Abstract

Repression of germline-promoting genes in somatic cells is critical for somatic development and function. To study how germline genes are repressed in somatic tissues, we analyzed key histone modifications in three Caenorhabditis elegans synMuv B mutants, lin-15B, lin-35, and lin-37—all of which display ectopic expression of germline genes in the soma. LIN-35 and LIN-37 are members of the conserved DREAM complex. LIN-15B has been proposed to work with the DREAM complex but has not been shown biochemically to be a member of the complex. We found that, in wild-type worms, synMuv B target genes and germline genes are enriched for the repressive histone modification dimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 9 (H3K9me2) at their promoters. Genes with H3K9me2 promoter localization are evenly distributed across the autosomes, not biased toward autosomal arms, as are the broad H3K9me2 domains. Both synMuv B targets and germline genes display a dramatic reduction of H3K9me2 promoter localization in lin-15B mutants, but much weaker reduction in lin-35 and lin-37 mutants. This difference between lin-15B and DREAM complex mutants likely represents a difference in molecular function for these synMuv B proteins. In support of the pivotal role of H3K9me2 in regulation of germline genes by LIN-15B, global loss of H3K9me2 but not H3K9me3 results in phenotypes similar to synMuv B mutants, high-temperature larval arrest, and ectopic expression of germline genes in the soma. We propose that LIN-15B-driven enrichment of H3K9me2 at promoters of germline genes contributes to repression of those genes in somatic tissues.

Keywords: H3K9me2, synMuv B, LIN-15B, germline genes, chromatin

REPRESSION in somatic cells of genes that promote germline development and function is a vital cell fate regulatory mechanism, which, when disrupted, leads to developmental problems and is a hallmark of aggressive cancer (Janic et al. 2010; Petrella et al. 2011; Whitehurst 2014; Al-Amin et al. 2016). Repression of germline genes in the soma poses a unique challenge for cells. First, like other genes expressed in specific tissues, germline genes can be found clustered along chromosomes; however, within a given cluster, genes with ubiquitous, germline, and nongermline expression are interspersed (Roy et al. 2002; Spellman and Rubin 2002; Reinke and Cutter 2009). Therefore, somatic cells require a mechanism to repress germline genes without disrupting expression of important flanking genes. Second, because embryos start life as the fusion of two germline cells—an egg and a sperm—they inherit an epigenetic state associated with driving germline gene expression (Furuhashi et al. 2010; Rechtsteiner et al. 2010; Zenk et al. 2017; Kreher et al. 2018; Tabuchi et al. 2018). This chromatin state must be reset during development to turn off germline gene expression in differentiating somatic cells (Morgan et al. 2005; Fraser and Lin 2016). There has been no investigation to date of the unique patterns of chromatin modifications or regulatory protein binding that lead to repression of germline genes in somatic tissues in Caenorhabditis elegans.

synMuv (for synthetic Multivulva) B proteins are a diverse class of transcriptional repressors that are involved in a number of different cell fate decisions in C. elegans (Unhavaithaya et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2005; Fay and Yochem 2007). A subset of synMuv B genes show a distinct set of mutant phenotypes, which include ectopic expression of germline genes in somatic cells and larval arrest at high temperature (called HTA for high temperature arrest) (Wang et al. 2005; Petrella et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2012). Of this subset, a large proportion encode proteins that exist in two complexes: the HP1-containing heterochromatin complex (HPL-2, LIN-13, LIN-61), and the DREAM complex (EFL-1, DPL-1, LIN-35, LIN-9, LIN-37, LIN-52, LIN-53, LIN-54) (Coustham et al. 2006; Harrison et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2012). Several additional synMuv B mutants, including lin-15B and met-2, also display ectopic germline gene expression in the soma, but have not been shown biochemically to encode members of the HP1 or DREAM complex (Petrella et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2012). lin-15B mutants, like mutants in genes encoding DREAM complex members, also display an HTA phenotype, show changes in regulation of somatic RNAi, and cause transgene silencing in the soma (Wang et al. 2005; Petrella et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2012). While mutations in genes encoding the HP1 complex, the DREAM complex, LIN-15B, and MET-2 all lead to ectopic expression of germline genes in the soma, the precise way these different complexes/proteins function in parallel or together to repress germline genes in the somatic tissues of wild-type animals is not understood.

Several lines of evidence point to synMuv B complexes repressing gene expression by altering chromatin. First, synMuv B mutant phenotypes, including HTA and ectopic germline gene expression, are strongly suppressed by loss of chromatin factors (Unhavaithaya et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2005; Cui et al. 2006; Petrella et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2012). Second, the DREAM complex has been shown to promote enrichment of the H2A histone variant HTZ-1 in the body of a subset of genes that the DREAM complex represses in L3 larvae (Latorre et al. 2015). Finally, HPL-2 is a homolog of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) (Couteau et al. 2002). HPL-2, in a complex with LIN-13 and LIN-61, localizes to genomic regions enriched for histone H3 methylated at lysine 9 (H3K9me) and helps create repressive heterochromatin (Wu et al. 2012; Garrigues et al. 2015). Together, these data indicate that changes to chromatin may underlie the ectopic expression of germline genes in synMuv B mutants.

One of the best studied aspects of chromatin regulation is covalent modifications on histone tails. Specific histone modifications are often associated with repressive or active chromatin compartments and can be a read-out of the expression state of a gene. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation (H3K4me) and H3 lysine 36 methylation (H3K36me) are generally associated with areas of previous or active gene expression (Ho et al. 2014; Evans et al. 2016). In contrast, histone H3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me) and histone H3 lysine 27 methylation (H3K27me) are associated with areas of low/no expression of coding genes and repression of repetitive elements (Ahringer and Gasser 2018). Of particular interest for the regulation of germline gene expression in somatic cells is histone H3K9 methylation. In C. elegans, mono- and dimethylation of H3K9 (H3K9me1 and H3K9me2, respectively), are primarily catalyzed by MET-2. met-2 mutants lose 80–90% of H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 in embryos (Towbin et al. 2012). met-2 is a synMuv B gene, and mutants have been previously shown to ectopically express germline genes in somatic cells (Wu et al. 2012). Trimethlyation of H3K9 (H3K9me3) is catalyzed by a separate histone methyltransferase, SET-25 (Towbin et al. 2012). set-25 is not a synMuv B gene and its potential role in regulating germline gene expression in the soma has not been tested. Several studies have analyzed the roles in C. elegans of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 in regulating the interaction of heterochromatin with the nuclear periphery and repression of repetitive elements (Meister et al. 2010; Towbin et al. 2012; Guo et al. 2015; Zeller et al. 2016). Both of these functions rely primarily on high enrichment of H3K9 methylation on the heterochromatic arms of the autosomes (Ikegami et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2011; Garrigues et al. 2015; Evans et al. 2016). However, little work has been done to look at how H3K9 methylation localizes to or regulates protein-coding genes in the euchromatic central regions of autosomes, where a large percentage of germline genes reside. To fill this gap, we sought to identify changes in the levels and distributions of active and repressive histone modifications in the soma of synMuv B mutants and test whether such changes underlie ectopic expression of germline genes.

In this study, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation with genome-wide high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) to analyze histone modifications in wild type and three synMuv B mutants, lin-15B, lin-35, and lin-37. We found that, in wild-type L1 larvae, which are composed of 550 somatic cells and two germ cells, and are therefore primarily somatic, H3K9me2 is enriched at the promoters of a subset of genes that display germline-specific expression. The genes that have H3K9me2 at their promoters in wild type are generally upregulated in synMuv B mutants, suggesting that H3K9me2 plays a role in their repression. In support of this, the localization of H3K9me2 at gene promoters is largely lost in lin-15B mutants and is diminished but not lost in lin-35 and lin-37 mutants. Loss of H3K9me2 at promoters in mutants is associated with an increase in H3K4me3 at promoters and H3K36me3 in gene bodies—modifications associated with gene expression—suggesting that these genes go from a repressed state to an expressed state. Global loss of H3K9me2 but not H3K9me3 results in both the HTA and ectopic germline gene expression phenotypes seen in lin-15B mutants. We propose that LIN-15B and DREAM repress a subset of germline genes in somatic tissues by promoting enrichment of H3K9me2 at the promoters of those genes.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans strains and culture conditions

C. elegans were cultured using standard conditions (Brenner 1974) at 20° unless otherwise noted. N2 (Bristol) was used as wild type. Mutant strains were as follows:

