Abstract

Purines represent a class of essential metabolites produced by the cell to maintain cellular homeostasis and facilitate cell proliferation. In times of high purine demand, the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway is activated; however, the mechanisms that facilitate this process are largely unknown. One plausible mechanism is through intracellular signaling, which results in enzymes within the pathway becoming post-translationally modified to enhance their individual enzyme activities and the overall pathway metabolic flux. Here, we employ a proteomic strategy to investigate the extent to which de novo purine biosynthetic pathway enzymes are post-translationally modified in 293T cells. We identified 7 post-translational modifications on 135 residues across the 6 human pathway enzymes. We further asked whether there were differences in the post-translational modification state of each pathway enzyme isolated from cells cultured in the presence or absence of purines. Of the 174 assigned modifications, 67% of them were only detected in one experimental growth condition in which a significant number of serine and threonine phosphorylations were noted. A survey of the most-probable kinases responsible for these phosphorylation events uncovered a likely AKT phosphorylation site at residue Thr397 of PPAT, which was only detected in cells under purine-supplemented growth conditions. These data suggest that this modification might alter enzyme activity or modulate its interaction(s) with downstream pathway enzymes. Together, these findings propose a role for post-translational modifications in pathway regulation and activation to meet intracellular purine demand.

Keywords: de novo purine biosynthesis, metabolism, post-translational modification, PTM, AKT, phosphorylation

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cellular metabolism is the collection of biochemical transformations that convert nutrients into the necessary energy and biomolecules to sustain cell survival and promote proliferation. Purines represent a large class of biomolecules that encompass the building blocks for the transfer of genetic information, energy supply, cofactors for enzymatic reactions, and regulators of signal transduction. The production of purine nucleotides is achieved through a fine balance between purine metabolic pathways associated with purine biosynthesis, recycling, and degradation. Under normal cell growth conditions, the salvage pathway predominates, where degraded adenine and guanine bases are reincorporated into phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) to generate their corresponding nucleotide. When the cell senses high purine demand, such as in the G1 phase of the cell cycle or in several disease states, the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway becomes activated.1,2 In humans, the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway is an energy-intensive process that converts PRPP into inosine 5’-monophosphate (IMP) through 10 chemical steps catalyzed by six enzymes (Figure S1A).

Enzymes within the de novo purine biosynthesis have been postulated to be highly regulated for efficient purine production. The first enzyme in the pathway is amidophos-phoribosyltransferase (PPAT), is subjected to feedback inhibition by nucleotides, and has been hypothesized to be rate-limiting.3–6 PPAT is activated by the proteolytic cleavage of the first 11 residues, and its activity decreased upon the oxidation of a bound [4Fe-4S] cluster.7‘8 Recently, PPAT and formylglycinamidine ribonuleotide synthase (PFAS) were shown to be under the regulation of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), whereby inhibition of HSP90 with ganetespib resulted in a marked decrease in their interaction with HSP90 and enhanced proteolytic degradation.9 Moreover, the oligomeric state of these pathway enzymes might further impact their catalytic activity. For example, the last enzyme in the pathway, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase/IMP cyclohydrolase (ATIC), is known to exist in a monomer-dimer equilibrium, in which the dimer interface serves as the active site for its substrate, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR), and is necessary for transformylase activity.10‘11

Last, intracellular phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling has also been long associated with regulating the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway. Epidermal and keratinocyte growth-factor-mediated AKT activation was shown to increase the mRNA expression of phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase (PRSP) and adenylosuccinate lyase (ADSL) in quiescent human HaCaT keratinocytes.12 PRSP is responsible for generating PRPP and is subject to feedback inhibition to regulate the availability of PRPP, the rate-limiting substrate for purine metabolic pathways,13‘14 whereas ADSL catalyzes a reversible reaction in the de novo pathway. Together, these up-regulation events might contribute to an increase in the metabolic flux of IMP through the pathway. When AKT was inhibited by MK2206 in HeLa cells, a 73% reduction in purine production was observed.15 Further interrogation of PI3K and AKT’s involvement in purine metabolism revealed both an early and late stage pathway control mechanism.16 In early stages of pathway regulation, AKT activates transketolase, and thereby increases PRPP substrate generation through the non-oxidative pentose phosphate shunt.15,16 In late-stage de novo purine biosynthesis, inhibition of PI3K with LY294002 resulted in a 20% reduction in ATIC activity in C2C12 mouse mesenchymal cells.16

Downstream of PI3K/AKT is an emerging regulator of purine metabolism—mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin resulted in a decrease in activating transcription factor (ATF) 4-mediated transcription of MTHFD2 and purine production through the de novo pathway.17 Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2 (MTHFD2) is localized to mitochondria and leads to the conversion of 10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate into tetrahydrofolate, resulting in formate release from mitochondria. This cytosolic formate then is processed back into 10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate to serve as a necessary cofactor for the trifunctional enzyme composed of glycinamide ribonucleotide (GAR) synthetase/ GAR transformylase/5-aminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase (GART) and ATIC transformylase activities. mTOR activity is regulated, in part, by the energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK is activated when purine synthesis is altered, either by a decrease in intracellular ATP or by an increase in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway intermediate AICAR. AMPK activation results in the phosphorylation of tuberin (TSC2) and Raptor, both components of the rapamycin-sensitive mTOR complex 1, to impede mTOR function.18–20

Other than the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway has also been shown to be impacted by casein kinase 2 (CK2). Based on substrate motifs, the first three enzymes in the pathway (PPAT, GART, and PFAS) have been proposed as CK2 substrates.21 Chemical inhibition of CK2 resulted in the formation of a multi-enzyme cluster called the purinosome and showed a 1.5-fold increase in IMP production.21,22 A short-hairpin RNA loss-of-function kinome screen also revealed kinases other than AKT and mTOR that are associated with changes in purinosome biomass, suggestive of complex assembly or disassembly; however, the impact of these kinases on purine metabolism is largely unknown.23

To date, most of our understanding of the molecular events that result in activation of the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway are due to increases in substrate and cofactor availability. To our knowledge, no one has asked whether the enzymes in the pathway are also regulated by post-translational modifications (PTMs). Here, we present the first attempt at mapping the PTMs of enzymes within the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway. Novel modifications, not previously observed by high-throughput global proteomic studies, were further analyzed to address whether there is an overall preference for a subset of modifications observed either under purine depleted or supplemented growth conditions previously shown to modulate pathway activation. One such novel modification includes the phosphorylation of Thr397 on PPAT. This residue was shown to be phosphorylated by AKT. This example along with other kinase substrate predictions provide further connections that link the PI3K/AKT and other signaling pathways to de novo purine biosynthesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

293T Homo sapiens embryonic kidney cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. MagStrep “type 3” XT beads were purchased from IBA GmbH. Peptides were purchased from GenScript at >85% purity with an N-terminal biotin-aminohexanoic acid linker and used without further purification. Active AKT (specific activity: 103 nmol/min/mg using CKRPRAASFAE as a peptide substrate) was purchased from SignalChem. All high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade solvents and chemicals for LC-MS/MS peptide sequencing analysis were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sequencing grade trypsin was from Promega.

