Ultimate and proximate explanations of men’s physical intimate partner violence (IPV) against women have been proposed. An ultimate explanation posits that IPV is used to achieve a selfish fitness-relevant outcome, and predicts that IPV is associated with greater marital fertility. Proximate IPV explanations contain either complementary strategic components (e.g. men’s desire for partner control), non-strategic components (e.g. men’s self-regulatory failure), or both strategic and non-strategic components involving social learning. Consistent with an expectation from an ultimate IPV explanation, we find that IPV predicts greater marital fertility among Tsimane forager-horticulturalists of Bolivia (n=133 marriages, 105 women). This result is robust to using between- versus within-subject comparisons, and considering secular changes, reverse causality, recall bias and other factors (e.g. women’s preference for high status men who may be more aggressive than lower status men). Consistent with a complementary expectation from a strategic proximate IPV explanation, greater IPV rate is associated with men’s attitudes favoring intersexual control. Neither men’s propensity for intrasexual physical aggression, nor men’s or women’s childhood exposure to family violence predict IPV rate. Our results suggest a psychological and behavioral mechanism through which men exert direct influence over marital fertility, which may manifest when spouses differ in preferred family sizes.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) – defined as any intended physical, sexual or psychological harm toward a current or former romantic partner1 – is a ubiquitous global phenomenon, particularly against women2,3, with adverse health and economic consequences for individuals, families and communities. Despite diverse intervention strategies to minimize incidence4, the ubiquity and persistence of IPV is a conundrum for both policymakers and evolutionary scientists. In addition to acute trauma, health consequences for female IPV victims include chronic pain, gynecological problems, unwanted pregnancy, fetal loss, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression5,6. Moreover, children of women abused during pregnancy experience greater risk of low birth weight7, suggesting that children may be indirect victims of IPV. Regarding men’s physical IPV against women – the focus of this paper – ultimate and proximate explanations have been proposed. An ultimate explanation posits that IPV or its threat is used by a man to achieve a selfish fitness-relevant outcome through manipulation of a woman’s sexual or other behavior in the short- or long-term8,9. Proximate IPV explanations are diverse: some contain complementary “strategic” components related to a desire for partner control or bargaining power within a couple or society10–13, others non-strategic components related to men’s self-regulatory failure, psychosocial stress or their interaction14, and others both strategic and non-strategic components involving social learning15,16. Our use of the term “strategic” in this context does not presume or imply deliberate strategizing or awareness by the perpetrator of the ultimate function of IPV; instead we use this term to refer to those IPV motivations that implicate a man’s self-interest in a manner consistent with an ultimate (i.e. fitness-enhancing) function, albeit at a different level of analysis. Non-strategic, in contrast, refers to those IPV motivations that are inconsistent with male fitness maximization.

This paper has two goals. First, we examine a fundamental prediction of an ultimate IPV explanation focusing on fitness consequences of IPV, in a high fertility forager-horticultural population, the Tsimane of the Bolivian Amazon. Specifically, we test whether IPV is associated with greater marital fertility, using a between- and within-participant design and detailed retrospective survey data spanning 1,905 marital risk-years (n=133 marriages of 105 women). Explanations of human sexual aggression in evolutionary psychology8,17,18 posit that risk of paternity uncertainty promotes men’s jealousy, which in turn promotes a suite of men’s controlling attitudes (e.g. toward partner vigilance) and “mate guarding” behaviors (e.g. IPV), jointly serving to secure or protect exclusive sexual access to a mate and ensure that paternal investment is directed toward biological offspring19–24. Of course, men’s coercive control need not be limited to preventing or punishing women’s sexual infidelity; IPV may be used to influence behavioral outcomes in any domain, so that a wife is more likely to defer to her husband’s immediate fitness-relevant goals, while setting a precedent for future deference.

A related literature in behavioural ecology and evolutionary biology focuses on sexual conflict (i.e. conflict between the evolutionary interests of individuals of the two sexes) over mating and parental investment, given differing genetic interests of reproductive partners and asymmetries between sexes in the costs and benefits of reproduction25,26. Because males typically invest less than females in parental care and are susceptible to cuckoldry when pair-bonded, males are typically expected to have a higher optimum mating frequency than females for maximizing fitness. Conflict over optimal mating rate can, under various circumstances, result in a male physically coercing a female to mate with him, leading some researchers to regard sexual coercion as a third form of sexual selection, distinct from intrasexual competition for mates and intersexual mate choice.

While mounting evidence across a wide range of species, including nonhuman primates, and across diverse mating systems is consistent with a primary prediction of the “sexual coercion hypothesis” – that male aggression toward females increases male fitness27–32, the prediction that IPV increases marital fertility, which is central to an ultimate IPV explanation, has not yet been tested in a natural fertility population. We thus test for a positive association between IPV and marital fertility rate, both across women and within women across marriages; this latter test permits assessment of whether women experiencing IPV have higher fertility than they themselves would have had if they had not experienced IPV. We also examine time-dependence between IPV and marital fertility, and whether results are artifacts of either secular changes, reverse causality, recall bias or other factors, such as women’s preference for aggressive men, or for high status men who happen to be more aggressive than lower status men.

There are several reasons why the Tsimane provide an interesting test of an ultimate IPV explanation. Tsimane total fertility rate is nine births per woman and birth control is rarely used33, so covariation between IPV and fertility rate is easier to detect relative to industrialized populations, where sexual activity and reproduction are decoupled. Despite the generally collaborative nature of Tsimane marriages, interests of husbands and wives do not always coincide and there is substantial room for spousal conflicts of interest. Generally speaking, men experience lower costs of investment per child than women, and under certain socioecological conditions, this may result in larger ideal family sizes (IFS) for men than women, as observed among Tsimane33. Interestingly, spousal disparity (husband-wife) in IFS is positively associated with “excess fertility” (parity – IFS) for Tsimane women33. If husbands’ coercion lowers wives’ reproductive autonomy, as expected from an ultimate IPV explanation, then husbands’ larger IFS may lead to higher marital fertility than what their wives desire, and/or may encourage wives to adjust their IFS to accommodate their husbands’ needs. Additionally, despite room for spousal conflict and the use of IPV as a potentially effective means of sexual coercion, Tsimane lack residential privacy due to large extended families living in closely-spaced open houses, which increases social costs to perpetrators that can restrict IPV occurrence. Nevertheless, a high lifetime IPV prevalence among Tsimane women (85%)22 suggests that, even in a matrilocal population like the Tsimane, presence of kin or other valued social partners is not sufficient to lower IPV risk. This high lifetime IPV prevalence is puzzling because Tsimane lack formal patriarchal institutions (e.g. legal, political, economic), any recent history of large-scale (e.g. inter-community) violence, and media exposure to violence.

