Abstract

Bacteria-based biotechnology processes are constantly under threat from bacteriophage infection, with phage contamination being a non-neglectable problem for microbial fermentation. The essence of this problem is the complex co-evolutionary relationship between phages and bacteria. The development of phage control strategies requires further knowledge about phage-host interactions, while the widespread use of Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) in biotechnological processes makes the study of phage receptors in this strain particularly important. Here, eight phages infecting E. coli BL21 (DE3) via different receptors were isolated and subsequently identified as members of the genera T4virus, Js98virus, Felix01virus, T1virus, and Rtpvirus. Phage receptors were identified by whole-genome sequencing of phage-resistant E. coli strains and sequence comparison with wild-type BL21 (DE3). Results showed that the receptors for the isolated phages, designated vB_EcoS_IME18, vB_EcoS_IME253, vB_EcoM_IME281, vB_EcoM_IME338, vB_EcoM_IME339, vB_EcoM_IME340, vB_EcoM_IME341, and vB_EcoS_IME347 were FhuA, FepA, OmpF, lipopolysaccharide, Tsx, OmpA, FadL, and YncD, respectively. A polyvalent phage-resistant BL21 (DE3)-derived strain, designated PR8, was then identified by screening with a phage cocktail consisting of the eight phages. Strain PR8 is resistant to 23 of 32 tested phages including Myoviridae and Siphoviridae phages. Strains BL21 (DE3) and PR8 showed similar expression levels of enhanced green fluorescent protein. Thus, PR8 may be used as a phage resistant strain for fermentation processes. The findings of this study contribute significantly to our knowledge of phage-host interactions and may help prevent phage contamination in fermentation.

Keywords: Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3), phage contamination, phage-host interaction, phage resistance, phage receptors

Introduction

Bacteriophage, which were first discovered by Twort in 1915 and confirmed by d’Hérelle in 1917, are a highly diverse group of viruses that are ten times more abundant than their bacterial hosts in most environments (Brussow and Hendrix, 2002; Paez-Espino et al., 2016). As alternative antimicrobials, phages have been used to achieve effective bacterial control in various food, aquaculture, clinical, biotechnology, and other industries, especially for the treatment of drug-resistant strains (Salmond and Fineran, 2015). However, phage contamination is a non-neglectable problem for biotechnology- and food industry-based microbial fermentation processes, where the resulting losses can be catastrophic (Ogata, 1980; Marco et al., 2012). To address this, several effective phage monitoring systems and control measures have been developed and implemented in recent years, including control of contamination sources, rotation of different phage-resistant strains, genetic engineering strategies targeting different stages of phage infection, and phage control strategies based on the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas system (Sturino and Klaenhammer, 2006; Marco et al., 2012; Samson and Moineau, 2013).

There is a continuous co-evolutionary relationship between phages and their hosts, in which phage-resistant bacterial strains help preserve the bacterial lineage, with novel counter-resistant phages then threatening these strains (Labrie et al., 2010). Phage propagation involves several stages, including initial phage attachment to the surface of the host cell, followed by injection of phage nucleic acid into the host. The phage components are then synthesized intracellularly and packaged into self-assembling viral particles. Finally, an enzyme capable of degrading the bacterial cell wall is expressed, the bacteria are lysed, and the phage is released. Bacteria have evolved different phage resistance mechanisms, including prevention of phage adsorption, prevention of phage DNA entry, restriction/modification of phage nucleic acids, abortive infection systems and CRISPR-Cas systems (Hyman and Abedon, 2010; Labrie et al., 2010). Preventing phage adsorption is the first step in bacterial defense against phage, and includes mutations in phage receptors and production of extracellular matrices and competitive inhibitors (Hyman and Abedon, 2010; Labrie et al., 2010). Mutations in phage receptors are the most common way to prevent phage adsorption. Phage receptors located on the cell outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria are mainly outer membrane proteins (OMPs) and lipopolysaccharides (LPS), but can sometimes be flagellum, pilus, or capsular proteins (Bertozzi Silva et al., 2016). For example, OmpC is the receptor for both Myoviridae phage Me1 and Siphoviridae phage Gifsy-1 (Verhoef et al., 1977; Ho and Slauch, 2001), while the receptor for Myoviridae phages M1 and Ox2 is OmpA (Morona and Henning, 1984; Hashemolhosseini et al., 1994). Similarly, the receptor for Siphoviridae phages BF23 and SPN7C is outer membrane transport protein BtuB (Di et al., 1973; Shin et al., 2012), while LPS is recognized as the receptor for Podoviridae phage T3 and Myoviridae phage JG004 (Prehm et al., 1976; Boyke et al., 2011). The receptor for Siphoviridae phage iEPS5 is the flagellar molecular ruler protein FliK (Choi et al., 2012), while the receptor for Siphoviridae phage MP22 and Podoviridae phage MPK7 is the Type IV pilus (Heo et al., 2007; Bae and Cho, 2013). The bacterial capsule has been identified as the receptor for Myoviridae phage Vi I, Siphoviridae phage Vi II, and Podoviridae phage Vi III (Pickard et al., 2010). Interestingly, most Siphoviridae phages infecting Gram-negative bacteria require protein receptors for adsorption, while most Podoviridae phages require polysaccharides for the same process (Bertozzi Silva et al., 2016). Identification of phage receptors is the first step in studying phage-host interactions.

Escherichia coli is the most commonly used species in recombinant protein expression systems because such systems are rapid, simple, inexpensive, and allow large-scale production of target proteins. E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) was specifically designed for the overexpression of recombinant proteins. Understanding phage-host interactions, particularly the phage receptors of strain BL21 (DE3), is essential for the development of next-generation anti-phage strategies (Mahony and van Sinderen, 2015). However, the receptors of strain BL21 (DE3) have not been extensively studied. In previous work, we reported partial information about, and receptors for, phage vB_EcoS_IME347 (Li et al., 2018). Here, phages that recognize different receptors on BL21 (DE3) were sequentially screened and then combined in a “phage cocktail” to identify a polyvalent phage-resistant E. coli strain derived from BL21 (DE3). We confirmed that FhuA, FepA, OmpF, LPS, Tsx, OmpA, FadL, and YncD can be used as receptors by BL21 (DE3)-infecting phages. Together, our findings provide data support for phage-host interaction studies and will aid in the control of phage contamination of E. coli BL21 (DE3).

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

Bacteria and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The Sanger sequencing used in this study was completed by Beijing Tianyi Huiyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. E. coli strain BL21 (DE3; GenBank Accession No. CP001509) was stored at −70°C in 25% (v/v) glycerol. Plasmids pKDsg-ack, pCas9cr4, and pET-28a were stored at −20°C. All bacterial strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (tryptone, 10 g/L; yeast extract, 5 g/L; NaCl, 5 g/L). Medium was supplemented with agar (1.5%), soft agar (0.75%), 100 mg/L ampicillin (Amp), 50 mg/L spectinomycin (Spec), 50 mg/L kanamycin (Kana), or 100 μg/L anhydrotetracycline (aTc) when necessary.

Table 1.

Bacteria and plasmids used in this study.

| Bacteria and plasmids |

Description |

|

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Description | Source |

| Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) | Phage host strain | TransGen company |

| 18-R (18-R1, 18-R2, 18-R3) | Resistant mutant strains of phage vB_EcoS_IME18 | This study |

| 253-R (253-R1, 253-R2, 253-R3) | Resistant mutant strains of phage vB_EcoS_IME253 | This study |

| 281-R (281-R1, 281-R2, 281-R3) | Resistant mutant strains of phage vB_EcoM_IME281 | This study |

| 338-R (338-R1, 338-R2, 338-R3) | Resistant mutant strains of phage vB_EcoM_IME338 | This study |

| 339-R (339-R1, 339-R2, 339-R3) | Resistant mutant strains of phage vB_EcoM_IME339 | This study |

| 340-R (340-R1, 340-R2, 340-R3) | Resistant mutant strains of phage vB_EcoM_IME340 | This study |

| 341-R (341-R1, 341-R2, 341-R3) | Resistant mutant strains of phage vB_EcoM_IME341 | This study |

| 347-R (347-R1, 347-R2, 347-R3) | Resistant mutant strains of phage vB_EcoS_IME347 | This study |

| ΔtonB | Deletion mutants of tonB | This study |

| ΔfhuA | Deletion mutants of fhuA | This study |

| ΔfepA | Deletion mutants of fepA | This study |

| ΔompF | Deletion mutants of ompF | This study |

| ΔwaaG | Deletion mutants of waaG | This study |

| Δtsx | Deletion mutants of tsx | This study |

| ΔompA | Deletion mutants of ompA | This study |

| ΔfadL | Deletion mutants of fadL | This study |

| ΔyncD | Deletion mutants of yncD | This study |

| C-tonB | Complementary strains of tonB | This study |

| C-fhuA | Complementary strains of fhuA | This study |

| C-fepA | Complementary strains of fepA | This study |

| C-ompF | Complementary strains of ompF | This study |

| C-waaG | Complementary strains of waaG | This study |

| C-tsx | Complementary strains of tsx | This study |

| C-ompA | Complementary strains of ompA | This study |

| C-fadL | Complementary strains of fadL | This study |

| C-yncD | Complementary strains of yncD | This study |

| Plasmids | Description | Source |

| pCas9cr4 | For scarless Cas9 assisted recombineering (no-SCAR) system | Addgene (Plasmid #62655) |

