SUMOylation is an extensively discussed posttranslational modification in diverse cellular biological pathways. However, there is limited understanding about SUMOylation of viral proteins of IBDV during infection. In the present study, we revealed a SUMO1 modification of VP1 protein, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of avibirnavirus infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV). The required site of VP1 SUMOylation comprised residues 404I and 406I of SUMO interaction motif 3, which was essential for maintaining its stability by inhibiting K48-linked ubiquitination. We also showed that IBDV with SUMOylation-deficient VP1 had decreased replication ability. These data demonstrated that the SUMOylation of IBDV VP1 played an important role in maintaining IBDV replication.

KEYWORDS: avibirnavirus, SUMO1 modification, VP1 protein, stability, viral replication

ABSTRACT

SUMOylation is a posttranslational modification that has crucial roles in diverse cellular biological pathways and in various viral life cycles. In this study, we found that the VP1 protein, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of avibirnavirus infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV), regulates virus replication by SUMOylation during infection. Our data demonstrated that the polymerase VP1 is efficiently modified by small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SUMO1) in avibirnavirus-infected cell lines. Mutation analysis showed that residues 404I and 406I within SUMO interaction motif 3 of VP1 constitute the critical site for SUMO1 modification. Protein stability assays showed that SUMO1 modification enhanced significantly the stability of polymerase VP1 by inhibiting K48-linked ubiquitination. A reverse genetic approach showed that only IBDV with I404C/T and I406C/F mutations of VP1 could be rescued successfully with decreased replication ability. Our data demonstrated that SUMO1 modification is essential to sustain the stability of polymerase VP1 during IBDV replication and provides a potential target for designing antiviral drugs targeting IBDV.

IMPORTANCE SUMOylation is an extensively discussed posttranslational modification in diverse cellular biological pathways. However, there is limited understanding about SUMOylation of viral proteins of IBDV during infection. In the present study, we revealed a SUMO1 modification of VP1 protein, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of avibirnavirus infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV). The required site of VP1 SUMOylation comprised residues 404I and 406I of SUMO interaction motif 3, which was essential for maintaining its stability by inhibiting K48-linked ubiquitination. We also showed that IBDV with SUMOylation-deficient VP1 had decreased replication ability. These data demonstrated that the SUMOylation of IBDV VP1 played an important role in maintaining IBDV replication.

INTRODUCTION

SUMOylation is the covalent attachment of SUMO molecules to lysine (K) on the target protein (1). A SUMO molecule has an approximate molecular weight of 12 kDa; however, the covalent attachment of one SUMO moiety adds 20 kDa to the substrate (2). The mature SUMO peptide is activated by E1-activating enzyme (SUMO-activating enzymes 1 and 2 [SAE1/2]) in an ATP-dependent manner. The active SUMO is then transferred to Ubc9, the E2 conjugation enzyme (3). In contrast to the ubiquitination process, E3 SUMO ligase is optional for transferring the SUMO peptide to the substrate (4). As posttranslational modifications, the SUMOylation process could be also reversed by sentrin-specific proteases (SENPs), which act as de-SUMOylation enzymes (5). Generally, the lysine following the motif ΨKXE/D (where Ψ represents a large hydrophobic amino acid and X represents any amino acid) is the SUMOylation acceptor site (6). In addition, the covalent modification of substrate proteins can be regulated by the SUMO interaction motif (SIM), which contains hydrophobic amino acids with the following consensus motif: V/I/L-X-V/I/L-V/I/L (7–10).

Both ubiquitination and SUMOylation occur on lysine residues (11). The stability of the substrate protein can be regulated by competition or cooperation between SUMOylation and ubiquitination (12). SUMOylation of many cellular proteins has been reported. However, increasing evidence shows that several viral proteins have been identified as the substrate of SUMOylation, i.e., the nonstructural protein 1, matrix protein M1, and nucleoprotein of influenza A virus (13), the Gag polyprotein of immunodeficiency virus type 1 particle, which is critical for virus replication (14), the 3D protein of enterovirus 71 (8), and nonstructural protein 5 of dengue virus (9). Also, SUMO1 modification of the antigen protein of hepatitis delta virus specifically enhanced its RNA genome replication (15). However, the roles of SUMOylation in infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) replication are unclear.

IBDV, the representative member of the genus Avibirnavirus in the family Birnaviridae, causes an acute, highly contagious, and immunosuppressive disease in young chickens, which affects the poultry industry worldwide (16). The double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genome of IBDV contains two segments, A and B (17). Segment A encodes nonstructural protein VP5 and precursor polyprotein pVP2-VP4-VP3, which can be cleaved autoproteolytically into VP3, VP4, and precursor VP2 (18, 19). Segment B produces polymerase protein VP1, which is responsible for viral genome replication, transcription, and final packaging (20, 21). Posttranslational modifications of polymerase VP1 involved in regulating IBDV replication are poorly understood, although VP4 was identified as the phosphorylation protein that affects the self-hydrolysis activity (22).

In the present study, we first determined that IBDV VP1 was efficiently modified by SUMO1 molecules during virus infection. The residues 404I and 406I within SIM3 of VP1 were identified as essential sequence required for its SUMO1 modification. Mutation of 404I and 406I impaired VP1’s stability. SUMOylation of VP1 could increase its stability by inhibiting K48-linked ubiquitination to maintain IBDV replication. We also demonstrated that mutant IBDV with unSUMOylated VP1 I404C/T and I406C/F mutants could be rescued with decreased replication ability, indicating that IBDV hijacks the SUMOylation system for maintaining its replication.

RESULTS

The polymerase protein VP1 is SUMOylated during avibirnavirus infection.

