Many motile bacterial populations form surface-attached biofilms in response to specific environmental cues, including osmotic stress in a range of natural and host-related systems. However, cross talk between bacterial osmosensing, swimming, and biofilm formation regulatory networks is not fully understood. Here, we report that the pleiotropic regulator LrhA in Pantoea alhagi is involved in the regulation of flagellar motility, biofilm formation, and host colonization and responds to osmotic upshift. We further show that this sensing relies on the EnvZ-OmpR two-component system that was known to detect changes in external osmotic stress. The EnvZ-OmpR-LrhA osmosensing signal transduction cascade is proposed to increase bacterial fitness under hyperosmotic conditions inside the host. Our work proposes a novel regulatory mechanism that links osmosensing and motile-sessile lifestyle transitions, which may provide new approaches to prevent or promote the formation of biofilms and host colonization in P. alhagi and other bacteria possessing a similar osmoregulatory mechanism.

KEYWORDS: LrhA, OPGs, OmpR, Rcs phosphorelay, biofilm, exopolysaccharides, motility, osmosensing

ABSTRACT

Adaptation to osmotic stress is crucial for bacterial growth and survival in changing environments. Although a large number of osmotic stress response genes have been identified in various bacterial species, how osmotic changes affect bacterial motility, biofilm formation, and colonization of host niches remains largely unknown. In this study, we report that the LrhA regulator is an osmoregulated transcription factor that directly binds to the promoters of the flhDC, eps, and opgGH operons and differentially regulates their expression, thus inhibiting motility and promoting exopolysaccharide (EPS) production, synthesis of osmoregulated periplasmic glucans (OPGs), biofilm formation, and root colonization of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Pantoea alhagi LTYR-11Z. Further, we observed that the LrhA-regulated OPGs control RcsCD-RcsB activation in a concentration-dependent manner, and a high concentration of OPGs induced by increased medium osmolarity is maintained to achieve the high level of activation of the Rcs phosphorelay, which results in enhanced EPS synthesis and decreased motility in P. alhagi. Moreover, we showed that the osmosensing regulator OmpR directly binds to the promoter of lrhA and promotes its expression, while lrhA expression is feedback inhibited by the activated Rcs phosphorelay system. Overall, our data support a model whereby P. alhagi senses environmental osmolarity changes through the EnvZ-OmpR two-component system and LrhA to regulate the synthesis of OPGs, EPS production, and flagellum-dependent motility, thereby employing a hierarchical signaling cascade to control the transition between a motile lifestyle and a biofilm lifestyle.

IMPORTANCE Many motile bacterial populations form surface-attached biofilms in response to specific environmental cues, including osmotic stress in a range of natural and host-related systems. However, cross talk between bacterial osmosensing, swimming, and biofilm formation regulatory networks is not fully understood. Here, we report that the pleiotropic regulator LrhA in Pantoea alhagi is involved in the regulation of flagellar motility, biofilm formation, and host colonization and responds to osmotic upshift. We further show that this sensing relies on the EnvZ-OmpR two-component system that was known to detect changes in external osmotic stress. The EnvZ-OmpR-LrhA osmosensing signal transduction cascade is proposed to increase bacterial fitness under hyperosmotic conditions inside the host. Our work proposes a novel regulatory mechanism that links osmosensing and motile-sessile lifestyle transitions, which may provide new approaches to prevent or promote the formation of biofilms and host colonization in P. alhagi and other bacteria possessing a similar osmoregulatory mechanism.

INTRODUCTION

In nature, bacteria employ various adaptive strategies to cope with changing environments (1–3). Notably, many bacteria are able to develop two different lifestyles, the planktonic mode (characterized by single motile cells) and the biofilm mode (characterized by sessile multicellular communities that are attached to each other and a surface) (4, 5). While the transition between motile and sessile lifestyles of bacteria is crucial for their ecological success, complex regulatory networks are integrated to achieve the control of the motile-sessile switch in response to a variety of environmental signals, including nutrient availability, oxygen, temperature, salinity, metal ions, calcium, and phosphate (6–10). Although considerable efforts are being made to understand the link between environmental signals and bacterial endogenous regulatory pathways that govern the lifestyle switch, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown.

Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) are gaining more and more attention because of their increasing agronomic importance (11–13). PGPB are reported to induce beneficial effects on plant growth via a variety of mechanisms, such as improving nutrient absorption, preventing pathogen attack, and increasing tolerance to abiotic stresses (14, 15). The rhizosphere is a critical interface between plants and their associated soil environment and thus the primary site of complex plant-microbe interactions (16, 17). PGPB recruited from the soil are widely known to offer benefits to plants in the rhizosphere, while some root surface colonizers are able to transcend the endodermis barrier and establish endophytic populations (10, 18). Efficient colonization and persistence on/within plant roots is considered a prerequisite for bacterium-mediated improvement of crop performance (10, 19). While chemotaxis, motility, and adhesins, such as exopolysaccharides (EPS) and cell surface proteins, are well-known bacterial traits involved in the colonization of plant root surface, plant polymer-degrading enzymes have been shown to play a role in the colonization of the root interior by endophytic bacteria (20, 21). In addition, functions relevant for rhizosphere competence and/or plant colonization also include efficient iron acquisition, detoxification, and degradation of organic compounds, secretion systems, and signaling systems (10, 20, 22).

For both animal- and plant-associated bacteria, biofilm formation has evolved as an adaptive strategy to achieve host colonization as well as to establish beneficial or antagonistic interactions with their host (23, 24). While biofilm formation is a complex multistage process under the control of a variety of cell surface components and regulators, the inverse regulation of EPS production and motility appears to be widely conserved during both initiation of biofilm formation and dispersal of preformed biofilms (10, 25). In general, flagellum formation is turned off and EPS production is turned on during the switch from planktonic to biofilm growth, whereas biofilm dispersal is preceded by decreased EPS production and increased flagellar motility (23, 25, 26). Accordingly, the bacterial second messenger cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP) has been widely demonstrated to be involved in the regulation of EPS biosynthesis, flagellar motility, and the transition from the motile to the sessile/biofilm state (4, 5, 23). In addition, a wide array of regulatory factors such as BolA (26), CsgD (27), and CsrA (28) in Escherichia coli and quorum-sensing systems in Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN (22) have been shown to control the transition between planktonic and biofilm lifestyles through playing a dual role in the control of biofilm EPS production and flagellar activity. Moreover, some regulators have been shown to modulate the formation of biofilms in response to environmental cues. For instance, a previous study by Guimarães et al. (29) demonstrated that the transcription factor BigR functions as a thiol-based redox switch that enables biofilm growth of the plant pathogens Xylella fastidiosa and Agrobacterium tumefaciens under hypoxia conditions. Under conditions of phosphate starvation, the Pst-PhoR-PhoB phosphate control system activates the expression of the phosphodiesterase RapA and thus results in biofilm dispersal in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 (7). Despite the significant progress that has been made with recent studies, in most cases, the regulatory mechanisms by which the environmental inputs control bacterial biofilm development have yet to be elucidated.

LrhA is a LysR-type transcriptional regulator that is conserved in Proteobacteria and is of pleiotropic function in enterobacteria (30–32). LrhA in Escherichia coli and its homologues in other enterobacteria, named HexA, PecT, and RovM, have been found to be involved in important cellular processes such as motility, biofilm formation, virulence, acid resistance, antibiotic resistance, lipase production, and aromatic compound catabolism (32–34). In E. coli, LrhA represses the transcription of flhDC, encoding the motility master regulator, and also regulates biofilm formation and expression of type 1 fimbriae (32, 35). LrhA activates expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement and enterohemolysin genes and is important in the control of pathogenicity in enterohemorrhagic E. coli (31, 36). LrhA in Pantoea stewartii was reported to play a positive role in the regulation of virulence, while PecT/HexA in Erwinia chrysanthemi controls EPS synthesis and represses virulence (32, 37). In Yersinia species, RovM has been shown to repress virulence by directly inhibiting transcription of the global virulence regulator RovA (38, 39). Interestingly, RovM seems to regulate biofilm production in a species-dependent manner, enhancing biofilm production in Yersinia pestis while repressing biofilm formation in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis YPIII (39, 40). Furthermore, in contrast to LrhA in E. coli, RovM in Y. pseudotuberculosis YPIII enhances motility by activating the transcription of flhDC (40). Taken together, LrhA and its homologues are apparently pleiotropic regulators and seem to play differential roles in different bacterial species.

Recently, we identified an endophytic bacterium, Pantoea alhagi LTYR-11Z, with the ability to colonize the root system of wheat and enhance its resistance to drought stress (41). We have also identified several colonization-related genes, among which the FruR/Cra regulator was found to regulate the colonization ability of P. alhagi in response to carbon source availability (10). In this study, we found that the transcriptional regulator LrhA of P. alhagi also plays a crucial role in the colonization of plants. Our results suggest that LrhA inversely regulates biofilm formation and motility by directly activating the transcription of the eps operon but directly repressing the transcription of flhDC. In addition, we identified the opgGH operon as a novel target of LrhA and thus propose an osmoregulated periplasmic glucan (OPG)-mediated mechanism for LrhA regulation of biofilm formation and motility. Furthermore, we show that LrhA is a transcription factor regulated by OmpR and thus controls the motile-sessile switch and the root colonization process in response to the changes in osmolarity. Collectively, our findings unravel a novel mechanism of regulation by which LrhA links environmental osmolarity to host colonization and shed light on the largely unresolved pleiotropic roles of LrhA in host-microbe interactions.

RESULTS

Reciprocal regulation of P. alhagi biofilm formation and swimming motility by LrhA.

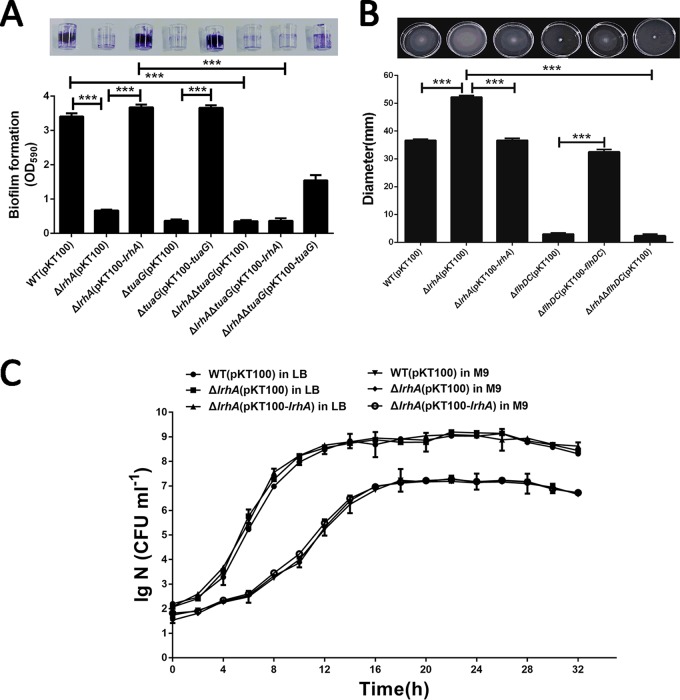

Genes involved in the regulation of motility and biofilm formation have been identified as important colonization factors in plant-associated bacteria, including P. alhagi (10, 21, 23). Since LrhA homologues in enterobacteria have been shown to be pleiotropic regulators involved in the regulation of motility and biofilm formation (32, 40), we sought to determine whether LrhA plays a regulatory role in motility and biofilm formation in P. alhagi. A chromosomal lrhA deletion mutation (ΔlrhA) was generated in the wild-type (WT) P. alhagi LTYR-11Z. The ΔlrhA mutant strain showed a dramatic reduction in biofilm formed on an abiotic surface compared with the WT strain, while complementation with an lrhA-expressing plasmid (pKT100-lrhA) restored the biofilm formation capacity of the mutant to the WT level (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, swimming motility assays showed that the ΔlrhA mutant was much more motile than were the WT and complemented strains (Fig. 1B). Nevertheless, the growth of the ΔlrhA mutant and the complemented strain in both LB and M9 media was similar to that of the WT strain (Fig. 1C), indicating that the phenotypic alterations in biofilm formation and swimming motility were not caused by differences in growth rates. Collectively, these results show that the LysR-type regulator LrhA is a positive regulator of biofilm formation and a negative regulator of swimming motility in P. alhagi.

