Abstract

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is one of the therapies with curative intent used to treat esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), and overall survival of patients with esophageal carcinoma treated with CRT has improved. As the number of long-term survivors treated with concurrent CRT has increased, more patients experience late toxicities. A delayed adverse event, such as pleural effusion, is sometimes fatal, but little is known about its treatment. A 72-year-old man diagnosed with ESCC was treated with definitive CRT. He had a complete response to CRT, and 4 years later he complained of dyspnea, caused by pleural effusion. Diuretic agents and drainage of pleural effusion were not sufficiently effective in this case. After oral administration of 30 mg prednisolone, re-accumulation of fluid in the pleural space was controlled and the prednisolone dose was gradually tapered. Corticosteroids could be effective treatment for delayed pleural effusion after radiotherapy, and should be considered an option for treatment-refractory pleural effusion.

Keywords: Esophageal cancer, Concurrent chemoradiotherapy, Late toxicity, Pleural effusion, Corticosteroids

Introduction

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) improves local control and overall survival of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. While more patients who have complete response (CR) survive for long term, they also have higher rates of delayed complications, particularly of the lungs or heart [1]. A delayed adverse event, such as pleural effusion after CRT for esophageal cancer, is difficult to treat and is associated with mortality [2]; however, appropriate drug therapies for treatment are not yet fully known. Here, we report a case of delayed pleural effusion as an adverse event related to CRT for esophageal cancer, successfully treated with corticosteroids.

