Abstract

Several studies have demonstrated clinical benefits of integrated care for a range of child and adolescent mental health outcomes. However, there is a significant gap between the evidence for efficacy of integrated care interventions vs. their implementation in practice. While several studies have examined large-scale implementation of co-located integrated care for adults, much less is known for children. The goal of this scoping review was to understand how co-located mental health interventions targeting children and adolescents have been implemented and sustained. We systematically searched the literature for interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health that involved a mental health specialist co-located in a primary care setting. We included studies reporting on the following implementation outcomes: acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, penetration, and sustainability. We identified 34 unique studies including randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and survey/mixed method approaches. Components facilitating implementation of on-site integrated behavioral health care included interprofessional communication and collaboration at all stages of implementation; clear protocols to facilitate intervention delivery; and co-employment of integrated care providers by specialty clinics. Some studies found differences in service use by demographic factors, and others reported funding challenges affecting sustainability, warranting further study.

Keywords: integrated care, pediatric, implementation, co-location, utilization, primary care

Introduction

Mental health problems represent the leading cause of disability in childhood and adolescence globally (Erskine et al., 2015), but most children do not receive needed care. (Patel et al., 2007) Barriers to receiving needed services have been described as structural (e.g. lack of providers, insurance, transportation), and perceptual (e.g. explanatory models of mental health problems or about mental health services, including stigma) (Owens et al., 2002). Integration of mental health services into primary care has long been proposed as a way to both overcome these barriers and to more holistically treat and prevent children’s health problems (Ader et al., 2015; WHO, 2003). Recent healthcare transformations have led to the creation of new models and a growing body of literature supporting the efficacy of pediatric integrated care. A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing integrated pediatric behavioral health with usual care (Asarnow et al., 2015) found clinical benefits for a range of emotional and behavioral problems. The strongest effects were seen for collaborative care and for models using treatments with demonstrated efficacy outside of the integrated care setting (e.g., Interpersonal Therapy; CBT for Anxiety, or guideline-based medication protocols), with weaker effects for substance use and preventive interventions.

Models of integration can take many forms, including: 1) primary care providers (PCPs) consult informally with off-site mental health professionals (without direct patient contact); 2) PCPs work collaboratively with off-site mental health professionals; and 3) mental health professionals are co-located at a primary care site (Bower et al. 2001). Co-located models offer potential advantages over other forms of integrated care. Off-site consultative and collaborative models rely more heavily on PCPs to make initial diagnoses and to deliver first-line interventions (WHO, 2007; Wagner, et al., 1996). If specialist mental health care is required, patients must be linked to services, and usually receive them at a different location. In most cases, specialty mental health facilities are not as widely distributed as are primary care sites. Primary care practices may also lack the stigma of sites that are explicitly identified as providing mental health care (Ayalon et al., 2007). Co-location also offers the possibility of so-called “warm handoffs” from primary care to mental health providers and facilitates informal consultation among professionals as well as communication in-person and through a shared medical record. Co-location thus may improve referral success and connection to treatment, since historically referral success rates from primary care to mental health services have been low (Hacker et al., 2006; Rushton et al., 2002).

While co-location offers many potential advantages over other forms of integrated care, it also presents challenges. In larger practices, co-located mental health providers can be readily saturated with visits unless they conduct more targeted, short-term interventions and establish an algorithm or understanding around appropriate referrals with primary care partners. Certain tasks may fall outside the range of care that a mental health provider would provide in a typical outpatient mental health setting, such as: reviewing screening results; conducting “warm handoffs” (meeting with families prior to formal visits); delivering brief interventions; and providing “curbside” consultation to PCPs during clinic hours. Acclimation to the medical environment can present an obstacle to collaboration that is otherwise facilitated by co-location. In addition, including behavioral health providers in team-based care as part of a medical home may both change and increase variability in patient flow (Miller et al., 2001).

Co-located integrated care thus represents an area in which there is a gap between what is known about efficacious treatments and how those can be delivered and sustained in practice (Proctor et al 2009). While several studies have explored large-scale implementation of co-located integrated care for adults (Beck et al., 2018; Katon & Unutzer, 2006; Rossom et al., 2016), much less is known for children. Pediatric and adult primary care differ in many significant ways. Most mental health disorders onset first in childhood, which is a time of rapid development that can be derailed by psychiatric problems. In pediatrics, most medical care received is preventive well child care, and lower levels of emergency and inpatient service use occur during this time (Coker et al., 2013; Sun et al. 2018a; Sun et al. 2018b). Thus, early detection and treatment may be possible centered around frequent well visits, preventing illness progression and off-setting the costs of integrated services (Wissow et al., 2017). Consent for minors is obtained from guardians, and family involvement is generally necessary and critical to treatment success. The epidemiology of child psychiatric disease also differs from adult disorders and changes throughout childhood. Developmental and behavioral disorders such as autism and ADHD are most commonly diagnosed in the earlier years, affecting a preponderance of males. Into adolescence, mood and substance use disorders become more common, and depression occurs more often in females. Onset of psychosis and other severe mental illness tends to occur in late adolescence (Merikangas et al., 2009). In addition, treatment selection and prognosis will often differ from adults even for the same diagnosis, requiring different interventions and expectations.

The goal of this review was to understand how co-located mental health interventions targeting children have been implemented, sustained, and evaluated in the existing literature. We used Proctor and colleagues’ (2009) model for implementation research to extract the barriers and facilitators that studies documented to implementation and sustainability of pediatric co-located integrated mental health interventions. We sought to understand what factors contribute to successful implementation of pediatric integrated care, including characteristics of the care model, inner setting (clinic), outer setting (political/economic/social context), individuals (those participating in intervention design/evaluation/delivery), and implementation processes.

Methods

The protocol for this review was prepared according to Arskey & O’Malley’s (2005) six-stage process for conducting scoping reviews. Scoping reviews are typically undertaken to examine the extent, range, and nature of research in a broad topic area and identify gaps in knowledge. In contrast, systematic reviews focus on more specific topics, study designs, and outcomes. The stages in this process include: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) “charting” the data by extracting information including author, year, setting, intervention type, comparator type, intervention duration, study population, study aims, outcome measures, and important results; (5) collating, summarizing and reporting results; and (6) optional consultation with consumers and practitioners on additional studies to include and insights about the review’s relevance. We modified the charting procedure to include additional measures and concepts relevant to our study. Our team included a pediatrician (SP) and three child psychiatrists (RP, AS, LW) with first-hand experience with co-located pediatric integrated care models. Our team also included a psychologist (AB) and child psychiatrists (RP, LW, MB) with experience designing, implementing and evaluating other types of pediatric integrated care.

Relevant studies and study selection

Study design & population

The search strategy and key words are described in Supplemental Figure 1. We included all peer-reviewed, published evaluations that included systematic data collection and analysis, including qualitative and quantitative data. This included controlled trials, pre-post designs, and qualitative assessments. We included studies targeting participants aged 18 and under with mental health disorders or problems. For studies including adult populations, we included studies if there was a substantial number of participants under the age of 18, and if there was outcome data collected that applied specifically to child mental health problems as opposed to the entire population. We included studies targeting common and severe psychiatric disorders as well as subthreshold mental health problems, but we excluded studies targeting general health behaviors (e.g., adherence to treatment, weight loss).

Interventions & comparison groups

With regard to types of intervention, we included studies that evaluated any program targeting a child mental health problem that involved a mental/behavioral health specialist co-located in a primary care setting. We excluded studies of preventive interventions (i.e., those targeted to well children or those without a recognized mental health problem), given that implementation of these interventions often raises separate challenges. We excluded studies that included co-located medical and mental health providers outside of primary care settings (e.g., community agencies), those that described collaboration between different systems of care, and those that involved primary care and mental health providers working collaboratively but primarily from different locations (e.g. primary care clinic and distinct specialty clinic). We included all studies regardless of whether or not they used a comparison group.

Outcomes

We included studies that evaluated implementation outcomes. We used Proctor et al.’s (2009) framework of implementation outcomes, including: acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, penetration, and sustainability. Table 1 describes definitions and examples for each outcome). We excluded studies that only included patient clinical outcomes without reporting implementation outcomes.

