Abstract

Background

Temporal analyses of death rates in the US have found a decreasing trend in all-cause and major cause-specific mortality rates.

Objectives

To determine mortality trends in Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC), a large insured population, and whether they differ from those of California and the US.

Methods

Trends in age-adjusted all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates from 2001 to 2016 were determined using data collected in KPSC and those derived through linkage with California State death files and were compared with trends in the US and California. Trends of race/ethnicity-specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates were also examined. Average annual percent changes (AAPC) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Results

From 2001 to 2016, the age-adjusted all-cause mortality rate per 100,000 person-years decreased significantly in KPSC (AAPC = −1.84, 95% CI = −2.95 to −0.71), California (AAPC = −1.60, 95% CI = −2.51 to −0.69) and the US (AAPC = −1.10, 95% CI = −1.78 to −0.42). Rates of 2 major causes of death, cancer and heart disease, also decreased significantly in the 3 populations. Differences in trends of age-adjusted all-cause mortality rates and the top 10 cause-specific mortality rates between KPSC and California or the US were not statistically significant at the 95% level. No significant difference was found in the trends of race/ethnicity-specific, sex-specific, or race/ethnicity- and sex-specific all-cause mortality rates between KPSC and California or the US.

Conclusion

Trends in age-adjusted mortality rates in this insured population were comparable to those of the US and California.

Keywords: death rate, leading cause of death, mortality trend, race- and ethnicity-specific death rate, sex-specific death rate

INTRODUCTION

All-cause mortality rates have decreased steadily in the US in the past 3 decades, but the trends of this decrease differed by age, sex, and race/ethnicity.1,2 More recent trends in mortality caused by cardiovascular disease (CVD), heart disease, and stroke in the US between 2000 and 2014 indicate that the decline in death rates has slowed since 2011.3 However, there are large geographic variations in all-cause mortality and disease-specific mortality.4 Because mortality is an important indicator of population health, the overall and cause-specific mortality trends can inform health policy,5 allow the identification of modifiable factors,6–8 and guide the design of population-based and clinical care interventions.

Integrated health care delivery systems are associated with overall better adherence to evidence-based care guidelines, better survival rates, and reduced racial disparities.9–11 Advantages of integrated health systems are their ability to coordinate care and conduct large-scale and sustained care-improvement initiatives to emphasize prevention, improve disease outcomes, and reduce mortality.12,13 One example is the sepsis mortality reduction initiative in 21 hospitals of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC).14 The sepsis mortality rate at these KPNC hospitals declined from 24.6% to 11.5% in less than 3 years.14 The reported steeper reduction of heart disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality rates among KPNC enrollees compared with those of the US population15 could be related to the implementation of a large-scale hypertension prevention program.16

Lower age-adjusted mortality rates have been observed in Hispanic17–19 and Asian/Pacific Islander populations19 compared with that of non-Hispanic whites. Mortality rates were even lower for Hispanics than non-Hispanics after adjusting for annual family income.17 However, not all studies support these conclusions because of the differences in the populations being studied.17 For example, differences in mortality between Hispanics who immigrated to another country vs those who did not were noted.20–24 In Southern California, the growth of Hispanic and Asian populations in the past 2 decades has been substantial. Thus, the advantage in mortality of the 2 populations could favorably affect the overall mortality rates of Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) enrollees if the mortality advantage does prevail among Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander populations.

Although absolute values of mortality rates are important, temporal trends in mortality are extremely informative because they could reflect changes of individual, organizational, or societal factors, including individual behaviors, medical practice (eg, change of practice guidelines or introduction of new treatments), medical technology, and the environment where people live. For example, cancer screenings can influence cancer mortality rates, and more advanced drug treatment can have an impact on the mortality rates owing to heart disease. In this study, both mortality rates and trends between 2001 and 2016 were studied for KPSC Health Plan enrollees. However, given the ethnic diversity of the KPSC and California populations compared with that of the US, we focused on mortality trends rather than the absolute values of mortality rates when the 3 populations (KPSC, CA, and the US) were compared. More specifically, the goals of this study were to 1) examine the age-adjusted mortality rates and trends of KPSC Health Plan enrollees; 2) study the age-adjusted sex- and race/ethnicity-specific mortality rates and the trends of all-cause mortality and the leading causes of mortality among the Health Plan enrollees; and 3) compare the age-adjusted overall and sex- and race/ethnicity-specific mortality trends and cause-specific mortality trends between KPSC and California and between KPSC and the US during the study period.

METHODS

Study Setting and Data Sources

KPSC is an integrated health care organization that currently serves approximately 4.6 million enrollees, about 19% of the population in Southern California. The demographics and socioeconomic status including race/ethnic composition of the enrollees are representative of those living in the region.25

Date of birth, sex, and race/ethnicity were collected administratively as part of Health Plan enrollment and/or patient care. Race and ethnicity information was based on a combination of administrative and self-reported data.26

The study protocol was approved by the KPSC institutional review board.

Study Subjects and At-risk Person-Time

Health Plan enrollees up to 110 years of age who had more than 1 day of enrollment between 2001 and 2016 were included. Enrollees whose age was missing were excluded. Those who were older than age 110 years were also removed from the analysis because they represented a very small number of enrollees, and some may have had an incorrect date of birth. Enrollees whose sex was labeled “other” or “unknown” were also excluded.

For each enrollee, the total number of days enrolled was considered the at-risk time for each calendar year. The at-risk time started from the date when the enrollee joined KPSC or January 1, whichever occurred later. The at-risk time ended at the disenrollment from the Health Plan, date of death, or December 31, whichever occurred first. Gaps in enrollment of 45 days or shorter were bridged (ie, continuous enrollment was assumed) even if the gaps spanned 2 consecutive years. For example, an enrollee who joined KPSC on July 1, 2010; terminated enrollment on November 30, 2010; rejoined on January 1, 2011; and died on October 30, 2011, contributed 6 (instead of 5) and 10 months of at-risk time in 2010 and 2011, respectively. If an enrollee had multiple enrollment periods within a calendar year that were greater than 45 days apart, the lengths of these enrollment periods were summed and the total length was designated as the at-risk time contributed by the enrollee for that specific year.

For age-specific analyses, an enrollee could contribute to at-risk periods that belonged to different age groups. For example, an enrollee who turned 65 years of age on July 1 could contribute 6 months of at-risk time to the group aged 55 to 64 years and another 6 months to the group aged 65 to 74 years.

Finally, the individual-level age-, sex-, and year-specific at-risk times for each calendar year were combined to form the total at-risk person-time for that specific year. The same process was repeated for each calendar year between 2001 and 2016.

Mortality

The KPSC death records (in the Research Data Warehouse) were derived by identifying deaths that occurred at KPSC-owned facilities, outside facilities that submitted claims to KPSC, or deaths reported to the Health Plan. These records were supplemented by linking the enrollees with the decedents in the California Death Statistical Master Files (up to 2014), the California Comprehensive Death File (since 2015), the State Multiple Cause of Death File, the State Fetal Death Files, and the Social Security Administration (SSA) Death Master Files. The linkage process is described in Appendix 1.a All death records of Health Plan enrollees since 1988 are kept, including neonatal and fetal deaths.

The cause of death was determined by the underlying cause of death obtained from state death records. The state death records used the Tenth Revision of International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) for underlying cause of death since 1999. Thirty-three cause-of-death categories were identified using the classification defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Appendix 2a). The residual groups “all other diseases” (Item Number 29 in Appendix 2a) and “all other external causes” (Item Number 33 in Appendix 2a) were not included in the ranking process in which we selected the top 10 causes of deaths for each calendar year. In addition, we also examined all cardiovascular conditions by using ICD-10 codes I00–I99 between 2001 and 2016.

Although the linkage process described here is capable of capturing deaths after disenrollment, our intention was to estimate death rates during Health Plan enrollment. However, deaths that occurred 1 month after Health Plan disenrollment were considered, because the Health Plan coverage may not have been renewed for some of the patients who were under end-of-life care. For these patients, their at-risk periods were extended to the date of death. For example, if an enrollee disenrolled on June 30 and died on July 7, his/her at-risk window was expanded from January 1 to June 30 (on the basis of enrollment records) to January 1 to July 7 (on the basis of actual date of death).

Statistical Analysis

The overall, sex-stratified, and race/ethnicity-stratified age-adjusted mortality rates were calculated using the direct method27 and the projected year 2000 US population as the standard population (Appendix 3a). Enrollees with race/ethnicity other than non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, African American, and Asian/Pacific Islander (ie, Native American, Alaskan, other, or multiple) and those with unknown race/ethnicity were included in the analyses that were not specific to race/ethnicity.

For KPSC enrollees, we ranked the age-adjusted, cause-specific mortality rates for each calendar year. For California and the US populations, we obtained the rates only for those causes that were ranked at the top 10 in 2016 for KPSC enrollees. Deaths with unknown causes were removed from the cause-specific analyses. For each cause, we reported age-adjusted rates standardized to the projected year 2000 US population overall as well as stratified by race/ethnicity. The analyses of CVD mortality rates (defined as the sum of heart disease and cerebrovascular disease mortality rates) were limited to adults aged 45 years or older. For comparison, we included relevant age-adjusted mortality rates for the entire US and the State of California populations. The US and California mortality rates between 2001 and 2016 were derived from the CDC’s Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research CDC WONDER dataset (https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html). To estimate an average annual percentage change (AAPC) in mortality rates, we first calculated the annual percentage change in age-adjusted mortality rates of 2 consecutive years (ie, slope) on a log scale and then derived the geometric mean of the annual percentage changes and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs).28 For comparison of AAPCs from 2 populations, a Z-statistic was formed by dividing the difference in the 2 AAPCs and the standard error (SE) of the difference (ie, sqrt [SE12 + SE22], where sqrt is the square root and SE1 and SE2 are the standard errors of the 2 individual estimates). The analysis was performed on a log scale. A test was considered statistically significant if the p value was < 0.05.

Because all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates vary considerably by age and some specific causes of mortality are more relevant for adults, we conducted sensitivity analyses for overall and sex-specific all-cause mortality, and for overall cause-specific mortality for the top 10 causes by including only adult Health Plan enrollees who were 25 or more years of age.

RESULTS

The number of KPSC Health Plan enrollees increased from nearly 3.4 million in 2001 to almost 4.6 million in 2016 (Table 1). During the same period, the mean age increased from 34.8 to 38.2 years and the proportions of Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees increased (37% to 43% and 8% to 12%, respectively).

Table 1.

