Abstract

Super-enhancers (SEs) refer to large clusters of enhancers that drive gene expressions. Recent data has provided novel insights in elucidating the roles of SEs in many diseases, including cancer. Many mechanisms involved in tumorigenesis and progression, ranging from internal gene mutation and rearrangement to external damage and inducement, have been demonstrated to be highly associated with SEs. Moreover, translocation, formation, deletion, or duplication of SEs themselves could lead to tumor development. It has been reported that various oncogenic molecules and pathways are tightly regulated by SEs. Moreover, several clinical trials on novel SEs blockers, such as BET inhibitor and CDK7i, have indicated the potential roles of SEs in cancer therapy. In this review, we highlighted the underlying mechanism of action of SEs in cancer development and the corresponding novel potential therapeutic strategies. It is speculated that targeting SEs could complement the traditional approaches and lead to more effective treatment for cancer patients.

Keywords: super-enhancer, neoplasms, bromodomain and extra-terminal domain protein, cyclin-dependent kinase 7, enhancer elements

Introduction

The hallmarks of cancer, such as aberrant proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and apoptotic evasion, are closely related to aberrant gene expression (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Therefore, genetic and epigenetic changes are fundamental mechanisms of cancer (Bradner et al., 2017). Promoters refer to sites to which the basal transcription machinery is recruited, usually located within 100–1,000 bp upstream of the transcription start sites (TSS). Since a promoter usually induces basal or limited levels of gene expression, higher levels of gene expression require highly regulated promoter–enhancer interactions (Carter et al., 2002).

Enhancers refer to transcription factors (TFs) that bind to DNA regulatory elements. They play key roles in the regulation of cell-type-specific gene expression, over both short and long distances, independent of their position and orientation with respect to TSS (Banerji et al., 1981; Bulger and Groudine, 2011). They exhibit three main characteristics. First, they often contain conserved DNA sequences and are located in open chromatin regions without nucleosomes, which allows for binding of RNA polymerase, TFs, and co-activators. Second, enhancers are typically enriched with a post-translational modification histone mark, such as acetylation at H3 lysine 27 (H3K27ac) and mono-methylation at H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me1). Third, unlike promoter sequences, enhancers can be located distantly from the TSS of their target genes (from less than 10 kb to more than 1 Mb) (Hnisz et al., 2013).

Super-enhancers (SEs) comprise of a set of enhancers spanning across a long range of genomic DNA, with some individual constituent enhancers exhibiting stronger transcriptional activation ability than others (Hnisz et al., 2013; Shin, 2018). SEs exhibit a similar mechanism of action as normal enhancers. Binding of TFs to enhancers facilitates enhancer interaction with the basal transcription machinery, RNA polymerase II, and promoters in a gene-specific manner, which is mediated by “looping” of the loaded enhancer to the cognate promoter. Then, the basal transcription machinery is recruited to promoters, which initiates downstream transcription (Sengupta and George, 2017).

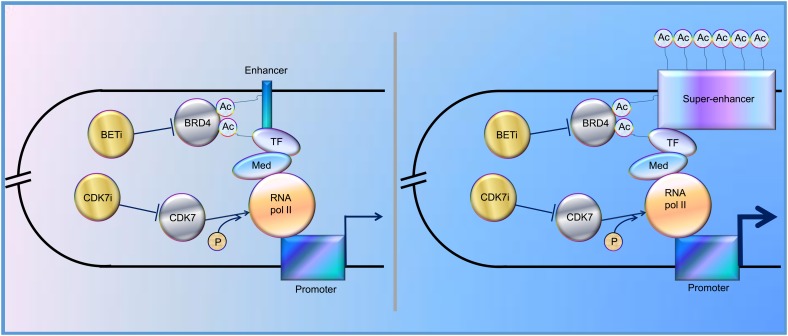

In the past decade, increasing evidence has revealed that SEs play a vital role in tumorigenesis, indicating that SEs could be one of the promising therapeutic targets for cancer treatment. Indeed, BRD4, one of the bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) protein family members, binds acetylated histones at TFs, TSS, and SEs, brings them together, and mediates transcriptional co-activation and elongation via RNA polymerase II and a mediator (Hajmirza et al., 2018). Their inhibition disrupts the communication between SEs and their target promoters along with a subsequent cell-specific-repression of oncogenes, which is considered to be the main mechanism of sensitivity to BET inhibitor (BETi) (Donati et al., 2018). Besides, CDK7 inhibitor, another kind of SE blocker, functions by inhibiting phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II (Nilson et al., 2015), and has been proved to significantly inhibit tumor growth (Figure 1). Here, we review the regulation and roles of SEs in various cancers to elucidate possible therapeutic targets for cancer treatment and provide potential future directions for the studies on SEs.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the functions of enhancer and super-enhancer (SE) in the regulation of gene expression, mediated by “looping.” BRD4 binds to acetylated lysines (Ac) in enhancer, SE, and transcription factors (TF), bringing them together and mediating transcriptional co-activation and elongation via RNA polymerase II (RNA pol II) and mediator (Med) (Sengupta and George, 2017; Donati et al., 2018; Hajmirza et al., 2018). CDK7 can activate RNA Pol II by promoting its phosphorylation (Nilson et al., 2015). CDK7i, CDK7 inhibitor; BETi, BET inhibitor; p, phosphate group.

SEs in Hematological Malignancy

Table 1 summarizes the regulation and roles of SEs in hematological malignancies.

Table 1.

SEs’ roles in hematological malignancy.

| Disease† | Phenotype‡ | Upstream (O/S) and potential therapeutic targets§ | Regulation of SEs | Downstream | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | DLT | BETi: OTX015 (S) | ↓ | NM | Berthon et al., 2016 |

| AML | P, A | NPM1; BETi: I-BET151 (S) | ↓ | NM | Dawson et al., 2014 |

| AML | D, P, G | CDK8, 19 (O) | ↓ | STAT1 S727 | Nitulescu et al., 2017 |

| AML | D | NCD38 (S), LSD1 (O) | ↓/↑ | GFI1, ERG | Sugino et al., 2017 |

| AML | A | BETi: BI894999 (S) | ↓ | p-Ser2 RNA polymerase II | Gerlach et al., 2018 |

| B-ALL | D | IKAROS (S) | ↓ | Sykb, CD79b | Hu Y. et al., 2017 |

| B-ALL | A, P, D, T | STAT5 (O); PAX5, EBF, IKAROS (S) | ↑/↓ | NM | Katerndahl et al., 2017 |

