Abstract

Therapy resistance is a significant challenge for prostate cancer treatment in clinic. Although targeted therapies such as androgen deprivation and androgen receptor (AR) inhibition are effective initially, tumor cells eventually evade these strategies through multiple mechanisms. Lineage reprogramming in response to hormone therapy represents a key mechanism that is increasingly observed. The studies in this area have revealed specific combinations of alterations present in adenocarcinomas that provide cells with the ability to transdifferentiate and perpetuate AR-independent tumor growth after androgen-based therapies. Interestingly, several master regulators have been identified that drive plasticity, some of which also play key roles during development and differentiation of the cell lineages in the normal prostate. Thus, further study of each AR-independent tumor type and understanding underlying mechanisms are warranted to develop combinational therapies that combat lineage plasticity in prostate cancer.

Keywords: lineage plasticity, neuroendocrine, prostate cancer, therapy resistance, transdifferentiation

INTRODUCTION TO STANDARD THERAPIES AND RESISTANCE

As the number one diagnosed cancer and second leading cause of cancer death in American men,1 prostate cancer (PCa) and effective therapies remain pressing clinical issues. Although prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening has led to an overall decrease in the number of metastatic disease diagnoses, improved screening has also increased clinically indolent cancer diagnoses.1,2 Earlier detection of potentially indolent disease can lead to unnecessary treatment and represents a significant economic burden.3,4 This effect is magnified by a lack of improved survival for either indolent or metastatic disease with PSA screening,2,3,4,5 and accompanied by unavoidable biochemical recurrence and disease progression.6

For earlier-stage prostate tumors, the standard of care can include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, or radiation therapies.7 Further treatment for recurrence or disease progression can include continuous or intermittent hormonal therapies.7 The androgen receptor (AR) is a frequent and well-established target of hormonal therapies such as androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).8,9 Abiraterone, a potent cytochrome P450 17A1 (CYP17A1 or steroid 17α-monooxygenase) inhibitor,10 and enzalutamide, a small molecule AR antagonist,11 both lead to a significant reduction in AR activity,9,12,13 but are eventually overcome in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Next-generation AR-targeted therapies under development such as the CYP17 inhibitor Seviteronel (VT-464)14 and the AR antagonists Apalutamide (ARN-509),15,16 Darolutamide (ODM-201),17,18 and EPI-001,19 may further prolong CRPC recurrence,20 but the current standard treatment options for recurrent disease are limited to chemotherapy,21,22 immunotherapy,7,23 and radiopharmaceutical therapy.24,25 These relatively uniform androgen ablation and chemotherapy treatment options do not fully account for the heterogeneous genetic background between individual patient tumors at the time of initial therapy, or variable molecular changes in response to therapy. As such, the current treatment options and unavoidable therapy resistance represent significant barriers to improving patient outcomes.

Several well-established mechanisms of resistance to AR-targeted therapies which have been characterized can be divided into three main categories: restored AR signaling, bypassed AR signaling, and AR signaling independence.6,26 AR pathway signaling can be restored by AR mutation or truncation that most commonly alters the ligand binding domain (LBD).27,28,29,30,31,32,33 These mutations allow for receptor promiscuity and activation by alternative steroid hormones or AR antagonists such as enzalutamide.33,34 Truncated mutants, as well as splice variants, that lack the LBD are constitutively active and resistant to many AR-targeted therapies.35,36,37,38 In addition, steroid hormone synthesis genes are often upregulated after chemical castration to restore AR signaling.20,39 AR amplification is also observed after AR-targeted therapy;40,41,42 however, increased AR levels that contribute to disease progression are also observed independently of gene amplification.43 Bypass of AR signaling is thought to occur through other steroid hormone receptors,6 such as glucocorticoid receptor (GR), which is upregulated in prostate tumors posttherapy.44,45,46 GR shares similar protein structure, DNA binding motifs, and transcriptional targets with AR, suggesting that it may compensate for AR and contribute to castration resistance.26,44,47,48 Finally, a subset of CRPC appear to be AR-independent, with minimal to no AR expression.49,50,51 These tumors may display neuroendocrine (NE) phenotypes, but are heterogeneous and remain to be systematically characterized.52 New insights into AR-independent CRPC suggest that cell lineage plasticity is a driving factor in loss of AR and resistance to AR-targeted therapies,53,54,55 which is the focus of this review.

PROSTATE CELL LINEAGES DURING DEVELOPMENT AND IN THE ADULT

An understanding of normal prostate development and well-regulated maintenance of tissue identity is useful in order to understand the changes that occur during tumorigenesis and gain of therapy resistance. Although the mature mouse prostate has distinct lobes in contrast to the lobe-less adult human prostate, many prostate-centric studies are performed in mice due to the developmental and tumorigenic similarities between the human and mouse prostate.56 Notably, human and rodent prostate tissues can be recombined to generate functional prostate tissues, arguing for the applicability of mouse models to study prostate development and tumorigenesis.56,57

During normal prostate development in the mouse, several key factors regulate differentiation of the urogenital sinus (UGS), including androgens and the androgen-responsive transcription factor NK3 homeobox 1 (NKX3.1).58,59 Most importantly, secreted androgens activate the mouse AR protein that is initially only expressed in the stromal cells of the urogenital sinus mesenchyme (UGM) and is required for paracrine signaling that initiates organ differentiation.60,61,62,63 Soon after organ differentiation, morphological prostate development occurs through epithelial budding and proliferation that leads to bud elongation, lumen formation, branching morphogenesis, differentiation, and maturation.58,59,64 In particular, epithelial AR expression does not occur until after budding and branching morphogenesis,65,66,67,68 while initial expression of the NKX3.1 transcription factor occurs as early as 15.5 days post coitum (dpc) in the urogenital sinus epithelium (UGE) and is important for prostatic bud formation and ductal morphology.69 Subsequent androgen-regulated expression of NKX3.1 in the UGE and in the luminal epithelial cells of the differentiated prostate is maintained by epithelial AR expression.64,69

Further morphological development requires paracrine signaling from stromal to epithelial cells that includes many pathways and regulatory factors such as transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), sonic hedgehog (SHH), wingless and int1 (WNT), NOTCH, homeobox genes, forkhead genes, and sex-determining region Y-box 9 (SOX9), as reviewed previously.58,64 Loss of these pathways during prostate development generally contributes to organ defects, and dysregulation of these pathways in the fully differentiated prostate is also implicated in hyperplasia and cancer.70