Sex, age, and race/ethnicity of KPSC enrollees

| Year | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size (N) | 3,394,681 | 3,597,242 | 3,789,911 | 4,566,649 |

| Male, % | 49 | 49 | 48 | 49 |

| Mean age,a y (SD) | 34.8 (21.4) | 35.9 (21.6) | 37.0 (22.1) | 38.2 (22.1) |

| Age group, y,a % | ||||

| 0–<1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1–4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 5–14 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 12 |

| 15–24 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 14 |

| 25–34 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 15 |

| 35–44 | 16 | 15 | 13 | 13 |

| 45–54 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 14 |

| 55–64 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 65–74 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| 75–84 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| ≥ 85 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||

| Unknown | 25 | 17 | 8 | 8 |

| Known | 75 | 83 | 92 | 92 |

| Distributionb | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 41 | 37 | 36 | 34 |

| Hispanic | 37 | 41 | 41 | 43 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 8 | 9 | 11 | 12 |

| African American | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 |

| Others | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

On December 31 of each year.

Among enrollees with known race/ethnicity.

KPSC = Kaiser Permanente Southern California; SD = standard deviation.

All-Cause Mortality

Age-Adjusted All-Cause Mortality

From 2001 to 2016, the age-adjusted, all-cause mortality rate per 100,000 person-years in KPSC decreased from 684 to 521 (AAPC −1.84, 95% CI −2.95 to −0.71; Table 2). During the same period, the corresponding rates in the US and California decreased from 859 to 729 (AAPC = −1.10, 95%, CI = −1.78 to −0.42) and from 783 to 617 (AAPC = −1.60, 95% CI = −2.51 to −0.69), respectively. The differences in trends between KPSC and California and between KPSC and the US were not statistically significant at the 95% level.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted mortality rates (per 100,000 person-years), overall and by sex for KPSC, California, and US, 2001–2016

| Year | KPSC | California | US | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

| 2001 | 822 | 576 | 684 | 929 | 669 | 783 | 1035 | 726 | 859 |

| 2002 | 801 | 565 | 668 | 915 | 656 | 770 | 1031 | 724 | 856 |

| 2003 | 810 | 582 | 683 | 912 | 655 | 768 | 1010 | 715 | 844 |

| 2004 | 776 | 568 | 660 | 869 | 627 | 734 | 973 | 691 | 814 |

| 2005 | 784 | 556 | 657 | 866 | 622 | 731 | 972 | 692 | 815 |

| 2006 | 751 | 543 | 636 | 851 | 611 | 718 | 944 | 672 | 792 |

| 2007 | 716 | 534 | 616 | 818 | 588 | 692 | 923 | 658 | 775 |

| 2008 | 693 | 515 | 594 | 797 | 580 | 678 | 919 | 660 | 775 |

| 2009 | 677 | 491 | 574 | 776 | 558 | 656 | 891 | 637 | 750 |

| 2010 | 668 | 470 | 557 | 763 | 552 | 647 | 887 | 635 | 747 |

| 2011 | 650 | 465 | 548 | 755 | 547 | 641 | 875 | 632 | 741 |

| 2012 | 633 | 449 | 531 | 744 | 536 | 630 | 865 | 625 | 733 |

| 2013 | 630 | 455 | 532 | 747 | 533 | 630 | 864 | 624 | 732 |

| 2014 | 612 | 431 | 511 | 718 | 512 | 606 | 855 | 617 | 725 |

| 2015 | 613 | 460 | 529 | 734 | 527 | 622 | 863 | 624 | 733 |

| 2016 | 616 | 444 | 521 | 730 | 521 | 617 | 861 | 618 | 729 |

| AAPCa | −1.94 | −1.78 | −1.84 | −1.62 | −1.68 | −1.60 | −1.24 | −1.08 | −1.10 |

| LL | −2.94 | −3.35 | −2.95 | −2.54 | −2.62 | −2.51 | −1.90 | −1.78 | −1.78 |

| UL | −0.93 | −0.18 | −0.71 | −0.69 | −0.74 | −0.69 | −0.56 | −0.38 | −0.42 |

Comparison of AAPC within KPSC: male vs female: p > 0.05. Comparison of AAPC between KPSC and California/US for male/female/total: p > 0.05.

AAPC = average annual percentage change; KPSC = Kaiser Permanente Southern California; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

In KPSC, the AAPCs for males and females were −1.94 (95% CI = −2.94 to −0.93) and −1.78 (95% CI = −3.35 to −0.18), respectively, between 2001 and 2016 (Table 2). The trend estimates did not differ statistically from those of California and the US. In all 3 populations, mortality rates for males appeared consistently higher than those of females (Table 2). When the analyses were limited to adults aged 25 years or older, all the comparisons of AAPCs mentioned in this section yielded the same conclusions (data not shown).

Race/Ethnicity-Specific All-Cause Mortality

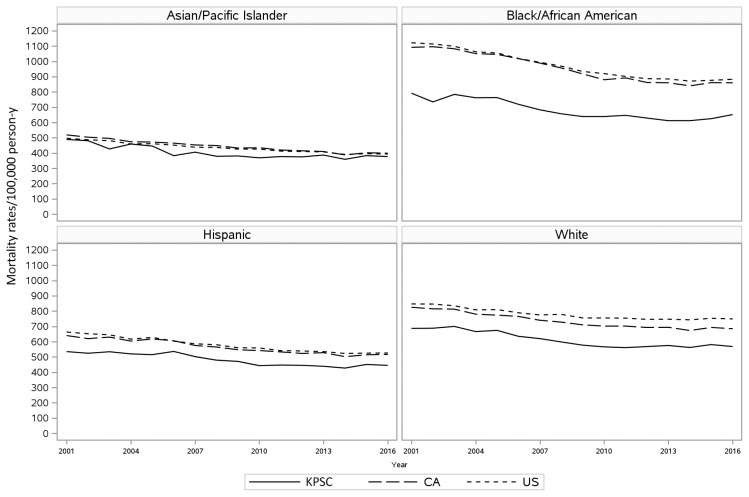

In KPSC, Asian/Pacific Islanders had the lowest age-adjusted mortality rates during the study period (377/100,000 person-years in 2016), followed by Hispanics (445/100,000), non-Hispanic whites (568/100,000) and African Americans (652/100,000; Figure 1, Supplemental Table E1a). For all racial/ethnic groups (non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, African Americans, and Asian/Pacific Islanders), the overall and sex-specific all-cause mortality rates in KPSC seemed to be consistently lower compared with those of California and the US (Figure 1, Supplemental Table E1a). Asian/Pacific Islanders seemed to have a more rapid decline in mortality rates between 2001 and 2016 (AAPC = −1.95, 95% CI = −5.27 to 1.49), compared with African Americans (AAPC = −1.36, 95% CI = −3.26 to 0.58), non-Hispanic whites (AAPC = −1.30, 95% CI = −2.67 to 0.08), and Hispanics (AAPC = −1.28, 95% CI = −7.60 to 5.48). However, the trend estimates in the 4 race/ethnicity populations were not significantly different at the 95% level (Supplemental Table E1a). No statistically significant difference was found in the trends of race/ethnicity-specific, or race/ethnicity- and sex-specific age-adjusted all-cause mortality rates between KPSC and California and between KPSC and the US (Supplemental Table E1a).

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted mortality rates by race/ethnicity in Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC), the US, and CA, 2001–2016.

Leading Causes of Mortality

Top 10 Leading Causes of Death

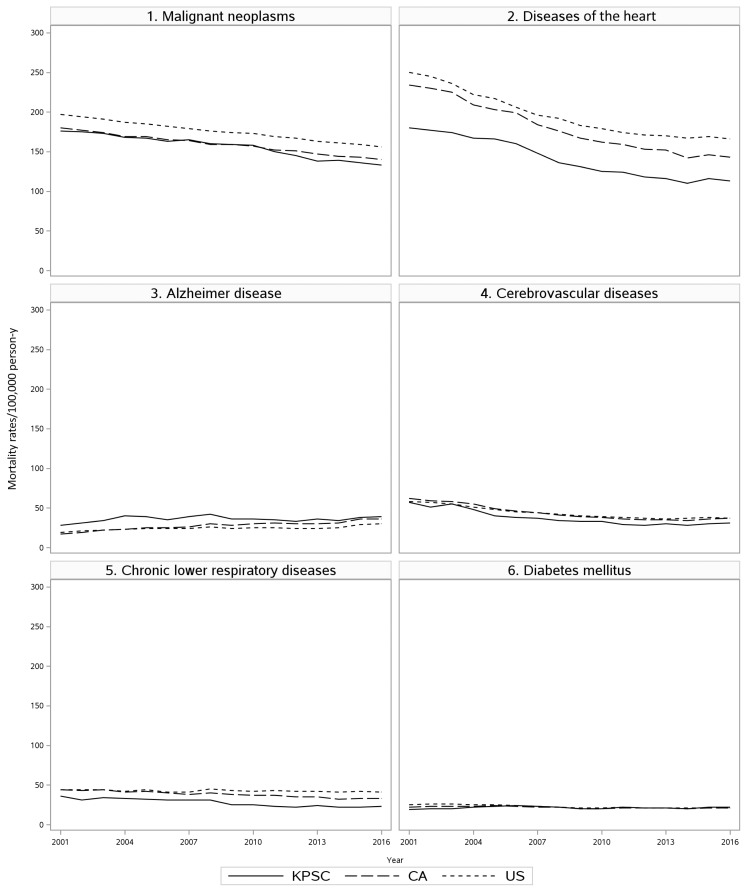

Supplemental Table E2a displays the top 10 causes of death in 2016 for KPSC and the corresponding mortality rates in California and the US. Cancer and heart disease were the leading causes of death between 2001 and 2016 for all 3 populations (KPSC, California, and the US; Supplemental Table E2a, Figure 2). During the last 10 years of the study period (2007 to 2016), the rank of the top 5 causes of death in KPSC remained the same (Supplemental Table E2a).

Figure 2.

Age-adjusted mortality rates for each of the top 6 causes of death in Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC), the US, and CA, 2001–2016.

At KPSC, cancer was the leading cause of death in 2016 with 133 deaths per 100,000 person-years. The second, third, and fourth leading causes of death were heart disease (113/100,000 person-years), Alzheimer disease (39/100,000 person-years), and cerebrovascular diseases (31/100,000 person-years), respectively. During the study period, age-adjusted mortality rates of cancer (AAPC = −1.87, 95% CI = −2.75 to −0.98), heart disease (AAPC = −3.18, 95% CI = −4.78 to −1.54), and influenza and pneumonia (AAPC = −7.08, 95% CI = −13.63 to −0.04) decreased significantly (Supplemental Table E2a). The decrease of mortality rate for cerebrovascular diseases from 57 to 31 per 100,000 person-years was impressive; however, it was not statistically significant (AAPC = −4.42, 95% CI = −8.67 to 0.02). Decreasing trends were observed for cancer, heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease in the US and California populations. A statistically significant increase in the Alzheimer disease mortality was observed in the US (AAPC = 2.91, 95% CI = 0.14 to 5.75) and California (AAPC = 4.80, 95% CI = 1.48 to 8.23) populations, but not in the KPSC population (AAPC = 1.82, 95% CI = −2.66 to 6.50). In 2016, Alzheimer disease was ranked as the sixth leading cause of death in the US and the third leading cause of death in California. No statistically significant difference was found in the trends of any age-adjusted cause-specific mortality rates between KPSC and California, or between KPSC and the US between 2001 and 2016 for the top 10 causes of death (Supplemental Table E2a). When the analyses were limited to adults 25 or more years of age, the comparisons of AAPC between KPSC and the US/California yielded the same conclusions (data not shown).

