Abstract

Primary adenocarcinoma of the vulva is a rare disease, and usually arises in a Bartholin gland or occurs in association with Paget’s disease. Furthermore, adenocarcinoma of intestinal type of the vulva is an extremely rare neoplasm, and few cases have been reported. The appropriate treatment for optimal prognosis is unclear. We report a case of adenocarcinoma of intestinal type of the vulva occurring in a 63-year-old female. The tumor was found near the urethra, and biopsy specimen showed a proliferation of signet ring cells embedded in an abundant myxoid stroma and irregular tubular structures of atypical columnar epithelium. An extensive workup showed no metastases. Local excision with a 2-cm lesion in the vulva side, bilateral superficial inguinal lymph node dissection and Cloquet lymph node biopsy were performed. Cancer cells contained mucinous materials in the cytoplasm, which exhibited diffuse positive staining for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2. The final pathologic diagnosis was adenocarcinoma of intestinal type of the vulva (pT1bN0M0). The patient received adjuvant external irradiation because of positive urethral surgical margin. She is well 1 year after therapy. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 20 and polyclonal CDX2 is helpful with investigation of adenocarcinoma of intestinal type, but long-term prognosis remains unclear.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, Intestinal type, Immunohistochemistry, Vulva

Introduction

Primary adenocarcinoma of the vulva is rare, and most arise from Bartholin’s gland or occur in association with Paget’s disease [1, 2]. Adenocarcinoma of intestinal type is an extremely rare variant and few cases have been reported to date [3]. In this paper, we report a case of adenocarcinoma of intestinal type of the vulva occurring in a 63-year-old Japanese female.

Case report

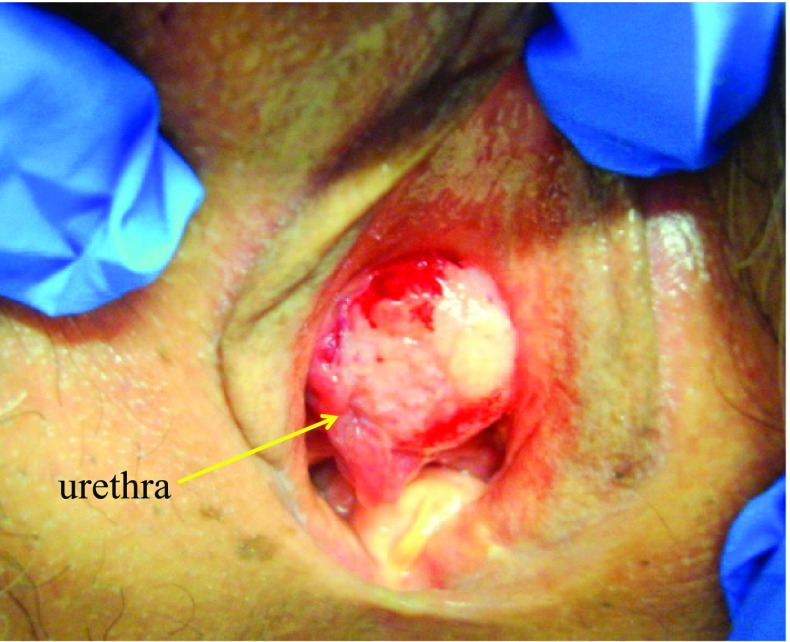

The patient, a 63-year-old Japanese woman, gravid 3, parity 2, was referred to our hospital because of postmenopausal bleeding. A papillary mass with easy contact bleeding, 18 mm in diameter was seen near the urethra (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis revealed the 18 mm-sized enhanced mass, and uterus and both ovaries were normal shape and size. Scrape cytology and biopsy specimen showed atypical glandular cells in mucinous background. An extensive workup, including systemic positron emission computed-tomography (PET-CT), gastrointestinal tract fiberscope, cystoscope and mammography revealed no metastases. Serum CEA and CA125 levels were in the reference range. Local excision with a 2.0-cm tumor-free margin including subcutaneous tissue only on the vulva side, bilateral superficial inguinal lymph node dissection and Cloquet lymph node biopsy were performed. The surgical specimen showed a 2.0-cm lesion in the vulva side, which revealed microscopic stromal invasion, reaching 1 mm in depth. The final pathologic diagnosis was adenocarcinoma of intestinal type of the vulva stage IB (pT1bN0M0). The patient received adjuvant external irradiation with 64 Gy because of positive surgical margin on the urethral side and remains well and free of disease 1 year after treatment.