| BL and IL | A | EBV (O) | ↑ | CFLAR, IRF2 | Ma et al., 2017 |

| BPDCN | A | TCF4 (O), BETi: JQ1 (S) | ↓ | NM | Ceribelli et al., 2016 |

| CLL | A, TG | SNP rs539846 (O) | ↓ | BCL2-BMF | Kandaswamy et al., 2016 |

| CLL | P | PAX5 (O) | ↑ | BCL2, CXCR4, CD83… | Ott et al., 2018 |

| DLBCL and FL | D | CREBBP (S) | ↓ | BCL6, MEF2B, MEF2C… | Zhang et al., 2017 |

| ETP-ALL | D | NPi:GSIs (S) | ↓ | MYC | Knoechel et al., 2015 |

| LP | DLT | BETi: OTX015 (S) | ↓ | NM | Amorim et al., 2016 |

| LP and LK | P | CREBBP/EP300 (O); CBP30 (S) | ↑/↓ | GATA1, MYC | Garcia-Carpizo et al., 2018 |

| MM | P | JQ1 | ↓ | MYC | Loven et al., 2013 |

| MM | DLT | BETi: OTX015 (S) | ↓ | NM | Amorim et al., 2016 |

| PEL | P, A | IMiDs, JQ-1, IBET151, PFI-1 (S) | synergy | IRF4, IKZF1 (but not IKZF3) | Gopalakrishnan et al., 2016 |

| T-ALL | TG | NOTCH1 (0) | ↑ | MYC | Herranz et al., 2014 |

| T-ALL | P, A | THZ1 (S) | ↓ | RUNX1 | Kwiatkowski et al., 2014 |

| T-ALL | D, TG | TAL1/SCL (O) | ↓ | GIMAP | Liau et al., 2017 |

†Abbreviation for cancers: AL, acute leukemia; AML, acute myelocytic leukemia; B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; BL, Burkitt lymphoma; BPDCN, blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma; ETP-ALL, early T-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia; FL, follicular lymphoma; IL, immunosuppression-related lymphomas; LK, leukemia; LP, lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; PEL, primary effusion lymphoma; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. ‡Abbreviation for phenotypes: A, apoptosis; D, differentiation; DLT, dose-limiting toxicity; G, growth; MT, metastasis. NM: not mentioned; P: proliferation; T: transformation; TG: tumorigenesis; §Abbreviation for molecules: BETi, bromodomain inhibitor; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; IMiDs, immunomodulatory drugs; NM, not mentioned; NPi, Notch pathway inhibitor; O, oncogenic; S, suppressor of cancer.

Several mechanisms of tumorigenesis in hematopoietic system have been proved to be associated with SEs, including mutation, fusion and expression of specific genes, activation of pathways, and infection of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

Several mechanisms of tumorigenesis in hematopoietic system have been proved to be associated with SEs, including mutation, fusion, and expression of specific genes, activation of pathways, and infection of EBV (Herranz et al., 2014; Kandaswamy et al., 2016; Hu Y. et al., 2017; Katerndahl et al., 2017; Liau et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2017; Nitulescu et al., 2017). Generally, SEs were thought to promote tumorigenesis and malignancy, based on the reports that SEs upregulate oncogenes whereas broad H3K4me3 peaked at tumor suppressor genes (Hnisz et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2015). However, Cao et al. (2017) showed some overlaps in these two types of elements, suggesting that SEs could play both roles. Therefore, researchers should pay attention to the possible downregulation of suppressor genes when using BETi.

BET inhibitor is a hot topic in SE research. BETi, such as I-BET151 and JQ1, downregulated SE-associated genes, and suppressed proliferation and promoted apoptosis in AML multiple myeloma, acute leukemia, lymphoma, and primary effusion lymphoma (Loven et al., 2013; Dawson et al., 2014; Pelish et al., 2015; Gopalakrishnan et al., 2016). Besides, after determining dose-limiting toxicity of OTX015 in phase 1 clinical study, researchers reported that for further phase 2 studies, the once-daily recommended dose for oral, single agent use of OTX015 in patients with acute leukemia or lymphoma is 80 mg, on a 14 days on/7 days off schedule (Amorim et al., 2016; Berthon et al., 2016). Researchers also reported some new BETi, such as BI894999, and other SE inhibitors, including THZ1, NCD38, PLX51107, GSIs, and CBP30 (Kwiatkowski et al., 2014; Knoechel et al., 2015; Sugino et al., 2017; Garcia-Carpizo et al., 2018; Gerlach et al., 2018; Ott et al., 2018). These could provide novel alternatives or synergetic BETi drugs for cancer treatment. Besides, researchers have found some feedback regulations between SEs and corresponding genes. For example, STAT5 and PEPII promote the expression of corresponding SEs in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Katerndahl et al., 2017), which indicated a better response to SE blockers in this cancer. Intriguingly, Zhang et al. (2017), Garcia-Carpizo et al. (2018) drew contradictory conclusions with each other about whether CREBBP, an acetyltransferase, promotes or suppresses cancer development. However, their conclusion came from different tumor models (diffuse large B cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma for Zhang; leukemia and lymphoma for Garcia) and involved different downstream genes (BCL6, MEF2B, and MEF2C for Zhang; GATA1 and MYC for Garcia). Thus, the inconsistent results might be obtained due to the diverse functions of downstream genes controlled by corresponding SEs.

SEs in Nervous System Neoplasms

Table 2 summarizes the regulation and roles of SEs in nervous system neoplasms.

Table 2.

SEs’ roles in neoplasms of nervous system.

| Cancer type† | Phenotype‡ | Upstream (O/S) and potential therapeutic targets§ | Regulation of SEs | Downstream | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBM | NM | NM | translocated in | TERT | Francis et al., 2014 |

| GBM | P | NM | enriched with 5hmC | proliferation-associated TFs | Johnson et al., 2016 |

| GBM | P | CDK7i: THZ1 (S) | ↓ | WNT7B, FOSL1, FOXL1… | Meng et al., 2018 |

| NB | OS | TERT rearrangement (O) | ↑ | TERT | Valentijn et al., 2015 |

| NB | P, D, CC | JQ1, THZ1 (S) | ↓ | TBX2, MYCN, FOXM1-DREAM | Decaesteker et al., 2018 |

| NB | OS, TG | rs2168101, rs3750952 (in LMO1) (S) | ↓ | NM | He et al., 2018 |

| MB | OS | Somatic variants (O) | ↑ | GFI1, GFI1B | Northcott et al., 2014 |

| MB | P, TG | MLL4 (S) | ↓ | Dnmt3a and Bcl6 | Dhar et al., 2018 |

| EO | P, CC | JQ1, AZD1775, AZD4547 (S) | ↓ | PAX6, SKI, CCND1… | Mack et al., 2018 |

†Abbreviation for cancers: EO, ependymoma; GBM, glioblastomas; MB, medulloblastoma; NB, neuroblastoma. ‡Abbreviation for phenotypes: CC, cell cycle; D, differentiation; G, growth; NM, not mentioned; OS, overall survival; P, proliferation; TG, tumorigenesis. §Abbreviation for molecules: CDK7i, CDK7 inhibitor; MLL4, H3K4 methyltransferase; NM, not mentioned; O, oncogenic molecule; S, suppressor of cancer; TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase; TF, transcription factor.