Fully developed prostate tissue in both human and mouse can be divided into stromal and epithelial components, where the epithelial component consists of CK5/CK14/CD44/p63-positive basal cells, CK8/CK18/CD57/NKX3.1/AR-positive luminal cells, and rare NE cells that express markers such as synaptophysin (SYP), chromogranin A (CGA), and neuron-specific enolase (NSE).50,51,56,71 In the mature prostate, androgen-dependent luminal cells line the lumen of mature prostatic ducts and produce prostatic secretory proteins, while AR-negative basal cells form a layer between the luminal cells and the basement membrane.56 AR-negative NE cells dispersed throughout the basal layer are important for signaling and regulation of growth, differentiation, and function of the prostate.51,56,72 Further differentiation of the UGE component during development into these cell types is tightly regulated by the transcription factor p63 in basal progenitor cells.73,74 p63-positive basal progenitor cells undergo either symmetric divisions to generate two progeny basal cells, or asymmetric divisions to generate one basal and one luminal cell,75 a process dependent on mitotic spindle orientation regulated by GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3).76 This plasticity results in double-positive intermediates, a fourth epithelial cell type found in the basal compartment of the developed prostate, which express both luminal and basal markers and have yet to fully differentiate into the luminal cell fate.76,77,78,79 In contrast, luminal epithelial cells do not exhibit the same plasticity but instead divide symmetrically to generate two progeny luminal cells.75

Interestingly, the plasticity exhibited by basal progenitor cells is thought to contribute to prostate regrowth and repair, as well as tumorigenesis.74,75 Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) is a well-established tumor suppressor gene in PCa, deletion of which in mice recapitulates human PCa progression from prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) to invasive adenocarcinoma.80 Pten loss and subsequent transformation of luminal epithelial cells are sufficient for tumorigenesis in mice, as is Pten loss in basal epithelial cells.75,81,82 However, transformed basal cells maintain the ability to divide asymmetrically and generate transformed luminal progeny that express the stem cell and NE factor SOX2 and also drive tumorigenesis in mice.74,75,81 This ability to generate stem-like, transformed progenitor cells in the prostate implies that established prostate tumors may also rely on cell lineage dysregulation as a means of therapy resistance.

TRANSDIFFERENTIATION AS A MECHANISM OF THERAPY RESISTANCE

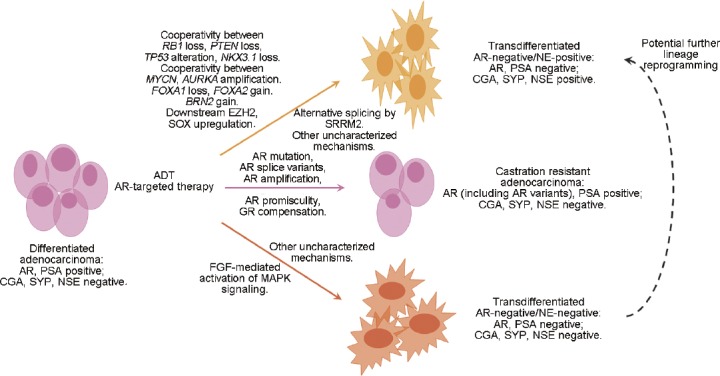

While the emergence of different cancer cell populations post-therapy is not a novel concept, there are multiple proposed mechanisms to explain this plasticity phenomenon. Due to the reliance on ADT and AR targeting in PCa, AR-negative cells such as NE cells are frequently implicated in PCa therapy resistance. Therapies that specifically target a subpopulation of tumor cells, such as ADT that targets AR-positive PCa cells, may generate selective pressure for existing AR-negative NE cells to perpetuate AR-independent tumor growth. However, the majority of evidence suggests a more likely second mechanism of clonal divergence and transdifferentiation from adenocarcinoma (Figure 1). In this case, adenocarcinoma cells can proliferate and generate progenitor adenocarcinoma cells, but also transdifferentiate into AR-independent NE cells, specifically after ADT or AR-targeted therapy.49,52 Here, transdifferentiation is defined as the switch from one differentiated cell type to another, which may progress through an intermediate cell type that is not pluripotent and involves a discrete change in the gene expression program of the cell.83 In support of this mechanism, similar patterns of genetic alterations are observed between adenocarcinoma and NE foci in mixed tumors, including transmembrane protease, serine 2-ETS-related gene (TMPRSS2-ERG) fusion,84,85,86,87 tumor protein p53 (TP53) mutation,88 and neuroblastoma-derived v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral related oncogene (MYCN) and aurora kinase A (AURKA) gene amplification.84 Importantly, castration of a patient-derived adenocarcinoma xenograft has been shown to develop a small-cell NE phenotype and maintains similar genetic alterations as the parental lesion.89 A similar phenomenon has been observed in the CWR22,90 PC-295 and PC-130,91 and MDA PCa 14492 xenograft models. In-depth analysis of serial tumor samples from 81 patients with clinically and histologically classified CRPC-adenocarcinoma or CRPC-NE tumors also confirmed a pattern of alterations in serial samples to support a clonal divergent mechanism.49

Figure 1.

Model of therapy-induced prostate cancer cell lineage plasticity. Treatment of adenocarcinoma with ADT or AR-targeted therapy ultimately leads to therapy resistance through multiple mechanisms. Notably, adenocarcinoma cells can transdifferentiate into AR-negative/NE-negative or AR-negative/NE-positive tumor types or can rely on AR bypass signaling and AR mutation to develop castration resistant adenocarcinoma. ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; AR: androgen receptor; AURKA: aurora kinase A; BRN2: brain-specific homeobox/POU domain protein 2; CGA: chromogranin A; EZH2: enhancer of zeste homolog 2; FGF: fibroblast growth factor; FOXA1: forkhead box protein A1; FOXA2: forkhead box protein A2; GR: glucocorticoid receptor; NE: neuroendocrine; NKX3.1: NK3 homeobox 1; NSE: neuron-specific enolase; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinases; MYCN: neuroblastoma-derived v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral related oncogene; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; PTEN: phosphatase and tensin homolog; RB1: retinoblastoma 1; SOX: sex-determining region Y-box; SRRM2: serine/arginine repetitive matrix 2; SYP: synaptophysin; TP53: tumor protein p53.

