Abstract

Objective

Depression in patients with cardiovascular disease is associated with increased risk of adverse clinical outcomes. Investigators have searched for potential biobehavioral explanations for this increased risk. Platelet activation and response to serotonin is an attractive potential mechanism. Our objective was to examine platelet serotonin signaling in a group of patients with coronary artery disease and comorbid depression to define the relationship between platelet serotonin signaling and cardiovascular complications.

Methods

A total of 300 patients with CAD were enrolled (145 with acute coronary syndrome and 155 with stable coronary artery disease). Depression was assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV as well as Beck depression inventory-II in a dichotomous and continuous manner. Platelet serotonin response was measured by serotonin augmented aggregation, direct platelet serotonin activation, platelet serotonin receptor density, and platelet serotonin uptake. Cardiovascular outcomes were assessed at 12-month follow up.

Results

One third of enrolled participants had at least minimal depressive symptoms and 13.6% had major depressive disorder. Depressed cardiovascular patients had significantly higher incidence of major (OR=3.43; 95%CI=1.49-7.91, p=0.004) and minor (OR=2.42; 95 %CI=1.41-4.13,p=0.001) adverse cardiac events. Platelet serotonin response was not significantly different in patients with depression. Participants with MDD had higher serotonin receptor density (997.5 ± 840.8 vs 619.3 ± 744.3 fmol/ug, p = 0.009) primarily found in ACS patients. Depressed patients with minor adverse cardiac events had increased platelet response to serotonin.

Conclusions

Depressed cardiovascular patients had higher serotonin receptor density, and significantly higher incidence of major and minor cardiac adverse events. Future studies with larger sample-sizes including patients with more severe depression are needed to expand on the present hypothesis-generating findings.

Keywords: Platelets, Serotonin, Depression, Cardiovascular disease, Morbidity

Introduction

The relationship between cardiovascular disease and depression has been studied for several decades. In particular, it has been observed that the two conditions together are more lethal than either diagnosis alone1-3. After adjusting for age and predictors of cardiovascular risk, patients who have had a myocardial infarction (MI) have an increased risk of mortality if they are found to be depressed at the time of the index hospitalization4. Depression is associated with a 77% increased risk of all-cause mortality, 10 years after percutaneous coronary intervention. 5 Among young women with CAD, depression is associated with an increased risk of death.6 Many investigators have searched for potential biobehavioral explanations for this increased risk7. Several plausible potential mechanisms have been proposed including behaviors associated with major depression, such as medication noncompliance, cigarette smoking, and physical inactivity, or biological factors such as altered autonomic nervous system activity, a proinflammatory state, endothelial dysfunction and/or increased platelet activation1, 7, 8.

Platelet activation is an attractive potential mechanism for the increased risk of death in individuals with heart disease and comorbid depression 9. In fact, increased platelet aggregability has been found in depressed patients without cardiovascular disease. High levels of depressive symptoms are significantly associated with increased myocardial infarction and cardiac death.10, 11 Platelets play an integral role in cardiovascular disease and coronary thrombosis12.

Platelets are the major transporter of serum serotonin in the body13. Serotonin is taken up into the platelet via the serotonin transporter (SERT) and then stored in dense granules with calcium and adenosine triphosphate14. Once released from the platelet, serotonin induces a number of biological processes by interacting with various membrane receptors. One such receptor is the serotonin 2A receptor, which can lead to further platelet activation and to vasoconstriction. To date, there have not been many large-scale assessments of platelet serotonin signaling in patients who have cardiovascular disease and comorbid major depression. In particular, there are not published data on platelet serotonin signaling in depressed cardiac patients with increased cardiovascular complications. Most of the published data assessing serotonin signaling in depressed patients with cardiovascular disease have been reviews of small clinical studies15, 16. The objective of the present study was to examine platelet serotonin signaling in a large group of patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and in patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). We assessed depressive symptomatology and serotonin signaling in both study samples in an attempt to define the relationship between serotonin signaling and depressive symptomatology in patients with known cardiovascular disease. We further assessed serotonin platelet signaling in those with and without major or minor adverse cardiac events in the 12-month follow up period after enrollment.

Methods

Study Sample

A total of 300 patients with CAD were enrolled between February 2011 and May 2015. Inclusion criteria for all study samples were: 1) age >21 years; 2) stable CAD or ACS; 3) ability to provide written informed consent, and; 4) current aspirin use. Exclusion criteria included:1) age ≤ 21 years; 2) current use of antidepressants; 3) current or previous (14 days) use of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor; 4) active narcotic use by personal report or laboratory testing; 5) baseline platelet count <100,000/μl, and; 6) expected mortality within the next year. All consecutive patients with an ACS (unstable angina or acute MI as defined by the WHO17) admitted to the inpatient cardiology service at a single urban academic medical center, and who met inclusion criteria, were approached for participation in this study. Study samples were enrolled within the first 72 hours of hospitalization. In total, 145 ACS patients were enrolled. Additionally, 155 patients with stable CAD were recruited from outpatient cardiology clinics. Stable CAD patients were defined as those diagnosed with CAD by cardiac catheterization (≥ 50% coronary stenosis), electrocardiographic (ECG) criteria of prior MI, or cardiac stress testing revealing ischemia or infarction without an ACS in the past 12 months.

Determination of the presence (or absence) of major depressive disorder (MDD) was determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders (SCID-IV-TR)18 at initial assessment by a licensed clinical psychologist or psychiatrist and, again, at a one-month follow-up time point. The interviewer for the first and second depression assessment was blinded to the results of all platelet measurements. Depression severity was determined using the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)19. The SCID-IV-TR interview assesses symptoms for a one-month period prior to the assessment. The presence or absence of depression is categorical. In contrast, the BDI-II assesses depressive symptoms during the previous two weeks. Total BDI-II scores range from 0 to 63, and indicate different levels of depressive symptomatology, including: no (0), minimal (<10), mild-to-moderate (10-18), moderate-to-severe (19-29), and severe (≥30) symptoms of depression19. Therefore, a score lower than 10 indicates a low probability of clinically significant depression and a total score of 10 or higher indicates at least mild-to-moderate symptoms of depression. This cut off has been found to be clinically meaningful, and prior research has found this threshold to carry increased risk for post-ACS recurrent cardiac events.20

Composite cardiovascular outcomes, designated as major and minor adverse cardiac events, were assessed at a 12-month follow-up time point. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board, and all patients provided informed consent.

