Abstract

Prokaryotic plasmids and chromosomes encode partitioning (par) loci that segregate DNA to daughter cells before cell division. Recent database analyses showed that almost all known par loci encode an ATPase and a DNA-binding protein, and one or more cis-acting regions where the proteins act. All par-encoded ATPases belong to one of two protein superfamilies, Walker-type and actin-like ATPases. This property was recently used to divide par loci into Types I and II loci. We show here that the Escherichia coli virulence factor pB171 encodes a double par locus that consists of one Type I and one Type II locus. Separately, each locus stabilized a test-plasmid efficiently. Together, the two loci mediated even more efficient plasmid stabilization. The par loci have a unique genetic organization in that they share a common central region at which the two different DNA-binding proteins probably act. Interestingly, a fusion protein consisting of the Walker-type ParA ATPase and Gfp was functional and oscillated in nucleoid regions on a time scale of minutes. ParA-green fluorescent protein (Gfp) oscillation depended on both ParB and parC but was independent of minCDE. Point mutations in the Walker A box motif simultaneously abolished plasmid stabilization and ParA-Gfp oscillation. These observations raise the possibility that ParA oscillation is prerequisite for active plasmid segregation.

Keywords: ATPase‖Gfp‖partitioning‖plasmid segregation

Prokaryotic plasmids and chromosomes specify functions that ensure segregation of DNA molecules before cell division (1–4). Plasmid- and chromosome-encoded partitioning (par) loci encode two trans-acting proteins, usually called ParA and ParB, and one or more cis-acting DNA regions where the proteins act (denoted parS or parC). ParB proteins interact with the cis-acting sites and with ParA proteins. In all cases investigated, ParA proteins possess ATPase activity (5–9). Although both plasmid-encoded and, more recently, also chromosome-encoded par loci have been analyzed thoroughly, the molecular mechanisms behind active DNA movement in prokaryotes have remained elusive.

The ParA proteins belong to two different superfamilies of ATPases, and recently this property was used to divide plasmid-encoded partitioning loci into two types (4). Type I loci encode ATPases containing the so-called deviant Walker-type motif also found in MinD proteins (10). All chromosome- and almost all plasmid-encoded partitioning loci encode this type of ATPase, and more than 100 ParA homologous proteins can now be retrieved from the databases (4, 11, 12). The function of the ATPases in plasmid segregation is not known. However, the par loci of P1 and F position plasmid copies subcellularly in a nonrandom fashion (13–15), and the positioning depends on the Walker-type ATPases (ParA and SopA). In most cells, par-encoding plasmids were located either at mid- or quarter-cell positions. The quarter-cell position is the future midcell in the next cell generation. Thus, during progression of the cell cycle, the ATPases of F and P1 seem to be required for relocalization of plasmids from mid- to quarter-cell positions.

Type II partitioning loci encode actin-like ATPases (9, 16). The model locus par of plasmid R1 encodes the actin-like ParM ATPase and the DNA-binding ParR protein. The cis-acting parC region is located upstream of the parMR operon and contains 10 direct repeats to which ParR binds (17–20). ParM interacts with ParR in vitro when ParR is bound to parC-DNA (9, 20). In the case of par of R1, plasmid copies also localize nonrandomly. Thus, par-encoding plasmid copies were positioned either at midcell or close to the cell poles (21). This nonrandom subcellular positioning depended on ParM. The DNA-binding protein ParR mediates pairing of plasmid molecules at parC in vitro (20). This information, combined with the symmetrical pattern of plasmid localization in vivo, suggests that plasmid molecules are replicated at midcell, become paired via ParR/parC (21), and then move in opposite directions toward the cell poles.

The specific DNA regions at which ParB/ParR proteins bind also exert partition-related incompatibility. For example, if parC of plasmid R1 is present on a high-copy-number plasmid in a strain also carrying a plasmid stabilized by par of R1, then the R1 plasmid becomes unstable (17, 19). The mechanism of this interference phenomenon is not known. The high-copy plasmid carrying parC could exert incompatibility directly; for example, heterologous pairing with the R1 plasmid might interfere with proper sister plasmid segregation. Alternatively, titration of ParR by parC might interfere with proper par function.

Here we show that the Escherichia coli virulence plasmid pB171 encodes two different par loci that both mediate plasmid stabilization. Genetic experiments indicate that the two par loci share a common central cis-acting region. Interestingly, a ParaA-green fluorescent protein (Gfp) fusion protein localized to nucleoid regions and oscillated within the nucleoid regions. Oscillation depended on the presence of the other components of the par locus (ParB and parC). These results expand the functions for oscillating cell cycle proteins to include also DNA segregation.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains.

E. coli strain MC1000 [Δ(ara-leu) Δlac rpsL150] (22) and KG22 (C600 lacIq lacZΔM15) were used in plasmid stability assays. M2141 (minB lac pro rpsL) is a minicell-producing strain (23). Resistance factor pB171 of enteropathogenic E. coli was obtained from T. Tobe (24), plasmid pMH82 was from A. K. Nielsen (25), and M. Mikkelsen constructed the pBR322-based expression-vector pMG25.

