Flavescence dorée, a threatening disease of grapevine caused by FD phytoplasma (FDp), is distributed within the most important wine-producing areas of Europe and has severe effects on both vineyard productivity and landscape management. FDp is a quarantine pest in Europe, and despite the efforts to contain the pathogen, the disease is still spreading. In this work, new genetic markers for the fine genetic characterization of FDp at local scale are presented. Our findings improve the knowledge of FDp epidemiological cycle and offer the possibility of tracking the route of the FDp infection. In particular, due to its high genetic variability, one of the newly developed markers could be sufficient to track the origin of new infection foci, either from the wild areas or from nurseries.

KEYWORDS: Clematis, Scaphoideus titanus, Vitis vinifera, dnaK, malG, vmpA

ABSTRACT

To study the role of wild areas around the vineyards in the epidemiology of flavescence dorée (FD) and track the origin of new foci, two phytoplasma genetic markers, dnaK and malG, were developed for FD phytoplasma (FDp) characterization. The two genes and the vmpA locus were used to genetically characterize FDp populations at seven agroecosystems of a wine-growing Italian region. Vitis vinifera, “gone-wild” V. vinifera and rootstocks, Clematis spp., and Scaphoideus titanus adults were sampled within and outside the vineyards. A range of genotypes infecting the different hosts of the FDp epidemiological cycle was found. Type FD-C isolates were fairly homogeneous compared to type FD-D ones. Most of the FD-D variability was correlated with the malG sequence, and a duplication of this locus was demonstrated for this strain. Coinfection with FD-C and FD-D strains was rare, suggesting possible competition between the two. Similar levels of FDp genetic variation recorded for grapevines or leafhoppers of cultivated and wild areas and co-occurrence of many FDp genotypes inside and outside the vineyards supported the idea of the importance of wild or abandoned Vitis plants and associated S. titanus insects in the epidemiology of the disease. Genetic profiles of FDp found in Clematis were never found in the other hosts, indicating that this species does not take part in the disease cycle in the area. Due to the robustness of analyses using dnaK for discriminating between FD-C and FD-D strains and the high variability of malG sequences, these are efficient markers to study FDp populations and epidemiology at a small geographical scale.

IMPORTANCE Flavescence dorée, a threatening disease of grapevine caused by FD phytoplasma (FDp), is distributed within the most important wine-producing areas of Europe and has severe effects on both vineyard productivity and landscape management. FDp is a quarantine pest in Europe, and despite the efforts to contain the pathogen, the disease is still spreading. In this work, new genetic markers for the fine genetic characterization of FDp at local scale are presented. Our findings improve the knowledge of FDp epidemiological cycle and offer the possibility of tracking the route of the FDp infection. In particular, due to its high genetic variability, one of the newly developed markers could be sufficient to track the origin of new infection foci, either from the wild areas or from nurseries.

INTRODUCTION

The causal agent of flavescence dorée (FD), flavescence dorée phytoplasma (FDp), is transmitted to grapevines by the Deltocephalinae leafhopper Scaphoideus titanus Ball (1), which is almost monophagous on grapevine (2). Phytoplasmas are plant-pathogenic bacteria belonging to the class Mollicutes that invade the phloem sieve tube elements of the host plants and colonize the bodies of insect vectors. Phytoplasmas are transmitted by leafhoppers, planthoppers, and psyllids and by vegetative propagation of infected plant material. Phytoplasmas are uncultivable and described under the provisional genus “Candidatus Phytoplasma” mainly based on 16S rRNA gene phylogeny. Bois noir phytoplasma (BNp; stolbur group, 16SrXII, “Ca. P. solani” [3]) and FDp (16SrV) are associated with important phytoplasma diseases of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) (4). FDp transmission by the monovoltine leafhopper S. titanus is persistent and propagative (1, 2). The symptoms usually appear a year after the initial infection and consist of leaf yellowing or reddening and downward leaf curling, drying of inflorescences and bunches, and lack of cane lignification (5). Consequently, plant vitality and yields and wine production are severely reduced (6). In Piedmont, the presence of high levels of infective agents and of abundant vector populations in vineyards and surrounding areas has made control of the disease especially difficult. Identification of the ecological components of the FD epidemiological cycle could help in the control of disease spread. A possible approach to evaluate disease dispersal patterns over spatial scales is through analyses of pathogen genetic markers (7). On the basis of sequence and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the 16S rRNA and 16S–23S intergenic spacers, two FDp taxonomic groups were described: 16SV-C and 16SV-D (8). Moreover, sequencing of two nonribosomal loci, secY and rpsC, allowed the identification of three genetic clusters within FDp populations sampled in France and Italy (9). Arnaud and coworkers (10) analyzed the sequences of two other genetic loci, map and deg, and confirmed the existence of three genetic clusters of FDp characterized by different geographical distribution and genetic variability as follows: strain cluster FD1, characterized by low genetic variability and high incidence in southwestern France; strain cluster FD2, including isolates FD-92 and FD-D, with no genetic variability and present in both France and Italy; and strain cluster FD3, comprising FD-C, showing high variability and found only in Italy (10). Both FD-C and FD-D phytoplasmas are found in Piedmont (9). This genetic classification was not sufficiently accurate to describe the genetic variability present at a single agroecosystem. In fact, the low variability of the genetic loci considered until now represented a limit with respect to the study of populations from a small geographical area. In the present study, two new genetic markers for FDp characterization, dnaK and malG, were developed. These two genes, together with the vmpA locus, already described by Renaudin and coworkers (11), were used to genetically characterize the FDp populations at seven agroecosystems in Piedmont. To identify the components of the FD epidemiological cycle and to study the epidemic flow of the disease, V. vinifera, “gone wild” V. vinifera rootstocks (hybrids of V. riparia, V. rupestris, and V. berlandieri) from abandoned vineyards, Clematis spp. (12), and S. titanus were sampled both inside and outside the vineyards. Due to the robustness of analyses using dnaK for discriminating between FD-C and FD-D isolates as well as the high variability of malG sequences, these two markers provide a new tool to study FDp populations and epidemiology on a small geographical scale.

RESULTS

FDp diagnosis.

In order to study the role of wild areas around the vineyards in the epidemiology of flavescence dorée in Piedmont, Italy, the following seven vineyards were selected within the main wine areas of the region: Cisterna d’Asti (CI), Castel Rocchero (CR), CREA-Asti (AS), La Morra (LM), Montà (MO), Paderna (PA), and Portacomaro (PC) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Samples of five categories, including cultivated grapevines (VV), S. titanus from inside each vineyard (ST_IN) and the wild areas bordering the vineyard edge (ST_OUT), Clematis (CL), and wild or abandoned grapevines (WG) from the wild areas surrounding each vineyard, were collected and tested for the presence of FDp by nested PCR driven by a 16SrV phytoplasma-specific primer pair. The distribution of FDp-positive samples for each category at each site is reported in Table 1. In the case of CR, all the collected 19 wild or abandoned grapevines growing nearby were negative for FD presence. Therefore, three cultivated grapevines from neighboring vineyards were sampled as potential external sources of FD (VV_OUT). A total of 41 WG (including the three cultivated grapevines sampled outside the CR vineyard) of 192 samples and 7 CL of 32 samples were positive with respect to FDp diagnosis. All FDp-infected samples were negative with respect to the nested PCR assay aimed at detecting “Ca. P. solani” (bois noir) and “Ca. P. asteris,” phytoplasmas known to infect grapevine in the Piedmont region. At least six FDp-positive samples for each category at each site were further characterized for their genetic variability in the selected target genes.

TABLE 1.

Number of FDp PCR-positive plant and S. titanus samples at each location and percentage of FD-infected samples for each categorya

| Site | No. of FDp PCR-positive plant or S. titanus samples (total no. of samples analyzed) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VV | WG | CL | ST_in | ST_out | |

| CI | 6 (6) | 7 (43) | 0 (1) | 26 (50) | 15 (50) |

| AS | 6 (8) | 6 (19) | 0 (0) | 17 (50) | 14 (50) |

| CR | 26 (33) | 3b (22) | 1 (1) | 18 (50) | 0 (12) |

| LM | 6 (15) | 1 (20) | 4 (13) | 10 (100) | 29 (50) |

| MO | 12 (18) | 7 (21) | 0 (1) | 24 (50) | 29 (50) |

| PA | 9 (11) | 8 (28) | 0 (5) | 6 (100) | 8 (50) |

| PC | 9 (13) | 9 (39) | 2 (11) | 22 (50) | 17 (50) |

| Total (%) | 71.1 | 21.4 | 21.9 | 27.3 | 35.9 |

VV, Vitis vinifera; WG, wild Vitis plants; CL, Clematis spp.; ST_in, S. titanus sampled inside each vineyard; ST_out, S. titanus sampled outside each vineyard.