A second goal of this paper is to identify among Tsimane psychological and behavioral IPV determinants, and in so doing, consider the relevance of proximate IPV explanations that may include complementary strategic and non-strategic components. We test predictions of three proximate IPV explanations. First, we test whether a husband’s attitudes toward controlling his wife are positively associated with his propensity to perpetrate IPV9. This association is consistent with an ultimate IPV explanation, and identifies a psychological mechanism promoting men’s coercive behavior that can increase rate of copulation in marriage, minimize risks of a wife’s infidelity, and increase men’s marital fertility.

A second proximate IPV explanation we test emphasizes a causal role for men’s aggressive personality34,35, which predicts that a man’s propensity to engage in intrasexual physical aggression is positively associated with his propensity to perpetrate IPV. In principle, this prediction can be consistent with an ultimate IPV explanation, for example, if aggressive men are more dominant (i.e. better able to inflict costs on others) and gain fitness advantages associated with such dominance36. However, much of the relevant literature posits that men’s aggressive personality is indicative of broader self-regulatory failure (e.g. lack of dispositional self-control34,35 or from male psychopathology14) that triggers IPV perpetration independently or in interaction with psychosocial stress (e.g. related to absolute or relative poverty37 or occupational stress38). In the current context, Tsimane lack norms linking physical aggression to broader notions of “manhood” as they pertain to interpersonal relations among men.

A third proximate IPV explanation we test emphasizes a causal role for socially learned attitudes of what constitutes “appropriate” adult behavior15,16, which predicts that men’s and women’s childhood exposure to family violence is positively associated with men’s propensity to perpetrate IPV. Childhood exposure to family violence can facilitate learning and internalizing a belief that IPV is justified for various reasons containing strategic and/or non-strategic components. Consider a household in which, first, a wife confronts her husband about his ongoing infidelities, resulting in his use of IPV to quell her protests, and shortly afterward, the same husband, now inebriated and frustrated by his wife’s complaints to him over his neglect of chores, unexpectedly uses force to abruptly end their dispute. In this example, co-resident children’s social learning and internalization of expectations (e.g. men’s infidelity is common), attitudes (e.g. men are justified in managing frustration with alcohol and hasty aggression) and behavior (e.g. men “resolve” marital conflict through IPV) are temporally linked, and both strategic and non-strategic components may be modeled and imitated, facilitating intergenerational transmission of IPV. Interestingly, from an evolutionary perspective, one might also expect a positive association between childhood exposure to IPV and men’s propensity to perpetrate IPV. This is because, despite direct costs to women of experiencing IPV, the potential fitness benefits that may accrue to abusive men can, in principle, generate indirect fitness benefits to women through their male children. This Fisherian notion suggests that women’s preferences for abusive men can, in theory, originate regardless of social learning.

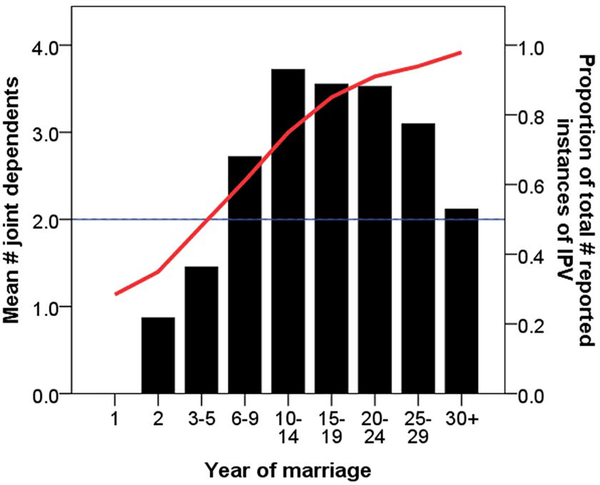

IPV is most common in the first year of marriage, prior to reproduction (SupplementaryFigure1). During this first year, wives experienced, on average, 28% of all IPV incidents that eventually occurred in marriage (Figure 1). Among the 89 wives (85%) experiencing any IPV in their lifetime, median number of total lifetime IPV incidents=9 (mean=21.0, SD=27.8, min=1, max=135) and median number of IPV incidents/year=0.8 (mean=1.4, SD=1.5, min=0.03, max=8.7). Compared to wives who never experienced any IPV in their lifetime, wives experiencing IPV are younger at the time of interview, have shorter inter-birth intervals (IBIs), and have more births-for-age and surviving offspring-for-age (Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Figure 2). In contrast, there are no significant differences between wives who ever versus never experienced IPV in age at menarche, first marriage or first birth, prevalence of remarriage, anthropometric status or indicators of modernization (i.e. schooling and Spanish fluency). Wives experiencing any IPV in their lifetime are more likely than wives who never experienced IPV to have husbands with greater Spanish fluency (both absolutely and relative to the wife; Supplementary Table 2). In contrast, there are no significant differences between husbands whose wives ever versus never experienced IPV in age (either absolutely or relative to the wife), age at first marriage or first birth, prevalence of remarriage, anthropometric status (either absolutely or relative to the wife) or schooling.

Figure 1.

Cumulative relative frequency of IPV (red line) by year of marriage and mean number of joint dependent offspring <10 years old (black bars). Wives experience, on average, 50% of all IPV incidents before year 6 of marriage, when a couple averages 1.5 joint dependents (n=89 wives; omits 16 wives [15%] who never experienced any IPV in their lifetime).

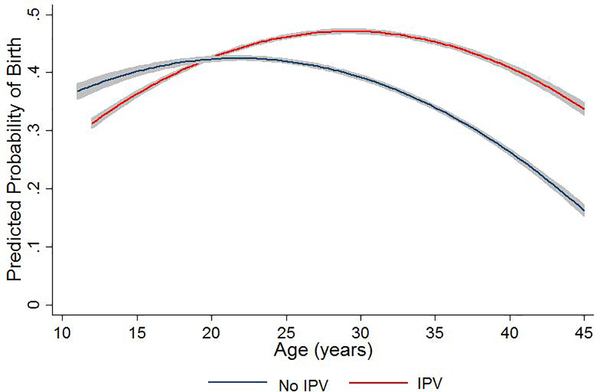

Wives experiencing IPV in a given year show increased odds of birth that year controlling for confounders related to demographics, anthropometrics, modernization and village membership (adjusted OR=1.246, 95% CI: 1.021–1.520, p=0.030; Supplementary Table 3: model 1). Inclusion of an IPV-by-wife’s age interaction term yields a significant parameter estimate (p=0.009; Supplementary Table 3: model 2), indicating an increasing difference in annual fertility between abused versus non-abused wives with age (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of birth/year (95% CI) by a wife’s age and whether she reports IPV that year (n=1,905 marital years, 105 wives). Fitted values are derived from Supplementary Table 3: model 2 (holding controls at sample means). Abused wives attain peak annual fertility at age 29 years (predicted probability=0.43 vs. 0.35 for age-matched non-abused wives), while non-abused wives attain peak fertility at age 22 years (predicted probability=0.38 vs. 0.40 for age-matched abused wives).