Plasmids Used and Constructed.

Plasmids used to assay for activity of par1, par2, or par12 were constructed by inserting the relevant PCR fragments of pB171 into the miniR1 lacZYA test vectors pRBJ200 (bla) or pMH82 (aphA). Plasmids derived from pMH82 carry the suffix K (for kanamycin resistance). The following oligonucleotides were used as PCR primers: pGE103, pB171–1 and pB171–9; pGE2 and pGE2K; pB171–4 and pB171–2; pGE201, pB171–4 and pB171–8; and pGE3, pB171–1, and pB171–2. Plasmid pGE202K carries an in-frame deletion of 71 codons within parA, created by digestion of pGE2K with EcoRI followed by religation. Plasmids pGE303 and pGE304 were constructed by PCR amplification of, respectively, parC1 and parC2 and cloning of the resulting fragments into the PstI-EcoRI sites (pGE303) or PstI-AatII sites (pGE304) of pBR322. The following primers were used for the PCR: pGE303, pB171–6, and pB171–9; and pGE304, pB171–10, and pB171–11. A parC1-containing PCR fragment was cloned between the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pMH82, resulting in pGE313. Plasmid pGE220 was constructed by PCR amplification of parA from pB171 by using primers pB171–14 and pB171–15. The PCR product was cloned into vector pEGFP (CLONTECH). Subsequently, plac∷parA∷gfp of pGE220 was inserted into the SwaI site of the following plasmids: pMH82 creating pGE230, pGE2K creating pGE233, pGE202K creating pGE236, and pGE313 creating pGE331. Plasmid pGE30K is pMH82 encoding LacZ′-Gfp. Plasmid pGE236G10V contains a single amino acid substitution within parA in parA∷gfp of pGE236. Plasmid pGE236G10V was constructed by replacement of the PsiI-AgeI fragment of parA∷gfp within pGE236 with a fragment containing the appropriate point mutation introduced by PCR, by using the following oligonucleotides as primers: pB171–26 and pB171–28. Plasmid pGE236K14Q was constructed in a similar way by using primers pB171–27 and pB171–28. Plasmid pGE223 encodes the His-tagged ParB protein constructed by using primers pB171–20 and pB171–21 inserted into plasmid pMG25. Plasmid pGE223 carries lacI and expresses His-tagged ParB on addition of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to growing cells. Sequences of primers used for PCR amplifications are available on request.

Microscopy.

Strain KG22 harboring relevant plasmid was grown overnight at 30°C in A + B minimal medium (26) plus 0.2% glucose/1 μg/ml of thiamine/0.05% (or 0.01%) casamino acids. Cultures were diluted 50-fold, grown to OD450 ≈ 0.03–0.04, and ParA-Gfp synthesis induced by IPTG. The generation time of the strains under these growth conditions was ≈75 min (or 130 min). Three to four hours after induction, a sample of cell culture was immobilized on microscope slides by using a thin film of 1% agarose. Living cells were observed as described previously (21).

Results

The Unusual Double par Operon of Plasmid pB171.

By database searching, we found that E. coli virulence plasmid pB171 contains two adjacent divergently oriented partitioning loci belonging to the two different classes of known par loci (see Introduction). We denote the two par loci of pB171 par1 and par2, respectively (Fig. 1). par1 encodes two putative proteins, ParM (323 amino acids) and ParR (130 amino acids), which are homologous to ParM (actin-like) and ParR of plasmid R1, respectively. Similarly, par2 encodes two proteins, ParA (214 amino acids) and ParB (91 amino acids). The putative ParA protein belongs to the ParA/SopA family, all of which contain the deviant Walker-type ATP-binding motifs (10, 27). ParA of pB171 belongs to the Ib subgroup of partitioning proteins also including ParA of pTAR from Agrobacterium tumefaciens and ParF from Salmonella newport plasmid TP228 (4, 11).

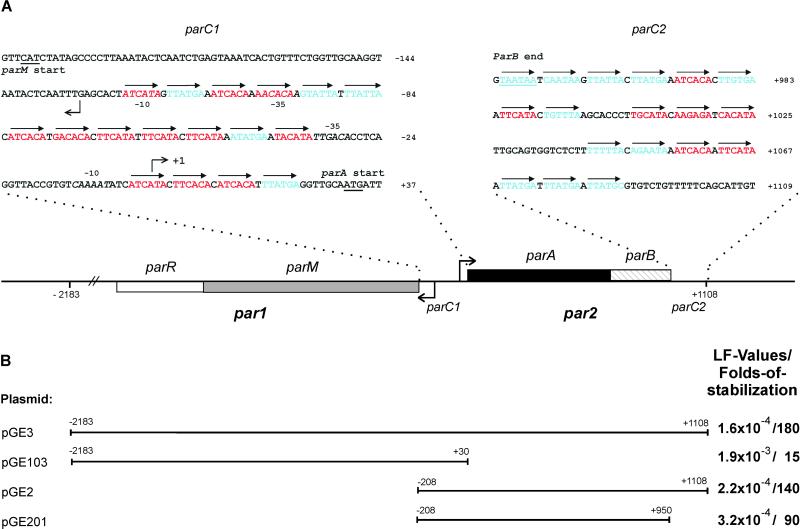

Figure 1.