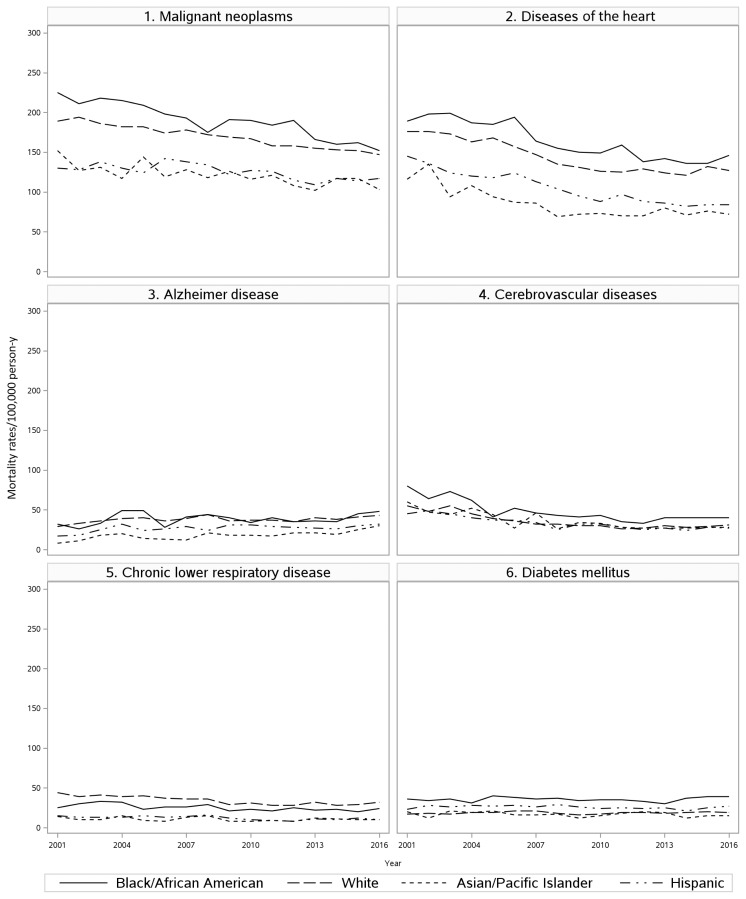

Top 10 Leading Causes of Mortality by Race/Ethnicity

In KPSC, African American enrollees had the highest age-adjusted cancer and heart disease mortality rates (152 and 146/100,000 person-years in 2016, respectively), followed by non-Hispanic whites (147 and 127/100,000 person-years in 2016, respectively) (Supplemental Table E3a). African American and non-Hispanic whites enrollees had higher mortality rates caused by Alzheimer disease, compared with Hispanics and Asian/Pacific Islanders in all of the years studied. African American enrollees also had the highest mortality rates for diabetes mellitus during the study period, followed by Hispanics. The mortality rates of chronic lower respiratory disease and accidents were highest among non-Hispanic white enrollees.

Figure 3 shows the age-adjusted mortality rates by race/ethnicity for each of the top 6 causes. The reduction in the rates of cancer mortality between 2001 and 2016 seemed to be larger in Asian/Pacific Islander (AAPC = −3.20; 95% CI = −8.81 to 2.76) and African Americans (AAPC −2.74, 95% CI −5.48 to 0.09), compared with those of Hispanics (AAPC = −0.93, 95% CI = −4.03 to 2.28) and non-Hispanic whites (AAPC = −1.67, 95% CI = −2.88 to −0.45); nevertheless, the differences were not statistically significant (Supplemental Table E3a). Age-adjusted mortality owing to Alzheimer disease seemed to increase the most for Asian/Pacific Islander (AAPC = 6.06, 95% CI = −5.71 to 19.31) compared with those of Hispanics (AAPC = 2.70, 95% CI = −5.59 to 11.73), non-Hispanic whites (AAPC = 2.14, 95% CI = −2.56 to 7.07) and African Americans (AAPC = −0.62, 95% CI = −13.82 to 14.61), respectively. However, there was no statistically significant difference.

Figure 3.

Age-adjusted mortality rates by race/ethnicity for each of the top 6 causes of death in Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPCS), 2001–2016.

Trends of age-adjusted CVD mortality rates were similar to those of heart disease (Supplemental Table E4a).

DISCUSSION

The current study was conducted in a large cohort of Health Plan enrollees over 16 years. Our findings suggest that despite the fact that the age-adjusted mortality rates declined significantly in all 3 populations (KPSC, CA, and the US), the trends of age-adjusted all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates in KPSC were comparable to those of California and the US. Similarly, when the analyses were stratified by sex and race/ethnicity, the trends of age-adjusted mortality rates in KPSC remained comparable to those of California and the US.

The decline in mortality from heart disease may be attributed to changes in risk factors and progress in treatment. The decreasing prevalence of important cardiovascular risk factors, including cigarette smoking, elevated total cholesterol, high systolic blood pressure, and physical inactivity, were reported to account for almost half of the decrease in death caused by coronary artery disease.29 Improvement in secondary prevention therapies as well as timely revascularization via coronary artery bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention also contributed to the reduction in cardiovascular mortality.30 Unfortunately, this trend is offset by major increases in the prevalence of obesity and diabetes, causing a deceleration in the rate of decline between 2011 and 2014 for all cardiovascular deaths.3 The slowing in rate decline is consistent with the data we reported for the entire US population. The trend in decreasing cardiovascular mortality rate also seemed to slow for KPSC enrollees and California residents since 2011.

The decline in cancer mortality could largely be attributed to screening31,32 and more advanced treatment.33 Other factors affecting cancer mortality included smoking,34 unhealthy diet,35 and obesity.36 The decline in cancer mortality in the US was reported to be stable between 2000 and 2014 by Sidney et al.3 The same pattern was observed for KPSC enrollees and California residents during the same period.

Although studies have shown associations between air pollution and respiratory and allergic conditions37 and air quality has been poor in California because of traffic and wildfire-related pollution,38 California residents experienced lower mortality rates because of chronic lower respiratory tract diseases compared with those of the US in recent years (Supplemental Table E2a). Research based on adult Californians who responded to the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 2011 reported an increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among white and black residents, compared with Hispanic residents.39 In KPSC, the mortality rates of chronic lower respiratory diseases in non-Hispanic whites and African American populations were higher compared with those of Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander.

Alzheimer disease surpassed chronic lower respiratory diseases in 2004 and cerebrovascular disease in 2007, and became the third leading cause of death among KPSC enrollees. The increasing trend of morality rates of Alzheimer disease was significant in California and the US populations, but not in KPSC. The increase of Alzheimer disease death rates could be attributed to older age at the time of deaths. When advanced medicine prolongs lives and reduces mortality caused by cancer and CVD, people are more likely to die of Alzheimer disease or its complications. Our results, based on KPSC enrollees, showed that the mortality rate due to Alzheimer disease was highest in African American enrollees, followed by non-Hispanic whites enrollees. This result is consistent with what was reported by Taylor et al.40 Patients with Alzheimer disease typically die because of comorbidities (eg, infections), poor functional status, lack of nutrition, delirium, and severe cognitive impairment.41–44

Our findings also suggest that in the KPSC population, Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees had lower age-adjusted mortality rates, compared with those of African Americans and non-Hispanic white enrollees. This finding is similar to that of a meta-analysis in which the authors reported that Hispanics had lower overall mortality than did non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks, but overall higher risk of mortality than did Asian Americans.45 The mortality advantage of Hispanics and Asian/Pacific Islanders may be partially attributable to the healthy immigrant effect,20–22 in which those who choose to migrate to another country are in general healthier than those who decide to stay. However, other studies found only weak evidence to support such a hypothesis.21,23 Another potential explanation could be the “salmon bias” effect, or reverse immigration hypothesis, in which selective immigrants, especially the less healthy ones, returned to their countries of origin.24 However, authors of other studies believed that the evidence was not enough46 or could explain only part of the advantages.47

The observed lower all-cause and race/ethnicity-specific mortality rates at KPSC compared with those of California and the US should be interpreted with caution. It is very likely that the advantage in mortality rates is attributable to the better coordination and delivery of care within the integrated health care system. However, it may also be possible that people who joined KPSC were healthier than other local residents because of more stable insurance coverage or healthier lifestyles.

Similar to age-adjusted all-cause mortality, the age-adjusted mortality rates caused by cancer and heart disease also varied significantly among racial/ethnic groups in the KPSC population. Our results are consistent with the US national data between 2010 and 2014 showing that African Americans and non-Hispanic whites had the higher CVD mortality rates (African Americans being the highest and non-Hispanic whites the second highest) compared with those of Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander.3 A study that evaluated the racial/ethnic differences in the risk of coronary heart disease in a cohort of 1.3 million KPNC enrollees showed that compared with whites, blacks, Latinos, and Asians all had a lower risk of coronary heart disease across all clinical risk categories, with the exception of blacks with prior coronary heart disease and no diabetes having higher risk than whites.48 It is unclear whether or not the lower risk of coronary heart disease may lead to a lower rate of CVD mortality rates in this population.

Some limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, one of the factors determining the quality of linkage is the uniqueness of identification of individuals being linked. A higher level of uniqueness is associated with more accurate linkage. The use of common Latino names (surnames and first names) and Asian/Pacific Islander surnames could lead to more false-positive matches and thus affect our ability to identify deaths of Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees. However, when we examined the success rates among 266,398 deaths documented within the KPSC system between 1988 and 2016 for each racial/ethnic subpopulation, the percentage of deaths not found by the linkage process did not differ much. Specifically, the rates were 2.5% for Hispanic, 1.4% for Asian/Pacific Islander, 1.3% for African Americans, and 0.8% for non-Hispanic whites. This is at least partially owing to a feature provided by the linkage software that takes care of the level of uniqueness of matching variables.

Second, deaths occurring outside California may not be completely captured, particularly after 2011, when a law was established that prohibited the SSA from disclosing state death records that the SSA receives through its contracts with the states. Given the size of the KPSC population and the lengthy study period, it was not feasible to identify deaths through the National Death Index. However, it is expected that most of the deaths outside California were reported to KPSC for active enrollees by family members, caregivers, doctors from medical facilities outside California, or law enforcement officers.