| pKDsg-ack | For scarless Cas9 assisted recombineering (no-SCAR) system | Addgene (Plasmid #62654) |

| pKDsg-p15 | For scarless Cas9 assisted recombineering (no-SCAR) system | Addgene (Plasmid #62656) |

| pKDsg-tonB | Counter-selection plasmid for deletion of tonB | This study |

| pKDsg-fhuA | Counter-selection plasmid for deletion of fhuA | This study |

| pKDsg-fepA | Counter-selection plasmid for deletion of fepA | This study |

| pKDsg-ompF | Counter-selection plasmid for deletion of ompF | This study |

| pKDsg-waaG | Counter-selection plasmid for deletion of waaG | This study |

| pKDsg-tsx | Counter-selection plasmid for deletion of tsx | This study |

| pKDsg-ompA | Counter-selection plasmid for deletion of ompA | This study |

| pKDsg-fadL | Counter-selection plasmid for deletion of fadL | This study |

| pET-28a-tonB | Complementation plasmids for complementation of tonB | This study |

| pET-28a-fhuA | Complementation plasmids for complementation of fhuA | This study |

| pET-28a-fepA | Complementation plasmids for complementation of fepA | This study |

| pET-28a-ompF | Complementation plasmids for complementation of ompF | This study |

| pET-28a-waaG | Complementation plasmids for complementation of waaG | This study |

| pET-28a-tsx | Complementation plasmids for complementation of tsx | This study |

| pET-28a-ompA | Complementation plasmids for complementation of ompA | This study |

| pET-28a-fadL | Complementation plasmids for complementation of fadL | This study |

| pET-28a-egfp | Recombinant plasmid to identify differences in protein expression between polyvalent phage-resistant strain PR8 and E. coli BL21 (DE3) | This study |

Isolation and Purification of Phages and Screening of Bacteriophage-Insensitive Mutants

Phages specific to E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) were isolated from sewage samples collected from the State Key Laboratory of Pathogens and Biosecurity, Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology, Beijing, China. The sewage samples were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min and then filtered through a 0.22-μm pore size filter (Millipore, Burlington, MA, United States). Thereafter, 4 mL of the filtrate were mixed with 200 μL of log-phase BL21 (DE3) cells [optical density at 600 nm (OD600) = 0.6] and inoculated into 2 mL of 3 × LB medium before being incubated at 37°C, 220 rpm until clarification. The resulting culture suspension was filtered as above and the phages were cultured using the double-layer agar plate method as described previously (Jun et al., 2016). An individual plaque was picked for purification from three separate replicates. The purified phage particles were stored in LB medium containing 25% (v/v) glycerol at −80°C.

Log-phase BL21 (DE3) suspension (OD600 = 0.6, 300 μL) and phage suspensions (106 plaque-forming units [PFU]/mL, 100 μL) obtained in the above procedure were mixed with soft agar and then poured onto the surface of LB-agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 12–18 h or until colonies were produced on the plaques. Single bacterial colonies were obtained by streaking, and their sensitivity to phage infection was examined using a spotting assay and a double-layer agar plate method (McCutcheon et al., 2018). A single colony from plates on which no plaques were formed was selected as a potential bacteriophage-insensitive mutant (BIM).

Each phage and its BIMs was screened using an iterative mutagenesis method using a previous generation of BIMs as an indicator strain to screen the next generation of phage, and then screening for new BIMs (Supplementary Figure S1).

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Phage particles were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 1h then purified by CsCl gradient ultra-centrifugation to visualize phage morphology by TEM (Chen et al., 2018). A 20-μL aliquot of phage suspension was incubated on a carbon-coated copper grid for 15 min and then dried using filter paper. The copper grid covering the phages was then stained with 2% (w/v) phosphotungstic acid for 2 min. Finally, phage morphology was examined at 80 kV using a JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope (Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Optimal Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) and One-Step Growth Curve Analyses

The optimal MOI and one-step growth curves for isolated phages were determined using methods described previously (Wang et al., 2014). Briefly, phages were added to 5 mL of log-phase BL21 (DE3) culture (108 colony-forming units [CFU]/mL) to achieve a MOI of 10, 1, 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, or 0.0001, and then incubated at 37°C, 220 rpm for 4 h. Culture supernatant was then filtered through a 0.22-μm filter, and the titer of the phage in the supernatant was measured using a double-layer agar plate method. Three replicates were conducted for determination. The MOI resulting in the highest phage titer was considered the optimal MOI of the phage.

The one-step growth curve of a phage reflects dynamic changes in the number of particles during phage replication. To obtain a one-step growth curve for each of the isolated phages, phage suspension was added to 20 mL of log-phase BL21 (DE3) culture (107 CFU/mL) at the optimal MOI and incubated at 37°C for 5 min. The culture was then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 min and the supernatant discarded. The pellet was then washed twice with LB medium and re-suspended in 20 mL of LB medium. The moment when the pellet was re-suspended in medium was defined as time zero. Then, the resulting culture was transferred to a shaker and incubated at 37°C, 220 rpm for 1.5 h. Three duplicate samples (200 μL) were collected every 10 min to determine the phage titer at different time points. Three replicates were conducted for determination. The one-step growth curve was obtained by plotting phage titer against time. The burst size was calculated by dividing the plateau phage titer by the initial phage titer.

Gene Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

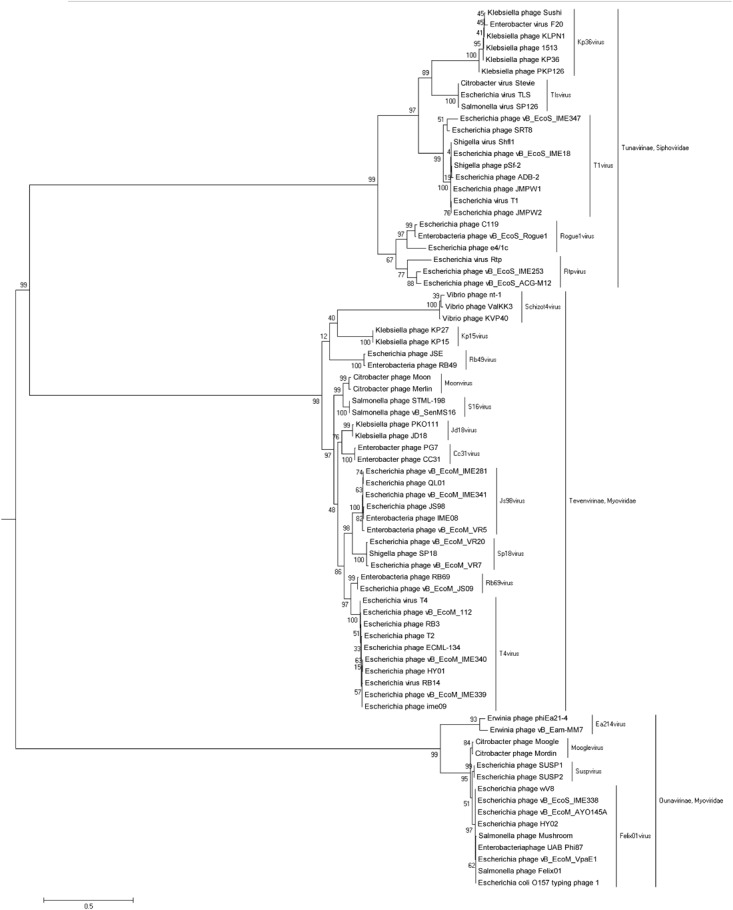

Phage genomic DNA was extracted using a modified phenol-chloroform extraction protocol (Zhang et al., 2017). A 2 × 300 nt paired-end DNA library was prepared with the NEBNext® UltraTM II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 150 ng of DNA were dissolved in deionized water to a final volume of 50 μl and disrupted to 300–400 bp fragments using a Bioruptor UCD-200TS ultrasound system. Then, the fragmented DNAs were end-repaired and adaptor ligated using NEBNext Ultra II End Prep Enzyme and Ligation Master Mix, respectively. Next, the adaptor-ligated DNA was selected and cleaned using EBNext Sample Purification Beads. Finally, the adaptor-ligated DNA was subjected to PCR amplification, and the PCR products were cleaned using EBNext Sample Purification Beads. Before sequencing, quality-control analysis for the constructed library was performed for fragment size distribution with a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies). Then, high-throughput sequencing of the DNA was performed on an Illumina MiSeq instrument (San Diego, CA, United States). Genomes were assembled from filtered high-quality reads using the assembly algorithm Newbler version 3.0 with default parameters. Open reading frame prediction and genome annotation were carried out using the RAST1 tool and NCBI nucleotide collection (non-redundant nr database) BLASTp alignment, respectively. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using 75 terminase large subunit protein sequences of different phages from the Ounavirinae, Tevenvirinae, and Tunavirinae subfamilies in the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses virus taxonomy current release. The alignment of phage terminase large subunit sequences was carried out using ClustalW in MEGA 6 software, and then phylogenetic analysis was performed using the maximum likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Genomic DNA was extracted from phage-resistant E. coli strains and phage-sensitive strain BL21 (DE3) using a High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Then, a 2 × 300 nt paired-end DNA library was constructed using the Illumina NEB Next® UltraTM II DNA library preparation kit and high-throughput sequencing was performed using Illumina MiSeq according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequence reads were mapped against the BL21 (DE3) reference genome (GenBank Accession No. CP001509.3) using CLC Genomics Workbench 9.0, followed by basic variant detection and gene deletion searches.

