Watch the interview with the authors

Watch the video presentation of this article

Abbreviations.

C max, peak plasma concentration; CYP, cytochrome P450; DAA, direct‐acting antiviral; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

The treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 infection has been revolutionized by the introduction of direct‐acting antiviral (DAA) agents (boceprevir and telaprevir) in combination with peginterferon and ribavirin. Although improved antiviral efficacy and shorter durations of therapy are anticipated, there are also potentially severe drug‐drug interactions involving protease inhibitors and other commonly used agents, and both practitioners and patients must familiarize themselves with these interactions before they use these agents.

Drug Metabolism

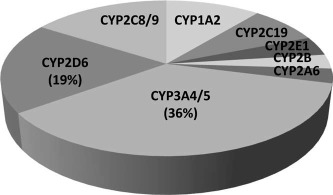

The cytochrome P450s (CYPs) are a superfamily of genes composed of several isoenzymes expressed in the endoplasmic reticulum of the liver and other organs that are integrally involved in the oxidative metabolism (i.e., phase 1) of numerous drugs (Fig. 1). In particular, the CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 isoenzymes are involved in the metabolism of up to 40% of all marketed drugs.1, 2 In addition, the enzyme activity of CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 in the small intestine can also influence the bioavailability of some drugs. Multiple studies have demonstrated substantial interindividual variations (i.e., 4‐ to 10‐fold) in the hepatic expression of CYP3A4; this can be explained in part by genetic polymorphisms, diet, and other environmental cofactors.3 The P‐glycoprotein transporter system, which is encoded by the multidrug resistance protein 2 gene and is localized in the plasma membranes of hepatocytes and enterocytes, is also involved in the elimination of various drugs and/or metabolites (i.e., phase 3). This enzyme family plays a key role in the elimination of many commonly used drugs and has also been shown to be both inducible and inhibitable like CYP3A with complex gene regulation.4

Figure 1.

Proportions of commonly used drugs metabolized by CYP isoenzymes in the human liver.

Drugs and herbal agents such as rifampin, efavirenz, and St. John's wort are known to induce the expression of CYP3A4 activity via the activation of nuclear receptors in the liver and lead to clinically significant reductions in the blood levels of cyclosporine and other CYP3A4 substrates with potentially deleterious clinical effects (Table 1).5, 6 Conversely, other commonly used medications such as alpha‐1‐adrenoreceptor antagonists and statins can competitively inhibit CYP3A4 activity.7 When competitive inhibitors and substrates of CYP3A4 are coadministered, the drug levels of one or both agents may significantly increase, and this can lead to clinically significant drug‐drug interactions and associated adverse events.

Table 1.

Drugs Absolutely Contraindicated With the Prescription of Telaprevir or Boceprevir Because of Potentially Serious Adverse Events

| Drug Class | Examples | Potentially Serious or Life‐Threatening Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|

| CYP3A substrates/inhibitors | ||

| Alpha‐1‐adrenoreceptor antagonists | Alfuzosin | Hypotension, dizziness |

| Ergot derivatives | Dihydroergotamine Ergonovine Ergotamine Methylergonovine | Peripheral vasospasm or ischemia |

| Gastrointestinal motility agents | Cisapride | Cardiac arrhythmia, QT prolongation |

| 3‐Hydroxy‐3‐methyl‐ glutaryl‐coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) | Atorvastatin* Lovastatin Simvastatin | Myopathy, rhabdomyolysis |

| Neuroleptics | Pimozide | Cardiac arrhythmia |

| Oral contraceptives† | Drospirenone | Hyperkalemia |

| Phosphodiesterase type 5 enzyme inhibitors† | Sildenafil Tadalafil | Visual abnormalities, hypotension, prolonged erection, syncope |

| Sedatives | Midazolam Triazolam | Prolonged sedation, respiratory depression |

| CYP3A inducers | ||

| Anticonvulsants† | Carbamazepine Phenobarbital Phenytoin | Reduced DAA levels with potentially reduced antiviral efficacy and increased drug resistance |

