Abstract

Objectives: The use of magnesium sulfate in the perioperative period has several benefits, including analgesia, inhibition of the release of catecholamines and prevention of vasospasm. The aim of this survey was to provide an overview of the use of magnesium sulfate in anesthesia.

Method: This was a prospective descriptive cross-sectional study. An online questionnaire was sent to 9,869 Brazilian anesthesiologists and trainees. The questionnaire comprised closed questions mainly regarding the frequency, clinical effects, adverse events, and doses of magnesium sulfate used in anesthesia.

Results: Of the 954 doctors who responded to the survey, 337 (35.32%) reported using magnesium sulfate in anesthesia. The most commonly cited clinical effects for the use of magnesium sulfate in anesthesia were (n/%): postoperative analgesia (245/72.70%), reduction of anesthetic consumption (240/71.21%) and prevention and treatment of preeclampsia and seizures in eclampsia (220/65.28%). The most frequently reported adverse events were hypotension (187/55.48%), residual neuromuscular blockade (133/39.46%), hypermagnesemia (30/8.90%), and intravenous injection pain (26/7.71%). The intravenous doses of magnesium sulfate used in most general anesthesia inductions were between 30 and 40 mg.kg−1.

Conclusions: Magnesium sulfate is an important adjuvant drug in the practice of anesthesia, with several clinical effects and a low incidence of adverse events when used at recommended doses.

Keywords: anesthetics (MeSH), analgesics, magnesium sulfate, survey, adverse events

Introduction

Magnesium is the fourth most common ion in the body, and it participates in several cellular processes, including protein synthesis, neuromuscular function and stability of nucleic acid, as well as regulating other electrolytes such as calcium and sodium. Magnesium acts as a cofactor in protein synthesis, neuromuscular function and stability and the function of nucleic acids. It is a component of adenosine 5-triphosphatases and an endogenous regulator of other electrolytes. It is a calcium antagonist because it is a non-competitive inhibitor of calcium channels with inositol triphosphate. Magnesium modulates sodium and potassium currents and, as a consequence, interferes with the transmembrane potential. It is a central nervous system depressant, antagonizing N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and inhibiting the release of catecholamines (Herroeder et al., 2011).

Some studies have shown that the use of magnesium sulfate as an adjunct in anesthesia reduces intraoperative consumption of anesthetics (Koinig et al., 1998; Seyhan et al., 2006; Ryu et al., 2008; Forget and Cata, 2017). It also provides better analgesia and reduces the amount of morphine used in the postoperative period (Mentes et al., 2008; Dabbagh et al., 2009; Hwang et al., 2010). Studies in clinical practice have demonstrated the inhibitory effects of magnesium on the release of catecholamines (Herroeder et al., 2011) through better hemodynamic control during laryngoscopy (Puri et al., 1998; Shin et al., 2011) and pneumoperitoneum insufflation for videolaparoscopy (Mentes et al., 2008). Magnesium sulfate also reduces levels of noradrenaline and vasopressin during anesthesia (Jee et al., 2009).

Other benefits of using intraoperative magnesium have been reported, including hemodynamic control in surgeries for resection of pheochromocytoma (James and Cronjé, 2004), reduced incidence of atrial fibrillation in myocardial revascularization surgeries (Toraman et al., 2001), and prevention of vasospasm (Wong et al., 2006) and neurological protection after subarachnoid hemorrhage (Schmid-Elsaesser et al., 2006). The attenuation of the release of catecholamines by the adrenal glands and antagonism to calcium in smooth muscle cells of arterioles are possible mechanisms of action (Herroeder et al., 2011).

The clinical duration of nondepolarizing neuromuscular blockers is prolonged with the use of magnesium sulfate in anesthesia (Fuchs-Buder et al., 1995; Kussman et al., 1997; Czarnetzki et al., 2010; Rotava et al., 2013). Magnesium interferes with neuromuscular function by reducing the conductance of calcium in presynaptic membranes, decreasing the amount of acetylcholine released by motor neurons (Herroeder et al., 2011). It may also reduce post-synaptic sensitivity to acetylcholine or have a direct effect on the membrane potential of muscle cells (Del Castillo and Engbaek, 1954).

This survey was conducted to contribute evidence on the use of magnesium sulfate as adjunct of anesthesia due to its potential clinical benefits.

The primary objective of this study was to know the use profile of Magnesium Sulfate in Anesthesia in Brazil.

Materials and Methods

The descriptive study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Fluminense Federal University, Niterói, RJ, Brazil (CAAE 35038614.0.0000.5243, opinion 884.839, dated 11/13/2014). The informed consent form was signed electronically.

All the anesthesiologists and trainees members of Brazilian Society of Anesthesiology in 2015 were invited to participate. A self-administered electronic questionnaire was sent via e-mail to 9,869 potential participants of the research using the Survey Monkey software. The invitation was sent by 3 times with the 10-day interval between them.