The positive association between IPV and fertility could be an artifact of secular change, because younger women both have higher annual fertility and are more likely to experience IPV than older women when they were younger (Supplementary Figure 3). To determine the potential artifactual effect of secular change, we add time period dummies (indicating terciles of years comprising the retrospective database) to model 2 in Supplementary Table 3 (see Supplementary Table 4: model 1), and find a nearly identical parameter estimate for the IPV-by-wife’s age interaction term (adjusted OR=1.035, p=0.003). This estimate increases if we omit the most recent time period (2003–2012; Supplementary Table 4: model 2), and is nearly identical to that shown in Supplementary Table 4: model 1 if we omit the oldest time period (Supplementary Table 5), suggesting that the positive association between IPV and fertility is not an artifact of relatively recent increases in annual fertility and IPV exposure.

The positive association between IPV and fertility is also not an artifact of reverse causality, whereby having higher fertility increases risk of IPV. There are no significant main effects of either annual fertility or number of joint dependents (< age 10 years) on the probability of experiencing IPV per year after controlling for potential confounders (Supplementary Table 6: model 1; using same controls shown in Supplementary Table 4), nor do these fertility measures interact to significantly predict IPV risk (Supplementary Table 6: model 2).

The positive association between IPV and fertility could also result from recall bias, for example, if older women, having to recall older events than younger women, are more likely to under (or over) report IPV, especially when less (or more) fertile. However, there is no evidence of systematic bias in reporting IPV across time periods (see Supplementary Figure 3B): within a given age category and relative to women from more recent cohorts, older women report both lower (<25 years old) and higher (35–39 years old) or comparable (25–34 and 40–45 years old) annual IPV rates. In addition, within each time period, annual IPV risk is negatively and significantly predicted by a wife’s age, with similar declines in slope (1953–1991: adjusted ORWife’s age=0.959 [95% CI: 0.922–0.998]; 1992–2002: adjusted ORWife’s age=0.928 [95% CI: 0.875–0.985]; 2003–2012: adjusted ORWife’s age=0.897 [95% CI: 0.858–0.938], GEE analysis controlling for village dummies). For the oldest cohort, age-related decline in IPV risk is evident despite relatively minimal change in fertility rate before age 35 (Supplementary Figure 3A). These results, coupled with the robustness checks mentioned above (i.e. omitting earliest and latest time periods from analyses), suggest that the positive association between IPV and fertility is not an artifact of systematic recall bias.

The positive association between IPV and fertility could also result from women’s preference for higher status men who happen to be more physically aggressive than lower status men. If this “IPV-as-status-byproduct” interpretation were correct, then we should find a positive association between IPV and fertility for higher but not lower status men. However, using two temporally stable correlates of adult male status – men’s age at first marriage and Spanish fluency – and for each status sub-group (i.e. higher and lower) analyzing the effect of IPV on probability of birth/year, we find that IPV positively and significantly predicts marital fertility for both higher and lower status men (using men’s age at first marriage, the IPV-by-wife’s age interaction OR for men marrying earlier [below median] vs. later [all others]=1.056 [1.021–1.092] vs. 1.030 [1.001–1.059], using same controls shown in Supplementary Table 4; using men’s Spanish fluency, the IPV-by-wife’s age interaction OR for fluent vs. non-fluent men=1.116 [1.023–1.218] vs. 1.030 [1.001–1.060]). In addition, neither men’s age at first marriage nor Spanish fluency is associated with men’s attitudes regarding intrasexual physical aggression or actual physical aggression toward other men in the past year, indicating a decoupling of male status and intrasexual aggression that is not consistent with the IPV-as-status-byproduct interpretation.

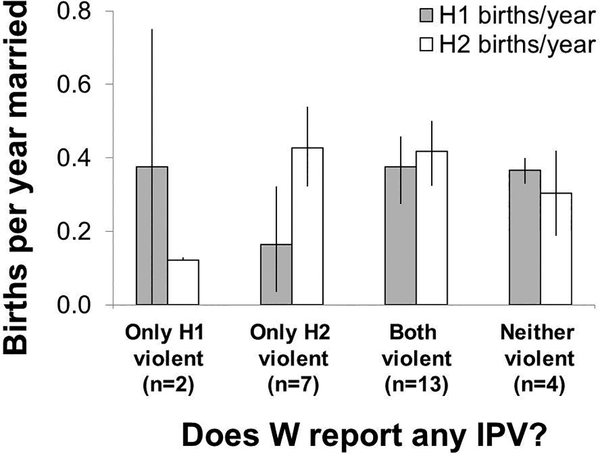

Leveraging variation in fertility and IPV rates within women across marriages (n=26 wives who remarried), we test whether any IPV experience with each husband is associated with greater annual fertility with that husband (mean years married to first husband=5.6, range: 1–28; mean years married to second husband=13.6, range: 1–26). Wives experiencing any IPV with a first husband, but not a second, show greater annual fertility with the first (0.375 vs. 0.121, respectively), although a small sample size (n=2 wives) precludes a formal test of this difference (Figure 3). Wives experiencing any IPV with a second husband, but not a first, show greater annual fertility with the second (0.426 [bootstrapped 95% CI: 0.323–0.540] vs. 0.164 [bootstrapped 95% CI: 0.036–0.322]). This fertility increase with the second husband approaches significance (related-samples Wilcoxon Signed Rank p=0.063) despite a small sample size (n=7 wives; mean years between the start of each marriage=2.7; range: 1–5). We found no significant differences across marriages in rates of IPV or fertility by whether a first marriage dissolved because of divorce or a husband’s death.

Figure 3.

Annual fertility (bootstrapped 95% CI) within marriage for wives (W) who remarried (n=26), by whether a wife experiences IPV with each husband (H). All but two wives remarried once, and to minimize potential recall bias we analyzed the two most recent marriages for the two wives who remarried twice. Wife’s mean±SD age at remarriage=24.3±8.0.