Phage Sensitivity Assay

The sensitivity of bacterial strains to phages was examined by the double-layer agar plate method and adsorption assays. Phage-sensitive strains were selected to determine their phage adsorption capacity. Briefly, log-phase (108 CFU/mL) bacterial culture (1 mL) was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 min and the pellet resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (0.9 mL). A 0.1 mL aliquot of phage solution (∼106 PFU/mL) was added to the cell suspension and the culture mixture was incubated at 37°C for 5 min to allow adsorption. In controls, LB medium was used instead of a cell suspension. Cultures were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 min and the titer of free phage in the supernatant was determined using the double-layer agar method. Three replicates were conducted for determination. The adsorption rate is estimated by k = (Ct − Pt)/P0/N/t, where k is the estimated adsorption rate; Pt and P0 is the phage concentration at time t and 0, respectively; Ct is the phage concentration in control group at the time t; N is the bacterial concentration.

Construction of Deletion Mutants

Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) tonB, fhuA, fepA, ompF, waaG, tsx, ompA, and fadL deletion mutants were constructed using the Scarless Cas9 Assisted Recombineering (no-SCAR) system (Reisch and Prather, 2015, 2017). The no-SCAR system consists of plasmids pKDsg-ack and pCas9cr4, which contain all components required for gene editing and do not require specific modification of the host. pCas9cr4 expresses Cas9 nuclease under the control of the Ptet promoter, while pKDsg-xxx has a single guide RNA (sgRNA) expressed under the control of Ptet as well as exo, bet, and gam genes, which constitute the λ-Red system, under the control of the arabinose-inducible promoter, ParaB (Reisch and Prather, 2015). Cas9 target recognition requires a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM, 5′-NGG-3′) next to the target site. Cas9 nuclease produces double-strand breaks in the genome at the target site under the guidance of the sgRNA, while the λ-Red system links the donor nucleic acid to the cut genome for gene editing.

The counter-selection plasmid pKDsg-xxx was reconstructed for Cas9 target specificity. The oligonucleotides used for recombination were designed as single-stranded DNA, and three phosphorothioate bonds were 5′-modified to prevent degradation. Briefly, the sgRNA sequence on plasmid pKDsg-xxx was designed using the online CRISPR gRNA design tool2 or by manual selection of 20-bp fragments of DNA at the 3′- end of the target gene PAM region. To incorporate this 20-bp sequence into pKDsg-xxx, a ligation-independent cloning technique known as circular polymerase extension cloning (CPEC) was performed (Quan and Tian, 2009). Amplification of two products with short, overlapping sequences on both ends was performed using Q5 HotStart High-Fidelity 2 × Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, United States) using pKDsg-ack as the template. The two linear DNA fragments were then assembled into plasmids using a pEASY-UniSeamless cloning and assembly kit (TransGen, Beijing, China) and transformed into Trans5α Chemically Competent Cells (TransGen). Transformed cells were incubated on LB agar containing 50 mg/L Spec for 12 h at 30°C. The presence of pKDsg-xxx in the transformants was confirmed by PCR. Plasmids were then extracted using a Plasmid Mini Kit (TaKaRa, Otsu, Japan).

Deletion mutant strains were then constructed as follows. First, plasmids pCas9cr4 and pKDsg-xxx were sequentially transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) by electroporation and selected using Amp and Spec, respectively. Transformed plasmids were verified by PCR. Next, BL21 (DE3) transformants containing pCas9cr4 and pKDsg-xxx were cultured to log phase for preparation of competent cells. Cells were incubated with 50 mM (final concentration) L-arabinose for 20–30 min before preparation of competent cells to induce expression of the λ-Red recombination system in pKDsg-xxx. Finally, the target oligonucleotide was electro transformed into the recombinant competent cells, which were then plated on LB-agar containing 100 mg/L Amp, 50 mg/L Spec, and 100 μg/L aTc, and incubated at 30°C for 12 h.

Genotyping

Single colonies of deletion mutant strains were genotyped by PCR and Sanger sequencing. The phage sensitivity of the deletion mutant strains was then characterized via double-layer agar plate assays and adsorption assays, as described above.

Construction of Complementation Strains

Complementation strains were also generated to determine whether wild-type copies of the deleted genes could restore phage sensitivity to the deletion mutants. tonB, fhuA, fepA, ompF, waaG, tsx, ompA, and fadL were separately amplified using the CPEC technique and cloned into pET-28a to generate complementation plasmids. The complementation plasmids, designated pET-28a-xxx, were then transformed into their corresponding deletion mutations by electroporation to obtain complemented strains. The phage sensitivity of the complementation strains was confirmed by double-layer agar plate assays and adsorption assays, as described above.

Screening of Polyvalent Phage-Resistant Strains

Eight phages isolated in this study that infect E. coli BL21 (DE3) via different receptors were mixed to produce a phage cocktail. BL21 (DE3) mutant strains were then screened against the phage cocktail using the methods described above. Spotting assays and double-layer agar plate assays were used to identify the susceptibilities of the phage-resistant strains to the phage cocktail and to each of the phages individually. A polyvalent phage-resistant strain showing resistance to all the phages in the cocktail was selected for further analysis and was designated strain PR8.

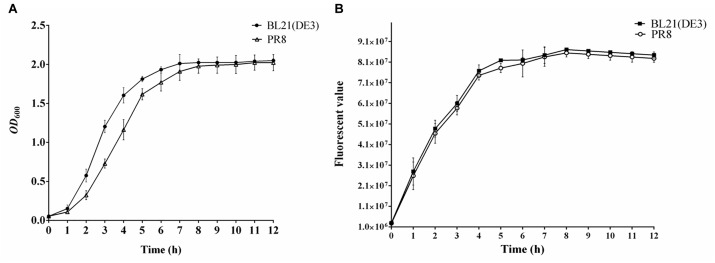

Analysis of the Polyvalent Phage-Resistant Strain

A total of 32 phages isolated from China that can infect E. coli BL21 (DE3) were collected in our laboratory. The phage sensitivity of strain PR8 was evaluated by a double-layer agar plate method. Bacterial growth curves were generated for the BL21 (DE3) and PR8 strains to identify any differences in bacterial counts between the two strains during propagation. Briefly, overnight cultures were used to inoculate fresh LB medium at a ratio of 1:100 (v/v). The cultures were then incubated at 37°C, 220 rpm for 12 h. Three replicate samples (1 mL each) were collected every hour to determine the OD600 of the cultures. Three replicates were conducted for determination.

In addition, to identify differences in protein expression between polyvalent phage-resistant strain PR8 and wild-type strain BL21 (DE3), enhanced green fluorescent protein EGFP was selected as an indicator protein. Briefly, egfp was cloned into pET-28a, generating recombinant plasmid pET-28a-egfp, which was then transformed into PR8 and BL21 (DE3) electrocompetent cells, respectively. Recombinant strains containing pET-28a-egfp were separately cultured overnight and then used to inoculate fresh LB medium at a ratio of 1:100 (v/v). Cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking to OD600 = 0.6 before the addition of isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.8 mM to induce the expression of EGFP. Three parallel 200 μL samples were taken in 96-well plates every hour and the fluorescence values were determined using a Multi-Mode Microplate Detection Platform SpectraMax® i3 (excitation 485 nm, emission 535 nm). A strain that did not carry the expression vector was used as the control. Three replicates were conducted for determination. Fluorescence value = experimental group fluorescence value - control group fluorescence value.