ChIP-seq from L1s

Worms were grown from synchronized L1s in standard S-basal medium with shaking at 230 rpm and fed HB101 bacteria until gravid. Embryos were harvested using standard bleaching methods, and L1s were synchronized in S-basal medium with shaking for 14–18 hr in the absence of food. For 26° samples, worms were grown to the L4 stage at 20°, then upshifted to 26° until gravid, and L1s were harvested as described above. Extracts were made as described in Kolasinska-Zwierz et al. (2009) with the following modifications. Cross-linked chromatin was sonicated using a Diagenode Bioruptor at high setting for 30 pulses, each lasting 30 sec followed by a 1 min pause. ChIP was performed as described by Kolasinska-Zwierz et al. (2009) with the modification of using 0.5 mg of protein and 1 µg antibody or by using an IP-Star Compact Automated System (Diagenode) as described in Tabuchi et al. (2018). Sequencing libraries were prepared in two ways. Some libraries were prepared with the NEBNext Ultra DNA library Prep Kit (NEB) following the manufacturers’ instructions; 1 ng of starting DNA was used, adapters were diluted 1:40, and AMPure beads were used for size selection before amplification to enrich for fragments corresponding to a 200 bp insert size. The other libraries were prepared using Illumina Truseq adapters and primers. ChIP or input DNA fragments were end-repaired with the following: 5 µl T4 DNA ligase buffer with 10 mM ATP, 2 µl dNTP mix, 1.2 µl T4 DNA polymerase (3 U/µl), 0.8 µl 1:5 Klenow DNA polymerase (diluted with 1× T4 DNA ligase buffer for a final Klenow concentration of 1 U/µl), 1 µl T4 PNK (10 U/µl). This 50 µl reaction was incubated at 20° for 30 min and purified with a QIAquick PCR spin column (elution volume 36 µl). “A” bases were then added to the 3′ end of the DNA fragments with the following: 5 µl NEB buffer 2, 10 µl dATP (1 mM), 1 µl Klenow 3′ to 5′ exo- (5 U/µl). This mixture was incubated at 37° for 30 min, and the DNA was purified with a QIAquick MinElute column (11 µl of DNA was eluted into a siliconized tube). Illumina TruSeq adapters were ligated to DNA fragments with the following: 15 µl 2× Rapid Ligation buffer, 1 µl adapters (diluted 1:40), 1.5 µl Quick T4 DNA Ligase. This 30 µl reaction was incubated at 23° for 30 min. The mixture was then cleaned up 2× with AMPure beads (using 95% vol beads), and DNA was eluted in 22 µl. The Adapter-Modified DNA fragments were amplified by PCR with the following mixture: 6 µl 5× Phusion Buffer HF, 2 µl Primer cocktail (from TrueSeq kit), 0.5 µl 25 mM dNTP mix, 0.5 Phusion polymerase (2 U/µl) using the following PCR program: 98° 30 min, 98° 10 min, 60° 30 min, and 72° 30 min repeated 16 cycles, followed by 72° 5 min. The amplified DNA was concentrated and loaded onto a 2% agarose gel, and DNA between 250 and 350 bp was recovered from the gel. The multiplexed libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq4000 or HiSeq2000 at the Vincent J. Coates Genomics Sequencing Laboratory at University of California, Berkeley.

ChIP-chip from embryos

Late-stage embryos were obtained and chromatin extracts prepared as described in Latorre et al. (2015). Chromatin immunoprecipitation and subsequent LM-PCR, microarray hybridization, and scanning were performed as in Garrigues et al. (2015).

Antibodies used for ChIP

Mouse monoclonal antibodies for H3K9me2 (MABI0307, #302–32369; Fujifilm Wako), H3K36me3 (MABI0333, #300–95289; Fujifilm Wako), H3K27me3 (MABI0323, #309–95259; Fujifilm Wako), and H3K4me3 (MABI0304, #305–34819; Fujifilm Wako) were used as described in Liu et al. (2011), Egelhofer et al. (2011). Rabbit polyclonal LIN-15B antibody (SDQ2330, #38610002; Novus Biologicals) was used at a concentration of 2.5 µg per milligram of chromatin extract.

Analysis of ChIP-seq data

Raw sequence reads from the Illumina HiSeq (50 bp single-end reads) were mapped to the C. elegans genome (Wormbase version WS220) using Bowtie with default settings (Langmead et al. 2009). MACS2 (Zhang et al. 2008) was used to call peaks and create bedgraph files for sequenced and mapped H3K4me3 ChIP samples and corresponding Input DNA samples with the following parameters: callpeak -t H3K4me3.mapped.reads.sampleX -c Input.mapped.reads.sampleX -g ce --bdg --keep-dup=auto --qvalue=0.01 --nomodel --extsize=250 --call-summits

MACS2 was used to call peaks and create bedgraph files for sequenced and mapped H3K9me2 ChIP samples and corresponding Input DNA samples with slightly different parameters to account for the broader domains of H3K9me2: callpeak -t H3K9me2.mapped.reads.sampleX -c Input.mapped.reads.sampleX --g ce --bdg --keep-dup=auto --broad --broad-cutoff=0.01 --nomodel --extsize=250. Replicate 1 of H3K9me2 in lin-15B at 20° had significantly fewer peaks than replicate 2, so we relaxed the peak call significance cutoff to --broad-cutoff=0.05 for replicate 1. This makes our reported results of H3K9me2 peak loss in lin-15B compared to N2 a conservative estimate, as peaks were called with the more stringent cutoff for both replicates of N2. A peak was considered to be associated with a gene’s promoter if it overlapped at least 100 bp with the region 750 bp upstream from the gene’s transcript start site (TSS) to 250 bp downstream from the TSS. A peak was considered to be associated with the body of a gene if it overlapped at least 250 bp with the region from 250 bp downstream from the TSS to the TES (transcript end site). A gene’s promoter or gene body was considered bound by H3K4me3 or H3K9me2 in one of the conditions if, for all replicates of that condition, a peak was associated with the gene’s promoter or body, respectively. Whenever we refer to genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak, we mean genes that have an H3K9me2 peak solely at their promoter and not also in their gene body. The distribution of genes with promoter or gene body H3K9me2 peaks along an autosome are shown in Figure 3A in 200 kb windows.

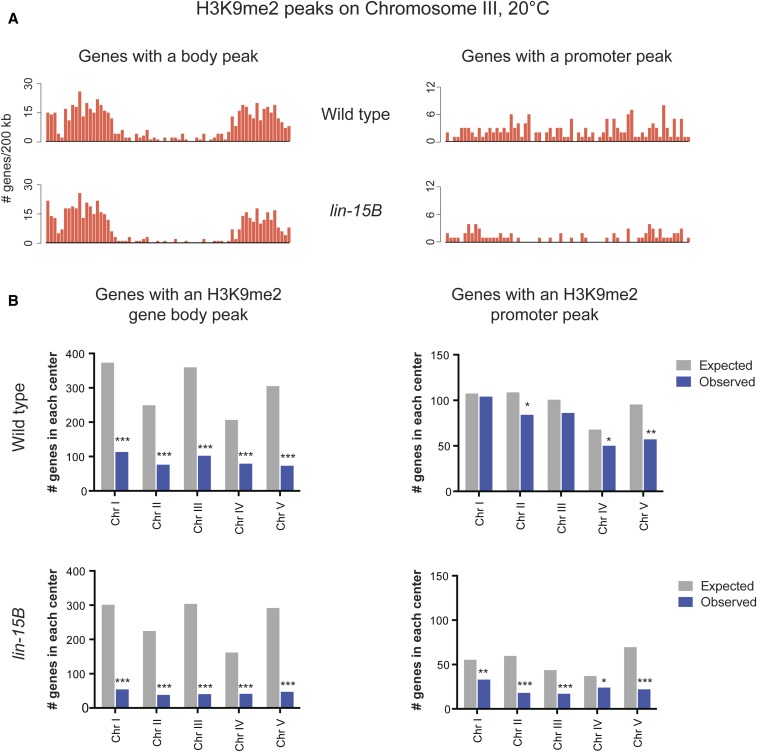

Figure 3.

Genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak in wild-type L1s are not biased toward autosomal arms. (A) Binned distribution of genes with an H3K9me2 gene body or promoter peak at 20° in 200 kb windows across chromosome III in wild-type and lin-15B mutant L1s. (B) Enrichment analysis of genes with an H3K9me2 gene body peak or promoter peak expected by chance and observed in chromosome centers in wild-type and lin-15B mutant L1s. The expected number is based on the percentage of coding genes in the center vs. arm regions of each chromosome; the observed number is the number of genes in the chromosome centers at 20°. The locations of chromosome arm and center boundaries are from Liu et al. (2011). Significant underenrichment (black) was determined by the hypergeometric test (*P-value < 0.01, **P-value < 1 × 10−5, ***P-value < 1 × 10−10).

Bedgraph files for genome browser displays were scaled to 5 million total reads for all H3K4me3 ChIP samples, 10 million reads for all H3K36me3 samples, 15 million reads for all H3K9me2 samples, and 20 million reads for all H3K27me3 samples. The different scaling factors roughly correspond to the different genome-wide coverages of the different ChIP factors, e.g., H3K4me3 being found mostly at promoters of expressed genes, H3K36me3 mostly on gene bodies of expressed genes, and H3K9me2 mostly on chromosomal arms. Further data analysis below was based on these scaled read coverages. Scaled bedgraph files were converted to bigwig using the bedGraphToBigWig UCSC Genome Browser tool (Kent et al. 2010) and displayed on the UCSC Genome Browser.

Analysis of LIN-15B ChIP-chip data

NimbleGen 2.1 M probe tiling arrays (DESIGN_ID = 8258) with 50 bp probes designed against WS170 (ce4) were used. Two independent ChIPs were performed. Amplified samples were labeled and hybridized by the Roche NimbleGen Service Laboratory. ChIP samples were labeled with Cy5 and their input reference with Cy3. For each probe, the intensity from the sample channel was divided by the reference channel and log2 transformed. The enrichment scores for each replicate were calculated by standardizing the log ratios to mean zero and SD one (z-score) and the average z-score across replicates was calculated and displayed in the UCSC Genome Browser (Supplemental Material, Figure S3). Peak calling was performed with the MA2C algorithm (Song et al. 2007) using Nimblegen array design files 080922_modEncode_CE_chip_HX1.pos and 080922_modEncode_CE_chip_HX1.ndf and MA2C parameters METHOD = Robust, C = 2, pvalue = 1e-5, BANDWIDTH = 300, MIN_PROBES = 5, MAX_GAP = 250. The resulting peak calls were associated with gene promoters and bodies as described in the previous section.

