Abstract

With the increasing proportion of youth living with human immunodeficiency virus (YLHIV) and the aging of the perinatally infected population, there is a need for clinical services that are ‘youth friendly’ to address the multiple challenges YLHIV face in terms of engagement in care and maintenance of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). Little is known about how and where YLHIV receive their care. Further, the impact of the care structure on engagement and retention outcomes for YLHIV is ill defined. In order to better classify how YLHIV receive care in the United States, we performed a review of published literature characterizing the structure and outcomes of care for YLHIV. Several key concepts emerged: 1. The majority of YLHIV (13–24 years old) are cared for at adult sites, 2. Clinics providing care to YLHIV are varied in terms of the services offered and the types of services offered can impact outcomes, 3. YLHIV cared for in adult clinical sites have poor retention and antiretroviral treatment initiation, and 4. YLHIV cared for at adult sites had poorer retention and cART outcomes compared to YLHIV cared for at pediatric sites. There were no studies identified that specifically examined ‘youth friendly’ care for YLHIV within the context of adult clinical sites. The results of this review highlight disparities for YLHIV and the need for interventions to improve outcomes for YLHIV in the context of adult care.

Keywords: HIV, patient care, youth, adolescent, outcomes

Introduction

Despite advances in evidence-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention and treatment strategies, HIV continues to disproportionally impact vulnerable populations, particularly adolescents and young adults1. In 2013 an estimated 21% of new HIV infections in the U.S. occurred among youth aged 13–24 years, with the highest number of new infections among all age groups occurring in those 20–24 years old2. At the end of 2014 there were an estimated 40,000 adolescents and young adults 13–24 years old living with HIV in the U.S.3. While the Center for Disease Control recommends HIV testing for adolescents ages 13 and above4, it is estimated that only 40% of youth living with HIV (YLHIV) are aware of their diagnosis, and only 6% have achieved virologic suppression5.

The vast majority of YLHIV are non-perinatally HIV-infected (nPHIV) with male-to-male sexual contact risk factor and are disproportionately from communities of color3. Additionally, the CDC estimates that there are approximately 8,000 individuals greater than 13 years of age living with perinatally acquired HIV (PHIV)2. Although perinatal transmission is increasingly rare in the U.S., there is a population of PHIV youth that have survived due to advances in combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) and are aging into adulthood6,7. This group of PHIV young adults is often a highly treatment-experienced population where up to 30% are not virologically suppressed on treatment7,8. While there are unique aspects of the two groups comprising YLHIV, a common theme is that YLHIV experience significant challenges to their engagement and retention in care.

Many YLHIV have competing needs that distract from engaging in care, including unstable housing, under-employment, and co-morbid physical and mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, and/or substance use9–11. Other specific challenges include difficulty navigating the health care system and identifying clinics that are accessible, offer comprehensive services, and understand the developmental, cognitive, and psychosocial needs unique to youth9,10. Cumulatively, these barriers result in YLHIV having lower rates of linkage to care after HIV diagnosis and lower retention and adherence5,10,12–15.

Addressing these challenges requires an understanding of where and how YLHIV receive their care. In the U.S. YLHIV can be seen in a variety of adult and pediatric clinical settings by providers with varying training and expertise in caring for this population. There are likely differences in the approaches to YLHIV for providers from different training backgrounds, as seen in non-HIV states such as sickle cell, cystic fibrosis, and end stage renal disease16,17. Further, clinics can vary in terms of location (urban versus rural, community versus academic)18–20. These potential provider and clinic differences may result in different outcomes among YLHIV in different settings.

Data from the HIV Research Network (HIVRN), a consortium of high-volume clinic sites that provide care to HIV-infected children, youth, and adult patients across the U.S. and examines “real-world” HIV care utilization and outcomes, has shown that 78–91% of non-perinatally HIV-infected youth are cared for in adult clinical settings21–23. In order to optimize the care for YLHIV, first there must be a better understanding of where they are receiving their care and how the potential differences in that care may impact retention, receipt of antiretroviral therapy, and successful viral suppression.

