Abstract

Background

While recent years have seen a revolution in the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma, no treatment has yet been able to demonstrate any prolonged survival in metastatic uveal melanoma. Thus, metastatic uveal melanoma remains a disease with an urgent unmet medical need. Reports of treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors have thus far been disappointing. Based on animal experiments, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the effect of immunotherapy may be augmented by epigenetic therapy. Proposed mechanisms include enhanced expression of HLA class I and cancer antigens on cancer cells, as well as suppression of myeloid suppressor cells.

Methods

The PEMDAC study is a multicenter, open label phase II study assessing the efficacy of concomitant use of the PD1 inhibitor pembrolizumab and the class I HDAC inhibitor entinostat in adult patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Primary endpoint is objective response rate. Eligible patients have histologically confirmed metastatic uveal melanoma, ECOG performance status 0–1, measurable disease as per RECIST 1.1 and may have received any number of prior therapies, with the exception of anticancer immunotherapy. Twenty nine patients will be enrolled. Patients receive pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously every third week in combination with entinostat 5 mg orally once weekly. Treatment will continue until progression of disease or intolerable toxicity or for a maximum of 24 months.

Discussion

The PEMDAC study is the first trial to assess whether the addition of an HDAC inhibitor to anti-PD1 therapy can yield objective anti-tumoral responses in metastatic UM.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov registration number: NCT02697630. (Registered 3 March 2016). EudraCT registration number: 2016–002114-50.

Keywords: Uveal melanoma, Metastatic, Immunotherapy, Programmed cell death 1 receptor, Pembrolizumab, Epigenetics, Histone deacetylase inhibitors, Entinostat

Background

Uveal malignant melanoma (UM) is a disease that differs biologically from cutaneous melanoma. Uveal melanoma is a tumor in the eye arising from melanocytes in the uveal tract. It is most common in the choroidea (90%), but can also be found in the ciliary body (7%) and in the iris (3%) [1]. In Europe, the incidence shows a gradient from north-to-south, decreasing from over 8–9 per million in Scandinavia to less than 2 per million in the southern European countries [2, 3]. The incidence is increasing with age, and the median age at the time of diagnosis is about 60 years [4]. At the time of initial diagnosis, only 2–4% of all patients have metastatic disease [5] and many are cured from their primary tumor with initial surgical resection or radiotherapy of the eye. Very often the initial treatment results in low vision on the afflicted eye, reducing quality of life for these patients. Even worse, up to 50% of the patients will develop metastatic disease, most commonly with isolated liver metastases (89%), with a median survival of 6–12 months [5, 6]. Patients with metastases outside of the liver only, or when the liver is not the first site, seem to have a better survival [7]. For patients with liver metastases, regardless of treatment, the mortality rate is approximately 90% at 2 years with only about 1% of the patients surviving more than 5 years [6].

Currently explored treatment strategies for metastatic UM include liver directed therapies, chemotherapy, targeted therapies and immunotherapy. For patients with isolated liver metastases, liver directed therapies such as radiofrequency ablation, isolated hepatic perfusion (IHP) or percutan isolated hepatic perfusion (PHP), can induce objective responses, but a clear survival benefit has not been shown in prospective studies, although trials are ongoing [8].

The predominant mutations present in uveal melanoma are in GNAQ or the mutually exclusive GNA11 gene, which are mutated in 90% of uveal melanomas. In the remaining 10%, recurrent mutations can be seen in CYSLTR2 and PLCB4 [9, 10]. GNAQ/11 mutations result in activation of the Hippo and MAP-kinase pathways [11, 12]. Although the pathways have been delineated, a targeted therapy against GNAQ/GNA11 oncogenic driver mutations is lacking. Instead, attempts to target the downstream signaling pathways through inhibition of e.g. MEK or PKC have thus been tested, but not yet demonstrated clinical efficacy [13]. Another common genetic alteration in UM is inactivation or loss of the BAP1 tumor suppressor gene, which results in metastatic progression [14].