Correlation heatmap of samples

The scaled bedgraph files were used to calculate for each sample the average read coverage in 1 kb windows across all autosomes and the X chromosome. The resulting read coverage data were log-transformed and normalized for each ChIP sample by dividing by the SD across all 1 kb windows and subtracting the 25th percentile across all 1 kb windows. For each 1 kb window and condition, the resulting data were averaged across replicates. The data were used to calculate the Pearson Correlation coefficient r between all conditions, once for autosomes and once for the X chromosome. The distance d = 1 − r was calculated, and hierarchical clustering was used with the complete linkage method to cluster the conditions. The results are displayed in a heatmap where the cell coloring indicates r between two conditions (Figure S2). The analysis was performed in R version 3.5.1 (R Core Team 2018).

Metagene plots

Metagene plots for the various ChIP targets and conditions (e.g., Figure 2C, Figure 4A, Figure S7, and Figure S9) were generated by aligning genes of length >1.25 kb at their TSS and TES using WormBase WS220 gene annotations. Regions 1 kb upstream to 1 kb downstream from the TSS and TES were divided into 150 bp windows stepped every 50 bp. The mean read coverage within each of these 150 bp windows was calculated and normalized for each ChIP data set by dividing by the SD across all 150 bp windows and subtracting the 25th percentile across all 150 bp windows. For each 150 bp window, the normalized data were averaged across replicates. A metagene profile for a set of genes was generated by averaging and plotting for each 150 bp window the data across the genes in the set. Light vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals for the mean of each 150 bp window. The analysis was performed in R version 3.5.1.

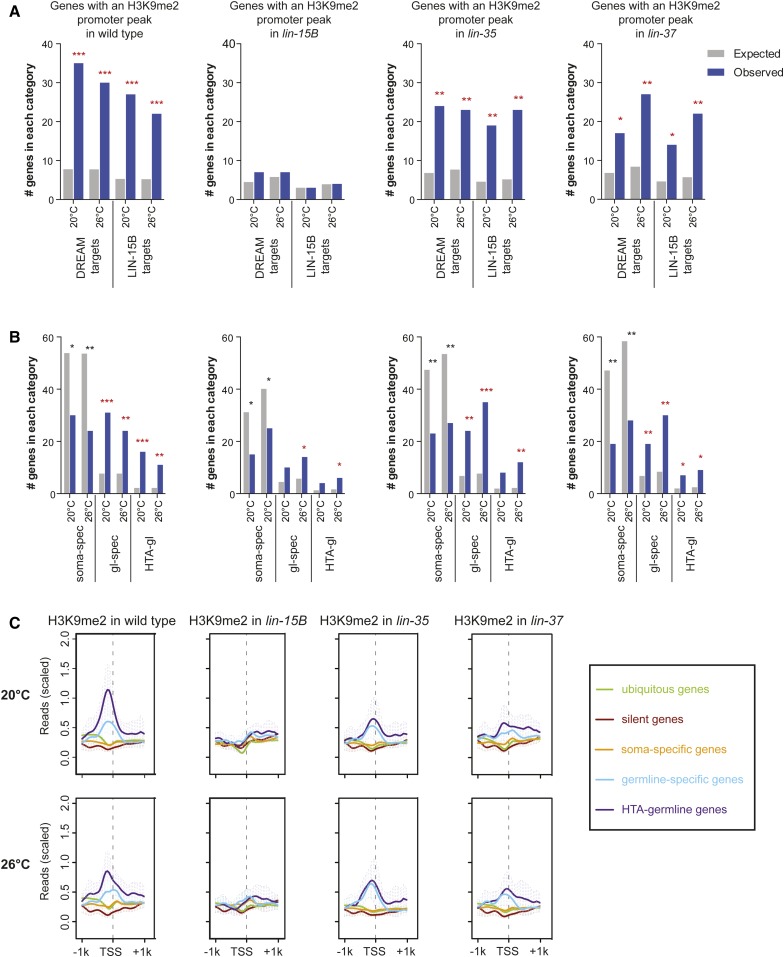

Figure 2.

H3K9me2 promoter peaks are associated with synMuv B targets and germline-specific genes in wild-type L1s. (A) Enrichment analysis of genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak expected by chance and observed among genes that are DREAM complex or LIN-15B targets in the four genotypes indicated. DREAM complex targets are defined as genes that are both bound at their promoter by the DREAM complex (Goetsch et al. 2017) and upregulated in lin-35 mutants at 26° (Petrella et al. 2011). LIN-15B targets are defined as genes that are both bound at their promoter by LIN-15B (this study) and upregulated in lin-15B mutants at 26°. Significant overenrichment (red) or underenrichment (black) was determined by the hypergeometric test (*P-value < 0.01, **P-value < 1 × 10−5, ***P-value < 1 × 10−10). (B) Enrichment analysis of genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak expected and observed among genes that are normally expressed specifically in the soma (soma-spec, 1181 genes), expressed specifically in the germline (gl-spec, 169 genes), and genes in the HTA-germline category (HTA-gl, 48 genes) in the four genotypes indicated (see Materials and Methods for definitions of gene categories). Significant overenrichment (red) or underenrichment (black) was determined by the hypergeometric test (*P-value < 0.01, **P-value < 1 × 10−5, ***P-value < 1 × 10−10). (C) Metagene profiles of mean H3K9me2 ChIP-seq signal 1 kb upstream and downstream from the TSS for the categories of genes analyzed in (B) and also genes that are normally expressed in all tissues (ubiquitous, 2576 genes) and repressed in most tissues (silent, 415 genes). Reads were scaled by dividing by the SD and subtracting the 25th percentile. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for the mean (also see Materials and Methods).

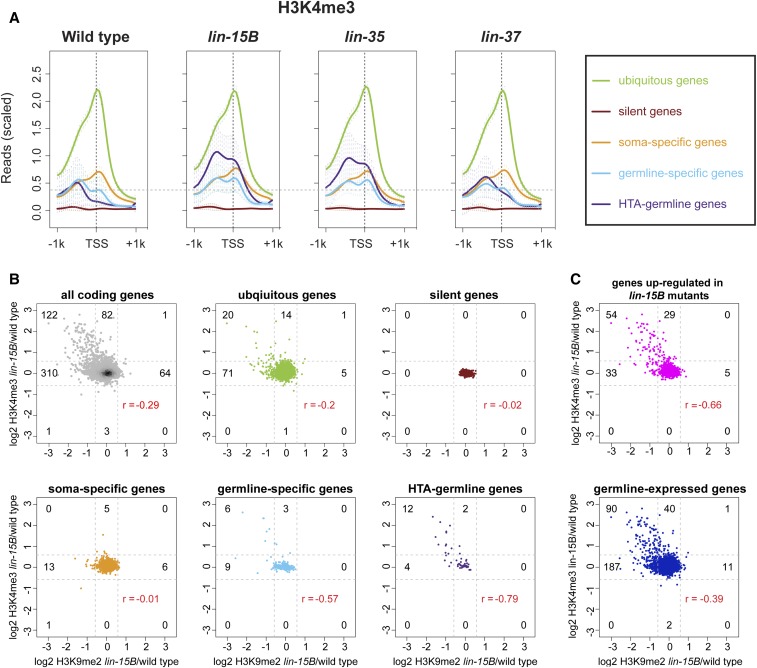

Figure 4.

H3K4me3 increases on germline genes that lose H3K9me2. (A) Metagene profiles of mean H3K4me3 ChIP-seq signal 1 kb upstream and downstream from the TSS for genes that show ubiquitous, silent, soma-specific, germline-specific, or HTA-germline expression at 20° (see Materials and Methods for definitions of gene categories). Horizontal dotted line is located at the highest level of reads over the TSS in wild type for genes in the germline-specific category. Reads were scaled by dividing by the SD and subtracting the 25th percentile. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for the mean. (B and C) Scatter plots of log2 fold change of the H3K9me2 signal over the TSS in lin-15B mutant/wild type vs. log2 fold change of the H3K4me3 signal over the TSS in lin-15B mutant/wild type. The signal was calculated within 250 bp upstream and downstream of the TSS at 20°. (B) All coding genes and genes with ubiquitous, silent, soma-specific, germline-specific, or HTA-germline expression. (C) Genes upregulated in lin-15B mutants and germline-expressed genes. Dotted lines represent 1.5-fold cutoffs; the numbers of genes above and below the cutoffs are indicated. r values show the Pearson correlation between changes in H3K9me2 and changes in H3K4me3 for each set of genes.

Scatterplots

To display scatter plots (Figure 4B, Figure S10, and Figure S11), the mean read coverage for each protein-coding gene was calculated over the region 250 bp upstream and downstream from the TSS. In scatterplots the wild-type log2 normalized read coverage was subtracted from the mutant log2 normalized read coverage for each promoter, resulting in a log2 fold change of mutant over wild-type promoter signal.