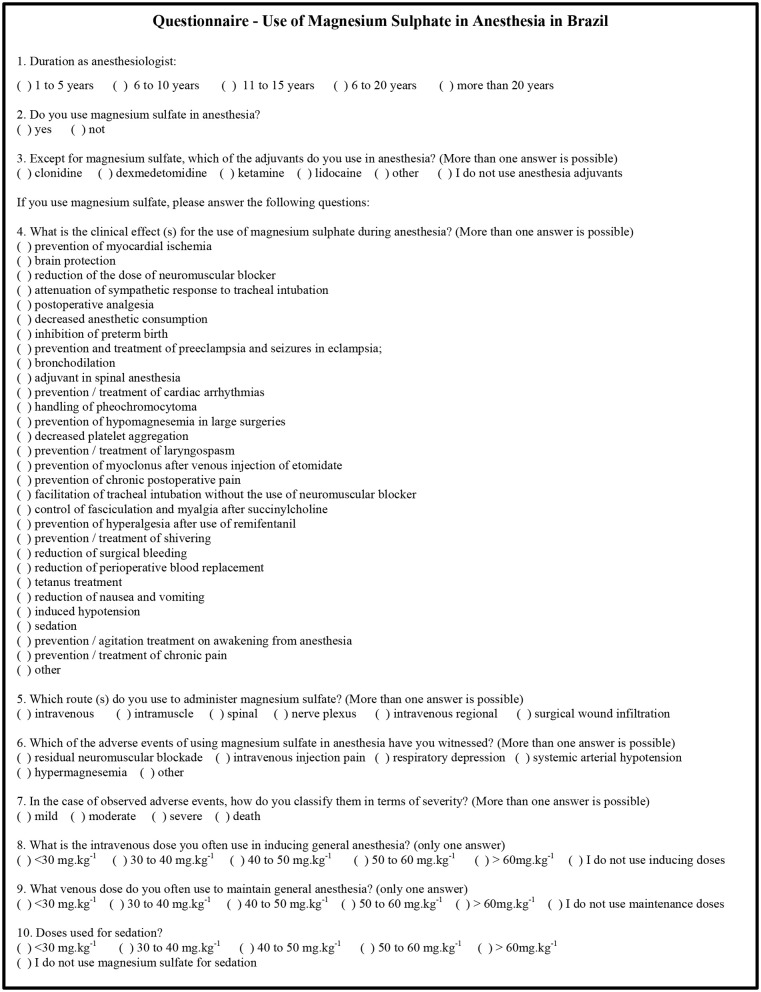

We did not find in the literature a data collection instrument on the subject of this research. The lead researcher created the electronic questionnaire used in this research, composed of 10 closed questions that addressed the following aspects: duration of practice of anesthesiology, use of magnesium sulfate and other anesthesia adjuvants, indications, complications and doses of magnesium sulfate in anesthesia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Electronic questionnaire used in research “Use of Magnesium Sulfate in Anesthesia in Brazil.” Brazil, 2015.

The instrument was pre-tested in two stages. In the first stage, the relevance of the instrument was evaluated and was carried out by the researchers themselves. In the second stage, the questionnaire was evaluated by 8 anesthesiologists and the results were used to create the final version of the questionnaire used in the research.

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The original data can be accessed in the Supplementary Table 1.

Results

Survey responses were received from 945 (9.57%) participants. The length of time of anesthesia practice among the respondents is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of anesthesiologists that answered the questionnaire (n = 945) by the duration of anesthesia practice (n, %).

| Time of practice of anesthesia | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Trainee | 135 | 14.29 |

| 1–5 years | 240 | 25.40 |

| 6–10 years | 116 | 12.27 |

| 11–15 years | 83 | 8.78 |

| 16–20 years | 82 | 8.67 |

| 21 years or more | 289 | 30.59 |

Brazil, 2015.

Of the 945 anesthesiologists who responded to this survey, 331 (35.02%) reported using magnesium sulfate in anesthesia. The frequency of use of adjuvant drugs in anesthesia is described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency of use of adjuvant drugs in anesthesia (n, %).

| Adjuvant drug | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Clonidine | 805 | 85.19 |

| Ketamine | 689 | 72.91 |

| Lidocaine | 614 | 64.97 |

| Dexmedetomidine | 417 | 44.12 |

| Magnesium sulfate | 331 | 35.02 |

| No use of adjuvant | 39 | 4.13 |

More than one response per participant was possible (n = 945). Brazil, 2015.

The number and percentage of clinical effects (n/%) for the use of magnesium sulfate in anesthesia were (in descending order, more than one response per participant allowed): postoperative analgesia (242/73,11%), reduction of anesthetic consumption (237/71.60%), prevention and treatment of preeclampsia and seizures in eclampsia (218/65.86%), prevention and treatment of arrhythmias (175/52.87%), reduction of the dose of neuromuscular blockers (168/50.75%), prevention of postoperative chronic pain (167/50.45%), bronchodilation (165/49.84%), prevention of hyperalgesia post remifentanil use (160/48.34%), hypomagnesemia prevention in large surgeries (128/38.67%), induced systemic arterial hypotension (112/33.83%), brain protection (95/28.70%), sedation (86/25.98%), reduction of surgical bleeding or reduction of perioperative blood replacement (74/22.35%), management of pheochromocytoma (72/21.75%), prevention and treatment of agitation in emergence from general anesthesia (64/19.33%), inhibition of preterm birth (59/17.82%), prevention of myocardial ischemia (54/16.31%), prevention and treatment of shivering (50/15.10%), facilitation of tracheal intubation without the use of neuromuscular blocker agent (44/13.29%), reduction of nausea and vomiting (39/11.78%), prevention and treatment of laryngospasm (38/11.48%), control of fasciculation and myalgia after succinylcholine (31/9.36%), prevention of myoclonus after intravenous injection of etomidate (24/7.25%), treatment of tetanus (20/6.04%), adjuvant in spinal anesthesia (19/5.74%), decrease in platelet aggregation (14/4.23%), attenuation of the sympathetic response to tracheal intubation (1/0.30%) and extension of duration of motor block on subdural anesthesia (1/0,30%).