Third, the cause of death was missing for 27,187 (6.4%) of all deaths. These included deaths that were reported to KPSC or those that were derived through the linkage with SSA records but were not identified through the linkage process with the death records from the State of California. Therefore, the cause-specific death rates could be slightly underestimated.

Fourth, underlying causes of death may be underestimated for certain causes. For example, James et al49 found evidence that supported a larger number of deaths attributable to Alzheimer disease than what was actually reported.

Fifth, the change of underlying cause of death code from ICD-9 to ICD-10 in 1999 may affect the analyses related to cause of death. Anderson et al50 studied the influence of migration from ICD-9 to ICD-10 and concluded that the ranking of leading causes of death was substantially affected for some causes of death.

Sixth, the race/ethnicity information was missing for about 20% of the enrollees in 2001 to 2004 and was reduced to about 6% or 7% in recent years. Finally, although variation in all-cause mortality or cause-specific mortality exists in each ethnic group,18,51,52 our study did not stratify the analyses by subethnic groups.

CONCLUSION

The trends in age-adjusted mortality rates in this insured population are comparable to those of California and the US. The overall age-adjusted all-cause mortality rates are decreasing, although the cause-specific rates of certain diseases such as Alzheimer disease remained flat or increased during this period.

Supplementary Information

Table E1.

Age-adjusted mortality rates (per 100,000 person-years) by race/ethnicity and sex in KPSC, California (CA), and US, 2001–2016.

| Year | Non-Hispanic white | Hispanic | African American | Asian/Pacific islander | Overall | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |||

| KPSC | 2001 | 819 | 585 | 687 | 644 | 452 | 535 | 962 | 674 | 792 | 609 | 388 | 489 | 684 |

| 2002 | 812 | 593 | 688 | 635 | 438 | 524 | 939 | 599 | 735 | 561 | 411 | 481 | 668 | |

| 2003 | 814 | 610 | 700 | 632 | 455 | 534 | 987 | 648 | 784 | 514 | 351 | 427 | 683 | |

| 2004 | 777 | 578 | 666 | 594 | 459 | 520 | 962 | 630 | 762 | 548 | 381 | 459 | 660 | |

| 2005 | 794 | 579 | 674 | 627 | 424 | 515 | 914 | 661 | 763 | 548 | 361 | 446 | 657 | |

| 2006 | 737 | 554 | 635 | 644 | 448 | 536 | 874 | 616 | 719 | 471 | 312 | 383 | 636 | |

| 2007 | 713 | 545 | 620 | 595 | 428 | 502 | 804 | 601 | 683 | 476 | 347 | 406 | 616 | |

| 2008 | 687 | 526 | 598 | 564 | 408 | 479 | 814 | 556 | 657 | 467 | 306 | 379 | 594 | |

| 2009 | 685 | 489 | 577 | 546 | 411 | 471 | 778 | 550 | 639 | 446 | 328 | 381 | 574 | |

| 2010 | 677 | 479 | 566 | 538 | 367 | 443 | 771 | 554 | 639 | 449 | 304 | 369 | 557 | |

| 2011 | 654 | 485 | 561 | 540 | 371 | 447 | 816 | 540 | 647 | 453 | 316 | 377 | 548 | |

| 2012 | 669 | 486 | 568 | 552 | 361 | 445 | 756 | 543 | 629 | 456 | 309 | 375 | 531 | |

| 2013 | 680 | 489 | 575 | 520 | 374 | 439 | 737 | 530 | 612 | 450 | 337 | 387 | 532 | |

| 2014 | 675 | 468 | 562 | 505 | 363 | 427 | 750 | 523 | 612 | 420 | 310 | 359 | 511 | |

| 2015 | 665 | 511 | 581 | 538 | 381 | 451 | 763 | 533 | 625 | 438 | 340 | 383 | 529 | |

| 2016 | 662 | 490 | 568 | 490 | 374 | 445 | 817 | 544 | 652 | 458 | 312 | 377 | 521 | |

| AAPC* | −1.45 | −1.26 | −1.30 | −1.93 | −1.36 | −1.28 | −1.19 | −1.54 | −1.36 | −2.06 | −1.90 | −1.95 | −1.84 | |

| LL | −2.82 | −3.26 | −2.67 | −4.28 | −3.80 | −7.60 | −3.51 | −4.02 | −3.26 | −5.02 | −6.62 | −5.27 | −2.95 | |

| UL | −0.07 | 0.78 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 1.14 | 5.48 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.99 | 3.06 | 1.49 | −0.71 | |

| CA | 2001 | 970 | 709 | 825 | 777 | 534 | 640 | 1339 | 913 | 1092 | 635 | 432 | 519 | 783 |

| 2002 | 960 | 700 | 815 | 752 | 515 | 620 | 1335 | 918 | 1096 | 614 | 420 | 504 | 770 | |

| 2003 | 955 | 699 | 813 | 764 | 523 | 630 | 1304 | 911 | 1083 | 605 | 414 | 496 | 768 | |

| 2004 | 912 | 674 | 780 | 735 | 500 | 604 | 1268 | 885 | 1051 | 581 | 394 | 474 | 734 | |

| 2005 | 904 | 667 | 774 | 753 | 510 | 618 | 1263 | 875 | 1046 | 580 | 393 | 472 | 731 | |

| 2006 | 896 | 656 | 765 | 732 | 504 | 606 | 1219 | 859 | 1018 | 566 | 391 | 465 | 718 | |

| 2007 | 865 | 636 | 740 | 689 | 480 | 575 | 1178 | 840 | 989 | 554 | 377 | 453 | 692 | |

| 2008 | 849 | 627 | 728 | 673 | 476 | 565 | 1127 | 821 | 957 | 544 | 379 | 449 | 678 | |

| 2009 | 831 | 608 | 710 | 658 | 457 | 547 | 1094 | 779 | 918 | 526 | 364 | 433 | 656 | |

| 2010 | 818 | 605 | 702 | 654 | 452 | 542 | 1034 | 757 | 880 | 526 | 368 | 435 | 647 | |

| 2011 | 819 | 602 | 702 | 637 | 448 | 533 | 1051 | 765 | 892 | 503 | 357 | 420 | 641 | |

| 2012 | 811 | 594 | 693 | 622 | 441 | 523 | 1017 | 736 | 862 | 501 | 351 | 415 | 630 | |

| 2013 | 812 | 593 | 694 | 634 | 441 | 528 | 1029 | 723 | 860 | 500 | 343 | 410 | 630 | |

| 2014 | 788 | 573 | 673 | 605 | 418 | 502 | 1003 | 708 | 840 | 466 | 328 | 388 | 606 | |

| 2015 | 809 | 592 | 693 | 617 | 428 | 514 | 1019 | 728 | 861 | 480 | 342 | 402 | 622 | |

| 2016 | 800 | 584 | 685 | 621 | 429 | 517 | 1032 | 721 | 860 | 478 | 338 | 399 | 617 | |

| AAPC* | −1.30 | −1.31 | −1.25 | −1.53 | −1.49 | −1.45 | −1.76 | −1.59 | −1.61 | −1.92 | −1.66 | −1.78 | −1.60 | |

| LL | −2.15 | −2.17 | −2.10 | −2.86 | −2.76 | −2.73 | −2.95 | −2.59 | −2.65 | −3.13 | −2.87 | −2.88 | −2.51 | |

| UL | −0.43 | −0.44 | −0.40 | −0.18 | −0.20 | −0.16 | −0.56 | −0.59 | −0.57 | −0.70 | −0.44 | −0.66 | −0.69 | |

| US | 2001 | 1019 | 717 | 847 | 809 | 547 | 663 | 1400 | 932 | 1122 | 606 | 416 | 497 | 859 |

| 2002 | 1017 | 717 | 846 | 800 | 536 | 652 | 1385 | 928 | 1114 | 596 | 407 | 487 | 856 | |

| 2003 | 997 | 710 | 835 | 784 | 534 | 645 | 1367 | 914 | 1099 | 583 | 405 | 481 | 844 | |

| 2004 | 963 | 687 | 808 | 750 | 510 | 617 | 1321 | 885 | 1063 | 557 | 389 | 460 | 814 | |

| 2005 | 962 | 691 | 810 | 771 | 514 | 628 | 1306 | 879 | 1055 | 562 | 386 | 461 | 815 | |

| 2006 | 936 | 672 | 789 | 732 | 500 | 604 | 1267 | 846 | 1019 | 546 | 382 | 452 | 792 | |

| 2007 | 918 | 661 | 775 | 711 | 484 | 586 | 1233 | 826 | 994 | 528 | 371 | 438 | 775 | |

| 2008 | 920 | 665 | 779 | 695 | 485 | 580 | 1195 | 810 | 969 | 520 | 374 | 437 | 775 | |

| 2009 | 894 | 643 | 755 | 676 | 466 | 560 | 1151 | 781 | 934 | 510 | 363 | 426 | 750 | |

| 2010 | 893 | 643 | 755 | 678 | 463 | 559 | 1132 | 771 | 920 | 513 | 361 | 426 | 747 | |

| 2011 | 887 | 645 | 754 | 647 | 453 | 541 | 1098 | 760 | 902 | 493 | 353 | 413 | 741 | |

| 2012 | 876 | 638 | 746 | 644 | 453 | 539 | 1086 | 742 | 887 | 486 | 351 | 410 | 733 | |

| 2013 | 877 | 638 | 747 | 640 | 449 | 535 | 1083 | 741 | 885 | 490 | 345 | 408 | 732 | |

| 2014 | 872 | 634 | 743 | 627 | 438 | 523 | 1060 | 731 | 871 | 464 | 333 | 391 | 725 | |

| 2015 | 881 | 644 | 753 | 629 | 438 | 525 | 1070 | 731 | 876 | 469 | 340 | 396 | 733 | |

| 2016 | 880 | 637 | 749 | 632 | 436 | 526 | 1081 | 734 | 883 | 467 | 337 | 394 | 729 | |

| AAPC* | −0.99 | −0.80 | −0.83 | −1.67 | −1.53 | −1.56 | −1.73 | −1.60 | −1.61 | −1.76 | −1.42 | −1.56 | −1.10 | |

| LL | −1.66 | −1.54 | −1.52 | −2.77 | −2.36 | −2.47 | −2.49 | −2.27 | −2.30 | −2.80 | −2.24 | −2.42 | −1.78 | |

| UL | −0.31 | −0.05 | −0.13 | −0.55 | −0.68 | −0.64 | −0.97 | −0.93 | −0.91 | −0.71 | −0.58 | −0.70 | −0.42 | |

Comparison of AAPC within KPSC: 4 race/ethnic groups: p > 0.05; male vs. female within each race/ethnic group: p > 0.05. Comparison of AAPC between KPSC and CA/US for male/female/total within each race/ethnic group: p > 0.05.

