Abstract

A case of cystitis occurring after administration of nivolumab, an anti-programmed death-1 antibody, which was considered to be an immune-related adverse event, is reported. A 62-year-old man with pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma (T4N0M1a Stage IV) was being treated with nivolumab as fourth-line chemotherapy. He was hospitalized for a fever and diarrhea after 3 courses. Fasting and antibiotic medication reduced the fever and alleviated the diarrhea. He then developed cystitis with no evidence of infection. Cystoscopy showed diffused redness and erosion of the bladder mucosa; urine cytology was negative. Imaging examinations showed no abnormalities. Urinary tract pain and hematuria due to nivolumab were diagnosed by exclusion following a bladder biopsy. Since symptomatic treatment was unsuccessful, steroid pulse therapy was given, which resolved the patient’s signs and symptoms. The patient was then switched to maintenance prednisolone and tapered gradually. The 4th course of nivolumab was then resumed with concomitant administration of steroid, and it was possible to continue administration of nivolumab without progression of cystitis.

Keywords: Anti-PD-1 antibody, Cystitis, Immune-related adverse events, Immune checkpoint inhibitor, Nivolumab

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are increasingly being used as drug therapy for tumors. Immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which are different from the adverse events related to conventional chemotherapy, have been reported [1]. Although various symptoms can occur throughout the body, irAEs affecting the urinary tract have yet to be reported. A case of cystitis occurring after administration of nivolumab (NIVO), an anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibody, which was considered to be an irAE, is reported.

Case report

A 62-year-old man was diagnosed with pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma (T4N0M1a Stage IV), and he was being administered NIVO as fourth-line chemotherapy. The patient had a history of valvular heart disease surgery, but no history of allergies. A fever of 38.5 °C and diarrhea (CTCAE Grade 2) developed on the 15th day after 3 courses of NIVO, and the patient was hospitalized for treatment. Fasting and antibiotic medication reduced the fever, and the diarrhea was also alleviated. On the 22nd day after administration, pain on urination, frequent urination, and macroscopic hematuria occurred, so the patient was referred to our department. Urinalysis showed red blood cells (RBCs) ≥100/HPF and white blood cells (WBCs) of 5–9/HPF; urine culture was negative. Blood tests showed WBCs 5,800/μl (neutrophils 72.8%; eosinophils 2.1%), CRP 5.2 mg/dl, and LDH 307 U/l. Tests for viral infections were negative for urinary adenovirus DNA and cytomegalovirus pp65 antigen. Cystoscopy showed diffuse redness and erosion of the bladder mucosa. Urine cytology was negative. Abdominal ultrasonography and abdominal CT showed no abnormal findings in the kidneys or urinary tract. There was also no inflammation extending from the digestive tract to the bladder.

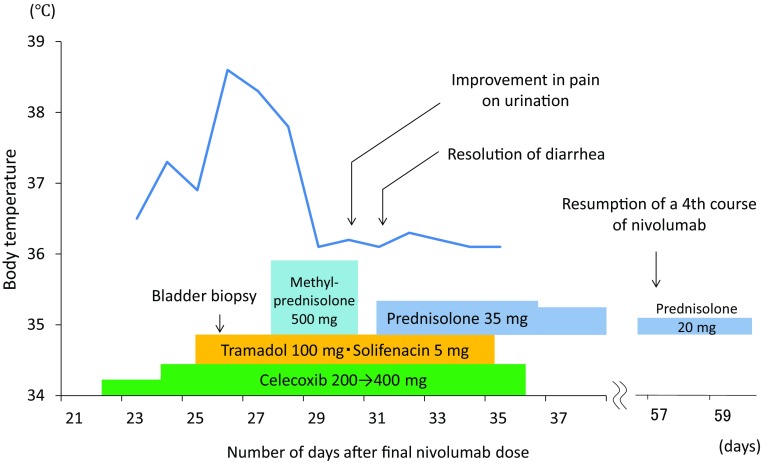

Figure 1 shows the course of treatment. Although analgesic and anticholinergic drugs were administered, the symptoms did not improve, and pain control was difficult (face rating scale (FRS) 4/5). Bladder biopsy was performed on the 26th day after administration, but a fever started to develop from the evening of the same day. On histopathological examination, the mucosal epithelium had completely sloughed off, and interstitial edematous changes were observed. Only slight lymphocytic infiltration was observed (Fig. 2). Urinary tract pain (Grade 3) and hematuria (Grade 3) due to NIVO administration were diagnosed by exclusion. Since symptomatic treatment also became difficult, steroid pulse therapy (methylprednisolone (mPSL) 500 mg × 3 days) was performed from the 28th day, the fever resolved quickly, and the pain on urination and diarrhea symptoms were alleviated. The steroid was switched to the maintenance dose of prednisolone (PSL) 0.5 mg/kg and decreased gradually, and there was no recurrence of the symptoms thereafter. Administration of a 4th course of NIVO was resumed on the 57th day. Administration of NIVO was continued, with concomitant administration of PSL, until discontinuation in the 8th course due to disease progression.

