Abstract

Background

Primary lactose intolerance (PLI) is a gradual decrease of lactase activity that usually manifests at the age of 1–5 years. It has been proved that PLI is related to a single-nucleotide polymorphism of the lactase (LCT) gene.

Objective

An evaluation was performed on the usefulness of genetic tests in detecting LCT 13910C>T and 22018G>A polymorphisms in diagnosing lactose intolerance in children.

Methods

The study group included 99 children aged from 2 months to 16.5 years with different digestive tract symptoms. In all patients a hydrogen breath test (HBT) was conducted and blood samples were collected to determine LCT polymorphisms. PLI was defined as the presence of the 13910CC and/or 22018GG polymorphism in patients with a positive HBT result.

Results

In the group younger than 6 years, no statistically significant correlation was observed between the 13910CC and/or 22018GG LCT polymorphisms and HBT result. In the group of children older than 6, a statistically significant correlation between the 13910CC (p = 0.0011) and 22018GG (p = 0.003) LCT polymorphisms and HBT result was detected.

Conclusions

In children older than 6, the result of genetic testing based on LCT 13910C>T and 22018G>A polymorphisms may diagnose lactose intolerance.

Keywords: Hydrogen breath test, hypolactasia, lactose intolerance, LCT polymorphism, primary lactose intolerance

Key summary

What’s known?

Lactose intolerance is the most common food intolerance in the world.

A relationship was found between the 13910C>T and 22018G>A lactase (LCT) gene polymorphisms and primary lactose intolerance.

What’s new?

In the Central European population, 56.6% of children present with a genetic predisposition to hypolactasia.

Genetic testing including the 13910C>T and 22018G>A LCT polymorphisms is useful in diagnosing lactose intolerance, but only for children older than 6 years.

Introduction

Lactose intolerance (LI) is the most common food intolerance in the world.1 It is estimated that it affects more than two-thirds of the global population.2,3 According to the definition, food intolerance is a set of symptoms experienced after the intake of food that does not involve immunological mechanisms.4

LI results from a lack of or a decreased activity of the enzyme lactase, found in the brush border of the small intestine.2 Undigested lactose works in the digestive tract as an osmotically active agent causing water and electrolytes accumulation in the intestinal lumen and accelerates peristalsis. In the large intestine, free lactose becomes a substrate for bacteria, where it ferments into lactic acid, methane, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, etc.5 This process is responsible for clinical symptoms – cramping abdominal pain, flatulence, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting – after the intake of food products containing lactose.1,6

LI may be a secondary process with regard to other factors damaging the small intestine, including viral and bacterial infections, inflammatory processes of the small intestine (Leśniowski-Crohn’s disease, coeliac disease or enteropathies in food allergy) or extreme malnutrition.5–8 Secondary lactose intolerance (SLI) is not a permanent condition. After the root cause is eliminated, the epithelium in the intestines regenerates and the enzymes of the brush border resume their proper secretion.

Primary lactose intolerance (PLI) is a genetically conditioned process involving a gradual disappearance of the activity of lactase in the intestines, starting between the ages of 1 and 5 years, depending on the ethnic group.2 The process is primarily found among Asians, in the Mediterranean Basin and among black individuals. In these ethnic groups LI is found in 60% to 100% of the adult population.2 Among white individuals, the process of decreasing intestinal activity of lactose usually starts after the age of 4 to 5.2 In Poland, PLI is diagnosed in 31% to 37.5% of adults.9,10 PLI is caused by the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) within the promoter of the LCT gene, which codes lactase. In the Caucasian race, there is a documented relation between the 13910C>T and 22018G>A polymorphisms and the incidence of hypolactasia.8,11,12 The presence of 13910CC and 22018GG genotypes conditions a gradual decrease in lactase activity which progresses with age, whereas the presence of 13910CT and 13910TT as well as 22018GA and 22018AA genotypes causes lifelong high lactase activity.