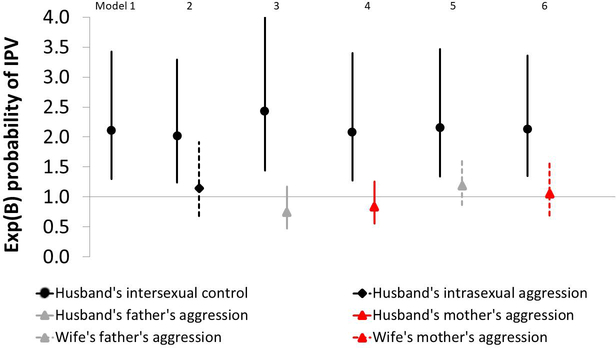

To consider the relevance of proximate IPV explanations, we test whether IPV is predicted by: (i) a husband’s attitudes regarding intersexual control; (ii) a husband’s attitudes regarding intrasexual physical aggression (reflecting actual aggression toward other men; see Methods); and (iii) paternal and (iv) maternal physical aggression experienced or witnessed by husbands and wives during childhood. Controlling for predictors (p<0.1) shown in Supplementary Table 4, annual IPV risk is positively predicted by a husband’s attitudes regarding intersexual control (adjusted OR=2.108, p=0.003, Supplementary Table 7: model 1), but not by a husband’s attitudes regarding intrasexual physical aggression (adjusted OR=1.147, p=0.602, Supplementary Table 7: model 2), nor by a husband’s paternal (adjusted OR=0.747, p=0.204, Supplementary Table 7: model 3) or maternal (adjusted OR=0.834, p=0.385, Supplementary Table 7: model 4) aggression during childhood, nor by a wife’s paternal (adjusted OR=1.183, p=0.298, Supplementary Table 7: model 5) or maternal (adjusted OR=1.049, p=0.824, Supplementary Table 7: model 6) aggression during childhood (Figure 4). Men’s attitudes regarding intersexual control is positively associated with men’s paternal aggression during childhood (Pearson r=0.403, p≤0.01) and with men’s attitudes regarding intrasexual physical aggression (Pearson r=0.432, p≤0.01) (Supplementary Table 13), suggesting that proximate IPV motivations may be linked. But in models omitting a husband’s attitudes regarding intersexual control, annual IPV risk is not predicted by a husband’s attitudes regarding intrasexual physical aggression, or by a husband’s or wife’s paternal or maternal aggression during childhood.

Figure 4.

Effect of a husband’s attitudes regarding intersexual control (all models) and intrasexual physical aggression (model 2), and a husband’s (models 3–4) and wife’s (models 5–6) childhood exposure to family violence on the probability of a wife reporting IPV/year (n=909 marital years, 49 wives; parameter estimates and 95% CIs are shown in Supplementary Table 7).

We tested for other potential confounders related to demographics (i.e. spousal age difference, prior marriage), anthropometrics (i.e. height or weight [wife’s, husband’s or spousal differences]) and modernization (i.e. schooling [wife’s, husband’s, or spousal difference]) but none significantly predicted IPV risk.

We examined fertility consequences of IPV, and behavioral and psychological IPV determinants in a high fertility population of Bolivian forager-horticulturalists to test predictions of ultimate and proximate IPV explanations. Consistent with a fundamental expectation from an ultimate IPV explanation, we find that IPV predicts greater marital fertility; consistent with a complementary expectation from a strategic proximate IPV explanation, greater IPV rate is associated with men’s attitudes favoring intersexual control. These results highlight a prominent sexual conflict even within the context of monogamous marriage in a population lacking formal patriarchal institutions and other widespread practices that limit women’s reproductive autonomy (e.g. female genital mutilation, marital restrictions). Sex-specific benefits and costs of reproduction (e.g. maternal depletion) and differing genetic interests of reproductive partners are expected to generate sex differences in optimal values of fitness-relevant traits (i.e. “sexual conflict traits”25,39); this may include family size preferences, with men, under certain socioecological conditions (Tsimane included) favoring larger families than women, partly due to men’s reduced physiological and opportunity costs of birth33. Overt behavioral conflict between reproductive partners is expected if optimal outcomes for each partner cannot be achieved simultaneously39. Our results suggest a psychological and behavioral mechanism through which men exert direct influence over marital fertility, as men’s desire for partner control and associated IPV may increase rate of in-pair copulation (i.e. direct coercion27). These and other coercive tactics, for example, intimidation through verbal aggression, facilitated by sexual dimorphism in strength, can serve to increase men’s mating effort in the short- or long-term, both within and outside of marriage22,40. It may also be in a wife’s interests to acquiesce to mating because the direct costs of resistance exceed costs of allowing mating. In general, this interpretation is not inconsistent with and may actually complement one emphasizing conformity to and internalization of local gender norms that promote a husband’s dominance over a wife (e.g. regarding wifely obedience and “appropriate” consequences for disobedience), even in a population lacking formal patriarchal institutions. While specific pathways linking desired spousal control and reproductive effort require further exploration, a mediation analysis indicates that Tsimane men’s controlling attitudes do not predict wives’ fertility independently of IPV, nor do they diminish the positive association between IPV and fertility.

A prediction of a proximate IPV explanation emphasizing a causal role for men’s aggressive personality is that IPV perpetration positively co-varies with men’s propensity to engage in intrasexual physical aggression34,41. Using data on men’s attitudes regarding intrasexual aggression, itself predictive of actual aggression toward other men in the past year (see Methods), we find that neither attitudinal nor behavioral (past year) measures of intrasexual aggressive tendencies predict IPV perpetration, indicating a decoupling of men’s aggression towards wives versus other men. It is thus unlikely that the positive association between IPV and fertility reflects women’s preference for aggressive men, or that IPV is a byproduct of intrasexual competition involving aggression. Our prior Tsimane research22,40 indicates that men’s jealousy over women’s infidelity does not precipitate most instances of verbal or physical aggression in marriage. Instead, based on couple-level data on marital arguments and IPV, our prior research indicates that it is Tsimane men’s infidelity (perceived or real), not women’s, that precipitates most instances of verbal conflict in marriage and wife abuse. Rather than resulting primarily from men’s attempts to limit women’s access to other mating partners (i.e. indirect coercion27), Tsimane IPV may result from men’s attempts to “resolve” sexual conflict over preferred family size through direct coercion, although both strategies may co-occur. Future research utilizing couple-level data that focuses on the temporal sequence of marital conflict will contribute to an understanding of couple-level contextual dynamics, including which partner initiates conflict and broader escalation and conciliatory processes.