Methods

We performed a targeted search of the literature to identify the specific kinds of clinical structures and settings where YLHIV in the U.S. receive their care and, where available, the clinical outcomes in those settings. We searched Pubmed® for English language articles published from 2005–2015. We used the terms “HIV”, “youth”, “adolescent”, “care”, and “treatment”. Our initial search resulted in more than 3,000 papers, though the large majority did not include information on the structure of care for youth in the United States. Titles and abstracts were reviewed for the themes: youth-friendly, structures of care, and outcomes to identify studies that specifically examined our questions of interest.

Results

Our search resulted in 15 studies: three descriptive studies addressing HIV provider, services and clinical environments, two studies addressing how the clinical setting affects outcomes, seven studies addressing outcomes for YLHIV of various population sizes compared to older patients, and three studies specifically addressing differences in care received at pediatric versus adult clinics. Several key themes and concepts emerged.

Descriptive studies of where YHIV receive care

Our search identified three studies that described the structural elements of clinics in which YLHIV receive care: one study focused in detail on adult clinics only and two studies focused on pediatric/adolescent clinics.

Yehia et al. sought to describe the structures of medical care delivered by clinics in the multi-site HIVRN24. A cross sectional survey was conducted of adult HIVRN clinics treating patients 18 years or older. Of the more than 13,000 patients cared for at the 11 clinics studied, those 18–30 years old comprised 9% of the total population. The study reported that 51% of the providers are attending physicians, 34% physician trainees, 11% nurse practitioners (NP), and 4% physician assistants (PA). Detail on the subspecialty training of the providers was not included. For the clinics surveyed, the median number of providers was 15 (range, 2–72). The median patient panel was 135 (range, 70–300) for attending physicians, 129 (range, 11–175) for NP, and 142 (range, 100–159) for PA. The median volume of patients was 8.5 per half-day session (range, 5–15). Additionally it was found that greater than half of clinics offered on-site case management, clinical pharmacy, psychiatry, substance abuse, and gynecologic services. These results show the variability of care settings, training, and infrastructure available to YLHIV who are cared for in adult clinical settings. The study also demonstrates that while overall a majority of YLHIV is cared for in adult settings, they comprise small proportions of the clinic population, spread over the many adult sites.

Alternatively, YLHIV comprise a large portion of those cared for in pediatric/adolescent settings. A subsequent HIVRN study sought to describe the organization of care in pediatric/adolescent HIV clinics within the HIVRN25. The six pediatric/adolescent clinics, within HIVRN, were surveyed. The study found that 97% of the providers were pediatricians, with 49% specializing in infectious disease. The median patient volume per half-day clinic session was 6 (range, 2–6) for physicians and 4 (range, 1–10) for NPs. The median age was 19 years and PHIV represented 64% of the total. Only two of the clinics surveyed offered all seven ancillary services included in the survey (case management, substance abuse counseling, clinical pharmacy, family planning, nutrition, language translation, and housing/transportation services). When compared to the aforementioned study on adult HIVRN clinics, the providers in pediatric sites have a lower median patient volume than providers in adult clinics. The patient panel per provider was not provided in the pediatric study, though the total patient population at the 6 pediatric sites was 578 compared to more than 13,000 patients cared for at the 11 adult sites. Analyzed together, these studies highlight the differences in patient volume between adult and pediatric sites.

Variety in the structure of care for YLHIV in pediatric settings was also examined by Tanner et al, who sought to identify those elements that make a clinic “youth friendly”26. In doing so, several different clinical models for youth are described. Outreach workers, nurses, and physicians at 15 Adolescent Trials Network for HIV Interventions (ATN) sites were surveyed. Six of the clinics were shared spaces that served pediatric and adolescent patients across sub-specialties, seven of the clinics served adolescent patients only, and two clinics were distinct HIV specialty clinics, which were physically separated from the other pediatric/adolescent clinics and also served adult patients. The survey highlighted the importance of the target population role, the physical environment of the clinic, and the social environment of the clinic. The study did not provide detail about clinic size or provider training/expertise so cannot be compared with the above HIVRN data in terms of those parameters.

