillance starts with understanding the genome biology of the pathogen: its ploidy, rate of sequence mutation, and prevalence of horizontal gene transfer (plasmids, phages, recombination, etc.), and mode of disease transmission (Fig. 1A). The next step is collecting the WGS data and, just as with clinical appliations, strict protocols ensure data quality and data integrity (Fig. 1B). The analysis of WGS data for pathogen disease surveillance, often called phylogenomic analysis, is most easily described in two major steps (Fig. 1C): (i) collection of the relevant variable sites into a character matrix and (ii) phylogenetic reconstruction. Finally, for disease surveillance to be effective, it is critical to have in place a mechanism to archive and distribute the data and analysis results, especially when public health organizations around the world can greatly benefit from open access and potentially contribute as partners to these growing databases.

FIG 1.

NGS phylogenomic workflow for molecular disease surveillance, with critical validation points listed within each module.

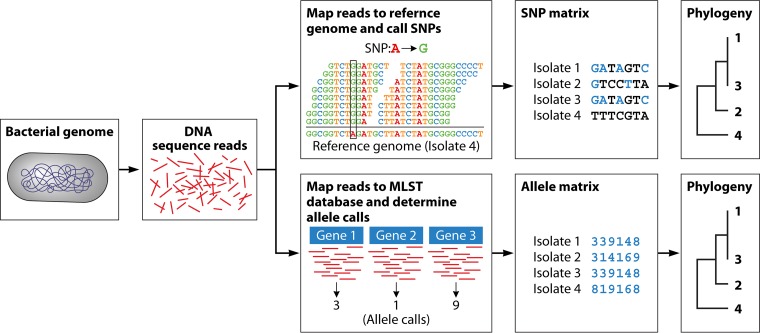

Phylogenomic pipeline approaches, expanded. As mentioned previously, the primary data collection is a similar across many different applications and is therefore fairly straightforward to validate. In contrast, the phylogenomic analyses are built specifically for the application of molecular disease surveillance and therefore require an in-depth look at the current approaches being utilized. After the raw data are collected, there are many different methods and approaches to identify the relevant variable sites, the details of which will be summarized following this section for the two major variant collection approaches (Fig. 2): single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST). There are precedents for using phylogenetic methods to pinpoint origin of disease outbreaks, and notable examples of real-world use are discussed earlier in this review. However, these “variant-only” methods diverge from the traditional phylogenetic approach. Traditionally, phylogenomic analyses used multilocus sequence alignments (not to be confused with cgMLST), in which orthologous genes were determined across the taxa, or isolates, of interest, and then aligned orthologs, or genes with the same evolutionary decent, were concatenated for downstream analyses. This traditional approach can introduce some uncertainty. First, ortholog determination is a hypothesis of shared ancestry, causing systematic errors if the original determination is incorrect. Second, unless a standard core genome is developed, ortholog determination can require many iterations to find the correct number and diversity of loci to include, which can be very time-consuming and delay the prompt traceback of contaminated foods or confirmation of an outbreak. Finally, the full concatenated multigene alignments can be very long (more than 4 Mb in the case of Salmonella genomes), requiring vast computational resources for analysis and result interpretation. Because of these hurdles, assembling a matrix of variant-only sites identified directly from the raw sequences became an attractive goal. The requirement of orthology still holds here for SNP-based approaches and cgMLST, so these new methods must distinguish between true variants and variants introduced by sequence artifacts, assembly error, gene duplication, or horizontal gene transfer (HGT).

FIG 2.

Technical view of the two main types of analysis pipelines implemented for foodborne pathogen surveillance. First, DNA is isolated from the bacteria. Then, it is sequenced using a short-read NGS technology. The short reads can be analyzed in two different ways, each with the same goal of uncovering variants across the genome for use in the final clustering step. For the SNP-based approach, short reads from each isolate are mapped to a reference genome (draft or complete assembly), SNPs are called and filtered, filtered SNPs are written to a FASTA formatted SNP matrix, and then a phylogenetic clustering analysis is performed using that matrix as its input file. For the wgMLST- or cgMLST-based approach, short reads from each isolate are mapped against a species-specific allele database, an allele assignment is made for each gene and added to a FASTA-formated allele matrix, and then a phylogenetic clustering analysis is performed using that matrix as its input file.