FIG 1.

LrhA promotes biofilm formation and inhibits swimming motility in P. alhagi. (A) Biofilm formation by the WT, mutant, and complemented strains was displayed with crystal violet staining (top) and quantified with optical density measurement. (B) The swimming motility of the indicated strains was tested in 0.3% agar tryptone plates, and the diameters of swimming zones were measured (top). (C) Growth curves of the indicated strains in LB and M9 media at 30°C. Data are shown as means ± standard deviations (SD) from three experiments. ***, P ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t test). lg N (CFU ml−1) refers to the log10 number of CFU per ml.

LrhA is required for attachment and endophytic colonization of wheat roots by P. alhagi.

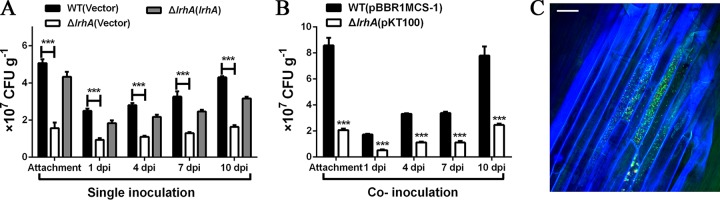

Since LrhA is involved in the regulation of motility and biofilm formation in P. alhagi, we hypothesized that loss of lrhA might also affect the ability of P. alhagi to colonize the host plant. Root attachment assays showed that the number of ΔlrhA mutant bacteria attached to the wheat root surface was significantly lower than that of the WT strain (Fig. 2A). We further compared the endophytic colonization capacities of ΔlrhA mutant and the WT strain in the internal root tissues of wheat. As shown in Fig. 2A, the ΔlrhA mutant showed a >2-fold decrease in the number of endophytic cells compared with the WT strain at 1, 4, 7, and 10 days postinoculation (dpi), and complementation of lrhA partially restored the colonization defects of the ΔlrhA mutant. In addition, the ΔlrhA mutant carrying the plasmid pKT100 (kanamycin resistant [Kmr]) was also tested in competition assay with the WT strain carrying the plasmid pBBR1MCS-1 (chloramphenicol resistant [Cmr]). When the ΔlrhA mutant with pKT100 and the WT strain with pBBR1MCS-1 were inoculated together at a 1:1 ratio, the numbers of ΔlrhA mutant cells adhering and colonizing wheat root tissues were significantly lower than those of the WT strain (Fig. 2B). Similar results were also observed when the ΔlrhA mutant carrying pBBR1MCS-1 and the WT strain carrying pKT100 were used in the competition assay (data not shown). Furthermore, a cocolonization competition assay was performed with the ΔlrhA mutant carrying pKT100-mCherry and the WT strain carrying pKT100-GFPmut3*. After 15 h of exposure to mCherry-labeled ΔlrhA mutant and green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled WT at a 1:1 proportion, confocal microscopy analysis revealed that the wheat roots were predominantly colonized by the WT strain (Fig. 2C). Similar results were also observed when the ΔlrhA mutant carrying pKT100-GFPmut3* and the WT strain carrying pKT100-mCherry were used in the confocal microscopy analysis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Taken together, these data demonstrated that LrhA is a colonization factor of P. alhagi.

FIG 2.

The P. alhagi lrhA gene is required for attachment and endophytic colonization of wheat roots. (A) Attachment and endophytic colonization of wheat roots by WT, ΔlrhA mutant, and complemented strains. The indicated strains were inoculated separately into wheat roots. (B) Competition between the WT strain containing pBBR1MCS-1 and the ΔlrhA mutant containing pKT100 for attachment and endophytic colonization of wheat roots. The two strains were coinoculated at a 1:1 ratio in wheat roots. Data are shown as means ± SD from three independent experiments. ***, P ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t test). (C) Confocal microscopy analysis of the competition between the GFP-labeled WT and the mCherry-labeled ΔlrhA mutant for wheat root attachment after 15 h of incubation. A 1:1 mixture of the two strains was used for inoculation. The GFP-labeled WT cells and mCherry-labeled ΔlrhA mutant cells are visible in green and red, respectively, and the wheat root cells stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) are visible in blue. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Identification of genes regulated by LrhA.

To identify genes that exhibit LrhA-dependent regulation in P. alhagi, the transcriptomes of the ΔlrhA mutant and the WT strain were analyzed using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) in three replicates after cultures were grown to late-exponential phase in LB medium. Compared to the WT results, 35 genes were downregulated and 31 genes were upregulated over 1-fold (log2) (P < 0.05) in the ΔlrhA mutant (Table S1). Thirteen genes, including 5 upregulated, 3 unchanged, and 5 downregulated genes, were randomly selected for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis, which proved the reliability of the RNA-seq data (Fig. S2). Consistent with our swimming motility assay results, the mRNA levels of the flhDC operon (B1H58_15860 and B1H58_15865) encoding the motility master regulator were significantly upregulated in the ΔlrhA mutant (Table S1). In contrast, an eps operon (B1H58_14485 to B1H58_14530) involved in EPS production and biofilm formation (10) was significantly downregulated in the ΔlrhA mutant, suggesting the positive regulation of EPS production by the LrhA protein. Interestingly, a gene (B1H58_19985) encoding glucan biosynthesis glucosyltransferase H (OpgH) involved in the biosynthesis of osmoregulated periplasmic glucans (OPGs) (42) was also significantly downregulated in the ΔlrhA mutant. Since OPGs in the periplasmic space have been shown to be a part of the signal transduction pathway involved in motility and biofilm formation in bacterial pathogens and symbionts (42–44), we hypothesized that LrhA may also modulate swimming motility and biofilm formation through the OPG-mediated signaling pathway.

LrhA promotes EPS production and biofilm formation via transcriptional activation of the eps operon.

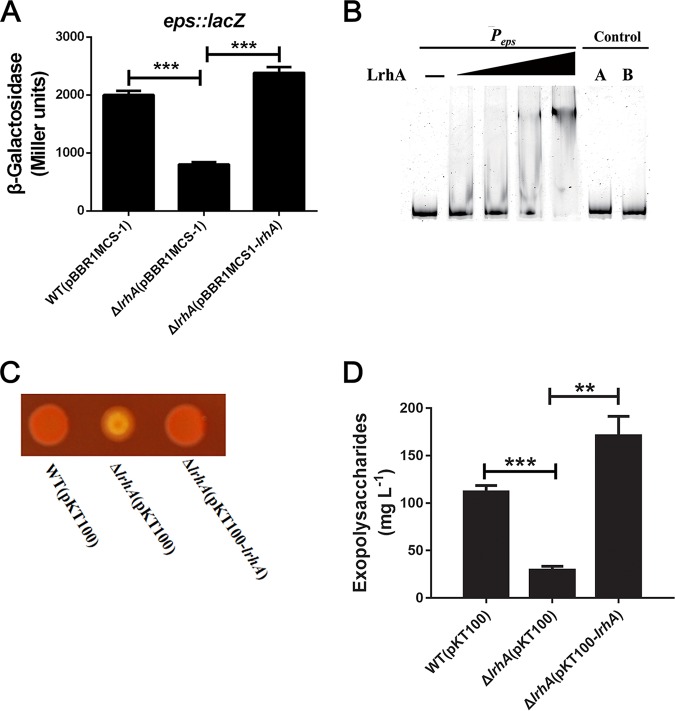

Comparative transcriptome analysis showed that nine genes of the eps operon (B1H58_14485 to B1H58_14530) were significantly downregulated in the ΔlrhA mutant (Table S1), suggesting that LrhA positively regulates the transcription of the eps operon. Expression of the eps operon was investigated using a chromosomal Peps::lacZ transcriptional fusion reporter analysis. As shown in Fig. 3A, the deletion of lrhA significantly reduced the activity of the eps promoter, which was fully restored by complementation with the plasmid pBBR1MCS1-lrhA, confirming that the eps operon was positively regulated by LrhA. Furthermore, an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) indicated that the purified His6-LrhA bound to a 450-bp promoter region of the eps operon (positions −1 to −450 relative to the ATG start codon of B1H58_14485) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 to 5). In contrast, a control DNA amplified from the coding region of B1H58_14485 did not show detectable lrhA binding (Fig. 3B, lane 6), suggesting specific binding and direct transcriptional regulation of the eps operon by LrhA.

FIG 3.

LrhA promotes EPS production by positively regulating the expression of the eps operon. (A) β-Galactosidase activity of the eps promoter in the indicated strains. Strains were grown in LB medium. (B) EMSA was performed to analyze interactions between His6-LrhA and the eps promoter. Increasing amounts of LrhA (0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.2 μg) and 30 ng DNA probe were used. As negative controls, a 450-bp fragment from the wza (B1H58_14485) coding region instead of the eps promoter (control A) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) instead of His6-LrhA (control B) were included in the binding assays. A total of 1.2 μg of LrhA protein was added to the control A, and the same amount of BSA protein was added to the control B. (C) CR-binding assays of the WT, ΔlrhA mutant, and complemented strains. (D) EPS quantification of the indicated strains. **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t test).

We examined EPS production in the WT, ΔlrhA mutant, and complemented strains. Colonies of the ΔlrhA mutant showed weaker staining with Congo red (CR) dye than with the WT and complemented strains, suggesting that the reduced EPS production was due to the deletion of lrhA (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the results of EPS quantification showed that the amount of EPS produced in the ΔlrhA mutant was 3-fold lower than that in the WT strain, and complementation of lrhA restored EPS production to a level higher than that of the WT strain (Fig. 3D). These results clearly demonstrated that LrhA promotes EPS production in P. alhagi. Consistent with our previous findings that EPS production is important for biofilm formation in P. alhagi (10), deletion of the lrhA gene and the tuaG gene (B1H58_14500) within the eps operon both led to a significant reduction in biofilm formation (Fig. 1A). Moreover, complementation of lrhA eliminated the biofilm formation defects of the ΔlrhA mutant but failed to restore the biofilm formation ability of the ΔlrhA ΔtuaG double mutant (Fig. 1A). Taken together, these results suggest that LrhA plays a crucial role in biofilm formation by directly regulating the expression of the eps operon.