Results

Phage Morphology

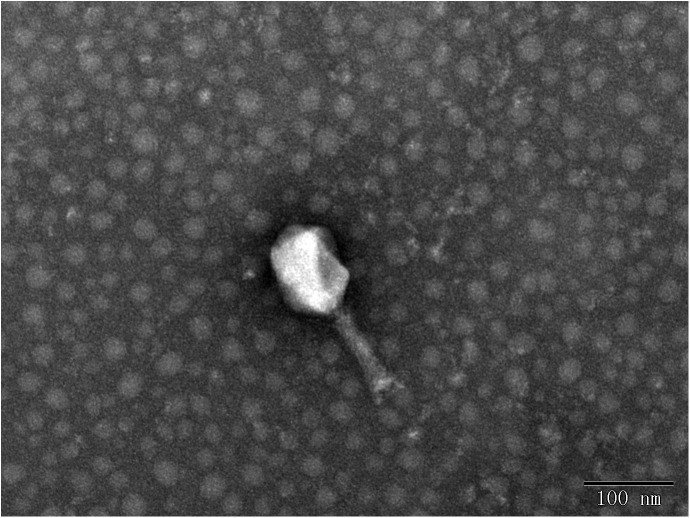

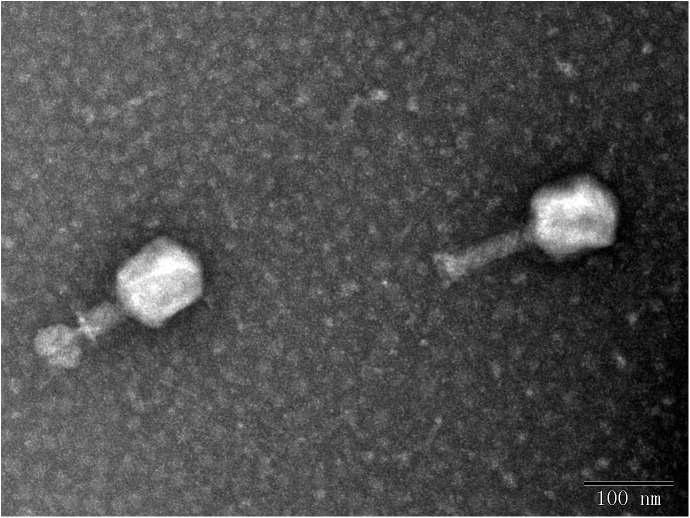

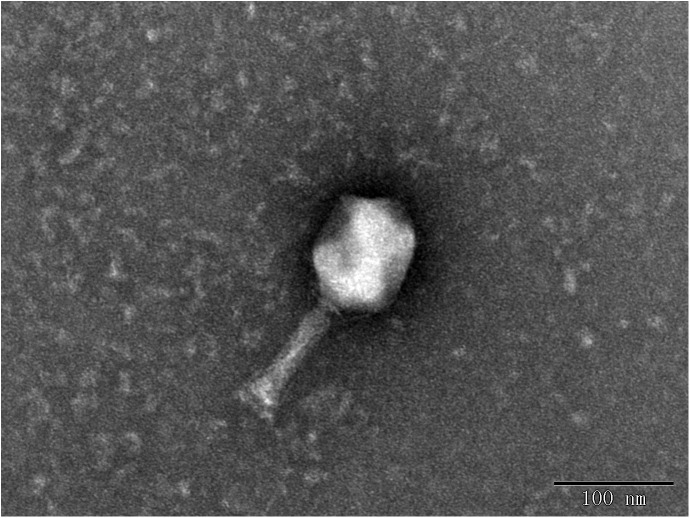

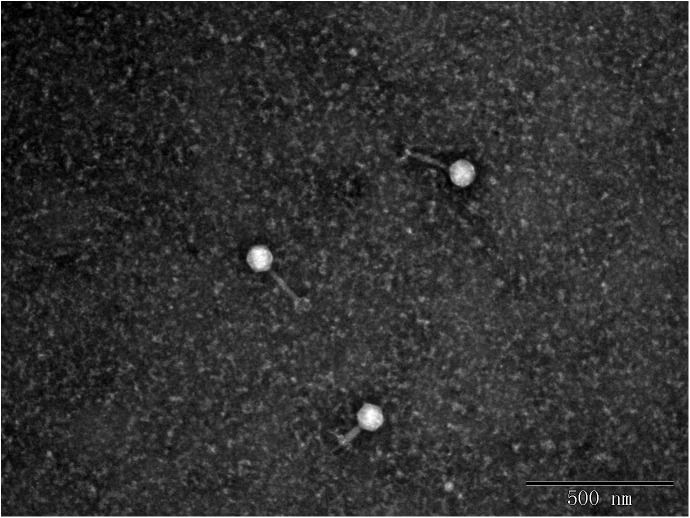

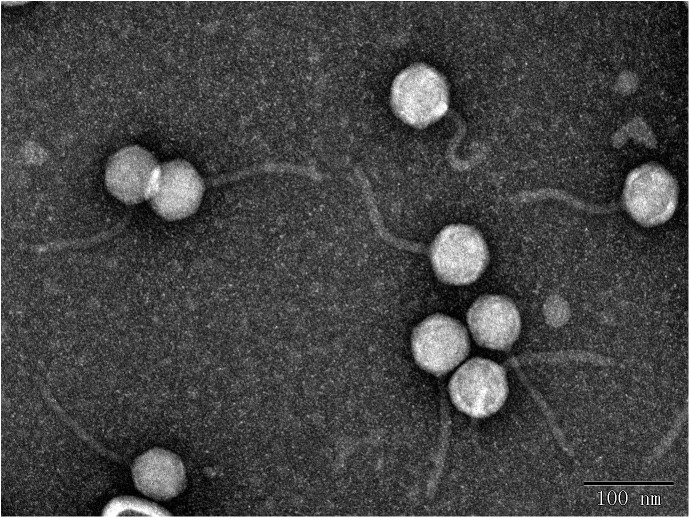

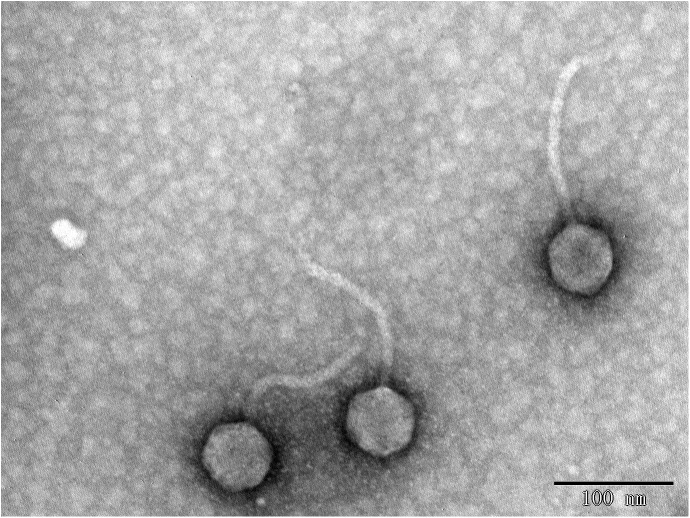

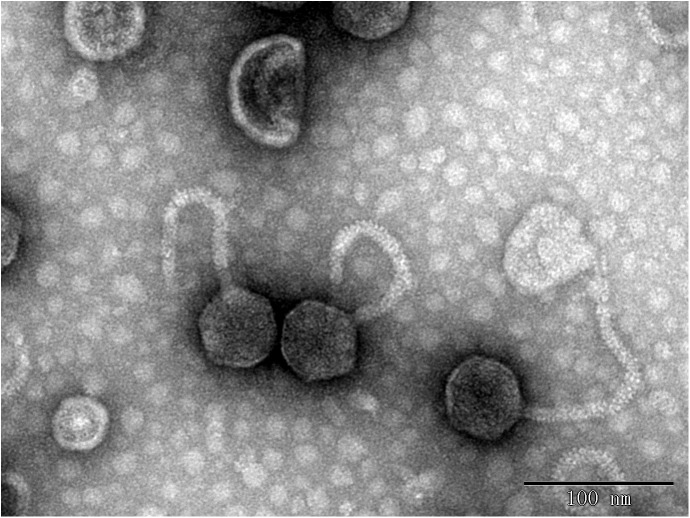

In this study, eight phages were sequentially separated from sewage (Table 2). Phages vB_EcoS_IME18 (IME18), vB_EcoS_IME253 (IME253), vB_EcoM_IME281 (IME281), vB_EcoM_IME338 (IME338), vB_EcoM_IME339 (IME339), vB_EcoM_IME340 (IME340), vB_EcoM_IME341 (IME341), and vB_EcoS_IME347 (IME347) formed clear, bright plaques on soft agar plates (Supplementary Figure S2). TEM imaging showed that phages IME281 (Figure 1), IME339 (Figure 2), IME340 (Figure 3), and IME341 (Figure 4) had a prolate head and a tail with a contractile sheath. The elongated icosahedral head was ∼100 nm long and 80 nm wide, while the tail tube was ∼100 nm long. Phage IME338 (Figure 5) had an icosahedral head approximately 60 nm wide and a tail with a contractile sheath approximately 100 nm long. Phages IME18 (Figure 6), IME253 (Figure 7) and IME347 (Figure 8) had an icosahedral head and a non-contractile tail, with a head diameter of approximately 60 nm and a tail length of approximately 160 nm.