SNP analysis. SNP-based approaches have been developed in an attempt to provide a faster, more objective, automated approach to characterize the variation among a set of isolates. In this reference-based approach, NGS reads are mapped against a specified reference genome, and variant sites are extracted and filtered and then concatenated into a sequence matrix (generally called an SNP matrix) containing only sites where SNPs were detected. There are close to a dozen published SNP pipelines being used for various purposes. Evaluating all of them is outside the scope of this review, but the CFSAN SNP Pipeline (33), LyveSet (34), and NCBI’s Pathogen Detection pipeline (21) are examples of SNP pipelines currently being applied for U.S. public health applications. There are also reference-free approaches to SNP calling, in which the variant sites are extracted without comparison to a reference (36, 37). SNP pipelines either end at the variant calling step with the final output file containing the SNP matrix, leaving the choice of phylogenetic inference the user, or include the last step of phylogenetic inference, resulting in a tree as the final output. When comparing different pipelines, it is useful to consider these steps as separate even if they are bundled together.

Phylogenetic inference for SNP matrices. An SNP matrix is consistent with traditional phylogenetic theory in that it is an alignment of orthologous characters (nucleotide variants); however, it diverges from traditional multigene alignments used in molecular phylogenetics in that the resulting character matrixes contains only SNPs that passed the pipeline’s filter criteria, resulting in a matrix containing only sites with variants of a particular type. This makes the phylogenetic analysis much faster because the character matrix contains only hundreds or thousands of sites (not millions), but theoretically it can also introduce the risk of aquisition bias contributed by parameter choices at the multiple steps within an analytical pipeline (i.e., mapping, read filtering, choice of reference genome, and model of evolution) (38). In practice, variant-only data have not been shown to impact tree topologies of shallow evolutionary analyses (38, 39), such as the clonal data sets usually seen in pathogen disease tracking, but users should be aware that branch lengths might be affected. The NCBI is using a method called maximum compatability (40) to ensure that only real, or orthologous, SNPs are included in the phylogenetic analysis. For analyzing data sets with deeper divergences, one can use reference-free SNP calling methods (36, 37), include monomorphic sites in the data matrix (39), and/or adjust the model of evolution used in the maximum-likelihood analysis to mitigate aquisition bias (41).

Allele-based approaches. The other widely used rapid analysis approach is whole-genome (wg) or core-genome (cg) MLST, where the sequence for selected loci is coded as allele types. In this approach, orthologs are identified using an automated approach against a curated database of possible alleles, and a sequence type is assigned to the isolate that can be used for downstream phylogenetic analyses. The abstraction of one or more indels and/or SNPs within each gene into a single allele call results in a character matrix of allele types (1,2,3…n) instead of the underlying nucleotides (A, C, G, or T), as with an SNP matrix. In contrast to SNP approaches, wgMLST or cgMLST approaches must use highly curated databases unique for each taxon of interest. There have been several wgMLST or cgMLST schemas developed recently for Listeria monocytogenes (42–44), Campylobacter jejuni (45), and Salmonella enterica (46, 47). Although this approach is much faster and potentially more automated than SNP-based approaches, heavy curation of the MLST databases are required to keep this method up to date.

Phylogenetic inference for allele-based approaches. The resulting character matrix from MLST analyses are similar to SNP matrixes in that they both contain rows of taxa and columns of variant characters. However, these matrixes are different in that the variant characters (columns) each represent an individual gene with character states that are numbered, or coded, to represent some type of change within that gene (indel, SNP, or both). Because these matrixes comprise allele calls instead of nucleotides, standard models of sequence evolution used in maximum-likelihood and Bayesian analyses cannot be used here. Instead, nonprobabilistic phylogenetic inference methods, such as distance and maximum parsimony, are usually employed.