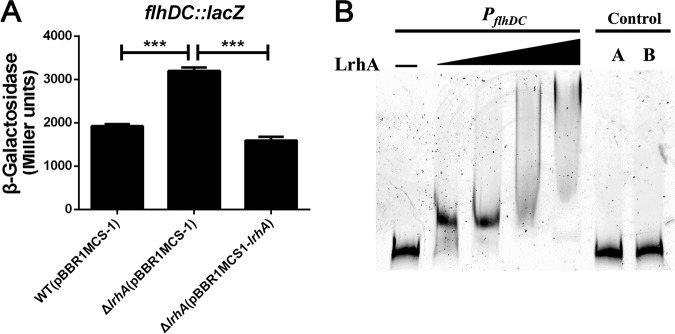

LrhA suppresses motility by directly binding to the flhDC promoter.

The mRNA levels of the flhDC operon (B1H58_15860 and B1H58_15865), which encodes flagellar master regulator FlhD4C2, were significantly higher in the ΔlrhA mutant, suggesting that LrhA serves as transcriptional inhibitor of the flhDC operon. In agreement with the RNA-seq results, the lacZ fusion reporter assay revealed that the PflhDC promoter activity in the ΔlrhA mutant was significantly higher than that in the WT and complemented strains (Fig. 4A), supporting the negative regulatory role of LrhA in flhDC expression. Moreover, the EMSA showed that incubation of His6-LrhA with a 447-bp promoter region (positions −61 to −507) of the flhDC operon led to the formation of protein-DNA complexes in a protein concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 to 5), whereas replacing the flhDC promoter probe with a partial coding region of the opgH gene abolished the LrhA-DNA association (Fig. 4B, lane 6), proving the direct binding of His6-LrhA to the flhDC promoter. These results suggest that LrhA negatively regulates flhDC expression by directly binding to the flhDC promoter. Consistent with the master regulatory role of FlhD4C2 in flagellar biosynthesis and motility (10, 40), there was no motility observed in the ΔflhDC mutant or the ΔlrhA ΔflhDC double mutant (Fig. 1B). Collectively, these data indicate that LrhA might inhibit swimming motility by controlling the expression of flhDC.

FIG 4.

LrhA negatively regulates the expression of flhDC. (A) β-Galactosidase activity of the flhDC promoter in the indicated strains that were grown to stationary phase in LB medium. ***, P ≤ 0.001. (B) LrhA (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μg) EMSA of the flhDC promoter probe (−61 to −507) (30 ng). A 447-bp fragment from the opgH coding region instead of the flhDC promoter and 4 μg of LrhA protein were used in control A, while BSA (4 μg) instead of LrhA was used in control B.

LrhA enhances expression of the opgGH operon involved in the regulation of motility and biofilm formation.

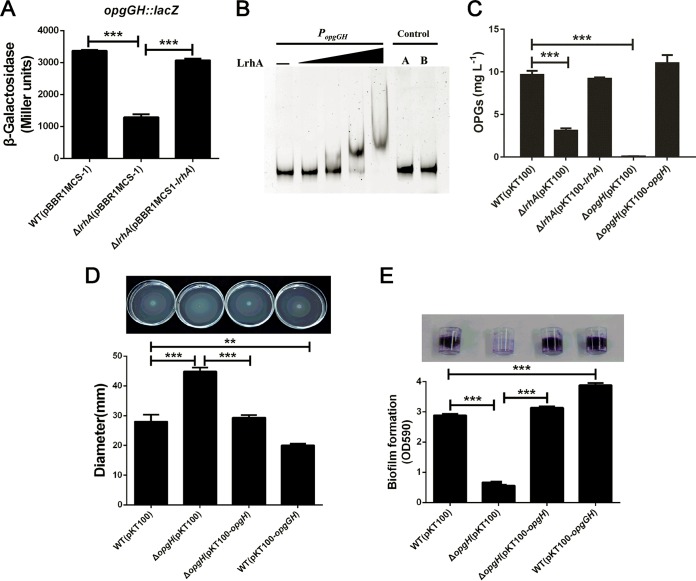

Because the opgGH operon required for the synthesis of OPGs has been reported to be involved in motility and biofilm formation in a variety of Gram-negative bacteria (42, 44, 45), we sought to determine whether LrhA regulates motility and biofilm formation by altering the expression of the opgGH operon in P. alhagi. The RNA-seq results in our study showed that the opgH gene was downregulated −2.07-fold (log2) (P < 0.05; Table S1), while the opgG gene was downregulated approximately −0.74-fold (log2) (P < 0.05; data not shown) in the ΔlrhA mutant. To verify the regulatory role of LrhA in expression of the opgGH operon, chromosomal PopgGH::lacZ fusion reporter analysis was performed. As shown in Fig. 5A, the deletion of lrhA significantly reduced the activity of the opgGH promoter, which was fully restored upon complementation. In addition, EMSA analysis showed that the purified His6-LrhA protein bound specifically to the opgGH promoter probe (positions −1 to −346) in vitro (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that the opgGH operon is positively and directly regulated by LrhA in P. alhagi. Furthermore, we quantified the concentrations of OPGs in the WT, ΔlrhA and ΔopgH mutant, and complemented strains. As expected, while nearly no OPGs could be detected in the ΔopgH mutant, deletion of the lrhA gene also resulted in significantly reduced OPG production (Fig. 5C). The defect in the biosynthesis of OPGs could be fully restored by complementation (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that LrhA could positively regulate the synthesis of OPGs by transcriptional activation of the opgGH operon in P. alhagi.

FIG 5.

LrhA positively regulates the expression of opgGH, which is required for the synthesis of OPGs involved in the regulation of motility and biofilm formation. (A) β-Galactosidase activity of the opgGH promoter in the indicated strains grown to stationary phase in LB medium. (B) LrhA (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 1.0 μg) EMSA of the opgGH promoter probe (−1 to −346) (30 ng). A 346-bp fragment from the flhC coding region instead of the opgGH promoter and 1.0 μg of LrhA protein was added to control A. The same amount of BSA was used in control B. (C) Quantification of OPGs in the indicated strains. (D) The swimming motility of WT, ΔopgH mutant, the ΔopgH/opgH complemented, and the WT/opgGH opgGH-overexpressing strains was tested, and the diameters of swimming zones were measured (top). (E) Biofilm formation by the WT, ΔopgH mutant, ΔopgH/opgH, and WT/opgGH strains displayed with crystal violet staining (top) and quantified with optical density measurement. **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

Then, we sought to determine whether the synthesis of OPGs is involved in the regulation of motility and biofilm formation in P. alhagi. Compared with the WT and complemented strains, the ΔopgH mutant was much more motile but severely affected in biofilm formation (Fig. 5D and E). In addition, the opgGH-overexpressing strain carrying the plasmid pKT100-opgGH exhibited reduced motility and increased biofilm formation (Fig. 5D and E), further confirming that the opgGH operon plays a role in positive regulation of biofilm formation and negative regulation of swimming motility in P. alhagi. Together, these data indicate that LrhA can also promote biofilm formation and inhibit motility by directly regulating the expression of the opgGH operon involved in the biosynthesis of OPGs in P. alhagi.

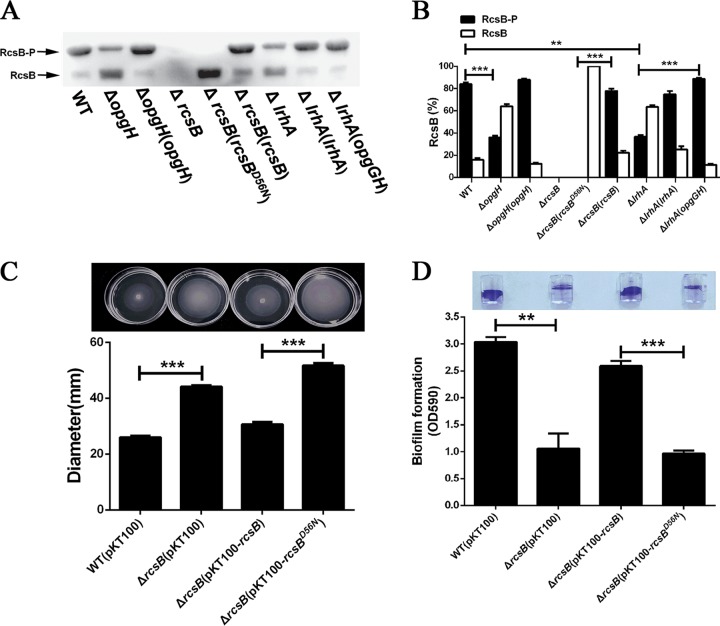

OPGs modulate biofilm formation and motility via control of the phosphorylation status of RcsB.

Previous studies have shown that the regulatory role of OPGs in biofilm formation and motility could be attributed to its control of the Rcs phosphorelay (42, 46, 47). In this study, we compared the levels of in vivo phosphorylation of RcsB in the WT, mutant, and complemented strains using a Phos-tag retardation gel approach. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, a high level of phosphorylated RcsB (RcsB-P) (84%) but a small amount of unphosphorylated RcsB (16%) were detected in the WT strain. In the ΔopgH mutant strain, however, a significantly decreased amount of RcsB-P (36%) and a significantly increased amount of unphosphorylated RcsB (64%) were observed compared to the WT and complemented strains. In good agreement, the deletion of lrhA also led to significantly reduced phosphorylation of RcsB, which was fully rescued by complementation (Fig. 6A and B). Moreover, overexpression of opgGH in the ΔlrhA mutant restored the phosphorylation status of RcsB to the WT level (Fig. 6A and B). Thus, these results show that a high concentration of OPGs could activate the Rcs phosphorelay pathway.

FIG 6.

OPGs regulate biofilm formation and motility by controlling the phosphorylation level of RcsB. (A) Separation of RcsB-P from unphosphorylated RcsB in the indicated strains in vivo by Phos-tag SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. The results presented are representative of three independent experiments performed. (B) Quantification of the ratio of RcsB-P or unphosphorylated RcsB to the total RcsB in the indicated strains. The data reported are the averages of the results from three independent experiments. (C) The swimming motility of the WT, ΔrcsB mutant, ΔrcsB/rcsB and ΔrcsB/rcsBD56N strains was tested, and the diameters of swimming zones were measured (top). (D) Biofilm formation by the WT, ΔrcsB mutant, ΔrcsB/rcsB, and ΔrcsB/rcsBD56N strains displayed with crystal violet staining (top) and quantified with optical density measurement. **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

Next, we determined whether changes in the levels of phosphorylated RcsB influence motility and biofilm formation in P. alhagi. While no RcsB was detected in the ΔrcsB mutant and high levels of RcsB-P were observed in the WT strain and the ΔrcsB/rcsB complemented strain, unphosphorylated RcsBD56N was detected in the ΔrcsB mutant complemented with rcsBD56N, in which nucleotides encoding the phosphorylation site Asp56 were substituted with those encoding an Asn residue (Fig. 6A and B). The ΔrcsB/rcsB and ΔrcsB/rcsBD56N strains produced similar RcsB protein levels but showed a significant difference in the phosphorylation status of RcsB in vivo (Fig. 6A and B). As expected, the ΔrcsB mutant was more motile but formed biofilm at significantly lower levels than the WT strain and the ΔrcsB/rcsB complemented strain (Fig. 6C and D). Compared to the ΔrcsB/rcsB strain, the ΔrcsB/rcsBD56N strain formed biofilm at a significantly lower level but exhibited significantly higher motility (Fig. 6C and D), further supporting the idea that increased phosphorylation of the RcsB regulator enhances biofilm formation and suppresses motility.