Table 1:

Implementation Outcomes Definitions (from Proctor et al., 2009 & 2011)

| Domain | Explanation | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | Satisfactoriness of intervention among implementation stakeholders (Proctor et al., 2011) | Provider and caregiver satisfaction surveys (e.g.; whether they would recommend co-located model to others) (Adams et al., 2016) |

| Adoption | Uptake of intervention (i.e. decision to try) by participating providers (Proctor et al., 2011) | Number of lectures delivered, indirect consults, direct evaluations & discussions of screening implementation (Goodfriend et al., 2006) Rates of ADHD treatment initiation and completion in intervention vs. TAU arm (Kolko et al., 2014) |

| Appropriateness | Perceived fit or relevance of intervention to the problem & setting (Proctor et al., 2011) | Rates of adherence to AAP recommended timing for medication follow-up attendance vs. control condition (Moore et al., 2018) |

| Feasibility | Usability and usefulness (aka “actual fit”) of intervention within target implementation setting (Karsh, 2004; Proctor et al., 2011) | Duration of time spent with patient by PCP, BHC (Gomez et al., 2014) |

| Fidelity | Extent to which intervention was delivered in the manner in which it was originally prescribed (Proctor et al., 2011; Rabin et al., 2008) | Session audits using Treatment Integrity Rating Form to assess % of module components delivered and adjunctive services delivered (Kolko et al., 2010) |

| Implementation Cost | (Financial) cost of implementing the intervention (Proctor et al., 2011) | PCP revenue on days with vs. without BHC present (Gomez et al., 2014) |

| Penetration | Degree to which intervention spreads throughout the target service setting (Proctor et al., 2011) | Case example of initiative spreading from pilot site to 15 additional sites within health system over 5 years (Schlesinger et al., 2017) |

| Sustainability | Length of time the new intervention is maintained in usual operations (Proctor et al., 2011) | Case example of initiative sustained via clinical billing without grant funding; hospital covering start-up costs (Schlesinger et al., 2017) |

Note: Table adapted from Proctor et al., 2011

Search Methods

We searched the following electronic databases for primary studies: MEDLINE (up to date May 29, 2018): PsycInfo (up to date May 31, 2018); Embase (up to date June 2, 2018), Cochrane (up to date May 17, 2018), and Web of Science (up to date June 2, 2018). The search strategy included keywords related to the following concepts: (a) collaborative or integrated care, (b) children and adolescents, (c) primary care, (d) mental health problems, and (e) implementation outcomes (see Supplementary Table 1 for the sample search strategy for MEDLINE). We also searched the reference lists from articles of interest, including previous systematic reviews on related topics. We excluded studies for which the language of publication was not English.

Data Collection

Two authors independently and in parallel screened the search results for potentially relevant studies based on titles and abstracts; reviewed the full-text articles for final inclusion based on inclusion/exclusion criteria; and extracted data using a structured, standardized electronic data collection form. Disagreements at each stage were resolved through discussion or a third reviewer. We extracted the following data from each included study: author(s), year of publication, study location, study setting (e.g., type of clinic), intervention type and comparator (if any), duration of intervention, study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, patient characteristics (for example, if a subgroup was targeted either by clinical characteristics or by age), provider characteristics (focusing on co-located mental health personnel), primary outcome measure, and implementation outcomes. Where implementation outcomes were unclear (e.g.; whether the outcome could be considered an implementation outcome, which of Proctor’s implementation outcomes was represented by the outcome), at least two members of the study team met to come to consensus.

Data Analysis

Key findings (by study)

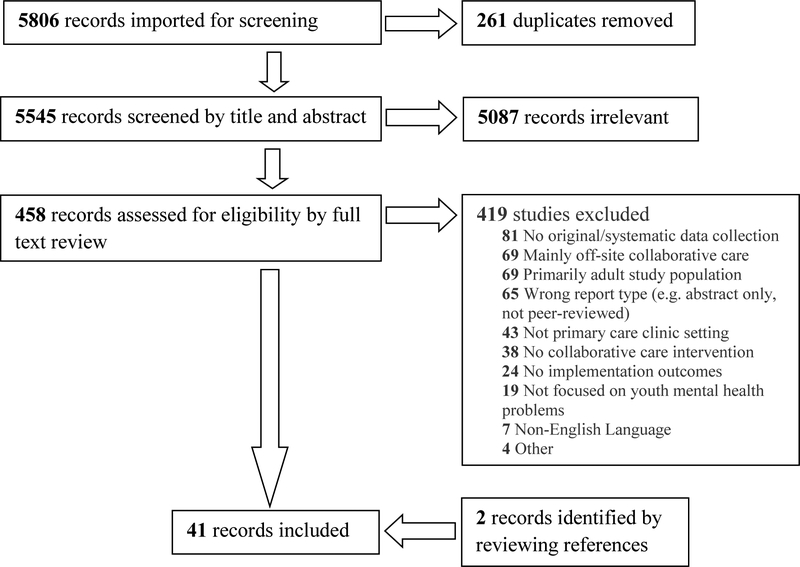

After data abstraction was complete, a group of 3–5 authors reviewed and discussed each study to summarize the “key lesson(s)” on implementation from that study. This process involved reviewing the abstracted data and full-text manuscript, when needed, for each study, identifying implementation outcomes and data quality issues, and developing a consensus on generalizable lessons from the study related to implementation. Once the key lessons on implementation were identified from each study, two members of the study team (RP and AS) worked together to develop a synthesis of findings of included studies using matrices of data contained in Tables 2 and 3 to visually inspect the extracted data and explore relationships within and between studies. We tabulated the sources and flow of studies throughout the review process, including reasons for exclusion, as outlined in the PRISMA statement (Liberati et al., 2009).

Table 2.

Study Characteristics.

| Author Year | Integrated Provider Type and Effort | Specific Intervention Provided | Population targeted | Setting | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams et al, 2016 | 2 school psychology interns at 0.2–0.4 FTE with joint supervision by a licensed University faculty psychologist and the onsite clinic medical director | Level 5 collaboration including warm hand-offs, co-appointments, assessments, triage, consultation, treatment (therapy, parent training, psychoeducation, monitoring of medical treatment), crisis intervention, joint implementation of treatment plans with medical team, coordination of care. | Children and Adolescents | Two urban primary care pediatric clinics serving underserved patient populations including of low socioeconomic status. | Observational, retrospective chart review plus parent/provider survey. |

| Aguirre et al, 2013 | 3 psychiatrists, 1 clinical psychologist, and 2 licensed clinical social workers (all part-time); 1 project director (full-time), 1 administrative director (full-time). Most bilingual (English/Spanish) and affiliated with an academic medical center. | Referrals for children with behavioral health concerns not severe enough to merit off-site referral, provide clinical consultation, crisis stabilization, focused/brief interventions, social services, psychoeducation, billed to insurance or sliding scale. | Children and Adolescents | One family health center in California with about 4,000 patients under 18, 73% Latino, 76% prefer a language other than English, almost 90% live below the federal poverty line, most lack health insurance. | Semi-structured interviews with participating staff (8 members of IBH team and 3 pediatricians) to identify successes and challenges |

|

Briggs et al, 2007 Briggs et al, 2012 |

Licensed Psychologist with infant mental health expertise; 2007 = 0.6 FTE, 2012 FTE not stated | Universal Screening Q6months with ASQ-SE plus referral for on-site psychological assessment, monitoring, and therapy (on-site or home-based), referrals to outside care, provider education. | Infants and preschoolers age 6–36 months | Large urban FQHC affiliated with an academic medical center and training site for 30 pediatric residents. 13 pediatric PCPs, >11,000 pediatric patients, >80% Latino or African-American, >2/3 public insurance. | Observational study (prospective cohort). (N=4954 children). Universal screening with ASQ-SE for ages 6–36 months, intervention and reassessment for positive screens. |

| Briggs et al, 2016 | Child psychologists (1.0 FTE per 5000 patients >=6); Child psychiatrists (1.0 FTE per 20,000 patients); sometimes separate “Healthy Steps Specialists” (training not specified), with regular joint trainings and supervision | Universal Screening (ACES; PHQ-2, ASQ-3, MCHAT-R, ASQ-SE, PSC-17); developmental/behavioral consultation, short term treatment, and/or intensive services with Health Steps Specialist; short-term (4–6 session) evidence-based behavioral health treatment with on-site psychologist; ongoing supervision and training of integrated providers | Children and adolescents of all ages (HS 0–5, PSC 5+) | 19 outpatient ambulatory care practices serving ~ 90,000 pediatric patients per year within academic health system. 1/3 FQHC, almost all NCQA Level 3-certified PCMHs, sites for trainees of multiple disciplines. | Observational study (prospective cohort). Paper also described both internal and external needs assessment |

| German et al., 2017 | Licensed social workers (all 13 sites) workers; new program added some pediatric psychologists (8 sites) and pediatric psychiatrist (4 sites) |