VALIDATION EFFORTS TO DATE

Pathogen biology.

Foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella, Listeria, E. coli, and Campylobacter cause human illness through the consumption of contaminationed food. Transmission networks for these pathogens originate with a contaminated product that spreads clonally within the human population. This pattern results in a distinctive tree topology having one large polytomy, or outbreak clade, that contains both source (food/environmental) and clinical isolates, with no significant genomic differences between the two. Scientists at FDA-CFSAN (48) investigated the genome biology of Salmonella by testing the variability of laboratory replicates along side empirical replicates within an outbreak cluster. Numerous replicate isolates picked from a single S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Montevideo (S. enterica serovar Montevideo) strain were sequenced to identify genomic differences (i.e., nucleotide substitutions) that might be attributable to variations in sample preparation, errors in sequencing procedures, or additional passaging of cultures. The results showed one to two SNP differences were possible between a parent strain and the newly subcultured daughter strain. However, based on this study and multiple other retrospective outbreak analyses in which isolates were collected from both food and clinical patients (49–51), these nucleotide substitutions are random and clocklike at this level of resolution and do not obscure or alter the phylogenetic history or conclusions drawn from the phylogenetic topology. This observation has held up at all levels within and between serovars of Salmonella and Listeria, showing that outbreak investigators using these methods can do so with the confidence that their conclusions and the linkages that they establish are scientifically sound.

NGS data collection.

Several labs have published on their validation efforts for using WGS in pathogen tracking and surveillance (31, 32). In particular, Kozyreva et al. (32) includes an assessment of the accuracy of the Illumina MiSeq platform, finding an accuracy of >99.999% agreement between newly collected MiSeq data compared to a known reference, accounting for possible genetic mutations and PCR error, and a base calling accuracy of of >99.9999% within and between runs. The use of NGS for national and global pathogen monitoring means that interlab comparability is critical. This is being addressed by annual multilab proficiency tests (PTs) across the GenomeTrakr lab network (52) (and now jointly across the PulseNet/GenomeTrakr network). In this exercise, participating labs each sequence the same set of bacterial pathogen isolates, and resulting data are used to assess the proficiency of the lab. In addition, summarizing the sequence data collected across the exercise enables an estimate of normal genetic variation within clonal isolates and expected error in several key areas, such as sequence quality, read mapping, assembly, insert sizes, and variant detection pipelines. Timme et al. observed a low number of SNPs (0 to 4) across all isolates submitted in the PT exercise, with the majority (73%) having 0 SNPs. These SNPs either reflect real genetic mutations or error in the data collection, such as amplification error. Either way, these data show a minimum of 99.99992% platform accuracy and thus are in agreement with the numbers reported by Kozyreva et al., which provides confidence in the use of this technology in decision making for public health applications such as outbreak detection, outbreak management, food facility inspection positives analysis, and monitoring for antibiotic resistance elements. The raw data, complete reference genomes, and a table of metrics summarized in the PT were made publicly available for the PT study (52), so this exercise can be fully replicated in a new lab looking to compare their sequencing quality to the data collected in this exercise.

WGS analysis.

Given the diversity of pipelines within and between these different approaches, it is important to allow for innovation while validating that the results are accurate and reproducible. Instead of trying to standarize analysis methods across the world, validation approaches that allow different implemented pipelines to continue to make incremental improvements as needed while also being free to evolve and innovate in response to the ever-changing landscape of sequence technology will work best for the public health community. This is also analogous to most wet-lab validation approaches, e.g., several different DNA isolation kits could be validated for the same DNA extraction step, the result of which are all the same (pure DNA).