AAPC = average annual percent change; KPSC = Kaiser Permanente Southern California; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

Table E2.

Age-adjusted mortality rates (per 100,000 person-years) for the top 10 causes for all race/ethnicity in KPSC, California (CA) and US, 2001–2016.

| Year | Malignant neoplasms | Diseases of the heart | Alzheimer’s disease | Cerebrovascular diseases | Chronic lower respiratory disease | Diabetes mellitus | Accidents (unintentional injuries) | Essential hypertension and hypertensive renal disease | Influenza and pneumonia | Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPSC | 2001 | 176 | 180 | 28 | 57 | 36 | 19 | 15 | 8 | 26 | 9 |

| 2002 | 175 | 177 | 31 | 51 | 31 | 20 | 18 | 7 | 28 | 8 | |

| 2003 | 173 | 174 | 34 | 55 | 34 | 20 | 19 | 8 | 29 | 8 | |

| 2004 | 168 | 167 | 40 | 48 | 33 | 22 | 18 | 9 | 22 | 6 | |

| 2005 | 167 | 166 | 39 | 40 | 32 | 23 | 19 | 9 | 23 | 7 | |

| 2006 | 163 | 160 | 35 | 38 | 31 | 24 | 20 | 9 | 19 | 6 | |

| 2007 | 165 | 148 | 39 | 37 | 31 | 23 | 19 | 8 | 14 | 7 | |

| 2008 | 160 | 136 | 42 | 34 | 31 | 22 | 18 | 9 | 13 | 7 | |

| 2009 | 159 | 131 | 36 | 33 | 25 | 20 | 17 | 10 | 13 | 6 | |

| 2010 | 158 | 125 | 36 | 33 | 25 | 20 | 16 | 8 | 12 | 6 | |

| 2011 | 150 | 124 | 35 | 29 | 23 | 22 | 17 | 10 | 12 | 7 | |

| 2012 | 145 | 118 | 33 | 28 | 22 | 21 | 17 | 11 | 10 | 6 | |

| 2013 | 138 | 116 | 36 | 30 | 24 | 21 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 7 | |

| 2014 | 139 | 110 | 34 | 28 | 22 | 20 | 17 | 12 | 10 | 7 | |

| 2015 | 136 | 116 | 38 | 30 | 22 | 22 | 17 | 11 | 10 | 8 | |

| 2016 | 133 | 113 | 39 | 31 | 23 | 22 | 18 | 10 | 10 | 7 | |

| AAPC* | −1.87 | −3.18 | 1.82 | −4.42 | −3.17 | 0.88 | 1.22 | 1.61 | −7.08 | −1.48 | |

| LL* | −2.75 | −4.78 | −2.66 | −8.67 | −7.38 | −1.84 | −1.88 | −3.38 | −13.63 | −6.44 | |

| UL* | −0.98 | −1.54 | 6.50 | 0.02 | 1.25 | 3.66 | 4.42 | 6.85 | −0.04 | 3.74 | |

| CA | 2001 | 180 | 234 | 17 | 62 | 44 | 22 | 25 | 8 | 28 | 12 |

| 2002 | 177 | 230 | 19 | 59 | 43 | 23 | 30 | 8 | 28 | 12 | |

| 2003 | 174 | 225 | 22 | 58 | 44 | 23 | 31 | 9 | 27 | 12 | |

| 2004 | 169 | 209 | 23 | 55 | 41 | 23 | 31 | 9 | 24 | 11 | |

| 2005 | 169 | 203 | 25 | 49 | 42 | 24 | 32 | 10 | 24 | 11 | |

| 2006 | 165 | 199 | 25 | 46 | 40 | 23 | 32 | 10 | 23 | 11 | |

| 2007 | 164 | 184 | 26 | 44 | 38 | 22 | 32 | 10 | 20 | 11 | |

| 2008 | 159 | 176 | 30 | 41 | 40 | 22 | 30 | 10 | 19 | 11 | |

| 2009 | 159 | 167 | 28 | 39 | 38 | 20 | 29 | 10 | 18 | 11 | |

| 2010 | 157 | 162 | 30 | 38 | 37 | 20 | 28 | 10 | 16 | 11 | |

| 2011 | 152 | 159 | 31 | 36 | 37 | 21 | 28 | 11 | 17 | 12 | |

| 2012 | 151 | 153 | 30 | 35 | 35 | 21 | 28 | 12 | 15 | 12 | |

| 2013 | 147 | 152 | 30 | 35 | 35 | 21 | 29 | 12 | 17 | 12 | |

| 2014 | 144 | 142 | 31 | 34 | 32 | 20 | 29 | 11 | 15 | 12 | |

| 2015 | 143 | 146 | 36 | 36 | 33 | 21 | 31 | 12 | 15 | 13 | |

| 2016 | 140 | 143 | 36 | 37 | 33 | 21 | 32 | 12 | 14 | 12 | |

| AAPC* | −1.68 | −3.32 | 4.80 | −3.52 | −2.00 | −0.39 | 1.51 | 2.55 | −4.89 | −0.09 | |

| LL* | −2.23 | −4.71 | 1.48 | −5.57 | −4.08 | −2.47 | −1.20 | −0.29 | −8.54 | −2.33 | |

| UL* | −1.13 | −1.91 | 8.23 | −1.43 | 0.12 | 1.74 | 4.29 | 5.48 | −1.09 | 2.20 | |

| US | 2001 | 197 | 250 | 19 | 58 | 44 | 25 | 36 | 7 | 22 | 10 |

| 2002 | 194 | 245 | 21 | 57 | 44 | 26 | 37 | 7 | 23 | 9 | |

| 2003 | 191 | 236 | 22 | 55 | 44 | 26 | 38 | 8 | 23 | 9 | |

| 2004 | 187 | 222 | 23 | 51 | 42 | 25 | 38 | 8 | 20 | 9 | |

| 2005 | 185 | 217 | 24 | 48 | 44 | 25 | 40 | 8 | 21 | 9 | |

| 2006 | 182 | 206 | 24 | 45 | 41 | 24 | 40 | 8 | 18 | 9 | |

| 2007 | 179 | 196 | 24 | 44 | 41 | 23 | 40 | 8 | 17 | 9 | |

| 2008 | 176 | 192 | 26 | 42 | 45 | 22 | 39 | 8 | 18 | 9 | |

| 2009 | 174 | 183 | 24 | 40 | 43 | 21 | 38 | 8 | 17 | 9 | |

| 2010 | 173 | 179 | 25 | 39 | 42 | 21 | 38 | 8 | 15 | 9 | |

| 2011 | 169 | 174 | 25 | 38 | 43 | 22 | 39 | 8 | 16 | 10 | |

| 2012 | 167 | 171 | 24 | 37 | 42 | 21 | 39 | 8 | 14 | 10 | |

| 2013 | 163 | 170 | 24 | 36 | 42 | 21 | 39 | 9 | 16 | 10 | |

| 2014 | 161 | 167 | 25 | 37 | 41 | 21 | 41 | 8 | 15 | 10 | |

| 2015 | 159 | 169 | 29 | 38 | 42 | 21 | 43 | 9 | 15 | 11 | |

| 2016 | 156 | 166 | 30 | 37 | 41 | 21 | 47 | 9 | 14 | 11 | |

| AAPC* | −1.56 | −2.75 | 2.91 | −3.04 | −0.55 | −1.21 | 1.73 | 1.50 | −3.38 | 0.53 | |

| LL | −1.81 | −3.72 | 0.14 | −4.47 | −2.56 | −2.73 | 0.16 | −1.61 | −7.71 | −1.81 | |

| UL | −1.30 | −1.77 | 5.75 | −1.58 | 1.50 | 0.34 | 3.33 | 4.70 | 1.15 | 2.93 |

Comparison of AAPC between KPSC and CA/US for each of the 10 top causes: p > 0.05.

AAPC = average annual percent change; KPSC = Kaiser Permanente Southern California; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

Table E3.

Age-adjusted mortality rates for the top 10 causes by race/ethnicity in KPSC, 2001–2016.

| Year | Malignant neoplasms | Diseases of the heart | Alzheimer’s disease | Cerebrovascular diseases | Chronic lower respiratory diseases | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW | HI | AA | API | NHW | HI | AA | API | NHW | HI | AA | API | NHW | HI | AA | API | NHW | HI | AA | API | |

| 2001 | 189 | 130 | 225 | 152 | 176 | 145 | 189 | 116 | 29 | 17 | 32 | 8 | 55 | 45 | 80 | 60 | 44 | 15 | 25 | 14 |

| 2002 | 194 | 128 | 211 | 127 | 176 | 136 | 198 | 135 | 33 | 18 | 26 | 11 | 48 | 49 | 64 | 47 | 39 | 13 | 30 | 10 |

| 2003 | 186 | 138 | 218 | 131 | 173 | 124 | 199 | 94 | 36 | 25 | 33 | 18 | 55 | 45 | 73 | 44 | 41 | 13 | 33 | 10 |

| 2004 | 182 | 130 | 215 | 117 | 163 | 120 | 187 | 108 | 39 | 32 | 49 | 20 | 45 | 40 | 62 | 52 | 39 | 13 | 32 | 15 |

| 2005 | 182 | 124 | 209 | 144 | 168 | 118 | 185 | 94 | 40 | 24 | 49 | 14 | 39 | 37 | 41 | 44 | 40 | 15 | 23 | 9 |

| 2006 | 174 | 142 | 198 | 119 | 157 | 124 | 194 | 87 | 36 | 26 | 28 | 13 | 36 | 37 | 52 | 27 | 37 | 13 | 26 | 8 |

| 2007 | 178 | 138 | 193 | 128 | 147 | 113 | 164 | 86 | 39 | 29 | 41 | 12 | 32 | 34 | 46 | 46 | 36 | 14 | 26 | 13 |

| 2008 | 172 | 134 | 175 | 118 | 135 | 104 | 155 | 69 | 44 | 24 | 44 | 21 | 32 | 25 | 43 | 26 | 36 | 16 | 29 | 15 |

| 2009 | 169 | 122 | 191 | 126 | 131 | 95 | 150 | 72 | 36 | 31 | 40 | 18 | 30 | 32 | 41 | 34 | 29 | 12 | 21 | 8 |

| 2010 | 167 | 127 | 190 | 116 | 126 | 88 | 149 | 73 | 37 | 31 | 34 | 18 | 30 | 32 | 43 | 33 | 31 | 10 | 23 | 8 |

| 2011 | 158 | 126 | 184 | 121 | 125 | 97 | 159 | 70 | 37 | 29 | 40 | 17 | 26 | 28 | 35 | 28 | 28 | 9 | 21 | 9 |