Fig. 1.

Gross examination. External genitals. A papillary mass with easy contact bleeding mass was seen near the urethra

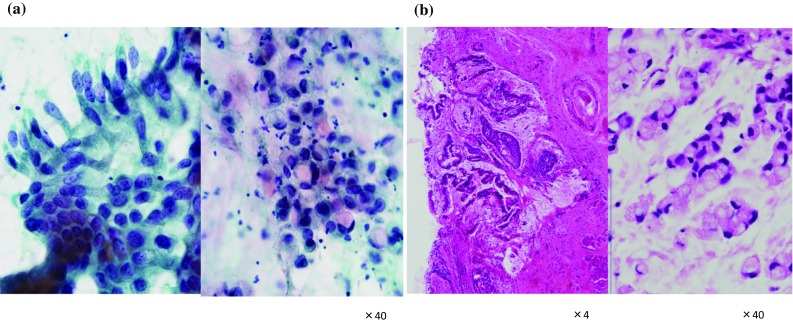

Cytological findings

Scrape cytology specimens of the vulvar tumor revealed atypical epithelial cells in a mucinous background (Fig. 2a). Tumor cells formed palisading and loose clusters, and a cytoplasm with enriched mucinous material. The nuclei of the tumor cells were elongated and irregular, with a thin nuclear membrane. Tumor cells had fine granular chromatin and small nucleoli, suggesting adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 2.

Scrape cytology and pathology. a Atypical epithelial cells form loose clusters in a mucinous background. Tumor cells formed palisading and loose clusters, and a cytoplasm with enriched mucinous material. The nuclei of the tumor cells were elongated and irregular, with a thin nuclear membrane. b The minimal stromal invasion to a depth of 1 mm was noted. The pathological examination showed irregular tubular structures of atypical columnar epithelium with hyperchromatic nuclei, and a proliferation of signet ring cells embedded in an abundant myxoid stroma

Pathological findings

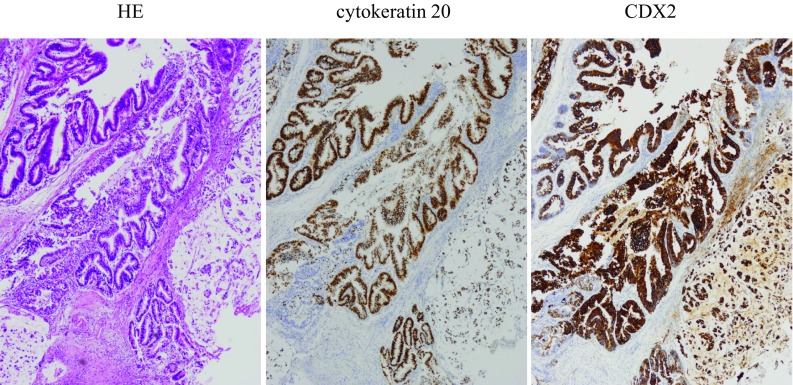

Gross examination revealed a solitary mass arising in the surface epithelium of the vulva near the urethra. The cut section of the tumor showed a superficial polypoid mass measuring 2.0 × 1.8 cm. The pathological examination showed irregular tubular structures of atypical columnar epithelium with hyperchromatic nuclei, and a proliferation of signet ring cells embedded in an abundant myxoid stroma (Fig. 2b). The minimal stromal invasion to a depth of 1 mm was noted. No definite lymphatic invasion was seen. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells showed diffuse positive staining for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 (Fig. 3), whereas CK7 and GCDFP-15 (gross cystic disease fluid protein-15) were negative. These histochemical findings confirmed that the tumor was an intestinal type of neoplasm. The final pathologic diagnosis was adenocarcinoma of intestinal type of the vulva.