Generalist model: SW trained in Problem-Solving therapy (max 12–14 sessions), conducted range of consultations including for material needs, suicide risk assessments. BHIP model: psychologists trained in evidence-informed modularized approaches to ADHD, anxiety, depression, trauma, disruptive disorders. Psychiatrists provided consultation, education to PCPs and medication initiation. Co-located providers did not treat autism, severe/persistent mental illness, or conduct comprehensive academic evaluations. |

Children age 6–18 years | 13 primary care sites in Bronx New York | Observational Study (prospective cohort) coinciding with the sequential rollout of a new program, comparing 2 models of behavioral health integration (“Generalist” vs. “BHIP”) |

| Godoy et al, 2014 | Clinical psychologists, social workers, and master’s- or PhD-level trainees, each 0.2–0.4 FTE, and “screening assistants” (AmeriCorps) |

Consultation about screening (ASQ, ASQ-SE, ECSA, PEDS, PSC-35) implementation; screening assistance; triage/in-the-moment assessment; evaluation of referred patients | Infants and children age 9 months - 8 years attending well child visits | Pediatric primary care site in Providence, RI (2009–2013) employing 3–4 providers affiliated with a community hospital serving high-risk, low-income, racially and ethnically diverse families. | Observational Study (retrospective cohort). |

| Gomez et al, 2014 | Licensed psychologist, licensed clinical SW, and psychology doctoral trainee. FTE not reported. | Brief Parent management intervention delivered in primary care. Patients included in these analyses were seen for an average of 2.38 visits (SD = 0.74, mode = 2, range 2–4), spaced a median of 4 weeks apart (range 2–8 weeks) | Children age ≤17 years with externalizing behavioral problems and caregivers | PCP office. 1 practice | Observational Study (prospective cohort) evaluating the efficacy of integrated behavioral health care services at two primary care clinics. It included 56 caregivers/child dyads seen for at least 2 behavioral health visits. |

| Goodfriend et al, 2006 | One Child Psychiatrist, 1.0 FTE | Co-evaluation (pediatrician and psychiatrist together), follow-up treatment with either; training for PCPs; phone consultation | Children and adolescents age 0–18 years | Network of urban primary care pediatric practices serving primarily low-income children. 7 of 9 practices in network participated in integrated care and study. Academic Public Health Agency partnership between the University of Florida/Jacksonville and the Duval County Health Department. | Observational Study (Retrospective Cohort). Evaluated for change in PCP practice (diagnoses and treatment) with pre and post billing submissions, number and type of contact between psychiatrist and pediatricians. |

| Gouge et al, 2016 | Two supervised psychology doctoral students, each 0.2 FTE | Warm hand-offs (i.e., on-the-spot referrals in the context of a medical visit); evaluations and brief treatment | Children and adolescents age 3 days to 17 years | Rural, private pediatric primary care practice with 5 PCPs | Observational Study (Prospective cohort). Data collected across a 10-day period when a BHC provided services and 10 days when she did not, N=668. |

| Hacker et al, 2015 | Licensed clinical social workers (one part-time at each of 4 sites), supervised by the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at CHA | BH screening (PSC) and evaluation/consultation/therapy | Children and Adolescents age 4–18 years screened using the PSC | Public hospital and network of affiliated primary care clinics (Cambridge Health Alliance) in Cambridge, MA. 3 outpatient practices. Majority minority patients. | Observational study (Retrospective cohort). Interrupted time series analysis of utilization rates in the months pre and post the BH screening/co-location program implementation. N=11,223 primary care patients at practices in study during time frame. |

| Hine et al, 2017 | Psychology faculty or postdoctoral fellows from the University of Nebraska with specific training in working with children in primary care. FTE not stated. | Not specified | Children and Adolescents | 6 rural primary care pediatric clinics and 5 urban pediatric primary care clinics working in partnership with the University of Nebraska Medical Center. | Survey of pediatrician satisfaction with co-located behavioral health as part of a Program Evaluation of the University of Nebraska Medical Center Behavioral Health Service (N=13 rural and N=14 urban pediatricians) |

| Horwitz et al, 2016 | Child psychologists, child psychiatrists, developmental-behavioral pediatricians, developmental services providers [i.e., early intervention], substance abuse counselors, social workers, child life specialists | Mixed depending on practice | Children and adolescents | General pediatric practices | Survey of pediatric providers: US non-retired members of the AAP in 2013 (N=54,491). The questionnaire was mailed 7 times to a random sample of 1617 members from 7/2013 to 12/2013; 36.7% responded. |

| Kolko et al, 2010 | 2 RN’s with one year of medical-surgical training but no prior mental health training. Each nurse assigned 3 practices; 0.3FTE/nurse/clinic. | Behavioral intervention of 6 modules and 2–4 booster sessions (10 sessions over 3–6 months) (Protocol for On-Site, Nurse-Administered Behavioral Intervention, or PONI) vs. off site referral (enhanced usual care) | Children age 6–11 years with positive PSC-17 Externalizing Problems Subscale. | 6 large urban and suburban primary care offices in metropolitan Pittsburgh, PA. Members of Children’s Community Pediatrics (CCP), a pediatric primary care practice network affiliated with the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. 14% of patients on Medicaid | Randomized Control Trial of intervention vs. enhanced usual care, N=163 |

| Kolko et al, 2012 | Masters-level Case Managers (one social worker, one counselor, and one nurse) each available for 0.4 FTE at each of two sites. | Doctors Office Collaborative Care (DOCC), which included between 6–12 sessions with patient and family using adapted content from “Alternatives for Families: A Cognitive Behavioral Therapy” vs. enhanced usual care (EUC). | Children age 5–12 years with positive PSC-17 Externalizing Problems Subscale. | 4 primary care offices affiliated with a University Hospital | Randomized controlled trial of intervention vs. enhanced usual care, N=78 |

|

Kolko et al, 2014 Yu et al, 2017 |

Masters level social workers as a case manager. Each CM was assigned to 2 practices (1 per condition each) and worked 2 days per week per practice. |

Doctors Office Collaborative Care (DOCC), which included between 6–12 sessions with patient and family using adapted content from “Alternatives for Families: A Cognitive Behavioral Therapy” vs. enhanced usual care (EUC). | Children age 5–12 years with positive PSC-17 Externalizing Problems Subscale. | 7 community pediatric clinics, 1 academic pediatric clinic. Affiliated with a University hospital. | Randomized Control Trial of intervention vs. enhanced usual care, N=321. Retrospective analysis of cost data involving separate consent which included 57 children (25 DOCC vs. 32 EUC). |

| Kozlowski et al, 2015 | Pediatric Nurse Practitioner | Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment (COPE), a 7-session (30 min each) cognitive behavioral skills intervention for anxiety | Children age 8–13 years with diagnosis of anxiety | One rural pediatric practice serving over 26,000 patients, 81.6% below the poverty level | Single-arm pilot study, N=14. |

| Levy et al, 2017 | Social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, developmental-behavioral pediatricians, psychiatric nurse practitioners, art therapist, licensed mental health counselor, special education teacher. ~1 FTE MH/DS for every 4 FTE PCPs. | Varied by setting, included performing developmental assessments, mental health assessments, short-term counseling, facilitating outside referrals, advising and monitoring psychopharmacological treatments, and locating ancillary services. | Children and adolescents | 18 pediatric practices that included a co-located mental health or developmental specialist, including multi-specialty practices (4), hospital-based (6), single specialty (pediatrics) (4), community health center (3), and university health service (1). | Qualitative analysis of interviews with pediatricians in practices identified through the state American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Chapter. |