Measures

Clinical Follow Up

Composite cardiovascular outcomes designated as major and minor adverse cardiac events were assessed 12 months after hospital discharge for the ACS group and 12 months after enrollment for the stable CAD group. The definition of major adverse cardiac events was: death (all-cause), non-fatal MI, non-fatal cardiac arrest, and non-elective revascularization. Minor adverse events included: cardiac hospitalization, bleeding, new heart failure, new ECG changes without elevation of cardiac biomarkers. In patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention, minor adverse cardiac events included: asymptomatic cardiac biomarker elevation, elective revascularization, and target vessel revascularization. These adverse events were assessed by follow-up phone call and medical record evaluation. MI was defined as an episode of typical ischemic chest pain accompanied by new elevation of the cardiac troponin I of greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal (in a patient with unstable angina as the admission diagnosis). For a patient with an admitting diagnosis of MI, an MI during the hospitalization was defined as typical ischemic chest pain and an increase in cardiac troponin I of greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal, with a characteristic rising and falling pattern. Patients were classified hierarchically; if criteria for both major and minor adverse cardiac events were met, the patient was included only in the major adverse cardiac event group.

Blood Samples

Platelet Aggregation

All platelet assays were performed within 2-4 hours of blood draw. Samples were immediately centrifuged to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Once PRP was obtained, the remainder of the blood was centrifuged to form platelet-poor plasma (PPP) as a control. Platelet aggregation was assessed using standard light transmission in PRP with a CHRONO-LOG® Aggregometer (Havertown, PA). Serotonin (5-HT)-hydrochloride augmented with epinephrine (1 μM) was added to PRP to obtain 0.3, 3, 5, 15, and 30 μM of serotonin. 5-HT is a very weak platelet agonist in vitro. It causes reversible platelet aggregation and is considered a ‘helper agonist’; Hence, it is generally used in conjunction with a second agonist when measuring platelet aggregation21. A fixed dose of epinephrine (1 μM) was chosen because it induces an increase in the maximal response to 5-HT without changing the EC50 value of 5-HT or the affinity of 5-HT to the platelet 5-HT2A receptor22. 1 mM arachidonic acid was used to assess aspirin response. Platelet aggregation results were expressed as the final concentration of serotonin producing half-maximal effect (EC50 5HT). Lower EC50 5HT indicates higher platelet aggregation, and higher EC50 5HT indicates lower platelet aggregation. Results will be expressed as log EC50 5HT if results are not normally distributed.

Platelet Activation

Flow cytometry was performed to measure platelet activation initiated by serotonin. Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser peptide (RGDS, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as a negative control. For flow cytometry, activated glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antibody-fluorescein isothiocyanate (PAC-1-FITC, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was used to determine the conformational change of activated platelets, while anti-Integrin beta-3-peridinin chlorophyll (CD61-PerCP, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was used to label platelets for analysis. The samples were incubated at room temperature and quenched with 1% paraformaldehyde (Polysciences). Samples were analyzed using a FACS-Caliber® flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Results were represented as histograms and dot plots using Cell Quest 3.1 software (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), with percent activation representing the level of activation.

Serotonin Receptor Density and Uptake

Serotonin Receptor Density

Blood was drawn into tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Tubes were centrifuged at 200×g (30 min, 4°C), and the PRP thus obtained was centrifuged (10.000×g, 4°C, 10 min) for isolation of platelet pellets. These pellets were washed twice with buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA; pH 7.4), centrifuged at 10.000×g (4°C, 10 min), lysed twice with a hypotonic buffer (5 mM Tris–HCl, 5 mM EDTA; pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 10,000×g (4°C, 20 min). After the second centrifugation, the pellets were re-suspended in Tris–HCl buffer to obtain a protein concentration of approximately 0.5–1 mg/ml. Membrane suspensions were frozen and stored at −80°C until later analysis, as previously described.23

5-HT2A receptor binding was performed by incubating 150 μl of platelet membrane suspension with 1.6 nM of [3H] ketanserin (Perkin Elmer) for three hours at 25°C in a total volume of 500 μl. Nonspecific binding was determined by adding 50 μl of mianserin (10 μM). After incubation, 5 ml of cold buffer was added to each tube, and the suspension was filtered through Brandel filter paper prewashed with 0.3% polyethylenimine using a Brandel M-24 cell harvester (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The filter paper was then placed in vials containing scintillation liquid, and radioactivity was quantified the following day using a scintillation counter. Protein concentrations were determined by ELISA using Pierce® BCA protein assay kits (Thermo Scientific) and BIORAD microplate manager 6 software. Tris buffer was used as blanks. All samples were run in triplicate. Receptor density was calculated using the following formula: [(Specific binding- Nonspecific Binding)/ [3H] ketanserin specific activity/ Protein concentration] × assay volume in μl. Results are expressed as fmol/μg. Results (N) reported only for accurate triplicate samples.

Serotonin Uptake

Blood was drawn into a tube containing acid-citrate-dextrose (BD Vacutainer, Thermo Fisher) and centrifuged to obtain PRP. The platelet count was adjusted to 200 × 106 platelets/ml. Each patient sample was divided into six tubes (3 cold and 3 hot). Platelet buffer was placed into all six tubes followed by pargyline (Sigma), and 100ul of PRP. Fluoxetine (Sigma) (final concentration 22.3 μM) was added only into the three cold tubes. All tubes were then incubated for ten minutes at 37°C. Immediately following incubation, tritiated serotonin [3H]5-HT (50 nM, specific activity 27.7 Ci/mmol, 0.0083 nM, Perkin Elmer) was placed into all tubes and incubated for 3 minutes at 37° C. Samples were pipetted into 96-well plates and then quenched by the addition of platelet buffer and immediate filtration through prewashed with 0.3% polyethylenimine Whatman GF-B filters. Assay tubes and filters were washed with an additional 5 ml of platelet buffer. Filters were air dried, placed in Beckman Ready-Solv HP scintillation counting fluid, and counted for [3H]5-HT. Platelet 5-HT uptake was expressed as counts per minute (cpm) and represents net total uptake (specific minus non-specific).