In several enterobacteria, such as Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli, it was shown that activation of the RcsCD-RcsB system enhances EPS production by positive transcriptional regulation of colanic acid biosynthesis and decreases motility by repressing expression of the flhDC operon (44, 48, 49). We have previously predicted the putative colanic acid biosynthetic gene cluster (B1H58_14465 to B1H58_14645) involved in EPS production and biofilm formation in the genome of P. alhagi LTYR-11Z (10). Therefore, the relationship between OPGs and the Rcs phosphorelay was further investigated by comparing the expression of the flhDC operon and the eps operon located in the putative colanic acid gene cluster in the WT, ΔopgH and ΔrcsB mutant, and complemented strains. As shown in Fig. S3A and B, deletion of both opgH and rcsB significantly reduced the activity of the eps promoter but led to significantly increased activity of the flhDC promoter, and such alterations could be eliminated by complementation. In contrast, complementation with rcsBD56N failed to restore the Peps and PflhDC promoter activities of the ΔrcsB mutant to WT levels (Fig. S3A and B). These results were in agreement with the phenotypes of motility and biofilm formation in the WT, mutant, and complemented strains (Fig. 5D and E and 6C and D). Together, these data suggest that OPGs might regulate biofilm formation and motility through control of the phosphorylation status of RcsB in P. alhagi.

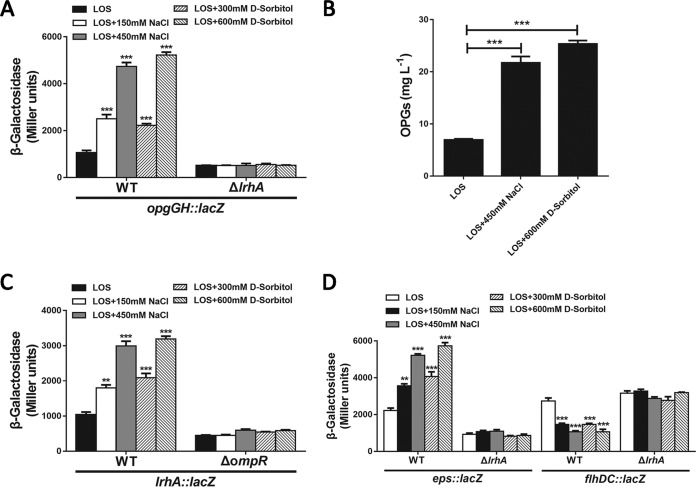

Osmoregulated expression of the opgGH, eps, and flhDC operons is mediated by LrhA.

Transcription of the opgGH operon is found to be osmoregulated in diverse bacterial species (45, 46, 50). To determine if the expression of opgGH in P. alhagi is in response to environmental osmolarity, we measured opgGH transcript levels by qRT-PCR from cultures grown to exponential phase in low-osmolarity (LOS) medium and LOS medium supplemented with NaCl (150 and 450 mM) or sorbitol (300 and 600 mM). As shown in Fig. S4A, the expression of opgG and opgH was markedly induced by supplementation of NaCl or sorbitol in the LOS medium. Moreover, the activity of the PopgGH promoter in LOS medium with added NaCl or sorbitol was significantly higher than in LOS medium (Fig. 7A). As no significant difference was observed in the growth rates when the WT strain was grown in LOS medium and LOS medium supplemented with NaCl or sorbitol (Fig. S4B), we compared the OPG concentrations of the WT strain cultured in these media. Consistent with osmolarity-dependent expression of opgGH, the concentration of OPGs in LOS medium with 450 mM NaCl or 600 mM sorbitol increased more than 3-fold compared with that observed in LOS medium (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that in P. alhagi, the concentration of the OPGs increases as the medium osmolarity increases.

FIG 7.

LrhA regulation is modulated by osmotic stress. (A) β-Galactosidase activities of the opgGH promoter in the WT strain and the ΔlrhA mutant grown in the indicated media. (B) Quantification of OPGs in the WT strain grown in LOS medium and LOS medium supplemented with NaCl (450 mM) or sorbitol (600 mM). (C) β-Galactosidase activities of the lrhA promoter in the WT strain and the ΔompR mutant grown in the indicated media. (D) β-Galactosidase activities of the eps and flhDC promoters in the WT strain and the ΔlrhA mutant grown in the indicated media. **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

The finding that both environmental osmolarity and the regulator LrhA are involved in transcriptional regulation of the opgGH operon raises questions regarding whether LrhA and osmotic stress regulation are linked in P. alhagi. Interestingly, both qRT-PCR (Fig. S4C) and chromosomal PlrhA::lacZ fusion reporter analyses (Fig. 7C) showed that the expression of lrhA is significantly higher in LOS medium with added NaCl or sorbitol than in LOS medium. The observations that hyperosmotic stress stimulates the expression of both lrhA and opgGH and LrhA is a transcriptional activator of opgGH strongly suggest that LrhA regulates the expression of opgGH in response to osmotic stress. Consistent with this suggestion, the deletion of lrhA completely abolished the hyperosmolarity-induced upregulation of the opgGH operon (Fig. 7A). In addition, the Peps promoter activity in LOS medium was significantly increased, whereas the PflhDC promoter activity was significantly suppressed by supplementation of NaCl or sorbitol, and these responses were abolished by deletion of lrhA (Fig. 7D), supporting the role of LrhA in differential regulation of the eps and flhDC operons in response to environmental osmolarity. Altogether, these data indicate that the expression of the opgGH, eps, and flhDC operons is differentially regulated by osmotic stress, which is mediated by the osmoregulated transcription factor LrhA.

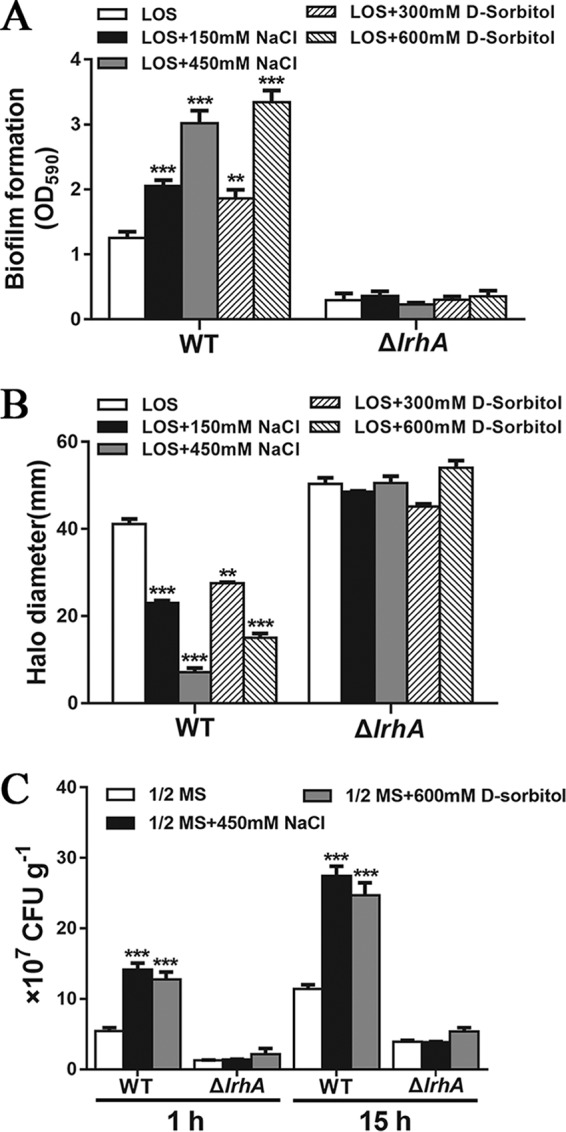

Effect of osmotic stress on biofilm formation, motility, and plant colonization abilities of P. alhagi.

As LrhA transcriptionally activates the expression of the opgGH and eps operons but inhibits the expression of flhDC in response to environmental osmolarity, we further sought to determine whether osmotic stress affects biofilm formation, motility, and root attachment of P. alhagi. While increased medium osmolarity promoted the formation of biofilm in the WT strain, no significant difference was detected in the amount of biofilm formed by the ΔlrhA mutant using LOS medium with or without added NaCl (150 and 450 mM) or sorbitol (300 and 600 mM) (Fig. 8A). In contrast, swimming motility assays using LOS medium with or without added NaCl or sorbitol as the base medium with 0.3% agar showed that the WT strain exhibits decreased motility as the medium osmolarity increases, and the effect of osmotic stress in suppressing motility was completely abolished by deleting the lrhA gene (Fig. 8B). These observations indicate that LrhA inversely regulates biofilm formation and motility in response to osmotic stress. Subsequently, root attachment assays were performed using the WT strain and the ΔlrhA mutant in half-strength MS medium and half-strength MS medium supplemented with NaCl (450 mM) or sorbitol (600 mM). After 1 and 15 h of incubation, the number of WT cells attached in the presence of NaCl or sorbitol was more than 2-fold higher than that in the medium without added NaCl or sorbitol. However, the number of ΔlrhA cells attached in the presence of NaCl or sorbitol was similar to that in the medium without added NaCl or sorbitol (Fig. 8C). Altogether, these data suggest that LrhA could regulate biofilm formation, motility, and plant colonization ability of P. alhagi in response to environmental osmolarity.

FIG 8.

Osmoregulation of biofilm formation, motility, and root attachment by P. alhagi. (A) Biofilm formation by the WT strain and the ΔlrhA mutant grown in the indicated media. (B) Swimming motility of the WT strain and the ΔlrhA mutant grown in the indicated media with 0.3% agar. (C) Attachment of wheat roots by the WT strain and the ΔlrhA mutant after 1 and 15 h of incubation in 1/2 MS medium supplemented with 450 mM NaCl or 600 mM sorbitol. Data are shown as means ± SD of the results from three independent experiments. **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

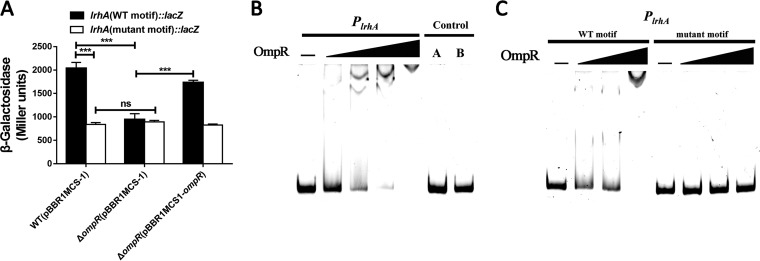

OmpR positively regulates lrhA expression in P. alhagi.