Overview of the par12 locus of pB171 (A) and of pB171-derived DNA fragments used in plasmid-stability tests (B). A shows the genetic organization of par1 and par2, parC1 and parC2. The gene encoding the actin-like ParM protein is shown as a gray box, parR as an open box, parA encoding the Walker-type ATPase as a black box, and parB is hatched. The DNA sequences of parC1 and parC2 are shown in blowups; arrows indicate direct repeats. Red, class I repeats; blue, class II repeats. Broken arrows pointing left and right indicate the transcription start points for the par1 and par2 operons, respectively. Numbering of base pairs according to the transcription start point of par2 (denoted +1). B shows extensions of PCR-derived DNA fragments inserted into the R1 test vector pRBJ200 and their effect on plasmid stability given as LF values measured as described by Gerdes et al. (40). Folds of stabilization relative to pRBJ200 (LF = 10−2 per cell per generation) of the respective plasmids are also shown. LF values are averages of five independent experiments for all four plasmids. LF values and their standard deviations: pGE3: (1.6 ± 0.55) × 10−4; pGE103: (1.9 ± 0.58) × 10−3; pGE2: (2.2 ± 0.87) × 10−4; pGE201: (3.2 ± 0.84) × 10−4.

The promoter regions of par1 and par2 are adjacent and divergently oriented (Fig. 1A). Putative −10 and −35 promoter elements were readily recognized, and promoter activities were confirmed by primer extension analysis (not shown). The transcription start site of the par2 operon was mapped to the nucleotide located 31 bp upstream of the parA start codon. The major transcription start site of par1 was located on the opposite strand, 67 bp upstream of the start codon of parM. Thus, the promoters of par1 and par2 are separated by only 131 bp (Fig. 1A). We inspected the double promoter region for the presence of direct repeats. We found two clusters of 6-bp repeats, one consisting of 13 and another of 4 repeats, the latter being located between the par2 promoter and the start codon of parA (Fig. 1A). The repeats are in all cases separated by 1 bp. We denote the region containing the 17 repeats parC1. Likewise, the region downstream of parB contained 18 6-bp direct repeats organized into three clusters. Consequently, the 160-bp region downstream of parB was denoted parC2 (Fig. 1A). The repeats in parC1 and parC2 are related and could be divided into two subclasses (Fig. 1A, colored bases), from which two consensus sequences were derived. Thus, class I repeats have the consensus sequence [AT][TA]CA[TC]A and class II repeats TTAT[GT]A (alternative bases in brackets). The two classes of repeats are randomly distributed in parC1 and parC2 but with a slight preponderance of class I repeats in parC1 and class II repeats in parC2 (Fig. 1A).

par1 and par2 Both Contribute to Plasmid Segregation.

DNA fragments containing par1, par2, or par1 plus par2 were PCR amplified, cloned into a test vector, and sequenced (Fig. 1B). The test vector used, pRBJ200, was a par − R1 plasmid characterized by a loss rate of approximately 0.01 per cell per generation. The stability phenotypes conferred by the cloned DNA fragments were accurately measured in long-term plasmid-stability assays (80 generations) by using E. coli strain MC1000 as the host strain (Fig. 1B). par1 (in pGE103) stabilized the R1 vector 15-fold, implying that par1 by itself constitutes an active partitioning locus (the absolute loss frequencies are given in Fig. 1B). par2 (in pGE2) stabilized the R1 vector 140-fold, implying that par2 also constitutes an active partitioning locus. par1 plus par2 (in pGE3) stabilized the test vector 180-fold, consistent with the notion that both par loci simultaneously contribute to stabilize their replicon.

The par2 fragment contains both parC1 and parC2 (Fig. 1A). The downstream direct repeats (parC2) of pGE2 were deleted, resulting in pGE201. This plasmid yielded a 90-fold stabilization, implying that parC2 significantly contributes to the stabilizing effect of par2 (Fig. 1B).

parC1 Exerts Incompatibility Toward par1 and par2.

In all previous cases investigated, par-encoded direct repeats exert incompatibility. parC1 (−192 to +30) was cloned into a high-copy-number replicon (pBR322), and the resulting plasmid (pGE303) was introduced into strains MC1000/pGE103 (par1), MC1000/pGE2 (par2), MC1000/pGE3 (par12) and into MC1000 containing the proper control vector plasmid (pRBJ200). Table 1 shows that the presence of parC1 in high copy (pGE303) destabilized the par1 plasmid 5-fold, the par2 plasmid 130-fold, and the par12 plasmid 100-fold. Thus the central parC1 region destabilized plasmids carrying either par1 or par2, or both. parC1 destabilized par2 more than it destabilized par1.