Gene set definitions

Ubiquitous genes (2576), originally defined and discussed in Rechtsteiner et al. (2010), are genes that were found to be expressed in germline, muscle, neural, and gut tissues (Meissner et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2009). Germline-enriched genes (2229) are as defined in Reinke et al. (2004). Germline-expressed genes (5373) are defined as genes found to be expressed in the germline based on SAGE (Wang et al. 2009) or genes whose expression was found to be enriched in the germline by microarray (Reinke et al. 2004). Germline-specific genes (169) are genes whose transcripts were found to be expressed exclusively in the adult germline and maternally loaded into embryos; these genes were defined using multiple datasets as described in Rechtsteiner et al. (2010). Soma-specific genes (1181) are genes expressed in at least one of three somatic tissues (muscle, gut, and/or neuron) with at least eight SAGE tags (Meissner et al. 2009), but not enriched (Reinke et al. 2004) or detectably expressed (Wang et al. 2009) in the adult germline. Silent genes are 415 serpentine receptor genes that are expressed in a few mature neurons, and are not detectably expressed in L1 larvae, originally defined in Kolasinska-Zwierz et al. (2009). lin-15B upregulated genes in L1 larvae (1355) and lin-35 upregulated genes in L1 larvae (656) were defined in Petrella et al. (2011). HTA germline genes (48), as defined in Petrella et al. (2011), are genes that were significantly upregulated in lin-35(n745) mutants vs. wild type, and also significantly downregulated in lin-35(n745) mes-4(RNAi) vs. lin-35(n745), and that have germline-enriched expression (Reinke et al. 2004). Whenever P-values are reported for enrichment of gene sets in other categories of genes, we used the hypergeometric test.

HTA larval arrest assays

L4 larvae were placed at 26° for ∼18 hr and then moved to new plates and allowed to lay embryos for 8 hr. Progeny were scored for L1 larval arrest (Petrella et al. 2011).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining of L1 larvae was adapted from Strome and Wood (1983). L4 worms were placed at 26° overnight and then moved into drops of M9 buffer as gravid adults. L1 larvae were obtained by allowing embryos to hatch in the absence of food in the M9 buffer. L1 animals were placed on a polylysine-coated slide, a coverslip was placed over the sample, excess liquid was wicked away, and the slide was immersed in liquid nitrogen for at least 5 min. Slides were removed from liquid nitrogen, the coverslip was removed, and the samples were fixed in methanol at 4° for 10 min and acetone at 4° for 10 min. Slides were air dried, and blocked for 30 min at room temperature. Slides were incubated with anti-PGL-1 primary antibody at 1:30,000 for ∼18 hr at 4° (Kawasaki et al. 1998). Slides were washed two times in PBS for 10 min, blocked for 15 min at room temperature, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) secondary antibody at 1:500 for 2 hr at room temperature. Slides were washed four times for 10 min each in PBS at room temperature and were mounted in Gelutol mounting medium. Images were acquired using a Nikon A1R laser scanning confocal unit controlled by NIS-Elements fitted on a Nikon inverted Eclipse Ti-E microscope with a Nikon DS-Qi1Mc camera and Plan Apo 60X/1.2 numerical aperture oil objective.

Data availability

All strains and noncommercially available reagents are available upon request. All ChIP-seq, ChIP-chip, and expression data are available in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al. 2002) under accession number GSE126884. Supplemental material available at https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.7823846.

Results

lin-15B mutants lose a large proportion of H3K9me2 promoter peaks; lin-35 and lin-37 mutants lose fewer

To better understand how synMuv B proteins regulate germline gene expression in somatic cells, we sought to identify changes in histone modification patterns in mutants compared to wild type. We profiled the distributions of two histone modifications associated with active chromatin (H3K4me3 and H3K36me3), and two histone modifications associated with repressive chromatin (H3K9me2 and H3K27me3) using ChIP-seq. Experiments were done on L1 animals that experienced embryogenesis at 20° or 26° for four genotypes: wild type and three synMuv B mutants: lin-15B(n744), lin-35(n745), and lin-37(n758). Because L1 stage worms have 550 somatic cells and only two germline cells, extracts from L1s contain genomic material primarily from somatic tissues. Analysis of H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 patterns showed increased enrichment of these modifications in mutants compared to wild type on classes of genes that are upregulated in synMuv B mutants (Figure S1, discussed below). As the presence of these modifications generally correlates with gene expression, this change was expected. We saw no changes in the pattern of the repressive modification H3K27me3 between mutants and wild type (Figure S2). However, we observed significant changes in the pattern of the repressive modification H3K9me2 between synMuv B mutants and wild type, especially on germline-expressed genes (Figure 1B). We analyzed the changes to H3K9me2 patterns in detail to investigate whether this particular histone modification is important for repression of germline gene expression by synMuv B proteins.

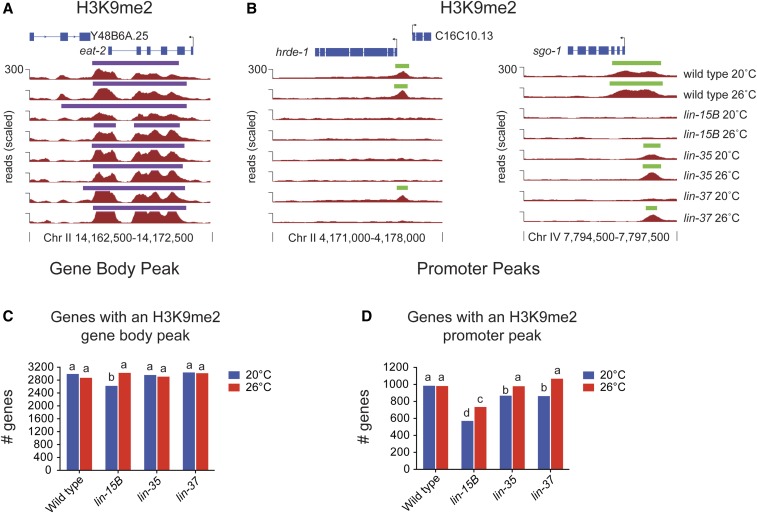

Figure 1.

H3K9me2 promoter peaks are lost in lin-15B mutant L1s. (A and B) H3K9me2 ChIP-seq data visualized on the UCSC genome browser at one gene eat-2 (A) with an H3K9me2 gene body peak (purple) and at two germline-expressed genes hrde-1 and sgo-1 (B) with an H3K9me2 promoter peak (green). The vertical lines and arrows indicate the location of the transcript start site (TSS) and the direction of transcription. Signals shown are ChIP-seq reads scaled to 15 million total reads (see Materials and Methods). (C and D) Number of genes in each genotype with a called H3K9me2 peak in the gene body (C) or at the promoter (D). Genotypes with the statistically same number of genes with a called peak are designated with the same letter (Chi squared P-value < 0.01). Exact P-values can be seen in Tables S2 and S3.

Analysis of H3K9me2 showed that most of the localization of H3K9me2 on autosomes and the X chromosome is unchanged between mutants and wild type (Figure 1A and Figure S2). However, a subset of H3K9me2 peaks were observed to be lost or reduced in synMuv B mutants (Figure 1B). To investigate the pattern of this loss/reduction, we performed peak calling for H3K9me2 and designated two types of peaks depending on the location of H3K9me2 relative to gene bodies. “Gene body peaks” are those peaks where H3K9me2 overlaps with at least a portion of the coding region of the gene that is >250 bp downstream of the TSS (Figure 1A and Table S1). The distribution of genes with gene body peaks mirrors what has been previously described for the general pattern of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 enrichment in the C. elegans genome (Figure 3A; Evans et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2011). “Promoter peaks” are those peaks where H3K9me2 overlaps with a region 750 bp upstream to 250 bp downstream of the TSS, but not further than 250 bp downstream of the TSS (Figure 1B and Table S1). Whenever we refer to genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak, we mean genes that have an H3K9me2 peak solely at their promoter and not also in their gene body. In wild type, H3K9me2 gene body peaks are generally broader than promoter peaks (Figure 1, A and B and Figure S3A), and genes with body peaks (2991 at 20°/2871 at 26°) are around three times more abundant than genes with only a promoter peak (984 at 20°/981 at 26°) (Figure 1, C and D and Table S1).

Our analysis showed that loss of synMuv B proteins had a smaller effect on H3K9me2 in gene bodies than at promoters. lin-15B mutants had ∼12% fewer genes with a gene body peak compared to wild type when grown at 20°, and no reduction in the number of genes with H3K9me2 gene body peaks at 26° (Figure 1C and Table S2). In contrast, lin-15B mutants had significantly fewer genes with H3K9me2 promoter peaks at both 20° (∼42% fewer) and 26° (∼25% fewer) when compared to wild type (Figure 1D and Table S3). The genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak found in lin-15B are, for the most part, a subset of the genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak found in wild type (Figure S3). In both lin-35 and lin-37 mutants, there was no decrease in the number of genes with H3K9me2 gene body peaks (Figure 1C and Table S2). Unlike the significant loss of H3K9me2 promoter peaks in lin-15B mutants, fewer H3K9me2 promoter peaks were lost in lin-35 and lin-37 mutants at 20°, and no significant loss was observed at 26° (Figure 1D and Table S3). This is the first description of a molecular difference in phenotypes seen between mutants in DREAM complex members and lin-15B mutants, and may represent a difference in their molecular function at target loci.

Genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak are enriched for DREAM and LIN-15B target genes in wild type but not in lin-15B mutants

If localization of H3K9me2 to promoters is driven by synMuv B binding and functions to repress gene expression, we predicted that genes with H3K9me2 promoter peaks would be bound by synMuv B proteins in wild-type animals and would be upregulated in synMuv B mutants. To test this prediction, we identified genes bound by LIN-15B using previously unpublished LIN-15B ChIP-chip data from late embryos. We observed a high co-occurrence of LIN-15B binding and published DREAM complex binding in wild type, with 70% of DREAM bound loci also bound by LIN-15B (Figure S4). To determine if synMuv B protein binding, repression of target loci, and H3K9me2 promoter peaks co-occur, we defined two sets of synMuv B target genes: 170 DREAM complex targets are those genes bound by the DREAM complex at their promoter by ChIP-seq in late embryos (Goetsch et al. 2017) and also significantly upregulated in lin-35 mutant L1s at 26° (Petrella et al. 2011); 115 LIN-15B targets are those genes bound by LIN-15B at their promoter by ChIP-chip in late embryos (this paper) and also significantly upregulated in lin-15B mutant L1s at 26° (Petrella et al. 2011) (Table S1). Genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak were enriched for DREAM complex and LIN-15B target genes in wild type, lin-35, and lin-37 mutants but not in lin-15B mutants (Figure 2A). Thus, genes that have H3K9me2 promoter localization in wild type are correlated with DREAM complex and LIN-15B binding and repression, and this correlation is disrupted when LIN-15B is absent.

Germline genes lose H3K9me2 from their promoter in lin-15B mutants

One of the major phenotypes of many synMuv B mutants, including lin-15B mutants, is the ectopic expression in somatic cells of genes whose expression is normally restricted to the germline (Wang et al. 2005; Petrella et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2012). We investigated if genes that have an H3K9me2 promoter peak in wild-type L1s are enriched for genes that are specifically expressed in the germline. We analyzed four categories of expression: genes that are broadly expressed in all tissues (2576: ubiquitous), genes that are repressed in most tissues (415: silent), genes that are expressed specifically in somatic tissues (1181: soma-specific), and genes that are expressed specifically in the germline (169: germline-specific). Genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak in wild-type L1s are enriched for genes with germline-specific expression, but not for genes with ubiquitous, silent, or somatic expression (Figure 2B and Figure S5). These enrichments are mirrored when plotting H3K9me2 ChIP-seq signal around the TSS averaged over the genes in each expression category (Figure 2C). If H3K9me2 at germline gene promoters is correlated with synMuv B repression of germline gene expression in the soma, then we would predict that germline genes would lose H3K9me2 promoter peaks in synMuv B mutants. Indeed, in lin-15B mutants, there were many fewer germline-specific genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak, and there was a large decrease in the signal of H3K9me2 at the TSS of germline-specific genes (Figure 2, B and C). lin-35 and lin-37 mutants resembled wild type in having genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak enriched for germline-specific genes (Figure 2, B and C).

We also examined germline genes whose misregulation is correlated with the HTA phenotype (Petrella et al. 2011). HTA-germline targets are defined as genes normally expressed in the germline that are upregulated in arrested lin-35 mutant L1s at 26° and whose expression returns to near wild-type levels in HTA-suppressed lin-35; mes-4(RNAi) double mutant L1s at 26° (48: HTA-germline) (Petrella et al. 2011). Similar to what was seen with germline-specific genes, genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak were enriched for HTA-germline genes in wild type, lin-35, and lin-37 mutants, but this enrichment was much reduced in lin-15B mutants (Figure 2, B and C). Together, these data reveal a striking loss of H3K9me2 at the promoters of germline-specific and HTA-germline genes in lin-15B mutants, but not in lin-35 or lin-37 mutants.

H3K9me2 promoter peaks are distributed along the whole length of autosomes

Previous work on H3K9me2 in C. elegans focused on its distribution in broad domains on autosomal arms and the role of H3K9me2 in repressing repetitive sequences (Ikegami et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2015; Zeller et al. 2016). Little investigation has been done into what role the more narrowly focused H3K9me2 found at promoters may be serving in gene regulation. In C. elegans, genes with expression that is higher in the germline than other tissues (germline-enriched genes) or with expression exclusive to the germline (germline-specific genes) show a biased localization to the centers of autosomes compared to the localization of all coding genes (Figure S6). Therefore, if H3K9me2 promoter peaks are associated with regulation of germline gene expression, we would predict that H3K9me2 promoter peaks would also be found in the center regions of chromosomes and not be biased toward arm localization. We compared the distributions along autosomes of genes with H3K9me2 in their gene body vs. at their promoter. In wild type, genes with H3K9me2 in their gene body demonstrated the previously reported pattern of H3K9me2 enrichment on autosomal arms compared to centers (Figure 3, A and B). For genes with an H3K9me2 gene body peak, all mutants showed the same autosomal arm bias as seen in wild type (Figure 3, A and B and Figure S7). In contrast, genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak in wild type were more evenly distributed across autosomes, with weak or no depletion from autosomal centers (Figure 3, A and B). Notably, lin-15B mutants showed reduction of H3K9me2 promoter peaks in the center of all autosomes (Figure 3, A and B), suggesting that LIN-15B is needed for H3K9me2 localization at gene promoters in autosomal centers where germline genes are enriched. lin-35 mutants showed a distribution of genes with H3K9me2 at their promoter similar to wild type (Figure S7). lin-37 mutants were intermediate between lin-15B and lin-35 mutants (Figure S7). H3K9me2 promoter peaks in chromosome centers in wild type represent a pattern not previously described for H3K9me2 in C. elegans and place H3K9me2 promoter peaks in mainly euchromatic regions where they may affect coding gene expression. Additionally, the loss of H3K9me2 from promoters in autosomal centers in lin-15B mutants suggests that LIN-15B plays a specific role in directing H3K9me2 to areas of the genome where there are fewer repeats and more coding genes, especially germline genes.

Loss of H3K9me2 in mutants is associated with increased H3K4me3 on germline genes

Trimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 4 (H3K4me3) and lysine 36 (H3K36me3) are correlated with active gene expression (Liu et al. 2011; Ho et al. 2014; Evans et al. 2016). Thus, we expected to see increases in H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 on germline genes in synMuv B mutants. Indeed, synMuv B mutants displayed increases in H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 on germline-expressed, germline-specific, and HTA-germline genes but not on other categories of genes (Figure 4, Figure S8, and Figure S9). A total of 64% of genes (130 of 204, P-value < 1 × 10−28, hypergeometric test) with at least a 1.5-fold increase in H3K4me3 at their promoter in lin-15B compared to wild type were found to be germline-expressed (Figure 4, B and C). Increased levels of H3K36me3 and, especially, H3K4me3 on germline-specific genes were observed at 20° and 26° in both lin-15B and lin-35 mutants, but only at 26° in lin-37 mutants (Figure S8 and Figure S9). This is consistent with previous data showing that misexpression of germline genes in lin-37 mutants is more sensitive to temperature than in lin-15B and lin-35 mutants (Petrella et al. 2011). HTA-germline genes showed larger increases in H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 than germline-specific genes. This is expected as HTA-germline genes were defined partly by requiring these genes to be upregulated in lin-35 mutants (Petrella et al. 2011), while not all germline-specific genes are upregulated in synMuv B mutants. The increased levels of both H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 on germline-specific and HTA-germline genes in mutants is consistent with these genes being expressed at higher levels, most likely in a larger population of cells [i.e., somatic cells in addition to the two primordial germ cells (PGCs)] in these mutants.

We investigated if there is a correlation between loss from promoters of the repressive H3K9me2 chromatin modification and acquisition of H3K4me3, which is associated with gene activation. To compare those marks at promoters, we calculated the log2 fold change of the signal of each modification in lin-15B mutant/wild type within 250 bp upstream and downstream of the TSS. A higher histone modification signal in lin-15B mutants than wild type would result in a positive log2 fold change; a lower histone modification signal in lin-15B mutants than wild type would result in a negative log2 fold change. In lin-15B mutants, 25% of all genes (122 of 448) that had at least a 1.5-fold reduction of H3K9me2 promoter signal also had at least a 1.5-fold increase of H3K4me3 promoter signal (Figure 4B). Strikingly, 40% of germline-specific (6 of 15) and 75% of HTA-germline genes (12 of 16) that had reduced H3K9me2 promoter signal also had increased H3K4me3 promoter signal (Figure 4B). We investigated if more of the 122 genes that showed reduced H3K9me2 and increased H3K4me3 promoter signal in lin-15B mutants had an indication of being germline-expressed and regulated by synMuv B mutants. We found that 74% (90 of 122, P-value < 1 × 10−27) of those genes have evidence of being germline-expressed (Reinke et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2009) and 44% (54 of 122, P-value < 1 × 10−31) are upregulated in lin-15B mutants (Petrella et al. 2011). The same analysis of genes that have a concurrent loss of H3K9me2 and gain of H3K4me3 in lin-35 and lin-37 mutants compared to wild type showed similar but muted trends as observed in lin-15B mutants (Figure S10). However, unlike in lin-15B mutants, there was a subset of genes that in lin-35 and lin-37 mutants displayed increased H3K4me3 promoter signal without reduced H3K9me2 promoter signal (Figure S10). Because we did not observe H3K9me2 at the promoter of these genes in wild type, we surmise that repression of this subset of genes in wild type does not depend on H3K9me2 at their promoter. Altogether, the germline genes that have enrichment of H3K9me2 at their promoter in wild type lose that enrichment when upregulated in any of the three mutants.