IPV tends to be more frequent and severe in lower socioeconomic status sub-groups37, but IPV is not restricted to lower status men. Even among Tsimane, who compared to other populations in the IPV literature show limited variance in men’s resource holdings, it is possible that instead of reflecting a sexual coercion strategy, the positive association between IPV and fertility could instead reflect women’s preference for high status men, who are also more aggressive than lower status men. Our prior research has shown that abusive Tsimane husbands are more likely to engage in extramarital affairs22,40, and while we have interpreted this as reflecting a strategic response (i.e. men use IPV in part to control women’s responses to men’s diversion of household resources), an alternative interpretation is that abusers (vs. non-abusers) can “afford” extramarital affairs because of their greater resource holding potential, which is desired by women. However, contrary to this alternative IPV-as-status-byproduct interpretation, we find that IPV predicts higher marital fertility for both higher and lower status men, and that men’s status is uncorrelated with men’s attitudinal or behavioral measures of intrasexual physical aggression. Moreover, men’s status is not significantly associated with men’s attitudes favoring intersexual control, contrary to the expectation that feelings of “sexual proprietariness9“ are stronger in lower status men because of their elevated risk of losing a wife. Together, these findings indicate that Tsimane men across the status continuum strategically use IPV to achieve higher marital fertility, although it is noteworthy that the IPV-by-wife’s age interaction effect is stronger among higher versus lower status men. IPV may be a more effective strategy for high status men because they incur fewer social costs of IPV (e.g. retaliation from a wife’s kin). Generally speaking, our findings do not directly support a prediction from a proximate IPV explanation that stress related to low status increases IPV risk, either independently or in interaction with men’s aggressive personality.

A proximate IPV explanation involving social learning posits that children learn how to behave by experiencing how others treat them and by observing how their parents treat each other. Social learning (e.g. of expectations, attitudes or behavior) can provide a mechanism by which IPV is viewed as an appropriate response when sexual or other conflicts emerge. Yet we find no support for a prediction of this social learning explanation: childhood exposure to family violence does not predict risk of either perpetrating or experiencing IPV. This null finding holds if we utilize composite measures of physical aggression that incorporate overall paternal and maternal aggression (i.e. toward a spouse, ego and ego’s siblings; see Supplementary Table 7: models 3–6), and if we utilize specific measures of dyadic paternal aggression toward ego or a spouse. While the intergenerational transmission of IPV is one of the best studied IPV explanations16, it remains challenging to identify particular traits being modeled and imitated (e.g. expectations about a partner’s marital commitment, attitudes toward resolving conflicts peacefully, alcoholism) and address their inter-relationships in a comprehensive way that explains why only certain traits are transmitted and reliably associated with IPV. In principle, social learning of both strategic and non-strategic IPV motivations can occur. The former can occur through positive reinforcement of aggression, although Tsimane lack norms linking aggression and masculinity, or norms justifying physical force to resolve conflicts among men. The latter can occur through failure to learn how to manage marital conflict appropriately. Nevertheless, in small-scale societies like the Tsimane, IPV perpetrators face substantial costs that should limit even greater IPV occurrence, including reputational damage and social sanctions, injury if IPV provokes retaliation by the wife and/or her kin, divorce and loss of future reproductive opportunities with a wife, and marital strife which could lead wives to withdraw and/or reduce work effort as a means of protest22.

Important study limitations should be considered. First, we focus only on physical IPV against wives and thus we likely underestimate IPV prevalence. Second, social desirability bias often leads to IPV underreporting, yet Tsimane report a high lifetime and annual IPV prevalence, and couple-level data reveal substantial spousal consistency in reporting IPV (see Methods). For these reasons, together with a retrospective interview design which we believe minimized study intrusiveness (since IPV is most common early in marriage and women’s mean marital duration at the time of interview=14.3 years), we have no reason to suspect that potential reticence or deceit in our interview data produce the observed empirical associations reported here. Third, our retrospective study design lends itself to recall bias, although we find no empirical support that recall bias influences results. Fourth, we lack data on women’s attitudes toward men’s desires for intersexual control and men’s use of aggression (intra and intersexual), which are useful for further interrogating social learning and other proximate IPV explanations. Furthermore, we assess attitudinal constructs with relatively simple measures that may not accurately represent the complexity of these constructs. We also lack data on men’s and women’s fertility desires (e.g. IFS), which are useful for understanding the nature of spousal bargaining when conflicts emerge over family planning. Unfortunately we do not have data on women’s counter-strategies to minimize IPV risk; sexual conflict models propose an evolutionary arms race, whereby the costs to one sex from the other’s behavior create strong selective pressure for adaptive responses42. Given the emphasis of sexual conflict theory39,43 on the dynamic, bidirectional nature of sex differences in optimal values of many fitness-relevant traits (e.g. whether to mate, when, how often, how long, how exclusively) it is misleading to perceive sexually coercive behavior as the result of particular traits of particular men, rather than as a conditional response of men to women’s behavior that takes into account costs and benefits of alternatives for both sexes44. It is also potentially misleading to only consider men’s use of IPV, without considering couple-level contextual dynamics including marital disputes and women’s use of IPV. Lastly, the sample size for our within-individual analysis is small, but we find similar results for within- and between-individual analyses, supporting ultimate and strategic proximate IPV explanations.

To conclude, effectively minimizing the deleterious impacts of IPV for individuals, families and communities requires an accurate understanding of factors causing IPV. A general theory – spanning proximate and ultimate levels of analysis – that explains why men engage in IPV, and that predicts the conditions under which IPV is more likely to occur would be useful in the design of public health interventions to lower IPV incidence and mitigate its deleterious effects. An implication of this study, for research and intervention design in public health, is that the conditions that increase spousal conflict over women’s reproductive autonomy should be the target of explanatory models and attempts to lower IPV incidence.

METHODS

Tsimane are semi-sedentary forager-horticulturalists living along the Maniqui River and surrounding areas in the Beni Department of Bolivia. Adults typically choose their own spouses, but kin may also facilitate marriages45. There are no formal marriage ceremonies and a couple is considered married when they sleep together in the same house. Post-marital residence rules are flexible but emphasize matrilocality early in marriage. Cross-cousin marriage is common and there are no formal marital restrictions. Birth control, mostly in the form of Depo-Provera, is only recently available from a few health workers and in pharmacies in town, yet <5% of reproductive-age women report usage46; other forms of modern birth control are almost never used. Low birth control usage is largely due to a combination of lack of knowledge about its use, cost and cultural valuation of large family size.