Fig. 1.

Clinical course

Fig. 2.

a Cystoscopic at bladder biopsy showed diffuse mucosal redness and bleeding. b Histopathological findings. Epithelial desquamation and edematous changes in interstitium were observed. There was no evidence of malignancy

Discussion

Anti-PD-1 antibody drugs, which are immune checkpoint inhibitors, are used to treat malignant melanoma [2], non-small-cell lung cancer [3], and renal cell carcinoma [4]. Their applications are expected to expand in the future. IrAEs due to immune checkpoint inhibitors include various symptoms throughout the body. However, this is the first report of symptoms related to the urinary tract. Most of the symptoms of irAEs are minor, but in a few cases, they are grade 3–4, serious life-threatening adverse events [1].

In the present case, it appears that self-antigenicity had been latently expressed in the bladder mucosa from the beginning, but the inflammatory response then became manifest as a result of immune activation and caused the symptoms. The cystitis may have appeared as part of the systemic immune reaction; transurethral biopsy or coagulation of bladder might have activated systemic immune reaction, rather than a localized bladder reaction, and then induced the fever. However, the detailed pathogenesis of irAEs has not yet been elucidated [1]. It is necessary to keep in mind the possibility of irAEs for any symptoms that develop during the treatment period. The time of onset can be any time from immediately after the start of dosing to after completion of dosing, but the majority of irAEs manifest within 4 months [3]. It is said that the frequency and severity of irAEs do not increase with aging, changes in liver and renal functions, performance status (PS), or the dosage of immune checkpoint inhibitors [1, 5, 6].

Consultation with a specialized department when an irAE is suspected is desirable and exclusion of infection, symptoms associated with disease progression, and incidental symptoms must be performed before treatment. The direction of treatment also differs depending on the cause. With regard to treatment of irAEs of CTCAE Grade 2 or higher, postponement/withdrawal of dosing and symptomatic treatment is necessary. Steroid administration is recommended for grade 2 irAEs that persist for more than 1 week and irAEs of Grade 3 or above. For resumption of NIVO administration, adverse events need to be stable at Grade 1 or lower on prednisone at ≤10 mg/day. Dose-limiting toxicities are not seen, and resumption of NIVO administration at the same dosage is recommended [5, 6]. The therapeutic response to steroid differs depending on the type of irAE [2, 3]. Gastrointestinal, liver, and renal disorders respond quickly to treatment, whereas dermatological symptoms and endocrine disorders require a period of time, and long-term hormone supplementation is often unavoidable [1]. Although, in the present case, local invasion due to bladder biopsy may have caused an excessive immune reaction and led to the fever after surgery, the response to steroid therapy was considered good. There was no recurrence of symptoms, and the steroid dosage was gradually decreased. When a steroid is administered, there is concern that its immunosuppressive action will attenuate the antitumor effect. No difference was found between the objective response rate or the time to response in melanoma as a function of whether an immunosuppressive drug was co-administered with NIVO [2, 7]. For patients with severe irAEs, there should be no hesitation in using steroids early.

The antitumor effects of anti-PD-1 antibodies have not been found to show a clear correlation with either the dosage or the administration period [1]. A few cases of a “durable tumor response” have been seen even after administration is discontinued [2–4]. That is, it is important to establish a treatment plan that prioritizes management of irAEs, rather than aiming for early resumption of administration.

Although irAEs are less frequent than adverse events seen with conventional chemotherapy, they can include various symptoms. It will be necessary to study a larger number of cases to establish the profile and management of irAEs, which can be expected to lead to a better prognosis.

A case of cystitis that required steroid administration after treatment with an anti-PD-1 antibody, NIVO, was reported. When administering an immune checkpoint inhibitor, appropriate management in collaboration with specialized departments is needed.

Abbreviations

- PD-1

Programmed death-1

- irAEs

Immune-related adverse events

- NIVO

Nivolumab

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event v4.0

- CT

Computed tomography

- FRS

Face rating scale

- PS

Peformance status

References

- 1.Champiat S, Lambotte O, Barreau E, et al. Management of immune checkpoint blockade dysimmune toxicities: a collaborative position paper. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(4):559–574. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(19):1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber JS, Antonia SJ, Topalian SL, et al. Safety profile of nivolumab (NIVO) in patients (pts) with advanced melanoma (MEL): a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl):abstr 9018. [Google Scholar]