Case report

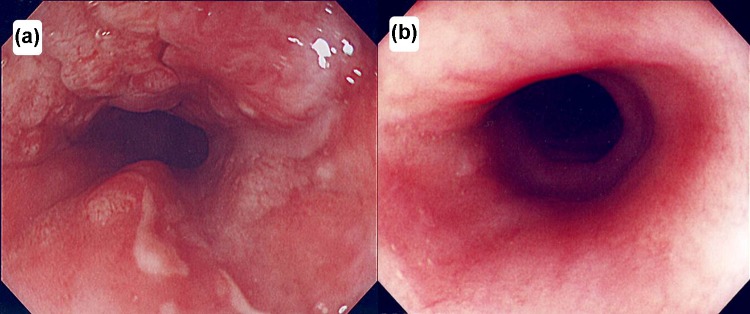

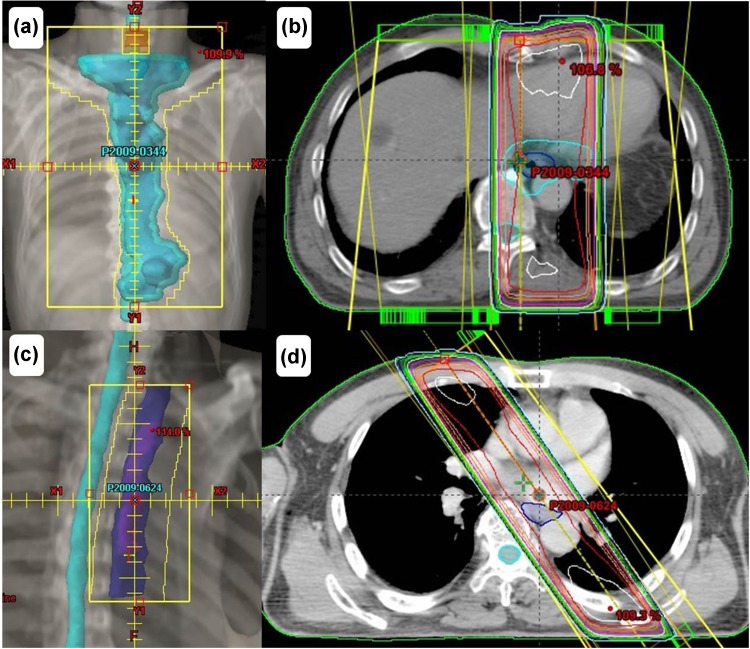

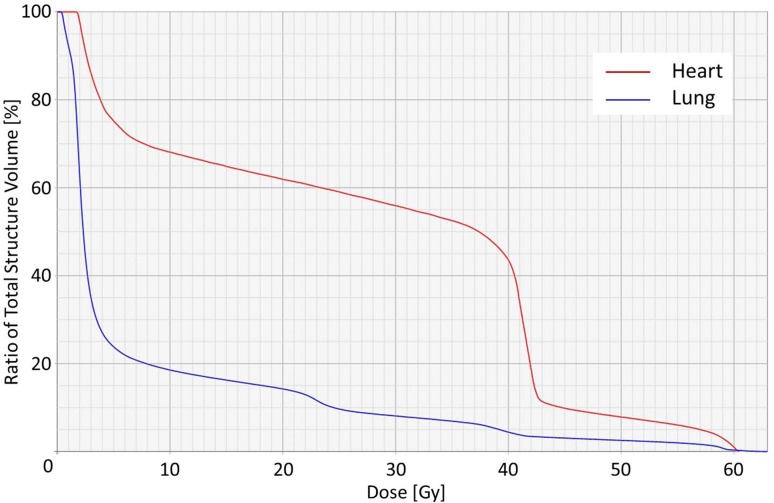

A 72-year-old man visited our hospital owing to an esophageal tumor. Blood tests performed prior to treatment revealed no liver or kidney dysfunction. His cardiac function was within the normal range. Upper endoscopic examination (Fig. 1a) revealed a type 4 tumor, diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma by endoscopic biopsy. He was diagnosed with clinical T2N0M0 Stage IB [Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), 7th edition] esophageal cancer. Results from his blood and biochemical examinations are shown in Table 1. He was treated with concurrent CRT. Chemotherapy comprised two courses of slow infusion of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), 400 mg/m2/day on days 1–5 and 8–12, and 2-h infusion of cisplatin, 40 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 [3]. Before the second cycle of chemotherapy, Grade 2 leucopenia (CTCAE; common toxicity criteria for adverse events version 4.03 [4]) was observed, and the second cycle of chemotherapy was delayed by 2 weeks before being administered at the usual dosage. Concurrent radiotherapy of 60 Gy (30 fractions of 2 Gy, 5 days/week) was delivered over 9 weeks including a 3-week break. The initial target volume included the gross tumor volume and supraclavicular, mediastinal, and celiac axis lymph node regions until 40 Gy had been administered, and then only the gross tumor volume was irradiated, with care taken to avoid the spinal cord. The initial field of this case is shown in Fig. 2a, b. An additional 20 Gy boost dose was delivered, and the boost field is shown in Fig. 2c, d [5]. The dose volume histograms for this case are shown in Fig. 3, and the mean doses to the lungs and heart were 7.7 and 27.6 Gy, respectively. Thirty-eight days after the entire course of CRT, esophagoscopy was performed but it did not reveal the tumor and the inside of the esophagus was smooth (Fig. 1b). No malignant findings were observed on biopsy from the esophagus where the carcinoma had been located; thus, we considered this a complete response (CR).

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic findings of this patient treated with chemoradiotherapy. a Before chemoradiotherapy. b After chemoradiotherapy. The primary lesion showed complete remission without stenosis

Table 1.

Laboratory findings on the first examination (a) and on the admission for pleural and pericardial effusion (b)

| (a) | (b) | |

|---|---|---|

| Peripheral blood | ||

| WBC (/μl) | 5700 | 6500 |

| RBC (104/μl) | 490 | 462 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 14.1 | 14.4 |

| Hct (%) | 42.1 | 41.6 |

| Plt (103/μl) | 204 | 237 |

| Biochemistry | ||

| TP (g/dl) | 6.7 | 6.6 |

| Alb (g/dl) | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| T-Cho (mg/dl) | 219 | 138 |

| AST (U/l) | 22 | 132 |

| ALT (U/l) | 11 | 102 |

| LDH (U/l) | 169 | 271 |

| ALP (U/l) | 306 | 613 |

| γ-GTP (U/l) | 18 | 66 |

| T-bil (mg/dl) | 0.8 | 1 |

| BNP (pg/ml) | – | 73 |

| Na (mEq/l) | 139 | 124 |

| K (mEq/l) | 4.5 | 4.8 |

| Cl (mEq/l) | 104 | 88 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 11 | 29 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 0.1 | 4.9 |

| HbA1c (JDS) (%) | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Blood sugar (mg/dl) | 95 | – |

| TSH (μIU/ml) | – | 13.6 |

| FT3 (pg/ml) | – | 2.8 |

| FT4 (pg/ml) | – | 1.1 |

| Tumor marker | ||

| CEA (ng/ml) | 3.6 | 2.3 |

| SCC (ng/ml) | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Anti-p53 (U/ml) | 0.51 | <0.40 |

Fig. 2.