| 2012 | 158 | 115 | 190 | 108 | 129 | 88 | 138 | 70 | 35 | 28 | 35 | 21 | 27 | 25 | 33 | 27 | 28 | 8 | 25 | 8 |

| 2013 | 155 | 109 | 166 | 102 | 124 | 86 | 142 | 80 | 40 | 27 | 36 | 21 | 30 | 27 | 40 | 27 | 32 | 11 | 22 | 12 |

| 2014 | 153 | 117 | 160 | 117 | 121 | 82 | 136 | 71 | 38 | 26 | 35 | 19 | 28 | 24 | 40 | 27 | 28 | 10 | 23 | 11 |

| 2015 | 152 | 114 | 162 | 117 | 132 | 84 | 136 | 76 | 41 | 30 | 45 | 25 | 29 | 28 | 40 | 28 | 29 | 12 | 20 | 10 |

| 2016 | 147 | 117 | 152 | 103 | 127 | 84 | 146 | 72 | 43 | 32 | 48 | 30 | 31 | 27 | 40 | 28 | 32 | 10 | 24 | 10 |

| AAPC* | −1.67 | −0.93 | −2.74 | −3.20 | −2.25 | −3.81 | −1.96 | −4.21 | 2.14 | 2.70 | −0.62 | 6.06 | −4.26 | −4.16 | −6.02 | −9.21 | −2.53 | −4.14 | −1.73 | −7.35 |

| LL | −2.88 | −4.03 | −5.48 | −8.81 | −4.39 | −6.59 | −5.52 | −11.41 | −2.56 | −5.59 | −13.82 | −5.71 | −9.17 | −10.44 | −14.41 | −22.84 | −7.07 | −30.95 | −10.61 | −23.18 |

| UL | −0.45 | 2.28 | 0.09 | 2.76 | −0.07 | −0.94 | 1.74 | 3.56 | 7.07 | 11.73 | 14.61 | 19.31 | 0.92 | 2.57 | 3.21 | 6.84 | 2.24 | 33.07 | 8.03 | 11.74 |

| Year | Diabetes mellitus | Accidents (unintentional injuries) | Essential hypertension and hypertensive renal disease | Influenza and pneumonia | Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW | HI | AA | API | NHW | HI | AA | API | NHW | HI | AA | API | NHW | HI | AA | API | NHW | HI | AA | API | |

| 2001 | 17 | 23 | 36 | 20 | 13 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 1 | 27 | 22 | 35 | 28 | 8 | 16 | 6 | 3 |

| 2002 | 18 | 28 | 34 | 12 | 17 | 7 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 19 | 2 | 29 | 27 | 28 | 31 | 9 | 11 | 5 | 2 |

| 2003 | 17 | 26 | 36 | 21 | 17 | 10 | 7 | 13 | 7 | 6 | 13 | 5 | 31 | 23 | 33 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 4 |

| 2004 | 19 | 28 | 31 | 19 | 17 | 10 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 12 | 7 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 15 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 1 |

| 2005 | 19 | 27 | 40 | 21 | 18 | 11 | 17 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 18 | 6 | 25 | 23 | 22 | 19 | 7 | 11 | 6 | 1 |

| 2006 | 21 | 28 | 38 | 16 | 17 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 4 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 15 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 2 |

| 2007 | 21 | 26 | 36 | 16 | 19 | 13 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 13 | 4 | 14 | 12 | 20 | 16 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 3 |

| 2008 | 18 | 29 | 37 | 17 | 17 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 2 |

| 2009 | 16 | 26 | 34 | 12 | 18 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 13 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 1 |

| 2010 | 17 | 24 | 35 | 15 | 19 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 9 | 15 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 2 |

| 2011 | 19 | 25 | 35 | 18 | 17 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 21 | 7 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 1 |

| 2012 | 19 | 24 | 33 | 20 | 21 | 15 | 16 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 13 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 2 |

| 2013 | 18 | 25 | 30 | 19 | 20 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 22 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 2 |

| 2014 | 19 | 21 | 37 | 12 | 21 | 14 | 15 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 15 | 8 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 2 |

| 2015 | 20 | 25 | 39 | 15 | 21 | 15 | 15 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 18 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 2 |

| 2016 | 19 | 27 | 39 | 15 | 22 | 15 | 16 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 19 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 2 |

| AAPC* | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.11 | −6.34 | 3.28 | 4.45 | −0.84 | −4.46 | 1.54 | −7.57 | −3.99 | 5.60 | −7.89 | −6.80 | −10.33 | −9.67 | −1.21 | −5.45 | −2.87 | −32.04 |

| LL | −3.34 | −4.83 | −4.81 | −20.38 | −1.53 | −1.78 | −14.69 | −23.21 | −7.12 | −24.1 | −21.25 | −14.56 | −17.05 | −16.68 | −23.54 | −26.27 | −8.24 | −16.51 | −15.69 | −65.04 |

| UL | 4.66 | 5.84 | 5.30 | 10.17 | 8.32 | 11.08 | 15.25 | 18.85 | 11.00 | 12.52 | 17.04 | 30.53 | 2.28 | 4.26 | 5.16 | 10.65 | 6.35 | 7.07 | 11.91 | 32.12 |

Comparison of cause-specific AAPC among 4 race/ethnicity groups: p > 0.05

AAPC = average annual percent change; KPSC = Kaiser Permanente Southern California; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

NHW = Non-Hispanic white; HI = Hispanic; AA = African American; API = Asian/Pacific Islander.

Table E4.

Age-adjusted cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rates (per 100,000 person-years) for people 45+ years of age, overall and by race/ethnicity for KPSC, US, and CA (2001–2016).

| KPSC | US | CA | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | NHW | HI | AA | API | Total | NHW | HI | AA | API | Total | NHW | HI | AA | API | Total |

| 2001 | 695 | 589 | 831 | 560 | 720 | 912 | 719 | 1205 | 578 | 924 | 931 | 721 | 1295 | 626 | 898 |

| 2002 | 663 | 564 | 811 | 555 | 688 | 895 | 698 | 1186 | 568 | 906 | 913 | 691 | 1297 | 607 | 876 |

| 2003 | 691 | 520 | 823 | 430 | 695 | 862 | 678 | 1159 | 542 | 874 | 896 | 692 | 1257 | 573 | 857 |

| 2004 | 639 | 484 | 763 | 489 | 655 | 810 | 633 | 1095 | 508 | 821 | 839 | 653 | 1182 | 537 | 802 |

| 2005 | 623 | 485 | 711 | 421 | 627 | 789 | 633 | 1057 | 489 | 798 | 803 | 644 | 1134 | 511 | 768 |

| 2006 | 589 | 491 | 747 | 350 | 608 | 741 | 586 | 1000 | 472 | 750 | 777 | 616 | 1119 | 514 | 743 |

| 2007 | 543 | 449 | 640 | 394 | 564 | 711 | 560 | 960 | 443 | 718 | 728 | 563 | 1056 | 475 | 692 |

| 2008 | 512 | 405 | 589 | 297 | 521 | 696 | 532 | 923 | 437 | 701 | 698 | 543 | 995 | 461 | 662 |

| 2009 | 494 | 403 | 573 | 321 | 504 | 662 | 508 | 872 | 416 | 666 | 661 | 514 | 927 | 435 | 625 |

| 2010 | 477 | 365 | 575 | 331 | 483 | 651 | 501 | 852 | 412 | 654 | 645 | 514 | 886 | 436 | 611 |

| 2011 | 472 | 379 | 613 | 304 | 476 | 636 | 468 | 813 | 384 | 634 | 640 | 492 | 883 | 404 | 598 |

| 2012 | 489 | 353 | 535 | 308 | 456 | 623 | 461 | 799 | 377 | 622 | 625 | 479 | 851 | 397 | 582 |

| 2013 | 485 | 354 | 567 | 336 | 458 | 621 | 458 | 797 | 376 | 619 | 620 | 479 | 834 | 391 | 576 |

| 2014 | 477 | 334 | 550 | 301 | 437 | 614 | 443 | 783 | 351 | 610 | 591 | 440 | 810 | 359 | 542 |

| 2015 | 507 | 354 | 555 | 331 | 459 | 624 | 451 | 785 | 356 | 618 | 618 | 452 | 812 | 368 | 561 |

| 2016 | 497 | 344 | 588 | 326 | 452 | 613 | 448 | 788 | 356 | 608 | 607 | 453 | 826 | 375 | 556 |

| AAPC* | −2.33 | −3.71 | −2.54 | −4.54 | −3.16 | −2.67 | −3.19 | −2.85 | −3.27 | −2.81 | −2.89 | −3.15 | −3.03 | −3.48 | −3.23 |

| LL* | −4.51 | −6.42 | −6.57 | −11.89 | −4.98 | −3.75 | −4.59 | −3.9 | −4.66 | −3.85 | −4.26 | −4.85 | −4.38 | −5.3 | −4.58 |

| UL* | −0.15 | −1.06 | 0.47 | 2.92 | −1.53 | −1.58 | −1.77 | −1.79 | −1.86 | −1.76 | −1.49 | −1.43 | −1.67 | −1.62 | −1.86 |

Comparison of AAPC between KPSC and CA/US for each race/ethnicity and overall: p > 0.05.

AAPC = average annual percent change; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

NHW = Non-Hispanic white; HI = Hispanic; AA = African American; API = Asian/Pacific Islander.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dianne Taylor for her assistance with formatting the manuscript.

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications performed a primary copy edit.

Appendix 1. Description of the data linkage process

The linkage was conducted by using the IBM’s InfoSphere QualityStage.1 The linkage between the enrollees and the decedents in the California Death Statistical Master Files (CDSMF) can be described at a high level in the six steps below. The linkage process between the enrollees and the decedents in the SSA Files was similar.

-

Data preparation: The identifiers used to conduct the linkage were extracted from the source files, recoded, and standardized. For example, when the enrollees were linked with decedents of the CDSMF, the following data elements were extracted.

From KPSC systems: social security number (SSN), first name, last name, middle initial, month of birth, date of birth, year of birth, sex, race, and ZIP code where the enrollee lived.

From CDSMF: SSN, first name, last name, middle initial, month of birth, date of birth, year of birth, gender, race, and residence county.

Standardization: SSN and name from both sources were standardized (e.g. validated for length and format).2 Invalid SSN were set to null.

Recoding: The corresponding variables from the two sources were recoded to ensure consistency in values. For example, the value of “ZIP code where the enrollee lived” from the KPSC Research Data Warehouse was mapped to the value of “residence county of the deceased person” from the CDSMF.

Indexing: The Soundex codes of both first name and last name from both sources were created to allow for possible alternate spellings.3 Names that sound alike may be grouped and shared the same Soundex code.