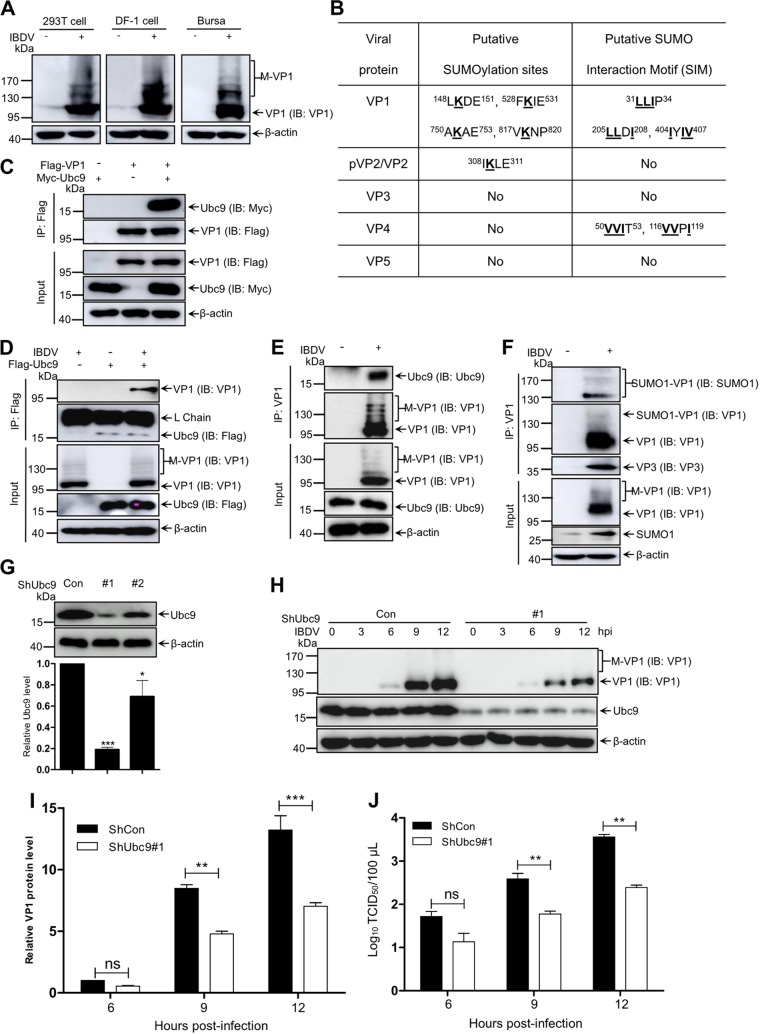

SUMOylation was reported to be involved in several virus life cycles (23). To explore the chemical modification of viral proteins in avibirnavirus infection, lysates from IBDV-infected DF-1 and 293T cells were probed with monoclonal antibody (MAb) recognizing VP1 of IBDV by immunoblotting. The polymerase VP1 exhibited the protein bands with different molecular weights, named as posttranslation modifications of VP1 (M-VP1). Similar results were obtained from lysates from an IBDV-infected target organ, chicken’s bursa of Fabricius (BF) (Fig. 1A). To explore whether SUMOylation affects replication of IBDV, we used two SUMOylation online prediction programs, GPS-SUMO1.0 (http://sumosp.biocuckoo.org/) and SUMOplot (http://www.abgent.com/sumoplot), to predict SUMOylation of IBDV-encoded proteins. As shown in Fig. 1B, of five IBDV-encoded proteins, polymerase VP1 contains four candidate SUMOylation sites and three putative SUMO interaction motifs (SIM), capsid protein pVP2/VP2 contains only one candidate SUMOylation site, protease VP4 contains two putative SIM, and both VP3 and VP5 proteins contain no SUMOylated sites or putative SIM. We next focused on chemical modification of VP1 protein. Figure 1C showed that Myc-Ubc9 could be efficiently immunoprecipitated by Flag-VP1 via coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays. Consistently, the VP1 could interact with Flag-Ubc9 during IBDV infection (Fig. 1D). Immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-VP1 antibody further suggested that Ubc9 had an interaction with VP1 (Fig. 1E). Based on the VP1 interaction with Ubc9, to verify whether VP1 could be modified by SUMO1, DF-1 cells infected with IBDV for 12 h were subjected to SUMOylation assays. As shown in Fig. 1F, anti-SUMO1 antibody could detect SUMOylated VP1 band with a molecular weight of ∼140 kDa to ∼180 kDa, while anti-VP1 antibody could detect free VP1 (∼100 kDa) and SUMOylated VP1 (∼140 kDa), meaning that VP1 could be efficiently attached to SUMO1 molecules. These data suggested that the polymerase protein VP1 could be efficiently modified by SUMO1 during IBDV infection.

FIG 1.

SUMOylation modification of avibirnavirus polymerase VP1 during virus infection. (A) Modified bands of VP1 during virus infection. Lysates from 293T cells and DF-1 cells infected with IBDV at an MOI of 5 for 12 h, and bursae of Fabricius (BF) of 5-week-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chickens infected with virulent IBDV strain NB at a dose of 0.1 ml (2 × 103 50% bird lethal doses/ml) for 72 h, were subjected to Western blotting (IB) using anti-VP1 MAb 1D4. (B) SUMOylation online prediction of viral proteins of IBDV by GPS-SUMO1.0 and SUMOplot. (C) VP1 interacts with Ubc9 during transfection. 293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-VP1 and Myc-Ubc9 for 36 h. (D) Ubc9 interacts with viral protein VP1 during IBDV infection. DF-1 cells were transfected with Flag-Ubc9 for 24 h and then infected with IBDV at an MOI of 5 for 12 h. (E) VP1 interacts with Ubc9 during IBDV infection. DF-1 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 5 for 12 h. (F) VP1 protein is efficiently modified by SUMO1 during infection. DF-1 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 5 for 12 h. Harvested cells were subjected to IP with the indicated antibodies and to Western blotting with the anti-Flag, anti-Myc antibody, anti-VP1, anti-Ubc9, and anti-SUMO1 antibodies (C to F). (G) Selection of efficient anti-Ubc9 shRNA in DF-1 cells. (H) Decrease of IBDV protein expression in Ubc9 knockdown cells. Ubc9 knockdown DF-1 cells (shUbc9#1) were infected with IBDV (MOI = 1) for the indicated time. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting by anti-VP1 mAbs. β-Actin expression as a loading control. (I) Statistic histogram of data in panel H. (J) Titer of IBDV in Ubc9 knockdown cells. Ubc9 knockdown DF-1 cells (shUbc9#1) were infected with IBDV (MOI = 1) for the indicated times. Cell lysates were collected and subjected to TCID50 assay. Three independent experiments were performed.

To further explore the role of SUMOylation in the IBDV life cycle, we constructed Ubc9 knockdown DF-1 cells (Fig. 1G). As shown in Fig. 1H and I, in comparison with that in control cells, the expression of viral protein was significantly reduced in the Ubc9-silencing cells infected with IBDV. Also, the virus titer was dramatically decreased, as determined by 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) assay, in Ubc9-silencing cells compared with that in control cells (Fig. 1J). Together, these results consistently indicated that cellular SUMO modification is important for the IBDV life cycle.

SUMO1 and Ubc9 are essential for SUMOylation of avibirnavirus polymerase VP1.