| Moore et al, 2018 | I=integrated care, C=co-located care. Psychologists (I-1.4, C=0.2), psychiatrist (I=0.1, C=0.1), psychology (I=1.2, C=0.3) and psychiatry fellows (I=0, C=0.2), and psychology interns (C=0.3) | Comparing co-location vs full integrated model in management of ADHD; BHT present in both locations | Children age 6–13 years with ADHD | Resident Teaching clinics similarly staffed (attending, NP) in predominantly poor, urban, minority populations. “Integrated” service had more BHP staffing than “co-located” service. | Observational study. Retrospective case-control study of ADHD assessment and treatment (integrated vs. co-located) in 6–13 year olds. |

| Mufson et al, 2018 | 4 Masters level Social Workers and 7 medical providers, FTE not provided | Stepped Care Interpersonal Psychotherapy Treatment (SCIPT) with two phases: initial 8 weeks of therapy, add fluoxetine after that period of time if not improving, vs. enhanced usual care | Adolescents with MDD, Dysthymia or Depressive Disorder NOS | Urban Pediatric Primary Care. University affiliated. | Randomized Control Trial. n=48, average age 15.9, 38 females, 96% Latino. |

| Olufs et al., 2016 | Licensed psychologist, a postdoctoral psychology fellow, and a predoctoral psychology intern. 0.4 FTE | 2 brief educational “curbside consults” to pediatricians by BHC within integrated care model. Consults included information on assessment and treatment of ADHD, principles of behavioral therapy, etiology of ADHD, common comorbid conditions. | Pediatric patients. Not limited to any specific age or condition, but training focused on ADHD | independently owned suburban pediatric primary care clinic in the U.S. Midwest | Observational, quasi-experimental design, as patient participants assigned based upon referral to the BHC before versus after the brief educational curbside consultation |

|

Rapp et al, 2017 Asarnow et al, 2005 Asarnow et al, 2009 |

Care managers (paid for by study) who were psychotherapists with Master’s or PhD level degrees in mental health fields (MSW, dual MSW and RN degree, MFT, MA in Psychology, or PhD in Psychology), all received training in the study CBT treatment manuals with ongoing consultation and supervision, as well as training in cultural sensitivity, some Spanish-speaking. | Quality improvement (QI) collaborative depression care intervention (vs. enhanced usual care). Care managers support PCPs to assess/manage depression and provide 14-session, manualized CBT. Expert practice leaders at each site oversaw implementation. | Adolescents and young adults age 13–21 years screening positive for depression | 6 primary health care sites affiliated with 5 diverse health care organizations purposely selected to include managed care, public sector, and academic medical centers |

Randomized effectiveness trial to evaluate a QI collaborative depression care intervention compared to enhanced usual care (usually involving specialty referral), N=418. |

| Richardson et al, 2009 | Nurse depression care manager (DCM) with oversight by an on-site child mental health specialist (child psychologist or psychiatrist) | Case management, enhanced patient education about depression and its treatment, encouragement of patient self-management, enhanced antidepressant medication care or Problem-Solving Treatment – Primary Care (PST-PC) based on patient choice, and supervision by child mental health specialist. Adapted from IMPACT for adults. |

Adolescents age 12–18 years with major and minor depression based on PHQ-9 | 3 primary care pediatric clinics within a university-affiliated primary care clinic network in a large metropolitan area in the Pacific Northwest | Single arm pilot study, N=40. |

| Riley et al., 2018 | Psychologists; FTE not described. | Specific interventions not described, but models identified as Coordinated (N=3); Co-located (N=17) and Integrated (N=35) | N/A | Survey distributed through listservs and registry of primary pediatric care training programs | Survey of psychologists on model of integration, billing practices and reimbursement |

| Rousseau et al, 2017 | Child psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, psychoeducators, nurses, art therapists, and others. FTE not provided. | Assessment, treatment, and consultation by specialists (child psychiatrists) | Children and Adolescents | Six community health centers each with a Youth Mental Health (YMH) team plus co-located vs. visitor child psychiatrist in Montreal (Quebec, Canada). Result of government plan reorganizing services to improve access to YMH services. | Mixed-Methods Research Study: On-line survey measuring the association between organizational factors and perception of interprofessional collaboration in YMH teams. Survey completed by 104 team members (62% participation). |

|

Schlesinger et al, 2017 Schlesinger, 2017 |

“Therapists”; Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist (2.0 FTE psychiatrist per 200,000 patients); NPs who “developed behavioral health expertise.” | Short term therapy with oversight and referral pathway to a child psychiatrist. | Children and Adolescents. | Network of 40 financially independent pediatric primary care practices with a central billing office. | Observational Study (retrospective cohort). N not provided. |

| Shippee et al 2018 | Registered Nurse Care Coordinator (RNCC) trained in depression management and MI, FTE not listed; Child/Adolescent Psychiatrist (CAP) available during “designated times,” FTE not listed; LCSW, FTE not listed | Screening & diagnosis by PCP, consultation with CAP or RNCC if diagnostic clarification needed. Usually included warm handoff. Weekly case review with RNCC and CAP, RNCC communicated CAP recs to PCP. RNCC had weekly or biweekly contact with patient either by phone or face to face, and biweekly contact with parents. Psychotherapy/services referrals by LCSW. Patients with comorbidities or not improving seen by CAP. Outcomes tracked with clinical registry. | Adolescents age 12–18 years screening positive for depression on PHQ9, no bipolar | Community pediatric clinic affiliated with large multispecialty practice in the U.S. Midwest | Observational study (retrospective cohort), N=162 intervention participants and 499 eligible non-participants who were propensity score matched. |

| Smith et al, 2016 | 1 psychologist and 3 doctoral level psychology students | Screening of all 4 and 5 year-olds, scored by PCP, positive screens referred to on-site MH provider for 2-session Family Check-Up (FCU) intervention (2–3 sessions including assessment and feedback/intervention) | Parents of children age 4–5 years | 1 primary care pediatric clinic in northeastern Tennessee | Observational Study (retrospective cohort), review of medical record; N=281 eligible for screening, N=22 referred for intervention. |

| Subotsky & Brown, 1990 | Child Psychiatrist, one regular monthly session | Monthly psychiatric evaluation at primary care site. 10 clinics per year offered between 1984–1986. | Children and Adolescents. | Ten GP practices in “an inner urban district” (in London?) owned by the public Health Authority | Observational Study (retrospective cohort) children referred over 3 years (1984–6) to on-site psychiatrist vs. children referred to local mental health clinic (child guidance center), N=50. |

| Talmi et al, 2016 | Team: supervising psychologists (1.0 FTE); psychiatrists (0.3 FTE); psychology trainees (1.3 FTE fellows, 0.2 FTE interns, 0.2 FTE practicum students); psychiatry trainees (0.1 FTE); and one master’s level clinician (1.0 FTE). | Didactics, consultation/screening/treatment, precepting, triage/referrals/coordination of care. | Infants, Children and Adolescents of all ages in the practice (age 0–27 years) | EMR from large academic primary pediatric clinic, 90% Medicaid. | Observational Study (cross-sectional electronic health record review). N=4440 behavioral health patients out of 22,201 pediatric primary care patients. |

|

Valleley et al, 2007 Valleley et al, 2008 |

Psychology faculty or postdoctoral fellows from the University of Nebraska Medical Center. # days per week behavioral clinic operated = 2, 2.5 & 4. | Referral, evaluation and treatment. Collaboration through progress notes, informal hallway consultation, joint sessions with PCPs, some warm handoffs. | Children and adolescents. Mean age of children referred was 7.9 years, 64% male. | 3 rural clinics, 2 Pediatric and 1 Family Practice, with university-affiliated behavioral health clinic on-site. Data from one rural clinic used to evaluate adherence. | Observational Study (retrospective chart review) of patients referred to on-site behavioral health, N=807. A subset from one rural clinic was used for evaluation of session attendance and adherence, N=105. |

| Ward-Zimmerman et al, 2012 | Child Psychologist 0.4 FTE | Psychological Evaluation, short term treatment, treatment recommendations; outside referral if needed | Children and adolescents | Community-based private practice in the greater Bristol CT area; four full-time pediatricians and one part-time developmental pediatrician | Observational Study. (N=96 children/parents referred over 18 months, (outcomes for N=37) in PBHP compared to N=1133 children receiving usual behavioral health specialty care during that time period. |

| Westerlund et al, 2016 | “Health Care (HC) Practitioners” (Midwives and Child Health Nurses) | Training in the International Child Development Program (ICDP) (a parenting program focused on improving parental care competence, parent– child interactions and attachment patterns) for HC Practitioners who were expected to put the program into practice, as well as others involved in implementation, e.g. Community Health Center (CHC) managers and child psychologists |