In nervous system tumors, SEs could be regulated by gene rearrangement, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), binding of TFs, or modification of enzymes (Northcott et al., 2014; Valentijn et al., 2015; Dhar et al., 2018; He et al., 2018). Besides, SEs themselves could also be modified or translocated to new loci and exhibit different activities, leading to novel mechanisms for SEs-related tumorigenesis (Francis et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2016). Furthermore, several downstream genes and related pathways of SEs have been discovered. Decaesteker et al. (2018) identified a novel core regulatory circuitry constituent (TBX2) in high-risk neuroblastoma, which was regulated by SEs. Dhar et al. (2018) reported that some SEs suppressed medulloblastoma and provided a unique tumor-suppressive mechanism in which MLL4, a H3K4 methyltransferase, is necessary to maintain broad H3K4me3 and SEs at tumor suppressor genes.

Several researchers have reported various SEs inhibitors that control cancer development. Chipumuro et al. (2014) found that CDK7i could lead to significant tumor regression in high-risk neuroblastoma mouse model without introducing systemic toxicity, which implied striking therapeutic selectivity. Henssen et al. (2016) reported that, in preclinical MYCN-driven neuroblastoma models, concurrent MYCN repression was observed in OTX015-treated samples, which could not be abrogated by ectopic MYCN expression. In addition, OTX015 treatment significantly suppressed tumor cell proliferation and improved survival of mice. Decaesteker et al. (2018) found that JQ1 coupled with THZ1 prevented the cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation in neuroblastoma primary cultured cell through strong repressive effects on CRC gene expression and p53 pathway response. Similarly, by gene mapping and integrating data with drug interaction databases, Mack et al. (2018) identified and validated dependency of ependymoma to SEs, which was responsive to SE inhibition. Meng et al. (2018) reported that THZ1 inhibits growth and proliferation of glioblastoma cells both in vitro and in vivo. In addition, CDK7 inhibition via CRISPR-Cas9 or RNA interference significantly disrupted GBM cell growth.

These results indicated that inhibitors of SEs could be promising candidates for cancer treatment.

SEs in Visceral Organ Tumors

Table 3 summarizes the regulation and roles of SEs in visceral organ tumors.

Table 3.

SEs’ roles in visceral organ tumors.

| Cancer type† | Phenotype‡ | Upstream (O/S) and potential therapeutic targets§ | Regulation of SEs | Downstream | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC | P, G | NSD2 (O) | ↑ | RAS | Garcia-Carpizo et al., 2016 |

| LC | P | TF: TBX4 (S) | ↑ | SFRP1, ADM, THBS1… | Horie et al., 2018 |

| PC | NM | T2E fusion gene (O) | ↑ | EGR | Babu and Fullwood, 2017 |

| CRC | G | NM | translocated on | CCAT1-L | Xiang et al., 2014 |

| CRC | P | BETi: JQ1 (S) | ↓ | c-MYC | Togel et al., 2016 |

| CRC | NM | NM | 5hmC modified | NM | Hu H. et al., 2017 |

| CRC | NM | RTD (O) | formation of a 3D contact domain | IGF2 | Weischenfeldt et al., 2017 |

| CLC | P, A | BETi: JQ1 (S) | ↓ | MAPK signaling pathway | Nakamura et al., 2017 |

| PDA | P, G, I, M | KDM6A (S) | ↓ | DeltaNp63, MYC, RUNX3… | Andricovich et al., 2018 |

| OSCC | P, A | CDK7i: THZ1 (S) | ↓ | PAK4, RUNX1, DNAJB1… | Jiang Y.Y. et al., 2017 |

| OSCC | M, G | SCC-specific hypermethylation (O) | ↓ | ZFP36L2 | Lin et al., 2018 |

| OSCC | P, I, M | TF: TP63 (O) | ↑ | lncRNA: LINC01503 | Xie et al., 2018 |

| LIHC | P, I, M, CC | ZEB1 (O) | ↑ | lncRNA: HCCL5 | Peng et al., 2018 |

| CVC | P | BETi: JQ1, iBET72 (S) | ↓ | viral oncogenes: E6 and E7 | Dooley et al., 2016 |

| OC | OS | SNP: rs6674079 (1q22) (O) | ↑ | MEF2D | Johnatty et al., 2015 |

†Abbreviation for cancers: CLC, colon cancer; CRC, colorectal carcinoma; CVC, cervical cancer; LC, lung cancer; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; OC, ovarian cancer; OSCC, oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma; PC, prostate cancers; PDA, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. ‡Abbreviation for phenotypes: A, apoptosis; CC, cell cycle; G, growth; I, invasion; M, migration; NM, not mentioned; OS, overall survival; P, proliferation. §Abbreviation for molecules: BETi, Bromodomain inhibitor; CDK7i, CDK7 inhibitor; NM, not mentioned; O, oncogenic molecule; S, suppressor of cancer; RTD, Recurrent tandem duplications; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; TF, transcription factor

Most SEs promote the forming and malignancy of visceral organ tumors. For example, SEs lead to the overexpression of ERG, leading to overexpression of target genes that drive development of prostate cancer (Babu and Fullwood, 2017). Moreover, SEs activate MAPK signaling pathway to inhibit apoptosis and promote proliferation of colon cancer (Nakamura et al., 2017).

However, in some cases they also suppressed cancer development. For example, TBX4, which is highly associated with SEs, was downregulated in lung cancer-associated fibroblasts (Horie et al., 2018). DNA hypermethylation suppressed some SEs in squamous cancer cells, whose downstream genes, such as SMGs, CUL3, and ZFP36L2, are important tumor-suppressors specific to the OSCC subtype (Lin et al., 2018).

Gene mutation, gene fusion, and aberrant expression of oncogenes or TFs activate SEs and ultimately lead to tumorigenesis (Johnatty et al., 2015; Garcia-Carpizo et al., 2016; Babu and Fullwood, 2017; Andricovich et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2018). Besides, translocation, 5hmC modification, methylation profile shifts, or 3D contact domain formation of SEs also lead to cancer development (Xiang et al., 2014; Hu H. et al., 2017; Weischenfeldt et al., 2017). The effect of SE blockers have been tested in various cancers, including the testing of THZ1 in esophageal cancer, iBET72 in cervical cancer, and JQ1 in cervical cancer, colorectal carcinoma, colon cancer, and squamous cell carcinoma (Dooley et al., 2016; Togel et al., 2016; Jiang Y.Y. et al., 2017; Nakamura et al., 2017). Thus, they could potentially be used as biomarkers or therapeutic targets in the future.

SEs in Other Cancers

Table 4 summarizes the regulation and roles of SEs in other tumors.

Table 4.

