Abstract

Extracellular glutamate accumulation following cerebral ischemia leads to overactivation of glutamate receptors, thereby resulting in intracellular Ca2+ overload and excitotoxic neuronal injury. Multiple attempts have been made to counteract such effects by reducing glutamate receptor function, but none have been successful. In this minireview, we present the available evidence regarding the role of all types of ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebral ischemia and propose phased treatment strategies based on glutamate receptors in both the acute and post-acute phases of cerebral ischemia, which may help realize the clinical application of glutamate receptor antagonists.

Keywords: cerebral ischemia, excitotoxicity, phased treatment strategies, glutamate receptors, glutamate receptor antagonist

Background

Following cerebral ischemia, rapid glutamate release combined with deficiency or reversal in glutamate uptake causes extracellular glutamate accumulation. Excessive glutamate overactivates glutamate receptors, leading to intracellular Ca2+ overload and excitotoxic neuronal injury. In consideration of the association between cell death and glutamate excitotoxicity in stroke, numerous attempts have been made to prevent neuronal damage by reducing glutamate receptor function. Unfortunately, attempts to use drugs of this type to treat stroke patients have failed, owing to either lack of efficacy or presence of side effects. In this review, the roles of all types of ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs and mGluRs) in cerebral ischemia have been discussed (Table 1), followed by an elaboration of our views on glutamate receptor-based treatment strategies for cerebral ischemia. Finally, phased therapeutics strategies proposed here may significantly improve cerebral ischemia treatment.

Table 1.

The roles of different glutamate receptors in cerebral ischemia.

| Receptor types | Main effects | Typical references | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iGluRs | NMDARs | GluN2A | Not determined | Liu et al. (2007), von Engelhardt et al. (2007) and Zhou et al. (2013) |

| GluN2B | Pro-death | Liu et al. (2007), von Engelhardt et al. (2007) and Zhou et al. (2013) | ||

| GluN2C | Not determined | Chung et al. (2016), Holmes et al. (2018) and Doyle et al. (2018) | ||

| GluN2D | Pro-death | Bai et al. (2013) and Doyle et al. (2018) | ||

| GluN3A | Pro-survival | Nakanishi et al. (2009), Lee et al. (2015) and Wang et al. (2013) | ||

| GluN3B | No obvious effect | Wang et al. (2013) | ||

| AMPARs | GluA2-containing AMPARs | Not reported | ||

| GluA2-lacking AMPARs | Pro-death | Gorter et al. (1997), Liu et al. (2004) and Liu et al. (2006) | ||

| KARs | GluK1 | Pro-survival | Xu et al. (2008) and Lv et al. (2012) | |

| GluK2 | Pro-death | Pei et al. (2005) and Pei et al. (2006) | ||

| GluK3 | Not reported | |||

| GluK4 | Pro-death | Lowry et al. (2013) | ||

| GluK5 | Not reported | |||

| mGluRs | Group I | mGluR1 | Pro-death | Xu et al. (2007) |

| mGluR5 | Not determined | Bao et al. (2001), Szydlowska et al. (2007), Takagi et al. (2012) and Li et al. (2013) | ||

| Group II | mGluR2 | Pro-death | Corti et al. (2007), Motolese et al. (2015) and Mastroiacovo et al. (2017) | |

| mGluR3 | Pro-survival | Corti et al. (2007) | ||

| Group III | mGluR4 | Pro-survival | Moyanova et al. (2011) | |

| mGluR6 | Not reported | |||

| mGluR7 | Pro-survival | Domin et al. (2015) | ||

| mGluR8 | Not reported |

Roles of iGluRs in Cerebral Ischemia

iGluRs consist of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate receptors (AMPARs), and kainate receptors (KARs). The overactivation of iGluRs triggered by excessive glutamate release plays a key role in ischemia-induced neuronal damage by enhancing intracellular calcium levels (Amantea and Bagetta, 2017).

NMDARs

NMDARs, a type of ligand-gated and Ca2+-permeable ion channel, are widely expressed in the brain and play a key role in numerous physiological and pathophysiological processes. They are formed by combining different subunits (GluN1, GluN2A–D, and GluN3A–B) into tetrameric complexes (Hansen et al., 2018). Available evidence suggests that different types of NMDARs play different roles in cerebral ischemia.

GluN1 Subunit

Because GluN1 is the obligate subunit of NMDARs, the function of GluN1 is in line with that of NMDARs and the direct inhibition of GluN1 has neuroprotective effects. Notable compounds related to GluN1 are glycine-binding site antagonists, such as gavestinel and licostinel, which showed strong neuroprotective effects against ischemic neuronal damage in vivo (Lai et al., 2014). Besides the glycine-binding site, intervention on other domains may have neuroprotective effects. Macrez reported that a polyclonal antibody against amino acid sequences 19–371, inhibiting the interaction of tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) with GluN1, prevented the proexcitotoxic effect of tPA and extended the therapeutic window of thrombolysis (Macrez et al., 2011).

GluN2A-Containing Receptors

Although the role of GluN2A-containing receptors in cerebral ischemia has been extensively studied, it remains a controversial issue. Some researchers believe that activation of GluN2A-containing receptors is beneficial. The evidence consistent with this view is that application of an antagonist of GluN2A-containing NMDARs, NVP-AAM077, could exacerbate NMDA- or DL-threo-betahydroxyaspartate-induced excitotoxicity (Liu et al., 2007; Choo et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2012), enhance oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD)-induced neuronal apoptosis (Liu et al., 2007), and increase ischemic damage after transient focal or global ischemia. However, others have a contrasting view. It has been reported that knockdown of GluN2A attenuated NMDA- or middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO)-induced neuronal damage (Morikawa et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2013). Additionally, antagonizing GluN2A-containing receptors with NVP-AAM077 or Zn2+ reduced NMDA-induced excitotoxicity in older (≥21 days in vitro) cortical or hippocampal culture (von Engelhardt et al., 2007; Stanika et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2013). Enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of GluN2A may be involved in the excitotoxic process (Yan et al., 2012). Among all the tyrosine kinases, cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) plays a key role in GluN2A phosphorylation, and perturbing interactions between Cdk5 and GluN2A abolished GluN2A phosphorylation and protected CA1 pyramidal neurons from ischemic insult (Wang et al., 2003). In view of the GluN2A signaling-pathway characteristics, we consider that GluN2A may play different roles at different times in cerebral ischemia, that is inducing neuronal death in the acute stage and promoting neuronal survival thereafter (Sun et al., 2018).