All anesthesiologists reported using the intravenous route (331/100.00%) to administer magnesium sulfate. Other routes were used less frequently: muscular (16/4.83%), nerve plexus (6/1.81%), spinal (3/0.90%), regional intravenous anesthesia (3/0.90%), wound infiltration (2/0.60%), inhalation (2/0.60%), and oral (1/0.30%).

Table 3 shows the frequency of adverse events during use of magnesium sulfate witnessed at least once by the anesthesiologist. The most commonly reported were hypotension, residual neuromuscular blockade, hypermagnesemia, intravenous injection pain, and respiratory depression.

Table 3.

Frequency of adverse events during use of magnesium sulfate witnessed at least once by the anesthesiologist.

| Adverse events | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic arterial hypotension | 184 | 55.59 |

| Residual neuromuscular blockade | 131 | 39.57 |

| Hypermagnesemia | 28 | 8.45 |

| Intravenous injection pain | 22 | 6.64 |

| Respiratory depression | 22 | 6.64 |

| Heat sensation | 4 | 1.20 |

| Bradycardia | 4 | 1.20 |

| Facial/cervical flushing | 2 | 0.60 |

| Tachycardia | 2 | 0.60 |

| Intense sedation | 2 | 0.60 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 1 | 0.30 |

| Prolonged emergence from anesthesia | 1 | 0.30 |

| Myocardial depression | 1 | 0.3 |

| None | 40 | 12.08 |

More than one response per participant was possible (n = 331). Brazil, 2015.

Of the adverse events reported, 73.78% of the cases were considered of mild gravity (see Table 4). It should be noted that some adverse events were reported as severe, i.e., respiratory depression (4), hypotension (4), residual curarisation (4), hypermagnesemia (2) and bradycardia (1).

Table 4.

Rate of intensity level of adverse events witnessed by anesthesiologists using magnesium sulfate anesthesia (n = 305).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 225 | 73.78 |

| Moderate | 71 | 23.27 |

| Severe | 9 | 2.95 |

Brazil, 2015.

Table 5 shows the dosages of intravenous magnesium sulfate commonly used for induction of general anesthesia and sedation.

Table 5.

Magnesium sulfate intravenous doses most commonly used in the induction of general anesthesia and sedation (n = 331).

| Doses | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induction of general anesthesia | < 30 mg.kg−1 | 55 | 16.61 |

| 30–40 mg.kg−1 | 114 | 34.45 | |

| 40–50 mg.kg−1 | 47 | 14.20 | |

| 50–60 mg.kg−1 | 9 | 2.71 | |

| No use for induction of general anesthesia | 106 | 32.03 | |

| Sedation | < 30 mg.kg−1 | 58 | 17.52 |

| 30–40 mg.kg−1 | 28 | 8.46 | |

| 40–50 mg.kg−1 | 10 | 3.02 | |

| 50–60 mg.kg−1 | 1 | 0.30 | |

| No use for sedation | 234 | 70.70 |

Brazil, 2015.

Discussion

Little or no scientific literature exists that reports on surveys on the use of magnesium sulfate in anesthesia.

Approximately 10% of those who received the invitation to participate completed the survey, specifically, 945 anesthesiologists. Several medical polls have reported similar response rates (Naguib et al., 2010; Locks et al., 2015). Low adherence of participants can be explained by the electronic method used for data collection.

Duration of Anesthesia Practice of the Survey Participants

In the present survey, anesthesiologists with more than 20 years of anesthesia practice (30.59%) reported using magnesium sulfate in anesthesia and sedation most frequently; this group was followed by those with between 1 and 5 years of clinical practice (25.40%). The frequent use of magnesium sulfate among the more experienced anesthesiologists may stem from common use in certain specialties, particularly obstetrics. The high frequency of use of magnesium sulfate among the younger group of anesthesiologists may be result of the recent attention being paid to this drug, as well as the introduction of multimodal analgesic and anesthesia techniques (Czarnetzki et al., 2010; Herroeder et al., 2011; Shin et al., 2011; Rotava et al., 2013).

Adjuvant Drugs in Anesthesia

Anesthesia adjuvants are agents that are administered in association with anesthetics to increase effectiveness, improve delivery, or decrease required dosage. The survey showed that the drug most commonly used in Brazil as an anesthesia adjuvant is clonidine (85.18%); magnesium sulfate (35.02%) ranks fifth among the medicines included as possible survey responses.

Giovannitti et al. (2015) postulated that agonists of the α-2 adrenergic receptors, including clonidine and dexmedetomidine, are important tools in the arsenal of modern anesthesia because of their ability to induce calm without causing respiratory depression. They also promote cardiovascular stability and reduce anesthetic requirements.