Results of checkpoint blockade in patients with metastatic UM have so far been disappointing in the limited number of patients reported [15]. There are indeed scientific concerns raised about the feasibility of therapies such as those targeting Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Associated Protein 4 (CTLA-4) and/or Programmed cell Death protein 1 (PD-1). The eye is an immune privileged site and it is well known that primary uveal melanoma often has a reduced HLA class I expression. Low HLA expression can trigger NK cell lysis and high expression of HLA in the primary site is associated with worse prognosis [16]. If the low HLA expression, hampering recognition of cytotoxic T-cells and effective immunotherapies, is conserved in metastases has not been sufficiently studied. Unfortunately, there are no accurate animal models of GNAQ/11 mutated uveal melanoma which develop liver metastases, and biopsies from metastases, e.g. from the liver, have not been adequately characterized. Beyond checkpoint inhibition, other strategies for immunotherapy in UM include IMCgp100, a bispecific biological drug showing promising activity in early phase studies [17], and adoptive cell therapy with tumor infiltrating lymphocytes [18].

There have been several clinical trials with different kinds of chemotherapy, targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and liver directed therapies. Unfortunately, the median survivals reported in these trials do not differ from the anticipated survival of 6–12 months in patients not receiving antitumoral therapy [19]. Thus, there are strong arguments to investigate if anti-PD1 therapy can be effective in metastatic UM. However, the poor immunogenicity of uveal melanoma may interfere with the efficacy of anti-PD1 therapy, and published case series with PD1-inhibitors in monotherapy show very low response rates [15]. There is however emerging preclinical data indicating that the effect of immunotherapy may be augmented by epigenetic therapy [20]. For instance histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors have been shown to a) enhance expression of HLA class I on cancer cells [21], b) trigger cell death recruiting immune cells [22], c) trigger DNA damage of uveal melanoma cells resulting in activation of danger signals [23], d) block myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) activity [24], and e) enhance the expression of cancer antigens silenced by immunoediting [25]. On the other hand, HDAC inhibitors also induce PD-L1 [26]. Therefore, addition of a PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor to HDAC inhibitors enhance the effect compared to monotherapy in vitro and in syngenic animal models [26, 27]. In particular, the HDAC inhibitor entinostat (MS-275) was demonstrated to enable durable responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors even when mice carried large tumors [24]. Given the poor responses to PD1 inhibitors in patients with UM, we hypothesize that an epigenetic therapy using entinostat could enhance the effect of PD1 inhibitor pembrolizumab in human patients.

Little is known about the toxicity of combined HDAC- and PD1-inhibition. In monotherapy, entinostat gives rise to manageable hematological and non-hematological toxicities, few of which are overlapping with those associated with PD1-inhibitors [28]. The dosing is based on results from the dose escalation cohort of an ongoing phase Ib/II trial of entinostat and pembrolizumab in other solid tumors (NCT02437136). According to interim data from the cutaneous melanoma expansion cohort of the same study, there are no obvious signs of synergistic toxic effects [29].

Methods

Study design

The PEMDAC study is a prospective multicenter, non-randomized, open label study, in which patients with stage IV UM are concomitantly treated with pembrolizumab 200 mg administered intravenously every third week and entinostat 5 mg administered orally once weekly.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint is objective response rate (ORR) according to RECIST 1.1 criteria [30].