Cloning of 2×Strep-tag II Mammalian Expression Plasmids

From mammalian expression plasmids expressing EGFP fusion chimeras of PPAT (NP_002694.3), GART (NP_000810.1), PFAS (NP_036525.1), PAICS (NP_006443.1), ADSL (NP_000017.1), and ATIC (NP_004035.2),24 mEGFP was digested out (PPAT: KpnI/NotI; GART: XhoI/NotI; PFAS, ADSL: AgeI/NotI; PAICS: XhoI/KpnI, ATIC: NheI/BamHI) and a duplex oligonucleotide for a 2×Step-tag II affinity tag with appropriate overhangs was ligated in to afford 2×Strep-tag II-tagged protein chimeras. Enhanced protein expression was achieved by cloning the newly formed gene encoding the fusion protein and ligating the gene fusion into a pCI-neo vector (Clontech). All constructs were expressed with a C-terminal 2×Strep-tag II affinity tag with the exception of ATIC, where the tag was placed on the N-terminus to avoid issues with protein dimerization. Resulting amino acid sequences of the 2×Strep-tagged fusion are shown in Table S1. For PPAT phosphorylation assays, the PPAT-2×Strep-tag II construct was modified to reflect the active state of the enzyme, wherein the first 11 amino acids were removed. All constructs were sequence verified by Sanger sequencing, and their expression evaluated by Western blot (Figure S2A).

Mammalian Cell Culture

293T H. sapiens embryonic kidney cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologics, Flowery Branch, GA) and 2 mM GlutaMAX (Gibco). For 293T cells grown under purine-depleted growth conditions, the cells were transitioned for at least three passages into DMEM with 10% (v/v) dialyzed fetal bovine serum and 2 mM GlutaMAX. Dialyzed fetal bovine serum was prepared by extensively dialyzing fetal bovine serum for 3 days against 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride in water using a 10 kDa molecular-weight cut-off Spectra/Por dialysis membrane (Spectrum Labs).

Transfection of 293T Cells for Mammalian Protein Expression

A single day prior to transfection, 293T cells grown in either normal or purine-depleted growth medium were seeded at 2–3 × 106 cells in a 10 cm dish. For PPAT and PFAS expression, 4-10 cm dishes were prepared; GART, PAICS, and ADSL required 2 10 cm dishes, and only 1 10 cm dish was needed for ATIC. An 80–90% confluent culture of 293T cells were transfected with 24.0 μg of pCI-neo-Strep-tag II plasmid in a 1:2.5 ratio with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as according to manufacturer’s protocol. A total of 6 hours post-transfection, the medium was exchanged for with normal or purine-depleted DMEM. Mammalian expression of the Strep-tag II fusion proteins was allowed to proceed for 48 h at 37 °C in an incubator supplied with 5% carbon dioxide.

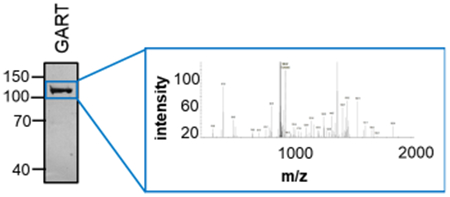

Western Blot Analysis of 2×Strep-Tagged Constructs

To assess protein expression of the 2×Strep-tagged fusions, 293T cells grown in normal medium were seeded at 4 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate. At 70–80% confluency, cells were transfected with 4.0 μg of pCI-neo-Strep-tag II plasmid in a 1:2.5 ratio with Lipofectamine 2000 as according to manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 h of expression, cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed once with 1× Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), and lysed in 100 μL of lysis buffer [50 mM sodium phosphate dibasic pH 8.0, 300 mM sodium chloride, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1× Halt phosphatase inhibitor single-use cocktail (Thermo-Fisher Scientific), and 1× Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher Scientific)] for 30 min on ice. Soluble lysate (40 μg for PPAT and PFAS detection and 30 μg for remaining proteins) was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, 8% polyacrylamide gel), transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed for the presence of PPAT (LifeSpan Biosciences, catalog no.: LSC80815), GART (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no.: A304-311A), PFAS (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no.: A304-220A), PAICS (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no.: A304-546A), ADSL (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no.: A304-778A), or ATIC (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no.: A304-271A).

Recombinant Protein Purification

Transfected 293T cells were harvested by trypsinization and washed once with 1× DPBS prior to lysis for 30 min at 4 °C in lysis buffer (see above). The 2×Strep-tag II fusion proteins were purified from the crude lysates using immobilized MagStrep “type 3” XT beads following the manufacturer’s protocol. Eluted protein was separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide gel), and visualized by silver staining (Figure S2C). Each experimental condition included three biological replicates of approximately 1-20 μg of recombinant protein.

PTM Analysis of Purified Purinosome Proteins

PTMs on individual 2×Strep-tagged purinosome proteins were identified using peptide sequencing by mass spectrometry. Samples were prepared by in gel digestion with trypsin following the UCSF Mass Spectrometry Facility protocol (http://msf.ucsf.edu/protocols.html). Briefly, gel bands were diced into small cubes and then washed or destained twice with 50:50 acetonitrile (ACN)/25 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) solution. Samples were reduced with 5 mM dithiothreitol in ABC for 30 min at 56 °C and then alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide in ABC for 1 h in the dark at room temperature. Samples were washed again twice with 50:50 ACN/ABC, and the solvent was removed prior to the addition of trypsin in ABC at 1 μg of trypsin for every 50 μg protein sample for overnight digestion at room temperature. Samples were extracted twice from the gel pieces with 50:50 ACN/0.1% formic acid. Peptide extracts were dried under a vacuum and then resuspended in 0.1% formic acid for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis.

Peptides were sequenced using an LTQ OrbitrapXL mass spectrometer (Thermo), coupled to a 10 000 psi nano-Acuity UPLC system (Waters) for reverse-phase separation on a C18 EZSpray column (Thermo, 75 μm i.d. × 15 cm, 3 μm bead size, 100 Å pore size). Peptides were separated over 60 min using a linear gradient of 2-30% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid at a 300 nL/min flow rate. Survey scans were acquired at 30 000 resolution in the FT over a 325-1500 m/z range followed by collision induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation scans of the six most intense ions, measured in the linear ion trap using a threshold of 1000 counts, 2.0 m/z isolation width, 30% normalized collision energy, and 30 μs activation time. The polydimethylcyclosiloxane ion with m/z = 445.120025 was used for internal calibration of both precursor and fragmentation scans.