Statistical Analysis

We divided the study sample by their Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score as non-depressed (BDI 0-9) and depressed (BDI 10 or greater). The platelet aggregation variable were log transformed for plotting and analysis, as data was right skewed. We tabulated demographic and cardiovascular risk factor characteristics, overall and stratified either by depression status of patients or by their ACS vs CAD status. We presented means and standard deviations of continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Differences between groups were examined using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. We also presented the means and standard deviations of platelet activation by serotonin by depression groups for various concentrations of the agonist. We used box and whisker plots to graph the medians and interquartile ranges of log EC50 5HTs for platelet aggregation and receptor densities by depression status using two different definitions: (a) non-depressed (BDI 0-9) versus depressed (BDI 10 or greater) and (b) absence versus presence of MDD. Differences in these variables by depression groups were tested using t-test for receptor density and nonparametric rank sum test for EC50. We graphed the distributions of percent platelet activation at different agonist concentrations and by MDD depression status in ACS and CAD groups, and also tabulated these numbers in the supplemental material. We tested the association of receptor density after adjusting for the prespecified covariates age, sex, clopidogrel use, diabetes, and smoking using linear regression. We assessed the possibility that there was an interaction by group (ACS/stable CAD) regarding the association between platelet function and depression by adding an interaction term in the regression analysis. When a significant interaction was found, we then evaluated the potential association in each group separately; if no interaction by group was found, we only evaluated the potential association in the combined group. We compared the percentage of individuals that had either major adverse events (either death, myocardial infarction, nonfatal cardiac arrest, nonelective revascularization recorded during any visit) or minor adverse events (hospitalization for cardiac indications, bleeding, new onset congestive heart failure recorded during any visit, ischemic ECG changes, minor troponin elevations, elective revascularization) using either the definition of depression above or by the presence of MDD during using Fisher exact tests. We performed further analyses limited to individuals who had either incident minor adverse events or who had major adverse events. In these individuals, in separate models, we examined the baseline association of log(EC50 5HT) for serotonin with depression using the two definitions, adjusting for age, sex and the use of Clopidogrel. Results were considered statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level.

In supplemental analysis, we tabulated the distribution of platelet aggregation to arachidonic acid overall and by ACS vs CAD status, examining group differences using the rank sum test. We tabulated the association of platelet measures with MDD and dichotomous BDI by logistic regression and also BDI as a continuous measure using linear regression, presenting data for the full study sample, and for CAD and ACS separately. Additionally we tabulated the interaction p-value testing the hypothesis that the associations of platelet function with BDI differed by ACS vs CAD.

Results

Study Sample

We screened 2115 patients of which 458 (21.7%) were on antidepressants and were therefore excluded. We eventually recruited 300 participants. Of the 300 participants recruited, 13 were eliminated (1 because of an incomplete BDI-II, 6 because they did not undergo a blood draw, 2 because of screen failures, 2 because of inability to give informed consent, and 2 who withdrew their consent) leaving 287 who had complete BDI-II assessments at the initial visit. Demographics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. There were 113 ACS and 152 stable CAD patients that completed the assessment at the one month follow up time period. Of the 287 participants who had complete BDI assessments, 233 (81%) had 12 month clinical follow up, the remainder were lost to follow up (N=52) or were deceased (N=2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of study variables

| Total (N = 287) |

Non- depressed Group (N = 188) |

Depressed Group (N = 99) |

p | Stable CAD (N=153) |

ACS (N=137) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), (±SD) | 62.2 (11.1) | 63.9 (10.9) | 59.0 (10.7) | < 0.001 | 65.3 (9.75) | 59.1 (11.6) | < 0.001 |

| Age Distribution by sex (y, ±SD) | |||||||

| Female | 63.0 (10.2) | 65.0 (10.6) | 60.4 (9.1) | 0.043 | 64.8 (9.4) | 61.3 (10.8) | 0.123 |

| Male | 61.9 (11.4) | 63.5 (11.0) | 58.3 (11.5) | 0.002 | 65.5 (9.9) | 58.2 (11.8) | < 0.001 |

| Gender n (%): | |||||||

| Female | 80 (27.9) | 46 (24.5) | 34 (34.3) | 0.076 | 43 (28.1) | 38 (27.7) | 0.95 |

| Race/ Ethnicity n (%): | 0.25 | ||||||

| White | 227 (79.1) | 152 (80.9) | 75 (75.8) | 0.54 | 128 (83.7) | 102 (74.5) | |

| African American | 48 (16.7) | 29 (15.4) | 19 (19.2) | 21 (13.7) | 27 (19.7) | ||

| Asian | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (.7) | 2 (1.5) | ||

| Other | 9 (3.1) | 6 (3.2) | 3 (3.0) | 3 (2.0) | 6 (4.4) | ||

| Education n (%) | 0.28 | ||||||

| Lower Level | 61 (21.4) | 41 (22.0) | 20 (20.2) | 0.32 | 29 (19.0) | 34 (25.2) | |

| High School Grad | 82 (28.8) | 48 (25.8) | 34 (34.3) | 41 (26.8) | 41 (30.4) | ||

| College-Some | 66 (23.2) | 42 (22.6) | 24 (24.2) | 37 (24.2) | 29 (21.5) | ||

| College Grad | 50 (17.5) | 34 (18.3) | 16 (16.2) | 27 (17.7) | 23 (17.0) | ||

| Advanced | 26 (9.1) | 21 (11.3) | 5 (5.1) | 19 (12.4) | 8 (5.9) | ||

| Marital Status n (%) | 0.027 | ||||||

| Single | 64 (22.5) | 38 (20.4) | 26 (26.5) | 0.21 | 24 (15.9) | 40 (29.4) | |

| Married | 154 (54.2) | 109 (58.6) | 45 (45.9) | 85 (56.3) | 70 (51.5) | ||

| Divorced | 32 (11.3) | 20 (10.75) | 12 (12.2) | 18 (11.9) | 14 (10.3) | ||

| Widowed | 34 (12.0) | 19 (10.2) | 15 (15.3) | 24 (15.9) | 12 (8.8) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2, SD) | 31.2 (6.9) | 30.5 (6.3) | 32.5 (7.9) | 0.017 | 30.5 (6.3) | 32.5 (7.9) | 0.017 |

| Cardiovascular Status n (%): | |||||||

| ACS | 135 (47.0) | 73 (38.8) | 62 (62.6) | < 0.001 | 0 | 137 | |

| Stable CAD | 152 (53.0) | 115 (61.2) | 37 (37.4) | 153 | 0 | ||

| Comorbidities n (%): | |||||||

| History of MI | 152 (53.3) | 97 (52.2) | 55 (55.6) | 0.58 | 101 (66.5) | 52 (38.2) | < 0.001 |