The samples collected from 19 wild or abandoned grapevines growing nearby the CR vineyard were negative for FD presence. Therefore, three cultivated grapevines in neighboring vineyards were sampled. Those three samples were PCR positive for FDp.

Selection of candidate genes to characterize the genetic diversity of FDp.

The following 17 genes were selected on the basis of their differences in sequence identity (ranging from 87% to 100%) between FD-C (13) and FD-D (14) isolates: dnaK, mntA, nrdF, malG, malF, map, rpoC, rpsE, rsmA, htmp1, htmp2, htmp3, htmp4, htmp5, lolD, glyA, and vmpA. PCR amplification of the 17 genes from total DNA of periwinkle-maintained FD-C (13) and FD-D (14) isolates provided amplicons of the expected sizes for 15 and 17 targets of FD-C and FD-D, respectively. In particular, primers designed on htmp1 and htmp4 failed to amplify their targets from FD-C (Table 2). Those two genes were excluded from further analyses. In preliminary experiments performed on FD-infected grapevine samples collected in 2013, amplification with specific primers designed on the basis of the remaining 15 genes provided amplicons of the expected sizes for most of the genes analyzed. Amplicons from htmp1, htmp2, htmp3, and htmp4 genes were not efficiently amplified from most of the field samples and were consequently excluded from subsequent analysis (Table 2). All the obtained amplicons were sequenced in both directions. Upon sequencing, rpoC and rsmA amplicons provided a single genotype and, due to their low sequence variability, were excluded from further analysis. Among the tested target genes, only malG provided more than two genotypes and, due to this high sequence variability, was selected for FDp characterization. Sequencing of the remaining target genes always provided 2 genotypes, corresponding to the FD-C (13) and FD-D (14) reference isolates. Among these, dnaK was arbitrary selected for further studies. Gene vmpA was also chosen due the adhesion role of VmpA, which could be essential in the colonization of the insect by FDp (15). Those three genes were used for subsequent characterization of FDp from the different geographical sites.

TABLE 2.

List of FDp genes selected for preliminary identification of potential genetic markers to map FDp diversity at each location, based on a set of 13 DNA isolates sampled in Piedmont in 2013 and reference isolates FD-C and FD-D

| Gene name | Gene product name | Primer name | Primer sequence | Amplified fragment length (bp) | Fragment size (bp) | No. of identified genotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dnaK | chaperone protein DnaK | dnaK_F | TTAGGCGGAGGAACTTTCGAC | 559 | 492 | 2 |

| dnaK_R | AAGCTCCCATCGCAACTACT | |||||

| mntA | Mn/Zn ABC transporter solute binding component | mntA_F | GGATCCTTTAATGGGAGTAGG | 554 | 462 | 2 |

| mntA_R | TATTCGCTTCTGTTTGGGTT | |||||

| nrdF | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase 2, beta subunit | nrdF_F | AAAATGCTGTTCACGCTAAA | 541 | 459 | 2 |

| nrdF_R | TAACGGACAAAAGCGTTTAC | |||||

| malG | Probable ABC transporter, permease component | malG_F | GCTTTCCGAGGCCAATTCCA | 496 | 373 | 9 |

| malG_R | ATTCTGGCCAAGCATAAGCG | |||||

| malGtestF | GTCTCAGGAGAAAATAAAAGTGGT | |||||

| malGtestR2 | CTTTCTGGATGTTCTGAAGTTA | |||||

| malGtestR5 | GAAACAGCTACTAAAGCGG | |||||

| malF | Maltose transporter (subunit) | malF_F | TGCTTTAATGATCGCCTTAGCTT | 591 | 510 | 2 |

| malF_R | GCCGCTGTTGTTCCTTTAGC | |||||

| map | Methionine aminopeptidase | map_F | GTTATCAAGGCTTCGGTGGTT | 498 | 435 | 2 |

| map_R | CGGAAGTAACAGCAGTCCAA | |||||

| rpoC | RNA polymerase, beta prime subunit | rpoC_F | AGCTGTCGGAGTAATAGCAGC | 614 | 530 | 1 |

| rpoC_R | GTCGACCTACGGCTAACGAT | |||||

| rpsE | 30S ribosomal subunit protein S5 | rpsE_F | TAGTTCAAGAGACAAAACTAATT | 518 | 417 | 2 |

| rpsE_R | TTGTTTACCTTTAAATCTTGCTATC | |||||

| rsmA | S-Adenosylmethionine-6-N', N'-adenosyl (rRNA) dimethyltransferase | rsmA_F2 | ATAAAAATGTTGTTGAAATCGGTCC | 450 | 372 | 1 |

| rsmA_R2 | CATCAACTTTAGGTTGTGGGAAA | |||||

| htmp1 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein 1 | 1htmp_F | TGACTATTTATGAGGTTTTGG | 500 | 144 | 1a,b |

| 1htmp_R | CCGATAAAGCAAATTAAACCA | |||||

| htmp2 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein 2 | 2htmp_F | TGCATCTGATGAAAAAGAAA | 476 | 393 | 2c |

| 2htmp_R | TGTTTATTACGCCAGTCATTT | |||||

| htmp3 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein 3 | 3htmp_F | TTTTTAAGAAGTGTCGTTTTTG | 475 | 321/312 | 2b |

| 3htmp_R | TCAACAAAATCAACAAGAAAA | |||||

| htmp4 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein 4 | 4htmp_F | TCCGATAGAAAATACGGAAA | 535 | 468 | 1a,c |

| 4htmp_R | GCTCTTGGCAAGGTTTAATA | |||||

| htmp5 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein 5 | 5htmp_F | AAAACAAGAAGAAACGCAAAA | 376 | 260 | 2 |

| 5htmp _R | CCAAGATTCTTCTAAACATTTTAA | |||||

| lolD | Probable ABC transporter ATP-binding component | lolD_F | AAAATTATCCAAGAAAGAAACGA | 760 | 630 | 2 |

| lolD_R | TTCTTAAAATAGGGTGCCAAATT | |||||

| glyA | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | glyA_F | ATTGCTGGATTAATTGTTGC | 501 | 392 | 2 |

| glyA_R | CATTGCTGGAGTTCCTATTC | |||||

| vmpA | Variable membrane protein A | vmpA-F3 | GATGGAAAACAAAATGATAG | 1488/1254 | A/B | 2 |

| vmpA_R | AATAAATCAATAAAAAACTCAC | |||||

| vmpA-F5 | CCTTATCAACTGGATATGGT | |||||

| vmpA-R3 | CTGATGCGTTTAGCCACTTC | |||||

| vmpA-F8 | TTATAGAAATTATTCTCACAA | |||||

| vmpA-R9 | TAAAA(C/A)AGT(C/A)GATAATTCAAC | |||||

No amplification of FD-C reference isolate.

No amplification of field isolates.

No amplification for the majority of field isolates.

Genetic diversity of the selected target genes.

(i) sec-map. Representative samples from the diverse host categories of each location were also characterized on the sequence of the sec-map locus to link the obtained results to existing literature. To provide a starting point for mapping FDp diversity in Piedmont, the genetic diversity of the sec-map locus was measured for the samples representative of each sampling site. A total of 29 samples representative of the seven vineyards were characterized for this locus by the use of the protocol described previously by Arnaud et al. (10) as follows: 7 VV, 6 WG, 8 ST_IN, 2 ST_OUT, and 6 CL. A total of 21 samples in three categories (VV, WG, and ST) had M54 (AM384886; FD-D), and 2 samples (VV) showed M12 (AM384896; FD-C) genotypes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Clematis samples had M50 (LT221945) and M51 (LT221946) genotypes and a third one identical to the FDp found in Clematis in Serbia (KJ911219).