The drug reported as the second most frequently used adjuvant was ketamine. Bakan et al. (2014) conducted a randomized clinical trial and showed that ketamine, when associated with remifentanil in total intravenous anesthesia in children, is well suited to rigid bronchoscopic procedures.

Although this survey found that lidocaine ranked third on the list of most used drugs, Kranke et al. (2015), in a systematic review, reported that there is only little or moderate evidence that a continuous infusion of lidocaine has an impact on pain intensity, especially in the early postoperative period, or on postoperative nausea. There is limited evidence that it has consequences in other clinical outcomes, such as gastrointestinal recovery, length of hospital stay and opioid use (Kranke et al., 2015).

Gupta et al. (2006) demonstrated that magnesium sulfate has anesthetic, analgesic and muscle relaxing effects and significantly reduces the need for anesthetic drugs and neuromuscular blockers.

Clinical Effects of Magnesium Sulfate in Anesthesia

As noted in this survey, there is a wide range of clinical effects for the use of magnesium sulfate in anesthesia. The great variety of clinical effects could be explained by the substantial involvement of magnesium in the physiology of various organs and systems.

Magnesium participates in over 325 cellular enzyme systems and is the second most abundant intracellular cation after potassium. Magnesium participates in numerous physiological and homeostatic functions, such as binding of hormone receptors, the transmembrane flow of ions, regulation of adenylate cyclase, calcium release, muscle contraction, cardiac excitability, neuronal activity, control of vasomotor tone and release of neurotransmitters, blood pressure and peripheral blood flow. Mg2+ modulates and controls the input of cell Ca2+ and Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Altura, 1994).

Magnesium is essential in the transfer, storage and utilization of energy in cells. The intracellular level of free Mg2+ ([Mg2+]i) regulates intermediate metabolism, synthesis and structure of DNA and RNA, cell growth, reproduction and membrane structure (Altura and Altura, 1996).

Dubé and Granry (2003) cited the therapeutic use of magnesium in the following anesthesia, intensive care and emergency situations: prevention and treatment of hypomagnesemia, induction of anesthesia, control of pheochromocytoma, cardiac arrhythmias, preeclampsia and eclampsia, perioperative analgesia, asthma, myocardial infarction, hypertensive crisis, and insulin resistance.

Roscoe and Ahmed conducted a postal survey of cardiac anesthetists in the United Kingdom, to determine the extent of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) use and the main indications for its administration. The most common indications for administration were arrhythmia prophylaxis and treatment, myocardial protection and treatment of hypomagnesemia (Roscoe and Ahmed, 2003).

All the clinical effects for the use of magnesium sulfate in anesthesia presented by the anesthesiologists participating in this survey have been reported in other publications, including various systematic reviews and meta-analyses, although some of them are still subjects of controversy Beşogul et al., 2009; Gozdemir et al., 2010; Rhee et al., 2012; Abdulatif et al., 2013; Rotava et al., 2013; Agrawal et al., 2014; Ahsan et al., 2014; Crowther et al., 2014; Kahraman and Eroglu, 2014; Kew et al., 2014; Marzban et al., 2014; Rodrigo et al., 2014; Srebro et al., 2014; Uludag et al., 2014; Berhan and Berhan, 2015; Kim et al., 2015; Safavi et al., 2015; Vigil-De Gracia and Ludmir, 2015; Demiroglu et al., 2016; Green, 2016; Griffiths and Kew, 2016; Jangra et al., 2016; Juibari et al., 2016; Maged et al., 2016; Naghipour et al., 2016; Rodríguez-Rubio et al., 2016, 2017; Soltani et al., 2016; Thomas and Behr, 2016; Ulm et al., 2016; Vendrell et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2016, 2017; Brookfield et al., 2017; Haryalchi et al., 2017; Kutlesic et al., 2017; Lecuyer et al., 2017; McKeown et al., 2017; Mendonca et al., 2017; Salaminia et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018.

Adverse Events of Magnesium Sulfate Use and Classification of Intensity

Herroeder et al. (2011) reported that the vasodilator effect of magnesium is the likely cause of burning or heat sensations in the body. Prolonged PR and QT intervals as well as atrioventricular blockage may occur. Toxicity occurs with the administration of venous doses greater than 30 g or with plasma concentrations above 14.4 mg/dl (Herroeder et al., 2011). Hypermagnesemia is manifested by abolition of tendon reflex; treatment consists of calcium gluconate, furosemide furosemide and hemodialysis (Herroeder et al., 2011).

In this survey, 2.95% of respondents reported severe complications from the use of magnesium sulfate. It is worth mentioning that the occurrence of severe adverse events is of fundamental importance, demonstrating that the administration of magnesium sulfate is not risk free. As in the present research, Herroeder et al. (2011) related as severe adverse events from the use of magnesium sulfate: arterial hypotension, bradycardia, muscle weakness, and respiratory depression. The results of our survey demonstrated similar results. Despite the occurrence of reports of serious AEs, the use of magnesium sulfate can be safe in recommended doses with close monitoring of patients (Kutlesic et al., 2017).

Marret and Ancel (2016) used magnesium sulfate in obstetric patients at an initial venous dose of 4 g followed by 1 g/h, without exceeding the cumulative total dose of 50 g. In their analysis of short and medium-term outcomes, they found no serious maternal adverse effects nor adverse effects on the newborns.