Secondary endpoints include

Clinical benefit rate (CBR) (as of RECIST version 1.1 criteria): stable disease (SD) at 18 weeks OR any objective response

Progression free survival (PFS)

Overall survival (OS)

Best overall response (BOR)

Time to response (TTR)

Duration of objective response (DOR)

Incidence and severity of adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs)

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance status (PS). Change from baseline in the ECOG PS at 18 weeks

Changes in Quality of Life (QoL)

Exploratory endpoints include

Radiological response (ORR, PFS) by immune related RECIST 1.1 criteria (irRECIST) [31]

ORR in association with biomarker expression

ORR in subgroups determined by to PD-L1 expression, serum LDH level, GNAQ/GNA11 mutation status and presence of extra-hepatic metastases

Changes in number of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and T-cell differentiation in peripheral blood and tumor biopsies pre- and post-therapy

Changes in HLA expression in tumor biopsies pre- and post-therapy

Changes in expression of immune checkpoint proteins in tumor biopsies pre- and post-therapy

Changes in molecular characteristics of uveal melanoma metastases when treated with entinostat and pembrolizumab

Study population

The investigated cohort of patients includes both untreated and previously treated patients.

Key inclusion criteria include

Age above 18 years

Signed and dated written informed consent before the start of specific protocol procedures

ECOG PS 0–1

Histologically/cytologically confirmed stage IV UM

Measurable disease by computed tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) per RECIST 1.1 criteria

Any number of prior therapies (including none), with the exception of anticancer immunotherapy

Key exclusion criteria include

Active brain metastases (symptomatic and/or requiring corticosteroids) or leptomeningeal metastases

Previous treatment with anticancer immunotherapy

Pregnant or nursing (lactating) women

Medical, psychiatric, cognitive or other conditions that may compromise the patient’s ability to understand the patient information, give informed consent, comply with the study protocol or complete the study

Active autoimmune disease

Immune deficiency or treatment with systemic corticosteroids (> 10 mg daily prednisone equivalents).

Use of other investigational drugs (drugs not marketed for any indication) within 4 weeks before study drug administration

Life expectancy of less than 3 months

Treatments and evaluation

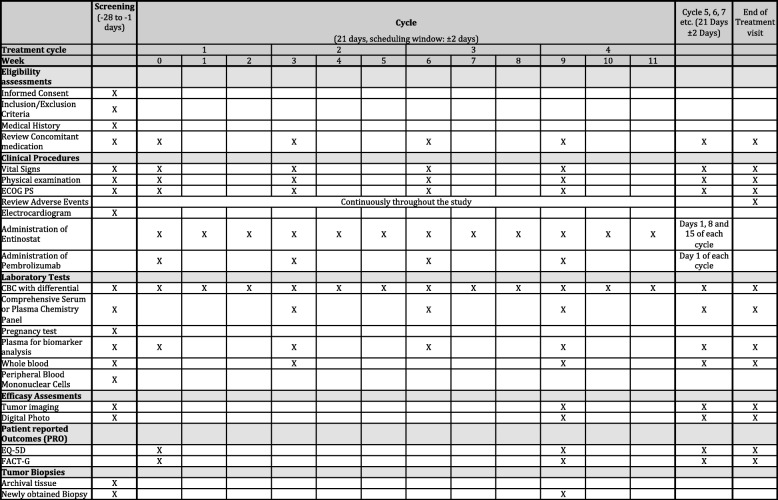

A schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments

Dosing and administration

Entinostat is to be taken on an empty stomach, at least 2 h after a meal and at least 1 h before the next meal. If an entinostat dose is missed, it may be taken up to 48 h after the scheduled dosing time. If it is not taken within the 48-h window, the dose should not be taken and should be counted as a missed dose. The patient should take the next scheduled dose per protocol. If entinostat is vomited, dosing should not be re-administered but instead the dose should be skipped.

Efficacy assessments

The subjects will be followed for 2 years. Study visits will be carried out at baseline, and week 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21 and every 3 weeks until 24 months.

MRI or CT (as preferred by the investigator) of chest and abdomen will be carried out every 9 weeks

EQ5D Quality of Life questionnaire at scheduled visit baseline and then every 9 weeks until 24 months

Blood samples of biomarkers will be collected at every scheduled visit

Safety and tolerability

The subjects will be followed for 2 years. Study visits will be carried out at baseline, and week 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21 and every 3 weeks until 24 months. All AEs and SAEs will be collected. At all visits the following tests will be performed: Blood samples (Hgb, WBC, Plt, INR, APTT, AST, ALT, ALP, Bilirubin, LDH, TSH, free-T4/free-T3, Creatinine and electrolytes).

