Abstract

Ehrlichiosis are severe, feverish tick‐borne illnesses caused by specific species within the genus Ehrlichia (Anaplasmataceae family). Recent data suggest that ruminants in Corsica area reservoir for several Anaplasmataceae species. The purpose of our study was to determine whether Ehrlichia species could be detected in ticks collected in Corsican ruminants by using molecular methods. Ticks were collected in northern Corsica: (i) in May 2016 from sheep bred in one farm located in a 5000‐inhabitants village and (ii) from cattle in June and July 2016 in a slaughterhouse. There sheep and cattle whole skin was inspected and ticks were collected manually. A total of 647 ticks was collected in northern Corsica during this study: 556 (86%) belonged to the Rhipicephalus bursa species and 91 (14%) to Hyalomma marginatum. The 91 H. marginatum ticks were organized in 27 pools, of which one (3.7%) was found positive for the presence of E. minasensis; this pool consisted of six ticks collected from a cow bred and raised northwestern Corsica. Ehrlichial DNA was not detected in R. bursa ticks. The 16S rRNA and groEL gene sequences of Ehrlichia detected in the H. marginatum pool showed 100% (303/303 bp) and 99.8% (555/556) of nucleotide identity with E. minasensis, respectively. Phylogenetic analyses demonstrated the highest closeness with E. minasensis UFMG‐EV genotype than to any other E. canis strains. To our knowledge, this is the first report of E. minasensis outside of Brazil, Ethiopia and Canada. This identification of E. minasensis in H. marginatum merits to be further investigated and pleads for translational studies addressing the potential impact of vector‐borne diseases of human and veterinary impact through large‐scale research and surveillance programmes in Corsica.

Keywords: Ehrlichia minasensis, Hyalomma marginatum, Corsica, France

Introduction

Ehrlichiosis are severe, feverish tick‐borne illnesses caused by specific species within the genus Ehrlichia (Anaplasmataceae family) (Nicholson et al. 2010). The genus Ehrlichia consists of E. chaffeensis, E. canis, E. ewingii, E. muris and E. ruminantium, all of which are capable of causing infections in both humans and domestic animals (Rar & Golovljova 2011; Vieira et al. 2011). Ehrlichia minasensis is a recently described species most closely related with although clearly distinct from E. canis. Ehrlichia minasensis (i) was discovered in naturally infected dairy cattle and mule deer in Canada (genotype BOV2010) (Gajadhar et al. 2010), (ii) was detected in the haemolymph of Brazilian Rhipicephalus microplus ticks (Ehrlichia sp. UFMG‐EV) (Cabezas‐Cruz et al. 2016), (iii) isolated in Brazil (strain UFMT‐BV), where it proved to be pathogenic for cattle (Aguiar et al. 2014) and (iv) isolated (strain UFMG‐EV) from a partially engorged R. microplus female tick (Cabezas‐Cruz et al. 2016). Ehrlichia minasensis was established as a new species in 2016. Ehrlichia minasensis can be grown in Ixodes scapularis cell lines (ID8) and dog macrophages (DH82) (Cabezas‐Cruz et al. 2016). Corsica is a French Mediterranean island characterized by a warm‐summer Mediterranean climate with a high variability of microclimates because of peculiar geographical situation (Grech‐Angelini et al. 2016). Corsican livestock farming (sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle) is mainly of the extensive type; thus frequent interactions between livestock, wildlife and human populations favour the circulation of ticks and tick‐borne microorganisms (Grech‐Angelini et al. 2016).

Recent data suggest that ruminants in Corsica area reservoir for several Anaplasmataceae species (Dahmani et al. 2017b). Ehrlichia canis was detected once in Corsica in a non‐engorged R. bursa tick collected from a cow (Dahmani et al. 2017b). The purpose of our study was to determine whether other Ehrlichia species could be detected in ticks collected in Corsican ruminants by using molecular methods.