In other ethnic groups, other genetic polymorphisms are also significant.8

Owing to the growing popularity of genetic testing, it seems essential to evaluate the usefulness of such tests in diagnosing LI in children.

The objective of this paper is to evaluate the usefulness of genetic tests detecting 13910C>T and 22018G>A LCT gene polymorphisms in diagnosing LI in children.

Materials and methods

The study group included 99 children between the ages of 2 months and 16.5 years, of whom 58 children under age 6 (2.7 ± 1.9) and 41 children older than 6 (9.6 ± 2.8) were admitted to hospital in 2015–2016 at the Clinic of the Department of Paediatrics, Immunology and Nephrology at the Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital Research Institute in Łódź. The admitted children matched at least one of the clinical criteria, defined separately for babies and older children.

Qualification criteria for infants (≤1 year) included the following:

chronic or recurring diarrhoea;

intense symptoms of baby colic;

insufficient weight gain as compared with the expected result or being underweight;

frequent regurgitation.

Qualification criteria for children aged 2–18 years included the following:

chronic abdominal pain;

chronic or recurring diarrhoea;

periodical loose bowel movements, yet not matching the definition of diarrhoea;

symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux;

Children with diagnosed organic bowel disease (coeliac disease or another enteropathy confirmed with histopathological examination, nonspecific inflammatory bowel diseases), new-borns and prematurely born children were excluded from the study.

In all children a hydrogen breath test (HBT) was conducted after the oral administration of lactose – 1.75–2.0 g/kg of body weight, maximum 50 g. Babies fed exclusively with their mothers’ milk were examined a minimum of three hours after the last feeding, while babies fed exclusively with milk formula were seen a minimum of five hours after the last feeding. Children older than 1 year were examined fasted, at least eight hours after the last meal.

HBT was performed with the Gastrolyzer Gastro+ (Bedfont, UK). In the case of uncooperative children, the test was performed with an Ambu mask connected to a Gastrolyzer. In the other children the test was performed with the usual technique. The concentration of hydrogen in the exhaled air was measured at five points in time: before administering the lactose, and then 15, 30, 60 and 90 minutes after the intake of lactose. Hypolactasia was diagnosed if the concentration of hydrogen in the exhaled air was more than 20 parts per million above the initial value as measured 60 and 90 minutes after the intake of lactose.

Biological material – 2 ml blood samples with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid – was collected from all patients, regardless of HBT results, so as to assay the LCT polymorphisms. Each blood sample was frozen at −20℃ and remained so until the examination.

Blood samples were analysed with a DNA isolation kit (DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. To analyse the SNPs of the LCT gene, the polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism method was used with properly selected Polgen starters. The amplification was performed in the Thermal Cycler PTC-100 TM. Then, the obtained biological material was subjected to restriction enzymes: Hhal for LCT-13910C>T and Hinfl for LCT-22018G>A. Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed. LCT-13910C>T genotypes corresponded to the bands with base pair (bp) lengths CC-201, TT-177, and CT-201 and 177. LCT-22018G>A genotypes corresponded to the bands with the following lengths: AA-448 bp, GG-264 bp and 184 bp, and GA-448 bp, 264 bp, and 184 bp.

PLI was diagnosed in patients with a positive HBT result and the presence of at least one LCT polymorphism, 13910CC and/or 22018GG. SLI was observed in patients with a positive HBT result and the presence of LCT polymorphisms 13910CT or 13910TT and 22018GA or 22018AA. Genetic predisposition to hypolactasia was defined as the presence of the LCT polymorphisms 13910 CC and/or 22018 GG in patients with normal HBT results.

Statistical analysis of the obtained test results was performed with the χ2 test with Yates’s correction and with the help of the Statistica programme.

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s human research committee (the bioethics committee of the Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital Research Institute – opinion Nos. 19/2014, 27 May 2014 and 26/2017, 28 March 2017). Written consent was obtained for participation in the study from a legally authorized representative.