The finding that the expression of the lrhA gene increases in response to the elevation of medium osmolarity raises questions regarding how osmotic stress regulates its expression. Since the EnvZ-OmpR two-component system is well known to mediate osmotic stress response in Gram-negative bacteria (47), we hypothesized that the transcription of lrhA may be regulated by OmpR in P. alhagi. To test this hypothesis, we compared the activities of the lrhA promoter between the ΔompR mutant and the WT strain. As predicted, the deletion of ompR significantly reduced the activity of the lrhA promoter, which was partially restored upon complementation (Fig. 9A). Furthermore, the deletion of ompR completely abolished the hyperosmolarity-induced upregulation of lrhA (Fig. 7C), supporting the role of OmpR in regulation of lrhA expression in response to osmotic stress. In addition, EMSA analysis showed that the purified His6-OmpR protein bound specifically to the lrhA promoter probe in vitro (Fig. 9B). In a recent study, OmpR-binding sites from E. coli and S. enterica were collected and aligned to generate the OmpR consensus (position-specific scoring matrix [PSSM]), in which a higher score denotes the higher probability of OmpR binding (51). Analysis of the lrhA promoter region revealed a putative OmpR binding site (Fig. S5) matching the OmpR consensus with a weight score of 9.05, which is higher than the cutoff value of 7 (51). Consistently, replacing the 20 nucleotides in the putative OmpR binding site of the lrhA promoter probe with low-score nucleotides abolished the formation of DNA-protein complexes in the EMSA (Fig. 9C). Further, mutations in the putative OmpR binding site significantly reduced the activity of the lrhA promoter in the WT strain, whereas the activities of the lrhA promoter with a mutant motif in the ΔompR mutant and the complemented strain were similar to that in the WT strain (Fig. 9A). These results suggest that OmpR directly activates the expression of lrhA by specifically recognizing an OmpR binding site within the lrhA promoter.

FIG 9.

OmpR positively regulates the expression of lrhA by directly binding to the lrhA promoter. (A) β-Galactosidase activities of the lrhA promoter (WT motif versus mutant motif) in the WT, ΔompR mutant, and complemented strains. Strains were grown in LB medium. ***, P ≤ 0.001; ns, not significant (Student’s t test). (B) OmpR (0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 μg) EMSA of the lrhA promoter region (+10 to −451) (50 ng). A 447-bp fragment from the opgH coding region instead of the lrhA promoter and 2 μg of OmpR protein were added to control A. The same amount of BSA was added to control B. (C) OmpR (0.5, 1, and 2 μg) EMSA of the lrhA promoter region (WT motif) versus the lrhA promoter region with mutations in the putative OmpR binding site (mutant motif).

DISCUSSION

Osmotic stress adaptation is critical for bacterial survival in dynamic environments, and in particular, for symbionts or pathogens to colonize and survive in host niches (52, 53). The paradigm of the two-component systems involved in bacterial response to osmotic stress is the EnvZ-OmpR system, of which EnvZ acts as a sensor responding to increasing extracellular osmolality and phosphorylates OmpR (47, 54). The phosphorylated OmpR acts as a DNA binding transcription factor to regulate the expression of its target genes involved in the osmotic stress responses (55). In addition, OmpR has been found to play a role in resistance to acid stress in E. coli and Y. pseudotuberculosis (54, 56). In this work, we show that the lrhA gene is a novel member of the OmpR stress response regulon and propose that the LrhA-mediated complex regulatory network coordinates the switch of a free-living to endophytic lifestyle in response to changes in environmental osmolarity in the plant growth-promoting bacterium Pantoea alhagi.

Flagella and motility have received great attention due to their roles in virulence and biofilm development (26, 57, 58). While bacterial chemotaxis and motility help cells approach favorable environments and escape hostile ones, the assembly and maintenance of the motility apparatus place high energy demands on the bacterial cells (59, 60). Therefore, bacteria have evolved a variety of strategies to control the multistep process of cell motility to avoid inappropriate energy expenditure (2, 10, 57). Previous studies have shown that LrhA and its homologues play a positive or negative role in bacterial motility mainly through controlling the expression of the flagellar master operon flhDC at the transcriptional level (33, 35, 40). Consistent with the role of LrhA in E. coli but opposite to that in Xenorhabdus nematophila (32, 33, 35), our results indicate that LrhA in P. alhagi represses flagellar motility by directly inhibiting the transcription of flhDC. In agreement, we also observed a significant derepression (log2 fold change, >1; P < 0.05) of genes that encode flagellin, flagellar motor proteins, and chemotaxis proteins in the ΔlrhA mutant (Table S1), supporting the role of LrhA in flagellar repression.

In many bacterial species, inhibition of cell motility and induction of surface adhesins and biofilm matrix components, particularly EPS and proteins, are inversely coordinated by the same regulatory factors that sense specific environmental cues (10, 26). EPS produced by a variety of bacteria have been shown to be important for the initiation of biofilm formation and for the first steps of the colonization process (21, 61, 62). In addition, EPS biosynthesis is required in later stages for the development of mature biofilms and help with effective colonization and persistence within the host (23, 63). Accordingly, our results show that LrhA coordinates motility control with EPS biosynthesis to ensure successful attachment and colonization of wheat roots. As LrhA plays a role in transcriptional regulation in response to osmotic stress, our finding provides a new insight into how changes in environmental osmolarity affect bacterial motility and EPS biosynthesis.

The OPGs occurring in almost all Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, and Gammaproteobacteria have received great attention due to their roles in regulation of a wide range of cellular processes, including virulence, motility, biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance, osmoadaptation, cell size control, host colonization, and even nodule development (42, 50). Among all the systems involved in osmoadaptation, OPGs are the only periplasmic components whose synthesis is modulated by osmotic stress across a wide range of proteobacteria, including pathogenic and symbiotic bacteria (42, 45, 50). In most bacterial species that have been studied, including E. coli, S. enterica, Dickeya dadantii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (44, 45, 50, 64), the concentrations of the OPGs decrease when the medium osmolarity increases, although the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. However, OPG synthesis was shown to be not osmoregulated in Brucella abortus (42). Moreover, the concentration of cell-associated OPGs in several strains of Rhizobium leguminosarum is independent of growth medium osmolarity, while these strains excrete large amounts of OPGs when grown in media of high osmolarity (50, 65). In contrast to previous studies, we show that the periplasmic concentration of the OPGs increases as the medium osmolarity increases in P. alhagi (Fig. 7B). It should be noted that an increase in the secretion of OPGs, but no change in the level of cell-associated OPGs during growth at elevated osmolarity, also suggests that the synthesis of OPGs increases when the osmolarity increases in R. leguminosarum. Therefore, our study introduces a novel mechanism of osmoregulation of OPG synthesis, supporting the view by Bontemps-Gallo et al. (50) that osmoregulation of OPG synthesis has different features among bacterial species.

In addition to osmolarity, these are only a few regulatory factors that were found to affect OPG biosynthesis in several bacterial species (50). For instance, OPG synthesis is upregulated by a diffusible signal factor in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (66), while the opgGH operon is activated by the sigma factor σE that responds to protein misfolding in the cell envelope of E. coli (67). Here, we show that LrhA directly regulates the expression of the opgGH operon at the transcriptional level, thus causing the accumulation of OPGs. Intriguingly, we found that the expression of lrhA responds to medium osmolarity in the same way as the opgGH operon, thus demonstrating that OPG biosynthesis is regulated by osmotic stress at least partially mediated by the LrhA regulator in P. alhagi. Hence, our study reveals a novel LrhA-dependent regulatory pathway linking environmental osmolarity to OPG biosynthesis.

While the biological roles of the OPGs have been extensively explored in recent years (42, 50, 68), the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. In the phytopathogenic enterobacterium D. dadantii, the OPGs are involved in the perception of the environment through the RcsCDB system (44). The RcsCDB phosphorelay system is a complex signaling pathway found in many members of enterobacteria (48, 49). In general, activation of the RcsCDB phosphorelay induces high levels of expression of the genes involved in the synthesis and transport of the EPS colanic acid, while it represses motility by decreasing expression of the flhDC operon (44, 48). A high concentration of OPGs was shown to repress the Rcs phosphorelay, whereas defects in OPG biosynthesis lead to increased phosphorylation of the RcsB regulator in D. dadantii (44, 46). Although the relationship between the periplasmic levels of OPGs and the Rcs phosphorelay remained undemonstrated in E. coli or S. enterica, phenotypes observed in mutants defective in OPG synthesis strongly suggest a similar control of the level of Rcs activation by OPGs in these bacterial species (64, 69). Surprisingly, the opgH mutant of P. alhagi showed enhanced swimming motility and increased expression of the flhDC operon, while EPS production and expression of the eps operon were decreased in this mutant, suggesting a decrease in RcsB phosphorylation in strains devoid of OPGs. The positive role of OPGs in control of the RcsCDB phosphorelay was further corroborated by the observations that the deletion of opgH or lrhA represses the phosphorylation level of the RcsB regulator in vivo. Therefore, our results reveal that OPGs in P. alhagi also control RcsCD-RcsB activation in a concentration-dependent manner but act in the opposite way compared with bacterial species such as D. dadantii, E. coli, and S. enterica.

Although the pleiotropic functions of LrhA and its homologues have been widely reported, the environmental signals and regulators which influence their expression remain largely unknown. A recent study in D. dadantii showed that feedback regulation of the succinylation of the OPGs is exerted by activation of the RcsCDB system, although the role of this feedback loop remained unclear (47). In E. coli, activation of the Rcs pathway was shown to repress lrhA expression (30). While we found that LrhA positively regulates OPG synthesis and thus activates the Rcs phosphorelay in P. alhagi, it is hypothesized that lrhA expression might be feedback regulated by the RcsCDB phosphorelay system. In agreement with this hypothesis, we observed that deletion of the rcsB gene led to significantly increased activity of the lrhA promoter, which was restored to the WT level by complementation with rcsB but not restored by complementation with rcsBD56N (Fig. S6A). These results indicate a negative-feedback regulation of lrhA expression by phosphorylated RcsB in P. alhagi. Consistent with the role of LrhA in transcriptional activation of the opgGH operon, we show that inactivation of the Rcs pathway also enhances the expression of opgGH (Fig. S6B), suggesting a closed feedback loop comprising LrhA, OPG synthesis, and the Rcs phosphorelay. In Y. pseudotuberculosis, the LrhA homologue RovM was shown to be indirectly controlled by the carbon storage regulator CsrA in response to nutritional status (34, 70). In this study, we show that OmpR directly regulates the expression of lrhA at the transcriptional level in response to osmotic stress, thus bridging a connection between the bacterial EnvZ-OmpR osmosensing system and the LrhA-mediated regulatory networks.