| History of ACS | 148 (51.9) | 102 (54.6) | 46 (46.9) | 0.22 | 98 (64.5) | 51 (37.5) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 230 (80.4) | 148 (79.1) | 82 (82.8) | 0.46 | 131 (86.2)) | 101 (73.7) | 0.008 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 238 (82.9) | 155 (82.5) | 83 (83.8) | 0.77 | 142 (92.8) | 99 (72.3) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 97 (34.0) | 53 (28.5) | 44 (44.4) | 0.007 | 51 (33.8) | 47 (34.3) | 0.92 |

| History of CAD | 215 (74.9) | 147 (78.2) | 68 (68.7) | 0.077 | 153 (100) | 64 (46.7) | < 0.001 |

| History of Depression | 73 (25.7) | 33 (17.7) | 40 (40.8) | < 0.001 | 32 (21) | 42 (31) | 0.033 |

| Current Smoker | 75 (26.2) | 41 (21.9) | 34 (34.3) | 0.023 | 25 (16.5) | 51 (37.2) | < 0.001 |

| BDI-II, mean score (±SD) | 8.6 (7.9) | 4.2 (2.9) | 17.0 (7.6) | ||||

| MDD n (%) | 39 (13.6) | 16 (10.5) | 23 (17.8) | 0.078 | |||

| Medication | |||||||

| Aspirin | 287(100) | 188(100) | 99(100) | 153 (100) | 137 (100) | ||

| Clopidogrel | 164 (57.5) | 101 (54.0) | 63 (64.3) | 0.096 | 45 (29.4) | 121 (89.6) | < 0.001 |

| Warfarin | 15 (5.3) | 13 (7.03) | 2 (2.04) | 0.075 | 10 (6.6) | 5 (3.7) | 0.28 |

| Heparin | 93 (32.9) | 51 (27.6) | 42 (42.9) | 0.009 | 0 (0) | 95 (71.4) | < 0.001 |

| CoxII | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| NSAID | 5 (1.8) | 4 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) | 0.494 | 5 (3.27) | 0 (0) | 0.034 |

| ACEI | 144(50.5) | 97 (51.9) | 47 (48.0) | 0.53 | 84 (54.9) | 62 (45.93) | 0.13 |

| Alpha Blocker | 2 (.7) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0.304 | 1 (.65) | 1 (.74) | 0.93 |

| ARB | 35 (12.3) | 26 (13.9) | 9 (9.2) | 0.249 | 25 (16.34) | 10 (7.41) | 0.021 |

| Beta Blockers | 234 (82.1) | 154 (82.4) | 80 (81.6) | 0.88 | 122 (79.7) | 115 (85.2) | 0.23 |

| Calcium Channel | 56 (19.7) | 34 (18.2) | 22 (22.5) | 0.389 | 31 (20.3) | 25 (18.5) | 0.71 |

| Diuretic | 82 (28.8) | 54 (28.9) | 28 (28.6) | 0.957 | 55 (36.0) | 28 (20.7) | 0.004 |

| Other AntiHTN | 14 (4.9) | 5 (2.7) | 9 (9.2) | 0.016 | 4 (2.6) | 10 (7.4) | 0.06 |

| Antianginal | 83 (29.1) | 51 (27.3) | 32 (32.7) | 0.342 | 17 (11.1) | 67 (49.6) | < 0.001 |

| Antiarrhythmic | 14 (4.9) | 11 (5.9) | 3 (3.1) | 0.295 | 11 (7.2) | 3 (2.2) | 0.05 |

| Antilipemic | 268 (94.0) | 179 (95.7) | 89 (90.8) | 0.097 | 145 (94.8) | 126 (93.3) | 0.61 |

| Antiglycemic | 79 (27.7) | 44 (23.5) | 35 (35.7) | 0.029 | 44 (28.8) | 36 (26.7) | 0.69 |

Non-depressed group- BDI<10, Depressed group- BDI ≥ 10, SD - standard deviation; CAD - coronary artery disease; ACS- acute coronary syndrome, BDI-II Beck Depression Inventory-II; BMI-Body Mass Index; MDD- Major Depressive Disorder; COXII-cyclooxygenase II; NSAID- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; ACEI- angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB- angiotensin receptor blocker; AntiHTN- antihypertensive.

Demographic and Risk Factor Differences by Depression Prevalence and Cardiovascular group

The mean BDI-II of the entire group (stable CAD and ACS) was 8.6 with a range of 0-55. Approximately one third of enrolled participants (99 of 287, 34.5%) had at least minimal depressive symptoms (BDI-II ≥ 10) and 13.6% had major depressive disorder (39 of 287). As seen in Table 1, the depressed group (BDI-II ≥ 10) was younger (regardless of sex), had similar racial proportions, had higher BMIs, were less likely to have a history of CAD, were more likely to have ACS (62.6% of depressed patients) and less likely to have stable CAD (37.4%). Depressed participants were more likely to be diabetic (44% in depressed groups vs 28% in non-depressed group) and were more likely to be smokers (34% vs 22%).

As expected, there were differences in clinical features of participants in the stable CAD and ACS groups, as well as the medications used to treat them. ACS patients were younger than the stable CAD group. Men in the ACS group were younger than those in the stable CAD cohort. Participants in the ACS group were more likely to be single and were less likely to have a history of CAD, MI, ACS, or hypertension. Participants in the ACS group were more likely to have a history of depression and to be current smokers. Participants in the ACS group were more likely to be treated with clopidogrel, heparin, and antianginals.