Mass spectrometry peak lists were generated with an in house script called PAVA, and data were searched with UCSF software Protein Prospector, v. 5.19.1.25 Data were searched with a database of SwissProt human sequences (downloaded December 1, 2015) plus background proteins (BSA, trypsin, and streptavidin), containing 20 194 sequences. A randomized decoy database of 20 194 sequences was used for the estimation of false discovery rate.26 Data were also searched against the authentic sequences of each recombinant protein. Mass accuracy tolerance was 20 ppm and 0.6 Da for the precursor and fragment scans, respectively. Data searches allowed up to two missed cleavages, and the following modifications: the carbamidomethylation of Cys was a fixed modification, and variable modifications included oxidized Met, pyroglutamate from N-terminal Gln, start Met processing, acetylation of the N-terminus, phosphorylation of Ser/Thr/ Tyr, mono- or dimethylation of Lys, mono-methylation of Arg, acetylation of Lys, succinimidylation of Lys, and GlyGly modification of Lys as a mark for ubiquitination. Protein and peptide false discovery rates were <1%, with Protein Prospector minimum protein and peptide scores of 22 and 15, respectively, and with maximum expectation values of 0.01 for protein and 0.0001 for peptides. PTM species are reported from Protein Prospector with site localization “SLIP” scores; a SLIP score ≥6 has a 95% confidence in unambiguous site assignment.27 All PTM spectra reported were visually inspected. Raw mass spectrometry data files are available at ProteoSAFE (http://massive.ucsd.edu) with accession no. MSV000082496. Post-translationally modified peptide spectral assignments may be viewed with the freely available software MS Viewer, accessible through the Protein Prospector software suite (http://msviewer.ucsf.edu/prospector/mshome.htm) with search key togmt9nbds.

Metabolic Flux Analysis

A single day prior to metabolite extraction, purine supplemented and depleted 293T cells, grown in DMEM, were seeded at roughly 2 × 106 cells per 10 cm dish. A total of 4 hours prior to labeling, cell medium was exchanged for minimum essential medium (MEM, Mediatech, Inc.) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS or dialyzed FBS (purine supplemented or depleted, respectively). Cells were incubated with either purine-supplemented or -depleted MEM supplemented with 10 mg/L 15N-glycine (Sigma-Aldrich, 10 mL per 10 cm dish) for 4 h. After 4 h, the cells were harvested and washed three times with DPBS. Metabolites were extracted from the cell pellets using 0.5 mL of ice-cold 80% (v/v) methanol in water. Each sample was vortexed for 10 s, snap-frozen for 10 s, and thawed on ice for 10 min on ice. A total of 3 freeze—thaw cycles were performed before the sample was centrifuged at 3000g for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was transferred to a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube. Each pellet was resuspended 3 times in 200 μL of ice cold 80% (v/v) methanol in water and centrifuged at 3000g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was added to the 2 mL microcentrifuge tube. The combined supernatant was centrifuged at 10000g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was dried down and reconstituted in 3% (v/v) methanol in 1 μM chlorpropamide (internal standard for instrument performance) prepared in water.

Metabolite samples were analyzed by LC—MS using a modified version of an ion pairing reverse-phase negative ion electrospray ionization method.28 Samples were separated on a Phenomenex Synergi Hydro-RP C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 2.5 μm particle size) using a water—methanol gradient. The LC—MS platform consisted of a Dionex Ultimate 3000 quaternary HPLC pump, a Dionex 3000 column compartment, a Dionex 3000 autosampler, and an Exactive Plus Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer controlled by Xcalibur 2.2 software. The HPLC column was maintained at 30 °C and a flow rate of 200 μL/min. Solvent A was 3% (v/v) aqueous methanol with 10 mM tributylamine and 15 mM acetic acid; solvent B was methanol. The gradient was 0.0 min at 0% solvent B; 5.0 min at 20% solvent B; 7.5 min at 20% solvent B; 13 min at 55% solvent B; 15.5 min at 95% solvent B; 18.5 min at 95% solvent B; 19.0 min at0% solvent B; 25 min at 0% solvent B. The Exactive Plus was operated in negative ion mode at a maximum resolution (140 000) and scanned from 70 to 1000 m/z.

Peak areas for 15N-incorporated AMP were normalized by using the peak area of the corresponding 13C-incorporated purine metabolite. 15N-incorporation is represented as a mean plus or minus the standard deviation, with N = 4 independent samples. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism, v. 8.0.0.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

Phosphorylation reactions were performed by incubating biotinylated peptide substrates with AKT1 at 30 °C for 2 h. For these assays, a phosphorylatable and a control non-phosphorylatable peptide was synthesized with an N-terminal biotin and aminohexanoic acid (Ahx) linker: T397tide (biotin-Ahx-IVRGNTISPI) and T397A-tide (biotin-Ahx-IVRGNAIS-PI). Various amounts (0-80 ng) of AKT1 (SignalChem) were incubated with 100 μM biotinylated peptide substrate (T397-tide or T397A-tide) before the reaction was initiated with 100 μM ATP spiked with 0.069 μCi of [γ-32P]-ATP (Perkin Elmer). All reactions were terminated by addition of 7.5 M guanidine hydrochloride to a final concentration of 2.5 M and 15 μL of the resulting mixture was spotted on a SAM2 biotin capture membrane (Promega). The membrane was washed for 30 seconds with 2 M sodium chloride, 3 times for 2 min each with 2 M sodium chloride, 4 times for 2 min each with 2 M sodium chloride in 1% (v/v) phosphoric acid, and 2 for 30 seconds each with deionized water. The membrane was allowed to dry on a piece of aluminum foil at room temperature for 1 h prior to imaging. Dot intensities were quantified using ImageQuant and represented as mean plus or minus the standard error of the mean with N = 3 independent assays. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism, v. 8.0.0.