GluN2B-Containing Receptors

Overactivation of GluN2B-containing receptors is an important contributor to ischemic neuronal death (Sun et al., 2015). There is ample evidence that selective GluN2B antagonists, such as ifenprodil, CP-101, 606, Ro 25–6981, and Co 101244, prevented NMDA-mediated toxicity (Liu et al., 2007; von Engelhardt et al., 2007; Stanika et al., 2009; Choo et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2013). Moreover, molecular knockdown of GluN2B could attenuate NMDA-induced neuronal death in cultured cortical neurons (Liu et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2013). It has also been reported that ifenprodil reduced 4-vessel occlusion-triggered ischemic cell death (Chen et al., 2008). The significant pro-death effect of GluN2B can be largely attributed to its distinctive C-terminal domains (Martel et al., 2012).

Phosphorylation of GluN2B after cerebral ischemia may enhance its function and aggravate ischemic brain injury (Sun et al., 2016). After recruited to GluN2B C-terminal, CaMKIIα phosphorylated GluN2B at Ser1303 and up-regulated GluN2B function (Ahmed et al., 2017). Tat-CN21 could significantly reduce ischemic brain damage via inhibiting CaMKII binding to GluN2B (Vest et al., 2010; Ahmed et al., 2017). Thus, selectively inhibiting the phosphorylation of GluN2B may be a potential strategy for ischemia treatment.

Excessive activation of GluN2B-containing receptors could result in the activation of calpain, subsequently lead to the truncation of GluN2A and GluN2B in the C-terminal, and finally uncoupling NMDARs with downstream signaling proteins (Gascón et al., 2008). Strong blockage of GluN2B under this condition, which affects the normal signal transduction of NMDARs, may be detrimental.

GluN2C-Containing Receptors

It is not clear whether the activation of GluN2C-containing receptors is harmful to ischemic neurons. An early study showed that focal cerebral infarctions in GluN2C-knockout mice were significantly less extensive than those in wildtype mice (Kadotani et al., 1998). A recent study found that although GluN2C-knockout mice displayed similar infarct volumes compared to the wildtype mice, they showed decreased cerebral edema and enhanced neurological recovery (Holmes et al., 2018). Doyle et al. (2018) found that ischemic conditions could trigger the activation of GluN2C/2D-containing NMDARs in the oligodendrocytes under myelin sheath following the release of axonal vesicular glutamate into the peri-axonal space, and this process contributes to myelin damage. These results indicated the neurotoxic effect of GluN2C in cerebral ischemia. However, Chen and Roche (2009) reported that overexpression of GluN2C protected cerebellar granule cells from NMDA-induced toxicity. They also found that GluN2C-knockout mice exhibited greater neuronal death in the CA1 area of the hippocampus and reduced spatial working memory compared to the wildtype mice (Chung et al., 2016).

GluN2D-Containing Receptors

GluN2D-knockout mice showed reduced neuronal damage in NMDA-induced retinal ganglion cell death (Bai et al., 2013). The underlying mechanism may be related to myelin damage (Doyle et al., 2018).

GluN3A-Containing Receptors

Several studies have reported the neuroprotective effect of GluN3A. GluN3A knockout could increase cerebrocortical neuronal damage following NMDA application in vitro, NMDA-induced retinal ganglion cell death in vivo, or cortex damage in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia (Nakanishi et al., 2009). Subsequent experiments indicated that GluN3A knockout significantly increased the infarction volume in adult mice with ischemic stroke and hindered the sensorimotor functional recovery after stroke (Lee et al., 2015). It was also reported that overexpression of the GluN3A subunit in rat hippocampal neurons protected against OGD-induced toxicity (Wang et al., 2013).

GluN3B-Containing Receptors

The expression of GluN3B showed no visible changes following brain ischemia in vivo and OGD in vitro (Wang et al., 2013). Therefore, GluN3B might not be involved in the ischemic processes.

Expression of NMDAR Subunits Following Cerebral Ischemia

Cerebral ischemia could induce significant decreases in hippocampal GluN2A and GluN2B as early as 30 min, which may continue for several days (Zhang et al., 1997; Hsu et al., 1998; Dos-Anjos et al., 2009a,b; Liu et al., 2010; Fernandes et al., 2014; Han et al., 2016). While, the expression of GluN2C and GluN3A in the hippocampus was significantly increased following ischemia (Fernandes et al., 2014; Chung et al., 2016). Because the GluN2B/GluN2A ratio increases after ischemia, which may be detrimental to cell survival, upregulation of GluN2A expression may be helpful to ischemia treatment (Dos-Anjos et al., 2009b; Han et al., 2016).

NMDARs in Astrocytes

The NMDAR subunits expressed in astrocytes include GluN1, GluN2A, GluN2B, GluN2C, and GluN3A (Dzamba et al., 2015). However, the role of the NMDAR in astrocytes remains unclear. Alsaad et al. (2019) indicated that GluN2C may have a specific role in regulating glutamate release from astrocytes in response to glutamate spillover. Thus, the study of the roles of NMDARs on L-glutamate release in astrocytes may help to develop new therapeutic strategies.

Metabotropic NMDAR Signaling

Metabotropic NMDAR signaling, which is dependent on the allosteric movement of the C-terminal domain of NMDAR subunits (Dore et al., 2015), could mediate neuronal damage in the early stage of ischemia and disruption of this signaling in vitro or in vivo by administration of an interfering peptide was neuroprotective (Weilinger et al., 2016). Besides pro-death signaling, some metabotropic signaling mediated by NMDARs may be beneficial (Hu et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2017).