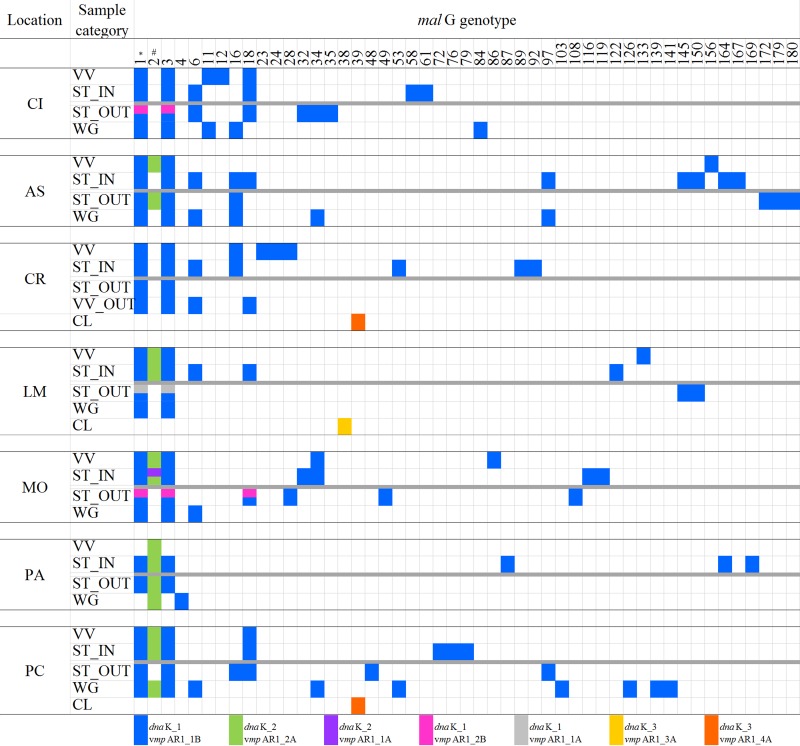

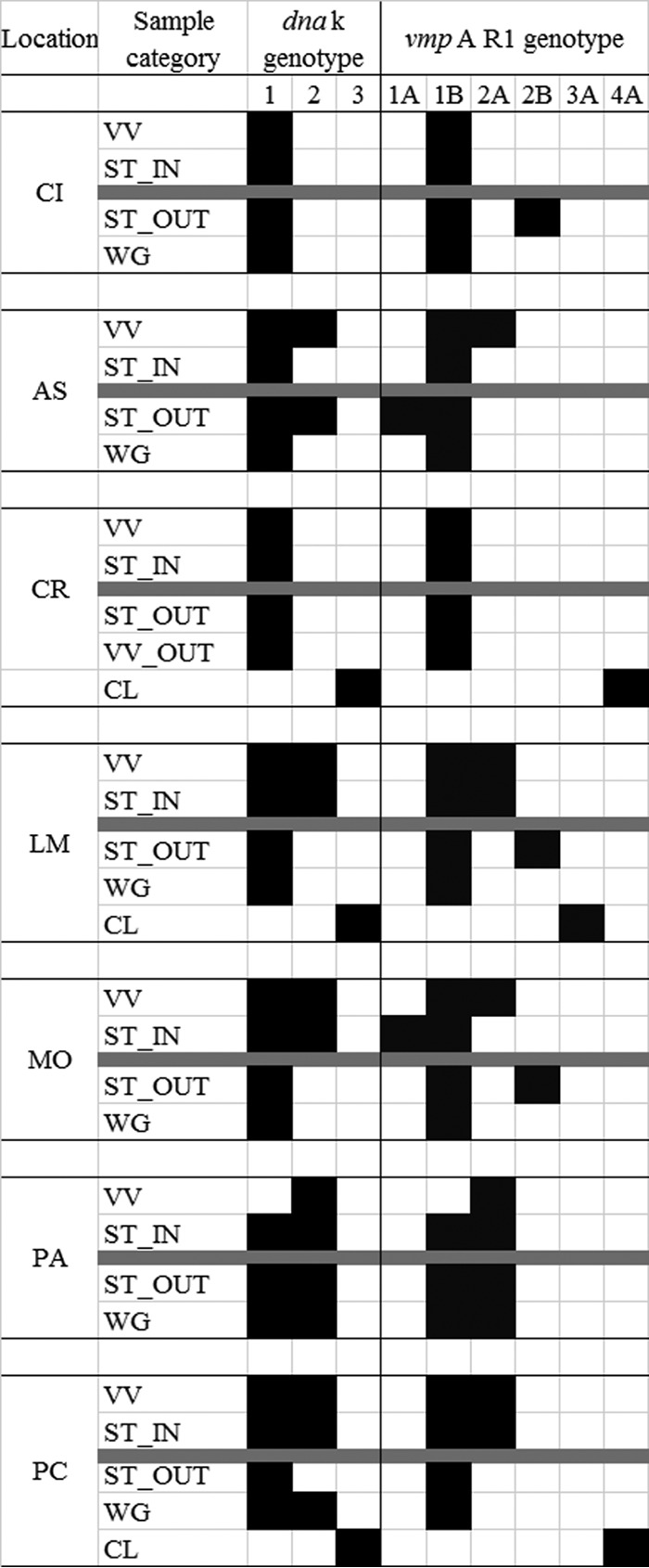

(ii) dnaK and vmpA. Amplification with primers dnaK_F/R produced a specific amplicon of the expected size from 46 cultivated vines, 26 Vitis plants from outside the vineyards, 42 S. titanus samples collected inside the vineyards, and 38 S. titanus samples collected outside the vineyards, as well as the 6 samples of Clematis spp. collected from wild vegetation. A total of 158 dnaK sequences were analyzed, and three dnaK genotypes were identified as dnaK1, dnaK2, and dnaK3. A dnaK1 genotype was found in 116 isolates (73%) and the reference isolate FD92 (FD-D), a dnaK2 genotype was obtained from 36 isolates (23%) and the FD-C reference isolate, and a dnaK3 genotype was obtained from the six Clematis samples (Fig. 1). The dnaK2 genotype differed by three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from the dnaK1 genotype at positions 624, 888, and 969 and by one SNP from dnaK3 at position 789. All the mutations were synonymous (Table 3). Mixed infections were evident from the chromatograms of 7 samples (3 VV, 2 WG, and 2 ST; not shown) from AS, PA, and PC, so PCR amplicons were cloned in plasmid vector pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, WI) for further investigations. Sequencing of five clones for each of the seven samples confirmed double infections with dnaK1 and dnaK2 isolates for all samples. The incidence of dnaK1 was higher than that of dnaK2 for all analyzed sample categories (χ2, P = 0.025). Interestingly, the dnaK1/dnaK2 frequency ratio for VV (1.4) was lower than for WG (3.8), ST_IN (3.6), and ST_OUT (8.3) (not shown).

FIG 1.

Distribution of dnaK and vmpA R1 profiles found among the different sample categories (VV, cultivated V. vinifera, WG, wild or abandoned Vitis plants; CL, Clematis spp.; ST, Scaphoideus titanus) sampled outside (OUT) and inside (IN) the seven analyzed vineyards. Black rectangles indicate “presence” and white ones indicate “absence” of a particular dnaK or vmpAR1 genotype. The gray line separates samples collected inside the vineyards (upper part) from those collected outside (lower part) for each location. CI, Cisterna d’Asti; AS, CREA-Asti; CR, Castel Rocchero; LM, La Morra; MO, Montà; PA, Paderna; PC, Portacomaro. FD-C and FD-92 had dnaK/vmpAR1 profiles 2/2A and 1/1B, respectively.

TABLE 3.