The initial field of this case is shown in (a) and (b), and the boost field of this case is shown in (c) and (d)

Fig. 3.

The dose volume histogram of the heart and lung

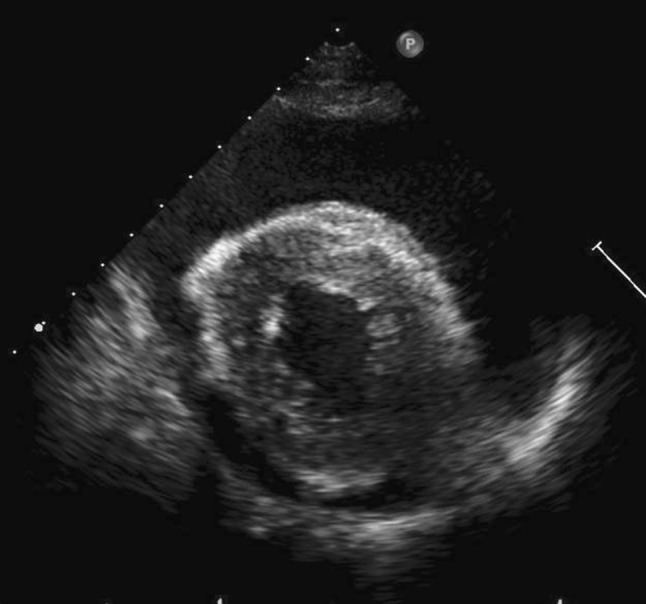

Four years after CRT, the patient was re-admitted to our hospital with complaints of dyspnea and heart palpitations on exertion. Chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) revealed a large amount of pleural effusion on the left side (Figs. 4a, 5a), without metastasis or pneumonitis (Fig. 5b). Transthoracic echocardiography showed a large pericardial effusion with slight decrease in the left ventricular ejection fraction (Fig. 6). Thoracentesis on the left side and pericardiocentesis were performed, and the volume of effusion removed was 1300 and 400 ml, respectively. Drained fluid was clear and serous; cytological examination was negative for bacteria and cancer cells. Blood examination showed that tumor marker levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and squamous cell carcinoma-related antigen (SCC) were not elevated. Slight hypoalbuminemia was noted; liver transaminase was elevated slightly. Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels were within the normal ranges; protein was not detected in the urine. Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level was elevated slightly in the context of normal thyroid hormone level. These laboratory data are shown in Table 1. For subclinical hypothyroidism, 50 μg/day of levothyroxine was administrated orally. Autoimmune disease and infections, including tuberculosis, were ruled out. Cardiac function, after draining pericardial effusion, was normal when re-assessed by echocardiography. The pleural and pericardial effusions were suspected to be late toxicities caused by CRT. Initially, loop diuretic agent (20 mg/day) and an aldosterone antagonist (25 mg/day) were administrated orally. Pericardial effusion was controlled well; however, pleural effusion was not and required additional drainage twice for 2 months. We prescribed 30 mg/day of oral prednisolone (equivalent to 0.57 mg/kg/day), with diuretic agents administered concurrently. Prednisolone was continued and tapered for 4 additional months, without refractory pleural effusion. After 5.0 mg/day of prednisolone was administered, the patient complained of dyspnea; chest radiography revealed pleural effusion. We increased the prednisolone dose to 7.5 mg/day, and more gradually tapered it. Although the diuretic agents are still administered, prednisolone was no longer administered for 3 and half years after the first pleural effusion. A small amount of pleural effusion remains in the left thoracic cavity (Fig. 3b), but the patient is free from respiratory symptoms.

Fig. 4.