Results

In the entire study group, the 13910CC genotype was observed in 56 (56.6%) patients, and in 42 of them (42.4%) it was accompanied by the 22018GG genotype (Table 1). It was proved that all the patients with homozygous 22018GG also had the homozygous 13910CC, but not vice versa.

Table 1.

Prevalence and coincidence of specific LCT polymorphism genotypes 13910C>T and 22018G>A in the study group.

| LCT-13910C>T N = 99 | LCT-22018G>A N = 99 | % |

|---|---|---|

| CC 56 | GG 42 | 75 |

| AA 10 | 17.9 | |

| GA 4 | 7.1 | |

| CT 31 | GA 30 | 96.8 |

| AA 1 | 3.2 | |

| TT 12 | AA 12 | 100 |

|

| ||

| HBT + N = 35 | ||

| CC 26 | GG 23 | 88.5 |

| AA 2 | 7.7 | |

| GA 1 | 3.8 | |

| CT 7 | GA 6 | 85.7 |

| AA 1 | 14.3 | |

| TT 2 | AA 2 | 100 |

|

| ||

| HBT– N = 64 | ||

| CC 30 | GG 19 | 63.3 |

| AA 8 | 26.7 | |

| GA 3 | 10 | |

| CT 24 | GA 24 | 100 |

| TT 10 | AA 10 | 100 |

The polymorphism LCT gene (variants of gene) are bolded in order to point out the number of patients who have polymorphism. HBT−: negative hydrogen breath test result; HBT+: positive hydrogen breath test result; LCT: lactase gene.

On the basis of the HBT, hypolactasia was diagnosed in 35 (36.4%) children, of whom 26 (26.3%) were diagnosed with PLI. Among them, 26 (26.3%) had the 13910CC genotype and 23 (23.2%) had the 22018GG type of the LCT gene. SLI was diagnosed in nine (9.1%) patients. From among 64 children with a negative HBT result, 30 (30.3%) were diagnosed with a genetic predisposition to hypolactasia – the LCT 13910CC genotype was detected in 30 (30.3%) patients and 19 of them (19.8%) had the LCT 22018GG type.

Children younger than 6

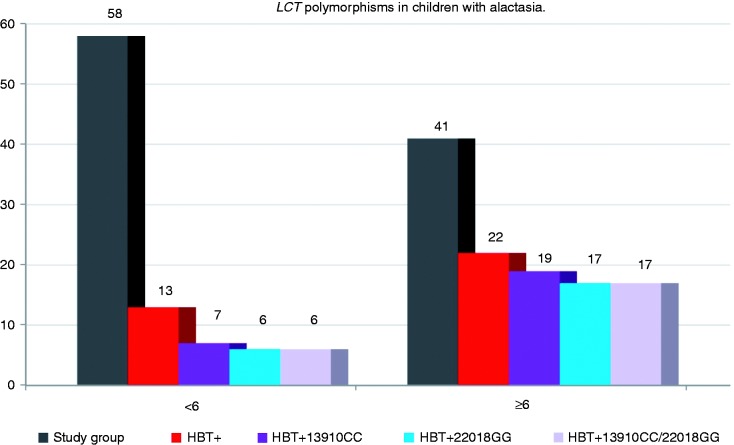

On the basis of HBT results, hypolactasia was diagnosed in 13 (22.4%) children. In this group seven (12.1%) had the LCT 13910CC and/or 22018GG genotype, and PLI was identified in these children. Six of the patients with hypolactasia (10.3%) had the LCT 13910CT or 13910TT and 22018GA or 22018AA genotypes, which pointed to the diagnosis of SLI (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Occurrence of LCT-13910CC and LCT-22018GG genotypes in patients with hypolactasia. HBT+ – patients with a positive result of the HBT. HBT+13910CC and/or 22018GG – patients with a positive HBT result and specific genotype of primary hypolactasia. HBT: hydrogen breath test; LCT: lactase gene.

