Watch a video presentation of this article

Abbreviations

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- LT

liver transplantation

- PS

performance status

Estimation of prognosis estimation is one of the main issues facing physicians when a patient is diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Years ago, it was not difficult to estimate prognosis, because the majority of HCC patients were diagnosed at an advanced, symptomatic stage that usually coincided with liver decompensation. At that point, treatment was not feasible, and the short‐term prognosis was dismal. Accordingly, HCC patients with impaired performance status or who fit into the Child‐Pugh class C category with no chance for being transplanted were classified as end‐stage, and these patients were easily recognized in daily clinical practice. This pessimistic scenario has changed completely. More patients receive an early diagnosis of HCC on account of surveillance practices and effective therapy of patients treated at an early stage is associated with a median survival beyond 5 years. Therefore, our aim today, once an HCC has been identified, is to accurately predict the expected outcome and help physicians and their patients to select the best treatment option.1

HCC is frequently associated with chronic liver disease and, therefore, any attempt to determine the prognosis should consider not only the tumor burden but also the degree of liver function impairment. Moreover, the assessment of cancer‐related symptoms, a well‐established procedure in oncology practice, should be incorporated in the prognosis, since symptoms have shown an unquestionable predictive value.2, 3 Several proposals have been raised to stratify patients according to the expected outcome. Table 1 describes the proposals that have gained more visibility.4 Most of these proposals resulted from an analysis of the association of any clinical or pathological parameter with survival, ultimately resulting in a division according to an equation derived from the multivariate Cox regression analysis or to a score obtained by the sum of the values allocated to the significant parameters. Unfortunately, in most of these staging systems, there is no assessment of the presence of cancer‐related symptoms. Furthermore, any system aimed to be clinically successful should optimally attempt to link prognostic prediction and treatment indication. Regrettably, this is not the case with any of the scoring or category allocation systems, which, to some extent, may include in the same category patients who would be candidates for curative therapy and patients who would merely receive palliation.4

Table 1.

Prognostic Systems to Predict Outcome in HCC Patients

| Prognostic System (Year) | N | Tumor Stage | Liver Function | Health Status | Stages/Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okuda (1985) | 850 | Tumor involvement >50% | Bilirubin, albumin, ascites | — | I, II, III |

| CLIP (1998) | 435 | Tumor morphology, AFP, portal vein invasion | Child‐Pugh | — | 0‐6 |

| GRETCH (1999) | 761 | Portal vein invasion, AFP | Bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase | Karnofsky | A‐C |

| BCLC (1999) | Number of nodules, tumor size, portal vein invasion, metastases | Child‐Pugh, portal hypertension | Performance status | 0, A‐D | |

| CUPI (2002) | 926 | TNM, AFP | Bilirubin, ascites, alkaline phosphatase | Symptoms | 0‐12 (3 risk groups) |

| JIS (2003) | 722 | TNM by LCSGJ | Child‐Pugh | — | 0‐5 |

| SLIDE (2004) | 177 | TNM by LCSGJ | Liver damage by LCSGJ, PIVKA | — | 0‐3 |

| AJCC TNM (2002) | Number of nodules, tumor size, portal vein invasion, metastases | — | — | I, II, III, IV | |

| Tokyo (2005) | 403 | Number of nodules, tumor size | Albumin, bilirubin | — | 0‐8 |

| Taipei Integrated (2010) | 2030 | Total tumor volume, AFP | Child‐Pugh | — | 0‐6 |

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha‐fetoprotein; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CLIP, Cancer of the Liver Italian Program; CUPI, Chinese University Prognostic Index; GRETCH, Groupe d'Etude de Traitement du Carcinoma; JIS, Japan Integrated Staging; LCSGJ, Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan; PIVKA, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist; TNM, tumor‐node‐metastasis.

Adapted with permission from Seminars in Liver Disease.4 Copyright 2010, Thieme.

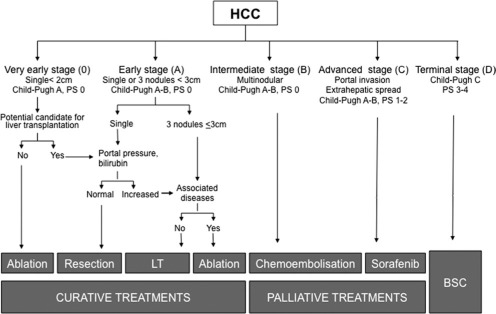

The intent of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system is to surpass the limitations of previous systems. The BCLC classification, which was introduced in 19995 and subsequently refined and updated,1, 6 is the only system that stratifies patients according to outcome and, simultaneously, links it with treatment indication (Fig. 1). It has been validated in different settings, establishes treatment recommendations for different evolutionary HCCs, and has been supported by prominent scientific societies in the United States and Europe.7, 8 Finally, a recent meta‐analysis analyzing the outcome of 1,927 patients with untreated HCC externally validated the prognostic ability of the BCLC system and confirmed that Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, degree of liver function impairment, and portal vein thrombosis are robust predictors of death in untreated HCC patients. More interestingly, although a remarkable difference in survival was found between occidental (North American and European) and oriental (Asia‐Pacific, with high prevalence of hepatitis B virus–related liver disease) populations, the potential role of hepatitis B virus as a prognostic factor disappeared in the multivariate analysis.3

Figure 1.