Chest radiography shows a large amount of pleural effusion on the left side (a); chest radiography shows a small amount of pleural effusion in the left thoracic cavity after tapering of corticosteroids (b)

Fig. 5.

Chest-enhanced computed tomography shows pleural effusion and pericardial effusion (a); pneumonitis is not clear in the lung field (b)

Fig. 6.

Transthoracic echocardiography in the short axis view shows a large amount of pericardial effusion

Discussion

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy achieves prolonged survival in many different types of cancer including esophageal carcinoma. Traditionally, concurrent CRT was indicated for mainly unresectable esophageal cancer; however, concurrent CRT is a therapeutic option with curative intent for resectable esophageal cancer [3]. As patients who received concurrent CRT survive longer, the occurrence of late toxicity should be considered. Late toxicities after thoracic radiotherapy have been reported in patients with lung, breast, and esophageal cancers, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma [6–9]. In esophageal cancer, late toxicity after CRT including serious, life-threatening complications has been reported [1, 2]. It is difficult to exclude the heart and lungs from the field of irradiation when treating the thoracic esophagus. Kato et al. reported that radiation pneumonitis was the most common late toxicity (55.3%) followed by pleural effusion (47.4%). Clinically significant late toxicities, such as severe (≥Grade 3 CTCAE) pericardial effusion, pleural effusion, and radiation pneumonitis, were observed in 16, 9 and 4% of the patients treated with CRT, respectively [3].

Recent studies have reported pleural effusion as a late toxicity of irradiation [1, 3, 10, 11]. However, there are few reports of successful therapy for severe or refractory pleural effusion. The specific treatment of pleural effusion depends on the etiology; thus, it is necessary to rule out cardiac insufficiency, infection, malignancy, autoimmune disease, nephrotic syndrome and hypoalbuminemia [12]. Hypoalbuminemia generally causes systemic edema, including pleural effusion, ascites accumulation, and hands and feet edema. In this case, slight hypoalbuminemia was noted; however, the effusion was localized within the chest cavity. Thus, pericardial and pleural effusions were considered late toxicities caused by radiotherapy to the esophagus. A mean dose of 7 Gy to the lungs is associated with symptomatic pneumonitis, with a probability of 5% [13]. In this case, the pleural effusion was more severe than the pericardial effusion. The tolerance of normal tissue to irradiation is markedly different between the lungs and the heart. The normal heart tissue is more resistant to irradiation than the normal lungs [13]. In the same dose of irradiation, normal heart tissue has less inflammation, which causes pericarditis, than that of normal lung tissue, which causes symptomatic pneumonitis [13]. For cases of pleural effusion due to radiation therapy, it is difficult to remove the cause of inflammation; therefore, drainage using chest tubes or diuretic therapy was selected as symptomatic therapies [12]. Shigematsu et al. reported death related to uncontrollable pleural and pericardial effusion in a patient treated with CRT for esophageal cancer [2]. His autopsy demonstrated infiltration of inflammatory cells to the pleural surface. Mehta reported that serum cytokines and chemokines are elevated after radiotherapy [14]. Corticosteroids are effective for preventing inflammatory reaction [15]. In the current case, after corticosteroid administration was initiated, the frequency of drainage required for pleural effusion decreased, suggesting that pleuritis could be sensitive to corticosteroids. In addition, when we reduced the corticosteroid dose, the complaints of dyspnea and pleural effusion increased. The amount of pleural effusion changed according to the corticosteroid dose, also suggesting that corticosteroids were effective for pleuritis treatment.