SEs’ roles in other cancers.

| Cancer type† | Phenotype‡ | Upstream (O/S) and potential therapeutic targets§ | Regulation of SEs | Downstream | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNBC | A, P, G | CDK7i: THZ1 (S) | ↓ | EGFR, FOSL1, FOXC1… | Wang et al., 2015 |

| TNBC | A, P | BETi: JQ1 (S) | Not involved | mitosis regulator LIN9 | Sahni et al., 2017 |

| BC | DR | AI (O) | ↑ | FOXO1, FOXA1, FOXA2… | Nguyen et al., 2015 |

| BC | T, D | GER (O) | ↑ | KDM6A, EN1, TBX18… | Su et al., 2015 |

| BC | IE | TNF-NFKB1 pathway (O) | ↑ | CD47 | Betancur et al., 2017 |

| BC | NM | RTD (O) | ↑ | ESR1, MYC | Glodzik et al., 2017 |

| BC | DR | AKTi/FOXO3a/BRD4 axis (0) | ↑ | CDK6 | Liu et al., 2018 |

| BC | DR | apoERalpha (O) | ↑ | DSCAM-AS1 | Miano et al., 2018 |

| PC, PGL | NM | GR (O) | translocated on | TERT | Dwight et al., 2018 |

| ACC | P | NM | translocated on | MYB | Drier et al., 2016 |

| SCC | P, PG | Ets2, Elk3 (O) | ↑ | Ets2, Elk3, Fos, Junb, Klf5 | Yang et al., 2015 |

| SCC | NM | UVR (O) | formation | CYP24A1, GJA5, SLAMF7 | Shen et al., 2017 |

| MO | G, P | BETi: JQ1 (S) | ↓ | PGC-1α | Gelato et al., 2018 |

| NPC | G | BETi: JQ1 (S) | ↓ | ETV6 | Ke et al., 2017 |

| NPC | P, A | CDK7i: THZ1 (S); ETS2, MAFK, TEAD1 (O) | ↓/↑ | BCAR1, F3, LDLR, TBC1D2G1 | Yuan et al., 2017 |

| Cancers | TG | NM | deletion | MYC | Dave et al., 2017 |

| Cancers | P, M, I | NM | NM | linc00152 | Xu et al., 2017 |

| Cancers | NM | TADs boundaries (O) | insulated and co-duplicated | CTCF | Gong et al., 2018 |

†Abbreviation for cancers: ACC, adenoid cystic carcinoma; BC, breast cancer; MO, melanoma; NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; PC, pheochromocytomas; PGL, paragangliomas; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer. ‡Abbreviation for phenotypes: A, apoptosis; D, differentiation; DR, drug-resistance; G, growth; I, invasion; IE, immune escape; M, migration; NM, not mentioned; P, proliferation; PG, progression; T, transformation; TG, tumorigenesis. §Abbreviation for molecules: AI, aromatase inhibitor; apoERalpha, ligands Estrogen receptor-alpha; BETi, Bromodomain inhibitor; CDK7i, CDK7 inhibitor; GER, genome epigenetic reprogramming; GR, genomic rearrangements; NM, not mentioned; O, oncogenic molecule; S, suppressor of cancer; RTD, Recurrent tandem duplications; TADs, topologically associating domains; TF, transcription factor; UVR, ultraviolet radiation.

Super-enhancer-associated mechanisms involved in other cancers include genomic rearrangements in pheochromocytomas, genome epigenetic reprogramming and recurrent tandem duplication in breast cancer, and ultraviolet radiation and aberrant activation of proto-oncogene in squamous cell carcinoma (Su et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015; Betancur et al., 2017; Glodzik et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017; Dwight et al., 2018). Besides, Drier et al. (2016) found that translocation of SEs upregulated MYB in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Similarly, Dwight et al. (2018) reported that translocation of SEs promoted the expression of TERT in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Besides, formation of SEs upregulated several genes, such as CYP24A1, GJA5, SLAMF7, and ETV1, in squamous cell carcinoma (Shen et al., 2017), and deletion of SEs could lead to downregulation of MYC in several tumors. (Dave et al., 2017) In addition, SEs that are flanked by strong topologically associating domains (TAD) may be exploited as a functional unit to promote gene expression, and strong TAD boundaries and SE elements are frequently co-duplicated in cancer cells (Gong et al., 2018). All these studies further deepened our understanding about the mechanism of action of SE in cancers and provided novel possible targets for anti-tumor therapy.

Several researchers have widely used SE blockers to illustrate the implication of SEs in cancers. Wang et al. (2015), Sahni et al. (2017) investigated and verified the efficacy of THZ1 and JQ1 to inhibit proliferation and promote apoptosis of cancer cells in triple-negative breast cancer model. Similarly, Ke et al. (2017), Yuan et al. (2017) used nasopharyngeal carcinoma model to explore the efficacy of JQ1 and THZ1, and found significant inhibition of proliferation and enhancement of apoptosis. JQ1 was also reported to reduce the cell proliferation in melanoma model (Gelato et al., 2018). However, it is noteworthy that sometimes BETi could still function without participation of SEs. Sahni et al. (2017) reported that in triple-negative breast cancer, the mitosis regulator, LIN9, was often amplified and overexpressed. Although, it lacked a related SE, BETi could decrease its expression and inhibit mitosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Donati et al. (2018) reported that BRD4 participates in the activation and repair of DNA damage checkpoints and telomere maintenance. Therefore, in addition to blocking the function of SE, BETi can also inhibit tumorigenesis via other mechanisms, such as hindering the repair of DNA damage. This raised a question about the reliability of SEs’ roles in cancers illustrated by BETi mechanism of action in previous studies. Did the function of BETi really arise from the inhibition of SEs, or actually they work through some other pathways? We still cannot draw a definite conclusion.

Notably, SEs are involved in the drug resistance of breast cancer cells. (Nguyen et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018; Miano et al., 2018). Although it is still not sure whether SE blockers can reverse drug resistance, they may be good research targets to find novel drugs to treat drug-resistant tumors.

Regulation of SEs by Tumor-Associated Viruses

Table 5 summarizes the regulation of SEs by cancer-related viruses.

Table 5.

regulations of SEs by tumor-associated viruses.

| Virus† | Phenotype‡ | Upstream (O/S) and potential therapeutic targets§ | Regulation of SEs | Downstream | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV | P | BETi: JQ1, iBET72 (S) | ↓ | E6 and E7 | Dooley et al., 2016 |

| HPV | NM | KDM5C (S) | ↓ | EGFR, c-MET | Chen et al., 2018 |

| HPV | NM | NM | SELE formation | E6/E7 | Warburton et al., 2018 |

| EBV | G | EBNA2 (O) | ↑ | RUNX3, RUNX1 | Gunnell et al., 2016 |

| EBV | P, G | EBV nuclear antigens (O) | ↑ | MCL1, IRF4, EBF, MYC | Jiang S. et al., 2017 |

†Abbreviation for viruses: EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HPV, human papillomavirus. ‡Abbreviation for phenotypes: G, growth; NM, not mentioned; P, proliferation. §Abbreviation for molecules: BETi, Bromodomain inhibitor; NM, not mentioned; O, oncogenic molecule; S, suppressor of cancer; SELE, super-enhancer-like element.