Parents of children | 10 Health Centers in one Swedish County providing tax-funded healthcare services | Mixed methods case-study using interviews and surveys of informants who participated in intervention implementation (N=82, response rate 89%) |

|

Wright et al, 2016 Richardson et al, 2014 |

Master’s level Clinician (1.0 FTE spread over several primary care clinics) | Depression collaborative care intervention involving an initial 1-hour engagement session followed by selection of pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or both. | Adolescents (age 13–17 years) with depression | 9 primary care clinics in the Group Health System in Washington State. | Randomized Controlled Trial. N=101 youth randomized to ROAD (Reaching Out to Adolescents in Distress) vs. usual care. |

| Yogman et al, 2018 | LICSW (trained in early childhood mental health, psychodynamic theory, and CBT) and a parent partner/care coordinator. LICSW=1 FTE. Coordinator FTE not reported. | Assessment, consultation to PCP, on-site behavioral counseling/CBT, referral off-site for more complex problems, and tracked care coordination. | Children and adolescents age 5–21 years | Private, urban pediatric primary care practice serving predominantly middle-class population, 5% Medicaid. |

Observational study (prospective cohort) of patients referred to program from 7/1/2013 through 3/31/2016, N=366. |

FTE=Full Time Equivalent. PCP=Primary Care Provider. SW=Social Worker. LICSW=Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker. LCSW=Licensed Clinical Social Worker. CBT=Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. BHIP=Behavioral Health Integration Program. IMPACT=Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment. EMR=Electronic Medical Record. BHT=Behavioral Health Therapist. ADHD=Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. FQHC=Federally Qualified Health Center. ACES=Adverse Childhood Experiences Survey. PHQ-2=Patient Health Questionnaire-2. ASQ=Ages & Stages Questionnaire. ASQ-SE=Ages & Stages Questionnaire, Social-Emotional. MCHAT-R=Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised. PSC=Pediatric Symptom Checklist. ECSA=Early Childhood Screening Assessment. PEDS=Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status. MDD=Major Depressive Disorder. PBHP=Pediatric Behavioral Health Program. GP=General Practitioner. PCMH=Patient Centered Medical Home. NCQA=National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Table 3.

Implementation Outcomes of Included Studies.

| Author Year | Main Implementation Outcomes | Results | Study Limitations | Main Implementation Lesson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams et al, 2016 | Acceptability (PCPs and parents) Feasibility (engagement) |

All PCPs (N=8) indicated model ‘very helpful’ for patients, professional development; has ‘greatly improved’ care; enhanced PCP’s knowledge of resources and evidence-based behavioral strategies. All PCPs would ‘definitely’ recommend the model continue, expressed interest in increasing psychologist’s time on site. Most caregivers (N=8 completed survey) reported high (M=4.5 on 5-point scale); services ‘greatly helped my child’s progress’ (M = 4.7/5); problems were improved post-services (M = 4.1/5); relationships with their children were improved (M = 4.4/5). 10 caregivers would ‘definitely’ recommend IBH services to other parents. During study period 37% of scheduled appointments (293/787) did not show or canceled the same day. | Single site, no comparison arm, small number of providers and parents who completed survey | Integrated care is highly acceptable and feasibly, with no lack of patients in need of services, but funding is a major limitation to sustainability, as is the high no show rate (although better than published rates) |

| Aguirre et al, 2013 | Acceptability (PCPs, MHPs) | Pediatricians reported high satisfaction with co-located service availability and quality. Risk assessment/crisis intervention noted as a particular strength of the program. Referrals described by mental health providers as mostly appropriate. Training well-received, both sets of providers interested in more training. Areas for improvement included transitioning patients back to primary care and to specialty care when needed, and communication (also described as an important component of model but limited by part-time employment of PCPs and mental health providers). |

Single site, no comparison arm | Availability for crises, communication, and opportunities for learning highlighted as important components of model. Part-time nature of programs is one barrier to communication. Transitions in care can be difficult even with on-site providers. |

|

Briggs et al, 2007 Briggs et al, 2012 |

Feasibility (engagement) | 2007: 584 screened in 7 months, >200 received some form of follow-up care/contact: 35% intervention from psychologist; 26% assessed via consultation with provider or discussion with caregiver, and determined to be functioning within expected guidelines, but in need of monitoring; 23% referred to another service; 16% declined follow up or did not respond. 100% of patients (N=29) referred to specialty service attended initial evaluation. 2012: 64% of eligible children screened; Of positive screens, 24% received Infant and Toddler Specialist, 22% monitored, 14% referred to outside services (problem too severe), 40% declined services. | Single site, non-randomized, unable to ascertain why screening not completed | Universal screening is challenging and often incomplete. Authors report challenges with questionnaire administration (workflow) leading to some missed screens. Among those who screened positive, 40% did not accept intervention |

| Briggs et al, 2016 | Feasibility (engagement) | Infant/Toddler: Approximately 5–10% of children enrolled in Intensive Services Healthy Steps (comanaged well-child visits, parent support, home visits as needed), 10% received Developmental/Behavioral consults annually. Child/Adolescent: 26.3% of screened children referred to co-located providers. Of those referred, 63% who had a warm handoff attended at least 1 behavioral health session; 53% without warm handoff attended at least 1 session. | Initial feasibility study, did not look at clinical outcomes or implementation outcomes by patient or clinic characteristics. | Warm handoff improved engagement, but still many families may not engage; A relatively large number of patients can be served in co-located model (i.e. 10–15% of 90,000 patient panel received intensive services, 10% developmental/behavioral consult). |

| German et al., 2017 | Acceptability (PCP satisfaction) | BHIP (team) model had 1164 referrals from 4425 health maintenance visits (26.3%). “Generalist” (SW) model had 171 from 1748 health maintenance visits (9.8%). The BHIP model was seen by providers as improving access to and quality of mental health care. PCPs in BHIP practices reported higher satisfaction in time, availability, ease of finding services for patients. No satisfaction differences for nurses or front desk staff. PCPs in BHIP felt more competent managing ADHD and responding to positive behavioral health screen. No other perceived competence differences. | Variability in which the BHIP model was applied across sites | Team based approach (including SW, psychiatrist, Psychologist) may increase referral rates. |

| Godoy et al, 2014 | Feasibility (engagement) | 30.1% did not complete screening due to factors such as staffing problems (i.e., screening assistant not present to facilitate screening) and lack of time. Families of older children more likely to complete screening. Of children screened (n = 664), 140 (21%) received referral or were noted by providers to require follow-up. 134 referred for evaluation with co-located provider. Overall, 54.4% of referred children attended the Triage Assessment appointment. Mental Health Consultant-referred children over 5 years were 2.61 times more likely to attend appointment than children less than 5. Average wait time for consultation was 1 month. | Data primarily parent report, chart review. Observational measures/more parent psychosocial information would augment. | Younger children were the least likely to benefit/engage and more likely to fall through “service delivery gaps” and have unmet mental health needs, even in integrated care. Possible under-recognition by both parents and providers. Authors report that lack of warm handoffs may have contributed to no show rate similar to usual care. |

| Gomez et al, 2014 | Acceptability (parent) Feasibility |

High satisfaction with behavioral health services (M = 3.56 on a 4-point scale, SD =0.63). Satisfaction scores were similar for both child (caregiver report) and adolescent (self-report) patients. Reductions in global distress in parents. 42.9% received services in Spanish. Of Spanish language patients, 33.3% received services from a bilingual therapist and 66.7% were served through a trained interpreter. | No specific practice/provider-level implementation outcomes; Small sample, only looked at participants attending at least 2 BH visits. | Preliminary data here suggests it is possible to provide adapted, flexible delivery of Parent Management Training in the primary care setting, including to a linguistically diverse population. |