| Antimycobacterials | Rifampin | |

| Herbal products | St. John's wort | |

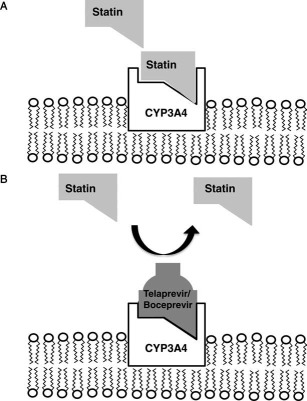

Both telaprevir and boceprevir are extensively metabolized in the liver and are potent CYP3A4 substrates and inhibitors. Telaprevir is also a P‐glycoprotein substrate and inhibitor, whereas boceprevir is partially metabolized by hepatic aldo‐keto reductase. Therefore, the coadministration of either of these agents with other drugs metabolized by CYP3A4 may lead to increased pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of the other drugs via the competitive inhibition of their metabolism (Fig. 2). For example, the peak plasma concentration (C max) for atorvastatin was 10‐fold higher when it was coadministered with telaprevir in healthy volunteers.8 In addition, C max for amlodipine was 1.3‐fold higher when it was coadministered with telaprevir. On the basis of these results and other in vitro testing, the package inserts for both protease inhibitors provide lists of drugs that are absolutely contraindicated when a patient is receiving either agent because of the potential for serious or life‐threatening adverse events (Table 1).8, 9 In addition, other drugs that are less dependent on CYP3A for elimination (e.g., amlodipine) should also be administered with caution to subjects receiving telaprevir or boceprevir (Table 2). Although additional prospective studies are needed in HCV patients, boceprevir‐treated patients in clinical trials who received a drug metabolized by CYP3A did not have an overall increased risk of an adverse event, although anemia and dysgeusia were more frequent with selective concomitant medications.10

Figure 2.

Mechanism for the competitive inhibition of CYP3A enzyme activity. (A) Many commonly used drugs such as atorvastatin have a strong binding affinity for CYP3A4, which is located in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes. In the steady state, the drug is absorbed via the gastrointestinal tract, metabolized by CYP3A4 in the liver, and eliminated from the body. (B) When a drug with a similar or greater binding affinity to CYP3A4 (e.g., telaprevir or boceprevir) is coadministered with atorvastatin, it can displace atorvastatin from CYP3A4 and lead to greater local and systemic bioavailability of the parent compound. Increased bioavailability of the drug can lead to a greater pharmacodynamic effect (e.g., hypolipidemia) as well as an increased incidence or severity of adverse events (e.g., myopathy) because of reduced drug metabolism.

Table 2.

Selected Drugs That Should Be Used With Caution in Subjects Receiving Boceprevir or Telaprevir Because of Altered Metabolism

| Drug Class | Examples | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|

| CYP3A substrates | ||

| Antiarrhythmics | Amiodarone Digoxin Lidocaine Quinidine | Increased arrhythmia |

| Antidepressants | Escitalopram* | Decreased efficacy of antidepressant |

| Antidepressants | Desipramine Trazodone | Increased sedation, dry mouth |

| Azole antifungals | Itraconazole Ketoconazole Posaconazole | Increased vomiting, diarrhea, hypertension |

| Antigout agents | Colchicine | Increased diarrhea |

| Calcium channel blockers | Amlodipine Diltiazem Nifedipine Verapamil | Increased hypotension, bradycardia |

| Corticosteroids | Budesonide Fluticasone Methylprednisolone Prednisone | Increased hyperglycemia, osteoporosis, insomnia, acne |

| HIV protease inhibitors† | Atazanavir | Increased vomiting, diarrhea |

| HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors | Tenofovir | Increased nephrotoxicity |

| Hormonal contraceptives | Ethinyl estradiol | Decreased efficacy |

| Immunosuppressants | Cyclosporine Sirolimus Tacrolimus | Increased nephrotoxicity, hypertension, neurotoxicity |

| Inhaled beta‐agonists | Salmeterol | Increased tachycardia |

| Macrolide antibiotics | Clarithromycin Erythromycin Telithromycin | Increased diarrhea, QT prolongation |

| CYP3A inducers | ||

| HIV protease inhibitors† | Atazanavir Darunavir Fosamprenavir Lopinavir | Reduced DAA levels with potentially reduced antiviral efficacy and increased drug resistance |

| HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors | Efavirenz | |

| Narcotic analgesics | Methadone | |

| Sedatives | Zolpidem | |

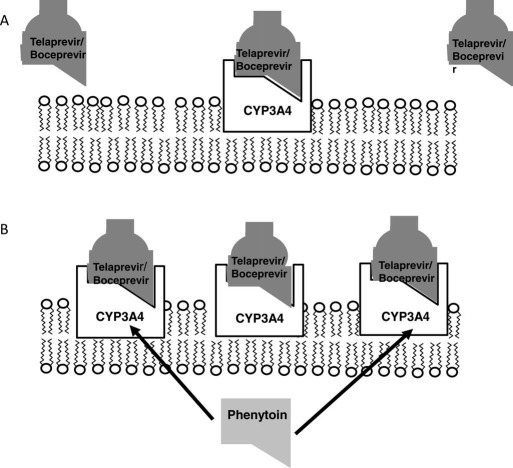

The serum levels of the DAAs themselves may also be affected when they are coadministered with certain drugs (Table 3). For example, the azole antifungal agents, which are strong binders of CYP3A, are expected to lead to potentially significant elevations in the serum levels of both boceprevir and telaprevir. As a result, telaprevir‐treated patients receiving one of these drugs may experience more frequent or severe rashes, myelotoxicity, or gastrointestinal symptoms. Similarly, boceprevir‐treated patients may have more frequent or severe anemia and/or dysgeusia when they are receiving one of these drugs. Therefore, practitioners must advise their patients to contact them if they develop an intercurrent illness that may require treatment and to report all concomitant medications. In addition, the treating physician may preferentially select an antibiotic, analgesic, or antidepressant that is less likely to lead to an interaction with the DAAs according to their known routes of elimination (Table 4). Similarly, subjects who receive a known CYP3A inducer such as rifampin or phenytoin may experience lower serum levels of DAAs and may have a greater risk of treatment failure and/or drug resistance (Fig. 3). Some studies have begun to explore the use of higher doses of telaprevir (i.e., 1125 mg by mouth three times a day) in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–coinfected patients receiving efavirenz, a CYP3A inducer, or the use of ritonavir boosting, but further studies are needed.11

Table 3.

Drugs That Can Alter Serum Boceprevir and Telaprevir Levels

| Drug Class | Examples | Impact on DAA Level | Potential Manifestation of Altered DAA Metabolism |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP3A substrates | |||

| Azole antifungals | Itraconazole Ketoconazole Posaconazole Voriconazole | Increase | Increased number of adverse events such as rash, myelotoxicity, and gastrointestinal side effects (telaprevir) or anemia and dysgeusia (boceprevir) |

| HIV protease inhibitors | Atazanavir Darunavir Fosamprenavir Lopinavir | Increase | |

| CYP3A inducers | |||

| Anticonvulsants | Carbamazepine Phenobarbital Phenytoin | Decrease | Decreased antiviral efficacy with potential increase in drug‐resistant variants |

| Antimycobacterials | Rifabutin | Decrease | |

| Corticosteroids | Dexamethasone | Decrease | |

| HIV reverse‐transcriptase inhibitors | Efavirenz | Decrease | |

| HIV protease inhibitors* | Atazanavir Darunavir Fosamprenavir Lopinavir | Decrease |

Table 4.

Alternative Agents to Consider for Patients Receiving Telaprevir or Boceprevir

| Antibiotics | Amoxicillin Cefazolin Clindamycin Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole Ciprofloxacin Levofloxacin Metronidazole Doxycycline |

| Analgesics | Acetaminophen Ibuprofen Tramadol Oxycodone |

| Antihypertensives | Metoprolol Hydrochlorothiazide Lisinopril Losartan Clonidine |

| Antidepressants | Bupropion Duloxetine |

| Antihistamines | Diphenhydramine Fexofenadine |

| Antidiabetic agents | Metformin Glipizide |

The major metabolism/elimination route of these agents is not CYP3A‐mediated. However, studies of prospective drug‐drug interactions with DAAs in healthy volunteers and/or HCV patients have not been completed.

Figure 3.

Mechanism of CYP3A4 induction and reduced bioavailability of telaprevir/boceprevir. (A) Telaprevir and boceprevir are metabolized in hepatocytes, which have a constitutive but inducible level of CYP3A4 enzyme activity. (B) The administration of select drugs such as phenytoin and efavirenz can lead to the induction of additional CYP3A4 gene expression via the activation of intracellular nuclear receptors. This induction leads to greater amounts of CYP3A4 protein expression in the endoplasmic reticulum, which can lead to enhanced metabolism and the elimination of telaprevir or boceprevir. The net effect of CYP3A4 induction includes a potential reduction in the local and systemic bioavailability of the DAAs and a higher rate of treatment failure and drug resistance in HCV genotype 1 patients.

DAAs in Liver Transplant Recipients

Because of the known risk of accelerated fibrosis and graft failure from recurrent HCV infections, there is a great deal of interest in using DAAs in combination with peginterferon and ribavirin in liver transplant recipients. However, the coadministration of DAAs and calcineurin inhibitors is a very risky proposition. For example, C max for a single dose of tacrolimus was 9.3‐fold higher when it was coadministered with telaprevir in healthy volunteers, and the half‐life was increased 5‐fold.12 In addition, C max for cyclosporine was increased 1.4‐fold in healthy volunteers, whereas the half‐life was increased 3.5‐fold.