Some virus-induced SE alteration in abovementioned cancers were discussed in corresponding parts of this review. Other studies, that did not involve specific tumors, found that SEs generally promoted tumorigenesis in virus-related cancers. The carcinogenic potential of viruses could arise from aberrant activation of host genes as well as integration of viral genes, both requiring the participation of SEs (Dooley et al., 2016; Gunnell et al., 2016; Jiang S. et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018; Warburton et al., 2018). These results implied potential application of SE blockers to treat patients with high cancer risk from virus infection.

Future Directions

Super-enhancers refer to a class of regulatory regions with unusually strong enrichment of the binding sites for transcriptional co-activators. Although the roles of individual SEs vary with downstream genes, their overall effect in a particular tumor is relatively stable. In most of the cancer cases, SEs act as oncogenes to promote tumor growth. Therefore, SEs could be a promising therapeutic target in those cancers.

Several studies to investigate the potential of SEs as therapeutic targets have been conducted. Some researchers reported the existence of positive feedback loops. For example, Ets2 and Elk3 genes in squamous cell carcinoma can upregulate specific SEs (Yang et al., 2015). This not only intensified the function of the downstream genes, but also indicated potentially more sensitive responses to SE blockers. Besides, CDK7i showed striking selectivity in regression of neuroblastoma cells, without significant systemic toxicity (Chipumuro et al., 2014). In addition, some key downstream molecules and pathways of SEs are involved in various tumors, making them promising therapeutic targets for multiple cancers (Xu et al., 2017). Importantly, the effect of BETi has been proven in some virus-induced tumors models. For example, JQ1 and iBET72 could inhibit proliferation of cervical neoplasia induced by HPV (Dooley et al., 2016). Thus, SE blockers may have the potential to treat virus-induced cancer as well as patients with high cancer risk from virus infection. According to these studies, SEs have good prospects as potential therapeutic targets for cancers because of their strong potency, high selectivity, and broad applicability (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Regulation and therapeutic targets of SEs in cancers. On the whole, SEs can be activated by various genetic alterations including gene mutation, gene rearrangement, aberrant activation of genes and virus infection (Northcott et al., 2014; Kandaswamy et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2018; Dwight et al., 2018; Ott et al., 2018). In addition, activation, translation, duplication, formation, and deletion of SEs will also lead to abnormal transcription and cancer development (Xiang et al., 2014; Babu and Fullwood, 2017; Dave et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017; Gong et al., 2018). Besides, acetyltransferase (AcT), like CREBBP/EP300, strengthens the function of BRD4 by promoting chromatin acetylation (Garcia-Carpizo et al., 2018). Demethylases (DMe), such as KDM5C, KDM6A, and lysine-specific demethylase 1 inhibitors (LSD1i), can suppress SEs via demethylation (Sugino et al., 2017; Andricovich et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2018). On the contrary, MLL4, a H3K4 methyltransferase, helps to maintain broad H3K4me3 and SEs (Dhar et al., 2018). SMARCB1, a core subunit of the SWI/SNF (BAF) chromatin-remodeling complex, helps stabilize TFs (Wang et al., 2017). MEK inhibition opens chromatin and establishes super-enhancers at genes required for late myogenic differentiation, through ERK2/MYOG pathways (Yohe et al., 2018). AKT inhibitors (AKTi) induce FOXO3a acetylation as well as BRD4 recognition (Liu et al., 2018). Although SEs generally upregulate oncogene expression, in some cases, they also promote the expression of tumor suppressor genes (Pelish et al., 2015).

However, although the roles of SEs have been validated in many cancer cells, the degree of their involvement is still controversial. The main mechanism of action of BETi is considered to be blocking of the interaction between SEs and BRD4, which is a co-activator that can bind acetylated histones in SEs and TFs and directly interact with the mediator complex and elongation factors (Dawson et al., 2011). However, some target genes of BETi, such as LIN9 gene in triple-negative breast cancer, do not possess any corresponding SEs sites (Sahni et al., 2017). In addition, some researchers have proposed a non-transcriptional role of BRD4 in activation and repair of DNA damage checkpoints and telomere maintenance, opening new perspectives on the use of BETi in cancer (Donati et al., 2018). Similarly, other than inhibiting SEs, THZ1 can also cause defects in Pol II phosphorylation, co-transcriptional capping, promoter proximal pausing, and productive elongation (Nilson et al., 2015). Therefore, the roles of SEs in the above-mentioned cancers, illustrated by BETi and CDK7i, are still unclear. Besides, it is noteworthy that targeting SEs for cancer treatment might cause significant side effects because some tumor suppressor genes will also be suppressed when blocking SEs. Therefore, more studies and better understanding of mechanisms are urgently needed before SEs could be utilized as therapeutic targets to treat specific cancers.

Therefore, for future studies of SEs, the focus could be:

-

simple (1)

SEs are cell-type-specific and have the potential to be used for identification of different subtypes of cancer. Therefore, their application in precision medicine is promising. In the future studies, researchers could try to use them to distinguish subtypes of cancer and give more precise treatment strategy.

-

simple (2)

For cancers that lack known genetic drivers and are recalcitrant to therapeutic development, SE sequencing and investigation may provide novel directions for significant breakthroughs.

-

simple (3)

In addition to blocking BRD4, other mechanisms of BETi are worth studying to validate the previous conclusions or obtain new explanation for the reported results.

-

simple (4)

The interactions between SEs and virus infection need further research. A better understanding of them might benefit not only the virus-related cancer patients, but also those who have high risk of cancer due to virus infection.

-

simple (5)

Epigenetic changes on SEs can also lead to significant differences in phenotypes. Therefore, the combination of SEs and epigenetics (such as DNA methylation and acetylation) could be good research topics.

-

simple (6)

Some BETi have been put into clinical trials, such as OTX015 in multiple myeloma and acute leukemia. The practical application of BETi in other tumors awaits further exploration.

Author Contributions

YH and WL searched and wrote the manuscript. QL revised the manuscript and supervision of the entire project.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2014BAI04B02) and grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81802974).