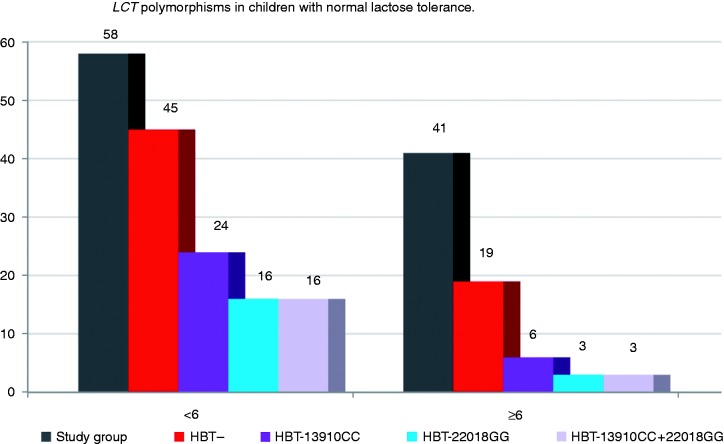

In 45 (77.6%) patients, the HBT result pointed to correct lactose tolerance. In this group, 24 (53.3%) children had the LCT 13910CC or 22018GG genotype. These patients were genetically predisposed to experience symptoms of hypolactasia in the future (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Occurrence of LCT-13910CC and LCT-22018GG genotypes in patients with normal lactose tolerance. HBT – patients with a negative result of the HBT. HBT-13910CC and/or 22018GG – patients with a negative HBT result and a genetic predisposition to hypolactasia. HBT: hydrogen breath test; LCT: lactase gene.

In this age group, no correlation was shown between the presence of the LCT 13910CC (p = 0.777) or 22018GG (p = 0.712) genotype and HBT result.

Children 6 and older

On the basis of the HBT results, hypolactasia was diagnosed in 22 (53.7%) children. In this group 19 (46.3%) had the LCT 13910CC and/or 22018GG genotype, and PLI was identified in these children. Three (7.3%) patients with hypolactasia had the LCT 13910CT or 13910TT and 22018GA or 22018AA genotypes, which is how SLI was diagnosed (Figure 1).

In 19 (46.3%) patients, the HBT result pointed to proper lactose tolerance. Among these patients, six (14.6%) had the LCT 13910CC or 22018GG genotype and a genetic predisposition to the symptoms of hypolactasia in the future (Figure 2).

It was shown that in the group of children age 6 and older, positive diagnosis of hypolactasia following HBT results correlated with the presence of LCT 13910CC (p = 0.0011) and 22018GG (p = 0.0003) genotypes (Figure 1). It was calculated that with reference to HBT results, the sensitivity and specificity of determining LCT-13910C>T is 86.4% and 68.4%, respectively, and the predictive value of the positive and negative test result is 76% and 81.2% for children in this age group.

Discussion

Previously, the evaluation of lactase activity in the biopsy from the small intestine was considered the gold standard in diagnosing hypolactasia.7,13 As HBT is more and more commonly used, this method has lost its significance because of its invasive nature. Today, some authors consider the HBT the gold standard in diagnosing hypolactasia because it is a simple, cheap, easily repeatable, noninvasive test.5 According to various sources, the sensitivity and specificity of HBT in diagnosing hypolactasia as compared with intestinal biopsy is 69% to 100% and 89% to 100%, respectively.7,13,14 It is known that there are factors that affect the progress of HBT and produce false-positive or -negative results, thus leading to a wrong diagnosis.7 Furthermore, in the case of some children, even those who are cooperative, performing the test may be difficult in practice. During our testing, the HBT was discontinued or was not even commenced in more than 10 patients because of the children’s refusal to take the lactose solution, vomiting during the test or difficulties in refraining from food and drink intake during the diagnosis. Therefore, the use of genetic testing in diagnosing hypolactasia in children would be welcome. Such tests are becoming more and more available these days.