Another class of AR-independent tumor posttherapy that also lacks NE differentiation is increasingly recognized in clinical tumor samples.93,94 A study comparing two metastatic CRPC cohorts from 1998 to 2011 and from 2012 to 2016 highlights the existence of three unique tumor types: AR-positive/NE-negative, AR-negative/NE-positive, and less well-characterized AR-negative/NE-negative (or called double-negative) tumors.95 These double-negative tumors possess heterogeneous mutational profiles and rely on increased FGF and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling for tumor growth.95 Notably, the AR-negative/NE-negative and AR-negative/NE-positive tumors have significantly increased in prevalence since 2012 and the widespread use of the second-generation AR-targeted therapies, suggesting that these tumors may also transdifferentiate in response to AR-targeting. Specifically comparing the cohort of patients with metastatic CRPC between 2012–2016 to the cohort from 1998–2011, the percentage of patients with AR-positive/NE-negative tumors has decreased by 25.1% to overall 63.3%, while the percentage of patients with AR-negative/NE-negative and AR-negative/NE-positive tumors has increased by 17.9% to overall 23.3% and 7.0% to overall 13.3%, respectively.95 These data argue that lineage reprogramming represents a significantly growing population of therapy-resistant tumors in the era of AR-targeted therapies. Further study of the double-negative phenotype is warranted to determine if these tumors represent an intermediate transitional state between AR-positive/NE-negative and AR-negative/NE-positive tumors or a third fully differentiated tumor phenotype with a distinct molecular profile and clinical outcome.

CHARACTERISTICS OF AR-INDEPENDENT NEUROENDOCRINE PROSTATE CANCERS

The precise definition and characteristics of AR-negative/independent or neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC) are actively being refined to reflect aspects of both morphological characterization and clinical behavior.50 The Prostate Cancer Foundation Working Committee on NEPC has suggested that AR-negative/independent PCa and tumors with NE features should be referred to as AR-negative96 and has also released guidelines for tumor subtype classifications.72 Multiple tumor types fit this description, with subtle differences in morphology and clinical outcome. The proposed classifications for NEPC include six categories: (1) usual prostate adenocarcinoma with NE differentiation; (2) adenocarcinoma with Paneth cell NE differentiation; (3) carcinoid tumor; (4) small-cell carcinoma; (5) large-cell NE carcinoma; and (6) mixed (small or large cell) NE carcinoma–acinar adenocarcinoma.72

The morphological and clinical characteristics of each category have been outlined in detail previously.72 Briefly, small-cell carcinoma is often positive for at least one NE marker such as SYP or CGA, negative for AR and PSA, and exhibits a sheet-like growth pattern with notably small tumor cells and mitotic figures.51,97 Small-cell carcinomas often arise after hormone therapies98,99 and exhibit rapid growth, poor prognosis, and therapy resistance.100 Large-cell NE carcinomas, although exceedingly rare, display similar poor prognosis and often arise after ADT, but are characterized by notably large tumor cells with abundant cytoplasm and prominent nuclei.101 In contrast to large- and small-cell carcinomas, rare carcinoid tumors are well-differentiated NE tumors without any components or markers of adenocarcinoma, and a relatively favorable prognosis.50 It should be noted that only five verified cases of carcinoid tumors are found in the literature.72 Adenocarcinoma with Paneth cell-like NE differentiation, recognized by foci of eosinophilic NE cells,102 also has a favorable prognosis.72 Usual prostate adenocarcinoma with NE differentiation represents tumors with typical adenocarcinoma morphology and markers that also express NE markers detected by immunohistochemistry, but that have no distinguishable difference in outcome.72,103 In stark contrast, mixed NE carcinoma–acinar adenocarcinoma, with components of typical adenocarcinoma and distinct foci of NE carcinoma, is highly aggressive.72,94 Interestingly, the degree of NE differentiation in these tumors increases in response to ADT.104,105 Identification of this tumor type in particular further reinforces the idea of transdifferentiation as a mechanism of therapy resistance.

MECHANISMS OF TUMOR TRANSDIFFERENTIATION POSTTHERAPY

At the molecular level, several key factors are implicated in driving lineage plasticity and transdifferentiation of adenocarcinoma in response to hormone therapy and AR loss, and significant crosstalk exists between many drivers and downstream effectors (Table 1). AR and the androgen signaling pathway are known to protect the luminal epithelial cell lineage in AR-dependent LNCaP PCa cells, where loss of AR induces neuronal cell morphology and induces NSE expression.106,107,108 The epithelial cell lineage transcription factor and AR pioneer factor forkhead box protein A1 (FOXA1) has been shown to inhibit interleukin-8 (IL-8) expression, thereby preventing MAPK/ extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway-mediated progression to NE tumors.109,110 Similarly, the AR-regulated TMPRSS2-ERG fusion has been shown to repress a neuronal gene signature,111 although the exact mechanism and effect of additional mutations present in the cells studied remains unclear. In contrast, the NE cell transcription factor FOXA2 has been shown to cooperate with stabilized hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha subunit (HIF-1α) to promote NE tumor progression in the prostate.112,113

Table 1.

Key molecular drivers and effectors of androgen receptor-independent lineage reprogramming

| Potential drivers | Known downstream effectors | Final tumor cell outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMPRSS2-ERG loss | Increased CD44+ cells; other uncharacterized factors | Repression of neuronal gene signature | Mounir et al.,111 Li et al.124 |

| FOXA1 loss | IL-8 expression | Increased MAPK/ERK signaling; progression to NE tumor phenotype | Kim et al.,109 Zhao et al.110 |

| FOXA2 gain | HIF-1α co-activation of HES6, SOX9, JMJD1A expression | Development of hypoxia-dependent NE tumor phenotype (in the TRAMP model) | Eisinger-Mathason et al.,112 Qi et al.113 |

| RB1/TP53 loss | Enhanced SRRM4 function with concomitant AR inhibition; decreased NKX3.1; SOX2 activity; upregulated PEG10; other uncharacterized factors | Gain of neural cell differentiation genes; transdifferentiation to AR-negative/ NE-positive tumors; increased NE cell proliferation | Rickman et al.,52 Ku et al.,53 Mu et al.,54 Lin et al.,89 Grabowska et al.,115 Masumori et al.,116 Masumori et al.,117 Yu et al.,118 Bethel et al.,119 Akamatsu et al.,122 Li et al.124 |

| RB1/TP53/PTEN loss | EZH2 and SOX2-mediated reprogramming | Lineage plasticity; transdifferentiation to AR-negative/NE-positive tumors | Ku et al.53 |

| PTEN/TP53 loss | SOX11-mediated reprogramming with decreased NKX3.1; other Y | Lineage plasticity; transdifferentiation to AR-negative/NE-positive tumors | Zou et al.,55 Blee et al.,121 Martin et al.123 |

| NKX3.1 loss | FOXA1 and HOXB13 downregulation; G9a co-activation of UTY expression | Altered histone methylation; loss of differentiated prostate structures | Bethel et al.,119 Dutta et al.120 |