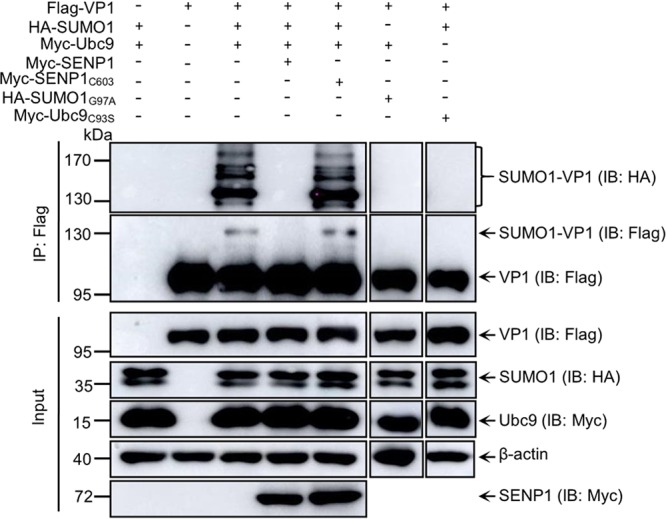

To further confirm the SUMOylation modification of polymerase VP1, 293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-VP1 and HA-SUMO1 along with Myc-Ubc9 and then treated with NP-40 buffer containing 20 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM; a global inhibitor of cysteine-based enzymes, including de-SUMOylases) in IP assays with anti-Flag antibodies for enhancing SUMOylated VP1 detection. As shown in Fig. 2, antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibody could detect SUMOylated VP1 bands with molecular weights of ∼140 kDa to ∼180 kDa, while anti-Flag antibody could detect free Flag-VP1 with a molecular weight of∼100 kDa and a SUMOylated VP1 band with a molecular weight of ∼140 kDa, indicating that polymerase VP1 was partly SUMOylated. Residue 93C of Ubc9 and residue 97G of SUMO1 were reported to be the active sites for SUMOylation of the substrate (24). To confirm the active sites of SUMO1 and Ubc9 for VP1 SUMOylation, we constructed the Ubc9 C93S mutant (Ubc9C93S) and the SUMO1 G97A mutant (SUMO1G97A), which were subsequently transfected into cells. SUMOylation assays showed that the SUMOylated VP1 bands were not exhibited in the Ubc9C93S-transfected cells and in the SUMO1G97A-transfected cells, indicating that SUMOylation of VP1 depends on the active site of SUMO1 and Ubc9 (Fig. 2). The SUMOylation system is a highly dynamic system that could be reversed by cellular de-SUMOylation enzymes, such as SENP1. The cysteine (C) residue at position 603 of SENP1 functions as an active site of SUMO1 covalent attachment (25). To identify the role of SENP1, we constructed SENP1 and SENP1 C603S mutant (SENP1C603S) expression vectors, which were transfected into cells along with Flag-VP1 and HA-SUMO1 Myc-Ubc9 for SUMOylation assays. We found that SENP1 could completely remove the SUMOylated VP1 band, but SENP1C603S could not (Fig. 2), indicating that SENP1 was responsible for reversing VP1 SUMOylation. Taken together, these data suggest that the SUMOylation of IBDV VP1 is dependent on the Ubc9 and SUMO1 active sites.

FIG 2.

SUMO1 and Ubc9 participate in polymerase VP1 SUMOylation. SUMOylation of VP1 is dependent on the Ubc9 and SUMO1 active site and could be reversed by SENP1. 293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-VP1, HA-SUMO1, Myc-SUMO1, and Myc-SENP1 or Myc-SENP1C603S, HA-SUMO1G97A, or Myc-Ubc9C93S for 36 h. The cellular lysates were subjected to SUMOylation assays and Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. β-Actin expression served as a loading control.

SIM3 of VP1 is required for its SUMO1 modification.

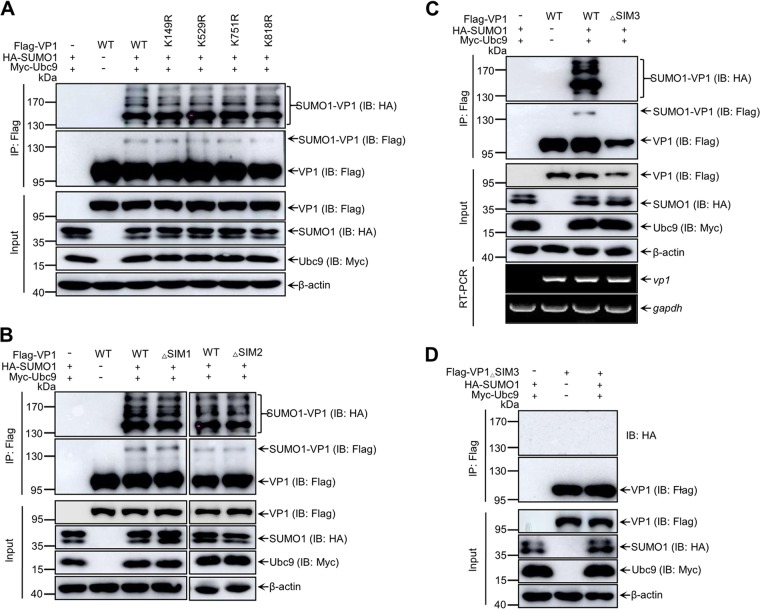

SUMOylation commonly occurs on lysine residues (K) of substrates (3). To identify four predicted potential SUMOylation sites of VP1 (Fig. 1B), we created K149R, K529R, K751R, and K818R VP1 mutants by mutating lysine residues to arginine (R). Wild-type (WT) VP1 and the mutated VP1s were cotransfected with HA-SUMO1 and Myc-Ubc9 into 293T cells to perform the SUMOylation assays. As shown in Fig. 3A, in comparison with WT VP1, none of the four VP1 mutants displayed an obvious change in SUMOylation level, implying that other amino acid residues of VP1 may be involved in SUMOylation of VP1. Therefore, we further focused on the three putative SIM, 31LLIP34, 205LLDIT208, and 404IYIV407, of VP1 (Fig. 1B). All hydrophobic residues within SIM were mutated to arginine to construct △SIM1 (31RRRP34), △SIM2 (204RRDR207), and △SIM3 (404RYRR407) VP1 mutants. In contrast to WT VP1, △SIM1 and △SIM2 VP1 mutants had no obvious reduction of SUMOylation (Fig. 3B). However, the SUMOylation bands of △SIM3 VP1 were undetectable (Fig. 3C and D) and the accumulation of △SIM3 VP1 was lower than that of WT VP1, but the mRNA level of △SIM3 VP1 was similar to that of WT VP1 as determined by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (Fig. 3C). Taken together, our data suggest that residues 404IYIV407 of SIM3 are critical for SUMO1 modification of VP1.

FIG 3.

Identification of SIM3 required for VP1 SUMO1 modification. (A) Identification of the candidate SUMOylation sites of VP1. 293T cells were cotransfected with Myc-Ubc9, HA-SUMO1, and Flag-VP1 or its truncation mutants for 36 h. (B to D) Identification of SIM3 required for VP1 SUMOylation. 293T cells were transfected with HA-SUMO1, Myc-Ubc9, and Flag-VP1 or Flag-VP1△SIM1 (B) or Flag-VP1△SIM2 (B) or Flag-VP1△SIM3 (C and D) for 36 h. Lysates of the cells were subjected to SUMOylation assays and Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. β-Actin expression served as a loading control. (C) Total cellular RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR amplification of vp1 and gapdh.

SUMO1 modification stabilizes polymerase VP1 via inhibiting K48-linked ubiquitination.

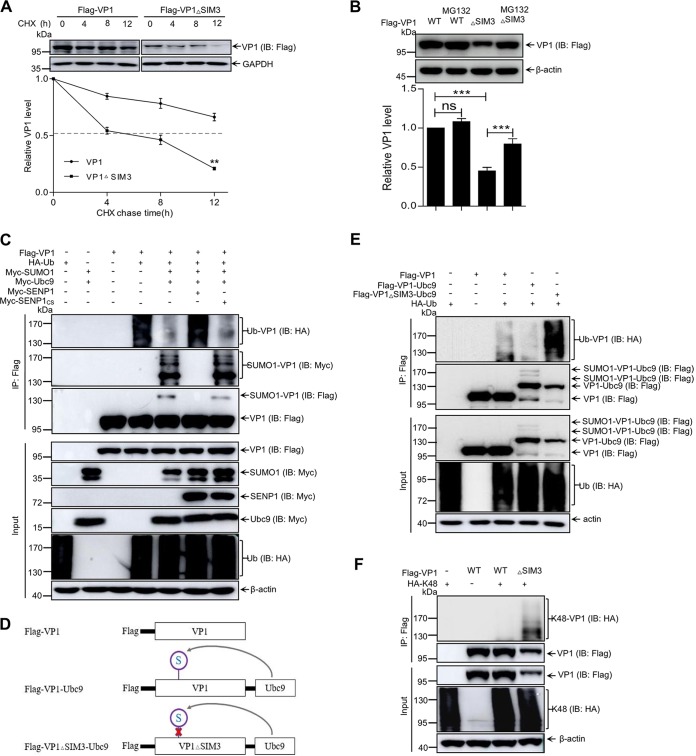

In △SIM3 of VP1-transfected cells, not only did SUMOylated VP1 almost disappear but also the total amount of VP1 with △SIM3 was obviously decreased compared with the level of WT VP1 (Fig. 3C). Does VP1 SUMOylation affect the stability of VP1? We performed cycloheximide (CHX) treatment experiments to analyze the difference in stability between WT VP1 and △SIM3 VP1. The △SIM3 VP1 showed a significantly shorter life span than that of WT VP1 (Fig. 4A). To address the reason for △SIM3 VP1’s instability, MG132 treatment was used in the experiments that followed. As shown in Fig. 4B, significant degradation of △SIM3 VP1 happened in cells without MG132 treatment compared with the WT control, whereas significantly less △SIM3 VP1 was degraded in the MG132-treated cells than in the △SIM3 VP1 nontreated cells, which suggested that △SIM3 VP1 without SUMOylation was degraded via the ubiquitin proteasome pathway.