In the presented paper, it was determined that 56.6% of the children with clinical symptoms pointing to LI had the LCT-13910CC and/or 22018GG genotype with documented relation to the incidence of PLI, whereas 26.2% of these patients had a positive HBT result and 30.3% negative. There are numerous publications on similar topics whose results differ and depend on, among other factors, the age of the patients.11,13,15,16 In a study conducted in Poland among young healthy adults aged 18–20, a total of 31.5% of the patients had the LCT-13910CC genotype, of whom 24.5% had LI detected through HBT.16 In a study conducted in a group of children aged 5–12, Alliende et al. showed that 86% of patients with a positive HBT result had the 13910CC genotype, and 28% of the patients with a negative HBT result had the 13910CC genotype.13 In our paper, genetic predisposition to hypolactasia in the whole study group was observed in 30 (30.3%) patients, similar to the result obtained by Alliende et al. In a study involving an adult population with diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome, 100% patients with hypolactasia diagnosed on the basis of HBT had 13910CC, and 96% of the patients had 22018GG, whereas in the group with normal lactose tolerance diagnosed via HBT, 17% of the patients had the 13910CC genotype and 21% had 22018GG.11 In another study conducted among adults, it was shown that genotype 13910CC was present in 88% patients with an HBT result other than normal, while it was not observed in any patient with normal lactose tolerance proved by the HBT.15

This paper shows that, for children 6 and older, there was a significant correlation between a positive HBT result and the presence of the LCT-13910C>T and LCT-22018G>A polymorphisms. In their paper from 2016, Alliende and colleagues13 showed that a genetic test based on the LCT-13910C>A polymorphism may be used as a good indicator of hypolactasia, and it corresponds to HBT results in children older than 6. The relation between the LCT-13910C>T polymorphism and hypolactasia is also well documented by other researchers and in studies conducted among adults and children.5,11,14,17,18

Previously, the LCT-22018G>A polymorphism was ascribed less significance as regards to controlling the expression of the gene that codes lactase.18 In some populations, however, it was shown that the 22018G>A polymorphism is a good indicator of PLI – even better than the 13910C>T polymorphism.19,20 This work proved that both the LCT 13910CC and 22018GG polymorphisms correlate to a positive HBT result in children 6 and older (p = 0.0011 and p = 0.0003). With reference to HBT in children older than 6, a slightly higher sensitivity of genetic testing was obtained for the LCT 13910CC genotype than for 22018GG (86.4% and 77.3%, respectively), whereas specificity was slightly higher for the LCT 22018GG genotype (68.4% and 84.2%, respectively). Positive predictive value was 76% for 13910CC and 85% for 222018GG, while negative predictive value was 81.2% for 13910CC and 76% for 22018GG.

Numerous works also prove that there is a dependence between the occurrence of specific LCT 13910C>T and 22018G>A polymorphisms.8,11,14,17 The results of this study show that in the entire study group, the genotype 13910CC was observed in 56.6% patients, whereas in 42.4% of these cases it was accompanied by genotype 22018GG. It was proved that all the patients with homozygous 22018GG also have homozygous 13910CC, but not vice versa. It seems therefore that in Poland, and maybe even in the whole of Central Europe, genetic testing based solely on the LCT-13910C>T polymorphism is reliable and makes it possible to reduce the cost of expensive testing.

So far, it is not known whether the coincidence of both homozygous LCT polymorphisms (13910CC and 22018GG) affects the early extinguishing of lactase activity and determines the intensification of clinical symptoms of hypolactasia.

Conclusions

More than half of children with clinical symptoms of LI have a genetic predisposition to hypolactasia.

In children older than 6, the result of genetic testing based on the LCT-13910C>T and 22018G>A polymorphisms may diagnose LI in patients with concomitant clinical symptoms of hypolactasia. The genetic test is also useful if the HBT is impossible to perform or its results are questionable.

In the group of children younger than 6, genetic testing was of secondary importance in diagnosing the type of hypolactasia, but such tests make it possible to detect predispositions to LI in the future.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital Research Institute Young Researcher Internal Grant (No. 2015/IV/49-MN).