Griffiths and Kew (2016) observed few adverse effects when intravenous magnesium sulfate was used for treatment of asthma in children in the emergency department.

Wilson et al. (2014) realized a retrospective cohort study to evaluated the tolerability and safety of high doses of intravenous magnesium sulfate for tocolysis in preterm labor. The frequency of severe adverse events was 5.3% while in our survey it was 2.95%. This difference can be explained because all patients in the study received high doses of magnesium sulfate. They concluded that side effects occurred in 9 out of 10 patients and were considered severe for 1 out of every 20 pregnant women.

Intravenous Dose of Magnesium Sulfate Most Frequently Used in Induction of General Anesthesia and Sedation

Germano Filho et al. (2015), in a randomized controlled study, demonstrated a significant increase in magnesium plasma concentrations after infusions of 40 mg.kg−1 solution containing magnesium sulfate among ASA 1 or 2 patients. This confirmed that this dose is capable of increasing magnesium serum levels.

The magnesium sulfate doses reported in this survey are in accordance with those found in other publications. There are reports of magnesium sulfate induction doses in general anesthesia from 15 mg.kg−1 to 75 mg.kg−1 (Beşogul et al., 2009; Gozdemir et al., 2010; Rotava et al., 2013; Kahraman and Eroglu, 2014; Rodrigo et al., 2014; Honarmand et al., 2015; Rower et al., 2017) and doses up to 50 mg.kg−1 in sedation (Lecuyer et al., 2017).

We observed that the Brazilian anesthesiologist uses magnesium sulfate rationally. Clinical effects, doses and routes of administration are found in the literature.

This survey describes the wide range of purposes magnesium sulfate is used for in anesthesia in Brazil. Although anesthesiologists have free access to the use of magnesium sulfate, research data have shown that the drug has been used primarily in those indications approved by the Health Authorities and/or supported by critical evaluation of systematic reviews and meta-analyzes. The frequency of its use is related to the amount and strength of evidence of its effects reported in the literature.

This survey has some limitations. Only Brazilian anesthesiologists participated in the study. Further, the participation of the anesthesiologists was voluntary; those who agreed to participate are likely those most interested in the use of magnesium sulfate in anesthesia. This may have created bias that could interfere with the generalization of the responses to the full population of anesthesia specialists. Only 10% effectively responded to the survey, that the results may thus be biased. The questionnaire was not validated.

We conclude that magnesium sulfate is among the five most commonly used adjuvants in anesthesia, along with clonidine, ketamine, lidocaine and dexmedetomidine. Several clinical effects for magnesium sulfate were reported, especially postoperative analgesia, reduction of anesthetic consumption and the prevention and treatment of preeclampsia and eclampsia seizures. Hypotension, residual neuromuscular blockade, hypermagnesemia and pain on intravenous injection were the most frequent adverse events and, in general, were considered mild. Magnesium sulfate intravenous doses used in most general anesthesia induction were between 30 and 40 mg.kg−1.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Brazilian National Health Council (Resolution number 466, from December 12, 2012) with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Fluminense Federal University, Niterói, RJ, Brazil (CAAE 35038614.0.0000.5243, opinion 884.839, dated 11/13/2014).