FIG 4.

SUMO1 modification stabilizes VP1 by inhibiting ubiquitination. (A) SUMOylation modification increases the stability of VP1. 293T cells were individually transfected with Flag-VP1 or with Flag-VP1▵SIM3 for 24 h. The transfected cells were treated with 100 μg/ml of CHX for 0, 4, 8, and 12 h. (B) Blocking proteasome activity inhibits VP1▵SIM3 degradation. 293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h and then treated with MG132 (10 μg/ml) for 8 h before being harvested. The half-lives of VP1▵SIM3 and VP1 were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Three independent experiments were performed. (C and E) VP1 ubiquitination was inhibited by SUMO1 modifications. 293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 36 h. (D) Diagram presentation of VP1 infusion with Ubc9. (F) The VP1 with △SIM3 was enhanced with K48-linked ubiquitination. 293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-VP1 or Flag-VP1▵SIM3 and HA-K48 for 36 h. The cellular lysates were subjected to ubiquitination assays and Western blotting with anti-HA, anti-Myc, and anti-Flag antibodies. β-Actin expression served as a loading control.

Ubiquitination, especially K48-linked ubiquitination of target protein, commonly regulates protein stability (26). To explore whether the stability of SUMOylated VP1 involves ubiquitination, we investigated the relationship between ubiquitination and SUMOylation of VP1. The recombinant plasmids VP1 and VP1△SIM3 as well as HA-Ub were cotransfected into 293T cells for ubiquitination assays. Figure 4C shows that VP1 ubiquitination was remarkably inhibited in SUMO1- and Ubc9-overexpressing cells and was not suppressed in SUMO1-, Ubc9-, and SENP1-overexpressing cells. Next, VP1 ubiquitination was further validated by constructing the recombinant vector Ubc9 fused with VP1 (VP1-Ubc9) or with VP1△SIM3 (VP1△SIM3-Ubc9) (Fig. 4D). We found that VP1-Ubc9 ubiquitination was lower than VP1 ubiquitination, but the ubiquitination of unSUMOylated VP1△SIM3-Ubc9 was higher than that of VP1 and VP1-Ubc9 (Fig. 4E). We concluded that SUMO1 modification of VP1 could inhibit its ubiquitination. Subsequently, Fig. 4F showed that K48-linked ubiquitination of VP1△SIM3 was enhanced in comparison with that of WT VP1. These results suggested that SUMO1 modification could stabilize VP1 via inhibiting K48-linked ubiquitination.

SUMOylation of polymerase VP1 is required for enhancing IBDV replication.

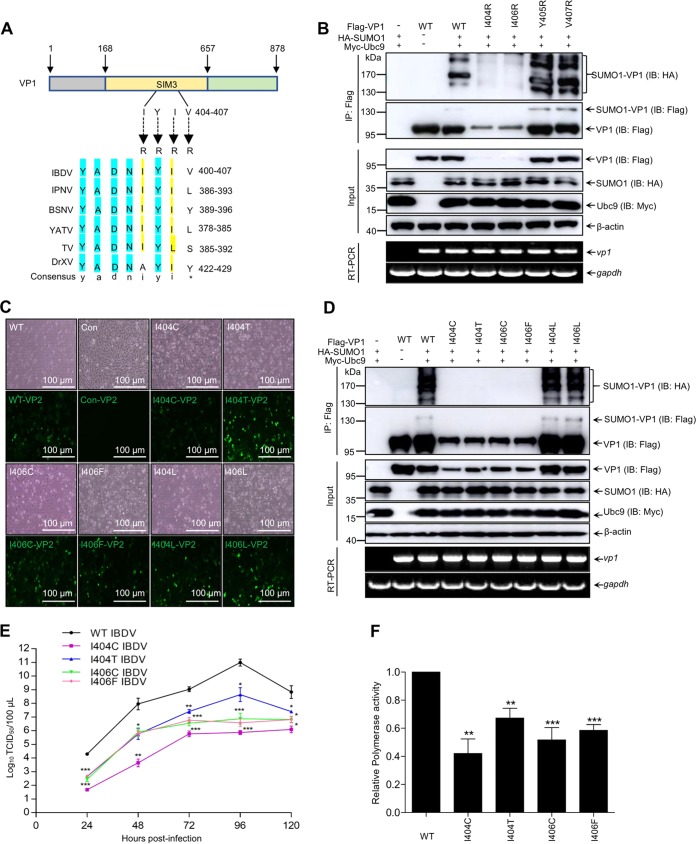

As shown in Fig. 5A, 404I and 406I within the motif 404IYIV407 of VP1 SIM3 were highly conserved among members of the family Birnaviridae. To further study the biological importance of SUMOylation of VP1, residues 404IYIV407 were individually mutated to R to create I404R, Y405R, I406R, and V407R VP1 mutants. All four mutants along with WT VP1 were subjected to SUMOylation assays. Compared with WT VP1, the I404R and I406R mutants showed dramatic reduction of VP1 SUMOylation, whereas the Y405R and V407R mutants showed no obvious alteration of VP1 SUMOylation (Fig. 5B), indicating that 404I and 406I were critical for VP1 SUMOylation. Subsequently, rescue of SUMO-deficient VP1 IBDV was performed by the T7 expression system (27). Except for methionine, residues 404I and 406I within VP1 SIM3 were individually mutated to 18 other amino acid residues in T7-B vector to produce 404I and 406I mutant viruses. Cytopathic effect (CPE) and capsid VP2 signals were detected in cells transfected by the vector containing the IBDV genome with WT VP1 or with I404C, I404T, I404L, I406C, I406F, and I406L VP1 mutants (Fig. 5C), while there was no CPE or capsid VP2 signal in cells transfected by the vector containing the IBDV genome with I404R or I406R mutant VP1 or VP1 with 404I or 406I mutated to other residues (data not shown), indicating that the I404C, I404T, I404L, I406C, I406F, and I406L mutations could successfully rescue infectious IBDV virions, and the infectious virions could not be rescued from the cells transfected by the IBDV genome with the mutation of 404I and 406I of VP1 to R or to other residues. Also, I404C, I406C, I404T, and I406F mutant VP1 showed no SUMOylation signals, while I404L and I406L mutant VP1 showed no obvious change in SUMOylation, revealing that mutation of 404I to C/T or 406I to C/F is also critical to VP1 SUMOylation (Fig. 5D). Virus replication assays showed that the replication ability of four mutant IBDVs was significantly decreased compared with that of WT IBDV, especially in the case of the I404C virus (Fig. 5E). Sequencing showed that those mutant IBDV VP1 was not reversed (data not shown). Moreover, we further investigated the effect of SUMOylation deficiency on polymerase activity of mutant VP1. As shown in Fig. 5F, SUMOylation deficiency of the VP1 mutants with changes of 404I to C/T and 406I to C/F induced a significant decrease of its polymerase activity. Overall, these results suggested that residues 404I and 406I were essential for maintaining VP1 SUMOylation and strengthening IBDV replication.