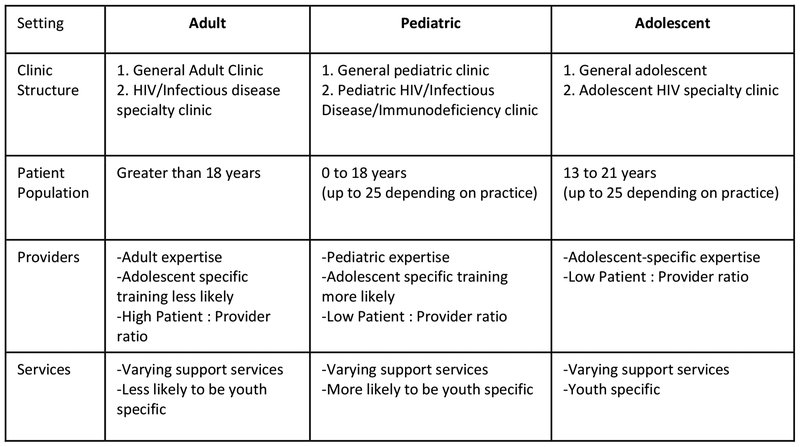

While there is limited data examining the context in which YLHIV receive care, both adult and pediatric clinic structures vary across sites and that variety of structure may impact the degree of youth friendliness (Figure 1). This is important because how and where patients receive care likely has effects on their clinical outcomes.

Figure 1:

Summary of clinical settings and structures of care for youth living with HIV

The effect of clinical structure and environment on engagement and retention in care for YLHIV

Given the limited data on the impact of clinical structure for YLHIV, evidence must be obtained through examination of how youth fare within pediatric and adult sites. The HIV care continuum describes the steps that an individual takes starting with awareness of HIV infection, and progressing to care linkage, care retention, receipt of antiretroviral therapy, and ultimately successful viral suppression27. Multiple studies, using national and local data, have shown that YLHIV have poorer outcomes over the care continuum compared to other age groups. YLHIV (ages 13–24) were are less likely to be aware of their diagnosis, be linked to care, and remain engaged in care compared to other age groups28,29. Rates of viral suppression are significantly lower among YLHIV compared to older age groups30,31. While these studies highlight the challenges for youth along the care continuum, they do not provide information about how these outcomes are affected by the clinic setting where YLHIV receive care, such as urban versus rural location, academic versus community clinic, or pediatric versus adult versus “youth friendly” clinics.

We identified two studies that describe the clinical environment and its impact on engagement and retention, one focused on adult clinics, comparing community versus academic clinics and the other looking at pediatric clinics, comparing clinics with an HIV focus versus those without an HIV focus. Our review did not identify any studies that specifically examined care of YLHIV and their outcomes in urban versus rural settings.

Schranz et al. examined how the care setting, hospital versus community-based, influences the HIV care continuum20. The study included patients >18 years cared for in 25 HIV clinics (12 hospital based, 13 community based) in Philadelphia from 2008–2011. Patients seen at hospital-based clinics and community based clinics were equally likely to complete the final three steps of the continuum, specifically retention in care, receipt of antiretroviral therapy, and ultimately successful viral suppression. Older age, higher household income, and higher median CD4 count were significantly associated with completion of the final three steps. This suggests that similar outcomes can be achieved independent of clinic setting. The percentage of patients included between 18–29 years ranged from 10% to 12% during each of the four years of the study. In 18–29 year olds there was no difference in outcomes in attendance at a community versus academic center. Of note, all other age groups performed better than the 18–29 year old age group in terms of the studied outcomes.

Philbin et al. evaluated a linkage and engagement in care initiative at 15 Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions clinic sites32. Clinics were coded based on the population served: adolescent only, shared adolescent/pediatrics, specialty HIV care only (including adolescent and adult patients), and shared pediatric/adolescent check-in but separate clinic space. They found that 70% (1,172/1,679) of patients successfully met linkage criteria and 89% (1,043/1,172) met engagement criteria. The age range was 12–24 years. The study found that clinics that served both adolescent and pediatric patients and clinics focused on HIV only were more successful in engaging youth than clinics serving adolescents only without an HIV focus. Outreach workers judged to be of higher effectiveness were associated with higher rates of engagement. This highlights that training and clinic setting, including the use of effective outreach workers, are important when it comes to engagement of youth. Though this study did not include adult clinics, it provides clinic models that may be effective in engaging youth within the context of pediatric and adolescent clinics.

Outcomes for YLHIV cared for at adult sites

Of particular interest for YLHIV, is the impact of pediatric versus adult clinical structure on care continuum outcomes. Our review found two studies evaluating outcomes for youth cared for in adult clinics.