Table 2.

Phages isolated in this study.

| Phage | Genomes size (bp) | Species | Microscopy | MOI | Burst size (PFU/cell) | Receptor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vB_EcoS_IME18 | 50,354 | T1virus | Siphoviridae | 0.01 | 223 | FhuA |

| vB_EcoS_IME253 | 46,717 | Rtpvirus | Siphoviridae | 0.01 | 186 | FepA |

| vB_EcoM_IME281 | 170,531 | Js98virus | Myoviridae | 0.001 | 153 | OmpF |

| vB_EcoM_IME338 | 85,675 | Felix01virus | Siphoviridae | 0.001 | 81 | LPS |

| vB_EcoM_IME339 | 164,366 | T4virus | Myoviridae | 0.001 | 91 | Tsx |

| vB_EcoM_IME340 | 165,549 | T4virus | Myoviridae | 0.001 | 95 | OmpA |

| vB_EcoM_IME341 | 172,379 | Js98virus | Myoviridae | 0.001 | 246 | FadL |

| vB_EcoS_IME347 | 50,048 | T1virus | Siphoviridae | 0.01 | 145 | YncD |

FIGURE 1.

Transmission electron micrograph images of Escherichia coli phage vB_EcoM_IME281.

FIGURE 2.

Transmission electron micrograph images of Escherichia coli phage vB_EcoM_IME339.

FIGURE 3.

Transmission electron micrograph images of Escherichia coli phage vB_EcoM_IME340.

FIGURE 4.

Transmission electron micrograph images of Escherichia coli phage vB_EcoM_IME341.

FIGURE 5.

Transmission electron micrograph images of Escherichia coli phage vB_EcoM_IME338.

FIGURE 6.

Transmission electron micrograph images of Escherichia coli phage vB_EcoS_IME18.

FIGURE 7.

Transmission electron micrograph images of Escherichia coli phage vB_EcoS_IME253.

FIGURE 8.

Transmission electron micrograph images of Escherichia coli phage vB_EcoS_IME347.

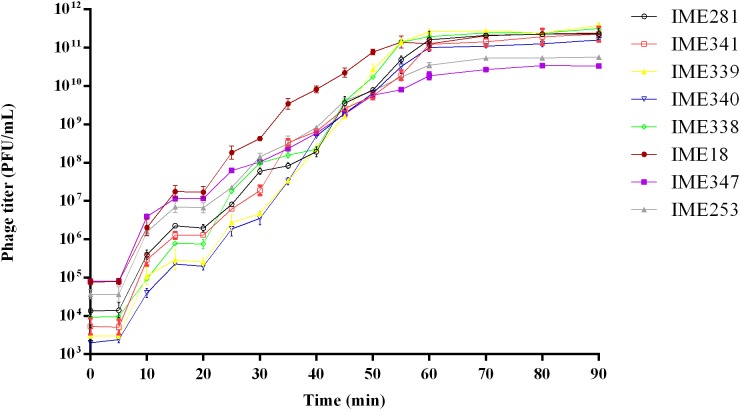

Optimal MOI and One-Step Growth Curves

Multiplicity of infection analysis assays showed that the optimal MOIs for phages IME18, IME253, IME281, IME338, IME339, IME340, IME341, and IME347 were 0.01, 0.01, 0.001, 0.001, 0.001, 0.001, 0.001, and 0.01, respectively. One-step growth curve analyses revealed that all of the phages had a latency period of about 5 min (Figure 9). The burst sizes of phages IME18, IME253, IME281, IME338, IME339, IME340, IME341, and IME347 were 223, 186, 153, 81, 91, 95, 246, 145 PFU/cell, respectively. The final titers of all phages exceeded 1010 PFU/mL, indicating that they are highly infectious toward E. coli BL21 (DE3).

FIGURE 9.

One-step growth curves of Escherichia coli phages vB_EcoS_IME18, vB_EcoS_IME253, vB_EcoM_IME281, vB_EcoM_IME338, vB_EcoM_IME339, vB_EcoM_IME340, vB_EcoM_IME341, and vB_EcoS_IME347.

Phage Genome Analysis

The genomes of phages IME18 (GenBank Accession No. MH051911), IME253 (GenBank Accession No. KX130960), IME281 (GenBank Accession No. MH051913), IME338 (GenBank Accession No. MH051914), IME339 (GenBank Accession No. MH051915), IME340 (GenBank Accession No. MH051916), IME341 (GenBank Accession No. MH051917), and IME347 (GenBank Accession No. MH051918) were 50,354, 46,717, 170,531, 85,675, 164,366, 165,549, 172,379, and 50,048 bp in size, respectively, with GC contents of 45.6, 44.2, 39.4, 38.7, 35.6, 35.5, 39.5, and 49.7%, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis based on the amino acid sequence of the large subunit of the terminase from each phage showed that IME281 and IME341 were most closely related to Js98virus, Tevenvirinae, Myoviridae; IME339 and IME340 were most closely related to T4virus, Tevenvirinae, Myoviridae; IME338 was most similar to Felix01virus, Ounavirinae, Myoviridae; IME18 and IME347 were most closely related to T1virus, Tunavirinae, Siphoviridae, and IME253 was most closely related to Rtpvirus, Tunavirinae, Siphoviridae (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Phylogenetic tree based on the terminase large subunit protein amino acid sequences of Escherichia coli phages vB_EcoS_IME18, vB_EcoS_IME253, vB_EcoM_IME281, vB_EcoM_IME338, vB_EcoM_IME339, vB_EcoM_IME340, vB_EcoM_IME341, and vB_EcoS_IME347.

Analysis of Bacteriophage-Insensitive Mutants

Three E. coli mutants that were insensitive to each of the isolated phages were randomly selected for whole-genome sequencing. The mutations putatively responsible for phage resistance were then identified by whole genome comparison with the sequence of phage-sensitive strain BL21 (DE3). We searched for phage receptor-associated variations in the genomes of the BIMs, with all results listed in Supplementary Table S2. Analysis revealed that mutations within fhuA, fepA, ompF, waaG, tsx, ompA, fadL, and yncD were present in the strains showing resistance to phages IME18, IME253, IME281, IME338, IME339, IME340, IME341, and IME347, respectively. fhuA, fepA, ompF, tsx, ompA, fadL, and yncD all encode different bacterial outer membranes proteins, while waaG participates in the synthesis of LPS. These findings indicate that the identified genes play an important role in the infection of BL21 (DE3) by the corresponding bacteriophages.

Identification and Confirmation of Phage Receptor-Related Genes

YncD is a receptor protein of phage IME347 for BL21 (DE3; Li et al., 2018). To confirm whether fhuA, fepA, ompF, waaG, tsx, ompA, and fadL were phage receptor-related genes with a role in the observed phage resistance, we constructed deletion mutants of each of these genes using the Scarless Cas9 Assisted Recombineering system. FhuA is the receptor for bacteriophage T1, and the infection process requires the function of TonB (Hantke and Braun, 1978). To determine whether the infection of phages IME18, IME253, and IME347 is dependent on TonB, we also constructed a tonB deletion mutant strain. During gene editing, the bacterial genome is cleaved by the Cas9 protein under the guidance of the sgRNA, after which the homologous recombinase integrates the homologous arm-containing oligonucleotide into the cleaved genome. PCR and Sanger sequencing confirmed that all of the target genes were successfully knocked out in the current study.

Phage receptor gene deletion mutants showed phage-resistant phenotypes in double-layer plate assays. Deletion mutant ΔtonB was not infected by phages IME18 and IME253 but was infected by IME347, indicating that IME18 and IME253 phage infection is TonB-dependent, whereas phage IME347 phage infection is TonB-independent. Deletion mutants ΔfhuA, ΔfepA, ΔompF, ΔwaaG, Δtsx, ΔompA, ΔfadL, and ΔyncD were not infected by phages IME18, IME253, IME281, IME338, IME339, IME340, IME341, and IME347, respectively, but could be infected by other isolated phages. In addition, the phage adsorption capacity of the phage receptor gene deletion mutants was significantly reduced compared with that of phage-sensitive strain BL21 (DE3; Table 3). Ddouble-layer agar plate assays showed that complementation of the mutant strains with the wild-type gene restored sensitivity to phage infection in all cases, while adsorption assays revealed that complementation also restored the adsorption capacity of the phages (Table 3). Together, these results verified that the receptors for phages IME18, IME253, IME281, IME338, IME339, IME340, IME341, and IME347 are FhuA, FepA, OmpF, LPS, Tsx, OmpA, FadL, and YncD, respectively, and that the receptors are not shared.

Table 3.