| Goodfriend et al, 2006 | Cost Adoption |

Diagnostic evaluations (41.6%) and lectures (21.6%) were the primary types of contacts that constituted the intervention. Ad hoc consultations and discussion of screening instruments represented 23.4% of contacts. All other forms of contact made up less than 5% each of total contacts. Significant increase in Primary Care Provider (PCP) diagnosis of mental health disorders in billing data vs. pre-intervention, with 11–37% increases in diagnostic rates. | Primarily billing outcome data | Increase in PCP adding diagnoses may have implications for billing; While highest percentage (41%) of time was spent in direct patient contact; substantial portions of time still spent w/didactic activities (22%) & indirect consults (23%) |

| Gouge et al, 2016 | Cost Appropriateness (PCP time saved) |

On days when a BHC was present, PCPs spent 2 fewer minutes on average for every patient seen, saw 42% more patients, and collected $1142 more revenue than on days when no BHC present. Comparing visit types, greatest savings occurred for visits identified as “complicated psychiatric,” during which PCPs saved 19.71 minutes per visit on average during BHC days as compared with non-BHC days | Mechanisms of time savings was not explored. Single practice in a provider-shortage area | Demonstrates offset for having BHC in terms of PCP time, costs, time offsets the biggest for complicated cases. Next step might include incorporation of costs of having BHC on-site (this study used doctoral students) and linking to clinical outcomes. Provides information about number of patients seen per day (6). |

| Hacker et al, 2015 | Feasibility (engagement) Cost (implication, related to increased ER visits) |

By the end of post-implementation period, there was a 20.4% increase in specialty BH visit rates (trend = 0.013% per month; p=0.05), and 67.7% increase in behavioral health primary care visit rates (trend = 0.019% per month; p=0.002) compared to the expected rate predicted by the 18-month pre-intervention trend. In addition, behavioral health emergency department(ED) visit rates increased 245% compared to the expected rate (trend = 0.01% per month; p<.001). | Examined the impact of a combined screening and co-location model, not independent impact of each. No comparison group | ED visit increases may be a potential unintended consequence of integration. Increase in specialty BH visits and primary care visits that were labeled as Behavioral Health suggests improvements in identification, access and engagement |

| Hine et al, 2017 | Acceptability (PCP) | PCPs (N=27) reported: (a) improved continuity of care (93%)(b) allowed physicians more free time (85%), (c) decreased cost (70%), (d) increased physical health follow-up (85%), (e) increased physician ability | Single outcome and source (PCP perception). 60% response rate | Of those that responded, large majority thought this was good for the patients (decrease stigma, increase physician expertise, overall improved quality of care) |

| Horwitz et al, 2016 | Adoption | 35% of PCPs (N=321) reported having co-located providers (27% SW, 15% psychologist, 13% psychiatrist, 8% developmental services provider. Co-location more prevalent in: urban vs suburban or rural practices; academic, HMO, government and non-government hospitals and clinics vs 1- to 2-physician practices, pediatric group practices, or multispecialty group practices; practices where PCPs have < 100 ambulatory visits/week; practices where majority of patients non-white; practices where < 80% privately insured. PCPs who received training in Developmental/Behavioral Pediatrics for 4+ weeks more likely to have a co-located provider. Only an on-site SW associated with co-managing. Overall, no association between the percentage of patients with MH problems that pediatricians comanaged and co-location | Low (36.7%) response rate to survey. | Adoption of on-site mental health professionals in pediatrics is increasing, but as of 2013 still only in a minority of practices. Certain types of practices have more readily adopted this model: urban, affiliated with a hospital or medical school, serving low-income patients. Pediatricians did not report increased co-management of patients with on-site mental health providers, working towards increasing co-management is an area of future need. |

| Kolko et al, 2010 | Acceptability (parent, patient, and PCP) Feasibility/Sustainability (time) Fidelity |

PCPs believed highly in the importance of making mental health services available in the PCP office (4.7/5), found few obstacles to providing services (4/5), and expressed interest in collaborating with an on-site clinician (5/5). PCPs enthusiastic with delivery / expansion of the intervention. Caregivers of intervention cases reported greater satisfaction (CSQ-8) and fewer obstacles to treatment on three of the four Barriers to Treatment Participation Scale (BPTS) factors. Many parents noted advantage of on-site services (e.g., acceptable, close to home). High (M= 91%) treatment integrity. | Did not look at clinical comorbidities of behavior problems or effects by patient background, referral source. | Co-location is acceptable, and general medical staff (nurses) can be trained to effectively perform BHC role in this setting with good outcomes (clinical and utilization). |

| Kolko et al, 2012 | Acceptability (PCP and parent) Feasibility (time spent; treatment adherence) Sustainability (commented on, not measured), Appropriate-ness (medication) |

Improvements for intervention (DOCC) over Enhanced Usual Care (EUC) in service use, completion, behavioral and emotional problems, individualized behavioral goals, and overall clinical response. PCPs, parents highly satisfied with DOCC. DOCC children more likely to be rated as improved. Survey responses, coded focus group data from 24 PCPs revealed highly supportive attitudes for DOCC. 71% of caregivers satisfied with their child’s evaluation. 92% of caregivers very willing to receive on-site services to address mental health problems for their children and 71% for themselves. PCPs identified potential barriers to sustainability (e.g., lack of reimbursement or available clinicians), and proposed several solutions (e.g., use of care manager (CM) as a broker of services, education about prescription practices, negotiation with insurers). | Randomization occurred at the individual level, could not conduct ongoing training or programming at the practice level | High provider and parent acceptability: Parent willingness to receive services for themselves in pediatric primary care is significant. Proposals of solution (use of CM, education), Implications for sustainability: gives specific amounts of times needed for providers to implement. Not clear how to pay for the CM. |

|

Kolko et al, 2014 Yu et al, 2017 |

Fidelity Acceptability (patient and PCP) Feasibility (engagement and time required) Cost |

DOCC had higher rates of treatment initiation and completion, improvement in behavior problems, hyperactivity, and internalizing problems, parental stress, goal achievement, and consumer satisfaction. DOCC pediatricians reported greater perceived practice change, efficacy, and skill use to treat ADHD. 90% of all CM-delivered sessions received the highest overall fidelity rating on a 4-point scale. Total costs for DOCC during the 6-month intervention were almost double that for EUC, but average cost per patient was lower for DOCC than EUC (because many more patients in DOCC received mental health treatment). Costs of community mental health services were similar for 6 months pre-intervention, but then DOCC had significantly lower costs in the 6-month intervention period and at 6 and 12 months post-intervention. No significant cost difference at 18 or 24 months post-intervention. | Authors recommended looking at fidelity measures. Primarily white, male patients. Cost analysis (of claims data) included much smaller number of children since it was done retrospectively and not embedded into original trial. | One of the few to report on fidelity organizational social context, and patient and provider acceptability. Also reports on duration of treatment and rate of any mental health (MH) service use. One of the few to report cost analysis. |

| Kozlowski et al, 2015 | Feasibility Acceptability (parent and patient) Cost |

All sessions were reimbursed via time spent counseling. 57% (8/14) completed entire treatment within 3-month evaluation period (some completed in longer period). Parents reported positive experiences on their evaluations with clinical improvement and convenience of treatment in primary care. 1/8 children felt sessions should be >30 minutes. |

