Abstract

Introduction

The importance of mentoring new physicians is well established.

Objectives

To evaluate and improve use of a competencies-based mentoring checklist to help new physicians understand the basic work environment and resources in their daily jobs as well as achieve needed competencies.

Methods

Literature searches, process improvements, and a review of curricula and mentoring from both inside and outside our large Medical Group were conducted to understand the workflow for new physician orientation, onboarding, and mentoring processes. We aimed to achieve a structured framework for mentor training, evaluation of the mentor-mentee relationship, and development of a bridge for the knowledge gaps and needs of the individual physicians in their departments. Finally, we surveyed new physician hires/mentees in 2017 about their competencies using the new checklist.

Results

The new mentoring process was improved compared with the current mentoring process. Polling of physician mentees after implementation of the checklist showed a 75% completion rate of checklist competencies from January 2017 to April 2018, compared with a baseline of 0%.

Conclusion

Review of performance data and addressing deficiencies in a mentoring relationship can lead to active participation and meaningful change in competencies among new physicians.

Keywords: competencies, competencies-based mentoring checklist, mentor, mentoring, processes, process improvement

INTRODUCTION

The benefits of mentoring newly hired physicians have been recognized by many health care organizations, including The Permanente Medical Group, Inc (TPMG) in Northern California.1,2

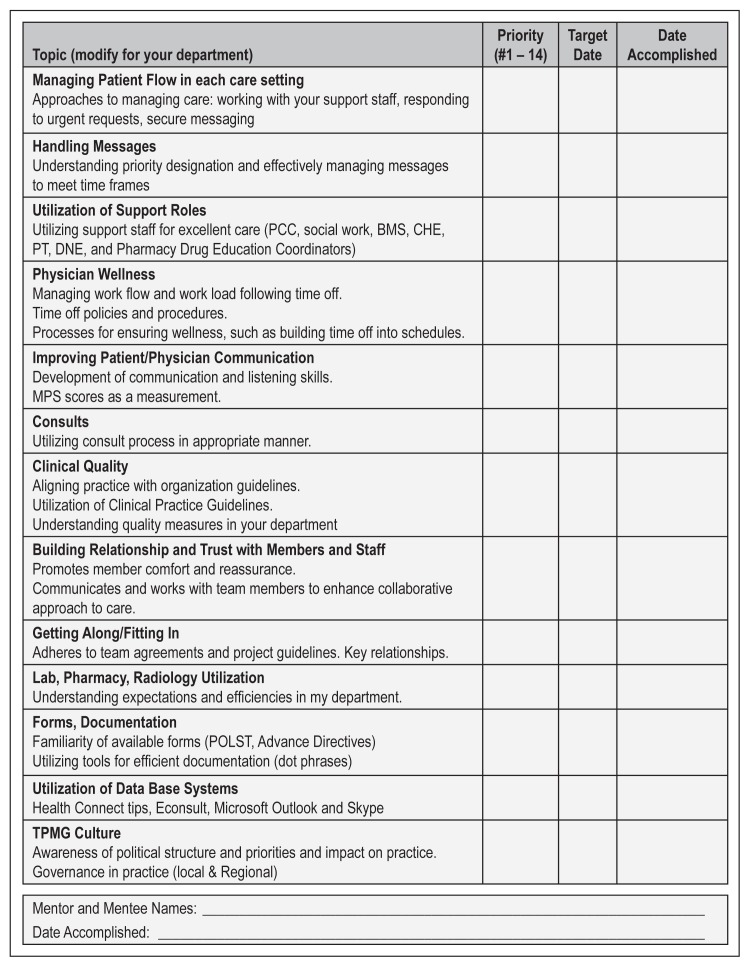

In our group, mentoring during the first year of hire is designed to help physicians improve their efficiency, reduce their stress, and understand our culture. To accomplish this, we use a 13-item mentoring checklist for all new physician hires: 1) managing patient flow; 2) handling messages; 3) utilization of support staff; 4) physician wellness; 5) physician-patient communication; 6) consults; 7) clinical quality; 8) relationship building; 9) social cohesion; 10) laboratory, pharmacy, and radiology utilization; 11) forms and documentation, 12) utilization of database systems, and 13) TPMG culture. The full checklist is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

New Physician Mentoring Checklist.

1) Asking “Does your department have current written onboarding documents?”

2) Asking: “Was this mentoring checklist effective?”

BMSD = Behavioral Medicine Specialist; CHE = Clinical Health Educator; DNE = Dietary Nutrition Educator; Lab = laboratory; MPS = Member Patient Satisfaction; PCC = Patient Care Coordinators; POLST = Physician Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment; PT = Physical Therapy; TPMG = The Permanente Medical Group.