Matching: The variables listed in step 1 were matched based on probabilistic algorithms13. The software assigned each matched pair a link weight based on the degree of agreement and the degree of disagreement between the variables from the two data sources being linked.4 A high link weight indicates a high probability of true match.

Post-processing: An algorithm was applied to exclude matches that were very unlikely to be true (e.g. the enrollee accessed care at a KPSC facility 7 days after the presumed death date, or re-enrolled three months after the presumed death date). Matched pairs with a low link weight were also removed after a set of cutoff points was selected though manual review of samples stratified by age groups.

To understand the completeness of the death information identified by this linkage process, we validated the linkage results by using deaths documented within KPSC systems for enrollees who either died in a KPSC hospital or whose death was reported to KPSC. Among 266,398 deaths documented within the KPSC systems between 1988 and 2016, only 4,433 (1.7%) were not captured by the linkage process.

References

- 1.ibm.com [Internet] IBM InfoSphere QualityStage. [cited 2018 January 1]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/us-en/marketplace/infosphere-qualitystage/details.

- 2.ibm.com [Internet] Probablistic Matching in IBM InfoSphere Master Data Management. [cited 2018 September 17]. Available from http://www-01.ibm.com/support/docview.wss?uid=swg27043172.

- 3.ibm.com [Internet] What is the Soundex coding system. [cited 2018 January 1]. Available from: www-01.ibm.com/support/docview.wss?uid=swg21087113.

- 4.Fellegi IP, Sunter AB. A theory for record linkage. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1969;64(328):1183–210. [Google Scholar]

Appendix 2. 33 Categories of Cause of Deaths Defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

| Cause of Death | ICD-9 Codes | ICD-10 Codes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tuberculosis | 010–018 | A16–A19 |

| 2 | Septicemia | 038 | A40–A41 |

| 3 | Viral hepatitis | 070 | B15–B19 |

| 4 | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease | 042–044 | B20–B24 |

| 5 | Other infectious and parasitic diseases | --- | A00–A09, A20–A39, A42–A44, A46, A48–A84, A85.0–A85.2, A85.8, A86–B09, B25–B99 |

| 6 | Malignant neoplasms | 140–208 | C00–C97 |

| 7 | In situ neoplasms, benign neoplasms and neoplasms of uncertain or unknown behavior | 210–239 | D00–D48 |

| 8 | Anemias | 280–285 | D50–D64 |

| 9 | Diabetes mellitus | 250 | E50–E54 |

| 10 | Nutritional deficiencies | 260–269 | E40–E64 |

| 11 | Parkinson’s disease | 332 | G20–G21 |

| 12 | Alzheimer’s disease | 331.0 | G30 |

| 13 | Diseases of heart | 390–398, 402, 404, 410–429 | I00–I09, I11, I13, I20–I51 |

| 14 | Essential hypertension and hypertensive renal disease | 401, 403 | I10, I12, I15 |

| 15 | Cerebrovascular diseases | 430–434, 436–438 | I60–I69 |

| 16 | Atherosclerosis | 440 | I70 |

| 17 | Aortic aneurysm and dissection | 441 | I71 |

| 18 | Influenza and pneumonia | 480–487 | J09–J18 |

| 19 | Chronic lower respiratory diseases (CLRD) | 490–494, 496 | J40–J47 |

| 20 | Pneumonitis due to solids and liquids | 507 | J69 |

| 21 | Peptic ulcer | 531–534 | K25–K28 |

| 22 | Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 571 | K70, K73–K74 |

| 23 | Cholelithiasis and other disorders of gallbladder | 574–575 | K80–K82 |

| 24 | Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis | 580–589 | N00–N07, N17–N19, N25–N27 |

| 25 | Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium | 630–676 | O00–O99 |

| 26 | Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period | 760–771.2, 771.4–779 | P00–P96 |

| 27 | Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities | 740–759 | Q00–Q99 |

| 28 | Signs, symptoms, and ill-defined causes | 780–799 | R00–R99 |

| 29 | All other diseases (residual) | --- | --- |

| 30 | Unintentional injuries | E800–E869, E880–E929 | V01–X59, Y85–Y86 |

| 31 | Intentional self-harm (suicide) | E950–E959 | *U03, X60–X84, Y87.0 |

| 32 | Assault (homicide) | E960–E969, E979, E999 | *U01–*U02, X85–Y09, Y87.1 |

| 33 | All other external causes | --- | Y10–Y36, Y40–Y84, Y87.2, Y88, Y89.0–Y89.1, Y89.9 |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The ICD-10 codes for terrorism are preceded with ‘*’. See Classification of Death and Injury Resulting from Terrorism on the CDC website for more information. www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/terrorism_code.htm

Appendix 3. Projected year 2000 US population and proportion distribution by age

| Age | Population | Proportion distribution (weights) | Standard million |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 274,634,000 | 1.000000 | 1,000,000 |

| Under 1 year | 3,795,000 | 0.013818 | 13,818 |

| 1–4 years | 15,192,000 | 0.055317 | 55,317 |

| 5–14 years | 39,977,000 | 0.145565 | 145,565 |

| 15–24 years | 38,077,000 | 0.138646 | 138,646 |

| 25–34 years | 37,233,000 | 0.135573 | 135,573 |

| 35–44 years | 44,659,000 | 0.162613 | 162,613 |

| 45–54 years | 37,030,000 | 0.134834 | 134,834 |

| 55–64 years | 23,961,000 | 0.087247 | 87,247 |

| 65–74 years | 18,136,000 | 0.066037 | 66,037 |

| 75–84 years | 12,315,000 | †0.044842 | 44,842 |

| 85 years and over | 4,259,000 | 0.015508 | 15,508 |

Figure is rounded up instead of down to force total to 1.0.

Source (either one of the two below):

- CDC WONDER: https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/ucd.html#. Page 34 of the downloadable pdf file named “Technical Appendix from Vital Statistics of United States: 1999 Mortality”.

- Anderson RN, Rosenberg HM. Age standardization of death rates: Implementation of the year 2000 standard. National vital statistics reports; vol 47 no 3. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 1998. Page 113. Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr47/nvs47_03.pdf.

Footnotes

Available online at: www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2019/18-213-Supp-Mat.pdf.

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ma J, Ward EM, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Temporal trends in mortality in the United States, 1969–2013. JAMA. 2015 Oct 27;314(16):1731–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Ward E, Hao Y, Thun M. Trends in the leading causes of death in the United States, 1970–2002. JAMA. 2005 Sep 14;294(10):1255–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidney S, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Jaffe MG, et al. Recent trends in cardiovascular mortality in the United States and public health goals. JAMA Cardiol. 2016 Aug;1(5):594–9. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, Stubbs RW, et al. US county-level trends in mortality rates for major causes of death, 1980–2014. JAMA. 2016 Dec 13;316(22):2385–401. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strong K, Mathers C, Leeder S, Beaglehole R. Preventing chronic diseases: How many lives can we save? Lancet. 2005 Oct-Nov;366(9496):1578–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, Williams DR, Mero RP, Chen J. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality: Results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. JAMA. 1998 Jun 3;279(21):1703–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N Engl J Med. 2003 Apr 24;348(17):1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL, Lee I-M, Jung DL, Kampert JB. The association of changes in physical-activity level and other lifestyle characteristics with mortality among men. N Engl J Med. 1993 Feb 25;328(8):538–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel MI, Rhoads KF. Integrated health systems and evidence-based care: Standardizing treatment to eliminate cancer disparities. Future Oncol. 2015;11(12):1715–8. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhoads KF, Patel MI, Ma Y, Schmidt LA. How do integrated health care systems address racial and ethnic disparities in colon cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2015 Mar 10;33(8):854. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.8642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danforth KN, Smith AE, Loo RK, Jacobsen SJ, Mittman BS, Kanter MH. Electronic clinical surveillance to improve outpatient care: Diverse applications within an integrated delivery system. EGEMS Wash DC. 2014 Jun 24;2(1):1056. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagian JP, Lee C, Gosbee J, et al. Developing and deploying a patient safety program in a large health care delivery system: You can’t fix what you don’t know about. Jt Comm J Qual Improve. 2001 Oct;27(10):522–32. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(01)27046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankel A, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. Improving patient safety across a large integrated health care delivery system. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003 Dec;15(Suppl 1):i31–40. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford B, Skeath M, Whippy A. Kaiser Permanente Northern California sepsis mortality reduction initiative. Crit Care. 2012;16(Suppl 3):P12. doi: 10.1186/cc11699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaffe MG, Lee GA, Young JD, Sidney S, Go AS. Improved blood pressure control associated with a large-scale hypertension program. JAMA. 2013 Aug 21;310(7):699–705. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.108769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sidney S, Sorel ME, Quesenberry CP, et al. Comparative trends in heart disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality in the United States and a large integrated healthcare delivery system. Am J Med. 2018 Jul;131(7):829–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Johnson NJ, Rogot E. Mortality by Hispanic status in the United States. JAMA. 1993 Nov 24;270(20):2464–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510200070034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borrell LN, Lancet EA. Race/ethnicity and all-cause mortality in US adults: Revisiting the Hispanic paradox. Am J Public Health. 2012 May;102(5):836–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elo IT, Preston SH. Racial and ethnic differences in mortality at older ages. In: Soldo BJ, Martin LG, editors. Racial and ethnic differences in the health of older Americans. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1997. pp. 10–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy S, Kidd MP, McDonald JT, Biddle N. The healthy immigrant effect: Patterns and evidence from four countries. J Int Migration Integration. 2015 May;16(2):317–32. doi: 10.1007/s12134-014-0340-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riosmena F, Kuhn R, Jochem WC. Explaining the immigrant health advantage: Self-selection and protection in health-related factors among five major national-origin immigrant groups in the United States. Demography. 2017 Feb;54(1):175–200. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0542-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osypuk TL, Alonso A, Bates LM. Understanding the healthy immigrant effect and cardiovascular disease: Looking to big data and beyond. Circulation. 2015 Oct 20;32(16):1522–4. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubalcava LN, Teruel GM, Thomas D, Goldman N. The healthy migrant effect: New findings from the Mexican Family Life Survey. Am J Public Health. 2008 Jan;98(1):78–84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markides KS, Eschbach K. Aging, migration, and mortality: Current status of research on the Hispanic paradox. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005 Oct;60(Special Issue 2):68–75. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.Special_Issue_2.S68. Spec no. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: Comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J. 2012 Summer;16(3):37–41. doi: 10.7812/tpp/12-031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Derose SF, Contreras R, Coleman KJ, Koebnick C, Jacobsen SJ. Race and ethnicity data quality and imputation using US Census data in an integrated health system: The Kaiser Permanente Southern California experience. Med Care Res Rev. 2013 Jun;70(3):330–45. doi: 10.1177/1077558712466293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clegg LX, Hankey BF, Tiwari R, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK. Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2009 Dec 20;28(29):3670–82. doi: 10.1002/sim.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in US deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jun 7;356(23):2388–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. DOI: https://doi.org10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mensah GA, Wei GS, Sorlie PD, et al. Decline in cardiovascular mortality: Possible causes and implications. Circ Res. 2017 Jan 20;120(2):366–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zauber AG. The impact of screening on colorectal cancer mortality and incidence: Has it really made a difference? Digest Dis Sci. 2015 Mar;60(3):681–91. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3600-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 4;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Narod SA, Iqbal J, Miller AB. Why have breast cancer mortality rates declined? J Cancer Policy. 2015 Sep;5:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2015.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLaughlin JK, Hrubec Z, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF., Jr Smoking and cancer mortality among US veterans: A 26-year follow-up. Int J Cancer. 1995 Jan 17;60(2):190–3. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM, Miller PE, et al. Higher diet quality is associated with decreased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality among older adults. J Nutr. 2014 Jun;144(6):881–9. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.189407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez C, Patel AV, Calle EE, Jacobs EJ, Chao A, Thun MJ. Body mass index, height, and prostate cancer mortality in two large cohorts of adult men in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001 Apr;10(4):345–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laumbach RJ, Kipen HM. Respiratory health effects of air pollution: Update on biomass smoke and traffic pollution. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Jan;129(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.California State University (CSU) Chancellor’s Office. California named state with the worst air quality (again) [Internet] Science Daily. 2017. Jun 19, [cited 2018 Mar 28]. Available from: www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/06/170619092749.htm.