FIG 5.

SUMOylation of the viral protein VP1 maintains IBDV replication. (A) Multisequence alignment diagram of SIM3 among Birnariviridae polymerase VP1 from IBDV, infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV), blotched snakehead virus (BSNV), yellowtail ascites virus (YATV), Tellina virus (TV), and Drosophila X virus (DrXV). (B) Residues 404I and 406I of VP1 are essential for its SUMOylation. 293T cells were cotransfected with Myc-Ubc9, HA-SUMO1, and Flag-VP1 or its mutants for 36 h. Cellular lysates were subjected to SUMOylation assays and Western blotting with the indicated antibodies, as well as RT-PCR for detecting the mRNA of vp1 and gapdh. (C) Rescue of IBDV with VP1 mutants. DF-1 cells were infected with the indicated mutant virus and observed under a phase-contrast microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) for detecting CPE. The resultant cells were stained with anti-VP2 MAb and FITC anti-mouse IgG. The image was scanned with an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon). Scale bars, 100 μm. (D) I404C/T and I406C/F mutant VP1 displayed non-SUMOylation of VP1. 293T cells were cotransfected with Myc-Ubc9, HA-SUMO1, and Flag-VP1 or its mutants for 36 h. Cellular lysates were subjected to SUMOylation assays and Western blotting with the indicated antibodies, as well as RT-PCR for detecting the mRNA of vp1 and gapdh. (E) One-step growth curve of IBDV. DF-1 cells were individually infected with the wild type (WT) and indicated mutant IBDVs at an MOI of 1 at the indicated times, and the TCID50 was detected as described in Materials and Methods. (F) Polymerase activity assays were performed using 293T cells expressing pCDNA3.0-A, together with a minigenome reporter system and pRL-TK in the presence of WT VP1 or the I404C/T or I406C/F mutant. All detection was performed by three independent experiments. Values are means ± SDs.

SUMOylation inhibits the degradation of IBDV polymerase VP1.

Considering that I404C/T and I406C/F VP1 mutants cannot be modified by SUMO1, we further investigated the stability of these VP1 mutants and whether they could be enhanced with ubiquitination. We performed CHX chase experiments during transfection. We demonstrated that all four I404C/T and I406C/F VP1 mutants showed shorter half-lives than WT VP1 (Fig. 6A). And MG132 could remarkably block the degradation of all four mutation VP1 (Fig. 6B). In addition, in contrast to the case with WT VP1, K48-linked and WT ubiquitination levels of all four mutation VP1 were enhanced (Fig. 6C and D). Next, we estimated the half-lives of those VP1 mutants encoded by mutant virus. DF-1 cells infected with mutant IBDV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 for 18 h were collected for immunoblotting at the desired time under CHX treatment. Figure 6E showS that the half-lives of all four IBDV VP1 mutants were significantly shorter than that of WT IBDV VP1. MG132 could significantly inhibit the degradation of IBDV mutant VP1 (Fig. 6F). However, in triple colocalization observations, the VP1 mutants were still colocalized with viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and VP3 in the cytoplasm to form replication complexes in the cells infected with all four mutant IBDVs and WT IBDV (Fig. 6G). Together, our data suggested that mutation of SUMOylation-required sites 404I and 406I of VP1 impaired its stability, although the mutation of 404I and 406I within VP1 did not change VP1’s colocalization with viral dsRNA and VP3.

FIG 6.

Inhibition of IBDV polymerase VP1 degradation by SUMOylation. (A) UnSUMOylated VP1 proteins with I404C/T and I406C/F mutations were unstable. 293T cells individually transfected with Flag-VP1 or its mutations for 24 h and were treated with CHX (100 μg/ml) for 0, 4, 8, and 12 h. (B) Blocking proteasome activity inhibited degradation of unSUMOylated VP1. 293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h and were then treated with MG132 (10 μg/ml) for 8 h. The resultant cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibodies for analyzing the life span of WT VP1 and mutant VP1 (A) and VP1 levels (B) by ImageJ. All detection was performed by three independent experiments. (C and D) Enhanced ubiquitination of unSUMOylated VP1 with I404C/T and I406C/F mutation. 293T cells were transfected with Flag-VP1 or its four mutants and HA-Ub (C) or HA-K48 (D) for 36 h. Lysates of the cells were subjected to ubiquitination assays and Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (E) Low stability of unSUMOylated VP1 during IBDV infection. DF-1 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 1 for 18 h and treated with CHX (100 μg/ml) for 0, 4, 8, and 12 h. (F) Blocking proteasome activity (MG132) inhibited VP1 degradation of unSUMOylated VP1 during IBDV infection. DF-1 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 1 for 18 h and then treated with MG132 (10 μg/ml) and CHX (100 μg/ml) for 8 h. The resultant cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibodies for analyzing the life span of WT VP1 and mutant VP1 (E) and VP1 levels (F) by ImageJ. All detection was performed by three independent experiments. (G) The replication complex assembly of WT and mutant IBDV was not altered. DF-1 cells were infected with WT and mutant IBDV for 12 h. The resultant cells were fixed and incubated with rabbit anti-VP1 antibody, chicken anti-VP3 antibody, and a mouse MAb specific for dsRNA and then reacted with Alexa Fluor 546 anti-rabbit, FITC goat anti-chicken, and Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-mouse IgG as secondary antibodies. DAPI was used to stain the nuclei. Confocal microscope images were taken under a Nikon laser microscope. Scale bars, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

SUMOylation has been found to have an important role in regulating protein function under conditions of physical or other types of stress (28). In the past decade, increasing data have concerned the modification of various viruses by SUMO moieties. However, the involvement of SUMOylation in regulating IBDV replication is not understood. Current knowledge of viral polymerase modified by SUMO molecules is limited to RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) of turnip mosaic virus (29), nonstructural protein 5 (NS5) of dengue virus (DENV) (9), 3D protein of enterovirus 71 (EV71) (8), and polymerase basic protein 1 (PB1) of influenza A virus (30). In the present study, we obtained strong evidence that residues 404I and 406I within SIM3 of VP1, the RdRP of IBDV, are essential for sustaining its SUMO1 modification. Our study first demonstrated that IBDV polymerase VP1 hijacked the cellular SUMOylation system to improve its own replication ability. Notably, the SUMOylation process was reported to occur mainly in the nucleus, and the three-dimensional structure of IBDV VP1 showed that its SIM3 was buried (PDB accession number 2PGG) (31, 32). Since IBDV replicates in the cytoplasm, how SUMO1 modification of IBDV VP1 occurs during IBDV infection is an interesting topic and needs further investigation.

SUMOylation of trans-activation-responsive (TAR) RNA binding proteins protects them from degradation by inhibiting ubiquitination (33). Lysines 70 and 87 of interferon regulatory transcription factor 3 (IRF3) are shared by SUMOylation and K48-linked ubiquitination, which processes compete to regulate the life span of IRF3 (34). In the present study, VP1 with a mutated SIM3 motif, 404IYIV407, was less stable than WT VP1 (Fig. 4A), showing that VP1 SUMOylation maintained its stability. As expected, SUMOylation-deficient VP1 with a mutated SIM3 showed significantly enhanced ubiquitination, especially K48-linked ubiquitination (Fig. 4F). A reasonable explanation is that SUMOylated SIM3 of VP1 maintains the stability of polymerase VP1 by inhibiting K48-linked ubiquitination.