On the premise that ineffective mentoring3,4 can contribute to turnover, we decided to examine our mentoring process. We aimed to achieve a structured framework for mentor training,5 evaluation of the mentor-mentee relationship, and development of a bridge for the knowledge gaps and needs of the individual physicians in their departments.

METHODS

Initially, we mapped our current workflow for new physician orientation, onboarding, and mentoring processes. We also conducted a literature search on mentoring processes and contacted other health systems to understand their processes. We then determined the rates of completion of the 13 checklist competencies shown in Figure 1. Our 2016 data from the Greater Southern Alameda Area service area, a division of TPMG servicing more than 343,000 patients and staffed by approximately 650 physicians, showed only an 8.5% completion of the new physician-mentoring checklist based on mentor self-report.

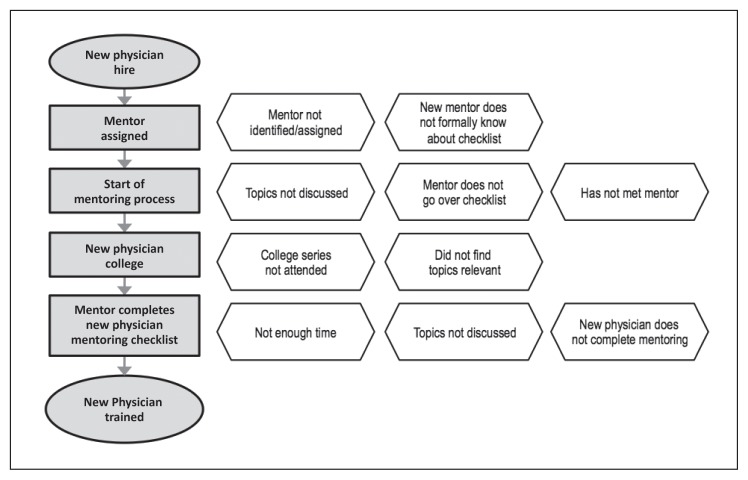

Because of this low response rate, we determined mentoring process opportunities (gap analysis; Figures 2 and 3). We defined an ideal model focusing on 1) human resources onboarding, 2) new physician orientation workshops, 3) new physician and mentor matching, and 4) mentor and mentee completion of competency topics. Then we developed and implemented the model to improve the completion rate experienced by new physicians. Competency checklists were provided more widely to include new physicians, as well as mentors and department chiefs rather than only mentors.

Figure 2.

Current process map for training new physicians; gaps are identified on the right.

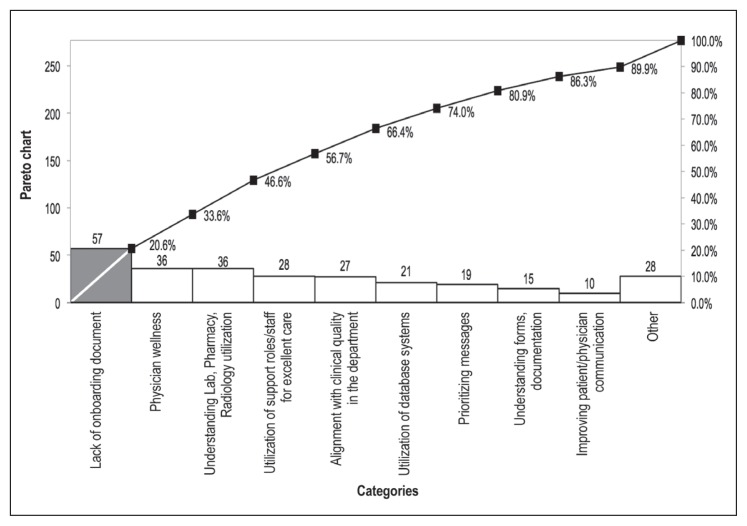

Figure 3.

Pareto chart of issues/concerns identified as areas for needed improvement for new physicians hired in 2017.

Lab = laboratory.