References

- Amorim S., Stathis A., Gleeson M., Iyengar S., Magarotto V., Leleu X., et al. (2016). Bromodomain inhibitor OTX015 in patients with lymphoma or multiple myeloma: a dose-escalation, open-label, pharmacokinetic, phase 1 study. Lancet Haematol. 3 e196–e204. 10.1016/s2352-3026(16)00021-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andricovich J., Perkail S., Kai Y., Casasanta N., Peng W., Tzatsos A. (2018). Loss of KDM6A activates super-enhancers to induce gender-specific squamous-like pancreatic cancer and confers sensitivity to BET inhibitors. Cancer Cell 33 512.e8–526.e8. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu D., Fullwood M. J. (2017). Expanding the effects of ERG on chromatin landscapes and dysregulated transcription in prostate cancer. Nat. Genet. 49 1294–1295. 10.1038/ng.3944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji J., Rusconi S., Schaffner W. (1981). Expression of a beta-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell 27 299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthon C., Raffoux E., Thomas X., Vey N., Gomez-Roca C., Yee K., et al. (2016). Bromodomain inhibitor OTX015 in patients with acute leukaemia: a dose-escalation, phase 1 study. Lancet Haematol. 3 e186–e195. 10.1016/s2352-3026(15)00247-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur P. A., Abraham B. J., Yiu Y. Y., Willingham S. B., Khameneh F., Zarnegar M., et al. (2017). A CD47-associated super-enhancer links pro-inflammatory signalling to CD47 upregulation in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 8:14802. 10.1038/ncomms14802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradner J. E., Hnisz D., Young R. A. (2017). Transcriptional addiction in cancer. Cell 168 629–643. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulger M., Groudine M. (2011). Functional and mechanistic diversity of distal transcription enhancers. Cell 144 327–339. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao F., Fang Y., Tan H. K., Goh Y., Choy J. Y. H., Koh B. T. H., et al. (2017). Super-enhancers and broad h3k4me3 domains form complex gene regulatory circuits involving chromatin interactions. Sci. Rep. 7:2186. 10.1038/s41598-017-02257-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter D., Chakalova L., Osborne C. S., Dai Y. F., Fraser P. (2002). Long-range chromatin regulatory interactions in vivo. Nat. Genet. 32 623–626. 10.1038/ng1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceribelli M., Hou Z. E., Kelly P. N., Huang D. W., Wright G., Ganapathi K., et al. (2016). A druggable TCF4- and BRD4-dependent transcriptional network sustains malignancy in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Cancer Cell 30 764–778. 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Chen Z., Wu D., Zhang L., Lin X., Su J., et al. (2015). Broad H3K4me3 is associated with increased transcription elongation and enhancer activity at tumor-suppressor genes. Nat. Genet. 47 1149–1157. 10.1038/ng.3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Loo J. X., Shi X., Xiong W., Guo Y., Ke H., et al. (2018). E6 protein expressed by high-risk HPV activates super-enhancers of the EGFR and c-MET oncogenes by destabilizing the histone demethylase KDM5C. Cancer Res. 78 1418–1430. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-17-2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipumuro E., Marco E., Christensen C. L., Kwiatkowski N., Zhang T., Hatheway C. M., et al. (2014). CDK7 inhibition suppresses super-enhancer-linked oncogenic transcription in MYCN-driven cancer. Cell 159 1126–1139. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave K., Sur I., Yan J., Zhang J., Kaasinen E., Zhong F., et al. (2017). Mice deficient of Myc super-enhancer region reveal differential control mechanism between normal and pathological growth. eLife 6:e23382. 10.7554/eLife.23382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M. A., Gudgin E. J., Horton S. J., Giotopoulos G., Meduri E., Robson S., et al. (2014). Recurrent mutations, including NPM1c, activate a BRD4-dependent core transcriptional program in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 28 311–320. 10.1038/leu.2013.338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M. A., Prinjha R. K., Dittmann A., Giotopoulos G., Bantscheff M., Chan W. I., et al. (2011). Inhibition of BET recruitment to chromatin as an effective treatment for MLL-fusion leukaemia. Nature 478 529–533. 10.1038/nature10509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaesteker B., Denecker G., Van Neste C., Dolman E. M., Van Loocke W., Gartlgruber M., et al. (2018). TBX2 is a neuroblastoma core regulatory circuitry component enhancing MYCN/FOXM1 reactivation of DREAM targets. Nat. Commun. 9:4866. 10.1038/s41467-018-06699-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar S. S., Zhao D., Lin T., Gu B., Pal K., Wu S. J., et al. (2018). MLL4 is required to maintain broad H3K4me3 peaks and super-enhancers at tumor suppressor genes. Mol. Cell 70 825.e6–841.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donati B., Lorenzini E., Ciarrocchi A. (2018). BRD4 and cancer: going beyond transcriptional regulation. Mol. Cancer 17:164. 10.1186/s12943-018-0915-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley K. E., Warburton A., McBride A. A. (2016). Tandemly integrated HPV16 can form a Brd4-dependent super-enhancer-like element that drives transcription of viral oncogenes. mBio 7:e1446–e1416. 10.1128/mBio.01446-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drier Y., Cotton M. J., Williamson K. E., Gillespie S. M., Ryan R. J., Kluk M. J., et al. (2016). An oncogenic MYB feedback loop drives alternate cell fates in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 48 265–272. 10.1038/ng.3502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight T., Flynn A., Amarasinghe K., Benn D. E., Lupat R., Li J., et al. (2018). TERT structural rearrangements in metastatic pheochromocytomas. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 25 1–9. 10.1530/erc-17-0306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis J. M., Zhang C. Z., Maire C. L., Jung J., Manzo V. E., Adalsteinsson V. A., et al. (2014). EGFR variant heterogeneity in glioblastoma resolved through single-nucleus sequencing. Cancer Discov. 4 956–971. 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-13-0879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Carpizo V., Ruiz-Llorente S., Sarmentero J., Grana-Castro O., Pisano D. G., Barrero M. J. (2018). CREBBP/EP300 bromodomains are critical to sustain the GATA1/MYC regulatory axis in proliferation. Epigenet. Chrom. 11:30. 10.1186/s13072-018-0197-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Carpizo V., Sarmentero J., Han B., Grana O., Ruiz-Llorente S., Pisano D. G., et al. (2016). NSD2 contributes to oncogenic RAS-driven transcription in lung cancer cells through long-range epigenetic activation. Sci. Rep. 6:32952. 10.1038/srep32952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelato K. A., Schockel L., Klingbeil O., Ruckert T., Lesche R., Toedling J., et al. (2018). Super-enhancers define a proliferative PGC-1alpha-expressing melanoma subgroup sensitive to BET inhibition. Oncogene 37 512–521. 10.1038/onc.2017.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach D., Tontsch-Grunt U., Baum A., Popow J., Scharn D., Hofmann M. H., et al. (2018). The novel BET bromodomain inhibitor BI 894999 represses super-enhancer-associated transcription and synergizes with CDK9 inhibition in AML. Oncogene 37 2687–2701. 10.1038/s41388-018-0150-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glodzik D., Morganella S., Davies H., Simpson P. T., Li Y., Zou X., et al. (2017). A somatic-mutational process recurrently duplicates germline susceptibility loci and tissue-specific super-enhancers in breast cancers. Nat. Genet. 49 341–348. 