| SRRM4-mediated alternative splicing of neural cell differentiation genes | REST decrease and REST4 increase in the context of castration alone, RB1 loss, or TP53 loss | Gain of neural cell differentiation genes; altered cell morphology (LNCaP) in combination with AR inhibition; transdifferentiation to AR-negative/NE-positive cells | Li et al.,124 Gopalakrishnan et al.,133 Raj et al.134 |

| BRN2 gain | SOX2 activity and co-regulation of SOX2 target genes | NE tumor progression | Bishop et al.,125 Dailey et al.126 |

| MYCN/AURKA amplification | EZH2-mediated reprogramming | NE tumor progression | Beltran et al.,84 Dardenne et al.,127 Lee et al.128 |

| EZH2/CBX2 expression | Altered PRC2 methylation activity and H3K27me3 “reading” | AR-independence; NE characteristics; lineage plasticity | Beltran et al.,49 Beltran et al.,84 Martin et al.,123 Bohrer et al.,129 Varamballyet al., 130 Clermont et al.,131 |

| FGF signaling | Activated MAPK pathway; ID1 and BMP expression | Increased cell growth and decreased apoptosis in AR-negative/NE-negative cells | Bluemn et al.95 |

| DEK gain* | Altered chromatin state; other uncharacterized factors | NE tumor progression | Lin et al.132 |

*Further validation needed to truly define DEK as an epigenetic driver. AR: androgen receptor; AURKA: aurora kinase A; BMP: bone morphogenetic protein; BRN2: brain-specific homeobox/POU domain protein 2; CBX2: chromobox homolog 2; DEK: DEK proto-oncogene; EZH2: enhancer of zeste homolog 2; FGF: fibroblast growth factor; FOXA1: forkhead box protein A1; FOXA2: forkhead box protein A2; H3K27me3: histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation; HES6: hes family bHLH transcription factor 6; HIF-1α: hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha subunit; HOXB13: homeobox B13; ID1: inhibitor of DNA binding 1, HLH protein; IL-8: interleukin-8; JMJD1A: jumonji domain-containing 1A; NE: neuroendocrine; NKX3.1: NK3 homeobox 1; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinases; MYCN: neuroblastoma-derived v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral related oncogene; PRC2: polycomb repressive complex 2; PTEN: phosphatase and tensin homolog; RB1: retinoblastoma 1; REST: repressor element (RE)-1 silencing transcription factor; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase; PEG10: Paternally Expressed 10; SOX: sex-determining region Y-box; SRRM4: serine/arginine repetitive matrix 4; TMPRSS2-ERG: transmembrane protease, serine 2-ETS-related gene; TP53: tumor protein p53; UTY: ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat containing, Y-linked; TRAMP: transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate

Frequent alterations found in CRPC are also implicated in promoting AR-negative/NE-positive tumor reprogramming. Analysis of human CRPC cohorts highlights that retinoblastoma 1 (RB1) copy number loss and TP53 mutations frequently co-occur together in hormone therapy-resistant tumors,49,114 and further study in mouse models has revealed a link with lineage plasticity. The well-established transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) model of PCa, which expresses SV40 large and small T antigens, has disrupted RB and p53 activity and ultimately progresses to a poorly differentiated state with NE characteristics.52 A second model of PCa (LADY) consists of multiple lines that express solely the SV40 large T antigen and progresses similarly.115,116,117,118 Interestingly, tumors in the TRAMP model also have progressively decreased expression of NKX3.1,119 suggesting dysregulated prostate cell differentiation as a possible driver. Not surprisingly, loss of NKX3.1 in the developed mouse prostate leads to downregulation of genes associated with prostate differentiation.120

A recent study highlighted that Rb1 and Trp53 loss in the mouse prostate as well as in AR-dependent LNCaP cells and CWR22Pc-EP xenografts confers antiandrogen resistance through SOX2-mediated reprogramming to AR-independent NE-like cells.54 In support of this, a second report emphasized the role of Rb1, Trp53, and Pten loss in lineage plasticity-mediated resistance, where combined loss of these three genes also resulted in reprogramming mediated by epigenetic modifier enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) and lineage transcription factor SOX2 to AR-independent, therapy-resistant cells.53 A recent study of dedifferentiated, PTEN/TP53-altered tumors has revealed that the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion may restrict the observed lineage plasticity in ERG-positive, PTEN/TP53-altered tumors.121 A detailed time-course study of a hormone-naïve patient-derived xenograft model demonstrated that in the context of RB1/TP53 mutation or loss, upregulated paternally expressed 10 (PEG10) promotes increased cell growth in NE-like tumor cells after castration.89,122 Alternatively, Pten and Trp53 loss is also sufficient to induce prostate tumor cell lineage plasticity in mice, although further orthotopic transplantations of transformed cells resulted in the formation of orthotopic PIN and adenocarcinoma only.123 Similarly, in a CRPC tumor model with Pten and Trp53 loss and heterozygous loss of NKX3.1, transdifferentiation to a NE-like tumor was observed after abiraterone treatment, mediated by neural differentiation factor SOX11.55 Alternative splicing has also been implicated in transdifferentiation to AR-negative/NE-positive cells. In the context of RB1 loss, TP53 loss, or castration, increased expression of the alternative splicing factor SRRM4, which leads to neural-specific exon insertion in genes important for neural cell differentiation, was shown to drive transdifferentiation of LNCaP cells in a xenograft model.124

Intriguingly, SOX transcription factors such as SOX2 and SOX11 are highlighted in multiple models and patient cohorts as potential mediators of AR-independent NE-like tumor phenotypes.53,54,55,125 Recent study of a LNCaP xenograft model that developed enzalutamide-resistance and a AR-negative/NE-positive tumor phenotype after castration revealed significantly increased levels of brain-specific homeobox/POU domain protein 2 (BRN2), a master regulatory neural transcription factor, as AR levels decreased.125 BRN2 expression was shown to be directly repressed by AR. This inverse correlation between BRN2 and AR was also validated in cohorts of patient adenocarcinomas versus CRPCs versus NEPCs.49,84,125 Additional findings that BRN2 co-regulates neural SOX2 target genes and SOX2 activity suggest BRN2 as a major driver and upstream regulator of the SOX-mediated NE tumor phenotype.125,126

In addition to the RB1/PTEN/TP53 axis, MYCN amplification and AURKA amplification have been linked with the loss of AR and progression to poorly differentiated NE tumors, which is also mediated by EZH2, the catalytic subunit of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) responsible for histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3).84,127,128 EZH2 expression is repressed indirectly by AR129 and is associated with PCa progression, AR-independent NE-like tumors, and plasticity.49,84,130 Interestingly, EZH2 and the H3K27me3 chromobox reader chromobox homolog 2 (CBX2) were found to be highly expressed in both a NE xenograft model and NE patient tumors compared to adenocarcinoma.89,131 Expression of another chromatin modulator, DEK, which induces DNA supercoils and can recruit chromatin remodelers, has also been associated with the transition to AR-independent NE tumors in both a NE xenograft model and patient tumors,89,132 further highlighting a role for dysregulated epigenetics in prostate tumor reprogramming after hormone therapies.