Materiel and methods

Ticks were collected in northern Corsica: (i) in May 2016 from sheep bred in one farm located in Corte, a 5000‐inhabitants village and (ii) from cattle in June and July 2016 in the Ponte‐Leccia slaughterhouse. There sheep and cattle whole skin was inspected and ticks were collected manually. They were identified at the species level based on taxonomic keys and morphometric tables using a binocular microscope (Estrada‐Pena et al. 2004). Morphologic identification was confirmed by mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequence analysis (Table 1) (Black & Piesman 1994). Ticks were washed once in 70% ethanol for 5 min and twice in distilled water for 5 min. Ticks collected from sheep were analysed individually. Pools consisting of 2–6 ticks collected from cattle (same species, same animal) were analysed. Ticks were crushed using the TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in a phosphate‐buffered saline solution at 2800 g for 20 s. DNA extraction was performed on a QIAcube HT (Qiagen) using QIAamp Cador Pathogen Mini kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was eluted in 150 μl of buffer and stored at −20°C. Samples were analysed by using a qPCR for detection of Ehrlichia spp. specific including a positive (Ehrlichia_spp.) and a negative control (distilled water) (genesig® Standard Kit). Ehrlichia DNA was also identified by conventional PCR using (i) tick‐borne Anaplasmataceae specific primers targeting a 345‐bp region of the 16S rRNA (Parola et al. 2001) and (ii) genus‐specific primers targeting a 590‐bp region of the heat shock protein (groEL) gene (Dahmani et al. 2017a). PCR conditions and primer sequences are described in Table 1. The reactions were carried out using a GeneAmp PCR Systems 9700 Applied Biosystems (Courtaboeuf, France). The PCR products were UV light‐visualized in 2% agarose gel in Tris‐Acetate‐EDTA (TAE Buffer) after staining with ethidium bromide. Sequences obtained in this study were deposited in the GenBank using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BankIt 3.0 submission tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/WebSub/) (accession number for H. marginatum MH663977‐83 and for R. bursa MH663984‐90). Sequences of Ehrlichia 16S rRNA and groEL genes correspond to acc. nos MH657222 and MH675614 respectively. All sequences were assembled and compared with selected homologous sequenced retrieved from the GenBank nucleotide database using BLASTn (Altschul et al. 1997). Each model was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method implemented in Mega X (Kumar et al. 2018). The bootstrap consensus tree was conducted with 1000 replicates (Felsenstein 1985).

Table 1.

Primers and probes used in this study

| Species | Target | Name | Sequence | Cycles | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional PCR* | |||||

| Ehrlichia ssp. | groEL | Ehr‐ groel‐ F | GTTGAAAARACTGATGGTATGCA | 95°C 5 min, 40 × [95°C 60 s, 50°C 60 s, 72°C 60 s], 72°C 7 min | (Dahmani et al. 2017a) |

| Ehr‐ groel‐ R | ACACGRTCTTTACGYTCYTTAAC | ||||

| 16S rRNA ** | Ehr‐16S‐D | GGTACCYACAGAAGAAGTCC | 95°C 5 min, 40 × [95°C 60 s, 55°C 60 s, 72°C 60 s], 72°C 7 min | (Parola et al. 2001) | |

| Ehr‐16S‐R | TAGCACTCATCGTTTACAGC | ||||

| Ticks | 16S rDNA | 16S+1 | CTGCTCAATGATTTTTTAAATTGCTGTGG | 95°C 5 min, 10 × [92°C 60 s, 48°C 60 s, 72°C 90 s], 32 × [92°C 60 s, 54°C 35 s, 72°C 90 s],72°C 7 min | (Black & Piesman 1994) |

| 16S‐1 | CCGGTCTGAACTCAGATCAAGT |

For each PCR reaction, the template DNA had a final concentration <200 ng.

**Primers designed to amplify a fragment of the 16S rRNA gene from bacteria within the family of Anaplasmatace.

The pathogens detected in pools were expressed as the percentage and minimum infection rate based on the assumption that each PCR‐positive pool contained at least one positive tick (Sosa‐Gutierrez et al. 2016).

Results and discussion

A total of 647 ticks was collected during this study; 586 ticks were taken from 42 cows, and the remaining 61 ticks were removed from 60 sheep. In cattle, R. bursa was the most abundant species (n = 495; 84.5%), followed by Hyalomma marginatum (n = 91; 15.5%). Ticks collected from sheep all belonged to the R. bursa species. The 586 ticks collected in cattle were organized as 127 pools consisting of 100 pools of R. bursa and 27 pools of H. marginatum. Ehrlichial DNA was detected neither in the 61 R. bursa ticks from sheep, not in the 100 pools of R. bursa collected from cattle.