In a single-center retrospective cohort study, the initiation and maintenance of cART in YLHIV, aged 17–24 years, were compared to HIV-infected adult controls, aged 25–40 years33. The study found inferior virologic outcomes and higher loss to follow up among YLHIV compared to matched adult controls. Fewer youth than adult subjects achieved viral suppression six months after establishing care (27/46, 59%). Viral rebound occurred at least once in 18/32 (56%) of youth and 5/38 (13%) of adults. Loss to follow up was 20/46 (44%) for youth versus 5/46 (11%) adults. In this study 15% were (7/46) PHIV. This shows that in at a single urban adult academic outpatient center, where there were no structured on-site programs specifically targeting youth, YLHIV have poorer outcomes in terms of virologic suppression compared to adult controls.

A multisite HIVRN study examining cART initiation in nPHIV youth ages 18–24 (268) versus adults greater than 25 years old (2,859) found that nPHIV youth were less likely to initiate cART when meeting eligibility compared to patients over the age of 2522. In the study, 82% of the NPHIV youth were cared for at adult clinical sites. These two studies highlight that youth cared for in adult clinical settings are less likely to be virologically suppressed and less likely to be initiated on cART compared to their adult counterparts.

Comparison of outcomes for YLHIV cared for at pediatric versus adult sites.

We identified three studies comparing outcomes for YLHIV cared for in pediatric clinic sites versus adult sites. Farmer et al. evaluated the retention in care of patients 12–24 years old at 16 HIVRN sites (12 adult, 4 pediatric) and included 9% of patients (101/1059) who were cared for at pediatric sites. Overall only 45% of YLHIV were retained at one year23. For all patients the median age at entry into care was 21 years. Forty-two percent of those cared for at adult sites were retained whereas 76% of those cared for at pediatric sites were retained. Loss to follow up was associated with care at an adult site and not being started on combination antiretroviral therapy.

A similar retrospective cohort study examined both PHIV and nPHIV youth enrolled in the HIVRN (6 pediatric and 16 adult clinics) between 2002 and 2011 and found that care at an adult site was associated with a higher likelihood of loss to follow up by the 22nd birthday (AOR, 2.71; 95% CI 1.67–4.42)34. There was no difference between PHIV and nPHIV youth in terms of loss to follow up.

Agwu et al. performed a retrospective cohort study of nPHIV youth between the ages of 12–24 who were enrolled in the HIVRN at 14 sites (3 pediatric and 11 adult)21. The study focused on the impact of clinical site on cART initiation. 278 treatment-eligible cART-naïve youth were identified, of whom 79% were followed at adult clinical sites. The study found that while there was no difference in treatment initiation for eligible youth at pediatric versus adult sites, youth receiving care at adult HIV clinical sites were 3 times more likely to discontinue their first cART regimen compared to youth cared for at pediatric sites. This direct comparison of care received by YLHIV and followed at similar sites shows that youth are more likely to stop therapy when cared for at an adult site.

Together, these studies highlight that while a majority of YLHIV are cared for in adult clinics, those who are cared for in pediatric clinics have better outcomes in terms of retention and cART usage.

Discussion

In the United States, adolescents and young adults make up an increasingly large proportion of new HIV infections. Following diagnosis, there is no standardized approach for where and how youth are directed to care. By nature of the age range of YLHIV (13–24 years), they may be seen in a variety of clinical sites. Our review found heterogeneity in the care available to YLHIV. The majority of YLHIV are cared for in adult clinical settings with varying patient volumes and availability of multidisciplinary services. Compared to pediatric clinical settings, adult clinical settings have higher patient volume and larger provider panels and may offer more comprehensive services.

Our review found that YLHIV do worse in adult care settings compared to older HIV infected patients and worse compared to YLHIV cared for in pediatric settings. Pediatric clinics likely benefit from youth-friendly settings, though we did not identify specific youth-friendly components and related outcomes to explain this difference in care. Patients fare better in pediatric clinics, however those clinics are too few in number and distribution to absorb the high numbers of newly diagnosed YLHIV and those transitioning from pediatric to adult care.