The adsorption rate of phages.

| Phage | Receptor | BL21 (DE3; PFU/cell/ mL/min) | Deletion (PFU/cell/ mL/min) | Complementation (PFU/cell/ mL/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| vB_EcoS_IME18 | FhuA | 5.7047E–10 | 3.3557E–11 | 5.03356E–10 |

| vB_EcoS_IME253 | FepA | 4.69231E–10 | 3.84615E–11 | 4.30769E–10 |

| vB_EcoM_IME281 | OmpF | 8.69359E–10 | 7.60095E–11 | 8.50356E–10 |

| vB_EcoM_IME338 | WaaG | 4.61538E–10 | 8.02676E–11 | 4.14716E–10 |

| vB_EcoM_IME339 | Tsx | 9.13043E–10 | 1.08696E–11 | 8.58696E–10 |

| vB_EcoM_IME340 | OmpA | 1.05516E–09 | 5.27578E–11 | 1.03118E–09 |

| vB_EcoM_IME341 | FadL | 7.80105E–10 | 4.18848E–11 | 7.27749E–10 |

| vB_EcoS_IME347 | YncD | 3.97394E–10 | 3.25733E–11 | 3.71336E–10 |

Analysis of a Polyvalent Phage-Resistant Strain

Strain PR8 was obtained by screening using a cocktail of the above eight phages, twice. Whole genome sequencing of strain PR8 revealed that the strain also had mutations in genes fhuA, fepA, ompF, waaG, tsx, ompA, fadL, and yncD relative to E. coli BL21 (DE3; Supplementary Table S3). Double-layer agar plate assays showed that the selected polyvalent phage resistant-strain PR8 was resistant to 23 phages (Table 4). Of the 23 phages, eleven were identified as Myoviridae phages, seven were identified as Siphoviridae phages and five were identified as Ackermannviridae phages. The results of the BLAST analysis of phage whole genomes showed no identity between phages of different subfamilies and high identity between phages of the same genus (Supplementary Table S4). To confirm that strain PR8 was also capable of high-level recombinant protein expression, growth curve and EGFP protein expression analyses were conducted. The results showed that polyvalent phage-resistant strain PR8 had a slightly lower OD600 than the wild-type strain during the first 8 h of incubation, but that the cell density increased to wild-type levels at 8–12 h post-inoculation (Figure 11A). The strains PR8 and BL21 (DE3) grew to OD600 = 0.6 and expressed recombinant EGFP in the same conditions. Fluorescence analysis showed that there was only a small difference in fluorescence between the two strains over 8h of expression (Figure 11B).

Table 4.

Phages to which Escherichia coli PR8 was resistant.

| Phage | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| vB_EcoM_IME339 | Myoviridae, Tevenvirinae, T4virus | Beijing |

| vB_EcoM_IME340 | Myoviridae, Tevenvirinae, T4virus | Beijing |

| IME391 | Myoviridae, Tevenvirinae, T4virus | Qingdao |

| vB_EcoM_IME281 | Myoviridae, Tevenvirinae, Js98virus | Beijing |

| vB_EcoM_IME341 | Myoviridae, Tevenvirinae, Js98virus | Beijing |

| IME412 | Myoviridae, Tevenvirinae, Js98virus | Henan |

| IME361 | Myoviridae, Tevenvirinae, Rb69virus | Qingdao |

| IME362 | Myoviridae, Tevenvirinae, Rb69virus | Qingdao |

| vB_EcoM_IME338 | Myoviridae, Ounavirina, Felix01virus | Beijing |

| IME364 | Myoviridae, Ounavirina, Felix01virus | Wuhan |

| IME365 | Myoviridae, Ounavirina, Felix01virus | Wuhan |

| T1 | Siphoviridae, Tunavirinae, T1virus | – |

| vB_EcoS_IME18 | Siphoviridae, Tunavirinae, T1virus | Beijing |

| vB_EcoS_IME167 | Siphoviridae, Tunavirinae, T1virus | Beijing |

| vB_EcoS_IME347 | Siphoviridae, Tunavirinae, T1virus | Beijing |

| JMPW1 | Siphoviridae, Tunavirinae, T1virus (Shen et al., 2016) | – |

| vB_EcoS_IME253 | Siphoviridae, Tunavirinae, Rtpvirus | Beijing |

| SSL-2009a | Siphoviridae, HK578likevirus (Li et al., 2019) | – |

| IME360 | Ackermannviridae, Cvivirinae, Cba120virus | Wuhan |

| IME366 | Ackermannviridae, Cvivirinae, Cba120virus | Wuhan |

| IME371 | Ackermannviridae, Cvivirinae, Cba120virus | Wuhan |

| IME375 | Ackermannviridae, Cvivirinae, Cba120virus | Wuhan |

| IME377 | Ackermannviridae, Cvivirinae, Cba120virus | Wuhan |

FIGURE 11.

Evaluation of recombinant protein expression performance of Escherichia coli PR8. (A) Growth curve of E. coli BL21 (DE3) and PR8. (B) Fluorescence value of EGFP expressed by E. coli BL21 (DE3) and PR8.

Discussion

Two T4virus phages isolated in this study used OMPs as receptors to infect E. coli BL21 (DE3). The receptor for phage IME339 is Tsx, which serves as a substrate-specific channel for nucleosides and deoxynucleosides. Structures of Tsx with bound nucleosides show that there are at least three distinct binding sites in the channel (Nuc0, Nuc1, and Nuc2). Mutations Phe27Leu, Gly28Arg (Glu), Ser217Arg, Gly239Asp, and Gly240Asp result in a Tsx protein defective in nucleoside transport (Fsihi et al., 1993; Ye and van den Berg, 2004). The amino acid mutation sites of the phage IME339-resistant strain and PR8 were Leu149Glu, Phe18fs, Met1_Ter295del, and Trp171Ter (where “fs” indicates a frame shift). Residual Leu149 is extracellular, close to loop 4. Mutation Leu149Glu affected the infection of phage IME339. In addition, residues 198–207 of E. coli K12 Tsx might be part of the Tsx-specific phage (T6, T6h3.1,Ox1, H1, H3, H8, H9, K18) receptor region, and substitutions Asn249Lys and Asn254Lys (Tyr) strongly impaired the phage T6 receptor function of Tsx (Krieger-Brauer and Braun, 1980; Schneider et al., 1993; Nieweg and Bremer, 1997). The receptor for phage IME340 is OmpA, which is one of the major OMPs in E. coli, with 100,000 copies typically found per cell (Koebnik et al., 2000; Ortiz-Suarez et al., 2016). OmpA has multiple functions. For example, OmpA can act as a receptor for colicin K and colicin L, a pore protein that allows slow penetration of small solutes, the adhesin/invasin to produce pathogenicity, involved in biofilm formation, and participates in innate immunity system (Smith et al., 2010). In E. coli K-12, OmpA serves as a receptor for many T-even-like phages, with four mutational alterations (residue 25 in loop 1, residue 70 in loop 2, residue 110 in loop 3, and residue 154 in loop 4) found to affect the ability of OmpA to function as a phage receptor (Morona and Henning, 1984; Morona et al., 1984; Nieweg and Bremer, 1997). OmpA can also act as a host-specific factor in Shigella species that mediates phage Sf6 (P22virus subfamily, Podoviridae family) binding, with loops 2 and 4 being the most critical (Parent et al., 2014; Porcek and Parent, 2015). In this study, the amino acid mutations in OmpA in phage IME340-resistant strain and PR8 were Val122fs, Gln38Ter, Met1_Ter347del, and Lys33Ter. The site of phage IME340 is located between residues 122 and 347.

Two Js98virus phages isolated in this study also used OMPs as receptors to infect E. coli BL21 (DE3). The receptor for phage IME281 is the osmotically regulated cation-selective OmpF protein, which consists of three monomeric channels (Cowan et al., 1992). OmpF can be used as a receptor for colicin N, a causative agent and an antibiotic channel. OmpF is a receptor protein for phage K20, and substitution of residues exposed on the surfaces of loops 5, 6, or 7 prevents the binding of K20 without affecting the channel activity of OmpF (Silverman and Benson, 1987; Traurig and Misra, 2010). In addition, infection by Yersinia phages TG1 (Tg1virus genus, Myoviridae family) and ΦR1-RT (Tg1virus genus, Myoviridae family) is dependent on temperature-regulated expression of OmpF (Leonvelarde et al., 2016). The amino acid mutation sites in OmpF of the phage IME281-resistant strain and PR8 were Tyr79_Val128del, Asp76fs, Met1_Ter363del, and Thr77_Tyr128del. Tyr79_Val128del results in a deletion of loop 3 demonstrating that loop 3 has phage receptor function. The receptor protein for phage IME341 was identified as a monomer of FadL, which is required for the transport of long-chain fatty acids through the outer membrane and also participates in the uptake of hydrophobic compounds, including aromatic hydrocarbons, for biodegradation (van den Berg et al., 2004). Residues Phe448, Pro428, Val410, and Ser397 are required for optimal levels of long-chain fatty acid transport and that amino acid residues Pro428 and Val410 are essential for long-chain fatty acid binding (Kumar and Black, 1993). FadL also acts as a receptor protein for phage T2, and its exposed extracellular loop (residues 28–160.) is required for phage T2 binding (Cristalli et al., 2000). The mutations of FadL in the phage IME341-resistant strain and PR8 were Asp34Ter, Leu161Val, Leu394Glu, and Met1_Ter447del. Residues Leu161 and Leu394 in FadL are extracellular. Mutations Leu161Val and Leu394Glu seriously affected the infection of phage IME341.