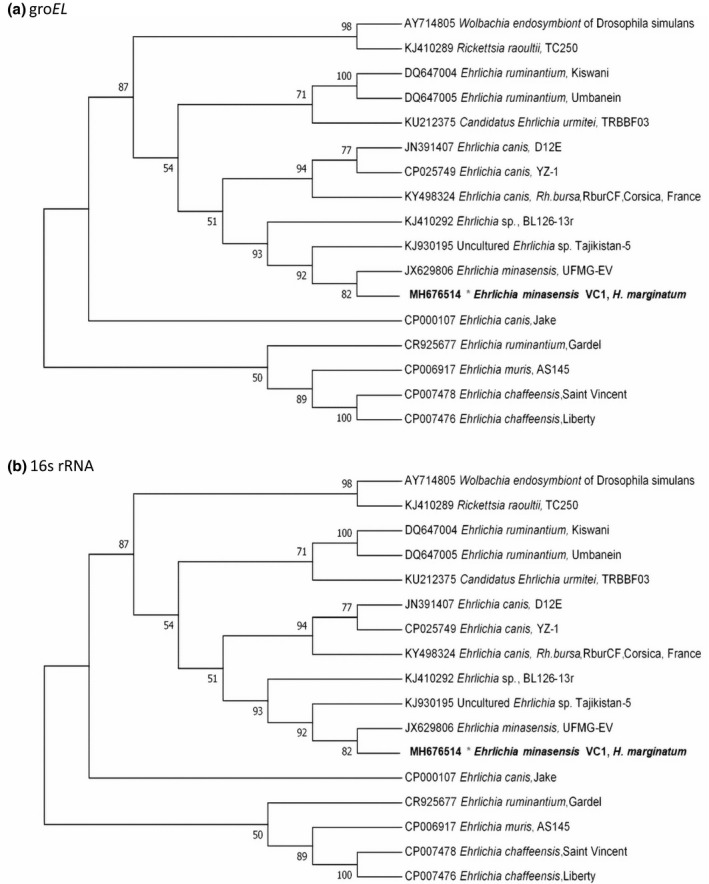

Ehrlichial DNA (16S rRNA and groEL) was detected in one of the 27 pools (3.7%) of H. marginatum ticks collected from cattle. This pool consisted of six ticks collected from an animal raised in a county of northwestern Corsica. The 16S rRNA sequence of Ehrlichia showed 100% identity (303/303 bp) with E. minasensis strain (JX629805) and 99% of identity with E. canis TWN (GU810149.1). The 556‐bp groEL gene sequence showed 99.8% identity (555/556 bp) with the homologous sequence of E. minasensis strain UFMG‐EV (JX629806) and 97% of identity (521/554 bp) with the E. canis strain previously described in Corsica (KY498324). These values were closed to those obtained by comparing the 16S rRNA and groEL gene sequences of Ehrlichia sp. UMFG‐EV to E. canis TWN (98.3% and 97.2% respectively) (Cabezas‐Cruz et al. 2016). Phylogenetic analyses proved that our Corsican strain was most closely related with E. minasensis UFMG‐EV than to E. canis strains (Fig. 1) (Cabezas‐Cruz et al. 2016).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic position of Ehrlichia minasensis detected in the Hyalomma marginatum pool collected on cattle in Corsica using groEL (a) and 16S rRNA (b). All sequences were assembled and compared with homologous sequenced retrieved from the GenBank nucleotide database using BLASTn (Altschul et al. 1997). The Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano and the Tamura 3‐parameter models were identified as the best‐fit models under the Akaike Information Criterion, for 16Sr RNA and groEL sequences respectively. Each model was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method implemented in Mega X (Kumar et al. 2018). The bootstrap consensus tree was conducted with 1000 replicates (Felsenstein 1985).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of E. minasensis in Corsica after recent identification in the Americas (Cabezas‐Cruz et al. 2016). In agreement with previous phylogenetic analyses, we observed that E. minasensis is a sister taxa of E. canis. This is also the first description of E. minasensis in H. marginatum tick. So far, it has been reported in haemolymph of R. microplus ticks (Cabezas‐Cruz et al. 2016), and in blood of an apparently healthy cattle in Ethiopia, where R. microplus is not described (Hailemariam et al. 2017). Interestingly, H. marginatum is present in Ethiopia (ECDC.EUROPA.EU, 2018).

The role of H. marginatum in the transmission of E. minasensis remains unknown. The presence of a bacterium in an engorged tick could be due to the presence in the blood meal. The presence of H. marginatum in Corsica, endemic in southern Europe, was previously reported (Matsumoto et al. 2004; Grech‐Angelini et al. 2016). At the outset of this study, H. marginatum ticks collected in Corsica from ruminants had never been detected positive through PCR for microorganisms belonging to Anaplasmataceae (Dahmani et al. 2017b). Identification of E. minasensis in H. marginatum merits to be further investigated and pleads for translational studies addressing the potential impact of vector‐borne diseases of human and veterinary impact through large‐scale research and surveillance programmes in Corsica.

Source of funding

This work was supported by the Corsican Territorial Collectivity and the University of Corsica.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of the work have no conflict of interests to disclose.