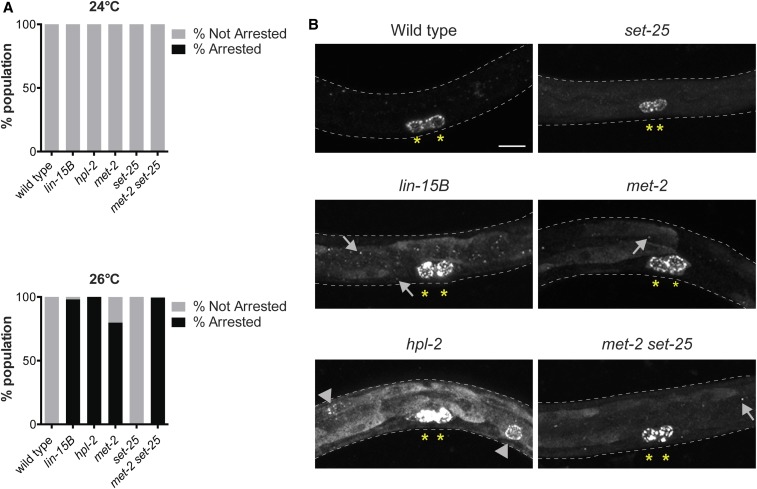

Global loss of H3K9me2 leads to phenotypes similar to lin-15B and DREAM complex mutants

To investigate if loss of H3K9me2 promoter localization plays an important role in lin-15B mutant phenotypes, we analyzed mutants for the histone methyltransferases (HMTs) responsible for H3K9 methylation. Loss of these HMTs leads to a global loss of all H3K9 methylation (Towbin et al. 2012; Garrigues et al. 2015), which may phenocopy lin-15B mutants. H3K9 methylation in C. elegans embryos is catalyzed by two HMTs, MET-2 and SET-25, which primarily catalyze H3K9me1/2 and H3K9me3, respectively (Towbin et al. 2012). If loss of H3K9 methylation is associated with ectopic germline gene expression and the HTA phenotype, we would expect that met-2 and set-25 mutants would show these phenotypes. set-25 single mutants, which lose H3K9me3, showed neither an HTA phenotype nor an ectopic germline gene expression phenotype, as assessed by staining for the germline-specific protein PGL-1 (Figure 5, A and B). Therefore, H3K9me3 does not appear to be important for repression of germline genes in the soma. In contrast, met-2 single mutants, which lose 80–90% of H3K9me2 and ∼70% of H3K9me3 (Towbin et al. 2012), displayed ∼80% larval arrest around the L3 stage at 26°, but no larval arrest at 24° (Figure 5A). Thus, met-2 mutants show an HTA phenotype similar to but weaker than lin-15B mutants (Figure 5A; Petrella et al. 2011). We also observed ectopic expression of PGL-1 in met-2 mutants at 26° similar to lin-15B mutants, with the PGL-1 protein being primarily cytoplasmic and diffuse in intestinal cells (Figure 5B). To test if the remaining 10–20% of H3K9me2 catalyzed by SET-25 in met-2 mutants (Towbin et al. 2012) partially represses germline gene expression in somatic cells, we analyzed met-2set-25 double mutants, which have been shown to completely lack H3K9 methylation during embryonic stages (Towbin et al. 2012; Garrigues et al. 2015). Consistent with residual SET-25-mediated H3K9me2 serving a role in repression of germline genes in somatic cells, met-2set-25 double mutants showed significantly enhanced larval arrest at 26° when compared to met-2 single mutants (Figure 5A). Similar to lin-15B, lin-35, and lin-37 mutants, met-2set-25 double mutants did not show increased larval arrest at 24°. Ectopic PGL-1 in met-2set-25 double mutants at 26° was similar to that seen in met-2 single mutants (Figure 5B). Altogether, our results show that a global loss of H3K9me2 phenocopies both the HTA and ectopic germline gene expression seen in synMuv B mutants.

Figure 5.

Complete loss of H3K9me2 during development phenocopies synMuv B mutants. (A) The percentage of F1 animals that arrested before the L4 larval stage was assessed for all genotypes indicated after parent hermaphrodites were upshifted from 20° to 24° or 26°. (B) Assessment of ectopic expression of PGL-1 in L1 animals at 26°. Yellow asterisks indicate the two primordial germ cells in which PGL-1 is solely expressed in wild type. Arrowheads indicate ectopic perinuclear punctate PGL-1 in intestinal cells. Arrows indicate ectopic punctate PGL-1 that is not perinuclear. Bar, 10 µm.

One of the known proteins that binds to methylated H3K9 to create a repressive chromatin environment is HP1 (Couteau et al. 2002; Nestorov et al. 2013; Garrigues et al. 2015). In C. elegans there are two HP1 homologs, HPL-1 and HPL-2. hpl-2 is a synMuv B gene. hpl-2 mutants display a variety of phenotypes including HTA and ectopic germline gene expression in the soma (Figure 5) (Couteau et al. 2002; Petrella et al. 2011), while hpl-1 mutants generally lack observable phenotypes (Schott et al. 2006). Therefore, we compared genes with H3K9me2 promoter peaks with previously published data on genes bound by HPL-2 in embryos (Garrigues et al. 2015). We confirmed that most of the genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak in our L1 wild-type samples also have such a peak in wild-type embryos (Figure S11A). We found that genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak in wild type that is lost in lin-15B mutants are enriched for promoter-bound HPL-2 (Figure S11). Additionally, the 122 genes that have decreased H3K9me2 and increased H3K4me3 in lin-15B mutants as compared to wild type are enriched for promoter-bound HPL-2 (Figure S11). These data suggest that HPL-2 binding may contribute to regulation of germline genes that are repressed in somatic cells through an H3K9me2 promoter peak. However, we noted differences in the pattern of PGL-1 accumulation in the soma of hpl-2 mutants compared to either lin-15B or met-2set-25 mutants; 75% (15/20) of hpl-2 mutant L1s displayed intestinal PGL-1 staining that was perinuclear and punctate, reminiscent of PGL-1 staining in the germline (Figure 5B) (Petrella et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2012). In contrast, none of the lin-15B, met-2, or met-2set-25 mutants analyzed (n = 19–20) displayed that pattern of intestinal staining (Figure 5B), unlike the previously published analysis of met-2 (Wu et al. 2012). These differences in the pattern of ectopic PGL-1 suggest that loss of H3K9me2 either at a subset of genes in lin-15B mutants or globally in met-2set-25 mutants is not equivalent to loss of HPL-2.

Discussion

Repression of germline gene expression in the soma is vital, as loss of germline gene repression is a hallmark of various disease states including cancer. Investigating the changes to chromatin that occur when germline genes are misexpressed in the somatic cells of mutants is a first step in understanding the mechanisms that repress germline genes to protect somatic fates and development. Here, we investigated the changes to histone modifications that occur in a subset of C. elegans synMuv B mutants that misexpress germline genes in the soma. We defined a new localization pattern for the repressive histone modification H3K9me2 in wild type, at the promoter of coding genes; unlike the previously described broad domains of H3K9me2, promoter peaks of H3K9me2 are not enriched on autosomal arms (Liu et al. 2011; Garrigues et al. 2015; Evans et al. 2016; Ahringer and Gasser 2018). Promoter enrichment of H3K9me2 in autosomal centers provides a new regulatory role for H3K9me2, in addition to its well-described regulation of repetitive elements on autosomal arms. We also found that, in wild-type somatic cells, genes with an H3K9me2 promoter peak are enriched for genes expressed specifically in the germline and genes that are synMuv B targets. The localization of H3K9me2 to germline genes and synMuv B targets is disrupted strongly in lin-15B mutants and weakly in DREAM complex mutants. We additionally showed that loss of H3K9me2 but not H3K9me3 phenocopies synMuv B mutants. Our data implicate H3K9me2 promoter enrichment as an important aspect of repression of germline gene expression in somatic cells.