Infection of E. coli BL21 (DE3) by phages IME18 and IME253 was TonB-dependent, with FhuA and FepA used as receptors, respectively. The FhuA amino acid mutation sites of the phage IME18-resistant strain and PR8 were Ser675_Trp704del, Thr629fs, Phe519fs, and Met416_Arg417del. Residues Ser675_Trp704 and Met416_Arg417 are related to receptor function of phage IME18. In the phage IME253-resistant strain and PR8, fepA was deleted. FhuA and FepA belong to the family of TonB-dependent receptors. FhuA is mainly involved in the binding and absorption of ferrichrome and colicin M, and is a receptor for Siphoviridae bacteriophages T1, T5, phi80, and UC-1 (Killmann et al., 1995; Endriss and Braun, 2004). FepA is mainly involved in the transport of ferric enterobactin and is a receptor for T5-like phage H8 (Rabsch et al., 2007). Introduction of a foreign peptide after FepA residues 55, 142, or 324 can severely impair receptor function for ferric enterobactin, colicin D and colicin B. However, the introduction of a foreign peptide after residues 204 or 635 only restricts FepA’s function for colicin B and colicin D (Armstrong et al., 1990). In addition, TonB-dependent receptor BtuB, which is required for the binding and transport of vitamin B12, is a receptor for T5-like phages EPS7 and SPC35 (Hong et al., 2008; Kim and Ryu, 2011).

Lipopolysaccharides is an important component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and consists of three parts: lipid A, core oligosaccharide, and O-antigen. The complete LPS structure is called smooth (S) type LPS, while LPS lacking the O-antigen is referred to as rough (R) type. Lipid A is located on the innermost side of LPS and is usually conserved, while the polysaccharide polymer composed of O-antigen, the structural composition of which is highly variable, can extend to the outside of the cell membrane. Generally, the host range of phages capable of cleaving S-type strains is broader than that of phages targeting R-type cells (Rakhuba et al., 2010). waaG is involved in the synthesis of LPS in E. coli, and encodes a glycosyltransferase responsible for transferring and linking the primary glucose residue of the outer core of the LPS core oligosaccharide to the inner core of the LPS (Heinrichs et al., 2010). Deletion of this gene results in the loss of the O-antigen and the outer core of the core oligosaccharide of LPS. Felix01 phage has been reported to use LPS as a receptor, and here we demonstrate that Felix01virus phage IME338 also uses LPS as a receptor (Hudson et al., 1978).

In this study, we identified two T4virus phages (IME339 and IME340), two Js98virus phages (IME281 and IME341), one Felix01virus phage (IME338), two T1virus phages (IME18 and IME347), and one Rtpvirus phage (IME253), all of which used different receptors for infection of E. coli BL21 (DE3). We confirmed that the receptors for phages IME18, IME253, IME281, IME338, IME339, IME340, IME341, and IME347 are FhuA, FepA, OmpF, LPS, Tsx, OmpA, FadL, and YncD, respectively, and that none of the receptors are shared. We then identified a polyvalent phage-resistant BL21 (DE3) mutant strain, designated PR8, using a screening assay based on a phage cocktail consisting of the eight identified phages; PR8 is resistant to 23 tested phages. Strain PR8 not only resists infection by multiple phages but also has the ability to express high levels of recombinant protein, indicating that it is likely to be a valuable strain for production of recombinant protein. However, the mechanisms of interactions between phages and their hosts are not fully understood, and further research is needed to provide a theoretical basis for phage contamination control. Replacement of all UAG termination codons in E. coli with UAA enhances host resistance to T7 phage (Lajoie et al., 2013). Therefore, even greater codon changes may allow a host to completely avoid phage infection (Ostrov et al., 2016). In the near future, it will be possible to produce synthetic cells that are protected from phage infection. The results of the current study provide important information for such endeavors.

Author Contributions

YT, JW, and PL conceived and designed the experiments. PL carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript. All authors analyzed the data, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the high-throughput sequencing and technical support provided by the State Key Laboratory of Pathogen Biosecurity of the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology. We thank Tamsin Sheen, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Editing China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Funding. The study was supported by the Ministry of Education, the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. AWS16J020), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81572045 and 31870166), and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (Grant No. 2017GNC13108).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00850/full#supplementary-material