There is little data on the clinical setting where newly diagnosed YLHIV should be directed. Given the limited capacity of pediatric/adolescent care settings, data on outcomes of youth in adult care settings and interventions to enhance their outcomes are critically needed. Interventions to improve retention and adherence have been used in other key populations, such as HIV-infected people who use drugs. Interventions such as directly administered cART, contingency management, nurse derived interventions, and integrating substance abuse treatment into HIV care settings have shown short term effects in terms of adherence and virologic suppression and ongoing studies are attempting to optimize outcomes35. Similar efforts are needed to develop programs that specifically meet the needs of YLHIV in adult care.

Efforts to optimize the care for YLHIV provided in adult clinical settings will likely lead to improved outcomes for youth who initiate care in adult clinics and facilitate smooth and successful transition for YLHIV who have initiated care in pediatric sites. There has been an emphasis by the World Health Organization (WHO) and others on the importance of youth-friendly services, which are defined as services that are accessible in terms of convenience and cost, acceptable in terms of confidentiality, efficiency, and physical environment, appropriate for youth and their health challenges, effective in terms of training of providers, and equitable in terms of care and respect.36. Extending these youth friendly services to the adult clinical setting is essential.

Guidelines for the transition of adolescents with chronic medical conditions, and more specifically YLHIV, offer recommendations for success in adult care, in particular the need for a multidisciplinary approach and education of adult providers on the unique needs of youth37–39. These guidelines do not specifically address youth who are newly presenting to adult care, though these patients may similarly benefit from a youth-friendly multidisciplinary team and additional training for adult providers. Addressing this challenge will require continued inclusion of youth friendly measures within US Department of Health and Human Services clinical guidelines for adolescents with HIV and inclusion of care for youth as a quality-of-care measure for Health Resources and Services Administration/Ryan White providers.

The optimal model of care for YLHIV is unknown. Studies are needed to define the elements of youth friendly models that optimize retention and engagement outcomes, such as educating providers about youth needs, utilizing technology for communication, and improved accessibility. Models must be sustainable and be able to be implemented on a broader scale to aid those clinical settings with less experience in caring for youth.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the Johns Hopkins Center for AIDS Research under Grant 1P30AI094189; and National Institutes of Health/National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases under Grant T32AI052071.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: HIV Infection, Testing, and Risk Behaviors Among Youths — United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(47):971–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV Infection and Aids in the United States and Dependent Areas. Vol 25. 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010report/pdf/2010_HIV_Surveillence_Report_vol_22.pdf.