There is strong evidence that a memory of gene expression/repression and associated chromatin modifications are transmitted from the parental germline to the developing embryo (Furuhashi et al. 2010; Rechtsteiner et al. 2010; Zenk et al. 2017; Tabuchi et al. 2018). For example, genes that were expressed in the germline continue to be marked with MES-4-generated H3K36me3 in embryos, even in the absence of ongoing transcription in embryos (Furuhashi et al. 2010; Rechtsteiner et al. 2010; Kreher et al. 2018). It is thought that H3K36me3 marks these genes for re-expression in the germline during postembryonic development. How then are germline genes repressed properly in somatic tissues when those tissues inherit germline genes with marks of active expression that potentially set those genes up for re-expression? Our data, along with other recent work, strongly implicate deposition of H3K9me2 at the proper time in development as necessary to create proper patterns of repressive chromatin in differentiating somatic cells. In C. elegans, H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 levels are very low in the nuclei of early stage embryos, and only start to accumulate when cells are transitioning from early embryogenesis to midembryogenesis at about the 50-cell stage (Mutlu et al. 2018). This is in part driven by the nuclear import of an active MET-2 complex that catalyzes conversion of H3K9me1 to H3K9me2. The timing of MET-2 import just precedes the stage in embryogenesis when zygotic transcription is upregulated and when tissue-specific expression patterns emerge (Spencer et al. 2011; Levin et al. 2012; Robertson and Lin 2015; Mutlu et al. 2018). Concurrent with MET-2 import and increased global H3K9 methylation is the creation of regions of compact chromatin within the nucleus (Mutlu et al. 2018). In support of the role of synMuv B proteins in the timing of chromatin compaction during embryogenesis, the formation of compact chromatin is delayed in lin-15B, and lin-35 mutants (Costello et al. 2019). Developmental chromatin compaction likely plays a role in lineage-specific gene repression and is proposed to be driven at least in part by H3K9 methylation. Our data suggest that loss of H3K9me2, either through loss of the MET-2 and SET-25 HMTs that catalyze the mark or through loss of proper localization of H3K9me2 to germline genes in lin-15B mutants, leads to misexpression of germline genes in somatic cells. We hypothesize that specific localization of H3K9me2 to germline gene promoters facilitated by LIN-15B is an important aspect of resetting the chromatin landscape of germline genes to prevent their expression in somatic lineages.

A striking aspect of our findings is the difference in changes to promoter-enriched H3K9me2 between lin-15B mutants and DREAM complex mutants. It was previously proposed, based on phenotype analysis, that LIN-15B is a member of the DREAM complex (Wu et al. 2012). Our data indicate that, although LIN-15B binds to and represses many of the same genes as the DREAM complex, its molecular function at those genes is probably distinct. The proposed DNA-binding domain of LIN-15B may allow it to be independently recruited to similar targets as the DREAM complex, where the two may function together to repress genes. This scenario has implications for regulation of gene expression in the germline as well as in the soma. Recent work from the Seydoux laboratory has implicated the loss of LIN-15B protein in the germline as important for germline development (Lee et al. 2017). Maternally provided LIN-15B is normally removed from the PGCs, while DREAM components are not (Lee et al. 2017). Our work suggests that loss of LIN-15B from the PGCs may protect essential germline genes from being H3K9 methylated and repressed in those cells. How the different synMuv B complexes work together to fully repress germline genes in somatic cells is still an open question. The establishment of H3K9me2 may be an initiating step in germline gene repression, or may be one aspect of a series of redundant steps necessary to repress germline genes. Analysis of the order and dependency of MET-2, LIN-15B, and the DREAM complex binding to germline genes is necessary to address these questions.

The work presented here focuses on a subset of germline genes that are regulated through the LIN-15B/H3K9me2/DREAM complex pathway. Although this pathway may regulate only a subset of genes in this way, the repercussions to development are clear: organisms defective in this regulation cannot thrive in the face of challenges (e.g., high temperature) when somatic fates are compromised. Recent work in Drosophila underscores the importance of H3K9 methylation in repression of a subset of coding genes to maintain proper cell fate. In the Drosophila ovary, loss of H3K9me3 leads to upregulation of testis-specific transcripts, and changes the fate of ovarian germ cells, leading to sterility (Smolko et al. 2018). As in C. elegans, prior investigations of H3K9 methylation loss in Drosophila had focused primarily on upregulation of repetitive elements (Rangan et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2015; Zeller et al. 2016). However, it is clear that H3K9me2/3 loss leading to upregulation of small sets of coding genes in a tissue-specific manner can have profound effects on cell fate and function. As more studies investigate the roles of H3K9me2/3 in repression of coding genes, it seems likely that new pathways will be uncovered that are necessary to create different patterns of H3K9me2/3 in different tissues for maintenance of proper cell fate.

The expression of germline genes in somatic tissues leads to a variety of adverse consequences in diverse animal species. These include L1 starvation and reduced apoptosis during development in C. elegans synMuv B mutants, tumor formation in Drosophila l(3)mbt mutants, and poor outcomes in human tumors that express germline genes (Janic et al. 2010; Petrella et al. 2011; Whitehurst 2014; Al-Amin et al. 2016). Thus, there is a need across species to repress germline gene expression in the soma to facilitate proper development and somatic function. Our data suggest that repression of germline genes during development in somatic tissues through H3K9me2 may be a conserved mechanism. As in C. elegans embryonic somatic cells, mammalian ES cells also repress expression of germline genes (Blaschke et al. 2013). Mouse ES cells have been shown to lose repression of germline genes when H3K9me2 marking of those genes is compromised by either Vitamin C treatment or knock-down of Max (myc-associate factor X) (Blaschke et al. 2013; Maeda et al. 2013; Sekinaka et al. 2016; Ebata et al. 2017). The conservation of H3K9me2 on germline genes, and its role in repressing those genes in developing somatic lineages, may represent an ancient regulatory role for H3K9me2. Since in both C. elegans and Drosophila, repression of germline genes in the soma is through complexes known to interact with chromatin (Janic et al. 2010; Petrella et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2012), it will be interesting to investigate if ectopic expression of germline genes in human somatic tumors is due to loss of these conserved complexes. Finally, not all germline genes, but only a specific subset, are ectopically expressed in these models. Why only certain germline genes are vulnerable to misexpression, if those genes are the same across species, and which cellular processes are disrupted as a result of germline gene misexpression singularly or as a group, are open questions. Further investigation could have broad implications for understanding conserved basic chromatin mechanisms and therapeutic targets for cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Anita Manogaran for comments and discussion of the manuscript. Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). This work used the Vincent J. Coates Genomics Sequencing Laboratory at University of California (UC) Berkeley, supported by NIH S10 OD018174 Instrumentation Grant. This work was supported by a NIH grants R00GM98436 and R15GM122005 to L.N.P. and NIH grant R01GM34059 to S.S.

Footnotes

Supplemental material available at https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.7823846.