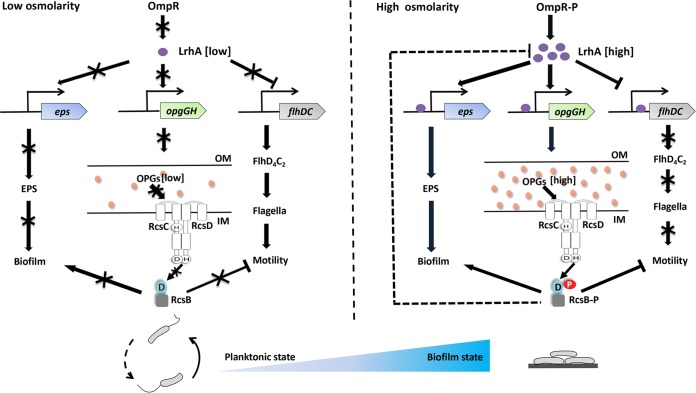

In summary, our study suggests that LrhA is an important transcription factor that regulates the motile-sessile switch in P. alhagi by directly repressing or inducing the expression of genes involved in flagellar biosynthesis, EPS production, and OPG synthesis in response to osmotic changes in the environment. At low osmolarity, there is a low concentration of OmpR-P, and the low level of LrhA is insufficient to repress expression of the flhDC operon or activate the expression of the eps and opgGH operons. The concentration of the OPGs is low, and the Rcs phosphorelay system is not activated. Thus, decreased EPS synthesis and an increase in motility support planktonic growth. Conversely, at high osmolarity, the concentration of OmpR-P increases, and enhanced expression of lrhA results in intensive repression of flhDC and high expression of eps and opgGH. Increased OPG synthesis achieves high-level activation of the RcsCDB phosphorelay. As a result, flagellum formation is turned off and EPS production is switched on, which results in the transition from planktonic growth to a biofilm lifestyle (Fig. 10). Hence, our data suggest a novel strategy utilized by P. alhagi to sense environmental osmotic changes and coordinate swimming motility and biofilm formation at multiple levels, thus mediating the transition between a free-living planktonic lifestyle and a surface-associated lifestyle. Osmotic stress-responsive transcription factors like LrhA may be of great significance for pathogenic and symbiotic bacteria to appropriately modulate cellular behaviors and establish antagonistic or beneficial interactions with their host in response to changing osmotic conditions. Our findings should prove helpful to an understanding of how bacteria sense and integrate environmental cues into an appropriate response to allow for quick and energy-efficient adaptation to environmental changes.

FIG 10.

Model for the osmoregulatory mechanism operating through OmpR and LrhA that links osmotic changes to host colonization in the plant drought resistance-promoting bacterium P. alhagi. At low osmolarity (left), the OmpR-P levels decrease, and the level of LrhA remains low. The result is that the expression of the eps and opgGH operons is not activated, and flhDC would be derepressed. At high osmolarity (right), the concentration of OmpR-P increases, and it activates the expression of LrhA. Sequentially, LrhA activates transcription of eps and opgGH and inhibits transcription of flhDC, which results in enhanced EPS production and biofilm formation and reduction in motility. The blue gradient at the bottom represents the switch between planktonic and biofilm lifestyles in response to osmotic stress. OM, outer membrane; IM, inner membrane.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. The sequences of all primers used are listed in Table 2. P. alhagi LTYR-11Z and its derivatives were grown in LB medium, M9 medium (34), or LOS medium (45) at 30°C. The osmolarity of LOS medium was increased by supplementation of NaCl (150 and 450 mM) or sorbitol (300 and 600 mM). E. coli strains were grown in LB medium at 37°C. When required, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 50 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 25 μg ml−1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| BL21(DE3) | Host for expression vector pET28a | Novagen |

| S17-1 λpir | λpir lysogen of S17-1, thi pro hsdR hsdM+ recA RP4 2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 | 34 |

| TG1 | Host for cloning | Stratagene |

| P. alhagi | ||

| WT | Wild-type strain P. alhagi LTYR-11Z, Ampr | 41 |

| WT(pKT100) | Wild-type strain harboring plasmid pKT100 | 10 |

| WT(pBBR1MCS-1) | Wild-type strain harboring plasmid pBBR1MCS-1 | 10 |

| WT(pKT100-GFPmut3*) | Wild-type strain harboring expression construct pKT100-GFPmut3* | 41 |

| WT(pKT100-mCherry) | Wild-type strain harboring expression construct pKT100-mCherry | This study |

| WT(pKT100-opgGH) | Wild-type strain harboring expression construct pKT100-opgGH | This study |

| WT(pBBR1MCS1-opgGH) | Wild-type strain harboring expression construct pBBR1MCS1-opgGH | This study |

| ΔlrhA mutant | lrhA deleted in LTYR-11Z | This study |

| ΔlrhA(pKT100) mutant | ΔlrhA mutant harboring plasmid pKT100 | This study |

| ΔlrhA(pBBR1MCS-1) mutant | ΔlrhA mutant harboring plasmid pBBR1MCS-1 | This study |

| ΔlrhA(pKT100-lrhA) mutant | ΔlrhA mutant harboring expression construct pKT100-cra | This study |

| ΔlrhA(pBBR1MCS1-lrhA) mutant | ΔlrhA mutant harboring expression construct pBBR1MCS1-lrhA | This study |

| ΔlrhA(pKT100-opgGH) mutant | ΔlrhA mutant harboring expression construct pKT100-opgGH | |

| ΔlrhA(pBBR1MCS1-opgGH) mutant | ΔlrhA mutant harboring expression construct pBBR1MCS1-opgGH | |

| ΔlrhA(pKT100-GFPmut3*) mutant | ΔlrhA mutant harboring expression construct pKT100-GFPmut3* | This study |

| ΔlrhA(pKT100-mCherry) mutant | ΔlrhA mutant harboring expression construct pKT100-mCherry | This study |

| ΔtuaG mutant | tuaG deleted in LTYR-11Z | This study |

| ΔtuaG(pKT100) mutant | ΔtuaG mutant harboring plasmid pKT100 | This study |

| ΔtuaG(pKT100-tuaG) mutant | ΔtuaG mutant harboring expression construct pKT100- tuaG | This study |

| ΔflhDC mutant | flhDC deleted in LTYR-11Z | This study |

| ΔflhDC(pKT100) mutant | ΔflhDC mutant harboring plasmid pKT100 | This study |

| ΔflhDC(pKT100-flhDC) mutant | ΔflhDC mutant harboring expression construct pKT100-flhDC | This study |

| ΔopgH mutant | opgH deleted in LTYR-11Z | This study |

| ΔopgH(pKT100) mutant | ΔopgH mutant harboring plasmid pKT100 | This study |

| ΔopgH(pKT100-opgH) mutant | ΔopgH mutant harboring expression construct pKT100-opgH | This study |

| ΔrcsB mutant | rcsB deleted in LTYR-11Z | This study |

| ΔrcsB(pKT100) mutant | ΔrcsB mutant harboring plasmid pKT100 | This study |

| ΔrcsB(pKT100-rcsB) mutant | ΔrcsB mutant harboring expression construct pKT100-rcsB | This study |

| ΔrcsB(pKT100-rcsBD56N) mutant | ΔrcsB mutant harboring expression construct pKT100-rcsBD56N | This study |

| ΔrcsB(pBBR1MCS-1) mutant | ΔrcsB mutant harboring plasmid pBBR1MCS-1 | This study |

| ΔrcsB(pBBR1MCS1-rcsB) mutant | ΔrcsB mutant harboring expression construct pBBR1MCS1-rcsB | This study |

| ΔrcsB(pBBR1MCS1-rcsBD56N) mutant | ΔrcsB mutant harboring expression construct pBBR1MCS1-rcsBD56N | This study |

| ΔompR mutant | ompR deleted in LTYR-11Z | This study |

| ΔompR(pBBR1MCS-1) mutant | ΔlrhA mutant harboring plasmid pBBR1MCS-1 | This study |

| ΔompR(pBBR1MCS1-ompR) mutant | ΔompR mutant harboring expression construct pBBR1MCS1-ompR | This study |

| ΔlrhA ΔopgH mutant | lrhA and opgH deleted in LTYR-11Z | This study |

| ΔlrhA ΔopgH(pKT100-lrhA) mutant | ΔlrhA ΔopgH mutant harboring expression construct pKT100-lrhA | This study |

| ΔlrhA ΔopgH(pKT100-opgH) mutant | ΔlrhA ΔopgH mutant harboring expression construct pKT100-opgH | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKT100 | Cloning vector, p15A replicon, Kmr | 34 |

| pKT100-lrhA | lrhA in pKT100 | This study |

| pKT100-mCherry | mCherry in pKT100 | This study |

| pKT100-GFPmut3* | GFPmut3* in pKT100 | 41 |

| pKT100-tuaG | tuaG in pKT100 | This study |

| pKT100-flhDC | flhDC in pKT100 | This study |

| pKT100-opgH | opgH in pKT100 | This study |

| pKT100-opgGH | opgGH in pKT100 | This study |

| pKT100-rcsB | rcsB in pKT100 | This study |

| pKT100-rcsBD56N | rcsBD56N in pKT100 | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-1 | Broad-host-range vector, lacZa rep mob, Cmr | 81 |

| pBBR1MCS1-lrhA | lrhA in pBBR1MCS-1 | This study |

| pBBR1MCS1-opgGH | opgGH in pBBR1MCS-1 | This study |

| pBBR1MCS1-rcsB | rcsB in pBBR1MCS-1 | This study |

| pBBR1MCS1-rcsBD56N | rcsBD56N in pBBR1MCS-1 | This study |

| pBBR1MCS1-ompR | ompR in pBBR1MCS-1 | This study |

| pCas | CRISPR-Cas9 system plasmid used for in-frame deletion, Kmr | 71 |

| pTargetF1 | pTargetF with spectinomycin resistance gene replaced by a chloramphenicol resistance gene, Cmr | 10 |

| pTargetF-ΔlrhA | Construct used for in-frame deletion of lrhA | This study |

| pTargetF-ΔtuaG | Construct used for in-frame deletion of tuaG | This study |

| pTargetF-ΔflhDC | Construct used for in-frame deletion of flhDC | This study |

| pTargetF-ΔopgH | Construct used for in-frame deletion of opgH | This study |

| pTargetF-ΔrcsB | Construct used for in-frame deletion of rcsB | This study |

| pK18mobsacB-PlrhA::lacZ | For lrhA promoter fusion to P. alhagi, Kmr | This study |

| pK18mobsacB-PlrhA (mutant motif)::lacZ | For lrhA promoter with mutant motif fusion to P. alhagi, Kmr | This study |

| pK18mobsacB-Peps::lacZ | For eps promoter fusion to P. alhagi, Kmr | This study |

| pK18mobsacB-PflhDC::lacZ | For flhDC promoter fusion to P. alhagi, Kmr | This study |

| pK18mobsacB-PopgGH::lacZ | For opgGH promoter fusion to P. alhagi, Kmr | This study |

| pET28a | Expression vector with N-terminal hexahistidine affinity tag, Kmr | Novagen |