AMPARs

Most fast excitatory transmission in the brain is mediated by AMPARs. They are composed of four different subunits (GluA1–4), and are homo- or hetero-tetrameric ion channels (Diering and Huganir, 2018). Due to the poor permeability of the GluA2 subunit to Ca2+, AMPAR Ca2+ conductance is dependent on the presence of GluA2. GluA2-containing AMPARs have low Ca2+ conductance, whereas GluA2-lacking AMPARs are Ca2+ permeable (Kwak and Weiss, 2006), and the latter are considered harmful. Detrimentally, cerebral ischemia could result in increased surface expression of GluA2-lacking AMPARs (Gorter et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2004, 2006). Many experiments have proven the neuroprotective effect of AMPAR antagonists such as perampanel (Nakajima et al., 2018), PNQX (Montero et al., 2007), EGIS-8332 (Matucz et al., 2006), GYKI 53405 (Matucz et al., 2006), and ZK 187638 (Elger et al., 2006) on ischemic injury. It should be emphasized that preventing the upregulation of GluA2-lacking AMPARs is an alternative treatment strategy. An interfering peptide with this effect could protect against neuronal damage induced by OGD (Wang et al., 2012) or transient MCAO (Zhai et al., 2013).

KARs

Similar to NMDARs and AMPARs, KARs are tetramers assembled from a number of subunits (GluK1–5; Lerma and Marques, 2013). The GluK1–GluK3 subunits or GluK1–GluK3 combined with GluK4 or GluK5 subunits form functional homomeric or heteromeric receptors (Crepél and Mulle, 2015). Among all the KAR subunits, GluK2 might be a major contributor to ischemia-induced neuronal death. It was originally reported that administration of GluK2 antisense oligodeoxynucleotides once per day for 3 days before cerebral ischemia significantly decreased neuronal degeneration (Pei et al., 2005). Tat-GluK2-9c, a fusion peptide containing the Tat peptide and C-terminus peptide of GluK2, could interfere with the interaction of GluK2 with PSD-95 and suppress the formation of the GluK2-PSD-95-MLK3 triplicate complex, thereby preventing brain injury caused by cerebral ischemia (Pei et al., 2006). Besides GluK2, GluK4 also promotes the neuronal damage process. GluK4-knockout mice showed significant neuroprotection in the CA3 region of the hippocampus following intrahippocampal injection of kainate and widespread neuroprotection throughout the hippocampus following hypoxia-ischemia (Lowry et al., 2013). Contrary to the roles of GluK2 and GluK4, GluK1 may be a neuroprotective factor. ATPA, a selective GluK1 agonist, had a neuroprotective effect against ischemia/reperfusion-induced neuronal cell death, while the selective GluK1 antagonist, NS3763, or GluK1 antisense oligodeoxynucleotides had opposite effects (Xu et al., 2008; Lv et al., 2012).

Roles of mGluRs in Cerebral Ischemia

mGluRs consist of eight receptor subunits (mGluR1–8), which are divided into three groups according to structural homology, pharmacologic profile, and signaling transduction pathways, namely group I (mGluR1 and mGluR5), group II (mGluR2 and mGluR3), and group III (mGluR4 and mGluR6–8). Compared with iGluRs, mGluRs play a more complicated role in cerebral ischemia.

Group I mGluRs

mGluR1

Following cerebral ischemia, the activation of mGluR1 receptors may be harmful to neurons. Although knockout of the mGluR1 gene in mice could not limit the extent of ischemic brain injury (Ferraguti et al., 1997), a great number of studies have shown the neuroprotective effects of selective mGluR1 antagonists, such as LY367385 (Bruno et al., 1999; Murotomi et al., 2008; Li et al., 2013), YM-202074 (Kohara et al., 2008), EMQMCM (Szydlowska et al., 2007), CBPG (Pellegrini-Giampietro et al., 1999a,b; Cozzi et al., 2002; Meli et al., 2002), 3-MATIDA (Cozzi et al., 2002; Moroni et al., 2002), BAY 36-7620 (De Vry et al., 2001), and AIDA (Pellegrini-Giampietro et al., 1999a,b; Meli et al., 2002), on ischemic damage in vivo. One typical pro-death mechanism may be calpain-mediated mGluR1a truncation in the C-terminal domain (Xu et al., 2007). The truncated mGluR1a, which loses the ability to activate the neuroprotective PI3K-Akt signaling pathways and maintains the ability to increase the cytosolic calcium level, is an important contributor to excitotoxicity (Xu et al., 2007). The Tat-mGluR1 peptide consisting of the transduction domain of the Tat protein and the mGluR1a sequence spanning the calpain-cleavage site could protect mGluR1a from truncation and has exhibited neuroprotection against excitotoxicity both in vitro and in vivo (Xu et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2009).

mGluR5

Unlike mGluR1, the role of mGluR5 in ischemia remains to be determined. Several articles have reported the neuroprotective effects of selective mGluR5 receptor antagonists, MPEP or MTEP, in transient global (Takagi et al., 2010, 2012) or focal cerebral ischemia (Bao et al., 2001; Szydlowska et al., 2007; Li et al., 2013). Other evidence indicated that CHPG, a selective mGluR5 receptor agonist, could protect cortical neurons and BV2 cells against in vitro traumatic injury (Chen et al., 2012) and OGD-induced cytotoxicity (Ye et al., 2017), respectively; it has shown protective effects against traumatic brain injury (Chen et al., 2012) or focal cerebral ischemia damage (Bao et al., 2001) in vivo. Moreover, mGluR5 has been shown to protect astrocytes from ischemic damage in the postnatal central nervous system (CNS) white matter (Vanzulli and Butt, 2015). However, other studies have found that antisense oligodeoxynucleotide directed to mGluR5, MPEP or MTEP, showed no neuroprotective effects against post-traumatic neuronal injury (Mukhin et al., 1996) in vitro, OGD damage (Meli et al., 2002), or hypoxia-ischemia injury in neonatal rats (Makarewicz et al., 2015). Moreover, the use of CHPG did not improve the functional and histological outcomes in a rat model of endothelin-1-induced focal ischemia (Riek-Burchardt et al., 2007).