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical examination. The tumor cells showed diffuse positive staining for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2

Discussion

Primary adenocarcinoma of the vulva is rare, and commonly originates from Bartholin’s gland. Other possible origins are sweat glands and skene glands [1, 2]. Adenocarcinoma of intestinal type is diagnosed to distinguish it from tumors arising from Bartholin and other specialized anogenital glands by WHO pathological classification 2014 [4]. This tumor is extremely rare, and its origin remains controversial. There are some reports about origins of vulvar intestinal-type adenocarcinoma. This tumor has been suggested to originate from the cloacal remnants [5–12]. It could be misplaced or aberrant tissue or might be a normal feature of that area. There are some cases originating from sweat glands or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the vulva, but true adenocarcinoma of intestinal type is an extremely rare variant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical features and outcome of adenocarcinoma of intestinal type of the vulva

| Author (year) | Age | Location | Lymph node metastasis | operation | Adjuvant therapy | Follow-up (mo) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiltman and Knutzen (1978) [5] | 50 | Periurethral | Positive | MRV&LND | None | 12 | NED |

| Kennedy and Majmudar (1993) [6] | 54 | Left posterior | Negative | RV&LND | None | 120 | NED |

| Kennedy and Majmudar (1993) [6] | 63 | Posterior fourchette | Negative | WLE | None | 48 | NED |

| Ghamande et al. (1995) [9] | 67 | Vulva | Negative | RV&LND | None | Unknown | Unknown |

| Willen et al. (1999) [14] | 57 | Posterior part of vestibulum | Negative | WLE | None | 26 | NED |

| Zaidi and Conner (2001) [7] | 43 | Posterior fourchette | Negative | MRV&LND | None | 18 | NED |

| Rodriguez et al. (2001) [10] | 69 | Right labium majus | Negative | WLE | None | 36 | NED |

| Dube et al. (2004) [8] | 58 | Right labium majus | Negative | WLE | None | 4.5 | NED |

| Cormio et al. (2012) [11] | 59 | Vulva | Positive | RV&LND | Chemotherapy | 54 | DOD |

| Cormio et al. (2012) [11] | 42 | Vulva | Negative | RV&LND | None | 39 | NED |

| Sui et al. (2016) [3] | 43 | Hymen | Negative | WLE | Chemotherapy (PTX + CBDCA) |

24 | NED |

| Tepeoglu et al. (2016) [19] | 40 | Left labium minus close to urethra | Positive | WLE&LND | None | 38 | NED |

| Lee et al. (2017) (12) | 64 | Right posterior part of the major labium | Negative | WLE | None | 12 | NED |

| Present case | 63 | Periurethra | Negative | WLE&LND | Radiotherapy | 12 | NED |

RV radical vulvectomy, MRV modified radical vulvectomy, WLE wide local excision, LND lymph node dissection, NED no evidence of disease, DOD died of disease, PTX paclitaxel, CBDCA carboplatin

In our case, metastatic tumor was excluded by extensive workup, including systemic PET-CT, gastrointestinal tract fiberscope, cystoscope and mammography. Primary adenocarcinoma of the urinary bladder is another uncommon tumor, which has similar histopathological features. In the present case, the tumor was located near the urethra with slight invasion of the urethra.

Immunohistochemical study showed strong positive staining for cytokeratin 20 and polyclonal CDX2, supporting the diagnosis. The value of immunohistochemical staining was reported in previous cases [13, 14]. Intestinal-type mucinous carcinoma showed positive reaction for cytokeratin 20 and polyclonal CDX2, which is usually diffuse positive reaction in mullerian ducts of the female genital tract. We confirmed that CK7 and GCDFP-15 (gross cystic disease fluid protein-15) which indicate positive by sweat gland and ectopic mammary gland were negative. These histochemical findings confirmed that the final pathologic diagnosis was adenocarcinoma of intestinal type of the vulva.