Motif C of RdRp is responsible for initiating RNA elongation (35). Previous studies suggested that the 400YADN403 sequence, the core domain for the polymerase protein, is essential for VP1 polymerase. Mutating D402N led to a lack of catalytic activity of the polymerase (32, 36). However, in the present study, the SIM3 motif 404IYIV407, located in motif C of RdRp VP1, was adjacent to the 400YADN403 sequence; this motif is highly conserved among birnaviruses (Fig. 5A) but is distinct from other viral RdRps, including those of dsRNA viruses, positive-sense single-stranded RNA (ss+RNA) viruses, and retroviruses. Rescuing IBDV with SUMOylation-deficient VP1 further exhibited less stability and replication ability of IBDV with the I404C/T or I406C/F mutation in SIM3 of VP1 than those of wild-type IBDV; regrettably, virus rescue could not be performed with genomic IBDV with the I404R or I406R mutation of VP1 (Fig. 6). These results demonstrated that SUMOylation is critical to the stability of polymerase VP1 and regulates IBDV replication.

Generally, our study demonstrated that the polymerase VP1 of IBDV was SUMOylated during infection. The residues 404I and 406I of SIM3 in motif C of VP1 are required for SUMOylation. SUMOylated VP1 maintained the stability of VP1 by inhibiting K48-linked ubiquitination. Additionally, residues 404I and 406I of VP1 are critical for regulating IBDV replication. These findings not only increased our understanding of SUMOylation modification in regulating the stability of VP1 polymerase of IBDV but also identified a potential target site for designing anti-IBDV drugs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and virus.

Cells of the human embryonic kidney line 293T (China Center for Type Culture Collection) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (1616756; Biological Industries, Israel). Cells of the chicken fibroblast line DF-1 (CRL-12203; ATCC) were also maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS (CCS30010.02; MRC, Australia). All cell lines were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Stably expressed T7 RNA polymerase BSRT cell lines (kindly gift from Jingjing Cao, Shandong University) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 500 μg/ml of G418 for selection. IBDV strain NB was maintained in our laboratory (37). IBDV strain CT was generously provided by Bernard Delmas (27). Both IBDV strains were adapted to replicate efficiently in 293T cells and DF-1 cells.

Plasmid construction and transfection.

The full-length polymerase VP1 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified by PCR and subcloned into the pCMV-Flag-N vector (635688; Clontech, Mountain View, CA). All the mutants of Flag-VP1 and rescue plasmid T7-B were created by site-specific mutation experiments. Myc-SUMO1, Myc-Ubc9, HA-SUMO1, and Flag-Ubc9 expression plasmids were constructed by inserting the corresponding ORF into the pCMV-Myc-N (635689; Clontech), and pCMV-Flag-N and pCMV-HA-N (631604; Clontech) vectors as indicated. Human SENP1 ORF, amplified from 293T cells, was inserted into the pCMV-Myc-N vector. HA-SUMO1GA, Myc-Ubc9CS, and Myc-SENP1CS were constructed by mutation using the WT plasmid as the template. Flag-tagged VP1 (or mutants) infused with Ubc9 plasmid were constructed by overlap PCR. HA-Ub and HA-K48 expression plasmids were kind gifts from Hongbin Shu (College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University). All constructed DNAs were transfected into cells using the ExFect transfection reagent (T101-01/02; Vazyme Biotechnology, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Antibodies and reagents.

Mouse MAbs against HA and Flag were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (H3663 and F1804). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) against Myc (R1208-1), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (EM1101), and β-actin (EM21002) were purchased from Huaan Biological Technology (Hangzhou, China). Rabbit MAb against SUMO1 was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (number 4940; Beverly, MA). The mouse anti-Flag M2 affinity gel was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (A2220). Mouse MAb against dsRNA (J2 clone) was purchased from English & Scientific Consulting Bt (Hungary). Mouse MAbs against IBDV proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3, chicken pAbs against VP3, and rabbit pAbs against VP1were produced by us (37–40). MG132 was purchased from Slleckchem (S2619; USA). N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) and CHX were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (E3876) and Medchemexpress (HY-12320), respectively. Puromycin was obtained from InvivoGene (58-58-2). Western blotting and immunoprecipitation cell lysis buffer NP-40 (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40) was purchased from Beyotime (P0013F; Shanghai, China). The secondary antibodies used in Western blotting (horseradish peroxidase [HRP]-labeled anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG) were purchased from KPL (Millford, MA). Immunofluorescence secondary antibodies were fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (KPL), Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-chicken IgY (Abcam; ab150169), Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, USA), and Alexa Fluor 647-labeled donkey anti-mouse IgG H&L (Abcam; ab150115).

RNA interference.

Two short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences targeting different regions of the chicken Ubc9 mRNA transcript, 5′-GCAGAGGCGTACACAATTTAC-3′ (shUbc9#1) and 5′-GCCAAGAAGTTTGCACCATCA-3′ (shUbc#2), and a control (scramble) shRNA sequence 5′-ACAGGTCAAGCGTGTAGCGTA-3′ (shCon) were synthesized. All the target sequences were inserted into pLVX-U6-puro (Transheep, Shanghai, China) based on the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the target sequence fused with CTCGAG (loop), as well as the reverse complementary sequence of the target sequence, was inserted into pLVX-U6-puro between EcoRI and BamHI. The recombinant plasmids were all sequenced using U6 primer. Two helper plasmids, psPAX2.0 (Addgene; number 12260) and pMD2.G (Addgene; number 12259), were used to produce lentiviruses with three shRNA plasmids for building stable Ubc9 knockdown DF-1 cells by selection with puromycin (1 μg/ml) as described previously (41).

Western blotting.

Cells were lysed with NP-40 buffer containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; protease inhibitor) at 4°C for 10 to 15 min. Protein samples were collected to perform SDS-PAGE and then transferred to the nitrocellulose membranes. Skimmed milk (5%) dissolved phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) was used to block the nonspecific binding sites at 37°C for 30 min. The membranes were washed three to five times with PBST and then reacted with corresponding primary antibodies for 7 to 12 h at 4°C or for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies for 30 min to 1 h at room temperature. Signals were analyzed by enhanced chemiluminescence using the AMI600 system (GE Healthcare, USA).

Immunoprecipitation assays.

To detect interaction between Ubc9 and VP1 in transfected cells, 293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-VP1 and Myc-Ubc9 for 36 h and DF-1 cells were transiently transfected with Flag-Ubc9 for 24 h, and then cells of both types were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 5 for 12 h. The resultant cells was harvested and lysed with NP-40 buffer containing PMSF for 15 to 30 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the supernatants were incubated with anti-Flag M2 affinity gel for 2 to 4 h at 4°C. For Ubc9 interaction with VP1during virus infection, DF-1 cells were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 5 for 12 h and collected for IP with VP1 antibody plus protein A/G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). The fraction complex was washed with NP-40 buffer with three to five times. Prepared protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with corresponding antibodies.

SUMOylation assays.

To detect SUMOylation during transfection, plasmids expressing viral proteins and Myc-Ubc9 were transiently transfected into 293T cells along with HA-SUMO1. At 36 to 48 h posttransfection, the cells were lysed with NP-40 buffer containing PMSF and 20 mM NEM, a deactivator of cysteine proteases, for 15 to 30 min at 4°C and then subjected to IP using anti-Flag M2 affinity gel. Western blotting was performed to detect SUMOylated bands and corresponding proteins.