Group II mGluRs

mGluR2 and mGluR3 may mediate pro-death and pro-survival effects, respectively, in cerebral ischemia. Important evidence to this end was provided by a study showing that the neuroprotective effect of LY379268, a group II mGluR agonist, against NMDA-induced neuronal damage was lost in mice lacking mGluR3 receptors, while mGluR2 knockout enhanced the neuroprotective activity of LY379268 (Corti et al., 2007). Other experiments have shown that post-ischemic oral treatment with ADX92639, a selective negative allosteric modulator of the mGluR2 receptor, was highly protective against a 4-vessel occlusion model of transient global ischemia in rats, while the administration of the mGluR2 receptor agonist, LY487379, aggravated ischemia-induced neuronal damage in both the CA1 and CA3 regions (Motolese et al., 2015). Moreover, genetic deletion of mGluR2 receptors could improve the short-term outcome of cerebral transient focal ischemia (Mastroiacovo et al., 2017).

Group III mGluRs

The activation of group III mGluRs may be beneficial to ischemic neurons. Although early research indicated that (R, S)-4-phosphonophenylglycine, a selective group III mGluR agonist, had no significant influence on neuronal damage in both focal and global cerebral ischemia models (Henrich-Noack et al., 2000), group III mGluR agonist, ACPT-I, showed neuroprotective effects against MCAO/reperfusion in both normotensive (Domin et al., 2014) and spontaneously hypertensive (Domin et al., 2018) rats. It was also reported that the absence of mGluR4 receptors and PHCCC, a positive allosteric modulator of mGluR4 receptors, could enhance and reduce brain damage, respectively, induced by permanent MCAO or endothelin-1-induced transient focal ischemia (Moyanova et al., 2011). Additionally, AMN082, an allosteric agonist of mGluR7, protected neurons against OGD- or kainate-induced damage (Domin et al., 2015).

Phased Treatment Strategies for Cerebral Ischemia Based on Glutamate Receptors

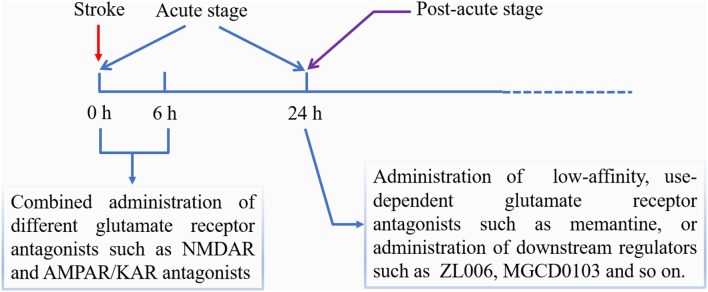

The diagram of phased treatment strategies for cerebral ischemia based on glutamate receptors is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Phased treatment strategies for cerebral ischemia based on glutamate receptors.

Treatment Strategies in the Acute Phase

Because several types of glutamate receptors contribute to ischemic damage in the acute phase, we can adopt a “hitting hard” strategy through the combined use of different antagonists in order to improve the curative effect. Several articles have reported that combined use of NMDAR and AMPAR antagonists, such as MK-801 and NBQX (or CNQX), could achieve additive protective effect in both in vitro and in vivo ischemia models (Mosinger et al., 1991; Lippert et al., 1994; Virgili et al., 1995). However, this combination strategy may have a greater impact on physiological function, making it difficult to use in the clinic (McManigle et al., 1994). Therefore, we consider that new antagonists having the characteristics of short-acting and ischemic tissue-targeting should be developed in order to minimize the adverse reactions. In addition, combined use of iGluR and mGluR antagonist such as MK-801 and AP-3, showed a synergistic effect in the reduction of cell death induced by OGD (Zagrean et al., 2014).

Treatment Strategies in the Post-acute Phase

In the post-acute phase, the major role of glutamate receptors may be promoting neuron survival. Under this condition, we can adopt a “precision treatment” strategy by selectively blocking the pro-death signaling or enhancing the pro-survival signaling. One method is to use low-affinity, use-dependent glutamate receptor antagonists, which do not interfere with the receptors’ physiological function. Consistent with this view is that delayed treatment with MK-801 did not show beneficial effects (Zhou et al., 2015), while, post-acute delivery of memantine promoted post-ischemic neurological recovery, peri-infarct tissue remodeling, and contralesional brain plasticity (Wang et al., 2017). Another method is to administer selective inhibitors of downstream pro-death signaling molecules. For instance, administration of histone deacetylase 2 inhibitors starting 5–7 days after stroke promoted recovery of motor function (Lin et al., 2017). Moreover, animals treated with Tat-HA-NR2B9c or ZL006 starting at 4 days after ischemia showed improved functional recovery (Zhou et al., 2015). In addition, considering the pro-survival effects of GluN2A-containing receptors and Group III mGluRs after cerebral ischemia, the agonists of these kinds of receptors may become alternative therapeutic drugs in the post-acute phase.

Conclusions

Low efficacy or serious side effects limit the clinical application of glutamate receptor antagonists, which indicates the need to modify the existing treatment strategies. The new strategies proposed in this article may help realize the clinical application of glutamate receptor antagonists.

Author Contributions

ZG and LW proposed the topic of the article, participated in literature search and revised the manuscript. YS participated in literature search and manuscript writing. XF, YD, ML and JY participated in manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the State Key Laboratory Breeding Base—Hebei Key Laboratory of Molecular Chemistry for Drug and Hebei Research Center of Pharmaceutical and Chemical Engineering.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number NSFC 81771265); the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (grant number H2017208063).