JS obtained UNM IRB approval and informed verbal consent from Tsimane government, village leaders and participants before conducting the study. IPV data were collected by JS and a trained male Tsimane research assistant (RA) in five villages (two downriver Maniqui villages [in 2007]; one near road [2010]; and two upriver Maniqui [2011]) varying in proximity to the market town of San Borja. Participants from each village were familiar with JS because he resided there for several weeks or months prior to collecting IPV data. JS’s Tsimane RA was not a resident of any sampled village, was not particularly well-known to participants, had prior experience conducting sensitive interviews (e.g. on conflict with non-kin) as part of the Tsimane Health and Life History Project (THLHP), and was trained by JS in scientific research ethics. Women were queried about IPV as part of a broader interview on kin cooperation and conflict, in which women’s current husbands also participated. Interviews were translated into Tsimane from Spanish, and then back-translated into Spanish from Tsimane with assistance of two bilingual Tsimane RAs that were part of the THLHP but otherwise unaffiliated with this study. Translation inconsistencies were resolved by JS and the three Tsimane RAs, and the interview was piloted for three months in one village in 2007 as additional refinements were made by JS and his RA. Interviews were conducted privately in JS’s field house to ensure confidentiality, and in the Tsimane language to increase participants’ comfort levels. To ensure participant safety and confidentiality, only one eligible woman was randomly selected per household for interview. To further ensure confidentiality and given the lack of local violence reporting laws, we did not report any violent incidents. Participant compensation included desirable store-bought items such as soap for washing clothes, sugar, cooking oil, fishhooks, yarn for weaving, or rifle bullets or shotgun shells for hunting.

The IPV sample includes all individuals who met the inclusion criteria of self-identifying as Tsimane and female, who married at least once, who only married monogamously, and who reported no use of modern birth control. Once IPV sample eligibility was determined, households were selected randomly within villages; <10% of women refused to participate in the IPV interview. Women ranged between 15–77 years of age at the time of IPV assessment. Mean ± SD age at first marriage for women and their husbands is 16.7 ± 3.0 yrs (n=105) and 20.5 ± 4.2 (n=133), respectively (for additional descriptive statistics see Supplementary Tables 1 [wives] and 2 [husbands]). Twenty-six of 105 wives (25%) remarried (n=28 marriages since two women remarried twice), usually because of divorce (21/28, 75% of remarriages) rather than a first husband’s death (7/28, 25%); divorce was most common in the first year of marriage (29% of divorces), and 76% of divorces occurred in the first three years. For women who divorced, there is no significant difference in IPV prevalence or annual IPV rate for first versus subsequent marriages.

A retrospective design for IPV assessment was used for several reasons: i) to estimate women’s total IPV exposure during the sample period (i.e. not just in the past year but in all years of marriage prior to menopause); ii) to examine intra-individual change in IPV exposure over time (e.g. across births within marriage, across marriages); and iii) to balance gains in statistical power from repeated measures on the same woman and logistical constraints of increasing sample size. We first elicited women’s complete reproductive histories to construct multiple temporal intervals per woman (e.g. pregnancies, periods from a given birth until weaning), to which we could assign to each interval a chronological year (hereafter marital risk year) using existing THLHP demographic data (range: 2–35 marital risk years for 105 women; a detailed description of demography data collection methods is provided elsewhere47). Aside from pregnancies and periods from a given birth until weaning, another type of temporal interval for which we assigned chronological years included the period of spousal co-residence prior to the first pregnancy in marriage (usually encompassing only one risk year). Additional types of intervals assigned chronological years included the year prior to the IPV interview (i.e. for reproductive-aged women who were neither pregnant nor lactating since at least two years [max=21 years] prior to the interview), the period following a miscarriage until either the next pregnancy or the following year (the latter for women who were post-menopausal at the time of interview and whose final pregnancy resulted in miscarriage), and if applicable, the year prior to menopause (last interval). While interval duration is not chronologically uniform and does not span exactly one year, the Tsimane – who have no written language or time-keeping technology of their own – do not appeal to calendar dates to recall timing of past events, but instead appeal to salient reference periods comprising major life history events (e.g. births or deaths). The derived temporal intervals provided women with these salient reference periods, during which they recalled IPV exposure, and during which we assigned relevant time-varying or invariant covariates. For intervals including pregnancies, women were asked whether IPV occurred before or during pregnancy; while most abusive episodes were reported before pregnancy, IPV may be under-reported during the first trimester. Because a major goal of this study is to test whether IPV increases marital fertility, intervals analyzed here only span marital years in which a wife is at risk of birth (wife’s age range: 11–45 years); for post-menopausal interviewees (23% of interviewees, contributing 37% of marital risk years [704/1,905]), age is capped at 45 years during their last interval (i.e. no risk years beyond age 45 are included in analyses, nor are they included in the 1,905 marital risk years). In total, 1,165/1,905 risk years (61%) did not include pregnancy and the remaining 39% (740/1,905) included pregnancy.

To ascertain IPV, we asked women during each interval, whether they were ever intentionally physically hurt by their husband, e.g. from being punched, slapped, kicked or in other ways mentioned in the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales48 (e.g. pushed, grabbed, choked, burned, bitten, hit with an object). While women reported various ways in which they experienced IPV, we did not systematically distinguish among them with separate questions because there was no compelling theoretical reason to do so, and because this would have greatly lengthened the interview (which already took 1–2 hours). Thus, during each interval (e.g. “From the time that you first realized that you were pregnant with baby X, until you gave birth to baby X…”), women were asked whether, and the number of times they experienced any physical IPV. From these retrospective data we were able to calculate, for each woman in a given year of a given marriage, both the cumulative frequency and the cumulative relative frequency of IPV (see Figure 1); the latter was done by computing a running total - across all years of a marriage - of the number of abusive episodes/year, and then for each year dividing that running total by the total number of abusive episodes in a marriage.

Couple-level data (i.e. reports from spouses from the same marriage) collected in a sub-sample of 21 couples from one village in 2010 reveal substantial spousal consistency in reporting both whether physical IPV occurred in the year prior to the IPV interview (Fisher’s Exact p=0.028), and the number of IPV incidents that same year40. Verbal spousal aggression, including threats of physical IPV, was often reported, but we excluded this from our IPV definition to focus on more salient behaviors exhibiting greater gender inequality49. We did not inquire about sexual IPV to minimize study intrusiveness and risk of further traumatization.

Reproductive histories were elicited among women and men by MG, JS and Tsimane research assistants, and updated by THLHP physicians and their translators during annual medical exams. Birth years were assigned based on a combination of methods described elsewhere47. IBI refers to the number of months between live births for women with ≥2 live births.

Height and weight were measured during THLHP medical exams using a Seca stadiometer (Road Rod 214) and Tanita scale (BF680). Schooling and Spanish fluency were assessed during annual THLHP census updates.

As part of a broader interview on kin cooperation and conflict, female participants and their husbands in three villages reported the frequency with which they witnessed and experienced physical violence during childhood, as perpetrated by co-resident male and female household heads (usually biological parents). Respondents used a five-point scale (1=never, 5=always) for three items regarding frequency of a father’s physical aggression toward: i) his spouse; ii) ego; and iii) ego’s siblings, and three items regarding frequency of a mother’s physical aggression toward: i) her spouse; ii) ego; and iii) ego’s siblings (see Supplementary Tables 8 and 10 for item descriptives).