One approach to analysis validation focuses on well-vetted data sets that can be run through any relevant phylogenomic pipeline, comparing the “test” results against the known “truth.” These benchmark data sets can be assembled through empirical approaches, or they can be entirely simulated. On the empirical side a set of vetted, well-studied, retrospective data sets can be used to validate results—in this case the “truth” is not actually knowable, but rather the result is supported by multiple lines of evidence with no disagreement among the community working with that respective data set. In molecular epidemiology these benchmark data sets represent a well-studied outbreak or other clonal event with strong WGS plus epidemiological concordance. These data sets comprise the following observed data: a set of raw fastq files collected from the event, a phylogeny, a file with variant calls (VCF file), and epidemiological metadata describing the isolates (related or unrelated to outbreak event). The Gen-FS (CDC, 2015) group published a set of benchmark data sets for foodborne pathogens exactly for this purpose (53). These data sets can be used to validate the SNP calling step by comparing test versus “truth” VCF files, as well as comparing the resulting tree topologies of the test pipeline versus the tree accompanying the benchmark data set. A GMI workgroup has taken over the curation of these benchmark data sets and is expanding them to include new species and scenarios to better serve the community (54). However, growing benchmark data sets through empirical, or observed, data is a slow, tedious, manual process. Alternatively, benchmark data sets can be entirely simulated (38), enabling a researcher to explore the full parameter space across multiple metrics (sequence coverage, sequence quality, tree topology, rate of sequence evolution, rate of indels, etc.). Once the simulated data sets are built, they can be used exactly the same way as the empirical benchmark data sets, comparing the test result to the truth, except in this case the “truth” is known for certain.

Published validation results using the empirical benchmark data sets were included in Katz et al. for comparing SNP pipelines versus cgMLST approaches (34). In addition, simulated data sets showed that the CFSAN SNP Pipeline was able to consistently recover the correct phylogeny under different simulation scenarios (38).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Although the basic tools have been published for analysis validation (both observed and simulated benchmark data sets), utilizing these tools for a broader validation of analytical methods for foodborne pathogen surveillance would be of great benefit. For example, a few published validation studies to date show that phylogenomic pipelines currently being used in public health are highly consistent given a set of parameters (data quality, pathogen species, sequence divergence, and tree shape [34, 55]). Initial success with using these data sets prompts the desire for many more benchmark data sets that cover the range of scenarios observed in real life. Consortiums such as the Globial Microbial Identifier (GMI) are working to increase this diversity by adding data sets from different species of pathogens, with different tree topology shapes, rates of evolution, and rates of horizontal gene transfer through plasmids and other mobile elements. This is needed to cover the diversity of foodborne pathogens, but also for other pathogen-caused diseases. For example, how do our current foodborne disease surveillance analysis methods perform on pathogens that have different genome architectures and transmission networks? Phylogenetic trees of foodborne outbreaks have the shape of “super spreaders,” where a single point source (food) causes numerous illnesses (56). This classic tree topology comprises a set of outgroups and usually one large polytomy or “outbreak” clade containing both source (food/environmental) and clinical isolates. Other transmission networks resulting from different diseases (e.g., HIV, flu, etc.) can have quite different shapes when there is person-to-person transmission. Considering all these possibilities, but focusing on the foodborne surveillance, we find that utilizing both types of benchmark data sets, empirical and simulated, will enable us to explore the parameter space expected so that we can ensure that our pipelines are accurate and consistent when run within that validated space. In addition, the community would also benefit from sets of gold standard SNPs accompanying several of the benchmark data sets described by Timme et al. (53). The SNPs or variants collected by these pipelines must be orthologous. The requirement of orthology still holds here, so these new methods must distinguish between true variants and variants introduced by sequence artifacts, assembly error, or HGT having a set of “known” SNPs is key for validating the variant calling step in both SNP and wgMLST pipelines.