Table 1.

Incompatibility exerted by parC1 and parC2

| Second plasmid | R1

test plasmid

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pRBJ200 (par−) | pGE103 (par1) | pGE2 (par2) | pGE3 (par12) | |

| pBR322 (vector) | 1.9 × 10−2 (≡1) | 7.7 × 10−4 (≡1) | 1.4 × 10−4 (≡1) | 8.9 × 10−5 (≡1) |

| pGE303 (parC1) | 2.1 × 10−2 (1) | 3.9 × 10−3 (5) | 1.9 × 10−2 (130) | 9.2 × 10−3 (100) |

| pGE304 (parC2) | 2.0 × 10−2 (1) | 7.5 × 10−4 (1) | 1.5 × 10−2 (110) | 6.7 × 10−4 (8) |

Numbers are LF values of the R1 test plasmids in the presence of the second plasmids pGE303 (parC1) or pGE304 (parC2) and are in all cases averages of three independent experiments. Numbers in parentheses are folds of destabilization (changes in LF values relative to the effect of pBR322) caused by the second plasmid (pBR322 derivatives). The effect of the pBR322 vector was set to 1. Cells of MC1000 were grown at 30°C in LB medium containing 10 μg/ml of tetracycline, thus selecting for the second plasmid (pBR322 derivatives). The plasmid vector used to construct the test plasmids was in all cases pRBJ200. Coordinates of the parC fragments are given in the text.

parC2 Exerts Incompatibility Toward par2 but Not Toward par1.

Plasmid pGE304, a pBR322 derivative carrying parC2 (+920 to +1108), was analyzed in a similar way. Interestingly, pGE304 destabilized the par2 plasmid (pGE2) 110-fold and was thus in this respect almost as efficient as parC1 (Table 1). However, the parC2-carrying plasmid did not destabilize the par1-carrying plasmid pGE103 at all. The par12-carrying plasmid pGE3 was also destabilized significantly (8-fold) by parC2 (Table 1). This result suggests that parC2 is a component of par2 but not of par1.

ParA-Gfp Is Functional.

Introduction of an in-frame deletion of 71 codons in parA inactivated par2, showing that parA is essential (pGE202K in Table 2). The parA gene was then fused to a bright variant (mut1) of gfp. A DNA fragment encoding plac∷parA∷gfp was inserted into the R1 plasmid carrying the deletion in parA, resulting in pGE236 (par2 ΔparA plac∷parA∷gfp). The stability of pGE236 was measured in KG22 (lacIq) without the addition of IPTG. Importantly, the insertion of the plac∷parA∷gfp fragment yielded a 75-fold increase in stability, indicating that ParA-Gfp is at least partially functional [for absolute loss frequencies per cell per generation (LF) values, compare pGE236 and pGE202K in Table 2]. Higher expression levels of ParA-Gfp did not increase stability of pGE236 (not shown).

Table 2.

Correlation of plasmid stabilization and ParA-Gfp oscillation

| Plasmid* | par2 components† | LF values‡ | Folds of stabilization | Oscillation of ParA-Gfp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pMH82 | None | 2.0 × 10−2 | 1.0 | No ParA-Gfp |

| pGE2K | parC1 parA parB parC2 | 1.3 × 10−4 | 150 | No ParA-Gfp |

| pGE202K | parC1 ΔparA parB parC2 | 2.0 × 10−2 | 1.0 | No ParA-Gfp |

| pGE236 | parC1 ΔparA parB parC2 parA∷gfp | 2.7 × 10−4 | 75 | + |

| pGE236G10V | parC1 ΔparA parB parC2 parA(G10V)∷gfp | 2.0 × 10−2 | 1.0 | − |

| pGE236K14Q | parC1 ΔparA parB parC2 parA(K14Q)∷gfp | 3.2 × 10−2 | 0.6 | − |

| pGE233 | parC1 parA parB parC2 parA∷gfp | 5.0 × 10−4 | 40 | + |

| pGE230 | parA∷gfp | 1.7 × 10−2 | 1.2 | − |

All plasmids were derived from pMH82, a par− R1 test vector.

Δ indicates a 213-bp in-frame deletion in parA.

LF values are defined in the legend to Fig. 1. Plasmid-containing cells of strain KG22 (lacI

) were grown in LB medium at 30°C without IPTG. Culture dilutions were plated on LA plates containing X-gal (40 μg/ml) to determine the frequency of plasmid-containing cells. Numbers are in all cases averages of at least three independent experiments.

The plac∷parA∷gfp fragment was also inserted into an R1 plasmid encoding the entire par2 locus (pGE2K), resulting in pGE233 (par2 plac∷parA∷gfp). Plasmid pGE233 was less stable than its parent plasmid pGE2K (par2), showing that the presence of parA∷gfp interfered with par2 activity (Table 2). However, pGE233 (par2 plac∷parA∷gfp) was 40-fold more stable than pGE230 carrying plac∷parA∷gfp without par2.