Five items were used to assess men’s attitudes toward intersexual control. Using a five-point scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree), husbands in three villages indicated their beliefs about whether: i-ii) they can solely decide when their wife visits other houses, and when spousal intimacy occurs; iii) their wife should comply with their request regardless of her own preferences; iv) their wife should respect their demand that she stop talking; and v) they should be unrelenting sexually toward their wife (see Supplementary Tables 8 and 11 for item descriptives).

Three items were used to assess men’s attitudes toward intrasexual physical aggression. Using the same five-point scale, husbands in three villages indicated their beliefs about whether: i) it is vital for them to know how to physically fight another man; ii) they should hit another man if that other man hits them first; and iii) use of physical force is more vital than intellect to resolve conflicts between men (see Supplementary Tables 8 and 12 for item descriptives). To assess external validity, we compared intrasexual aggression component scores (from principal components analysis, see next paragraph) for men who reported engaging in a physical altercation with another man in the past year (18% of men) vs. men who reported no such altercation (82%). As expected if men’s reported attitudes toward intrasexual physical aggression reflect actual aggression toward other men, men who reported an altercation have higher intrasexual aggression component scores (mean ± SD = 1.19 ± 0.96) vs. men who reported no altercation (−0.26 ± 0.81; Mann-Whitney U p<0.001, n=50).

Mann-Whitney U and χ2 tests were used to compare spousal characteristics by whether a wife experienced IPV (Supplementary Tables 1–2). Principal components analyses (PCA) were used to quantify men’s attitudes toward intersexual control and intrasexual aggression, and men’s and women’s degree of childhood exposure to physical violence (see Supplementary Tables 8–13 for item, composite and PCA descriptives). In total, six PCAs yielded six components: ego’s father’s aggression (73% variance explained for the husband, 62% for the wife), ego’s mother’s aggression (67% for the husband, 58% for the wife), a husband’s intersexual control (52%), and a husband’s intrasexual aggression (57%). Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) analyses are used to model effects of predictors on fertility and IPV rates. The GEE method accounts for the correlated structure of a dependent variable arising from repeated measures on the same individual over time, controlling for each individual. There is no standard absolute goodness-of-fit measure with the GEE method50, which does not make distributional assumptions and uses a quasi-likelihood rather than full likelihood estimation approach. A stepwise approach is used to fit GEE models; starting from a reduced model that included primary predictors, covariates were added sequentially and retained until all predictors were significant at p≤0.1. Village dummies were also included as fixed effects in all regressions, to account for potential village-level differences in fertility or reporting IPV. We compared GEE model estimates to those obtained from generalized linear mixed models fit by maximum likelihood but no major differences were found. GEE parameter estimates are reported as odds ratios or predicted probabilities. We used a related-samples Wilcoxon Signed Rank test to test whether any IPV experience with a husband is associated with greater annual fertility with that husband within women across marriages; to provide variance estimates of annual fertility we used bootstrap resampling to derive 95% confidence intervals (Figure 3). Participants with missing data were removed from analyses.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

GEE analysis of the effect of IPV on the probability of birth/year (including time period dummies and other controls [model 1], and omitting the most recent time period, 2003–2012 [model 2]).

| (1) All wives (n=1,905 marital years, 105 wives) |

(2) Omit most recent time period (n=1,249 marital years, 80 wives) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Exp(B) | 95% CI | P | Exp(B) | 95% CI | P |

| Experience IPV that year (vs. not) | 0.500 | 0.273–0.917 | 0.025 | 0.355 | 0.152–0.828 | 0.017 |

| Wife age (years) | 1.092 | 1.020–1.168 | 0.011 | 1.096 | 1.009–1.189 | 0.029 |

| Experience IPV that year*Wife age | 1.035 | 1.012–1.059 | 0.003 | 1.055 | 1.020–1.092 | 0.002 |

| Wife age2 (years) | 0.998 | 0.997–0.999 | <0.001 | 0.998 | 0.996–0.999 | 0.001 |

| Wife any schooling (vs. none) | 0.758 | 0.618–0.928 | 0.007 | 0.764 | 0.592–0.985 | 0.038 |

| Wife Spanish fluent (vs. none) | 0.296 | 0.117–0.748 | 0.010 | 0.179 | 0.055–0.581 | 0.004 |

| Wife Spanish fluent*Wife age | 1.065 | 1.028–1.104 | 0.001 | 1.084 | 1.041–1.130 | <0.001 |

| Wife weight (kg)^ | 1.010 | 1.000–1.020 | 0.050 | 1.016 | 1.004–1.028 | 0.009 |

| Period=2003–2012 (vs. pre-1992) | 1.287 | 1.024–1.619 | 0.031 | ----- | ----- | ----- |

| Period=1992–2002 (vs. pre-1992) | 1.207 | 0.974–1.495 | 0.085 | 1.144 | 0.915–1.431 | 0.238 |

| Village 1 (vs. others) | 1.047 | 0.812–1.351 | 0.722 | 1.107 | 0.804–1.524 | 0.533 |

| Village 2 (vs. others) | 1.094 | 0.866–1.382 | 0.452 | 1.229 | 0.870–1.738 | 0.242 |

| Village 3 (vs. others) | 0.823 | 0.474–1.430 | 0.489 | 0.897 | 0.485–1.658 | 0.729 |

| Village 4 (vs. others) | 1.182 | 0.904–1.544 | 0.221 | 1.210 | 0.789–1.857 | 0.383 |

| Village 5 (vs. others) | 1 | ----- | ----- | 1 | ----- | ----- |

Year of anthropometry data collection is also controlled (not significant in either model).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank study participants for sharing personal stories, and THLHP personnel for assistance with logistics, data collection and coding. We also thank Paul Seabright and participants in the “Harmful Practices” workshop at UCSB in March 2018 for useful discussions that improved the quality of this manuscript. Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation (BCS-0721237; BCS-0422690), National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (R01AG024119), and the Latin American and Iberian Institute at the University of New Mexico. JS also acknowledges financial support from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR)—Labex IAST. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Supplementary information (i.e. tables and figures) is included as an electronic attachment.