Similar difficulties with immunosuppressive therapy have previously been reported for HIV‐positive transplant recipients receiving antiretroviral agents that inhibit CYP3A4. For example, HIV‐positive liver transplant recipients receiving the potent CYP3A inhibitors ritonavir and lopinavir required as little as 0.5 mg of tacrolimus per week to maintain therapeutic trough levels.13, 14 These data suggest that although DAAs are potentially dangerous, their use in liver transplant recipients with recurrent HCV on calcineurin inhibitors may be possible; however, prospective safety and efficacy studies will be needed.

Summary Recommendations

It is important that providers carefully review all medications before and during the treatment of their HCV genotype 1 patients who are receiving boceprevir or telaprevir. Furthermore, the education of patients receiving DAAs must include explicit instructions to discuss all new medications with the treating provider in a timely manner. Physicians must also remember to discontinue both contraindicated and unnecessary medications when they are initiating therapy with DAAs. A thorough knowledge of potential drug‐drug interactions (or at least a quickly accessible and updated database of absolutely and relatively contraindicated drugs) will also be essential (e.g., www.hep‐druginteractions.org or www.drug‐interactions.com). In addition, a list of safe and effective alternative agents to be used for common ailments and side effects of antiviral therapy that are not expected to cause drug‐drug interactions is needed (Table 4). Lastly, although there are multiple new DAAs under development with favorable efficacy and side‐effect profiles, the metabolism and elimination of each agent by itself and in combination with other commonly used drugs will need to be determined in order to maximize patient safety and optimize clinical outcomes.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Zhou S, Yung Chan S, Cher Goh B, Chan E, Duan W, Huang M, et al. Mechanism‐based inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4 by therapeutic drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet 2005; 44: 279‐304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou S, Chan E, Lim LY, Boelsterli UA, Li SC, Wang J, et al. Therapeutic drugs that behave as mechanism‐based inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A4. Curr Drug Metab 2004; 5: 415‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fontana RJ, Lown KS, Paine MF, Fortlage L, Santella RM, Felton JS, et al. Effects of a chargrilled meat diet on expression of CYP3A, CYP1A, and P‐glycoprotein levels in healthy volunteers. Gastroenterology 1999; 117: 89‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Evans WE, McLeod HL. Pharmacogenomics—drug disposition, drug targets and side effects. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waxman DJ. P450 gene induction by structurally diverse xenochemicals: central role of nuclear receptors CAR, PXR, and PPAR. Arch Biochem Biophys 1999; 369: 11‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leichtman A, Watkins PB. The molecular basis of cyclosporin A metabolism, pharmacokinetics, and drug interactions. Organ Cell Transplant 1999; 2: 177‐182. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee JE, van Heeswijk R, Alves K, Smith F, Garg V. Effect of the hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor telaprevir on the pharmacokinetics of amlodipine and atorvastatin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 4569‐4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telaprevir [package insert]. Boston, MA: Vertex Pharmaceuticals; 2011.

- 9.Boceprevir [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Laboratories; 2011.

- 10. Poordad F, Lawitz E, Gordon SC, Bourliere M, Vierling JM, Paynard T, et al. Concomitant medication use in patients with hepatitis C genotype 1 treated with boceprevir (BOC) combination therapy [abstract]. Hepatology 2011; 54: 799–800. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sherman KE, Rockstroh J, Dietrich DT, Soriano V, Girard P, McCallister S, et al. Telaprevir in combination with peginterferon alfa‐2a/ribavirin in HCV/HIV coinfected patients: 24‐week treatment interim analysis [abstract]. Hepatology 2011; 54: 1431–1432. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garg V, van Heeswijk R, Lee JE, Alves K, Nadkarni P, Luo X. Effect of telaprevir on the pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine and tacrolimus. Hepatology 2011; 54: 20‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jain AK, Venkataramanan R, Shapiro R, Scantlebury VP, Potdar S, Bonham CA, et al. The interaction between antiretroviral agents and tacrolimus in liver and kidney transplant patients. Liver Transpl 2002; 8: 841‐845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jain AB, Venkataramanan R, Eghtesad B, Marcos A, Ragni M, Shapiro R, et al. Effect of coadministered lopinavir and ritonavir (Kaletra) on tacrolimus blood concentration in liver transplantation patients. Liver Transpl 2003; 9: 954‐960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]