These studies collectively emphasize a complex network of cooperating genetic and epigenetic alterations that respond to ADT and AR-targeted therapies by initiating plasticity-mediated therapy resistance through master downstream regulators such as SOX genes, epigenetic remodelers such as EZH2, and lineage-related transcription factors such as FOXA1 or FOXA2 (Figure 1). Further studies to gain a comprehensive understanding of frequently overlapped alterations in patient tumors and the ability to induce transdifferentiation in specific contexts are required.

CONCLUSIONS

Although ADT and antiandrogen therapies are well-established therapeutic options for advanced PCa, unavoidable resistance through mechanisms such as lineage plasticity remains a key barrier. It has become clear that many prevalent PCa-associated alterations can contribute to lineage reprogramming of AR-positive cancer cells after therapy. The precise mutational networks and key regulatory factors that drive plasticity within any tumor represent promising therapeutic targets in combination with hormone therapies. Future efforts must focus on standardizing the molecular and morphological characterizations of pre- and posttherapy tumor subtypes. In addition, the complex regulatory networks that contribute to lineage reprogramming and therapy resistance in the context of each tumor subtype must be elucidated. In particular, a better understanding is needed of the relationship between AR-positive/NE-negative, AR-negative/NE-negative, and AR-negative/NE-positive tumor cells that drive tumor progression after therapy. These studies may reveal new therapeutic targets and combination therapies that prevent the development of further drug resistance.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AMB and HH defined the scope of the review, performed a comprehensive literature search, and wrote the review. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

Both authors declared no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (CA134514, CA130908, CA193239, and CA203849 to H Huang) and the Department of Defense (DOD) (W81XWH-14-1-0486 to H Huang).