10.1038/ng.3771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y., Lazaris C., Sakellaropoulos T., Lozano A., Kambadur P., Ntziachristos P., et al. (2018). Stratification of TAD boundaries reveals preferential insulation of super-enhancers by strong boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9:542. 10.1038/s41467-018-03017-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan R., Matta H., Tolani B., Triche T., Jr., Chaudhary P. M. (2016). Immunomodulatory drugs target IKZF1-IRF4-MYC axis in primary effusion lymphoma in a cereblon-dependent manner and display synergistic cytotoxicity with BRD4 inhibitors. Oncogene 35 1797–1810. 10.1038/onc.2015.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell A., Webb H. M., Wood C. D., McClellan M. J., Wichaidit B., Kempkes B., et al. (2016). RUNX super-enhancer control through the notch pathway by epstein-barr virus transcription factors regulates B cell growth. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 4636–4650. 10.1093/nar/gkw085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajmirza A., Emadali A., Gauthier A., Casasnovas O., Gressin R., Callanan M. B. (2018). BET family protein BRD4: an emerging actor in NFkappaB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Biomedicines 6:16. 10.3390/biomedicines6010016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Zhang X., Zhang J., Zhang R., Yang T., Zhu J., et al. (2018). LMO1 super-enhancer polymorphism rs2168101 G>T correlates with decreased neuroblastoma risk in chinese children. J. Cancer 9 1592–1597. 10.7150/jca.24326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henssen A., Althoff K., Odersky A., Beckers A., Koche R., Speleman F., et al. (2016). Targeting MYCN-driven transcription by BET-bromodomain inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 22 2470–2481. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-15-1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz D., Ambesi-Impiombato A., Palomero T., Schnell S. A., Belver L., Wendorff A. A., et al. (2014). A NOTCH1-driven MYC enhancer promotes T cell development, transformation and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Med. 20 1130–1137. 10.1038/nm.3665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz D., Abraham B. J., Lee T. I., Lau A., Saint-Andre V., Sigova A. A., et al. (2013). Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell 155 934–947. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie M., Miyashita N., Mikami Y., Noguchi S., Yamauchi Y., Suzukawa M., et al. (2018). TBX4 is involved in the super-enhancer-driven transcriptional programs underlying features specific to lung fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 314 L177–L191. 10.1152/ajplung.00193.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Shu M., He L., Yu X., Liu X., Lu Y., et al. (2017). Epigenomic landscape of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine reveals its transcriptional regulation of lncRNAs in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 116 658–668. 10.1038/bjc.2016.457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Yoshida T., Georgopoulos K. (2017). Transcriptional circuits in B cell transformation. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 24 345–352. 10.1097/moh.0000000000000352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Zhou H., Liang J., Gerdt C., Wang C., Ke L., et al. (2017). The epstein-barr virus regulome in lymphoblastoid cells. Cell Host Microbe 22 561.e4–573.e4. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y. Y., Lin D. C., Mayakonda A., Hazawa M., Ding L. W., Chien W. W., et al. (2017). Targeting super-enhancer-associated oncogenes in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gut 66 1358–1368. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnatty S. E., Tyrer J. P., Kar S., Beesley J., Lu Y., Gao B., et al. (2015). Genome-wide analysis identifies novel loci associated with ovarian cancer outcomes: findings from the ovarian cancer association consortium. Clin. Cancer Res. 21 5264–5276. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-15-0632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. C., Houseman E. A., King J. E., von Herrmann K. M., Fadul C. E., Christensen B. C. (2016). 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine localizes to enhancer elements and is associated with survival in glioblastoma patients. Nat. Commun. 7:13177. 10.1038/ncomms13177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandaswamy R., Sava G. P., Speedy H. E., Bea S., Martin-Subero J. I., Studd J. B., et al. (2016). Genetic predisposition to chronic lymphocytic leukemia is mediated by a BMF super-enhancer polymorphism. Cell Rep. 16 2061–2067. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katerndahl C. D. S., Heltemes-Harris L. M., Willette M. J. L., Henzler C. M., Frietze S., Yang R., et al. (2017). Antagonism of B cell enhancer networks by STAT5 drives leukemia and poor patient survival. Nat. Immunol. 18 694–704. 10.1038/ni.3716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke L., Zhou H., Wang C., Xiong G., Xiang Y., Ling Y., et al. (2017). Nasopharyngeal carcinoma super-enhancer-driven ETV6 correlates with prognosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 9683–9688. 10.1073/pnas.1705236114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoechel B., Bhatt A., Pan L., Pedamallu C. S., Severson E., Gutierrez A., et al. (2015). Complete hematologic response of early T-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia to the gamma-secretase inhibitor BMS-906024: genetic and epigenetic findings in an outlier case. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 1:a000539. 10.1101/mcs.a000539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski N., Zhang T., Rahl P. B., Abraham B. J., Reddy J., Ficarro S. B., et al. (2014). Targeting transcription regulation in cancer with a covalent CDK7 inhibitor. Nature 511 616–620. 10.1038/nature13393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liau W. S., Tan S. H., Ngoc P. C. T., Wang C. Q., Tergaonkar V., Feng H., et al. (2017). Aberrant activation of the GIMAP enhancer by oncogenic transcription factors in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 31 1798–1807. 10.1038/leu.2016.392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D. C., Dinh H. Q., Xie J. J., Mayakonda A., Silva T. C., Jiang Y. Y., et al. (2018). Identification of distinct mutational patterns and new driver genes in oesophageal squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas. Gut 67 1769–1779. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Duan Z., Guo W., Zeng L., Wu Y., Chen Y., et al. (2018). Targeting the BRD4/FOXO3a/CDK6 axis sensitizes AKT inhibition in luminal breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 9:5200. 10.1038/s41467-018-07258-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loven J., Hoke H. A., Lin C. Y., Lau A., Orlando D. A., Vakoc C. R., et al. (2013). Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell 153 320–334. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Walsh M. J., Bernhardt K., Ashbaugh C. W., Trudeau S. J., Ashbaugh I. Y., et al. (2017). CRISPR/Cas9 screens reveal epstein-barr virus-transformed B cell host dependency factors. Cell Host Microbe 21 580.e7–591.e7. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack S. C., Pajtler K. W., Chavez L., Okonechnikov K., Bertrand K. C., Wang X., et al. (2018). Therapeutic targeting of ependymoma as informed by oncogenic enhancer profiling. Nature 553 101–105. 10.1038/nature25169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng W., Wang J., Wang B., Liu F., Li M., Zhao Y., et al. (2018). CDK7 inhibition is a novel therapeutic strategy against GBM both in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Manag. Res. 10 5747–5758. 