Author Contributions

IC, FL, and MS designed the study and performed the experiments, IC, RCF, EB, and NV analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. The study was supported by the Fluminense Federal University, Niterói, Brazil and Brazilian Society of Anesthesiology, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. There was no funding source for this study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2019.00429/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abdulatif M., Ahmed A., Mukhtar A., Badawy S. (2013). The effect of magnesium sulphate infusion on the incidence and severity of emergence agitation in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy using sevoflurane anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 68, 1045–1052. 10.1111/anae.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A., Agrawal S., Payal Y. S. (2014). Effect of continuous magnesium sulfate infusion on spinal block characteristics: a prospective study. Saudi J. Anaesth. 8, 78–82. 10.4103/1658-354X.125945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan B., Rahimi E., Moradi A., Rashadmanesh N. (2014). The effects of magnesium sulphate on succinylcholine-induced fasciculation during induction of general anaesthesia. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 64, 1151–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altura B. M. (1994). Introduction: importance of Mg in physiology and medicine and the need for ion selective electrodes. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. Suppl. 217, 5–9. 10.1080/00365519409095206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altura B. M., Altura B. T. (1996). Role of magnesium in patho-physiological processes and the clinical utility of magnesium ion selective electrodes. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. Suppl. 224, 211–234. 10.3109/00365519609088642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakan M., Topuz U., Umutoglu T., Gundogdu G., Ilce Z., Elicevik M., et al. (2014). Remifentanil-based total intravenous anesthesia for pediatric rigid bronchoscopy: comparison of adjuvant propofol and ketamine. Clinics 69, 372–377. 10.6061/clinics/2014(06)01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhan Y., Berhan A. (2015). Should magnesium sulfate be administered to women with mild pre-eclampsia? A systematic review of published reports on eclampsia. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 41, 831–842. 10.1111/jog.12697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beşogul Y., Gemalmaz H., Aslan R. (2009). Effects of preoperative magnesium therapy on arrhythmias and myocardial ischemia during off-pump coronary surgery. Ann. Thorac. Med. 4, 137–139. 10.4103/1817-1737.53355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield K. F., Elkomy M., Su F., Drover D. R., Carvalho B. (2017). Optimization of maternal magnesium sulfate administration for fetal neuroprotection: application of a prospectively constructed pharmacokinetic model to the BEAM cohort. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57, 1419–1424. 10.1002/jcph.941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther C. A., Brown J., McKinlay C. J., Middleton P. (2014). Magnesium sulphate for preventing preterm birth in threatened preterm labour. Cochr. Datab. Syst. Rev. 15:CD001060 10.1002/14651858.CD001060.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnetzki C., Lysakowski C., Elia N., Tramèr M. R. (2010). Time course of rocuronium-induced neuromuscular block after pre-treatment with magnesium sulphate: a randomised study. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 54, 299–306. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbagh A., Elyasi H., Razavi S. S., Fathi M., Rajaei S. (2009). Intravenous magnesium sulfate for post-operative pain in patients undergoing lower limb orthopedic surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 53, 1088–1091. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Castillo J., Engbaek L. (1954). The nature of the neuromuscular block produced by magnesium. J. Physiol. 124, 370–384. 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiroglu M., Ün C., Ornek D. H., Kici O., Yildirim A. E., Horasanli E., et al. (2016). The effect of systemic and regional use of magnesium sulfate on postoperative tramadol consumption in lumbar disc surgery. Biomed Res. Int. 2016:3216246. 10.1155/2016/3216246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubé L., Granry J. C. (2003). The therapeutic use of magnesium in anesthesiology, intensive care and emergency medicine: a review. Can. J. Anaesth. 50, 732–746. 10.1007/BF03018719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget P., Cata J. (2017). Stable anesthesia with alternative to opioids: Are ketamine and magnesium helpful in stabilizing hemodynamics during surgery? A systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 31, 523–531. 10.1016/j.bpa.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs-Buder T., Wilder-Smith O. H., Borgeat A., Tassonyi E. (1995). Interaction of magnesium sulphate with vecuronium-induced neuromuscular block. Br. J. Anaesth. 74, 405–409. 10.1093/bja/74.4.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germano Filho P. A., Cavalcanti I. L., Barrucand L., Verçosa N. (2015). Effect of magnesium sulphate on sugammadex reversal time for neuromuscular blockade: a randomised controlled study. Anaesthesia 70, 956–961. 10.1111/anae.12987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannitti J. A., Thoms S. M., Crawford J. J. (2015). Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists: a review of current clinical applications. Anesth. Prog. 62, 31–38. 10.2344/0003-3006-62.1.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozdemir M., Usta B., Demircioglu R. I., Muslu B., Sert H., Karatas O. F. (2010). Magnesium sulfate infusion prevents shivering during transurethral prostatectomy with spinal anesthesia: a randomized, double-blinded, controlled study. J. Clin. Anesth. 22, 184–189. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R. H. (2016). Asthma in adults (acute): magnesium sulfate treatment. Clin. Evid. 01:1513. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths B., Kew K. M. (2016). Intravenous magnesium sulfate for treating children with acute asthma in the emergency department. Cochr. Datab. Syst. Rev. 4:Cd011050. 10.1002/14651858.CD011050.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K., Vohra V., Sood J. (2006). The role of magnesium as an adjuvant during general anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 61, 1058–1063. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04801.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haryalchi K., Abedinzade M., Khanaki K., Mansour Ghanaie M., Mohammad Zadeh F. (2017). Whether preventive low dose magnesium sulphate infusion has an influence on postoperative pain perception and the level of serum beta-endorphin throughout the total abdominal hysterectomy. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. 64, 384–390. 10.1016/j.redar.2016.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herroeder S., Schönherr M. E., De Hert S. G., Hollmann M. W. (2011). Magnesium–essentials for anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology 114, 971–993. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318210483d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honarmand A., Safavi M., Badiei S., Daftari-Fard N. (2015). Different doses of intravenous magnesium sulfate on cardiovascular changes following the laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 4, 79–84. 10.4103/2279-042X.154365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J. Y., Na H. S., Jeon Y. T., Ro Y. J., Kim C. S., Do S. H. (2010). I.V. infusion of magnesium sulphate during spinal anaesthesia improves postoperative analgesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 104, 89–93. 10.1093/bja/aep334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James M. F., Cronjé L. (2004). Pheochromocytoma crisis: the use of magnesium sulfate. Anesth. Analg. 99, 680–686. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000133136.01381.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jangra K., Malhotra S. K., Gupta A., Arora S. (2016). Comparison of quality of the surgical field after controlled hypotension using esmolol and magnesium sulfate during endoscopic sinus surgery. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 32, 325–328. 10.4103/0970-9185.173400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee D., Lee D., Yun S., Lee C. (2009). Magnesium sulphate attenuates arterial pressure increase during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br. J. Anaesth. 103, 484–489. 10.1093/bja/aep196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juibari H. M., Eftekharian H. R., Arabion H. R. (2016). Intravenous magnesium sulfate to deliberate hypotension and bleeding after bimaxillary orthognathic surgery; a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J. Dent. 17, 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahraman F., Eroglu A. (2014). The effect of intravenous magnesium sulfate infusion on sensory spinal block and postoperative pain score in abdominal hysterectomy. Biomed Res. Int. 2014:236024. 10.1155/2014/236024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kew K. M., Kirtchuk L., Michell C. I. (2014). Intravenous magnesium sulfate for treating adults with acute asthma in the emergency department. Cochr. Datab. Syst. Rev. 28:CD010909 10.1002/14651858.CD010909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. E., Shin C. S., Lee Y. C., Lee H. S., Ban M., Kim S. Y. (2015). Beneficial effect of intravenous magnesium during endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasm. Surg. Endosc. 29, 3795–3802. 10.1007/s00464-015-4514-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinig H., Wallner T., Marhofer P., Andel H., Hörauf K., Mayer N. (1998). Magnesium sulfate reduces intra- and postoperative analgesic requirements. Anesth. Analg. 87, 206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranke P., Jokinen J., Pace N. L., Schnabel A., Hollmann M. W., Hahnenkamp K., et al. (2015). Continuous intravenous perioperative lidocaine infusion for postoperative pain and recovery. Cochr. Datab. Syst. Rev. 16:CD009642 10.1002/14651858.CD009642.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussman B., Shorten G., Uppington J., Comunale M. E. (1997). Administration of magnesium sulphate before rocuronium: effects on speed of onset and duration of neuromuscular block. Br. J. Anaesth. 79, 122–124. 10.1093/bja/79.1.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlesic M. S., Kutlesic R. M., Mostic-Ilic T. (2017). Magnesium in obstetric anesthesia and intensive care. J. Anesth. 31, 127–139. 10.1007/s00540-016-2257-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuyer M., Rubio M., Chollat C., Lecointre M., Jégou S., Leroux P., et al. (2017). Experimental and clinical evidence of differential effects of magnesium sulfate on neuroprotection and angiogenesis in the fetal brain. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 5, e00315 10.1002/prp2.315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locks G. D. F., Cavalcanti I. L., Duarte N. M., Da Cunha R. M., De Almeida M. C. (2015). Use of neuromuscular blockers in Brazil. Braz. J. Anesthesiol. 65, 319–325. 10.1016/j.bjan.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maged A. M., Hashem A. M., Gad Allah S. H., Mahy M. E., Mostafa W. A., Kotb A. (2016). The effect of loading dose of magnesium sulfate on uterine, umbilical, and fetal middle cerebral arteries Doppler in women with severe preeclampsia: a case control study. Hypertens. Pregnancy 35, 91–99. 10.3109/10641955.2015.1116552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marret S., Ancel P. (2016). Neuroprotection for preterm infants with antenatal magnesium sulphate. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod. 45, 1418–1433. 10.1016/j.jgyn.2016.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzban S., Haddadi S., Naghipour M. R., Sayah Varg Z., Naderi Nabi B. (2014). The effect of intravenous magnesium sulfate on laryngospasm after elective adenotonsillectomy surgery in children. Anesth. Pain Med. 4:e15960. 10.5812/aapm.15960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown A., Seppi V., Hodgson R. (2017). Intravenous magnesium sulphate for analgesia after caesarean section: a systematic review. Anesthesiol. Res. Pract. 2017:9186374. 10.1155/2017/9186374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendonca F. T., de Queiroz L. M., Guimaraes C. C., Xavier A. C. (2017). Effects of lidocaine and magnesium sulfate in attenuating hemodynamic response to tracheal intubation: single-center, prospective, double-blind, randomized study. Rev. Bras. Anestesiol. 67, 50–56. 10.1016/j.bjane.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentes O., Harlak A., Yigit T., Balkan A., Balkan M., Cosar A., et al. (2008). Effect of intraoperative magnesium sulphate infusion on pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 52, 1353–1359. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01816.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghipour B., Faridaalaee G., Shadvar K., Bilehjani E., Khabaz A. H., Fakhari S. (2016). Effect of prophylaxis of magnesium sulfate for reduction of postcardiac surgery arrhythmia: randomized clinical trial. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 19, 662–667. 10.4103/0971-9784.191577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib M., Kopman A. F., Lien C. A., Hunter J. M., Lopez A., Brull S. J. (2010). A survey of current management of neuromuscular block in the United States and Europe. Anesth. Analg. 111, 110–119. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c07428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri G. D., Marudhachalam K. S., Chari P., Suri R. K. (1998). The effect of magnesium sulphate on hemodynamics and its efficacy in attenuating the response to endotracheal intubation in patients with coronary artery disease. Anesth. Analg. 87, 808–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee E., Beiswenger T., Oguejiofor C. E., James A. H. (2012). The effects of magnesium sulfate on maternal and fetal platelet aggregation. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 25, 478–483. 10.3109/14767058.2011.584087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo C., Fernando D., Rajapakse S. (2014). Pharmacological management of tetanus: an evidence-based review. Crit Care 18:217. 