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buzzoni C, Auvinen A, Roobol MJ, Carlsson S, Moss SM, et al. Metastatic prostate cancer incidence and prostate-specific antigen testing: new insights from the european randomized study of screening for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:885–90. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pron G. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based population screening for prostate cancer: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2015;15:1–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tawfik A. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based population screening for prostate cancer: an economic analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2015;15:1–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayes JH, Barry MJ. Screening for prostate cancer with the prostate-specific antigen test: a review of current evidence. JAMA. 2014;311:1143–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson PA, Arora VK, Sawyers CL. Emerging mechanisms of resistance to androgen receptor inhibitors in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:701–11. doi: 10.1038/nrc4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paller CJ, Antonarakis ES. Management of biochemically recurrent prostate cancer after local therapy: evolving standards of care and new directions. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2013;11:14–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huggins C, Hodges CV. Studies on prostatic cancer. I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. CA Cancer J Clin. 1972;22:232–40. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.22.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris WP, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Androgen deprivation therapy: progress in understanding mechanisms of resistance and optimizing androgen depletion. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6:76–85. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrie SE, Potter GA, Goddard PM, Haynes BP, Dowsett M, et al. Pharmacology of novel steroidal inhibitors of cytochrome P450(17) alpha (17 alpha-hydroxylase/C17-20 lyase) J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;50:267–73. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung ME, Ouk S, Yoo D, Sawyers CL, Chen C, et al. Structure-activity relationship for thiohydantoin androgen receptor antagonists for castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) J Med Chem. 2010;53:2779–96. doi: 10.1021/jm901488g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid AH, Attard G, Barrie E, de Bono JS. CYP17 inhibition as a hormonal strategy for prostate cancer. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008;5:610–20. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scher H, Beer T, Higano C, Logothetis C, Shelkey J, et al. Phase I-II study of MDV3100 in castration resistant prostate cancer. The Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium. EJC Suppl. 2008;6:51–2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maity SN, Titus MA, Gyftaki R, Wu G, Lu JF, et al. Targeting of CYP17A1 lyase by VT-464 inhibits adrenal and intratumoral androgen biosynthesis and tumor growth of castration resistant prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35354. doi: 10.1038/srep35354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rathkopf DE, Antonarakis ES, Shore ND, Tutrone RF, Alumkal JJ, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of apalutamide (ARN-509) in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with and without prior abiraterone acetate and prednisone. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3544–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clegg NJ, Wongvipat J, Joseph JD, Tran C, Ouk S, et al. ARN-509: a novel antiandrogen for prostate cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1494–503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shore ND. Darolutamide (ODM-201) for the treatment of prostate cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:945–52. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2017.1329820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shore ND, Tammela TL, Massard C, Bono P, Aspegren J, et al. Safety and antitumour activity of ODM-201 (BAY-1841788) in chemotherapy-naive and CYP17 inhibitor-naïve patients: follow-up from the ARADES and ARAFOR trials. Eur Urol Focus. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.01.015. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.01.015. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Mol E, Fenwick RB, Phang CT, Buzon V, Szulc E, et al. EPI-001, a compound active against castration-resistant prostate cancer, targets transactivation unit 5 of the androgen receptor. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:2499–505. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bambury RM, Rathkopf DE. Novel and next-generation androgen receptor-directed therapies for prostate cancer: beyond abiraterone and enzalutamide. Urol Oncol. 2016;34:348–55. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berthold DR, Pond GR, Soban F, de Wit R, Eisenberger M, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer: updated survival in the TAX327 study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:242–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Harmenberg U, Joensuu T, McDermott R, Hervonen P, et al. 2-weekly versus 3-weekly docetaxel to treat castration-resistant advanced prostate cancer: a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:117–24. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall SJ, Klotz L, Pantuck AJ, George DJ, Whitmore JB, et al. Integrated safety data from 4 randomized, double-blind, controlled trials of autologous cellular immunotherapy with sipuleucel-T in patients with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;186:877–81. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O’Sullivan JM, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sartor O, Coleman R, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, et al. Effect of radium-223 dichloride on symptomatic skeletal events in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases: results from a phase 3, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:738–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claessens F, Helsen C, Prekovic S, Van den Broeck T, Spans L, et al. Emerging mechanisms of enzalutamide resistance in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:712–6. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbieri CE, Baca SC, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, Blattner M, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent SPOP, FOXA1 and MED12 mutations in prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:685–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grasso CS, Wu YM, Robinson DR, Cao X, Dhanasekaran SM, et al. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2012;487:239–43. doi: 10.1038/nature11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beltran H, Yelensky R, Frampton GM, Park K, Downing SR, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of advanced prostate cancer identifies potential therapeutic targets and disease heterogeneity. Eur Urol. 2013;63:920–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H, Gopalan A, Xiao Y, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki H, Sato N, Watabe Y, Masai M, Seino S, et al. Androgen receptor gene mutations in human prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;46:759–65. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90316-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veldscholte J, Ris-Stalpers C, Kuiper GG, Jenster G, Berrevoets C, et al. Amutation in the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor of human LNCaP cells affects steroid binding characteristics and response to anti-androgens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:534–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balbas MD, Evans MJ, Hosfield DJ, Wongvipat J, Arora VK, et al. Overcoming mutation-based resistance to antiandrogens with rational drug design. Elife. 2013;2:e00499. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo Z, Yang X, Sun F, Jiang R, Linn DE, et al. Anovel androgen receptor splice variant is up-regulated during prostate cancer progression and promotes androgen depletion-resistant growth. Cancer Resh. 2009;69:2305–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu R, Dunn TA, Wei S, Isharwal S, Veltri RW, et al. Ligand-independent androgen receptor variants derived from splicing of cryptic exons signify hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:16–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Chan SC, Brand LJ, Hwang TH, Silverstein KA, et al. Androgen receptor splice variants mediate enzalutamide resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2013;73:483–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Efstathiou E, Titus M, Wen S, Hoang A, Karlou M, et al. Molecular characterization of enzalutamide-treated bone metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;67:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mostaghel EA, Marck BT, Plymate SR, Vessella RL, Balk S, et al. Resistance to CYP17A1 inhibition with abiraterone in castration-resistant prostate cancer: induction of steroidogenesis and androgen receptor splice variants. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5913–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koivisto P, Kononen J, Palmberg C, Tammela T, Hyytinen E, et al. Androgen receptor gene amplification: a possible molecular mechanism for androgen deprivation therapy failure in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:314–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmberg C, Koivisto P, Hyytinen E, Isola J, Visakorpi T, et al. Androgen receptor gene amplification in a recurrent prostate cancer after monotherapy with the nonsteroidal potent antiandrogen Casodex (bicalutamide) with a subsequent favorable response to maximal androgen blockade. Eur Urol. 1997;31:216–9. doi: 10.1159/000474453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Visakorpi T, Hyytinen E, Koivisto P, Tanner M, Keinanen R, et al. In vivo amplification of the androgen receptor gene and progression of human prostate cancer. Nature Genet. 1995;9:401–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–9. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arora VK, Schenkein E, Murali R, Subudhi SK, Wongvipat J, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor confers resistance to antiandrogens by bypassing androgen receptor blockade. Cell. 2013;155:1309–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Isikbay M, Otto K, Kregel S, Kach J, Cai Y, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor activity contributes to resistance to androgen-targeted therapy in prostate cancer. Horm Cancer. 2014;5:72–89. doi: 10.1007/s12672-014-0173-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yemelyanov A, Bhalla P, Yang X, Ugolkov A, Iwadate K, et al. Differential targeting of androgen and glucocorticoid receptors induces ER stress and apoptosis in prostate cancer cells: a novel therapeutic modality. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:395–406. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.2.18945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Claessens F, Denayer S, Van Tilborgh N, Kerkhofs S, Helsen C, et al. Diverse roles of androgen receptor (AR) domains in AR-mediated signaling. Nucl Recept Signal. 2008;6:e008. doi: 10.1621/nrs.06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Denayer S, Helsen C, Thorrez L, Haelens A, Claessens F. The rules of DNA recognition by the androgen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:898–913. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beltran H, Prandi D, Mosquera JM, Benelli M, Puca L, et al. Divergent clonal evolution of castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22:298–305. doi: 10.1038/nm.4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parimi V, Goyal R, Poropatich K, Yang XJ. Neuroendocrine differentiation of prostate cancer: a review. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2014;2:273–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun Y, Niu J, Huang J. Neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2009;1:148–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rickman DS, Beltran H, Demichelis F, Rubin MA. Biology and evolution of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Nat Med. 2017;23:1–10. doi: 10.1038/nm.4341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ku SY, Rosario S, Wang Y, Mu P, Seshadri M, et al. Rb1 and Trp53 cooperate to suppress prostate cancer lineage plasticity, metastasis, and antiandrogen resistance. Science. 2017;355:78–83. doi: 10.1126/science.aah4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mu P, Zhang Z, Benelli M, Karthaus WR, Hoover E, et al. SOX2 promotes lineage plasticity and antiandrogen resistance in TP53- and RB1-deficient prostate cancer. Science. 2017;355:84–8. doi: 10.1126/science.aah4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zou M, Toivanen R, Mitrofanova A, Floch N, Hayati S, et al. Transdifferentiation as a mechanism of treatment resistance in a mouse model of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:736–49. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abate-Shen C, Shen MM. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2410–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.819500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayward SW, Rosen MA, Cunha GR. Stromal-epithelial interactions in the normal and neoplastic prostate. Br J Urol. 1997;79(Suppl 2):18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1997.tb16917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meeks JJ, Schaeffer EM. Genetic regulation of prostate development. J Androl. 2011;32:210–7. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.110.011577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Powers GL, Marker PC. Recent advances in prostate development and links to prostatic diseases. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2013;5:243–56. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cunha GR, Lung B. The possible influence of temporal factors in androgenic responsiveness of urogenital tissue recombinants from wild-type and androgen-insensitive (Tfm) mice. J Exp Zool. 1978;205:181–93. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402050203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cunha GR. The role of androgens in the epithelio-mesenchymal interactions involved in prostatic morphogenesis in embryonic mice. Anat Rec. 1973;175:87–96. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091750108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cunha GR, Fujii H, Neubauer BL, Shannon JM, Sawyer L, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in prostatic development. I. morphological observations of prostatic induction by urogenital sinus mesenchyme in epithelium of the adult rodent urinary bladder. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1662–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.6.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pritchard CC, Nelson PS. Gene expression profiling in the developing prostate. Differentiation. 2008;76:624–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prins GS, Putz O. Molecular signaling pathways that regulate prostate gland development. Differentiation. 2008;76:641–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Husmann DA, McPhaul MJ, Wilson JD. Androgen receptor expression in the developing rat prostate is not altered by castration, flutamide, or suppression of the adrenal axis. Endocrinology. 1991;128:1902–6. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-4-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Prins GS, Birch L. The developmental pattern of androgen receptor expression in rat prostate lobes is altered after neonatal exposure to estrogen. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1303–14. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.3.7867585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shannon JM, Cunha GR. Autoradiographic localization of androgen binding in the developing mouse prostate. Prostate. 1983;4:367–73. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990040406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takeda H, Mizuno T, Lasnitzki I. Autoradiographic studies of androgen-binding sites in the rat urogenital sinus and postnatal prostate. J Endocrinol. 1985;104:87–92. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1040087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhatia-Gaur R, Donjacour AA, Sciavolino PJ, Kim M, Desai N, et al. Roles for Nkx3. 1 in prostate development and cancer. Genes Dev. 1999;13:966–77. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abate-Shen C, Shen MM, Gelmann E. Integrating differentiation and cancer: the Nkx3. 1 homeobox gene in prostate organogenesis and carcinogenesis. Differentiation. 2008;76:717–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: new prospects for old challenges. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1967–2000. doi: 10.1101/gad.1965810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Epstein JI, Amin MB, Beltran H, Lotan TL, Mosquera JM, et al. Proposed morphologic classification of prostate cancer with neuroendocrine differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:756–67. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Signoretti S, Pires MM, Lindauer M, Horner JW, Grisanzio C, et al. p63 regulates commitment to the prostate cell lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11355–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500165102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang ZA, Mitrofanova A, Bergren SK, Abate-Shen C, Cardiff RD, et al. Lineage analysis of basal epithelial cells reveals their unexpected plasticity and supports a cell-of-origin model for prostate cancer heterogeneity. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:274–83. doi: 10.1038/ncb2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang J, Zhu HH, Chu M, Liu Y, Zhang C, et al. Symmetrical and asymmetrical division analysis provides evidence for a hierarchy of prostate epithelial cell lineages. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4758. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shafer ME, Nguyen AH, Tremblay M, Viala S, Beland M, et al. Lineage specification from prostate progenitor cells requires gata3-dependent mitotic spindle orientation. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8:1018–31. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.De Marzo AM, Nelson WG, Meeker AK, Coffey DS. Stem cell features of benign and malignant prostate epithelial cells. J Urol. 1998;160:2381–92. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199812020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xue Y, Smedts F, Debruyne FM, de la Rosette JJ, Schalken JA. Identification of intermediate cell types by keratin expression in the developing human prostate. Prostate. 1998;34:292–301. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980301)34:4<292::aid-pros7>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ousset M, Van Keymeulen A, Bouvencourt G, Sharma N, Achouri Y, et al. Multipotent and unipotent progenitors contribute to prostate postnatal development. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1131–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang S, Gao J, Lei Q, Rozengurt N, Pritchard C, et al. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:209–21. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choi N, Zhang B, Zhang L, Ittmann M, Xin L. Adult murine prostate basal and luminal cells are self-sustained lineages that can both serve as targets for prostate cancer initiation. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:253–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Qin J, Liu X, Laffin B, Chen X, Choy G, et al. The PSA(-/lo) prostate cancer cell population harbors self-renewing long-term tumor-propagating cells that resist castration. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:556–69. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shen CN, Burke ZD, Tosh D. Transdifferentiation, metaplasia and tissue regeneration. Organogenesis. 2004;1:36–44. doi: 10.4161/org.1.2.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beltran H, Rickman DS, Park K, Chae SS, Sboner A, et al. Molecular characterization of neuroendocrine prostate cancer and identification of new drug targets. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:487–95. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lotan TL, Gupta NS, Wang W, Toubaji A, Haffner MC, et al. ERG gene rearrangements are common in prostatic small cell carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:820–8. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Williamson SR, Zhang S, Yao JL, Huang J, Lopez-Beltran A, et al. ERG-TMPRSS2 rearrangement is shared by concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and prostatic small cell carcinoma and absent in small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: evidence supporting monoclonal origin. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1120–7. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Guo CC, Dancer JY, Wang Y, Aparicio A, Navone NM, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in small cell carcinoma of the prostate. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hansel DE, Nakayama M, Luo J, Abukhdeir AM, Park BH, et al. Shared TP53 gene mutation in morphologically and phenotypically distinct concurrent primary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Prostate. 2009;69:603–9. doi: 10.1002/pros.20910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lin D, Wyatt AW, Xue H, Wang Y, Dong X, et al. High fidelity patient-derived xenografts for accelerating prostate cancer discovery and drug development. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1272–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2921-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huss WJ, Gregory CW, Smith GJ. Neuroendocrine cell differentiation in the CWR22 human prostate cancer xenograft: association with tumor cell proliferation prior to recurrence. Prostate. 