Ethical statement

No ethical approval was required, as this study does not involve clinical trials or experimental procedures. The cattle inspected were slaughtered for human consumption. The slaughterhouse staff gave permission to collect ticks from the whole skins of animals. This study did not involve endangered or protected species.

Contributions

VC and AF conceived the study,analysed data and draft the manuscript . SM microbiological diagnosis of bacteria. CL and VC collected ticks. XdL and RC draft the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Corsican Territorial Collectivity and the University of Corsica.

References

- Aguiar D.M., Ziliani T.F., Zhang X., Melo A.L., Braga I.A., Witter R. et al (2014) A novel Ehrlichia genotype strain distinguished by the TRP36 gene naturally infects cattle in Brazil and causes clinical manifestations associated with ehrlichiosis. Ticks Tick Borne Diseases 5, 537–544. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W. & Lipman D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI‐BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Research 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black W.C.T & Piesman J. (1994) Phylogeny of hard‐ and soft‐tick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91, 10034–10038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas‐Cruz A., Zweygarth E., Ribeiro M.F.B., da Silveira J.A.G., de la Fuente J., Grubhoffer L. et al (2016) Ehrlichia minasensis sp. nov., isolated from the tick Rhipicephalus microplus. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 66, 1426–1430. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmani M., Davoust B., Rousseau F., Raoult D., Fenollar F. & Mediannikov O. (2017a) Natural Anaplasmataceae infection in Rhipicephalus bursa ticks collected from sheep in the French Basque Country. Ticks Tick Borne Diseases 8, 18–24. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmani M., Davoust B., Tahir D., Raoult D., Fenollar F. & Mediannikov O. (2017b) Molecular investigation and phylogeny of Anaplasmataceae species infecting domestic animals and ticks in Corsica, France. Parasites Vectors 10, 302 10.1186/s13071-017-2233-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECDC.EUROPA.EU . (2018) Hyalomma marginatum, factsheet from experts. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/disease-vectors/facts/tick-factsheets/hyalomma-marginatum.

- Estrada‐Pena A., Bouattour A., Camicas J.L., Walker A.R. (2004). Ticks of veterinary and medical importance: the Mediterranean basin. A guide of identification of species.

- Felsenstein J. (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajadhar A.A., Lobanov V., Scandrett W.B., Campbell J. & Al‐Adhami B. (2010) A novel Ehrlichia genotype detected in naturally infected cattle in North America. Veterinary Parasitology 173, 324–329. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grech‐Angelini S., Stachurski F., Lancelot R., Boissier J., Allienne J.F., Marco S. et al (2016) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting cattle and some other domestic and wild hosts on the French Mediterranean island of Corsica. Parasites Vectors 9, 582. 10.1186/s13071-016-1876-8. DOI:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailemariam Z., Krucken J., Baumann M., Ahmed J.S., Clausen P.H. & Nijhof A.M. (2017) Molecular detection of tick‐borne pathogens in cattle from Southwestern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 12, e0188248 10.1371/journal.pone.0188248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C. & Tamura K. (2018) MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35, 1547–1549. 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K., Parola P., Brouqui P. & Raoult D. (2004) Rickettsia aeschlimannii in Hyalomma ticks from Corsica. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 23, 732–734. 10.1007/s10096-004-1190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson W.L., Allen K.E., McQuiston J.H., Breitschwerdt E.B. & Little S.E. (2010) The increasing recognition of rickettsial pathogens in dogs and people. Trends in Parasitology 26, 205–212. 10.1016/j.pt.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola P., Inokuma H., Camicas J.L., Brouqui P. & Raoult D. (2001) Detection and identification of spotted fever group Rickettsiae and Ehrlichiae in African ticks. Emerging Infectious Diseases 7, 1014–1017. 10.3201/eid0706.010616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rar V. & Golovljova I. (2011) Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, and “Candidatus Neoehrlichia” bacteria: pathogenicity, biodiversity, and molecular genetic characteristics, a review. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 11, 1842–1861. 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa‐Gutierrez C.G., Vargas‐Sandoval M., Torres J. & Gordillo‐Perez G. (2016) Tick‐borne rickettsial pathogens in questing ticks, removed from humans and animals in Mexico. Journal of Veterinary Science 17, 353–360. 10.4142/jvs.2016.17.3.353jvs.2015.086[pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira R.F., Biondo A.W., Guimaraes A.M., Dos Santos A.P., Dos Santos R.P., Dutra L.H. et al (2011) Ehrlichiosis in Brazil. The Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 20, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]