ParA-Gfp Oscillates.

We examined the subcellular localization of ParA-Gfp in living cells by using fluorescence microscopy. In a little more than half of fluorescent KG22 cells harboring either pGE233 (par2 plac∷parA∷gfp) or pGE236 (par2 ΔparA plac∷parA∷gfp), the signal was positioned asymmetrically in one-half of the cell only, appearing either as a distinct focus or as an elongated drop-shaped structure (Fig. 2A). The rest of the fluorescent cells showed a weaker and more diffuse fluorescence pattern. Thirty percent of all cells harboring pGE233 or pGE236 showed no fluorescence. Interestingly, time-lapse experiments revealed that ParA-Gfp oscillated from one end of the cell to the other on a time scale of minutes (compare Fig. 2A Left and Right).

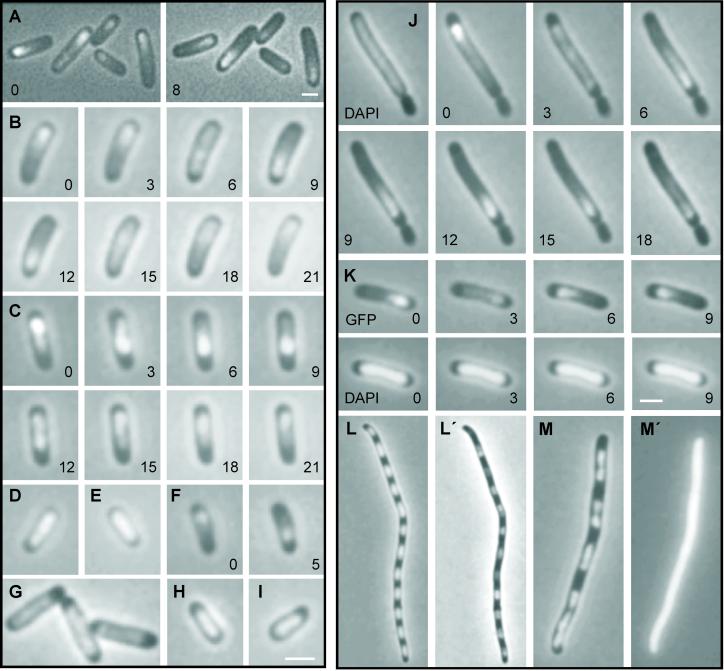

Figure 2.

Dynamic properties of functional ParA-Gfp in live cells. Combined phase contrast and fluorescent microscopy of ParA-Gfp-containing KG22 cells grown as described in Materials and Methods in the presence of 100 μM IPTG except in E and F (10 μM IPTG). Numbers are minutes in time-lapse experiments. (A) ParA-Gfp from pGE233 (par2 plac∷parA∷gfp). Left and Right show the same cells; (B) a complete cycle of ParA-Gfp from pGE233 (par2 plac∷parA∷gfp); (C) a complete oscillation cycle of ParA-Gfp from pGE236 (par2 ΔparA plac∷parA∷gfp); (D) ParA-Gfp from pGE331 (parC1 plac∷parA∷gfp); (E) ParA-Gfp from pGE230 (plac∷parA∷gfp) in the presence of pGE223 (plac∷his6∷parB); (F) ParA-Gfp from pGE331 (parC1 plac∷parA∷gfp) in the presence of pGE223 (plac∷his6∷parB); (G) ParA-Gfp from pGE230 (plac∷parA∷gfp); (H and I) ParA-Gfp from pGE236G10V (par2 ΔparA plac∷parA(G10V)∷gfp) and pGE236K14Q (par2 ΔparA plac∷parA(K14Q)∷gfp), respectively; (J) ParA-Gfp from pGE236 (par2 ΔparA plac∷parA∷gfp) in the minicell-producing strain M2141. DAPI staining was also included (Left). (K) DAPI and Gfp signals from cells of KG22 carrying pGE236 (par2 ΔparA plac∷parA∷gfp); (L and M) DAPI staining of KG22/pGE230 (plac∷parA∷gfp) and KG22/pGE30K (plac∷lacZ′∷gfp) cells treated with cephalexin (10 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (300 μg/ml). (L′ and M′) Gfp signal from the same cells. Omission of chloramphenicol yielded essentially similar although less clear patterns of nucleoid distribution. (Bar = 2 μm.)

Next, we followed individual cells of KG22 carrying pGE233 (par2 plac∷parA∷gfp) in time-lapse experiments. Fig. 2B shows a typical sequence of events starting with a ParA-Gfp focus located near one end of a cell. During the following 6–10 min, the focus disintegrated, and the fluorescent signal moved to the opposite end where a new bright focus was assembled. The foci very rarely reached the ultimate cell poles. Oscillation time depended on the length of the cell, with the oscillation time being longest in the longer cells. This cell-length dependency was especially prominent in the long cells of the minicell-producing strain (Fig. 2J; see below). In some cells, the focus repeated the oscillation cycle almost immediately, whereas in others it seemed to be at rest for several minutes before it resumed moving. In a minor portion of the cells, the newly formed foci were stationary, at least for as long as fading of the fluorescent signal allowed additional images to be acquired.