Duration

Study treatment will be continued until documented disease progression, intolerable side effects, patient’s withdrawal of consent or decision of the investigating physician to end treatment, or to a maximum of 2 years. The subject is free to withdraw from the study for any reason and at any time without giving reason for doing so and without penalty or prejudice. The investigator is also free to terminate a subject’s study treatment at any time if the subject’s clinical condition warrants it.

Discontinuation Criteria for Individual Subjects:

Inappropriate enrollment (violation of Inclusion/Exclusion criteria).

Withdrawal of consent.

Progression of disease.

Discontinuation of study drugs due to AE.

Treatment beyond radiological progression

Due to the unique tumor response characteristics seen with treatment with immunotherapy, standard RECIST 1.1 may not provide an accurate response assessment. Modifications to RECIST 1.1 Criteria (irRECIST) takes into account these patterns of atypical response and enable treatment beyond initial radiographic progression. IrRECIST will therefore be used for assessment of tumor response for managing subjects on protocol treatment and decision making for discontinuation of study therapy due to disease progression. If imaging shows PD, it is at the discretion of the investigator to keep a patient on study treatment or to stop study treatment until imaging is repeated approximately 4 weeks later in order to confirm PD, as described in the irRECIST recommendations [31]. Patients that are deemed clinically unstable or who have biopsy proven new metastatic lesions are not required to have repeat imaging for confirmation. This decision will be based on clinical judgment of a patient’s overall clinical condition, including performance status, clinical symptoms, and laboratory data. At a minimum, patients must meet the following criteria for continued treatment on study after disease progression is identified at a tumor assessment:

Absence of new or worsening symptoms

No decline in ECOG performance status

Absence of rapid progression of disease or of

Absence of progressive tumor at critical anatomical sites (e.g., cord compression) requiring urgent alternative medical intervention

Statistical considerations

The sample size and power estimation is based on the primary endpoint ORR, only. Power is required to be 80%, Significance is generally set to 5%. We assume that an ORR of 5% is not a clinically relevant treatment effect, whereas 20% is sufficient to consider the treatment useful. Enrollment will continue until the required sample size has been reached. Patients will be enrolled in two batches, first consisting of 10 patients and the second group of 19. The second sample will not be recruited if the result from the 10 first is considered inadequate. This is the optimal allocation according to Simon’s Optimal Two Stage Design (significance level = 5% (one-sided)) [32]. If no objective responses (CR or PR) are reported after the first stage of 10 patients, the study is interrupted early for futility. The expected number of patients is estimated to 17.6. Outcome measures that are proportions will be reported using a 95% confidence interval. Since the sample size is small an exact method will be used. If applicable, tests are conducted versus zero or highest non-efficient value.

The primary and secondary outcomes can be divided into the following groups:

Proportions of successful events: ORR, CBR, BOR, Incidence of AE, ECOG PS

Time to event: OS, PFS, TTR, DOR

Others: QoL difference to baseline

Analysis of proportions

Outcome measures that are proportions will be reported using a 95% confidence interval. Since the sample size is small an exact method will be used. If applicable, tests are conducted versus zero or highest non-efficient value.

Analysis of time to event

Outcome measures that are times to various events will be analyzed using non-parametric methods. Time is summarized using medians, together with 95% confidence intervals. If applicable, test is conducted versus zero or highest non-efficient value. Results are graphically presented using Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

Quality of life (QoL) difference from baseline

QoL difference will be analyzed using non-parametric methods, e.g. Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test.