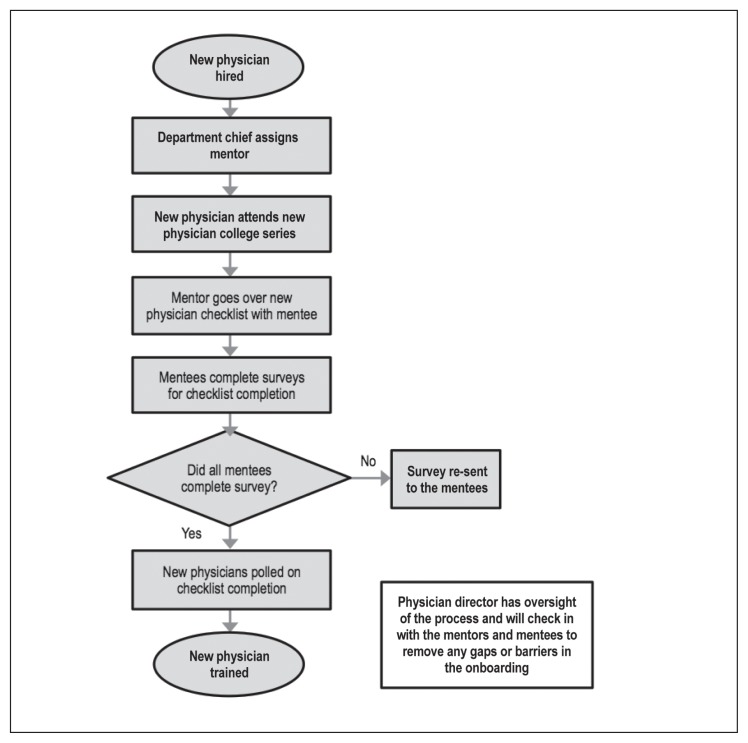

A physician director had oversight of the mentoring process (Figure 4) and checked in with mentors and mentees to remove any gaps or barriers in onboarding, such as meeting with department chiefs, managers, mentors, and mentees. These meetings discussed giving physicians sufficient mentor time and training (also referred to as mentoring boot camp), providing department chiefs the new physician-mentoring checklist, and so on. Furthermore, the director presented the new physician checklist and processes at the new physicians’ college (specific for service area resources) and new chiefs’ orientation. To complete the mentoring process, 26 hours of mentoring time was suggested and given to each mentor and mentee pair. Several timelines exist that mentoring pairs could follow to assist in setting time aside for adequate training.

Figure 4.

Future process map for training new physicians.

We sent the physician mentoring checklist by email with 2 additional questions (Figure 1) to new physician hires in 2017. We re-sent surveys to those who did not complete the survey after 1 week. The survey was sent up to 4 times on February 3, 2018; February 10, 2018; February 17, 2018, and March 10, 2018. An unannounced reward of a box of chocolates was sent to responders as a positive reinforcement for completing the new physician checklist. The checklist was sent to the new physicians via email from the Director of Physician Mentoring who received the results. A survey was considered valid on completion of all 15 questions.

RESULTS

After the enhanced mentorship process began, polling of 60 2017 physician mentees showed 75% of mentees completed their checklist competencies from January 2017 to April 2018, compared with a baseline of 0% due to no data collection before to this new process (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

Mentoring is a proven way to improve competency and enculturation of new physicians into a medical group, in addition to increasing job satisfaction and job performance.1,6

This article describes our process for examining the completion of our mentoring process and how we substantially improved the competency completion rate. Revising and widely distributing the checklist contributed to a surplus of new physicians achieving competency completion.

Tracking of competency completion by new physicians and their mentors will continue in 2018, after additional formal leadership training for mentors. The goal is to continually improve the competency completion rate. Furthermore, the director will address departmental gaps (eg, lack of current onboarding documents, must reflect topics such as physician wellness, utilization of support staff for excellent care, and alignment with clinical quality) at a meeting of the department chiefs.

CONCLUSION

It is necessary for health care organizations to support new physicians in all aspects. By identifying the gaps early on, there are chances to improve work processes to ensure efficiency and positive health outcomes for practitioners and patients. Eliminating the barriers and supporting the mentoring relationship allows for lifelong learning and performance improvement.

Acknowledgments

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications performed a primary copy edit.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Bronson D, Ellison E. Crafting successful training programs for physician leaders. Healthcare. 2015 Oct; doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleig-Palmer MM, Rathert C. Interpersonal mentoring and its influence on retention of valued health care workers. Health Care Management Review. 2015 Jan;40(1):56–64. doi: 10.1097/hmr.0000000000000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao MC, Jou RC, Liao CC, Kuo CW. Workplace stress, job satisfaction, job performance, and turnover intention of health care workers in rural Taiwan. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015 Mar;27(2):NP1827–36. doi: 10.1177/1010539513506604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swenson SJ, Shanafelt T. An organizational framework to reduce professional burnout and bring back joy in practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017 Jun;43(6):308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parise MR, Forret M. Formal mentoring programs: The relationship of program design and support to mentors’ perceptions of benefits and costs. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2008;72(2):225–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]