- 39.Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: COPD among adults in California [Internet] Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; [cited 2018 May 28]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/copd/maps/docs/pdf/CA_COPDFactSheet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor CA, Greenlund SF, McGuire LC, Lu H, Croft JB. Deaths from Alzheimer’s disease—United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(20):521. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6620a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sampson EL, Blanchard MR, Jones L, Tookman A, King M. Dementia in the acute hospital: Prospective cohort study of prevalence and mortality. Br J Psychiatry. 2009 Jul;195(1):61–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Travers C, Byrne GJ, Pachana NA, Klein K, Gray LC. Prospective observational study of dementia in older patients admitted to acute hospitals. Australas J Ageing. 2014 Mar;33(1):55–8. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan DJ, O’Regan NA, Caoimh RO, et al. Delirium in an adult acute hospital population: Predictors, prevalence and detection. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001772. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zekry D, Herrmann FR, Grandjean R, et al. Does dementia predict adverse hospitalization outcomes? A prospective study in aged inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009 Mar;24(3):283–91. doi: 10.1002/gps.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruiz JM, Steffen P, Smith TB. Hispanic mortality paradox: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the longitudinal literature. Am J Public Health. 2013 Mar;103(3):e52–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diaz CJ, Koning SM, Martinez-Donate AP. Moving beyond salmon bias: Mexican return migration and health selection. Demography. 2016 Dec;53(6):2005–30. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0526-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turra CM, Elo IT. The impact of salmon bias on the Hispanic mortality advantage: New evidence from Social Security data. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2008 Oct;27(5):515–30. doi: 10.1007/s11113-008-9087-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rana JS, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Jaffe MG, Sidney S, Karter AJ. Ethnic differences in risk of coronary heart disease in a large contemporary population. Am J Prev Med. 2016 May;50(5):637–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.James BD, Leurgans SE, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Yaffe K, Bennett DA. Contribution of Alzheimer disease to mortality in the United States. Neurology. 2014 Mar 25;82(12):1045–50. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson RN, Miniño AM, Hoyert DL, Rosenberg HM. Comparability of cause of death between ICD-9 and ICD-10: Preliminary estimates. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001 May 18;49(2):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jatrana S, Richardson K, Blakely T, Dayal S. Does mortality vary between Asian subgroups in New Zealand: An application of hierarchical Bayesian modelling. PloS One. 2014 Aug 20;9(8):e105141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pu J, Hastings KG, Boothroyd D, et al. Geographic variations in cardiovascular disease mortality among Asian American subgroups, 2003–2011. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017 Jul 12;6(7):e005597. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table E1.

Age-adjusted mortality rates (per 100,000 person-years) by race/ethnicity and sex in KPSC, California (CA), and US, 2001–2016.

| Year | Non-Hispanic white | Hispanic | African American | Asian/Pacific islander | Overall | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |||

| KPSC | 2001 | 819 | 585 | 687 | 644 | 452 | 535 | 962 | 674 | 792 | 609 | 388 | 489 | 684 |

| 2002 | 812 | 593 | 688 | 635 | 438 | 524 | 939 | 599 | 735 | 561 | 411 | 481 | 668 | |

| 2003 | 814 | 610 | 700 | 632 | 455 | 534 | 987 | 648 | 784 | 514 | 351 | 427 | 683 | |

| 2004 | 777 | 578 | 666 | 594 | 459 | 520 | 962 | 630 | 762 | 548 | 381 | 459 | 660 | |

| 2005 | 794 | 579 | 674 | 627 | 424 | 515 | 914 | 661 | 763 | 548 | 361 | 446 | 657 | |

| 2006 | 737 | 554 | 635 | 644 | 448 | 536 | 874 | 616 | 719 | 471 | 312 | 383 | 636 | |

| 2007 | 713 | 545 | 620 | 595 | 428 | 502 | 804 | 601 | 683 | 476 | 347 | 406 | 616 | |

| 2008 | 687 | 526 | 598 | 564 | 408 | 479 | 814 | 556 | 657 | 467 | 306 | 379 | 594 | |

| 2009 | 685 | 489 | 577 | 546 | 411 | 471 | 778 | 550 | 639 | 446 | 328 | 381 | 574 | |

| 2010 | 677 | 479 | 566 | 538 | 367 | 443 | 771 | 554 | 639 | 449 | 304 | 369 | 557 | |

| 2011 | 654 | 485 | 561 | 540 | 371 | 447 | 816 | 540 | 647 | 453 | 316 | 377 | 548 | |

| 2012 | 669 | 486 | 568 | 552 | 361 | 445 | 756 | 543 | 629 | 456 | 309 | 375 | 531 | |

| 2013 | 680 | 489 | 575 | 520 | 374 | 439 | 737 | 530 | 612 | 450 | 337 | 387 | 532 | |

| 2014 | 675 | 468 | 562 | 505 | 363 | 427 | 750 | 523 | 612 | 420 | 310 | 359 | 511 | |

| 2015 | 665 | 511 | 581 | 538 | 381 | 451 | 763 | 533 | 625 | 438 | 340 | 383 | 529 | |

| 2016 | 662 | 490 | 568 | 490 | 374 | 445 | 817 | 544 | 652 | 458 | 312 | 377 | 521 | |

| AAPC* | −1.45 | −1.26 | −1.30 | −1.93 | −1.36 | −1.28 | −1.19 | −1.54 | −1.36 | −2.06 | −1.90 | −1.95 | −1.84 | |

| LL | −2.82 | −3.26 | −2.67 | −4.28 | −3.80 | −7.60 | −3.51 | −4.02 | −3.26 | −5.02 | −6.62 | −5.27 | −2.95 | |

| UL | −0.07 | 0.78 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 1.14 | 5.48 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.99 | 3.06 | 1.49 | −0.71 | |

| CA | 2001 | 970 | 709 | 825 | 777 | 534 | 640 | 1339 | 913 | 1092 | 635 | 432 | 519 | 783 |

| 2002 | 960 | 700 | 815 | 752 | 515 | 620 | 1335 | 918 | 1096 | 614 | 420 | 504 | 770 | |

| 2003 | 955 | 699 | 813 | 764 | 523 | 630 | 1304 | 911 | 1083 | 605 | 414 | 496 | 768 | |

| 2004 | 912 | 674 | 780 | 735 | 500 | 604 | 1268 | 885 | 1051 | 581 | 394 | 474 | 734 | |

| 2005 | 904 | 667 | 774 | 753 | 510 | 618 | 1263 | 875 | 1046 | 580 | 393 | 472 | 731 | |

| 2006 | 896 | 656 | 765 | 732 | 504 | 606 | 1219 | 859 | 1018 | 566 | 391 | 465 | 718 | |

| 2007 | 865 | 636 | 740 | 689 | 480 | 575 | 1178 | 840 | 989 | 554 | 377 | 453 | 692 | |

| 2008 | 849 | 627 | 728 | 673 | 476 | 565 | 1127 | 821 | 957 | 544 | 379 | 449 | 678 | |

| 2009 | 831 | 608 | 710 | 658 | 457 | 547 | 1094 | 779 | 918 | 526 | 364 | 433 | 656 | |

| 2010 | 818 | 605 | 702 | 654 | 452 | 542 | 1034 | 757 | 880 | 526 | 368 | 435 | 647 | |

| 2011 | 819 | 602 | 702 | 637 | 448 | 533 | 1051 | 765 | 892 | 503 | 357 | 420 | 641 | |

| 2012 | 811 | 594 | 693 | 622 | 441 | 523 | 1017 | 736 | 862 | 501 | 351 | 415 | 630 | |

| 2013 | 812 | 593 | 694 | 634 | 441 | 528 | 1029 | 723 | 860 | 500 | 343 | 410 | 630 | |

| 2014 | 788 | 573 | 673 | 605 | 418 | 502 | 1003 | 708 | 840 | 466 | 328 | 388 | 606 | |

| 2015 | 809 | 592 | 693 | 617 | 428 | 514 | 1019 | 728 | 861 | 480 | 342 | 402 | 622 | |

| 2016 | 800 | 584 | 685 | 621 | 429 | 517 | 1032 | 721 | 860 | 478 | 338 | 399 | 617 | |

| AAPC* | −1.30 | −1.31 | −1.25 | −1.53 | −1.49 | −1.45 | −1.76 | −1.59 | −1.61 | −1.92 | −1.66 | −1.78 | −1.60 | |

| LL | −2.15 | −2.17 | −2.10 | −2.86 | −2.76 | −2.73 | −2.95 | −2.59 | −2.65 | −3.13 | −2.87 | −2.88 | −2.51 | |

| UL | −0.43 | −0.44 | −0.40 | −0.18 | −0.20 | −0.16 | −0.56 | −0.59 | −0.57 | −0.70 | −0.44 | −0.66 | −0.69 | |

| US | 2001 | 1019 | 717 | 847 | 809 | 547 | 663 | 1400 | 932 | 1122 | 606 | 416 | 497 | 859 |

| 2002 | 1017 | 717 | 846 | 800 | 536 | 652 | 1385 | 928 | 1114 | 596 | 407 | 487 | 856 | |

| 2003 | 997 | 710 | 835 | 784 | 534 | 645 | 1367 | 914 | 1099 | 583 | 405 | 481 | 844 | |