For in vitro AKT phosphorylation assays of recombinant PPAT, PPAT (without the first 11 residues) was expressed as a 2×Strep-tagged fusion for 48 h in a 10 cm dish of purine-depleted 293T cells and purified from 1 mL of crude lysate using 30 μL of immobilized MagStrep “type 3” XT beads for 16 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed 4 times with wash buffer [50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 150 mM sodium chloride, 2 mM EDTA, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100] and another 4 times with kinase assay buffer [25 mM MOPS pH 7.2, 12.5 mM β-glycerol-phosphate, 25 mM magnesium chloride, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM EDTA, and fresh 0.25 mM DTT]. Beads were resuspended in 300 μL of kinase assay buffer. For each reaction, ATP was added to 50 μL of the resin slurry to a final concentration of 100 μM. The reaction was initiated by addition of 100 ng of active AKT1. The reaction proceeded for the designated length of time on a rotating mixer, to ensure the resin remained suspended, at 30 °C before the reaction was terminated (washed once with kinase assay buffer and heat denatured in 25 μL of SDS loading dye). The entire reaction mixture was loaded on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to PVDF membrane, and probed for the phospho-AKT substrate motif (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no.: 9614) and PPAT (LifeSpan Biosciences, catalog no.: LS-B9407).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of PTMs on de Novo Purine Biosynthetic Enzymes

A mass spectrometry approach was applied to identify the extent to which each of the six de novo purine biosynthetic enzymes are post-translationally modified. Using 293T cells, 2×Strep-tag II (2 × Strep) affinity labeled enzymes were transiently expressed for 48 h, affinity purified using an engineered form of streptavidin, and trypsin-digested (Figure S2). Strep is an eight amino acid tag used for the purification of recombinant proteins from mammalian cells and has been used for protein and post-translational modification detection in mass spectrometry.29–31 Mass-spectrometry-based peptide sequencing of the enzymes yielded complete coverage (>99%) for the bifunctional enzyme carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthase/succinoaminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide synthetase (PAICS), ADSL, and ATIC and nearly complete coverage for PPAT, GART, and PFAS (90%, 86%, and 92%, respectively). Additionally, endogenous proteins were shown to co-purify with their 2×Strep transiently expressed cognates, suggesting that the affinity tag does not alter the quaternary structure of the enzyme. The copurification is in agreement with what is currently known about the oligomeric nature of these proteins. Endogenous N-terminal acetylated and start-Met processed peptides were detected for ATIC (1MAPGQLALFSVSDK14), consistent with the natural start site. This enzyme was 2×Strep-tagged at its N-terminus to minimize disruption of its functional dimer. All other enzymes studied were expressed as C-terminal 2×Strep fusions, and peptides were detected for the native termini of GART (terminating at Glu1010), PAICS (terminating at Leu425), and PPAT (terminating with Trp517) (Table S2). However, similar conclusions about ADSL and PFAS cannot be made because no native C-terminal peptides were identified to these proteins.

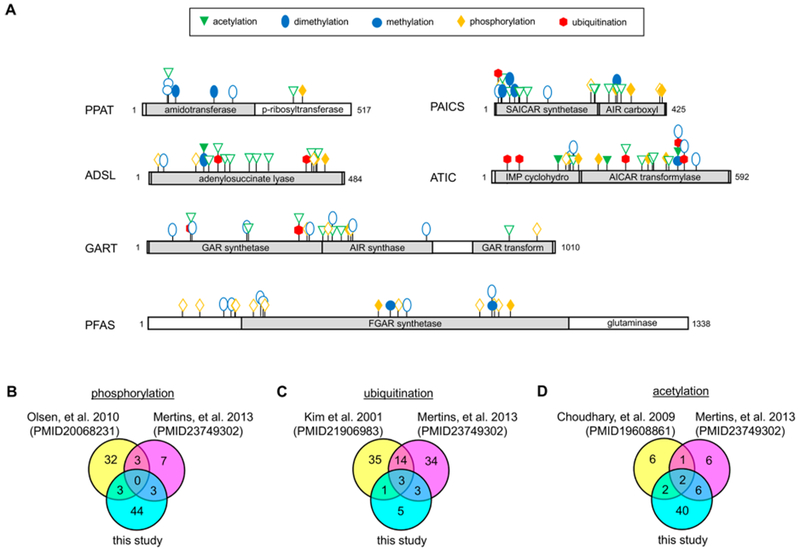

A total of seven different PTMs were identified across the six de novo purine biosynthetic enzymes: lysine monomethylation, arginine monomethylation, lysine dimethylation, lysine ubiquitination (inferred from diglycyl modification), lysine acetylation, serine/threonine phosphorylation, and tyrosine phosphorylation (Figure 1A and Table 1). All proteins analyzed were highly acetylated and dimethylated except for PFAS, which showed phosphorylation on 15 serine/threonine residues (Table 1). Serine/threonine phosphorylation was also predominant in both the IMP cyclohydrolase and AICAR transformylase domains of ATIC. Four of the enzymes in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway (GART, PAICS, ADSL, and ATIC) had diglycyl linkages to lysine residues suggestive of ubiquitination but not to the extent of results obtained from global analyses of the ubiquitin-modified proteome.32,33 Numerous ubiquitination sites previously identified by these studies on GART were shown here to also be sites of acetylation and/or dimethylation: 250IK(acetyl)DTVLQR257, 434SLTYK(dimethyl)ESGVDIAAGNMLVK452, 434SLTYK(acetyl)ESGVDIAAGNMLVK452, 481AAGFK(dimethyl)-DPLLASGTDGVGTK499. The observation of multiple species for a given site suggests a level of regulation that is not fully clear. Minimal arginine or lysine methylations and tyrosine phosphorylations were observed.

Figure 1.

Unambiguously assigned PTMs across the six de novo purine biosynthetic enzymes showing a preference for either purine supplemented or depleted growth conditions. (A) PTMs showing a preference for purine supplemented conditions are denoted by a solid filled symbol corresponding to the type of modification, whereas those observed under purine depleted conditions are represented as outlines of the designated symbol. Unambiguity was determined by a SLIP score of ≥6 for a given modification site. A comparison of our assigned PTMs from this data set to those data sets previously published from global (B) phosphorylation,33,34 (C) ubiquitination,32,33 and (D) acetylation33,35 proteomic studies.

Table 1.

Summary of Unambiguous Post-Translational Modifications Identified from Isolated de Novo Purine Biosynthetic Enzymes (Number of Novel Modifications Shown in Parentheses)

| de novo purine biosynthetic enzymes |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| modification | PPAT | GART | PFAS | PAICS | ADSL | ATIC |

| lysine acetylation | 5 (2) | 9 (7) | 0 | 13 (7) | 10 (8) | 13 (12) |

| lysine monomethylation | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| arginine monomethylation | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| lysine dimethylation | 4 (4) | 12 (12) | 6 (6) | 10 (10) | 9 (9) | 9 (9) |

| ubiquitination | 0 | 2 (0) | 0 | 1 (0) | 4(1) | 5 (0) |

| serine/threonine phosphorylation | 2 (2) | 6 (3) | 15 (6) | 8 (3) | 3 (0) | 14 (4) |

| tyrosine phosphorylation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

When compared to previously reported global phosphorylation,33,34 ubiquitination,32,33 and acetylation33,35 proteomic studies, only a handful (6-16%) of modifications were in agreement (Figure 1B-D and Tables S5-S7). To our best knowledge, 118 of the 174 unambiguous PTMs assigned were novel, effectively tripling the number of known PTMs for these proteins. Lysine acetylation, lysine dimethylation, and serine/ threonine phosphorylation accounted for 89% of the novel modifications identified. PTMs are often linked to intracellular signaling events, so the expansion of newly identified PTMs provides a renewed context in how cell signaling might regulate cellular metabolism by altering the state of enzymes in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway.