Communicating editor: D. Greenstein

Literature Cited

- Ahringer J., Gasser S. M., 2018. Repressive chromatin in Caenorhabditis elegans: establishment, composition, and function. Genetics 208: 491–511. 10.1534/genetics.117.300386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Amin M., Min H., Shim Y. H., Kawasaki I., 2016. Somatically expressed germ-granule components, PGL-1 and PGL-3, repress programmed cell death in C. elegans. Sci. Rep. 6: 33884 10.1038/srep33884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke K., Ebata E. T., Karimi M. M., Zepeda-Martínez J. A., Goyal P., et al. , 2013. Vitamin C induces Tet-dependent DNA demethylation and a blastocyst-like state in ES cells. Nature 500: 222–226. 10.1038/nature12362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello, M. E., and L. N. Petrella, 2019. C. elegans synMuv B proteins regulate spatial and temporal chromatin compaction during development. bioRxiv 10.1101/538801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coustham V., Bedet C., Monier K., Schott S., Karali M., et al. , 2006. The C. elegans HP1 homologue HPL-2 and the LIN-13 zinc finger protein form a complex implicated in vulval development. Dev. Biol. 297: 308–322. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couteau F., Guerry F., Muller F., Palladino F., 2002. A heterochromatin protein 1 homologue in Caenorhabditis elegans acts in germline and vulval development. EMBO Rep. 3: 235–241. 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M., Kim E. B., Han M., 2006. Diverse chromatin remodeling genes antagonize the Rb-Involved synMuv pathways in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2: e74 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebata K. T., Mesh K., Liu S., Bilenky M., Fekete A., et al. , 2017. Vitamin C induces specific demethylation of H3K9me2 in mouse embryonic stem cells via Kdm3a/b. Epigenetics Chromatin 10: 36 10.1186/s13072-017-0143-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A. E., 2002. Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 207–210. 10.1093/nar/30.1.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelhofer T. A., Minoda A., Klugman S., Lee K., Kolasinska-Zwierz P., et al. , 2011. An assessment of histone-modification antibody quality. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18: 91–93. 10.1038/nsmb.1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans K. J., Huang N., Stempor P., Chesney M. A., Down T. A., et al. , 2016. Stable Caenorhabditis elegans chromatin domains separate broadly expressed and developmentally regulated genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113: E7020–E7029. 10.1073/pnas.1608162113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay D. S., Yochem J., 2007. The SynMuv genes of Caenorhabditis elegans in vulval development and beyond. Dev. Biol. 306: 1–9. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser R., Lin C. J., 2016. Epigenetic reprogramming of the zygote in mice and men: on your marks, get set, go! Reproduction 152: R211–R222. 10.1530/REP-16-0376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuhashi H., Takasaki T., Rechtsteiner A., Li T., Kimura H., et al. , 2010. Trans-generational epigenetic regulation of C. elegans primordial germ cells. Epigenetics Chromatin 3: 15 10.1186/1756-8935-3-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigues J. M., Sidoli S., Garcia B. A., Strome S., 2015. Defining heterochromatin in C. elegans through genome-wide analysis of the heterochromatin protein 1 homolog HPL-2. Genome Res. 25: 76–88. 10.1101/gr.180489.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetsch P. D., Garrigues J. M., Strome S., 2017. Loss of the Caenorhabditis elegans pocket protein LIN-35 reveals MuvB’s innate function as the repressor of DREAM target genes. PLoS Genet. 13: e1007088 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Yang B., Li Y., Xu X., Maine E. M., 2015. Enrichment of H3K9me2 on unsynapsed chromatin in Caenorhabditis elegans does not target de novo sites. G3 (Bethesda) 5: 1865–1878. 10.1534/g3.115.019828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M. M., Ceol C. J., Lu X., Horvitz H. R., 2006. Some C. elegans class B synthetic multivulva proteins encode a conserved LIN-35 Rb-containing complex distinct from a NuRD-like complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 16782–16787. 10.1073/pnas.0608461103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho J. W. K., Jung Y. L., Liu T., Alver B. H., Lee S., et al. , 2014. Comparative analysis of metazoan chromatin organization. Nature 512: 449–452. 10.1038/nature13415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami K., Egelhofer T. A., Strome S., Lieb J. D., 2010. Caenorhabditis elegans chromosome arms are anchored to the nuclear membrane via discontinuous association with LEM-2. Genome Biol. 11: R120 10.1186/gb-2010-11-12-r120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janic A., Mendizabal L., Llamazares S., Rossell D., Gonzalez C., 2010. Ectopic expression of germline genes drives malignant brain tumor growth in Drosophila. Science 330: 1824–1827. 10.1126/science.1195481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki I., Shim Y. H., Kirchner J., Kaminker J., Wood W. B., et al. , 1998. PGL-1, a predicted RNA-binding component of germ granules, is essential for fertility in C. elegans. Cell 94: 635–645. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81605-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W. J., Zweig A. S., Barber G., Hinrichs A. S., Karolchik D., 2010. BigWig and BigBed: enabling browsing of large distributed datasets. Bioinformatics 26: 2204–2207. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolasinska-Zwierz P., Down T., Latorre I., Liu T., Liu X. S., et al. , 2009. Differential chromatin marking of introns and expressed exons by H3K36me3. Nat. Genet. 41: 376–381. 10.1038/ng.322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreher J., Takasaki T., Cockrum C., Sidoli S., Garcia B. A., et al. , 2018. Distinct roles of two histone methyltransferases in transmitting H3K36me3-based epigenetic memory across generations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 210: 969–982. 10.1534/genetics.118.301353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S. L., 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10: R25 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latorre I., Chesney M. A., Garrigues J. M., Stempor P., Appert A., et al. , 2015. The DREAM complex promotes gene body H2A.Z for target repression. Genes Dev. 29: 495–500. 10.1101/gad.255810.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. S., Lu T., Seydoux G., 2017. Nanos promotes epigenetic reprograming of the germline by down-regulation of the THAP transcription factor LIN-15B. eLife 6: pii: e30201. 10.7554/eLife.30201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M., Hashimshony T., Wagner F., Yanai I., 2012. Developmental milestones punctuate gene expression in the Caenorhabditis embryo. Dev. Cell 22: 1101–1108. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Rechtsteiner A., Egelhofer T. A., Vielle A., Latorre I., et al. , 2011. Broad chromosomal domains of histone modification patterns in C. elegans. Genome Res. 21: 227–236. 10.1101/gr.115519.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda I. D., Okamura D., Tokitake Y., Ikeda M., Kawaguchi H., et al. , 2013. Max is a repressor of germ cell-related gene expression in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 4: 1754 10.1038/ncomms2780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner B., Warner A., Wong K., Dube N., Lorch A., et al. , 2009. An integrated strategy to study muscle development and myofilament structure in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000537 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister P., Towbin B. D., Pike B. L., Ponti A., Gasser S. M., 2010. The spatial dynamics of tissue-specific promoters during C. elegans development. Genes Dev. 24: 766–782. 10.1101/gad.559610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan H. D., Santos F., Green K., Dean W., Reik W., 2005. Epigenetic reprogramming in mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14: R47–R58. 10.1093/hmg/ddi114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu B., Chen H. M., Moresco J. J., Orelo B. D., Yang B., et al. , 2018. Regulated nuclear accumulation of a histone methyltransferase times the onset of heterochromatin formation in C. elegans embryos. Sci. Adv. 4: eaat6224 10.1126/sciadv.aat6224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestorov P., Tardat M., Peters A. H., 2013. H3K9/HP1 and polycomb: two key epigenetic silencing pathways for gene regulation and embryo development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 104: 243–291. 10.1016/B978-0-12-416027-9.00008-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrella L. N., Wang W., Spike C. A., Rechtsteiner A., Reinke V., et al. , 2011. synMuv B proteins antagonize germline fate in the intestine and ensure C. elegans survival. Development 138: 1069–1079. 10.1242/dev.059501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangan P., Malone C. D., Navarro C., Newbold S. P., Hayes P. S., et al. , 2011. piRNA production requires heterochromatin formation in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 21: 1373–1379. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team , 2018. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- Rechtsteiner A., Ercan S., Takasaki T., Phippen T. M., Egelhofer T. A., et al. , 2010. The histone H3K36 methyltransferase MES-4 acts epigenetically to transmit the memory of germline gene expression to progeny. PLoS Genet. 6: e1001091 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke V., Cutter A. D., 2009. Germline expression influences operon organization in the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. Genetics 181: 1219–1228. 10.1534/genetics.108.099283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke V., Gil I. S., Ward S., Kazmer K., 2004. Genome-wide germline-enriched and sex-biased expression profiles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 131: 311–323. 10.1242/dev.00914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson S., Lin R., 2015. The maternal-to-zygotic transition in C. elegans. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 113: 1–42. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy P. J., Stuart J. M., Lund J., Kim S. K., 2002. Chromosomal clustering of muscle-expressed genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 418: 975–979. 10.1038/nature01012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott S., Coustham V., Simonet T., Bedet C., Palladino F., 2006. Unique and redundant functions of C. elegans HP1 proteins in post-embryonic development. Dev. Biol. 298: 176–187. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekinaka T., Hayashi Y., Noce T., Niwa H., Matsui Y., 2016. Selective de-repression of germ cell-specific genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts in a permissive epigenetic environment. Sci. Rep. 6: 32932 10.1038/srep32932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolko A. E., Shapiro-Kulnane L., Salz H. K., 2018. The H3K9 methyltransferase SETDB1 maintains female identity in Drosophila germ cells. Nat. Commun. 9: 4155 10.1038/s41467-018-06697-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J. S., Johnson W. E., Zhu X., Zhang X., Li W., et al. , 2007. Model-based analysis of two-color arrays (MA2C). Genome Biol. 8: R178 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellman P. T., Rubin G. M., 2002. Evidence for large domains of similarly expressed genes in the Drosophila genome. J. Biol. 1: 5 10.1186/1475-4924-1-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer W. C., Zeller G., Watson J. D., Henz S. R., Watkins K. L., et al. , 2011. A spatial and temporal map of C. elegans gene expression. Genome Res. 21: 325–341. 10.1101/gr.114595.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S., Wood W. B., 1983. Generation of asymmetry and segregation of germ-line granules in early C. elegans embryos. Cell 35: 15–25. 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90203-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi T. M., Rechtsteiner A., Jeffers T. E., Egelhofer T. A., Murphy C. T., et al. , 2018. Caenorhabditis elegans sperm carry a histone-based epigenetic memory of both spermatogenesis and oogenesis. Nat. Commun. 9: 4310 10.1038/s41467-018-06236-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin B., González-Aguilera C., Sack R., Gaidatzis D., Kalck V., et al. , 2012. Step-wise methylation of histone H3K9 positions heterochromatin at the nuclear periphery. Cell 150: 934–947. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unhavaithaya Y., Shin T. H., Miliaras N., Lee J., Oyama T., et al. , 2002. MEP-1 and a homolog of the NURD complex component Mi-2 act together to maintain germline-soma distinctions in C. elegans. Cell 111: 991–1002. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01202-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Kennedy S., Conte D., Kim J. K., Gabel H. W., et al. , 2005. Somatic misexpression of germline P granules and enhanced RNA interference in retinoblastoma pathway mutants. Nature 436: 593–597. 10.1038/nature04010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhao Y., Wong K., Ehlers P., Kohara Y., et al. , 2009. Identification of genes expressed in the hermaphrodite germ line of C. elegans using SAGE. BMC Genomics 10: 213 10.1186/1471-2164-10-213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Pan L., Wang S., Zhou J., McDowell W., et al. , 2011. Histone H3K9 trimethylase Eggless controls germline stem cell maintenance and differentiation. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002426 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst A. W., 2014. Cause and consequence of cancer/testis antigen activation in cancer. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 54: 251–272. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Shi Z., Cui M., Han M., Ruvkun G., 2012. Repression of germline RNAi pathways in somatic cells by retinoblastoma pathway chromatin complexes. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002542 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller P., Padeken J., van Schendel R., Kalck V., Tijsterman M., et al. , 2016. Histone H3K9 methylation is dispensable for Caenorhabditis elegans development but suppresses RNA:DNA hybrid-associated repeat instability. Nat. Genet. 48: 1385–1395. 10.1038/ng.3672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenk F., Loeser E., Schiavo R., Kilpert F., Bogdanovic O., et al. , 2017. Inherited H3K27me3 restricts enhancer function during maternal-to-zygotic transition. Science 357: 212–216. 10.1126/science.aam5339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Liu T., Meyer C. A., Eeckhoute J., Johnson D. S., et al. , 2008. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9: R137 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All strains and noncommercially available reagents are available upon request. All ChIP-seq, ChIP-chip, and expression data are available in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al. 2002) under accession number GSE126884. Supplemental material available at https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.7823846.