List of SNPs corresponding to each dnaK profile and their locations on the coding sequence, starting from the ATG codon of FD-D dnaK gene (FD92 draft genome) (14)

| Genotype | SNP at position: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 624 | 789 | 888 | 969 | |

| dnaK1 | T | C | T | C |

| dnaK2 | C | C | C | T |

| dnaK3 | C | A | C | T |

The phytoplasma variable membrane protein VmpA gene is characterized by a stretch of 234-nucleotide (nt) repeated sequences (R) (11, 16). Insertion/deletion of one repeat sequence determines the size variability of the gene. Amplification with primers VmpAF3/VmpAR yielded two possible amplicons of 1.488 bp (A) and 1.254 bp (B), respectively. Sequencing of R1 repeats from 158 samples identified two R1 genotypes (R1_1 and R1_2) from all cultivated V. vinifera, wild Vitis plants, and S. titanus from inside and outside the vineyards (Fig. 1). Sequencing of the R1 repeat from the Clematis samples yielded two profiles, named R1_3 and R1_4 (Fig. 1). In summary, taking together information from size polymorphism of the amplicon (A versus B) and R1 sequence profiles (R1_1 to R1_4), 2 and 108 of the 158 sequenced samples showed R1_1A and _1B profiles and 34 and 2 showed R1_2A and _2B profiles, respectively. As for the R1_3 and _4 profiles, these showed only amplicons of the A type (Table 4). Isolates from two samples showed mixed profiles, and four were not amplified under our experimental conditions. The vmpA R1 profiles of the FD-C and FD-D reference isolates were R1_2A and _1B, respectively. The four R1 genotypes differed in their sequences at 26 sites (Fig. S3A), some of which corresponded to nonsilent mutations (Fig. S3B). Profiles corresponding to multiple infections were absent, as shown by analyses of the R1 repeats of the vmpA gene, except for a WG and a ST_OUT, both collected in PA. This plant showed a mixed profile also for the vmpA amplicon size (profiles A and B) and dnaK genotype (dnaK1 and dnaK2). The ST_OUT showing both vmpA amplicon types had a R1_2 profile associated with a dnaK mixed profile. Considering the length of vmpA gene together with R1 sequence and dnaK genotypes, 7 types of dnaK-vmpA profiles were detected and are listed in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Percentages of the different dnaK-vmpA genotype combinationsa

| Genotype | % of vmpA_R1 profile: |

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 1B | 2A | 2B | 3A | 4A | ||

| dnaK1 | 0.7 | 71.1 | 1.3 | 73.1 | |||

| dnaK2 | 0.7 | 22.4 | 23.1 | ||||

| dnaK3 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 3.8 | ||||

| Total | 1.4 | 71.1 | 22.4 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 100 |

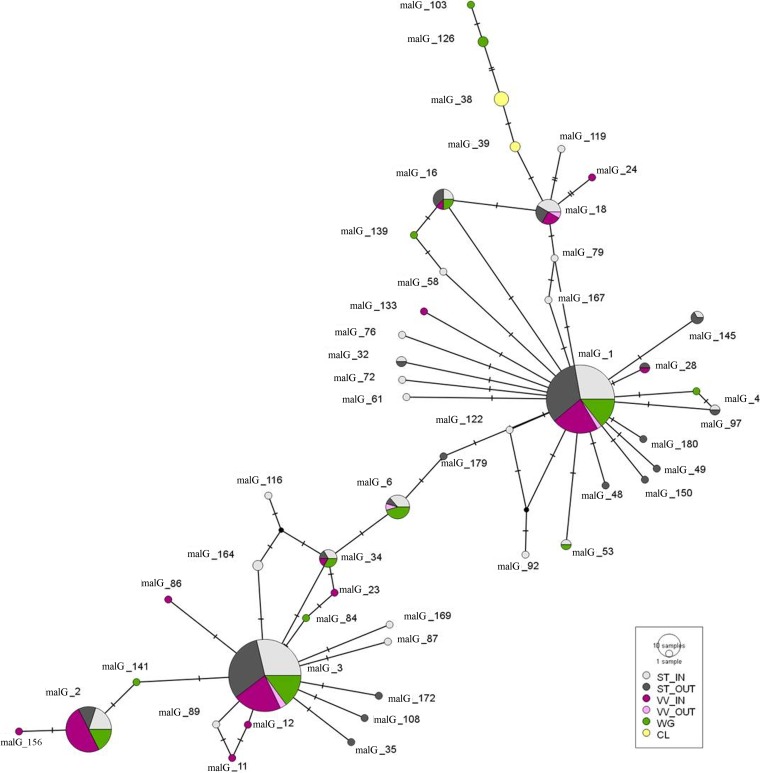

(iii) malG. Partial sequencing of the malG gene detected a mix of divergent sequences in 108 of the 158 analyzed samples. The malG PCR products of these isolates were cloned, and 3 to 5 clones for each sample were sequenced. A total of 447 sequences were then analyzed, and 183 genotypes were detected (Fig. S4). To simplify the successive analyses at each location, the 183 identified genotypes were manually checked and genotypes with SNPs that were present fewer than three times were grouped into the closest node (Fig. 2; see also Fig. 3, Fig. S3, and Table S5). This procedure did not alter the overall picture of the Median-joining networks (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S3) and provided enough sensitivity to cope with the sampling size strategy of the experiment. After this procedure, 50 malG genotypes were left in the list, with malG1 identical to malG of the FD-D isolate (dnaK1 profile), malG2 identical to malG of the FD-C isolate (dnaK2 profile), and malG3 (dnaK1 profile) being the predominant ones (28.2%, 30.4%, and 9.4% of the 447 analyzed sequences, respectively). malG38 and malG39 were identified only in Clematis spp. (dnaK3; sec-map: M50/M51/KJ911219; Fig. 2); malG38 was always associated with vmpA_R1_3A and malG39 with vmpA_R1_4A (Fig. 2). Most (78) of the samples showed multiple profiles, predominantly malG1 and malG3, and among these, 43 samples had more than two malG types. Profiles malG1 and malG3 were found 7 and 11 times as pure profiles, respectively. Type malG2 was found with other malG genotypes in four samples, of which three (1 VV, 1 WG, and 1 St_OUT) had FD-C/FD-D mixed infections and one (WG) had just the dnaK1 (FD-D) profile.

FIG 2.

Distribution of malG profiles found among the different sample categories (VV, cultivated V. vinifera; WG, wild or abandoned Vitis plants; CL, Clematis spp.; ST, Scaphoideus titanus) sampled outside (OUT) and inside (IN) the seven analyzed vineyards. Colored rectangles indicate presence and white ones indicate absence of a particular dnaK-malG-vmpA genotype. The gray line separates samples collected inside the vineyards (upper part) from those collected outside (lower part) for each location. CI, Cisterna; AS, Asti; CR, Castel Rocchero; LM, La Morra; MO, Montà; PA, Paderna; PC, Portacomaro; *, malG profile of FD-92 strain; #, malG profile of FD-C.

FIG 3.

Median-joining network inferred from malG genotypes. Genotypes are represented by circles, and the circle size shows the genotype frequency. Paired genotypes are connected by a line; each SNP mutation is represented by a hatch mark. VV_IN, cultivated grapevines inside the vineyard (purple); VV_OUT, cultivated grapevines in neighboring vineyards (pink); WG, wild Vitis plants (green); CL, Clematis spp. (yellow); ST_IN, Scaphoideus titanus inside the vineyard (light gray); ST_OUT, Scaphoideus titanus outside the vineyard (dark gray).