Discussion

Metastatic UM represents a major unmet medical need in oncology. Being a rare disease and of low commercial value, drug discovery in UM is of lower priority by the pharmaceutical industry. The PEMDAC study is the first trial to assess whether the addition of an HDAC inhibitor to anti-PD1 therapy can yield objective anti-tumoral responses in metastatic UM. The study is investigator initiated, is carried out at the major Swedish University hospitals (with the possibility of referrals from other community and academic hospitals) and is coordinated by the Swedish Melanoma Study Group (SMSG).

One aim of the PEMDAC trial is to include a study population representative of that seen in the clinic, thus applying generous eligibility criteria including the allowance for any number of previous therapies. This approach risks generating a heterogeneous study population, but is in our view justified by the urgent medical need in metastatic UM and the prospect to include a sufficient number of patients during a reasonable recruitment period.

All investigators in the trial have substantial experience in the management of immune related adverse events associated with immunotherapy.

The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP)/European Medicines Agency (EMA) has in 2017 presented “Guideline on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man” and suggests ORR to be used as primary endpoint in exploratory single armed studies as in the present study. However, since the conception and approval of PEMDAC, there is data suggesting that ORR might be challenged as the most appropriate primary endpoint for phase II studies of immunotherapy in cancer, as it risks underestimating the treatment benefit. A retrospective analysis of phase II immunotherapy trials in cancer showed that PFS at 6 months might be a better correlate for OS in this setting [33]. Furthermore, modified RECIST criteria (irRECIST) have been developed to account for the unconventional response characteristics associated with immunotherapies [31]. Progression free survival (including landmark analysis) and ORR according to irRECIST will be analysed as secondary endpoints. However, these alternative surrogate endpoints have not yet been validated in prospective studies across tumor types. Furthermore, pseudoprogression appears to be uncommon using PD1-inhibitors, and the benefit of durable conventional objective response remains undisputed. We believe that the present study design is appropriate to investigate whether there are observations of clinically relevant efficacy from combined HDAC- and PD1-inhibition in UM patients, to warrant further investigation in larger cohorts.

With 29 patients, the present study represents a significant cohort of patients with this very rare disease. An important aim of the study is therefore explorative analyses, with the aim of increasing our understanding of the immunological and genetic nature of UM, and possibly to detect markers predictive for response.

Trial status

The trial started enrolment of patients in February 2018, and recruited patients are in active treatment phase or follow-up. An updated trial status will be continuously displayed at Clinicaltrials.gov. The primary endpoint will be assessed 6 months after last patient first visit. Key efficacy and safety results will be reported thereafter, preliminary late 2019. Latest protocol version and date: 1.4, 2018-06-29.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Magnus Petterson at Statistikkonsulterna for statistical support. Anette Ericsson, Erén Svensson and Annika Baan at the Clinical Trial Unit, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, for administrative support. Carola Andersson, Department of Pathology and Genetics, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, for valuable technical support. We thank especially Dr. Karin Söderbärg, MSD Sweden, Dr. Scott Diede, Merck & Co Inc. and Ms. Yvette Ng and Dr. Michael Meyers, Syndax Pharmaceuticals for valuable operational support in the initiation of the study.

Funding

The study has received financial support from Syndax Pharmaceuticals and is supported in part by a research grant from the Investigator Initiated Studies Program of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. Additional funding comes from the Swedish Cancer Society, King Gustav V Jubilee Clinic Research Foundation, Lion’s Cancer Foundation West, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Erling-Persson Family Foundation and BioCARE, a National Strategic Research Program at the University of Gothenburg.

Syndax Pharmaceuticals and MSD have reviewed the research protocol but will have no role in data collection, analysis, data interpretation, report writing or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable as the trial is ongoing and no results are reported.

Sponsor

Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Västra Götaland region, Sweden.