To detect SUMOylation of VP1 during IBDV infection, DF-1 cells cultured in 60-mm dishes were infected with IBDV at an MOI of 5 at 12 h and then lysed with NP-40 buffer containing PMSF as well as 20 mM NEM. The collected supernatants were immunoprecipitated using VP1 antibodies plus protein A/G (sc-2003; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) and then subjected to immunoblotting using VP1 and SUMO1 antibodies.

Ubiquitination assays.

For ubiquitination assays, plasmids were transfected into 293T cells for 36 h. The cells were then lysed by NP-40 buffer containing PMSF as well as 5 mM NEM and then subjected to immunoprecipitation. The precipitated complexes were subjected to Western blotting using the appropriate antibodies.

IFA and confocal microscopy.

Indirect immunofluorescenc assays (IFA) were carried out according to previously reported methods (40). Briefly, DF-1 cells on a confocal plate (In Vitro Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and penetrated with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min. The fixed cells were incubated with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. To observe the colocalization of viral replication complex formation, DF-1 cells were infected with mutant IBDV for 12 h. IFA and confocal microscopy were performed using the rabbit pAb against VP1, chicken pAb against VP3, and murine MAb against dsRNA as primary antibodies and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-chicken IgY, Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, and Alexa Fluor 647-labeled donkey anti-mouse IgG as the secondary antibodies. The nuclei were then stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Fluorescence signals were scanned using a Nikon A1R/A1 laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Virus rescue.

To detect the role of VP1 SUMOylation in IBDV replication, 404I and 406I mutant viruses were produced by using the IBDV strain CT rescue system. The process of rescuing is briefly described as follows. First, the residues were individually mutated to another amino acids in rescue vector T7-B. Next, T7-A was cotransfected with individual T7-B (or its mutants) into BSRT7 cells (stably expressing the T7 RNA polymerase) for 72 h. T7-A and WT T7-B were cotransfected as a positive control. T7-B was transfected alone as a negative control. The resultant cells were freeze-thawed three times and then centrifuged. The resultant supernatants were inoculated into fresh DF-1 cells and cultured for 48 h. Cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed under a phase-contrast microscope.

One-step growth curve.

Fresh DF-1 cells were individually infected with the WT and mutant IBDV at an MOI of 1. The cells were harvested at the desired times and freeze-thawed three times. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 120,000 × g. Titration of the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) was performed. Briefly, samples were diluted 10-fold using DMEM containing 2% FBS, and then the diluted samples were used to infect fresh DF-1 cells. For each diluted sample, the experiment was carried out for eight repeats. CPEs were recorded as positive.

RT-PCR.

Fresh 293T cells were transfected with plasmids for 36 h. Total cellular RNA was isolated by the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNase I (M0303; New England BioLabs [NEB]) was used to remove DNA. Reverse transcription of 1 μg of total RNA was performed using RevertAid RT reverse transcription kit (K1691; Thermo Fisher, USA). vp1 and gapdh mRNAs were amplified using 2× tag master mix for PAGE (Vazyme Biotechnology; P114-01). The primers for vp1 mRNA were 5′-CACCAAGACCCGGAACATATGGTCA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CAGGTTCATTATCAGGCACGATGAG-3′ (antisense). The primers for gapdh mRNA were 5′-ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCA-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGTGTAGCCCAGGATGCCCTTGAGG-3′ (antisense). The PCR products were separated with a 1% nucleic acid agarose gel, and the images were scanned by SYSTEM GelDoc XR+ (Bio-Rad, USA).

CHX chase assays.

To estimate the life span of VP1, CHX chase experiments were performed. Briefly, the indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells for 24 h. The transfected cells were treated with 100 μg/ml of CHX dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Finally, the cells were collected at different times and subjected to immunoblotting. ImageJ software was used to quantify the protein levels.

Polymerase activity assays.

Polymerase activity was performed as stated in our previous report (42). Briefly, the luciferase reporter gene was flanked between cis-acting replication elements that could be recognized by viral polymerase protein. The expression level of the luciferase gene indicated the polymerase activity. 293T cells were transfected with minigenome, pCDNA3.0-A, and pCDNA3.0-B (or I404C/T mutant or I406C/F mutant). pRL-TK was used as an internal control producing Renilla luciferase for normalizing cell viability and transfection efficiency. At 36 h posttransfection, the transfected cells were harvested, and the luciferase activity was measured using a dual-luciferase reporter kit (DL101-01; Vazyme Biotechnology, Nanjing, China). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis.