2004;60:91–7. doi: 10.1002/pros.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Noordzij MA, van Weerden WM, de Ridder CM, van der Kwast TH, Schroder FH, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in human prostatic tumor models. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:859–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aparicio A, Tzelepi V. Neuroendocrine (small-cell) carcinomas: why they teach us essential lessons about prostate cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2014;28:831–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Roudier MP, True LD, Higano CS, Vesselle H, Ellis W, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity of end-stage prostate carcinoma metastatic to bone. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:646–53. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang W, Epstein JI. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate. A morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 95 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:65–71. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318058a96b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bluemn EG, Coleman IM, Lucas JM, Coleman RT, Hernandez-Lopez S, et al. Androgen receptor pathway-independent prostate cancer is sustained through FGF signaling. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:474–89.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Beltran H, Tomlins S, Aparicio A, Arora V, Rickman D, et al. Aggressive variants of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2846–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yao JL, Madeb R, Bourne P, Lei J, Yang X, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate: an immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:705–12. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200606000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tanaka M, Suzuki Y, Takaoka K, Suzuki N, Murakami S, et al. Progression of prostate cancer to neuroendocrine cell tumor. Int J Urol. 2001;8:431–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Miyoshi Y, Uemura H, Kitami K, Satomi Y, Kubota Y, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiated small cell carcinoma presenting as recurrent prostate cancer after androgen deprivation therapy. BJU Int. 2001;88:982–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Helpap B. Morphology and therapeutic strategies for neuroendocrine tumors of the genitourinary tract. Cancer. 2002;95:1415–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Evans AJ, Humphrey PA, Belani J, van der Kwast TH, Srigley JR. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of prostate: a clinicopathologic summary of 7 cases of a rare manifestation of advanced prostate cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:684–93. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200606000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Weaver MG, Abdul-Karim FW, Srigley J, Bostwick DG, Ro JY, et al. Paneth cell-like change of the prostate gland. A histological, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:62–8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Azzopardi JG, Evans DJ. Argentaffin cells in prostatic carcinoma: differentiation from lipofuscin and melanin in prostatic epithelium. J Pathol. 1971;104:247–51. doi: 10.1002/path.1711040406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hirano D, Okada Y, Minei S, Takimoto Y, Nemoto N. Neuroendocrine differentiation in hormone refractory prostate cancer following androgen deprivation therapy. Eur Urol. 2004;45:586–92. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Berruti A, Mosca A, Porpiglia F, Bollito E, Tucci M, et al. Chromogranin A expression in patients with hormone naive prostate cancer predicts the development of hormone refractory disease. J Urol. 2007;178:838–43. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wright ME, Tsai MJ, Aebersold R. Androgen receptor represses the neuroendocrine transdifferentiation process in prostate cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1726–37. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xie S, Lin HK, Ni J, Yang L, Wang L, et al. Regulation of interleukin-6-mediated PI3K activation and neuroendocrine differentiation by androgen signaling in prostate cancer LNCaP cells. Prostate. 2004;60:61–7. doi: 10.1002/pros.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Murillo H, Huang H, Schmidt LJ, Smith DI, Tindall DJ. Role of PI3K signaling in survival and progression of LNCaP prostate cancer cells to the androgen refractory state. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4795–805. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kim J, Jin H, Zhao JC, Yang YA, Li Y, et al. FOXA1 inhibits prostate cancer neuroendocrine differentiation. Oncogene. 2017;36:4072–80. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhao Y, Tindall DJ, Huang H. Modulation of androgen receptor by FOXA1 and FOXO1 factors in prostate cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2014;10:614–9. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mounir Z, Lin F, Lin VG, Korn JM, Yu Y, et al. TMPRSS2:ERG blocks neuroendocrine and luminal cell differentiation to maintain prostate cancer proliferation. Oncogene. 2015;34:3815–25. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Eisinger-Mathason TS, Simon MC. HIF-1alpha partners with FoxA2, a neuroendocrine-specific transcription factor, to promote tumorigenesis. Cancer cell. 2010;18:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Qi J, Nakayama K, Cardiff RD, Borowsky AD, Kaul K, et al. Siah2-dependent concerted activity of HIF and FoxA2 regulates formation of neuroendocrine phenotype and neuroendocrine prostate tumors. Cancer cell. 2010;18:23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tan HL, Sood A, Rahimi HA, Wang W, Gupta N, et al. Rb loss is characteristic of prostatic small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:890–903. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Grabowska MM, DeGraff DJ, Yu X, Jin RJ, Chen Z, et al. Mouse models of prostate cancer: picking the best model for the question. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014;33:377–97. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9487-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Masumori N, Thomas TZ, Chaurand P, Case T, Paul M, et al. A probasin-large T antigen transgenic mouse line develops prostate adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma with metastatic potential. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2239–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Masumori N, Tsuchiya K, Tu WH, Lee C, Kasper S, et al. An allograft model of androgen independent prostatic neuroendocrine carcinoma derived from a large probasin promoter-T antigen transgenic mouse line. J Urol. 2004;171:439–42. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000099826.63103.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yu X, Cates JM, Morrissey C, You C, Grabowska MM, et al. SOX2 expression in the developing, adult, as well as, diseased prostate. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17:301–9. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2014.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bethel CR, Bieberich CJ. Loss of Nkx3. 1 expression in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model. Prostate. 2007;67:1740–50. doi: 10.1002/pros.20579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dutta A, Le Magnen C, Mitrofanova A, Ouyang X, Califano A, et al. Identification of an NKX3. 1-G9a-UTY transcriptional regulatory network that controls prostate differentiation. Science. 2016;352:1576–80. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Blee AM, He Y, Yang Y, Ye Z, Yan Y, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG controls luminal epithelial lineage and antiandrogen sensitivity in PTEN and TP53-mutated prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0653. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0653. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Akamatsu S, Wyatt AW, Lin D, Lysakowski S, Zhang F, et al. the placental gene PEG10 promotes progression of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Cell Rep. 2015;12:922–36. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Martin P, Liu YN, Pierce R, Abou-Kheir W, Casey O, et al. Prostate epithelial Pten/TP53 loss leads to transformation of multipotential progenitors and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:422–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Li Y, Donmez N, Sahinalp C, Xie N, Wang Y, et al. SRRM4 drives neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate adenocarcinoma under androgen receptor pathway inhibition. Eur Urol. 2017;71:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bishop JL, Thaper D, Vahid S, Davies A, Ketola K, et al. The master neural transcription factor BRN2 is an androgen receptor-suppressed driver of neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:54–71. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Dailey L, Basilico C. Coevolution of HMG domains and homeodomains and the generation of transcriptional regulation by Sox/POU complexes. J Cell Physiol. 2001;186:315–28. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(2001)9999:9999<000::AID-JCP1046>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Dardenne E, Beltran H, Benelli M, Gayvert K, Berger A, et al. N-Myc induces an ezh2-mediated transcriptional program driving neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Cancer cell. 2016;30:563–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lee JK, Phillips JW, Smith BA, Park JW, Stoyanova T, et al. N-Myc drives neuroendocrine prostate cancer initiated from human prostate Epithelial Cells. Cancer cell. 2016;29:536–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bohrer LR, Chen S, Hallstrom TC, Huang H. Androgens suppress EZH2 expression via retinoblastoma (RB) and p130-dependent pathways: a potential mechanism of androgen-refractory progression of prostate cancer. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5136–45. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Varambally S, Dhanasekaran SM, Zhou M, Barrette TR, Kumar-Sinha C, et al. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature. 2002;419:624–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Clermont PL, Lin D, Crea F, Wu R, Xue H, et al. Polycomb-mediated silencing in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:40. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lin D, Dong X, Wang K, Wyatt AW, Crea F, et al. Identification of DEK as a potential therapeutic target for neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:1806–20. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gopalakrishnan V. REST and the RESTless: in stem cells and beyond. Future Neurol. 2009;4:317–29. doi: 10.2217/fnl.09.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Raj B, Irimia M, Braunschweig U, Sterne-Weiler T, O’Hanlon D, et al. A global regulatory mechanism for activating an exon network required for neurogenesis. Mol Cell. 2014;56:90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]