CONCLUSIONS

Phylogenetics has a long academic history, starting with the conceptual picture from Darwin, and maturing in the computer age with tools of phylogenetic inference algorithms and NGS to really bear out its promise in real-time pathogen surveillance. The method is now being used for real-time disease surveillance for the top five foodborne pathogens in the United States. Both SNP-based and wgMLST-based phylogenomic analysis approaches have been widely adopted for foodborne pathogen surveillance; it is crucial that these approaches are validated in context. To this end, the foodborne pathogen community has made numerous strides in ensuring that these methods are validated through the formal collaboration within two consortiums: on the U.S. national level within Gen-FS and on the global level within the GMI. This community is actively engaged in addressing the key remaining areas, like the establishment of gold standard SNPs to accompany the benchmark data sets, thus providing a better understanding of the parameter space in which the phylogenomic pipelines are validated to include parameters such as sequence quality levels, sequence diversity, choice of reference genome, tree topology, ecology and biology of the pathogen, and perhaps the effect of increased horizontal gene transfer. Rigorous validation practices will allow researchers to properly understand the limits of our existing analytic pipelines, while also building confidence in the way these tools can inform public health decisions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and, more specifically, the GenomeTrakr team.

We thank Lili Velez for her careful editorial improvements and our two reviewers, who greatly improved the final manuscript. We also thank the many collaborators in the GenomeTrakr network who contributed WGS data for real-time surveillance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ou C-Y, Ciesielski CA, Myers G, Bandea CI, Luo C-C, Korber BTM, Mullins JI, Schochetman G, Berkelman RL, Economou AN, Witte JJ, Furman LJ, Satten GA, Maclnnes KA, Curran JW, Jaffe HW. 1992. Molecular epidemiology of HIV transmission in a dental practice. Science 256:1165–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmes EC, Nee S, Rambaut A, Garnett GP, Harvey PH. 1995. Revealing the history of infectious disease epidemics through phylogenetic trees. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 349:33–40. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1995.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thacker SB, Berkelman RL. 1988. Public health surveillance in the United States. Epidemiol Rev 10:164–190. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swaminathan B, Barrett TJ, Hunter SB, Tauxe RV, CDC PulseNet Task Force. 2001. PulseNet: the molecular subtyping network for foodborne bacterial disease surveillance, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 7:382–389. doi: 10.3201/eid0703.010303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flahault A, Dias-Ferrao V, Chaberty P, Esteves K, Valleron AJ, Lavanchy D. 1998. FluNet as a tool for global monitoring of influenza on the Web. JAMA 280:1330–1332. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glynn MK, Lee LM, McKenna MT. 2007. The status of national HIV case surveillance, United States 2006. Public Health Rep 122(Suppl 1):63–71. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanger F, Coulson AR. 1975. A rapid method for determining sequences in DNA by primed synthesis with DNA polymerase. J Mol Biol 94:441–448. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghedin E, Sengamalay NA, Shumway M, Zaborsky J, Feldblyum T, Subbu V, Spiro DJ, Sitz J, Koo H, Bolotov P, Dernovoy D, Tatusova T, Bao Y, St George K, Taylor J, Lipman DJ, Fraser CM, Taubenberger JK, Salzberg SL. 2005. Large-scale sequencing of human influenza reveals the dynamic nature of viral genome evolution. Nature 437:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gifford RJ, de Oliveira T, Rambaut A, Pybus OG, Dunn D, Vandamme A-M, Kellam P, Pillay D, UK Collaborative Group on HIV Drug Resistance. 2007. Phylogenetic surveillance of viral genetic diversity and the evolving molecular epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 81:13050–13056. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00889-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Köser CU, Ellington MJ, Cartwright EJP, Gillespie SH, Brown NM, Farrington M, Holden MTG, Dougan G, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Peacock SJ. 2012. Routine use of microbial whole-genome sequencing in diagnostic and public health microbiology. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002824. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sintchenko V, Iredell JR, Gilbert GL. 2007. Pathogen profiling for disease management and surveillance. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:464–470. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kühnert D, Wu C-H, Drummond AJ. 2011. Phylogenetic and epidemic modeling of rapidly evolving infectious diseases. Infect Genet Evol 11:1825–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foley BT, Korber BTM, Leitner TK, Apetrei C, Hahn B, Mizrachi I, Mullins J, Rambaut A, Wolinsky S. 2018. HIV sequence compendium 2018. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM. [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC. 2018. HIV cluster and outbreak detection and response. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/programresources/guidance/molecular-cluster-identification/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGinnis J, Laplante J, Shudt M, George KS. 2016. Next generation sequencing for whole genome analysis and surveillance of influenza A viruses. J Clin Virol 79:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatcher EL, Zhdanov SA, Bao Y, Blinkova O, Nawrocki EP, Ostapchuck Y, Schäffer AA, Brister JR. 2017. Virus variation resource. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D482–D490. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bao Y, Bolotov P, Dernovoy D, Kiryutin B, Zaslavsky L, Tatusova T, Ostell J, Lipman D. 2008. The Influenza Virus Resource at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. J Virol 82:596–601. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02005-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allard MW, Strain E, Melka D, Bunning K, Musser SM, Brown EW, Timme R. 2016. Practical value of food pathogen traceability through building a whole-genome sequencing network and database. J Clin Microbiol 54:1975–1983. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00081-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson BR, Tarr C, Strain E, Jackson KA, Conrad A, Carleton H, Katz LS, Stroika S, Gould LH, Mody RK, Silk BJ, Beal J, Chen Y, Timme R, Doyle M, Fields A, Wise M, Tillman G, Defibaugh-Chavez S, Kucerova Z, Sabol A, Roache K, Trees E, Simmons M, Wasilenko J, Kubota K, Pouseele H, Klimke W, Besser J, Brown E, Allard M, Gerner-Smidt P. 2016. Implementation of nationwide real-time whole-genome sequencing to enhance listeriosis outbreak detection and investigation. Clin Infect Dis 63:380–386. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NCBI. 2018. Pathogen detection. U.S. National Library of Medicine/National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rehm HL, Bale SJ, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Berg JS, Brown KK, Deignan JL, Friez MJ, Funke BH, Hegde MR, Lyon E, Working Group of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Laboratory Quality Assurance Commitee. 2013. ACMG clinical laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing. Genet Med 15:733–747. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Commitee. 2015. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17:405–423. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linderman MD, Brandt T, Edelmann L, Jabado O, Kasai Y, Kornreich R, Mahajan M, Shah H, Kasarskis A, Schadt EE. 2014. Analytical validation of whole exome and whole-genome sequencing for clinical applications. BMC Med Genomics 7:20. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-7-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lih C-J, Harrington RD, Sims DJ, Harper KN, Bouk CH, Datta V, Yau J, Singh RR, Routbort MJ, Luthra R, Patel KP, Mantha GS, Krishnamurthy S, Ronski K, Walther Z, Finberg KE, Canosa S, Robinson H, Raymond A, Le LP, McShane LM, Polley EC, Conley BA, Doroshow JH, Iafrate AJ, Sklar JL, Hamilton SR, Williams PM. 2017. Analytical validation of the next-generation sequencing assay for a nationwide signal-finding clinical trial: molecular analysis for therapy choice clinical trial. J Mol Diagn 19:313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gargis AS, Kalman L, Lubin IM. 2016. Assuring the quality of next-generation sequencing in clinical microbiology and public health laboratories. J Clin Microbiol 54:2857–2865. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00949-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett NC, Farah CS. 2014. Next-generation sequencing in clinical oncology: next steps towards clinical validation. Cancers (Basel) 6:2296–2312. doi: 10.3390/cancers6042296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deans Z, Watson CM, Charlton R, Ellard S, Wallis Y, Mattocks C, Abbs S. 2007. Best practice guidelines for targeted next generation sequencing. Association for Clinical Genetic Science, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss MM, Van der Zwaag B, Jongbloed JDH, Vogel MJ, Brüggenwirth HT, Lekanne Deprez RH, Mook O, Ruivenkamp CAL, van Slegtenhorst MA, van den Wijngaard A, Waisfisz Q, Nelen MR, van der Stoep N. 2013. Best practice guidelines for the use of next-generation sequencing applications in genome diagnostics: a national collaborative study of Dutch genome diagnostic laboratories. Hum Mutat 34:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/humu.22368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy S, Coldren C, Karunamurthy A, Kip NS, Klee EW, Lincoln SE, Leon A, Pullambhatla M, Temple-Smolkin RL, Voelkerding KV, Wang C, Carter AB. 2018. Standards and guidelines for validating next-generation sequencing bioinformatics pipelines: a joint recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology and the College of American Pathologists. J Mol Diagn 20:4–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Portmann A-C, Fournier C, Gimonet J, Ngom-Bru C, Barretto C, Baert L. 2018. A validation approach of an end-to-end whole genome sequencing workflow for source tracking of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica. Front Microbiol 9:446. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozyreva VK, Truong C-L, Greninger AL, Crandall J, Mukhopadhyay R, Chaturvedi V. 2017. Validation and implementation of Clinical Laboratory Improvements Act (CLIA)-compliant whole genome sequencing in public health microbiology laboratory. J Clin Microbiol 55:2502–2520. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00361-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis S, Pettengill JB, Luo Y, Payne J, Shpuntoff A, Rand H, Strain E. 2015. CFSAN SNP Pipeline: an automated method for constructing SNP matrices from next-generation sequence data. PeerJ Comput Sci 1:e20. doi: 10.7717/peerj-cs.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katz LS, Griswold T, Williams-Newkirk AJ, Wagner D, Petkau A, Sieffert C, Van Domselaar G, Deng X, Carleton HA. 2017. A comparative analysis of the Lyve-SET phylogenomics pipeline for genomic epidemiology of foodborne pathogens. Front Microbiol 8:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reference deleted.