Platelet Serotonin Response

Platelet Activation by Serotonin

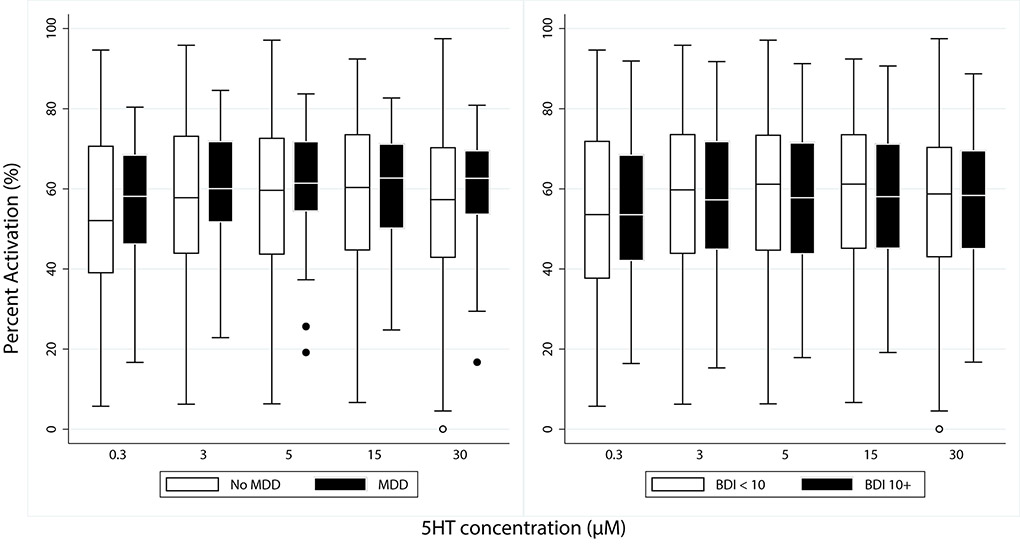

Platelet activation at various concentrations of serotonin as measured by flow cytometry, were not significantly different in patients with MDD or those with depression by BDI (BDI≥ 10) after adjusting for age, sex, and clopidogrel use (Figure 1)(N=131 ACS and 151 stable CAD with BDI; N= 126 ACS and 151 stable CAD with MDD). Trends of platelet activation were similar when BDI was analyzed continuously and when stable CAD and ACS were analyzed separately (supplemental Table 2 - 4).

Figure 1.

Platelet Activation by Serotonin at various concentrations as measured by Flow Cytometry. Results expressed as percent platelet activation with median and 95% confidence interval. Non-depressed group- BDI<10, Depressed group- BDI ≥ 10. MDD- Major Depressive Disorder. BDI- Beck Depression Inventory

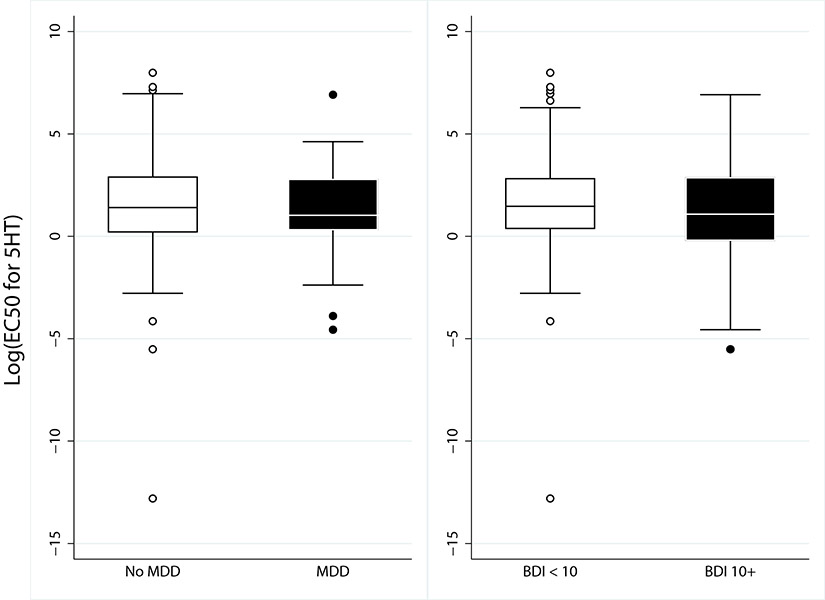

Platelet Aggregation by Augmented Serotonin

When the log of EC50 5HT values were compared, there were no significant differences in patients with MDD or those with depression by BDI (BDI≥ 10) p=0.35 (Figure 2). (N=131 ACS and 151 stable CAD with BDI; N= 126 ACS and 151 stable CAD with MDD, p=0.33). Trends of platelet aggregation was similar when BDI was also analyzed continuously and when stable CAD and ACS were analyzed separately. (supplemental Table 2 - 4).

Figure 2.

Platelet Aggregation by Serotonin. Results expressed as log EC50 5HT (μM) with median and 95% confidence interval. MDD- major depressive disorder, BDI- Beck Depression Inventory, 5HT-Serotonin

We also performed platelet aggregation to arachidonic acid to ensure aspirin effect in all patients. The median and interquartile range in ACS patients was: 3 % (2-5) and for CAD was: 3 % (2-4). Both values indicate appropriate effect of aspirin in both groups. Rank sum p value is 0.063. Supplemental table 1.

Platelet Serotonin Receptor Density

Participants with MDD (n=34) had higher serotonin receptor density compared to those without MDD (n=177), 997.5 ± 840.8 vs 619.3 ± 744.3 fmol/ug (mean±SD), p = 0.009; However when we analyzed stable CAD and ACS separately, this difference was seen only in ACS patients. ACS patients with MDD (N=20) compared to those without MDD (n=83), 1000.5 ± 760.6 vs. 559.8 ± 505.5 fmol/ug, (mean±SD), p= 0.005. Receptor density in stable CAD with MDD (n=14) compared to stable CAD without MDD (n=94) did not reach statistical significance, 993.2± 974.1 vs 671.8± 904.1 fmol/ug, (mean±SD), p=0.37. After adjusting for age, sex, clopidogrel use, smoking, and diabetes using linear regression there remained increased receptor density in patients with MDD although with reduced statistical power (p=0.08); unadjusted data shown in Figure 3. The relationship between receptor density and depression using continuous BDI scores was also assessed. Participants with depression as measured by continuous BDI had a beta coefficient of 0.0158 in the entire group with p value of 0.066. (supplemental Table 4). N indicates all samples processed appropriately after blood draw.

Figure 3.

Serotonin receptor density (fmol/μg). MDD- major depressive disorder

Platelet Serotonin Uptake

Platelet serotonin uptake was not significantly different in patients with depression (BDI≥ 10) [median (interquartile ranges): 2109.00 cpm (687.50 to 3705.86), n=169 compared to those without depression (BDI<10) 1698.50 cpm (831.25 to 3346.84), n=88, rank sum p=0.84]. Although the overall association of serotonin uptake and depression did not reach statistical significance, the interaction between ACS and stable CAD groups was significant, suggesting lower serotonin uptake in depressed ACS patients when compared to depressed stable CAD patients [beta coefficient −0.44 (p=0.018) in ACS, compared to beta coefficient of 0.47 (p=0.10) in CAD]. BDI was also analyzed continuously, the trends of which are similar (supplemental Table 2).

Clinical Follow Up

There were four patients (3 ACS and 1 stable CAD) started on antidepressants at the one month follow up. Two of these four did not have 12-month follow up data and one remained on antidepressants at the 12 month follow up while the other was not on antidepressants at the 12-month follow up (stable CAD patient). There were a total of 14 patients that were on antidepressants by the 12-month follow up (12 ACS and 2 stable CAD).