The clinical management of this rare tumor is unknown. Our patient had an 18-mm nodule near the urethra in the midline vulva. Local excision with a 2.0-cm tumor-free margin including subcutaneous tissue only on the vulva side, bilateral superficial inguinal lymph node dissection and Cloquet lymph node biopsy were performed following Japanese gynecological cancer association guidelines because she had no severe medical complications [15]. Radical vulvectomy was also considered as the standard therapy. Recently, modified surgical management has been undertaken to avoid surgical complications [16, 17]. Radical local excision of the invasive lesion is the most appropriate for lesions on the lateral or posterior aspects of the vulva, where preservation of the clitoris is feasible. After surgery, radiation therapy seems to be clearly indicated in patients with involved surgical margins (< 5 mm) [18]. The patient received adjuvant external irradiation because of positive surgical margin on the urethral side, but it is unclear whether adjuvant radiotherapy for adenocarcinoma of intestinal type of the vulva is effective. It is commonly recognized that adenocarcinoma is not highly susceptible to radiation therapy, but there is no additional effective chemotherapy for vulvar adenocarcinoma.

In conclusion, we have described adenocarcinoma of intestinal type of the vulva. Knowledge of this tumor is very limited due to the small number of cases. Almost patients including our case were observed without a recurrence in the short period prognosis only by surgical excision. We think surgical procedure is an appropriate treatment of this tumor.

Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 20 and polyclonal CDX2 is helpful for investigating adenocarcinoma of intestinal type, but long-term prognosis is still unclear. A successful treatment modality needs to be verified through several more cases.

Acknowledgements

We thank James P. Mahaffey, PhD, from Edanz Group (http://www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

There is no editorial or financial conflict of interest among authors.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Consent for publication

The case report approval was obtained from the Hospital Research Ethics Board.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wilkinson EJ. Premalignant tumors of the vulva. In: Kurman RJ, editor. Blaustein’s pathology of the female genital tract. 6. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 55–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novak ER, Woodruff JD. Gynecologic and obstetrics pathology with clinical and endocrine relations. 7. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sui Y, Zou J, Batchu N, et al. Primary mucious adenocarcinoma of the vulva: a case report and review of the literature. Mol clin oncol. 2016;4:545–548. doi: 10.3892/mco.2016.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Classification of Tumors of Female Reproductive Organs. 4th edition. IARC 2014 Press, Lyon

- 5.Tiltman AJ, Knutzen VK. Primary adenocarcinoma of the vulva originating in misplaced cloacal tissue. Obstet Gynecol. 1978;51:30 s3 s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy JC, Majmudar B. Primary adenocarcinoma of the vulva, possibly cloacogenic: a report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 1993;38:113–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaidi SN, Conner MG. Primary vulvar adenocarcinoma of cloacogenic origin. South Med J. 2001;94:744–746. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200107000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dube V, Veilleux C, Plante M, et al. Primary villoglandular adenocarcinoma of cloacogenic origin of the vulva. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:377–379. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghamande SA, Kasznica J, Griffiths CT, Finkler NJ, Hamid AM. Mucinous adenocarcinomas of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57:117–120. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez A, Isaac MA, Hidalgo E, Marquez B, Nogales FF. Villoglandular adenocarcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;83:409–411. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cormio G, Carriero C, Loizzi V, Gissi F, Leone L, Putignano G, et al. “Intestinal-type” mucinous adenocarcinoma of the vulva: a report of two cases. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2012;33:433–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee IH, Kim MK, Lee YK, Hon SR, Lee KH. Primary mucinous adenocarcinoma of the vulva, intestinal type. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017;60(4):369–373. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.4.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez A, Isaac MA, Hidalgo E, et al. Villoglandular adenocarcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;83:409–411. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willen R, Bekassay Z, Carlen B, et al. Cloacogenic adenocarcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;74:298–301. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saito T, Tabata T, Ikushima H, et al. Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology guidelines 2015 for the treatment of vulvar cancer and vaginal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23(2):201–234. doi: 10.1007/s10147-017-1193-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arvas M, Kose F, Gezer A, et al. Radical versus conservative surgery for vulvar carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2005;88:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan JK, Sugiyama V, Pham H, et al. Margin distance and other clinico-pathologic prognosis factors in vulvar carcinoma: a multivariate analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:636–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faul CM, Mirmow D, Huang Q, et al. Adjuvant radiation for vulvar carcinoma: improved local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:381–389. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(97)82500-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tepeoglu M, Uner H, Haberal AN, et al. Cloacogenic adenocarcinoma of the vulva: a case report and review of the literature. Turkish J Pathol. 2016;34(3):255–258. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2015.01359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]