Single arm pilot study. Small sample size (N=14). High dropout |

Non-specialist (general pediatric nurse practitioner) can deliver and bill for brief intervention for anxiety after focused 4-hour training. High attrition rate even with brief intervention in integrated setting. |

| Levy et al, 2017 | Acceptability (PCP and BHC), Appropriateness (professional empowerment) and Cost | PCPs (N=18) and BHC (N=18) generally very satisfied with co-location arrangements, citing improved communication, increased opportunities for learning, efficiency, and quality and scope of care, greater comfort asking psychosocial questions, increased patient comfort/convenience, improved adherence and follow-through. 38 % BHC described difficulties with integration into the medical culture. Other challenges: limited access to PCPs due to clinical demands, billing and reimbursement, frustration about PCPs limited understanding of the breadth of co-located provider’s expertise, and space. PCP reported challenges included restricted access to mental health notes, space, billing and insurance, insufficient access even to co-located providers. Only 4 co-located BHCs were able to cover salary and benefits through billing revenue. | Only 23 of 101 practices with co-located providers agreed to be contacted, 1 pediatrician from each site | More needs to be done to promote integration and communication between PCPs and BHCs. Only 4 BHC’s salaries were covered by billing (almost all had to do something else to cover, e.g. medical billing codes, grants, renting space in practice) |

| Moore et al, 2018 | Feasibility Appropriateness |

Higher rates of guideline adherence, more direct contact with schools, and more frequent behavioral observation during clinical encounters among the integrated care model. The integrated care model received more caregiver education on ADHD, behavioral management training, and school advocacy. These associations did not remain after accounting for variance associated with onsite engagement with a psychologist. More families in the integrated practice engaged with a psychologist and attended more frequent medication follow-up appointments. Patients in the integrated setting had better adherence to the AAP recommended timing for medication follow-up attendance than those in the co-located practice, who fell outside the 3–6-month mark. As a retrospective analysis of usual care, integrated care appears to be sustained. | Results dependent on provider documentation, in resident continuity practices. Follow up data collection was infrequent, and it is unclear if follow up was sustained | Higher level of integration was associated with higher fidelity to clinical guidelines. Collection of school data in primary care setting is challenging. |

| Mufson et al, 2018 | Acceptability (PCP and MHP/DS), Feasibility, Fidelity | Participants randomized to intervention attended 10.3/11 (SD 1.43) sessions. All SW and 86% of PCPs reported that the quality of care provided by the treatment model was “good” or “excellent” and indicated they felt either “generally” or “definitively” adequately trained and supported to deliver this treatment model. Medical providers reported the need for improved communication with SW and back-up support with a consulting psychiatrist to implement the model successfully. SW-reported challenges included limited flexibility with manualized treatment, scheduling challenges. Approximately 90% of the rated therapy sessions were rated on a Likert scale as demonstrating satisfactory or better IPT-A competence | Controlled study, ability to deliver/implement in “real world” conditions unknown | Robust implementation outcomes: feasibility, acceptability, fidelity, possible to adhere to manualized treatment even with relatively un-seasoned provider and 1-day provider training seminar. |

| Olufs et al., 2016 | Adoption | 107 referred by the pediatricians at the primary care clinic during two 6-month periods. 89 children (83.2%) attended initial BH appointment. Equal numbers of referrals occurred across the two time periods (54 before, 53 following the consultation); more ADHD referrals post-consultation. Children referred following educational consultation were less likely to have been diagnosed with ADHD prior to the initial BH evaluation. Children referred following the educational consultation less likely to be prescribed medication prior to the initial BH session. More patients received combination treatment for ADHD after the consultation. | Consultations not uniform, single clinic, small sample size. Did identify specific factors mediating increase in referrals/guideline-concordant care | Brief, informal education provided in a “curbside consultation” format may be effective means of PCP education by BHC and increase referrals for the assessment and behavioral treatment of ADHD. |

|

Rapp et al, 2017 Asarnow et al, 2005 Asarnow et al, 2009 |

Acceptability Feasibility (engagement) |

4750 eligible for screening, 84% completed screening. 1034 study-eligible, 418 enrolled, 82% of enrolled completed 6-month follow-up assessment. Overall rates of BH treatment 32% in the intervention group vs. 17% in control (OR 2.8; 95% CI, 1.6 – 4.9; P<.001). Older age, preference for watchful waiting associated with lower treatment rates in Usual Care (UC) but not in Quality Improvement (QI) intervention. Treatment rates higher in QI group only among those who spoke English at home. Treatment more likely among those with: low perceived stigma, previous mental health treatment, higher levels of need. Black youth in QI more likely to receive any counseling (37% vs 18%), specialty mental health care (42% vs 9%). Latino patients, in QI more likely to use specialty mental health care (28% vs. 17%). No significant intervention effects on service use variables for whites. | Model may be challenging to implement/not feasible in some settings; No charge for MH services (may not reflect real-world scenario); Small sample size for whites. Did not describe implementation by site or specific adaptations made by sites. | Additional work needs to be done to increase service engagement of Latino families and treatment-naive individuals, even in integrated care setting. Co-location may address attitudinal barriers (e.g., initial reluctance to obtain active treatment) and be well-received for older age youth |

| Richardson et al, 2009 | Feasibility (engagement) Acceptability (parents, patients, PCP) |

87% completed 6-month intervention. At 6-month follow-up, 74% of youth had a 50% or more reduction in depressive symptoms as measured by the PHQ-9. Parents, youth and physicians indicated high levels of satisfaction with the intervention on written surveys and in qualitative exit interviews. Over the 6-month treatment period, youth had an average of 9 contacts with the DCM (SD=3.2, Range=2–17). Most of these contacts were in person (mean=6.8 per youth (SD=3.5, Range=1–16)) with fewer by phone (mean=3.1 per youth (SD=2.3, Range= 0–9)). There was a significant improvement in depression scores and functional impairment from baseline to six-month follow-up. Parents and youth reported high levels of satisfaction with the intervention in scales and semi-structured exit interviews. | Small sample size, no comparison/control group, population mostly white and female | Collaborative care for adolescent depression is feasible and highly acceptable to adolescents and parents as demonstrated both by self-report and by engagement in the intervention. It is also associated with improved depressive outcomes at similar levels to adult interventions. |

| Riley et al., 2018 | Cost | Use of Health & Behavior (H&B) codes was positively associated with levels of reported coordination and integration, as well as consultation code usage and reimbursement for consultation. Consultation code utilization was positively correlated with estimated percentage of consultations reimbursed. The integrated group reported higher ratings of coordination, colocation and integration than the co-located and the coordinated groups. There was a significant interaction between the reported model of integration and utilization frequency for both H&B and CPT codes. H&B code utilization was significantly higher for integrated than co-located models and CPT code utilization was significantly higher for co-located than coordinated models. | Small sample size, only surveyed psychologists. Practice characteristics and billing practices self-report. Did not ascertain actual dollar amount reimbursed. Availability of reimbursement for H&B. | Models with higher degree of integration may be more financially sustainable. Studies that look at coding practices of other health providers would also be beneficial. |

| Rousseau et al, 2017 | Appropriateness | Co-located child psychiatrists reported higher perceptions of interprofessional collaboration (measured with PINCOM-Q) than visiting child psychiatrists. Communication and organizational culture were predicted by seniority in the team and the co-location model of collaborative care. The co-location model was also a predictor of participants’ perception of having more professional power. | Uneven response rate between institutions/models. Did not measure institutional support of team. Does not distinguish impact of co-location and other components of site organizational cultures. | One of few studies examining BHC perception, experience. Higher interprofessional collaboration and professional power for on-site co-location models |

|

Schlesinger et al, 2017 Schlesinger, 2017 |

Acceptability (provider), adoption, feasibility, penetration, sustainability, cost | Model quickly adopted by pilot practices and expanded to >15 sites (20 therapists, 2 FTE child psychiatrist working with 150 pediatricians) within 5 years and subsequently to pediatric subspecialty and adult clinics. Trainings on empirically supported interventions well-attended by PCPs, led to increase in use of evidence-based interventions. Over 90% of charts reviewed for adolescent well-child visits have the PHQ-9 completed. Show rates >90%. The average number of visits billed/year for a child seen in primary care is less than those in specialty care. Patients engaged in the system were less likely to use acute care visits while maintaining their well-child visits. Therapists schedule 7 patients a day, break even at 5 patients a day, $1 million in savings by maintaining some children within primary care site. Initial start-up costs were supported by the hospital and the system is now entirely supported by third-party billing and the infrastructure of the pediatric practices | No clear methods section or data collection methods reported-more of a case study. | Potential for significant cost-savings, pilot program that rapidly expanded, adoption; supported through billing. However, there were no data collection methods reported in paper, limiting our interpretation of results. Note that being able to rely on billing may vary by patient mix, state policies, etc. Initial start-up costs supported by hospital system highlighting importance of initial institutional buy-in. |