References

- Armstrong S. K., Francis C. L., Mcintosh M. A. (1990). Molecular analysis of the Escherichia coli ferric enterobactin receptor FepA. J. Biol. Chem. 265 14536–14543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H. W., Cho Y. H. (2013). Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Podophage MPK7, which requires Type IV Pili for Infection. Genome Announc. 1:e00744-13. 10.1128/genomeA.00744-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertozzi Silva J., Storms Z., Sauvageau D. (2016). Host receptors for bacteriophage adsorption. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 363:fnw002. 10.1093/femsle/fnw002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyke B., Julia G., Manfred R., Max S. (2011). Sequencing and characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage JG004. BMC Microbiol. 11:102. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brussow H., Hendrix R. W. (2002). Phage genomics: small is beautiful. Cell 108 13–16. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00637-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Sun E., Song J., Yang L., Wu B. (2018). Complete genome sequence of a novel T7-Like Bacteriophage from a Pasteurella multocida capsular type A isolate. Curr. Microbiol. 75 574–579. 10.1007/s00284-017-1419-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y., Shin H., Lee J.-H., Ryu S. (2012). Identification and characterization of a novel flagellum-dependent Salmonella-infecting bacteriophage, iEPS5. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 4829–4837. 10.1128/AEM.00706-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan S. W., Schirmer T., Rummel G., Steiert M., Ghosh R., Pauptit R. A., et al. (1992). Crystal structures explain functional properties of two E. coli porins. Nature 358 727–733. 10.1038/358727a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristalli G., Dirusso C. C., Black P. N. (2000). The amino-terminal region of the long-chain fatty acid transport protein FadL contains an externally exposed domain required for bacteriophage T2 binding. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 377 324–333. 10.1006/abbi.2000.1794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di D. M., White J., Schnaitman C., Bradbeer C. (1973). Transport of vitamin B12 in Escherichia coli: common receptor sites for vitamin B12 and the E colicins on the outer membrane of the cell envelope. J. Bacteriol. 115 506–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endriss F., Braun V. (2004). Loop deletions indicate regions important for FhuA transport and receptor functions in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186 4818–4823. 10.1128/JB.186.14.4818-4823.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fsihi H., Kottwitz B., Bremer E. (1993). Single amino acid substitutions affecting the substrate specificity of the Escherichia coli K-12 nucleoside-specific Tsx channel. J. Biol. Chem. 268 17495–17503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantke K., Braun V. (1978). Functional interaction of the tonA/tonB receptor system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 135 190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemolhosseini S., Holmes Z., Mutschler B., Henning U. (1994). Alterations of receptor specificities of coliphages of the T2 family. J. Mol. Biol. 240 105–110. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs D. E., Yethon J. A., Whitfield C. (2010). Molecular basis for structural diversity in the core regions of the lipopolysaccharides of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 30 221–232. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01063.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo Y. J., Chung I. Y., Choi K. B., Lau G. W., Cho Y. H. (2007). Genome sequence comparison and superinfection between two related Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages, D3112 and MP22. Microbiology 153 2885–2895. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007260-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho T. D., Slauch J. M. (2001). OmpC is the receptor for Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-2 bacteriophages of Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 183 1495–1498. 10.1128/JB.183.4.1495-1498.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J., Kim K. P., Heu S., Lee S. J., Adhya S., Ryu S. (2008). Identification of host receptor and receptor-binding module of a newly sequenced T5-like phage EPS7. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 289 202–209. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01397.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson H. P., Lindberg A. A., Stocker B. A. (1978). Lipopolysaccharide core defects in Salmonella typhimurium mutants which are resistant to Felix O phage but retain smooth character. J. Gen. Microbiol. 109 97–112. 10.1099/00221287-109-1-97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman P., Abedon S. T. (2010). Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 70 217–248. 10.1016/S0065-2164(10)70007-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun J. W., Kim H. J., Yun S. K., Chai J. Y., Lee B. C., Park S. C. (2016). Isolation and comparative genomic analysis of T1-Like Shigella bacteriophage pSf-2. Curr. Microbiol. 72 235–241. 10.1007/s00284-015-0935-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killmann H., Videnov G., Jung G., Schwarz H., Braun V. (1995). Identification of receptor binding sites by competitive peptide mapping: phages T1, T5, and phi 80 and colicin M bind to the gating loop of FhuA. J. Bacteriol. 177 694–698. 10.1128/jb.177.3.694-698.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Ryu S. (2011). Characterization of a T5-like coliphage, SPC35, and differential development of resistance to SPC35 in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77 2042–2050. 10.1128/AEM.02504-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebnik R., Locher K. P., Van Gelder P. (2000). Structure and function of bacterial outer membrane proteins: barrels in a nutshell. Mol. Microbiol. 37 239–253. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01983.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger-Brauer H. J., Braun V. (1980). Functions related to the receptor protein specified by the tsx gene of Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 124 233–242. 10.1007/BF00427732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G. B., Black P. N. (1993). Bacterial long-chain fatty acid transport. Identification of amino acid residues within the outer membrane protein FadL required for activity. J. Biol. Chem. 268 15469–15476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie S. J., Samson J. E., Moineau S. (2010). Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8 317–327. 10.1038/nrmicro2315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie M. J., Rovner A. J., Goodman D. B., Aerni H. R., Haimovich A. D., Kuznetsov G., et al. (2013). Genomically recoded organisms expand biological functions. Science 342 357–360. 10.1126/science.1241459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonvelarde C. G., Happonen L., Pajunen M., Leskinen K., Kropinski A. M., Mattinen L., et al. (2016). Yersinia enterocolitica specific infection by bacteriophages TG1 and ΦR1-RT is dependent on temperature regulated expression of the phage host receptor OmpF. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82 5340–5353. 10.1128/AEM.01594-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Lin H., Mi Z., Tong Y., Wang J. (2018). vB_EcoS_IME347 a novel T1-like Escherichia coli bacteriophage. J. Basic Microbiol. 58 968–976. 10.1002/jobm.201800271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Lu S., Huang H., Tan L., Ni Q., Shang W., et al. (2019). Comparative analysis and characterization of Enterobacteria phage SSL-2009a and ’HK578likevirus’ bacteriophages. Virus Res. 259 77–84. 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony J., van Sinderen D. (2015). Novel strategies to prevent or exploit phages in fermentations, insights from phage-host interactions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 32 8–13. 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco M. B., Moineau S., Quiberoni A. (2012). Bacteriophages and dairy fermentations. Bacteriophage 2 149–158. 10.4161/bact.21868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon J. G., Peters D. L., Dennis J. J. (2018). Identification and characterization of type IV Pili as the cellular receptor of broad host range Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteriophages DLP1 and DLP2. Viruses 10:338. 10.3390/v10060338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morona R., Henning U. (1984). Host range mutants of bacteriophage Ox2 can use two different outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli K-12 as receptors. J. Bacteriol. 159 579–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morona R., Klose M., Henning U. (1984). Escherichia coli K-12 outer membrane protein (OmpA) as a bacteriophage receptor: analysis of mutant genes expressing altered proteins. J. Bacteriol. 159 570–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieweg A., Bremer E. (1997). The nucleoside-specific Tsx channel from the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter aerogenes: functional characterization and DNA sequence analysis of the tsx genes. Microbiology 143 (Pt 2), 603–615. 10.1099/00221287-143-2-603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata S. (1980). Bacteriophage contamination in industrial processes. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 22 177–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Suarez M. L., Samsudin F., Piggot T. J., Bond P. J., Khalid S. (2016). Full-length OmpA: structure, function, and membrane interactions predicted by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 111 1692–1702. 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov N., Landon M., Guell M., Kuznetsov G., Teramoto J., Cervantes N., et al. (2016). Design, synthesis, and testing toward a 57-codon genome. Science 353 819–822. 10.1126/science.aaf3639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez-Espino D., Eloe-Fadrosh E. A., Pavlopoulos G. A., Thomas A. D., Huntemann M., Mikhailova N., et al. (2016). Uncovering earth’s virome. Nature 536 425–430. 10.1038/nature19094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent K. N., Erb M. L., Cardone G., Nguyen K., Gilcrease E. B., Porcek N. B., et al. (2014). OmpA and OmpC are critical host factors for bacteriophage Sf6 entry in Shigella. Mol. Microbiol. 92 47–60. 10.1111/mmi.12536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard D., Toribio A., Petty N., van A. T., Yu L., Goulding D., et al. (2010). A conserved acetyl esterase domain targets diverse bacteriophages to the Vi capsular receptor of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 192 5746–5754. 10.1128/JB.00659-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcek N. B., Parent K. N. (2015). Key residues of S. flexneri OmpA mediate infection by bacteriophage Sf6. J. Mol. Biol. 427 1964–1976. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prehm P., Jann B., Jann K., Schmidt G., Stirm S. (1976). On a bacteriophage T3 and T4 receptor region within the cell wall lipopolysaccharide of Escherichia coli B. J. Mol. Biol. 101 277–281. 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90377-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan J., Tian J. (2009). Circular polymerase extension cloning of complex gene libraries and pathways. Plos One 4:e0006441. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabsch W., Ma L., Wiley G., Najar F. Z., Kaserer W., Schuerch D. W., et al. (2007). FepA- and TonB-dependent bacteriophage H8: receptor binding and genomic sequence. J. Bacteriol. 189 5658–5674. 10.1128/JB.00437-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhuba D. V., Kolomiets E. I., Dey E. S., Novik G. I. (2010). Bacteriophage receptors, mechanisms of phage adsorption and penetration into host cell. Pol. J. Microbiol. 59 145–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisch C. R., Prather K. L. J. (2015). The no-SCAR (Scarless Cas9 Assisted Recombineering) system for genome editing in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 5:15096. 10.1038/srep15096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisch C. R., Prather K. L. J. (2017). Scarless Cas9 assisted recombineering (no-SCAR) in Escherichia coli, an easy-to-use system for genome editing. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 117:31.8.1-31.8.20. 10.1002/cpmb.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmond G. P., Fineran P. C. (2015). A century of the phage: past, present and future. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13 777–786. 10.1038/nrmicro3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson J. E., Moineau S. (2013). Bacteriophages in food fermentations: new frontiers in a continuous arms race. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 4 347–368. 10.1146/annurev-food-030212-182541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H., Fsihi H., Kottwitz B., Mygind B., Bremer E. (1993). Identification of a segment of the Escherichia coli Tsx protein that functions as a bacteriophage receptor area. J. Bacteriol. 175 2809–2817. 10.1128/jb.175.10.2809-2817.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen M., Zhu H., Lu S., Le S., Li G., Tan Y., et al. (2016). Complete Genome Sequences of T1-Like Phages JMPW1 and JMPW2. Genome Announc. 4:e00601-16. 10.1128/genomeA.00601-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H., Lee J. H., Kim H., Choi Y., Heu S., Ryu S. (2012). Receptor diversity and host interaction of bacteriophages infecting Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. PLoS One 7:e0043392. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. A., Benson S. A. (1987). Bacteriophage K20 requires both the OmpF porin and lipopolysaccharide for receptor function. J. Bacteriol. 169 4830–4833. 10.1128/jb.169.10.4830-4833.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. G., Mahon V., Lambert M. A., Fagan R. P. (2010). A molecular Swiss army knife: OmpA structure, function and expression. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 273 1–11. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturino J. M., Klaenhammer T. R. (2006). Engineered bacteriophage-defence systems in bioprocessing. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4 395–404. 10.1038/nrmicro1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traurig M., Misra R. (2010). Identification of bacteriophage K20 binding regions of OmpF and lipopolysaccharide in Escherichia coli K-12. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 181 101–108. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08831.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg B., Black P. N., Clemons W. M., Jr., Rapoport T. A. (2004). Crystal structure of the long-chain fatty acid transporter FadL. Science 304 1506–1509. 10.1126/science.1097524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef C., Graaff P. J. D., Lugtenberg E. J. J. (1977). Mapping of a gene for a major outer membrane protein of Escherichia coli K12 with the aid of a newly isolated bacteriophage. Mol. Gen. Genet. 150 103–105. 10.1007/BF02425330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang W., Lv Y., Zheng W., Mi Z., Pei G., et al. (2014). Characterization and complete genome sequence analysis of novel bacteriophage IME-EFm1 infecting Enterococcus faecium. J. Gen. Virol. 95 2565–2575. 10.1099/vir.0.067553-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., van den Berg B. (2004). Crystal structure of the bacterial nucleoside transporter Tsx. EMBO J. 23 3187–3195. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Xing S., Sun Q., Pei G., Cheng S., Liu Y., et al. (2017). Characterization and complete genome sequence analysis of a novel virulent Siphoviridae phage against Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis in Xinjiang, China. Virus Genes. 53 464–476. 10.1007/s11262-017-1445-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.