We also determined oscillation of ParA-Gfp in a strain lacking any wild-type ParA protein. Fig. 2C shows that ParA-Gfp from pGE236 (par2 ΔparA plac∷parA∷gfp) oscillated. Thus, ParA-Gfp exhibited dynamic behavior even without the presence of native ParA. The oscillation frequencies were similar in the two different genetic backgrounds (Fig. 2 B and C).

ParA-Gfp Oscillation Depends on ParB and parC.

To determine whether oscillation depended on other genetic determinants of the par2 locus, we examined ParA-Gfp in other R1 derivatives. First, ParA-Gfp was examined in cells harboring pGE230, a R1 derivative containing plac∷parA∷gfp but neither parB nor parC (Table 2). In these cells, ParA-Gfp fluorescence did not oscillate and was evenly distributed (Fig. 2G). Thus, formation and oscillation of ParA-Gfp foci required the presence of ParB and/or parC.

To generate cells producing ParA-Gfp and ParB, plasmid pGE223 (plac∷his6∷parB), which expresses a functional His-tagged version of ParB protein, was introduced into KG22 carrying pGE230 (plac∷parA∷gfp). ParA-Gfp produced by the resulting strain, KG22/pGE230 (plac∷parA∷gfp)/pGE223 (plac∷his6∷parB), did not oscillate (Fig. 2E). Thus, ParA-Gfp did not oscillate in the presence of ParB without parC.

Next, cells expressing ParA-Gfp in the presence of parC1, but without parB, were examined. ParA-Gfp produced by KG22/pGE331 (parC1 plac∷parA∷gfp) did not oscillate (Fig. 2D).

Finally, plasmid pGE223 (plac∷his6∷parB) was introduced into cells carrying pGE331 (parC1 plac∷parA∷gfp). In this case, oscillation was regained (Fig. 2F). Together, these results show that ParA-Gfp oscillation requires the presence of ParB and at least parC1. Moreover, ParA-Gfp oscillated even though ParB was donated in trans.

Oscillation of ParA-Gfp Does Not Depend on minCDE.

ParA-Gfp in the minicell-producing strain M2141 (minB) carrying pGE236 (par2 ΔparA plac∷parA∷gfp) oscillated (Fig. 2J). Thus, ParA-Gfp oscillation was independent of the minCDE system. Many cells of the minicell-producing strain appeared elongated. In such cells, ParA-Gfp cycling time was considerably increased, typically in the order of 30 min at the conditions used here (Fig. 2J).

Walker A Box Mutations in ParA-Gfp Simultaneously Abolish Oscillation and Plasmid Stabilization.

Single amino acid changes were introduced into the conserved ATP-binding domain (Walker A box motif) of ParA-Gfp. Glycine at position 10 was changed to valine and lysine at position 14 to glutamine. Lysine 14 (or its equivalent) is nearly invariable in all Walker A boxes (10, 27) and interacts with the α- and β-phosphates of the bound nucleotide (28, 29). Mutations in the conserved lysine typically disrupt nucleotide binding (30). Microscopy revealed that cells of KG22 carrying plasmids pGE236G10V [par2 ΔparA plac∷parA(G10V)∷gfp] or pGE236K14Q no longer showed asymmetric distribution of the ParA-Gfp fusion proteins, and the proteins did not oscillate (Fig. 2 H and I). Plasmid stability assays revealed that pGE236G10V and pGE236K14Q were unstably inherited (Table 2). Thus, mutational change of conserved amino acids within the Walker A box of ParA simultaneously abolished the oscillating behavior of the fusion protein and its ability to mediate plasmid stabilization.

ParA-Gfp Colocalizes with Nucleoids.

During oscillation, the ParA-Gfp signal rarely reached the ultimate cell poles and was often asymmetrically distributed (Fig. 2 A and C). 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining of cells harboring pGE236 (par2 ΔparA plac∷parA∷gfp) indicated that the Gfp signal coincided with nucleoid regions (Fig. 2K). The DAPI-stained nucleoid DNA appeared stationary, showing that ParA-Gfp, not the DNA, moved. To substantiate the presumed nucleoid localization of ParA-Gfp, we also investigated filamentous multinucleate cells containing pGE230 (plac∷parA:.gfp) obtained by treatment with cephalexin and chloramphenicol (the latter condenses the nucleoids). In such cells, DAPI staining showed that nucleoids were evenly distributed along the cell filaments (Fig. 2L). The ParA-Gfp signal exhibited a very similar distribution (Fig. 2L′), indicating that ParA-Gfp preferentially locates at nucleoid regions. This subcellular compartmentalization required neither ParB nor parC DNA. We did not observe oscillation in filaments, even in the presence of ParB and parC (not shown). By contrast, LacZ′-Gfp was evenly distributed within cells (Fig. 2 M and M′).