- 3.Center for Disease Control. HIV Surveillance in Adolescents and Young Adults.; 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-adolescents-young-adults-2014.pdf.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents, and Pregnant Women in Health-Care Settings. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanoni BC, Mayer KH. The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(3):128–135. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sohn AH, Hazra R. The changing epidemiology of the global paediatric HIV epidemic: keeping track of perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(1):18555. doi: 10.7448/ias.16.1.18555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agwu AL, Fleishman JA, Rutstein R, Korthuis PT, Gebo K. Changes in Advanced Immunosuppression and Detectable HIV Viremia Among Perinatally HIV-Infected Youth in the Multisite United States HIV Research Network. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2013;2(3):215–223. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pit008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Dyke RB, Patel K, Siberry GK, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of US children with perinatally acquired HIV infection: temporal changes in therapy between 1991 and 2009 and predictors of immunologic and virologic outcomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(2):165–173. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318215c7b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yehia BR, Kangovi S, Frank I. Patients in transition. AIDS. 2013;27(10):1529–1533. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328360104e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philbin MM, Tanner AE, Duval A, Ellen J, Kapogiannis B, Fortenberry JD. Linking HIV-positive adolescents to care in 15 different clinics across the United States: creating solutions to address structural barriers for linkage to care. AIDS Care. 2013;26(1):12–19. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.808730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez J, Bell D, Dodds S, et al. Transitioning youths into care: Linking identified HIV-infected youth at outreach sites in the community to hospital-based clinics and or community-based health centers. J Adolesc Heal. 2003;33(2 SUPPL. 2):23–30. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craw JA, Gardner LI, Marks G, et al. Brief strengths-based case management promotes entry into HIV medical care: results of the antiretroviral treatment access study-II. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(5):597–606. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181684c51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minniear TD, Gaur AH, Thridandapani A, Sinnock C, Tolley EA, Flynn PM. Delayed Entry into and Failure to Remain in HIV Care Among HIV-Infected Adolescents. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(1):99–104. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudy BJ, Murphy DA, Harris DR, Muenz L, Ellen J. Patient-related risks for nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected youth in the United States: a study of prevalence and interactions. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(3):185–194. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacDonell K, Naar-King S, Huszti H, Belzer M. Barriers to medication adherence in behaviorally and perinatally infected youth living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):86–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okumura MJ, Heisler M, Davis MM, Cabana MD, Demonner S, Kerr EA. Comfort of General Internists and General Pediatricians in Providing Care for Young Adults with Chronic Illnesses of Childhood. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1621–1627. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0716-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furth SL, Hwang W, Yang C, Neu AM, Fivush BA, Powe NR. Relation between pediatric experience and treatment recommendations for children and adolescents with kidney failure. JAMA. 2001;285(8):1027–1033. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11209173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reif S, Golin C, Smith S. Barriers to accessing HIV/AIDS care in North Carolina: Rural and urban differences. AIDS Care. 2005;17(5):558–565. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutton M, Anthony MN, Vila C, McLellan-Lemal E, Weidle PJ. HIV testing and HIV/AIDS treatment services in rural counties in 10 southern states: service provider perspectives. J Rural Heal. 2010;26(3):240–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schranz AJ, Brady KA, Momplaisir F, Metlay JP, Stephens A, Yehia BR. Comparison of HIV Outcomes for Patients Linked at Hospital Versus Community-Based Clinics. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(3):150209112614009. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agwu AL, Siberry GK, Ellen J, et al. Predictors of highly active antiretroviral therapy utilization for behaviorally HIV-1-infected youth: Impact of adult versus pediatric clinical care site. J Adolesc Heal. 2012;50(5):471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agwu AL, Fleishman JA, Korthuis PT, et al. Disparities in antiretroviral treatment: a comparison of behaviorally HIV-infected youth and adults in the HIV Research Network. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(1):100–107. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822327df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farmer C, Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, et al. Factors Associated With Retention Among Non-Perinatally HIV-Infected Youth in the HIV Research Network. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2014:1–8. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yehia BR, Gebo KA, Hicks PB, et al. Structures of care in the clinics of the HIV Research Network. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(12):1007–1013. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yehia BR, Agwu AL, Schranz A, et al. Conformity of pediatric/adolescent HIV clinics to the patient-centered medical home care model. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(5):272–279. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanner AE, Philbin MM, Duval A, et al. “Youth friendly” clinics: Considerations for linking and engaging HIV-infected adolescents into care. Aids Care-Psychological Socio-Medical Asp Aids/Hiv. 2014;26(2):199–205. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.808800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall HI, Gray KM, Tang T, Li J, Shouse L, Mermin J. Retention in Care of Adults and Adolescents Living With HIV in 13 US Areas. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(1):77–82. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318249fe90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, et al. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(14):1337–1344. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muthulingam D, Chin J, Hsu L, Scheer S, Schwarcz S. Disparities in engagement in care and viral suppression among persons with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(1):112–119. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182894555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dombrowski JC, Kitahata MM, Van Rompaey SE et al. High levels of antiretroviral use and viral suppression among persons in HIV care in the United States, 2010. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(3):299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philbin MM, Tanner AE, DuVal A, et al. Factors Affecting Linkage to Care and Engagement in Care for Newly Diagnosed HIV-Positive Adolescents Within Fifteen Adolescent Medicine Clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2013:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0650-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryscavage PA, Anderson EJ, Sutton SH, Reddy S, Taiwo B. Clinical Outcomes of Adolescents and Young Adults in Adult HIV Care. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(2):1. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d7564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agwu AL, Sc M, Lee L, et al. Aging and Loss to Follow-up Among Youth Living With Human Immunode fi ciency Virus in the HIV Research Network. J Adolesc Heal. 2015;56(3):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Binford MC, Kahana SY, Altice FL. A systematic review of antiretroviral adherence interventions for HIV-infected people who use drugs. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9(4):287–312. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.WHO. Making Health Services Adolescent Friendly; 2012. doi:ISBN9789241503594. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooley WC, Sagerman PJ. Supporting the Health Care Transition From Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):182–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. Transitioning HIV-Infected Adolescents into Adult Care; 2011. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf.

- 39.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services.; 2016. doi: 10.1310/4R1B-8F60-B57H-0ECN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]