Ethics approval

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s human research committee (the bioethics committee of the Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital Research Institute – opinion nos. 19/2014, 27 May 2014 and 26/2017, 28 March 2017).

Informed consent

Written consent was obtained for participation in the study from a legally authorized representative.

References

- 1.Marasz A, Czaja-Bulsa G, Brodzińska B, et al. Hypolactasia symptoms in children, teenagers, and students of schools in Szczecin. Pediatr Pol 2017; 92: 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heyman MB. Committee on Nutrition. Lactose intolerance in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics 2006; 1183: 1279–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lukito W, Malik S, Surono IS, et al. From ‘lactose intolerance’ to ‘lactose nutrition’. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2015; 24(Suppl 1): S1–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valenta R, Hochwallner H, Linhart B, et al. Food allergies: The basics. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 1120–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enko D, Rezanka E, Stolba R, et al. Lactose malabsorption testing in daily clinical practice: A critical retrospective analysis and comparison of the hydrogen/methane breath test and genetic test (C/T-13910 polymorphism) results. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2014; 2014: 464382–464382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grenov B, Briend A, Sangild PT, et al. Undernourished children and milk lactose. Food Nutr Bull 2016; 37: 85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasbarrini A, Corazza GR, Gasbarrini G, et al. Methodology and indications of H2-breath testing in gastrointestinal diseases: The Rome Consensus Conference. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30; 29(Suppl 1): 1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattar R, de Campos Mazo DF, Carrilho FJ. Lactose intolerance: Diagnosis, genetic, and clinical factors. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2012; 5: 113–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marasz A. Frequency and clinical overview of hypolactasia among children, adolescents and students of Szczecin schools [article in Polish]. Pomeranian J Life Sci 2015; 61: 207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Socha J, Ksiazyk J, Flatz G, et al. Prevalence of primary adult lactose malabsorption in Poland. Ann Hum Biol 1984; 11: 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernardes-Silva CF, Pereira AC, de Fátima Alves da Mota G, et al. Lactase persistence/non-persistence variants, C/T_13910 and G/A_22018, as a diagnostic tool for lactose intolerance in IBS patients. Clin Chim Acta 2007; 386: 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enattah NS, Sahi T, Savilahti E, et al. Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia. Nat Genet 2002; 30: 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alliende F, Vial C, Espinoza K, et al. Accuracy of a genetic test for the diagnosis of hypolactasia in Chilean children: Comparison with the breath test. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016; 63: e10–e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morales E, Azocar L, Maul X, et al. The European lactase persistence genotype determines the lactase persistence state and correlates with gastrointestinal symptoms in the Hispanic and Amerindian Chilean population: A case-control and population-based study. BMJ Open 2011; 1: e000125–e000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krawczyk M, Wolska M, Schwartz S, et al. Concordance of genetic and breath tests for lactose intolerance in a tertiary referral centre. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2008; 17: 135–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mądry E, Lisowska A, Kwiecień J, et al. Adult-type hypolactasia and lactose malabsorption in Poland. Acta Biochim Pol 2010; 57: 585–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulhões AC, Goldani HA, Oliveira FS, et al. Correlation between lactose absorption and the C/T-13910 and G/A-22018 mutations of the lactase-phlorizin hydrolase (LCT) gene in adult-type hypolactasia. Braz J Med Biol Res 2007; 40: 1441–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuchay RA, Anwar M, Thapa BR, et al. Correlation of G/A -22018 single-nucleotide polymorphism with lactase activity and its usefulness in improving the diagnosis of adult-type hypolactasia among North Indian children. Genes Nutr 2013; 8: 145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattar R, Monteiro Mdo S, Silva JM, et al. LCT-22018G>A single nucleotide polymorphism is a better predictor of adult-type hypolactasia/lactase persistence in Japanese-Brazilians than LCT-13910C>T. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010; 65: 1399–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu L, Sun H, Zhang X, et al. The –22018A allele matches the lactase persistence phenotype in northern Chinese populations. Scand J Gastroenterol 2010; 45: 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]