| Shippee et al., 2018 | Feasibility Fidelity Penetration |

Recent public reporting data indicated a 71% rate of mental health screening at well-child visits among this system’s local sites in 2016; EMERALD sites had rates up to 79%. Fidelity to weekly/biweekly contacts: No data on successful and unsuccessful contacts, but unpublished early data - 61% of contacts were successful. Anecdotally (on the basis of internal, non–peer-reviewed data), both adolescents and parents commented that warm hand-offs were important first contacts with the RNCC. Adolescents and parents also commented that it helped to have RNCC calls scheduled around their other commitments. Participants 81% female, 72% white non-Hispanic. | Mainly white non-Hispanic patients. Did not distinguish between effects of different co-located providers (CAP, RNCC, LCSW). No data from providers. Single clinic. | Low rate of male patient participation - authors suggest this warrants further study. |

| Smith et al, 2016 | Feasibility Adoption Penetration |

Screening occurred in 91.4% (N=150) of well child visits and 25% (N=29) of acute visits. 7% (N=19) of those screened were positive screens; 84% (N=16) of positive screens were referred by their PCP to the FCU. Six additional referrals made to FCU based on PCP judgment rather than positive screen. 77.2% (17 of 22) of families referred attended 1 or more sessions. | Single site, small N, no comparison group, late addition of screening | High-level of buy-in/training of staff resulted in high-level of adoption of intervention (i.e., majority of patients screened and majority referred as indicated by positive screening). |

| Subotsky & Brown, 1990 | Feasibility (engagement), Acceptability, penetration | Over 3 years, 50 children were referred to a psychiatric clinic within a health center. Comparing the proportion of those referred who attended, there was a significantly better attendance rate at the health care center than the child guidance clinic. There was a greater proportion of cases seen at the health center being referred by health professionals. A higher proportion of younger children (especially under school age) were seen at the health center than the child guidance clinic. Cases first seen at the health center had a high attendance rate (93%) if they required follow up. | Small sample size, context (1980s) may be of limited applicability to current practices | Attendance at embedded site may increase likelihood that patients/families will attend subsequent specialty clinics. |

| Talmi et al, 2016 | Penetration, Feasibility (engagement) | BHCs saw 4,440 unique patients representing 20% of patient panel. Wide array of presenting problems seen. 5 consultation types: Healthy Steps (6%), pregnancy-related depression (17.7%), developmental (19.2%), mental health (53.2%), and psychopharmacology (5%). Healthy Steps, pregnancy-related depression, developmental and psychopharmacology consults occurred more often for non-Latino white patients compared to Latino patients, while mental health consultation occurred more often for Latino patients compared to non-Latino whites. | Only information that was captured within the medical record could be analyzed. | Lack of diagnostic threshold is a potential hindrance for sustainability because it hinders billing. Differences in service receipt in Latino vs. non-Latino white important to explore further. Authors noted limited bilingual provider supply. |

|

Valleley et al, 2007 Valleley et al, 2008 |

Feasibility (engagement) | Across the three BHCs, nearly 88% of children referred were scheduled for an initial appointment, and 81% of children referred for behavioral health services attended the initial appointment. Families who did not attend the initial appointment waited an average of approximately 44 days as compared with approximately 24 days for those who attended. Majority of families in the subset used to evaluate adherence after initial evaluation (N=105) were lower SES, attended 4 sessions on average, and were unlikely to cancel or no-show. Families were rated by clinicians as following treatment recommendations with “good” integrity. 53% attended all sessions, 44% never cancelled. On average, families brought data (e.g. questionnaires, school reports, symptom tracking) for 59% of sessions attended. | No control group, small sample size and only one clinic for evaluation of adherence, | Rural families do follow through with physician referrals to attend behavioral health services onsite. However, having more systematic process of involving BHC in referral process (e.g., warm handoff) might improve engagement. |

| Ward-Zimmerman et al, 2012 | Feasibility (engagement) | PCPs and nurses (n=9) and parents (n=37) completed satisfaction surveys. 92% reported spending less unscheduled time discussing behavioral health (in visits and on phone) to the co-located behavioral health program. 100% of clinical staff reported the program helped them identify behavioral health problems more quickly, improved quality of patient care, better met patient needs, facilitated community referrals. Regarding the importance of specific factors in deciding to access the program, 100% parents indicated trust in the referring physician, 87% the location, 81% the ease of convincing their child to attend the appointment in the familiar location. 90% of parents reported receiving an appointment as soon as they needed one. No change in health care utilization for children receiving services (3 months before vs. after). | Single clinic. Parent surveys given 7 months after last contact with co-located provider. 41% parent survey participation. 3-month window may not be sufficient to detect changes in health care utilization. | Preliminary program feasibility for private practice setting (majority of other studies in academic settings), referral completion facilitated by having co-located providers also employed by specialty mental health agency/clinic. |

| Westerlund et al, 2016 | Acceptability (provider) Feasibility Adoption Appropriateness |

Participants largely reported believing there was a need for change, motivation to implement the intervention, and positive views of the intervention’s compatibility with existing norms, values and practices. Adherence to existing knowledge on implementation strategies (e.g. development of a comprehensive strategy, clarity on extent of adaptation of intervention protocol to primary care practice setting versus maintaining fidelity to the original protocol communication of vision and goals, communication of and division of roles and responsibilities) was described as “weak.” Insufficient managerial and process support were described. | Some stakeholder interviews were very short. Set in Sweden, where services free and reach nearly all parents during pregnancy and all children age 0–6 years. May be less generalizable to other settings | Underscores importance of clarification of expectations, visions, goals, and expected roles for implementation. Describes need for greater support for the process of implementation of interventions, particularly when expected to be delivered by medical providers within the context of usual care. |

|

Wright et al, 2016; Richardson et al, 2014 |

Cost | Collaborative care adolescent depression model more effective in reducing depressive symptoms, marginally more expensive than usual care. Intervention delivery cost an additional $1475 (95%CI, $1230-$1695) per person. Intervention group had a mean daily utility value of 0.78 (95%CI, 0.75–0.80) vs 0.73 (95%CI, 0.71–0.76) for the usual care group. Net mean difference in effectiveness was 0.04 (95%CI, 0.02–0.09) quality adjusted life-year (QALY) at $883 above usual care. Mean incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was $18,239 (95%CI, dominant to $24,408) per QALY gained, thus intervention resulted in both a net cost savings and a net increase in QALYs. | Predominantly white patient population; set in 9 clinics within single integrated health care organization, did not compare between clinics | Integrated care intervention for adolescent depression resulted in net cost savings and net increase in QALYs, suggesting cost effectiveness. |

| Yogman et al, 2018 | Acceptability (patients and PCPs), Cost, Penetration, Feasibility | 16% of patients in practice received direct services over a 2-year period. Provider surveys (N=9 providers) found: increase in perception of family-centeredness (using Family Centered Care Assessment Self-Assessment). Pre-post intervention data showed physicians were more successful treating psychosocial problems, more efficient, and less burdened compared to pre-intervention. The practice showed improvement in every area (proficiency, engagement functionality, rigidity, resistance, stress) of Organizational Social Context profile. Registries created and showed some impact on most screening tool measures. Large median decreases in median monthly spending/patient largest for comorbid Behavioral Health and Complex Special Healthcare Needs (87%); overall decreased by 64%; Notes barriers including low per-service payments, non-billable services including handoffs, assessments, coordination, “collateral care” and telephone calls all of which thought to be important. | No control group, pre-post study. Varying sample size, with some small (e.g., 12 parents completed family experience scales, only post-intervention). Cost date only available for commercial risk contracts. Qualitative data mentioned but not described in results. | Feasibility and acceptability of model in private practice setting. Potential organizational and family-centered care improvements. Potential for cost improvements, particularly for more complex patients |

PCP=Primary Care Provider. BHC=Behavioral Health Clinician or Consultant. BH=Behavioral Health. MHP=Mental Health Provider. DS=Developmental Specialist. CI=Confidence Interval. QALY=Quality Adjusted Life Years. SW = Social Worker. BHIP=Behavioral Health Integration Program. PINCOM-Q=Perception of Interprofessional Collaboration Model Questionnaire. PHQ-9=Patient Health Questionnaire. ADHD=Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. SES=Socioeconomic Status. FCU=Family Check-Up. CSQ-8=Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8. DOCC=Doctor-Office Collaborative Care. EMERALD=Early Management and Evidence-based Recognition of Adolescents Living with Depression. CAP=Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist. RNCC=Registered Nurse Care Coordinator. LCSW=Licensed Clinical Social Worker. LICSW=Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker. DCM=Depression Care Manager.

Results

Summary of included studies