BCLC staging and treatment strategy. Abbreviations: BSC, best supportive care; LT, liver transplantation; PS, performance status.

Four Main Categories of the BCLC Staging System

Early Stage (BCLC Stage 0‐A)

Patients with solitary lesions or up to three lesions <3 cm are classified as stage 0‐A. The natural history of early stage HCC is not very well known. All the available data come from old cohort studies reporting a 3‐year survival between 10% and 65%. However, these studies were flawed by incomplete disease staging, poor follow‐up, and undisclosed associated conditions. These patients are candidates for potentially curative treatments (resection, liver transplantation, or ablation) that change the natural history of the disease and may offer a 5‐year survival of 50% to 70%. There is a particular subgroup of patients categorized as very early HCC (BCLC 0) with well‐preserved liver function (Child‐Pugh class A) diagnosed with a single asymptomatic HCC <2 cm that lacks vascular invasion or satellites. It corresponds to the carcinoma in situ entity that, if ablated or resected, would have an excellent outcome with almost no risk of recurrence.

Intermediate Stage (BCLC Stage B)

Stage B applies to patients who have single large HCCs and are not candidates for surgery and patients with multifocal disease who are asymptomatic and do not present with vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread. The expected median survival is approximately 16 months with wide variation according to confounding factors.3, 9 The treatment of choice is chemoembolization,7, 8 and in well‐selected candidates who are treated with state‐of‐the‐art techniques, the median survival may surpass 50 months.10, 11

Advanced Stage (BCLC Stage C)

Stage C applies to patients who have evolved beyond the stage B profile. They may have symptoms and/or present vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread. The expected median survival without treatment is well established and is around 4‐8 months.3, 9 Up to now, the only treatment that has shown survival benefit and has been approved in this setting is sorafenib.12, 13

End‐Stage (BCLC Stage D)

The prognosis for stage D patients is dismal, with an expected survival of less than 3 months. The best palliative care should be offered to these patients.

Conclusion

Although there are advantages to the BCLC staging system, there is room for further refinement. Liver function is assessed through Child‐Pugh classification, but class B includes a wide spectrum of patients. Similarly, presence of ascites within Child‐Pugh class A already marks impaired prognosis, and this should be factored into individual patient evaluation and treatment proposal. Furthermore, the assessment of the extent of the portal vein and extrahepatic involvement might allow an improvement in the BCLC's prognostic ability. In addition, biomarkers may also allow a better stratification. Undoubtedly, increased alpha‐fetoprotein is associated with poorer prognosis, but we lack robust data upon which to define cutoff values that would influence treatment decisions. Other tumor markers may refine the prognostic prediction within a statistical model, but cannot be yet incorporated in the individual assessment of a specific patient. Finally, studies of HCC have indicated that outcome may be predicted by molecular profiling of tumor and adjacent nontumoral tissue.1 However, translation of this information into treatment decision‐making requires additional validation.8

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2012;379:1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Llovet JM, Bustamante J, Castells A, Vilana R, Ayuso Mdel C, Sala M, et al. Natural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for the design and evaluation of therapeutic trials. Hepatology 1999;29:62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cabibbo G, Enea M, Attanasio M, Bruix J, Craxi A, Camma C. A meta‐analysis of survival rates of untreated patients in randomized clinical trials of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2010;51:1274–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forner A, Reig ME, Rodriguez de Lope C, Bruix J. Current strategy for staging and treatment: the BCLC update and future prospects. Semin Liver Dis 2010;30:61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis 1999;19:329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2003;362:1907–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. European Association for the Study of the Liver; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer .EASL‐EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beaugrand M, Sala M, Degos F, Sherman M, Bolondi L, Evans T, et al. Treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma by seocalcitol (a vit D analogue): an international randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled study in 747 patients. J Hepatol 2003;42:17A. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burrel M, Reig M, Forner A, Barrufet M, Lope CR, Tremosini S, et al. Survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) using DC Beads. Implications for clinical practice and trial design. J Hepatol 2012;56:1330–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malagari K, Pomoni M, Moschouris H, Bouma E, Koskinas J, Stefaniotou A, et al. Chemoembolization with doxorubicin‐eluting beads for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: five‐year survival analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2012;35:1119–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Llovet J, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia‐Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]