10.1186/cc13797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Rubio L., Del Pozo J. S. G., Nava E., Jordan J. (2016). Interaction between magnesium sulfate and neuromuscular blockers during the perioperative period. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Anesth. 34, 524–534. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Rubio L., Nava E., Del Pozo J. S. G., Jordán J. (2017). Influence of the perioperative administration of magnesium sulfate on the total dose of anesthetics during general anesthesia. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Anesth. 39, 129–138. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe A., Ahmed A. B. (2003). A survey of peri-operative use of magnesium sulphate in adult cardiac surgery in the UK. Anaesthesia 58, 363–365. 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03082_1.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotava P., Cavalcanti I. L., Barrucand L., Vane L. A., Verçosa N. (2013). Effects of magnesium sulphate on the pharmacodynamics of rocuronium in patients aged 60 years and older: a randomised trial. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 30, 599–604. 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328361d342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rower J. E., Liu X., Yu T., Mundorff M., Sherwin C. M., Johnson M. D. (2017). Clinical pharmacokinetics of magnesium sulfate in the treatment of children with severe acute asthma. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 73, 325–331. 10.1007/s00228-016-2165-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J. H., Kang M. H., Park K. S., Do S. H. (2008). Effects of magnesium sulphate on intraoperative anaesthetic requirements and postoperative analgesia in gynaecology patients receiving total intravenous anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 100, 397–403. 10.1093/bja/aem407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safavi M., Honarmand A., Sahaf A. S., Sahaf S. M., Attari M., Payandeh M., et al. (2015). Magnesium sulfate versus lidocaine pretreatment for prevention of pain on etomidate injection: a randomized, double-blinded placebo controlled trial. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 4, 4–8. 10.4103/2279-042X.150044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salaminia S., Sayehmiri F., Angha P., Sayehmiri K., Motedayen M. (2018). Evaluating the effect of magnesium supplementation and cardiac arrhythmias after acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 18:129. 10.1186/s12872-018-0857-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid-Elsaesser R., Kunz M., Zausinger S., Prueckner S., Briegel J., Steiger H. J. (2006). Intravenous magnesium versus nimodipine in the treatment of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a randomized study. Neurosurgery 58, 1054–1065. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000215868.40441.D9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyhan T. O., Tugrul M., Sungur M. O., Kayacan S., Telci L., Pembeci K., et al. (2006). Effects of three different dose regimens of magnesium on propofol requirements, haemodynamic variables and postoperative pain relief in gynaecological surgery. Br. J. Anaesth. 96, 247–252. 10.1093/bja/aei291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y. H., Choi S. J., Jeong H. Y., Kim M. H. (2011). Evaluation of dose effects of magnesium sulfate on rocuronium injection pain and hemodynamic changes by laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 60, 329–333. 10.4097/kjae.2011.60.5.329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltani H. A., Hashemi S. J., Montazeri K., Dehghani A., Nematbakhsh M. (2016). The role of magnesium sulfate in tracheal intubation without muscle relaxation in patients undergoing ophthalmic surgery. J. Res. Med. Sci. 21:96. 10.4103/1735-1995.193168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srebro D. P., Vucković S., Vujović K. S., Prostran M. (2014). Anti-hyperalgesic effect of systemic magnesium sulfate in carrageenan-induced inflammatory pain in rats: influence of the nitric oxide pathway. Magnes. Res. 27, 77–85. 10.1684/mrh.2014.0364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. H., Behr E. R. (2016). Pharmacological treatment of acquired QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 81, 420–427. 10.1111/bcp.12726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toraman F., Karabulut E. H., Alhan H. C., Dagdelen S., Tarcan S. (2001). Magnesium infusion dramatically decreases the incidence of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 72, 1256–1261. 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)02898-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulm M. A., Watson C. H., Vaddadi P., Wan J. Y., Santoso J. T. (2016). Hypomagnesemia is prevalent in patients undergoing gynecologic surgery by a gynecologic oncologist. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 26, 1320–1326. 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uludag E. Ü., Gözükara I. Ö., Kucur S. K., Ulug P., Özdegirmenci Ö., Erkaya S. (2014). Maternal magnesium level effect on preterm labor treatment. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 27, 1449–1453. 10.3109/14767058.2013.858688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendrell M., Martín N., Tejedor A., Ortiz J. T., Muxí À., Taurà P. (2016). Magnesium sulphate and (123)I-MIBG in pheochromocytoma: two useful techniques for a complicated disease. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. 63, 48–53. 10.1016/j.redar.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigil-De Gracia P., Ludmir J. (2015). The use of magnesium sulfate for women with severe preeclampsia or eclampsia diagnosed during the postpartum period. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 28, 2207–2209. 10.3109/14767058.2014.982529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. S., Ingersoll M., Meschter E., Bodea-Braescu A. V., Edwards R. K. (2014). Evaluating the side effects of treatment for preterm labor in a center that uses “high-dose” magnesium sulfate. Am. J. Perinatol. 31, 711–716. 10.1055/s-0033-1358770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G. K., Chan M. T., Boet R., Poon W. S., Gin T. (2006). Intravenous magnesium sulfate after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a prospective randomized pilot study. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 18, 142–148. 10.1097/00008506-200604000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M., Li X. K., Chen J. (2016). Effect of magnesium sulphate infusion on emergence agitation in patients undergoing esophageal carcinoma with general anesthesia: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 36, 1650–1654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M., Li X. K., Peng Y. (2017). Magnesium sulfate for postoperative complications in children undergoing tonsillectomies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Evid. Based Med. 10, 16–25. 10.1111/jebm.12230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Wang Y., Xu H., Yang J. (2018). Influence of magnesium sulfate on hemodynamic responses during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Medicine 97:e12747. 10.1097/MD.0000000000012747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.