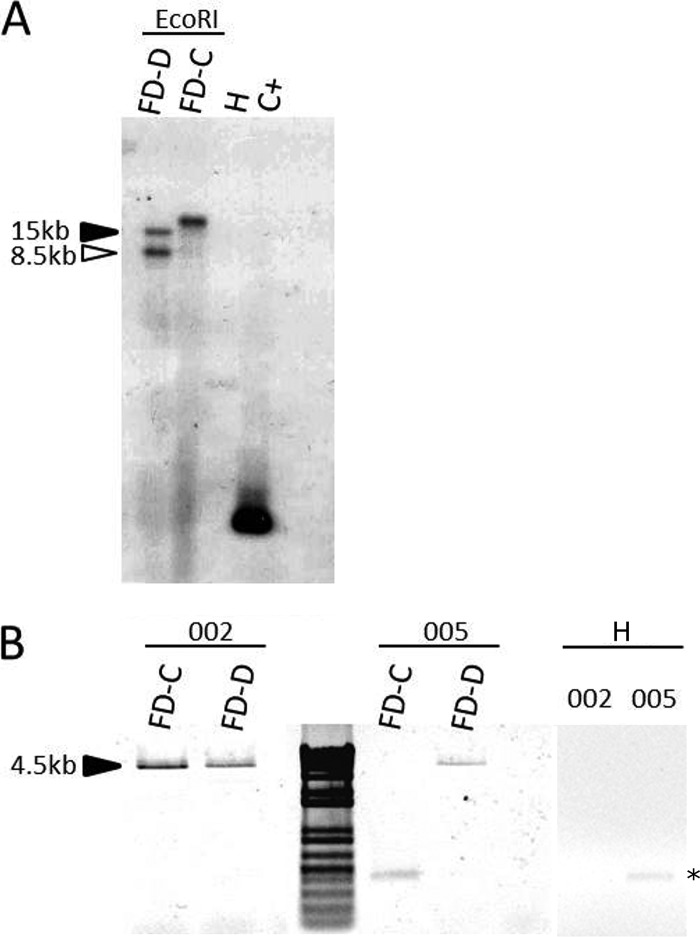

Overall, the frequencies of malG1 and malG3, both associated with the dnaK1 profile, were similar (around 30%), suggesting a possible gene duplication of this gene locus. Southern blotting confirmed the duplication of malG gene in at least the FD92 chromosome (Fig. 4A). Copy-specific PCR amplification confirmed the duplication (Fig. 4B), as primer pair malGtestF/malGtestR2 and malGtestF/malGtestR5 were able to amplify both malG copies from total DNA of the FD-D reference isolate. These primers were designed on the basis of sequences of contigs 002 and 005 of the FD92 draft genome, which included two identical malG1 sequences. Primer malGtestF was designed on the basis of the malG coding sequence, whereas malGtestR2 and malGtestR5 were designed to align downstream of the identical region such that they could amplify specifically contig 002 and 005 sequences, respectively. A single copy of malG (in the context of contig 002) was detected in the chromosome of the FD-C isolate (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

(A) Southern blotting of EcoRI-digested total DNA from FD-C-infected and FD-D-infected and healthy (H) periwinkles probed with a DIG-labeled malG gene amplicon obtained through PCR driven by primer pair malG_F/malG_R (C+, probe positive control represented by pGEM-T-malG1 plasmid). (B) Electrophoresis separation of amplicons obtained following PCR of total DNA from FD-C-infected and FD-D-infected periwinkles with copy-specific primer pairs (002 and 005), according to the draft genome of FD92, and from healthy periwinkle. *, nonspecific PCR product.

Overall, 32 malG types were found in insects, 25 of which were present with less than 2% frequency (Fig. 2). Thirteen malG genotypes were detected in cultivated grapevines and wild-growing Vitis plants, suggesting that the genetic variability of the phytoplasma was lower in the plants than in vectors.

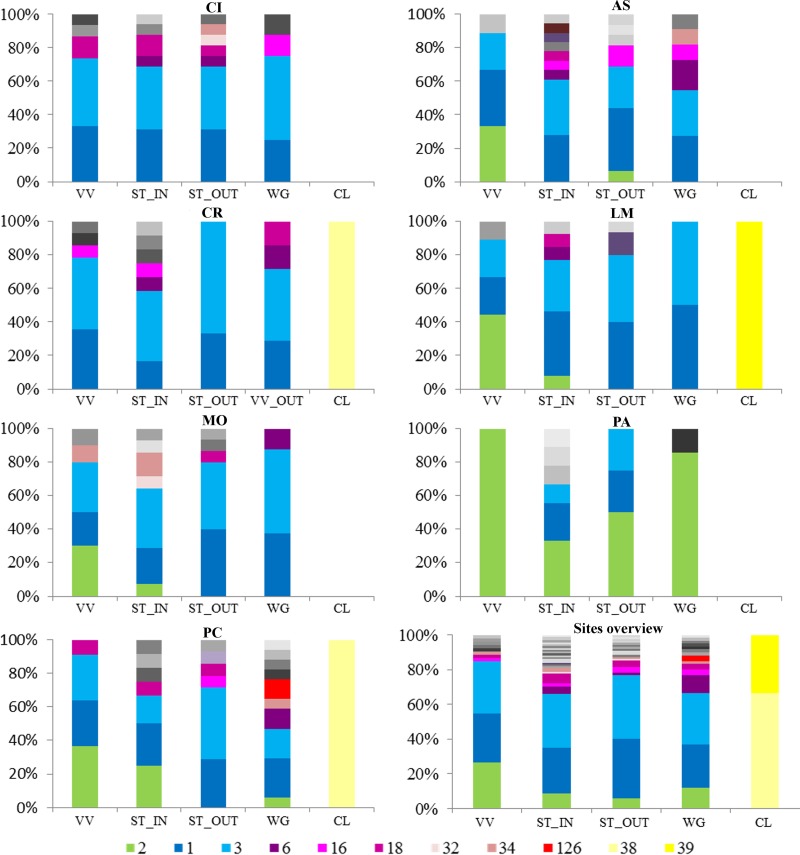

The AS and PC sites, with 15 malG types each, showed the highest genetic variability, which was mainly determined by insect and wild-grapevine isolates (Fig. 2). Six genotypes were identified at PA, which was the site with the lowest variability. This vineyard was also characterized by the prevalence of FD-C (dnaK2, malG2, and vmpA2A) both inside and outside the vineyard.

The levels of DNA sequence identity among the malG genotypes ranged between 99.7% and 97.3%. Among the three most frequent genotypes, only the SNP at position 380 (G to A) determined a nonsynonymous substitution (V127I) (Fig. S6). This was the most frequent mutation and corresponded to a clear distinction between malG1 and malG3 clusters (Fig. S6). A second mutation at position 332, determining a valine-to-leucine substitution, characterized malG38 and explained its relationship with malG103 and malG126 genotypes (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S6) found only in the WG category at PC. A silent T/C mutation at position 629 was found only in isolates from CI.

The Median-joining network analysis of the 50 malG genotypes (Fig. 4) identified the following seven main nodes (on the basis of sequence and frequency): malG1, malG2, malG3, malG6, malG16, malG18, and malG34. In particular, most of the genetic diversity was linked to malG1 and malG3, especially malG1. Eighteen minor genotypes were linked to malG1, 15 of which were found only in insects. Eleven minor genotypes were linked to malG3, and seven of those were found only in insects. Two genotypes were directly linked to malG2 (genotypes 141 and 146). Genotypes malG103 and malG126 were found only in the WG category. Those two genotypes were linked to malG38 of CL, with no direct link to malG genotypes of other sample categories.

Genetic variability of FDp at different sampling sites.

The distributions and frequencies of the most highly represented malG genotypes are reported in Fig. 5. At all locations, several FDp variants were detected, with the exception of PA, where the FDp infection showed low variability. FDp from Clematis spp. was never found in other plant or insect hosts. At most locations, more than three genetic FDp variants were detected within each sample category, but only one and two variants were detected at PA from cultivated and wild grapevines, respectively. At each location, except CR and PC, most genetic variants of FDp were detected in the vectors, within both the vineyard and the nearby wilderness. At each site, the most frequent FDp genotypes were present in all categories except Clematis, although the frequencies could differ. Indeed, at each location where its presence was recorded, malG2 genotypes were more frequently detected from plant hosts than from vectors and from cultivated grapevines than from wild Vitis plants. Due to the lack of dnaK2 profiles at CI and CR, only malG analysis was able to describe FDp variability at these locations, which was comparable to the variability seen with the other sampling sites (Fig. 2). At the remaining locations, dnaK1 and dnaK2 profiles were present both inside and outside the vineyards, irrespective of the sample categories, with the exception of FDp isolates from the Clematis samples, which all showed dnaK3 profiles. Clematis, instead, differed in terms of VmpA profile as follows: R1_3A was obtained from all Clematis samples from the LM site, and R1_4A was obtained from the CR and PC samples.

FIG 5.

Distribution and frequency of the malG genotypes most frequently found among the different categories (VV, cultivated grapevines; WG, wild or abandoned Vitis plants; CL, Clematis spp.; ST, Scaphoideus titanus) sampled outside (OUT) and inside (IN) the seven analyzed vineyards and graphic overview of the recorded overall malG diversity. CI, Cisterna; AS, Asti; CR, Castel Rocchero; LM, La Morra; MO, Montà; PA, Paderna; PC, Portacomaro.