References

- Ahmed M. E., Dong Y., Lu Y., Tucker D., Wang R., Zhang Q. (2017). Beneficial effects of a CaMKIIα inhibitor TatCN21 peptide in global cerebral ischemia. J. Mol. Neurosci. 61, 42–51. 10.1007/s12031-016-0830-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaad H. A., DeKorver N. W., Mao Z., Dravid S. M., Arikkath J., Monaghan D. T. (2019). In the telencephalon, GluN2C NMDA receptor subunit mRNA is predominately expressed in glial cells and GluN2D mRNA in interneurons. Neurochem. Res. 44, 61–77. 10.1007/s11064-018-2526-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amantea D., Bagetta G. (2017). Excitatory and inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitters in stroke: from neurotoxicity to ischemic tolerance. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 35, 111–119. 10.1016/j.coph.2017.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai N., Aida T., Yanagisawa M., Katou S., Sakimura K., Mishina M., et al. (2013). NMDA receptor subunits have different roles in NMDA-induced neurotoxicity in the retina. Mol. Brain 6:34. 10.1186/1756-6606-6-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao W. L., Williams A. J., Faden A. I., Tortella F. C. (2001). Selective mGluR5 receptor antagonist or agonist provides neuroprotection in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 922, 173–179. 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03062-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno V., Battaglia G., Kingston A., O’Neill M. J., Catania M. V., Di Grezia R., et al. (1999). Neuroprotective activity of the potent and selective mGlu1a metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist, (+)-2-methyl-4 carboxyphenylglycine (LY367385): comparison with LY357366, a broader spectrum antagonist with equal affinity for mGlu1a and mGlu5 receptors. Neuropharmacology 38, 199–207. 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00159-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Hu R., Liao H., Zhang Y., Lei R., Zhang Z., et al. (2017). A non-ionotropic activity of NMDA receptors contributes to glycine-induced neuroprotection in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Sci. Rep. 7:3575. 10.1038/s41598-017-03909-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Lu T. J., Chen X. J., Zhou Y., Chen Q., Feng X. Y., et al. (2008). Differential roles of NMDA receptor subtypes in ischemic neuronal cell death and ischemic tolerance. Stroke 39, 3042–3048. 10.1161/strokeaha.108.521898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. S., Roche K. W. (2009). Growth factor-dependent trafficking of cerebellar NMDA receptors via protein kinase B/Akt phosphorylation of NR2C. Neuron 62, 471–478. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Zhang L., Qu Y., Huo K., Jiang X., Fei Z. (2012). The selective mGluR5 agonist CHPG protects against traumatic brain injury in vitro and in vivo via ERK and Akt pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 29, 630–636. 10.3892/ijmm.2011.870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo A. M., Geddes-Klein D. M., Hockenberry A., Scarsella D., Mesfin M. N., Singh P., et al. (2012). NR2A and NR2B subunits differentially mediate MAP kinase signaling and mitochondrial morphology following excitotoxic insult. Neurochem. Int. 60, 506–516. 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C., Marson J. D., Zhang Q. G., Kim J., Wu W. H., Brann D. W., et al. (2016). Neuroprotection mediated through GluN2C-containing N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors following ischemia. Sci. Rep. 6:37033. 10.1038/srep37033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti C., Battaglia G., Molinaro G., Riozzi B., Pittaluga A., Corsi M., et al. (2007). The use of knock-out mice unravels distinct roles for mGlu2 and mGlu3 metabotropic glutamate receptors in mechanisms of neurodegeneration/neuroprotection. J. Neurosci. 27, 8297–8308. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1889-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzi A., Meli E., Carla V., Pellicciari R., Moroni F., Pellegrini-Giampietro D. E. (2002). Metabotropic glutamate 1 (mGlu1) receptor antagonists enhance GABAergic neurotransmission: a mechanism for the attenuation of post-ischemic injury and epileptiform activity? Neuropharmacology 43, 119–130. 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00080-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepél V., Mulle C. (2015). Physiopathology of kainate receptors in epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 20, 83–88. 10.1016/j.coph.2014.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vry J., Horváth E., Schreiber R. (2001). Neuroprotective and behavioral effects of the selective metabotropic glutamate mGlu1 receptor antagonist BAY 36–7620. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 428, 203–214. 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01296-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diering G. H., Huganir R. L. (2018). The AMPA receptor code of synaptic plasticity. Neuron 100, 314–329. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domin H., Gołembiowska K., Jantas D., Kamińska K., Zięba B., Smiałowska M. (2014). Group III mGlu receptor agonist, ACPT-I, exerts potential neuroprotective effects in vitro and in vivo. Neurotox. Res. 26, 99–113. 10.1007/s12640-013-9455-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domin H., Jantas D., Śmiałowska M. (2015). Neuroprotective effects of the allosteric agonist of metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 AMN082 on oxygen-glucose deprivation- and kainate-induced neuronal cell death. Neurochem. Int. 88, 110–123. 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domin H., Przykaza Ł., Kozniewska E., Boguszewski P. M., Śmiałowska M. (2018). Neuroprotective effect of the group III mGlu receptor agonist ACPT-I after ischemic stroke in rats with essential hypertension. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 84, 93–101. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore K., Aow J., Malinow R. (2015). Agonist binding to the NMDA receptor drives movement of its cytoplasmic domain without ion flow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 112, 14705–14710. 10.1073/pnas.1520023112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos-Anjos S., Martínez-Villayandre B., Montori S., Pérez-García C. C., Fernández-Lopez A. (2009a). Early modifications in N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit mRNA levels in an oxygen and glucose deprivation model using rat hippocampal brain slices. Neuroscience 164, 1119–1126. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos-Anjos S., Martínez-Villayandre B., Montori S., Regueiro-Purriños M. M., Gonzalo-Orden J. M., Fernández-López A. (2009b). Transient global ischemia in rat brain promotes different NMDA receptor regulation depending on the brain structure studied. Neurochem. Int. 54, 180–185. 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle S., Hansen D. B., Vella J., Bond P., Harper G., Zammit C., et al. (2018). Vesicular glutamate release from central axons contributes to myelin damage. Nat. Commun. 9:1032. 10.1038/s41467-018-03427-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzamba D., Honsa P., Valny M., Kriska J., Valihrach L., Novosadova V., et al. (2015). Quantitative analysis of glutamate receptors in glial cells from the cortex of GFAP/EGFP mice following ischemic injury: focus on NMDA receptors. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 35, 1187–1202. 