Patients with BDI≥ 10 experienced significantly more major and minor cardiac adverse events at 12 months after study enrollment. The frequency of major adverse events was 18% in BDI≥ 10 vs 6% in BDI <10 (p=0.010). Odds ratio for major adverse events 3.43 (1.49-7.91) [95% confidence ratio], N=265, p=0.004. The frequency of minor adverse events was 44% in BDI≥ 10 vs 25% in BDI <10 (p=0.004). Odds ratio for minor adverse events 2.42 (1.41-4.13) [95% confidence ratio], N=264, p=0.001. Table 2. Patients with MDD did not have significantly higher frequencies of major (p=0.35) or minor (p=0.98) adverse cardiac events 12 months after study enrollment. Odds ratio for major adverse events 2.18 (0.80-5.92) [95% confidence ratio], N=258, p=0.13. Odds ratio for minor adverse events 1.03 (0.49-2.17) [95% confidence ratio], N=257, p=0.94. We found no evidence that platelet function predicted either major or minor cardiac events. See Supplemental table 7a, b.

Table 2.

Incidence of Major/Minor Adverse Events

| Major Adverse Events | Minor Adverse Events | |

|---|---|---|

| BDI 0-9 | 10/158 (6%) | 39/157 (25%) |

| BDI ≥10 | 14/78 (18%) | 34/78 (44%) |

| p | 0.010 | 0.004 |

| MDD-N | 18/199 (9%) | 61/198 (31%) |

| MDD-Y | 5/34 (15%) | 11/34 (32%) |

| p | 0.35 | 0.98 |

BDI- Beck Depression Inventory, MDD- Major Depressive Disorder.

Platelet Serotonin Response and Cardiac Adverse Events

In analyses restricted to patients with minor adverse events during 12-month follow-up period, we found that these depressed patients (BDI≥ 10) had greater platelet response to serotonin, i.e., the log EC50 5HT was lower by 1.307 log units (95% CI : −2.499 to −0.115, p = 0.032) as compared to non-depressed patients (Table 3). In contrast, for patients who experienced a major cardiovascular event, there was no difference between depressed patients (BDI≥ 10) vs. non-depressed patients in platelet response to serotonin. Similarly, there was also no difference between the presence vs. absence of depression (MDD) in platelet response to serotonin when conducting the analyses in the sub-group of patients who had either minor or major cardiac events.

Table 3.

Platelet Serotonin Response and Cardiac Adverse Events

| BDI ≥10 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet Function | Event Type | Covariate | Beta Coefficient | Standard Error |

p-value |

| Log EC50 Serotonin | Minor adverse | BDI ≥10 | −1.307 [−2.499 to −0.115] |

0.597 | 0.032 |

| Major adverse | BDI ≥10 | −0.922 [−3.148 to 1.304] |

1.060 | 0.40 | |

| MDD | |||||

| Platelet Function | Event Type | Covariate | Beta Coefficient | Standard Error |

p-value |

| Log EC50 Serotonin | Minor adverse | MDD | −0.861 [−2.551 to 0.830] |

0.846 | 0.31 |

| Major adverse | MDD | −1.277 [−3.960 to 1.405] |

1.271 | 0.33 |

BDI- Beck Depression Inventory, MDD- Major Depressive Disorder

Discussion

To date, this is the largest clinical study to explore platelet serotonin signaling in patients with both stable and unstable cardiovascular disease and varying degrees of depression. There are several notable findings of the present study. First, patients with an ACS had a significantly higher prevalence of depression than those with stable CAD. Previous investigators have found a prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms between 31% to 45% in patients with stable CAD, after MI, or with unstable angina, consistent with the prevalence of 34.5% in the present study24. The rate of MDD in our cohort was 13.6%, which is slightly lower than those reported in prior studies (15-20%25-27). However, we excluded patients taking antidepressant medications, which likely contributed to a lower prevalence of MDD in our cohort. Although we found higher prevalence of depression in the ACS group, we did not find direct evidence of greater epinephrine augmented serotonin platelet aggregation or platelet activation to serotonin within 72 hours of initial presentation. Zafar et al., when examining ACS patients 3 months after initial presentation found that those who were depressed and anxious had greater epinephrine-augmented serotonin platelet aggregation. However, the group with depression alone did not have significantly greater platelet aggregation similar to our findings of no significant differences in EC50 to epinephrine-augmented serotonin.28 We did not measure anxiety in our cohort which may possibly provide an explanation of the lack of a positive finding. This study is similar to ours in that they excluded those on antidepressant therapy and as well categorized depression as BDI≥10. Shimbo and colleagues demonstrated greater platelet response to epinephrine-augmented serotonin stimulation in depressed patients without cardiovascular disease.22

Second, we found greater platelet serotonin 2A receptor density in participants with MDD. However, this was primarily driven by higher density in the ACS patients. We further controlled for smoking and diabetes given the high prevalence in the depressed group and found that these variables contribute to some of the higher receptor density in this group given the loss of some of the significance after adjustments. Previous studies have reported increased serotonin receptor density in patients with MDD without cardiovascular disease 29-32. However, another study found decreased platelet serotonin 2A receptor density, as well as decreased hippocampal serotonin 2A receptor density (as measured by positron emission tomography), in patients with major depression.33 Discrepant results in platelet serotonin receptor density were documented in a review by Mendelson,29 however most of the evidence in that review points to increased serotonin 2A receptor density in patients with MDD. After analysis of the data based on continuous BDI there were trends in the similar manner with receptor density i.e. higher serotonin receptor density with higher BDI levels. The serotonin theory in depression is centered on the idea that reduced serotonin signaling is a risk factor in the etiology and/or pathophysiology of major depressive disorder (MDD)34. Pandey et al hypothesized that an increase in the density of platelet 5-HT2A receptors is a biological marker of suicide35. The monoamine-deficiency theory suggests that the underlying pathophysiological basis of depression is a depletion of the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine or dopamine in the central nervous system36. Following this logic, increased receptor density may follow if there is decreased serotonin availability via a negative feedback loop, which is a supposition given that data is lacking in this field.