DISCUSSION

The presence of FD in northwestern Italy dates back to 1998 (14), and despite intense control efforts, the disease has spread to the most important viticultural areas of Piedmont. Since the beginning of the epidemics, FD-C was the prevalent strain, whereas the incidence of FD-D was low (9). For this study, a protocol was developed to decipher the genetic variability of FDp strains involved in the epidemics of disease in northwestern Italy. A previously developed genotyping protocol, based on the sequence of the sec-map locus, clearly identified three lineages among FDp isolates from Italy and France (10). The same gene was used also in this study. Genotype M54 was predominant in the seven selected vineyards of the Piedmont region and, together with M12, represented most of the genetic diversity of FDp isolates from vines and insects at the seven sampling sites. Therefore, the genetic variability associated with this locus was not enough to provide detailed molecular typing of FDp at the vineyard scale. Genotyping based on the three newly selected genes identified different degrees of genetic variabilities of FDp in the seven vineyards. In particular, FDp was less variable at PA than at the other sites. Interestingly, this vineyard is located in the area where the first epidemics of FD were spotted in 1998 in the region, and it is geographically isolated from the other six, which, in contrast, form a continuous vineyard landscape. In addition, although characterized by different genetic resolution powers, dnaK, vmpA, and malG always provided consistent results reflecting the presence of mixed infections. Like sec-map, each of them, could, in fact, enable detection of the presence of both FD-C and FD-D in some of the analyzed samples.

According to our genotype analysis, the type FD-C isolates were fairly homogeneous whereas the FD-D types were highly variable. Most of the observed type FD-D variability corresponded to malG sequences. Indeed, a duplication of this locus has occurred, as demonstrated by the analysis of the FD92 draft genome (14) as well as by the results of the PCR and Southern blotting with contig-specific reagents. Even if the malG2 type of FD-C showed no variability at all, our results cannot exclude the presence of a malG duplication also in the FD-C genome, as possible mismatches on the sequence of the contig 5-specific reverse primer could also explain failure of amplification of the malG copy in this context. The poor quality of the FD-C draft genome (13) in that region does not support any of the hypotheses. Yet the malG operon is present as a single copy in most bacterial genomes, and, in particular, in many phytoplasma genomes such as “Ca. P. asteris,” “Ca. P. mali,” and “Ca. P. australiense.” The malG1 and malG3 genotypes showed the highest variability; interestingly, 15 and 7 of the 18 malG1 and 11 malG3 genotypes were found only in insects, indicating that most of the variability was detected in that host. All malG1-derived and malG3-derived types were associated with a dnaK1 profile, and again, this was more abundant in insects than in vines, especially cultivated ones. In contrast, the unique malG2 profile was associated only with the dnaK2 type, which is more abundant in plants, in particular, in cultivated grapevines, than in insects. Infections with different dnaK profiles were rare, especially in vectors, indicating a possible antagonism between the two dnaK genotypes, which is an issue under investigation. Such a high level of genetic variability of FDp, described on a very restricted geographical scale, supports the hypothesis of a European origin of the phytoplasma (10). Interestingly, similar levels of FDp genetic variation were recorded in the cultivated and wild areas for both grapevines and leafhoppers. This finding, together with the co-occurrence of many FDp genotypes inside and outside the vineyards, confirms the importance of wild or abandoned Vitis plants and associated S. titanus insects in the epidemiology of the disease. The large overlap of FDp genotypes in the two environments was confirmed at the single-site level, with the partial exception of the PA site. In that site, very few S. titanus insects from the wild area were found infected, so epidemiology of the disease at that site should be mainly explained by within-vineyard spread (“secondary infection”). At the other sites, FDp genetic diversity was consistent with the hypothesis of “primary infection” by incoming vectors from outside the vineyard. This hypothesis is further supported by the “edge” effect recorded for FDp-infected grapevines (17–19). Primary infections are likely to occur late in the season, when cultivated grapevines are no longer protected by insecticides, due to the need for respecting a safety period before grape harvest (20). Data on S. titanus dispersal capability (21) indicate that 80% of adults do not fly beyond 30 m, although a few can move up to 300 m. In our study, wild or abandoned grapevines and associated S. titanus adults were always collected within that limit.

Lack of transovarial transmission of FDp in S. titanus implies that insects must acquire FDp from plants. The presence of about 50% of the FDp types only in the insects can be explained by latent infection of FDp types in the plant that are able to multiply efficiently only in the vector body and/or by a high variation rate of the FDp population within the vector, which, being persistently infected and hosting an active multiplication of FDp, might act a strong selection pressure with respect to these phytoplasmas. Lack of identification of some FDp types in the plants could have been due to insufficient plant sample sizes, to inefficient multiplication of some FDp types in the plant host, and/or to inefficient transmission of some FDp genotypes. Although other plant species, besides the Vitis ones, are known reservoir hosts of FDp, the genotypes of the phytoplasma identified in the Clematis spp. in the investigated areas were different from those infecting grapevine and S. titanus. In fact, the sec-map types identified in FDp from Clematis in our study were consistent with those described previously by Malembic-Maher et al. (22), i.e., M50 and M51, and the latter were never found in grapevines and vectors. Therefore, we can conclude that, even if Dictyophara europea planthoppers can occasionally transmit Clematis phytoplasmas to grapevine (23), the frequency of such transfer is negligible in the investigated areas. Alder (Alnus spp.) and Ailanthus altissima are also known hosts and potential reservoirs of FDp (24), but they were absent in the vicinity of the analyzed vineyards.

The newly developed protocol, based on the analyses of three loci of the FDp chromosome, provided enough sensitivity to describe the genetic population structure at the vineyard level and to assess the composition of the FDp population within the cultivated and wild areas of seven geographic locations. These results also highlight the importance of both Vitis plants and S. titanus populations in the uncultivated areas nearby productive vineyards in the epidemiology of the disease in the analyzed areas. In particular, a direct consequence of these results would support the idea of an urgent need of an effort aimed at controlling both vectors and Vitis plants of areas surrounding productive vineyards, at least in the form of plant eradication to reduce the FDp reservoir within vector flying distance from cultivated grapevines. Moreover, due to its high genetic variability, malG can be applied to track the origin of new infection foci, either from the wild area or from the nursery. In fact, it is worth noting that, in the presence of the vector, the spread of the disease in previously uninfected areas can be due either to the introduction of infected plant material or to the transfer of FDp phytoplasmas already present in the wild area into the vineyard. According to EFSA (2016) (24), it is likely that emergence of FDp from the wild reservoir has occurred in some European regions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vineyard selection.

For the selection of the sampling sites for FDp along plot edges and surrounding landscape, the following criteria were adopted: (i) presence of actively cultivated Vitis vinifera with plants positive for FDp; (ii) presence of the FDp vector Scaphoideus titanus; (iii) presence of potential alternative host plants (Vitis vinifera, V. riparia, and hybrids of different Vitis species and Clematis vitalba). Following these guidelines, seven sites across the Piedmont region were selected. The sites were named after the villages closest to them using the following abbreviations (defined above): CR, AS, CI, LM, MO, PA, and PC (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Plants, insects, and phytoplasma reference isolates.

Total DNA extracts from FD-infected grapevines sampled in 2013 at representative sites in Piedmont were used for the initial selection of the best candidate genes to characterize the genetic diversity of FDp. For the detailed study of FDp diversity at selected sites, grapevines showing FD symptoms (VV) were collected at each of the vineyards described above during July and August of 2014 and 2015. Representative samples from wild grapevines (including V. vinifera and rootstocks; hybrids of V. riparia, V. rupestris, and V. berlandieri from abandoned vineyards; and hybrids from different Vitis species; WG) as well as C. vitalba (CL) samples were collected in the wild areas around each vineyard site, whenever present. At each site, both asymptomatic samples and samples showing yellows disease were collected, with the aim of testing all potential sources of FDp, irrespective of the expressed symptomatology. Adult S. titanus individuals (ST) were detached from the yellow sticky traps placed inside (ST_IN) and outside (ST_OUT) each vineyard. At one of the sites (CR), no FDp-infected wild grapevines were found, and so symptomatic, cultivated V. vinifera from adjacent/neighboring vineyards (VV_OUT) were collected instead.

Phytoplasma reference isolates FD92 (FD-D) (25) and FD Piedmont (FD-C) (13) were maintained in Catharanthus roseus by grafting of infected scions from the Institute of Sustainable Plant Protection collection (Turin, Italy).

Total DNA extraction and FDp diagnosis.