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse event

- BOR

Best overall response

- CBR

Clinical benefit rate

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4

- DOR

Duration of objective response

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

- IHP

Isolated hepatic perfusion

- irRECIST

Immune related RECIST 1.1 criteria

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall Survival

- PD-1

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PFS

Progression free survival

- PS

Performance status

- QoL

Quality of life

- SAE

Serious adverse event

- SD

Stable disease

- SMSG

Swedish melanoma study group

- TTR

Time to response

- UM

Uveal malignant melanoma

Authors’ contributions

Concept: HJ, LMN, JAN and LN. Study design: HJ, ROB, GU, AC, HH, IL, ML, CAE, BA, US, JAN and LN. All authors have made substantial contributions in drafting the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study is approved by the regional Ethics Board of Gothenburg, approval number 692–16. Signed and dated informed consent will be obtained from each patient in accordance with the principles of ICH-GCP and the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

ROB, GU, IL, US, ML and LN have had a paid consulting or advisory role with MSD, Sweden. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Damato B. Treatment of primary intraocular melanoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:493–506. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergman L, Seregard S, Nilsson B, Ringborg U, Lundell G, Ragnarsson-Olding B. Incidence of uveal melanoma in Sweden from 1960 to 1998. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2579–2583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virgili G, Gatta G, Ciccolallo L, Capocaccia R, Biggeri A, Crocetti E, Lutz J-MM, Paci E, group E Incidence of uveal melanoma in Europe. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2309–2315. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eskelin S. Mode of presentation and time to treatment of uveal melanoma in Finland. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2002;86(3):333–338. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kujala E, Makitie T, Kivela T. Very long-term prognosis of patients with malignant uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4651–4659. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, Caldwell R, Cumming K, Earle JD, Hawkins BS, Hayman JA, Jaiyesimi I, Jampol LM. Development of metastatic disease after enrollment in the COMS trials for treatment of choroidal melanoma: collaborative ocular melanoma study group report no. 26. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1639–1643. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.12.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kath R, Hayungs J, Bornfeld N, Sauerwein W, Höffken K, Seeber S. Prognosis and treatment of disseminated uveal melanoma. Cancer. 1993;72:2219–2223. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931001)72:7<2219::AID-CNCR2820720725>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olofsson R, Ny L, Eilard MS, Rizell M, Cahlin C, Stierner U, Lonn U, Hansson J, Ljuslinder I, Lundgren L, et al. Isolated hepatic perfusion as a treatment for uveal melanoma liver metastases (the SCANDIUM trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:317. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore AR, Ceraudo E, Sher JJ, Guan Y, Shoushtari AN, Chang MT, Zhang JQ, Walczak EG, Kazmi MA, Taylor BS, et al. Recurrent activating mutations of G-protein-coupled receptor CYSLTR2 in uveal melanoma. Nat Genet. 2016;48:675–680. doi: 10.1038/ng.3549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson P, Aoude LG, Wadt K, Glasson WJ, Warrier SK, Hewitt AW, Kiilgaard JF, Heegaard S, Isaacs T, Franchina M, et al. Deep sequencing of uveal melanoma identifies a recurrent mutation in PLCB4. Oncotarget. 2016;7:4624–4631. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, Bauer J, Gaugler L, O’Brien JM, Simpson EM, Barsh GS, Bastian BC. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature. 2009;457:599–602. doi: 10.1038/nature07586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, Garrido MC, Vemula S, Wiesner T, Obenauf AC, Wackernagel W, Green G, Bouvier N, et al. Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2191–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carvajal RD, Piperno-Neumann S, Kapiteijn E, Chapman PB, Frank S, Joshua AM, Piulats JM, Wolter P, Cocquyt V, Chmielowski B, et al. Selumetinib in combination with Dacarbazine in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma: a phase III, multicenter, randomized trial (SUMIT) J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1232–1239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, Duan S, Cao L, Worley LA, Council ML. Matatall KA, Helms C, Bowcock AM. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010;330:1410–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.1194472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Algazi AP, Tsai KK, Shoushtari AN, Munhoz RR, Eroglu Z, Piulats JM, Ott PA, Johnson DB, Hwang J, Daud AI, et al. Clinical outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with PD-1 and PD-1L antibodies. Cancer. 2016;122:3344–3353. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ericsson C, Seregard S, Bartolazzi A, Levitskaya E, Ferrone S, Kiessling R, Larsson O. Association of HLA class I and class II antigen expression and mortality in uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2153–2156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato Takami, Nathan Paul D., Hernandez-Aya Leonel Fernando, Sacco Joseph J, Orloff Marlana M., Truscello Jessica, McAlpine Cheryl, Hulstine Ann-Marie, Lanasa Mark C., Coughlin Christina Marie, Carvajal Richard D. Intra-patient escalation dosing strategy with IMCgp100 results in mitigation of T-cell based toxicity and preliminary efficacy in advanced uveal melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(15_suppl):9531–9531. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.9531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandran SS, Somerville RP, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Klebanoff CA, Goff SL, Wunderlich JR, Danforth DN, Zlott D, Paria BC, et al. Treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma with adoptive transfer of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes: a single-Centre, two-stage, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:792–802. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang J, Manson DK, Marr BP, Carvajal RD. Treatment of uveal melanoma: where are we now? Ther adv med oncol. 2018;10:1–17. doi: 10.1177/1758834018757175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weintraub K. Take two: combining immunotherapy with epigenetic drugs to tackle cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22:8–10. doi: 10.1038/nm0116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campoli M, Ferrone S. HLA antigen changes in malignant cells: epigenetic mechanisms and biologic significance. Oncogene. 2008;27:5869–5885. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landreville S, Agapova OA, Matatall KA, Kneass ZT, Onken MD, Lee RS, Bowcock AM, Harbour WJ. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce growth arrest and differentiation in uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:408–416. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JH, Choy ML, Ngo L, Foster SS, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitor induces DNA damage, which normal but not transformed cells can repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14639–14644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008522107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim K, Skora AD, Li Z, Liu Q, Tam AJ, Blosser RL, Diaz LA, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhou S. Eradication of metastatic mouse cancers resistant to immune checkpoint blockade by suppression of myeloid-derived cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:11774–11779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410626111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maio M, Coral S, Fratta E, Altomonte M, Sigalotti L. Epigenetic targets for immune intervention in human malignancies. Oncogene. 2003;22:6484–6488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woods DM, Sodre AL, Villagra A, Sarnaik A, Sotomayor EM, Weber J. HDAC inhibition upregulates PD-1 ligands in melanoma and augments immunotherapy with PD-1 blockade. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1375–1385. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0077-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Booth L, Roberts JL, Poklepovic A, Kirkwood J, Dent P. HDAC inhibitors enhance the immunotherapy response of melanoma cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:83155–83170. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hauschild A, Trefzer U, Garbe C, Kaehler K, Ugurel S, Kiecker F, Eigentler T, Krissel H, Schadendorf D. A phase II multicenter study on the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor MS-275, comparing two dosage schedules in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24 (abstr 8044).

- 29.Agarwala Sanjiv S., Moschos Stergios J., Johnson Melissa Lynne, Opyrchal Mateusz, Gabrilovich Dmitry, Danaher Patrick, Wang Fang, Brouwer Susan, Ordentlich Peter, Sankoh Serap, Schmidt Emmett V., Meyers Michael L., Sullivan Ryan J. Efficacy and safety of entinostat (ENT) and pembrolizumab (PEMBRO) in patients with melanoma progressing on or after a PD-1/L1 blocking antibody. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(15_suppl):9530–9530. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.9530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishino M, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gargano M, Suda M, Ramaiya NH, Hodi FS. Developing a common language for tumor response to immunotherapy: immune-related response criteria using unidimensional measurements. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3936–3943. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Controlled clin trials. 1989;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritchie G, Gasper H, Man J, Lord S, Marschner I, Friedlander M, Lee CK. Defining the Most appropriate primary end point in phase 2 trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors for advanced solid cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA oncol. 2018;4:522–528. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable as the trial is ongoing and no results are reported.