The most commonly prescribed antidepressants are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that block 5-HT reuptake via the serotonin transporter into neurons and platelets. Langer et al. reported a significant decrease in the Bmax of platelet [3H]-imipramine binding in severely depressed patients indicating evidence of serotonin transporter dysfunction in major depression37. Serotonin uptake is often used as a measure of serotonin transporter function. To date very few studies have measured serotonin uptake and results have been conflicting. Some have reported no significant differences38, 39 and yet others have noted evidence of decreased serotonin uptake in suicidal patients40, 41. We found no significant difference in platelet serotonin uptake between depressed and non-depressed participants when we examined the entire groups of stable and ACS patients, as assessed by BDI and SCID-IV-TR. However when stable CAD and ACS groups were analyzed separately, we found a suggestion of lower serotonin uptake in depressed ACS patients when compared to depressed stable CAD patients. Based on review of the literature, it appears that further investigation using standardized assessment of serotonin uptake could be helpful in advancing the understanding of transporter function in depression and cardiovascular disease. Changes in serotonin reuptake before and after SSRI treatment rather than an absolute threshold for serotonin reuptake may be a more appropriate correlation to perform in depressed patients.

We found that depressed cardiovascular patients had a significantly higher incidence of major and minor cardiac adverse events despite receiving appropriate cardiac treatment, suggesting that clinicians should be vigilant in patients who have both depression and cardiac disease.

We attempted to uncover potential pathophysiologic connections between depression and cardiovascular disease. Patients with MDD who had either minor or major cardiac events at the one year follow up period had no evidence of increased platelet dysfunction. Depressed patients with major adverse follow up events did not have increased platelet response to serotonin. However, depressed patients who had minor adverse events on follow up had evidence of increased response to serotonin. Given that this subgroup cannot be identified a priori, the prognostic implication of such a finding is unclear. Kim et al. have found lower levels of major adverse cardiac events in patients randomized to 24 weeks of escitalopram compared to placebo after an 8-year median follow up after ACS. The study was the first of its kind to demonstrate reduction in MACE.42

Finally, we tried to address the issue of effectiveness of antiplatelet therapy by testing for aspirin response in the entire group and found appropriate aspirin response on presentation.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include the large number of participants and our having assessed serotonin responsiveness in platelets using several methods. Limitations include the low number of depressed individuals. Use of antidepressant medications was exclusionary and, as such, our study sample comprised of patients who generally had low levels of depression. This may be a potential reason for discrepant platelet functional differences. The measurement of platelet serotonin uptake can be complicated and requires careful titration of unlabeled serotonin concentrations, in addition to careful attention to concentrations of fluoxetine and pargyline. Washing platelets reduces the assay quality. Therefore, unwashed platelets should be used. This assay also must be performed at room temperature rather than on ice, which reduces the movement of tritiated serotonin into cells. Once established, the assay can be repeated with good reproducibility. Finally, there is a potential for adjusting for multiple comparisons in a study such as this given the multiple variables measured. In particular when we adjusted for age, sex, clopidogrel use, diabetes and smoking we saw a reduction in the significance in serotonin receptor density. However, our study is descriptive and is intended to be hypothesis generating. Although we did not find overall higher serotonin induced platelet aggregation or activation as measured by flow cytometric analysis in depressed cardiovascular patients, we surmise that this cohort of patients likely has high platelet aggregation and activation simply due to their diagnosis

Conclusion

In conclusion, cardiovascular patients with major depression were found to have increased serotonin receptor density albeit confounded by smoking and diabetes status to some degree. In addition, cardiovascular patients with depression were found to have increased major and minor cardiovascular events at a 12-month follow-up. Overall, our study supports prior clinical observations that the combination of CAD and depression should be cause for clinical concern. The finding of increased platelet response to serotonin in depressed patients with minor adverse cardiac events comes from patient subgroups that are limited by a small sample size, and so the results should be considered hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive and should be used to inform future work. Nevertheless, our results may suggest a potential pathophysiologic connection between cardiovascular patients with increased minor cardiac adverse events that may point to a platelet specific susceptibility to serotonin. We acknowledge that there are several limitations of our current study sample that prevents definitive conclusions. Other factors should be taken into account to explain alterations in platelet function in depression and cardiovascular disease one example is genetic polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter that may help to provide alternative explanations for the mechanisms underlying the interaction between cardiovascular disease and major depressive illness.43-46 Further, assessment of a larger study sample with a higher level of depression may better determine whether there are alterations in serotonin signaling in cardiovascular disease and depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

MS Williams was funded by grant RO1 HL096694 from the United States National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Bethesda, Maryland). D Vaidya was supported by the Johns Hopkins Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Data Management Core. There is no conflict of interest for any author and Dr. Marlene Williams discloses that she serves on the speaker’s bureau of Maryland State Medical Society and Rockpointe Corporation that is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Glossary

- MI

myocardial infarction

- SERT

serotonin transporter

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- SCID-IV-TR

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders

- PRP

platelet-rich plasma

- PPP

platelet-poor plasma

- 5-HT

Serotonin

- BDI-II

Beck Depression Inventory-II

- SSRIs

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

References:

- 1.Musselman DL, Evans DL, Nemeroff CB. The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:580–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Catellier D, Freedland KE, Berkman LF, Watkins LL, Czajkowski SM, Hayano J, Jaffe AS. Depression as a risk factor for mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2003;92:1277–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carney RM, Rich MW, Freedland KE, Saini J, teVelde A, Simeone C, Clark K. Major depressive disorder predicts cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med 1988;50:627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation 1995;91:999–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Dijk MR, Utens EM, Dulfer K, Al-Qezweny MN, van Geuns RJ, Daemen J, van Domburg RT. Depression and anxiety symptoms as predictors of mortality in PCI patients at 10 years of follow-up. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah AJ, Ghasemzadeh N, Zaragoza-Macias E, Patel R, Eapen DJ, Neeland IJ, Pimple PM, Zafari AM, Quyyumi AA, Vaccarino V. Sex and age differences in the association of depression with obstructive coronary artery disease and adverse cardiovascular events. Journal of the American Heart Association 2014;3:e000741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whooley MA, de Jonge P, Vittinghoff E, Otte C, Moos R, Carney RM, Ali S, Dowray S, Na B, Feldman MD, Schiller NB, Browner WS. Depressive symptoms, health behaviors, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. Jama 2008;300:2379–2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson JC, Charlson ME, Wells MT, Altemus M. Depression, coronary artery disease, and physical activity: how much exercise is enough? Clinical therapeutics 2014;36:1518–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziegelstein RC, Parakh K, Sakhuja A, Bhat U. Platelet function in patients with major depression. Internal medicine journal 2009;39:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barefoot JC, Schroll M. Symptoms of depression, acute myocardial infarction, and total mortality in a community sample. Circulation 1996;93:1976–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, Carney RM, Doering LV, Frasure-Smith N, Freedland KE, Jaffe AS, Leifheit-Limson EC, Sheps DS, Vaccarino V, Wulsin L, American Heart Association Statistics Committee of the Council on E, Prevention, the Council on C, Stroke N. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: systematic review and recommendations: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;129:1350–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furie B, Furie BC. Mechanisms of thrombus formation. The New England journal of medicine 2008;359:938–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lv J, Liu F. The Role of Serotonin beyond the Central Nervous System during Embryogenesis. Front Cell Neurosci 2017;11:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayme-Dietrich E, Aubertin-Kirch G, Maroteaux L, Monassier L. Cardiovascular remodeling and the peripheral serotonergic system. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2017;110:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schins A, Honig A, Crijns H, Baur L, Hamulyák K. Increased coronary events in depressed cardiovascular patients: 5-HT2A receptor as missing link? Psychosomatic medicine 2003;65:729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schins A, Hamulyák K, Scharpé S, Lousberg R, Van Melle J, Crijns H, Honig A. Whole blood serotonin and platelet activation in depressed post-myocardial infarction patients. Life sciences 2004;76:637–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendis S, Thygesen K, Kuulasmaa K, Giampaoli S, Mahonen M, Ngu Blackett K, Lisheng L. World Health Organization definition of myocardial infarction: 2008-09 revision. International Journal of Epidemiology 2011;40:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.First MB, Spitzer Robert L, Miriam Gibbon, and Williams Janet B.W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck AT, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). Psychological Corporation 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barth J, Schumacher M, Herrmann-Lingen C. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2004;66:802–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li N, Wallen NH, Ladjevardi M, Hjemdahl P. Effects of serotonin on platelet activation in whole blood. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1997;8:517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimbo D, Child J, Davidson K, Geer E, Osende JI, Reddy S, Dronge A, Fuster V, Badimon JJ. Exaggerated serotonin-mediated platelet reactivity as a possible link in depression and acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol 2002;89:331–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arranz B, Rosel P, Sarró S, Ramirez N, Dueñas R, Cano R, María Sanchez J, San L. Altered platelet serotonin 5-HT2A receptor density but not second messenger inositol trisphosphate levels in drug-free schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Research 2003;118:165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celano CM, Huffman JC. Depression and cardiac disease: a review. Cardiology in review 2011;19:130–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carney RM, Freedland KE. Depression in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Med 2008;121:S20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thombs BD, de Jonge P, Coyne JC, Whooley MA, Frasure-Smith N, Mitchell AJ, Zuidersma M, Eze-Nliam C, Lima BB, Smith CG, Soderlund K, Ziegelstein RC. Depression screening and patient outcomes in cardiovascular care: a systematic review. Jama 2008;300:2161–2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Juneau M, Theroux P. Depression and 1-year prognosis in unstable angina. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1354–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zafar MU, Paz-Yepes M, Shimbo D, Vilahur G, Burg MM, Chaplin W, Fuster V, Davidson KW, Badimon JJ. Anxiety is a better predictor of platelet reactivity in coronary artery disease patients than depression. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1573–1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendelson SD. The current status of the platelet 5-HT(2A) receptor in depression. J Affect Disord 2000;57:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hrdina PD, Bakish D, Chudzik J, Ravindran A, Lapierre YD. Serotonergic markers in platelets of patients with major depression: upregulation of 5-HT2 receptors. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1995;20:11–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheline YI, Bardgett ME, Jackson JL, Newcomer JW, Csernansky JG. Platelet serotonin markers and depressive symptomatology. Biol Psychiatry 1995;37:442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao ML, Hawellek B, Papassotiropoulos A, Deister A, Frahnert C. Upregulation of the platelet Serotonin2A receptor and low blood serotonin in suicidal psychiatric patients. Neuropsychobiology 1998;38:84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mintun MA, Sheline YI, Moerlein SM, Vlassenko AG, Huang Y, Snyder AZ. Decreased hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding in major depressive disorder: in vivo measurement with [18F]altanserin positron emission tomography. Biol Psychiatry 2004;55:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albert PR, Benkelfat C. The neurobiology of depression--revisiting the serotonin hypothesis. II. Genetic, epigenetic and clinical studies. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2013;368:20120535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pandey GN, Pandey SC, Dwivedi Y, Sharma RP, Janicak PG, Davis JM. Platelet serotonin-2A receptors: a potential biological marker for suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:850–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasler G Pathophysiology of depression: do we have any solid evidence of interest to clinicians? World Psychiatry 2010;9:155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langer SZ, Galzin AM, Poirier MF, Loo H, Sechter D, Zarifian E. Association of [3H]-imipramine and [3H]-paroxetine binding with the 5HT transporter in brain and platelets: relevance to studies in depression. J Recept Res 1987;7:499–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meltzer HY, Arora RC. Platelet markers of suicidality. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1986;487:271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy A, Everett D, Pickar D, Paul SM. Platelet tritiated imipramine binding and serotonin uptake in depressed patients and controls. Relationship to plasma cortisol levels before and after dexamethasone administration. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987;44:320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marazziti D, De Leo D, Conti L. Further evidence supporting the role of the serotonin system in suicidal behavior: a preliminary study of suicide attempters. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989;80:322–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marazziti D, Presta S, Silvestri S, Battistini A, Mosti L, Balestri C, Palego L, Conti L. Platelet markers in suicide attempters. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1995;19:375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim JM, Stewart R, Lee YS, Lee HJ, Kim MC, Kim JW, Kang HJ, Bae KY, Kim SW, Shin IS, Hong YJ, Kim JH, Ahn Y, Jeong MH, Yoon JS. Effect of Escitalopram vs Placebo Treatment for Depression on Long-term Cardiac Outcomes in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018;320:350–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldman N, Glei DA, Lin YH, Weinstein M. The serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR): allelic variation and links with depressive symptoms. Depress Anxiety 2010;27:260–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Muller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 1996;274:1527–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uher R, McGuffin P. The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the etiology of depression: 2009 update. Mol Psychiatry 2010;15:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ozdener F, Gulbas Z, Erol K, Ozdemir V. 5-Hydroxytryptamine-2A receptor gene (HTR 2 A) candidate polymorphism (T 102 C): Role for human platelet function under pharmacological challenge ex vivo. Methods and findings in experimental and clinical pharmacology 2005;27:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.