Discussion

Two par Loci.

We show here that the virulence plasmid pB171 encodes two adjacent active partitioning loci, denoted par1 and par2 (Fig. 1A). Each can mediate efficient plasmid segregation alone, but optimal segregation requires the presence of both loci. Incompatibility data suggest that the two loci share a common cis-acting central site, parC1.

Separately, par1 and par2 yielded 15- and 140-fold of stabilization, respectively (Fig. 1B). Together, they yielded 180-fold of stabilization. Thus, the combined effect of par1 and par2 was less than expected from stochastically independent mechanisms. This is not surprising, because the par systems obviously cannot solve plasmid instability problems caused by replicon catenation, failure in plasmid replication, etc. They do, however, apparently back each other up with respect to defects in proper segregation.

The genetic organization and components of the isolated par2 locus are in most respects typical of Type Ib loci (4). First, parA encodes a putative ATPase that contains the deviant Walker-type ATPase motif (10). As in other Type Ib loci, ParA of par2 is relatively small (214 amino acids) and does not contain an N-terminal DNA-binding domain (4, 11). By analogy with par of pTAR (31), another Type Ib locus, ParB of par2, would bind to parC1. Furthermore, our stability and incompatibility data show that parC2 acts as a second cis-acting site of par2 (Fig. 1B and Table 1). The relatedness of the repeats in parC1 and parC2 suggests that ParB likely also binds to parC2.

ParA Undergoes Multiple Oscillations Within the Nucleoid Between Each Round of Cell Division.

We find that Gfp-tagged ParA colocalizes with the nucleoid and oscillates from one end of the cell to the other several times per division cycle. Because the nucleoid itself does not appear to oscillate similarly, we infer that the protein is repositioning itself within the chromosomal mass during these oscillations. Oscillation occurs with a periodicity of about 20 min over doubling times of 75–130 min, and shorter cells in the population exhibited more rapid cycling than longer cells. The oscillating behavior of ParA was abolished in the absence of either ParB or parC and by a mutation in the Walker A box ATP interaction domain. Mediation of plasmid segregation is the raison d'être of the par2 locus, and all three of these genetic perturbations also eliminate plasmid segregation. Thus, it seems likely that the cyclic behavior of ParA is a fundamental factor in the mechanism of plasmid DNA segregation during cell division.

However, exactly how oscillation of ParA would contribute to segregation is unclear. One question pertains to the step(s) of segregation at which oscillation would act. Perhaps oscillation is required for normal positioning of plasmid genomes at proper subcellular positions, e.g., to locate par2-containing plasmids at midcell and/or to relocalize the plasmid from mid- to quarter-cell positions or to nucleoid borders. Even more intriguing questions are: (i) How does oscillation occur at all, and (ii) exactly how, mechanistically, could cyclic positional alternation of a protein within the nucleoid have an effect on plasmid segregation. A possible clue is provided by the fact that ParA is known to interact with the ParB–parC complex. Perhaps this interaction either triggers and/or is the target of oscillation.

Three Related Cell Cycle Proteins All Exhibit Intracellular Oscillation.

Oscillation of proteins from end to end within a cell has been reported previously in two other prokaryotic systems, both of which have been implicated in chromosome segregation.

Soj of Bacillus subtilis.

Soj is a ParA homologue encoded by the B. subtilis chromosome (12). The soj gene is located upstream of and adjacent to spoOJ that encodes the B. subtilis ParB homologue. Soj oscillates from pole to pole or within nucleoid regions (32, 33), depending on the presence of Spo0J. Apparently, Spo0J, but not Soj, is required for chromosome partitioning. However Soj and Spo0J were both required for parS-dependent plasmid stabilization in B. subtilis. Furthermore, when cloned into a miniF replicon, the soj spoOJ parS locus stabilized the plasmid significantly in E. coli (12). The function of Soj oscillation for the B. subtilis chromosome is not known, but it has been suggested to be important for developmental regulation of B. subtilis promoters (33) or to couple developmental transcription to cell cycle progression (32). Given the results obtained here, Soj oscillation may also be involved in plasmid segregation in B. subtilis and E. coli.

MinCDE of E.

coli.

In many bacteria, specification of midcell septum formation is mediated by the MinCDE system. MinC is a cell division inhibitor that, in complex with MinD, counteracts Z-ring assembly (or function) by direct contact with FtsZ (34). MinE somehow limits MinCD inhibition to the cell poles and thereby allows for Z-ring assembly at midcell (35). MinE assembles as a ring-formed structure at midcell (36). MinD cell cycle proteins also belong to the superfamily of ATPases with the deviant Walker box motif (10, 37), and MinD of E. coli has also been shown to oscillate. Recent experiments have shown that the E-ring oscillates in concert with MinD (38, 39). The cyclic behavior of MinD and MinE suggests that the proteins confer topological specificity by keeping the concentration of MinCD complex at midcell sufficiently low as to allow Z-ring assembly.