| pET28a-lrhA | lrhA in pET28a | This study |

| pET28a-rcsB | rcsB in pET28a | This study |

| pET28a-ompR | ompR in pET28a | This study |

Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance. Resistance to chloramphenicol, kanamycin, and ampicillin was at 20, 50, and 100 μg ml−1, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′)a | Purposeb |

|---|---|---|

| lrhA-sg20-F-SpeI | GTCCTAGGTATAATACTAGTAAATGCTCAACCAGGGCGAAGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC | Generate sgRNA with an N20 sequence for targeting the lrhA locus |

| tuaG-sg20-F-SpeI | GTCCTAGGTATAATACTAGTAGTCGGTACCTCCGGTAAACGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC | Generate sgRNA with an N20 sequence for targeting the tuaG locus |

| flhDC-sg20-F-SpeI | GTCCTAGGTATAATACTAGTCGTGGCAGTCCGCCGCCAAAGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC | Generate sgRNA with an N20 sequence for targeting the flhDC locus |

| opgH-sg20-F-SpeI | GTCCTAGGTATAATACTAGTTATTATCCAGTCTTCACCAAGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC | Generate sgRNA with an N20 sequence for targeting the opgH locus |

| rcsB-sg20-F-SpeI | GTCCTAGGTATAATACTAGTGAAATATACCCCGGAAAGCGGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC | Generate sgRNA with an N20 sequence for targeting the rcsB locus |

| ompR-sg20-F-SpeI | AGCTAGCTCAGTCCTAGGTATAATACTAGTGTTCAACCCGCGTGAGCTGCGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC | Generate sgRNA with an N20 sequence for targeting the ompR locus |

| sg20-R | CTCAAAAAAAGCACCGACTCGG | Generate sgRNA |

| lrhA-up-F | CCGAGTCGGTGCTTTTTTTGAGTTTGCGTTGCGCAGTTTTG | Generate pTargetF-ΔlrhA |

| lrhA-up-R | AGGTGTTGAGATCTGCTACTGCAAC | Generate pTargetF-ΔlrhA |

| lrhA-down-F | GTTGCAGTAGCAGATCTCAACACCTGCCGCAATCCGGACAGTG | Generate pTargetF-ΔlrhA |

| lrhA-down-R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACCTTTGCGGGGTTATTTTTTTGAT | Generate pTargetF-ΔlrhA |

| lrhA-CF-HindIII | CCCAAGCTTATGACTAATGCAAATCGTCCGATA | Generate pBBR1MCS1-lrhA |

| lrhA-CR-BamHI | CGCGGATCCTTATTCTTCATCATCCAGCAACATT | Generate pBBR1MCS1-lrhA |

| lrhA-CR-F-BamHI | CGCGGATCCATGACTAATGCAAATCGTCCGATA | Generate pKT100-lrhA |

| lrhA-CR-R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACTTATTCTTCATCATCCAGCAACATT | Generate pKT100-lrhA |

| lrhA-PF-BamHI | CGCGGATCCATGACTAATGCAAATCGTCCGATA | Generate pET28a-lrhA |

| lrhA-PR-EcoRI | CCGGAATTCTTATTCTTCATCATCCAGCAACATT | Generate pET28a-lrhA |

| tuaG-up-F | CCGAGTCGGTGCTTTTTTTGAGGCTCAAATAAGCCCGTCAAGA | Generate pTargetF-ΔtuaG |

| tuaG-up-R | GACACCAGTAACGGAGCCAAC | Generate pTargetF-ΔtuaG |

| tuaG-down-F | GTTGGCTCCGTTACTGGTGTCCAACACCGCTTACCCGCT | Generate pTargetF-ΔtuaG |

| tuaG-down-R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACCGGGATTTCACGACCTGC | Generate pTargetF-ΔtuaG |

| tuaG-CR-F-BamHI | CGCGGATCCATGATGAAAACGAAACTAAAGTTGG | Generate pKT100-tuaG |

| tuaG-CR-R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACTCACCAGTTTTTGATATCTCTCGC | Generate pKT100-tuaG |

| flhDC-up-F | CCGAGTCGGTGCTTTTTTTGAGTCACAAGCGTTACTGATGGATT | Generate pTargetF-ΔflhDC |

| flhDC-up-R | AGCAAGCAGCAAATATGACAAG | Generate pTargetF-ΔflhDC |

| flhDC-down-F | CTTGTCATATTTGCTGCTTGCTAAGACGTAAACTTTCGGTAGAGG | Generate pTargetF-ΔflhDC |

| flhDC-down-R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACGCGGAACAGCATCGGTAA | Generate pTargetF-ΔflhDC |

| flhDC-CF-BamHI | CGCGGATCCATGGGTACATCCGAATTATTAAAAC | Generate pKT100-flhDC |

| flhDC-CR-SalI | ACGCGTCGACTTAAACGGCGTGTTTAACCTG | Generate pKT100-flhDC |

| opgH-up-F | CCGAGTCGGTGCTTTTTTTGAGGGTTACGCCTCAGGTTAGCA | Generate pTargetF-ΔopgH |

| opgH-up-R | GAACTGTTTGCCCTCATCCA | Generate pTargetF-ΔopgH |

| opgH-down-F | TGGATGAGGGCAAACAGTTCCTGTCGCCGTTTGTGTCG | Generate pTargetF-ΔopgH |

| opgH-down-R | ACGCGTCGACGGCTTATTTCGCAGGCGT | Generate pTargetF-ΔopgH |

| opgH-CF-BamHI | CGCGGATCCATGAATAAATCAATCCTAACTCCC | Generate pKT100-opgH |

| opgH-CR-SalI | ACGCGTCGACTTATTTCGCAGGCGTTAGC | Generate pKT100-opgH |

| opgGH-CF-BamHI | CGCGGATCCGTGCTGATTACTAACAAAAATAAATCG | Generate pKT100-opgGH |

| opgGH-CR-SalI | ACGCGTCGACTTATTTCGCAGGCGTTAGC | Generate pKT100-opgGH |

| opgGH-CF-HindIII | CCCAAGCTTGTGCTGATTACTAACAAAAATAAATCG | Generate pBBR1MCS1-opgGH |

| opgGH-CR-BamHI | CGCGGATCCTTATTTCGCAGGCGTTAGC | Generate pBBR1MCS1-opgGH |

| rcsB-up-F | CCGAGTCGGTGCTTTTTTTGAGCTTATCAGCGGGGGGTACTAC | Generate pTargetF-ΔrcsB |

| rcsB-up-R | GGCTGTTAATCAATGCTGTCG | Generate pTargetF-ΔrcsB |

| rcsB-down-F | CGACAGCATTGATTAACAGCCGCCCCGATGGACAAAGAGT | Generate pTargetF-ΔrcsB |

| rcsB-down-R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACGGCACCGCATAGCGAATAC | Generate pTargetF-ΔrcsB |

| rcsB-CF-SalI | ACGCGTCGACATGAATAATTTGAACGTAATTATTGCC | Generate pBBR1MCS1-rcsB |

| rcsB-CR-BamHI | CGCGGATCCTTACTCTTTGTCCATCGGGGC | Generate pBBR1MCS1-rcsB |

| rcsB-CR-F-BamHI | CGCGGATCCATGAATAATTTGAACGTAATTATTGCC | Generate pKT100-rcsB |

| rcsB-CR-R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACTTACTCTTTGTCCATCGGGGC | Generate pKT100-rcsB |

| rcsB-PF-BamHI | CGCGGATCCATGAATAATTTGAACGTAATTATTGCC | Generate pET28a-rcsB |

| rcsB-PR-EcoRI | CCGGAATTCTTACTCTTTGTCCATCGGGGC | Generate pET28a-rcsB |

| rcsBD56N-up-F | GTTACAGCTAATTGAGAAACAGCTATCT | Generate mutated rcsBD56N fragment |

| rcsBD56N-up-R | GAGAGATTGGTGATCAGGACGTT | Generate mutated rcsBD56N fragment |

| rcsBD56N-down-F | AACGTCCTGATCACCAATCTCTCCATGCCTGGCGAAAAATATG | Generate mutated rcsBD56N fragment |

| rcsBD56N-down-R | TTACTCTTTGTCCATCGGGGC | Generate mutated rcsBD56N fragment |

| ompR-up-F | CCGAGTCGGTGCTTTTTTTGAGAAAGCAGCATCACAATCAAAC | Generate pTargetF-ΔompR |

| ompR-up-R | TTCGGTCAGATAACGCTCC | Generate pTargetF-ΔompR |

| ompR-down-F | GGAGCGTTATCTGACCGAACCTGGGCTACGTGTTTGTT | Generate pTargetF-ΔompR |

| ompR-down-R-SalI | GGTAATAGATCTAAGCTTCTGCAGGTCGACAAAACTGGTAATGCTGTGCC | Generate pTargetF-ΔompR |

| ompR-CF-SalI | ACGCGTCGACATGCAAGAAAACTACAAAATTCTGGTC | Generate pBBR1MCS1-ompR |

| ompR-CR-BamHI | CGCGGATCCTCATGCTTTAGTGCCGTCCG | Generate pBBR1MCS1-ompR |

| ompR-PF-BamHI | ACTGGTGGACAGCAAATGGGTCGCGGATCCATGCAAGAAAACTACAAAATTCTGGTC | Generate pET28a-ompR |

| ompR-PR-EcoRI | GTGCTCGAGTGCGGCCGCAAGCTTGTCGACTCATGCTTTAGTGCCGTCCG | Generate pET28a-ompR |

| PlrhA-F-BamHI | CGCGGATCCAAAAGTAGATTGATACGGAGTGAAA | pK18mobsacB-PlrhA::lacZ |

| PlrhA-R-XbaI | CTAGTCTAGATTGCATTAGTCATATTTTTCTTCAC | pK18mobsacB-PlrhA::lacZ |

| Peps-F-BamHI | CGCGGATCCAAAAGTAGATTGATACGGAGTGAAA | pK18mobsacB-Peps::lacZ |

| Peps-R-XbaI | CTAGTCTAGATTGCATTAGTCATATTTTTCTTCAC | pK18mobsacB-Peps::lacZ |

| PflhDC-F-BamHI | CGCGGATCCAACCTTTCAACGTCTTGCCTG | pK18mobsacB-PflhDC::lacZ |

| PflhDC-R-XbaI | CTAGTCTAGACTGCGACAAAGTATCAGCCAT | pK18mobsacB-PflhDC::lacZ |

| PopgGH-F-BamHI | CGCGGATCCTGAAAAGGAATGCCAAGAAGC | pK18mobsacB-PopgGH::lacZ |

| PopgGH-R-XbaI | CTAGTCTAGACTGACCCAGTGCGTTTTTTTC | pK18mobsacB-PopgGH::lacZ |

| lrhA-EMSA-F | TATCCATCAACGGGCTTT | EMSA |

| lrhA-EMSA-R | CATTAGTCATATTTTTCTTCACTTATA | EMSA |

| lrhA-EMSA-CK-F | ATATGAAGACCATTCTGCCTTACC | Generate fragment of negative control for EMSA |

| lrhA-EMSA-CK-R | GAACCAGCTCCATCCAGGC | Generate fragment of negative control for EMSA |