The adequate dose of corticosteroids is unclear for pleuritis causing pleural effusion. Corticosteroid therapy (0.5 mg/kg/day prednisolone or equivalent steroids) is recommended for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; American Thoracic Society recommended early administration of corticosteroid for high response rates [14, 15]. Corticosteroids were also effective for radiation-related pericardial effusion [17]. Pericarditis was characterized pathologically by the infiltration of inflammatory cells including monocytic cells [2, 16]. Corticosteroids prevent these inflammatory cells from infiltrating tissue, and 30 mg/day prednisolone has a beneficial effect on radiation-induced pericarditis; 0.2–0.5 mg/kg/day prednisolone is more effective compared with higher doses in reducing recurrences and has fewer side effects [18–20]. A few studies have examined the effect of corticosteroids on pleural effusion. Osawa et al. reported that 40 mg prednisolone daily improved pleural and pericardial effusions [17]. Shigematsu et al. reported radiation-induced pleural effusion treated with diuretic agents and 16 mg dexamethasone for 6 days [2]. The effect of 16 mg dexamethasone is more than twice as strong as that of 30 mg of prednisolone; however, it was insufficient to control the pleural effusion [2]. In the current case, both diuretic agents and corticosteroids were used; pleural effusion was controlled successfully. The difference between the two types of corticosteroids (prednisolone and dexamethasone) is not clear; however, gradual tapering of prednisolone for a few years might be effective for controlling pleural effusion. Steroid use for a protracted period should be avoided, owing to possible adverse events of corticosteroids such as moon face and diabetes mellitus. Dose reduction for a short period may cause re-accumulation of pleural effusion; therefore, dose tapering needs to be as gradual as possible. For patients with difficult to control pleural effusion, corticosteroids could be effective and a therapeutic option.

Informed consent

Written informed consents were obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

References

- 1.Kumekawa Y, Kaneko K, Ito H, et al. Late toxicity in complete response cases after definitive chemoradiotherapy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:425–432. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1771-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shigematsu N, Kitamura N, Saikawa Y, et al. Death related to pleural and pericardial effusions following chemoradiotherapy in a patient with advanced cancers of the esophagus and stomach. Keio J Med. 2007;56(4):124–129. doi: 10.2302/kjm.56.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato K, Muro K, Minashi K, et al. Phase II study of chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin for stage II–III esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: JCOG trial (JCOG 9906) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(3):684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) ver. 4.03 http://www.jcog.jp/dctor/tool/ctcaev4.html. Accessed Nov 2016

- 5.Ariga H, Nemoto K, Miyazaki S, et al. Prospective comparison of surgery alone and chemoradiotherapy with selective surgery in resectable squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(2):348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López RM, Cerezo PL. Toxicity associated to radiotherapy treatment in lung cancer patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9:506–512. doi: 10.1007/s12094-007-0094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto N, Noda Y, Miyashita Y. A case of refractory bilateral pleural effusion due to post-irradiation constrictive pericarditis. Respirology. 2002;7:365–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2002.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman DL, Constine LS. Late effects of treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:249–257. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2006.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carver JR, Shapiro CL, Ng A, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical evidence review on the ongoing care of adult cancer survivors: cardiac and pulmonary late effects. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3991–4008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morota M, Gomi K, Kozuka T, et al. Late toxicity after definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy for thoracic esophageal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(1):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirai K, Tamaki Y, Kitamoto Y, et al. Dose-volume histogram parameters and clinical factors associated with pleural effusion after chemoradiotherapy in esophageal cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(4):1002–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vinaya SK, Jyotsna MJ. Pleural effusion: diagnosis, treatment, and management. Emerg Med. 2012;4:31–52. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S29942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marks LB, Yorke ED, Jackson A, et al. The use of normal tissue complication probability (NTCP) models in the clinic. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:S10–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta V. Radiation pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis in non-small-cell lung cancer: pulmonary function, prediction, and prevention. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:5–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Thoracic Society Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:646–664. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.ats3-00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.William CR, David v, Joseph S, et al. Myocardial hydroxyproline reduced by early administration of methylprednisolone of ibuprofen to rabbits with radiation-induced heart disease. Circulation. 1982;65(5):924–927. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.65.5.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osawa S, Yamada T, Saitoh T, et al. Treatment with corticosteroid for pericardial effusion in a patient with advanced synchronous esophageal and gastric cancers following chemoradiotherapy. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;4:229–237. doi: 10.1159/000318751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brian S. Corticosteroids in radiation-induced pericarditis. Chest. 1978;74(1):96–98. doi: 10.1378/chest.74.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keelan MH, Rudders RA. Successful treatment of radiation pericarditis with corticosteroids. Arch Intern Med. 1974;134:145–147. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1974.00320190147025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, et al. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericarditis: high versus low doses: a nonrandomized observation. Circulation. 2008;118:667–671. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.761064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]