Relationships.

ParA-Gfp oscillates normally in a minB strain (above), indicating that oscillation of ParA occurs independently of a functional minCDE system. Also, there are certain differences between the MinD/E and ParA/B systems. MinD/E oscillation is more rapid than that observed for ParA and Soj (once per 20 sec rather than once per several minutes); furthermore, MinD/E are localized to the cell poles or midcell structures rather than within the nucleoid. Nonetheless, there are similarities that could point to related underlying mechanisms in all three systems. For example, in all three systems, oscillation involves a ternary complex involving the oscillating protein (ParA/Soj/MinD), a second system-encoded protein (ParB/SpoOJ/MinE), and a “structural” component (parC1 or parS DNA sites or the FtsZ ring). In this regard, it would be interesting to know whether ParB oscillates. Also, cycling time varied inversely with cell size for MinD of E. coli (38) as well as for ParA (above).

It is also interesting that three cell cycle proteins, MinD, Soj, and ParA, all belonging to the superfamily of ATPases with the deviant Walker-type ATPase motif, exhibit multiple oscillations during the cell division cycle. This relationship allows for the speculation that other such proteins may exert their function through a dynamic subcellular localization pattern.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Kleckner for extensive revision of the manuscript, a referee for the suggestion that ParA-Gfp associates with nucleoids, J. Møller-Jensen for the introduction to fluorescence microscopy, T. Tobe (University of Tokyo) for the donation of pB171, and O. G. Issinger for the use of a Leica microscope. The Danish Biotechnology Program supported this work.

Abbreviations

- LF

loss frequencies per cell per generation

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- IPTG

isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside

- Gfp

green fluorescent protein

References

- 1.Hiraga S. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:21–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon G S, Wright A. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:681–708. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Møller-Jensen J, Jensen R B, Gerdes K. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:313–320. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerdes K, Møller-Jensen J, Bugge J R. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:455–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe E, Wachi M, Yamasaki M, Nagai K. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;234:346–352. doi: 10.1007/BF00538693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis M A, Martin K A, Austin S J. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1141–1147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davey M J, Funnell B E. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29908–29913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davey M J, Funnell B E. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15286–15292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen R B, Gerdes K. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:505–513. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koonin E V. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:1165–1174. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes F. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:528–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaichi Y, Niki H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14656–14661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon G S, Sitnikov D, Webb C D, Teleman A, Straight A, Losick R, Murray A W, Wright A. Cell. 1997;90:1113–1121. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80377-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niki H, Hiraga S. Cell. 1997;90:951–957. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erdmann N, Petroff T, Funnell B E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14905–14910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bork P, Sander C, Valencia A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7290–7294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dam M, Gerdes K. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:1289–1298. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen R B, Dam M, Gerdes K. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:1299–1309. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breuner A, Jensen R B, Dam M, Pedersen S, Gerdes K. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:581–592. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5351063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen R B, Lurz R, Gerdes K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8550–8555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen R B, Gerdes K. EMBO J. 1999;18:4076–4084. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casadaban M, Cohen S N. J Mol Biol. 1980;138:179–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stougaard P, Molin S, Nordstrom K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6008–6012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tobe T, Hayashi T, Han C G, Schoolnik G K, Ohtsubo E, Sasakawa C. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5455–5462. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5455-5462.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen A K, Thorsted P, Thisted T, Wagner E G, Gerdes K. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1961–1973. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark D J, Maaloe O. J Mol Biol. 1967;23:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker J E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pai E F, Kabsch W, Krengel U, Holmes K C, John J, Wittinghofer A. Nature (London) 1989;341:209–214. doi: 10.1038/341209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Story R M, Steitz T A. Nature (London) 1992;355:374–376. doi: 10.1038/355374a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamauchi M, Baker T A. EMBO J. 1998;17:5509–5518. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalnin K, Stegalkina S, Yarmolinsky M. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1889–1894. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1889-1894.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marston A L, Errington J. Mol Cell. 1999;4:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80378-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quisel J D, Lin D C, Grossman A D. Mol Cell. 1999;4:665–672. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu Z, Lutkenhaus J. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3965–3971. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.14.3965-3971.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Boer P A, Crossley R E, Rothfield L I. Cell. 1989;56:641–649. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raskin D M, de Boer P A. Cell. 1997;91:685–694. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayashi I, Oyama T, Morikawa K. EMBO J. 2001;20:1819–1828. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu X, Shih Y L, Zhang Y, Rothfield L I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:980–985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031549298. . (First Published January 23, 2001; 10.1073/pnas.031549298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hale C A, Meinhardt H, de Boer P A. EMBO J. 2001;20:1563–1572. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerdes K, Larsen J E, Molin S. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:292–298. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.292-298.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]