Total nucleic acids were extracted from 1 g of leaf midribs and petioles and from single leafhoppers according to the method of Pelletier et al. (26, 27). Total DNA extracts from plants and insects were then suspended in 100 μl and 75 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), respectively. DNA concentrations were measured with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), and all samples were then diluted to 20 ng/μl.

To confirm the presence of FDp in single infections, 40 ng of each DNA extract was used in direct PCR assays with the universal ribosomal primers P1/P7 (28, 29), followed by nested PCRs with group-specific ribosomal primers R16(V)F1/R1 (29), as well as R16(I)F1/R1 (29). Samples with FD and BN mixed infections were excluded from the analysis. PCR conditions were as described previously by Lee et al. (1994) (29). Taq DNA polymerase (Polymed) (1 U) was used in each assay. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis through the use of a 1% agarose gel and 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer along with a 1-kb-plus DNA size marker (Gibco BRL). Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized on a UV transilluminator.

Selection of candidate FDp genes, primer design, cloning, transformation, and sequencing.

Seventeen genes (Table 2) were selected on the basis of their differences in sequence identity (ranging from 87% to 100%) between FD-C (13) and FD-D (14) isolates determined by BLASTN. Specific primers able to amplify both FD-C and FD-D genes were designed. PCR was carried out in 30-μl reaction mixtures. Each reaction mixture contained 0.3 U of proofreading DyNAzyme EXT DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The cycling conditions were set as follows: 2 min at 94°C and 35 cycles with 1 cycle consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 40 s at 72°C followed by a final extension of 5 min at 72°C. Obtained amplicons were sequenced in both directions as detailed below. For sequencing purposes, portions of the genes were amplified by PCR with the corresponding primers as listed in Table 2 and sequenced as detailed below. To determine vmpA gene size, PCRs were performed using primers vmpAF3/R (Table 2) in a 30-μl reaction solution under the following cycling conditions: 2 min at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 52°C, and 1 min 30 s at 68°C and a final extension of 5 min at 68°C. PCR products (5 μl) were loaded onto a 1% agarose gel in TBE buffer using FD-C and FD-D vmpA amplicons as size references. To determine the sequence of the vmpA R1 repeat, PCR was performed with primers VmpAF5/R3 (Table 2) under the following conditions: 2 min at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C, and 30 s at 66°C and a final extension of 5 min at 66°C. Direct PCR products (1 μl) were used as the templates for nested PCR with primers VmpAF8/R9 under the following cycling conditions: 2 min at 94°C and 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 50°C, and 30 s at 66°C and a final extension of 5 min at 66°C. Nested PCR products were purified using a DNA Clean and Concentrator kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) and sequenced as detailed below with primer VmpAF3.

In the case of mixed infections (presence of double peaks in the analyzed pherograms from the sequencing of the original PCR amplicon), purified PCR products were ligated into pGEM-T easy cloning vector following the manufacturer's instructions (pGEM-T clone kit; Promega, Madison, WI) and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells by heat shock. Positive colonies were selected by blue/white screening followed by colony PCR using M13F/R primers under the following conditions: 5 min at 95°C and 35 cycles of 60 s at 95°C, 60 s at 51°C, and 1 min and 20 s at 72°C and a final extension of 5 min at 72°C. Recombinant plasmids were extracted using a Wizard SV Plus Minipreps DNA purification system (Promega, Madison, WI). Purified plasmids were sent for sequencing (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea) with appropriate primers for each target gene (Table 2). Each sequence had 2× coverage. All sequences obtained in this study were deposited in NCBI under the accession numbers listed in the “Data availability” paragraph.

Sequence analysis.

Raw sequences were trimmed of the unwanted 5′ and 3′ fragments generally characterized by low sequence quality using BioEdit (30) before further analyses were performed. The reading frames of the sequences were maintained. Sequences from the same gene were aligned with MEGA7 (31), and the MUSCLE algorithm (32) was used for sequence alignments. In the case of malG, only the parsimony-informative sites present at least three times upon sequencing of all samples and cloned plasmids were considered to be significant with respect to defining a new genotype. The other mutations were first subjected to Median-joining network analysis, as detailed below, and then corrected in accordance with the closest node. This procedure underestimated malG variability but did not hamper characterization of FD variability at the required geographical scale (Fig. S1). To study the correlations among the different genotypes, Median-joining network analysis was used. The Median-joining method is more frequently used for construction of networks in cases of intraspecific data than any other phylogenetic analysis method (33).

Southern hybridization.

Southern hybridization was performed following standard procedures (34) using a digoxigenin (DIG) labeling and detection system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Briefly, genomic DNA from C. roseus infected with FD-C and FD-D reference strains was digested with 30 U EcoRI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) overnight at 37°C and then electrophoresed through the use of a 1 % (wt/vol) agarose gel, depurinated, and denatured in denaturing solution for 30 min. The gel was then neutralized in neutralizing solution for 30 min, and the DNA was transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) by capillary action overnight using 10× SSC solution (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). The transferred DNA was fixed to the membrane by UV irradiation. The membrane was prehybridized in 10 ml hybridization buffer (5× SSC, 0.1 % N-lauroylsarcosine [wt/vol], 0.02 % SDS [wt/vol], 1 % blocking solution [Roche, Basel, Switzerland], 600 μg salmon sperm DNA) for 4 h at 65°C. The DIG probe was synthetized using a PCR DIG probe synthesis kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). pGEM-T-malG1 plasmid was used as the template for the amplification performed with the MalG_F/R primer pair. The DIG probe was diluted at 25 ng/ml in 5 ml of hybridization buffer, denatured by boiling (10 min), and incubated with the membrane overnight at 65°C. The membrane was washed twice with 2× SSC–0.1 % SDS for 5 min at room temperature (RT) and twice in 0.5× SSC–0.1 % SDS for 15 min at 65°C. The hybridized probe was then detected using antidigoxigenin antibody (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with CSPD as the chemiluminescent substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The blot was then visualized by exposing an autoradiographic film to chemiluminescence.

Data availability.

Sequence data were submitted to GenBank under the following accession numbers: MH547710 to MH547712 (dnaK1 to dnaK3); MH547713 to MH547747 (malG1 to malG35); MH547748 to MH547793 (malG38 to malG183); MH547894 to MH547896 (vmpA_R1_1 to vmpA_R1_3); MK091396 and MK091397 (mntA1 and mntA2); MK091398 and MK091399 (nrdF1 and nrdF2); MK091400 and MK091401 (malF1 and malF2); MK091402 and MK091403 (map1 and map2); MK091404 (rpoC1); MK091405 and MK091406 (rpsE1 and rpsE2); MK091407 (rsmA1); MK091408 (htmp1_1); MK091409 and MK091410 (htmp2_1 and htmp2_2); MK091411 and MK091412 (htmp3_1 and htmp3_2) MK091413 (htmp4_1); MK091414 and MK091415 (htmp5_1 and htmp5_2); MK091416 and MK091417 (lolD1 and lolD2); and MK091418 and MK091419 (glyA1 and glyA2). The partial sequences of dnaK, vmpA (R1 repeat), and malG were deposited in NCBI under submission identifier (ID) 2121943. Partial sequences of the remaining genes were deposited in NCBI under submission ID 216155.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We especially thank Loretta Panero (CREA-VE) for her support in sample collection.