The statistical difference analysis was determined using Student’s t test. Results, including CHX assays, virus titers, protein level assessment, and one-step growth curve, are presented as means ± standard deviations. A P value of less than 0.05 was recorded as statistically significant. Means of P values are represented in figures as follows: ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; and ns (nonsignificant), P > 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31630077), the Agriculture Research System of China (grant no. CARS-40-K13), and the National Key Technology R & D Program of China (grant no. 2015BAD12B01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hickey CM, Wilson NR, Hochstrasser M. 2012. Function and regulation of SUMO proteases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13:755–766. doi: 10.1038/nrm3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang J, Yan J, Zhang J, Zhu S, Wang Y, Shi T, Zhu C, Chen C, Liu X, Cheng J, Mustelin T, Feng GS, Chen G, Yu J. 2012. SUMO1 modification of PTEN regulates tumorigenesis by controlling its association with the plasma membrane. Nat Commun 3:911. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gareau JR, Lima CD. 2010. The SUMO pathway: emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11:861–871. doi: 10.1038/nrm3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendriks IA, D’Souza RC, Yang B, Verlaan-de Vries M, Mann M, Vertegaal AC. 2014. Uncovering global SUMOylation signaling networks in a site-specific manner. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21:927–936. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qiu C, Wang Y, Zhao H, Qin L, Shi Y, Zhu X, Song L, Zhou X, Chen J, Zhou H, Zhang H, Tellides G, Min W, Yu L. 2017. The critical role of SENP1-mediated GATA2 deSUMOylation in promoting endothelial activation in graft arteriosclerosis. Nat Commun 8:15426. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker J, Barysch SV, Karaca S, Dittner C, Hsiao HH, Berriel Diaz M, Herzig S, Urlaub H, Melchior F. 2013. Detecting endogenous SUMO targets in mammalian cells and tissues. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:525–531. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hecker CM, Rabiller M, Haglund K, Bayer P, Dikic I. 2006. Specification of SUMO1- and SUMO2-interacting motifs. J Biol Chem 281:16117–16127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Zheng Z, Shu B, Meng J, Zhang Y, Zheng C, Ke X, Gong P, Hu Q, Wang H. 2016. SUMO modification stabilizes enterovirus 71 polymerase 3D to facilitate viral replication. J Virol 90:10472–10485. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01756-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su CI, Tseng CH, Yu CY, Lai MMC. 2016. SUMO modification stabilizes dengue virus nonstructural protein 5 to support virus replication. J Virol 90:4308–4319. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00223-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin DY, Huang YS, Jeng JC, Kuo HY, Chang CC, Chao TT, Ho CC, Chen YC, Lin TP, Fang HI, Hung CC, Suen CS, Hwang MJ, Chang KS, Maul GG, Shih HM. 2006. Role of SUMO-interacting motif in Daxx SUMO modification, subnuclear localization, and repression of sumoylated transcription factors. Mol Cell 24:341–354. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciechanover A. 2015. The unravelling of the ubiquitin system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16:322–324. doi: 10.1038/nrm3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellail AC, Olson JJ, Hao C. 2014. SUMO1 modification stabilizes CDK6 protein and drives the cell cycle and glioblastoma progression. Nat Commun 5:4234. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han Q, Chang C, Li L, Klenk C, Cheng J, Chen Y, Xia N, Shu Y, Chen Z, Gabriel G, Sun B, Xu K. 2014. Sumoylation of influenza A virus nucleoprotein is essential for intracellular trafficking and virus growth. J Virol 88:9379–9390. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00509-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurer C, Berthoux L, Luban J. 2005. Covalent modification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 p6 by SUMO-1. J Virol 79:910–917. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.910-917.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tseng CH, Cheng TS, Shu CY, Jeng KS, Lai MM. 2010. Modification of small hepatitis delta virus antigen by SUMO protein. J Virol 84:918–927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01034-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng XJ, Hong LL, Shi LX, Guo JQ, Sun Z, Zhou JY. 2008. Proteomics analysis of host cells infected with infectious bursal disease virus. Mol Cell Proteomics 7:612–625. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700396-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chevalier C, Galloux M, Pous J, Henry C, Denis J, Da Costa B, Navaza J, Lepault J, Delmas B. 2005. Structural peptides of a nonenveloped virus are involved in assembly and membrane translocation. J Virol 79:12253–12263. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12253-12263.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caston JR, Martinez-Torrecuadrada JL, Maraver A, Lombardo E, Rodriguez JF, Casal JI, Carrascosa JL. 2001. C terminus of infectious bursal disease virus major capsid protein VP2 is involved in definition of the T number for capsid assembly. J Virol 75:10815–10828. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10815-10828.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mundt E, Beyer J, Muller H. 1995. Identification of a novel viral protein in infectious bursal disease virus-infected cells. J Gen Virol 76:437–443. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-2-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Einem UI, Gorbalenya AE, Schirrmeier H, Behrens SE, Letzel T, Mundt E. 2004. VP1 of infectious bursal disease virus is an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Gen Virol 85:2221–2229. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrero D, Garriga D, Navarro A, Rodriguez JF, Verdaguer N. 2015. Infectious bursal disease virus VP3 upregulates VP1-mediated RNA-dependent RNA replication. J Virol 89:11165–11168. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00218-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S, Hu B, Si W, Jia L, Zheng X, Zhou J. 2015. Avibirnavirus VP4 protein is a phosphoprotein and partially contributes to the cleavage of intermediate precursor VP4-VP3 polyprotein. PLoS One 10:e0128828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Everett RD, Boutell C, Hale BG. 2013. Interplay between viruses and host sumoylation pathways. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:400–411. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonne-Andrea C, Kahli M, Mechali F, Lemaitre JM, Bossis G, Coux O. 2013. SUMO2/3 modification of cyclin E contributes to the control of replication origin firing. Nat Commun 4:1850. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao L, Zhou HJ, Zhang H, Qin L, Hwa J, Yun Z, Ji W, Min W. 2015. SENP1-mediated NEMO deSUMOylation in adipocytes limits inflammatory responses and type-1 diabetes progression. Nat Commun 6:8917. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang P, Zhao W, Zhao K, Zhang L, Gao C. 2015. TRIM26 negatively regulates interferon-beta production and antiviral response through polyubiquitination and degradation of nuclear IRF3. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004726. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Da Costa B, Chevalier C, Henry C, Huet JC, Petit S, Lepault J, Boot H, Delmas B. 2002. The capsid of infectious bursal disease virus contains several small peptides arising from the maturation process of pVP2. J Virol 76:2393–2402. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2393-2402.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu MM, Yang Q, Xie XQ, Liao CY, Lin H, Liu TT, Yin L, Shu HB. 2016. Sumoylation promotes the stability of the DNA sensor cGAS and the adaptor STING to regulate the kinetics of response to DNA virus. Immunity 45:555–569. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiong R, Wang A. 2013. SCE1, the SUMO-conjugating enzyme in plants that interacts with NIb, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of turnip mosaic virus, is required for viral infection. J Virol 87:4704–4715. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02828-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pal S, Santos A, Rosas JM, Ortiz-Guzman J, Rosas-Acosta G. 2011. Influenza A virus interacts extensively with the cellular SUMOylation system during infection. Virus Res 158:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myatt SS, Kongsema M, Man CW, Kelly DJ, Gomes AR, Khongkow P, Karunarathna U, Zona S, Langer JK, Dunsby CW, Coombes RC, French PM, Brosens JJ, Lam EW. 2014. SUMOylation inhibits FOXM1 activity and delays mitotic transition. Oncogene 33:4316–4329. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan J, Vakharia VN, Tao YJ. 2007. The structure of a birnavirus polymerase reveals a distinct active site topology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:7385–7390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611599104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C, Zhu C, Huang J, Zhao X, Deng R, Zhang H, Dou J, Chen Q, Xu M, Yuan H, Wang Y, Yu J. 2015. SUMOylation of TARBP2 regulates miRNA/siRNA efficiency. Nat Commun 6:8899. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ran Y, Liu TT, Zhou Q, Li S, Mao AP, Li Y, Liu LJ, Cheng JK, Shu HB. 2011. SENP2 negatively regulates cellular antiviral response by deSUMOylating IRF3 and conditioning it for ubiquitination and degradation. J Mol Cell Biol 3:283–292. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garriga D, Navarro A, Querol-Audi J, Abaitua F, Rodriguez JF, Verdaguer N. 2007. Activation mechanism of a noncanonical RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:20540–20545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704447104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan J, Lin L, Tao YJ. 2009. Self-guanylylation of birnavirus VP1 does not require an intact polymerase activity site. Virology 395:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng XJ, Hong LL, Li YF, Guo JQ, Zhang GP, Zhou JY. 2006. In vitro expression and monoclonal antibody of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase for infectious bursal disease virus. DNA Cell Biol 25:646–653. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.25.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ye C, Jia L, Sun Y, Hu B, Wang L, Lu X, Zhou J. 2014. Inhibition of antiviral innate immunity by birnavirus VP3 protein via blockage of viral double-stranded RNA binding to the host cytoplasmic RNA detector MDA5. J Virol 88:11154–11165. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01115-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu B, Zhang Y, Jia L, Wu H, Fan C, Sun Y, Ye C, Liao M, Zhou J. 2015. Binding of the pathogen receptor HSP90AA1 to avibirnavirus VP2 induces autophagy by inactivating the AKT-MTOR pathway. Autophagy 11:503–515. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1017184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Wu X, Li H, Wu Y, Shi L, Zheng X, Luo M, Yan Y, Zhou J. 2009. Antibody to VP4 protein is an indicator discriminating pathogenic and nonpathogenic IBDV infection. Mol Immunol 46:1964–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao JJ, Lin C, Wang HJ, Wang L, Zhou N, Jin YL, Liao M, Zhou JY. 2015. Circovirus transport proceeds via direct interaction of the cytoplasmic dynein IC1 subunit with the viral capsid protein. J Virol 89:2777–2791. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03117-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu HS, Shi LY, Zhang YN, Peng XR, Zheng TY, Li YH, Hu BL, Zheng XJ, Zhou JY. 2019. Ubiquitination is essential for avibirnavirus replication by supporting VP1 polymerase activity. J Virol 93:e01899-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01899-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]