10.1007/s10571-015-0212-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elger B., Gieseler M., Schmuecker O., Schumann I., Seltz A., Huth A. (2006). Extended therapeutic time window after focal cerebral ischemia by non-competitive inhibition of AMPA receptors. Brain Res. 1085, 189–194. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J., Vieira M., Carreto L., Santos M. A., Duarte C. B., Carvalho A. L., et al. (2014). in vitro ischemia triggers a transcriptional response to down-regulate synaptic proteins in hippocampal neurons. PLoS One 9:e99958. 10.1371/journal.pone.0099958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraguti F., Pietra C., Valerio E., Corti C., Chiamulera C., Conquet F. (1997). Evidence against a permissive role of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 in acute excitotoxicity. Neuroscience 79, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascón S., Sobrado M., Roda J. M., Rodríguez-Peña A., Díaz-Guerra M. (2008). Excitotoxicity and focal cerebral ischemia induce truncation of the NR2A and NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor and cleavage of the scaffolding protein PSD-95. Mol. Psychiatry 13, 99–114. 10.1038/sj.mp.4002017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter J. A., Petrozzino J. J., Aronica E. M., Rosenbaum D. M., Opitz T., Bennett M. V., et al. (1997). Global ischemia induces downregulation of Glur2 mRNA and increases AMPA receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx in hippocampal CA1 neurons of gerbil. J. Neurosci. 17, 6179–6188. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06179.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X. J., Shi Z. S., Xia L. X., Zhu L. H., Zeng L., Nie J. H., et al. (2016). Changes in synaptic plasticity and expression of glutamate receptor subunits in the CA1 and CA3 areas of the hippocampus after transient global ischemia. Neuroscience 327, 64–78. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K. B., Yi F., Perszyk R. E., Furukawa H., Wollmuth L. P., Gibb A. J., et al. (2018). Structure, function and allosteric modulation of NMDA receptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 150, 1081–1105. 10.1085/jgp.201812032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich-Noack P., Flor P. J., Sabelhaus C. F., Prass K., Dirnagl U., Gasparini F., et al. (2000). Distinct influence of the group III metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist (R,S)-4-phosphonophenylglycine [(R,S)-PPG] on different forms of neuronal damage. Neuropharmacology 39, 911–917. 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00256-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A., Zhou N., Donahue D. L., Balsara R., Castellino F. J. (2018). A deficiency of the GluN2C subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor is neuroprotective in a mouse model of ischemic stroke. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 495, 136–144. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.10.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu J. C., Zhang Y., Takagi N., Gurd J. W., Wallace M. C., Zhang L., et al. (1998). Decreased expression and functionality of NMDA receptor complexes persist in the CA1, but not in the dentate gyrus after transient cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 18, 768–775. 10.1097/00004647-199807000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R., Chen J., Lujan B., Lei R., Zhang M., Wang Z., et al. (2016). Glycine triggers a non-ionotropic activity of GluN2A-containing NMDA receptors to confer neuroprotection. Sci. Rep. 6:34459. 10.1038/srep34459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadotani H., Namura S., Katsuura G., Terashima T., Kikuchi H. (1998). Attenuation of focal cerebral infarct in mice lacking NMDA receptor subunit NR2C. Neuroreport 9, 471–475. 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohara A., Takahashi M., Yatsugi S., Tamura S., Shitaka Y., Hayashibe S., et al. (2008). Neuroprotective effects of the selective type 1 metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist YM-202074 in rat stroke models. Brain Res. 1191, 168–179. 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak S., Weiss J. H. (2006). Calcium-permeable AMPA channels in neurodegenerative disease and ischemia. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 281–287. 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai T. W., Zhang S., Wang Y. T. (2014). Excitotoxicity and stroke: identifying novel targets for neuroprotection. Prog. Neurobiol. 115, 157–188. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Wei Z. Z., Chen D., Gu X., Wei L., Yu S. P. (2015). A neuroprotective role of the NMDA receptor subunit GluN3A (NR3A) in ischemic stroke of the adult mouse. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 308, C570–C577. 10.1152/ajpcell.00353.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerma J., Marques J. M. (2013). Kainate receptors in health and disease. Neuron 80, 292–311. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Zhang N., Sun G., Ding S. (2013). Inhibition of the group I mGluRs reduces acute brain damage and improves long-term histological outcomes after photothrombosis-induced ischaemia. ASN Neuro 5, 195–207. 10.1042/an20130002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. H., Dong J., Tang Y., Ni H. Y., Zhang Y., Su P., et al. (2017). Opening a new time window for treatment of stroke by targeting HDAC2. J. Neurosci. 37, 6712–6728. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0341-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippert K., Welsch M., Krieglstein J. (1994). Over-additive protective effect of dizocilpine and NBQX against neuronal damage. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 253, 207–213. 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90193-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Lau L., Wei J., Zhu D., Zou S., Sun H. S., et al. (2004). Expression of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptor channels primes cell death in transient forebrain ischemia. Neuron 43, 43–55. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Liao M., Mielke J. G., Ning K., Chen Y., Li L., et al. (2006). Ischemic insults direct glutamate receptor subunit 2-lacking AMPA receptors to synaptic sites. J. Neurosci. 26, 5309–5319. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0567-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wong T. P., Aarts M., Rooyakkers A., Liu L., Lai T. W., et al. (2007). NMDA receptor subunits have differential roles in mediating excitotoxic neuronal death both in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurosci. 27, 2846–2857. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0116-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Zhao W., Xu T., Pei D., Peng Y. (2010). Alterations of NMDA receptor subunits NR1, NR2A and NR2B mRNA expression and their relationship to apoptosis following transient forebrain ischemia. Brain Res. 1361, 133–139. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry E. R., Kruyer A., Norris E. H., Cederroth C. R., Strickland S. (2013). The GluK4 kainate receptor subunit regulates memory, mood and excitotoxic neurodegeneration. Neuroscience 235, 215–225. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.01.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Q., Liu Y., Han D., Xu J., Zong Y. Y., Wang Y., et al. (2012). Neuroprotection of GluK1 kainate receptor agonist ATPA against ischemic neuronal injury through inhibiting GluK2 kainate receptor-JNK3 pathway via GABAA receptors. Brain Res. 1456, 1–13. 