PTM State of de Novo Enzymes Change upon Pathway Activation

It is conceivable that differences in modifications could regulate changes in enzymatic state such as catalytic activity, oligomerization, substrate channeling, or degradation or a combination of such. We next asked whether the PTMs identified were specific to those cells grown under purine-depleted growth conditions. Purine-depletion in 293T cells was shown to result in a 1.5-fold increase in metabolic flux through the de novo pathway, which is consistent with the observed increase previously reported for HeLa cells (Figure S1B).22 Those PTMs differentially detected between purine depleted and supplemented growth conditions are shown in Figure 1A. All of the enzymes analyzed showed differences in the PTMs between the two experimental conditions with lysine methylation and serine/threonine phosphorylation modifications showing the greatest number of differences (Tables S3 and S4). Acetylation was most predominantly noted on peptides mapped to GART, PAICS, and ADSL originally isolated from purine-depleted 293T cells. Consistent with prior acetylome reports,33,35 Lys246 on PAICS was shown to be acetylated [233DLKEVTPEGLQMVK(acetyl)K247] only under growth conditions favoring pathway activation. Lysine acetylation plays an important roles in regulation of metabolic enzyme function, including the amount of available metabolic enzyme, their overall activity, and their substrate accessibility.36 Under the same experimental conditions, PFAS was heavily serine/threonine phosphorylated with 10 unique sites of modification emerging that were absent under purine supplemented conditions. The high abundance of phosphorylation sites on PFAS under pathway activating conditions suggest that there might be multiple kinases responsible for modulating its activity.

However, phosphorylation was not just preferential under purine-depleted growth conditions. ATIC was also shown to be highly phosphorylated under purine supplemented growth conditions. Prior studies have reported that ATIC enzymatic activity can be regulated by PTMs including phosphorylation.37 The observed Thr182 and Ser190 phosphorylation sites on ATIC are located at the dimer interface of the IMP cyclohydrolase domain and these phosphorylation events might lead to disruption of the functional dimer (Figure S3).38 A substrate of ATIC, AICAR, is known as a regulator of the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway through the allosteric activation of AMPK.18,39 Therefore, it is possible that the decreased metabolic purine flux through the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway might be in part to a phosphorylation-mediated inactivation of the ATIC dimer resulting in a buildup of intracellular AICAR.

In addition to phosphorylation, ATIC was also shown to be ubiquitinated on five lysine residues only under purine supplemented growth conditions. One of these residues, Lys66, is located in the 5-formyl-AICAR (FAICAR) binding site and is likely to disrupt substrate binding and/or impede cyclohydrolase activity (Figure S3).38 Ubiquitination was also observed on GART and ADSL only isolated from cells grown under purine supplemented conditions. Differences in GART ubiquitination were only noted in the GAR synthetase (GARS) domain at residues Lys107 and Lys378. Human GARS shares 50% sequence identity with its closest structural homolog from Escherichia coli, PurD (Figure S4A). Furthermore, available crystal structures of PurD and human GARS (Figure S4B) demonstrate that both have an classic ATP-grasp fold and superimpose nicely with a RMSD value of 1.7 angstroms.40 Structural analyses of PurD indicate that Lys105 is part of the flexible B-domain present in all ATP-grasp family members that becomes ordered upon ATP binding and aids to stabilize the α and β phosphates.41,42 We hypothesize that the homologous human residue, Lys107, might also regulate nucleotide binding and when monoubiquitinated, this process is disrupted. Given that monoubiquitination of Lys107 was only observed when the pathway is down-regulated, it is possible that this modification might interfere with the transformation of 5-phosphoribosylamine (PRA) into phosporibosylglycinamide thus also impeding flux through the de novo pathway.

Predicted Role of Kinases in Phosphorylation of de Novo Purine Biosynthetic Enzymes

Increasing evidence suggesting kinase involvement in the regulation of purine biosynthesis combined with our newly identified phosphorylation sites among pathway enzymes raised the question of whether any of the pathway enzymes serve as substrates for kinases involved in those regulatory pathways. To address this possibility, we queried the sequence of amino acids flanking each phosphorylation site against known kinase substrate motifs. Kinase predictions are shown in Table 2. Not all phosphorylation sites identified were able to be assigned to a specific kinase with confidence and instead were reported as a series of potential kinases or kinase family.

Table 2.

Kinase(s) Predicted to Be Involved in the Phosphorylation of Selected Residues

| experimental conditions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| enzyme | phospho site | supplemented | depleted | predicted kinase(s) |

| PPAT | Thr397 | + | − | AKT, RSK/MSK/S6K |

| GART | Ser491 | + | − | ERK5 |

| Ser973 | − | + | CK2, CDC7 | |

| PFAS | Ser128 | − | + | PAK, aurora kinases, PKA, PKG |

| Ser215 | − | + | AKT, RSK/MSK/S6K, PKD, CHEK1, CAMK4 | |

| Ser261 | − | + | PERK, activin-like receptors | |

| Thr290 | − | + | PERK, PKR, HRI | |

| Thr623 | − | + | MAP kinases | |

| Ser857 | − | + | CDK family | |

| Ser873 | − | + | ATM/ATR/DNA-PK | |

| PAICS | Thr18 | − | + | PKR, haspin |

| Thr238 | − | + | CMGC family kinases | |

| Thr409 | − | + | RIPK2 | |

| Ser412 | + | − | CK1, following Thr409 phosphorylation | |

| ADSL | Ser21 | − | + | CMGC family kinases |

| Ser407 | − | + | ATM/ATR/DNA-PK | |

| Ser434 | + | − | CDK5, CDK9 | |

| ATIC | Ser190 | + | − | CK2, CDC7 |

| Thr215 | + | − | CMGC family kinases | |

| Ser387 | + | − | ATM/ATR/DNA-PK | |

Several of the predicted kinases are within the CMGC class that largely represents mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases and cell cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) involved in metabolic control. MAP kinase signaling pathway enzymes were predicted to be involved in PFAS phosphorylation at residue Thr623 in the absence of purines, whereas cell cycle regulatory kinases CDK5 and CDK9 were predicted to be involved in the phosphorylation of ADSL on Ser434 in the presence of purines. All pathway enzymes except for PPAT were predicted to be phosphorylated by kinases associated with regulation of the cell cycle. Enhanced purine production through the de novo pathway has been shown to be associated with certain cell cycle phases.43 The emergence of checkpoint kinase 1 (CHEK1), CDKs, cell division cycle 7-related protein kinase (CDC7), and aurora kinases as predicted kinases increases the probability that activation of these enzymes might be driven by changes in cell cycle regulatory mechanisms.