- 36.Gardner SN, Hall BG. 2013. When whole-genome alignments just won’t work: kSNP v2 software for alignment-free SNP discovery and phylogenetics of hundreds of microbial genomes. PLoS One 8:e81760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertels F, Silander OK, Pachkov M, Rainey PB, van Nimwegen E. 2014. Automated reconstruction of whole-genome phylogenies from short-sequence reads. Mol Biol Evol 31:1077–1088. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McTavish EJ, Pettengill J, Davis S, Rand H, Strain E, Allard M, Timme RE. 2017. TreeToReads: a pipeline for simulating raw reads from phylogenies. BMC Bioinformatics 18:178. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1592-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahl JW, Lemmer D, Travis J, Schupp JM, Gillece JD, Aziz M, Driebe EM, Drees KP, Hicks ND, Williamson CHD, Hepp CM, Smith DE, Roe C, Engelthaler DM, Wagner DM, Keim P. 2016. NASP: an accurate, rapid method for the identification of SNPs in WGS datasets that supports flexible input and output formats. Microb Genom 2:e000074. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cherry JL. 2017. A practical exact maximum compatibility algorithm for reconstruction of recent evolutionary history. BMC Bioinformatics 18:127. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1520-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leaché AD, Banbury BL, Felsenstein J, de Oca AN-M, Stamatakis A. 2015. Short tree, long tree, right tree, wrong tree: new acquisition bias corrections for inferring SNP phylogenies. Syst Biol 64:1032–1047. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syv053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pightling AW, Petronella N, Pagotto F. 2015. The Listeria monocytogenes Core-Genome Sequence Typer (LmCGST): a bioinformatic pipeline for molecular characterization with next-generation sequence data. BMC Microbiol 15:224. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0526-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moura A, Criscuolo A, Pouseele H, Maury MM, Leclercq A, Tarr C, Björkman JT, Dallman T, Reimer A, Enouf V, Larsonneur E, Carleton H, Bracq-Dieye H, Katz LS, Jones L, Touchon M, Tourdjman M, Walker M, Stroika S, Cantinelli T, Chenal-Francisque V, Kucerova Z, Rocha EPC, Nadon C, Grant K, Nielsen EM, Pot B, Gerner-Smidt P, Lecuit M, Brisse S. 2016. Whole genome-based population biology and epidemiological surveillance of Listeria monocytogenes. Nat Microbiol 2:16185. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lüth S, Kleta S, Dahouk Al S. 2018. Whole-genome sequencing as a typing tool for foodborne pathogens like Listeria monocytogenes: the way towards global harmonization and data exchange. Trends Food Sci Technol 73:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2018.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cody AJ, McCarthy ND, Jansen van Rensburg M, Isinkaye T, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Dingle KE, Bowler ICJW, Jolley KA, Maiden MCJ. 2013. Real-time genomic epidemiological evaluation of human Campylobacter isolates by use of whole-genome multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol 51:2526–2534. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00066-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor AJ, Lappi V, Wolfgang WJ, Lapierre P, Palumbo MJ, Medus C, Boxrud D. 2015. Characterization of foodborne outbreaks of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis with whole-genome sequencing single nucleotide polymorphism-based analysis for surveillance and outbreak detection. J Clin Microbiol 53:3334–3340. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01280-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yachison CA, Yoshida C, Robertson J, Nash JHE, Kruczkiewicz P, Taboada EN, Walker M, Reimer A, Christianson S, Nichani A, PulseNet Canada Steering Committee, Nadon C. 2017. The validation and implications of using whole genome sequencing as a replacement for traditional serotyping for a national Salmonella reference laboratory. Front Microbiol 8:1044. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allard MW, Luo Y, Strain E, Li C, Keys CE, Son I, Stones R, Musser SM, Brown EW. 2012. High resolution clustering of Salmonella enterica serovar Montevideo strains using a next-generation sequencing approach. BMC Genomics 13:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffmann M, Luo Y, Monday SR, Gonzalez-Escalona N, Ottesen AR, Muruvanda T, Wang C, Kastanis G, Keys C, Janies D, Senturk IF, Catalyurek UV, Wang H, Hammack TS, Wolfgang WJ, Schoonmaker-Bopp D, Chu A, Myers R, Haendiges J, Evans PS, Meng J, Strain EA, Allard MW, Brown EW. 2016. Tracing origins of the Salmonella Bareilly strain causing a foodborne outbreak in the United States. J Infect Dis 213:502–508. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Y, Burall LS, Luo Y, Timme R, Melka D, Muruvanda T, Payne J, Wang C, Kastanis G, Maounounen-Laasri A, De Jesus AJ, Curry PE, Stones R, KAluoch O, Liu E, Salter M, Hammack TS, Evans PS, Parish M, Allard MW, Datta A, Strain EA, Brown EW. 2016. Isolation, enumeration and whole-genome sequencing of Listeria monocytogenes in stone fruits linked to a multistate outbreak. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:7030–7040. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01486-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lienau EK, Strain E, Wang C, Zheng J, Ottesen AR, Keys CE, Hammack TS, Musser SM, Brown EW, Allard MW, Cao G, Meng J, Stones R. 2011. Identification of a salmonellosis outbreak by means of molecular sequencing. N Engl J Med 364:981–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1100443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Timme RE, Rand H, Sanchez Leon M, Hoffmann M, Strain E, Allard M, Roberson D, Baugher JD. 2018. GenomeTrakr proficiency testing for foodborne pathogen surveillance: an exercise from 2015. Microbial Genomics 57:289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timme RE, Rand H, Shumway M, Trees EK, Simmons M, Agarwala R, Davis S, Tillman GE, Defibaugh-Chavez S, Carleton HA, Klimke WA, Katz LS. 2017. Benchmark datasets for phylogenomic pipeline validation, applications for foodborne pathogen surveillance. PeerJ 5:e3893. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Global Microbial Identifier, Workgroup 3. 2018. Benchmark datasets for phylogenomic validation. GitHub. https://github.com/globalmicrobialidentifier-WG3/datasets. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Page AJ, Alikhan N-F, Carleton HA, Seemann T, Keane JA, Katz LS. 2017. Comparison of classical multi-locus sequence typing software for next-generation sequencing data. Microb Genomics 3:e000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colijn C, Gardy J. 2014. Phylogenetic tree shapes resolve disease transmission patterns. Evol Med Public Health 2014:96–108. doi: 10.1093/emph/eou018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]