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrez R., Obiang P., Gauberti M., Roussel B., Baron A., Parcq J., et al. (2011). Antibodies preventing the interaction of tissue-type plasminogen activator with N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors reduce stroke damages and extend the therapeutic window of thrombolysis. Stroke 42, 2315–2322. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.606293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarewicz D., Słomka M., Danysz W., Łazarewicz J. W. (2015). Effects of mGluR5 positive and negative allosteric modulators on brain damage evoked by hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal rats. Folia Neuropathol. 53, 301–308. 10.5114/fn.2015.56544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel M. A., Ryan T. J., Bell K. F., Fowler J. H., McMahon A., Al-Mubarak B., et al. (2012). The subtype of GluN2 C-terminal domain determines the response to excitotoxic insults. Neuron 74, 543–556. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroiacovo F., Moyanova S., Cannella M., Gaglione A., Verhaeghe R., Bozza G., et al. (2017). Genetic deletion of mGlu2 metabotropic glutamate receptors improves the short-term outcome of cerebral transient focal ischemia. Mol. Brain 10:39. 10.1186/s13041-017-0319-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matucz E., Móricz K., Gigler G., Benedek A., Barkóczy J., Lévay G., et al. (2006). Therapeutic time window of neuroprotection by non-competitive AMPA antagonists in transient and permanent focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 1123, 60–67. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManigle J. E., Taveira Dasilva A. M., Dretchen K. L., Gillis R. A. (1994). Potentiation of MK-801-induced breathing impairment by 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo(F)quinoxaline. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 252, 11–17. 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90569-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meli E., Picca R., Attucci S., Cozzi A., Peruginelli F., Moroni F., et al. (2002). Activation of mGlu1 but not mGlu5 metabotropic glutamate receptors contributes to postischemic neuronal injury in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 73, 439–446. 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00834-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero M., Nielsen M., Rønn L. C., Møller A., Noraberg J., Zimmer J. (2007). Neuroprotective effects of the AMPA antagonist PNQX in oxygen-glucose deprivation in mouse hippocampal slice cultures and global cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Brain Res. 1177, 124–135. 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa E., Mori H., Kiyama Y., Mishina M., Asano T., Kirino T. (1998). Attenuation of focal ischemic brain injury in mice deficient in the epsilon1 (NR2A) subunit of NMDA receptor. J. Neurosci. 18, 9727–9732. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09727.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroni F., Attucci S., Cozzi A., Meli E., Picca R., Scheideler M. A., et al. (2002). The novel and systemically active metabotropic glutamate 1 (mGlu1) receptor antagonist 3-MATIDA reduces post-ischemic neuronal death. Neuropharmacology 42, 741–751. 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00033-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosinger J. L., Price M. T., Bai H. Y., Xiao H., Wozniak D. F., Olney J. W. (1991). Blockade of both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors is required for optimal protection against ischemic neuronal degeneration in the in vivo adult mammalian retina. Exp. Neurol. 113, 10–17. 10.1016/0014-4886(91)90140-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motolese M., Mastroiacovo F., Cannella M., Bucci D., Gaglione A., Riozzi B., et al. (2015). Targeting type-2 metabotropic glutamate receptors to protect vulnerable hippocampal neurons against ischemic damage. Mol. Brain 8:66. 10.1186/s13041-015-0158-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyanova S. G., Mastroiacovo F., Kortenska L. V., Mitreva R. G., Fardone E., Santolini I., et al. (2011). Protective role for type 4 metabotropic glutamate receptors against ischemic brain damage. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 1107–1118. 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhin A., Fan L., Faden A. I. (1996). Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype mGluR1 contributes to post-traumatic neuronal injury. J. Neurosci. 16, 6012–6020. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06012.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murotomi K., Takagi N., Takayanagi G., Ono M., Takeo S., Tanonaka K. (2008). mGluR1 antagonist decreases tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDA receptor and attenuates infarct size after transient focal cerebral ischemia. J. Neurochem. 105, 1625–1634. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M., Suda S., Sowa K., Sakamoto Y., Nito C., Nishiyama Y., et al. (2018). AMPA receptor antagonist perampanel ameliorates post-stroke functional and cognitive impairments. Neuroscience 386, 256–264. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi N., Tu S., Shin Y., Cui J., Kurokawa T., Zhang D., et al. (2009). Neuroprotection by the NR3A subunit of the NMDA receptor. J. Neurosci. 29, 5260–5265. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1067-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei D. S., Guan Q. H., Sun Y. F., Zhang Q. X., Xu T. L., Zhang G. Y. (2005). Neuroprotective effects of GluR6 antisense oligodeoxynucleotides on transient brain ischemia/reperfusion-induced neuronal death in rat hippocampal CA1 region. J. Neurosci. Res. 82, 642–649. 10.1002/jnr.20669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei D. S., Wang X. T., Liu Y., Sun Y. F., Guan Q. H., Wang W., et al. (2006). Neuroprotection against ischaemic brain injury by a GluR6–9c peptide containing the TAT protein transduction sequence. Brain 129, 465–479. 10.1093/brain/awh700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini-Giampietro D. E., Cozzi A., Peruginelli F., Leonardi P., Meli E., Pellicciari R., et al. (1999a). 1-Aminoindan-1,5-dicarboxylic acid and (S)-(+)-2–(3’-carboxybicyclo[1.1.1] pentyl)-glycine, two mGlu1 receptor-preferring antagonists, reduce neuronal death in in vitro and in vivo models of cerebral ischaemia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 3637–3647. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00786.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini-Giampietro D. E., Peruginelli F., Meli E., Cozzi A., Albani-Torregrossa S., Pellicciari R., et al. (1999b). Protection with metabotropic glutamate 1 receptor antagonists in models of ischemic neuronal death: time-course and mechanisms. Neuropharmacology 38, 1607–1619. 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00097-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riek-Burchardt M., Henrich-Noack P., Reymann K. G. (2007). No improvement of functional and histological outcome after application of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 agonist CHPG in a model of endothelin-1-induced focal ischemia in rats. Neurosci. Res. 57, 499–503. 10.1016/j.neures.2006.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanika R. I., Pivovarova N. B., Brantner C. A., Watts C. A., Winters C. A., Andrews S. B. (2009). Coupling diverse routes of calcium entry to mitochondrial dysfunction and glutamate excitotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 9854–9859. 