Several mapped phosphorylation sites across the six enzymes were predicted to be substrates of kinases within the anticipated PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway (Table 2). Previously, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways have been implicated in intracellular purine production; however, the exact mechanism of biochemical regulation has not been well understood.15,16 Amino acid sequences flanking noted phosphorylation sites on PPAT (Thr397) and PFAS (Ser215) are predicted to be strong substrates of AKT in which an arginine residue is favored in the −3 position and a hydrophobic residue in the +1 position relative to the serine or threonine phosphoacceptor. One such example is Thr397 on PPAT [385IVLVDDSIVRGNT(phospho)ISPIIK403], where an isoleucine is in the +1 position relative to a threonine phosphoacceptor.

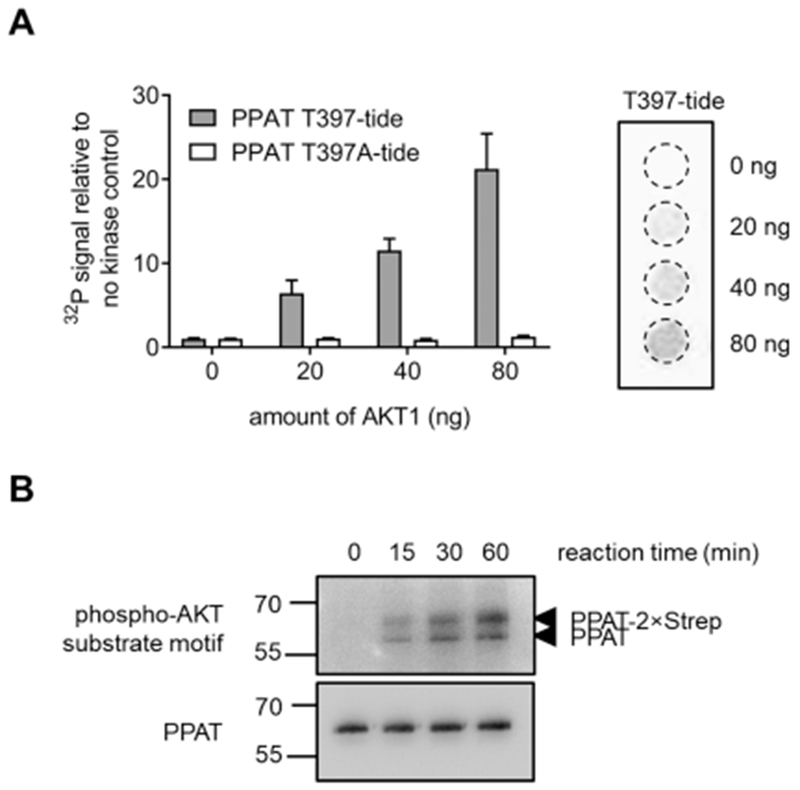

To identify whether the phosphorylation of Thr397 on PPAT is directed by AKT, an in vitro kinase assay was performed. The ability of a peptide-based substrate mimic of the phosphorylation site (392IVRGNTISPI401 referred to as T397-tide) to become phosphorylated at varying amounts of kinase was performed alongside a control, unphosphorylatable peptide (T397A-tide). The T397-tide showed a 21 ± 4-fold increase in AKT (80 ng) phosphorylation after 2 h relative to the no kinase control, whereas no change in the T397A-tide peptide was observed (Figure 2A). We further assessed whether the active form of PPAT was capable of being phosphorylated by AKT. Using non-phosphorylated PPAT isolated from purine-depleted 293T cells, AKT was shown to phosphorylate PPAT in a time-dependent manner (Figure 2B). Together, these results suggest that AKT is likely to phosphorylate PPAT at Thr397. This phosphorylation event was only observed under purine-supplemented growth conditions, in which purine biosynthesis is not the predominant pathway for purine generation. Previously, PPAT was suspected to be inactive under purine supplementation either from nucleotide-mediated feedback inhibition or through a decrease in substrate availability. Now, we provide evidence suggesting that this phosphorylation event might also provide a means for how PPAT is down-regulated when the de novo pathway is not warranted.

Figure 2.

Thr397 on PPAT is phosphorylated by AKT. Results of an in vitro kinase assay demonstrate the ability of AKT to phosphorylate (A) a peptide-based substrate mimic of PPAT (T397-tide, gray) while having no effect on a non-phosphorylatable control peptide (T397A-tide, white) and (B) purified PPAT from purine-depleted 293T cells.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The lack of evidence for significant protein expression changes upon activation of the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway suggests that post-translational modifications are likely a regulatory factor employed to control enzyme activities and IMP production through the pathway. Here, we outlined the discovery of 118 novel PTMs across the six enzymes within the pathway and validated another 56 previously reported modifications from various high-throughput global proteomic analyses. Differences in the PTMs unambiguously assigned among these six enzymes expressed in the presence or absence of purines were noted to provide insights into mechanisms of enzymatic and pathway control. Most intriguing are those sites that are shown to have competing PTMs depending on the experimental conditions the isolated target enzyme originated. Examples include Lys378 on GART and Lys170 on ADSL, where these residues were shown to be ubiquitinated in the presence of purines and replaced by acetyl groups in their absence.

Furthermore, we explored the intracellular signaling cascades that might lead to the phosphorylation events observed. Using substrate motif preferences from known kinases, observed phosphorylation sites can be linked to the PI3K/AKT and mTOR/ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) signaling pathways.44 mTOR has been shown to influence intracellular purine production. One mechanism involves the downstream transcriptional regulation of MTHFD2, which encodes the enzyme responsible for generating the formate that is readily converted into the 10-formyltetrahydrofolate cofactor needed for purine biosynthesis.17 We now have evidence that highly suggests that enzymes within these signaling pathways, such as AKT and S6K, might influence IMP production directly through the phosphorylation of purine biosynthetic enzymes.