| lrhA-M-up-F | TACTACTTAAAGTGCCGATAACCTGAAAGGG | Generate mutated fragment of PlrhA for EMSA |

| lrhA-M-up-R | TTCCATGCGACGCTCAGCGGGCTGCTTTTCATAATACCGC | Generate mutated fragment of PlrhA for EMSA |

| lrhA-M-down-F | CCGCTGAGCGTCGCATGGAAGCTGTCGCTTCCGGTTTATCGGAG | Generate mutated fragment of PlrhA for EMSA |

| lrhA-M-down-R | CAATCGCCAGTTTCGGGTAGACAGAG | Generate mutated fragment of PlrhA for EMSA |

| eps-EMSA-F | ATTTAACAGCATTGGTAGCTGAA | EMSA |

| eps-EMSA-R | TGAATTATCATCACTATTGCTGA | EMSA |

| flhDC-EMSA-F | GATGTTAATTTTGCGTAACAGCACAT | EMSA |

| flhDC-EMSA-R | TTGCTGGCTGGTAAATCTAAAGATG | EMSA |

| flhDC-EMSA-CK-F | ATATGAAGACCATTCTGCCTTACC | Generate fragment of negative control for EMSA |

| flhDC-EMSA-CK-R | GAACCAGCTCCATCCAGGC | Generate fragment of negative control for EMSA |

| opgGH-EMSA-F | TGGTGGCTGGAATAAATAAGTGA | EMSA |

| opgGH-EMSA-R | ATCCCCCCCTTTCGTGTG | EMSA |

| opgGH-EMSA-CK-F | TGTAACGCCTGGAAGTTTCTG | Generate fragment of negative control for EMSA |

| opgGH-EMSA-CK-R | CGGCGTGTTTAACCTGTTC | Generate fragment of negative control for EMSA |

| 16S-RT-F | CGAGCGCAACCCTTATCC | qRT-PCR |

| 16S-RT-R | CGGACTACGACGCACTTTATG | qRT-PCR |

| lrhA-RT-F | ACGCAATCAGCCGTCAGTC | qRT-PCR |

| lrhA-RT-R | AGCAAGAACGGCAGAATGG | qRT-PCR |

| opgG-RT-F | TTTGGCAATGTTCAGCACGA | qRT-PCR |

| opgG-RT-R | GCTGTTTATCCTGCGGCTTT | qRT-PCR |

| opgH-RT-F | TGGATGCGGATAGCGTAATG | qRT-PCR |

| opgH-RT-R | GTTATGCCCCCAATAGTGCG | qRT-PCR |

Underlined sites indicate restriction enzyme cutting sites added for cloning. Letters in bold denote the annealing regions for overlap PCR.

sgRNA, single guide RNA.

Gene deletion and complementation in P. alhagi.

Markerless chromosomal gene deletion in P. alhagi was performed using the CRISPR-Cas9 system, as described previously (10, 71). The mutant colonies were selected on LB plates containing 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin and 25 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol. After curing of the pTarget series and pCas plasmids as previously described (71), the deletion mutants were in trans complemented with pKT100 or pBBR1MCS-1 carrying their respective genes.

Biofilm formation and swimming motility assays.

Biofilm formation was measured using crystal violet staining, as described previously (10, 72). Swimming motility assays were carried out in 0.3% agar tryptone plates, as described previously (73). In addition, LOS medium and LOS medium with added NaCl (150 and 450 mM) or sorbitol (300 and 600 mM) were used as the base media to evaluate the effects of osmotic stress on biofilm formation and swimming motility, as described previously (45).

RNA sequencing and data analysis.

The P. alhagi WT strain and the ΔlrhA mutant were cultured in agitated LB medium (200 rpm) at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0, and then bacterial cells were harvested for RNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing analysis. Briefly, cultures were subjected to total RNA extraction and mRNA enrichment using the Ribo-Zero kit. Transcriptome sequencing was performed using the BGISEQ-500 platform (74). Quality-filtered reads were aligned to the P. alhagi LTYR-11Z genome (GenBank accession no. CP019706) using HISAT (75). We used the fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) measure for quantification of gene expression. For each strain, three independent cell cultures were used and served as biological replicates. Student’s t test was used to identify significantly (P < 0.05) up- or downregulated genes between the WT strain and the ΔlrhA mutant. To validate the RNA-seq data, 13 genes were randomly selected to be analyzed by qRT-PCR.

Construction of lacZ fusion strains and β-galactosidase assays.

To generate chromosome-located transcriptional fusions, the lacZ fusion reporter vectors were separately transformed into E. coli S17-1 λpir and mated with P. alhagi strains, as described previously (54). The lacZ fusion reporter strains were grown to stationary phase in LB broth or LOS medium supplemented with NaCl (150 and 450 mM) or sorbitol (300 and 600 mM) at 30°C, and β-galactosidase assays were performed with o-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside as the substrate (76). Assays were repeated three times independently, and in each of these three biological replicates, three technical replicates were made.

Overexpression and purification of recombinant protein.

To express and purify soluble His6-tagged recombinant proteins His6-LrhA, His6-RcsB, and His6-OmpR, the pET28a derivatives carrying their respective genes were transformed into the E. coli BL21(DE3) host strain. The resulting strains were grown at 37°C in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.5, and then expression was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 8 h at 26°C. After bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation, the pellets were resuspended, broken by sonication, and purified with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) His-bind resin (Novagen, Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified recombinant proteins were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C. Protein purity was examined by SDS-PAGE, and the concentrations of the purified proteins were measured using the Bradford assay (77). The resulting proteins were stored at −80°C until use.

EMSAs.

EMSAs were performed as described by Zhang et al. (10). Briefly, DNA fragments for EMSAs were amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of P. alhagi and then purified and quantified. For DNA-binding assays, DNA substrates were incubated at room temperature for 30 min with different concentrations of proteins in a total volume of 20 μl of EMSA buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 4 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol). The binding reaction mixtures were then subjected to 6% native PAGE gels containing 5% glycerol in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer, and electrophoresis was performed at 150 V and 4°C. Gels were stained with SYBR green, and images were acquired using the Universal Hood II system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

CR assay and EPS quantification.

EPS production was first examined by CR staining, as described previously (78). Briefly, 2 μl of each overnight culture was spotted onto salt-free CR plates (10 g liter−1 tryptone, 5 g liter−1 yeast extract, 0.5 mM IPTG, 40 μg ml−1 CR, 20 μg ml−1 Coomassie blue) and incubated at 30°C for 3 days to assess the colony morphology. EPS quantification was performed as described previously (10).

OPG analysis.

OPGs of P. alhagi strains were extracted and quantified as described previously (44). Briefly, P. alhagi strains were grown in LB broth or LOS medium supplemented with 450 mM NaCl or 600 mM sorbitol at 30°C until mid-exponential phase. Bacterial cells were collected, resuspended in distilled water, and extracted with 5% trichloroacetic acid. Then, the extracts were neutralized with 10% ammonium hydroxide and concentrated by rotary evaporation. The resulting material was fractionated by gel filtration on a Bio-Gel P-4 (Bio-Rad) column eluted with 0.5% acetic acid at a flow rate of 15 ml h−1. Fractions of 1.5 ml were separately collected, and the presence of sugar in each fraction was determined using the anthrone-sulfuric acid colorimetric method (79). Fractions containing OPGs were pooled, and quantification was performed by the same anthrone reagent procedure.

qRT-PCR analysis.

RNAs were extracted separately from exponentially growing cultures using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and treated with DNase I kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed as described previously (34) using TransStart Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) in a 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). A serial 10-fold dilution (1 to 10,000) of cDNA obtained by reverse transcription was used to generate a standard curve for determining the gene-specific PCR efficiency of the primer pairs in qRT-PCR by using linear regression model. The amplification efficiency for each specific primer pair was calculated based on the slope of the standard curve, as described previously (80). 16S rRNA was used as an internal control for normalization of the results. All assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. The PCR efficiency determined by the standard curve ranged from 98.7 to 102.7%.

Phos-tag SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

P. alhagi strains were inoculated into LB medium and incubated with continuous shaking until the OD600 reached 1.0 at 30°C. Half a milliliter of each culture was centrifuged, and the cell pellet was immediately lysed with 12.7 μl of 1 M formic acid. Then, samples were solubilized by 5 μl of 4× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and neutralized by 2.8 μl of 5 N NaOH. The prepared samples were loaded onto 12% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels containing 125 μM Phos-tag acrylamide (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and 250 μM MnCl2, which were prepared as described previously (46). After electrophoresis, the separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore), and then Western blot assays were performed with rabbit anti-RcsB polyclonal antibodies (at a 1:1,000 dilution) to assess the RcsB phosphorylation levels in vivo according to the method described previously (54). Phosphorylated RcsB and unphosphorylated RcsB were quantified by densitometric analysis of protein bands using a Quantity One image analyzer system (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA). Then, the ratio of phosphorylated RcsB and unphosphorylated RcsB to total RcsB in each sample was calculated as described previously (46).

Plant assays.

Wheat root surface attachment and endophytic colonization assays were performed as previously described (10). Competition assays were performed using a 1:1 mixture of the WT LTYR-11Z and the ΔlrhA mutant carrying plasmids pBBR1MCS-1 and pKT100, respectively, and antibiotic resistance was used to distinguish the two strains. Additionally, the WT strain carrying pKT100 and the ΔlrhA mutant carrying pBBR1MCS-1 were used for competition assays. Further, a 1:1 mixture of the GFP-labeled WT and the mCherry-labeled ΔlrhA mutant in 1/2 MS medium was used for inoculation of wheat seedlings, and roots were examined for the presence of bacterial cells by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) after incubation at 30°C and 50 rpm for 15 h. A mixed-bacterium suspension incubated for the same time in 1/2 MS medium without transplanted wheat seedlings was used as a control to ensure that the ratio of tagged bacterial cells remained at the levels at which they were inoculated. Alternatively, a 1:1 mixture of the mCherry-labeled WT and the GFP-labeled ΔlrhA mutant was used for CLSM analysis. To investigate whether osmotic stress plays a role in wheat root attachment by P. alhagi, 2-day-old wheat seedlings were inoculated with bacterial suspensions of 108 cells ml−1 in LOS medium and LOS medium supplemented with 450 mM NaCl or 600 mM sorbitol. After 1 and 15 h of incubation at 30°C and 50 rpm, the number of attached cells of each strain was determined by CFU counts, as described previously (10). The assays were repeated three times, and statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test.

Data availability.

The RNA-seq data from this study have been submitted to the Sequence Read Archive database under accession no. SRP186086.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31770121 and 31671292) and the Fundamental Research Fund for the Central Universities (grant 2452018154).

We declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00077-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Verstraeten N, Braeken K, Debkumari B, Fauvart M, Fransaer J, Vermant J, Michiels J. 2008. Living on a surface: swarming and biofilm formation. Trends Microbiol 16:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koirala S, Mears P, Sim M, Golding I, Chemla YR, Aldridge PD, Rao CV. 2014. A nutrient-tunable bistable switch controls motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. mBio 5:e01611-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01611-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]