10.1073/pnas.0903546106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Chen Y., Zhan L., Zhang L., Hu J., Gao Z. (2016). The role of non-receptor protein tyrosine kinases in the excitotoxicity induced by the overactivation of NMDA receptors. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 283–289. 10.1515/revneuro-2015-0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Cheng X., Hu J., Gao Z. (2018). The role of GluN2A in cerebral ischemia: promoting neuron death and survival in the early stage and thereafter. Mol. Neurobiol. 55, 1208–1216. 10.1007/s12035-017-0395-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Zhang L., Chen Y., Zhan L., Gao Z. (2015). Therapeutic targets for cerebral ischemia based on the signaling pathways of the GluN2B C terminus. Stroke 46, 2347–2353. 10.1161/strokeaha.115.009314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szydlowska K., Kaminska B., Baude A., Parsons C. G., Danysz W. (2007). Neuroprotective activity of selective mGlu1 and mGlu5 antagonists in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 554, 18–29. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.09.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi N., Besshoh S., Marunouchi T., Takeo S., Tanonaka K. (2012). Effects of metabotropic glutamate mGlu5 receptor antagonist on tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDA receptor subunits and cell death in the hippocampus after brain ischemia in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 530, 91–96. 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi N., Besshoh S., Morita H., Terao M., Takeo S., Tanonaka K. (2010). Metabotropic glutamate mGlu5 receptor-mediated serine phosphorylation of NMDA receptor subunit NR1 in hippocampal CA1 region after transient global ischemia in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 644, 96–100. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanzulli I., Butt A. M. (2015). mGluR5 protect astrocytes from ischemic damage in postnatal CNS white matter. Cell Calcium 58, 423–430. 10.1016/j.ceca.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vest R. S., O’Leary H., Coultrap S. J., Kindy M. S., Bayer K. U. (2010). Effective post-insult neuroprotection by a novel Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 20675–20682. 10.1074/jbc.m109.088617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgili M., Contestabile A., Barnabei O. (1995). Simultaneous blockade of non-NMDA ionotropic receptors and NMDA receptor-associated ionophore partially protects hippocampal slices from protein synthesis impairment due to simulated ischemia. Hippocampus 5, 91–97. 10.1002/hipo.450050111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Engelhardt J., Coserea I., Pawlak V., Fuchs E. C., Köhr G., Seeburg P. H., et al. (2007). Excitotoxicity in vitro by NR2A- and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. Neuropharmacology 53, 10–17. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Liu S., Fu Y., Wang J. H., Lu Y. (2003). Cdk5 activation induces hippocampal CA1 cell death by directly phosphorylating NMDA receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 1039–1047. 10.1038/nn1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Li S., Zhang H., Pei L., Zou S., Lee F. J., et al. (2012). Direct interaction between GluR2 and GAPDH regulates AMPAR-mediated excitotoxicity. Mol. Brain 5:13. 10.1186/1756-6606-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Yan H., Zhang S., Wei X., Zheng J., Li J. (2013). The GluN3A subunit exerts a neuroprotective effect in brain ischemia and the hypoxia process. ASN Neuro 5, 231–242. 10.1042/an20130009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. C., Sanchez-Mendoza E. H., Doeppner T. R., Hermann D. M. (2017). Post-acute delivery of memantine promotes post-ischemic neurological recovery, peri-infarct tissue remodeling and contralesional brain plasticity. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 37, 980–993. 10.1177/0271678x16648971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weilinger N. L., Lohman A. W., Rakai B. D., Ma E. M., Bialecki J., Maslieieva V., et al. (2016). Metabotropic NMDA receptor signaling couples Src family kinases to pannexin-1 during excitotoxicity. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 432–442. 10.1038/nn.4236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Liu Y., Zhang G. Y. (2008). Neuroprotection of GluR5-containing kainate receptor activation against ischemic brain injury through decreasing tyrosine phosphorylation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors mediated by Src kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29355–29366. 10.1074/jbc.M800393200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Wong T. P., Chery N., Gaertner T., Wang Y. T., Baudry M. (2007). Calpain-mediated mGluR1α truncation: a key step in excitotoxicity. Neuron 53, 399–412. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J. Z., Liu Y., Zong Y. Y., Zhang G. Y. (2012). Knock-down of postsynaptic density protein 95 expression by antisense oligonucleotides protects against apoptosis-like cell death induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation in vitro. Neurosci. Bull. 28, 69–76. 10.1007/s12264-012-1065-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X., Yu L., Zuo D., Zhang L., Zu J., Hu J., et al. (2017). Activated mGluR5 protects BV2 cells against OGD/R induced cytotoxicity by modulating BDNF-TrkB pathway. Neurosci. Lett. 654, 70–79. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagrean A. M., Spataru A., Ceanga M., Zagrean L. (2014). The single versus combinatorial effects of MK-801, CNQX, Nifedipine and AP-3 on primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells in an oxygen-glucose deprivation model. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 55, 811–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai D., Li S., Wang M., Chin K., Liu F. (2013). Disruption of the GluR2/GAPDH complex protects against ischemia-induced neuronal damage. Neurobiol. Dis. 54, 392–403. 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Hsu J. C., Takagi N., Gurd J. W., Wallace M. C., Eubanks J. H. (1997). Transient global ischemia alters NMDA receptor expression in rat hippocampus: correlation with decreased immunoreactive protein levels of the NR2A/2B subunits, and an altered NMDA receptor functionality. J. Neurochem. 69, 1983–1994. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69051983.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M., Liao M., Cui T., Tian H., Fan D. S., Wan Q. (2012). Regulation of nuclear TDP-43 by NR2A-containing NMDA receptors and PTEN. J. Cell Sci. 125, 1556–1567. 10.1242/jcs.095729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Ding Q., Chen Z., Yun H., Wang H. (2013). Involvement of the GluN2A and GluN2B subunits in synaptic and extrasynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function and neuronal excitotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 24151–24159. 10.1074/jbc.m113.482000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. H., Tang Y., Zhang X. Y., Luo C. X., Gao L. Y., Wu H. Y., et al. (2015). Delayed administration of tat-HA-NR2B9c promotes recovery after stroke in rats. Stroke 46, 1352–1358. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Xu W., Liao G., Bi X., Baudry M. (2009). Neuroprotection against neonatal hypoxia/ischemia-induced cerebral cell death by prevention of calpain-mediated mGluR1α truncation. Exp. Neurol. 218, 75–82. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]