Data availability.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breiding M, Basile K, Smith S, Black M & Mahendra R Intimate partner violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements, version 2.0. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levinson D Family Violence in Cross-Cultural Perspective. (Sage, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Counts D, Brown J & Campbell J To have and to hit: Cultural perspectives on wife beating. 2nd edn, (University of Illinois Press, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shakya HB et al. Longitudinal associations of intimate partner violence attitudes and perpetration: Dyadic couples data from a randomized controlled trial in rural India. Social science & medicine (1982) 179, 97–105, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.032(2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell J Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 359, 1331–1336 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heise L, Raikes A, Watts C & Zwi A Violence against Women: A neglected public health issue in less developed countries. Social Science and Medicine 39, 1165–1179 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy C, Schei B, Myhr T & Du M Abuse: a risk factor for low birth weight? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal 164, 1567–1572 (2001). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buss D From vigilance to violence: Tactics of mate retention in American undergraduates. Ethology and Sociobiology 9, 291–317 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson M, Johnson H & Daly M Lethal and nonlethal violence against wives. Canadian Journal of Criminology 37, 331–362 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloch F & Rao V Terror as a bargaining instrument: A case study of dowry violence in rural India. The American Economic Review 92, 1029–1043 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macmillan R & Gartner R When She Brings Home the Bacon: Labor-Force Participation and the Risk of Spousal Violence against Women. Journal of Marriage and Family 61, 947–958, doi: 10.2307/354015 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobash R & Dobash R Violence against wives: A case against the patriarchy. (Free Press, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yllö K The status of women, marital equality, and violence against wives: A contextual analysis. Journal of Family Issues 5, 307–320 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehrensaft MK, Moffitt TE & Caspi A Clinically abusive relationships in an unselected birth cohort: men’s and women’s participation and developmental antecedents. Journal of abnormal psychology 113, 258–270, doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.113.2.258 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Archer J Cross-cultural differences in physical aggression between partners: a social-role analysis. Personality and social psychology review : an official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc 10, 133–153, doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_3 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stith SM et al. The Intergenerational Transmission of Spouse Abuse: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family 62, 640–654, doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00640.x (2000). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daly M, Wilson M & Weghorst SJ Male sexual jealousy. Ethology and Sociobiology 3, 11–27 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daly M & Wilson M Homicide. (Aldine de Gruyter, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burch R & Gallup G Jr. Perceptions of paternal resemblance predict family violence. Evolution and Human Behavior 21, 429–435 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Figueredo A & McCloskey L Sex, money, and paternity: The evolutionary psychology of domestic violence. Ethology and Sociobiology 14, 353–379 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shackelford T, Goetz A, Buss D, Euler H & Hoier S When we hurt the ones we love: Predicting violence against women from men’s mate retention. Personal Relationships 12, 447–463 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stieglitz J, Kaplan H, Gurven M, Winking J & Vie Tayo B Spousal violence and paternal disinvestment among Tsimane’ forager-horticulturalists. American Journal of Human Biology 23, 445–457 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flinn M Mate guarding in a Caribbean village. Ethology and Sociobiology 9, 1–28 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson M & Daly M An evolutionary psychological perspective on male sexual proprietariness and violence against wives. Violence and Victims 8, 271–294 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borgerhoff Mulder M & Rauch K Sexual conflict in humans: Variations and solutions. Evolutionary Anthropology 18, 201–214 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holland Jones J & Ferguson B Demographic and social predictors of intimate partner violence in Colombia: A dyadic perspective. Human Nature 20, 184–203 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smuts B & Smuts R Male Aggression and Sexual Coercion of Females in Nonhuman Primates and Other Mammals: Evidence and Theoretical Implications. Advances in the Study of Behavior 22, 1–63 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baniel A, Cowlishaw G & Huchard E Male Violence and Sexual Intimidation in a Wild Primate Society. Current Biology 27, 2163–2168. e2163 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clutton-Brock T & Parker G Sexual coercion in animal societies. Animal Behaviour 49, 1345–1365 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller M, Kahlenberg S & Wrangham R in Sexual Coercion in Primates and Humans: An Evolutionary Perspective on Male Aggression Against Females (eds Muller M& Wrangham R) 244–294 (Harvard University Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knott C & Kahlenberg S in Primates in Perspective (eds Bearder S et al.) 290–305 (Oxford University Press, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feldblum JT et al. Sexually coercive male chimpanzees sire more offspring. Current biology : CB 24, 2855–2860, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.039 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mcallister L, Gurven M, Kaplan H & Stieglitz J Why do women have more children than they want? Understanding differences in women’s ideal and actual family size in a natural fertility population. American Journal of Human Biology 24, 786–799 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finkel EJ, DeWall CN, Slotter EB, Oaten M & Foshee VA Self-regulatory failure and intimate partner violence perpetration. J Pers Soc Psychol 97, 483–499, doi: 10.1037/a0015433 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bushman BJ, DeWall CN, Pond RS & Hanus MD Low glucose relates to greater aggression in married couples. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 6254–6257, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400619111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Von Rueden C, Gurven M & Kaplan H Why do men seek status? Fitness payoffs to dominance and prestige. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278, 2223–2232 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jewkes R Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. Lancet 359, 1423–1429, doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08357-5 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melzer SA Gender, work, and intimate violence: Men’s occupational violence spillover and compensatory violence. Journal of Marriage and Family 64, 820–832 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parker GA Sexual conflict over mating and fertilization: an overview. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 361, 235–259, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1785 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stieglitz J, Gurven M, Kaplan H & Winking J Infidelity, jealousy, and wife abuse among Tsimane forager–farmers: testing evolutionary hypotheses of marital conflict. Evolution and Human Behavior 33, 438–448 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lalumière ML & Quinsey VL Sexual deviance, antisociality, mating effort, and the use of sexually coercive behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences 21, 33–48, doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(96)00059-1 (1996). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rice WR & Holland B The enemies within: intergenomic conflict, interlocus contest evolution (ICE), and the intraspecific Red Queen. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 41, 1–10, doi: 10.1007/s002650050357 (1997). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker G in Sexual selection and reproductive competition in insects (eds Blum M & Blum N) 123–166 (Academic Press, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emery Thompson M & Alvarado L in The Oxford Handbook of Sexual Conflict in Humans (eds Shackelford T& Goetz A) 100–121 (Oxford University Press, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gurven M, Winking J, Kaplan H, Von Rueden C & McAllister L A bioeconomic approach to marriage and the sexual division of labor. Human Nature 20, 151–183 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blackwell AD et al. Helminth infection, fecundity, and age of first pregnancy in women. Science 350, 970–972 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gurven M, Kaplan H & Zelada Supa A Mortality experience of Tsimane Amerindians of Bolivia: Regional variation and temporal trends. American Journal of Human Biology 19, 376–398 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy SUE & Sugarman DB The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2). Journal of Family Issues 17, 283–316, doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001 (1996). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen H, Ellsberg M, Heise L & Watts C Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet 368, 1260–1269 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan W Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics 57, 120–125 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.