This work was part of the INTEFLAVI project funded by Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Torino, and Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Asti. M. Rossi and M. Pegoraro were supported by fellowships funded by the grant-making foundations cited above. C. Marzachì and D. Bosco were partially supported by CNR grants on the Short Term Mobility 2015 and 2016 programs, respectively. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03123-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schvester D, Carle P, Moutous G. 1967. Testing susceptibility of vine varieties to (flavescence doree) by means of inoculation by Scaphoideus littoralis Ball. Ann Epiphyties 18:143. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chuche J, Thiery D. 2014. Biology and ecology of the flavescence doree vector Scaphoideus titanus: a review. Agron Sustain Dev 34:381–403. doi: 10.1007/s13593-014-0208-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quaglino F, Zhao Y, Casati P, Bulgari D, Quaglino F, Wei W, Quaglino F. 2013. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma solani’, a novel taxon associated with stolbur- and bois noir-related diseases of plants. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 63:2879–2894. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.044750-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osler R, Carraro L, Loi N, Refatti E. 1993. Symptom expression and disease occurrence of a yellows disease of grapevine in northeastern Italy. Plant Dis 77:496–498. doi: 10.1094/PD-77-0496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caudwell A. 1990. Epidemiology and characterization of flavescence-doree (FD) and other grapevine yellows. Agronomie 10:655–663. doi: 10.1051/agro:19900806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morone C, Boveri M, Giosue S, Gotta P, Rossi V, Scapin I, Marzachi C. 2007. Epidemiology of flaveseence doree in vineyards in northwestern Italy. Phytopathology 97:1422–1427. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-97-11-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coletta HD, Francisco CS, Almeida R. 2014. Temporal and spatial scaling of the genetic structure of a vector-borne plant pathogen. Phytopathology 104:120–125. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-13-0154-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martini M, Murari E, Mori N, Bertaccini A. 1999. Identification and epidemic distribution of two flavescence doree-related phytoplasmas in Veneto (Italy). Plant Dis 83:925–930. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1999.83.10.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martini M, Botti S, Marcone C, Marzachi C, Casati P, Bianco PA, Benedetti R, Bertaccini A. 2002. Genetic variability among flavescence doree phytoplasmas from different origins in Italy and France. Mol Cell Probes 16:197–208. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.2002.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnaud G, Malembic-Maher S, Salar P, Bonnet P, Maixner M, Marcone C, Boudon-Padieu E, Foissac X. 2007. Multilocus sequence typing confirms the close genetic interrelatedness of three distinct flavescence doree phytoplasma strain clusters and group 16SrV phytoplasmas infecting grapevine and alder in Europe. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:4001–4010. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02323-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renaudin J, Beven L, Batailler B, Duret S, Desque D, Arricau-Bouvery N, Malembic-Maher S, Foissac X. 2015. Heterologous expression and processing of the flavescence doree phytoplasma variable membrane protein VmpA in Spiroplasma citri. BMC Microbiol 15:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angelini E, Squizzato F, Lucchetta G, Borgo M. 2004. Detection of a phytoplasma associated with grapevine flavescence dorée in Clematis vitalba. Eur J Plant Pathol 110:193–201. doi: 10.1023/B:EJPP.0000015361.95661.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firrao G, Martini M, Ermacora P, Loi N, Torelli E, Foissac X, Carle P, Kirkpatrick BC, Liefting L, Schneider B, Marzachi C, Palmano S. 2013. Genome wide sequence analysis grants unbiased definition of species boundaries in “Candidatus Phytoplasma”. Syst Appl Microbiol 36:539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carle P, Malembic-Maher S, Arricau-Bouvery N, Desque D, Eveillard S, Carrere S, Foissac X. 2011. ‘Flavescence doree’ phytoplasma genome: a metabolism oriented towards glycolysis and protein degradation. Bull Insectol 64:S13–S14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arricau-Bouvery N, Duret S, Dubrana M-P, Batailler B, Desque D, Beven L, Danet J-L, Monticone M, Bosco D, Malembic-Maher S, Foissac X. 9 February 2018. Variable membrane protein A of flavescence doree phytoplasma binds the midgut perimicrovillar membrane of Euscelidius variegatus and promotes adhesion to its epithelial cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02487-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cimerman A, Pacifico D, Salar P, Marzachi C, Foissac X. 2009. Striking diversity of vmp1, a variable gene encoding a putative membrane protein of the stolbur phytoplasma. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:2951–2957. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02613-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavan F, Mori N, Bigot G, Zandigiacomo P. 2012. Border effect in spatial distribution of flavescence doree affected grapevines and outside source of Scaphoideus titanus vectors. Bull Insectol 65:281–290. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maggi F, Marzachì C, Bosco D. 2013. A stage-structured model of Scaphoideus titanus in vineyards. Environ Entomol 42:181–193. doi: 10.1603/EN12216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maggi F, Bosco D, Galetto L, Palmano S, Marzachì C. 6 January 2017. Space-time point pattern analysis of flavescence doree epidemic in a grapevine field: disease progression and recovery. Front Plant Sci. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosco D, Mori N. 2013. “Flavescence dorée” control in Italy. Phytopathog Moll 3:40–43. doi: 10.5958/j.2249-4677.3.1.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lessio F, Tota F, Alma A. 2014. Tracking the dispersion of Scaphoideus titanus Ball (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) from wild to cultivated grapevine: use of a novel mark-capture technique. Bull Entomol Res 104:432–443. doi: 10.1017/S0007485314000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malembic-Maher S, Salar P, Filippin L, Carle P, Angelini E, Foissac X. 2011. Genetic diversity of European phytoplasmas of the 16SrV taxonomic group and proposal of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma rubi’. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 61:2129–2134. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.025411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filippin L, Jovic J, Cvrkovic T, Forte V, Clair D, Tosevski I, Boudon-Padieu E, Borgo M, Angelini E. 2009. Molecular characteristics of phytoplasmas associated with flavescence doree in clematis and grapevine and preliminary results on the role of Dictyophara europaea as a vector. Plant Pathol 58:826–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2009.02092.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeger M, Bragard C, Caffier D, Candresse T, Chatzivassiliou E, Dehnen-Schmutz K, Gilioli G, Miret JAJ, MacLeod A, Navarro MN, Niere B, Parnell S, Potting R, Rafoss T, Rossi V, Urek G, Van Bruggen A, Van Der Werf W, West J, Winter S, Bosco D, Foissac X, Strauss G, Hollo G, Mosbach-Schulz O, Gregoire JC; EFSA Panel on Plant Health (PLH). 9 December 2016. Risk to plant health of flavescence doree for the EU territory. EFSA J. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malembic-Maher S, Constable F, Cimerman A, Arnaud G, Carle P, Foissac X, Boudon-Padieu E. 2008. A chromosome map of the flavescence doree phytoplasma. Microbiology 154:1454–1463. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/013888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelletier C, Salar P, Gillet J, Cloquemin G, Very P, Foissac X, Malembic-Maher S. 2009. Triplex real-time PCR assay for sensitive and simultaneous detection of grapevine phytoplasmas of the 16SrV and 16SrXII-A groups with an endogenous analytical control. Vitis 48:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boudon-Padieu E, Bejat A, Clair D, Larrue J, Borgo M, Bertotto L, Angelini E. 2003. Grapevine yellows: comparison of different procedures for DNA extraction and amplification with PCR for routine diagnosis of phytoplasmas in grapevine. Vitis 42:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider B, Cousins MT, Klinkong S, Seemuller E. 1995. Taxonomic relatedness and phylogenetic positions of phytoplasmas associated with diseases of faba bean, sunnhemp, sesame, soybean, and eggplant. J Plant Dis Prot 102:225–232. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee IM, Gundersen DE, Hammond RW, Davis RE. 1994. Use of mycoplasmalike organism (MLO) group-specific oligonucleotide primers for nested-PCR assays to detect mixed-MLO infections in a single host-plant. Phytopathology 84:559–566. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-84-559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall TA. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 41:95–98. http://jwbrown.mbio.ncsu.edu/JWB/papers/1999Hall1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Rohl A. 1999. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 16:37–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1990. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data were submitted to GenBank under the following accession numbers: MH547710 to MH547712 (dnaK1 to dnaK3); MH547713 to MH547747 (malG1 to malG35); MH547748 to MH547793 (malG38 to malG183); MH547894 to MH547896 (vmpA_R1_1 to vmpA_R1_3); MK091396 and MK091397 (mntA1 and mntA2); MK091398 and MK091399 (nrdF1 and nrdF2); MK091400 and MK091401 (malF1 and malF2); MK091402 and MK091403 (map1 and map2); MK091404 (rpoC1); MK091405 and MK091406 (rpsE1 and rpsE2); MK091407 (rsmA1); MK091408 (htmp1_1); MK091409 and MK091410 (htmp2_1 and htmp2_2); MK091411 and MK091412 (htmp3_1 and htmp3_2) MK091413 (htmp4_1); MK091414 and MK091415 (htmp5_1 and htmp5_2); MK091416 and MK091417 (lolD1 and lolD2); and MK091418 and MK091419 (glyA1 and glyA2). The partial sequences of dnaK, vmpA (R1 repeat), and malG were deposited in NCBI under submission identifier (ID) 2121943. Partial sequences of the remaining genes were deposited in NCBI under submission ID 216155.