10.2147/cmar.s183696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miano V., Ferrero G., Rosti V., Manitta E., Elhasnaoui J., Basile G., et al. (2018). Luminal lncRNAs regulation by ERalpha-controlled enhancers in a ligand-independent manner in breast cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:E593. 10.3390/ijms19020593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., Hattori N., Iida N., Yamashita S., Mori A., Kimura K., et al. (2017). Targeting of super-enhancers and mutant BRAF can suppress growth of BRAF-mutant colon cancer cells via repression of MAPK signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 402 100–109. 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V. T., Barozzi I., Faronato M., Lombardo Y., Steel J. H., Patel N., et al. (2015). Differential epigenetic reprogramming in response to specific endocrine therapies promotes cholesterol biosynthesis and cellular invasion. Nat. Commun. 6:10044. 10.1038/ncomms10044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilson K. A., Guo J., Turek M. E., Brogie J. E., Delaney E., Luse D. S., et al. (2015). THZ1 reveals roles for Cdk7 in co-transcriptional capping and pausing. Mol. Cell 59 576–587. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitulescu I. I., Meyer S. C., Wen Q. J., Crispino J. D., Lemieux M. E., Levine R. L., et al. (2017). Mediator kinase phosphorylation of STAT1 S727 promotes growth of neoplasms With JAK-STAT activation. EBioMedicine 26 112–125. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcott P. A., Lee C., Zichner T., Stutz A. M., Erkek S., Kawauchi D., et al. (2014). Enhancer hijacking activates GFI1 family oncogenes in medulloblastoma. Nature 511 428–434. 10.1038/nature13379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott C. J., Federation A. J., Schwartz L. S., Kasar S., Klitgaard J. L., Lenci R., et al. (2018). Enhancer architecture and essential core regulatory circuitry of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell 34 982.e7–995.e7. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelish H. E., Liau B. B., Nitulescu I. I., Tangpeerachaikul A., Poss Z. C., Da Silva D. H., et al. (2015). Mediator kinase inhibition further activates super-enhancer-associated genes in AML. Nature 526 273–276. 10.1038/nature14904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L., Jiang B., Yuan X., Qiu Y., Peng J., Huang Y., et al. (2018). Super-enhancer-associated long non-coding RNA HCCL5 is activated by ZEB1 and promotes the malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 79 572–584. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-18-0367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahni J. M., Gayle S. S., Webb B. M., Weber-Bonk K. L., Seachrist D. D., Singh S., et al. (2017). Mitotic vulnerability in triple-negative breast cancer associated with LIN9 Is targetable with BET inhibitors. Cancer Res 77 5395–5408. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-17-1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., George R. E. (2017). Super-enhancer-driven transcriptional dependencies in cancer. Trends Cancer 3 269–281. 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Stanislauskas M., Li G., Zheng D., Liu L. (2017). Epigenetic and genetic dissections of UV-induced global gene dysregulation in skin cells through multi-omics analyses. Sci. Rep. 7:42646. 10.1038/srep42646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H. Y. (2018). Targeting super-enhancers for disease treatment and diagnosis. Mol. Cells 41 506–514. 10.14348/molcells.2018.2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y., Subedee A., Bloushtain-Qimron N., Savova V., Krzystanek M., Li L., et al. (2015). Somatic cell fusions reveal extensive heterogeneity in basal-like breast cancer. Cell Rep. 11 1549–1563. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugino N., Kawahara M., Tatsumi G., Kanai A., Matsui H., Yamamoto R., et al. (2017). A novel LSD1 inhibitor NCD38 ameliorates MDS-related leukemia with complex karyotype by attenuating leukemia programs via activating super-enhancers. Leukemia 31 2303–2314. 10.1038/leu.2017.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togel L., Nightingale R., Chueh A. C., Jayachandran A., Tran H., Phesse T., et al. (2016). Dual targeting of bromodomain and extraterminal domain proteins, and WNT or MAPK signaling, inhibits c-MYC expression and proliferation of colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 15 1217–1226. 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-15-0724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentijn L. J., Koster J., Zwijnenburg D. A., Hasselt N. E., van Sluis P., Volckmann R., et al. (2015). TERT rearrangements are frequent in neuroblastoma and identify aggressive tumors. Nat. Genet. 47 1411–1414. 10.1038/ng.3438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Lee R. S., Alver B. H., Haswell J. R., Wang S., Mieczkowski J., et al. (2017). SMARCB1-mediated SWI/SNF complex function is essential for enhancer regulation. Nat. Genet. 49 289–295. 10.1038/ng.3746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhang T., Kwiatkowski N., Abraham B. J., Lee T. I., Xie S., et al. (2015). CDK7-dependent transcriptional addiction in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell 163 174–186. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton A., Redmond C. J., Dooley K. E., Fu H., Gillison M. L., Akagi K., et al. (2018). HPV integration hijacks and multimerizes a cellular enhancer to generate a viral-cellular super-enhancer that drives high viral oncogene expression. PLoS Genet 14:e1007179. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weischenfeldt J., Dubash T., Drainas A. P., Mardin B. R., Chen Y., Stutz A. M., et al. (2017). Pan-cancer analysis of somatic copy-number alterations implicates IRS4 and IGF2 in enhancer hijacking. Nat. Genet. 49 65–74. 10.1038/ng.3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang J. F., Yin Q. F., Chen T., Zhang Y., Zhang X. O., Wu Z., et al. (2014). Human colorectal cancer-specific CCAT1-L lncRNA regulates long-range chromatin interactions at the MYC locus. Cell Res. 24 513–531. 10.1038/cr.2014.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J. J., Jiang Y. Y., Jiang Y., Li C. Q., Lim M. C., An O., et al. (2018). Super-enhancer-driven long non-coding RNA LINC01503, regulated by TP63, is over-expressed and oncogenic in squamous cell carcinoma. Gastroenterology 154 2137.e1–2151.e1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Wan L., Yin H., Xu H., Zheng W., Shen M., et al. (2017). Long noncoding RNA linc00152 functions as a tumor propellant in pan-cancer. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 44 2476–2490. 10.1159/000486170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Schramek D., Adam R. C., Keyes B. E., Wang P., Zheng D., et al. (2015). ETS family transcriptional regulators drive chromatin dynamics and malignancy in squamous cell carcinomas. eLife 4:e10870. 10.7554/eLife.10870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohe M. E., Gryder B. E., Shern J. F., Song Y. K., Chou H. C., Sindiri S., et al. (2018). MEK inhibition induces MYOG and remodels super-enhancers in RAS-driven rhabdomyosarcoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 10:eaan4470. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan4470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J., Jiang Y. Y., Mayakonda A., Huang M., Ding L. W., Lin H., et al. (2017). Super-enhancers promote transcriptional dysregulation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 77 6614–6626. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-17-1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Vlasevska S., Wells V. A., Nataraj S., Holmes A. B., Duval R., et al. (2017). The CREBBP acetyltransferase is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor in B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Discov. 7 322–337. 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-16-1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]