An ever-growing hypothesis is that, upon pathway activation, sequential metabolic enzymes within their respective pathways organize into multi-enzyme complexes referred to as metabolons.45 The enzymes in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway form a dynamic metabolon, called the purinosome, in response to changes in intracellular purine levels.2 Growth conditions favoring purinosome formation have been correlated to cell cycle phase, where purine demand and purinosome formation is highest in the G1 phase.46 Based on our kinase predictions (Table 2), several residues might be phosphorylated by kinases whose expression and activity is cell cycle phase-dependent. One example is the phosphorylation of Ser857 on PFAS, observed only in pathway activating conditions, by any member within the CDK family. The activities of CDK2/4/6 are elevated in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, so it is quite possible that any one of these kinases might activate enzymatic activity and promote complexation.47 Equally important is the kinase CDC7. This kinase was proposed to likely phosphorylate Ser973 on GART, Ser190 on ATIC, or a combination of both. The kinase activity of CDC7 is dependent on its association with regulatory subunit Dbf4 in late G1, so it is plausible that the phosphorylation of GART or ATIC might modulate purinosome formation at this transition.48 Further investigations are warranted to know exactly if a specific kinase or phosphorylation event is responsible for purinosome formation.

Previously, enzymes within glycolysis were also shown to form such as complex, whereas complex formation is regulated, at least in part, by the acetylation of human liver-type phosphofructokinase 1.49 Lysine acetylation has been widely reported to preferentially target macromolecular complexes involved in cell cycle regulation, actin cytoskeleton remodeling, and DNA damage and repair.35 In our study, acetylation accounts for 29% of modifications mapped unambiguously on enzymes within the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway including proposed rate-limiting enzymes PPAT (5 mapped sites) and ATIC (13 mapped sites). It is not certain if these acetylation events identified result in modulation of purinosome assembly, similar to that observed in glycolysis.

The identification of these PTMs is the first step in understanding the complexity of biochemical mechanisms that promote efficient purine production in cells. These modifications likely reflect a combination of regulatory events that simultaneously contribute to the overall enzymatic state, such as catalytic activity and oligomerization, and thereby impact pathway status. Additionally, it is likely that any number of these modifications observed only under purine-depleted conditions might be instrumental to the formation of the purinosome. The complexity of the PTM response in terms of types and cell status for just one metabolic pathway underscores how intertwined various regulatory elements are and the daunting task of evaluating the contribution of an individual PTM. Further studies on the characterization of these PTMs are warranted to gain a better appreciation of the function of specific modifications and their influence on enzyme organization and metabolic flux.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank members of the Benkovic Laboratory for critical analysis of the manuscript, the University of California San Francisco Mass Spectrometry Facility directed by A.L. Burlingame (A.L.B.), and the Pennsylvanie State Metabolomics Core Facility at University Park, PA directed by P. Smith for processing and technical assistance in the analysis of metabolite measurements. Financial support for this study was provided by The National Institutes of Health (R01GM024129 to S.J.B., P41GM103481 to A.L.B., and R35CA197588 to L.C.C.) and the Adelson Family Foundation (A.L.B.).

Footnotes

Boragen, Inc., Durham, North Carolina 27709, United States

Alaunus Biosciences, Inc., San Francisco, California 94107, United States

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteo-me.8b00969.

Figures showing pathway activation analysis, expression and purification profiles, an ATIC structural model, and GART structural model. Tables showing protein construct sequences, phosphorylation site comparison, an ubiquitination site comparison, and an acetylation site comparison (PDF)

A table showing peptide sequence data from mass spectrometry (XLSX)

A table showing iIdentified post-translational modifications (XLSX)

A table showing a modification comparison in the presence and absence of purines (XLSX)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): L.C.C. is a founder and member of the BOD of Agios Pharmaceuticals; he is also a co-founder, member of the SAB, and shareholder of Petra Pharmaceuticals. These companies are developing novel therapies for cancer. The L.C.C. laboratory receives some funding support from Petra Pharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES

- (1).Mayer D; Natsumeda Y; Ikegami T; Faderan M; Lui M; Emrani J; Reardon M; Olah E; Weber G Expression of key enzymes of purine and pyrimidine metabolism in a hepatocyte-derived cell line at different phases of the growth cycle. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1990, 116 (3), 251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Natsumeda Y; Prajda N; Donohue JP; Glover JL; Weber G Enzymic capacities of purine de Novo and salvage pathways for nucleotide synthesis in normal and neoplastic tissues. Cancer Res. 1984, 44 (6), 2475–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Holmes EW; McDonald JA; McCord JM; Wyngaarden JB; Kelley WN Human glutamine phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase. Kinetic and regulatory properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1973, 248 (1), 144–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Smith JL Glutamine PRPP amidotransferase: snapshots of an enzyme in action. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1998, 8 (6), 686–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Yamaoka T; Yano M; Kondo M; Sasaki H; Hino S; Katashima R; Moritani M; Itakura M Feedback inhibition of amidophosphoribosyltransferase regulates the rate of cell growth via purine nucleotide, DNA, and protein syntheses. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276 (24), 21285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Zhou G; Smith JL; Zalkin H Binding of purine nucleotides to two regulatory sites results in synergistic feedback inhibition of glutamine 5-phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269 (9), 6784–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Itakura M; Holmes EW Human amidophosphoribosyl-transferase. An oxygen-sensitive iron-sulfur protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1979, 254 (2), 333–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zhou GC; Dixon JE; Zalkin H Cloning and expression of avian glutamine phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase. Conservation of a bacterial propeptide sequence supports a role for posttranslational processing. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265 (34), 21152–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Pedley AM; Karras GI; Zhang X; Lindquist S; Benkovic SJ Role of HSP90 in the Regulation of de Novo Purine Biosynthesis. Biochemistry 2018, 57 (23), 3217–3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Greasley SE; Horton P; Ramcharan J; Beardsley GP; Benkovic SJ; Wilson IA Crystal structure of a bifunctional transformylase and cyclohydrolase enzyme in purine biosynthesis. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001, 8 (5), 402–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Vergis JM; Bulock KG; Fleming KG; Beardsley GP Human 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide transformy-lase/inosine 5’-monophosphate cyclohydrolase. A bifunctional protein requiring dimerization for transformylase activity but not for cyclohydrolase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276 (11), 7727–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gassmann MG; Stanzel A; Werner S Growth factor-regulated expression of enzymes involved in nucleotide biosynthesis: a novel mechanism of growth factor action. Oncogene 1999, 18 (48), 6667–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Boss GR Decreased phosphoribosylpyrophosphate as the basis for decreased purine synthesis during amino acid starvation of human lymphoblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259 (5), 2936–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Nosal JM; Switzer RL; Becker MA Overexpression, purification, and characterization of recombinant human 5-phosphor-ibosyl-1-pyrophosphate synthetase isozymes I and II. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268 (14), 10168–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Saha A; Connelly S; Jiang J; Zhuang S; Amador DT; Phan T; Pilz RB; Boss GR Akt phosphorylation and regulation of transketolase is a nodal point for amino acid control of purine synthesis. Mol. Cell 2014, 55 (2), 264–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wang W; Fridman A; Blackledge W; Connelly S; Wilson IA; Pilz RB; Boss GR The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/akt cassette regulates purine nucleotide synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284 (6), 3521–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ben-Sahra I; Hoxhaj G; Ricoult SJH; Asara JM; Manning BD mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science 2016, 351 (6274), 728–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Corton JM; Gillespie JG; Hawley SA; Hardie DG 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside. A specific method for activating AMP-activated protein kinase in intact cells? Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 229 (2), 558–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Gwinn DM; Shackelford DB; Egan DF; Mihaylova MM; Mery A; Vasquez DS; Turk BE; Shaw RJ AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 2008, 30 (2), 214–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Inoki K; Zhu T; Guan KL TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell 2003, 115 (5), 577–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).An S; Kyoung M; Allen JJ; Shokat KM; Benkovic SJ Dynamic regulation of a metabolic multi-enzyme complex by protein kinase CK2. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285 (15), 11093–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Zhao H; Chiaro CR; Zhang L; Smith PB; Chan CY; Pedley AM; Pugh RJ; French JB; Patterson AD; Benkovic SJ Quantitative analysis of purine nucleotides indicates that purinosomes increase de novo purine biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290 (11), 6705–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).French JB; Jones SA; Deng H; Pedley AM; Kim D; Chan CY; Hu H; Pugh RJ; Zhao H; Zhang Y; Huang TJ; Fang Y; Zhuang X; Benkovic SJ Spatial colocalization and functional link of purinosomes with mitochondria. Science 2016, 351 (6274), 733–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).An S; Kumar R; Sheets ED; Benkovic SJ Reversible compartmentalization of de novo purine biosynthetic complexes in living cells. Science 2008, 320 (5872), 103–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Chalkley RJ; Baker PR; Medzihradszky KF; Lynn AJ; Burlingame AL In-depth analysis of tandem mass spectrometry data from disparate instrument types. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2008, 7 (12), 2386–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Elias JE; Gygi SP Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 2007, 4 (3), 207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Baker PR; Trinidad JC; Chalkley RJ Modification site localization scoring integrated into a search engine. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2011, 10 (7), M111008078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lu W; Clasquin MF; Melamud E; Amador-Noguez D; Caudy AA; Rabinowitz JD Metabolomic analysis via reversed-phase ion-pairing liquid chromatography coupled to a stand alone orbitrap mass spectrometer. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82 (8), 3212–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Schmidt T; Skerra A The Strep-tag system for one-step affinity purification of proteins from mammalian cell culture. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1286, 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Schmidt TG; Skerra A The Strep-tag system for one-step purification and high-affinity detection or capturing of proteins. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2 (6), 1528–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Morris JH; Knudsen GM; Verschueren E; Johnson JR; Cimermancic P; Greninger AL; Pico AR Affinity purification-mass spectrometry and network analysis to understand protein-protein interactions. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9 (11), 2539–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kim W; Bennett EJ; Huttlin EL; Guo A; Li J; Possemato A; Sowa ME; Rad R; Rush J; Comb MJ; Harper JW; Gygi SP Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol. Cell 2011, 44 (2), 325–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Mertins P; Qiao JW; Patel J; Udeshi ND; Clauser KR; Mani DR; Burgess MW; Gillette MA; Jaffe JD; Carr SA Integrated proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications by serial enrichment. Nat. Methods 2013, 10 (7), 634–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Olsen JV; Vermeulen M; Santamaria A; Kumar C; Miller ML; Jensen LJ; Gnad F; Cox J; Jensen TS; Nigg EA; Brunak S; Mann M Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals widespread full phosphorylation site occupancy during mitosis. Sci. Signaling 2010, 3 (104), ra3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Choudhary C; Kumar C; Gnad F; Nielsen ML; Rehman M; Walther TC; Olsen JV; Mann M Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science 2009. 325 (5942), 834–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Xiong Y; Guan KL Mechanistic insights into the regulation of metabolic enzymes by acetylation. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 198 (2), 155–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Boccalatte FE; Voena C; Riganti C; Bosia A; D’Amico L; Riera L; Cheng M; Ruggeri B; Jensen ON; Goss VL; Lee K; Nardone J; Rush J; Polakiewicz RD; Comb MJ; Chiarle R; Inghirami G The enzymatic activity of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase/IMP cyclohydrolase is enhanced by NPM-ALK: new insights in ALK-mediated pathogenesis and the treatment of ALCL. Blood 2009, 113 (12), 2776–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Wolan DW; Cheong CG; Greasley SE; Wilson IA Structural insights into the human and avian IMP cyclohydrolase mechanism via crystal structures with the bound XMP inhibitor. Biochemistry 2004, 43 (5), 1171–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Sullivan JE; Brocklehurst KJ; Marley AE; Carey F; Carling D; Beri RK Inhibition of lipolysis and lipogenesis in isolated rat adipocytes with AICAR, a cell-permeable activator of AMP-activated protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 1994, 353 (1), 33–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Welin M; Grossmann JG; Flodin S; Nyman T; Stenmark P; Tresaugues L; Kotenyova T; Johansson I; Nordlund P; Lehtio L Structural studies of tri-functional human GART. Nucleic Acids Res 2010. 38 (20), 7308–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Fawaz MV; Topper ME; Firestine SM The ATP-grasp enzymes. Bioorg. Chem. 2011, 39 (5-6), 185–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Wang W; Kappock TJ; Stubbe J; Ealick SE X-ray crystal structure of glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 1998, 37 (45), 15647–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Fridman A; Saha A; Chan A; Casteel DE; Pilz RB; Boss GR Cell cycle regulation of purine synthesis by phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate and inorganic phosphate. Biochem. J. 2013, 454 (1), 91–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Saxton RA; Sabatini DM mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 169 (2), 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Srere PA The metabolon. Trends Biochem. Sci 1985, 10 (3), 109–110. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Chan CY; Zhao H; Pugh RJ; Pedley AM; French J; Jones SA; Zhuang X; Jinnah H; Huang TJ; Benkovic SJ Purinosome formation as a function of the cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112 (5), 1368–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Morgan DO Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997, 13, 261–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Jackson AL; Pahl PM; Harrison K; Rosamond J; Sclafani RA Cell cycle regulation of the yeast Cdc7 protein kinase by association with the Dbf4 protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993, 13 (5), 2899–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Kohnhorst CL; Kyoung M; Jeon M; Schmitt DL; Kennedy EL; Ramirez J; Bracey SM; Luu BT; Russell SJ; An S Identification of a multienzyme complex for glucose metabolism in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292 (22), 9191–9203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.